Rapid risk assessment: Oropouche virus (OROV), public health implications for Canada

Assessment completed: September 20, 2024 (based on information available as of August 30, 2024)

On this page

- Reason for assessment

- Risk question(s)

- Risk statement

- Risk assessment summary

- Proposed actions for public health authorities

- Technical annex

- Appendix A: Rapid risk assessment methods

- Appendix B: Acknowledgements

- Footnotes

- References

Reason for assessment

There are concerns regarding changing epidemiological and clinical characteristics of Oropouche virus (OROV) disease. The recent identification of outbreaks in areas that have not previously reported OROV cases, including Cuba, Bolivia and non-Amazon regions of Brazil, indicates the potential for geographic expansion of OROV transmission to other areas with suitable vectors. In addition, the Brazilian Ministry of Health recently reported the first 2 recorded deaths from OROV disease, and several cases of fetal death and congenital anomalies either confirmed or suspected to be linked to vertical transmission of OROV during pregnancy. Prior to 2024, no deaths from OROV had been reported, and only 2 instances of spontaneous abortion potentially associated with vertical OROV transmission had been documented.

Risk question(s)

- What is the likelihood and impact of OROV infection in CanadiansFootnote a travelling to or residing in affected countriesFootnote b in the next 7 months?Footnote c

- What is the likelihood and impact of a domestically-acquired OROV infection in a person in Canada in the next 7 months?Footnote c

A timeframe of 7 months (up to the end of March 2025) was chosen for this assessment as this covers a period of high travel volume for the Canadian population to potentially affected countries.

Risk statement

The overall risk from OROV for the general population of Canada is currently low. Persons travelling to or residing in countries with ongoing OROV transmission, particularly pregnant individuals, are at higher risk and should take appropriate precautions.

The likelihood of OROV infection in Canadians travelling to or residing in affected countries in the next 7 months is assessed as low to moderate, varying by location, timing and duration of travel, as well as use of protective measures. Likelihood of infection will be elevated if travel to OROV-affected countries occurs during the rainy season and is of longer duration, and if measures to prevent insect bites are not taken.

The health impacts of OROV infection for non-pregnant individuals is estimated as minor: serious illness is uncommon and infected individuals typically make a full recovery with no long-term sequelae. Uncertainty in this estimate is moderate due to the limited evidence on the frequency of severe outcomes of OROV infection from longitudinal studies and the lack of data on health impacts specifically among travellers. The health impacts of OROV infection for pregnant individuals, fetuses and newborns is estimated as major, given emerging evidence that OROV can cause serious and irreversible adverse pregnancy outcomes, including fetal death and congenital anomalies. Uncertainty in this estimate is high due to the very limited information on the frequency and impacts of severe outcomes of OROV infection in pregnancy.

Imported cases of OROV disease among travellers coming or returning to Canada from affected countries are expected to occur over the next 7 months. However, the likelihood of a domestically-acquired OROV infection in a person in Canada in the next 7 months is assessed as very low. This reflects several factors including: the absence (to current knowledge) of mosquitoes or midges known to be efficient OROV vectors in Canada, the short duration of viremia in humans, and the reduced activity of biting insects during the fall and negligible activity during the winter months in Canada. If domestically-acquired infection were to occur, the population impact would be minor, due to the limited number of cases involved.

Risk assessment summary

| Risk questions | Risk sub-questions | Estimate | Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Question A: What is the likelihood and impact of OROV infection in Canadians travelling to or residing in affected countries in the next 7 months? | A1. What is the likelihood of a Canadian residing in an affected country becoming infected in the next 7 months? | Low to moderate | Moderate |

| A2. What is the likelihood of a Canadian traveller to an affected country becoming infected in the next 7 months? | |||

| A3. What is the magnitude of health impacts from OROV infection among non-pregnant individuals? | Minor | Moderate | |

| A4. What is the magnitude of health impacts from OROV infection among pregnant individuals, their fetuses, and newborns? | Major | High | |

| Question B: What is the likelihood and impact of a domestically-acquired OROV infection in a person in Canada in the next 7 months? | B1. What is the likelihood of at least one infected traveller entering Canada in the next 7 months? | High | Low |

| B2. If an infected person enters Canada, what is the likelihood of a domestically-acquired infection occurring? | Very low | Moderate | |

| B3. If domestically-acquired infection occurs, what would be the magnitude of population-level health impacts? | Minor | Low | |

Notes: |

|||

Future risk for Canada

The risk for Canada posed by OROV is dependent on the extent of geographic expansion in transmission from the currently affected countries. Recent expansion of OROV activity to new regions that have not previously reported cases indicates strong potential for this virus to become established in new areas where suitable vector populations occur. However, the speed and extent of spread into new geographic areas is difficult to predict.

The most plausible scenario beyond March 2025 is for small numbers of OROV disease cases to occur among Canadian travellers, primarily associated with travel to Cuba, a major travel destination for Canadians. If there is expansion and establishment of OROV into new regions that have strong travel links with Canada, such as other countries in the Caribbean, Central America, and potentially parts of the United States, this could signal a further shift in risk for the Canadian population. It should be noted, however, that the Americas region is experiencing a more general increase in transmission of arboviral infections, most notably dengue, chikungunya and Zika, which continue to pose risk for travellers. As OROV is an emerging risk for Canadian travellers, there may be low awareness among Canadian healthcare providers to consider OROV in their differential diagnosis of ill travellers returning from affected regions, including pregnant individuals.

Although very unlikely, the worst-case scenario in the next 12 months would occur if environmental and ecological conditions were found to support transmission within Canada, resulting in limited numbers of domestically-acquired OROV cases following travel-related importation in the summer months. OROV transmission within Canada could potentially occur through insect vectors imported from other countries or through certain insect species present in Canada, although there is currently limited knowledge regarding whether midge and mosquito species in Canada can efficiently transmit OROV. If domestically-acquired infection occurred, it would likely be restricted to certain geographic regions in the southernmost parts of Canada, where temperature conditions for development of the virus in any suitable vectors may be present.

Proposed actions for public health authorities

Recommendations provided below are based on findings of this risk assessment. These are for consideration by jurisdictions according to their local epidemiology, policies, resources, and priorities. Due to the current level of uncertainty associated with OROV, it is important that the public health response be proportionate to the risk.

Surveillance coordination and collaboration

- Encourage information sharing on confirmed cases with public health partners (provincial/territorial, national and global) to contribute to risk assessment and global epidemiological knowledge of this emerging threat.

