Advancing Women in STEM in the Government of Canada

Prelude

Shared Services Canada (SSC) is a federal department that delivers digital services to Government of Canada (GC) organizations. As the Executive Vice-President (EVP) of the department, I am proud to be in a leadership role in a typically male-dominated industry. I have often found myself the only woman on a leadership team, but when I began at SSC, I noticed this was an issue at the working level as well. Recruiting and retaining women in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) is not a challenge unique to SSC. Academia, private and public sectors are all struggling with this.

Diversity is a strength. It leads to more innovation and better outcomes. It's not just the right thing to do; it's the bright thing to do! And senior leaders like myself have a responsibility to lead by example. I am proud of the work we have done over the last year to support women, but there is always more we can do. So we asked Women in Tech World to lead consultations that would replicate their very successful private sector community conversations in the public sector.

Thank you to those who participated in these initial consultations. We have heard you, and we want to keep hearing from you. Women are needed in STEM, and I am certain that the GC is a place where their talents can make a real difference. Through this work, I hope that we can better understand the challenges and barriers faced across the GC, encourage discussion and ultimately build an inclusive and diverse STEM workforce.

Sarah Paquet

Executive Vice-President

Shared Services Canada

Executive Summary

At Women in Tech World we take a community-first approach to data discovery, engaging participants as experts of their own experience. This Community-First Action Plan has been designed to provide a voice to the 43 participants who contributed their experiences, stories, and ideas to promote positive social change for women in STEM (WiS) in the GC. It is a resource for WiS and their allies, andis intended to inform SSC's WiS Strategy and serve as a foundation for ongoing dialogue.

Participants’ Profile: WIS in the GC

- Participants who self-identify as WiS range from 18-65 years old, with the majority being 35-55 years.

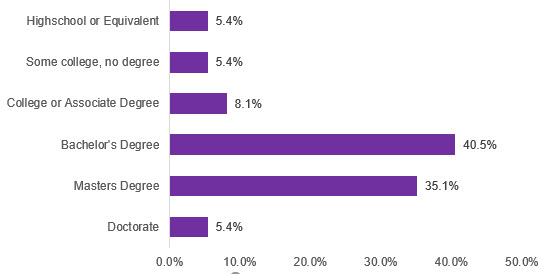

- Amajority hold a Bachelor's or Master's degree and have learned their technical skills, for the most part, through college or university, or self-learning(including on the job). The latter is important as many participants from non-STEM fields stated that being self-taught/lacking credentials impeded their career growth.

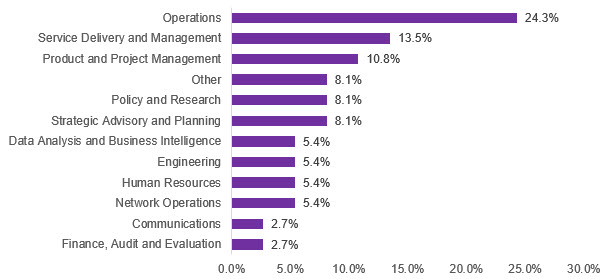

- WiSin the GC hold myriad roles; the top three are Operations, Service Delivery and Management, and Product and Project Management.

- They come from various STEM and non-STEM fields, ranging from engineering, mathematics, and science to business and communications. This dispersion illustrates a need to disentangle the academic definition of STEM from a professional one used in the workplace

Participant Experiences: Stories from WIS in the GC

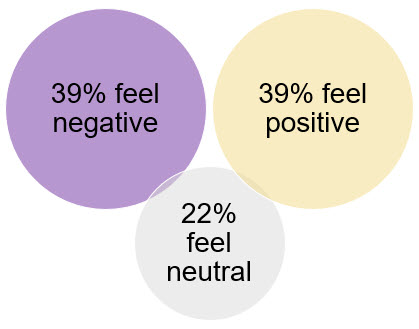

When asked to illustrate their experience in STEM with one story, 39% of employees chose stories that reflected a challenge or negative experience, while 39% told a positive story, and 22% expressed a neutral tone.

Emotive language was used in these stories, including everything from lonely and laborious to enriching and inspiring. This demonstrates the diversity of experiences and perspectives that exists within the group.

While all levels of seniority reported gender bias in the workplace, it was senior staff that reported a lack of “serious movement” to support women in the GC. Those with 10+ years in government observed a cultural shift towards women over time, but felt that it was “bit by bit” and varied by department.

When sharingstories associated with career roadblocks, four key themes emerged. Listed by frequency, they are: (1) Gender Stereotyping and Microaggressions (46%), (2)Lack of Transparency and Barriers to Promotion (27%), (3) Unsupportive Work Environment (19%), and (4) Unclear or Obstructed Career Path (19%).

Each of thesethemes can be classified as direct or indirect outcomes of bias and discrimination, suggesting the need for a systems-change approach to resourceor initiative design.

