Evaluation of the Performance Management Program for Executives

On this page

- Introduction

- Preamble

- Role of the Performance Management Program for Executives and its Context

- Program Background

- Evaluation Methodology and Scope

- Limitation of the Evaluation

- Literature and Jurisdictional Reviews

- Findings

- Lessons and Alternatives

- Recommendations

- Appendix A: Logic Model for the Performance Management Program

- Appendix B: Methodology and Analysis of Public Service Employee Survey Data

- Appendix C: Management Response and Action Plan

Introduction

This document presents the results of an evaluation of the Performance Management Program for Executives (EXPMP) which is managed within the Office of the Chief Human Resource Officer (OCHRO) at Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS). The evaluation was undertaken by the Internal Audit and Evaluation Bureau (IAEB) at TBS, with the assistance of Goss Gilroy Inc. It was conducted in accordance with the Treasury Board (TB) Policy on Results.

The evaluation assessed the effectiveness of the EXPMP, with an emphasis on the immediate and intermediate outcomes of the program. The evaluation was undertaken between January and August 2020 and covered the period from fiscal year 2014-2015 to 2018-2019.

Preamble

The EXPMP is meeting its intended outcomes to some extent and has been effective in a number of ways. For example, the HR function is equipped to deliver EXPMP advice and guidance to managers and employees, over 90% of employees and managers participate in all steps of the performance management process to some extent; however, areas exist that detract from stronger program performance. Moreover, the values, “fair and consistent” and “equitable and transparent,” in the governing policy instruments were not uniformly experienced in the EXPMP, evaluation findings show. And when viewed alongside the federal government’s strategic priorities (the future of work, digital, open and transparent government, and diversity and inclusion) the overall EXPMP performance and relevance are further strained. As the literature and other jurisdictions reveal, to avert attrition and loss of an executive’s trust, it is necessary for a performance management program to:

- Be able to respond to users’ needs, now and in the future

- Offer simple, fair and transparent approaches to assessment

- Reward and recognize performance in ways that respond to today’s workforce and context, taking into account private sector compensation

- Reflect the values of the public service and people management policy instruments.

Since the mid-2000s, more organizations and jurisdictions have moved away from strictly traditional performance management models of accountability and reward. This is not surprising given the changing nature of work. A literature review shows that some companies are moving away from formal appraisals. Public sector examples include Ontario which does not use performance pay; the British Columbia public service where all employees have access to a coaching service; and a federal agency in which performance pay has been removed from its performance management program. Alternate approaches to EX performance management in the context of total compensation will be useful to examine, given the changing work environment, the shifting demographics of the federal public service and the values that underpin them.

While the assessment of public service salaries and executive compensation decisions are informed by market rates, the link between performance and compensation of executives in the public service is tenuous. Assessing work objectives and finding appropriate “measures” is a challenge for reasons that include the following:

- The public sector work environment is ambiguous, work is often not quantifiable and does not result in profit gains or losses. Unlike the private sector, public sector executive work is difficult to monetize.

- Public sector work environments have become flatter and more collaborative, making it difficult to identify individual “results.”

- Executives in the federal public service are highly mobile, with performance assessments that may span more than one ministerial mandate commitment, supervisor or organization.

Aside from assessing work objectives, competency assessment is a skill that can be affected by:

- The relationship between supervisor and employee

- The supervisor’s aim to maintain a positive appearance

- Discomfort providing negative feedback

- A desire to avoid the administrative burden of poor performance (i.e. action planning)

- Organizational ‘norms’ like rating bell-curves and Succeeded- ratings for new appointees

- Opaque internal review mechanisms

Under these conditions, objective performance assessments based on a scale that leads to performance pay, is an inexact exercise.

Against this backdrop and despite some areas of program strength, the evaluation findings reveal issues of an IT system that controls the process rather than serving the user. It is time-consuming, unresponsive and frustrating rather than being simple and user-friendly, and facilitating important conversations between people.

The findings also show that departmental approaches to determining ratings cast doubt on how decisions are made and how they are prone to being influenced by bell curves, departmental performance pay budgets and review committee mechanisms. The approaches can also lack transparency regarding the relative weight of work objectives versus key leadership competencies. Feedback and coaching are variable and depend on the supervisor’s time and comfort with constructive feedback or willingness to engage in administrative processes when significant improvement is needed. The evaluation findings have helped to illuminate some of the assumptions on which the EXPMP is based, and the biases that have seeped into the process.

The EXPMP has many components: the ETMS (the IT system that underpins the program), supervisor feedback, ratings, review mechanisms and performance pay must all work together to arrive at a conclusion for each executive. The evaluation findings show that this complexity does not meet the needs of either supervising executives or executive employees in some important areas. Although the evaluation did not examine the relevance of the EXPMP, the findings reflect a story that puts the program’s relevance in question.

Role of the Performance Management Program for Executives and its Context

The federal public service undertakes complex and diverse work developing policy and delivering programs and services to Canadians. The effective management of people is recognized as a cornerstone of a high performing public service and a key enabler in building Canadians’ trust in and satisfaction with government.

People management is an integral part of achieving operational objectives and requires sustained leadership and investment of time and resources. It also requires the engagement of managers, employees, human resources practitioners, central organizations, and bargaining agents.

Performance management is a key aspect of people management. It is a tool for managing the work performance and productivity of individuals, teams and organizations. It responds to organizational priorities, budgetary and fiscal pressures, increasing demands for public services. Performance management is also intended to build and maintain trust between employer and employee and to create conditions to allow all employees to maximize their contributions and provide world-class services to Canadians.Footnote 1

OCHRO establishes the policy instruments and the IT infrastructure for performance management and monitoring and reporting. In addition, OCHRO provides policy interpretation and program advice and guidance. The effectiveness of performance management is driven via three key stakeholders:

- Deputy Heads who are accountable for the performance management of the employees in their organizations.

- Managers who are accountable for employee performance.

- The Human Resources function which delivers services and support to Deputy Heads and managers to enable performance management in organizations.

Program Background

In this section

Program Description

Executive performance management in the public service is governed by the Policy on People Management, the Policy on the Management of Executives, the Directive on Performance and Talent Management for Executives and the Directive on Terms and Conditions of Employment for Executives.Footnote 2

The objective of these policy instruments is to support excellence in people management to enable a high-performing public service. The EXPMP encourages excellence by setting clear objectives, establishing behavioural expectations (competencies), evaluating achievement of results and demonstration of competencies, recognizing and rewarding performance, and providing a framework for consistency in performance management.

The directive also sets out the responsibilities of deputy heads, or their delegates, regarding the administration of a consistent, equitable and rigorous approach to performance management across the core public administration.