Communication

- Consider updating information for travellers to affected regions, including pregnant individuals and those trying to be pregnant, based on evolving evidence. Refer to PHAC's travel health notice "Oropouche fever in the Americas" for information on the current situation and recommendations for travellers.

- Consider engaging the travel industry and travel health clinics in advance of the winter travel season to raise awareness of OROV among their clients and patients, including sharing information from PHAC's travel health notices and on prevention of mosquito/midge bites.

- Consider activities to enhance awareness and education of health professionals (e.g., primary care, obstetrics, prenatal clinics) on the diagnosis of OROV infection in those returning from affected regions.

Addressing knowledge gaps and uncertainties

- Consider supporting research activities to address knowledge gaps.

Technical annex

Event background

In 2024, increases in Oropouche virus (OROV) disease have been reported in several countries in the Americas region, including Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Bolivia and Cuba. The virus has also been detected in the Dominican Republic. Historically, reports of OROV outbreaks have been limited to a few regions in Central and South America and the Caribbean, including Trinidad and Tobago, where the virus was first documented in 1955, Panama and parts of the Amazon Basin, where OROV is believed to be endemic.Footnote 1 Footnote 2 The present identification of outbreaks in areas that have not previously reported OROV cases, including non-Amazon regions of Brazil, Bolivia and Cuba, indicates the potential for geographic expansion of OROV transmission to other areas with suitable vectors.Footnote 3

OROV is a single-stranded RNA vector-borne orthobunyavirus with a segmented genome.Footnote 4 It is believed that the virus can be maintained in a sylvatic cycle with wild animals acting as reservoirs. In humans, outbreaks are prototypically associated with an urban cycle, in which humans act as the main host and Culicoides paraensis midges are the principal vector; in some settings, Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes are also thought to play a role in transmission.Footnote 4 Following an incubation period of 3 to 8 days, approximately 60% of infected individuals develop symptoms,Footnote 1 commonly including fever, headache, myalgia and arthralgia. Clinical presentation overlaps with that of other arthropod-associated diseases, including dengue, chikungunya, Zika virus disease and malaria. Severe outcomes are uncommon but can include aseptic meningitis, meningoencephalitis and hemorrhagic symptoms.Footnote 5 Footnote 6 No specific antiviral treatments or vaccines are available for OROV disease, but cases typically make a full recovery.Footnote 5

On July 23, 2024, the Brazilian Ministry of Health reported the first two recorded fatalities from OROV infection. Neither case had known comorbidities, and both presented with high OROV viral loads and showed rapid progression from onset of symptoms to death, with severe coagulopathy and death occurring within 5 days of symptom onset.Footnote 3

Direct, horizontal, human to-human transmission of the virus has not been documented to date. However, based on information available as of August 30, 2024, the Brazilian Ministry of Health has reported 2 cases of adverse pregnancy outcomes (1 fetal death, 1 case of congenital anomalies) associated with vertical transmission of OROV. Twelve cases of vertical transmission involving fetal deaths and congenital anomalies remain under investigation.Footnote 7

As of August 30, 2024, 55 imported cases have been reported in EuropeFootnote 8 Footnote 9 and North America,Footnote 10 Footnote 11 including Canada, almost all associated with recent travel to Cuba. Cuba is a popular travel destination for Canadians, but awareness of OROV among travellers and health professionals is likely to be low. The main recognized vectors for OROV are not known to be present in Canada.Footnote 12 Footnote 13

Definitions

For the purposes of this assessment the following definitions are used:

- An affected country is one with ongoing OROV transmission. As of August 30, 2024, this includes Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Cuba and Peru.

- A Canadian traveller refers to any person normally residing in Canada who travels abroad.

- A Canadian residing abroad refers to a Canadian citizen or permanent resident who lives in a country other than Canada.

- A competent vector refers to an insect species that has the intrinsic capacity to transmit a pathogen. It should be noted that a competent vector may not necessarily be a suitable vector for transmission under natural conditions.

- Severe outcomes of OROV infection include death; hospitalization; central nervous system involvement (e.g., aseptic meningitis, meningoencephalitis); hemorrhagic symptoms; shock syndrome; and adverse pregnancy outcomes such as stillbirth, spontaneous abortion or congenital malformations. In pregnant individuals and their fetuses or newborns, any instance of vertical transmission is considered a severe outcome, regardless of clinical presentation in the pregnant individual, fetus or newborn. In this assessment, severe outcomes in individuals infected within the next 7 months are considered, regardless of when they occur relative to infection, which may be several months later in the case of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

- Non-pregnant individuals refers to all individuals who are not pregnant, irrespective of age.

- Domestically-acquired infection refers to an infection that results from a transmission event occurring within Canadian borders. For the purposes of this assessment, infection of a fetus during pregnancy is not considered domestically-acquired if infection in the pregnant individual occurred outside Canada.

Key assumptions

- Context assumptions

- Canadian travellers and Canadians residing in OROV-affected countries are assumed to have no immunity to OROV.

- Mitigating/control measures and standard practices assumed to be in place

- There is limited information on the extent and effectiveness of vector control activities in OROV-affected countries. Therefore, the potential impact of such activities is not explicitly considered in this assessment, nor does the assessment consider the potential for pest control activities to impact the likelihood of transmission within Canada.

- While use of insect bite precautions is likely to afford protection against infection, use of these measures by potentially impacted parties (travellers and Canadians living in affected countries, Canadians living in Canada) is not explicitly considered in this assessment.

- Pathway assumptions

- In large OROV outbreaks associated with the urban transmission cycle, humans are thought to be the only vertebrate host; in assessing the potential for domestically-acquired infection within Canada, the potential role of other animal hosts is not considered.

- Potential mechanisms for vector importation to Canada, such as through population movement or imported livestock, are not considered in this assessment.

- Currently, there is no documented evidence of horizontal human-to-human transmission of OROV other than through an insect vector. Vertical transmission during pregnancy has been documented. The role of other transmission modes is assumed to be negligible.

- Assumptions to address uncertainty

- Four OROV genotypes are recognized. There is currently no evidence for differences in virus behaviour (e.g. transmissibility, infectivity, illness severity) between genotypes. Therefore, for this assessment, specific influences of OROV genotype on estimates are not considered.

