West Nile virus and other mosquito-borne diseases surveillance in Canada: Annual edition 2022

Download in PDF format

(1.12 MB, 16 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Published: 2025-04-03

On this page

- Surveillance highlights

- Introduction

- Methods

- West Nile virus

- California serogroup viruses

- Eastern equine encephalitis virus

- Discussion

- Public health conclusions

- Acknowledgements

- References

Surveillance highlights

West Nile virus

- A total of 47 human cases of West Nile virus (WNV) were reported in 2022. Of these, 45 cases acquired their infection within Canada (44 clinical cases and 1 asymptomatic case).

- Of the 44 WNV clinical cases: 64% were neurological, 25% were non-neurological and 11% were unclassified. Five WNV-associated deaths were reported.

- 8 WNV positive horses, 135 WNV positive dead wild birds, and 0.9% of mosquito pools tested were positive for WNV.

Eastern equine encephalitis virus

- One human case of Eastern equine encephalitis was reported.

California serogroup viruses

- Eighteen human California serogroup virus infections were reported: 3 identified by the National Microbiology Laboratory and 15 separately reported by Québec.

Introduction

West Nile virus (WNV), Eastern equine encephalitis (EEE) virus, and the California serogroup (CSG) viruses, specifically Jamestown Canyon virus and snowshoe hare virus, are known to cause human infection in North America. All four of these mosquito-borne diseases are endemic in various regions of CanadaFootnote 1. It is anticipated that climate change will impact range expansion and local abundance of mosquito species that can transmit these pathogens and cause human diseaseFootnote 1.

Canada’s endemic mosquito-borne diseases have complex transmission cycles with viruses circulating between specific avian or mammalian hosts and competent mosquito vectors. However, a broad range of other mammals, including humans and horses (equines), can also be infected. Recognizing the interdependence of human health, animal health and their shared environment, mosquito-borne disease surveillance requires a One Health approach. This report integrates findings from human and animal health surveillance, conducted in collaboration with multi-disciplinary health partners, with the goal of achieving awareness and optimal human health outcomes.

Methods

West Nile virus

West Nile virus has been a nationally notifiable disease since 2003, and human cases in Canada are reported voluntarily to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) by provincial and territorial health authorities via the National WNV Surveillance System.

During the typical mosquito season (spring, summer, fall) or for at-risk travelers during the winter, blood donations are routinely screened using a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) by Canadian Blood Services and Héma-Québec. Blood donations may be screened using a NAAT specific to WNV or a NAAT that tests for viruses in the same serological family as WNV (Japanese encephalitis serocomplex). Positive blood donors, most commonly asymptomatic, then get reported to provincial/territorial health agencies. Following a positive blood donor screening, supplementary tests may be performed by provincial/ territorial labs or the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML).

Human cases include both clinical and asymptomatic infections. In this report, human cases are classified according to the national surveillance case definition. Of note, Saskatchewan reports WNV neurological syndrome cases only.

Epidemiological analyses included in this report capture human cases where the WNV infection was acquired within Canada. These cases either did not report travel or reported travel only within Canada. For the purposes of this report, cases that were acquired outside of Canada, due to international travel, are excluded from overall epidemiological analyses and only included in the “Travel-related cases” section. If travel was reported but the location was not specified, then the case was also excluded from overall epidemiological analysis since it could not be determined if the infection was acquired within. Canada. Cases that occur outside the typical mosquito season and did not report travel were validated by the province or territory, and reflect the data in provincial and territorial surveillance systems. The earliest available episode date (e.g., symptom onset date, diagnosis date, laboratory sample date or reporting date) for each WNV case was used to assign the case to an epidemiological week using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) epi week calendar. Cases reported outside of the typical mosquito season were excluded from Figures 2 and 3.

In addition to human cases, other indicators of WNV activity in Canada include seropositive animals and positive mosquito pools. In 2022, information on WNV-positive dead wild birds was largely provided by the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative (CWHC); however, some provinces also provide this data directly to the National WNV Surveillance System. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) provides nationwide data on WNV veterinary cases such as horse cases, reported via the Immediately Notifiable Disease Regulations. Mosquito surveillance data are collected and provided by three participating provinces and one territory: Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, and the Northwest Territories.

Other mosquito-borne diseases

Unlike WNV, human CSG and EEE virus infections are not nationally notifiable diseases in Canada, and therefore, the true number of cases and burden of disease is unknown. Some provincial/territorial laboratory partners perform their own testing and there may be differences among their respective case definitions, which can lead to discrepancies in reported numbers. In addition, when requested by other laboratories, the NML tests for EEE virus and CSG viruses in patients who present with symptoms consistent with an arboviral infection. It is possible there is overlap in the cases reported by the NML and those by the provinces. In 2022, CSG virus infection counts were provided by both the NML and the province of Québec.

In addition to human cases of EEE, other indicators of local transmission come from animal and mosquito surveillance. In 2022, mosquito pools were tested for EEE virus in the province of Ontario and the CFIA provided nationwide data on cases of EEE in horses. For CSG viruses, mosquito pools were tested in the Northwest Territories in 2022. As there have only been a few cases of CSG virus infections ever documented in livestock in Canada, CSG virus infections are not notifiable diseases in animals, and therefore not reported to the CFIA.

Limitations of reported data

The findings in this report are subject to several limitations. First, the National WNV Surveillance System is a passive surveillance system; therefore, it is likely that the actual incidence of WNV infections in humans is higher due to underreporting. Only approximately 20% of WNV infections are symptomatic; therefore, it is suspected that many cases go undetected. Although symptoms of WNV can be severe, they are usually mild, and most individuals may not be aware of their infections. Detection and reporting of WNV neurological syndrome are considered more complete than that of WNV non-neurological syndrome as severe cases are more likely to seek medical care. As EEE and CSG virus infections are not nationally notifiable or reportable in many provinces and territories, it is likely these counts are also underreported. Second, data collection (e.g., mosquito pool testing, dead wild bird collection and testing), public health follow-up (e.g., only neurological cases are investigated by public health in Saskatchewan), and case definitions (e.g., CSG viruses) vary within Canada, which may lead to challenges with interpretation. In addition, provincial and territorial disease reporting systems may receive updated case information, which can result in differences between what is presented in this report and provincial and territorial reports.