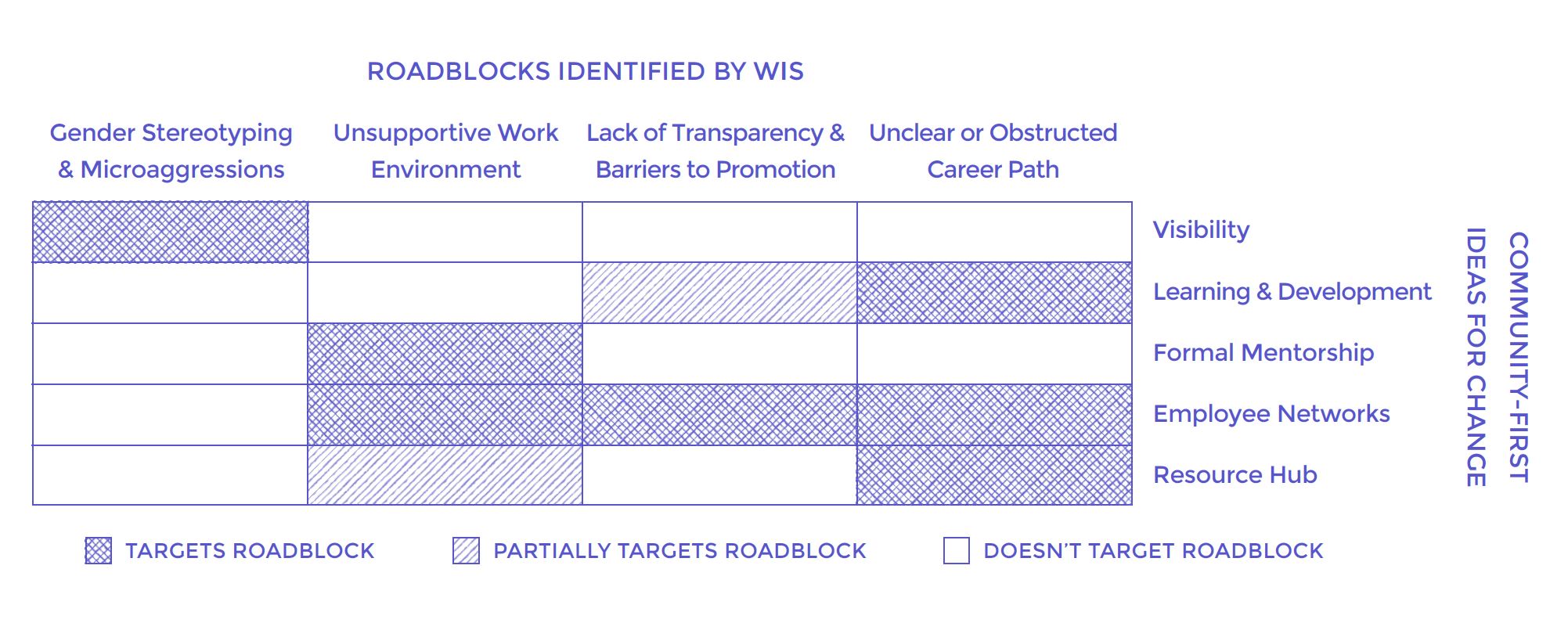

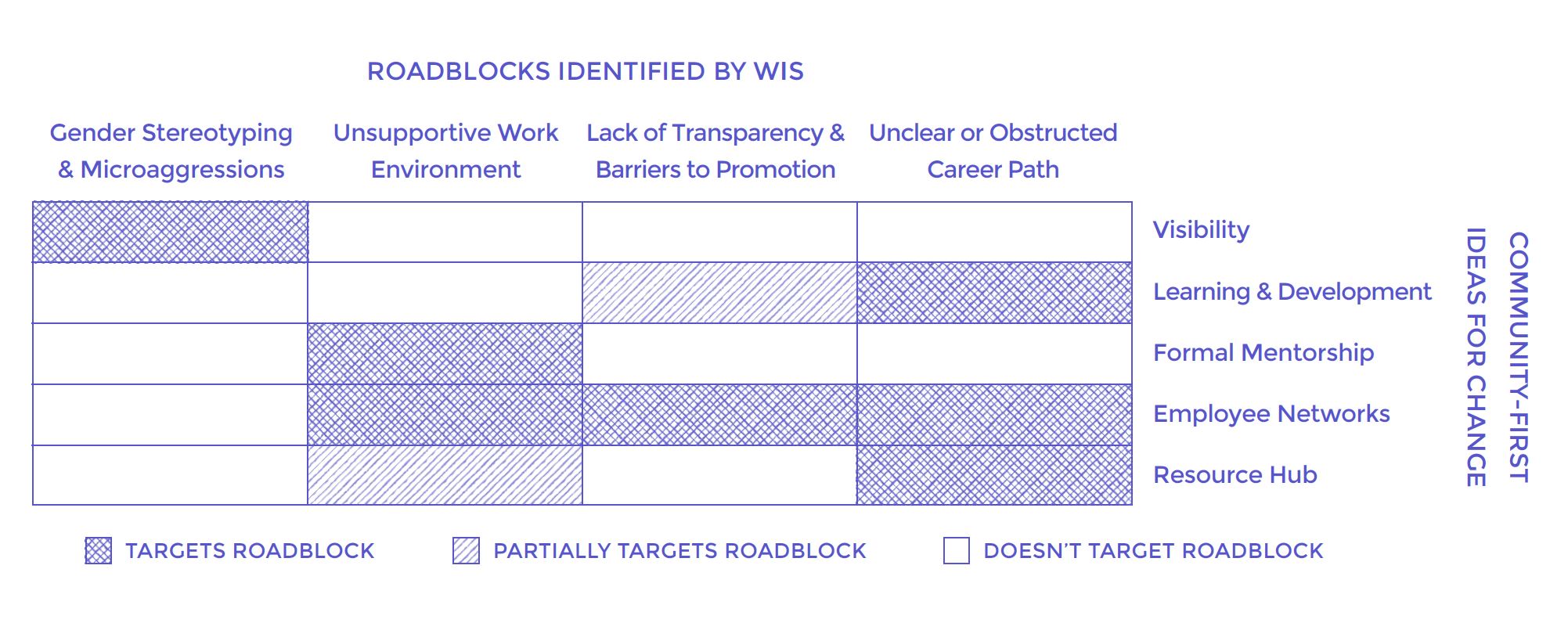

As a finalactivity, participants were asked to contribute ideas on how to help WiS thrivein the workplace. Through individual and group brainstorming, five major themesemerged: visibility, learning and development, formal mentorship, employee networks, and resource hub. These ideas, when bridged to identified roadblocks, target key areas where WiS are looking for support from the GC.

Roadblocks Identified by WIS and Community-First Ideas for Change

Long description - Roadblocks Identified by WIS and Community-First Ideas for Change

The following graphic is a grid that shows how ideas for change can help target roadblocks and challenges for Women who are working in STEM.

Roadblocks that are related to gender stereotyping and microagressions, improving visibility for women can be helpful. However, learning and development, formal mentorship, employee networks and resource hubs do not target this issue.

Roadblocks related to an unsupportive work environments, formal mentorship and employee networks can be helpful. Resource hubs can be somewhat helpful. However, increasing visibility for women and learning and development do not target this issue.

Roadblocks related to a lack of transparency and barriers to promotion, only learning and development partially helps with the issue. Increasing visibility for women, formal mentorship, employee networks and resource hubs are not helpful in targeting this issue.

An unclear or obstructed career path for women, learning and development, employee networks and resource hubs can be helpful. Increasing visibility to women, and formal mentorship are not helpful in targeting this issue.

While employees' ideas touch on each roadblock, there are gaps that need to be addressed, mostnotably under Gender Stereotyping and Microaggressions. Applying a systems-change approach means developing initiatives that dismantle the conditions and mechanisms that impede opportunities.

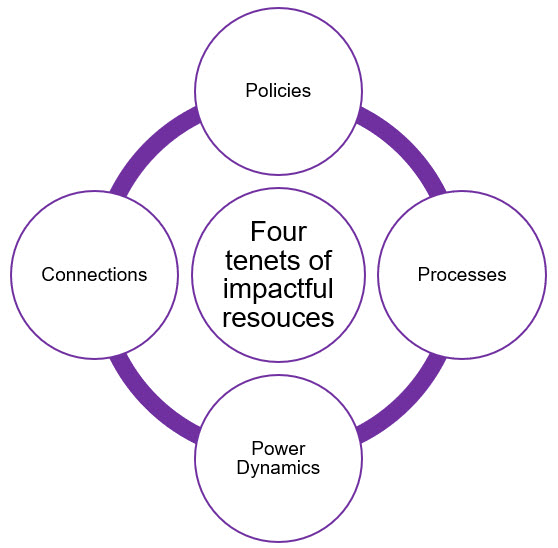

We have outlined four core tenets of systems-change initiatives: policies, processes, powerdynamics, and connections. While not an exhaustive list, these tenets areintegral to developing resources for WiS that will be impactful at a systems level.

What Now

This Community-First Action Plan represents an important step towards positive social change for WiS in the GC, and reveals compelling opportunities to strengthen and expand the WiS Strategy that started this whole conversation.

Perhaps one of the most telling trends that emerged, was the consistent appreciation of strong women leaders in the GC who are championing WiS and openly sharing their experiences and career paths. This active involvement from senior leaders, combined with continued employee discovery and consultations, will serve to strengthen and inform the successful implementation of resources for WiS in the GC.

Overview

Before going into the details of our findings and recommendations, here is a high level overview of our process and their outcomes.

| Individual Voices | Women In STEM Community | Systems Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engagement Level | Low | Medium | High |

| Our process | Data discovery that engages employees as experts of their own experience and equitable stakeholders in the consultation process. | Community consultations bringing WiS and their allies together for shared storytelling, dialogue and ideation. | WiS become partners in organizational change by contributing insights and ideas |

| Outcome | 43 employees engaged, including 37 women in STEM (based on self-identification of gender, education, department, and/or role). | Roadblocks

|

Community-First Ideas for Change:

|

Our Approach

Women in Tech World is a Canadian non-profit dedicated to advancing women in technology through shared storytelling and collective action. With a team of qualified data analysts, researchers, and facilitators, we specialize in our community-first research approach, Driving WinTech.

Between January and March 2020, we facilitated and analyzed a series of community-first consultations within the GC, with a goal of developing an action plan to inform SSC's WiS Strategy. This resource, Advancing Women in STEM in the Government of Canada: A Community-First Action Plan, serves as a first conversation to catalyze additional consultations throughout the federal government.

What is Community-First Research?

Community-first research takes a partnership approach to data discovery that engages participants as experts of their own experience and equitable stakeholders in the consultation process. All participants contribute ideas and resources and then combine this knowledge with innovative solutions for change.

Consultation Methods

Using a mixed-methods approach, we employed (1) a demographic questionnaire; (2) five “live” interactive Community Conversations, hosted virtually and in person; and (3) a qualitative questionnaire for those who weren't able to attend a “live” session. See Appendix A for consultation questions.

