Routine Practices and Additional Precautions for Preventing the Transmission of Infection in Healthcare Settings

Part D: Appendices

- Appendix I: PHAC infection prevention and control guideline development process

- Appendix II: Definition of terms used to evaluate evidence

- Appendix III: PHAC criteria for rating evidence on which recommendations are based

- Appendix IV: List of abbreviations and acronyms

- Appendix V: Glossary of terms

- Appendix VI: Epidemiologically significant organisms requiring additional precautions

- Appendix VII: Terminal cleaning

- Appendix VIII: Air changes per hour and time in minutes required for removal efficiencies of 90%, 99% and 99.9% of airborne contaminants

- Appendix IX: Advantages and disadvantages of barrier equipment

- Appendix X: Technique for putting on and taking off personal protective equipment

Appendix I: PHAC infection prevention and control guideline development process

Literature search – inclusions/exclusions

A thorough literature search was performed by the Public Health Agency of Canada covering the period from 1999 onward. Details of the literature search are available upon request.

Formulation of recommendations

This guideline provides evidence-based recommendations that were graded to differentiate from those based on strong evidence to those based on weak evidence. Grading did not relate to the importance of the recommendation, but to the strength of the supporting evidence and, in particular, to the predictive power of the study designs from which that data were obtained. Assignment of a level of evidence and determination of the associated grade for the recommendation were prepared in collaboration with the chair and members of the Guideline Working Group. When a recommendation was not unanimous, the divergence of opinion, along with the rationale was formally recorded for the information audit trail. It is important to note that no real divergence of opinion occurred for this guideline; however, when a difference of opinion did occur, discussions took place and a solution was found and accepted.

Where scientific evidence was lacking, the consensus of experts was used to formulate a recommendation. The grading system is outlined in Appendix II and Appendix III.

External review by stakeholders

Opportunity for feedback on the quality and content of the guideline was offered to external stakeholder groups before its release. The list of stakeholders is as follows:

- Accreditation Canada

- Association des Infirmières en Prévention des Infections du Québec

- Association des Médecins Microbiologiste Infectiologues du Québec en Prévention des Infections du Québec

- Association for Emergency Medical Services

- Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada

- Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing

- Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions

- Canadian College of Health Service Executives

- Canadian Healthcare Association

- Canadian Home Care Association

- Canadian Medical Association

- Canadian Nurses Association

- Canadian Occupational Health Nurses Association Incorporated

- Canadian Patient Safety Institute

- Canadian Public Health Association

- Community and Hospital Infection Control Association (CHICA) – Canada

- Community Health Nurses Association of Canada

- Emergency Medical Services Chiefs of Canada

- Victorian Order of Nurses

Editorial independence

This guideline was funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

All members of the Guideline Working Group have declared no competing interest in relation to the guideline. It was incumbent upon each member to declare any interests or connections with relevant pharmaceutical companies or other organizations if their personal situation changed.

This guideline is part of a series that has been developed over a period of years under the guidance of the 2008 Steering Committee on Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines. The following individuals formed the Steering Committee:

- Dr. Lynn Johnston (Chair) Professor of Medicine QEII Health Science Centre Halifax, Nova Scotia

- Ms. Sandra Boivin, BSC Agente de planification, programmation et recherché. Direction de la Santé publique des Laurentides. St-Jérôme, Québec

- Ms. Nan Cleator, RN. National Practice Consultant. VON Canada, Huntsville, Ontario

- Ms. Brenda Dyck, BSN, CIC. Program Director. Infection Prevention and Control Program. Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, Winnipeg, Manitoba

- Dr. John Embil, Director. Infection Control Unit, Health Sciences Centre. Winnipeg, Manitoba

- Ms. Karin Fluet, RN, BScN, CIC. Director. Regional IPC&C Program. Capital Health Region. Edmonton, Alberta

- Dr. Bonnie Henry, Physician Epidemiologist & Assistant Professor. School of Population & Public Health. UBC. BC Centre for Disease Control. Vancouver, British Columbia

- Mr. Dany Larivée, BSc. Infection Control Coordinator. Montfort Hospital. Ottawa, Ontario

- Ms. Mary LeBlanc, RN, BN, CIC. Infection Prevention and Control Consultant. Tyne Valley, Prince Edward Island

- Dr. Anne Matlow, Director of Infection Control Hospital for Sick Children. Toronto, Ontario

- Dr. Dorothy Moore, Division of Infectious Diseases. Montreal Children's Hospital. Montréal, Québec

- Dr. Donna Moralejo, Associate Professor. Memorial University School of Nursing. St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador

- Ms. Deborah Norton, RN, BEd, MSc. Infection Prevention and Control Consultant. Regina, Saskatchewan

- Ms. Filomena Pietrangelo, BScN. Occupational Health and Safety Manager. McGill University Health Centre. Montréal, Québec

- Ms. JoAnne Seglie, RN, COHN-S. Occupational Health Manager. University of Alberta Campus. Office of Environment Health/Safety. Edmonton, Alberta

- Dr. Pierre St-Antoine, Health Science Centre. Centre hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal, Hôpital Notre-Dame, Microbiologie. Montréal, Québec

- Dr. Geoffrey Taylor, Professor of Medicine. Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Alberta. Edmonton, Alberta

- Dr. Mary Vearncombe, Medical Director. Infection Prevention & Control. Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre. Toronto, Ontario

Appendix II: Definition of terms used to evaluate evidenceFootnote 498

| Criteria | Decision | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Strength of study design (Note: "x > y" means x is a stronger design than y) |

Strong | Meta-analysis > Randomized controlled trial > controlled clinical trial = lab experiment > controlled before-after |

| Moderate | Cohort > case-control > interrupted time series with adequate data collection points > cohort with non-equivalent comparison group | |

| Weak | Uncontrolled before-after > interrupted time series with inadequate data collection points > descriptive (cross-sectional > ecological) | |

| Quality of the study | High | No major threats to validity (bias, chance and confounding have been adequately controlled and ruled out as alternate explanation for the results) |

| Medium | Minor threats to validity that do not seriously interfere with ability to draw a conclusion about the estimate of effect | |

| Low | Major threat(s) to validity that interfere(s) with ability to draw a conclusion about the estimate of effect | |

| Number of studies | Multiple | Four or more studies |

| Few | Three or fewer studies | |

| Consistency of results | Consistent | Studies found similar results |

| Inconsistent | Some variation in results but overall trend related to the effect is clear | |

| Contradictory | Varying results with no clear overall trend related to the effect | |

| Directness of evidence | Direct evidence | Comes from studies that specifically researched the association of interest |

| Extrapolation | Inference drawn from studies that researched a different but related key question or researched the same key question but under artificial conditions (e.g., some lab studies) |

Note: Some outbreak investigations and reports include a group comparison/study within the report, and thus are analytic studies. Such studies should be assigned a "strength of design" rating and appraised using the Analytic Study Critical Appraisal Tool Kit. The majority of outbreak studies do not involve group comparisons, and thus are descriptive studies. Case series, case reports and outbreak reports that do not include a group comparison are not considered studies and therefore are not assigned a "strength of design" rating when appraised. Modelling studies are not considered in this ranking scheme, but appraisers need to look at the quality of the data on which the model is based.