This report is based on the latest data provided to PHAC for 2022 (data as of: 2023-07-11). Modifications and updates to case information made after this date may not be captured in this report.

West Nile virus

Human case surveillance

A total of 47 human WNV cases were reported to PHAC between January 1 and December 31, 2022. Cases were reported by four provinces in 2022: Ontario (n=29), Québec (n=10), Manitoba (n=7) and New Brunswick (n=1). In total, 96% of cases (n=45) acquired infection within Canada, including cases with no travel history (n=36) and cases with travel within Canada (n=9). One case reported travel outside of Canada and one case reported travel but it could not be determined if the infection was acquired within Canada, as the location was not specified (see section on Travel-Related Cases).

Of the 45 infections acquired within Canada, 44 were clinical and 1 was asymptomatic. The majority of human cases acquired within Canada resided in the southern regions of Ontario, Québec and Manitoba (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Text description

The map shows the distribution of reported human West Nile virus cases (clinical and asymptomatic), positive dead wild birds reported, and positive horse cases reported in Canada for 2022.

| Province/Territory | Human infections (n) | Positive birds (n) | Positive horses (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manitoba | 7 | 8 | 2 |

| Ontario | 28 | 56 | 0 |

| Quebec | 10 | 71 | 1 |

| Saskatchewan | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Total | 45 | 135 | 8 |

| Note: Cases are mapped by their health region of residence. Nine cases were travel-related but acquired in Canada: Ont. (4). Man. (5). |

|||

- Footnote a

-

The health region in which the case resides including those that traveled within Canada.

- Footnote b

-

The latitude and longitude coordinates of the location where the bird was found.

- Footnote c

-

The consolidated census subdivision (CCS) where the horse resides. The horses are mapped to the center of the CCS.

Note: The map excludes cases acquired outside of Canada due to international travel, as well as cases with travel location unspecified. Of note, there was one human case included in the map that reported travel outside their province or territory but within Canada, and eight cases that reported travel within their province or territory of residence.