Participants were asked to answer a series of demographic questions, and identify whether they consider themselves a woman in STEM. Throughout consultations and this resource, the term “woman/women” is used to denote women-identifying people.

During each Community Conversation, employees were guided through a series of interactive activities that involved individual writing as well as group discussion. We engaged 43 employees, collecting written accounts and questionnaires as well as 5.9 hours of recorded dialogue; this information was transcribed and analyzed using machine learning and manual coding to pull themes, sentiments, and trends.

Questionnaire Design

All questions and activities were developed and tested by a diverse group of qualified researchers. All procedures and questions were also reviewed by experts in the field of diversity and inclusion, ensuring this project followed consultation and research best practices.

Considerations

Consultations rooted in qualitative methods do not focus on the need for a large sample size to establish significant results. Each voice and story is valid and warrants weight in any action plan or considerations that come out of the conversation.

That said, this resource is not meant to be a static guide, but rather a compilation and reflection of learnings to date, highlighting the value of continued dialogue with WiS in the GC. As demonstrated by the Community Conversations, further consultations are needed to strengthen and expand on our findings. Additional data could allow for:

- A more nuanced analysis of trends and intersectionality

- Deeper insight into interdepartmental and regional differences

- A more robust definition of WiS in the GC

Consultations were hosted in Ottawa and Toronto over the course of one week. While virtual options were available, it's possible that employees were unable to attend due to time zone, weather, or schedule restraints. Also, virtual options provide a different environment than in-person sessions, which may affect how employees interact and share.

What We Discovered

Who are Women in STEM?

The term STEM was first used in 2001 by Judith Ramaley, Director of Education and Human Resources at the U.S. National Science Foundation.Endnote 1 The acronym stands for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, and was used as a way to think about curriculum design and knowledge categorization for these interdisciplinary fields.

Today, STEM has become a buzzword, making its way into mainstream debates around workforce skills and equity gaps; popping up in the media, at events, and in policy; and appearing in programming and organizational titles. The problem is, the term wasn't designed for these uses, and people are left wondering what, if any, of the conversations or initiatives apply to them.

This sentiment was articulated by consultation participants:

“Please let's define what a woman in STEM [...] ‘looks like' (figuratively). Not every woman in STEM is a coder or in a lab; so what IS a woman in STEM?”

“Computer Systems (CS) is considered as ‘tech,' which often creates mental barriers for people in other categories to experiment.”

Women in STEM in the Government of Canada

Given ongoing confusion around the term “STEM,” it was important to invite all employees to self-select into the consultation. This approach allows a better understanding of who identifies as a “woman in STEM,” and can serve as a resource for strategy development and initiatives.

During consultations, we connected with 43 public servants from 14 departments, both within and outside of the National Capital Region. Participants self-identified into over 8 ethnic groups, including Canadian, French, Filipino, Middle Eastern, Italian, Latin American, and Asian. Thirty-seven (86%) participants were woman-identified STEM professionals or women who work on STEM projects/teams, and six (14%) self-identified as not being a woman in STEM (two were men)

Using participant demographics, we can begin to answer the question: Who are WiS in the GC? Let’s take a look.

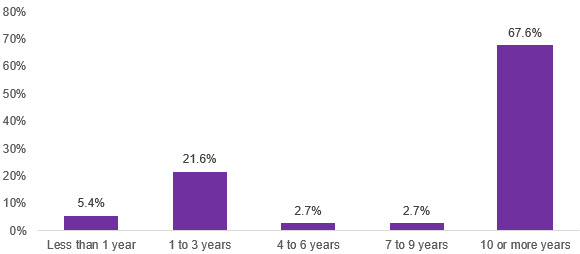

Length of employment

Long description - How long have you worked in the Government of Canada?

This chart shows that 5.4% of participants have worked in the Government of Canada less than one year, 21.6% have worked between one and three years, 2.7 percent have worked between four to six years and seven to nine years and 67.6% have worked 10 years or more.

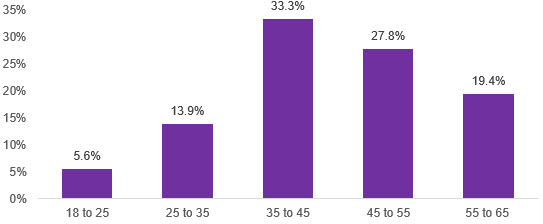

Age Groups

Long description - How old are you?

This chart shows that 5.6% of participants are between 18 to 25 years old, 13.9% are 25 to 35 years old, 33.3% are 35 to 45 years old, 27% are between 45 and 55 years old and 19.4% are between 55 and 65 years old.

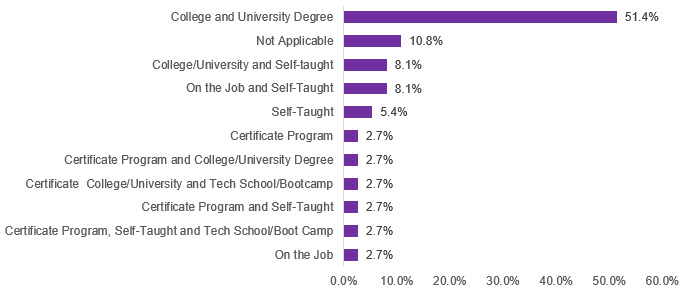

Technical knowledge

Long description - How did you learn your technical skills?

This chart shows that 51.4% of participants obtained their technical skills through a college or university degree, for 10.8% the question was not applicable, 8.1% were College/University and self-taught or on the job and self-taught, 5.4% were self-taught, and 2.7% obtained their skills through a certificate programs, or a combination of certificate programs and degrees, as well as on the job training.

Role within the GC

Long description - Which of the following best describes your role?

This chart shows that 24.3% of participants work in operations, 13.5% work in service delivery and management, 10.8% work in product and product management, 8.1% work in policy and research, strategic advisory and planning or other roles, 5.4% work in data analysis and business intelligence, engineering, human resources and network operations and 2.7% work in Communications or finance, audit and evaluation.

Field of Study?

| Field of Study | Percent |

|---|---|

| Anthropology, Global Studies and International Affairs | 2.7% |

| Business | 10.8% |

| Communications | 2.7% |

| Computer Science | 2.7% |

| Computer Science and Business | 8.1% |

| Computer Science and Mathematics | 8.1% |

| Cyber security | 2.7% |

| E-Commerce and Interior Design | 2.7% |

| Engineering | 5.4% |

| Engineering and Management | 5.4% |

| Engineering and Mathematics | 2.7% |

| Information Technology | 8.1% |

| Law Enforcement | 2.7% |

| Mathematics and Statistics | 2.7% |

| Operational Research and Information Management Systems | 2.7% |

| Political Sciences | 2.7% |

| Psychology and Public Administration | 2.7% |

| Science (e.g. Biology, Microbiology, Geochemistry, Food Sciences, Ecology) | 16.2% |

| Sociology | 2.7% |

| Telecommunications | 2.7% |

| Women and Gender Studies. | 2.7% |

Education

Long description - What is the highest degree you have earned?

This chart shows that 5.4% of the participants have a high school or equivalent degree or some college or no degree, 8.1% have a college or associate degree, 40.5% have a bachelors degree, 35.1 percent have masters degree and 5.4% have a doctorate.

Seniority

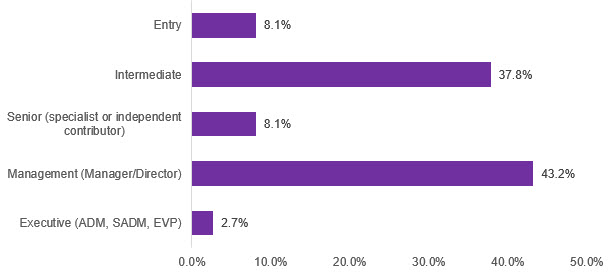

Long description - Which of the following categories best describes your role?

