Report from the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System: Mood and Anxiety Disorders in Canada, 2016

Table of Contents

- Report Highlights

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Mood and Anxiety Disorders in the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System (CCDSS)

- 3. Key Findings

- 4. Conclusion

- Glossary

- Acknowledgements

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Appendix C

- Appendix D

- References

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 2.1 MB, 44 pages)

Report Highlights

Purpose of this report

This report, Mood and Anxiety Disorders in Canada, 2016 is the first publication to include administrative health data from the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System (CCDSS) for the national surveillance of mood and anxiety disorders among Canadians aged one year and older. It features the most recent nationally complete CCDSS data available (fiscal year 2009/10), as well as trend data spanning over a decade (1996/97 to 2009/10). The data presented in this report, and subsequent updates, can be accessed via the Public Health Agency of Canada's Chronic Disease Infobase Data Cubes. Data Cubes are interactive databases that allow users to quickly create tables and graphs using their Web browser.

Mood and anxiety disorders

Mood and anxiety disorders are the most common types of mental illnesses in Canada and throughout the world. Mood disorders are characterized by the lowering or elevation of a person's mood while anxiety disorders are characterized by excessive and persistent feelings of apprehension, worry and even fear. Both types of disorders may have a major impact on an individual's everyday life and can range from single short lived episodes to chronic disorders. Professional care combined with active engagement in self-management strategies can foster recovery and improve the well-being of people affected by these disorders, ultimately enabling them to lead full and active lives.

Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System

The CCDSS is a collaborative network of provincial and territorial chronic disease surveillance systems, supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada. It identifies chronic disease cases from provincial and territorial administrative health databases, including physician billing claims and hospital discharge abstract records, linked to provincial and territorial health insurance registries. Data on all residents who are eligible for provincial or territorial health insurance (about 97% of the Canadian population) are captured in the health insurance registries; thus, the CCDSS coverage is near-universal. Case definitions are applied to these linked databases and data are then aggregated at the provincial and territorial level before being submitted to the Public Health Agency of Canada for reporting at the provincial, territorial and national levels.

In 2010, the CCDSS was expanded to track and report on mental illness overall, as well as mood and anxiety disorders in the Canadian population. The CCDSS identified individuals as having used health services for mood and anxiety disorders if they met a minimum requirement of at least one physician claim, or one hospital discharge abstract in a given year listing diagnostic codes for mood and anxiety disorders from the 9th or 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases. Due to the lack of specificity in the diagnoses and data capture, the surveillance of mood and anxiety disorders as separate entities was not possible. Therefore, within this report, the term "mood and anxiety disorders" refers to those who have used health services for mood disorders only, anxiety disorders only, or both mood and anxiety disorders.

The CCDSS may capture individuals who do not meet all standard diagnostic criteria for mood or anxiety disorders but were assigned a diagnostic code based on clinical assessment. Conversely, the CCDSS does not capture individuals meeting all standard diagnostic criteria for mood or anxiety disorders who did not receive a relevant diagnostic code (includes those who sought care but were not captured in provincial and territorial administrative health databases and those who have not sought care at all). For these reasons, the CCDSS estimates represent the prevalence of health service use for mood and anxiety disorders, rather than the prevalence of diagnosed mood and anxiety disorders.

Key findings

About three-quarters of Canadians who used health services for a mental illness annually consulted for mood and anxiety disorders. In 2009/10, almost 3.5 million Canadians (or 10%) used health services for mood and anxiety disorders. Although high, the proportion of Canadians using health services for these disorders remained relatively stable between 1996/97 and 2009/10 (age standardized prevalence ranged from 9.4% to 10.5%). The highest prevalence was observed among those aged 30 to 54 followed by those 55 years and older, while the largest relative increases in prevalence were found among children and youth (aged 5 to 14 years); although in absolute terms, these increases were less than one percent.

Adolescent and adult females, especially those middle-aged, were more likely to use health services for mood and anxiety disorders compared to males of the same age. A combination of behavioural, biological, and sociocultural factors may explain this sex difference. Whereas males aged 5 to 9 years were more likely to use health services for mood and anxiety disorders compared to females of the same age. This may be explained by the frequent co-occurrence of mood and anxiety disorders with conduct and hyperactivity attention deficit disorders, which are more commonly diagnosed in males of this age.

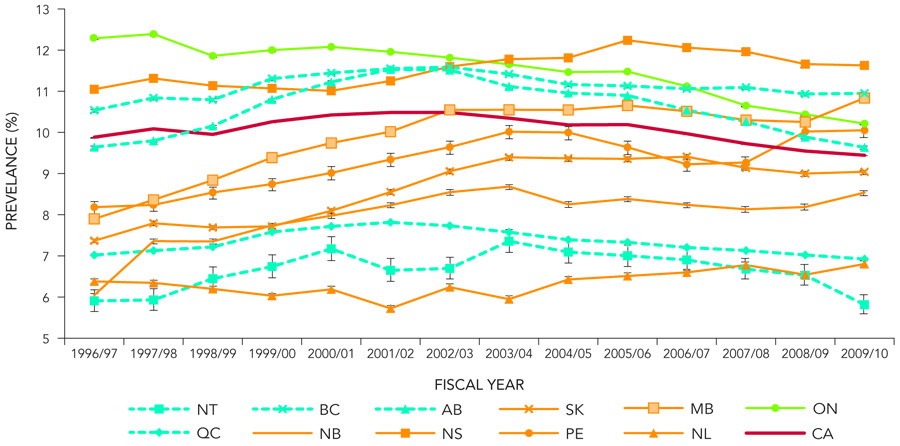

In 2009/10, Nova Scotia had the highest age-standardized prevalence of the use of health services for mood and anxiety disorders (11.6%), while the lowest was observed in the Northwest Territories (5.8%). Provincial and territorial variations were observed over the surveillance period, including a significant annual increase in the age-standardized prevalence in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador, and a significant annual decrease in Ontario. These jurisdictional variations may in part be explained by differences in detection and treatment practices as well as differences in data coding, database submissions, remuneration models and shadow billing practices.

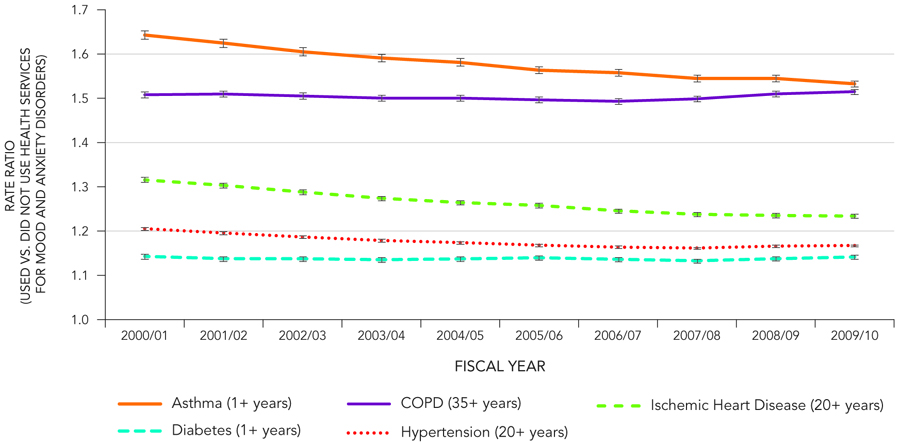

A higher prevalence of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and to a lesser degree ischemic heart disease, diabetes and hypertension, was observed among people who used health services for mood and anxiety disorders compared to those who did not. While the relationships remain poorly understood, it is well recognized that people with depressive and anxiety disorders are at increased risk of developing other chronic diseases or conditions, and that people affected by chronic physical diseases or conditions are at increased risk of experiencing depression and anxiety.

Future plans

Future work involving the CCDSS related to mood and anxiety disorders includes but is not limited to: the ongoing collection and reporting of data on mood and anxiety disorders; developing an approach to study the chronicity of mood and anxiety disorders; and exploring other comorbid diseases and conditions.

1. Introduction

Mental illnesses are characterized by alterations in thinking, mood and/or behaviour and associated with significant distress and impaired functioning.Reference 1 As such, they have the potential to impact every aspect of an individual's life, including relationships, education, work, and community involvement. These impacts at the individual level also have repercussions on the overall economy.Reference 2,Reference 3,Reference 4,Reference 5,Reference 6 There are many different types of mental illness, but mood and anxiety disorders are among the most common in Canada and worldwide. Mood and anxiety disorders are a result of a complex interplay of various biological, genetic, economic, social and psychological factors.Reference 7 This report focuses on these disorders combined; in other words, it covers individuals living with mood disorders only, anxiety disorders only, or both mood and anxiety disorders.

