Annual Report to Parliament for the 2018 to 2019 Fiscal Year: Federal Regulatory Management Initiatives

On this page

- Message from the President

- Introduction

- Types of federal regulations

- Cabinet Directive on Regulation

- Section 1: benefits and costs of regulations

- Section 2: implementation of the one-for-one rule

- Section 3: update on the Administrative Burden Baseline

- Appendix A: detailed report on cost-benefit analyses for 2018–19

- Appendix B: detailed report on the one-for-one rule for 2018–19

- Appendix C: administrative burden count

Message from the President

President of the Treasury Board

As the President of the Treasury Board and the Minister responsible for federal regulatory policy and oversight, I am pleased to present this third annual report to Parliament on federal regulatory management initiatives.

This report provides important information on three key initiatives outlined in the Cabinet Directive on Regulation and the Red Tape Reduction Act: the analysis of benefits and costs in federal regulations; the one-for-one rule; and the Administrative Burden Baseline.

While Canada’s regulatory system is highly regarded internationally, it must continue to keep pace with evolving challenges and emerging economic opportunities. New digital technologies and growing global trade, for example, have increased pressure on businesses to be more efficient and competitive in a global context.

In this spirit, the Government is taking steps to make Canada’s regulatory system more agile, transparent and responsive — one that continues to be ranked among the best in the world and that has positive effects on the lives of all Canadians.

For instance, we have championed international and domestic regulatory cooperation to address regulatory barriers with the United States, the European Union, as well as the provinces and territories. We also introduced, in 2019, the first regulatory modernization bill to allow regulators to remove outdated or redundant legislative requirements that act as barriers to modernizing our regulations.

In addition, the Government is undertaking targeted regulatory reviews in the areas of clean technology, digitalization and technology neutrality, and international standards. The goal of these reviews is to reduce barriers to economic growth and competitiveness, and to advance new regulatory approaches that support innovation. Finally, we established the External Advisory Committee on Regulatory Competitiveness to bring together business leaders, academics, and consumer representatives to advise us on regulatory competitiveness and innovation.

Looking ahead, in 2020, we will begin a full review of the Red Tape Reduction Act and the one-for-one rule to review its implementation and consider its continued operation.

I invite you to read this report to see how the Government is continuing to implement its modernization agenda to support effective, agile regulations, while ensuring the protection of our environment and the health, safety and security of Canadians.

Original signed by

The Honourable Jean-Yves Duclos

President of the Treasury Board

Introduction

This is the third annual report to Parliament on federal regulatory management initiatives. This report is part of regular monitoring of certain aspects of Canada’s regulatory system.

This year’s report has three main sections:

- Section 1 describes the benefits and costs of regulations that were made by the Governor in Council and that have a significantFootnote 1 cost impact.

- Section 2 reports on the implementation of the one-for-one rule, fulfilling the Red Tape Reduction Act reporting requirement.

- Section 3 sets out the Administrative Burden Baseline for 2018 and for previous years, providing a count of administrative requirements in federal regulations.

The regulations reported on in this document were published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, in fiscal year 2018–19, which covers the period from , 2018, to , 2019.

Types of federal regulations

Regulations are a type of law intended to change behaviours and achieve public policy objectives. They have legally binding effect and support a broad range of objectives, such as:

- health and safety

- security

- culture and heritage

- a strong and equitable economy

- the environment

Regulations are made by every order of government in Canada in accordance with responsibilities set out in the Constitution Act. Federal regulations deal with areas of federal jurisdiction, such as patent rules, vehicle emissions standards and drug licensing.

There are three principal categories of federal regulations. Each is based on where the authority to make regulations lies:

- Governor in Council (GIC) regulations are reviewed by a group of ministers who recommend approval to the Governor General. This role is performed by the Treasury Board.

- Ministerial regulations are made by a minister who is given the authority to do so by law.

- Example: The Criminal Code authorizes the Attorney General of Canada to approve equipment that is designed to ascertain the presence of a drug in a person’s body.

- Regulations made by an agency, tribunal or other entity that has been given the authority by law to do so in a given area, and that do not require the approval of the GIC or a minister.

- Example: The Canada Grain Act authorizes the Canadian Grain Commission to make orders related to the allocation of railway cars for shipping grain.

Cabinet Directive on Regulation

The Cabinet Directive on Regulation (CDR) came into effect on , replacing the Cabinet Directive on Regulatory Management (CDRM) as the policy instrument that governs the federal regulatory system.

The new directive updates Canada’s regulatory policy and is based on three broad concepts:

- emphasis on the regulatory life-cycle approach

- reinforcing good practices in the regulatory development process (consultation, transparency and cost-benefit analysis)

- alignment with government priorities such as regulatory cooperation, gender-based analysis, environmental impact assessment and Indigenous-Crown consultation, as well as requiring periodic reviews of the stock of regulations

A transition period was established, recognizing that regulatory proposals normally take several months to develop. Proposals that were at an advanced stage of development when the CDR came into effect were able to continue under the CDRM requirements so long as they were finalized by .

Because the CDR came into force part way through 2018–19, this report covers regulations made under both it and its predecessor, the CDRM. The 2019–20 report will also include a number of regulations developed according to the former requirements.

A total of 46 GIC regulations were finalized under the CDR in 2018–19, accounting for 24% of the 192 regulations finalized in that year.

Only 1 regulation that had a significant cost impact was finalized under the CDR in 2018–19, accounting for 4% of the total of 26 regulations in that category of impact level that were finalized in that year. All proposals are now being developed under the CDR.

Section 1: benefits and costs of regulations

What is cost-benefit analysis?

In the regulatory context, cost-benefit analysis (CBA) is a structured approach to identifying and considering the economic, environmental and social effects of a regulatory proposal. CBA identifies and measures the positive and negative impacts of a regulatory proposal and any feasible alternative options so that decision-makers can determine the best course of action. CBA monetizes, quantifies and qualitatively analyzes the direct and indirect costs and benefits of the regulatory proposal to determine the proposal’s overall benefit.

Since 1986, the Government of Canada has required that a CBA be done for most regulatory proposals in order to assess their potential impact on areas such as:

- the environment

- workers

- businesses

- consumers

- other sectors of society

The results of the CBA are summarized in a Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement (RIAS), which is published with proposed regulations in the Canada Gazette, Part I. The RIAS enables the public to:

- review the analysis

- provide comments to regulators before final consideration by the GIC and subsequent publication of approved final regulations in the Canada Gazette, Part II

Analytical requirements

The analytical requirements for CBA as part of a RIAS are set out in the Policy on Cost‑Benefit Analysis, which was introduced on , in support of the new Cabinet Directive on Regulation. This represents the first time that CBA requirements for Canadian regulations have been enshrined in policy.

