Public Services and Procurement Canada

Evaluation of the Fairness Monitoring Program

On this page

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Background

- Authority

- Roles and responsibilities

- Resources

- Focus of the evaluation

- Findings and conclusions

- Relevance

- Conclusions: Relevance

- Performance

- Conclusions: Performance

- Efficiency and economy

- Conclusions: Efficiency and economy

- Management response

- Recommendations and management action plan

- Appendix A: Program activities

- Appendix B: Logic model

- Appendix C: About the evaluation

Executive summary

Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) is committed to excelling in government operations and ensuring sound stewardship on behalf of Canadians by delivering high-quality services and programs that meet the needs of federal organizations. The Fairness Monitoring Program (FMP) was created as a formal oversight mechanism to provide management, suppliers, clients and Canadians with independent assurance that departmental activities such as the procurement of goods, services or construction services, acquisition and disposal of real property, disposal of Crown assets, and grants and contributions are conducted in a fair, open and transparent manner.

This evaluation examined the relevance, performance and the efficiency and economy of the FMP.

The program's total expenditures in fiscal year 2017 to 2018 were $1.93 million with 5.5 full time equivalents. The FMP is delivered by the Fairness Monitoring and Business Dispute Directorate within the Departmental Oversight Branch (DOB).

The FMP is relevant in that it ensures perceived and actual fairness in the procurement process. In this way, it provides an additional level of assurance to bidders and to the public that procurements are being carried out in a fair, open and transparent manner. While there is no legislative or regulatory requirement for the program, there is a PSPC Policy on Fairness Monitoring which supports PSPC's strategic outcomes as well as the goal of promoting open, fair and transparent procurement practices, as reflected in the minister's Mandate Letter commitments, the Speech from the Throne and the Financial Administrative Act.

The current Policy on Fairness Monitoring is the driver for fairness monitoring engagements. The number of mandatory assessments processed to determine if fairness monitoring is required has remained stable over time. While the number of optional assessments processed (where an assessment for fairness monitoring was not required but a program request was made) has also remained somewhat stable, the numbers are very small in comparison to the number of mandatory assessments processed. The number of issues resolved throughout the procurement process involving a fairness monitor is a more robust measure of continued need. Since 2009, at least 300 fairness issues were identified in summary reports and corrected throughout the procurement process. Whereas, there were 8 qualified reports of fairness deficiencies identified during the same period.

The program is, for the most part, achieving its intended immediate and intermediate outcomes. By ensuring that fairness monitoring is carried out when warranted and in an effective manner, the program contributes to fair, open and transparent PSPC procurements. By contributing to the probity and integrity of procurement activities, the FMP supports sound stewardship on behalf of Canadians in addition to meeting the program needs of federal institutions. However, greater clarity on the criteria for assessing the requirement for fairness monitoring for non-Treasury Board procurements would increase program effectiveness.

There was also consensus among those interviewed that fairness is more perceived than actual. However, perception of fairness in and of itself is very important as the program's existence provides an additional level of assurance to bidders and to the public that procurements are being carried out in a fair, open and transparent manner.

There has been some sharing of lessons learned from fairness monitoring to improve procurement practices within PSPC. These appear to have had limited impacts in terms of changes to procurement guidelines or policies, in part because fairness issues identified in the course of fairness monitoring engagements are not being systematically reviewed from the perspective of their implications for needed changes to policies or guidelines.

The program is operating efficiently and economically. The cost of fairness monitoring relative to the value of monitored procurements is negligible (.01%). This cost is recovered by clients. Fairness monitoring engagements have remained steady over the last 4 years while internal program costs per fairness monitoring engagement have declined, mainly due to staffing vacancies. At the same time, the costs of contracted fairness monitors have increased. While the program is operating at a low cost, it has a large mandate which it is meeting, as the existence of the program has resulted in a high perception of fairness in procurements.

Management response

Management from DOB has had the opportunity to review the evaluation report and accept the conclusions and recommendations as part of our commitment to continuous improvement. A management action plan containing proposed measures to improve the performance and efficiency of our program activities was developed.

Acquisitions Program views this as an important opportunity to address lessons learned and improve operations.

Recommendations and management action plan

Recommendation 1

The Assistant Deputy Minister (ADM), Departmental Oversight Branch should implement changes currently being considered to the Policy on Fairness Monitoring to ensure that all high-risk, high-sensitivity, high complexity procurements are assessed for monitoring needs whether or not they require ministerial or Treasury Board approval.

Management action plan 1

The Fairness Monitoring Directorate will:

- update the Fairness Monitoring Policy to clearly communicate the criteria for mandatory assessment for fairness monitoring coverage (sensitivity and complexity). This includes, ensuring that procurements with high complexity and/or high sensitivity identified through the Project Complexity and Risk Assessment Tool and the procurement risk assessment process triggers the completion of a fairness monitoring coverage assessment and recommendation form for procurements

- revise fairness monitoring intranet pages to reflect the updated Fairness Monitoring Policy

- promote awareness of the Fairness Monitoring Policy to the procurement community within Public Services and Procurement Canada

Recommendation 2

The ADM, Departmental Oversight Branch should take steps to ensure that lessons learned are based on an analysis of all fairness issues identified in the course of monitoring; and that reviews of lessons learned are carried out on a regular basis. In addition, the lessons learned should be shared on a regular basis with Defence and Marine Procurement and Acquisitions, to inform changes to relevant policies, guidelines, procurement manuals and tools.

Management action plan 2

The Fairness Monitoring Directorate will:

- systemize the collection of lessons learned identified by fairness monitors

- prepare quarterly assessments of lessons learned

- share lessons learned:

- at kick-off meetings that are conducted at the beginning of every fairness monitoring activity

- with senior management at the end of each project

- with procurement specialists during awareness sessions

Recommendation 3

The ADMs of Defence and Marine Procurement and Acquisitions should ensure that policies, guidelines and procurement manuals, in addition to the design of procurement tools supporting them, be regularly reviewed and updated, as warranted based on any systemic fairness issues identified through the FMP's analysis of lessons learned.

Management action plan 3

The Acquisitions Program will develop an engagement mechanism between Acquisitions Program and the Fairness Monitoring and Business Dispute Management Directorate to ensure that evaluation observations and systemic fairness issues are being identified and addressed in policy instruments and operationally on a regular basis if, and, as required.

Introduction

This report presents the results of the evaluation of the Fairness Monitoring Program (FMP). This engagement was included in the Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) 2018 to 2021 Risk-Based Audit and Evaluation Plan.

Background

The FMP was created in 2005 to provide management, client departments, government suppliers, Parliament and Canadians with independent assurance that PSPC's large or complex procurement activities were conducted in a fair, open and transparent manner. In 2009, the departmental Policy on Fairness Monitoring was established. It set out the roles and responsibilities for stakeholders, and expanded the scope of the program to apply to all departmental activities (such as, procurement of goods, services or construction services, acquisition and disposal of real property, disposal of Crown assets, and grants and contributions). In 2012, the policy was revised to introduce explicit definitions of fairness, openness and transparency; to clarify the roles and responsibilities for conducting assessments and responding to fairness issues; and to create risk-based criteria for departmental activities to determine if a mandatory assessment is required.