Mood disorders

Mood disorders affect the way an individual feels and may involve depressive or manic episodes.Reference 1 Individuals experiencing an episode of depression may feel worthless, helpless or hopeless, may lose interest in their usual activities, experience a change in appetite, suffer from disturbed sleep, have decreased energy, poor concentration and/or difficulty making decisions. While individuals in a manic episode may have an excessively high or elated mood, unreasonable optimism or poor judgment, racing thoughts, decreased sleep, extremely short attention span and rapid shifts to rage or sadness. They include the following four classifications: major depressive disorder; bipolar disorder; dysthymic disorder; and perinatal/postpartum depression. Mood disorders can affect individuals of all ages, but usually develop in adolescence or young adulthood. They are more frequent among females than males with the exception of bipolar disorder which affects women and men equally. Known risk factors include family history, previous episodes of depression, stress, chronic medical conditions and use of certain medications. Traumatic life events, being in difficult or abusive relationships and socio-economic factors such as inadequate income and housing also play a role.

Anxiety disorders

Individuals with anxiety disorders experience episodes of excessive and persistent feelings of apprehension, worry and even fear that may cause the individual affected to avoid situations or develop compulsive rituals that help to reduce these symptoms.Reference 1 These disorders are characterized by "intense and prolonged feelings of fear and distress that occur out of proportion to the actual threat or danger" where "the feelings of fear and distress interfere with normal daily functioning."

There are seven main types of anxiety disorders: generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia or social anxiety disorder, specific phobias, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder and agoraphobia. These disorders affect females more frequently than males, and symptoms usually develop during childhood, adolescence or in early adulthood. Known risk factors include family history, personal history of mood or anxiety disorder, history of stressful life events or trauma, in particular childhood abuse. Chronic medical conditions, use of certain medications, drug abuse, loneliness, low education and adverse parenting may also increase the risk of developing an anxiety disorder.Reference 8

Comorbidity of mood and anxiety disorders

Mood and anxiety disorders frequently coexist with other chronic diseases or conditions. Many bidirectional associations have been observed, although these associations remain poorly understood. For instance, the early onset of depressive and anxiety disorders has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of developing heart disease, asthma, arthritis, chronic back pain and chronic headaches in adult life.Reference 9 In addition, mood and anxiety disorders can lead to unhealthy behaviours that increase the risk of developing or exacerbating other chronic diseases or conditions.Reference 9,Reference 10 For example, people who report having depressive and anxiety disorders are more likely to smokeReference 11,Reference 12—a major risk factor for chronic respiratory conditions.Reference 13 Conversely, depressive and anxiety disorders may result from the burden of living with a chronic disease or conditionReference 1,Reference 14,Reference 15 which may be due to a number of factors including physiologic changes and functional impairments associated with the chronic disease or condition.Reference 15

Treatment

Professional care combined with active engagement in self-management strategies can foster recovery and improve the well-being of people affected by mood and anxiety disorders, ultimately enabling them to lead full and active lives.Reference 7 Treatment comes in many forms, including psychotherapy, counselling and medication, and they are often used jointly.Reference 8,Reference 16,Reference 17 Community supports—such as outreach services and income (i.e. social assistance), vocational and housing-related supports—may also be provided. In Canada, treatment and supports for mental illness are provided across many settings, such as family physician and psychiatrist offices, hospitals, outpatient programs and clinics, and community agencies. Many people also pay out of pocket for treatment from private practitioners (e.g. psychotherapy by psychologists) or for private residential care.

Challenges for mood and anxiety disorder surveillance

The surveillance of mood and anxiety disorders is particularly challenging compared with that of other chronic diseases or conditions because of varying diagnostic accuracy. Unlike diseases or conditions with established physiological markers, mental illnesses such as mood and anxiety disorders, are like chronic pain, in that there are currently no objective tests with which to assign a diagnosis. A diagnosis is based on symptoms reported by the individual affected and signs observed by the physician or by relatives.Reference 18

The varying duration of mood and anxiety disorder episodes, from one person to another, poses another unique surveillance challenge, as measures of true incidence are difficult to estimate. However, it is possible to estimate various period prevalences. For instance, it was estimated that 12.6% of Canadians aged 15 and older will experience a mood disorder during their lifetime, while 8.7% will experience generalized anxiety disorder. During a 12 month period, these prevalence estimates were 5.4% and 2.6%, respectively.Reference 19

Many environmental, social and cultural factors may affect the rate at which people seek care for signs and symptoms associated with mood and anxiety disorders, and how physicians assess them. However, there have been efforts to increase awareness of the symptoms and impacts of these disorders, and to improve understanding and acceptance. Without fear of judgment or discrimination, more people might be open to seeking care for their symptoms or speaking more openly about their emotions.

Purpose of this report

This report is the first publication to include administrative health data from the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System (CCDSS) for the national surveillance of mood and anxiety disorders among Canadians aged one year and older. It features the most recent nationally complete CCDSS data available (fiscal year 2009/10), as well as trend data spanning over a decade (1996/97 to 2009/10). Prior to the release of this report, the Public Health Agency of Canada published the report, Reference 20 Mood and anxiety disorders are the focus of this report since they are the most common types of mental illness in Canada and worldwide. The data presented within this report, and subsequent updates, can be accessed via the Public Health Agency of Canada's Chronic Disease Infobase Data Cubes. Data Cubes are interactive databases that quickly allow users to create tables and graphs using their Web browser.

2. Mood and Anxiety Disorders in the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System (CCDSS)

Methods

The CCDSS is a collaborative network of provincial and territorial chronic disease surveillance systems, supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada. Chronic disease cases are identified from provincial and territorial administrative health databases, including physician billing claims and hospital discharge abstract records, linked to provincial and territorial health insurance registries. Data on all residents who are eligible for provincial or territorial health insurance (about 97% of the Canadian population) are captured in the health insurance registries; thus, the CCDSS coverage is near-universal. Case definitions are applied to these linked databases and data are then aggregated at the provincial and territorial level before being submitted to the Public Health Agency of Canada for reporting at the provincial, territorial and national levels. In 2010, the CCDSS was expanded to track and report on mental illness overallReference 20 as well as, mood and anxiety disorders in the Canadian population. For information on the current scope of the CCDSS, refer to Appendix A.

The CCDSS identified individuals as having used health services for mood and anxiety disorders if they met the following criteria: at least one physician claim listing a mood and/or anxiety disorder diagnostic code in the first field, or one hospital discharge abstract listing a mood and/or anxiety disorder diagnostic code in the most responsible diagnosis field using ICD-9 or ICD-9-CM codes, or their ICD-10-CA equivalents (Table 1). Using this case definition, individuals must qualify as a case in a given fiscal year to be counted in that fiscal year; therefore, estimates represent the annual prevalence.

A combined case definition for mood and anxiety disorders was implemented as the surveillance of these disorders separately was not possible due to the lack of specificity in the diagnosis and data capture.Reference 21 Therefore, the term "mood and anxiety disorders" throughout this report refers to those who have used health services for mood disorders only, anxiety disorders only, or both mood and anxiety disorders.

| ICD-9 or ICD-9-CM | ICD-10-CA | |

|---|---|---|

| Mood and anxiety disorders | 296, 300, and 311 | F30 to F48, and F68 |

The ICD codes included in the above CCDSS case definitions are associated with the following disorders:

- Mood disorders

-

- Major depressive disorder;

- Bipolar disorder;

- Dysthymic disorder;

- Depressive disorders not elsewhere classified including perinatal and postpartum depression.Footnote i

- Anxiety disorders

-

- Generalized anxiety disorder;

- Social phobia or social anxiety disorder;

- Specific phobias;

- Reaction to severe stress, and adjustment disorders which includes post-traumatic stress disorder;Footnote ii

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder;

- Panic disorder; and

- Agoraphobia.

The CCDSS may capture individuals who do not meet all standard diagnostic criteria for mood and anxiety disorders but were assigned a diagnostic code based on clinical assessment. Conversely, the CCDSS does not capture individuals meeting all standard diagnostic criteria for mood and anxiety disorders who did not receive a relevant diagnostic code (includes those who sought care but were not captured in provincial and territorial administrative health databases and those who have not sought care at all). For these reasons, the CCDSS estimates represent the prevalence of health service use for mood and anxiety disorders, rather than the prevalence of diagnosed mood and anxiety disorders. For information on the feasibility and validation work carried out to develop this case definition and expand the CCDSS to include mood and anxiety disorders, refer to Appendix B.

This report features data from all provinces and territories, except for Nunavut (NU)Footnote iii and the Yukon Territory (YT),Footnote iv which together represent approximately 0.2% of the total Canadian population.Footnote v Provincial and territorial health insurance registries are the source for each individual's demographic information, and age is calculated as of mid-fiscal year, on October 1st. The population count consists of the total number of insured people in the provinces and territories (excluding NU and YT) that are captured in the resident health insurance registry in the specified fiscal year.