The policy requires both robust analysis and public transparency, including:

- reporting stakeholder consultations on CBA in the RIAS

- making the CBA available publicly

Regulatory proposals are categorized according to their expected level of impact, which is determined by the anticipated cost of the proposal. Under the new directive, the categories of impact level were realigned with the analytical requirements for CBA. This report presents results according to the new categories, which are as follows:

- no-cost-impact regulatory proposals: proposals that have no identified costs

- low-cost-impact regulatory proposals: proposals that have annual national costs of less than $1 million

- significant‑cost‑impact regulatory proposals: proposals that have $1 million or more in annual national costs (merges the former medium- and high-impact categories)

Table 1 illustrates how the new categories align with the former categories.

| New cost impact level | Former cost impact level | Present value of costs (over 10 years) | Annual cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | Low | No costs | No costs |

| Low | Low | Less than $10 million | Less than $1 million |

| Significant | Medium or high | More than $10 million | More than $1 million |

The level of impact determines the degree of analysis and assessment that is required for a given regulatory proposal. This proportionate approach is consistent with regulatory best practices set out by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Table 2 shows the analysis required for each level of impact.

| Impact level | Description of costs | Description of benefits |

|---|---|---|

| None | Qualitative statement that there are no anticipated costs | Qualitative |

| Low | Qualitative | Qualitative |

| Significant | Quantified and monetized (if data are readily available) |

Quantified and monetized (if data are readily available) |

In this report, information on CBA covers GIC regulations only and is limited to regulatory proposals that have a significant cost impact under the new categories and to those that have a medium- or high-impact under the former categories. When the new directive was introduced, a transitional strategy allowed proposals that were in the latter stages of development to proceed for approval using the former requirements. Consequently, this report includes regulations made under both the new requirements and the former requirements.

Figures in this report are taken from the RIASs for regulations published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, in 2018–19. To remove the effect of inflation, figures are expressed in 2012 dollars and, therefore, will vary from those published in the RIASs. This approach permits meaningful and consistent comparison of figures, regardless of the year in which regulatory impacts were originally measured.

Overview of benefits and costs of regulations

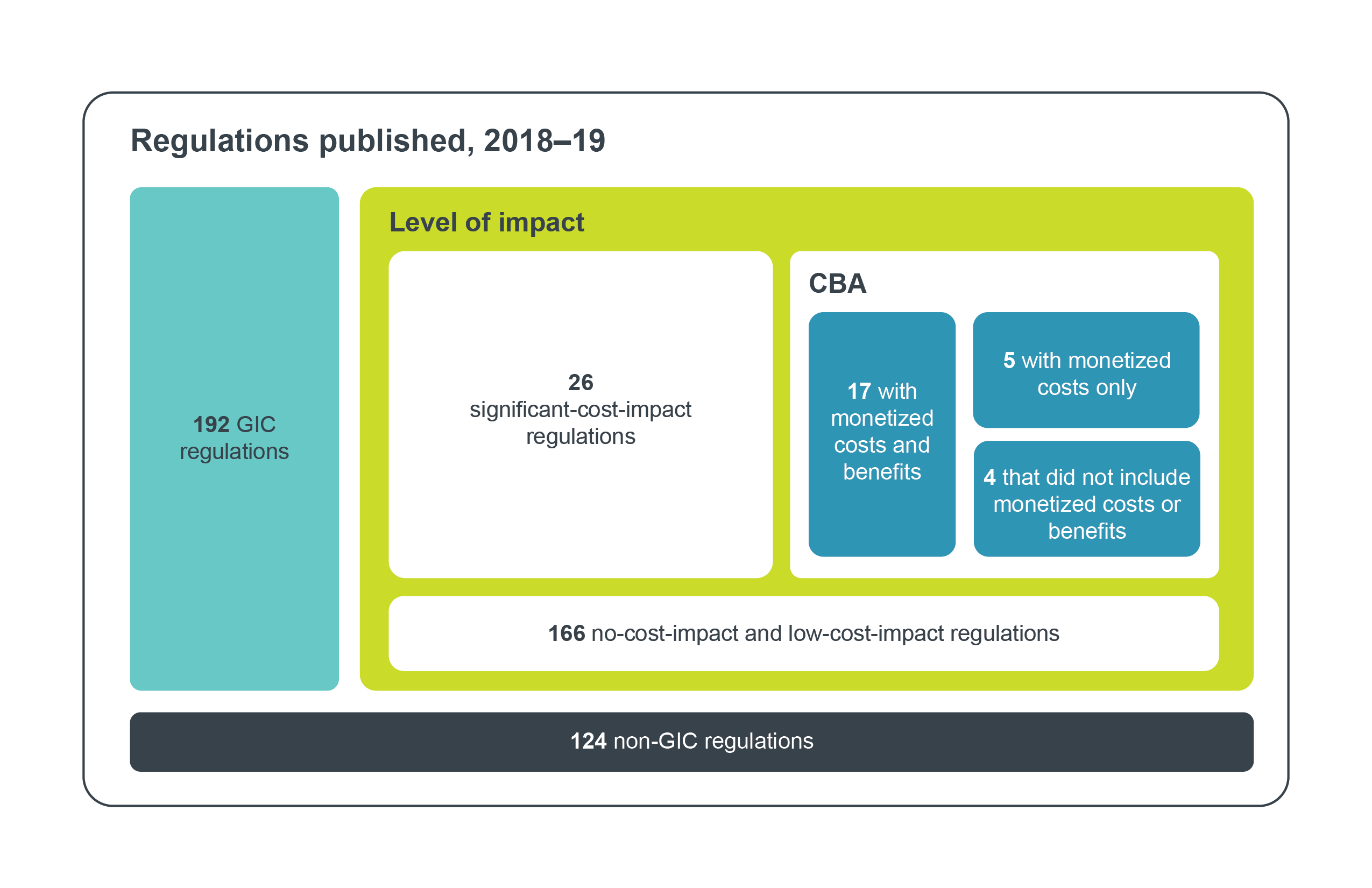

In 2018–19, a total of 316 regulations were published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, compared with 292 in 2017–18. Of these 316 regulations:

- 192 were GIC regulations (60.1% of all regulations)

- 124 were non-GIC regulations (39.3% of all regulations)

Of the 192 GIC regulations (compared with 184 in 2017–18):

- 166 had no cost impact or low cost impact (86.5% of GIC regulations and 52.5% of all regulations)

- 26 had significant cost impact (13.5% of GIC regulations and 8.2% of all regulations)

Figure 1 provides an overview of regulations approved and published in 2018–19.

Figure 1 - Text version

Figure 1 provides an overview of the categories of regulations approved and published in the 2018-19 fiscal year.

During this period, 124 non-Governor in Council regulations were published, and 192 Governor in Council regulations were published.

Of the 192 Governor in Council regulations, 166 were no-cost-impact or low-cost-impact regulations, and 26 were significant-cost-impact regulations.

Of the 26 significant-cost-impact regulations, 17 had a cost-benefit analysis of monetized costs and benefits, 5 had an analysis of monetized costs only, and 4 did not include monetized costs and benefits.