This chart shows that 8.1% of the participants describe themselves as in an entry position or a senior position (as a specialist or independent contributor), 37.8% consider their role to be intermediate, 43.2% are in management as managers or directors and 2.7% are at the executive level as ADMs, SADMs or EVP.

A Closer Look

While a majority of participants came from Management and Intermediate roles, and held 10+ years in the government, this is not necessarily representative of the actual dispersion of WiS. It is possible that those in Management and Intermediate roles were more motivated or encouraged to attend than those in entry-level roles or with fewer years. Additional data is required to confirm the findings.

These visuals tell us that WiS in the GC represent a diverse group including multiple roles, lengths of employment (<1 to 10+ years), and a range of ages (18-64). While a majority hold a Bachelor's or Master's Degree and learned their technical skills in this environment, 27% of WiS are self taught or learned some of their technical skills on their own accord.

What's more, “field of study” illustrates that women who self-identify as working in STEM are coming from educational fields both within and outside of the standard STEM fields, demonstrating a need to disentangle the academic definition from the professional definition used within the workplace.

The variety of roles that we see, combined with representation from 14 departments at these consultations, suggests the need for an interdepartmental WiS Strategy.

Voices of Women in STEM

In community-first work, importance is placed on shared stories and dialogue. To introduce this approach, participants were asked to choose one word that they would use to describe their experience working in STEM, and to illustrate this with a story. The stories that participants chose provide valuable insights into “top-of-mind” or overarching feelings that WiS associate with their career.

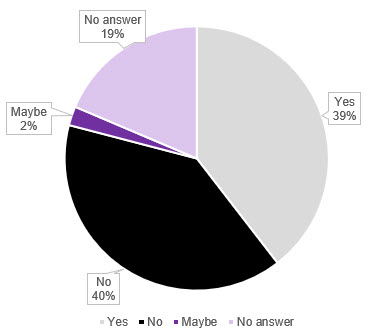

Long description

This diagram shows that 39% of participants feel either negative or positive, and 22% feel neutral.

Participants used 33 different words (see Appendix B) to describe their experiences working in STEM. While 39% of these words were tied to stories that spoke to a challenge, roadblock, or negative experience; 39% told a positive story; and 22% expressed a neutral tone.

Throughout, a broad range of emotive language is used, including everything from lonely and laborious to enriching and inspiring, demonstrating a diversity of experiences and perspectives that exist within the group.

This contextual range is important in itself. While some stories spoke more broadly to the rewarding aspects of working in STEM, others recalled experiences that stood out as pivotal moments in their career, for better or worse.

How did we figure out the sentiments?

We used natural language processing as a “first pass” to categorize stories based on tone polarity. For instance, if a participant was mostly stating facts and did not reveal any clear feelings, this would be neutral. We reviewed these findings manually to ensure that the nuance in each story was captured.

Quotes

Throughout this resource, the stories of WiS are used to illustrate our findings. While we weren't able to include every story, we aimed to represent the voice of WiS as a whole. We acknowledge and thank each participant who contributed their thoughts.

“A staff member told me, “If I think of you as a man, everything you do makes sense”. This completely shocked me as I had assumed there was no gender bias in my workplace. [...] When can we arrive at a point where this is no longer a required topic of conversation?”

“I was able to maintain a continuous learning framework to learn not only technology [but] stay current. It also taught me how to be agile, to adapt to change. [...] it is rewarding to see the impact that the work I do has on the public sectors and Canadians.”

“I've often felt like a lone voice in the wilderness because many of my roles have involved challenging the status quo of IT management in the government [...]. [Women in management] were definitely in the minority.”

An opportunity to challenge myself and others with respect to the status quo as a woman in the tech industry. Hence an opportunity to grow and learn from others to implement change from within.”

Interestingly, the most commonly used word was challenging/challenge, a word that turned up in all three categories: positive, negative, and neutral.

“I started about 40 years ago in computer engineering. [..] As a woman, I had a lot of challenges, not from technology but from people who work with me. They can't accept that a visible minority, woman [... ] is successful. It was kind of hell [...].”

“It's challenging because my career has gone in directions I didn't plan, in a good way.

It is challenging being in a world where I will never fully understand what is going on and I have to accept it.”

“There are ups and downs. Very often I have to reinvent myself to [...] stay in the field. I met several roadblocks but as well, several allies. [...] I met a lot of amazing people that I wouldn't have met if I didn't choose my work field.”

Each employee is an expert of their own experience, and the stories shared reflect the nuances of individual experience based on the person, team, and department. Together, their words tell a more robust story of WiS in the GC.

With this in mind, let's zoom out from the individual experience to discover the bigger picture.

Exploring Patterns

Taking a systems approach involves stepping back, asking questions, and looking for patterns. One way to do this is through exploring trends within stories that participants told, and how these relate to their demographics (see Appendix C). For these consultations, the most compelling trends were seen for: department, field of study, and seniority and years in government.

The goal of a systems approach is to dismantle structural social barriers through engineered change. This requires acknowledgment and modification of key elements of an organization, including changes to policy, resources, power dynamics, and thought models.Endnote 2

Department

One of the high-level trends that arose throughout consultations was the impact of different management styles and processes across departments. Participants recalled how their experiences with gender bias and career progression varied as they moved within the GC:

“Since day one [...] I have felt welcomed and supported. There is no pressure to know everything and career progression is a large focus [...]. In a previous role [...] I felt that because I didn't have a degree or background in science, my opinions weren't valued or even heard. There were no opportunities provided to learn [...] and no opportunities for career progression.”

“I have worked in science for about 20 years now. I'm currently working for a department where I feel valued and not discriminated against. Unfortunately, over the course of my career, this has not always been the case.”

Field of Study (STEM vs Non-Stem)

Another interesting trend was found between those who came from a STEM field of study and those who did not. While both groups felt their workplace to be male-dominated, particularly in management/supervisors roles, and gender-biased in hiring, women from STEM fields also specified that there was a distinct lack of tech staff or management who could help on projects.

Meanwhile, those from non-STEM fields spoke of being frustrated in their career progress by needing tech experience/education and yet not being provided the time or funding for professional development.

“...being self-taught and not having the ‘right' credentials has seriously impeded my STEM career.”

“So in STEM, or in similar services, everyone's a techie. So that's the only skill that's valued. I have a business degree, I can communicate, I'm outgoing [...] But those skills aren't valued.”

“They are always complaining that they cannot find staff, but when technical/ specialized staff is presented to them, they don't welcome that staff, do not agree to authorize standard training made by the department.”

While both groups lean on informal networks and allies for support, they are also looking for more structured resources to advance in their careers. In the case of women from STEM fields, ideas emerged around building formal tech meetups and mentoring opportunities, whereas women from non-STEM backgrounds asked for resources and support to increase their tech education, such as job shadowing, programs, and podcasts.

Seniority and Years in Government

Employees' level of seniority exposed a number of interesting findings, most notably that while all levels report gender bias in hiring, management, and culture, it was Management and Executives that reported favouritism and a lack of “serious movement” to support women.

The most distinct trend was an observation around cultural shift over time. Those with 10+ years in the government felt that while there has been a shift in the past 30 years in attitudes towards women, this has been “bit by bit.” There was a clear sense of shock from this group to learn that young WiS are experiencing the same things that they experienced over 20 years ago.

Speaker 1:

“...even in high school, there were a lot of surprises. I felt like I couldn't say when I knew something [...] If we were all working on a problem together, if I had it right I was a little bit nervous to say, “Oh we have the answer” Because it would be like, “You know it?” Or, “You got that grade? You did?” And it was like, “Why? Why are you surprised?”

Speaker 2:

“So what I said was “interesting, there's 30 years difference between us,” and I said, “Oh my God you're experiencing what we're experiencing.” It doesn't even matter about the age. She's already experiencing all this. And this wasn't even top of mind for me, being taken seriously, but that is top of mind all the time [...] it's just it's a norm now.”

