Rapid Review: An intersectional analysis of the disproportionate health impacts of wildfires on diverse populations and communities

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 3.2 MB, 26 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: July 2024

Cat.: HP55-11/2024E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-72757-8

Pub.: 240379

Table of contents

- Sex and Gender Based Analysis Plus (SGBA Plus)

- Applying an intersectional approach to wildfires in Canada

- The differential impact of wildfires due to social and structural determinants of health

- Wildfire smoke

- Equity-related considerations during wildfires

- Limitations

- References

In 2023 Canada experienced an unprecedented wildfire season, where larger areas of the country were impacted with greater severity.Footnote 1 What was seen in 2023 was a continuation of the trend of longer wildfire seasons, with more frequent and extreme fire behaviour.Footnote 2Footnote 3 It is expected that wildfires will continue to occur throughout the coming years, and modeling suggests that by 2100 the overall fire occurrence could increase by as much as 75%.Footnote 4Footnote 5Footnote 6Footnote 7 In Canada, the wildfire season typically runs from early April to late October, however for 2024, Alberta announced that their wildfire season will start 10 days earlier.Footnote 8

Wildfires are a key public health issue because they are widespread, the health impacts are severe, and inequitably distributed.Footnote 9 In addition to their impact on the physical and mental health of populations, the impacts of wildfires are experienced differently across population groups based on their intersecting social determinants of health (SDOH) such as age, geography, gender, and income.Footnote 10 An important lesson learned from the COVID-19 pandemic was the inequitable impacts of emergencies on populations already in situations of vulnerabilityFootnote 9Footnote 11 and the creation of new inequities by the emergency.

Systemic inequities drive exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity to climate hazards as different individual factors and SDOH influence people's climate vulnerability. Therefore, understanding how different population groups, especially those already in situations of vulnerability, experience and are affected by wildfires ensures that health equity considerations are prioritized and embedded in emergency preparedness and response, and in public health action on climate change.Footnote 9Footnote 11 By addressing societal inequities and vulnerabilities, public health outcomes can be improved for all.

Sex and Gender Based Analysis Plus (SGBA Plus)

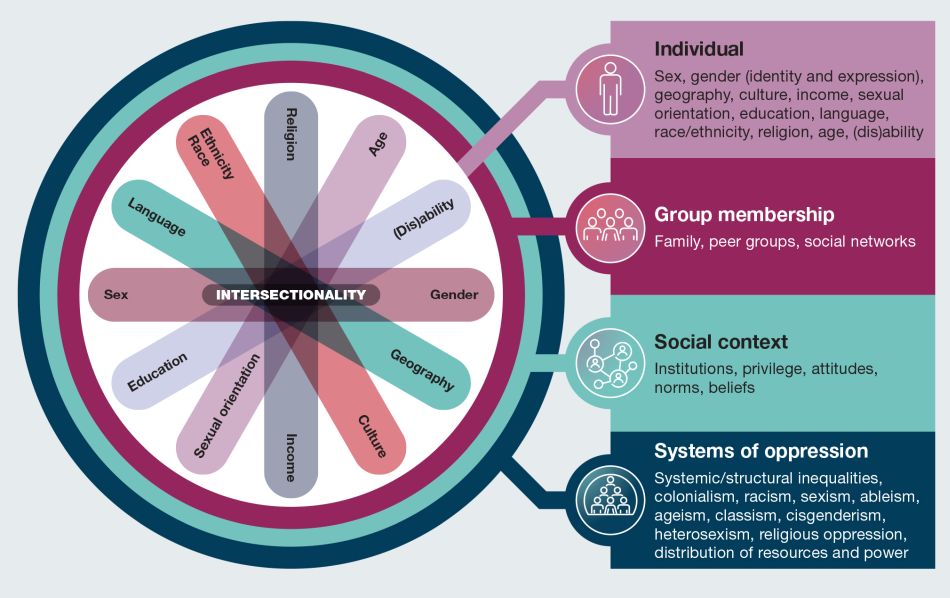

Sex- and Gender-Based Analysis Plus (SGBA Plus) is a Government of Canada priority and supports the advancement of health equity considerations in all policies, programs, and practices across the Health PortfolioFootnote a. SGBA Plus considers how multiple social determinants of health such as race, age, income, sexual orientation, geographic location, and socioeconomic status intersect to influence health outcomes. The intersections between these identities occur within a context of connected systems and structures of power (e.g., laws, policies, governments) to shape experiences. SGBA Plus is an intersectional analytical approach that examines how various intersecting structural and social determinants of health (SDOH) influence equitable health outcomes.Footnote 12

Figure 1. Demonstrates that looking at individual identities can help us understand how these systems of power create compounding experiences of discrimination among people with multiple marginalized identities.Footnote 13

Figure 1 : Descriptive text

This figure illustrates some of the determinants of health that intersect to shape our experiences and realities. A figure depicting social identities is centred within a concentric circle of four layers. From the centre of the circle, and moving outwards, the figure describes intersectionality considerations related to individual-level factors, group membership, social context, and systems of oppressions, that is, from individual identities to increasingly broad levels of influence.

At the centre, seven oblong shapes of differing colours overlap and fan out. At the end of each oblong an individual social identity is named. The individual social identities named on the figure are: sex, race, language, ethnicity, income, age, (dis)ability, gender, geography, Indigenous identity, culture, religion, sexual orientation, and education.

The second layer of the circle directly surrounding the individual social identities is "Group membership" with the following examples listed: family, peer groups, and social networks.

The third layer of the circle surrounding group membership is "Social context" with the following examples listed: institutions, privilege, attitudes, norms, and beliefs.

The outermost level, which surrounds social context is "systems of oppression", with the following examples listed: systemic/structural inequalities, racism, sexism, ableism, ageism, classism, religious oppression, and distribution of resources and power.

The public health consequences of wildfires are multifaceted and require an intersectional approach to understand their differential impact across diverse population groups.

This rapid review explored the evidence of the disproportionate health impacts of wildfires on certain communities and populations based on intersecting structural and social determinants of health. As wildfires are an emerging public health issue we wanted to generate a rapid review to support those working on a range of related public health and public policy interventions. The suggestions on key health equity-related considerations related to wildfires and wildfire smoke are based on this review and are provided for consideration by those planning for and responding to wildfire-related events.