Qualitative benefits and costs

The most basic element of any analysis of costs and benefits is a description of the expected impacts of the regulatory proposal. This description is based on a qualitative analysis and is used to:

- provide decision-makers with an evidence-based understanding of the anticipated impacts of the regulation

- provide context for further analysis that is expressed in numerical or monetary terms

Qualitative analysis should be part of the CBA of all regulatory proposals, including those that have no cost impact or low cost impact.

The following are examples of qualitative impacts identified in significant‑cost‑impact regulations in 2018–19:

- The Regulations Amending the Employment Insurance Regulations (Pilot Project No. 21) will benefit 51,500 Employment Insurance (EI) claimants annually by reducing the incidence and duration of income gaps faced by seasonal claimants in the 13 targeted EI regions.

- The new Trademarks Regulations will simplify the process for those seeking a trademark in Canada (both for domestic and foreign applicants), which could lead to more competition in the marketplace and more options for consumers.

- Changes to flight crew scheduling requirements under the Regulations Amending the Canadian Aviation Regulations (Parts I, VI and VII — Flight Crew Member Hours of Work and Rest Periods) will benefit passengers, commercial air operators, crew members and the Government of Canada through avoided fatalities, injuries, property damages, investigations, and through improved flight crew welfare.

Quantitative benefits and costs

Quantitative benefits and costs are those that are expressed as a quantity, for example:

- the number of recipients of a benefit

- the percentage reduction in pollution

- the amount of time saved

As is the case with qualitative information, quantitative benefits and costs can be used in two ways:

- On their own, they can illustrate the expected magnitude of a proposal by providing measurable figures to decision-makers.

- They can be used as a factor in developing cost estimates.

Quantitative analysis is an element of nearly all regulatory proposals that have a significant cost impact. It provides key metrics on the frequency or number of instances of an activity, and is essential for estimating benefits and costs. It can also be used on its own to illustrate the overall impact of a proposal in non-monetary terms. Although quantitative analysis is not required for proposals that have no cost impact or low cost impact, it is often included alongside qualitative information because it can be useful to decision-makers.

The following are examples of quantified benefits and costs identified in significant‑cost‑impact regulations that were finalized in 2018–19:

- Measures introduced under the Regulations Amending the Reduction of Carbon Dioxide Emissions from Coal-fired Generation of Electricity Regulations will reduce greenhouse gas emissions from electricity generation by 94 megatonnes of CO2e (carbon dioxide equivalent) between 2019 and 2055 versus the baseline scenario.

- Expanded biometrics under the Regulations Amending the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations could prevent, over 10 years, more than 1,440 foreign nationals with undisclosed criminality from entering Canada and up to 430 crimes. At the higher end of the risk spectrum, when factoring in the benefit of expanded information sharing with Migration 5 partners,Footnote 2 where there may be a greater variance in the criminal hit rate, it is estimated that up to 1,860 foreign nationals with undisclosed criminality will be prevented from entering Canada, resulting in close to 560 prevented crimes.

- The Prohibition of Asbestos and Products Containing Asbestos Regulations are expected to reduce the amount of asbestos and the number of products containing asbestos being imported into and used in Canada in the future. It is estimated that asbestos imports would be reduced by over 4,700 tonnes between 2019 and 2035. As a result, exposure to asbestos would decline over time and health benefits would be generated from avoided adverse health outcomes.

Monetized benefits and costs

Monetized benefits and costs are those that are expressed in a currency amount, such as dollars, using an approach that considers both the value of an impact and when it occurs.Footnote 3

An analysis of monetized costs and benefits is required for all regulatory proposals that have a significant cost impact. If the benefits or costs cannot be monetized, a rigorous qualitative analysis of the costs or benefits of the proposed regulation is required, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) must be satisfied that there are legitimate obstacles to monetizing the impacts. In practice, most regulatory proposals with significant cost impacts include both monetized benefits and costs as part of the analysis.

In order for costs and benefits to be considered monetized, the dollar values used in a CBA are adjusted so that values and prices that occur at different times are equal:

- to their exchange value (inflation adjustment)

- when they occur (discounting)

Of the 26 regulations with significant cost impacts that were finalized in 2018–19, 22 of them had monetized impacts, representing 11.5% of GIC regulations and 7.0% of all regulations. Of the 26:

- 17 had monetized benefits and costs

- 5 had monetized costs only

- 4 had quantified costs and benefits

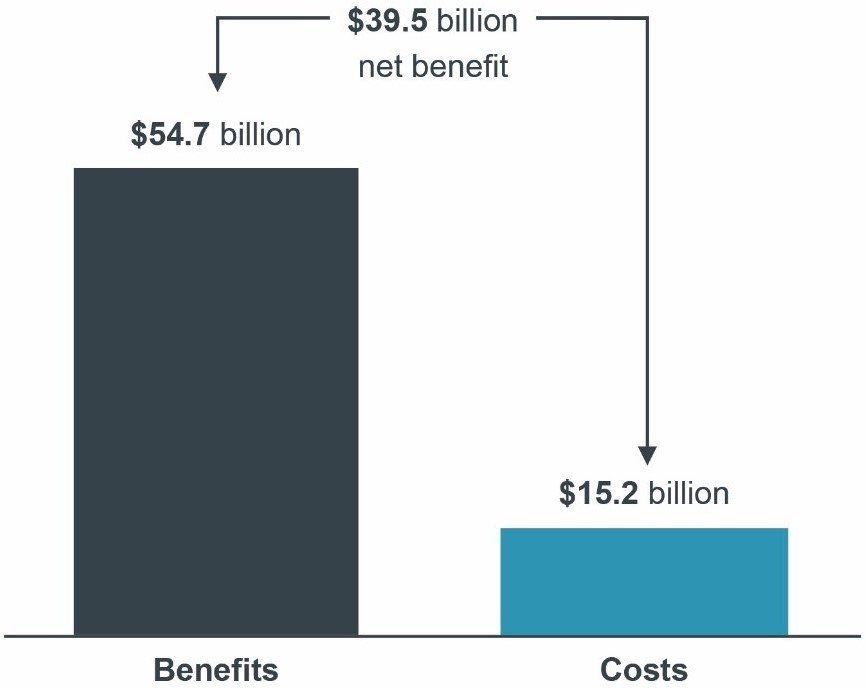

For the 17 regulations with significant cost impacts that had monetized estimates of both benefits and costs, expressed as total present value (see Figure 2):Footnote 4

- total benefits were $54,740,775,061

- total costs were $15,244,795,242

- net benefits were $39,495,979,818

Figure 2 - Text version

Figure 2 depicts the net benefit of significant-cost-impact regulations published during the 2018-19 fiscal year.

The total cost associated with significant-cost-impact regulations was $54.7 billion.

The total benefit associated with significant-cost-impact regulations was $15.2 billion.

The difference between the total cost and total benefit is a net benefit of $39.5 billion.

The following are examples of significant‑cost‑impact regulatory proposals that were finalized in 2018–19 and that had monetized benefits and costs:

- The Regulations Amending the Heavy-duty Vehicle and Engine Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations and Other Regulations Made Under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999,introduce:

- more stringent greenhouse gas emission standards for on-road heavy-duty vehicles and engines

- new greenhouse gas emission standards for trailers hauled by on-road transport tractors

The cumulative net benefits associated with measures in this regulation are estimated at $16.25 billion (net present value) for vehicles manufactured in model years 2020 to 2029.