Limitations

While the coverage for the CCDSS is near-universal, exclusions include Canadians covered under federal health programs, such as refugee protection claimants, full-time members of the Canadian Forces, eligible veterans, individuals in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and federal penitentiary inmates. Furthermore, the CCDSS does not capture eligible cases who: were seen by a salaried physician who does not shadow bill; sought care from a community- based clinic or private setting; received mental health services in a hospital that does not submit discharge abstract data to the Discharge Abstract Database (or in the case of Quebec, the Maintenance et exploitation des données pour l'étude de la clientèle hospitalière or, MED-ÉCHO); sought care but did not receive a relevant mood or anxiety disorder diagnostic code; or did not seek care at all. For these reasons, the data in this report likely underestimate the use of health services for mood and anxiety disorders in Canada. For more information on the population coverage for mood and anxiety disorders in the CCDSS, refer to Appendix C.

Another limitation relates to the difficulty in disentangling mood from anxiety disorders using CCDSS data at a national level. A feasibility study carried out to evaluate the usefulness of administrative data for the surveillance of treated mood and anxiety disorders in Canada demonstrated that the results were comparable across provinces when these two disorders were combined however; considerable inter-provincial variations were observed when these disorders were considered separately. These variations were likely due to a lack of specificity in the diagnosis and data capture.Reference 21

3. Key Findings

Reminder!

The CCDSS may capture individuals who do not meet all standard diagnostic criteria for mood and anxiety disorders but were assigned a diagnostic code based on clinical assessment. Conversely, the CCDSS does not capture individuals meeting all standard diagnostic criteria for mood and anxiety disorders who did not receive a relevant diagnostic code (includes those who sought care but were not captured in provincial and territorial administrative health databases and those who have not sought care at all). For these reasons, the CCDSS estimates represent the prevalence of health service use for mood and anxiety disorders rather than the prevalence of diagnosed mood and anxiety disorders.

3.1 People using health services for mood and anxiety disorders

3.1.1 Population aged one year and older

Mood and anxiety disorders are the most prevalent subgroup of mental disorders in Canada. About three-quarters of the Canadian population aged one year and older that used health services for a mental illness annually,Reference 20 used those services for mood and anxiety disorders.

- In 2009/10 approximately 3.5 million (or 10%) Canadians used health services for mood and anxiety disorders (2.2 million females and 1.3 million males; figure results not shown).

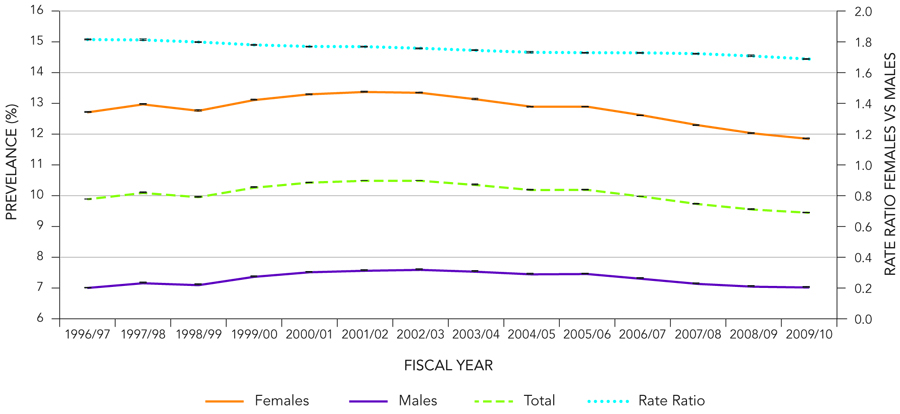

- The age-standardized prevalence of the use of health services for mood and anxiety disorders among Canadians remained relatively stable over the 14-year surveillance period (1996/97 to 2009/10), ranging from 9.4% to 10.5% (linear trend not statistically significant). Although, between 2001/02 and 2002/03, a small peak in the prevalence was observed; however, the prevalence declined to a level similar to that in 1996/97 thereafter (Figure 1).

- Overall, the age-standardized prevalence was consistently higher among females compared to males over the surveillance period; however, the age-standardized prevalence rate ratios comparing females to males decreased slightly (from 1.8 to 1.7), with a statistically significant annual percent decrease of 0.5% (Figure 1).

The slight decrease in the age-standardized prevalence after 2002/03 may in part be explained by the introduction of ICD-10-CA in hospitals across Canada between 2001/02 and 2006/07 as it has been shown that ICD-10-CA is less sensitive than ICD-9-CM in capturing depression from hospital discharge abstract records.Reference 22 In addition, an increasing proportion of physicians paid by salary (rather than fee-for-service) may have occurred in the latter part of the surveillance period. In the absence of shadow billing, this shift in remuneration would reduce the number of physician billing claims submitted to provincial and territorial governments. However, despite the described changes in data coding and remuneration models, it is important to note that the linear trend was not statistically significant, and that the absolute decrease in the overall prevalence over the surveillance period was less than one percent.

Figure 1. Age-standardizedFigure 1 footnote † annual prevalence (%) and rate ratios of the use of health services for mood and anxiety disorders among people aged one year and older, by sex, Canada,Figure 1 footnote * 1996/97 to 2009/10

Figure 1 - Text Equivalent

| Fiscal year | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996/97 | 1997/98 | 1998/99 | 1999/00 | 2000/01 | 2001/02 | 2002/03 | 2003/04 | 2004/05 | 2005/06 | 2006/07 | 2007/08 | 2008/09 | 2009/10 | |

| Females | 12.7 | 13.0 | 12.8 | 13.1 | 13.3 | 13.4 | 13.3 | 13.1 | 12.9 | 12.9 | 12.6 | 12.3 | 12.0 | 11.8 |

| Males | 7.0 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.5 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| Total | 9.9 | 10.1 | 10.0 | 10.3 | 10.4 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 10.3 | 10.2 | 10.2 | 10.0 | 9.7 | 9.5 | 9.4 |

| Rate ratio | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

3.1.2 Population aged 1 to 19 years

- In 2009/10, approximately 258 thousand (or 3.1%) Canadian children and youth used health services for mood and anxiety disorders (figure results not shown).

- The prevalence among children and youth increased with age, with the highest prevalence observed among those aged 15 to 19 years (Figure 2).

- While the prevalence increased slightly for children and youth aged 5 to 19 years over the 14-year surveillance period, it remained stable for those aged 1 to 4 years (Figure 2). The highest relative increase in prevalence was observed among those aged 5 to 9 years (30.9%), followed by those aged 10 to 14 years (27.5%). In absolute terms, however, these increases were small—less than one percent.

Over two-thirds of those aged 15 to 19 years who used health services for a mental illness annually,Reference 20 consulted for mood and anxiety disorders, while less than one-third of those aged 1 to 14 years, used those services for mood and anxiety disorders. The lower prevalence among those aged 1 to 14 years is likely due to the fact that non-psychotic mental disorders, including disturbance of conduct and attention deficit disorders, are often first diagnosed in children and young adolescents.Reference 23 While studies have shown that mood and anxiety disorders are common among children and adolescents,Reference 23,Reference 24 and frequently co-occur with conduct and hyperactivity disorders,Reference 24 it is possible that disturbance of conduct and attention deficit disorders were preferentially coded among those aged 1 to 14 years. The higher prevalence of the use of health services for mood and anxiety disorders observed among those aged 15 to 19 years is in keeping with the rise of depression and anxiety during adolescence, especially among females mid and post puberty, due to biological/hormonal processes.Reference 25,Reference 26,Reference 27

Figure 2. Age-specific annual prevalence (%) of the use of health services for mood and anxiety disorders among people aged 1 to 19 years, Canada,Figure 2 footnote * 1996/97 to 2009/10

Figure 2 - Text Equivalent

| Age group (years) |

Fiscal year | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996/97 | 1997/98 | 1998/99 | 1999/00 | 2000/01 | 2001/02 | 2002/03 | 2003/04 | 2004/05 | 2005/06 | 2006/07 | 2007/08 | 2008/09 | 2009/10 | |

| 1 to 4 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| 5 to 9 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| 10 to 14 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.9 |

| 15 to 19 | 6.1 | 6.3 | 6.1 | 6.5 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 6.7 |

3.1.3 Population aged 20 years and older

- In 2009/10, approximately 3.2 million (or 11.9%) Canadian adults used health services for mood and anxiety disorders (figure results not shown).