Appendix III: PHAC criteria for rating evidence on which recommendations are basedFootnote 498

| Strength of evidence | Grades | Type of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Strong | AI | Direct evidence from meta-analysis or multiple strong design studies of high quality, with consistency of results |

| AII | Direct evidence from multiple strong design studies of medium quality with consistency of results or At least one strong design study with support from multiple moderate design studies of high quality, with consistency of results or At least one strong design study of medium quality with support from extrapolation from multiple strong design studies of high quality, with consistency of results |

|

| Moderate | BI | Direct evidence from multiple moderate design studies of high quality, with consistency of results or Extrapolation from multiple strong design studies of high quality, with consistency of results |

| BII | Direct evidence from any combination of strong or moderate design studies of high/medium quality, with a clear trend but some inconsistency of results or Extrapolation from multiple strong design studies of medium quality or moderate design studies of high/medium quality, with consistency of results or One strong design study with support from multiple weak design studies of high/medium quality, with consistency of results |

|

| Weak | CI | Direct evidence from multiple weak design studies of high/medium quality, with consistency of results or Extrapolation from any combination of strong/moderate design studies of high/medium quality, with inconsistency of results |

| CII | Studies of low quality, regardless of study design or Contradictory results, regardless of study design or Case series/case reports or Expert opinion |

Appendix IV: List of abbreviations and acronyms

- ABHR(s):

- Alcohol-based hand rub(s)

- ACH:

- Air changes per hour

- AIIR(s):

- Airborne infection isolation room(s)

- AGMP(s):

- Aerosol-generating medical procedure(s)

- AMR:

- Antimicrobial resistance

- ARO(s):

- Antibiotic-resistant organism(s)

- CDC:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CDI:

- Clostridium difficile infection

- CJD:

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

- CNISP:

- Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program

- CoV:

- Coronavirus

- HAI(s):

- Healthcare-associated infection(s)

- HCW(s):

- Healthcare worker(s)

- HHV-6:

- Human herpes virus 6

- HIV:

- Human immunodeficiency virus

- HSV:

- Herpes simplex virus

- ICP(s):

- Infection control practitioner/professional(s)

- ICU(s):

- Intensive care unit(s)

- IPC:

- Infection prevention and control

- LTC:

- Long-term care

- MRSA:

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- OH:

- Occupational Health

- ORA:

- Organizational risk assessment

- PCRA:

- Point-of-care risk assessment

- PPE:

- Personal protective equipment

- RSV:

- Respiratory syncytial virus

- SARS:

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- SUDs:

- Single use device(s)

- VRE:

- Vancomycin-resistant enterococci

Appendix V: Glossary of terms

Acute care – A facility where a variety of inpatient services are provided, which may include surgery and intensive care. For the purpose of this document, acute care includes ambulatory care settings such as hospital emergency departments, and free-standing or facility-associated ambulatory (day) surgery or other invasive day procedures (e.g., endoscopy units, hemodialysis, ambulatory wound clinics).

Additional precautions – Extra measures, when routine practices alone may not interrupt transmission of an infectious agent. They are used in addition to routine practices (not in place of), and are initiated both on condition/clinical presentation (syndrome) and on specific etiology (diagnosis).

Aerosols – Solid or liquid particles suspended in the air, whose motion is governed principally by particle size, which ranges from 10 µm-100 µm Stellman JM, editor. Encyclopaedia of occupational health and safety. 4th ed. Geneva:International Labour Office; 1998 (cited 2011 April 1). Available from: www.ilocis.org/en/contilo.html Footnote 499. (Note: Particles less than 10 µm [i.e., droplet nuclei] can also be found in aerosols; however, their motion is controlled by other physical parameters).

Refer to Aerosol-generating medical procedures

Aerosol-generating medical procedures (AGMPs) – Aerosol-generating medical procedures are medical procedures that can generate aerosols as a result of artificial manipulation of a person's airwayFootnote 148. There are several types of AGMPs associated with a documented increased risk of TB or SARS transmission: Intubation and related procedures (e.g., manual ventilation, open endotracheal suctioning); cardiopulmonary resuscitation; bronchoscopy; sputum induction; nebulized therapy; non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (continuous or bi-level positive airway pressure).

There is debate about whether other medical procedures result in the generation of aerosols through cough induction and lead to transmission of infection. However, there is no published literature that documents the transmission of respiratory infections (including TB, SARS and influenza) by these methods. Examples of these procedures include: high-frequency oscillatory ventilation; tracheostomy care; chest physiotherapy; nasopharyngeal swabs, nasopharyngeal aspirates.

Airborne exposure – Exposure to aerosols capable of being inhaled.

Airborne infection isolation room (AIIR) – Formerly, negative pressure isolation room. An AIIR is a single occupancy patient care room used to isolate persons with a suspected or confirmed airborne infectious disease. Environmental factors are controlled in AIIRs to minimize the transmission of infectious agents that are usually transmitted from person to person by droplet nuclei associated with coughing or aerosolization of contaminated fluids. AIIRs should provide negative pressure in the room (so that no air flows out of the room into adjacent areas) and direct exhaust of air from the room to the outside of the building or recirculation of air through a HEPA filter before returning to circulationFootnote 207.

Airborne transmission – Transmission of microorganisms via inhalation of aerosols that results in an infection in a susceptible hostFootnote 124.

Alcohol – An organic chemical containing one or more hydroxyl groups. Alcohols can be liquids, semisolids or solids at room temperatureFootnote 217.

Alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR) – An alcohol-containing preparation (liquid, gel or foam) designed for application to the hands to remove or kill microorganisms. Such preparations contain one or more types of alcohol (e.g., ethanol, isopropanol or n-propanol), and may contain emollients and other active ingredients. ABHRs with a concentration above 60% and up to 90% are appropriate for clinical care (refer to the PHAC IPC guideline Hand Hygiene Practices in Healthcare Settings)Footnote 217.

Ambulatory care - A location where health services are provided to patients who are not admitted to inpatient hospital units, including but not limited to outpatient diagnostic and treatment facilities (e.g., diagnostic imaging, phlebotomy sites, pulmonary function laboratories), community health centres/clinics, physician's offices and offices of allied health professionals (e.g., physiotherapy).

Antimicrobial-resistant organisms (AROs) – A microorganism that has developed resistance to the action of one or more antimicrobial agents of special clinical or epidemiologic significance. As such, microorganisms that are considered antimicrobial-resistant can vary over time and place. Examples of microorganisms included in this group are MRSA and VRE. Other microorganisms may be added to this list if antibiotic resistance is judged to be significant in a specific healthcare facility or patient population, at the discretion of the IPC program or local, regional or national authorities.

Asepsis – The absence of pathogenic (disease-producing) microorganismsFootnote 500.

Aseptic technique – The purposeful prevention of transfer of microorganisms from the patient's body surface to a normally sterile body site or from one person to another by keeping the microbe count to an irreducible minimum. Also referred to as sterile techniqueFootnote 500, Footnote 501.

Biomedical waste – Waste generated within a healthcare facility that warrants special handling and disposal because it presents a particular risk of disease transmission.

Materials shall be considered biomedical waste if

- they are contaminated with blood or body fluids containing visible blood

and - when compressed, they release liquidFootnote 275.

Cleaning – The physical removal of foreign material (e.g., dust, soil, organic material such as blood, secretions, excretions and microorganisms). Cleaning physically removes rather than kills microorganisms. It is accomplished using water and detergents in conjunction with mechanical actionFootnote 438.

Colonization – Presence of microorganisms in or on a host with growth and multiplication but without tissue invasion or cellular injuryFootnote 216.

Cohort – Physically separating (e.g., in a separate room or ward) two or more patients exposed to, or infected with, the same microorganism from other patients who have not been exposed to, or infected with, that microorganismFootnote 502.