- The Cannabis Regulations and associated regulatory changes establish:

- the rules and standards that apply to the authorized production, distribution, sale, importation and exportation of cannabis

- other related activities respecting the classes of cannabis that can be sold by a person authorized under the Cannabis Act

Most of the benefits are expected to come from the new Industrial Hemp Regulations, which streamline the regulatory approach to industrial hemp. The changes associated with the package will result in an estimated net benefit of $8.51 billion (net present value) from 2018 to 2028.

- The Regulations Respecting Reduction in the Release of Methane and Certain Volatile Organic Compounds (Upstream Oil and Gas Sector) introduce control measures to reduce fugitive and venting emissions of hydrocarbons from the upstream oil and gas sector. These measures are designed to meet Canada’s commitment to reduce methane emissions from the oil and gas sector by 40% to 45% of 2012 levels by 2025. Reducing Canadian greenhouse gas emissions will help limit increases in global average temperatures, contributing to Canada’s international obligations to combat climate change. In addition, because methane is a short-lived climate pollutant with significant near-term climate impacts, these reductions will contribute to slowing the rate of near-term global warming. The changes will result in a net benefit of $8.43 billion (net present value) from 2018 to 2035.

The purpose of CBA is to determine whether the expected benefits of a proposal are greater than the expected costs. This determination, however, is not based entirely on monetized benefits and costs. CBAs frequently include quantitative and qualitative analysis, in addition to monetized analysis, and the overall analysis must consider this broader range of evidence. In 2018–19:

- 3 regulations that had a significant cost impact had monetized costs that were equal to monetized benefits, a result that is usually associated with a direct transfer from one party to another

- 2 regulations that had a significant cost impact had monetized costs that were greater than monetized benefits

For detailed benefits and costs by regulation, see Appendix A.

Section 2: implementation of the one-for-one rule

The one-for-one rule

To comply with the annual reporting requirements of the Red Tape Reduction Act and the Policy on Limiting Regulatory Burden on Business, this report also provides an update on the implementation of the one-for-one rule.

The one-for-one rule, instituted in 2012–13, seeks to control the administrative burden that regulations impose on businesses.

Administrative burden includes:

- planning, collecting, processing and reporting of information

- completing forms

- retaining data required by the federal government to comply with a regulation

Under the rule, when a new or amended regulation increases the administrative burden on businesses, the cost of this burden must be offset through other regulatory changes. The rule also requires that an existing regulation be repealed each time a new regulation imposes new administrative burden on business.

The rule applies to all regulatory changes that impose new administrative burden on business. Under the Red Tape Reduction Regulations, the Treasury Board can exempt three categories of regulations from the requirement to offset burden and regulatory titles:

- regulations related to tax or tax administration

- regulations where there is no discretion regarding what is to be included in the regulation (for example, treaty obligations or the implementation of a court decision)

- regulations made in response to emergency, unique or exceptional circumstances, including where compliance with the rule would compromise the Canadian economy, public health or safety

Regulators are required to monetize and report on:

- the change in administrative burden

- feedback from stakeholders and Canadians on regulators’ estimates of administrative burden costs or savings to business

- the number of regulations created or removed

As with CBA, the dollar values used in estimating administrative burden are adjusted so that values and prices that occur at different times are equal in their exchange value (inflation adjustment) and when they occur (discounting). In this report, all figures related to the one‑for‑one rule are expressed in 2012 dollars to permit meaningful and consistent comparison of regulations, regardless of the fiscal year in which they were introduced.

In 2015, the Red Tape Reduction Act enshrined the existing policy requirement for the one‑for‑one rule in law. Section 9 of the Red Tape Reduction Act requires that the President of the Treasury Board prepare and make public an annual report on the application of the rule. The Policy on Limiting Regulatory Burden on Business further specifies that this report be tabled in Parliament.

The Red Tape Reduction Regulations state that the following must be included in the annual report:

- a summary of the increases and decreases in the cost of administrative burden that results from regulatory changes that are made in accordance with section 5 of the act within the 12‑month period ending on March 31 of the year in which the report is made public

- the number of regulations that are amended or repealed as a result of regulatory changes that are made in accordance with section 5 of the act within that 12-month period

Key findings on the implementation of the one-for-one rule

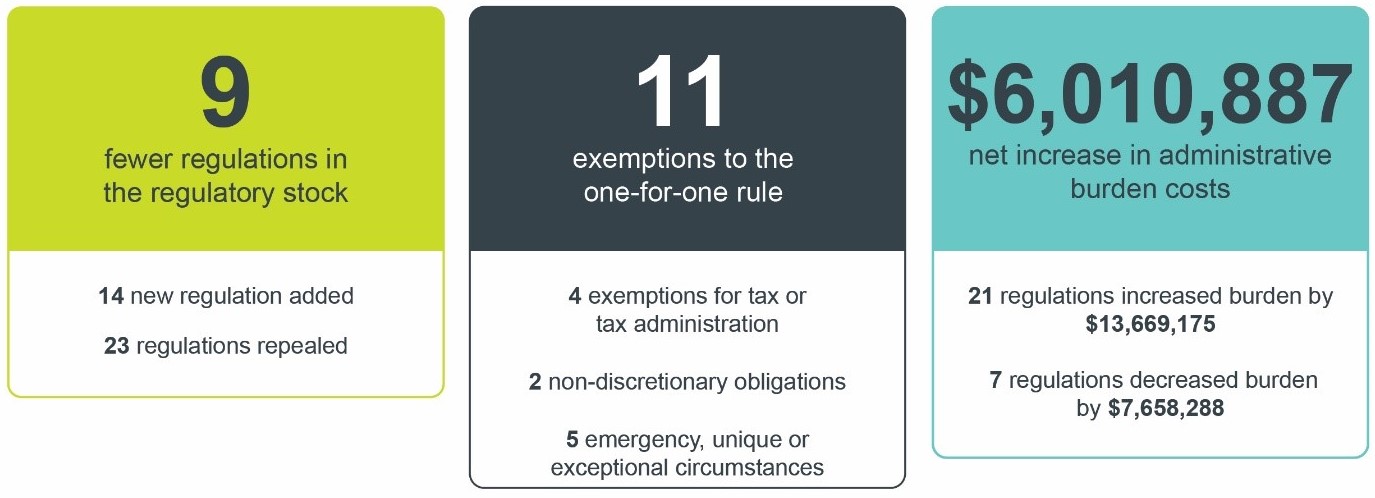

The main findings on changes in administrative burden and the overall number of regulations for 2018–19 are as follows:

- system-wide, the federal government remains in compliance with the requirement in the Red Tape Reduction Act to offset administrative burden and titles within 24 months

- net administrative burden increased by $6,010,887 in 2018–19; since 2012–13, approximately $24.33 million of net burden has been reduced

- 9 regulatory titles (net) were taken off the books, with a total net reduction of 144 titles since 2012–13Footnote 5

A detailed report on regulations that had implications under the one-for-one rule is in Appendix B.