Detailed risk assessment results

Risk pathway

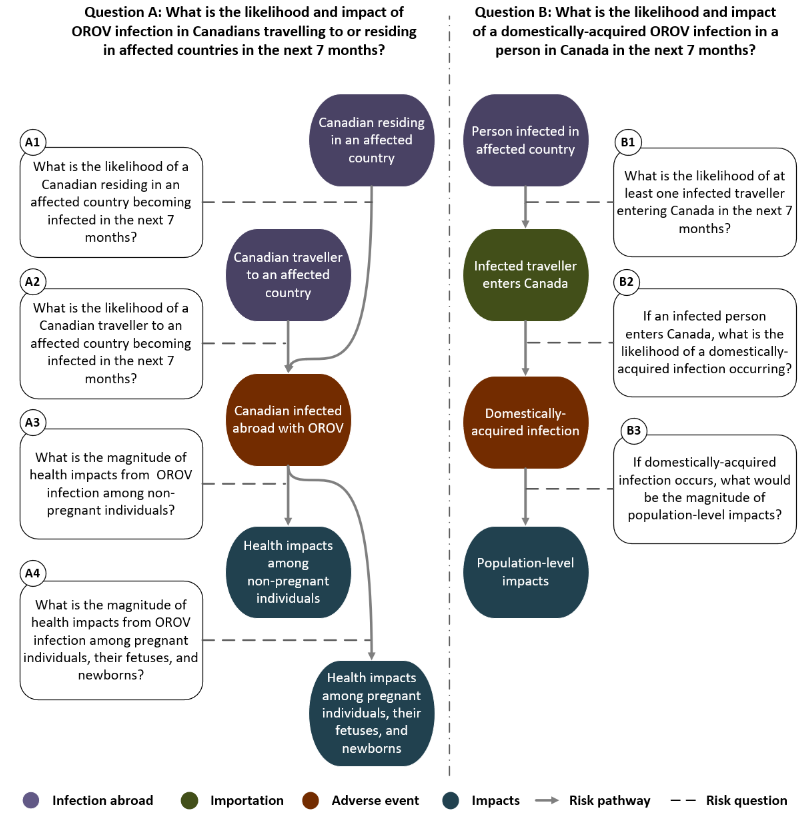

Figure 1: Text description

Description of pathway sources and infections abroad, the adverse events along the pathway, and the impacts on individual and population health. Events are in the order assessed by the rapid risk assessment. Each event is conditional on the preceding event indicated by a pathway connector.

Pathway for risk question A: What is the likelihood and impact of OROV infection in Canadians travelling to or residing in affected countries in the next 7 months?

- Pathway connector from Canadian residing in an affected country (infection abroad) to Canadian infected abroad with OROV (adverse event)

- Risk sub-question A1: What is the likelihood of a Canadian residing in an affected country becoming infected in the next 7 months?

- Pathway connector from Canadian traveller to an affected country (infection abroad) to Canadian infected abroad with OROV (adverse event)

- Risk sub-question A2: What is the likelihood of a Canadian traveller to an affected country becoming infected in the next 7 months?

- Pathway connector from Canadian infected abroad with OROV (adverse event) to health impacts among non-pregnant individuals (impacts)

- Risk sub-question A3: What is the magnitude of health impacts from OROV infection among non-pregnant individuals?

- Pathway connector from Canadian infected abroad with OROV (adverse event) to health impacts among pregnant individuals, their fetuses, and newborns (impacts)

- Risk sub-question A4: What is the magnitude of health impacts from OROV infection among pregnant individuals, their fetuses, and newborns?

Pathway for risk question B: What is the likelihood and impact of a domestically-acquired OROV infection in a person in Canada in the next 7 months?

- Pathway connector from person infected in affected country (infection abroad) to infected traveller enters Canada (importation)

- Risk sub-question B1: What is the likelihood of at least one infected traveller entering Canada in the next 7 months?

- Pathway connector from infected traveller enters Canada (importation) to domestically-acquired infection (adverse event)

- Risk sub-question B2: If an infected person enters Canada, what is the likelihood of a domestically-acquired infection occurring?

- Pathway connector from domestically-acquired infected (adverse event) to population-level impacts (impacts)

- Risk sub-question B3: If domestically-acquired infection occurs, what would be the magnitude of population-level impacts?

Likelihood and impact estimates

The following overall risk questions and specific risk sub-questions are derived from the risk pathway above:

Question A: What is the likelihood and impact of OROV infection in CanadiansFootnote a travelling to or residing in affected countriesFootnote b in the next 7 months?Footnote c

Question B: What is the likelihood and impact of a domestically-acquired OROV infection in a person in Canada in the next 7 months?Footnote c

Each of these questions has a number of component sub-questions that are assessed in detail below.

Question A: What is the likelihood and impact of OROV infection in Canadians travelling to or residing in affected countries in the next 7 months?

A1: What is the likelihood of a Canadian residing in an affected country becoming infected in the next 7 months?

Low to moderate (moderate uncertainty)

The likelihood of infection for those residing in OROV-affected countries will vary based on location and time of year; likelihood of infection is expected to be higher during the rainy season when vector activity is at its peak.

In Brazil, OROV disease incidence has been declining in recent weeks, as the period of high arbovirus activity (typically January to July) has ended. The current likelihood of infection is considered to be low, particularly for those not residing in the northern Amazon regions, which have accounted for 72% (n = 5586) of the reported cases in the country. The cumulative incidence of reported OROV disease in the northern region up to August 19th was 32 cases per 100,000 population, with the highest incidence reported in the states of Amazonas and Rondônia (82 and 108 cases per 100,000 respectively).Footnote 7 Infection likelihood is expected to be highest between January and March; two-thirds of reported cases occurred during this period.Footnote 7 Several non-Amazonian states in Brazil have reported OROV activity in 2024. The likelihood of infection in these states appears to be much lower: the majority have incidences of reported OROV disease of <2.5 per 100,000, with the exception of Bahia in the northeast and Espírito Santo in the southeast (6 and 12 cases per 100,000 respectively).Footnote 7 The epidemiological situation could be similar in rainforest areas of Bolivia, Colombia and Peru neighbouring the Amazon regions of Brazil. All three countries have reported declining numbers of confirmed cases in recent months, with the majority of cases occurring between January and March in Colombia and Bolivia, and between March and April in Bolivia.Footnote 14 Evidence from systematically-collected serological data to inform population exposure to OROV is scarce; historically, serological surveys in endemic regions of Brazil have reported seroprevalences of 2-6%.Footnote 15 Footnote 16 Footnote 17 However, transmission intensity for arboviruses is highly dependent on local conditions; in explosive OROV outbreaks, infection attack rates of 20%-40% have been documented in some parts of a community, with minimal transmission in others.Footnote 18 Footnote 19

Cuba reported 74 cases as of the end of May, 2024;Footnote 20 by early August, 2024, Cuban officials reported the presence of OROV in all provinces, with >400 confirmed cases.Footnote 21 Reports of imported OROV cases in other countries associated with travel to Cuba between June and August also indicate ongoing transmission within the country, with the likelihood of infection expected to be highest during the rainy season between May and November.