Applying an intersectional approach to wildfires in Canada

Health outcomes

Increased wildfire activity and intensity, increase the risk for adverse physical and mental health outcomes for people living in Canada. Key implications of wildfires also include displacement of communities, destruction of ecosystems, and compromised air quality, all of which have long-term impacts on health outcomes.Footnote 14 Wildfires and wildfire smoke can trigger a range of negative physical and mental health outcomes.Footnote 14Footnote 15 The wide-ranging evidence to support the differential health impacts of wildfires and wildfire smoke on diverse population groups is summarized below.

Physical health

Wildfires impact physical health primarily due to fire, smoke, and heat.Footnote 15Footnote 16Footnote 17 The main impacts were primarily respiratory and cardiovascular morbidity and ophthalmic problems.Footnote 15 In addition, severe burns resulting from direct contact with the fire require specialized care and carry a risk of multi–organ complications.Footnote 15 Finally, there are the wider health implications that result from the pollution of the air, water, and land after a wildfire.Footnote 15Footnote 17 Toxic chemicals from wildfires can be deposited on vegetation and washed into bodies of water contaminating them, and impacting water potability and the health of aquatic species.Footnote 18

Exposure to wildfire smoke is strongly associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality, followed by respiratory and cardiovascular mortality, adverse respiratory effects, such as exacerbations of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD and an increased risk of reproductive and developmental effects (for example, low birth weight).Footnote 19

Mental health

There is evidence of increased rates of mental health impacts (for example, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder) in communities impacted by wildfires, which have been linked with both wildfire events and wildfire smoke.Footnote 14Footnote 20Footnote 21 Studies also demonstrate a strong correlation between negative mental health outcomes—such as major depressive disorder (MDD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) — and experiences of wildfires among adult and youth populations.Footnote 22Footnote 23Footnote 24Footnote 25. This association was more prominent for people with pre-existing mental health conditionsFootnote 22Footnote 23Footnote 25 and for those who experienced the disaster in greater proximity through witnessing homes burning, having their home destroyed, or experiencing a relocation.Footnote 22

Amongst Grade 7-12 students impacted by the Fort McMurray wildfire, scores for depression symptoms, suicidal thinking, and tobacco use were higher than controls 18 months after the fire.Footnote 26 These symptoms unfortunately didn't decrease with time, and three and half years after the Fort McMurray wildfire the mental health of these students had further declined.Footnote 27

The differential impact of wildfires due to social and structural determinants of health

Geographic location/isolation

While wildfires have become increasingly widespread in recent years, there are specific regions in Canada that are disproportionately affected. 2023 was the worst wildfireFootnote 28 season to date with an estimated 2,619 fires as of June 19, 2023.Footnote 16 Affected provinces include British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, Quebec, and Nova Scotia.

Geographic location, specifically the distinction between rural and urban centres, has an impact on health outcomes and contributes to disproportionate experiences in public health issues. Rural communities face unique impacts in response to wildfires as they do not always have the infrastructure to readily handle evacuation needs, may face challenges with communication, and experience issues with obtaining support from external parties.Footnote 29 A qualitative study exploring public health practitioners' perceptions of responses to wildfire smoke events across Canada, demonstrated that practitioners felt remote communities often did not have the resources and infrastructure available to have designated community clean-air shelters or other indoor spaces that would be appropriate for prolonged stay during smoke events.Footnote 30

A study conducted in four rural sites in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia to understand the impact of wildfires on rural communities, found that rural settings generally did not have the infrastructure for available personnel to respond to disasters as urban areas do.Footnote 31 Wildfires also posed specific issues for ranches and farms, as demonstrated by the McLure fire where relocation of animals with adequate feed and water was difficult. This led some livestock owners to opt to stay with their livestock which placed them at heightened risk and made them vulnerable to injury and death.Footnote 31 Issues with communication between authorities and the public also made it difficult for community members to understand events that were occurring, which added to their individual stress levels and hindered recovery.Footnote 31 In general, rural communities are often well-connected and familiar with their neighbors; therefore when large groups of external personnel enter the community to respond to the wildfires, it can be intimidating, especially during a period of recovery.Footnote 31

Indigenous identity

It is estimated that First Nations communities make up 42% of evacuations due to wildfires but only make up 5% of people living in Canada.Footnote 1 As of July 2023, 106 wildfires affected 93 First Nations, leading to 64 evacuations impacting nearly 25,000 people.Footnote 32 Indigenous communities disproportionately experience both adverse mental health and physical health outcomes due to wildfires. Recent wildfires have displaced many remote and Northern Indigenous communities, leaving many without the ability to participate in their traditional ways of life and cultural practices. The impact of wildfires on Indigenous Peoples is influenced by colonialism,Footnote 33 and has forced many Indigenous Peoples to live in isolation or in communities that are isolated from the rest of society. Their geographic isolation makes it difficult to access basic goods, services, and other resources that are necessary for mitigating and building resilience against the impacts of wildfires. In addition, Indigenous communities often depend on the land for food, water, recreation, and cultural practices. Therefore, wildfires disrupt Indigenous ways of life and threaten important cultural activities, such as hunting, fishing, harvesting, and gathering.Footnote 32 Evacuation can also result in the disruption of traditional and subsistence activities, and the collection and use of traditional healing medicines and foods, which can negatively impact mental and spiritual well-being. After a wildfire, residents who return home may face financial, health, and social stresses associated with the loss of personal property and having to rebuild homes and community. In addition, they may return to a devastated landscape that serves as a daily reminder of their loss. This can lead to solastalgia, a form of mental or existential distress caused by environmental change.Footnote 34

Furthermore, Indigenous communities are often excluded from emergency preparedness and relief measuresFootnote 35, that undermine Indigenous rights to self-determination and autonomy. For example, Indigenous Peoples are often left out of decision-making processes regarding forest management before and after wildfire events, despite being the traditional keepers and stewards of the land.Footnote 32 In addition, it is only recently that the role of Indigenous Peoples's traditional fire stewardship practices has been recognized and supported.Footnote 36Footnote 37 Recognizing Indigenous sovereignty is crucial for ensuring cultural preservation and the protection of ancestral lands.