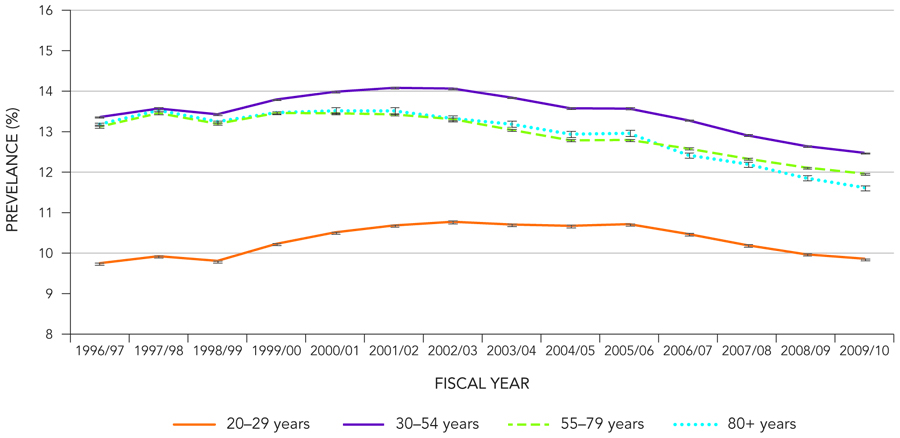

- Over the 14-year surveillance period, the highest age-standardized prevalence was observed among Canadians aged 30 to 54 years, followed closely by those aged 55 years and older (Figure 3).

- The age-standardized prevalence declined slightly in all age groups over the surveillance period, except among younger adults aged 20 to 29 years (Figure 3). These relative decreases ranged from 6.6% to 11.0% among Canadians aged 30 to 54 years and aged 80 years and older, respectively. In absolute terms however, these relative decreases were less than 1.6%.

Figure 3. Age-standardizedFigure 1 footnote † annual prevalence (%) of the use of health services for mood and anxiety disorders among people aged 20 years and older, Canada,Figure 3 footnote * 1996/97 to 2009/10

Figure 3 - Text Equivalent

| Age group (years) |

Fiscal year | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996/97 | 1997/98 | 1998/99 | 1999/00 | 2000/01 | 2001/02 | 2002/03 | 2003/04 | 2004/05 | 2005/06 | 2006/07 | 2007/08 | 2008/09 | 2009/10 | |

| 20 to 29 | 9.8 | 9.9 | 9.8 | 10.2 | 10.5 | 10.7 | 10.8 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 10.5 | 10.2 | 10.0 | 9.9 |

| 30 to 54 | 13.4 | 13.6 | 13.4 | 13.8 | 14.0 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 13.8 | 13.6 | 13.6 | 13.3 | 12.9 | 12.6 | 12.5 |

| 55 to 79 | 13.1 | 13.5 | 13.2 | 13.5 | 13.5 | 13.4 | 13.3 | 13.0 | 12.8 | 12.8 | 12.6 | 12.3 | 12.1 | 12.0 |

| 80+ | 13.2 | 13.5 | 13.2 | 13.5 | 13.5 | 13.5 | 13.3 | 13.2 | 12.9 | 13.0 | 12.4 | 12.2 | 11.9 | 11.6 |

The higher prevalence observed among middle aged and older adults may relate in part to the specific or unique challenges that these subpopulations often face. For example, an association between work related stress and depressive and anxiety disorders has been shown among individuals of working age,Reference 28,Reference 29 with an imbalance between work and personal/family life potentially being a stronger risk factor than other work stress dimensions such as levels of psychological demand and control, job insecurity, social support from supervisor/co-workers.Reference 29 Furthermore, among the risk factors associated with depressive and/or anxiety disorders among the elderly include cognitive impairment, chronic health conditions, functional disability, bereavement, loneliness, and qualitative aspects of social network.Reference 30,Reference 31,Reference 32

3.1.4 Age and sex distribution in population aged one year and older

- In 2009/10, the age and sex distribution for the prevalence of the use of health services for mood and anxiety disorders were similar to those for mental illness overall,Reference 20 with the highest prevalence among middle-aged adults and seniors (Figure 4).

- Females had a higher prevalence than males in all age groups 15 years and older, with the largest relative difference in prevalence found among those aged 30 to 34 years (females vs. males rate ratio: 1.9). In contrast, males aged 5 to 9 years demonstrated a higher prevalence than females in the same age group (rate ratio: 0.8). Finally, the prevalence was similar among females and males aged 1 to 4 years and 10 to 14 years (rate ratios: 0.9 and 1.1 respectively) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Age-specific annual prevalence (%) and rate ratios of the use of health services for mood and anxiety disorders among people aged one year and older, by sex, Canada,Figure 4 footnote * 2009/10

Figure 4 - Text Equivalent

| Age group (years) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 to 4 | 5 to 9 | 10 to 14 | 15 to 19 | 20 to 24 | 25 to 29 | 30 to 34 | 35 to 39 | 40 to 44 | 45 to 49 | 50 to 54 | 55 to 59 | 60 to 64 | 65 to 69 | 70 to 74 | 75 to 79 | 80 to 84 | 85+ | |

| Females | 0.7 | 1.4 | 3.0 | 8.5 | 11.8 | 13.4 | 15.2 | 15.9 | 16.2 | 16.6 | 16.9 | 16.4 | 15.1 | 14.0 | 13.7 | 13.8 | 13.5 | 11.8 |

| Males | 0.8 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 5.1 | 6.8 | 7.4 | 8.2 | 8.7 | 9.1 | 9.5 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 9.1 | 8.4 | 8.5 | 9.1 | 9.9 | 9.7 |

| Total | 0.8 | 1.6 | 2.9 | 6.7 | 9.3 | 10.4 | 11.7 | 12.3 | 12.6 | 13.0 | 13.3 | 13.1 | 12.1 | 11.3 | 11.2 | 11.7 | 12.0 | 11.1 |

| Rate ratio | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.2 |

The higher prevalence of health service use for mood and anxiety disorders among adolescent and adult females compared to males is likely the result of a combination of several factors. Among these factors is the bias in the detection of health conditions, as adult females have been shown to access health services more frequently than males.Reference 33 Also, depression may be more easily recognized in females when considering differences in the symptoms associated with depression, as females tend to express the more "classical" symptoms, while males are more likely to be irritable, angry and discouraged when depressed.Reference 1 Moreover, hormonal fluctuations related to various aspects of reproductive function are thought to predispose females post puberty and of childbearing age to depression more than males of the same age.Reference 25,Reference 26,Reference 27,Reference 34 Furthermore, cultural and social differences, such as work and family responsibilities may also play a role as adult females report experiencing greater work-family conflict than males.Reference 35

Meanwhile, the higher prevalence of health service use among males aged 5 to 9 years may be explained by the fact that anxiety disorders are more prevalent among boys of this age compared to girls.Reference 36 In addition, studies have shown that mood and anxiety disorders frequently co-occur with conduct and hyperactivity disorders, which are more common among boys compared to girls of the same age.Reference 24

3.2 Pan Canadian perspective

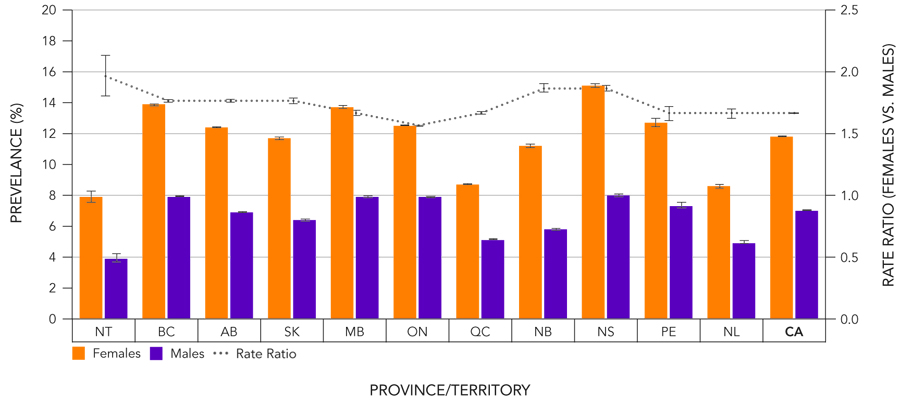

- In 2009/10, the age-standardized prevalence of the use of health services for mood and anxiety disorders was highest in Nova Scotia (11.6%) and lowest in the Northwest Territories (5.8%), (Figure 5).

- Regardless of the geographical location, the age-standardized prevalence was higher for females than males, with rate ratios ranging from 1.6 (in Ontario) to 2.0 (in the Northwest Territories) (Figure 5).