Under the one-for-one rule, regulatory changes in 2018–19 resulted in the following increases and decreases in the cost of administrative burden on businesses:

- $13,669,175 of new burden introduced

- $7,658,288 of existing burden removed

- net increase of $6,010,887

While there was an overall addition to the burden over the course of the year, the rule allows individual portfolios 2 years to offset this burden. As well, portfolios are allowed to bank burden reductions for future offsets within that portfolio. As a result, most of the $13,669,175 in new burden introduced in 2018–19 has already been offset:

- $10,956,130 was offset immediately by previously removed burden

- $237,000 was offset by subsequent changes in 2018–19

- $2,476,045 had not yet been offset as of March 31, 2019

The changes introduced by the following three final regulations represented the largest increases and the largest decrease in administrative burden in 2018‒19:

- The Safe Food for Canadians Regulations (SOR/2018-108) establish consistent, prevention‑focused requirements for food that is imported or prepared for export or interprovincial trade, and include some requirements applicable to food that is traded intraprovincially. The regulations consolidate 13 food commodity-based regulations plus the food-related provisions of the Consumer Packaging and Labelling Regulations into a single regulation that, by taking an outcome-based approach, maintains high standards for health and safety while providing flexibility for industry to innovate and compete globally. Some requirements for certain food sectors will be phased in according to business size and industry readiness. Due to the flexibility the outcome-based regulatory approach provides, industry must keep records for food safety verification. This is the main reason for the annual incremental administrative burden on business of $9,148,276.

- The Regulations Amending the Canadian Aviation Regulations (Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems) (SOR/2019-11) create a predictable and flexible regulatory environment for remote aircraft (drones) while reducing the administrative burden on businesses. They also ensure that pilots have a relevant knowledge base. The changes represent a reduction in annual administrative burden on business of $5,838,321.

- The Regulations Respecting Reduction in the Release of Methane and Certain Volatile Organic Compounds (Upstream Oil and Gas Sector) (SOR/2018-66) introduce control measures to reduce fugitive and venting emissions of hydrocarbons from the upstream oil and gas sector. These changes are designed to meet Canada’s commitment to reduce methane emissions from the oil and gas sector by 40% to 45% of 2012 levels by 2025. This will reduce Canadian greenhouse gas emissions and help limit increases in global average temperatures, contributing to Canada’s international obligations to combat climate change. In addition, because methane is a short-lived climate pollutant with significant near-term climate impacts, these reductions will contribute to slowing the rate of near-term global warming. The regulations add $1,791,333 in annual administrative burden on business.

Under the one-for-one rule, regulatory changes in 2018–19 resulted in the following increases and decreases in the stock of federal regulations:

- 8 new regulatory titles imposing administrative burden on business were introduced

- 5 regulatory titles were repealed

- 18 existing titles were repealed and replaced with 6 new titles

While 8 new titles were introduced over the course of the year, the rule allows individual portfolios 2 years to offset these titles. As is the case with administrative burden, portfolios are allowed to bank title repeals for future offsets within the portfolio. As a result, most of these 8 new titles have already been offset:

- 5 were offset immediately by previously removed titles

- 1 was offset by subsequent repeals in 2018‒2019

- 2 had not yet been offset as of

The Treasury Board monitors regulators’ compliance with the requirement to offset new administrative burden and titles. System-wide, the federal government remains in compliance with the requirement in the Red Tape Reduction Act to offset added new administrative burden and titles within 24 months.

TBS also tracks offsetting requirements by portfolio. The following instances of non-compliance with the requirements occurred in 2018–19:

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada has an outstanding balance of $258,490, related primarily to the Aquaculture Activities Regulations (SOR/2015-177), which were registered on . This situation was reported in the 2017 to 2018 Report to Parliament, and officials from TBS and from Fisheries and Oceans Canada continue to work together to identify offsets that will balance this account.

- Transport Canada was briefly in non-compliance when it exceeded the 2‑year deadline to offset burden introduced under the Prevention and Control of Fires on Line Works Regulations (SOR/2016-317). The offset was achieved 6 days later, on , when the Regulations Amending the Canadian Aviation Regulations (Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems) (SOR/2019-11) were registered. The portfolio finished the fiscal year in full compliance.

In 2018–19, the Treasury Board approved the exemption of 11 regulations from the requirement to offset burden and titles:

- 4 were related to tax and tax administration

- 2 were related to non-discretionary obligations

- 5 were related to emergency, unique or exceptional circumstances

The Treasury Board retroactively granted the Finance portfolio an exemption for the Regulations Amending Certain Regulations Made Under the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act, 2016 (SOR/2016-153), which were registered on . These regulations implemented measures required by the Financial Action Task Force, an international organization that develops and promotes policies at the national and international levels to combat money laundering and terrorist financing. The Treasury Board agreed that, as a member of the task force, Canada had no discretion over the introduction of the regulation.

Figure 3 - Text version

Figure 3 provides statistics on the implementation of the one-for-one rule for regulations published in the 2018-19 fiscal year.

There were 14 new regulatory titles added to the regulatory stock and 23 regulatory titles repealed, for a net of 9 fewer regulations in the regulatory stock.

There were 11 instances where regulations were exempted from the one-for-one rule, including 5 emergency, unique or exceptional circumstances situations, 4 exemptions for tax and tax administration, and 2 non-discretionary obligations.

In total, 21 regulations increased administrative burden by $13,669,175, and 7 regulations decreased administrative burden by $7,658,288, for a net increase of $6,010,887 in administrative burden costs.

Section 3: update on the Administrative Burden Baseline

The Administrative Burden Baseline

The Administrative Burden Baseline (ABB) provides Canadians with a count of the total number of administrative requirements in federal regulations (GIC and non-GIC) and associated forms.

The ABB was first publicly reported on in , providing a baseline count of administrative requirements by regulator. Since then, regulators continue to:

- do a count of their administrative requirements occurring from July 1 to June 30 each year

- publicly post updates to their ABB count by September 30 each year

Key findings on the Administrative Burden Baseline

The baseline provides Canadians with information on 38 regulators.

As of :

- the total number of administrative requirements was 136,379, an increase of 258 (or 0.19%) from the 2017 count of 136,121

- there were 585 regulations identified by regulators as having administrative requirements, an increase of 5 from the 2017 figure of 580

- the average number of administrative requirements per regulation was 233, down from the 2017 average of 235

The top three changes in the ABB in 2018 were:

- The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission reduced its count by 1,162 requirements (from 8,169 to 7,007) as a result of a change in counting methodology. In evaluating its methodology, it concluded that assumptions made in the past had resulted in an overstatement of the baseline.

- Health Canada’s requirements increased by 596 (from 15,283 to 15,879). This increase is a result of design and other changes to forms under the Food and Drug Regulations, the 2017 regulatory changes made to address antimicrobial resistance, and the implementation of the low‑risk veterinary health products notification program.

