Evaluation of the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency’s Communities and Inclusive Growth Programming

2012-2013 to 2017-2018

Evaluation, Risk and Advisory Services

Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency

February 2019

Table of Contents

2.1. Objectives of the CIG Programming

2.4. Program implementation context

2.6. Program alignment and financial resources

3.2. Evaluation Advisory Committee

3.3. Evaluation strengths and limitations

4.2. Performance: Effectiveness

4.3. Performance: Efficiency and economy

Summary of Findings, Conclusions and Recommendations

Appendix A: Summary of Findings, Conclusions and Recommendations

Appendix B: Management Action Plan

Appendix C: CIG Evaluation Framework

Acronyms

ACOA Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency

AGS Atlantic Growth Strategy

BDP Business Development Program

CAS Consultant Advisory Services (through CBDCs)

CBBD Community-based Business Development programming

CBDC Community Business Development Corporations

CEED Centre for Entrepreneurship Education and Development

CFP Community Futures Program

CIG Communities and Inclusive Growth

CIP 150 Canada 150 Community Infrastructure Program

CIIF Community Infrastructure Improvement Fund

DCBA Destination Cape Breton Association

DRF Departmental Results Framework

EDI Roadmap for Official Languages 2013-2018: Economic Development Initiative

FTE Full-time employees

G&C Grants and contributions expenditures

GBA+ Gender-based analysis plus

GCPM Grants and Contributions Program Management system

ICF Innovative Communities Fund

ISED Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada

JEDI Joint Economic Development Initiative

NB New Brunswick

NL Newfoundland

NS Nova Scotia

O&M Operations and maintenance expenditures

PAA Program Alignment Architecture

PE Prince Edward Island

RDÉE Le Réseau de développement économique et d'employabilité

REDO Regional economic development organizations

SME Small and medium-sized enterprises

WBI Women in Business Initiative

Figures

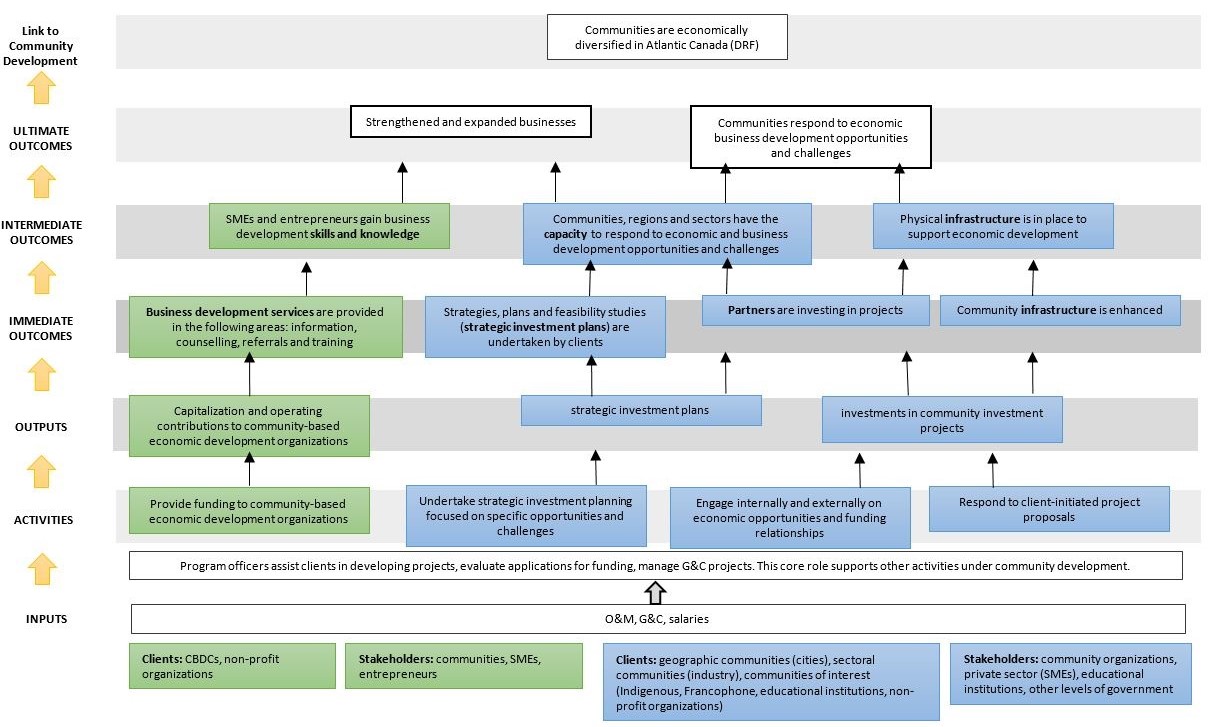

Figure 1: Communities and Inclusive Growth logic model (excluding the Community Futures program)