In 2014, a retrospective cohort study examining the cardiorespiratory outcomes of wildfire smoke in the Northwest Territories found that among residents in and around Yellowknife, Dene had higher Emergency Room visits for asthma, and pneumonia rates were higher among Inuit compared to non-Indigenous residents.Footnote 38

The socio-cultural/economic conditions that impacted Indigenous Peoples the most after a wildfire evacuation were primarily the lack of both culturally sensitive services and access to funding. Following the 2016 Horse River wildfire in Northern Alberta, a qualitative study demonstrated that service providers felt the delivery of mental health and wellness services to rural and remote Indigenous communities was inconsistent prior to the wildfire and exacerbated after the wildfire.Footnote 39 They also found that services lacked cultural appropriateness, were not adequately resourced, and overlooked long-term recovery. Of those who experienced the 2014 Northwest Territories wildfire season, First Nations interviewees experienced challenges to their food security and livelihoods due to restricted ability to engage in traditional land-based activities and reduction to sources of country foods, limiting employment and income sources (for example, hunting, foraging, fishing).Footnote 40

These findings were reinforced by a report from the House of Commons Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs that examined the impacts of the 2017 wildfires on First Nations communities across Canada.Footnote 41 The report found that many Indigenous Peoples also faced additional economic challenges during evacuations and recovery phases. While they were eligible for reimbursement of funds utilized during an emergency through Indigenous Service programs; many experienced difficulties claiming these expenses due to challenges with applying for reimbursement and not always receiving the full amount of a claim.Footnote 41Footnote 42

For First Nations evacuees, there was a lack of space for the practice of traditional activities and preparation of traditional foods, as well as a lack of mental health resources for those being temporarily housed in shelters.Footnote 41

Finally it was noted that the evacuation measures conducted in Indigenous communities served as traumatic reminders of being taken away to residential schools and/or the Sixties Scoop as some were forced onto buses and separated from familyFootnote 41.

A community-based qualitative case study examining how residents of Sandy Lake First Nation were impacted by the 2011 wildfire evacuation found that a lack of pre-event preparedness resulted in some Elders with medical conditions being evacuated without a caregiver and families were separated and displaced during evacuation operations.Footnote 43 During evacuations, additional challenges included transportation issues that prevented large families from being evacuated together in one vehicle and language barriers that caused stress for non-English speakers.Footnote 42 Finally, during the 2011 Alberta wildfire, members of the Whitefish Lake First Nation 459 who experienced poverty faced complications as they did not have extra funds to pay upfront for expenses incurred by the evacuation.Footnote 42

Race and ethnicity

Environmental racism refers to "environmental policies, acts, and decisions that, intentionally or not, disproportionately disadvantage racialized individuals, groups, and communities."Footnote 44 In terms of Canada's wildfires, racialized communities—including Indigenous populations (see section on "Indigenous Identity")—are inequitably impacted by displacement, loss of homes, disruption of traditional livelihoods, and adverse health effects from smoke inhalation.Footnote 33 In Canada, racialized populations are more likely to live with low-income and poor housing conditions compared to the general population, which can exacerbate the impacts of damages incurred by wildfires.Footnote 45Footnote 46 In addition, historical land use policies have placed racialized populations at higher risk of exposure to environmental threats, including wildfires.Footnote 47Footnote 48

There is a paucity of Canadian literature that examined health outcomes among racialized populations. However, a study that examined the mental health service utilization rates among evacuees during the Fort McMurray wildfire found that racialized evacuees were less likely to receive mental health services.Footnote r9 This finding was supported by studies conducted in the United States that demonstrate the disproportionate impact on racialized communities due to differential exposure and adaptive capacities.Footnote 50Footnote 51

Sex and gender

Women are disproportionately impacted by climate-related threats due to their long-standing social roles as caretakers, vulnerability to gender-based violence, and pre-existing mental health challenges.Footnote 52Footnote 53Footnote 54 Studies found that women are more vulnerable to climate-related events due to gender inequalities, that lead to having lower income, greater caregiving responsibilities, mobility constraints, and less access to financial or life-sustaining resources.Footnote 55 (see section on "Family and Pregnancy")

Results from several studies conducted after the 2016 Fort McMurray wildfire found that women experience worse mental health impacts in comparison to men. This was also noted for people who did not identify within the gender binary. Among Grade 7-12 students, those who identified as femaleFootnote b exhibited higher mental health symptom scores, higher rates of probable diagnosis of MDD, PTSD, and GAD, and lower scores for self-esteem, quality of life, and resilience in comparison to their male-identifying students.Footnote 27 Students who identified with another gender or preferred not to state their gender identity exhibited worse mental health outcomes compared to both their female- and male-identifying counterparts.

When the health outcomes of evacuated workersFootnote 57 and college studentsFootnote 58 were examined, a greater proportion of women compared to men experienced symptoms of MDD and GAD, as well as PTSD. Gender was also a statistically significant predictor amongst evacuated adults, with women being more likely than men to seekFootnote c, and require mental health services.Footnote 49Footnote 59 Despite the limited amount of evidence, these studies point to the importance of considering the distinct needs and barriers experienced by gender-diverse populations during wildfires and other climate-related events.

Age

Age is associated with physical and mental health outcomes related to wildfires. It was observed that non-modifiable biological factors related to age such as physical capacity, immune function, and social and structural determinants intersect with age to exacerbate or mitigate risk factors and adverse health outcomes. Social support was observed to be important for outcomes in older adults. Those who had social support at the community and individual level were more likely to survive wildfires.Footnote 60 A reliable and supportive social network also provides critical psychological and emotional support for older adults during wildfire evacuations.Footnote 60

People younger than 25 years of age generally seem to have worse mental health outcomes than those above 40 years of age. A cross-sectional study examining predictors of resilienceFootnote d in residents, five years after the 2016 Fort McMurray wildfire found that those younger than 25 years old were more likely to have low resilience compared to those older than 40 years.Footnote 61 Other cross-sectional studies investigating mental health impacts after the same wildfire found that those younger than 40 years were more likely to develop MDDFootnote 25 and those 25 years or younger were more likely to present with MDD, GAD, and PTSD.Footnote 58