The FMP engages independent third-party fairness monitors to observe all or part of a departmental procurement activity in order to provide an impartial opinion on the fairness, openness and transparency of the activity and to identify issues that, if not addressed, could lead to reports of fairness deficiencies in the monitored activity and become costly to resolve post-procurement process.

In addition to conducting fairness monitoring with respect to PSPC acquisition, leasing and disposal activities, the FMP also provides fairness monitoring services to 3 other federal government organizations (Shared Services Canada, the Canadian Revenue Agency, and the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission) under memoranda of understanding.

Authority

The Public Works and Government Services Act (Section 7.(1)(a)) authorizes the Minister of Public Works and Government Services to, among other things, investigate and develop services for enhancing integrity and efficiency in the contracting process. Section 15 of the act states that the minister may, on request of a department, board or agency of the Government of Canada, provide it with services of any other kind that are within the ambit of the minister's powers, duties, and functions.

There is no government-wide policy on fairness monitoring. However, there is a departmental Policy on Fairness Monitoring, under which an assessment of the need for fairness monitoring is mandatory for all procurements requiring ministerial or Treasury Board approval or where standard branch-level risk instruments indicate that a fairness monitoring coverage assessment and recommendation form is required to be completed. Based on their review of this form, FMP officials will make a recommendation to the deputy minister as to whether or not monitoring is warranted.

PSPC program branches may also request fairness monitoring on an optional basis where an enhanced level of assurance of fairness, openness and transparency is desired.

Roles and responsibilities

Fairness Monitoring and Business Dispute Management Directorate within the Departmental Oversight Branch is responsible for:

- overseeing fairness monitoring engagements, establishing and managing fairness monitoring contracts; providing advice and support to clients; facilitating resolution of potential fairness deficiencies; briefing senior management on fairness monitoring engagements; and managing the publishing of fairness monitoring reports

- providing policy and support services which include maintaining the Fairness Monitoring Policy; providing advice and guidance to clients; briefing senior management on recommended fairness monitoring coverage; compiling lessons learned documents; and delivering awareness/outreach and lessons learned sessions to senior management and client groups (more information is provided in Appendix A: Program activities)

- Fairness Monitors

- Private sector contractors to the FMP provide fairness monitoring services for departmental activities. They are responsible for providing unbiased and impartial opinions on the fairness, openness and transparency of observed activities throughout the procurement process. The fairness monitors may also identify issues that, if not addressed, could lead to the identification of fairness deficiencies in a final fairness monitoring report that is publicly reported. Fairness deficiencies that are not resolved with the contracting authority or through the program's escalation process result in a "qualified" report.

- Direct clients

- Direct clients include contracting authorities in PSPC branches and regions that manage procurements or other departmental activities subject to fairness monitoring or in other government departments (OGDs) that have a memoranda of understanding with the program. The contracting authority is responsible for cooperating with the fairness monitors and providing them with all information, documents and facts related to each stage of the procurement process in a timely manner as well as taking into consideration all fairness-related questions and concerns raised by the fairness monitors and addressing any perceived fairness deficiencies.

- Indirect clients

- Indirect clients include project or technical authorities within PSPC or in OGDs that have initiated procurements subject to fairness monitoring, either because PSPC is managing the procurement or because another department has requested monitoring under a memoranda of understanding with the FMP. The project or technical authority is responsible for co-operating with the contract authority to provide the fairness monitors with information, documents and facts in a timely manner.

Resources

Total expenditures in the 2017 to 2018 fiscal year amounted to $1.93 million; however, this was partially offset by $1.12 million in costs, recovered from PSPC branches and regions and other client departments, for the direct services provided by contracted fairness monitors. It also includes $0.167 million recovered through an internal reallocation of funds from the Real Property Branch and the Parliamentary Precinct Branch. The remainder of the expenditures are funded from departmental appropriations managed by the Departmental Oversight Branch.

The number of full-time equivalents allocated to the FMP was 5.5 in the 2017 to 2018 fiscal year.

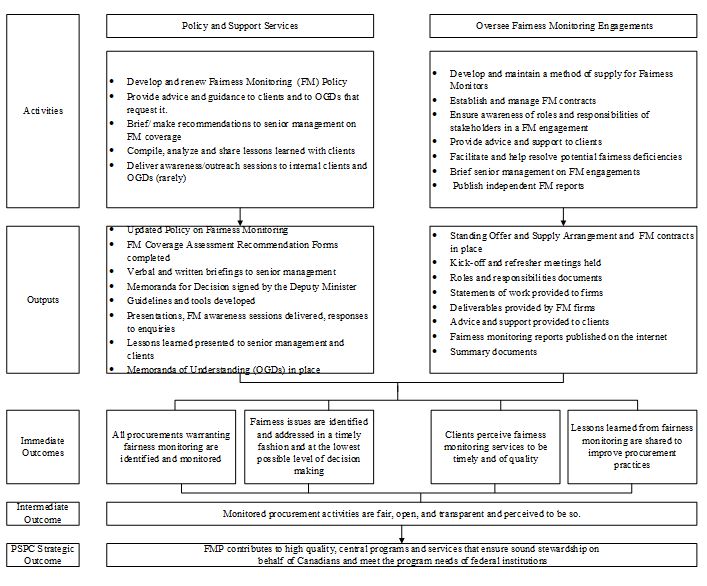

Logic model

A logic model is a visual representation that links a program's activities, outputs and outcomes; provides a systematic and visual method of illustrating the program theory; and shows the logic of how a program is expected to achieve its objectives. A logic model for the program was developed based on a detailed document review, meetings with program managers and interviews with key stakeholders. It was subsequently validated with program staff. The logic model is in Appendix B: Logic model.

Focus of the evaluation

The objective of this evaluation was to determine the program's relevance and performance in achieving its expected outcomes in accordance with the Treasury Board Policy on Results. The evaluation assessed the program for the period from April 2013 to March 2018.

Approach and methodology

Multiple lines of evidence were used to assess the program. These included:

- a review of program, departmental, federal government documents

- a review and analysis of a variety of program financial, activity, output and data, as well as client satisfaction data, departmental procurement data and other data

- a comparative review of provincial government fairness monitoring programs

- interviews: 22 interviews were conducted: 14 with senior managers of PSPC and OGDs who have been direct or indirect clients of the program; 3 with program officials, 4 with comparator organizations, and 1 with officials of Legal Services to PSPC

- survey: A survey was distributed to 43 past clients of the program (for example, contracting authorities who managed procurements that had been monitored by the program) and 27 individuals responded to the survey

More information regarding the approach and methodologies, including limitations of the methodologies, can be found in Appendix C: About the evaluation.

Findings and conclusions

The findings and conclusions below are based on multiple lines of evidence used during the evaluation. They are presented by evaluation issue (relevance and performance).

Relevance

To evaluate the program's relevance, the evaluation examined the FMP's alignment with current federal government and departmental priorities; the legislative, regulatory or policy requirement for the program; and the continued need for the program.

Alignment with the priorities of the federal government and Public Services and Procurement Canada

PSPC's strategic outcome is to deliver high-quality, central programs and services that ensure sound stewardship on behalf of Canadians and meet the program needs of federal institutions.