- The National Energy Board’s requirements increased by 527 (from 4,012 to 4,539) as a result of updates to the web‑based Online Event Reporting System (OERS), which includes two new online reporting forms (Suspension of Consent and Damage to Pipe). The OERS provides companies with greater clarity and efficiency in reporting and provides a single window for reporting events to the National Energy Board and the Transportation Safety Board (as applicable).

A detailed summary of the ABB count for 2018 and for previous years is in Appendix C.

Appendix A: detailed report on cost-benefit analyses for 2018–19

Figures in this appendix are taken from the RIASs in final federal regulations published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, in 2018–19. To remove the effect of inflation, figures are expressed in 2012 dollars and vary from those published in the RIASs.

Table A1 shows, regulatory proposals finalized in 2018–19 that had significant cost impacts and that included both monetized benefits and monetized costs. These proposals may also include quantitative and qualitative data from a cost‑benefit analysis (CBA) to supplement the monetized CBA.

| Department or agency | Regulation | Benefits (total present value) | Costs (total present value) | Net present value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laurentian Pilotage Authority | Regulations Amending the Laurentian Pilotage Tariff Regulations (SOR/2018-52) (medium impact) | $11,773,651 | $11,773,651 | $0 |

| Pacific Pilotage Authority | Regulations Amending the Pacific Pilotage Tariff Regulations (SOR/2018-53) (medium impact) | $30,067,984 | $30,067,984 | $0 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Regulations Respecting Reduction in the Release of Methane and Certain Volatile Organic Compounds (Upstream Oil and Gas Sector) (SOR/2018-66) (high impact) | $12,131,320,155 | $3,697,227,132 | $8,434,093,023 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Regulations Amending the Heavy-duty Vehicle and Engine Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations and Other Regulations Made Under the Canadian Environmental rotection Act, 1999 (SOR/2018-98) (high impact) | $21,798,698,568 | $5,544,824,416 | $16,253,874,152 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Regulations Amending the Metal Mining Effluent Regulations (SOR/2018-99) (medium impact) | $8,868,062 | $54,246,124 | -$45,378,062 |

| Canadian Food Inspection Agency | Safe Food for Canadians Regulations (SOR/2018-108) (high impact) | $934,600,000 | $896,500,000 | $38,100,000 |

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | Regulations Amending the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations (SOR/2018-128) (high impact) | $152,077,237 | $113,484,772 | $38,592,465 |

| Health Canada | Cannabis Regulations (SOR/2018-144) (high impact) Includes the following: |

$9,224,637,501 | $718,646,424 | $8,505,991,077 |

| Natural Resources Canada | Regulations Amending the Energy Efficiency Regulations, 2016 (SOR/2018-201) (high impact) | $5,497,133,595 | $1,149,272,135 | $4,347,861,460 |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada | Trademarks Regulations (SOR/2018-227) (medium impact) | $67,544,188 | $66,601,375 | $942,813 |

| Transport Canada | Regulations Respecting Compulsory Insurance for Ships Carrying Passengers (SOR/2018-245) (medium impact) | $24,179,047 | $24,179,047 | $0 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Regulations Amending the Reduction of Carbon Dioxide Emissions from Coal-fired Generation of Electricity Regulations (SOR/2018-263) (medium impact) | $4,341,099,617 | $2,404,157,854 | $1,936,941,762 |

| Transport Canada | Regulations Amending the Canadian Aviation Regulations (Parts I, VI and VII — Flight Crew Member Hours of Work and Rest Periods) (SOR/2018-269) (high impact) | $386,211,856 | $375,221,631 | $10,990,225 |

| Transport Canada | Regulations Amending the Canadian Aviation Regulations (Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems) (SOR/2019-11) (high impact) | $132,563,600 | $158,592,697 | -$26,029,097 |

| Total | $54,740,775,061 | $15,244,795,242 | $39,495,979,818 | |

Table A2 shows regulatory proposals finalized in 2018–19 that had significant cost impacts and that included monetized costs only. Under the previous Cabinet Directive on Regulatory Management, medium-impact proposals could express benefits in quantitative or qualitative terms in situations where it was impractical to monetize those benefits. Similarly, under the new Cabinet Directive on Regulation, if it is not possible to quantify the benefits or costs of a proposal that has significant cost impacts, a rigorous qualitative analysis of costs or benefits of the proposed regulation is required, with the concurrence of TBS.

| Department or agency | Regulation | Costs (total present value) |

|---|---|---|

| Health Canada | Regulations Amending the Food and Drug Regulations (Opioids) (SOR/2018-77) (medium impact) | $71,361,896 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Prohibition of Asbestos and Products Containing Asbestos Regulations (SOR/2018-196) (medium impact) Includes Regulations Repealing the Asbestos Products Regulations (SOR/2018-197) |

$73,586,047 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Regulations Amending the Metal and Diamond Mining Effluent Regulations (SOR/2018-280) (medium impact) | $12,839,488 |

| Great Lakes Pilotage Authority | Regulations Amending the Great Lakes Pilotage Tariff Regulations (SOR/2019-56) (significant cost impact) | $9,189,405 |

| Total | $166,976,836 | |

Table A3 shows regulatory proposals finalized in 2018–19 that had significant cost impacts and that did not include monetized benefits and costs.

| Department or agency | Regulation |

|---|---|

| Employment and Social Development Canada | Regulations Amending the Employment Insurance Regulations (Pilot Project No. 21)(SOR/2018-228) (high impact) |

| Public Services and Procurement Canada (Canada Post) | Regulations Amending the Letter Mail Regulations(SOR/2018-272) (high impact) Includes the following: |

Appendix B: detailed report on the one-for-one rule for 2018–19

| Department or agency | Regulation | Publication date | Net burden in | Net burden out | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canadian Food Inspection Agency (Health Portfolio) | Safe Food for Canadians Regulations (SOR/2018-108) | June 13, 2018 | $9,148,276 | $0 | |

| Canadian Food Inspection Agency (Agriculture Portfolio) | Regulations Amending the Health of Animals Regulations (SOR/2019-38) | February 20, 2019 | $299,062 | $0 | |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Regulations Respecting Reduction in the Release of Methane and Certain Volatile Organic Compounds (Upstream Oil and Gas Sector) (SOR/2018-66) | April 26, 2018 | $1,791,333 | $0 | |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Regulations Amending the Wild Animal and Plant Trade Regulations (SOR/2018-81) |