The size of the Canadian population exposed to OROV in affected countries is expected to be modest. Although exact figures are not available, estimates of 2020 international migrant stock from the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs indicate that approximately 11,000 Canadians live in Brazil (~2000), Cuba (<30), Peru (~5700), Bolivia (~1500) and Colombia (~1700) combined.Footnote 22

There is moderate uncertainty in this estimate due to lack of information regarding the geographic location of expatriate Canadians relative to areas with higher likelihood of OROV exposure, as well as uncertainty regarding the extent of current transmission within Cuba and the potential for OROV to spread to additional regions or countries in which Canadians reside during the period of assessment.

A2: What is the likelihood of a Canadian traveller to an affected country becoming infected in the next 7 months?

Low to moderate (moderate uncertainty)

The likelihood of infection for the majority of Canadian travellers to OROV-affected countries is assessed as low, particularly if travel is outside the rainy season. However, this likelihood may be elevated for certain travellers depending on location and duration of travel, season of travel, extent to which protective measures are used, and other factors influencing exposure to insect vectors.

For travel to Cuba, the likelihood of infection is expected to be highest during the rainy season between May and November. Notably, visits to Cuba tend to be of relatively short duration, averaging 7 days.Footnote 23 Footnote 24 Although information on case numbers in Cuba is currently limited, analysis based on imported cases associated with travel to Cuba reported in other countries as of August 30, 2024, suggests that for travellers, the current incidence of OROV disease could be between 0.5 and 3 cases per 10,000 returning travellers (Table 2). This is likely to be an under-estimate because mild cases may resolve prior to returning from Cuba or may not seek medical attention, and awareness of and testing for OROV is currently limited. There were >1 million travellers from Canada to Cuba between August 2023 and July 2024 (CBSA, unpublished data, 2023; CBSA, unpublished data 2024). The vast majority of these travellers (93%) were Canadian citizens and 65% of trips occurred between December 2023 and April 2024, when vector activity and infection likelihood in Cuba are expected to be lower. Although travel volume during the rainy season months of May to November is considerably lower, it is important to note that between 40,000 and 75,000 people per month travel to Cuba during this period, so small numbers of cases could still occur.

In Brazil, OROV incidence has been declining in recent weeks,Footnote 25 coinciding with the end of the rainy season. As of August 30, only 1 imported case associated with travel to Brazil has been reported (in Italy).Footnote 8 Transmission is expected to be highest between January and March, particularly in the northern Amazon regions. Of note, 90% of travel between Canada and Brazil is to areas that have so far reported low rates of OROV disease (<2 cases per 100,000 population) (IATA, unpublished data, 2023; IATA, unpublished data 2024).

There is moderate uncertainty regarding how OROV transmission levels will change over the coming months, particularly in Cuba, where there is currently limited information on the factors driving transmission, and following the start of the next rainy season in Brazil. However, the recent identification of OROV in new geographic regions, both within Brazil and other South American countries, suggests that there is potential for increased geographic expansion of OROV transmission over the coming months.

| Region reporting imported casesFootnote b | Cases | TravellersNote de bas de page 1 | Cases per 10,000 returning travellers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cuba | |||

| SpainFootnote 26 | 16 | 62,337 | 2.6 |

| ItalyFootnote 8 | 4 | 15,145 | 2.6 |

| GermanyFootnote 8 | 2 | 14,703 | 1.4 |

| FloridaFootnote 27 | 30 | 137,744 | 2.2 |

| New YorkFootnote 11 | 1 | 14,037 | 0.7 |

| Brazil | |||

| SpainFootnote 26 | 0 | 105,284 | 0.0 |

| ItalyFootnote 8 | 1 | 134,733 | 0.1 |

| GermanyFootnote 8 | 0 | 69,561 | 0.0 |

| FloridaFootnote 27 | 0 | 275,773 | 0.0 |

| New YorkFootnote 11 | 0 | 82,848 | 0.0 |

|

|||

A3: What is the magnitude of health impacts from OROV infection among non-pregnant individuals?

Minor (moderate uncertainty)

OROV disease is a generally mild and self-resolving illness. Approximately 60-70% of infected individuals become symptomatic following an incubation period of 3-8 days.Footnote 1 Clinical presentation overlaps with that of other arthropod-associated diseases, including dengue, chikungunya, Zika virus disease and malaria.Footnote 5 Typical symptoms include fever, headache, arthralgia, myalgia, nausea, vomiting, chills, and photophobia; rash, retro-orbital pain and anorexia are less common.Footnote 1 Footnote 4 Serious clinical manifestations following OROV infection are uncommon but can include central nervous system (CNS) involvement, particularly aseptic meningitis and meningoencephalitis, as well as hemorrhagic symptoms. In endemic regions, OROV has been identified in 1.8% (3/165) of patients with viral CNS infections and 2.7% of meningoencephalitis cases.Footnote 28Footnote 29 A Brazilian study reported CNS involvement in 4% (12/292) of outpatient and hospitalized patients with OROV disease.Footnote 30 Hemorrhagic symptoms including petechiae, gingival bleeding and epistaxis have been reported in 2%-15% of patients.Footnote 31Footnote 32 No specific antivirals or vaccines exist against OROV, but patients usually make a full recovery, even following neurological and hemorrhagic manifestations.Footnote 30 Footnote 31 Until 2024, no OROV-associated deaths had been documented. The first two recorded deaths were reported in Brazil in July 2024, in females aged 21 and 24 years. Both had high OROV viral titres with no evidence of infection with other arboviruses, and presented with hemorrhagic and shock symptoms similar to those seen in severe dengue, along with rapidly progressing coagulopathy leading to death within 5 days of symptom onset.Footnote 33

Uncertainty in this estimate is moderate. Multiple reports from outbreaks in OROV-affected regions have documented relatively small numbers of cases with severe outcomes with typically full recovery. However, evidence is lacking regarding the incidence of severe OROV disease from longitudinal studies, specific risk factors associated with severe outcomes or death, and the clinical profile specifically among populations of travellers. The frequency of severe outcomes may also be under-estimated due to similarities in clinical presentation with other arbovirus infections, for which a presumptive diagnosis may be made instead.