The table below outlines key aspects of the performance management policy instruments for Executives.

| Application |

Applies to excluded positions in the core public administration for the following groups and levels:

|

|---|---|

| Compensation |

Individual executive compensation is determined in recognition that compensation is a reflection of performance and contribution. Performance-based compensation may be in the form of at-risk pay, in-range salary movement (increments within a salary range) and revision of a salary range. Executives who have achieved exceptional results against all commitments and who have truly demonstrated the Key Leadership Competencies may also receive a bonus. Executives at the EX-01 to EX-03 levels may receive at-risk pay of up to 12 per cent of their base salary and a bonus of up to 3 per cent. Executives at the EX-04 and EX-05 levels may receive at-risk pay of up to 20 per cent of their base salary and a bonus of up to 6 per cent. |

| Rating Scale |

Executive performance is assessed against both work objectives (Ongoing and Key Commitments) and competencies (Key Leadership Competencies). The extent to which executives meet work objectives in the ETMS is directly assessed. The system allows managers of executives to formally identify achievement of work results against written work objectives. The extent to which executives meet key leadership competencies is also submitted to the ETMS through a narrative submission written by an executive’s manager. A detailed description of Key Leadership Competency profile and examples of effective and ineffective behaviours is available on the TBS website. Executives do not receive separate performance ratings for work objectives and competencies. They receive one rating at the end of the year using the following scale: Level 1 (Did Not Meet); Level 2 (Succeeded-); Level 3 (Succeeded); Level 4 (Succeeded+) and Level 5 (Surpassed). |

| Performance Agreements |

Performance agreements need to be in place at the beginning of the cycle to identify individual development priorities, including the development of Key Leadership Competencies. Revisions to the agreements can be made throughout the fiscal year to the performance agreement, dictated by such factors as changed priorities. |

| Documentation |

Executive Talent Management System (ETMS) – The web application which integrates executive performance and talent management, and performance-based compensation administration (budget module). It includes a performance agreement module with documentation on performance objectives and measures and the achievement of results, including the demonstration of the Key Leadership Competencies. |

The policy framework for executives relies on an annual cycle with specific check points, as well as on-going activities.

Roles and Responsibilities

According to the Policy Framework for People ManagementFootnote 3, the key positions, organizations and central agencies involved in the governance function related to people management, including performance management, are:

Deputy heads have primary responsibility for the effective management of the people in their organizations. They are responsible for planning and implementing people management practices that deliver on their operational objectives and for assessing their organization's people management performance. They are also responsible for working individually and collectively to foster a culture of people management excellence in the public service.

Heads of Human Resources have an essential role in supporting deputy heads in fulfilling their responsibilities.

Departmental managers are responsible for ensuring effective people management in all activities falling under their area of responsibility.

The Treasury Board may act on all matters relating to people management unless otherwise provided for under legislation such as the responsibilities of the Public Service Commission of Canada according to the Public Service Employment Act.

The Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer (OCHRO) within the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat supports the Treasury Board on matters regarding people management and enables deputy heads to fulfill their roles and responsibilities for people management by:

- Developing broad policy direction;

- Assessing and preparing reports on the state of people management in the public service;

- Working with deputy heads to develop people management capacity and to advance corporate people management priorities; and

- Establishing common business processes and shared systems.

The Information Management and Technology Directorate (IMTD), in the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, is responsible for all project activities related to the design, development and implementation of the ETMS for Management Accountability Framework requirements.

Other central organizations have key roles in government-wide people management:

- The Privy Council Office supports the Clerk in his role as Head of the Public Service including identifying and driving specific public service-wide people management priorities (annual corporate commitments).

- The Canada School of Public Service has a legislated mandate to provide learning, training and development in the public service and to assist deputy heads in meeting the learning needs of their organizations.

- The Public Service Commission of Canada is responsible for independently safeguarding the integrity of the staffing system and the non-partisanship of the public service.

The Human Resources Council, comprised of Heads of Human Resources, supports the design of a shared people management agenda and is engaged through established governance structures.

Other parties: Certain departments have people management responsibilities, such as Public Services and Procurement Canada for administrative pay matters and the Employment and Social Development Canada for Worker's Compensation, and, Health and Safety issues. Other parties such as tribunals, commissions and boards have important roles and responsibilities related to people management, as defined in legislation.

Expected Outcomes

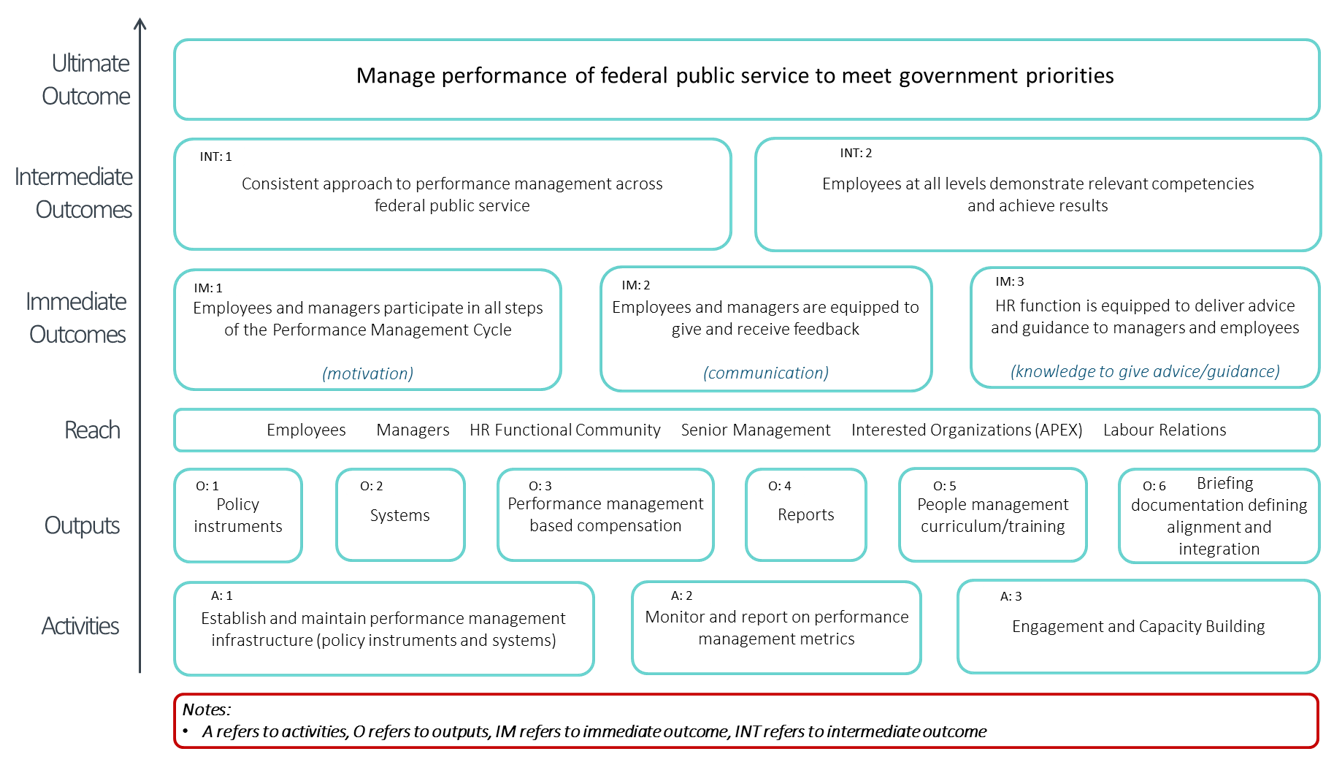

The expected outcomes of the Performance Management Program for Executives, as shown in its logic model (see Appendix A), are as follows:

Immediate

- Employees and managers participate in all steps of the Performance Management Cycle

- Employees and Managers are equipped to give and receive feedback

- HR function is equipped to deliver advice and guidance to managers and employees

Intermediate

- Employees at all levels demonstrate relevant competencies and achieve results

- Consistent approach to performance management across the federal public service

Long-term

- Manage performance of federal public service to meet government priorities

Evaluation Methodology and Scope

The evaluation assessed the EXPMP’s performance by using multiple lines of evidence. It focussed on the achievement of immediate and intermediate outcomes of the program as per the logic model (Appendix A). The lines of evidence included:

- Document review

- Administrative and performance data review

- Jurisdictional and literature reviews

- Key informant interviews (n=44)

- Case studies (n=5)

This evaluation did not undertake an assessment of the ETMS, although issues related to the system did emerge. In addition, the evaluation did not assess talent management as it was not considered to be a component of the EXPMP but a question was included for interviewees as an indicator for the expected outcome, “Employees at all levels demonstrate relevant competencies and achieve results”.