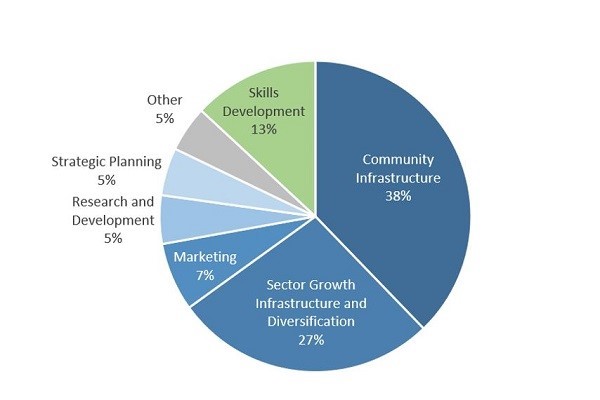

Figure 2: Types of CIG projects by funding allocation, 2012-2013 to 2017-2018

Figure 3: Client survey – Satisfaction with ACOA service features

Figure 4: Client survey – Extent ACOA programs contribute to economic development in communities

Tables

Table 1: Implementation context

Table 2: Annual CIG expenditures by fiscal year, 2012 to 2018

Table 3: Summary of data collection methods

Table 4: Evaluation limitations and mitigation strategies

Acknowledgements

This evaluation provides the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency’s ( ACOA) management with objective, neutral evidence on the relevance and performance of the Communities and Inclusive Growth programming. ACOA’s Evaluation, Risk and Advisory Services Unit completed this evaluation of Communities and Inclusive Growth programming with advice from an evaluation advisory committee (EAC).

The evaluation team thanks the members of the EAC for their advice and support throughout the study. Their contributions helped to ensure the relevance and usefulness of the evaluation. Very special thanks go to the external member of the EAC, Dr. Ather H. Akbari, St. Mary’s University, Program Coordinator, Masters in Applied Economics and Chair, Atlantic Research Group on Economics of Immigration, Aging and Diversity. Internal members of the committee are Dave Boland, Laurie Cameron, Richard Cormier, Colleen Goggin, Jeanetta Hill, Francis Jobin, Marilyn Murphy and Tom Plumridge.

We are also grateful to the external key informants as well as the many ACOA employees from across Atlantic Canada who provided their time and knowledge in support of this evaluation.

Paul-Émile David A/Director, Evaluation Risk and Advisory Services

Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency

Summary

The purpose of this evaluation is to assess the relevance and performance of the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency’s (ACOA) Communities and Inclusive Growth (CIG) programming over a six-year period, from 2012-2013 to 2017-2018. The evaluation fulfills Government of Canada accountability requirements and provides the Agency’s management with systematic, neutral evidence to support continuous program improvement. The methodology includes focus groups or interviews with 127 key informants, a client survey with an overall response rate of 56 percent, six case studies, a document and literature review, and an analysis of available performance data.

ACOA’s investments through CIG programming aim to increase the competitiveness of Atlantic Canada’s rural communities and businesses. Projects and initiatives focus on the following objectives: improving infrastructure to attract and retain investments and labour; building and maintaining partnerships; and developing skills and conducting strategic planning for the economic development of communities, regions and sectors.

Over the period of the evaluation, ACOA supported over 1600 CIG projects across Atlantic Canada through grants and contributions expenditures (G&C) and non-financial supports. The Agency expended $452.8M with 87% of this spending through G&C and the remaining to support delivery costs.