Socioeconomic status

Socioeconomic status (SES) and education are highly interconnected social determinants of health associated with mental health outcomes. Individuals with a lower SES often experience increased stress due to financial instability and low access to resources, which can impact their mental well-being.Footnote 62 Emergencies, such as wildfires and related evacuations may exacerbate these stressors and their impacts on mental health outcomes. Additionally, a lack of socio-economic resources could also impact access to the services and resources required for emergency prevention, mitigation, and recovery.Footnote 63 Among evacuees from the 2016 Fort McMurray wildfire, it was observed that having had financial difficulties due to economic decline in the city before the wildfire was a predictor of developing PTSD, MDD, GAD, insomnia, and substance use.Footnote 23 In addition, the depression scores of participants who experienced financial loss from lack of work were higher than those who did not experience financial loss.Footnote 57 A year after the 2016 Fort McMurray wildfire, participants holding post-secondary education were more likely to receive information and counseling/psychotherapy than those with secondary education or less.Footnote 49

Housing

Poor housing conditions exacerbate exposure to wildfire smoke and increase the risk of adverse mental and physical health outcomes. Housing is a structural determinant of health that intersects with many other social and systemic factors, including SES, race, Indigenous identity, geography, and disability. For instance, Indigenous Peoples were almost twice as likely to live in crowded housing, and three times more likely to live in a dwelling in need of major repairs, in comparison to the non-Indigenous population in Canada.Footnote 64 People living in accommodations without air conditioning or proper ventilation, in shelters, on the street, or in their vehicles were more exposed to wildfire smoke; which is associated with cardiovascular and respiratory diseases.Footnote 65 People who are unhoused or living in housing with poor ventilation or ineffective cooling systems are also particularly susceptible to adverse mental health outcomes.Footnote 66 Finally, those living in precarious housing have fewer opportunities to engage in mitigation strategies against wildfires-related health impacts.Footnote 66 It has to be recognized that although evacuation centers are available to all individuals, stigma and mistrust of authorities can present barriers to access for some.Footnote 67

Occupation

In response to wildfires, people in certain occupations experience greater exposure to wildfire smoke and are therefore at an increased risk of negative health impacts, especially the heightened risk of respiratory morbidity.

When the health effects of wildfire smoke exposure on RCMP officers deployed during the 2016 Fort McMurray were examined, it was found that they were exposed to extremely high levels of wildfire-related air pollutants. They also presented with higher COPD assessment scores and prevalence of asthma than the general population.Footnote 68 Firefighters deployed during wildfire events exhibited ongoing respiratory problems with decreased diffusing capacity of the lung, new onset asthma, hyperactivity with bronchial wall thickening compared to community controlsFootnote 69 and measurable inflammatory responses in the lung which were associated with upper and lower respiratory tract infections.Footnote 70 Occupational groups (for example, firefighters) that work directly to address wildfire emergencies may also experience negative mental health outcomes. A cohort of firefighters deployed during the 2016 Fort McMurray Wildfire had high rates of mental health conditionsFootnote 71 with prevalence estimates for PTSD, anxiety disorders, and depressive disorders at 21.4%, 15.8%, and 14.3% respectively. Importantly the PTSD prevalence rates found in this cohort were higher than previously reported estimates in firefighters (13.5%) not exposed to a major disaster in Canada.Footnote 71

Family and pregnancy

Parents have increased stress and responsibilities in dealing with the aftermath of potential material losses, reorganization of daily life, and concerns about children's safety.Footnote 72 Children may be less cared for as parents have less time for them when addressing the damage and change caused by wildfires. As well, pregnant women and pregnant people experience difficulties with mobility and may be unable to continue normal breastfeeding practices due to disruptions caused by wildfires. Given the intersection of family and pregnancy with gender, women tend to act as caretakers and are likely more impacted in these roles during wildfires (see section on Sex and Gender). The 2011 wildfires, in Slave Lake Alberta affected the everyday life of children as schools and children's clubs were not re-opened after the wildfires ceased and parents often focused on dealing with logistic considerations, leaving them with less time to tend to their children's needs.Footnote 73 Public health practitioners also reported receiving concerns from families with children about the need to keep children indoors to limit smoke exposure, which also limited their children's physical activity.Footnote 30 During and after the Fort McMurray wildfire, it was found that pregnancy was a barrier during evacuations as pregnant women and pregnant people had limited physical capabilities, needed washroom facilities, and experienced fatigue.Footnote 74 Pregnant women and pregnant people also experienced varied stress responses, lack of sleep, and some experienced pregnancy complications (for example, intrauterine growth restriction, preterm births) that were potentially related to heightened stress levels.Footnote 74 Finally, during the Fort McMurray wildfire evacuation, there was a decrease in breastfeeding and increased usage of infant formula.Footnote 75

Faith communities

Faith communities can experience specific barriers and experience certain disruptions when evacuated due to wildfires. It is important to acknowledge and attempt to support faith communities impacted by wildfire response activities. Indigenous Peoples spirituality is land-based so there is a specific and deep level of distress associated with the destruction of the land and disruption of traditional land-based activities as a result of wildfires and the resulting evacuations.Footnote 76 During the 2016 Wildfire, 10% of Fort McMurray's population was Muslim.Footnote 77 They experienced a lack of privacy when needing to stay in group-lodging facilities, a lack of appropriate clothes and food, and additional considerations for spirituality and prayer.Footnote 78 While these observations are limited to Muslim communities and Indigenous Peoples, it is important to recognize that wildfires may negatively impact the faith practices of several other religious communities.

Wildfire smoke

Populations in close proximity to and at great distances from wildfire events are at risk of wildfire smoke, as the air pollutants can be transported thousands of kilometers away.Footnote 79 The health effects of wildfire smoke are an active and growing area of research. To support and inform guidance and actions related to wildfire smoke, Health Canada conducted a weight-of-evidence review of the health outcomes associated with exposure to wildfire smoke based on existing systematic reviews.Footnote 19 There is consistent and strong evidence in the literature that wildfire smoke is associated with an increased risk of premature mortality and adverse respiratory effects (for example, exacerbation of asthma and COPD). There is also some evidence of an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality and morbidity. Additionally, there is some evidence of an association between wildfire smoke exposure and reproductive and developmental effects (for example, low birth weight). For other reproductive and developmental effects and mental health impacts, more research is needed to differentiate the effects attributable to wildfire smoke vs wildfire events.

The literature base also identified some groups that may be disproportionately impacted by wildfires and wildfire smoke, including seniors (65 years and older), children, women, pregnant women and people, Indigenous populations, people living in remote areas, people with pre-existing health conditions, people with lower socio-economic status (SES), and wildland firefighters.Footnote 19 Various factors contribute to these disproportionate risks, including biological and physiological differences due to life stage and/or presence of a comorbidity, and increased likelihood of exposure to wildfires due to location or occupation. Specifically from North American studies, increased risks of non-fatal respiratory outcomes were noted for children, seniors, women, and those with lower SES.