“You know, bit by bit. You have to look at it in shifts of culture from 20, 30 years ago. I think we are advancing.”

These patterns begin to paint a picture of what WiS are experiencing within the GC. We see how educational background has impacted these women in different ways, and that WiS experience gender bias regardless of level of seniority. There has been progress over time for women in the workplace, but there is still room for improvement in access to resources and systems-change initiatives to support WiS across all departments.

Roadblocks

These patterns begin to paint a picture of what WiS are experiencing within the GC. We see how educational background has impacted these women in different ways, and that WiS experience gender bias regardless of level of seniority. There has been progress over time for women in the workplace, but there is still room for improvement in access to resources and systems-change initiatives to support WiS across all departments. When talking about roadblocks, there's a tendency to place responsibility for change on the individual. People will cite personal barriers, such as confidence issues and negotiation skills, as the reason that women “can't get ahead”.

Having witnessed this trend in previous initiatives (e.g., Canada's Gender Equity Roadmap and Discovery Foundation's B.C.'s Gender Equity Roadmap), we acknowledge that personal barriers are a very real piece of the conversation. However, for this consultation, we asked participants to put that piece on the shelf and instead focus on stories that go beyond perceived personal limitations.

From this lens, we asked employees to share any roadblocks that they have experienced in their careers within the GC; four key themes emerged from their stories.

| Roadblocks | Characterized by participants as: | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Gender Stereotyping and Microaggression | Biased language, non-verbal or verbal microaggressions, and feelings of not | 46% |

| Lack of Transparency and Barriers to Promotion | Lack of transparency and access to employee networks combined with favouritism and silos. | 27% |

| Unsupportive Work Environment | Male-dominated culture, unsupportive management, undervalued, and alone. | 19% |

| Unclear or Obstructed Career Path | Lack of mentorship or valuable guidance/resources on career options or trajectory. | 19% |

These themes are defined by participant stories and can each be considered direct or indirect outcomes of a broader theme of bias and discrimination.

The Confidence Myth

A commonly held belief is that women are less confident than men in the workplace, leading to decreased career success.

While research shows that women are less likely to boast about their accomplishments, it’s not due to a lack of confidence. In fact, women self-report similar levels of confidence to men,Endnote 3 but have greater fear of social backlash from self-promotion.Endnote 4 While women are being told to be more confident, they are then penalized for doing so.

Key Definitions

Bias

Defined as preferring or favouring, often unfairly, one individual (or thing) over another. Bias can be positive or negative, and is often described as either implicit (unconscious) or explicit (conscious). Endnote 5

Discrimination

Defined as an individual (or group) being treated unfairly or poorly in comparison to other individuals (or groups). Discrimination can be direct or indirect, and can include exclusion, denial, victimization, or harassment, amongst other things.Endnote 6

Gender Stereotype

Defined as an observation of different genders possessing distinct characteristics or playing certain roles that are assumed to always exist within those genders. Gender stereotyping can be damaging if people perceive themselves as constrained by these generalizations, which may prevent or influence personal skills development and decision making.Endnote 7

Microaggressions

Defined as everyday derogatory, hateful, or otherwise negative communications towards an individual based purely on their membership within a marginalized group. Microaggressions can be verbal or nonverbal, intentional or unintentional.Endnote 8

Gender Stereotyping and Microaggressions

Participants defined Gender Stereotyping and Microaggressions as including assumptions about identity, offensive language, unsolicited feedback, and perceptions that reinforce gender stereotypes, as well as feelings of not being taken seriously or having a voice in the workplace. Stories collected ranged from subtle, everyday offenses to explicit content.

“Be softer, be more approachable, don't be so direct.”

“...people assume that I want to get married and have children, simply because I'm a woman, even to the extent of being told: ‘But you're so pretty, you won't have any trouble getting a man!'”

“Because I am a young woman, I am often talked over, interrupted and dismissed.”

“I face barriers because it is assumed that I am too emotionally invested in whatever I do. I tried to change this about myself for a very long time until very recently in my life when I was like, actually this is maybe one of the best things about me.”

“...assumptions, when challenged, are revealed to be rooted in ageist, patriarchal, racist roots. Management doesn't address these issues, even when brought up with them, as they believe it is not an issue/they do not see their role in enabling biases.”

“I have been asked to ‘take the high road' when confronted with macro/microaggressions.”

“I was in a meeting with an executive suite [...] and there were a variety of transphobic statements that were made at that table.”

Workplace Harassment and Violence

Under Bill C-65 the GC defines harassment and violence as “any action, conduct or comment, including of a sexual nature, that can reasonably be expected to cause offence, humiliation or other physical or psychological injury or illness to an employee, including any prescribed action, conduct or comment.”Endnote 9

There were several stories shared of gender-based harassment as well as violence in the workplace, the latter of which was reported to human resources (HR). As such, despite the commitment to Bill C-65, harassment and violence remain a reality in the GC.

Lack of Transparency and Barriers to Promotion

Participants reported issues in a variety of HR processes, specifically with regards to barriers to promotion. They observe gender bias and a lack of transparency in hiring and promotions, and express frustration with their interest in career progression going unacknowledged.

“Women in the federal government do not have good networks for moving up. There is a lot of talk about promoting women, but I don't know if that is ever actioned in an effective way.”

“...my interest in moving into management was not taken seriously. There was favouritism in the selection process for some management positions.”

“It is unclear how the hiring process is undertaken and how work is assigned—it seems opportunities may not be distributed based on education and experience, but manager preference. It seems untransparent.”

Unsupportive Work Environment

Participants described an unsupportive environment rooted in male-dominated culture, norms, and group dynamics. Here, employees reported experiences of exclusion and non-acceptance, and feeling like the “only one.”

“I had challenges early on being the only female in a very male-dominated field. In certain jobs, I was the only woman in the room for most meetings and felt I had to put up with a lot of bad behaviour and work twice as hard, to be accepted by my peers.”

“Since science can sometimes be an ‘old boys club,' it has required me to be resilient and persevere despite challenges. I felt [department] was the worst of the ‘old boys clubs' that I have experienced as a woman working in STEM.”

“Not being taken seriously by a manager—work I am fully capable of completing is being passed on to the men in CS positions. It feels like I need to work twice as hard to prove I can do my job.”

Unclear or Obstructed Career Path

Participants defined Unclear or Obstructed Career Path as an undefined or unsupported career path in STEM, including not having somewhere to go when they need help professionally. Participants also mentioned a lack of access to resources and developmental programs.

“Lack of mentoring always seems to be an issue in government no matter where you are. Having champions, [...] networks that include both women and men seem to be limited; we are in silos.”

“No clear career path. Wide-open to chart direction for yourself, [...] which may not work for everyone in conservative culture of the federal government.”

“...limitation in the career evolving by not having as many contacts in the CS community because there is a majority of men. [...] it's still possible, but when the numbers are against you, there's just less opportunities.”

“Another resource I used, career services [within our] department and, again, it was useful to a point [but there were] limited options regarding possible courses. It didn't help [me] design a career path.”

Based on these themes and the stories shared, it's clear that there is work to be done to better support WiS in the workplace, from building a supportive culture and challenging norms, to addressing unclear processes and pathways that are contributing to feelings of gender bias.

Next we dig into existing resources, why they work or don't work, and the gap between needs versus wants.

Women in STEM Strategy

In 2019, SSC developed a strategy to support WiS. This includes four pillars: governance, recruitment and retention, learning and development, and awareness. It is designed to help close existing gaps for WiS through targeted activities, including a monthly Women in STEM Meetup.

During consultations, we asked participants to answer a few questions specific to resources proposed within the WiS Strategy.

Women in STEM Meetups

In 2019, SSC launched monthly Women in STEM Meetups as part of their WiS Strategy. Out of all participants, 40% were aware of these meetups, and when asked to rank which resource they most wanted to see implemented from the WiS Strategy, Women in STEM Meetups were the top-ranked initiative.