Relevance

The evaluation finds that there is a continued need for ACOA’s CIG programming. Challenges to community economic development in rural Atlantic Canada exist to the same degree or are greater than reported in the previous evaluation. In particular, the evaluation reports: an increase in demographic trends such as an aging population, a declining workforce, and the out-migration of young people; labour force and sectoral challenges, including skills shortages; inadequate infrastructure and planning capacity; and declining provincial funding for community economic development. In response to changing needs, the Agency has demonstrated an ability to adapt its programming in fostering opportunities to enhance participation in new and emerging sectors. It has also focused more attention on the convening and pathfinding roles of its staff to leverage new financial resources, and develop new partnerships for community economic development.

The CIG programming aligns with ACOA’s role and federal government priorities. It is complementary and unique to programming offered by other organizations. With a clear focus on community economic development, the programming offers both financial and non-financial supports. It offers flexibility in the amount and type of funding support. The programming is Atlantic-wide in scope and recognizes the specific opportunities and challenges of the region. The CIG programming offers on-the-ground supports for clients throughout the region and is coordinated with other Agency programming and policy functions.

Community development facilitates broader economic impacts. Initiatives that improve infrastructure and quality of life amenities attract residential and business investment. Skills development activities enhance the community’s overall capacity to respond to economic challenges. They provide opportunities for entrepreneurship or career progression to retain younger generations, attract new residents or make it possible for those that have left rural areas to return.

Performance: Effectiveness

The evaluation finds that projects have achieved the immediate outcomes expected of the CIG programming. These results focus on partnership development, capacity building and infrastructure improvement.

ACOA’s support for the development of partnerships facilitates the achievement of CIG and other economic development results. ACOA works with a range of business, community and government partners and stakeholders. It capitalizes on its capacity to collaborate and engage with partners to strengthen the region’s economy. ACOA contributes to capacity building to address skills gaps by funding a variety of projects with universities and other third-party organizations that focus on business skill development in Atlantic Canada.

As with previous evaluations, the majority of funded CIG projects support improved community and sector-based infrastructure. Community-based infrastructure, including that related to culture and recreation, supports livability and population growth. Sector-related infrastructure initiatives support tourism. Key informants and case studies indicate that these projects have led to sustained economic growth in communities in Atlantic Canada. Key informants indicated strong client demand for infrastructure supports. This includes funding through short-term infrastructure programming, such as Canada 150 Community Infrastructure Program (CIP 150) and Community Infrastructure Improvement Fund (CIIF).

ACOA continues to support strategic planning for communities and sectors. While there was a decrease in G&C projects focused on planning compared to previous evaluations, internal key informants noted an increased demand by clients for ACOA’s advice, guidance and assistance in convening stakeholders to support strategic planning and implementation of community economic development initiatives.

CIG programming contributes to inclusive growth. Inclusive growth includes promoting the participation of diverse groups and rural communities to support economic development in the region. Historically, CIG programming has included projects that address the needs of some diverse groups, including women, Indigenous communities and language minorities. With newer priorities that include focusing more directly and on a broader range of diversity groups through gender-based analysis plus (GBA+), there are opportunities to continue to enhance the depth and consistency of ACOA’s approach to inclusive growth.

Performance: Efficiency

The evaluation finds that ACOA delivers the CIG programming in a cost-effective manner. Internal costs were proportionate to the amount of funding delivered. ACOA support enabled projects to leverage substantial funds from other organizations at a level consistent with the previous evaluation. There was a high degree of client satisfaction with ACOA’s service features. To ensure efficient program delivery, there is a need to improve the internal understanding of how Agency programming supports newer Government of Canada priorities and evolving roles and approaches.

Since the last evaluation, the Agency has developed new performance measurement tools and processes that have contributed to better collection and reporting of program information to support decision making. However, there are information gaps that present challenges to the strategic, results-based management of the CIG programming. There is a need to enhance performance information on project outcomes, newer ACOA priorities, reach to diversity groups, and the nature and impacts of non-financial supports.

CIG programming is incremental to the implementation of client projects and to obtaining investments from other partners. Most surveyed clients (94%) indicated that if ACOA funding had not been available, there would have been major negative impacts on their projects. More than half of these clients (56%) indicated that their project would not have proceeded or their project would have proceeded with smaller scope (31%). Key informant interviews and case studies confirmed that ACOA’s investments and convening role have had a strong influence on the participation of other partners.

Recommendations

Based on the findings and conclusions, the evaluation makes two recommendations for senior management attention.

Recommendation 1: Continue to improve program performance and the integration of government priorities across ACOA programming by drawing upon change management principles to: articulate direction and engage staff; explore innovative approaches to engage and collaborate with external stakeholders and clients; and enhance understanding of inclusive growth.