Equity-related considerations during wildfires

The results of this rapid review have highlighted some key health equity-related considerations related to wildfires and wildfire smoke that could be considered by those planning for and responding to these eventsFootnote e.

Interventions and policies could consider the benefit of:

- Increased access to effective and long-term mental health supports for communities affected by wildfires.Footnote 23Footnote 26Footnote 27

- Routine health assessments and adequate preventative measures (for example, supplying personally fitted respiratory protections) for those working in occupations regularly deployed during wildfires to monitor and mitigate health impacts.Footnote 68

- Evacuation procedures and activities tailored to the distinct needs and experiences of diverse populations. For example:

- Accessible materials for preparedness and response (for example, flyers and handouts) and availability of inclusive and low-barrier evacuation spaces.Footnote 67

- Consideration of privacy and space needs for families and for those who are breastfeeding.

- Considering the cultural needs of faith communities and Indigenous Peoples during evacuations and developing community-based plan that reflect this consideration such as the provision of culturally appropriate foods.

- Consultation with community members after severe wildfire events to inform future planning and response to wildfires in order to incorporate local knowledge, context, and lived experience.Footnote 40

- Relocating evacuees together to offer opportunities to strengthen cohesion, altruism, and support within the community.Footnote 80

Meaningful engagement with and co-developing or adapting existing wildfire prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery resources and activities alongside diverse populations/community groups:

- Financial support and other resources for outreach, education and prevention initiatives.Footnote 42

- Wildfire management and response that integrates Indigenous knowledges in partnership with diverse First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities.

- Increased involvement of Indigenous communities in wildfire response and recovery, is critical for restoring culturally significant food sources, plants, and other land-based ties.Footnote 81

Examine the value of mobile clinics, as they play a critical role in monitoring and promoting the health of people impacted by wildfires:

- Mobile clinics improve access to healthcare for underserved communities, people experiencing homelessness, and those without health insurance in rural and remote areas.Footnote 82

- Specifically, mobile clinics provide essential primary care services, as well as health education, mental health assessments, vaccinations, and screenings that would otherwise be missed when populations are displaced by climate disasters.Footnote 82

Limitations

While the present rapid review attempts to explore the impacts on diverse population groups in Canada, further evidence is necessary to gain a more robust understanding of the extent of the impacts of wildfires on diverse population groups living in Canada.

References

- Footnote a

-

Within the Government of Canada the Health Portfolio is comprised of Health Canada, the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board, and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency.

- Footnote b

-

Brown et al. (2021)'s study conflates sex and gender. The demographic survey posed the question, "What gender do you identify with?," but only provided options related to sex (for example female, male, prefer not to say).

- Footnote c

-

It must be noted that women are more socialized to disclose and seek mental health care.

- Footnote d

-

Resilience in this circumstance is described as one's capacity to overcome adverse life events through mindset, resourcefulness, and social supports.

- Footnote e

-

These measures/considerations have not been reviewed for their effectiveness by groups/people experiencing these inequitable impacts and are suggestions based on the findings of this rapid review.

- Footnote 1

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. Public health risk profile: Wildfires in Canada, 2023 [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/emergency-preparedness-response/rapid-risk-assessments-public-health-professionals/risk-profile-wildfires-2023/wildfire-risk-profile.pdf

- Footnote 2

-

Erni S, Wang X, Swystun T, Taylor SW, Parisien MA, Robinne FN, et al. Mapping wildfire hazard, vulnerability, and risk to Canadian communities. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024 Feb 1;101:104221.

- Footnote 3

-

Pausas JG, Keeley JE. Wildfires and global change. Front Ecol Environ. 2021;19(7):387–95.

- Footnote 4

-

Canada NR. Wildland fire and forest carbon: Understanding impacts of climate change [Internet]. Natural Resources Canada; 2022 [cited 2024 Jun 7]. Available from: https://natural-resources.canada.ca/home/wildland-fire-and-forest-carbon-understanding-impacts-climate-change/24800

- Footnote 5

-

Hanes CC, Wang X, Jain P, Parisien MA, Little JM, Flannigan MD. Fire-regime changes in Canada over the last half century. Can J For Res. 2019 Mar;49(3):256–69.

- Footnote 6

-

Bowman DMJS, Kolden CA, Abatzoglou JT, Johnston FH, van der Werf GR, Flannigan M. Vegetation fires in the Anthropocene. Nat Rev Earth Environ. 2020 Oct;1(10):500–15.

- Footnote 7

-

Kizer KW. Extreme Wildfires—A Growing Population Health and Planetary Problem. JAMA. 2020 Oct 27;324(16):1605–6.

- Footnote 8

-

Mertz E. Alberta declares early start to wildfire season due to warm and dry weather. [cited 2024 May 30]. Alberta declares early start to wildfire season due to warm and dry weather | Globalnews.ca. Available from: https://globalnews.ca/news/10306287/alberta-early-wildfire-season-100-firefighters/

- Footnote 9

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. The Chief Public Health Officer of Canada's Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2023 - Canada.ca [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 May 30]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/state-public-health-canada-2023/report.html

- Footnote 10

-

Rosenthal A, Stover E, Haar RJ. Health and social impacts of California wildfires and the deficiencies in current recovery resources: An exploratory qualitative study of systems-level issues. PLOS ONE. 2021 Mar 26;16(3):e0248617.

- Footnote 11

-

Public Health Agency of. The Chief Public Health Officer's Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2022: Mobilizing Public Health Action on Climate Change in Canada: [Internet]. Public Health Agency of Canada; 2022 Oct [cited 2024 May 31]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/state-public-health-canada-2022/report.html

- Footnote 12

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. TOWARD HEALTH EQUITY: A TOOL FOR DEVELOPING EQUITY-SENSITIVE PUBLIC HEALTH INTERVENTION. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada; 2022.

- Footnote 13

-

Women and Gender Equality Canada. What Is Gender-Based Analysis Plus? In: Module 3 – What Is Gender-Based Analysis Plus (GBA Plus)? Government of Canada; 2022.