All of the program officials agreed that FMP objectives are aligned with PSPC's strategic outcome while only 3 of 7 senior-level clients believed this. The 4 senior-level clients who disagreed did so for a variety of reasons, including the observation that if sound stewardship means greening of government operations, diversity etc. then fairness monitoring is not really relevant; and the point that sound stewardship is the responsibility of public servants, not of private sector fairness monitors.

In support of the strategic outcome, PSPC has identified 4 procurement related priorities:

- modernize procurement practices

- ensure the Canadian Armed Forces and the Canadian Coast Guard get the equipment they need on time and on budget

- ensure the procurement processes reflect modern best practices

- deliver procurement practices that reflect public expectations around transparent, open, and citizen-centred government

To evaluate the FMP's alignment with the above priorities, the evaluation team conducted interviews with 8 senior PSPC executives who are direct clients of the program. Seven of the eight direct clients responded to the questions on alignment. Three program officials were also asked these questions.

With the exception of priority ii, above, all of the program officials interviewed thought that the FMP was aligned with all of these priorities. Clients, however, were more diverse in their views. Of the 7 direct clients who responded to the question on this:

- all agreed that the FMP is wholly or partially aligned with the priority to deliver procurement practices that reflect public expectations around transparent, open, and citizen-centred government

- only 1 agreed that the program is aligned with the priority to modernize procurement practices and only 2 that the program is aligned wholly or partially with the priority to ensure that procurement processes reflect modern best practices

- none agreed that the program is aligned with priority ii (ensure the Canadian Armed Forces and the Canadian Coast Guard get the equipment they need on time and on budget)

The evaluation team reviewed the program objective and the program's intended outcome to assess alignment with the above priorities and with PSPC's strategic outcome.

The objective of the FMP is to provide management, client departments, government suppliers, Parliament and Canadians with independent assurance that PSPC's large or complex procurement activities are conducted in a fair, open and transparent manner.

Fairness monitoring has a relatively narrow focus on the fairness of procurement. It does not directly support priority ii, which is focused on meeting the needs of 2 of PSPC's most important procurement partners, on time and on budget. Nor does it necessarily support modernization of procurement or best practices, except insofar as these are aimed at improving fairness. It does, however, provide assurances that procurements are meeting expectations of bidders, senior management, the government and the public with respect to fairness, openness and transparency. In doing this it is most closely aligned with priority iv, "to deliver procurement practices that reflect public expectations around transparent, open, and citizen-centred government."

In conclusion, the FMP is aligned with the priority to deliver procurement practices that meet public expectations around transparent, open and citizen-centred government. As well, it is aligned with PSPC's strategic outcome of sound stewardship, while meeting the needs of federal institutions.

Legislative, regulatory or policy requirement

To assess whether there is a legislative, regulatory and/or policy requirement for FMP the evaluation team reviewed federal and departmental documents.

The Department of Public Works and Government Services Act Section 7. (1)(a) states that the minister may "… investigate and develop services for increasing the efficiency and economy of the federal public administration and for enhancing integrity and efficiency in the contracting process."

Section 40.1 of the Financial Administration Act (FAA) sets out the Government of Canada's commitment "to [take] appropriate measures to promote fairness, openness and transparency in the bidding process for contracts with Her Majesty for the performance of work, the supply of goods or the rendering of services."

The departmental Policy on Fairness Monitoring applies to all program activities undertaken by PSPC, whether conducted on behalf of internal or external clients. Fairness monitoring is not identified in the policy as a mandatory activity. However, branch heads are required to complete and submit a fairness monitoring coverage assessment and recommendation form for activities where there is risk related to sensitivity, materiality or complexity and for all other departmental activities subject to ministerial or Treasury Board approval.

The 2015 Speech from the Throne stated that "the government is committed to open and transparent government". The minister's Mandate Letter announced that "the delivery of government services, including procurement practices, should reflect public expectations around transparent, open, and citizen-centred government".

In summary, there is not a legislative or regulatory requirement for the program, nor is there a government-wide policy on fairness monitoring. However, the FMP is a measure PSPC has implemented in support of fulfilling the commitment in the FAA to promote open, fair and transparent procurement practices. It is also required under the departmental Policy on Fairness Monitoring, which assigns the deputy minister responsibility for implementing a Fairness Monitoring Program.

Continuing need

Continuing need assesses the extent to which the FMP addresses and is responsive to a demonstrable need. To evaluate the continuing need of the FMP, we looked at the demand for services over the last 5 years, based on program output data. We also reviewed data on the number of fairness issues identified by FMs and the number of their final reports that were "qualified", which indicates identified fairness deficiencies during the procurement process were not resolved. As well, we obtained the views of program stakeholders as to the possible impacts if there were no FMP and regarding alternative approaches to ensuring fairness, openness and transparency in procurements.

To assess the continued demand for services, we reviewed program output data for 2013 to 2014 to 2017 to 2018 fiscal years. Table 1, below, summarizes the results of this review.

| New/ongoing/active fairness monitoring engagements | 2013 to 2014 | 2014 to 2015 | 2015 to 2016 | 2016 to 2017 | 2017 to 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of new fairness monitoring engagements | 47 | 26 | 23 | 25 | 30 |

| Number of ongoing (pro-rated) fairness monitoring engagementstable 1 note 1 | 29 | 48 | 58 | 55 | 55 |

| Total number of active fairness monitoring engagements | 76 | 74 | 81 | 80 | 85 |

Table 1: Volume of fairness monitoring engagements from 2013 to 2014 through 2017 to 2018 fiscal years: Table 1 Notes

|

|||||

As can be seen in table 1, new engagements declined from 47 in 2013 to 2014 fiscal year to 26 in 2014 to 2015 fiscal year and have remained stable since, ranging from 23 in 2015 to 2016 fiscal year to 30 in 2017 to 2018 fiscal years. Ongoing engagements carried over from previous years, increased from 29 in 2013 to 2014 fiscal year to 48 in 2014 to 2015 fiscal year, and have also remained stable, ranging from 58 in 2015 to 2016 fiscal year to 55 in the following 2 fiscal years.

Fairness monitoring is normally carried out based on a mandatory assessment of the need for fairness monitoring, either because the procurement required ministerial or Treasury Board approval or because standard branch-level risk instruments indicated that a fairness monitoring coverage assessment and recommendation form was required to be completed. Clients in other branches, regions and OGDs may, however, request fairness monitoring on an optional basis for their project.

Table 2 provides a breakdown of the number of new engagements in 2016 to 2017 and 2017 to 2018 fiscal years that were based on a review of fairness monitoring coverage assessment and recommendation forms submitted and where it was determined monitoring was warranted. The vast majority of new fairness monitoring engagements in these years were based on mandatory assessments, indicating that the current policy is the driver for fairness monitoring engagements.

| Fiscal years | Mandatory | Optional | Total fairness monitoring engagements | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treasury Board approval | Based on risk | Both Treasury Board approval and risk | Total mandatory | Optional: PSPC | Optional: Other government departments | Total optional | ||

| 2016 to 2017 | 11 | 5 | 3 | 19 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 26table 2 note 1 |

| 2017 to 2018 | 13 | 3 | 11 | 27 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 30 |

| Overall | 24 | 8 | 14 | 46 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 56 |

Table 2: New mandatory and optional fairness monitoring engagements in the 2016 to 2017 and 2017 to 2018 fiscal years: Table 2 Notes

|

||||||||

As table 2 also shows, the volume of optional fairness monitoring engagements has been low relative to the volume of mandatory engagements, indicating that while there is a continued need to address these requirements, the need is not great.