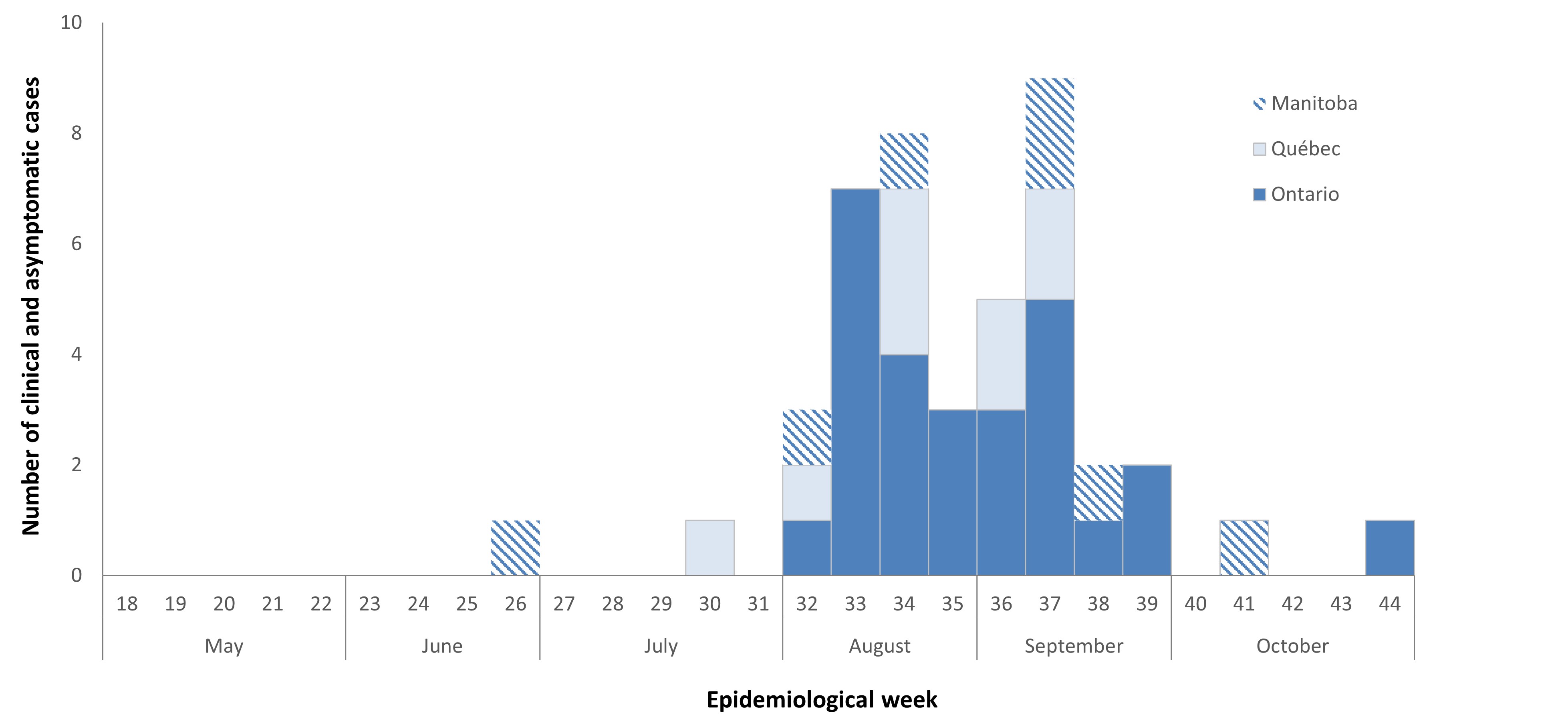

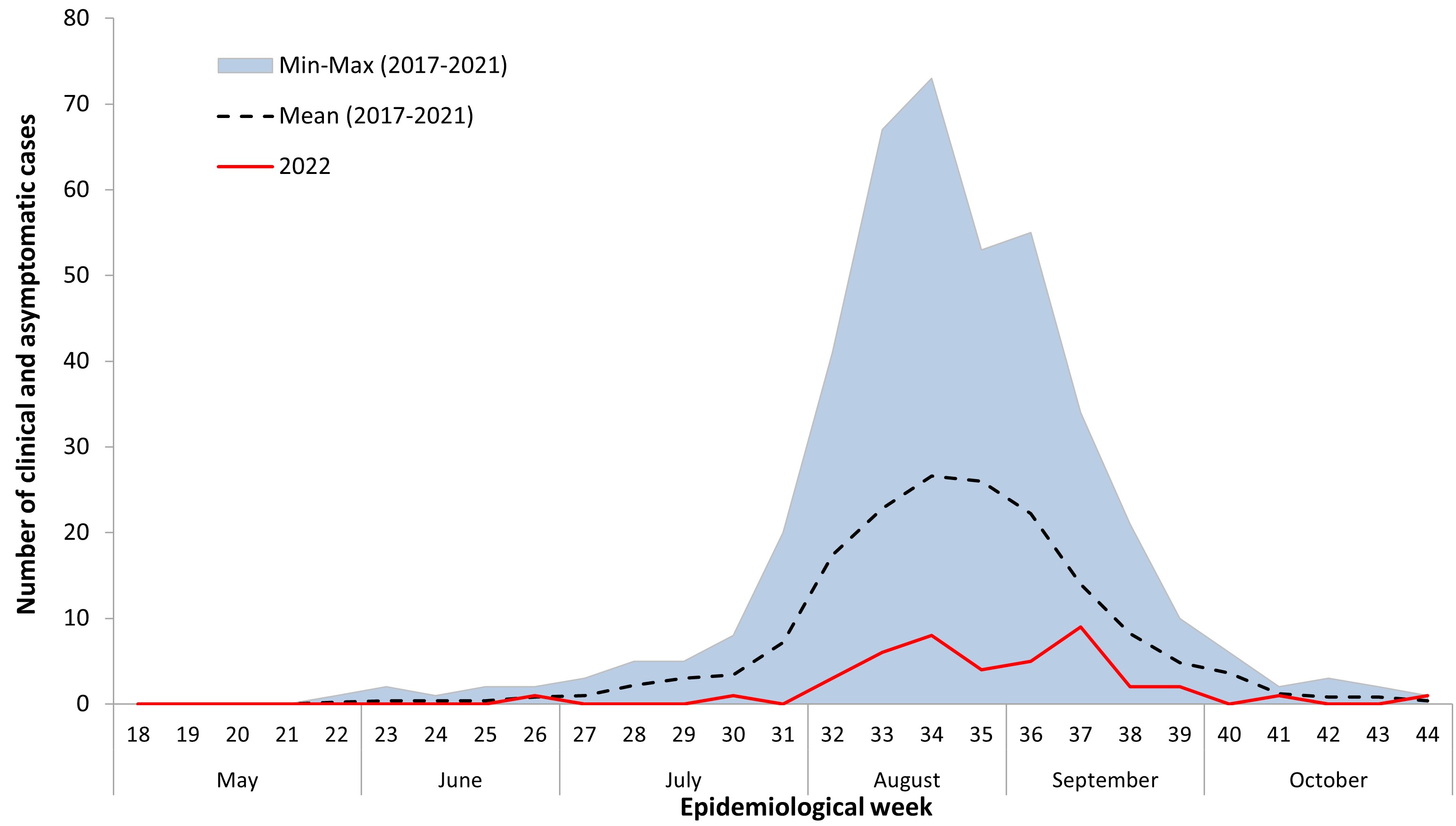

Cases of WNV acquired within Canada occur during the mosquito season, the period when mosquitoes are typically active, with the majority of WNV cases reported in the summer and fall. The earliest onset date for a human WNV case acquired within Canada during the typical mosquito season in 2022 was June 27 (epidemiological week 26). Most (78%) of the reported human WNV cases occurred with an onset date between epidemiological weeks 32 and 37 (early August to mid-September), peaking in week 37 (mid-September) (Figure 2). Typically, the peak week varies from year to year, ranging from week 33 to 37 (early August to mid-September) (Figure 3). The number of human cases observed in 2022 was low compared to the average number of cases reported in the preceding five seasons (2017–2021) (Figure 3).

Figure 2 - Text description

In 2022, between May and end of October, 45 human infections (clinical cases) of West Nile virus were reported to the Public Health Agency of Canada by 3 provinces: Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec.

| Month | Epidemiological weekFootnote d | Province | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manitoba | Ontario | Québec | ||

| May | week 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| week 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| week 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| week 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| week 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| June | week 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| week 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| week 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| week 26 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| July | week 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| week 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| week 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| week 30 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| August | week 31 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| week 32 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| week 33 | 0 | 7 | 0 | |

| week 34 | 1 | 4 | 3 | |

| week 35 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| September | week 36 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| week 37 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| week 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| week 39 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| October | week 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| week 41 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| week 42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| week 43 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| week 44 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 7 | 27 | 9 | |

- Footnote d

-

The earliest available episode date (e.g., symptom onset date, diagnosis date, laboratory sample date or reporting date) is used to assign cases to an epidemiological week.

- Footnote 2

-

There were two WNV cases excluded from the figure as their episode date fell outside the range of the typical mosquito season.

Figure 3 - Text description

This graph shows the number of the West Nile virus human infections (clinical and asymptomatic cases) reported in 2022, which are below the average of the five preceding seasons (2017-2022).