Only 26% of those aware of the monthly meetups were SSC employees, demonstrating interest in this resource for WiS outside of SSC.

Accessibility

Attendees were asked if they felt that the monthly Women in STEM Meetups supported them in the way that they needed (for example, format, location, and so on). This question allows a deeper understanding of the impact and potential areas of improvement for the Women in STEM Meetups.

Long description - Women in STEM Meetups

This chart shows that 39% of the participants are aware of the Women in STEM Meetups and 40% are not, while 2% may know and 19% provided no answer.

Of those who participants who answered “yes” they were asked: does this resource support you in the way that you need? Is it provided in a format that you like? They responded:

| Yes | 6 |

|---|---|

| Yes, but | 6 |

| No | 3 |

| Not Applicable | 2 |

Here’s what they said:

“...as it is done during the lunch hour, it doesn't seem to be well supported by senior management. [...] These group discussions are an excellent start, they are painted by the ‘pet project' paintbrush as they occur off of work hours.”

“Women in STEM discussion groups are the first I've encountered, although I wish they would hold the events in additional locations (e.g. not only Ottawa).”

“For the most part, it is accessible. The key is hearing about it, making sure we're in the know.”

While there is work to be done on communicating the Women in STEM Meetups, there is interest in this resource, and those who are aware of the meetups do find them useful. Outside of communication, the consistent feedback around areas of improvement are timing, location, and information technology (IT).

Top 3 Resources or Initiatives

In the WiS Strategy, SSC proposed a number of targeted initiatives (see Appendix D), in addition to monthly meetups. When asked to rank these in order of what they would most like to see implemented, participants chose:

1. Learning Events

A series of learning events for empowering women in the workplace (e.g., TEDxWomen, International Women’s Week).

2. Speed Mentoring

Women can participate as mentors or mentees and have the opportunity to discuss one-on-one about their career and life experiences.

3. Take Me With You

A program that encourages employees to ask managers to take them to meetings. This will be used to promote EVP's WiS role at speaking engagements.

Outside of formal ranking,

“All of those are excellent! Very exciting to have those resources at the top of my career.”

“It was a tough call! They are all great initiatives :)”

Resources and Initiatives

After reflecting on challenges faced as WiS, participants shared what resources exist to support them. Many of the resources named are informal, with 35% including networks such as “work family”, and “colleagues supporting each other” as a key resource. In terms of formalized resources, participants listed leadership training, Women in STEM Meetups, and specific resources such as the Ombudsman, the Association of Professional Executives of the Public Service of Canada (APEX), and GC Docs.

An underlying story also emerged around a lack of awareness of resources specific to WiS, both internal and external to the GC.

Types of Existing Resources

| Resource | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Informal Network | 35% |

| Associations and Committees | 25% |

| Training and Coaching | 23% |

| Mentoring | 20% |

| Women in STEM Meetups and Discussions | 18% |

| Ombudsman and Office for Informal Conflict Management | 13% |

| Supportive Management | 10% |

| Working Group and Safe Spaces | 10% |

| Role Models | 5% |

| On-line Resources | 5% |

| Events and Competitions | 5% |

| Gradual Return to Work | 3% |

Why These Resources Work

Through their experiences with existing resources, participants identified five characteristics that contribute to an effective resource. This checklist is important to keep in mind when developing or improving resources and initiatives for WiS.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pave the way for Learning | Create a supportive community | Provide a safe space | Help raise awareness of opportunities | Promote work-life balance |

Five Characteristics of an Effective Resource

1. Pave the Way

Being able to see a career path through role models, champions, sponsorships, and learning by seeing.

“We definitely [...] feel the difference from when [women-identified executives] joined the leadership team. [They've] really raised the awareness of women, not what we can do, but it's more encouraging women to be more involved and take charge of their areer [...]. I think that's influenced a lot of the women.”

“...the amazing women we've encountered throughout our careers and continue to encounter who are very invested in supporting other women, and [...] how those people, especially if they're in middle management or in the executive area, are invested in moving barriers for us. [...] Women who are in these powerful positions and who are paving the way for us.”

2. Supportive Community

Feeling like there is a network of people to bounce ideas off of, get feedback from, and learn from.

“...the people I sit with aren't even on my team but they've become a resource because we have unique situations all the time coming up at work.”

“I have a group of women from previous work. We meet occasionally at a restaurant to discuss our lives. I always looking forward to those meetings. It's a way also to vent and share ideas and compare our lives.”

3. Safe space

Opportunities that allow different personalities to feel safe, to share their stories and be heard.

“We've all experienced some form of these typesof things, whether it's gender bias or whatnot, but we've all experienced that at some point. So it's just nice to actually hear some people share stories like that. So you know that you're not alone in those thoughts or feelings.”

“As an introvert working with extroverts, I'd like to do more in writing/reading instead of verbal communications.”

4. Raise Awareness

Initiatives that generate more awareness about WiS opportunities within the GC.

“...these types of discussion events have been a great resource, and well obviously raising awareness and allowing a lot of discussion, we find that's a very helpful resource.”

5. Work-Life Balance

Policies and management encouraging work-life integration and accommodating different needs through remote work, gradual return to work, etc. Of all the WiS-identified attendees, 62% identified as a primary caregiver, either to a child or “other” (for example, parents, grandparents, and so on).

“I feel like I've been given a lot of opportunity to balance my work by working remotely part of the time. And I really appreciate it because as a mom and a parent, I have to manage both worlds.”

While the conversation uncovered a number of supportive resources for WiS, participants also identified several areas of improvement. For the most part, these relate back to awareness or access to information, issues around resource accessibility (for example, by region and personality type), and trust.

“[Resources] are there, but I do not trust it.”

“Although I have heard of some [resources], I am not currently aware how to access.”

“I am not aware of a resource that can help for real. I remember a VP met with the visible minorities and she advised them if you have a problem at work just leave and look for another job.”

“There are plenty of support resources, but not specific to women. Not that are advertised.”

“...we would like to see more opportunities and resources for the introverted. Because there's a lot of networks and in-person talking, but it can be hard to speak up at a table when you're an introvert.”

It is clear that WiS value social connection and access to resources and knowledge, and that there are a variety of, mostly informal, initiatives that they find effective. It's important to consider why these resources work, as well as acknowledge perceived limitations and distrust when developing and communicating new initiatives.

The stories and feedback shared represent an opportunity to better support WiS in the GC. In the next section, we apply these contributions to the development of an action plan to inform the WiS Strategy.

An Action Plan for Women in STEM

Community-First Ideas for Change

In their final activity, participants were asked to step into the shoes of designer and decision maker, and offer their ideas for how to help WiS thrive in the workplace. Through a process of individual and group brainstorming, five major themes emerged:

- Visibility

- Formal Mentorship

- Employee Networks

- Resource Hub

- Learning and Development

The ideas that employees offered were specific to the context of the GC, providing unique insight into the mindset and priorities of this important stakeholder. Where relevant, these ideas are supported by external research throughout this section.

Visibility

A consistent ask was for increased visibility of and access to WiS, both within and outside of the GC. Employees expressed gratitude for women-identified leaders who have shared their journeys in a public forum, and suggested ongoing, targeted events that provide more of this.

Participant ideas include:

- Increased exposure to role models through profiling women leaders and arranging in-person or virtual opportunities for dialogue and learning from these women.

- Channels and campaigns that showcase women, their career paths, experiences, and “how they did it.” Participants suggested these channels include a newsletter, magazine, podcast, or video series.

- Mechanisms to ensure increased equality for women “at the table,” such as a panel pledge and activities to raise awareness about unconscious bias.