Cohort staffing – The practice of assigning specific personnel to care only for patients known to be exposed to, or infected with, the same microorganism. Such personnel would not participate in the care of patients who have not been exposed to, or infected with, that microorganismFootnote 502.

Complex continuing care – The individual's chronic and complex condition needs continuing medical management, skilled nursing, and a range of interdisciplinary, diagnostic, therapeutic and technological services. The individual requiring complex care will have failure of a major physiological system, which may lead to functional or acute medical problems. Chronicity describes the condition or conditions that are assessed to be long-standing, and recurrent or fluctuating through periods of exacerbation. In some cases, the condition will be progressive in nature. An acute condition may accompany the chronic condition.

Contact exposure – Contact exposure occurs when infectious agents are transferred through physical contact between an infected source and a host or through the passive transfer of the infectious agent to a host via an intermediate object.

Contact transmission (direct or indirect) – Contact transmission occurs when contact exposure leads to an infectious dose of viable microorganisms from an infected/contaminated source, resulting in colonization and/or infection of a susceptible host.

Refer to Direct contact, indirect contact

Cough etiquette – Refer to Respiratory hygiene

Critical items – Instruments and devices that enter sterile tissues, including the vascular system. Reprocessing critical items, such as surgical equipment or intravascular devices, involves meticulous cleaning followed by sterilizationFootnote 246.

Decontamination – The removal of microorganisms to leave an item safe for further handlingFootnote 438.

Designated hand washing sink – A sink used only for handwashing.

Direct contact – Transmission is the transfer of microorganisms via direct physical contact between an infected or colonized individual and a susceptible host (body surface to body surface). Transmission may result in infection.

Disinfectant – Product used on inanimate objects to reduce the quantity of microorganisms to an acceptable level. Hospital-grade disinfectants need a Drug Identification Number (DIN) for sale in Canada.

Disinfection – The inactivation of disease-producing microorganisms with the exception of bacterial sporesFootnote 438. Hospital-grade disinfectants are used on inanimate objects and need a drug identification number (DIN) for sale in Canada.

High-level disinfection is the level of disinfection needed when processing semi-critical items. High-level disinfection processes destroy vegetative bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi and enveloped (lipid) and non-enveloped (non-lipid) viruses, but not necessarily bacterial spores.

Low-level disinfection is the level of disinfection needed when processing non-critical items or some environmental surfaces. Low-level disinfectants kill most vegetative bacteria and some fungi, as well as enveloped (lipid) viruses (e.g., influenza, hepatitis B and C and HIV). Low-level disinfectants do not kill mycobacteria or bacterial spores.

Droplet – Solid or liquid particles suspended in the air, whose motion is governed principally by gravity and whose particle size is greater than 10 µm. Droplets are generated primarily as the result of an infected source coughing, sneezing or talkingFootnote 24.

Droplet exposure – Droplet exposure may occur when droplets that contain an infectious agent are propelled a short distance (i.e., within two metres)Footnote 122, Footnote 123, Footnote 124 through the air and are deposited on the mucous membranes of the eyes, nose or mouth of a host.

Droplet nucleus – A droplet nucleus is the airborne particle resulting from a potentially infectious (microorganism-bearing) droplet from which most of the liquid has evaporated, allowing the particle to remain suspended in the airFootnote 503, Footnote 507. (Note: Droplet nuclei can also be found in aerosols; however, their motion is controlled by physical parameters including gravity and air currents).

Droplet transmission – Transmission that occurs when the droplets that contain microorganisms are propelled a short distance (within two metres) through the air and are deposited on the mucous membranes of another person, leading to infection of the susceptible hostFootnote 24. Droplets can also contaminate surfaces and contribute to contact transmission (Refer to Contact transmission).

Drug identification number – The number located on the label of prescription and over-the-counter drug products that have been evaluated by the Therapeutic Products Directorate and approved for sale in Canada.

Emerging respiratory infections – Acute respiratory infections of significant public health importance, including infections caused by either re-emergence of known respiratory pathogens (e.g., SARS) or emergence of as yet unknown pathogens (e.g., novel influenza viruses).

Eye Protection – Eye protection may include masks with built-in eye protection, safety glasses or face shields.

Exposure – The condition of being in contact with a microorganism or an infectious disease in a manner such that transmission may occurFootnote 219.

Facial protection – Facial protection includes masks and eye protection, or face shields, or masks with visor attachment.

Facilities – Refer to Healthcare facility

Febrile respiratory illness – Febrile respiratory infection is a term used to describe a wide range of droplet and contact spread respiratory infections, which usually present with symptoms of a fever >38 °C and new or worsening cough or shortness of breath. Neonates, the elderly, and those who are immunocompromised may not have fever in association with a respiratory infection.

Fit check – Refer to Seal check

Fit-testing – The use of a qualitative or quantitative method to evaluate the fit of a specific make, model and size of respirator on an individualFootnote 233 (Refer also to Seal check).

Fomites – Inanimate objects in the environment that may become contaminated with microorganisms and serve as vehicles of transmissionFootnote 217.

Hand antisepsis – A process for the removal or killing of transient microorganisms on the handsFootnote 504 using an antiseptic; also referred to as antimicrobial or antiseptic handwash, antiseptic hand-rubbing or hand antisepsis/disinfection/decontamination.

Hand hygiene – A comprehensive term that refers to handwashing or hand antisepsis and to actions taken to maintain healthy hands and fingernailsFootnote 217.

Handwashing – A process for the removal of visible soil/organic material and transient microorganisms from the hands by washing with soap (plain or antiseptic) and waterFootnote 217.

Handwashing sink – Refer to designated handwashing sink.

Hazard – A term to describe a condition that has the potential to cause harm. Work-related hazards faced by HCWs are classified in categories: biologic and infectious, chemical, environmental, mechanical, physical, violence and psychosocialFootnote 283.

Healthcare-associated infection (HAI) – Infections that are transmitted within a healthcare setting (also referred to as nosocomial) during the provision of health care.

Healthcare facilities – Include but are not limited to acute-care hospitals, emergency departments, rehabilitation hospitals, mental health hospitals, and LTC facilities.

Healthcare organizations – The organizational entity that is responsible for establishing and maintaining health care services provided by HCWs and other staff in one or more healthcare settings throughout the healthcare continuum.

Healthcare setting – Any location where health care is provided, including emergency care, prehospital care, hospital, LTC, home care, ambulatory care and facilities and locations in the community where care is provided, (e.g., infirmaries in schools, residential or correctional facilities). (Note: Definitions of settings overlap, as some settings provide a variety of care, such as chronic care or ambulatory care provided in acute care, and complex care provided in LTC).

Refer to Acute care, Ambulatory care, Complex continuing care, Home care, Long-term care, Prehospital care

Healthcare workers (HCWs) – Individuals who provide health care or support services, such as nurses, physicians, dentists, nurse practitioners, paramedics and sometimes emergency first responders, allied health professionals, unregulated healthcare providers, clinical instructors and students, volunteers and housekeeping staff. Healthcare workers have varying degrees of responsibility related to the health care they provide, depending on their level of education and their specific job/responsibilities.

Hierarchy of controls – There are three levels/tiers of IPC and OH controls to prevent illness and injury in the workplace: engineering controls, administrative controls, and PPEFootnote 505, Footnote 506.

Home care – Home care is the delivery of a wide range of health care and support services to patients in a variety of settings for health restoration, health promotion, health maintenance, respite, palliation and to prevent/delay admission to long-term residential care. Home care is delivered where patients reside (e.g., homes, retirement homes, group homes and hospices).

Immunocompromised – This term refers to patients with congenital or acquired immunodeficiency or immunodeficiency due to therapeutic agents or hematologic malignancies.