| Month | Epidemiological weekFootnote d | Mean (2017-2021) | Min-Max (2017-2021) | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| May | week 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| week 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| week 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| week 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| week 22 | 0.2 | 1 | 0 | |

| June | week 23 | 0.4 | 2 | 0 |

| week 24 | 0.4 | 1 | 0 | |

| week 25 | 0.4 | 2 | 0 | |

| week 26 | 0.8 | 2 | 1 | |

| July | week 27 | 1.0 | 3 | 0 |

| week 28 | 2.2 | 6 | 0 | |

| week 29 | 3.0 | 6 | 0 | |

| week 30 | 3.4 | 8 | 1 | |

| August | week 31 | 7.2 | 20 | 0 |

| week 32 | 17 | 41 | 3 | |

| week 33 | 23 | 67 | 6 | |

| week 34 | 27 | 74 | 8 | |

| week 35 | 26 | 60 | 4 | |

| September | week 36 | 22 | 60 | 5 |

| week 37 | 14 | 38 | 9 | |

| week 38 | 8.2 | 22 | 2 | |

| week 39 | 4.8 | 21 | 2 | |

| October | week 40 | 3.6 | 6 | 0 |

| week 41 | 1.2 | 2 | 1 | |

| week 42 | 0.8 | 3 | 0 | |

| week 43 | 0.8 | 2 | 0 | |

| week 44 | 0.4 | 1 | 1 |

Of the 44 clinical cases acquired within Canada, 64% (n=28) were reported as WNV neurological syndrome, 25% (n=11) as WNV non-neurological syndrome and 11% (n=5) as unclassified/unspecified (Table 1). Among the clinical cases, five deaths associated with WNV infection were reported. In addition, one WNV asymptomatic case was reported. In 2022, the incidence rate for reported WNV clinical cases (n=44) acquired within Canada was 0.11 per 100,000 population.

| Province | Clinical cases | Asymptomatic casesFootnote g | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological | Non-neurological | Unclassified/Unspecified | Total | Rate (per 100,000)Footnote f | ||

| Manitoba | 5 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 0.5 | 0 |

| Ontario | 14 | 10 | 4 | 28 | 0.18 | 0 |

| Québec | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0.1 | 1 |

| Canada | 28 | 11 | 5 | 44 | 0.11 | 1 |

|

||||||

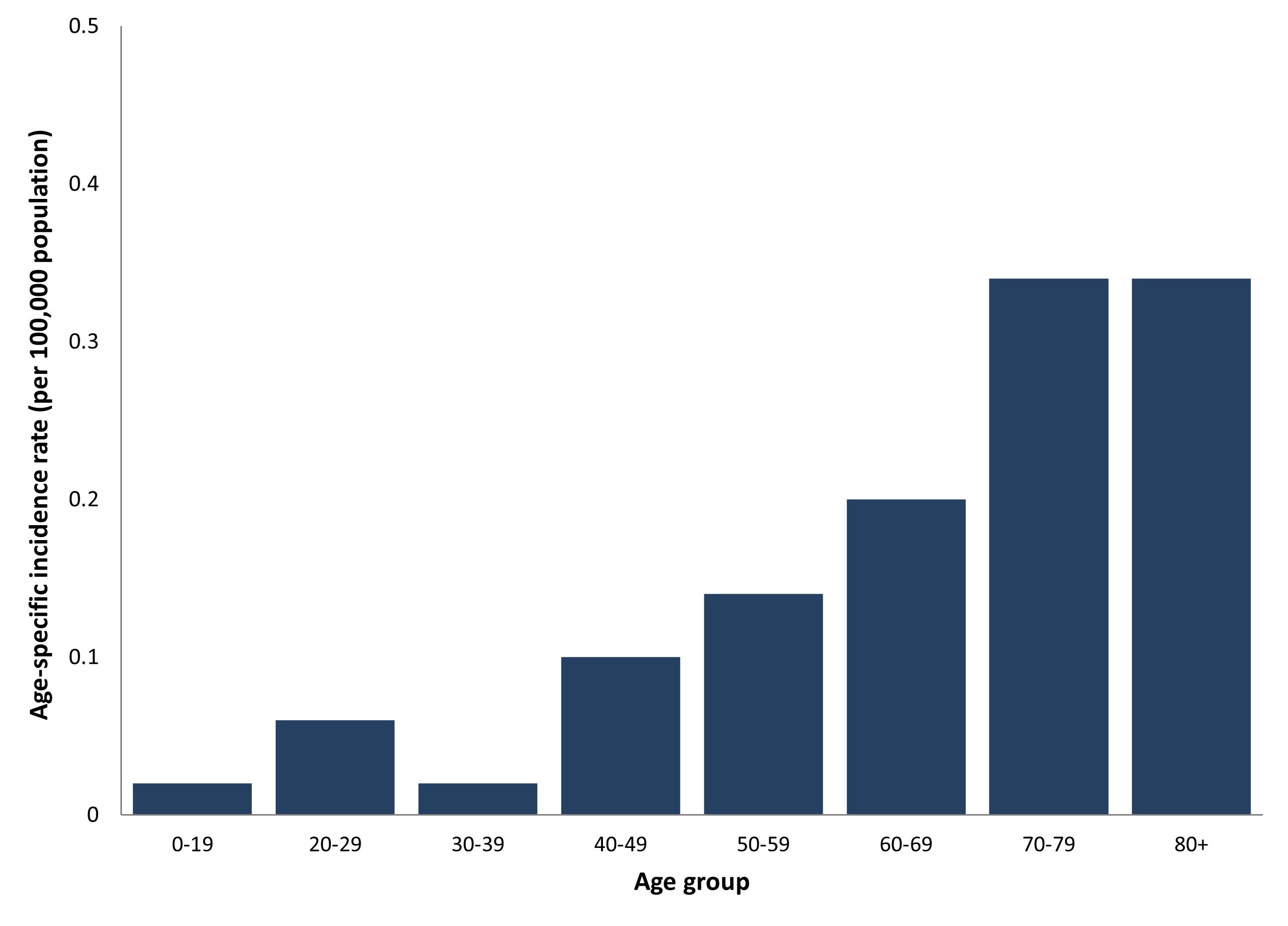

The overall incidence rate for reported WNV clinical and asymptomatic cases (n=45) acquired within Canada in 2022 was 0.12 per 100,000 population. The incidence of reported WNV clinical and asymptomatic cases in females (0.09 per 100,000 population) was lower than the incidence in males (0.15 per 100,000 population). The incidence rate for reported WNV clinical and asymptomatic cases increased with age; the incidence was highest in individuals aged 70-79 and 80 and older, and lowest in the 0-19 and 30-39 age groups (Figure 4). Rates should be interpreted with caution, given the low number of human infections in 2022.