Recommendation 2: In tandem with current Grants and Contributions Program Management System development and Departmental Results Framework integration, ensure that adequate Agency performance measurement information is available to inform decision making for program direction and strategic investment. In particular, identify ways to better report on program outcomes, integration of Government of Canada priorities, and non-financial support provided to clients, a key facilitator to the achievement of results.

1. Introduction

This report provides the results of the evaluation of the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency’s ( ACOA) Community and Inclusive Growth (CIG) programming. ACOA conducts evaluations of programming to meet accountability requirements as well to support senior management information needs for program improvement.

The evaluation covers a six-year period, from April 1, 2012 to March 31, 2018. It addresses the relevance, efficiency and effectiveness of community economic development programming under the Diversified Communities1and Inclusive Growth program pillars of ACOA’s Departmental Results Framework (DRF).

The report contains seven sections:

- Program description

- Evaluation methodology

- Relevance

- Effectiveness

- Efficiency

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

Appendices contain additional information: summary of the evaluation analytical framework, the evaluation’s findings, conclusions and recommendations, and the management action plan.

2. Program description

2.1. Objectives of the CIG Programming

The objective of ACOA’s CIG programming is to support communities across Atlantic Canada in addressing a variety of economic challenges and opportunities. According to program documentation, the CIG programming addresses core economic issues in the region, including:

- Labour and skills shortages due in part to an aging population and outmigration of youth;

- Inadequate infrastructure;

- Lack of rural community-based planning capacity;

- Declining funding capacity of provincial and municipal partners;

- Lack of diversification from traditional resource-based industries; and

- Lower participation of diversity groups in the labour force.

The Agency works with communities, key sectors and a range of other partners on initiatives to support:

- Community and sector-focused economic development infrastructure;

- Marketing of regional arts, culture and tourism events and other sector initiatives;

- Entrepreneurship and other skills development and training; and

- Communities in economic adjustment or transition due to the downturn of an industry, the loss of a large employer, or another economic change.

2.2. Eligible recipients

ACOA directs its CIG programming to non-commercial clients, including:

- Municipalities;

- Community organizations, such as those focused on arts, culture and recreation;

- Economic development and business-support organizations;

- Education and research institutions, such as universities and colleges; and

- Industry associations.

2.3. Logic model

A logic model represents a program’s theory, showing the links between program activities and expected results. The logic model for the CIG programming, as shown in Figure 1, identifies the following components:

- Inputs: these are primarily ACOA’s human and financial resources for program implementation;

- Activities: the main components of the programming are provision of funding, strategic planning and partnership development;

- Outputs: these are the tangibles arising from activities; they include financial contributions to community-based organizations, strategic investment plans, and partnerships; and

- Results chain: detail the immediate, intermediate, and ultimate outcomes behind the Communities pillar strategic outcome, “communities are economically diversified in Atlantic Canada.”

- Immediate outcomes: Community and sector growth infrastructure is enhanced; partners are investing in projects; business development services are provided in the areas of information, counselling, referrals and training; strategies, plans and feasibility studies (strategic investment plans) are undertaken by clients.

- Intermediate outcomes: Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and entrepreneurs gain business development skills and knowledge; communities, regions and sectors have the capacity to respond to economic and business development opportunities and challenges; physical infrastructure is in place to support economic development.

- Ultimate outcomes: Strengthened and expanded businesses; communities respond to economic business development opportunities and challenges.

- The target audience for the programming is primarily community-based economic development and other non-profit organizations, geographic communities (i.e., towns, regions and provinces), industry sector organizations, communities of interest (e.g., Indigenous, Francophone, newcomers, and women) and educational institutions.

Figure 1: Communities and Inclusive Growth logic model (excluding the Community Futures program)

2.4. Program implementation context

Implementation of the CIG programming falls within an ever-changing operational and organizational context that can have both direct and indirect impacts on delivery. Table 1 outlines key contextual changes and impacts on the programming over the period of the evaluation.