A4: What is the magnitude of health impacts from OROV infection among pregnant individuals, their fetuses, and newborns?

Major (high uncertainty)

Information on OROV infection during pregnancy is limited to a few case reports. Since July 2024, 2 instances of vertical transmission associated with fetal death and 1 instance linked to the death of a 47 day-old infant with microcephaly have been documented in Brazil.Footnote 7Footnote 34Footnote 35 Evidence of OROV infection was confirmed by IgM serology or PCR in maternal and umbilical cord blood samples, and OROV was detected by PCR in fetal or neonatal samples from various tissues, as well as placental and cord blood samples in 2 instances.Footnote 34Footnote 35 In these instances, onset of symptoms compatible with OROV disease in the affected mothers were reported as early as the second month and as late as the 31st week of gestation. Footnote 34Footnote 35 Symptoms reported in these two mothers included fever, headache, rash, myalgia, retro-orbital pain and vaginal bleeding. Several further cases of vertical transmission are under investigation.Footnote 7 Vertical transmission and adverse outcomes from infection in pregnancy have not been reported in other countries to date. Although evidence on how commonly OROV infection in pregnancy leads to severe outcomes is currently limited, in assessing the impact of OROV infection during pregnancy particular consideration was given to the potential for serious, irreversible health consequences of vertical transmission on fetuses and newborns.

Uncertainty in this estimate is high. There is a lack of data specifically in pregnant individuals on the incidence of infection and frequency of severe outcomes, including vertical transmission and adverse pregnancy outcomes. There is high potential for under-detection of adverse pregnancy outcomes due to OROV, which circulates in areas with ongoing Zika virus transmission. While the causal role of OROV in fetal death and microcephaly requires further characterization, it is considered to be biologically plausible; other orthobunyaviruses in the Simbu sero-group to which OROV belongs are known to cause stillbirth and congenital malformations in livestock.Footnote 36

Question B: What is the likelihood and impact of a domestically-acquired OROV infection in a person in Canada in the next 7 months?

B1: What is the likelihood of at least one infected traveller entering Canada in the next 7 months?

High (low uncertainty)

Imported cases of OROV disease have been reported in several countries,Footnote 3 Footnote 8 Footnote 10 including Canada. The majority of these (54 of 55 as of August 30, 2024) have been in individuals returning from Cuba, which is a popular travel destination for Canadians. Based on travel volumes for 2023-24, >750,000 passengers are expected to return to or enter Canada from Cuba between August 2024 and March 2025 (IATA, unpublished data, 2023; IATA, unpublished data, 2024). Although most of this travel typically occurs during the drier months of December to March, when transmission of vector-borne diseases is lower, travel during the rainy season exceeds 40,000 passengers per month.

B2: If an infected person enters Canada, what is the likelihood of a domestically-acquired infection occurring?

Very low (moderate uncertainty)

Human-to-human transmission of OROV not involving an insect vector has not been documented to date, with the exception of vertical transmission during pregnancy. In the limited number of imported cases associated with travel to OROV-affected countries, no evidence of onward transmission has been reported to date. Iatrogenic transmission, e.g. through contaminated blood products, although theoretically possible and a known risk for other vector-borne viruses such as dengue and West Nile Virus, is considered unlikely due to the short period of viremia following OROV infection, which peaks on the second day of symptoms and declines rapidly thereafter.Footnote 37

The likelihood of vector-borne transmission of OROV within Canada during the assessment period is considered to be very low. The main vectors for OROV transmission between humans, Culicoides paraensis and possibly Culex quinquefasciatus, are not known to be present in Canada, but have been reported in parts of the United States;Footnote 12 Footnote 13 Footnote 38Footnote 39 Culicoides paraensis has been found as far north as the northeastern states of Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.Footnote 40 Culicoides sonorensis, a known vector of the Bluetongue virus in livestock, has been reported in southern regions of Alberta and British Columbia, and has been demonstrated to have the capacity to transmit OROV with low efficiency in experimental conditionsFootnote 41Footnote 42. However, its potential role in OROV transmission under natural conditions is currently unknown. Additionally, activity of these midges in Canada is very low during the fall and non-existent in winter,Footnote 43 and the short duration of viremia reduces the chances that an infected person returning from travel would transmit the virus to a domestic vector.

Uncertainty in this estimate is moderate. There is currently a lack of knowledge regarding the potential for domestic mosquito and midge species to transmit OROV within Canada. In endemic settings, OROV has also been isolated from a number of vertebrate species that are hypothesized to act as reservoirs in the sylvatic transmission cycle.Footnote 38 Notably, OROV infection has been identified in certain families of wild birds,Footnote 38 but the potential for these species to act as reservoirs for OROV within Canada is unknown. The potential role of other modes of transmission such as sexual contact, which is known to occur for some other arboviruses such as Zika, is currently unknown but has not been documented to date.

B3: If domestically-acquired infection occurs, what would be the magnitude of population-level impacts?

Minor (low uncertainty)

The occurrence of domestically-acquired OROV infections is contingent on the presence of suitable vectors within Canada. The main vectors implicated in OROV transmission in human populations in endemic settings are not known to be present in Canada, although there is a lack of evidence regarding whether other mosquito and midge species within Canada could transmit OROV under natural conditions. A plausible candidate vector, C. sonorensis, has been shown to have some capacity for OROV transmission in experimental conditions, and has been documented in certain parts of southern Canada. Based on current knowledge, if domestically-acquired infection occurred within Canada, the most likely scenario is for limited numbers of cases restricted to geographic areas with suitable vectors. However, the potential for vector-borne OROV transmission within Canada, if it is possible, is expected to be very low during the period of assessment, which includes the winter months when climatic conditions are unfavourable for mosquito and midge activity, and for the development of viruses within the vectors needed for onward transmission.

Domestically-acquired OROV infections would result in limited morbidity overall (see questions A4 and A5 above). Impacts could be more severe for pregnant individuals, their fetuses and newborns, although evidence of impacts associated with vertical transmission is currently very limited. Should domestic transmission occur, the number of cases involved is expected to be limited, therefore significant impacts on public health resources and health care capacity are not anticipated.