Limitation of the Evaluation

The challenges encountered in the conduct of this evaluation are outlined below. Where possible, mitigation strategies employed are also discussed.

- While the use of Public Service Employee Survey (PSES) data was valuable for this evaluation given its large sample of executives, it remains a secondary data source that was not designed for this specific evaluation. Many PSES questions relate to performance management, however the wording of the questions does not explicitly link to the program outcomes or to the ETMS. This is also true of the APEX survey which was included as part of the documentation review.

- Due to COVID-19 confinement during data collection, some ETMS records could not be accessed.

- Finally, this evaluation found little in the existing literature on the effectiveness of performance management approaches, especially for executives in the public sector.

Literature and Jurisdictional Reviews

With the lack of literature on effectiveness of performance management programs, it difficult to determine why certain processes and policies are included or excluded in different programs. However, the literature on performance management in general indicates that even though most organizations conduct performance reviews, there is no consensus about the extent to which they are effective.

Many jurisdictions reviewed for this evaluation, including the U.S and the U.K, have an approach to performance management that is similar to the EXPMP. On the other hand, some jurisdictions (e.g., Australia, Germany and Netherlands) employ a decentralized approach (e.g., different ratings systems are used by departments). The literature revealed several key lessons and challenges of performance management:

Performance appraisal results are regularly fed into talent management programs within organizations. It is common for high performers to be given increased opportunity for career advancement and low performers to be given support to improve their skillsets.Footnote 4 The fact that performance appraisal systems and talent management processes feed into each other implies that it is difficult to examine one without at least considering the other.

Talent management is used to ensure that people are matched to the right job for their skills, competencies, and career plans. Through dialogue, feedback, career support, and individually tailored learning, the potential of individuals can be fully realized, organizational priorities can be met, and public service excellence can be achieved.Footnote 5

The literature both supports and dismisses the use of formal rating systemsFootnote 6. One source suggests that in using ratings, the process should be simple and use clear language and descriptions. Ratings should be fit for the purpose for which they will be used. For example, if ratings are primarily for compensation decisions, ensure there is a clear link between the rating and the decision and ensure that this link can be explained to employees.Footnote 7

This same source indicates that documentation is often deficient for poor performance. They indicate that it is not uncommon for poor performers to have a history of satisfactory performance. They suggest that instead of requiring extensive documentation for all performance reviews, organizations should require additional documentation for any employee not performing to standard.

Unlike the use of ratings, there is some consensus among sources reviewed on the support for ongoing feedback and coaching. Coaching is often used to address problems however it should be more widely used to develop employees. For instance, a study of nurse managers found that a formal, structured coaching program will enhance, facilitate and accelerate skill acquisition and promote individual and organizational benefits faster than orientation and education alone.Footnote 8 Best practice research has found that leadership coaching is often used by organizations to improve individual and organizational performance and productivity.Footnote 9

Performance appraisals can be based on faulty assumptions, such as the belief that candid performance ratings will motivate employees to improve their performance. In fact, most employees believe they are above-average performers, and they have no desire to hear otherwise.Footnote 10

There is a need for agility: modern work-by-project approaches are short-term and tend to change along the way. This highlights the limitations of formal annual performance appraisals as employees’ goals and tasks cannot be plotted out a year in advance with much accuracy.

Individual performance reviews do not appear to enhance performance on the team level or help to track collaboration. In fact, team-based work conflicts with individual appraisals and rewards.

Performance reviews can serve many purposes, such as talent selection decisions, bonus allocation, fostering career development, enhancing communications and providing documentation in case of legal challenges. Putting all of these together in one process can create challenges. For instance, it can be difficult for staff and managers to be transparent and open about performance in the feedback process if it also feeds into promotion or compensation decisions.

Literature shows that performance is rarely normally distributed and is in fact frequently skewed. Most employees cluster tightly together at the low end with about 20 % of the population outperforming their peers by several orders of magnitude.Footnote 11

The literature suggests that performance management approaches vary according to the type of organization and the sector of work (e.g., public vs. private). This is in part due to the difference in work motivation factors between private sector and public sector executives. According to literature, contrary to the private sector, public sector employees are more sensitive to social rather than economic rewards. Footnote 12

Examples of how some jurisdictions and organizations are doing things differently from the Canadian federal public service are:

- the Ontario public service does not have performance pay

- the British Columbia public service has one performance management program for all employees. Organizations implement their own performance management systems. All B.C. public servants have access to confidential face-to-face and virtual coaching services provided by the MyPerformance tool.Footnote 13

- one federal agency found that performance pay was an administrative burden and was creating a culture of competition which hindered their ability to achieve some strategic and operational objectives. As a result, this element was removed from their performance management program.

- some large companies (e.g., Deloitte, Accenture, Cigna and Eli Lilly) are abandoning formal appraisals in favour of on-going conversations and coaching.

- Not all organizations in the Australian government use rating systems and the implementation of performance pay has not been systematic. The National Audit Office has found little concrete evidence that performance payments have improved agency performance which also reflects the lack of clarity in the literature regarding performance management programs.

FindingsFootnote 14

In this section

- Expected outcome: Employees and managers participate in all steps of the Performance Management cycle

- Expected Outcome: Employees and managers are equipped to give and receive feedback

- Expected Outcome: HR function is equipped to deliver advice and guidance to managers and employees

- Expected Outcome: Employees at all levels demonstrate relevant competencies and achieve results

- Expected Outcome: Consistent approach to performance management across the federal public service

Expected outcome: Employees and managers participate in all steps of the Performance Management cycle

Conclusion: The evaluation found that most (over 90%) employees and managers participate in all steps of the performance management process to some extent. Even so, there are impediments to the process which prevent it from being carried out as intended or required.

Among interviewees, their main program challenge was the lack of time to devote to each point in the cycle, exacerbated by:

- the timing of the year-end exercise when competing priorities are at their height

- difficulties with Executive Talent Management System (ETMS)

- the lack of training on the system.

Interviewees indicated that, given the high level of regular work demands experienced at the executive level, there was not enough time for them to complete all phases of the EXPMP as required, let alone search for tools and supports or to use them effectively. Some executives feel well equipped by the EXPMP to complete the end of year phase however many respondents mentioned that it was particularly difficult at the end of the cycle, where performance management tasks compete with other year-end activities. It is important to note, however, that the deadlines for executive performance management is 60 days after the end of fiscal.