Table 1: Implementation context

| Context | Implementation environment of the program | Impacts on the program |

|---|---|---|

| Federal government context | Changes in governmental priorities include greater emphasis on innovation, shared activities as part of the Atlantic Growth Strategy ( AGS) 2016, and supporting diversity and inclusiveness Dissolution of the Regional Economic Development Organizations (REDOs) in 2012-2013 |

Adaptation of CIG priorities to be aligned with government priorities Larger draw on CIG staff non-financial supports related to planning and convening stakeholders |

| Provincial government context | Shifting provincial government priorities, approaches and availability of financial resources to support regional economic development | Need for ACOA to work with new funding partners and to implement program with less financial support from other levels of government |

| Departmental context | Implementation of the Canada 150 Community Infrastructure Program (CIP 150) through existing ACOA staffing resources | Impact on ACOA capacity to deliver ongoing programming in addition to time-limited funding programs |

2.5. Intervention approach

Assistance provided

ACOA’s financial assistance is typically provided in one of two ways:

- direct support to a proponent; and

- indirect support to an intermediary proponent that offers its services to entrepreneurs or other beneficiaries.

The Agency delivers the CIG programming through a continuous intake model. Proponents submit projects to ACOA at any point through the year and proposals are analyzed as they arrive against program guidelines and government priorities. Agency program officers in regional offices across Atlantic Canada work with clients to develop projects, including identifying and convening partners, leveraging other sources of funding, and providing advice and guidance. They evaluate applications for grants and contributions and manage approved projects through to the delivery of results.

Project types2

As illustrated in Figure 2, more than half of all CIG project funding (65%) supports community and sector-specific infrastructure. The program also funds projects for skills development, marketing, research and development, and strategic planning.

Figure 2: Types of CIG projects by funding allocation, 2012-2013 to 2017-2018

2.6. Program alignment and financial resources

All federal departments must have a Departmental Results Framework (DRF) that outlines their core responsibilities, expected results and programs. CIG programming is part of ACOA’s DRF under the “Communities” pillar with the expected result that “communities are economically diversified in Atlantic Canada.” At a programming level, CIG falls within diversified communities with investments that support physical infrastructure, community strategic planning, and partnerships, and inclusive communities with investments that support small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) ownership by targeted groups (i.e., women, youth, Indigenous communities, newcomers/immigrants, and language minorities).

This evaluation of CIG programming includes 1600 projects. It encompasses all of ACOA’s community development expenditures, with the following exceptions:

- Community Futures Program (CFP) investments, which were evaluated through a horizontal evaluation led by Innovation Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED) in 2018-2019;

- Canada 150 Community Infrastructure Program (CIP 150) and Community Infrastructure Improvement Fund (CIIF) projects3; and

- Roadmap for Official Languages 2013-2018: Economic Development Initiative (EDI) as ISED led a horizontal evaluation of these investments in 2017.

While the CIG programming provides significant support to the tourism industry in Atlantic Canada, the Agency completed an evaluation of its tourism investments in 2016.4 Therefore, the evaluation scope does not include a focus on this sector.

CIG programming expenditures include two grants and contributions (G&C) funding programs, the Innovative Communities Fund (ICF) and the Business Development Program ( BDP) as well as operating and maintenance (O&M). As shown in Table 2, between April 1, 2012 and March 31, 2018, there was almost $393M in G&C expenditures, with just over $60M in O&M. Most of the O&M expenses supported ACOA salaries (89%), with the remaining spending (11%) for travel and other program implementation requirements. In 2017-2018, there were approximately 68 full-time employees (FTEs) directly delivering CIG programming at ACOA5.

Table 2: Annual CIG programming expenditures by fiscal year, 2012 to 2018

| Fiscal year | G&C ($M) | O&M ($M) | Total ($M) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salaries | Other Operating | |||

| 2012-2013 | $ 59.5 | $ 8.5 | $ 1.5 | $ 69.5 |

| 2013-2014 | $ 57.4 | $ 8.0 | $ 1.5 | $ 66.9 |

| 2014-2015 | $ 66.6 | $ 8.9 | $ 0.9 | $ 76.4 |

| 2015-2016 | $ 63.7 | $ 9.3 | $ 0.9 | $ 73.9 |

| 2016-2017 | $ 69.8 | $ 9.3 | $ 0.9 | $ 80.1 |

| 2017-2018 | $ 75.7 | $ 9.4 | $ 0.8 | $ 85.9 |

| Total | $ 392.7 | $ 53.7 | $ 6.5 | $ 452.8 |

3. Evaluation methodology

This section outlines the approach for evaluating the CIG programming, including scope, methods, governance, and methodological strengths and limitations.