Indirect contact – Transmission is a passive transfer of microorganisms to a susceptible host via an intermediate object, such as contaminated hands that are not cleaned between episodes of patient care, contaminated instruments that are not cleaned between patients/uses or other contaminated objects in the patient's immediate environment.

Infection – Situation in which microorganisms are able to multiply within the body and cause a response from the host's immune defences. Infection may or may not lead to clinical diseaseFootnote 507.

Infection control professional/practitioner (ICP) – A healthcare professional (e.g., nurse, medical laboratory technologist) with responsibility for functions of the IPC program. This individual, who should have specific IPC training, is referred to as an ICPFootnote 416.

Infectious agent – Terminology used to describe a microorganism or a pathogen capable of causing diseases (infection) in a source or a host. Synonymous with microorganism for the purposes of this document.

Infectious waste – Refer to Biomedical waste

Influenza-like illness – A constellation of symptoms which may be exhibited by individuals prior to the confirmation of influenza.

Long-term care – A facility that includes a variety of activities, types and levels of skilled nursing care for individuals requiring 24-hour surveillance, assistance, rehabilitation, restorative and/or medical care in a group setting that does not fall under the definition of acute care. These units and facilities are called by a variety of terms from province to province and territory to territory, and include but are not limited to extended, transitional, subacute, chronic, continuing, complex, residential, rehabilitation, and convalescence care and nursing homes.

Mask – A barrier to prevent droplets from an infected source from contaminating the skin and mucous membranes of the nose and mouth of the wearer, or to trap droplets expelled by the wearer, depending on the intended use. The mask should be durable enough so that it will function effectively for the duration of the given activity. The term "mask" in this document refers to surgical or procedure masks, not to respirators.

Microorganisms – Refer to Infectious agent

Mode of transmission – Mechanism by which an infectious agent is spread (e.g., by contact, droplets or aerosols).

N95 Respirator – A disposable, (Note: most respirators used for health care purposes are disposable filtering face pieces covering mouth, nose and chin) particulate respirator. Airborne particles are captured from the air on the filter media by interception, inertial impaction, diffusion and electrostatic attraction. The filter is certified to capture at least 95% of particles at a diameter of 0.3 microns; the most penetrating particle size. Particles of smaller and larger sizes are collected with greater efficiency. The "N" indicates a respirator that is not oil-resistant or oil-proof. N95 respirators are certified by the National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety (NIOSH – organization based in the United States) and must be so stamped on each respirator [National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety (NIOSH). NIOSH respirator selection logic 2004. 2004. Report No.: 2005-100]Footnote 508 (Refer also to Respirator).

Natural ventilation – Natural ventilation uses natural forces to introduce and distribute outdoor air into a building. These natural forces can be wind pressure or pressure generated by the density difference between indoor and outdoor airFootnote 148.

Non-critical items – Items that touch only intact skin but not mucous membranes. Reprocessing of non-critical items involves thorough cleaning and/or low-level disinfection.

Nosocomial infection – Refer to Healthcare-associated infection

Occupational health (OH) – For the purposes of this document, this phrase refers to the disciplines of Occupational Health medicine and nursing, Occupational Hygiene and Occupational Health and Safety.

Occupational health and safety – "Occupational Health and Safety" is a legal term that is defined in legislation, regulation and/or workplace (e.g., union) contracts that impact a variety of disciplines concerned with protecting the safety, health and welfare of people engaged in work or employment. The use of the phrase "Occupational Health and Safety" invariably refers back to legislation and or regulation that influences workplace safety practices. The definition, and therefore the content encompassed by "OHS" legislation varies significantly between and within jurisdictions in Canada.

Outbreak – An excess over the expected incidence of disease within a geographic area during a specified time period, synonymous with epidemicFootnote 216.

Organizational risk assessment (ORA) – The activity whereby a healthcare organization identifies:

- hazard

- the likelihood and consequence of exposure to the hazard and

- the likely means of exposure to the hazard

- and the likelihood of exposure in all work areas in a facility/office/practice setting; and then

- evaluates available engineering, administrative and PPE controls needed to minimize the risk of the hazard.

Patient – For the purposes of this document, the term "patient" will include those receiving health care, including patients, clients and residents.

Patient environment – Inanimate objects and surfaces in the proximate environment of the patient that may be a source of or may be contaminated by microorganisms.

Patient zone – Concept related to the "geographical" area containing the patient and his/her immediate surroundingsFootnote 504.

Personal protective equipment (PPE) – One element in the hierarchy of controlsFootnote 505, Footnote 506. Personal protective equipment consists of gowns, gloves, masks, facial protection (i.e., masks and eye protection, face shields or masks with visor attachment) or respirators that can be used by HCWs to provide a barrier that will prevent potential exposure to infectious microorganisms.

Plain soap – Detergent-based cleansers in any form (bar, liquid, leaflet or powder) used for the primary purpose of physical removal of soil and contaminating or transient microorganisms. Such soaps work principally by mechanical action and have weak or no antimicrobial activity. Although some soaps contain low concentrations of antimicrobial ingredients, these are used as preservatives and have minimal effect on reducing colonizing floraFootnote 509.

Point-of-care – The place where three elements occur together: the patient, the healthcare worker and care or treatment involving contact with the patient or his/her surroundings (within the patient zone) Point-of- care products should be accessible without leaving the patient zoneFootnote 504.

Point-of-care risk assessment (PCRA) – A PCRA is an activity whereby HCWs (in any healthcare setting across the continuum of care):

- Evaluate the likelihood of exposure to an infectious agent

- for a specific interaction

- with a specific patient

- in a specific environment (e.g., single room, hallway)

- under available conditions (e.g., no designated handwashing sink)

- Choose the appropriate actions/PPE needed to minimize the risk of exposure for the specific patient, other patients in the environment, the HCW, other staff, visitors, contractors, etc. (Note: Healthcare workers have varying degrees of responsibility related to a PCRA, depending on the level of care they provide, their level of education and their specific job/responsibilities.)

Precautions (including source control measures) – Interventions to reduce the risk of transmission of microorganisms between persons in healthcare settings, including patients, HCWs, other staff, volunteers and contractors etc.

Prehospital care – Acute emergency patient assessment and care delivered in a variety of settings (e.g., street, home, LTC, mental health) at the beginning of the continuum of care. Prehospital care workers include paramedics, fire fighters, police and other emergency first responders.

Respirator – A device that is tested and certified by procedures established by testing and certification agencies recognized by the authority having jurisdiction and is used to protect the user from inhaling a hazardous atmosphereFootnote 233. The most common respirator used in health care is a N95 half-face piece filtering respirator. It is a personal protective device that fits tightly around the nose and mouth of the wearer, and is used to reduce the risk of inhaling hazardous airborne particles and aerosols, including dust particles and infectious agentsFootnote 508 (Refer also to N95 Respirator, Respiratory protection, Fit-testing, Seal check).

Respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette – A combination of measures to be taken by an infected source designed to minimize the transmission of respiratory microorganisms (e.g., influenza).

Respiratory protection – Respiratory protection from airborne infection needs the use of a respirator to prevent inhalation of airborne microorganisms. Respiratory protection may be warranted as a component of airborne precautions or needed for performing AGMPs on certain patients. The need for a respirator or for airborne precautions is determined by a PCRA. Factors to be considered are the specific infectious agent, the known or suspected infection status of the patient involved, the patient care activity to be performed, the immune status of the HCW and the patient's ability to perform respiratory hygiene.