Research Reality

In a study examining the impact of role modelling on adolescent girls in villages in India, researchers found that when women held visible leadership roles in their community, such as elected officials, there was a 32% increase in local girls' career aspirations.Endnote 10

Building on this, researchers agree on the importance of modelling in career progression, with the caveat that when there are not enough women in leadership roles, there is risk of women learning from “negative” role models, which can depress career aspirations.Endnote 11

Formal Mentorship

Employees suggested a breadth of options for mentorship programs that would allow them to learn from leaders and scientists within and outside of the GC, as well as from their peers and the next generation of WiS. They spoke to the need for these programs to be easy to participate in, and suggested both informal and formal options.

Some of their ideas include:

- Matching programs (for example, buddy program, job shadowing, speed mentoring).

- Informal “go-to's” at the executive level (where executives could provide advice and guidance).

- Reverse mentorship (for example, providing a seat at the executive table for a young woman) and interdepartmental and external networking opportunities

Research Reality:

Research suggests that mentorship programs are one of the most effective ways to address barriers to promotion and retainment for minorities.Endnote 12 However, they have to be done well. Mentorship programs must involve management, engage senior-level mentors, and intentionally match personalities. Like with role models, there are also negative implications with selecting ineffective mentors— something to be aware of when developing a program.

Employee Networks

Under this theme, employees shared their ideas for connecting with other WiS, in order to grow their network. This includes providing opportunities to gather and engage with the broader WiS community, Canada-wide.

Participant ideas include:

- Building an app for a coordinated network of WiS to actively connect with one another

- Creating a “club” or “Slack for Women” to access support internally

- Hosting a “Me to We” style event in celebration of WiS that includes speakers from the GC and the private sector, and welcomes people of all ages and genders to participate

Research Reality

Research shows that male managers promote men faster not based on performance, but on socializing and being a part of the “boys club.”Endnote 13 And while building women networks won’t dismantle this biased system, studies have shown that women who have strong women networks are more likely to succeed in their career relative to women who don’t. Endnote 14

Resource Hub

This idea illustrates participants' interest in an easily accessible hub (that is, “not buried within layers and layers of other sites”) that provides resources, contacts, FAQs, and chat rooms. According to participants, this could be a “Women in Tech Portal” or website on each department's intranet that would be easily accessible and included in onboarding of new WiS to the GC.

Additional elements suggested by the participants:

- Monthly agenda of internal events

- Directory of Canada-wide contacts for WiS

- Repository of government and non-government resources for WiS

Learning and Development

Employees cite L&D as important for career progression and tackling unconscious bias, and talk about the importance of encouraged participation in these activities. There was interest in a range of topics, with emphasis placed on offering both gender-specific and all-gender spaces for discussion and learning.

Specifically, participants suggest:

- Updated digital skills training and tutoring for all ages and abilities

- More opportunities for shared storytelling and dialogue on challenges faced

- Learning events, including unconscious bias training and “opportunities to teach people about intersectionality”

Research Reality

In 2018, LinkedInEndnote 15 published a learning report that underscored the importance of digital skills training, with 94% of employees correlating L&D opportunities with willingness to stay in a job. Accessibility (e.g., format and tools) and encouragement from managers were listed as two of the most important factors in L&D success.

Unconscious Bias Training

While helpful in theory, experts warn against using this training as a quick fix or one-off approach to addressing systemic issues in an organization.Endnote 16 This training is not evidence based, and in some cases can even make things worse.Endnote 17 Unconscious bias training should only be offered within the context of a systems-change plan to address bias and discrimination.

Mapping Your Routee

There are three sequential steps to consider when mapping your route to support WiS within the GC:

- Building the Bridge

Bridge community-first ideas for change to roadblocks of WIS - Addressing the Gaps

- Taking a Systems-Change approach

Apply a systems-change approach to the WIS Strategy

Building the Bridge

First, let’s take a look at how employee ideas for change bridge to identified roadblocks.

Roadblocks Identified by WIS and Community-First Ideas for Change

Long description - Roadblocks Identified by WIS and Community-First Ideas for Change

Text goes here

Addressing the Gaps

While employees' ideas touch on each roadblock to varying degrees, there are gaps that need to be addressed, most notably under Gender Stereotyping and Microaggressions. This roadblock was also the most commonly cited within participant experiences.

Despite the gaps, each idea is still valuable, even where it checks only one box. In fact, some of the ideas suggested are already reflected in the WiS Strategy.

Taking A Systems-Change Approach

Applying a systems-change approach means developing initiatives that dismantle the conditions and mechanisms that get in the way of employee opportunities. When applied effectively, this approach provides an opportunity to create lasting, positive social change in an organization.

Below, we have outlined four core tenets of systems-change initiatives: policies, processes, power dynamics, and connections. While not an exhaustive list, these four tenets are each integral to developing resources for WiS that will be impactful at a systems level.

Long description - Four tenets of impactful resources

The diagram are a series of circles which shows the four tenets of impactful resources, which are policies, processes, connections and power dynamics.

Policies

Defined as formalized rules, regulations, priorities, and procedures that guide organizational action.

Things to consider

- Defined procedure for tracking D&I metrics and assessing resources

- Formal accountability structure for personnel decisions

- Clear and accessible policy and procedures on Harassment and Violence in the workplace

To ask

What metrics are you using to track D&I initiatives? Have you asked your employees their thoughts on these initiatives? How will success of these programs (for example, mentorship) be measured?

What policies are driving equitable and transparent personnel decisions? Are these policies shared with employees?

Is there a formalized process for tracking and addressing violence or harassment in the workplace? Has HR been trained on addressing different cases? Do employees trust the established procedures and feel safe to report?

Processes

Defined as organizational activities and norms that ensure policies are upheld; the way an organization structures and carries out their operations.

Things to consider

- Transparency in hiring decisions and formal processes to promotion

- Accessible opportunities for example, for meetups, L&D)

- Managerial encouragement for employees to engage in learning opportunities

To ask

Are career trajectories shared with employees so that everyone is informed about career paths? Is there documentation on how personnel decisions are made?

Are initiatives accessible for all (for example, schedule, location, IT)? Does the subject matter of meetups and events range to account for different WiS roles in the GC (for example, natural science, data analysis, operations)?

Are learning opportunities prioritized? What policy/ procedures will be put in place to support Learning and Development or other employee development programs?

Power Dynamics

Defined as informal or formal influence of people or groups on one another; the way in which power is shared.

Things to consider

- Interdepartmental D and I teams

- Executive sponsorship for WiS Strategy and other initiatives

- Meeting guidelines

To ask

Is there interdepartmental collaboration and communication regarding D&I programs? How is this facilitated?

Do leaders value and support WiS initiatives? Is there overall buy-in from leadership that WiS programs are a priority?

Is space and encouragement provided to all who want to speak in meetings? Are there opportunities for varied personality and leadership types to contribute?

Next Steps

This Community-First Action Plan serves as a resource for WiS and their allies within the GC, providing a voice to those who the WiS Strategy aims to support. As evidenced by employees' stories and ideas, there is an opportunity here to design systems-change initiatives that are equitable, inclusive, and grounded in the needs of the WiS community.

These consultations were an important first conversation, and have helped pave the way for further and more in-depth research to continue this valuable discovery process. In the meantime, the trust that has been built through shared stories and dialogue can be harnessed, and the insights from this resource can be put into action.

Appendices

Appendix A: Consultation Questions

- What is one word you would use to describe your personal experience working in STEM? Why did you choose this word?

- What roadblocks or challenges have you experienced as a woman in STEM throughout your career? Please describe in detail.

- Are there any roadblocks or challenges that you have experienced at the Government of Canada as a woman in STEM? Please describe in detail.

- Reflecting on the challenges you’ve faced, is there a resource that exists that supports you in a way that you need? Describe this resource in detail.

- Is the resource accessible? Is it provided in a format that you like?

- Do you have access to the resources you need to support you as a woman in STEM at the Government of Canada today? Please provide your feedback in detail.

- Are you aware of the monthly Women in STEM Meetups across the Government of Canada? Please circle: Yes/No

- If yes, does this resource support you in the way that you need? Is it provided in a format that you like?