- Several provincial and territorial variations were observed over the 14-year surveillance period. For instance, a significant annual percent increase was found in Saskatchewan (1.7%), Manitoba (1.9%), New Brunswick (1.4%), Nova Scotia (0.6%), Prince Edward Island (1.4%) and Newfoundland and Labrador (0.7%). Of these provinces, the largest relative increase was observed in New Brunswick (41.2%) followed by Manitoba (37.2%). In contrast, a significant annual percent decrease was observed in Ontario (1.3%) with a relative decrease of 16.9%. For all other jurisdictions, the prevalence estimates were relatively stable, among which were Canada's largest provinces by population i.e., British Columbia, Alberta and Quebec (Figure 6).

- The observed provincial and territorial variations contributed to the relatively stable age-standardized prevalence of the use of health services for mood and anxiety disorders overall (Figure 1 and Figure 6).

Figure 5. Age-standardizedFigure 5 footnote † annual prevalence (%) and rate ratios of the use of health services for mood and anxiety disorders among people aged one year and older, by province/ territory and sex, Canada,Figure 5 footnote * 2009/10

Figure 5 - Text Equivalent

| Province/Territory | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northwest Territories | British Columbia | Alberta | Saskatchewan | Manitoba | Ontario | Quebec | New Brunswick | Nova Scotia | Prince Edward Island | Newfoundland and Labrador | Canada | |

| Females | 7.9 | 13.9 | 12.4 | 11.7 | 13.7 | 12.5 | 8.7 | 11.2 | 15.1 | 12.7 | 8.6 | 11.8 |

| Males | 3.9 | 7.9 | 6.9 | 6.4 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 5.1 | 5.8 | 8.0 | 7.3 | 4.9 | 7.0 |

| Total | 5.8 | 10.9 | 9.6 | 9.0 | 10.8 | 10.2 | 6.9 | 8.5 | 11.6 | 10.1 | 6.8 | 9.4 |

| Rate ratio | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

Figure 6. Age-standardizedFootnote † annual prevalence (%) of the use of health services for mood and anxiety disorders among people aged one year and older, by province/territory and Canada,Figure 6 footnote * 1996/97 to 2009/10

Figure 6 - Text Equivalent

| Province/Territory | Fiscal year | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996/97 | 1997/98 | 1998/99 | 1999/00 | 2000/01 | 2001/02 | 2002/03 | 2003/04 | 2004/05 | 2005/06 | 2006/07 | 2007/08 | 2008/09 | 2009/10 | |

| Northwest Territories | 5.9 | 5.9 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 7.2 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 6.7 | 6.5 | 5.8 |

| British Columbia | 10.5 | 10.8 | 10.8 | 11.3 | 11.4 | 11.5 | 11.6 | 11.4 | 11.2 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 10.9 | 10.9 |

| Alberta | 9.6 | 9.8 | 10.2 | 10.8 | 11.2 | 11.5 | 11.5 | 11.1 | 11.0 | 10.9 | 10.5 | 10.3 | 9.9 | 9.6 |

| Saskatchewan | 7.4 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 8.1 | 8.6 | 9.1 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 9.1 | 9.0 | 9.0 |

| Manitoba | 7.9 | 8.4 | 8.8 | 9.4 | 9.7 | 10.0 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 10.7 | 10.5 | 10.3 | 10.3 | 10.8 |

| Ontario | 12.3 | 12.4 | 11.9 | 12.0 | 12.1 | 12.0 | 11.8 | 11.7 | 11.5 | 11.5 | 11.1 | 10.7 | 10.4 | 10.2 |

| Quebec | 7.0 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 7.6 | 7.4 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 6.9 |

| New Brunswick | 6.0 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.7 | 8.0 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 8.7 | 8.3 | 8.4 | 8.2 | 8.1 | 8.2 | 8.5 |

| Nova Scotia | 11.0 | 11.3 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 11.0 | 11.3 | 11.6 | 11.8 | 11.8 | 12.2 | 12.1 | 12.0 | 11.7 | 11.6 |

| Prince Edward Island | 8.2 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 8.7 | 9.0 | 9.3 | 9.6 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 9.6 | 9.2 | 9.3 | 10.0 | 10.1 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 6.4 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 5.7 | 6.2 | 5.9 | 6.4 | 6.5 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 6.5 | 6.8 |

| Canada | 9.9 | 10.1 | 10.0 | 10.3 | 10.4 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 10.3 | 10.2 | 10.2 | 10.0 | 9.7 | 9.5 | 9.4 |

The jurisdictional variations observed may relate to differences in the distribution of factors known to affect mental health such as financial situation, employment status, educational opportunities, social support and community engagement.Reference 1 However, differences in detection and treatment practices, as well as differences in data coding, remuneration models and shadow billing practices likely also play a role.

3.3 Comorbid chronic diseases and conditions in the CCDSS

One of the advantages of the CCDSS methodology is that multiple chronic diseases and conditions can be identified in a comparable way. Cases are identified from the same source population and are linkable via a unique identifier (at the provincial or territorial level only). Therefore, the CCDSS offers the opportunity to calculate the prevalence of comorbid chronic diseases and conditions among people using health services for mood and anxiety disorders. It is important to note that these data can only be used to describe the cross-sectional association between multiple diseases or conditions and cannot be used to describe the direction of this association (i.e. causation). In the future, it may be possible to establish temporality for the diagnosis of chronic diseases and conditions using CCDSS data. This information could provide insights regarding the extent to which mood and anxiety disorders are a risk factor for, or a complication of, other chronic diseases and conditions.

As a part of a pan-Canadian pilot conducted in 2012, the CCDSS captured information on five chronic diseases and conditions that may co-exist with mood and anxiety disorders and all mental disorders combined. These included diabetes, hypertension, asthma, ischemic heart disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The results of this pilot work were used to calculate the prevalence of these comorbid chronic diseases or conditions among people who used health services for mood and anxiety disorders compared with those who did not. For a summary of the case definitions used for these comorbid diseases and conditions, refer to Appendix D.

One limitation of this pilot was that the prevalence of the use of health services for mood and anxiety disorders was calculated on a yearly basis (i.e. annual prevalence), while diabetes, hypertension, asthma, ischemic heart disease and COPD cases, once identified, were prevalent for life. In addition, some jurisdictions use only one diagnostic field in physician billing; therefore, if an individual presents with more than one disease or condition during a single health care encounter, all health issues will not be captured. This is increasingly problematic for older individuals, since they are more likely to have multiple comorbidities. Furthermore, certain diagnoses such as diabetes may be preferentially coded compared with others, resulting in under-reporting of mood and anxiety disorders.

Overall, results from this pan-Canadian pilot demonstrated that comorbid chronic diseases and conditions are more prevalent among people having used health services for mood and anxiety disorders compared to those who did not (Figure 7).

- From 2000/01 to 2009/10, asthma was the most prevalent condition among people having used health services for mood and anxiety disorders compared to those who did not, followed by COPD (rate ratios ranged from 1.5 to 1.6). To a lesser extent, ischemic heart disease, hypertension and diabetes were also more prevalent among people having used health services for mood and anxiety disorders compared to those who did not (rate ratios ranged from 1.1 to 1.3) (Figure 7).

- The observed differences in the age-standardized rate ratios were relatively stable over the 14-year surveillance period except for asthma and ischemic heart disease, where the differences decreased slightly over time (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Age-standardizedFootnote † rate ratio for the prevalence of chronic diseases or conditions among people who used vs. did not use health services for mood and anxiety disorders,Footnote ‡ Canada,Footnote * 2000/01 to 2009/10

Figure 7 - Text Equivalent

| Chronic disease (study population) |

Fiscal year | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000/01 | 2001/02 | 2002/03 | 2003/04 | 2004/05 | 2005/06 | 2006/07 | 2007/08 | 2008/09 | 2009/10 | |

| Asthma (1+ years) |

1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| COPD (35+ years) |

1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Ischemic heart disease (20+ years) |

1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Diabetes (1+ years) |

1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Hypertension (20+ years) |

1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

These findings are supported by the many known bidirectional associations between mood and anxiety disorders and other chronic diseases and conditions. For instance, depressive and anxiety disorders have been shown to be associated with the onset of asthma, chronic bronchitis or emphysema, heart disease, hypertension, arthritis, chronic back pain and migraines later in life.Reference 9,Reference 37,Reference 38,Reference 39 Mental disorders are believed to cause poor physical health later in life by functioning as a type of intrinsic psychosocial stressor through direct biological mechanisms. More specifically, these disorders have been hypothesized to contribute to a chronic imbalance in the hormonal and neurotransmitter mediators of the stress responseReference 40 which have been linked with a range of adverse metabolic (such as diabetes), cardiovascular, immune and cognitive effects.Reference 40,Reference 41,Reference 42 Furthermore, mental disorders may lead to unhealthy behaviours that increase the risk of developing or exacerbating other chronic diseases and conditions, as a way of coping with stress, or regulating depressed mood or anxiety.Reference 9,Reference 10,Reference 43 For example, prospective cohort studies have shown that depression predicts smoking initiation,Reference 11 increases in smoking behaviour,Reference 12 poorer quitting rates,Reference 44 and decreases in physical activity.Reference 45 Since smoking is a major risk factor in the development of various physical chronic conditions such as chronic respiratory disease, and since reduced exercise capacity is a predictor of poor prognosis for those living with these conditions, these associations have obvious implications.Reference 13

Conversely, depressive and anxiety disorders may result from the burden of living with a physical chronic disease or condition.Reference 1 In a longitudinal study, Patten et al. (2001) found that having a long-term medical condition approximately doubled the risk of developing major depression in the Canadian population.Reference 14 The development of these mental disorders may be due to a number of causes including aversive symptoms, functional impairments, or physiologic changes associated with the condition or disease as well as, side effects from medication used to treat them.Reference 15

4. Conclusion

Mood and anxiety disorders are a major public health issue, with approximately 1 in 10 Canadians using health services for these disorders annually (age-standardized prevalence ranged from 9.4% to 10.5% over the 14 year surveillance period). The highest prevalence was observed among middle aged females, while the largest relative increases were found among children and youth; although in absolute terms, these increases were less than one percent. Tracking the use of health services for mood and anxiety disorders over time will help us evaluate the impact of public health interventions and monitor subpopulations at greatest risk, including children and youth, and middle aged females.