The age group with the lowest number of cases was 30-39 years and the highest number of cases was 70-79 years. More than half (60%) of cases were over the age of 60. Of those aged 60 and older, 74% were neurological cases and 15% were non-neurological cases of WNV and 11% were unclassified clinical cases of WNV. There were five deaths associated with WNV infection and all deaths were in cases over 60 years of age. There was one asymptomatic case reported in the 0-19 age group.

Figure 4. Age-specific incidence rateFootnote h (per 100,000 population) of reported human West Nile virus cases (clinical and asymptomatic) in Canada, 2022

Figure 4 - Text description

Age-specific incidence rateFootnote h (per 100,000 population) of reported human West Nile virus cases (clinical and asymptomatic) in Canada, 2022

| Age group | Age-specified incidenceFootnote h rate (per 100,000 population) |

|---|---|

| 0-19 | 0.02 |

| 20-29 | 0.06 |

| 30-39 | 0.02 |

| 40-49 | 0.10 |

| 50-59 | 0.14 |

| 60-69 | 0.20 |

| 70-79 | 0.34 |

| 80+ | 0.34 |

- Footnote h

-

Age-specific incidence rates were calculated using Q4 2022 Statistics Canada population estimates.

Travel-related cases

There was one case that reported travel outside of Canada to the Netherlands and one case reported travel but did not specify a location.

There were nine cases that reported travel within Canada, including eight cases that traveled within the province or territory of residence (Ontario: n=3, Manitoba: n=5) and one case that traveled outside the province or territory of residence but within Canada (Ontario: n=1).

Mosquito, wild bird and horse surveillance

During the 2022 mosquito season, 15,077 mosquito pools were tested for WNV in three provinces and one territory: Ontario (n=13,185), Manitoba (n=1,399), Saskatchewan (n=293) and Northwest Territories (n=200). Of these, 128 (0.9%) pools tested positive for WNV: 89 in Ontario and 39 in Manitoba (Table 2). There were no WNV positive pools reported in Saskatchewan or the Northwest Territories. In 2022, the percent of mosquito pools positive for WNV was highest in Manitoba (2.8%). The percent positivity for tested mosquito pools in 2022 was similar to the percent positivity reported in 2021 (1.4%).

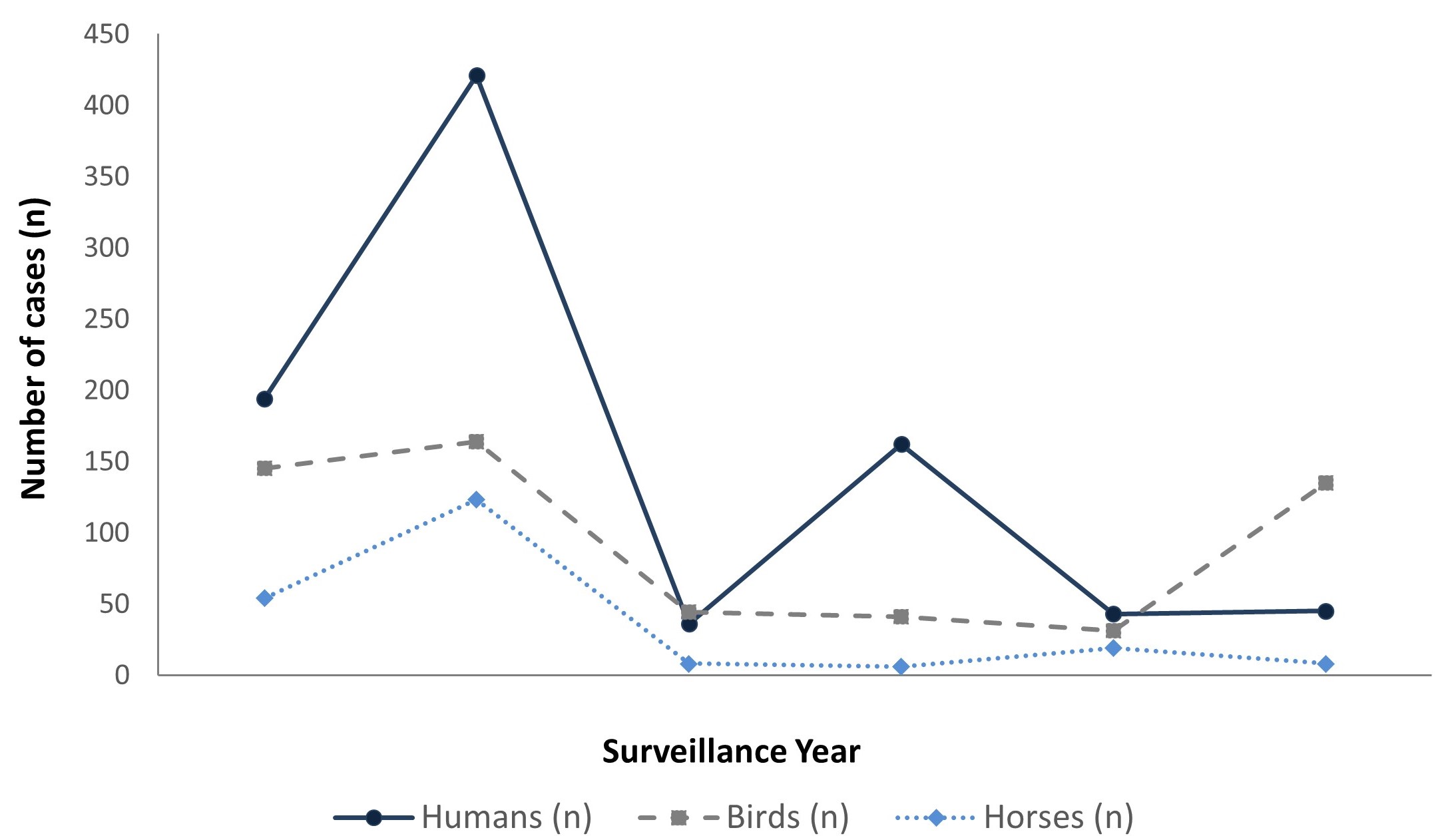

The CWHC tested 345 dead wild birds for WNV, and the province of Manitoba separately tested dead wild birds for WNV (the number tested by Manitoba is unknown). In 2022, WNV was detected in 135 dead wild birds from early April to late November in Ontario (n=56), Québec (n=71) and Manitoba (n=8) (Table 3). Of the 127 dead wild birds tested by the CWHC, 37% were positive for WNV. The number of dead wild birds positive for WNV in 2022 was high compared to the number of positive birds in 2020 and 2021, and more than the average annual number of dead wild birds positive for WNV in the previous five years (mean: 85) (Figure 5).