Limitations and knowledge gaps

This assessment is based on the information available to PHAC at the time of publication. There are notable sources of uncertainty that could influence the estimates of likelihood and impact. The key scientific uncertainties and knowledge gaps in this assessment are summarized in Table 3 below.

The qualitative method used for the likelihood estimation may also lead to an over-estimation of likelihood. This occurs because the cumulative effect of probabilities less than 100% along the risk pathway reduces the overall likelihood in a way that cannot be captured without quantitative data. This bias, however, aligns with the use of the precautionary principle.

| Domain | Knowledge gaps |

|---|---|

| Pathogen characteristics | · Orthobunyaviruses such as OROV have segmented single-stranded RNA genomes and genetic reassortment is known to be a common feature of these viruses. Early genomic evidence suggests that the current outbreaks in Brazil involve novel reassortant viruses.Footnote 44 Footnote 45 Footnote 46 However, the implications of these reassortments for transmissibility, infectivity or pathogenicity is currently unknown |

| Exposure | · There is limited information regarding the extent of exposure to OROV in outbreak-affected countries, both among the general population and travellers specifically |

| Susceptibility | · Individual risk factors for severe illness and death due to OROV are not well understood · It is unknown whether pregnant individuals are more susceptible to OROV infection and/or severe OROV disease relative to the general population; among infected pregnant individuals, the frequency of vertical transmission, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes, are unknown |

| Spread | · There is currently no documented evidence of human-to-human transmission other than through vertical transmission during pregnancy; however, the potential for OROV transmission through other routes, e.g., contaminated blood products, sexual contact, is unknown · The potential for domestic mosquito and biting midge within Canada to transmit OROV is unclear · The potential for introduction and establishment of competent vectors into Canada from other countries, e.g., through population movements, trade and/or climate change, is unknown · The role of non-human vertebrate animal species in the OROV transmission cycle is not fully understood, and the potential role of animal species as OROV reservoirs within Canada is unclear |

| Impacts | · There is currently very limited information on the frequency and magnitude of short- and long-term impacts resulting from vertical transmission of OROV in pregnant individuals |

| Interventions | · The effectiveness of vector control measures for reducing OROV transmission in outbreak-affected countries is unknown · Information is lacking on the effectiveness of bite precautions specifically for the main OROV vector, but effectiveness is assumed based on studies of repellent use against similar insect populationsFootnote 47 Footnote 48 |

Appendix A: Rapid risk assessment methods

This assessment was led by DSFB-SIIRA, within the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) between August 12, 2024, and September 20, 2024, in collaboration with a multi-sectoral team (see Appendix B for a list of contributors). The rapid risk assessment (RRA) methodology used by DSFB-SIIRA has been adapted from the Joint Risk Assessment Operational Tool (JRA OT) to assess the risk posed by zoonotic disease hazards developed jointly by the World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH).Footnote 49 A detailed description of the methodology is published in the journal Canada Communicable Disease Report.Footnote 50

Criteria to estimate likelihood, impact, and uncertainty

| Estimate | Criteria |

|---|---|

| High | The situation described in the risk assessment question is highly likely to occur (i.e. is expected to occur in most circumstances) |

| Moderate | The situation described in the risk assessment question is likely to occur |

| Low | The situation described in the risk assessment question is unlikely to occur |

| Very low | The situation described in the risk assessment question is very unlikely to occur (i.e. is expected to occur only under exceptional circumstances) |

| Estimate | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Severe | Severe impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income) |

| Major | Major impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income) |

| Moderate | Moderate impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income) |

| Minor | Minor impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income) |

| Minimal | Negligible or no impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income) |

| Estimate | Criteria |

| Severe | Potential pandemic in the general population or large numbers of case reports, with significant impact on the well-being of the population. Severe impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income). Effect extremely serious and/or irreversible. |

| Major | Case reports with moderate to significant impact on the well-being of the population. Moderate to significant impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income) affecting a larger proportion of the population and/or several regions. Effect serious with substantive consequences, but usually reversible. |

| Moderate | Case reports with low to moderate impact on the well-being of the population. Low to moderate impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income) affecting a larger proportion of the population and/or several regions. Effect noticeable with important consequences, but usually reversible. |

| Minor | Rare case reports, mainly in small at-risk groups, with moderate to significant impact on the well-being of the population. Moderate to significant impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income) on a small proportion of the population and/or small areas (regional level or below). Effect marginal, but insignificant and/or reversible. |

| Minimal | No or very rare case reports with low to moderate impact on the well-being of the population. Negligible or no impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income). |

| Uncertainty | Criteria |

| Very High | Lack of data or reliable information; results based on crude speculation only |

| High | Limited data or reliable information available; results based on educated guess |

| Moderate | Some gaps in availability or reliability of data and information, or conflicting data; results based on limited consensus |

| Low | Reliable data and information available but may be limited in quantity, or be variable; results based on expert consensus |

| Very low | Reliable data and information are available in sufficient quantity; results strongly anchored in empiric data or concrete information |

Appendix B: Acknowledgements

Completed by the Public Health Agency of Canada's Centre for Surveillance, Integrated Insights and Risk Assessment within the Data, Surveillance and Foresight Branch.

OROV Rapid Risk Assessment Team:

Rukshanda Ahmad, Sharon Calvin, Raquel Farias, Rashmi Narkar, Oluwafemi Oluwole, Sandra Radons Arneson, Sheenu Singla, Clarence Tam, Dana Tschritter, Shelley Veilleux, Fushan Zhang

The individuals listed below are acknowledged for their contributions to this report.

Other individuals from various programs across PHAC:

Jillian Blackmore, Samuel Bonti-Ankomah, Leanne Bulsink, Annie-Claude Bourgeois, Lesley Doering, Rhea Ferguson, Theresa Lee, Antoinette Ludwig, Janice Merhej, Jennifer Mihowich, Nick Ogden, Michael Routledge, Erin Schillberg, Janavi Shetty, Marsha Taylor, Mandy Whitlock, Jennifer Whitteker, Heidi Wood

Other federal departments:

- Agriculture and Agri-food Canada: Shaun Dergousoff

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency: Nariman Shahhosseini

- Health Canada: Chris Hinds, Lidia Guarna, Katrina Marchand, Nicola Maule

Other organizations:

- Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel: Yen Bui, Steve Schofield

- Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada: Deborah Money, Jeffrey Wong

Footnotes

- Footnote a

-

Any person normally residing in Canada who travels abroad.