While the coverage for the CCDSS is near-universal, the findings within this report should be interpreted with some caution in light of several exclusions. For instance, the CCDSS estimates do not include Canadians covered under federal health programs as well as those who: sought mental health services from salaried physicians who do not shadow bill; exclusively sought privately funded care; received mental health services in hospitals that do not submit discharge abstract data to the Discharge Abstract Database (or in the case of Quebec, the MED-ÉCHO); sought care but did not receive a relevant mood or anxiety diagnostic code; or have not sought care at all. In light of the above, results within this report likely underestimate the use of health services for mood and anxiety disorders in Canada.

This report is the first publication to present administrative data from the CCDSS on the use of health services for mood and anxiety disorders in Canada. Knowledge of the current status and trends will be useful for increasing the collective understanding of mood and anxiety disorders and related health care utilization in the Canadian population. The information within will help key stakeholders within all levels of government, non-governmental organizations, academic and industry sectors in their efforts to reduce the burden of mood and anxiety disorders in Canada.

Future plans

Future work involving the CCDSS related to mood and anxiety disorders includes but is not limited to: the ongoing collection and reporting of data on mood and anxiety disorders; developing an approach to study the chronicity of mood and anxiety disorders; and exploring other comorbid diseases and conditions.

Glossary

- Age-specific proportion or rate

-

Proportion or rate calculated for a specific age group.

- Age-standardized proportion or rate

-

Proportion or rate adjusted for the differences in population age structure between the study population and a reference population. Age-standardized proportions or rates are commonly used in trend analysis or when comparing these proportions or rates for different geographic areas or subpopulations.

- Annual percent change

-

The average annual percent change over several years is used to measure the change in proportions or rates over time. The calculation involves fitting a straight line to the natural logarithm of the data when it is displayed by calendar or fiscal year. The slope of the line, expressed in percentages, represents the annual percent change.

- Agoraphobia

-

An anxiety disorder that is characterized by experiencing anxiety in places or situations where there is a perception that escape may be difficult or help may not be available.Reference 1

- Annual prevalence of the use of health services for mood and anxiety disorders (%)

-

The proportion of individuals who use health services for mood and anxiety disorders during a one-fiscal-year period. This is represented by the number of individuals who have used health services for a mood or/and anxiety disorder, divided by the total population i.e. all individuals registered in provincial and territorial health insurance plans (approximately 97% of the Canadian population). The CCDSS identified individuals as having used health services for mood and anxiety disorders if they met the following criteria: at least one physician claim listing a mood and/or anxiety disorder diagnostic code in the first field, or one hospital discharge abstract listing a mood and/or anxiety disorder diagnostic code in the most responsible diagnosis field using the following ICD codes: ICD-9 or ICD-9-CM (296, 300, and 311), or their ICD-10-CA equivalents (F30 to F48, and F68) during a one-fiscal-year period.

- Anxiety Disorders

-

Anxiety disorders are characterized by excessive and persistent feelings of apprehension, worry and even fear.

- Bipolar disorder

-

A mood disorder that

"is characterized by at least one manic or mixed episode (mania and depression) with or without a history of major depression. Bipolar 1 disorder includes any manic episode, with or without depressive episodes. Bipolar 2 is characterized by major depressive episodes and less severe forms of mania (hypomanic episodes)."

Reference 1 - Chronicity

-

The degree of persistence of a chronic disease or condition, i.e. a disease or condition that is considered permanent once diagnosed or, is intermittent once diagnosed.

- Comorbidity

-

Coexisting chronic diseases or conditions which are additional to a specific disease or condition under study.

- Confidence Interval

-

A statistical measurement of the reliability of an estimate. The size of the confidence interval relates to the precision of the estimate with narrow confidence intervals indicating greater reliability than those that are wide. The 95% confidence interval shows an estimated range of values which is likely to include the true prevalence 19 times out of 20.

- Depression

-

A mood disorder that may involve a range of the following symptoms: feelings of worthlessness, sadness and emptiness that impair functioning; a loss of interest in usual activities; changes in appetite; disturbed sleep; and decreased energy. Children with depression may show signs of irritability, anxiety, or behavioural problems that are similar to symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder or attention deficit disorder. Seniors may experience depression through symptoms of anxiety, agitation, and physical and memory disorders.Reference 1

- Discharge Abstract Database (DAD)

-

Maintained by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), the DAD captures demographic, clinical and administrative data on hospital discharges (including deaths, sign-outs and transfers). Some provinces and territories also use the DAD to capture day surgery. Facilities in all provinces and territories except Quebec are required to submit to this database.

- Dysthymic disorder

-

A mood disorder characterized by

"a chronically depressed mood that occurs for most of the day, for more days than not, over a period of at least two years without long, symptom-free periods."

"Adults with the disorder complain of feeling sad or depressed, while children may feel irritable."

The minimum duration of symptoms that is required for diagnosis in children is one year.Reference 1 - Feasibility study

-

A study conducted to determine if data are appropriate to use for surveillance purposes.

- Fee-for-service

-

Payment of claims based on submission of individual medical services.Reference 46

- Generalized anxiety disorder

-

An anxiety disorder that involves excessive anxiety or worry that is difficult to control and is often experienced together with fatigue and poor concentration. The clinical diagnosis involves symptoms that occur for more days than not over a period of at least six months.Reference 1

- International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code

-

An international standard diagnostic classification for diseases and other health conditions for epidemiological, clinical, and health management purposes. For example, it is used to monitor the incidence and prevalence of diseases and other health problems, providing a picture of the general health situation of countries and populations.Reference 47

- Incidence

-

The number of new cases of a disease or condition occurring in a given time period in a population at risk, expressed as a proportion or rate.

- Linear trend analysis

-

A statistical approach used to detect and estimate linear trends in time series data. Prevalence estimates are assumed to be Poisson distributed therefore a Poisson or log-linear regression is used to find a linear relationship between the prevalence estimate and a calendar or fiscal year. The slope of that line shows whether the estimates are increasing or decreasing over time.

- Major depressive disorder

-

A mood disorder that

"is characterized by one or more major depressive episodes"

, clinically defined by the occurrence of a minimum of"at least two weeks of depressed mood and/or loss of interest in usual activities accompanied by at least four additional symptoms of depression."

Reference 1 - Manic episodes

-

A symptom of mood disorders that involve displays of high energy and risk-taking behaviours, and often predispose an individual to engage in

"out of character"

actions, such as spending money freely, breaking the law, or showing a lack of judgment in sexual behaviour. Manic episodes can last from weeks to months interfering with relationships, social life, education and work.Reference 1 - Maintenance et exploitation des données pour l'étude de la clientèle hospitalière ( MED-ÉCHO)

-

A provincial database which captures demographic, clinical and administrative data for inpatient acute care, day surgery, and some rehab, chronic and psychiatric facilities in Quebec.

- Mental illness

-

Mental illnesses are

"characterized by alterations in thinking, mood or behaviour (or some combination thereof) associated with significant distress and impaired functioning."

Reference 1 They result from complex interplay of biological, genetic, economic, social and psychosocial factors.Reference 7 Mental illnesses can affect individuals of any age; however, they often appear by adolescence or early adulthood.Reference 48 There are many different types of mental illnesses, and they can range from single, short-lived episodes to chronic disorders. - Mood Disorders

-

Mood disorders are characterized by the lowering or elevation of a person's mood.

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder

-

An anxiety disorder that involves obsessions, such as

"persistent thoughts, ideas, impulses, or images that are perceived as intrusive and inappropriate, and that cause marked anxiety or distress."