Risk – The probability of an event and its consequences.

Routine practices – A comprehensive set of IPC measures that have been developed for use in the routine care of all patients at all times in all healthcare settings. Routine practices aim to minimize or prevent HAIs in all individuals in the healthcare setting, including patients, HCWs, other staff, visitors and contractors.

Seal check – A procedure the wearer performs each time a respirator is worn and is performed immediately after putting on the respirator to ensure that there is a good facial seal. Seal check has been called "fit check" in other IPC documents (Refer also to Fit-testing).

Semi-critical items – Items that come in contact with non-intact skin or mucous membranes but ordinarily do not penetrate them. Reprocessing semi-critical items involves meticulous cleaning followed by high-level disinfection.

Source – The person, animal, object or substance that may contain an infectious agent/microorganism that can be passed to a susceptible host.

Source control measures – Methods to contain infectious agents from an infectious source, including signage, separate entrances, partitions, triage/early recognition, AIIRs, diagnosis and treatment, respiratory hygiene (including masks, tissues, hand hygiene products and designated handwashing sinks), process controls for AGMPs and spatial separation.

Sterile technique – Refer to Aseptic technique

Sterilization – The destruction of all forms of microbial life, including bacteria, viruses, spores and fungi.

Susceptible host – An individual not possessing sufficient resistance against a particular infectious agent to prevent contracting an infection or disease when exposed to the agent (synonymous with non-immune).

Terminal cleaning – Terminal cleaning refers to the process for cleaning and disinfecting patient accommodation that is undertaken upon discharge of any patient or on discontinuation of contact precautions. The patient room, cubicle, or bedspace, bed, bedside equipment, environmental surfaces, sinks and bathroom should be thoroughly cleaned before another patient is allowed to occupy the space. The bed linens should be removed before cleaning begins.

Transmission – The process whereby an infectious agent passes from a source and causes infection in a susceptible host.

Utility sink – A sink used for non-clinical purposes and not appropriate to use for handwashing.

Virulence – Virulence refers to the ability of the infectious agent to cause severe disease (e.g., the virulence of Ebola is high; of rhinovirus is low).

Zone – Refer to patient zone.

Appendix VI: Epidemiologically significant organisms requiring additional precautions

Note: Refer to recommendations for contact precautions for control measures (Part B, Section IV, subsection i).

1. Clostridium difficile

C. difficile infection (CDI), previously referred to as C. difficile–associated disease, is an important HAI, most often associated with antimicrobial therapy. It is the most frequent cause of infectious diarrhea in adults in healthcare settings in industrialized countries. The severity of CDI ranges from mild diarrhea to toxic megacolonFootnote 510. In hospitals participating in the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program (CNISP), the overall incidence and incidence density rates of healthcare-associated CDI for a six-month period (November 1, 2004 to April 30, 2005) were 4.5 cases per 1,000 patient admissions and 6.4 per 10,000 patient-days. The rates were significantly higher in Quebec than in the rest of Canada (11.1 vs. 3.9 cases per 1,000 admissions and 11.9 vs. 5.7 per 10,000 patient-days)Footnote 511. Subsequently, through multimodal interventions, Quebec rates fell (6.4/10,000 patient-days in 2008/2009)Footnote 512. The 2004/2005 Canada-wide CNISP rates are similar to those found in a previous CNISP study reporting 6.4 vs. 6.6 cases per 10,000 days in 1997Footnote 513. Detailed surveillance performed over a two-month period (March and April 2007) reported rates of 4.8 per 1,000 admissions and 7.2 per 10,000 patient-days, with the highest rates in British Columbia, Ontario and the Atlantic provincesFootnote 514. Increased lengths of hospital stay, costs, morbidity and mortalityFootnote 515, Footnote 516 have been reported among adult patients with CDI. Studies have suggested that both the incidence and severity of CDI have increased since 2000. The elderly are especially vulnerableFootnote 516, Footnote 517, Footnote 518, Footnote 519. More severe disease and worse patient outcomes have been attributed to a hypervirulent strain. In one report, the authors noted that the lack of investment in hospital maintenance and cleaning may have facilitated the transmission of this spore-forming pathogenFootnote 516.

C. difficile infections have generally been considered to occur less frequently in children than in adults. Newborns are not susceptible to C. difficile disease, probably due to a lack of receptors, although colonization is commonFootnote 520, Footnote 521. Langley et al.Footnote 522, in a review of nosocomial diarrhea over a decade of surveillance in a university-affiliated paediatric hospital, reported C. difficile to be a common cause of nosocomial diarrhea. The presence of diapers was identified as a risk factor for nosocomial C. difficile.

C. difficile and VRE share risk factors for transmissionFootnote 523.

Any factor associated with alteration of the normal enteric flora increases the risk of C. difficile colonization after exposure to the organismFootnote 510. Risk factors for C. difficile include exposure to antibioticsFootnote 524, chemotherapy or immunosuppressive agentsFootnote 525, Footnote 526, Footnote 527, gastrointestinal surgery and the use of nasogastric tubes and possibly stool softeners, gastrointestinal stimulants, antiperistaltic drugs and proton pump inhibitors. Antacids and enemas have also been associated with an increased risk of colonizationFootnote 517, Footnote 528, Footnote 529.

The primary reservoirs of C. difficile include colonizedFootnote 530 or infected patients and contaminated surfaces and equipment within hospitals and LTC facilitiesFootnote 82, Footnote 90, Footnote 458, Footnote 517, Footnote 531, Footnote 532. The appropriate use of gloves has been demonstrated to significantly reduce the spread of C. difficile in hospitalsFootnote 338.

To reduce transmission of C. difficile, patients with diarrhea should be placed on contact precautions until the diarrhea is resolved or its cause is determined not to be infectiousFootnote 266, Footnote 269, Footnote 270, Footnote 271.

Concern has been raised regarding methods of hand hygiene and environmental disinfectionFootnote 269, Footnote 270, Footnote 517, as C. difficile spores are resistant to commonly used hand hygiene productsFootnote 217 and most hospital disinfectantsFootnote 517, Footnote 532, Footnote 533. Alcohols are thought to have little or no activity against bacterial sporesFootnote 468, Footnote 534. C. difficile infection is spread by bacterial spores, and concern whether increased rates of CDI are associated with increased use of ABHR have been raisedFootnote 269, Footnote 535. In a study to determine whether there is an association between the increasing use of ABHRs and the increased incidence of CDI, Boyce et alFootnote 535 reported that a ten-fold increase in the use of ABHR over three years in a 500-bed university-affiliated community teaching hospital did not alter the incidence of CDI. Others have reported similar findings over one-Footnote 536 and three-year periodsFootnote 537. In outbreak situations or when there is continued transmission, rooms of CDI patients should be decontaminated and cleaned with chlorine-containing cleaning agents (at least 1,000 ppm) or other sporicidal agentsFootnote 43, Footnote 266, Footnote 267, Footnote 268, Footnote 269, Footnote 270, Footnote 271.

Wearing gloves for the care of a patient with CDI or for contact with the patient environment (including items in the environment) reduces the microbial load of C. difficile on the hands of HCWsFootnote 338. Gloves should be removed prior to leaving the room and hand hygiene performed. Hand hygiene at the point-of-care (either with ABHR or soap and water) is necessary before leaving the room of the patient. If a point-of-care handwashing sink is not available, ABHR should be used and hands subsequently washed at the nearest handwashing sink.