3.1. Data collection methods

The evaluation used both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods (Table 3). The choice of methods was determined based on their relevance and reliability, data availability and costs.

Table 3: Summary of data collection methods

| Data collection tools and objectives | Sources |

|---|---|

| Internal data and documentation: Document program design and implementation |

|

| Literature review: Validate program needs and alignment with government priorities |

|

| Key informant interviews: Assess relevance and performance from the perspective of various stakeholders |

|

| Case studies: Inform understanding of the factors that lead or contribute to program impacts |

|

| Online client survey of proponents: Assess relevance and performance from clients’ perspective |

|

3.2. Evaluation Advisory Committee

ACOA’s Head of Evaluation created and chaired an advisory committee to provide advice and guidance to the project team. The committee members commented on the evaluation framework, preliminary findings, and reports. They also facilitated access to program data, and provided advice at various stages of the evaluation process to maximize a clear reflection of the programming, targeting of specific information needs, and the usefulness of recommendations for decision making and programming improvement. The committee comprised ACOA community development program directors, a representative from the performance measurement unit, and an external issue expert in regional economic development and diversity.

3.3. Evaluation strengths and limitations

A credentialed evaluator led the CIG evaluation and designed the study based on current best practices and protocols, including those outlined in the TBS Policy on Results. The study offers a number of other strengths, including stakeholder engagement, mixed-method design, detailed case studies to examine needs and longer-term impacts, and high response rate to the client survey. ACOA’s program evaluations reflect gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) considerations, including in the scope of each evaluation project, the design and implementation of data collection methods, and the synthesis of findings.

These practices helped to mitigate the common limitations that occur as part of most program evaluations. The evaluation team considered the limitations of the study and implemented a number of mitigation strategies (Table 4).

Table 4: Evaluation limitations and mitigation strategies

| Limitation | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|

| Lack of information on project outcomes – performance data |

|

| Short timelines for conducting the evaluation |

|

| Key informant interviews are retrospective and subjective in nature |

|

| Self-selection bias: people who participate may be different from those who decline or are not invited to participate |

|

| Changes underway to respond to new priorities toward the end of the evaluation period |

|

4. Findings

This section outlines the findings for each of the 10 evaluation questions related to relevance and performance (effectiveness, efficiency, economy). The evaluation team identified findings through a process of triangulation of evidence from the collected data.

4.1 Relevance

Overall, the evaluation identifies the continued strong relevance of the CIG programming, considering the needs that exist in Atlantic Canada, alignment with government priorities, and the level of complementarity with other initiatives.

Question 1: To what extent is the CIG programming addressing a unique need?

Finding 1: Community economic development challenges exist to at least the same degree or are greater than what was reported in the previous evaluation.

There is a strong and continued need for the CIG programming. There are broad economic development challenges facing many communities in Atlantic Canada. A review of current literature indicates:

- There are ongoing disparities in economic conditions between Atlantic Canada and the rest of Canada according to national statistics.6 Atlantic Canada’s economic disparity with the rest of Canada is now largely concentrated in the rural regions. Many urban areas in Atlantic Canada now have economic performance comparable to that of the rest of Canada.7

- Atlantic Canada, particularly in its rural areas, is experiencing a number of demographic trends that have implications for the economy, including: low population growth (close to zero), more deaths than births, declining share of the total Canadian population, aging populations (highest proportion of seniors in Canada), net losses in interprovincial migration, and weak gains in international migration.8 Atlantic Canada also has rising dependency ratios,9 an aging and declining workforce,10 and significant out-migration of young people.11

- Other labour force and sectoral challenges include skills shortages and mismatches in the labour force,12 difficulty recruiting and retaining top talent, declining or challenged resource-based industries,13 and seasonal employment.14

- Economic challenges that are particularly acute in rural communities include inadequate transportation, telecommunications and other infrastructure15 and difficulty accessing financing.16 Smaller communities often lack the capacity to undertake planning and interact with higher levels of government.17 Francophone and Indigenous communities in Atlantic Canada are concentrated in rural areas, making them disproportionately impacted by these challenges.18

Interviews with key informants and a review of the literature both indicate that provincial funding for community economic development declined during the period of this evaluation. Most provincial governments in Atlantic Canada are under increasing strain as they cope with major deficits and debt.19

Through the client survey, ACOA’s clients indicated that the factors that presented the greatest challenge to the success of CIG projects were a lack of funding (30%) and sustainability (18%). Clients identified a number of broader economic development issues: access to funding (51%); declining population from out-migration, urbanization, and aging (30%); difficulty attracting new businesses or investments (25%), and shortage of skilled labour or declining workforce (22%).