The document review and the interviews showed that the process and principles of the EXPMP are not well understood by executivesFootnote 15 or their managers. Executives need more help to better understand the purpose of performance management and how to assess performance. Despite the tools and guidance available, it was consistently identified that employees and managers need more support to clearly understand the rating scales and the assessment of competencies. According to the document review, one aspect of onboarding with which new executives were the least satisfied included the lack of training on performance management and the ETMS.Footnote 16

Although there is much information and guidance available on GCPedia,Footnote 17 many respondents still pointed out that they are not easy to find and are not necessarily useful. Interviewees were mostly unaware of tools and supports available for developing learning plans, and those that are available are not easy to understand. Managers interviewed also indicated that it was not always clear where to go to obtain information from OCHRO.

About half of executives interviewed felt well equipped by the EXPMP to establish objectives, a learning plan, and a talent management questionnaire at the beginning of the year. Some respondents said that the objectives set at the beginning of the year should be clear and quantifiable, which is not always the case.

EXPMP guidance is clear that performance assessments must include 1) a written assessment of results achieved against established commitments; 2) a written assessment of how the results were achieved through demonstration of the Key Leadership Competencies; and 3) a performance rating summary (input to ETMS) that reflects the executive’s overall performance with respect to results achieved and demonstration of the Key Leadership Competencies.Footnote 18 Yet, the evaluation found that many departments do not engage in the process beyond what they provide through the ETMS.

Many interviewees reported that they were not aware of, or did not have time to go beyond, the ETMS or tools provided by departmental human resources. Some respondents mentioned that the system remains antiquated, is not user-friendly and lacks flexibility. The system itself is said to be hard to update when there are policy changes and the lack of functionality does not allow departments to generate reports tailored to their needs. These findings indicate that the ETMS does not meet either the needs of executive managers, or those of OCHRO. It should also be noted that the information and data input to the ETMS is not monitored or assessed.

Although talent management is a separate process from the EXPMP, the literature review indicated that efficient performance management programs tend to be strongly linked with talent management programsFootnote 19 in order to optimize people management. For instance, it is common for high performers to be given increased opportunity for career advancement and low performers to be given support to improve their skillsets based on their performance appraisal results.

The evaluation evidence did not reveal a strong link between performance management and talent management. TBS interviewees confirmed that talent management is a separate process. Moreover, when interviewees from other departments were probed, they did not have strong views on the subject. For instance, there was no consensus whether the talent management questionnaire is useful. Many felt it is useful for career planning and for performance management, while others did not see the benefits. The lack of response to questions on this process raises the question of how present talent management is in managing the executive cadre.

Expected Outcome: Employees and managers are equipped to give and receive feedback.

Conclusion: The evaluation shows that employees and managers are equipped to give and receive feedback to some extent. Constraints to the process were found, such as the convergence of a time-consuming process (exacerbated by a difficult system) with multiple year-end priorities, a lack of training, as well as reluctance to have difficult conversations.

According to TBS documentation, performance management is an ongoing process that involves planning, developing, coaching, providing feedback and evaluating employee performance. While feedback is expected to be given on a continuous basis, the policy framework and system require a minimum of three formal conversations between the manager and the EX employee: one at the beginning of the fiscal year, one at mid-year and one at the fiscal year-end.

The evaluation found that the evidence on feedback is mixed. PSES data (2019) indicates that the majority of EXs (81%) agree that they receive useful feedback from their supervisors, 86% agree that they have clear work objectives and 79% agree that they receive meaningful recognition for work well done. On the other hand, interview evidence indicates that only some managers provide useful feedback to their EX employees. These interviewees report positive effects of the feedback and support received from their manager.

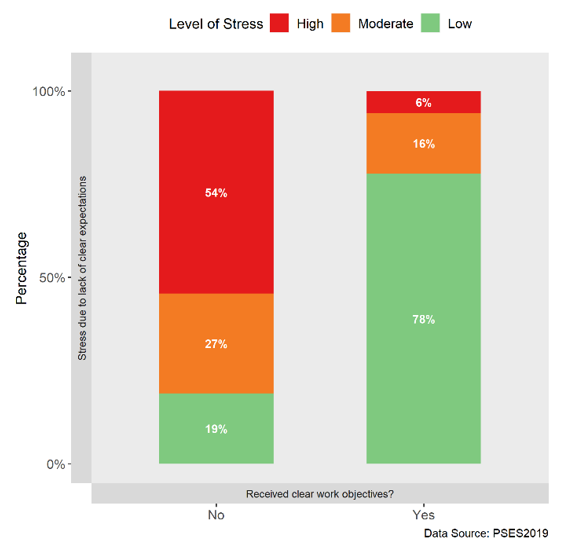

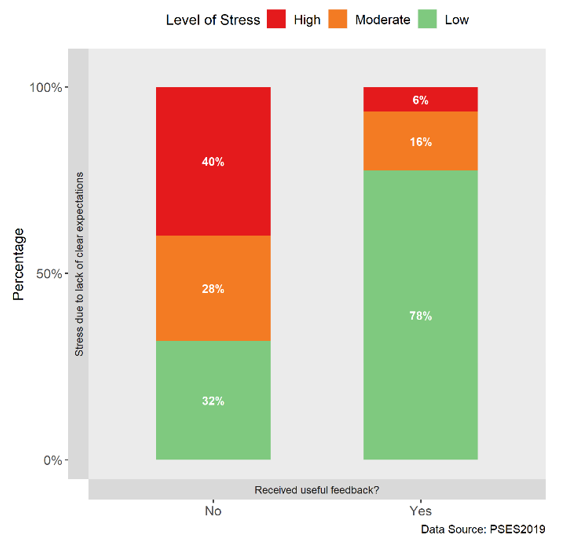

Nonetheless, further analysis of PSES data indicates that the performance management process is related to employees’ levels of stress. The data supports a statistically significantFootnote 20 relationship between the perception of the performance management processFootnote 21 and reported stress caused by workplace issues Footnote 22. As shown in the Figures 1 and 2, those executives who have positive perceptions of the performance management process tend to report less stress caused by workplace issues such as a lack of clear expectations. As well, negative perceptions of the performance management process are associated with higher levels of stress caused by workplace issues. In other words, EXs who are dissatisfied with the process are more likely to feel that pay, deadlines and unclear objectives are causes of stress for them. We can therefore hypothesize that comprehensive and useful feedback can alleviate these sources of stress for EXs which could affect performance.

Figure 1 - Text version

Figure 1 is a bar graph that indicates the association between executives’ three reported levels stress (high, moderate and low) due to lack of clear expectations and their perception of receiving clear work objectives.

For those executives who did not receive clear work objectives, 54% said their stress level is high due to lack of clear expectations, 27% said their stress level is moderate due to lack of clear expectations, and 19% said their stress level is low due to lack of clear expectations.

On the other hand, for those executives who received clear work objectives, 6% said their stress level is high due to lack of clear expectations, 16% said their stress level is moderate due to lack of clear expectations, and 78% said their stress level is low due to lack of clear expectations.