It is difficult to determine the most appropriate measures for prevention and control of CDI, as most data published are from outbreak reports where several interventions were introduced at the same timeFootnote 266, Footnote 269, Footnote 270, Footnote 271. There is strong evidence to support the importance of antimicrobial stewardship in addition to IPC interventions in controlling CDIFootnote 266, Footnote 269, Footnote 270, Footnote 271, Footnote 538, Footnote 539, Footnote 540.

Guidelines for the prevention and control of C. difficile have been publishedFootnote 266, Footnote 269, Footnote 270, Footnote 271, Footnote 540, Footnote 541.

2. Antimicrobial-resistant microorganisms

Antimicrobial-resistant microorganisms are microorganisms that have developed resistance to the action of one or more antimicrobial agents and are of special clinical or epidemiologic significance. As the clinical or epidemiologic significance of an antimicrobial-resistant organism can vary over time, geographic location and healthcare setting, there is variability in which microorganisms are considered AROs. In Canada, currently MRSA is considered an ARO in almost all settings, and VREs are considered AROs in many. Certain resistant Gram-negative bacteria are emerging in Canada (e.g., extended spectrum ß-lactamase producers, carbapenemase producers), but there is variability in which are considered AROs.

Prevention and control of AROs

Siegel et al.Footnote 484 note that optimal control strategies for ARO are not yet known, and evidence-based control measures that can be universally applied in all healthcare settings have not been established. They also note that successful control of ARO transmission in healthcare facilities is a dynamic process that necessitates a systematic approach tailored to the problem and healthcare setting. Selection of interventions for controlling ARO transmission should be based on assessment of the local problem, the prevalence of various AROs and the feasibility of implementing the interventions.

Clinical microbiology support is a necessary element of ARO control. Identification and differentiation of resistant strains warrant the use of appropriate laboratory protocols. In some circumstances, active surveillance cultures requiring testing of at-risk but asymptomatic individuals for the presence of ARO colonization may be necessary to achieve control of spread of AROs within facilities. During outbreaks of AROs, an ability to distinguish quickly between spread of a single clone and spread of multiple clones, through use of molecular laboratory typing techniques, can be a key element in outbreak control.

Transmission of AROs occurs directly via HCW hand contact with infected or colonized patients and indirectly via HCW hand contact with contaminated equipment and/or environments, to other patients or other equipment and/or environments. Judicial selection and use of antibiotics may reduce the development of AROs. Preventing HAIs will reduce the prevalence of AROs Footnote 30, Footnote 31, Footnote 32, Footnote 216, Footnote 427, Footnote 542, Footnote 543.

Recommendations for the prevention and control of AROs can be found in the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Routine Practices and Additional Precautions in All Health Care SettingsFootnote 541.

a. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus has become endemic worldwide in many hospitals. A review of the epidemiology, healthcare resource utilization and cost data for MRSA in Canadian settings reported that the rate of MRSA in Canadian hospitals increased from 0.46 to 5.90 per 1,000 admissions between 1995 and 2004. Patients infected with MRSA may need prolonged hospitalization (average of 26 days of isolation per patient), special control measures and expensive treatments. MRSA transmission in hospitals resulted in further extensive surveillance. Total cost per infected MRSA patient averaged $12,216, with hospitalization being the major cost driver (81%), followed by barrier precautions (13%), antimicrobial therapy (4%) and laboratory investigations (2%). The most recent epidemiological data suggest that direct healthcare costs attributable to MRSA in Canada, including costs for management of MRSA-infected and -colonized patients and MRSA infrastructure, was $82 million in 2004 and could reach $129 million in 2010Footnote 544.

During 2007, 47 sentinel hospitals from nine Canadian provinces participated in the CNISP for new MRSA cases. Results indicated no significant (p = 0.195) change in the rate of MRSA infections associated with healthcare, compared with the previous year, although there was an apparent slight increase, from 164 cases per 100,000 patient-admissions to 181Footnote 545. Compared with 2007 MRSA CNISP results, the 2008 surveillance data from 48 sentinel hospitals showed a 16.1% increase (p < 0.05) in the incidence of MRSA infection and a 19.9% increase (p < 0.05) in the incidence of MRSA colonization. Although the overall incidence for community-associated MRSA remained virtually unchanged (p = 0.46) — 174 per 100,000 patient-admissions in 2007 and 171 in 2008 — there was a marginally significant (p = 0.084) 26.9% increase in its infection rate (personal communication, CNISP 2010).

Risk factors for MRSA acquisition have included previous hospitalization, admission to an ICU, prolonged hospital stay, proximity to another patient with MRSA, older age, invasive procedures, presence of wounds or skin lesions and previous antimicrobial therapyFootnote 546, Footnote 547, Footnote 548.

The inanimate hospital environment of patients with MRSA is frequently contaminated. Contamination can occur without direct patient contact and has been demonstrated after contact only with environmental surfaces in the patient’s roomFootnote 70. This reinforces the need for routine practices, including hand hygiene and cleaning and disinfecting patient care equipment between patients.

Community-associated MRSA is an emerging cause of morbidity and mortality among individuals in the community setting. Community-associated MRSA has accounted for a high proportion of community-acquired skin and soft tissue infections in many American and Canadian cities. These strains differ from nosocomial strains, but can be introduced into the hospital and transmitted there or in other healthcare settingsFootnote 549. Transmission, prevention and control is not different from that of hospital strainsFootnote 549.

b. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci

Enterococcus is part of the endogenous flora of the human gastrointestinal tract. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci are strains of Enterococcus faecium or Enterococcus faecalis that contain the resistance genes vanA or vanB.

Certain patient populations are at increased risk for VRE infection or colonization, including those with severe underlying illness or immunosuppression, such as ICU patients, patients with invasive devices (e.g., urinary or central venous catheters), previous antibiotic use and prolonged length of hospital stayFootnote 550. Since the inherent pathogenicity of Enterococcus species is low, the approach to containing the spread of VRE may vary, depending on presence or absence of patients with risk factors for infection.

In 2006, 50 sentinel hospitals from nine Canadian provinces participated in CNISP surveillance for ‘newly identified’ VRE. There was a significant decrease in the overall incidence of VRE acquisition, to 1.2 per 1,000 patient admissions from the 1.32 reported in 2005. This rate remains higher than the 2004 rate of 0.77 per 1,000 patient admissionsFootnote 551.

The primary reservoirs of VRE include patients colonized or infected with VREFootnote 550 and VRE-contaminated materials, surfaces and equipment. Examples of items that may be contaminated are patient gowns and linens, beds, bedside rails, overbed tables, floors, doorknobs, washbasins, glucose metres, blood pressure cuffs, electronic thermometers, electrocardiogram monitors, electrocardiograph wires, intravenous fluid pumps and commodesFootnote 88, Footnote 95, Footnote 130, Footnote 355, Footnote 397, Footnote 473, Footnote 552, Footnote 553. Environmental contamination of the patient room is more likely to be widespread when patients have diarrheaFootnote 95 or are incontinent.

VRE is most commonly spread via the transiently colonized hands of HCWs who acquire it from contact with colonized or infected patients or after handling contaminated material, surfaces or equipment.