Senior-level managers from within PSPC (procurement executives and indirect clients) and from OGDs (clients of PSPC's procurement services) were asked several questions bearing on the continued need for the FMP. Their responses indicate that the program is needed more to provide assurances to bidders and the public regarding the fairness of procurements than to ensure the actual fairness. The majority of direct clients and indirect clients are of the view that fairness monitoring contributes more to the perception of fairness (8 of 14 respondents) than to the actual fairness (5 of 14 respondents).

Ten of fifteen direct and indirect clients interviewed indicated that there would be negative impacts if the FMP did not exist, affecting the perception of fairness of procurements more so than the actual fairness. Three individuals indicated there would be no impacts and one individual indicated there would be positive impacts in the form of financial savings and greater productivity.

Direct and indirect clients as well as Legal Services were asked whether there were any alternatives to the FMP for ensuring the fairness, openness and transparency of procurements. Seven of fifteen indicated that procurement teams could carry out this role themselves and 3 felt that technical authorities could be used in this role. Two stakeholders indicated that training would be required for procurement officers or technical authorities exercising the fairness monitoring role.

Direct clients and Legal Services were asked in interviews whether the FMP complemented, overlapped with or duplicated other programs. Of these 9, 3 indicated that it was complementary to the procurement function or to other oversight functions, such as independent procurement review by contracted consultants, audit and evaluation. Of the other 6 respondents, another 3 direct clients felt that it exercised a role that properly belongs to procurement and 3 felt that there was no overlap or duplication.

A more robust measure of continued need is the number of fairness issues identified over the course of monitoring.

Program data indicates that the number of qualified final reports by fairness monitors has been small. Only 8 engagements of some 200 since 2009 resulted in qualified reports.

This could suggest that, at least large, complex or high-risk procurements of PSPC are being conducted in a fair, open and transparent manner and that there is not a great need for fairness monitoring. However, fairness monitors sometimes reference in their reports fairness issues that have been resolved during the procurement. Program officials recently conducted a review of some 200 summary reports and identified 300 observations noted in these reports that were resolved during the procurement process.

It is highly likely that the actual number of fairness issues identified and resolved was considerably higher, as the above number includes only those mentioned in summary reports. The fact that fairness monitors identified at least 300 fairness issues in summary reports in the course of these engagements suggests that fairness issues are occurring with some frequency and that the FMP is playing a role in their early identification and resolution.

There is therefore a continuing need for the FMP. The Policy on Fairness Monitoring is the driver of the program, as the number of mandatory assessments has not increased over time while the number of optional assessments has remained low. However, while there were only 8 final reports of fairness deficiencies since 2009, at least 300 fairness issues were identified in summary reports and corrected throughout the procurement process during the same period. The number of issues in this category could be a more robust measure of continued need. The consensus from the interviews was there is a strong perception of fairness as opposed to actual fairness resulting from fairness monitoring, but that it also provides an additional level of assurance to bidders and to the public that procurements are being carried out in a fair, open and transparent manner.

Conclusion: Relevance

The FMP is relevant as it supports PSPC's strategic outcome of sound stewardship. While there is no legislative or regulatory requirement for the program, it is aligned with the minister's Mandate Letter commitment to ensure procurement practices reflect public expectations around transparent and open government. It is also in line with the Speech from the Throne which states that, "the government is committed to open and transparent government". It supports the Federal Accountability Act to promote open, fair and transparent procurement practices. It also supports the perception of fairness in the procurement process and allows for issues to be identified and resolved in real time before they potentially become deficiencies.

Performance

Performance is the extent to which a program is successful in achieving its intended outcomes and the degree to which it is able to do so in a cost-effective manner that demonstrates efficiency and economy. The evaluation examined both of these aspects of performance. The intended outcomes of the program are identified below, followed by an assessment of the extent to which they have been achieved.

Immediate outcome 1

All procurements warranting fairness monitoring are identified and monitored.

This outcome was evaluated through interviews with program officials and with PSPC senior managers who are clients of the program. In addition, the evaluation team cross-referenced the population of contracts awarded in the fiscal years 2016 to 2017 and 2017 to 2018 that required Treasury Board approval, with program data on monitored procurements.

As noted earlier in this report, fairness monitoring coverage assessment and recommendation forms must be completed for all departmental activities requiring ministerial or Treasury Board approval.

In addition to departmental activities requiring ministerial or Treasury Board approval, there are also other procurements that require monitoring based on risk related to sensitivity, materiality, or complexity. The risk ratings are determined by standard branch-level risk instruments whose results will indicate whether or not a fairness monitoring coverage assessment and recommendation form is required.

Almost all of the PSPC senior-level clients who responded to an interview question on this subject indicated that their processes assure that a fairness monitoring coverage assessment and recommendation form is completed.

Our analysis of contracts awarded between the fiscal years 2016 to 2017 and 2017 to 2018 as seen in table 3 supports the views of the senior-level clients interviewed, at least with respect to procurements that required Treasury Board approval. Twenty-one procurements requiring Treasury Board approval were awarded in this period with a total value of $6,257,106,006.Footnote 1 Of these, we were able to confirm that fairness monitoring coverage assessment and recommendation forms had been completed for 21, or 100% of procurements, all of which were monitored.Footnote 2

| Procurements | 2016 to 2017 | 2017 to 2018 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treasury Board procurements | 12 | 9 | 21 |

| Number of procurements monitored | 12 | 9 | 21 |

| Percentage of procurements monitored | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Based on a review of program output data, all procurements for which monitoring is recommended by the program are monitored as indicated in table 4. For example, in fiscal year 2016 to 2017, fairness monitoring coverage assessment and recommendation forms were submitted for 32 procurements. Monitoring was deemed to be warranted in 26 of these cases and 24 of these were monitored. In the other 2 cases, the procurement was cancelled. Similarly, in the 2017 to 2018 fiscal year, 30 procurements were monitored out of 30 fairness monitoring coverage assessment and recommendation forms submitted where monitoring was recommended.

| Forms and engagements | 2016 to 2017 | 2017 to 2018 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of forms submitted | 32 | 38 | 70 |

| Number of forms submitted where monitoring was not warranted | 6 | 8 | 14 |

| Number of forms submitted where monitoring was warranted | 26 | 30 | 56 |

| Number of fairness monitoring engagements | 26 | 30 | 56 |

Based on discussions with program officials, projects recommended for monitoring by the contracting authority may not be subject to fairness monitoring if they just marginally meet the Treasury Board approval threshold; the sensitivity and complexity is low; and they were not the subject of a special request. Consequently, fairness monitoring was not warranted for 6 of the fairness monitoring coverage assessment and recommendation forms submitted in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year and for 8 submitted in the 2017 to 2018 fiscal year.

The above data shows that all procurements requiring ministerial or Treasury Board approval are monitored. However, program officials are concerned that the current policy may not be sufficiently precise with respect to when the fairness monitoring coverage assessment and recommendation form should be completed in the context of risk. This could introduce a degree of subjectivity into decisions by the contracting authority as to whether to complete the form.