Finding 2: The Agency is aware and has adapted to some extent to the evolving needs in the region.

The evaluation finds that ACOA is aware of changing economic development needs. The Agency’s decentralized delivery model, close partnerships with a variety of stakeholders, and policy functions facilitate its awareness and the development of responses to changes and opportunities in the region. ACOA demonstrated flexibility through some adjustments to programming. For example:

- ACOA is an active participant in the Atlantic Growth Strategy ( AGS) and it pivoted activities to address priorities, including establishing new partnerships around immigration to help address workforce gaps, and seeking opportunities to take a pan-Atlantic approach to some projects.

- ACOA leveraged opportunities to enhance participation in emerging sectors and took steps toward greater integration of community development programming with its enterprise development priorities. For example, as noted in case studies, ACOA made investments in Cumberland County, Nova Scotia, in clean energy and in the in Town of Holyrood, Newfoundland and Labrador, in ocean technology.

- To address gaps in the ecosystem, ACOA has increased its convening and pathfinding roles in rural communities. According to internal key informants, there has been a decrease in the capacity for economic development planning and skills programming in rural communities since the previous evaluation of this programming. (See additional details in Section 4.2, Finding 7.)

Finding 3: The program is unique and complementary to programming offered by other organizations.

The document review and key informant interviews identify that there is complementarity with programming delivered by other federal departments, and provincial and municipal governments. There was no evidence of duplication of ACOA’s CIG programming with that offered by other organizations.

Factors that set ACOA’s CIG programming apart from other programming include: the amount, type and flexibility of funding support; Atlantic-wide scope of intervention; targeted focus on community economic development; decentralized delivery model, which brings knowledge of local context and stakeholders; and coordination with the Agency’s enterprise development programming.

Other than ACOA, provincial governments are the most regular co-funders of community development projects. However, according to key informants, provincial departments in Atlantic Canada often have smaller budgets and less capacity for project assessment and development. Clients confirmed the importance of ACOA’s role in providing non-financial supports, such as project assessment and development, which often influences the decisions of provincial governments and others to invest in community economic development initiatives.

The Agency’s regional presence allows for better relationships with a range of local stakeholders and clients. It supports understanding and consideration of contextual factors that influence economic development. Clients and other key informants noted that ACOA plays a key role in fostering collaboration and coordination, as well as the development of strategies and investment projects among federal partners. (See additional details in Section 4.2, Finding 7.)

Question 2: To what extent does CIG’s programming support for community economic development align with current federal government priorities and ACOA’s DRF priorities?

Finding 4: CIG programming addresses Government of Canada priorities related to rural economic development.

ACOA addresses broad Government of Canada priorities through the CIG programming. The CIG programming aligns with expected results outlined in ACOA’s Departmental Results Framework (see also Section 2.6). The programming helps communities respond to economic business development opportunities and challenges and supports strengthened and expanded businesses. Analysis of CIG projects and key informant interviews show that ACOA supports projects related to the community capacity and sector growth, including physical infrastructure, partnership building, skills development and strategic planning. CIG programming has also supported priorities through projects aimed at diversity groups, such as women, Indigenous communities and language minorities. ACOA focused some more recent CIG projects on newcomers and new immigrants.

The programming reflects objectives outlined in key federal priority framework documents:

- The federal Innovation and Skills Plan (2017) states, “We will need to build the world’s most skilled, talented, creative and diverse workforce.” Key expected results of the Agency’s contributions to the Innovation and Skills Plan include “…resilient communities, inclusive growth, opportunities for Indigenous peoples…”20

- The Atlantic Growth Strategy (2016) outlines a common federal and provincial vision to undertake cooperative actions that will bring stable and long-term economic prosperity in Atlantic Canada. It states the need to “Develop, deploy and retain a skilled workforce by making Atlantic Canada more attractive to immigrants and addressing persistent and emerging labour market needs.”21

- The federal Budget 2018 supports the incorporation of diversity considerations into plans for economic growth. It states, “Canada’s greatest strength is the diversity of our people. To succeed in a rapidly changing world, our diversity needs to be reflected in our economy, giving every Canadian a real and fair chance at success.”22

- The Investing in Canada Plan23 (2017) highlights the need for infrastructure, for “creating long term economic growth” and “building inclusive communities.”