May 2, 2018 | $2,279 | $0 | |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Regulations Amending the Heavy‑duty Vehicle and Engine Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations and Other Regulations Made Under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (SOR/2018‑98) | May 30, 2018 | $13,835 | $0 | |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Regulations Amending the Metal Mining Effluent Regulations (SOR/2018‑99) | May 30, 2018 | $3,937 | $0 | |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Order Amending Schedule 1 to the Species at Risk Act(SOR/2018‑112) | June 13, 2018 | $975 | $0 | |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Order Amending Schedule 3 to the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (SOR/2018-193) | October 17, 2018 | $0 | $111 | |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Prohibition of Asbestos and Products Containing Asbestos Regulations (SOR/2018-196) | October 17, 2018 | $12,624 | $0 | |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Notice Establishing Criteria Respecting Facilities and Persons and Publishing Measures(SOR/2018‑213) Includes Greenhouse Gas Emissions Information Production Order (SOR/2018‑214) | October 31, 2018 | $526,257 | $0 | |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Regulations Limiting the Carbon Dioxide Emissions from Natural Gas-fired Generation of Electricity (SOR/2018-261) | December 12, 2018 | $10,752 | $0 | |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Environmental Emergency Regulations, 2019 (SOR/2019-51) | March 6, 2019 | $112,850 | $0 | |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Order Amending Schedule 1 to the Species at Risk Act (SOR/2019-52) | March 6, 2019 | $292 | $0 | |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canadian Coast Guard | Regulations Amending the Marine Mammal Regulations(SOR/2018-126) | July 11, 2018 | $738 | $0 | |

| Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard | Banc-des-Américains Marine Protected Area Regulations (SOR/2019-50) | March 6, 2019 | $173 | $0 | |

| Health Canada | Regulations Amending the Food and Drug Regulations and the Regulations Amending the Food and Drug Regulations (DIN Requirements for Drugs Listed in Schedule C to the Food and Drugs Act that are in Dosage Form) (SOR/2018-84) |

May 2, 2018 | $818,111 | $0 | |

| Health Canada | Cannabis Regulations(SOR/2018‑144) | July 11, 2018 | $420,599 | $0 | |

| Health Canada | Industrial Hemp Regulations (SOR/2018-145) |

July 11, 2018 | $25,675 | $0 | |

| Health Canada | Regulations Amending and Repealing Certain Regulations Made Under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (SOR/2018-147) | July 11, 2018 | $0 | $746,178 | |

| Health Canada | Regulations for the Monitoring of Medical Assistance in Dying (SOR/2018-166) | August 8, 2018 | $66,511 | $0 | |

| Health Canada | Cannabis Tracking System Order (SOR/2018‑178) | September 5, 2018 | $174,200 | $0 | |

| Health Canada | Regulations Amending the Tobacco Reporting Regulations (SOR/2019-064) | March 20, 2019 | $3,696 | $0 | |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development | Industrial Design Regulations (SOR/2018-120) |

June 27, 2018 | $0 | $12,870 | |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development | Trademarks Regulations (SOR/2018-227) |

November 14, 2018 | $0 | $384,867 | |

| Natural Resources Canada | Regulations Amending the Energy Efficiency Regulations, 2016 (SOR/2018‑201) | October 31, 2018 | $0 | $543,896 | |

| Transport Canada | Regulations Amending the Explosives Regulations, 2013 (SOR/2018-231) Includes Regulations Amending the Cargo, Fumigation and Tackle Regulations(SOR/2018-233) | November 14, 2018 | $0 | $132,045 | |

| Transport Canada | Regulations Amending the Canadian Aviation Regulations (Parts I and X - Greenhouse Gas Emissions from International Aviation - CORSIA) (SOR/2018-240) | November 28, 2018 | $237,000 | $0 | |

| Transport Canada | Regulations Amending the Canadian Aviation Regulations (Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems) (SOR/2019‑11) | January 9, 2019 | $0 | $5,838,321 | |

| $13,669,175 | $7,658,288 | ||||

| Net change in administrative burden | $6,010,887 | ||||

| Department or agency | Regulation | Net title change |

|---|---|---|

| New regulatory titles that have administrative burden | ||

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Regulations Respecting Reduction in the Release of Methane and Certain Volatile Organic Compounds (Upstream Oil and Gas Sector)(SOR/2018-66) | 1 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Notice Establishing the Criteria Respecting Facilities and Persons and Publishing Measures (SOR/2018-213) | 1 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Greenhouse Gas Emissions Information Production Order (SOR/2018-214) | 1 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Regulations Limiting the Carbon Dioxide Emissions from Natural Gas-fired Generation of Electricity (SOR/2018-261) | 1 |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | Banc-des-Américains Marine Protected Area Regulations (SOR/2019-50) | 1 |

| Health Canada | Cannabis Regulations(SOR/2018-144) Note: elements of this new title replaced activities previously under the Access to Cannabis for Medical Purposes Regulations (SOR/2016-230), which were repealed by Regulations Amending and Repealing Certain Regulations Made Under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (SOR/2018-147). However, the Cannabis Regulations contain a number of other completely new provisions. As a result, the transaction is not a clean repeal‑and‑replace, even though the net impact is zero titles. | 1 |

| Health Canada | Regulations for the Monitoring of Medical Assistance in Dying (SOR/2018-166) | 1 |

| Health Canada | Cannabis Tracking System Order (SOR/2018-178) | 1 |

| Subtotal | 8 | |

| Repealed regulatory titles | ||

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Regulations Repealing the Chlor-Alkali Mercury Liquid Effluent Regulations (SOR/2018-80) repealed:

|

(1) |

| Health Canada | Regulations Amending and Repealing Certain Regulations Made Under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (SOR/2018-147) repealed:

|

(1) |

| Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada | Order Repealing the Dakota Tipi Band Council Elections Order (SOR/2018-155) repealed:

|

(1) |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada | Regulations Repealing the Telecommunications Apparatus Regulations (Miscellaneous Program) (SOR/2018-62) repealed:

|

(1) |

| Transport Canada | Regulations Amending the Marine Personnel Regulations and Repealing the Tariff of Fees of Shipping Masters (SOR/2019-66) repealed:

|

(1) |

| Subtotal | (5) | |

| New regulatory titles that simultaneously repealed and replaced existing titles | ||

| Canadian Food Inspection Agency | Safe Food for Canadians Regulations (SOR/2018-108) replaced:

|

(12) |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Environmental Emergency Regulations, 2019(SOR/2019-51) replaced:

|

0 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Prohibition of Asbestos and Products Containing Asbestos Regulations (SOR/2018-196) replaced:

|

0 |

| Health Canada | Industrial Hemp Regulations (SOR/2018-145) replaced:

|

0 |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada | Industrial Design Regulations (SOR/2018-120) replaced:

|

0 |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada | Trademarks Regulations (SOR/2018-227) replaced:

|

0 |

| Subtotal | (12) | |

| Total net impact on regulatory stock in 2018–19 | (9) | |

| Department or agency | Regulations | Publication date | Exemption type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Department of Finance Canada | United States Surtax Remission Order (SOR/2018‑205) | October 31, 2018 | Tax or tax administration |

| Department of Finance Canada | In-Transit Steel Goods Remission Order (SOR/2018‑288) | December 26, 2018 | Tax or tax administration |

| Department of Finance Canada | Order Amending the United States Surtax Remission Order (SOR/2018-205) (SOR/2018-289) | December 26, 2018 | Tax or tax administration |

| Department of Finance Canada | Mexico Steel Goods Remission Order (SOR/2019‑36) | February 20, 2019 | Tax or tax administration |