As a result, program officials are considering revisions to the policy that will require the completion of the fairness monitoring coverage assessment and recommendation form for all major Crown projects and for all projects rated at level 4 or 5 for risk or complexity, based on standard branch risk assessments. The revised policy would also require a fairness monitoring coverage assessment recommendation form for some specific categories of goods or services that, based on past experience, are high risk.

Based on the above, it would appear that most, but not all procurements warranting monitoring based on the criteria in the current policy are being monitored. However, it is not clear that the wording of the current policy is sufficiently precise to ensure that all high-risk, high-complexity or high sensitivity procurements are being assessed for monitoring. Consequently, the program is considering recommending changes to the policy.

Immediate outcome 2

Fairness issues are identified and addressed in a timely fashion and at the lowest possible level of decision making.

This outcome was evaluated through the survey of contracting authorities who were past clients of the program; through interviews with program officials and senior-level clients in the procurement area and in program areas whose procurements have been subject to monitoring; and through a review of program data on fairness issues, in particular, those resulting in qualified reports.

A large majority (88% of 25 responses) of the contracting authorities surveyed said that fairness issues were not identified with respect to their procurements by the fairness monitors. In contrast, 57% of 14 senior-level clients interviewed said issues have been identified on procurements in their area.Footnote 3 The latter group also indicated that identified issues were resolved almost always with minimal escalation.

As noted in the section on continued need, since 2009, over 300 fairness issues were identified in summary reports and resolved in the course of some 200 procurements being monitored. However, only 8 qualified final reports resulted from the 200 engagements. This suggests that the escalation process is working.

It therefore would appear that the vast majority of fairness issues identified by fairness monitors are resolved in real time during the procurement, either between the fairness monitor and the contracting authority or through the escalation process.

Immediate outcome 3

Clients perceive fairness monitoring services to be timely and of quality.

This outcome was evaluated through the survey of direct clients (such as contracting authorities) and through interviews with program officials and senior-level PSPC clients. The evaluation also made use of data obtained from the FMP client satisfaction survey administered by the program to new clients in fiscal year 2017 to 2018.

According to the client survey conducted by the evaluation team, 68% of contracting authorities said that they were satisfied with the quality of services provided by the fairness monitor on their particular procurement(s). In addition, 85% of the senior-level clients interviewed were satisfied with the quality of service provided by the FMP.

Despite these quite positive satisfaction ratings, both client groups were critical of some fairness monitors, based on their specific experiences.

For example, 3 out of 7 senior-level clients interviewed indicated that, at times, observations of the fairness monitor were not reasonable. Two senior-level clients commented on the time spent explaining issues to the fairness monitor so that they understood the project. Another senior manager commented on fairness monitors' lack of French language capacity.

Thirteen out of fourteen senior-level clients who responded to an interview question on the timeliness and quality of fairness monitoring services said that they were satisfied with the services provided by FMP staff.

The FMP conducted a client satisfaction survey for new clients in 2017 to 2018. One of the questions was whether "Staff responded to my questions/concerns in a timely manner." 89% of clients surveyed agreed with this statement. Timeliness of the FMP services was not an issue.

Based on the above, it appears that clients are generally satisfied with the overall quality and timeliness of the FMP. In a few specific cases, clients were not completely satisfied with the reasonableness of fairness observations or with the fairness monitors' understanding of the project.

Immediate outcome 4

Lessons learned from fairness monitoring are shared to improve procurement practices.

To evaluate this outcome, we reviewed program documents and data, and obtained information from program officials on lessons learned. In our interviews with FMP officials and senior-level PSPC direct and indirect clients, we asked them about the impact of fairness monitoring on procurement guidelines and processes. We included a similar question in our survey of PSPC contracting authorities who had been program clients.

We asked FMP officials how often these or other lessons learned activities had been presented to contracting authorities or others in procurement and to program areas that initiate procurements, especially those of high risk or those requiring ministerial or Treasury Board approval. Program officials indicated that, in one sense, they conduct lessons learned on a continuous basis with procurement teams, based on the fairness issues identified by the fairness monitor on their individual procurements.

In terms of more formal lessons learned initiatives and based on data provided by the program, the program carried out 11 awareness sessions that included a high-level summary of lessons learned with PSPC clients in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year, and 3 in the 2017 to 2018 fiscal year. The total number of participants at these sessions was 158 in 2016 to 2017 and 120 in 2017 to 2018 fiscal years.

The lessons learned identified in these presentations were based on a comprehensive review of 200 final reports on fairness monitoring engagements carried out since 2009. Based on this review, FMP staff grouped at least 300 potential fairness issues that were resolved during the procurement process under a number of common themes. Lessons learned included:

- engage industry early for a successful procurement

- manage incumbent contractor issues effectively to enhance fairness

- communicate with bidders in a well-structured and consistent manner

- rushing to post procurement documentation is counterproductive

- offering debriefings to all bidders—especially unsuccessful ones—is a best practice

We also asked FMP officials and senior-level PSPC clients of the program whether they were aware of any changes to procurement guidelines or processes as a result of fairness issues identified by fairness monitors in the last 5 years. We asked the same question of contracting authorities in our survey; however, only 1 individual responded to this question.

While none of the senior-level clients could identify any changes, FMP officials indicated that there was a change to the Supply Manual requiring debriefings of all bidders following a cancelled solicitation and that there have been changes to the wording of several clauses in the Standard Acquisition Clauses and Conditions Manual. Overall, however, it would appear that there have been very few changes to PSPC procurement policies, guidelines or practices, as a result of fairness monitoring.

One reason may be that the comprehensive lessons learned review carried out by the program was a one-time exercise, according to program officials. The FMP does not conduct lessons learned reviews on a regular basis.

Another reason may be that the review referred to above does not appear to have examined whether the lessons learned involve systemic issues that suggest the need to revise current policies or guidelines or whether to develop new guidelines or policies. Moreover, program officials indicated that they have not systematically reviewed and analyzed fairness issues through the lens of their implications for changes to guidelines or policies.

In conclusion, the FMP has partially achieved this intended outcome. There has been some sharing of lessons learned from fairness monitoring to improve procurement practices within PSPC. However, the FMP appears to have had limited impacts in terms of changes to procurement guidelines or policies, in part because fairness issues identified in the course of fairness monitoring engagements are not being systematically reviewed from the perspective of their implications for needed changes to policies or guidelines.

Intermediate outcome

Monitored procurement activities are perceived to be fair, open and transparent.

This outcome was evaluated through interviews with FMP officials and with senior-level clients; the survey of contracting authorities; and a review of program documents and data.

All of the FMP program officials interviewed indicated that the program contributes to both actual and perceived fairness of procurements. While all 13 senior-level clients who responded to an interview question on this topic agreed that fairness monitoring increases perceived fairness, only 5 indicated that it also increased actual fairness. However, 6 of 8 senior-level PSPC clients indicated that fairness monitors had identified potential fairness issues on their procurements and that they agreed with those observations.

We also asked contracting authorities whether fairness monitoring contributed to the actual or perceived fairness of procurements. Of the 25 clients who responded to these questions, only 12 indicated that it increased the actual fairness, while 19 indicated that it increased perceived fairness.