Compulsions are thoughts or actions that occur as a response used to counteract obsessions.Reference 1 - Panic disorder

-

An anxiety disorder that involves the

"presence of recurrent, unexpected panic attacks"

(a discrete period of intense fear),"followed by at least one month of persistent concern about having additional attacks,"

worry about the attacks, or a"significant change in behaviour related to the attacks."

Reference 1 - Perinatal depression

-

A mood disorder that

"may be experienced by both pregnant women and new mothers."

Reference 1 - Postpartum depression

-

A mood disorder specific to new mothers.Reference 1

- Post-traumatic stress disorder

-

An anxiety disorder that is marked by flashbacks, persistent fear invoking thoughts and memories, and

"anger or irritability in response to a terrifying experience."

Reference 1 - Prevalence

-

The frequency of a disease or condition in a population during a defined period of time, expressed as the proportion of that population that has the disease or condition. Prevalence provides a measure of the burden of the disease or condition in the population.

- Rate ratio

-

The ratio of two related measures, for example, the prevalence of the use of health services for mental illness among females, divided by the prevalence of the use of health services for mental illness among males.

- Relative percent change

-

A measure of relative change expressed as a percentage. It can be used to demonstrate how much a prevalence estimate at the end of a surveillance period increased or decreased relative to the estimate at the beginning of a surveillance period.

- Risk factors for mood and anxiety disorders

-

Aspects of life and/or genetic predisposition that increase the likelihood of developing a mood or anxiety disorder, or the likelihood that an existing mood or anxiety disorder may be worsened.Reference 49

- Shadow billing

-

Shadow billing is an administrative process whereby physicians submit service provision information using provincial or territorial fee codes, even though they are reimbursed by other means of payment. Shadow billing can be used to maintain historical measures of service provision based on fee-for-service claims data.

- Social phobia

-

An anxiety disorder that is defined by extreme fear or avoidance of social or performance situations.Reference 1

- Stigma

-

"Beliefs and attitudes […] that lead to the negative stereotyping of people and to prejudice against them and their families. The individual and collective discrimination arising is often based on ignorance, misunderstanding and misinformation."

Reference 49

Acknowledgements

- Public Health Agency of Canada Production Team (past and present)

-

- Christina Bancej

- Alain Demers

- Joellyn Ellison

- Yong Jun Gao

- Charles Gilbert

- Kelsey Klaver

- Lidia Loukine

- Louise McRae

- Siobhan O'Donnell

- Jay Onysko

- Catherine Pelletier

- Louise Pelletier

- Neel Rancourt

- Cynthia Robitaille

- Glenn Robbins

- Amanda Shane

- Jennette Toews

- Saskia Vanderloo

- Chris Waters

- CCDSS Mental Illness Working Group (past and present)

-

- Cheryl Broeren, British Columbia Ministry of Health

- Leslie Anne Campbell, Dalhousie University

- Wayne Jones, Simon Fraser University

- Steve Kisely, University of Queensland (Australia)

- Alain Lesage, Centre de recherche de l'Institut universitaire en santé mentale de Montréal

- Adrian Levy, Dalhousie University

- Elizabeth Lin, Centre for Addictions and Mental Health

- Peter Nestman, Dalhousie University

- Eric Pelletier, Institut national de santé publique du Québec

- Kim Reimer, British Columbia Ministry of Health

- Mark Smith, University of Manitoba

- Larry Svenson, Alberta Ministry of Health

- Karen Tu, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences

- Helen-Maria Vasiliadis, Université de Sherbrooke

- CCDSS Science Committee (past and present)

-

- Paul Bélanger, Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- Gillian Booth, University of Toronto

- Jill Casey, Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness

- Kayla Collins, Newfoundland and Labrador Centre for Health Information

- Valérie Émond, Institut national de santé publique du Québec

- Jeffrey Johnson, University of Alberta

- John Knight, Newfoundland and Labrador Centre for Health Information

- Anthony Leamon, Government of the Northwest Territories

- Lisa Lix (Co-Chair), University of Manitoba

- Carol McClure, Prince Edward Island Department of Health and Wellness

- Rolf Puchtinger, Saskatchewan Ministry of Health

- Indra Pulcins, Canadian Institute for Health Information

- Drona Rasali, Saskatchewan Ministry of Health

- Kim Reimer (Co-Chair), British Columbia Ministry of Health

- Mark Smith, University of Manitoba

- Larry Svenson, Alberta Ministry of Health

- Karen Tu, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences

- Linda Van Til, Veterans Affairs Canada

- Mental Illness Surveillance Advisory Committee (membership in 2011/2012)

-

- Carol Adair, University of Calgary

- Tim Aubry, University of Ottawa

- Kathryn Bennett, McMaster University

- Karen Cohen, Canadian Psychological Association

- Wayne Jones, Simon Fraser University

- Nawaf Madi, Canadian Institute for Health Information

- Gillian Mulvale, McMaster University

- Mark Smith, University of Manitoba

- Larry Svenson, Alberta Ministry of Health

- Cathy Trainor, Statistics Canada

- Phil Upshall, Mood Disorders Society of Canada

- CCDSS Technical Working Group (membership in 2011/2012)

-

- Fred Ackah, Alberta Ministry of Health

- Patricia Caetano, Manitoba Health

- Jill Casey, Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness

- Connie Cheverie, Prince Edward Island Department of Health and Wellness

- Bryany Denning, Government of Northwest Territories

- Neeru Gupta, New Brunswick Department of Health

- Yuko Henden, Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness

- Ping Li, Institute of Clinical and Evaluative Sciences

- Mary-Ann MacSwain, Prince Edward Island Department of Health and Wellness

- Pat McCrea, British Columbia Ministry of Health

- Jim Nichol, Saskatchewan Ministry of Health

- Rolf Puchtinger, Saskatchewan Ministry of Health

- Robin Read, Diabetes Care Program of Nova Scotia

- Louis Rochette, Institut national de santé publique du Québec

- Mike Ruta, Government of Nunavut

- Khokan Sikdar, Newfoundland and Labrador Centre for Health Information

- Josh Squires, Newfoundland and Labrador Centre for Health Information

- Mike Tribes, Government of Yukon

- Hao Wang, Department of Health New Brunswick

- Kai Wong, Government of Northwest Territories

This study was made possible through collaboration between PHAC and the respective governments of Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Northwest Territories, Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Quebec and Saskatchewan. The opinions, results, and conclusions in this report are those of the authors. No endorsement by the above provinces and territory is intended or should be inferred.

Appendix A

Scope of the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System (CCDSS)

The purpose of the CCDSS is to estimate and report on trends of chronic diseases and conditions in Canada. Based on the model of the former National Diabetes Surveillance System, the CCDSS continues to track diabetes; however, its scope has been/is being expanded to include other chronic diseases and conditions such as mental illness, mood and anxiety disorders, hypertension, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, ischemic heart disease, acute myocardial infarction, stroke, arthritis, osteoporosis, and neurological conditions. The CCDSS provides nearly complete coverage of Canada's population, including people who are often missed by other methods of data collection (e.g. surveys). It provides a more comprehensive picture of chronic diseases and conditions seen in the Canadian health care system than databases which track hospitalized conditions alone. It is guided by the expertise of the CCDSS Science Committee, with representatives from each province and territory.

Appendix B

Mood and anxiety surveillance using administrative data: feasibility and validation studies

A feasibility study was carried out to evaluate the usefulness of administrative data for the surveillance of treated mood and anxiety disorders in Canada by age, sex and year using data from the following four provinces: British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec (Montreal only), and Nova Scotia.Reference 21

Cases were captured via population-based record-linkage using administrative data from physician billing claims, hospital discharge abstract records, and community-based clinics. An individual was identified as a case if he or she had at least one physician visit, or one hospital discharge, with a diagnosis in the first or most-responsible diagnostic field, respectively using the following diagnostic codes:

- Mood disorders: ICD-9 or ICD-9-CM (296.0–296.9 and 311.0), or their ICD-10-CA or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition equivalents; and

- Anxiety disorders: ICD-9 or ICD-9-CM (300.0–300.9), or their ICD-10-CA or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition equivalents.

In British Columbia, an individual can receive the code '50B' for either condition; therefore, this code was also included in the case definition. Mood and anxiety disorders were examined as a combined entity as well as separately. Prevalence estimates were calculated annually.

Results for mood and anxiety disorders combined demonstrated that the annual prevalence of treated mood and anxiety disorders was relatively comparable across the four provinces although slightly lower in Quebec. This may have been due to the fact that the sample included Montreal only where psychologists, who were not captured in these data sources, play a greater role in treatment than in the other participating provinces. In addition, results demonstrated the expected sex and age patterns and were found to be stable over time. Furthermore, results were found to be consistent with other Canadian studies and surveys including the Stirling County Study and the Canadian Community Health Survey.