| Global Affairs Canada | Regulations Amending the Regulations Implementing the United Nations Resolutions on Libya (SOR/2018‑101) | May 30, 2018 | Non-discretionary obligation |

| Global Affairs Canada | Regulations Amending the Special Economic Measures (Venezuela) Regulations (SOR/2018‑114) | June 13, 2018 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Global Affairs Canada | Regulations Amending the Special Economic Measures (Burma) Regulations (SOR/2018-135) | July 11, 2018 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Global Affairs Canada | Regulations Implementing the United Nations Resolutions on Mali (SOR/2018-203) | October 31, 2018 | Non-discretionary obligation |

| Global Affairs Canada | Regulations Amending the Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Regulations (SOR/2018-259) | December 12, 2018 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness | Regulations Amending the Regulations Establishing a List of Entities(SOR/2018-103) | May 30, 2018 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness | Regulations Amending the Regulations Establishing a List of Entities (SOR/2019-45) | February 20, 2019 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Department or agency | Regulation | Net impact on regulatory stock |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Finance Canada | The Complaints (Banks, Authorized Foreign Banks and External Complaints Bodies) Regulations (SOR/2013-048) replacedthe Complaint Information (Authorized Foreign Banks) Regulations (SOR/2001-370) and the Complaint Information (Banks) Regulations (SOR/2001-371) but the title count did not reflect the net 1 title out that resulted from 2 title repeals and 1 new title introduced. | (1) |

| Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada | The Order Repealing the Eskasoni Band Council Elections Order (SOR/2016-224) repealed the Eskasoni Band Council Elections Order (SOR/2004-105) and eplaced the authorities via the Order Amending the Schedule to the First Nations Elections Act (Eskasoni) (SOR/2016-225). Since the replacement authorities are introduced through an amendment, the result is net 1 title out. | (1) |

| Department of Finance Canada | The Canada Post Corporation Pension Plan Funding Regulations (SOR/2014-38) include an automatic repeal mechanism effective 3 years after registration. The regulations introduce no administrative burden on business, but the repeal qualifies as a title out that was not counted. | (1) |

| Global Affairs Canada | The Regulations Repealing the United Nations Sierra Leone Regulations (SOR/2013-159) repealed the United Nations Sierra Leone Regulations (SOR/98-400) but did not count the title out. | (1) |

Appendix C: administrative burden count

| Department or agencytable C1 note * | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Requirements | Regulations | Requirements | Regulations | Requirements | Regulations | Requirements | Regulations | |

Table C1 Notes

|

||||||||

| Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada | 134 | 4 | 133 | 4 | 133 | 4 | 133 | 4 |

| Canada Border Services Agency | 1,470 | 30 | 1,473 | 30 | 1,473 | 30 | 1,473 | 30 |

| Canada Revenue Agency | 1,776 | 30 | 1,807 | 31 | 1,807 | 30 | 1,808 | 31 |

| Canadian Dairy Commission | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency | 89 | 1 | 89 | 1 | 89 | 1 | 89 | 1 |

| Canadian Food Inspection Agency | 11,021 | 13 | 11,880 | 23 | 12,047 | 21 | 12,075 | 23 |

| Canadian Grain Commission | 1,056 | 1 | 1,056 | 1 | 1,056 | 1 | 1,056 | 1 |

| Canadian Heritage | 798 | 3 | 802 | 3 | 802 | 3 | 700 | 3 |

| Canadian Intellectual Property Office | 568 | 6 | 568 | 6 | 568 | 6 | 543 | 5 |

| Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission | 8,169 | 10 | 8,169 | 10 | 8,169 | 10 | 7,007 | 10 |

| Canadian Pari-Mutuel Agency | 731 | 2 | 731 | 2 | 731 | 2 | 731 | 2 |

| Canadian Transportation Agency | 545 | 7 | 545 | 7 | 545 | 7 | 545 | 7 |

| Competition Bureau Canada | 444 | 3 | 444 | 3 | 444 | 3 | 444 | 3 |

| Copyright Board Canada | 16 | 1 | 17 | 1 | 17 | 1 | 17 | 1 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | 3,256 | 7 | 3,104 | 7 | 3,100 | 6 | 3,102 | 6 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | 10,099 | 53 | 11,500 | 53 | 11,515 | 52 | 11,390 | 51 |

| Farm Products Council of Canada | 47 | 3 | 47 | 3 | 47 | 3 | 47 | 3 |

| Department of Finance Canada | 1,891 | 42 | 1,919 | 42 | 1,928 | 42 | 1,928 | 42 |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | 5,350 | 31 | 5,446 | 31 | 5,367 | 30 | 5,367 | 30 |

| Global Affairs Canada | 2,820 | 58 | 2,784 | 57 | 2,774 | 56 | 2,896 | 60 |

| Health Canada | 15,945 | 32 | 15,627 | 31 | 15,283 | 31 | 15,879 | 31 |

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | 73 | 1 | 59 | 1 | 59 | 1 | 59 | 1 |

| Indian and Northern Affairs Canada | 288 | 11 | 288 | 11 | 288 | 12 | 288 | 12 |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada | 1,904 | 8 | 1,330 | 7 | 1,332 | 7 | 1,415 | 8 |

| Labour Program | 21,468 | 17 | 21,791 | 17 | 21,791 | 17 | 22,081 | 17 |

| Measurement Canada | 359 | 2 | 359 | 2 | 359 | 2 | 359 | 2 |

| National Energy Board | 1,298 | 14 | 4,012 | 13 | 4,012 | 13 | 4,539 | 13 |

| Natural Resources Canada | 4,507 | 28 | 4,507 | 28 | 4,432 | 28 | 4,312 | 26 |

| Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy Canada | 799 | 3 | 799 | 3 | 799 | 3 | 799 | 3 |

| Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada | 2,875 | 33 | 2,899 | 33 | 2,586 | 23 | 2591 | 23 |

| Parks Canada | 773 | 25 | 773 | 25 | 773 | 25 | 773 | 25 |

| Patented Medicine Prices Review Board Canada | 59 | 1 | 59 | 1 | 59 | 1 | 59 | 1 |

| Public Health Agency of Canada | 42 | 2 | 173 | 2 | 189 | 2 | 189 | 2 |

| Public Safety Canada | 229 | 6 | 229 | 6 | 229 | 6 | 229 | 6 |

| Public Services and Procurement Canada | 388 | 1 | 493 | 1 | 498 | 1 | 498 | 1 |

| Statistics Canada | 157 | 1 | 157 | 1 | 157 | 1 | 157 | 1 |

| Transport Canada | 30,258 | 94 | 30,458 | 98 | 30,611 | 95 | 30,749 | 96 |

| Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat | 48 | 2 | 48 | 2 | 48 | 2 | 48 | 2 |

| Total | 131,754 | 588 | 136,579 | 599 | 136,121 | 580 | 136,379 | 585 |

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the President of the Treasury Board, 2019, ISSN: 2561-4290