- Footnote b

-

Those countries with locally circulating OROV at the time of assessment.

- Footnote c

-

The likelihood of infection with the next seven months is assessed (September 2024 to March 2025) but impacts may occur within a longer timeframe.

References

- Footnote 1

-

Sakkas H, Bozidis P, Franks A, Papadopoulou C. Oropouche Fever: A Review. Viruses. 2018;10(4):175. doi:10.3390/v10040175

- Footnote 2

-

Romero-Alvarez D, Escobar LE. Oropouche fever, an emergent disease from the Americas. Microbes Infect. 2018;20(3):135-146. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2017.11.013

- Footnote 3

-

Pan American Health Organization. Public Health Risk Assessment related to Oropouche Virus (OROV) in the Region of the Americas. August 3, 2024. Accessed August 8, 2024. https://www.paho.org/en/documents/public-health-risk-assessment-related-oropouche-virus-orov-region-americas-3-august-2024

- Footnote 4

-

Wesselmann KM, Postigo-Hidalgo I, Pezzi L, et al. Emergence of Oropouche fever in Latin America: a narrative review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024;24(7):e439-e452. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00740-5

- Footnote 5

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Alert Network (HAN) - 00515 | Increased Oropouche Virus Activity and Associated Risk to Travelers. August 16, 2024. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2024/han00515.asp

- Footnote 6

-

Pan American Health Organization. Public Health Risk Assessment related to Oropouche Virus (OROV) in the Region of the Americas. February 9, 2024. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.paho.org/en/documents/public-health-risk-assessment-related-oropouche-virus-orov-region-americas-9-february

- Footnote 7

-

Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Informe Semanal no 10 - Arboviroses Urbanas - SE 33 | 19 de Agosto de 2024. Accessed August 26, 2024. https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/saude-de-a-a-z/a/arboviroses/informe-semanal/informe-semanal-sna-no10.pdf/view

- Footnote 8

-

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Threat assessment brief: Oropouche virus disease cases imported to the European Union. August 9, 2024. Accessed August 9, 2024. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/threat-assessment-brief-oropouche-virus-disease-cases-imported-european-union

- Footnote 9

-

Gobierno de Canarias. Sanidad notifica otros tres casos importados de virus Oropouche en Canarias. Accessed August 30, 2024. https://www3.gobiernodecanarias.org/noticias/sanidad-notifica-otros-tres-casos-importados-de-virus-oropouche-en-canarias/

- Footnote 10

-

Florida Health. 2024 Weekly Florida Arbovirus Surveillance Reports (Week 33: August 11-17, 2024). Accessed August 20, 2024. https://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/mosquito-borne-diseases/_documents/2024-33-arbovirus-surveillance.pdf

- Footnote 11

-

Morrison A. Oropouche Virus Disease Among U.S. Travelers — United States, 2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7335e1

- Footnote 12

-

McGregor BL, Shults PT, McDermott EG. A Review of the Vector Status of North American Culicoides (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) for Bluetongue Virus, Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus, and Other Arboviruses of Concern. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2022;9(4):130-139. doi:10.1007/s40475-022-00263-8

- Footnote 13

-

Peach DAH, Matthews BJ. The Invasive Mosquitoes of Canada: An Entomological, Medical, and Veterinary Review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2022;107(2):231-244. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.21-0167

- Footnote 14

-

Pan American Health Organization. Epidemiological Alert Oropouche in the Region of the Americas - 1 August 2024. Epidemiological Alert Oropouche in the Region of the Americas - 1 August 2024. August 1, 2024. Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.paho.org/en/documents/epidemiological-alert-oropouche-region-americas-1-august-2024

- Footnote 15

-

Cruz ACR, Prazeres A do SC dos, Gama EC, et al. [Serological survey for arboviruses in Juruti, Pará State, Brazil]. Cad Saude Publica. 2009;25(11):2517-2523. doi:10.1590/s0102-311x2009001100021

- Footnote 16

-

Tavares-Neto J, Freitas-Carvalho J, Nunes MRT, et al. [Serologic survey for yellow fever and other arboviruses among inhabitants of Rio Branco, Brazil, before and three months after receiving the yellow fever 17D vaccine]. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2004;37(1):1-6. doi:10.1590/s0037-86822004000100001

- Footnote 17

-

Catenacci LS, Ferreira MS, Fernandes D, et al. Individual, household and environmental factors associated with arboviruses in rural human populations, Brazil. Zoonoses Public Health. 2021;68(3):203-212. doi:10.1111/zph.12811

- Footnote 18

-

Dixon KE, Travassos da Rosa AP, Travassos da Rosa JF, Llewellyn CH. Oropouche virus. II. Epidemiological observations during an epidemic in Santarém, Pará, Brazil in 1975. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;30(1):161-164.

- Footnote 19

-

Watts DM, Phillips I, Callahan JD, Griebenow W, Hyams KC, Hayes CG. Oropouche virus transmission in the Amazon River basin of Peru. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56(2):148-152. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.148

- Footnote 20

-

World Health Organization. Oropouche virus disease - Cuba. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2024-DON521

- Footnote 21

-

Cubadebate. 18vo Curso Internacional de Dengue y otros arbovirus emergentes: La lección primera es no subestimar. Cubadebate - Cubadebate, Por la Verdad y las Ideas. August 19, 2024. Accessed August 23, 2024. http://www.cubadebate.cu/noticias/2024/08/19/18vo-curso-internacional-de-dengue-y-otros-arbovirus-emergentes-la-leccion-primera-es-no-subestimar/

- Footnote 22

-

United Nations. International Migrant Stock, 2020. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock

- Footnote 23

-

Statistics Canada. National Travel Survey, 2018. Accessed August 26, 2024. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/242500012019001

- Footnote 24

-

Statistics Canada. National Travel Survey, 2019. Accessed August 26, 2024. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/242500012020001

- Footnote 25

-

Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Painel Epidemiologico Oropouche. 2024. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/saude-de-a-a-z/o/oropouche/painel-epidemiologico/painel-epidemiologico-oropouche

- Footnote 26

-

20minutos. El virus oropouche deja ya 16 casos en España y los expertos alertan del "preocupante" aumento de infecciones por insectos. www.20minutos.es - Últimas Noticias. August 27, 2024. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.20minutos.es/noticia/5587812/0/virus-oropouche-deja-casos-espana-expertos-alertan-preocupante-aumento-infecciones-insectos/

- Footnote 27

-

Florida Health. 2024 Weekly Florida Arbovirus Surveillance Reports (Week 34: August 18-24, 2024). Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/mosquito-borne-diseases/_documents/2024-34-arbovirus-surveillance.pdf

- Footnote 28

-

Bastos MS, Lessa N, Naveca FG, et al. Detection of Herpesvirus, Enterovirus, and Arbovirus infection in patients with suspected central nervous system viral infection in the Western Brazilian Amazon. J Med Virol. 2014;86(9):1522-1527. doi:10.1002/jmv.23953

- Footnote 29

-

Bastos M de S, Figueiredo LTM, Naveca FG, et al. Identification of Oropouche Orthobunyavirus in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Three Patients in the Amazonas, Brazil. Am Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86(4):732-735. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0485

- Footnote 30

-

Pinheiro F, Rocha AG, Freitas R, et al. Meningite associada as infeccoes por virus Oropouche. Rev Inst Med Trop Säo Paulo. Published online 1982:246-251.