The source of this data is the Public Service Employee Survey in 2019.

| Reported stress level by executives due to lack of clear expectations | Percentage of executives who did not receive clear work objectives | Percentage of executives who received clear work objectives |

|---|---|---|

| High | 54% | 6% |

| Moderate | 27% | 16% |

| Low | 19% | 78% |

Figure 2 - Text version

Figure 2 is a bar graph that indicates the association between executives’ three reported levels stress (high, moderate and low) due to lack of clear expectations and their perception of receiving useful feedback from their immediate supervisor.

For those executives who did not receive useful feedback from their immediate supervisor, 40% said their stress level is high due to lack of clear expectations, 28% said their stress level is moderate due to lack of clear expectations, and 32% said their stress level is low due to lack of clear expectations.

On the other hand, for those executives who received useful feedback from their immediate supervisor, 6% said their stress level is high due to lack of clear expectations, 16% said their stress level is moderate due to lack of clear expectations, and 78% said their stress level is low due to lack of clear expectations.

The source of this data is the Public Service Employee Survey in 2019.

| Reported stress level by executives due to lack of clear expectations | Percentage of executives who did not receive useful feedback | Percentage of executives who received clear useful feedback |

|---|---|---|

| High | 40% | 6% |

| Moderate | 28% | 16% |

| Low | 32% | 78% |

One common theme that arose from the interviews was the hesitation among managers to discuss areas for improvement with their EX employees. Interviewees explained that some managers are better skilled than others in providing negative feedback. Several respondents spoke of being surprised with a lower year-end rating than expected when the mid-year conversations gave no indication of performance issues, which was also reflected by the document review. The literature review highlighted that leadership coaching focused on employee strengths and weaknesses can remove the element of surprise from performance reviews.

The PSES data shows that there was little difference in responses to the feedback and workplace issues among employment equity (EE) groups as compared to the EX population overall; however, people with disabilities reported lower satisfaction with their feedback than other EE groups (See Appendix B for all 15 tests and statistical measures).

The issue of time was evident again among EX employees who are dissatisfied with the feedback received based on interview and case study data. Some executives indicated they would like earlier, more frequent and more in-depth feedback and/or coaching. Some senior managers apparently do not have or do not take the time to provide meaningful feedback, when there are competing priorities. Some report that mid-year feedback simply does not occur.

Interestingly, a survey of executives conducted by APEX (2019) found that only 51% of respondents reported receiving both verbal and written feedback on their performanceFootnote 23. Based on interview evidence, the result seems to be that some employees see the process as a check-the-box exercise conducted to meet a policy requirement, thereby reducing its perceived value. The evaluation found that the performance management culture varies from one organization to another and some senior managers are more sensitized to the importance of the performance management process than others.

As mentioned earlier, there is a lack of training in this area, although many respondents said that there is limited time for senior executives to attend training. Some respondents mentioned that onboard training is not provided systematically to new EXs and should include a performance management component.

Expected Outcome: HR function is equipped to deliver advice and guidance to managers and employees

Conclusion: The evaluation found that the HR function is equipped to deliver EXPMP advice and guidance to managers and employees.

According to interview data, advice and guidance for executives on the EXPMP is typically sent by OCHRO to the heads of human resources (within each department) and the program relies on them to distribute to their executive community. For instance, one manager interviewed noted that there are talent management advisors who ensure that the information from OCHRO flows to heads of HR regularly and systematically.

The HR functions in some departments have developed their own tools and approaches to support managers with performance management; these include in-house Excel tools, online information, courses and summary or information sheets for the executives in their department.

One case study department develops different scenarios on an Excel spreadsheet for the ADMs. This allows the ADMs to compare their EX rating curve to other branches in the organization. In another case study department, HR representatives participate in the review committee meeting and are available to walk executives through the parameters of the Directive and explain the expectations. HR follows up with ADMs to determine whether they need support and guidance in preparation for difficult conversations.

According to the interviews, HR departments that have not developed their own tools are generally satisfied with those provided by OCHRO.

Expected Outcome: Employees at all levels demonstrate relevant competencies and achieve results

Conclusion: While most executives receive ratings of “succeeded” or “succeeded plus”, it is unclear:

- to what extent the EXPMP contributes to the development of competencies;

- Whether low performing executives receive the coaching and training needed;

- To what extent ratings reflect actual performance.

As indicated in the jurisdictional and literature reviews, more effective systems place a greater emphasis on providing feedback to employees on how they are meeting management’s expectations, as opposed to a numerical rating that, by itself, does not provide constructive feedback. In addition, coaching can bring about learning and improvement more quickly than education alone. The B.C. public service builds on this by providing all employees access to a coaching service. This emphasizes the importance of relationships in executive development and performance, particularly in the public service where improvement can be difficult to quantify.

The EXPMP currently formalizes the use of a single rating per individual (vs. multiple ratings used for non-EX staff). The Directive on Performance and Talent Management states that executives are given an overall rating based on their progress towards work objectives and the demonstration of the key leadership competencies.Footnote 24

Many interviewees raised concerns about combining these two areas under one rating, as doing well in one does not necessarily mean the executive has done well in the other. Furthermore, key informants indicated that managers tend to focus more on work objectives rather than competencies, such as people and team management. This is not surprising given that competencies, as indicated below, must be observed, and raises the question of how or when a supervising executive would do this in a way that allows for a fair or accurate assessment.

The importance of competencies is reflected in the literature. According to the literature review, countries such as Australia, Belgium, Canada, Korea, the Netherlands, and the U.S. consider competencies as behavioural characteristics that are observable.Footnote 25 In other words, objectives can be thought of as the “what” and competencies can be thought of as the “how”. One of the benefits of competency management is that it provides a common language, an understanding of the behaviours needed to achieve organisational objectives and consistency across the public service.Footnote 26

It is important to note that this evaluation did not review individual ETMS assessments and OCHRO does not review or monitor individual assessments (i.e. for the quality of narratives or that all fields have been populated). As a result, it is unclear to what extent written narratives are provided on both work objectives and competencies for executives, as required by the Directives. While the data on executive ratings suggests that employees demonstrate competencies and achieve results, the interview evidence suggests that work objectives are the focus of discussions at the expense of competencies.

