Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities: Closing the gap in health and education outcomes for Indigenous children in Canada

Key Messages:

- A new study by Statistics CanadaFootnote 1found evidence that Indigenous early childhood development programs such as Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities (AHSUNC) are associated with positive health and education outcomes for both elementary and intermediate/high school aged Canadian Indigenous children.

- The study also found that AHSUNC is successfully reaching high risk Indigenous populations. Children who have attended these programs experience significantly greater socio-demographic challenges such as living with a single parent, having a parent or grandparent who attended residential school, living in the north and in a lower income household than those who attended non-Indigenous-focused early child development programs.

- Children and youth who participated in AHSUNC achieve similar health and education outcomes as their peers who are not faced with the same adversity.

- These results suggest that AHSUNC and its focus on Indigenous culture and language helps participating Indigenous children to close the gap in health and education outcomes with non-AHSUNC participants who are not faced with the same adversity. These results also suggest that the program helps these children become more resilient and results in healthier and higher-achieving students.

What is Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities?

- The Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities (AHSUNC) program is a national community-based early intervention program funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

- AHSUNC was introduced in 1995 and focuses on providing culturally-appropriate early childhood development programs for First Nations, Inuit and Métis children and their families who live off-reserve in urban and northern communities.

- More than 4,800 children and their families participate in the program every year at one of the 134 program sites across Canada.

- AHSUNC sites are locally managed and activities are locally designed to allow for flexibility in addressing the unique needs of each community.

- Sites typically provide structured half-day preschool programming for children 3 to 5 years of age.

- The AHSUNC program focuses on six key areas: Indigenous culture and language, education, health promotion, nutrition, social support, and parental and family involvement.

How was the study done by Statistics Canada?

- This study was based on the most recent Canadian population survey data of First Nations people living off reserve, Métis and Inuit people 6 years of age or older from the Statistics Canada 2012 Aboriginal Peoples SurveyFootnote 2.

- Data on the early childhood development program participation of respondents in grades 1 to 12 was collected to examine associations between past early childhood development program participation and current health and educational outcomes in both elementary school and intermediate/high school.

- Most children who attended early childhood development programming with an Indigenous focus were expected to have participated in the AHSUNC program as this is the main off-reserve Indigenous early childhood development program in Canada.

- Socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., single parent household, low income) of Indigenous children and youth who had or had not participated in early child development were also compared.

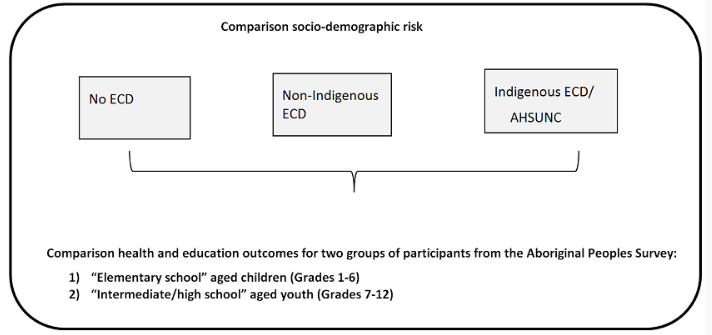

Figure 1. Three types of past early child development (ECD) participation status

Figure 1 - Text Description

In this study there were three types of past early child development participation status. The first was no early child development participation status, the second was non-Indigenous early child development participation status and the third was Indigenous early child development/AHSUNC participation status.

Comparison for socio-demographic risk and comparison of health and education outcomes for two groups of participants from the Aboriginal Peoples Survey was done. The first group was elementary school aged children who were in Grades one to six. The second group was intermediate/high school aged youth in Grades seven to 12.

What did we learn?

1. Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities’ program is reaching children in the greatest need.

Indigenous early childhood development programs are being used by Indigenous children living with the highest level of risk. Indigenous children and youth who participated in Indigenous-focused programs such as Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities (AHSUNC) program come from families experiencing significantly greater socio-demographic challenges compared to those who attended non-Indigenous focused early childhood development programs.

AHSUNC is reaching its intended target of families in the greatest need for early childhood development intervention programming.

Figure 2. Significant differences in socio-demographic risk of children and youth who participated in Indigenous-focused early childhood development (ECD) versus non-Indigenous focussed ECD.