As noted earlier in this report, since 2009, over 300 fairness issues have been identified in summary as a result of fairness monitoring of procurements of which all but 8 identified in final qualified reports were resolved in the course of the procurement. The fact that this large number of fairness issues are being both identified and resolved in the course of the procurement, is a strong indication that the FMP is improving the actual fairness of procurements being monitored.

Another measure of the contribution of the FMP to actual and perceived fairness is a reduction in the number of complaints by bidders to bodies such as the Canadian International Trade Tribunal (CITT), the Federal Courts, or the Office of the Procurement Ombudsman. There was no data available on this measure. However, we asked various stakeholders who were interviewed or surveyed whether they thought this was the case. Some thought that the existence of the FMP reduced the number of complaints to these bodies, while others felt that it did not.

Based on the above, it would appear that, at least according to stakeholders to the program, the FMP contributes to fair, open and transparent procurement processes. Most of them are of the view that the FMP contributes more to perceived fairness of procurements, than to actual fairness. More significantly, since 2009 the program has identified over 300 fairness issues in summary reports, the resolution of which has contributed to improved fairness, openness and transparency of PSPC procurements.

Strategic outcome

FMP contributes to high quality, central programs and services that ensure sound stewardship on behalf of Canadians and meet the program needs of federal institutions.

The program has, for the most part, achieved its intended immediate and intermediate outcomes. By ensuring that fairness monitoring is carried out when warranted and in a timely and effective manner, the program is helping to ensure that PSPC procurements are fair, open and transparent, and are perceived to be so. By contributing to the probity and integrity of procurement activities, the FMP supports sound stewardship on behalf of Canadians and meets the program needs of federal institutions

Conclusions: Performance

The FMP is achieving its intended outcomes, for the most part. Most procurements warranting coverage are being monitored. Clients perceive fairness monitoring to be timely and of quality. Over 300 fairness issues have been identified in summary reports and resolved in the course of procurements. These have provided the basis for the identification of a number of best practices. Based on the above, and on the views of program's direct and indirect clients, and other stakeholders, it appears that the program is contributing to both actual and perceived fairness of procurements and to sound stewardship on behalf of PSPC.

Nevertheless, achievement of program outcomes could be improved through revisions to the current policy to make it more precise with respect to risk thresholds and to ensure that other specific types of procurements that require a fairness monitoring coverage assessment recommendation form due to sensitivity or other factors are assessed. As well, lessons learned reviews could be used effectively to identify systemic issues that indicate the need for changes to policies or guidelines.

Efficiency and economy

To evaluate efficiency and economy, the evaluation conducted an analysis of the average cost per fairness monitoring engagement, based on program financial and output data and conducted interviews with program officials and other stakeholders.

The evaluation also attempted to benchmark the costs of the FMP against other comparable provincial government programs but was unable to obtain financial data for these programs.

Utilizing the above lines of research, the evaluation assessed efficiency and economy against the following indicators:

- fairness monitoring engagement costs relative to the values of monitored procurements

- average cost per fairness monitoring engagement: change over time

Fairness monitoring engagement costs relative to the values of monitored procurements

Most FMP clients that were interviewed indicated that both the direct fairness monitor costs (for which they reimburse the FMP) and their own administrative costs to liaise and coordinate with the fairness monitor and to respond to potential fairness issues are negligible, although none had accurate information on their administrative costs.

This perception is borne out by cost data analyzed by the evaluation team. The evaluation compared the average value of PSPC procurements in 2016 to 2017 and 2017 to 2018 fiscal years that were subject to fairness monitoring with the average costs of the contracted FMs for those procurements. Based on this comparison, the evaluation found that for 2016 to 2017 and 2017 to 2018 fiscal years, on average, fairness monitor costs amounted to 0.01% of the procurement value on average, as shown below in table 5. The average cost per fairness monitoring engagement is very small compared to the procurement value.

| Costs relative to value | 2016 to 2017 | 2017 to 2018 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total value of monitored procurements | $3,652,845,600 | $2,604,260,406 | $6,257,106,006 |

| Number of procurements | 11table 3 note 1 | 9 | 20 |

| Total value of fairness monitoring contracts | $539,449 | $357,383 | $896,832 |

| Average value of fairness monitoring contracts | $49,040 | $39,709 | $44,841 |

| Ratio average fairness monitoring contract to procurement value | 0.01% | 0.01% | 0.01% |

Table 5: Fairness monitoring costs relative to the value of Treasury Board monitored procurements from 2016 to 2017 to 2017 to 2018 fiscal years: Table 3 Notes

|

|||

As shown in table 5, the average fairness monitoring engagement cost is very low in comparison to the average procurement value and there is a significant variation in this ratio from one engagement to another. Fairness monitor contract costs of monitored procurements we reviewed ranged from $24,358 to $105,427, with the contract values ranging from 0.0021% of the procurement value to 0.2626%. The value of Treasury Board procurements covered by a single fairness monitoring contract ranged from $22,995,000 to $2,747,982,752. There is little relationship between procurement value and the cost of the fairness monitor contracts. This stands to reason as the activities involved in monitoring are, to some extent, independent of the procurement value.

Average cost of fairness monitoring engagements

The evaluation team compared the average cost per fairness monitoring engagement for the fiscal years from 2013 to 2014 to 2017 to 2018 using the same methodology used by program officials. Unlike in table 5, both new and ongoing engagements, whether they be mandatory or optional, have been included in the calculation. As shown in table 6, total costs per fairness monitoring engagement (the costs of external fairness monitors and program internal costs) declined over the past 5 years, from $26,533 in fiscal year 2013 to 2014, to $22,755 in 2017 to 2018.

| Variables to calculate cost per fairness monitoring | 2013 to 2014 | 2014 to 2015 | 2015 to 2016 | 2016 to 2017 | 2017 to 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full time equivalents | 6.73 | 7.31 | 6.86 | 5.7 | 5.51 |

| Number of engagements (new and ongoing) | 76 | 74 | 81 | 79 | 85 |

| Average based on total program expenditures | $ 26,533 | $ 30,605 | $ 24,461 | $ 21,699 | $ 22,755 |

| Average cost per fairness monitoring engagement | $ 13,289 | $ 17,044 | $ 11,719 | $ 11,535 | $ 14,060 |

| Average internal coststable 4 note 1 | $ 13,243 | $ 13,561 | $ 12,743 | $ 10,165 | $ 8,695 |

Table 6: Cost per fairness monitoring engagement: Table 3 Notes

|

|||||

During this same period, the average cost of fairness monitor contracts per fairness monitoring engagement increased from $13,289 in fiscal year 2013 to 2014, to $17,044 in fiscal year 2014 to 2015 but then declined to $11,719 in 2015 to 2016. Subsequently, this cost increased to $14,060 in fiscal year 2017 to 2018.

The average internal cost (salary and operation and maintenance) per fairness monitoring engagement was $13,243 in 2013 to 2014 fiscal year but decreased to $8,695 by 2017 to 2018. The biggest component of this reduction has been in salary costs, which declined from $943K in fiscal year 2013 to 2014 to $700K in fiscal year 2017 to 2018. As well, the number of new engagements declined from 47 in fiscal year 2013 to 2014, to 26 in fiscal year 2014 to 2015, and has not since exceeded 30 (table1).