In contrast, considerable inter-provincial variations were observed when the annual prevalence for treated mood and anxiety disorders were considered separately. Distinguishing between treated mood and anxiety disorders is challenging on account of the overlap in coding and clinical features in addition to the fact that these disorders frequently coexist. As a result, a combined measure was recommended for the national surveillance of treated mood and anxiety disorders.

In a similar feasibility study conducted on mental illnesses,Reference 50 additional testing was carried out to assess the impact of incorporating physician billing codes and hospitalization data beyond the first and most responsible diagnosis fields, respectively. In Ontario and Nova Scotia, it was possible to expand the case definition in hospital morbidity data to search for mental illness codes in up to 16 fields although, doing so, increased the prevalence by only 0.3%. In Alberta and Nova Scotia, it was possible to search for mental illness codes in up to two fields of physician billings however, this resulted in less than a 0.5% increase in prevalence. Therefore, restricting to the use of one diagnostic field only (common denominator across all provinces and territories) was considered to have a small impact on case capture. Furthermore, this study examined the effect of adding data from British Columbia and Nova Scotia community based clinics, which includes health care encounters with all mental health clinicians, not just physicians. Results demonstrated that the prevalence of treated mental illnesses increased by only one percent.

Upon completion of the described feasibility work, the Agency funded a study titled "A case definition validation study for mental health surveillance in Canada" to determine the validity of CCDSS case definitions in their ability to capture prevalence of treated mental illnesses using administrative data in an adult population (validity was not assessed among individuals under 20 years of age).Reference 51 This study, conducted by the Institute of Clinical Evaluative Sciences (Ontario), demonstrated that the CCDSS case criteria for the annual prevalence may not correctly identify all diagnosed cases of mood and anxiety disorders (sensitivity 64.7–71.5%; specificity 92.2–93.4%, positive predictive value 47.0–53.2%, negative predictive value 96.0–96.9%). Results did not differ when a hospitalization code was in the most responsible diagnostic field or any other field.

One of the possible explanations for the low sensitivity includes difficulty in capturing a mood and anxiety disorder case in the presence of a competing diagnosis in physician billings, since many jurisdictions are limited to the use of one (i.e. the first) diagnosis field only.Reference 51 However, based on the feasibility testing described above, the impact of this restriction was considered marginal.Reference 50 The low positive predictive value may be explained in part by limitations with the reference standard (i.e. family physician electronic medical records), since specialist consultation letters, and hospitalization and emergency room records are not completely captured in this data source.Reference 51 Another potential explanation for the low positive predictive value includes physicians assigning a diagnostic code for a mood or anxiety disorder when, in fact, the patient did not meet the diagnostic standard.

Overall, results from this validation study demonstrated that the use of administrative data is limited in its ability to correctly identify individuals with mood and anxiety disorders.Reference 51 Therefore, it was recommended that the use of administrative data be confined to describing an estimate of health care contacts for mood and anxiety disorders.

Appendix C

Population coverage of mood and anxiety disorders in the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System (CCDSS)

While the coverage for the CCDSS is near-universal, exclusions include Canadians covered under federal health programs, such as refugee protection claimants, full-time members of the Canadian Forces, eligible veterans, individuals in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and federal penitentiary inmates. First Nations, Inuit and Métis individuals are included in provincial and territorial health registries, therefore; physician and hospital services are captured for these particular populations.

Furthermore, the CCDSS does not capture all eligible cases including those:

-

who were seen by a salaried physician (including psychiatrists) who does not shadow bill

Under traditional physician payment models in Canada, physicians are reimbursed on a fee-for-service basis. With the evolution of health care delivery models, there has been an increase in the number of alternative payment programs, where payments are salaried, sessional or based on capitation. Under these payment modes, diagnostic codes are not captured by physician billingFootnote vi data unless shadow billing is in place. In 2005/06, alternative payment programs totaled 21.3% of all clinical payments made to physicians in Canada.Reference 46 The proportion of physicians receiving payments from alternative payment programs ranged from 10.3% in Alberta to 96.1% in the Northwest Territories. Given that the majority of psychiatrists in several provinces and territories are remunerated under alternative payment plans, and that the shadow billing proportion of them is not known, an unknown quantity of cases may be missing.

-

who sought care from a community-based clinic or private setting

Many mental health services provided in community clinics and private settings (e.g., services from psychotherapists, psychologists, social workers, or counsellors) are funded through alternate payment arrangements and therefore, not captured in the CCDSS. However, results from a feasibility study that examined the effect of including data from community based databases in British Columbia and Nova Scotia demonstrated that the prevalence of treated mental disorders, including mood and anxiety disorders, increased by only one percent.Reference 50

-

who received mental health services in a hospital that does not submit discharge abstract data to the Discharge Abstract Database (DAD), or in the case of Quebec, the MED-ÉCHO

Some dedicated psychiatric hospitals (which account for approximately 11–16% of mental health discharges)Reference 52 and some hospitals with dedicated mental health beds, do not submit discharge abstract data to the aforementioned databases. Therefore, data from psychiatric hospitalizations are not consistently captured in the CCDSS across jurisdictions. It was previously thought that the potential impact of this may be gleaned by the decrease in prevalence observed in Ontario over the surveillance period. The province stopped submitting psychiatric hospital data to the DAD in 2006 when they began submitting this data to the Ontario Mental Health Reporting System (OMHRS). However, preliminary data from Ontario which includes the OMHRS has demonstrated that this does not explain the decrease observed in this jurisdiction.

-

who sought care but did not receive a relevant mood or anxiety disorder diagnostic code

Since many jurisdictions are limited to the use of one (i.e. the first) diagnostic field only, capturing a mood or anxiety disorder case in the presence of a competing diagnosis may be difficult. For example, certain diagnoses such as diabetes may be preferentially coded compared with others, resulting in underreporting of mood and anxiety disorders. In addition, people for whom their health care provider is reluctant to assign a mood or anxiety disorder diagnostic code due to the associated stigma, or is reluctant to attend to their complaints due to inexperience, known management challenges or time constraints,Reference 53 may receive a non-mental illness diagnostic code and therefore, not be captured.

-

who do not seek care at all

The identification of CCDSS mood and anxiety disorder cases depends on people seeking treatment for their symptoms, or parents seeking treatment for their child's symptoms. Several explanations for the low rates of treatment-seeking among those with these mental disorders have been proposed including: fear of stigma from health professionals and society,Reference 54 thinking the problem will go away on its own,Reference 55 and low mental health literacy.Reference 56,Reference 57

Appendix D

Case definitions for comorbid chronic diseases and conditions identified through the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System (CCDSS)

- Asthma

-

Individuals aged one year and older, with at least one inpatient hospitalization listing a diagnostic code for asthma in any diagnostic field, or at least two physician billing claims listing a diagnostic code for asthma in the first diagnosis field, in a two-year period. Once identified, an individual is considered a prevalent case for life.

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

-

Individuals aged 35 years and older, with at least one inpatient hospitalization listing a diagnostic code for COPD in any diagnostic fields, or at least one physician billing claim listing a diagnostic code for COPD in the first diagnosis field, in a given year. Once identified, an individual is considered a prevalent case for life.

- Diabetes

-

Individuals aged one year and older, with at least one inpatient hospitalization listing a diagnostic code for diabetes in any diagnostic field, or at least two physician billing claims listing a diagnostic code for diabetes in any diagnostic field, in a two-year period (with probable cases of gestational diabetes removed). Once identified, an individual is considered a prevalent case for life.

- Hypertension

-

Individuals aged 20 years and older, with at least one inpatient hospitalization listing a diagnostic code for hypertension in any diagnostic field, or at least two physician billing claims listing a diagnostic code for hypertension in any diagnostic field, in a two-year period (with probable cases of pregnancy-induced hypertension removed). Once identified, an individual is considered a prevalent case for life.

- Ischemic heart disease

-

Individuals aged 20 years and older, with at least one inpatient hospitalization listing a diagnostic or procedural code for ischemic heart disease in any diagnostic field or at least two physician billing claims listing a diagnostic code for ischemic heart disease in any diagnostic field, in a one-year period. Once identified, an individual is considered a prevalent case for life.

References

Footnotes

- Reference 1

-

Government of Canada. The Human Face of Mental Health and Mental Illness in Canada. Ottawa (ON): Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada; 2006. 188 p. Cat. No.: HP5-19/2006E. ISBN: 0-662-43887-6.

- Reference 2

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. Economic Burden of Illness in Canada (EBIC) [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 1986—[cited 2015 August 4]. Available from: http://ebic-femc.phac-aspc.gc.ca/index.php.

- Reference 3

-