Measures to prevent transmission of VRE include adherence to hand hygiene recommendations and environmental cleaning. Verifying procedures and responsibilities for scheduled cleaning and disinfection of environmental surfaces (including frequently touched surfaces) is very important. A persistent decrease in the acquisition of VRE in a medical ICU was reported after an educational and observational intervention with a targeted group of housekeeping personnelFootnote 554. When patient care equipment cannot be dedicated to the use of one patient, it needs cleaning and disinfection prior to use on another patient.

c. Resistant Gram-negative microorganisms

Certain Gram-negative bacilli, such as E. coli, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter spp., have become increasingly resistant to commonly used antimicrobialsFootnote 555. Gram-negative bacilli-resistant to extended spectrum ß-lactams (penicillins and cephalosporins), fluoroquinolones, carbapenems and aminoglycosides have increased in prevalenceFootnote 484, Footnote 556. Outbreaks have been reported in burn unitsFootnote 107, Footnote 557, Footnote 558, Footnote 559, Footnote 560, ICUsFootnote 407, Footnote 561, surgical patients, soldiers returning from AfghanistanFootnote 26, Footnote 562 and LTC settings. Carbapenemaseaemase producing Klebsiella organisms have emerged as major hospital problems in the US and elsewhereFootnote 563. Other carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacilli, particularly Acinetobacter spp, are emerging outside Canada as important hospital pathogens, and may be seen in Canadian hospitals in the future. Other carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacilli spp., such as Enterobacteriacae carrying the New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase (NDM)-1 carbapenemase (currently associated with South Asia, including hospitalization in India) and Acinetobacter spp., are emerging outside Canada as important hospital pathogens and may be seen in Canadian hospitals in the futureFootnote 564. For further information, refer to Infection Prevention and Control Measures for Healthcare Workers in All Healthcare Settings: Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-negative Bacilli (http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/nois-sinp/guide/ipcm-mpci/ipcm-mpci-eng.php).

3. Viral gastroenteritis (Noroviruses, Calicivirus, Rotavirus)

Noroviruses (previously called Norwalk-like viruses) are a common cause of gastroenteritis. These viruses are part of a family called calicivirusesFootnote 264.

Many strains of noroviruses have been implicated in explosive outbreaks of gastroenteritis in various settings, including hospitalsFootnote 565, Footnote 566, Footnote 567, Footnote 568, LTC facilitiesFootnote 264, Footnote 569, Footnote 570 and rehabilitation centersFootnote 571, Footnote 572. Noroviruses are found in the stool or emesis of infected individuals when they are symptomatic and up to at least 3 or 4 days after recovery. The virus is able to survive relatively high levels of chlorine and varying temperatures, and can survive on hard surfaces for hours or days. Alcohol-based hand rubs are effective against norovirus, but the optimal alcohol concentration needs further evaluationFootnote 573, Footnote 574, Footnote 575, Footnote 576, Footnote 577. One study suggests that norovirus is inactivated by alcohol concentrations ranging from 70% to 90%Footnote 573. Transmission during facility outbreaks has been documented to result from person-to-person contact affecting patients and HCWsFootnote 578, Footnote 579. Environmental contamination may be a factor in outbreaks in healthcare facilitiesFootnote 264, Footnote 572.

The identification of outbreaks is based on clinical and epidemiological factors, as there is a short incubation period with rapid onset of symptoms. In addition, diagnostic testing is technically difficult and not always readily available, except in a reference laboratory. A guideline for the prevention and control of a norovirus outbreak has been publishedFootnote 265.

Rotavirus is the most common cause of nosocomial gastroenteritis in paediatric settingsFootnote 290, Footnote 580, Footnote 581. Rotavirus can be a causative microbial agent of nosocomial infection, not only in children, but also in immunocompromised persons and the elderlyFootnote 479, Footnote 582.

The virus is present in extremely high concentrations in the stool, thus minimal environmental contamination may lead to transmissionFootnote 80, Footnote 81, Footnote 583, Footnote 584.

4. Emerging respiratory infections

Acute respiratory infections of significant public health importance include infections caused by either re-emergence of known respiratory pathogens (e.g., SARS) or emergence of as yet unknown pathogens (e.g., novel influenza strains) (Refer to Emerging Respiratory Infections [http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/eri-ire/index-eng.php]).

In situations of emerging respiratory infections, refer to the PHAC website for specific guidance documents (http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/nois-sinp/guide/pubs-eng.php).

For additional information regarding SARS coronavirus, refer to the PHAC IPC guideline for the Prevention of Healthcare-Associated Pneumonia, 2010Footnote 216 (http://publications.gc.ca/site/archivee-archived.html?url=http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2012/aspc-phac/HP40-54-2010-eng.pdf).

Appendix VII: Terminal cleaning

- Terminal cleaning refers to the process for cleaning and disinfecting patient accommodation, which is undertaken upon discharge of any patient or on discontinuation of contact precautions. The patient room, cubicle, or bedspace, bed, bedside equipment, environmental surfaces, sinks and bathroom should be thoroughly cleaned before another patient is allowed to occupy the space. The bed linens should be removed before cleaning begins.

- In general, no extra cleaning techniques are warranted for rooms that have housed patients for whom other additional precautions were in place. Specific recommendations related to additional precautions are outlined in items 4 and 9, below.

- Terminal cleaning should primarily be directed toward items that have been in direct contact with the patient or in contact with the patient’s excretions, secretions, blood or body fluids.

- Housekeeping personnel should use the same precautions to protect themselves during terminal cleaning that they would use for routine cleaning. Respirators are not needed unless the room was occupied by a patient for whom there were airborne precautions and insufficient time has elapsed to allow clearing of the air of potential airborne microorganisms (Refer to Appendix VIII).

- All disposable items in the patient’s room should be discarded.

- Reusable items in the room should be reprocessed as appropriate to the item. Refer to the most current publication for environmental infection controlFootnote 239.

- Bedside tables, bedrails, commodes, mattress covers and all horizontal surfaces in the room should be cleaned with a detergent/disinfectantFootnote 239.

- Carpets that are visibly soiled with patient’s excretions, blood or body fluids should be cleaned promptlyFootnote 239.

- Routine washing of walls, blinds and window curtains is not indicated. These should be cleaned if visibly soiled.

- Privacy and shower curtains should be changedFootnote 117.

- Disinfectant fogging is not a satisfactory method of decontaminating air and surfaces and should not be used.

- Additional cleaning measures or frequency may be warranted in situations where continued transmission of specific infectious agents is noted (e.g., C. difficile, norovirus and rotavirus). The efficacy of disinfectants being used should be assessed; if indicated, a more effective disinfectant should be selectedFootnote 239, Footnote 264, Footnote 265. Attention should be paid to frequently touched surfaces, such as doorknobs, call bell pulls, faucet handles and wall surfaces that have been frequently touched by the patient. [BII]

- In outbreak situations or when there is continued transmission, rooms of C. difficile infection patients should be decontaminated and cleaned with chlorine-containing cleaning agents (at least 1,000 ppm) or other sporicidal agentsFootnote 43, Footnote 266, Footnote 267, Footnote 268, Footnote 269, Footnote 270, Footnote 271. [BII]

Appendix VIII: Air changes per hour and time in minutes required for removal efficiencies of 90%, 99% and 99.9% of airborne contaminantsFootnote 21

| Minutes required for each removal efficiency | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Air changes per hour | 90% | 99% | 99.9% |

| 1 | 138 | 276 | 414 |

| 2 | 69 | 138 | 207 |

| 3 | 46 | 92 | 138 |

| 4 | 35 | 69 | 104 |

| 5 | 28 | 55 | 83 |

| 6 | 23 | 46 | 69 |

| 7 | 20 | 39 | 59 |

| 8 | 17 | 35 | 52 |

| 9 | 15 | 31 | 46 |

| 10 | 14 | 28 | 41 |

| 11 | 13 | 25 | 38 |

| 12 | 12 | 23 | 35 |

| 13 | 11 | 21 | 32 |

| 14 | 10 | 20 | 30 |

| 15 | 9 | 18 | 28 |

| 16 | 9 | 17 | 26 |

| 17 | 8 | 16 | 24 |

| 18 | 8 | 15 | 23 |

| 19 | 7 | 15 | 22 |

| 20 | 7 | 14 | 21 |

- Appendix VIII - Note i

-

This table is prepared according to the formula t = (in C2/C1)/(Q/V) = 60, which is an adaptation of the formula for the rate of purging airborne contaminants (100-Mutchler 1973) with t1 = 0 and C2/C1 = 1 – (removal efficiency/100). Adapted from CDC Guidelines for preventing the transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in health-care facilities,1994Footnote 585.