Conclusions: Efficiency and economy

In conclusion, the program is operating efficiently for the most part. The program is small with total expenditures in fiscal year 2017 to 2018 of $1.93 million, with 5.5 full time equivalents. The cost of fairness monitoring contracts relative to the value of monitored procurements at .01% is negligible. Those costs are recovered by the clients. Fairness monitoring engagements have remained steady over the last 4 years while internal program costs have declined, mainly due to staffing vacancies. At the same time, the costs of contracted fairness monitors have ranged between $11,535 to $17,044 over the evaluation period. Overall the program is economical. While the program is operating at a low cost, it has a large mandate which it is meeting, as its existence has resulted in actual and perceived fairness with respect to procurements.

Management response

Management from DOB has had the opportunity to review the evaluation report and accept the conclusions and recommendations as part of our commitment to continuous improvement. A management action plan containing proposed measures to improve the performance and efficiency of our program activities was developed.

Acquisitions Program views this as an important opportunity to address lessons learned and improve operations.

Recommendations and management action plan

Recommendation 1

The Assistant Deputy Minister (ADM), Departmental Oversight Branch should implement changes currently being considered to the Policy on Fairness Monitoring to ensure that all high-risk, high-sensitivity, high complexity procurements are assessed for the need for monitoring, whether or not they require Treasury Board approval.

Management action plan 1

The Fairness Monitoring Directorate will:

- update the Fairness Monitoring Policy to clearly communicate the criteria for mandatory assessment for fairness monitoring coverage (sensitivity and complexity). This includes, ensuring that procurements with high complexity and/or high sensitivity identified through the Project Complexity and Risk Assessment Tool and the procurement risk assessment process triggers the completion of a fairness monitoring coverage assessment and recommendation form for procurements

- revise fairness monitoring intranet pages to reflect the updated Fairness Monitoring Policy

- promote awareness of the Fairness Monitoring Policy to the procurement community within Public Services and Procurement Canada

Recommendation 2

The ADM, Departmental Oversight Branch should take steps to ensure that lessons learned are based on an analysis of all fairness issues identified in the course of monitoring; and that reviews of lessons learned are carried out on a regular basis. In addition, the lessons learned should be shared on a regular basis with Defence and Marine Procurement and Acquisitions, to inform changes to relevant policies, guidelines, procurement manuals and tools.

Management action plan 2

The Fairness Monitoring Directorate will:

- systemize the collection of lessons learned identified by fairness monitors

- prepare quarterly assessments of lessons learned

- share lessons learned:

- at kick-off meetings that are conducted at the beginning of every fairness monitoring activity

- with senior management at the end of each project

- with procurement specialists during awareness sessions

Recommendation 3

The ADMs of Defence and Marine Procurement and Acquisitions, should ensure that policies, guidelines and procurement manuals, in addition to the design of procurement tools supporting them, be regularly reviewed and updated, as warranted based on any systemic fairness issues identified through the FMP's analysis of lessons learned.

Management action plan 3

The Acquisitions Program will develop engagement mechanism between Acquisitions Program and the Fairness Monitoring and Business Dispute Management Directorate to ensure that evaluation observations and systemic fairness issues are being identified and addressed in policy instruments and operationally on a regular basis if, and, as required

Appendix A: Description of program activities

Below is a summary of the activities performed by the Fairness Monitoring Program

Policy and support services

- Develop and renew Fairness Monitoring Policy

- FMP engaged in an extensive review and update of the program in 2011 which resulted in the revision of the departmental Policy on Fairness Monitoring in 2012. The FMP is currently in the process of updating the Policy on Fairness Monitoring in order to clarify requirements related to the scope of its application.

- Provide advice and guidance to clients and other government departments

- FMP is the key contact and centre of expertise on fairness monitoring. FMP provides advice and guidance to OGDs that have or plan to independently acquire their own FMs to monitor an activity being undertaken within their department. The provision of advice and guidance to OGDs requires about 10% of the FMP's internal resources. The FMP also provides advice and guidance to clients to help facilitate completion of the fairness monitoring coverage assessment and recommendation forms.

- Brief and make recommendations to senior management on fairness monitoring coverage

- FMP receives assessment forms from clients, reviews them, gathers information, and develops analysis to support the assistant deputy minister's recommendation for decision to the deputy minister (DM).

- Compile, analyze and share lessons learned with senior management and clients

- Fairness monitoring contractors provide deliverables to the FMP, which includes a lessons learned document at the end of the engagement. These documents are compiled, analyzed, and disseminated to senior management and client groups.

- Deliver awareness/outreach sessions to internal clients and other government departments

- FMP delivers kick off meetings, refreshers, and awareness sessions; conducts follow-up with contracting authorities on the Defence Procurement Outlook Report; and consults and engages with OGDs and industry. FMP also develops and delivers presentations to stakeholders in the National Capital Region and the regions.

Oversee fairness monitoring engagements

- Develop and maintain a method of supply for fairness monitors

- FMP develops and maintains standing offers and supply arrangements for fairness monitors. The standing offer is a national individual standing offer. The standing offer established formal terms of reference for fairness monitoring engagements. Only FMP is authorized to request call-ups against the standing offer and supply arrangement.

- Establish and manage fairness monitoring contracts

- When the DM decides fairness monitoring coverage is warranted, FMP establishes a contract for fairness monitoring. The terms of reference and statement of work template establish general requirements and FMP works with the client to tailor the statement of work to provide context, determine the activities covered, and establish deliverables. FMP evaluates the resources proposed in response to the call-up. Upon acceptance of a proposal, Material Management issues the contract. After the fairness monitor has satisfied the contractual requirements, invoices are delivered to FMP, who then pays the contractor, and subsequently recovers the invoice amount from the client.

- Ensure awareness of roles and responsibilities of stakeholders in a fairness monitoring engagement

- FMP delivers kick-off meetings, refresher meetings, handouts, and engages in periodic consultations with contracting authorities and FMs.

- Provide advice and support to clients

- FMP provides advice and support to clients considering or involved in fairness monitoring engagements.

- Facilitate and help resolve potential fairness deficiencies

- When a notice of a potential fairness deficiency is received, FMP gathers information and helps to facilitate a resolution of the issue at the lowest possible level. A process of escalation is followed. If the issue is not resolved by the contracting authority, it is progressively escalated to the director, director general, and the assistant deputy minister, with the final escalation to the DM, if necessary.

- Brief senior management on fairness monitoring engagements

- FMP is responsible for ensuring that senior management is informed of imminent publication of final reports prior to posting on the departmental website.

Appendix B: Logic model

Text version

This appendix depicts the logic model of the Evaluation of the Fairness Monitoring Program. The logic model depicts program activities, outputs, immediate outcomes, intermediate outcome, PSPC strategic outcome.

Activities

The Fairness Monitoring Program includes 2 areas of activity:

- Policy and support services

- Oversee fairness monitoring engagements

The policy and support services and oversee fairness monitoring engagements activities are comprised of more detailed program activities.