- Footnote 14

-

Egyed, M., Blagden, P., Plummer, D., Makar, P., Matz, C., Flannigan, M., MacNeill, M., Lavigne, E., Ling, B., Lopez, D. V., Edwards, B., Pavlovic,, R., Racine, J., Raymond, P., Rittmaster, R., Wilson, A., & Xi, G. Air Quality. In: In P Berry & R Schnitter (Eds), Health of Canadians in a Changing Climate: Advancing our Knowledge for Action O [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada.; [cited 2024 May 31]. Available from: https://changingclimate.ca/health-in-a-changing-climate/chapter/5-0/

- Footnote 15

-

Finlay SE, Moffat A, Gazzard R, Baker D, Murray V. Health Impacts of Wildfires. PLoS Curr. 2012 Nov 2;4:e4f959951cce2c.

- Footnote 16

-

Wildfires in Canada: Toolkit for Public Health Authorities [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Jun 3]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/wildfires-canada-toolkit-public-health-authorities.html

- Footnote 17

-

Macfarlane R. Health Effects of Extreme Weather Events and Wildland Fires: A Yukon Perspective [Internet]. Office of the Chief Medical Officer of Health; 2020. Available from: https://emrlibrary.gov.yk.ca/hss/health-effects-of-extreme-weather-events-and-wildland-fires-a-yukon-perspective-2020.pdf

- Footnote 18

-

Angelo AS. Forged in Fire: Environmental Health Impacts of Wildfires | Environmental Health Sciences Center [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Jun 4]. Available from: https://environmentalhealth.ucdavis.edu/wildfires/environmental-health-impacts

- Footnote 19

-

Health Canada. Human Health Effects of Wildfire Smoke. His Majesty the King in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Health, 2024; 2024.

- Footnote 20

-

Hayes, K., Cunsolo, A., Augustinavicius, J., Stranberg, R., Clayton, S., Malik, M., Donaldson, S., Richards, G., Bedard, A., Archer, L., Munro, T., & Hilario, C., Berry P, Schnitter R. Mental Health and Well-Being, In P. Berry & R. Schnitter (Eds.), Health of Canadians in a changing climate: advancing our knowledge for action [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 May 31]. Available from: https://ostrnrcan-dostrncan.canada.ca/handle/1845/134215

- Footnote 21

-

Gosselin, P., Campagna, C., Demers-Bouffard, D., Qutob, S., & Flannigan, M. (2022). Natural Hazards. In P. Berry & R. Schnitter (Eds.), Health of, Canadians in a Changing Climate: Advancing our Knowledge for Action., O. Gosselin, P., Campagna, C., Demers-Bouffard, D., Qutob, S., & Flannigan,M, Berry P, Schnitter R. Natural Hazards. In: Health of Canadians in a Changing Climate: Advancing our Knowledge for Action [Internet]. Ottawa : Government of Canada.; 2022 [cited 2024 May 31]. Available from: https://ostrnrcan-dostrncan.canada.ca/handle/1845/134215

- Footnote 22

-

Agyapong VIO, Hrabok M, Juhas M, Omeje J, Denga E, Nwaka B, et al. Prevalence Rates and Predictors of Generalized Anxiety Disorder Symptoms in Residents of Fort McMurray Six Months After a Wildfire. Front Psychiatry. 2018 Jul 31;9:345.

- Footnote 23

-

Belleville G, Ouellet MC, Lebel J, Ghosh S, Morin CM, Bouchard S, et al. Psychological Symptoms Among Evacuees From the 2016 Fort McMurray Wildfires: A Population-Based Survey One Year Later. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Mar 7];9. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2021.655357

- Footnote 24

-

Belleville G, Ouellet MC, Morin CM. Post-Traumatic Stress among Evacuees from the 2016 Fort McMurray Wildfires: Exploration of Psychological and Sleep Symptoms Three Months after the Evacuation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 May 8;16(9):1604.

- Footnote 25

-

Moosavi S, Nwaka B, Akinjise I, Corbett SE, Chue P, Greenshaw AJ, et al. Mental Health Effects in Primary Care Patients 18 Months After a Major Wildfire in Fort McMurray: Risk Increased by Social Demographic Issues, Clinical Antecedents, and Degree of Fire Exposure. Front Psychiatry [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2024 Mar 7];10. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00683

- Footnote 26

-

Brown MRG, Agyapong V, Greenshaw AJ, Cribben I, Brett-MacLean P, Drolet J, et al. Significant PTSD and Other Mental Health Effects Present 18 Months After the Fort McMurray Wildfire: Findings From 3,070 Grades 7–12 Students. Front Psychiatry. 2019 Aug 30;10:623.

- Footnote 27

-

Brown MRG, Pazderka H, Agyapong VIO, Greenshaw AJ, Cribben I, Brett-MacLean P, et al. Mental Health Symptoms Unexpectedly Increased in Students Aged 11–19 Years During the 3.5 Years After the 2016 Fort McMurray Wildfire: Findings From 9,376 Survey Responses. Front Psychiatry [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Mar 7];12. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.676256

- Footnote 28

-

Canada NR. Canada's record-breaking wildfires in 2023: A fiery wake-up call [Internet]. Natural Resources Canada; 2023 [cited 2024 Jun 4]. Available from: https://natural-resources.canada.ca/simply-science/canadas-record-breaking-wildfires-2023-fiery-wake-call/25303

- Footnote 29

-

Home | Implications for Disaster Management and Mitigation: Understanding the Human Dimension of Wildfire [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 4]. Available from: https://ruralwildfire.ca/index.html

- Footnote 30

-

Maguet S. Public Health Responses to Wildfire Smoke Events [Internet]. British Columbia Centre for Disease Control and the National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health; 2018. Available from: https://ccnse.ca/sites/default/files/Responding%20to%20Wildfire%20Smoke%20Events%20EN.pdf

- Footnote 31

-

Kulig JC, Edge D, Smolenski S. Wildfire disasters: implications for rural nurses. Australas Emerg Nurs J AENJ. 2014 Aug;17(3):126–34.