- Please rank your top 3 resources or initiatives, from the list below, based on what would support you the most in your career as a woman in STEM. See Appendix D for the full list of resources.

- If you would like to expand on your choices, please add your feedback in the notes section below.

- Is the resource accessible? Is it provided in a format that you like?

- If you could design up to four resources for women in STEM to thrive in your workplace, what would they be?

Refer to Appendix C for the demographic questions.

Appendix B: Full List of Words

These words were chosen by participants to describe their personal experience working in STEM and were categorized based on the sentiment expressed in their story.

Positive:

- Work-life balance

- Satisfying

- Growth

- Enriching

- Re-invention

- Challenging

- Zig-zag

- Welcoming

- Inspiring

- Rewarding

- Exciting

- Courage

Negative:

- Resilience

- Discouraging

- Frustrating

- Success or Challenge

- Ignored or Undervalued

- Lonely

- Judged

- Frustrating

- Shocking

- Challenge

- Laborious

- Undervalued

- Underutilized

- Intricate

Neutral:

- Self-confidence

- Random

- Leaders

- New

- Challenging

- Satisfactory

- Integrated

- Change

Appendix C: Research Participants Demographics

Totals that are greater 100% are due to rounding errors.

| 18 to 24 | 4.8% |

|---|---|

| 25 to 34 | 16.7% |

| 35 to 44 | 31.0% |

| 45 to 54 | 31.0% |

| 55 to 64 | 16.7% |

| Less than one year | 7.0% |

|---|---|

| 1 to 3 years | 25.6% |

| 4 to 6 years | 2.3% |

| 7 to 9 years | 2.3% |

| 10 + years | 62.8% |

| Entry Level | 11.6% |

|---|---|

| Intermediate | 32.6% |

| Senior Level | 9.3% |

| Management | 41.9% |

| Executive | 2.3% |

| Other | 2.3% |

| College degree | 50.0% |

|---|---|

| Not applicable | 14.3% |

| College/University | 7.1% |

| College/University and self-taught | 7.1% |

| Self taught | 7.1% |

| Certificate Program | 2.4% |

| Certificate program and College or University degree and Tech school/bootcamp | 2.4% |

| Certificate program and College/University degree | 2.4% |

| Certificate program and self taught | 2.4% |

| Certificate program and self-taught and tech school/bootcamp | 2.4% |

| On the job | 2.4% |

| Bachelors degree (for example, BA, BS) | 39% |

|---|---|

| College or Associate degree (for example, AA, AS) | 9.3% |

| Doctorate (for example, PhD, EdD) | 7.0% |

| Masters Degree (for example, MA, MS, Med) | 34.9% |

| High school degree or equivalent (for example, GED) | 4.7% |

| Some college, no degree | 4.7% |

| Business | 14.3% |

|---|---|

| Science (for example, Biology, Microbiology, Geochemistry, Food Science, Ecology) | 14.3% |

| Business and Computer Science | 7.1% |

| Computer Science and Mathematics | 7.1% |

| Information Technology | 7.1% |

| Communications | 4.8% |

| Engineering | 4.8% |

| Engineering and Management | 4.8% |

| Psychology and Public Administration | 4.8% |

| Computer Science | 2.4% |

| Cyber Security | 2.4% |

| Engineering and Mathematics | 2.4% |

| Interior Design and E-Commerce | 2.4% |

| Law Enforcement | 2.4% |

| Anthology, Global Studies and International Affairs | 2.4% |

| Mathematics and Statistics | 2.4% |

| Nursing (for example, Gerentology) | 2.4% |

| Operational Research and Information Management System | 2.4% |

| Political Science | |

| Sociology | 2.4% |

| Telecommunications | 2.4% |

| Women and Gender Studies | 2.4% |

| Operations | 20.9% |

|---|---|

| Service and Delivery Management | 11.6% |

| Human Resources | 9.3% |

| Other | 9.3% |

| Policy and Research | 9.3% |

| Product and Project management | 9.3% |

| Data analysis and business intelligence | 7.0% |

| Strategic Advisory and planning | 7.0% |

| Communications | 4.7% |

| Engineering | 4.7% |

| Network Operations | 4.7% |

| Finance, audit and evaluation | 2.3% |

Appendix D: Resources and Initiatives

Full list of Resources and Initiatives proposed as part of SSC’s WiS Strategy, ranked in order of popularity by the participants (calculated using weighted average):

| 1 - WiS Meetups | Informal monthly meetups. |

|---|---|

| 2 - Learning Events | Series of learning events for empowering women in the workplace (for example, TEDxWomen, International Women's Week). |

| 3 - Speed Mentoring | Women can participate as mentors or mentees and have the opportunity to discuss one-on-one about their career and life experiences. |

| 4 - Take Me With You | A program which encourages employees to ask managers to take them to meetings. |

| 5 - Dr. Roberta Bondar Program | A two-week career development program for young women in science and technology to network with industry leaders and peers. |

| 6 - Panel Pledge | A campaign in support of gender diversity, which asks participants to decline sitting on a panel that does not include more than one woman. |

| 7 - Women in STEM Blog | A blog by the EVP on the challenges and insights into WiS and micro actions. |

| 8 - EVP National Engagement | Strategic opportunities for the EVP to meet with WiS and academia as part of national engagement trips. |

| 9 - Living Library | A human library event on International Women's Day to showcase brilliant women and their stories. |

| 10 - Awareness of Women in IT | Online Twitter campaign that will initiate awareness about WiS within the GC. |

Resourcess

Women in Tech World. (2018). Canada's gender equity roadmap: A study of women in tech.

Women in Tech World. (2018). Discovery Foundation's B.C. gender equity roadmap: A study of women in tech.

Acknowledgements

Authors

Alicia Close, Founder & CEO, Women in Tech World

Melanie Ewan, Lead Researcher & Writer / Board of Directors, Women in Tech World

Rebecca Factor, Research Writer, Women in Tech World

Special Thanks

We would like to warmly thank each participant for sharing their experiences and ideas throughout this consultation.

Shared Services Canada

A special thanks to the SSC team. There were a few people who were particularly instrumental.

Christina Cyr, Analyst, Strategic Relations and Engagement

Dao Huynh, Analyst, Strategic Relations and Engagement

Maxine Merhej, Analyst, Strategic Relations and Engagement

Claire Niedbala, Manager, Strategic Relations and Engagement

Jeanette Rule, Manager, Special Projects, Communications Branch

Women in Tech World

Katie Beaton, Editor

Josef Filipowicz, French Translator

Preeti Hemant, Data Analyst

Rachel Jean-Pierre, French Facilitator

Indu Khatri, Data Analyst

Jihane Lamouri, French Translator

Lauren Olson

Lisa Taniguchi, Report Designer

About Women in Tech World

Woman in Tech World partnered with SSC to expand on the Government of Canada's Women in STEM strategy.

Women in Tech World is a Canadian non-profit dedicated to supporting and advancing women in tech through shared storytelling and collective action. This is delivered through the following initiatives:

Driving Wintech

This initiative includes community-based consultations as outlined in this Action Plan, designed to advance women in tech within and outside of the workplace.

Women in Tech Mastermind Series

In partnership with MyCEO, this is a six-month peer-to-peer mentorship program, including high-impact learning from Industry Experts.

In 2018, Women in Tech World published Canada's Gender Equity Roadmap: A Study of Women in Tech and Discovery Foundation's B.C.'s Gender Equity Roadmap. These studies brought together the collective voices and ideas of more than 1600 self-identified women in tech and their allies, marking the first time in history that so many people have come together to create change in the Canadian tech sector.

Women in Tech World is thrilled to be recognized for our Driving WinTech research initiative internationally as a Science & Research finalist against NASA – Goddard Space Flight Communications Division.

While our focus is women in tech, we aim to support and advance women in all male-dominated industries related to tech, including those in STEM.

Supporting Women in Tech World

To learn how to partner with or support Women in Tech World, please contact:

Partnerships, Women in Tech World

Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Tip the scale