Policy and Support Services

The policy and support activity is comprised of the following 5 activities:

- Develop and renew Fairness Monitoring (FM) Policy

- Provide advice and guidance to clients and to OGDs that request it

- Brief/make recommendations to senior management on FM coverage

- Compile, analyze and share lessons learned with clients

- Deliver awareness/outreach sessions to internal clients and OGDs

Oversee Fairness monitoring engagements

The compliance activity is comprised of the following 7 activities:

- Develop and maintain a method of supply for Fairness Monitors

- Establish and manage FM contracts

- Ensure awareness of roles and responsibilities of stakeholders in a FM engagement

- Provide advice and support to clients

- Facilitate and help resolve potential fairness deficiencies

- Brief senior management on FM engagements

- Publish independent FM reports

Outputs

The activity, policy and support services, leads to the following 8 outputs:

- Updated Policy on Fairness Monitoring

- FM coverage assessment recommendation forms completed

- Verbal and written briefings to senior management

- Memoranda for decision signed by the deputy minister

- Guidelines and tools developed

- Presentations, FM awareness sessions delivered, responses to enquiries

- Lessons learned presented to senior management and clients

- Memoranda of understanding with OGDs are in place

The activity, oversee fairness monitoring engagements, leads to the following 8 outputs:

- Standing offer and supply arrangement and FM contracts in place

- Kick-off and refresher meetings held

- Roles and responsibilities documents

- Statements of work provided to firms

- Deliverables provided by FM firms

- Advice and support provided to clients

- Fairness monitoring reports published on the internet

- Summary documents

Immediate outcomes

The Fairness Monitoring Program includes 2 areas of activity each of which has 2 groups of immediate outcomes:

The policy and support services activity area has 2 immediate outcomes:

- All procurements warranting fairness monitoring are identified and monitored

- Fairness issues are identified and addressed in a timely fashion and at the lowest possible level of decision making

The oversees fairness monitoring engagements has 2 immediate outcomes:

- Clients perceive fairness monitoring services to be timely and of quality

- Lessons learned from fairness monitoring are shared to improve procurement practices

Intermediate outcome

The 4 immediate outcomes under the 2 areas of activity contribute to the following intermediate outcome: monitored procurement activities are fair, open, and transparent and perceived to be so.

Public Services and Procurement Canada strategic outcome

The intermediate outcome contribute to the PSPC strategic outcome: high-quality, central programs and services that ensure sound stewardship on behalf of Canadians and meet the program needs of federal institutions.

Appendix C: About the evaluation

Authority

The Deputy Minister of Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) approved this evaluation, on recommendation by the Audit and Evaluation Committee, as part of the 2018 to 2021 Risk-Based Multi-Year Audit and Evaluation Plan.

Evaluation objectives

The evaluation examined the Fairness Monitoring Program, delivered by the Integrity and Forensic Accounting Management Group of the Departmental Oversight Branch. This evaluation had 2 objectives:

- to determine the relevance of the program: the continued need for the program, its alignment with governmental priorities and its consistency with federal roles and responsibilities

- to determine the performance of the program: the achievement of its expected outcomes and a demonstration of the efficiency and economy of the program

Approach

The evaluation was conducted in accordance with the Treasury Board Policy on Results and the Treasury Board Directive on Results. The evaluation took place between April 2018 and March 2019 and was conducted in 3 phases: planning, examination and reporting. To assess the evaluation issues and questions, the following lines of evidence were used:

- Document review

- An initial document review provided an understanding of the program and its context to assist in the planning phase. Documents including business cases, policy documents, legislation etc. were reviewed to assist in addressing evaluation questions during the research phase.

- Comparative review

- A comparative review of provincial government fairness monitoring programs was conducted to contextualize the program both; to provide theoretical background for the program model; and to identify best practices and alternative delivery models. On-line research was conducted of all 10 provinces and interviews were conducted with officials of 3 provincial government programs.

- Interviews

- The evaluation team conducted 12 interviews with PSPC managers and staff, both internal and external to the program. In addition, the evaluation team conducted 6 interviews with client departments and agencies and 3 with representatives of provincial government programs. The qualitative analysis of the interviews provided information about the program's activities, outputs, expected outcomes, stakeholders, relevance and performance from the perspective of program managers, clients and other related stakeholders.

- Survey

- A survey was developed by the evaluation team to capture the clients' perspective on the performance of the program. The contact list was based on a list of contracting authorities for 43 fairness monitoring engagements that closed in either 2016 to 2017 or 2017 to 2018. The survey provided information on client views on the quality and timeliness of fairness monitoring services and on a range of other questions in support of the evaluation of the achievement of program outcomes.

- Financial analysis

- The evaluation obtained and reviewed program expenditure and resource data for the fiscal years 2013 to 2014 to 2017 to 2018. We also reviewed financial data and other data from a business case prepared by the program in 2014 to 2015 and from an efficiency review carried out in support of the business case to examine the efficiency and economy of the program based on several measures.

- Data analysis

- Program output data on new, ongoing and closed projects from the fiscal years 2013 to 2014 to 2017 to 2018 was obtained and reviewed to assist in the evaluation of continued need and of efficiency and economy.

Data was obtained on the volume of complaints to the CITT for the fiscal years 2010 to 2011 to 2018 to 2019 related to PSPC procurements. This was intended to support an analysis of the cost-effectiveness of the program in terms of avoided costs to the government of such complaints.

Data on the number and value of PSPC procurements for the fiscal years 2015 to 2016 to 2018 to 2019 was obtained and utilized, in conjunction with program data on the number and value of fairness monitor projects, to determine the portion of the procurement universe subject to fairness monitoring. As well, data on the number and value of procurements requiring Treasury Board approval was obtained and analyzed in support of the evaluation of the achievement of immediate outcomes.

Limitations of the methodology

- Survey

- While the survey of contracting authorities provided useful findings, in some areas the survey results could not be used due to low response rates to specific questions. Also, no public opinion research was conducted to solicit Canadians' views as to the role of the FMP in ensuring fair, open and transparent procurement. The views are therefore of direct and indirect clients of the program.

- Comparative review

- The evaluation conducted an on-line research on fairness monitoring programs in other jurisdictions, in particular, provincial governments. Subsequently, interviews were conducted with 3 of the 5 provincial governments identified as having fairness monitoring programs in place. Based on the review of program documentation and the interviews, the evaluation team determined that, these programs contained little in the way of innovations or lessons learned that might enhance the FMP. Most were similar in design to the FMP, but more limited in scope. Consequently, little of value to the evaluation was obtained.

Reporting

Findings were documented in a director's draft report. The program's director general was provided with the director's draft report and a request to validate facts and comment on the report. A head of evaluation draft report was prepared and provided to the Assistant Deputy Minister of the Departmental Oversight Branch for acceptance as the Office of Primary Interest. The head of evaluation draft report was provided to the Assistant Deputy Minister of Defence and Marine Procurement and the Assistant Deputy Minister of Acquisitions for the acceptance as the Office of Secondary Interest. The Office of Primary Interest and the Office of Secondary Interest were requested to respond with a management action plan. The draft final report, including the management action plan, will be presented to PSPC's Performance, Measurement, and Evaluation Results Committee for the DM's approval May 2019. The final report will be submitted to the Treasury Board Secretariat and posted on the PSPC website.

Project team

The evaluation was conducted by employees of the Office of Program Evaluation, overseen by the Director of Program Evaluation and under the overall direction of the Head of Evaluation.