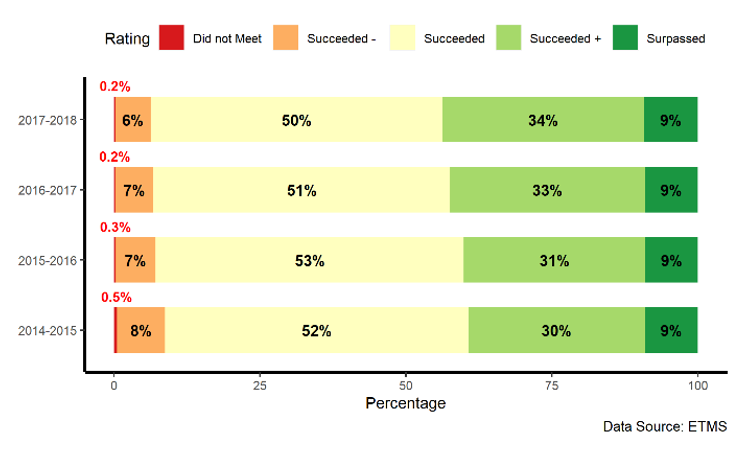

There is evidence that the average performance rating has been increasing across government, and that the lowest rating level (did not succeed) is rarely used by managers. Performance rating data from ETMS (see Figure 3) shows that more than 90% of ratings are concentrated in the middle and upper levels (succeeded, succeeded plus and surpassed), with this proportion increasing every fiscal year. Data also shows that there has been an increase in the number of “Succeeded plus” ratings (from 30% in 2014-15 to 34% in 2017-18) at the expense of the lower ratings. In particular, the lowest rating (did not meet) has gone from 0.5% in 2014-15 to less than 0.2% in 2017-18Footnote 27. In other words, it is practically unused by executive managers. The data appear to contradict the literature mentioned earlier indicating that most employees tend to perform at the lower end of a scale with only 20% outperforming their peers. It raises the question of whether the federal executive cadre is unusually high-performing, or if there is an issue with the rating system.

Figure 3 - Text version

Figure 3 is a bar graph of the rating levels for all executives by fiscal year.

In 2017–18, 0.2% of executives received a “Did not meet” rating, 6% received a “Succeeded minus” rating, 50% received a “Succeeded” rating, 34% received a “Succeeded plus” rating, and 9% received a “Surpassed” rating.

In 2016–17, 0.2% of executives received a “Did not meet” rating, 7% received a “Succeeded minus” rating, 51% received a “Succeeded” rating, 33% received a “Succeeded plus” rating, and 9% received a “Surpassed” rating.

In 2015–16, 0.3% received a “Did not meet” rating, 7% received a “Succeeded minus” rating, 53% received a “Succeeded” rating, 31% received a “Succeeded plus” rating, and 9% received a “Surpassed” rating.

In 2014–15, 0.5% of executives received a “Did not meet” rating, 8% received a “Succeeded minus” rating, 52% received a “Succeeded” rating, 30% received a “Succeeded plus” rating, and 9% received a “Surpassed” rating.

| Fiscal year | Rating | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did not meet | Succeeded minus | Succeeded | Succeeded plus | Surpassed | |

| 2017–18 | 0.2% | 6% | 50% | 34% | 9% |

| 2016–17 | 0.2% | 7% | 51% | 33% | 9% |

| 2015–16 | 0.3% | 7% | 53% | 31% | 9% |

| 2014–15 | 0.5% | 8% | 52% | 30% | 9% |

Interview findings indicate that the community has been increasingly avoiding the minimum rating to prevent the unwanted consequences associated with the lowest rating. These consequences include the mandatory development of an action plan, and negative impact on the mobility of the EX who receives a low rating. There is no performance pay or in-range movement in such cases and there may be a perception that it is too punitive. This suggests that executives who need vital support in order to meet the demands and expectations of their position, may not be receiving it which can also impact their employees and area of responsibility.

Many interviewees report that the feedback and support received from their manager are useful. Some respondents (employees), on the other hand, said that the feedback on competencies is not detailed enough, and that this is in part due to the structure of the formal competencies grid. As a result, many feel that the program does not assist EXs in developing and improving their competencies. This is especially the case for executives who identify as a member of an EE group.

The EXPMP does not seem to be effective in helping all executives equally in reaching the senior levels of the EX categories. Data shows that the EX population is not representative of the public service with respect to gender and visible minority status at the senior levels, respectively. As shown in Table 1, at the EX4-5 levels, only 43% are women compared to 55% of the federal public service as a whole; and 9% among EX4-5 executives are self-identified as visible minority versus 17% among all public service. If the program is to play a role in enabling all executives equally to develop their careers and attain the higher levels of management, data shows that more targeted effort is needed to help those in EE groups reach senior positions.

|

|

Women | Indigenous | Visible Minority | With Disability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All PS |

55% |

5% |

17% |

5% |

|

EX 1-3 |

50% |

4% |

11% |

5% |

|

EX 4-5 |

43% |

3% |

9% |

5% |

[1] Source: Pay System and Employment Equity Databank (EEDB) as of March 31, 2019. The data in this table covers employees identified for the purpose of employment equity in the Regulations to the Employment Equity Act. The population definition for Employment Equity (EE) purposes includes: Indeterminate employees and term employees (of three months or more) of departments in the core public administration. Excluded are students and casual workers, Governor in Council appointees, Ministers’ exempt staff, federal judges and deputy ministers. Employment equity data for the executive workforce includes the LC Occupational Group.

Although PSES data shows reasonable representation for Indigenous executives, research on Indigenous representation within the public service published by the Privy Council Office (PCO) in 2017Footnote 28 provides some insight to the issues this group faces. Participants in the study indicated that some recruitment and promotion processes in their current organization were neither fair nor transparent and are not considerate of Indigenous cultural values. Participants in the PCO study suggested establishing separate training platforms to provide needed support and more structured mentorship opportunities for Indigenous public servants. As previously noted, the literature supports the effectiveness of coaching and mentorship for employee development in general.

Although PSES data indicate that most EXs felt they have clear work objectives (86% agree), some interviewees spoke to a lack of quantitative measures or data to guide the performance rating decisions at the end of the year. This may also speak to the nature of work in the public service which is often not quantifiable, particularly for executives.

The interviewees also expressed a concern that the year-end ratings are subject more to review committee decisions than the judgement of their own supervisor. They feel that their role and contribution to the organization cannot be fully understood by the more senior managers. APEX documentation suggests that review committees are not familiar enough with the work and performance of the executives they are discussing, especially in organizations with hundreds of executives. The evaluation did not find evidence that would indicate the extent to which the review committee mechanism influences final performance ratings.

The evaluation found some practices which could alter the extent to which ratings reflect performance. For example, interview evidence raised the issue that some departments may give no more than a Succeeded Minus to new executives, based on the assumption that they are not capable of performing at level.

Interview evidence and APEX documentation shows that executives are often told that “bell curving” affects their overall performance rating and that budgets drive ratings. However, OCHRO’s information indicates that departments do not necessarily utilize their full budget for performance pay. Nonetheless, some EXs may not receive higher ratings due to budget limitations. The literature review indicated that bell-curving is not well perceived by staff as it is seen as being fundamentally unfair.

The interview evidence also indicates that many executives believe that the review committee mechanism examines their ratings to ensure some level of normal distribution. This practice contradicts the literature which, as indicated earlier, says that performance is often not normally distributed. HR managers indicated that some committees review the distribution of the ratings to ensure that it is “adequate” and meets budget limitations. This is not required by the Directive however TBS EXPMP documentation does specify that “The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat communicates annual limits on the amount that each organization in the core public administration may spend on performance pay. Annual limits are calculated as a percentage of the executive payroll on March 31 each year.” Footnote 29

These findings raise the issue of the purpose of performance ratings and can put in question the assumptions and validity of the approach. As indicated earlier, a performance management process that is not well-implemented can be viewed as unfair and can impact the stress levels of executives.

Expected Outcome: Consistent approach to performance management across the federal public service

Conclusion: The evaluation shows that there are areas of consistency and inconsistency in performance management across the federal public service and within departments. There is a need to clarify the meaning of “consistent approach”, which areas of the program require consistency and what that means.