The CFIA was notified of eight horse WNV cases in the following three provinces: Saskatchewan (n=5), Manitoba (n=2) and Québec (n=1) (Table 3). The number of horse cases in 2022 (n=8) was less than the number of cases in 2021 (n=19), and lower than the average annual number of horse cases in the previous five years (mean: 42) (Figure 5).

| Province | Number of positive Pools | Total pools tested | Percent positive pools | Month with highest percent positivityFootnote j |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saskatchewan | 0 | 293 | 0% | N/A |

| Manitoba | 46 | 1,643 | 2.80% | August |

| Ontario | 89 | 13,185 | 0.70% | August |

| Northwest Territories | 0 | 200 | 0% | N/A |

| Total | 135 | 15,321 | 0.9% | ------ |

|

||||

| Province | Number of positive birds | Number of positive horses |

|---|---|---|

| Saskatchewan | 0 | 5 |

| Manitoba | 8 | 2 |

| Ontario | 56 | 0 |

| Québec | 71 | 1 |

| Total | 135 | 8 |

- Footnote k

-

Horses are reported by the province in which they reside. Birds are reported by the province where the dead wild bird was found.

Figure 5 - Text description

Reported human West Nile virus cases (clinical and asymptomatic), positive dead wild birds and positive horse cases in Canada, 2017-2022

| Number of cases | Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

| Humans | 194 | 421 | 36 | 162 | 43 | 45 |

| Horses | 54 | 123 | 8 | 6 | 19 | 8 |

| Birds | 145 | 164 | 44 | 41 | 31 | 135 |

California serogroup (CSG) viruses

In 2022, the NML identified a total of three human CSG virus infections. Further testing confirmed two infections were Jamestown Canyon virus and one infection was snowshoe hare virus. Additionally, the province of Québec separately reported 15 human CSG virus infections (1 confirmed, 14 probable); of which, 11 were confirmed as Jamestown Canyon virus, three were confirmed as snowshoe hare virus, and one was unspecifiedFootnote 2. However, these 15 infections were classified using a different case definitionFootnote 3 than the three infections reported by the NML.

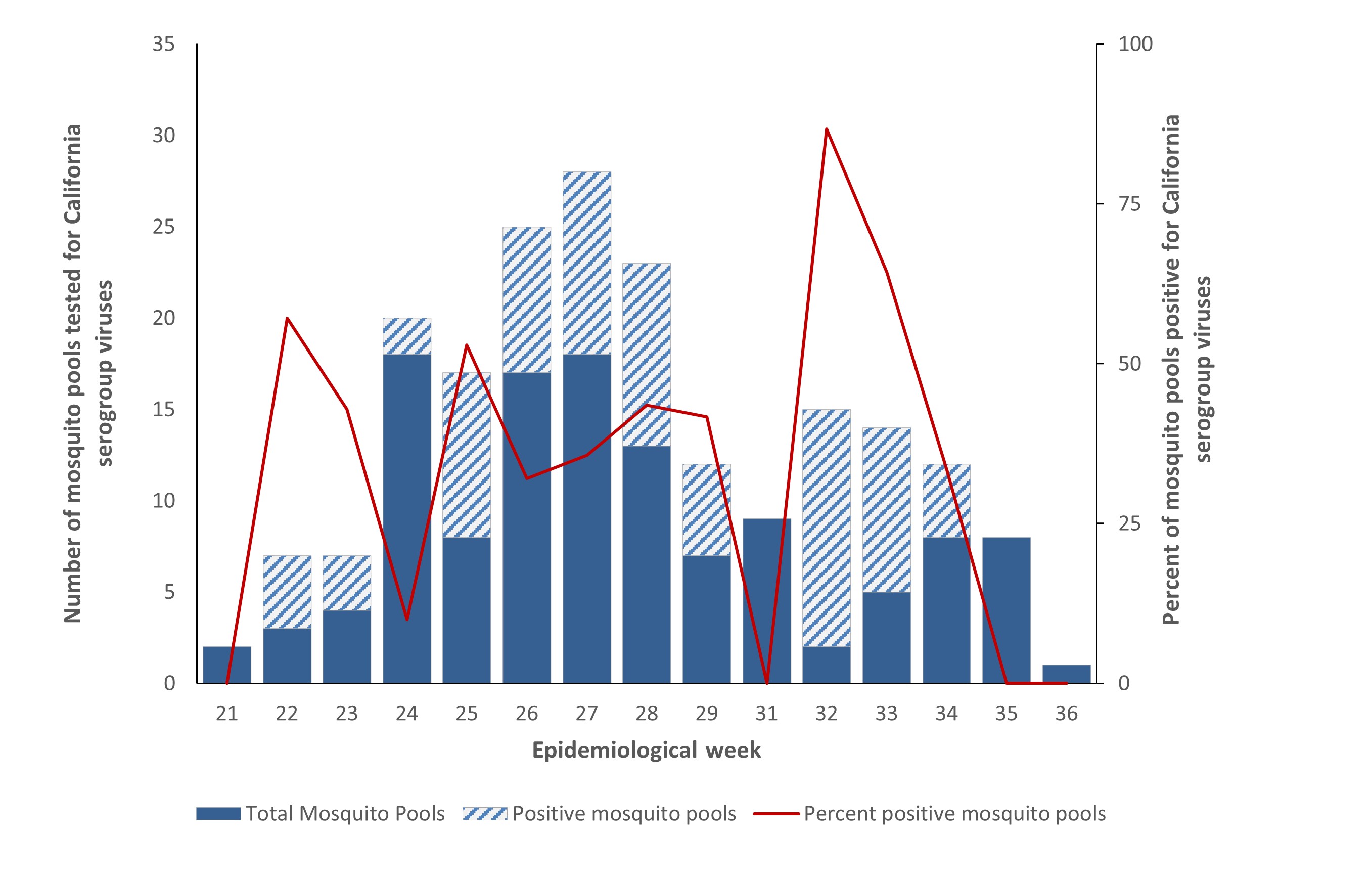

In 2022, the Northwest Territories tested 200 mosquito pools for CSG viruses; of which, 39% (n=77) tested positive. This is slightly less than the proportion of pools that tested positive in the Northwest Territories in 2021 (42%). The collection dates for positive mosquito pools in 2022 ranged from June 2 to August 24. Epidemiological week 32 (early August) had the highest number of mosquito pools positive for CSG viruses (n=13), as well as the highest proportion of mosquito pools positive for CSG viruses (87%) (Figure 6).