- Footnote 32

-

Webber T, Berger N. Canadian wildfires hit Indigenous communities hard, threatening their land and culture. AP News [Internet]. 2023 Jul 19 [cited 2024 Mar 8]; Available from: https://apnews.com/article/canada-wildfire-indigenous-land-first-nations-impact-3faabbfadfe434d0bd9ecafb8770afce

- Footnote 33

-

Brockie J, Han S. Opinion: Environmental racism and Canada's wildfires. Canadian Geographic [Internet]. 2023 Aug 10 [cited 2024 Mar 8]; Available from: https://canadiangeographic.ca/articles/opinion-environmental-racism-and-canadas-wildfires/

- Footnote 34

-

Eisenman, David P., Kyaw, May M.T., Eclarino, Kristopher. Review of the Mental Health Effects of Wildfire Smoke, Solastalgia, and Non-Traditional Firefighters. UCLA Center for Healthy Climate Solutions, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, & Climate Resolve; 2021 Mar.

- Footnote 35

-

Government of Canada O of the AG of C. Report 8—Emergency Management in First Nations Communities—Indigenous Services Canada [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/att__e_44162.html#hd2d

- Footnote 36

-

Long JW, Lake FK, Goode RW. The importance of Indigenous cultural burning in forested regions of the Pacific West, USA. For Ecol Manag. 2021 Nov 15;500:119597.

- Footnote 37

-

Parks Canada Agency G of C. Indigenous fire stewardship - Indigenous fire stewardship [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Jun 4]. Available from: https://parks.canada.ca/nature/science/conservation/feu-fire/autochtones-indigenous

- Footnote 38

-

Howard C, Rose C, Dodd W, Kohle K, Scott C, Scott P, et al. SOS! Summer of Smoke: a retrospective cohort study examining the cardiorespiratory impacts of a severe and prolonged wildfire season in Canada's high subarctic. BMJ Open. 2021 Feb 1;11(2):e037029.

- Footnote 39

-

Fitzpatrick KM, Wild TC, Pritchard C, Azimi T, McGee T, Sperber J, et al. Health Systems Responsiveness in Addressing Indigenous Residents' Health and Mental Health Needs Following the 2016 Horse River Wildfire in Northern Alberta, Canada: Perspectives From Health Service Providers. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Mar 7];9. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2021.723613

- Footnote 40

-

Dodd W, Scott P, Howard C, Scott C, Rose C, Cunsolo A, et al. Lived experience of a record wildfire season in the Northwest Territories, Canada. Can J Public Health Rev Can Santé Publique. 2018 Jun;109(3):327–37.

- Footnote 41

-

Mihychuk M. From the ashes: reimagining fire safety and emergency management in Indigenous communities [Internet]. House of Commons Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs; 2018. Available from: https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/INAN/Reports/RP9990811/inanrp15/inanrp15-e.pdf

- Footnote 42

-

Christianson AC, McGee TK, Whitefish Lake First Nation 459. Wildfire evacuation experiences of band members of Whitefish Lake First Nation 459, Alberta, Canada. Nat Hazards. 2019 Aug 1;98(1):9–29.

- Footnote 43

-

Asfaw HW, McGee TK, Christianson AC. Indigenous Elders' Experiences, Vulnerabilities and Coping during Hazard Evacuation: The Case of the 2011 Sandy Lake First Nation Wildfire Evacuation. Soc Nat Resour. 2020 Oct 2;33(10):1273–91.

- Footnote 44

-

Venkataraman M, Grzybowski S, Sanderson D, Fischer J, Cherian A. Environmental racism in Canada. Can Fam Physician. 2022 Aug;68(8):567–9.

- Footnote 45

-

Schimmele C, Hou F, Stick M. Statistics Canada. 2023 [cited 2024 Mar 8]. Poverty among racialized groups across generations. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/36-28-0001/2023008/article/00002-eng.htm

- Footnote 46

-

Statistics Canada. The Daily — Housing conditions among racialized groups: A brief overview [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Mar 8]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/230123/dq230123b-eng.htm

- Footnote 47

-

MacDonald E. Environmental racism in Canada: What is it, what are the impacts, and what can we do about it? [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://ecojustice.ca/news/environmental-racism-in-canada/

- Footnote 48

-

Waldron I. Environmental Racism and Climate Change: Determinants of Health in Mi'kmaw and African Nova Scotian Communities [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://climateinstitute.ca/publications/environmental-racism-and-climate-change/

- Footnote 49

-

Binet É, Ouellet MC, Lebel J, Békés V, Morin CM, Bergeron N, et al. A Portrait of Mental Health Services Utilization and Perceived Barriers to Care in Men and Women Evacuated During the 2016 Fort McMurray Wildfires. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2021 Nov;48(6):1006–18.

- Footnote 50

-

Davies IP, Haugo RD, Robertson JC, Levin PS. The unequal vulnerability of communities of color to wildfire. PLOS ONE. 2018 Nov 2;13(11):e0205825.

- Footnote 51

-

Liu JC, Pereira G, Uhl SA, Bravo MA, Bell ML. A systematic review of the physical health impacts from non-occupational exposure to wildfire smoke. Environ Res. 2015 Jan;136:120–32.

- Footnote 52

-

Stone K, Blinn N, Spencer R. Mental Health Impacts of Climate Change on Women: a Scoping Review. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2022 Jun;9(2):228–43.

- Footnote 53

-

UN WomenWatch: Women, Gender Equality and Climate Change [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 13]. Available from: https://www.un.org/womenwatch/feature/climate_change/downloads/Women_and_Climate_Change_Factsheet.pdf

- Footnote 54

-

Chapter 9 — Health of Canadians in a Changing Climate [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 5]. Available from: https://changingclimate.ca/health-in-a-changing-climate/chapter/9-0/

- Footnote 55

-

Esther. Women's Centre of Calgary. 2023 [cited 2024 Jun 7]. Wildfires and Gender. Available from: https://www.womenscentrecalgary.org/wildfires-and-gender/

- Footnote 56

-

Alston M. Women and adaptation. WIREs Clim Change. 2013;4(5):351–8.

- Footnote 57

-

Cherry N, Haynes W. Effects of the Fort McMurray wildfires on the health of evacuated workers: follow-up of 2 cohorts. CMAJ Open. 2017 Aug 15;5(3):E638–45.

- Footnote 58

-

Ritchie A, Sautner B, Omege J, Denga E, Nwaka B, Akinjise I, et al. Long-Term Mental Health Effects of a Devastating Wildfire Are Amplified by Sociodemographic and Clinical Antecedents in College Students. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2021 Dec;15(6):707–17.