- Footnote 31

-

Mourão MPG, Bastos MS, Gimaque JBL, et al. Oropouche Fever Outbreak, Manaus, Brazil, 2007–2008. Emerg Infect Dis J. 2009;15(12):2063. doi:10.3201/eid1512.090917

- Footnote 32

-

Alvarez-Falconi PP, Ríos Ruiz BA. [Oropuche fever outbreak in Bagazan, San Martin, Peru: epidemiological evaluation, gastrointestinal and hemorrhagic manifestations]. Rev Gastroenterol Peru Organo Of Soc Gastroenterol Peru. 2010;30(4):334-340.

- Footnote 33

-

Bandeira AC, Barbosa ACFN da S, Souza M, et al. Clinical profile of Oropouche Fever in Bahia, Brazil: unexpected fatal cases. Published online July 16, 2024. doi:10.1590/SciELOPreprints.9342

- Footnote 34

-

Nota Técnica Conjunta no 135/2024-SVSA/SAPS/SAES/MS — Ministério da Saúde. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/notas-tecnicas/2024/nota-tecnica-conjunta-no-135-2024-svsa-saps-saes-ms/view

- Footnote 35

-

Filho CG, Neto ASL, Maia AMPC, et al. Vertical Transmission of Oropouche Virus in a Newly Affected Extra-Amazon Region: A Case Study of Fetal Infection and Death in Ceará, Brazil. Published online September 2, 2024. doi:10.1590/SciELOPreprints.9667

- Footnote 36

-

O'Connor TW, Hick PM, Finlaison DS, Kirkland PD, Toribio JALML. Revisiting the Importance of Orthobunyaviruses for Animal Health: A Scoping Review of Livestock Disease, Diagnostic Tests, and Surveillance Strategies for the Simbu Serogroup. Viruses. 2024;16(2):294. doi:10.3390/v16020294

- Footnote 37

-

Cardoso BF, Serra OP, Heinen LB da S, et al. Detection of Oropouche virus segment S in patients and inCulex quinquefasciatus in the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2015;110:745-754. doi:10.1590/0074-02760150123

- Footnote 38

-

Files MA, Hansen CA, Herrera VC, et al. Baseline mapping of Oropouche virology, epidemiology, therapeutics, and vaccine research and development. Npj Vaccines. 2022;7(1):38. doi:10.1038/s41541-022-00456-2

- Footnote 39

-

Gorris ME, Bartlow AW, Temple SD, et al. Updated distribution maps of predominant Culex mosquitoes across the Americas. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14(1):547. doi:10.1186/s13071-021-05051-3

- Footnote 40

-

Borkent A, William L. Grogan J. <strong>Catalog of the New World Biting Midges North of Mexico (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae)</strong>. Zootaxa. 2009;2273(1):1-48. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2273.1.1

- Footnote 41

-

McGregor BL, Connelly CR, Kenney JL. Infection, Dissemination, and Transmission Potential of North American Culex quinquefasciatus, Culex tarsalis, and Culicoides sonorensis for Oropouche Virus. Viruses. 2021;13(2):226. doi:10.3390/v13020226

- Footnote 42

-

Lysyk TJ, Dergousoff SJ. Distribution of Culicoides sonorensis (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) in Alberta, Canada. J Med Entomol. 2014;51(3):560-571. doi:10.1603/ME13239

- Footnote 43

-

Lysyk TJ. Seasonal Abundance, Parity, and Survival of Adult Culicoides sonorensis (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) in Southern Alberta, Canada. J Med Entomol. 2007;44(6):959-969. doi:10.1093/jmedent/44.6.959

- Footnote 44

-

Naveca FG, Almeida TAP de, Souza V, et al. Emergence of a novel reassortant Oropouche virus drives persistent human outbreaks in the Brazilian Amazon region from 2022 to 2024. Published online July 24, 2024:2024.07.23.24310415. doi:10.1101/2024.07.23.24310415

- Footnote 45

-

Scachetti GC, Forato J, Claro IM, et al. Reemergence of Oropouche virus between 2023 and 2024 in Brazil. Published online July 30, 2024:2024.07.27.24310296. doi:10.1101/2024.07.27.24310296

- Footnote 46

-

Iani FC de M, Pereira FM, Oliveira EC de, et al. Rapid Viral Expansion Beyond the Amazon Basin: Increased Epidemic Activity of Oropouche Virus Across the Americas. Published online August 6, 2024:2024.08.02.24311415. doi:10.1101/2024.08.02.24311415

- Footnote 47

-

Trigg JK. Evaluation of a eucalyptus-based repellent against Culicoides impunctatus (Diptera:Ceratopogonidae) in Scotland. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1996;12(2 Pt 1):329-330.

- Footnote 48

-

Carpenter S, Groschup MH, Garros C, Felippe-Bauer ML, Purse BV. Culicoides biting midges, arboviruses and public health in Europe. Antiviral Res. 2013;100(1):102-113. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.07.020

- Footnote 49

-

World Health Organization/The World Organization for Animal Health/Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Joint Risk Assessment Operational Tool (JRA OT): An Operational Tool of the Tripartite Zoonoses Guide. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2020. https://www.who.int/initiatives/tripartite-zoonosis-guide/joint-risk-assessment-operational-tool

- Footnote 50

-

Anand SP, Tam CC, Calvin S, et al. Estimating public health risks of infectious disease events: A Canadian approach to rapid risk assessment. Can Commun Dis Rep Releve Mal Transm Au Can. 2024;50(9):282-293. doi:10.14745/ccdr.v50i09a01