According to the literature, applying the performance appraisal process in a consistent, fair and equitable manner is important for several reasons. In addition to improving trust between management and staff, it serves to lower staff turnover and maintain employee motivation. Some literature sources support the view that variation is to be expected between departments and reflects the independence of the deputy heads. This is not unique to the Canadian federal government. In fact, some jurisdictions (e.g., Germany and Netherlands) do not impose a standard government-wide approach to performance appraisals.

The evidence indicates that while the ETMS ensures some consistency in the performance management activities across government, there are processes and activities that vary significantly from one organization to another as has been illustrated in previous sections (e.g. how ratings are applied, whether and how feedback is provided, HR support, use of bell curving). Some interviewees believe that, given the considerable variation in work cultures across departments, it is more important to provide consistency within departments rather than between departments.

Some HR managers said that the processes and decisions depend on senior leadership styles within the organization. This becomes obvious when there is a change in leadership in organizations: some aspects of the program, for example, can get “delegated down”; some senior managers also invest more time in performance management than others.

A content analysis of verbatim comments from the APEX survey suggests that the EXPMP is not consistently administered. However, ETMS data shows that, in 2017-18, an overall average of departmental ratings across federal organizations was 3.52 (on a scale of 1-5), and that 70% of the organizations had an average rating between 3.29 and 3.68. Most extreme values (from 2.9 to 3.29 and 3.68 to 4.4) occurred in organizations with few EXs. This can be interpreted as departments taking a consistent approach to rating their executives.

There appears to be significant variation with respect to the supporting tools provided by the HR functions, according to the interviews. As indicated earlier, some HR functions play a more informal supporting role and mostly rely on TBS documentation, while in other departments, the HR functions have prepared templates and tools to assist the managers in their review process.

Lessons and Alternatives

Overall, the review of the literature and comparison across jurisdictions provides several potential alternatives and lessons for the present evaluation:

- The design of a performance management approach should define its purpose, how it should align with organizational goals, and articulate the guiding principles for its implementation (e.g., transparency, simplicity).

- The research highlights a trend towards more agile and flexible performance management programs, which have an emphasis on-going feedback and coaching throughout the year rather than annual or bi-annual check-ins.

- The complexity of multi-purpose performance management systems such as the EXPMP (which combines feedback, ratings and performance pay in the same process) can lead to challenges and administrative burden, as illustrated in the findings, such as:

- Avoiding the lowest rating

- Inconsistent feedback (no issues communicated at mid-year, followed by negative feedback at year-end)

- Feedback on concrete results at the expense of feedback on personal competencies

- Ambiguity of the meaning of ratings and a lack of transparency in how they are arrived at.

- Performance management programs benefit from formal, structured coaching programs that focus on developing employees and leaders throughout the year. As discussed earlier, this would be of benefit to all employees, but in particular, those who fall within an EE group.

- Recognizing differences between the public and private sectors and what that means for performance assessment, and reward and recognition. Issues have been raised such as:

- the challenge in quantifying achievements in the public sector and what that means for performance pay and total compensation

- the impact of performance pay on feedback discussions

- the motivation of public versus private sector executive employees and what that means for meaningful reward and recognition

- the benefit of agile performance management processes and systems, and what enabling agility could mean for feedback discussions and executive employee development.

Recommendations

The following recommendations are based on the evidence which demonstrate that there are opportunities for OCHRO to undertake important design changes to the EXPMP. Some of this involves a need for policy research, which was outside the scope of the evaluation and the role of the evaluators but is a necessary prelude to undertaking these changes.

- It is recommended that OCHRO develop and implement ways to simplify and streamline the EXPMP. This should start by:

- Reviewing and re-establishing foundational design principles such as being user-centred and agile, and ensuring that the process is transparent

- reducing process dependency on the IT system

- reconsidering the role and usefulness of the review mechanism.

- It is recommended that OCHRO clarify the purpose of performance pay and study its utility and impact on executives and their performance. This should also include an assessment of a growth and development focus as an alternative to ratings and performance pay. The results of this examination should inform program improvements and redesign.

- It is recommended that OCHRO increase transparency around the determination of ratings (should this approach remain) and design the process to ensure that ratings address both work objectives and competencies

- It is recommended that onboard training specifically on performance management be mandatory for executives. This should include skills related to feedback on competencies, particularly with respect to under-performing executives. It should also include understanding and addressing individual needs and cultural backgrounds of executive members in EE groups.

- It is recommended that the EXPMP increase the focus on coaching as part of managing executive performance.

Appendix A: Logic Model for the Performance Management Program

Appendix A - Text version

The main components of the logic model, from the bottom to the top, are:

- activities

- outputs

- reach

- immediate outcomes

- intermediate outcomes

- ultimate outcome

Each component is composed of various elements.

The Activities component is composed of the following elements:

- establish and maintain performance management infrastructure (policy instruments and systems)

- monitor and report on performance management metrics

- engagement and capacity-building

The Outputs component is composed of the following elements:

- policy instruments

- systems

- performance management–based compensation

- reports

- people management curriculum and training

- briefing documentation defining alignment and integration

The Reach component is composed of the following elements:

- employees

- managers

- HR functional community

- senior management

- interested organizations (APEX: Association of Professional Executives of the Public Sector of Canada) and Labour Relations

The Immediate Outcomes component is composed of the following elements:

- employees and managers participate in all steps of the performance management cycle

- employees and managers are equipped to give and receive feedback

- HR function is equipped to deliver advice and guidance to managers and employees

The Intermediate Outcomes component is composed of the following elements:

- consistent approach to performance management across federal public service

- employees at all levels demonstrate relevant competencies and achieve results

The Long-Term Outcome component is composed of the following element: manage performance of the federal public service to meet government priorities

Appendix B: Methodology and Analysis of Public Service Employee Survey Data

In this section

The Public Service Employee Survey (PSES) is an annual survey administered by the Treasury Board Secretariat’s Office of the Chief Human Resource Officer (OCHRO) that captures federal public servants’ perceptions on a range of topics. Data was collected from the 2019 results.

Three sets of themes related to the EXPMP evaluation were selected and cross referenced with associated questionsFootnote 30:

Set 1: Perception of performance management (1 = Strongly agree, 2 = Somewhat agree, 3 = Neither agree nor disagree, 4 = Somewhat disagree, 5 = Strongly disagree, 6 = Don’t know, 7 = Not applicable)

- Question 8. I receive meaningful recognition for work well done.

- Question 9. I have clear work objectives.

- Question 25. I receive useful feedback from my immediate supervisor on my job performance.

Set 2: Stress related to performance management issues (1 = Not at all, 2 = To a small extent, 3 = To a moderate extent, 4 = To a large extent, 5 = To a very large extent, 6 = Don’t know, 7 = Not applicable)

- Question 74a. Overall, to what extent do the follow factors cause you stress at work? Pay or other compensation-related issues.

- Question 74i. Overall, to what extent do the follow factors cause you stress at work? Lack of clear expectations.

- Question 74j. Overall, to what extent do the follow factors cause you stress at work? Lack of recognition.