- Footnote 59

-

Zhu Q, Zhang D, Wang W, D'Souza RR, Zhang H, Yang B, et al. Wildfires are associated with increased emergency department visits for anxiety disorders in the western United States. Nat Ment Health. 2024 Apr;2(4):379–87.

- Footnote 60

-

Melton CC, De Fries CM, Smith RM, Mason LR. Wildfires and Older Adults: A Scoping Review of Impacts, Risks, and Interventions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Jun 29;20(13):6252.

- Footnote 61

-

Adu MK, Eboreime E, Shalaby R, Sapara A, Agyapong B, Obuobi-Donkor G, et al. Five Years after the Fort McMurray Wildfire: Prevalence and Correlates of Low Resilience. Behav Sci Basel Switz. 2022 Mar 30;12(4):96.

- Footnote 62

-

CMHA. Canadian Mental Health Association. 2017 [cited 2024 Mar 8]. Poverty and Mental Illness. Available from: https://ontario.cmha.ca/documents/poverty-and-mental-illness/

- Footnote 63

-

Taylor-Butts A. Statistics Canada. 2016 [cited 2024 Mar 8]. Emergency preparedness in Canada, 2014. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2015001/article/14234-eng.htm#a6

- Footnote 64

-

Statistics Canada SC. Housing conditions among First Nations people, Métis and Inuit in Canada from the 2021 Census [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Mar 8]. Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/as-sa/98-200-X/2021007/98-200-X2021007-eng.cfm

- Footnote 65

-

Austin S. Canada lacks data on how wildfire smoke affects minority communities, experts say [Internet]. The Narwhal. 2023 [cited 2024 Mar 8]. Available from: https://thenarwhal.ca/wildfire-smoke-health-impact-minority-communities/

- Footnote 66

-

Lowe SR, Garfin DR. Crisis in the air: the mental health implications of the 2023 Canadian wildfires. Lancet Planet Health. 2023 Sep 1;7(9):e732–3.

- Footnote 67

-

Rushton A, Mathias H. The Conversation. 2023 [cited 2024 Mar 8]. Wildfire preparedness and response must include planning for unhoused people and other vulnerable populations. Available from: http://theconversation.com/wildfire-preparedness-and-response-must-include-planning-for-unhoused-people-and-other-vulnerable-populations-206851

- Footnote 68

-

Miandashti N, Kamravaei S, Idrissi Machichi K, Khadour F, Henderson L, Naseem M t., et al. Extremely High-Risk Air Quality for Recruited RCMP Officers in 2016 Fort McMurray Wildfires: Is There a Health Impact from Short Periods of Intense Wildfire Smoke Exposure? In: C15 OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURES OF THE 21ST CENTURY [Internet]. American Thoracic Society; 2019 [cited 2024 Mar 7]. p. A4257–A4257. (American Thoracic Society International Conference Abstracts). Available from: https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2019.199.1_MeetingAbstracts.A4257

- Footnote 69

-

Cherry N, Barrie JR, Beach J, Galarneau JM, Mhonde T, Wong E. Respiratory Outcomes of Firefighter Exposures in the Fort McMurray Fire: A Cohort Study From Alberta Canada. J Occup Environ Med. 2021 Sep;63(9):779.

- Footnote 70

-

Swiston JR, Davidson W, Attridge S, Li GT, Brauer M, van Eeden SF. Wood smoke exposure induces a pulmonary and systemic inflammatory response in firefighters. Eur Respir J. 2008 Jul;32(1):129–38.

- Footnote 71

-

Cherry N, Galarneau JM, Melnyk A, Patten S. Prevalence of Mental Ill-Health in a Cohort of First Responders Attending the Fort McMurray Fire. Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatr. 2021 Aug;66(8):719–25.

- Footnote 72

-

To P, Eboreime E, Agyapong VIO. The Impact of Wildfires on Mental Health: A Scoping Review. Behav Sci Basel Switz. 2021 Sep 21;11(9):126.

- Footnote 73

-

Pujadas Botey A, Kulig JC. Family Functioning Following Wildfires: Recovering from the 2011 Slave Lake Fires. J Child Fam Stud. 2014 Nov 1;23(8):1471–83.

- Footnote 74

-

Pike A, Mikolas C, Tompkins K, Olson J, Olson DM, Brémault-Phillips S. New Life Through Disaster: A Thematic Analysis of Women's Experiences of Pregnancy and the 2016 Fort McMurray Wildfire. Front Public Health. 2022 May 13;10:725256.

- Footnote 75

-

DeYoung SE, Chase J, Branco MP, Park B. The Effect of Mass Evacuation on Infant Feeding: The Case of the 2016 Fort McMurray Wildfire. Matern Child Health J. 2018 Dec;22(12):1826–33.

- Footnote 76

-

Montesanti S, Fitzpatrick K, Azimi T, McGee T, Fayant B, Albert L. Exploring Indigenous Ways of Coping After a Wildfire Disaster in Northern Alberta, Canada. Qual Health Res. 2021 Jul;31(8):1472–85.

- Footnote 77

-

Malbeuf J. Evacuation centres could improve services for minorities during disasters, study finds. CBC News [Internet]. 2019 May 9 [cited 2024 Jun 5]; Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/fort-mcmurray-research-muslim-evacuation-1.5128104

- Footnote 78

-

Mamuji AA, Rozdilsky JL. Canada's 2016 Fort McMurray wildfire evacuation: experiences of the Muslim community. Int J Emerg Manag. 2019 Jan;15(2):125–46.

- Footnote 79

-

Matz CJ, Egyed M, Xi G, Racine J, Pavlovic R, Rittmaster R, et al. Health impact analysis of PM2.5 from wildfire smoke in Canada (2013-2015, 2017-2018). Sci Total Environ. 2020 Jul 10;725:138506.

- Footnote 80

-

NCCMT, NCCEH. Rapid Review: What is the effectiveness of public health interventions on reducing the direct and indirect health impacts of wildfires? [Internet]. National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools and The National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health; 2023. Available from: https://www.nccmt.ca/pdfs/res/wildfires

- Footnote 81

-

Kane A. World Wildlife Fund Canada. 2023 [cited 2024 Mar 8]. Here's why Indigenous-led wildfire restoration works. Available from: https://wwf.ca/stories/indigenous-led-wildfire-restoration/

- Footnote 82

-

Oseh C. How mobile clinics are helping those affected by Canada's wildfires. BMJ. 2023 Sep 25;382:p2007.