Appendix IX: Advantages and disadvantages of barrier equipment

Reproduced with permission from Provincial Infectious Diseases Advisory Committee (PIDAC) Routine Practices and Additional Precautions in All Health Care Settings. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, August 2009.

| Type | Use | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vinyl |

|

|

|

| Latex |

|

|

|

| Nitrile |

|

|

|

| Neoprene |

|

|

|

Adapted from Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Patient Care Policy Manual Section II: Infection Prevention and Control [Policy No: II-D-1200], ‘Gloves’. Revised July, 2007 and London Health Sciences Centre, Occupational Health and Safety Services, ‘Glove Selection and Use’. Revised April 26, 2005.

| Type of Mask | Use | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Face Mask (‘procedure mask or ‘isolation’ mask) |

|

|

|

| Fluid Resistant Mask |

|

|

|

| Surgical Mask |

|

|

|

| NIOSH certified N95 respirator |

|

|

|

Adapted from Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Patient Care Policy Manual Section II: Infection Prevention and Control [Policy No: II-D-1200], ‘Gloves’. Revised July, 2007 and London Health Sciences Centre, Occupational Health and Safety Services, ‘Glove Selection and Use’. Revised April 26, 2005.

| Type of Eyewear | Use | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safety Glasses |

|

|

|

| Goggles |

|

|

|

| Face Shield |

|

|

|

| Visor attached to Mask |

|

|

Adapted from Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Patient Care Policy Manual Section II: Infection Prevention and Control [Policy No: II-D-1200], ‘Gloves’. Revised July, 2007 and London Health Sciences Centre, Occupational Health and Safety Services, ‘Glove Selection and Use’. Revised April 26, 2005.

Appendix X: Technique for putting on and taking off personal protective equipment

Reproduced with permission from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

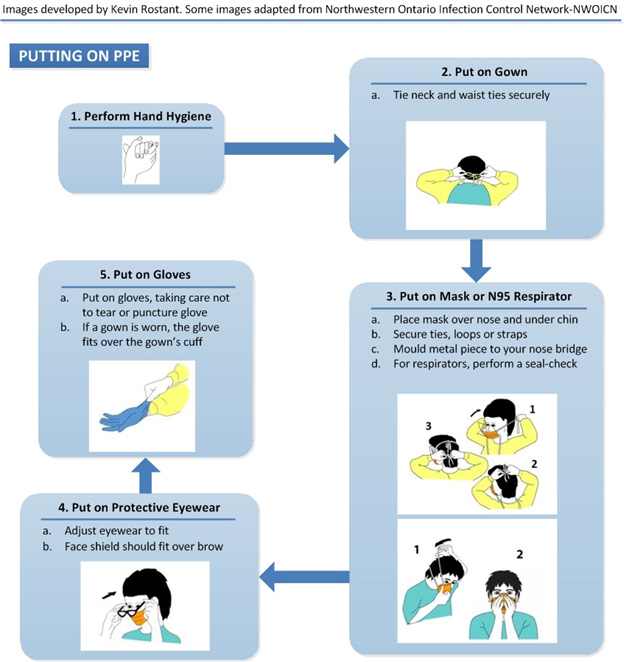

Technique for putting on personal protective equipment (PPE)

Text description

Putting on PPE

- Perform Hand Hygiene either by using alcohol based-hand rub or washing hands with soap and water (if hands soiled)

- Put on Gown

- Tie neck and waist ties securely

- Put on Mask or N95 Respirator

- Place mask over nose and under chin

- Secure ties, loops or straps

- Mould metal piece to your nose bridge

- For respirators, perform a seal-check

- Put on Protective Eyewear

- Adjust eyewear to fit

- Face shield should fit over brow

- Put on Gloves

- Put on gloves, taking care not to tear or puncture glove

- If a gown is worn, the glove fits over the gown’s cuff

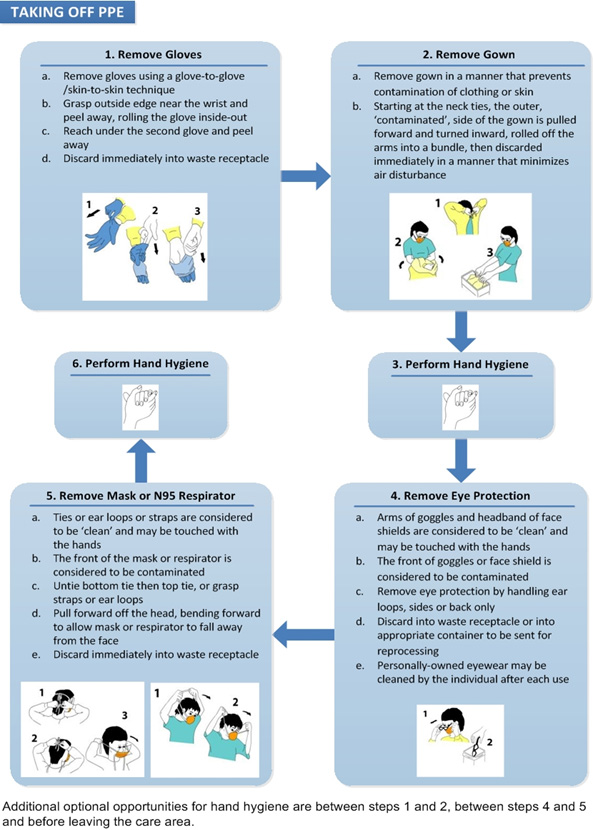

Technique for taking off personal protective equipment (PPE)

Text description

Taking off PPE

- Remove Gloves

- Use glove to glove, skin-to-skin technique.

- Grasp outside edge near the wrist and peel away, rolling the glove inside-out.

- Reach under the second glove and peel away.

- Discard immediately into waste receptacle.

- Remove Gown

- Remove gown in a manner that prevents skin or clothes contamination.

- Starting at the neck ties, the outer, ‘contaminated’, side of the gown is pulled forward and turned inward, rolled off the arms into a bundle, then discarded immediately in a manner that minimizes air disturbance.

- Perform hand hygiene either by using alcohol based-hand rub or washing hands with soap and water (if hands soiled)

- Remove Eye Protection

- Arms of goggles and headband of face shields are considered to be clean and may be touched with the hands.

- The front of goggles or face shield is considered to be contaminated.

- Remove eye protection by handling ear loops, sides or back only.

- Discard into waste receptacle or into appropriate container to be sent for reprocessing.

- Personally-owned eyewear may be cleaned by the individual after each use.

- Remove Mask or N95 Respirator

- Ties or ear loops or straps are considered to be clean and may be touched with the hands.

- The front of the mask or respirator is considered to be contaminated.

- Untie bottom tie then top tie or grasp straps or ear loops.

- Pull forward off the head bending forward to allow mask or respirator to fall away from the face.

- Discard immediately into waste receptacle.

- Perform hand hygiene either by using alcohol based-hand rub or washing hands with soap and water (if hands soiled)