Set 3: Employment equity groups

- Question 105. What is your gender? (1 = Male, 2 = Female, 3 = Please specify)

- Question 106. Are you an aboriginal person? (1 = Yes, 2 = No)

- Question 108. Are you a person with a disability? (1 = Yes, 2 = No)

- Question 110. Are you a member of a visible minority group? (1 = Yes, 2 = No)

- Question 112. What is your sexual orientation? (1 = Heterosexual, 2 = Gay or lesbian, 3 = Bisexual, 4 = Please specify, 5 = I prefer not to answer this question)

Data specific to the cross section of these questions for the EX occupational group was split into two subgroups: EX-01 to EX-03 and EX-04 to EX-05.

Methodology

The following terms are used in the Findings section to give a sense of the proportion of respondents that support the statement. “Some” means that only a few respondents made the comment. “Many” means that a significant number of respondents made the comment, but not a majority. “Most” means that the majority of respondents made the comment. It should be mentioned that when minority statements are identified, it does not necessarily mean that the majority of the respondents shared an opposite view due to the fact that many interviewees do not respond or are neutral.

The data was analyzed using the Chi-Square test for association and the related Cramér’s V measure of effect size on the association of the different sets of questions:

Performance management and stress: Set 1 and Set 2 (3 performance management questions x 3 stress questions = 9 tests)

Performance management and employment equity groups: Set 1 and Set 3 (3 performance management questions x 5 demographic questions = 15 tests)

Performance management and stress findings

As shown in Table S1, nine Chi-square tests show that the performance management process is related to employees’ levels of stress. Data supports a statistically significant association between the perception of the performance management process and reported stress cause by workplace issue.

| Performance management question | Source of stress | P-value | Existence of the association | Cramér’s V | Effect size of the association |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Received meaningful recognition? |

Stress due to pay related issues |

0.000 |

In all cases the test is statistically significant, indicating an association between both questions. |

0.079 |

Small |

|

Stress due to unreasonable deadlines |

0.000 |

0.156 |

Small |

||

|

Stress due to lack of clear expectations |

0.000 |

0.274 |

Medium |

||

| Received clear work objectives? |

Stress due to pay related issues |

0.000 |

0.070 |

Very small |

|

|

Stress due to unreasonable deadlines |

0.000 |

0.145 |

Small |

||

|

Stress due to lack of clear expectations |

0.000 |

0.338 |

Medium |

||

| Received useful feedback? |

Stress due to pay related issues |

0.000 |

0.047 |

Very small |

|

|

Stress due to unreasonable deadlines |

0.000 |

0.125 |

Small |

||

|

Stress due to lack of clear expectations |

0.000 |

0.265 |

Medium |

Performance management and employment equity group findings

The most significant findings concerned the demographic questions on disability and gender. In many cases an association was likely, but in only in the case of disability a meaningful recognition do we see an effect size that crosses the boundary for small (0.07 ≤ Cramér’s V < 0.21). Table S2 below summarizes these findings.

| Employment Equity group | Performance management question | P-value | Existence of the association | Cramér’s V | Effect size of the association |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender |

Received meaningful recognition? |

0.2019 |

None |

0.023 |

Very small |

|

Received clear work objectives? |

0.0027 |

Statistically significant |

0.045 |

Very small |

|

|

Received useful feedback? |

0.0001 |

Statistically significant |

0.056 |

Very small |

|

| Aboriginal status |

Received meaningful recognition? |

0.2405 |

None |

0.022 |

Very small |

|

Received clear work objectives? |

0.3535 |

None |

0.019 |

Very small |

|

|

Received useful feedback? |

0.4190 |

None |

0.017 |

Very small |

|

| Disability status |

Received meaningful recognition? |

0.0000 |

Statistically significant |

0.070 |

Small |

|

Received clear work objectives? |

0.0042 |

Statistically significant |

0.044 |

Very small |

|

|

Received useful feedback? |

0.0050 |

Statistically significant |

0.043 |

Very small |

|

| Visible minority |

Received meaningful recognition? |

0.0435 |

Statistically significant |

0.033 |

Very small |

|

Received clear work objectives? |

0.7118 |

None |

0.011 |

Very small |

|

|

Received useful feedback? |

0.1738 |

None |

0.025 |

Very small |

|

| Sexual orientation |

Received meaningful recognition? |

0.0000 |

Statistically significant |

0.079 |

Small |

|

Received clear work objectives? |

0.0000 |

Statistically significant |

0.062 |

Very small |

|

|

Received useful feedback? |

0.0002 |

Statistically significant |

0.044 |

Very small |

Appendix C: Management Response and Action Plan

The Executive and Leadership Development (ELD) sector in the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS), has reviewed the evaluation report and agrees with the recommendations. The recommendations will guide and inform ELD’s ongoing initiative to modernize the Executive Performance Management Program (EXPMP). Proposed actions to address the recommendations of the report are outlined in the tables below.

| IAEB recommendations | ELD proposed action | Starting time frame | Targeted completion time frame | Office of primary interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. It is recommended that OCHRO develop and implement ways to simplify and streamline the EXPMP. This should start by:

|

Management response: OCHRO agrees that the EXPMP should be refocused and streamlined. Proposed actions: In the short term, OCHRO will:

|

April 2021 |

November 2021 |

ELD |

|

As part of the EXPMP modernization initiative, OCHRO will:

|

April 2021 |

May 2022 |

||

| 2. It is recommended that OCHRO clarify the purpose of performance pay and study its utility and impact on executives and their performance. This should also include an assessment of a growth and development focus as an alternative to ratings and performance pay. The results of this examination should inform program improvements and redesign. |

Management response: OCHRO agrees that the use and impact of performance pay should be examined. Proposed actions: As part of the EXPMP modernization initiative, OCHRO will:

|

April 2021 |

May 2022 |

ELD |

| 3. It is recommended that OCHRO increase transparency around the determination of ratings (should this approach remain) and design the process to ensure that ratings address both work objectives and competencies. |

Management response: OCHRO agrees that the use of performance ratings should be reviewed to increase transparency and reduce bias. Proposed actions: In the short term, OCHRO will:

|

April 2021 |

November 2021 |

ELD |

|

As part of the EXPMP modernization initiative, OCHRO will:

|

April 2021 |

May 2022 |

||

| 4. It is recommended that onboard training specifically on performance management be mandatory for executives. This should include skills related to feedback on competencies, particularly with respect to under-performing executives. It should also include understanding and addressing individual needs and cultural backgrounds of executive members in EE groups. |

Management response: OCHRO agrees that training on performance management for executives should be enhanced. Proposed actions: In the short term, OCHRO will:

|

June 2021 |

December 2021 |

ELD |

|

Based on any gaps identified through this review, OCHRO will:

|

December 2021 |

January 2023 |

||

| 5. It is recommended that the EXPMP increase the focus on coaching as part of managing executive performance. |

Management response: OCHRO agrees that the EXPMP should increase the focus on coaching as part of managing executive performance. Proposed actions: In the short term, OCHRO will:

|

June 2021 |

December 2021 |

ELD |

|

As part of the EXPMP modernization initiative, OCHRO will:

|

April 2021 |

May 2022 |

||

|

December 2021 |

January 2023 |