Figure 6 – Text description

Number of mosquito pools tested for California serogroup viruses, number of positive mosquito pools and percent positivity by epidemiological week in the Northwest Territories, 2022

| Epidemiological weekFootnote l | Negative mosquito pools | Positive mosquito pools | Total pools | Percent positive mosquito pools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| week 21 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| week 22 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 57.1 |

| week 23 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 42.9 |

| week 24 | 18 | 2 | 20 | 10.0 |

| week 25 | 8 | 9 | 17 | 52.9 |

| week 26 | 17 | 8 | 25 | 32.0 |

| week 27 | 18 | 10 | 28 | 35.7 |

| week 28 | 13 | 10 | 23 | 43.5 |

| week 29 | 7 | 5 | 12 | 41.7 |

| week 30 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 41.7 |

| week 31 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| week 32 | 2 | 13 | 15 | 86.7 |

| week 33 | 5 | 9 | 14 | 64.3 |

| week 34 | 8 | 4 | 12 | 33.3 |

| week 35 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| week 36 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

|

||||

Eastern equine encephalitis (EEE) virus

In 2022, there was one human case of EEE reported by Ontario. There were no cases of EEE in horses reported to the CFIA. During the 2022 mosquito season, 73 mosquito pools were tested for EEE virus in Ontario; of which, no pools were found to be positive.

Discussion

In 2022, the incidence of WNV cases reported in humans in Canada was low. The low incidence of WNV in humans was accompanied by low evidence of WNV activity in horses and mosquitoes across multiple jurisdictions in Canada during the 2022 mosquito season. In contrast, WNV activity observed in dead wild birds increased in 2022, and the number of reported dead wild birds positive for WNV was greater than the average over the previous five years.

The increased WNV activity in dead wild birds could be related to the increase in bird surveillance efforts for detection of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI/H5N1). In the Ontario/Nunavut Region, CWHC bird surveillance efforts drastically increased after the first detection of HPAI was reported in Ontario in March 2022Footnote 4Footnote 5. All bird species were first screened by the CWHC for HPAI prior to testing for WNV in the Ontario/Nunavut RegionFootnote 4. In 2022, there were 56 WNV positive dead wild birds reported by the CWHC from Ontario, which is high compared to the 11 reported in 2021. Similar trends were seen in Québec where the CWHC reported 71 WNV positive dead wild birds in 2022, but only 14 in 2021. In total, the CWHC tested 345 dead wild birds for WNV in 2022, but only tested 164 in 2021. In 2022, the first report of a dead wild bird positive for WNV was much earlier in the season (early April) compared to past years which was likely detected due to increased surveillance.

Low numbers of WNV infections were observed in other jurisdictions in North America. In the United States (US), the CDC reported 1,132 WNV human cases in 2022, which was lower than the average number of cases reported in the previous five years and lower than outbreak years such as 2018 (n=2,647) and 2021 (n=2,911)Footnote 6. In 2022, there were 93 reported deaths attributed to WNV in the USFootnote 6.

Higher numbers of WNV infections were observed in jurisdictions outside of North America. The European Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (ECDC) reported 1,113 locally acquired WNV human cases in 2022, including 92 deaths, in Europe (European Union and European Economic Area countries)Footnote 7. This is the highest number of reported WNV human cases in Europe since 2018, which was an outbreak year reaching a total of 1,503 reported WNV cases and 140 deathsFootnote 8. Countries in Europe that reported the highest counts of WNV human cases in 2022 included Italy (n=723) and Greece (n=283)Footnote 7. In addition, there was increased WNV activity in horses and birds in Europe. In 2022, there were almost twice as many horse cases reported as 2021, but there were still fewer than in outbreak years such as 2018Footnote 6Footnote 7. There were 323 reported WNV outbreaks among birds in 2022Footnote 7, which is a sharp increase compared to the eight reported WNV outbreaks among birds in 2021Footnote 9.

Annual fluctuations in the reported number of human WNV cases, dead wild bird and horse infections, and percent positivity in mosquito pools are expected. The annual incidence of WNV is impacted by a variety of factors including but not limited to climatic conditions, vector abundance and human behaviour. In 2022, many areas in Canada experienced a cool, wet spring, but warmer than average summer monthsFootnote 10. The summer season in 2022 was the third warmest in the past 75 years, with only 2012 and 1998 having warmer summersFootnote 10. It is possible that cool spring temperatures contributed to lower mosquito activity at the start of the mosquito- borne disease transmission season in some jurisdictions. For example, in Ontario the main vector of WNV, Culex mosquitoes, are most active in warmer temperaturesFootnote 11. In 2022, the slower start to the mosquito season may have resulted in the reported delay in WNV positive mosquito pools compared to outbreaks years of WNV human cases in OntarioFootnote 12.

In Canada, three CSG virus infections in humans were reported in 2022 by NML and 15 infections were reported by Québec. California serogroup viruses, such as Jamestown Canyon virus and snowshoe hare virus, are endemic in Canada. As CSG virus infections are not nationally notifiable diseases in Canada, there is currently no formal surveillance system in place to monitor, track and report cases. Furthermore, infections caused by CSG viruses are likely under-diagnosed due to factors such as a lack of awareness among healthcare professionals in CanadaFootnote 1. In 2022, the proportion of mosquito pools positive for CSG viruses in the Northwest Territories was high (39%) compared to other mosquito-borne diseases such as WNV. Mosquito surveillance strategies may vary for different diseases and between jurisdictions, which may contribute to differences in the number of mosquito pools tested and the percent positive. There is some evidence that suggests the prevalence of CSG virus infections in Canada may increase with climate changeFootnote 13. In the literature, it is hypothesized that climate change could contribute to northward expansion of the range of CSG viruses in the Arctic, and amplified transmission due to a longer vector-biting seasonFootnote 14.