Children and youth who participated in Indigenous-focused ECD (vs. non-Indigenous focussed ECD) were significantly:

- More likely to live in the north

- More likely to live with single parents (measured for elementary-aged only)

- More likely to have parent(s) with low school involvement (significant for elementary-aged only)

- More likely to have a mother with a low level of education

- More likely to have a parent and/or grandparent who attended residential school

- More likely to live in a household with lower income

- More likely to live in households with greater number of people

- Less likely to have a chronic health condition

2. Even with greater socio-demographic disadvantages the Indigenous children and youth who participated in the Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities’ program have similar education and health outcomes as their peers.

Even with significantly greater socio-demographic challenges there were few differences found in education and health outcomes between elementary school aged children (Grades 1-6) who had participated in Indigenous early childhood development programs such as the Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities’ program and other Indigenous children facing less adversity. The same holds true for youth in grades 7-12.

Figure 3. Elementary school aged outcomes for those that attended AHSUNC/Indigenous early childhood development programs.

After accounting for socio-demographic risk factors the AHSUNC participants were as likely to:

- Receive mostly A’s on their last report card

- Receive tutoring

- Be in excellent or very good health

- Not miss school in the past two weeks

- Never repeat a grade

However, they were more likely than non-Indigenous early childhood development participants to have been late for school in the past two weeks.

Figure 4. Intermediate/high school aged outcomes for those that attended AHSUNC/Indigenous early childhood development programs.

After accounting for socio-demographic risk factors the AHSUNC participants were as likely to:

- Receive mostly A’s on their last report card

- Receive tutoring

- Be happy at school

- Be in excellent or very good health

- Be in excellent or very good mental health

- Not miss school in the past two weeks

- Never repeat a grade

- Not be late for school in the past two weeks

However, they were more likely than those who had not participated in early childhood development programs to have skipped school in the past two weeks.

In Summary: After accounting for socio-demographic disadvantages Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities’ participants are doing as well as their peers on most health and education outcomes except for:

- Being late for school (elementary only)

- Skipping school (intermediate/high school only).

What does this mean for the Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities’ (AHSUNC) program?

- Children who are living in greatest socio-demographic risk, like those who attend the AHSUNC program, are at higher risk of poor health and education outcomes. However, those at highest risk are the most likely to gain from early child development intervention Footnote 3.

- This study builds on previous evidence that the AHSUNC program is successful in producing positive short-term school outcomes over the course of one year of programming Footnote 4 and suggests additional positive impact of AHSUNC participation for health and education outcomes in elementary and intermediate/high school.

- This study shows that children and youth who attended AHSUNC programs achieve similar health and education outcomes relative to children of the same age facing less adversity.

- Further examination of barriers and supports to increase punctuality and school attendance outcomes are important for AHSUNC participants and programming.

- These study results suggest that the AHSUNC program is both reaching the most at-risk Indigenous children and enabling them to overcome their socio-demographic challenges to become healthier, higher achieving students in elementary and intermediate/high school.

- This study also suggests that AHSUNC’s culturally and linguistically relevant early child development programming strengthens resilience, helping children to achieve positive outcomes in spite of adversityFootnote 5.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Leanne Findlay and Dafna Kohen of the Health Analysis Division of Statistics Canada for conducting the study on which this report is based.

References

- Footnote 1

-

Findlay, L. C., & Kohen, D. (2016). Early childhood education programs and associations with Aboriginal children’s outcomes in Canada: Closing the gap? Unpublished report. Statistics Canada.

- Footnote 2

-

Statistics Canada. (2012). Aboriginal Peoples Survey: Concepts and Methods Guide. Ottawa: Minister of Industry.

- Footnote 3

-

Duncan, G. J. & Magnuson, K. (2013). Investing in preschool programs. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27, 109–132.

- Footnote 4

-

Public Health Agency of Canada (2012). The impact of the Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities (AHSUNC) on school readiness

skills: Technical Report. Ottawa: Author - Footnote 5

-

Zolkoski, S.M. & Bullock, L.M. (2012). Resilience in children and youth: A review. Children and Youth Services Review, 34, 2295-2303.