There were no reported EEE cases in horses and no mosquito pools were positive for EEE virus. However, there was one human case of EEE reported in a resident of Ontario in 2022. To date, only two other known human cases of EEE have ever been reported in Canada, a case in 2016 and another case in 2020, both residents of Ontario. Cases of EEE remain relatively rare. As with CSG virus infections, EEE virus infections are not nationally notifiable in humans and there is no formal surveillance system in place to classify and count cases. In the US, there are typically only a few EEE cases reported each year. In 2022, there was one human case of EEE reported in the US, which was lower than the average annual number of human cases of EEE in the previous 10 years (mean: 10)Footnote 15.

Public health conclusions

West Nile virus is the leading cause of domestically acquired mosquito-borne disease in Canada. WNV illness can occur in people at any age, but groups at higher risk of developing neurological disease include people over the age of 50 and some immunocompromised personsFootnote 16. There continues to be annual fluctuations in the number of WNV infections in people and other indicators of WNV activity such as infections in birds and horses, and positive mosquito pools. Other viruses such as EEE virus and CSG viruses cause sporadic infections in humans. There are no vaccines or specific treatments for human WNV, CSG virus and EEE virus infections. Therefore, prevention strategies including education and promotion of personal protection (i.e., long-sleeved clothing, permethrin-treated clothing, window screens and mosquito repellents) from mosquito bites, as well as mosquito control, are critical for decreasing the risk of mosquito-borne infections in people. Ongoing national surveillance is needed to help target prevention and control efforts, and increase awareness among healthcare professionals, especially of CSG and EEE viruses.

For more information including populations-at-risk, symptoms and treatment, please refer to Canada.ca.

Acknowledgements

The Public Health Agency of Canada would like to acknowledge the provincial and territorial WNV and other mosquito-borne disease programs, Canadian Blood Services, Héma-Québec, the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative (CWHC), and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) for their participation in the National WNV Surveillance Program.

References

- Footnote 1

-

Ludwig A, Zheng H, Vrbova L, Drebot MA, Iranpour M, Lindsay LR. Increased risk of endemic mosquito-borne diseases in Canada due to climate change. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2019; 45(4):90-7.

- Footnote 2

-

Quebec Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux. Surveillance des maladies d’intérêt transmises par des moustiques au Québec. [Internet]. 05 July 2023 [cited on 05 March 2024]. Available from: https://www.msss.gouv.qc.ca/professionnels/zoonoses/surveillance-des-maladies-d-interet-transmises-par-des-moustiques-au-quebec/les-virus-du-serogroupe-californie/.

- Footnote 3

-

Surveillance des maladies à déclaration obligatoire au Québec [Internet]. July 2019 [cited on 25 January 2024]. Available from: https://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/fichiers/2019/19-268-05W.pdf.

- Footnote 4

-

Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative. CWHC Ontario/Nunavut Dead Bird West Nile Virus Testing Summary for 2022 [Internet]. 06 January 2022 [cited on 1 March 2024]. Available from: https://www.cwhc-rcsf.ca/west_nile_virus.php.

- Footnote 5

-

Canadian Food Inspection Agency. Highly pathogenic avian influenza in wildlife dashboard [Internet]. [cited on 1 March 2024]. Available from: https://cfia-ncr.maps.arcgis.com/apps/dashboards/89c779e98cdf492c899df23e1c38fdbc.

- Footnote 6

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Final Cumulative maps and Data for 1999-2022 [Internet]. 11 October 2023 [cited on 29 December 2023]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/westnile/statsmaps/cumMapsData.html.

- Footnote 7

-

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Epidemiological Update: West Nile virus transmission season in Europe, 2022 [Internet]. 30 June 2023 [cited on 05 March 2024]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/epidemiological-update-west-nile-virus-transmission-season-europe-2022.

- Footnote 8

-

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Epidemiological Update: West Nile virus transmission season in Europe, 2018 [Internet]. 14 December 2018 [cited on 05 March 2024]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/epidemiological-update-west-nile-virus-transmission-season-europe-2018.

- Footnote 9

-

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Epidemiological Update: West Nile virus transmission season in Europe, 2021 [Internet]. 24 March 2022 [cited on 05 March 2024]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/epidemiological-update-west-nile-virus-transmission-season-europe-2021.

- Footnote 10

-

Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC). Canada’s top 10 weather stories of 2022 [Internet]. 25 January 2023 [cited on 1 March 2024]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/top-ten-weather-stories/2022.html.

- Footnote 11

-

Wijayasri S, Nelder MP, Russell CB, Johnson KO, Johnson S, Badiani T, Sider D. West Nile virus illness in Ontario, Canada: 2017. Can Commun Dis Rep 2019;45(1):32-7.

- Footnote 12

-

Public Health Ontario. Total number of WNV positive mosquito pools for all species by surveillance week. [Internet]. 10 July 2021 [cited on 05 March 2024]. Available from: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/Data-and-Analysis/Infectious-Disease/West-Nile-Virus.

- Footnote 13

-

Ogden NH, Lindsay LR, Ludwig A, Morse AP, Zheng H, Zhu H. Weather-based forecasting of mosquito-borne disease outbreaks in Canada. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2019;45(5):127-32.

- Footnote 14

-

Snyman J, Snyman LP, Buhler KJ, Villeneuve C-A, Leighton PA, Jenkins EJ, Kumar A. California Serogroup viruses in a changing Canadian arctic: A Review. Viruses. 2023; 15(6):1242.

- Footnote 15

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Eastern Equine Encephalitis historic data (2003-2022) [Internet]. 11 October 2023 [cited on 25 January 2024]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/eastern-equine-encephalitis/data-maps/historic-data.html.

- Footnote 16

-

Patel H, Sander B, Nelder MP. Long-term sequelae of West Nile virus-related illness: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015; 15(8):951-9.disease outbreaks in Canada. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2019;45(5):127-32.