- Canada’s Tourism Vision24 (2016) emphasizes marketing to attract tourists, making destinations easier to access, and continuing to innovate and build on tourism product offerings.

Internal key informants indicated that there have been challenges with the integration of some newer ACOA and Government of Canada priorities in community economic development programming at ACOA. They indicated that it was not always clear how the community development programming should best incorporate and address priorities in innovation, advanced manufacturing and diversity. (See additional details in Section 4.5, Finding 14.)

Finding 5: The program supports community capacity and sector growth for broader economic development.

The CIG programming contributes to the development of core community capacity and infrastructure that facilitates broader and effective economic development. A substantial body of literature outlines the multiple impacts of community development activities.

- Infrastructure is a vital component in the economic viability of any region – whether urban or rural. The state of infrastructure is important given its impact on a community’s ability to attract residential and business investment.25 Distance and small populations challenge the maintenance of adequate infrastructure in rural areas.26

- Community development aims to develop the overall quality of life in communities. Community amenities such as retail and recreational opportunities facilitate broader economic development by making communities more attractive to businesses and their workers.27

- Community development helps to attract new residents to rural communities. Immigration is a key element to meeting labour force gaps. Participating in the global economy means attracting and welcoming workers from elsewhere who can bring in special skills and abilities or fill labour force gaps.28

- Community development builds social inclusion by promoting participation of citizens in economic endeavours, programs, or outcomes.29 Examining development from a holistic perspective, including social and economic factors, is key to community well-being.30 Place attachments can provide powerful motivators for communities to take action to preserve and improve their communities.31 The role of commitment to place, self-confidence and positive attitude should not be underestimated.32 Research has shown high correlations between social attachment and social offerings, openness, and the aesthetics of the community.33

- Skills development is often a major component of efforts to develop community capacity.34 Skills development can enhance the community’s overall ability to respond to economic challenges.35 For example, increasing capacity in community governance will ensure community leaders become more effective in communicating and working with a variety of governmental and business stakeholders.36 International community development literature identifies encouraging entrepreneurship with various support programs as an effective way to improve outcomes in communities.37 Skilled jobs and opportunities for career progression are crucial to maintaining local populations. They help retain younger generations, make it possible for those that have left to return, and attract new families.38

- Community development through community capacity building is an incremental process.39 Research suggests that rural development policy needs to be flexible, place-based, supportive, and long-term.40 To help equip rural Canada to meet economic, social and environmental challenges, rural communities require extended commitments to ensure that rural priorities receive the sustained resources and attention required to tackle problems with deep roots through strategic initiatives.41

4.2. Performance: Effectiveness

Overall, this study identifies that the programming contributes to the achievement of expected outcomes. ACOA’s delivery approach, particularly its work to develop collaborations and leverage supports for initiatives, facilitates the achievement of results. Given changes in the federal government and regional context, there are some opportunities to enhance the effectiveness of programming through continued efforts related to priorities, communication, coordination, and the availability of meaningful information to support decision making and reporting.

Question 3: How have partnerships contributed to the achievement of CIG programming goals?

Finding 6: ACOA is recognized as a trusted partner. Partnerships have been impactful in a variety of ways, including in leveraging alternative sources of funding through provincial governments, other national programs, and the private sector.

The Agency works in partnership with a range of business, community, and government stakeholders to leverage support, coordinate economic development, and react to economic challenges. All lines of evidence confirm that partnerships are critical to the success of ACOA’s programs:

- Research suggests that economic development must consider and include social relationships, diverse partnerships, working collectively to identify needs and problems, and embracing a common solution.42 Building economic capacity in Atlantic communities relies on community level volunteer leadership through local economic development organizations, and a strong role for municipalities and local governments. Building on community level partnerships is a critical factor of any community development strategy.

- Client survey results and project data indicate that the majority (90%) of projects had partners that contributed in-kind and/or financial supports. Clients indicated that projects most frequently involve provincial and municipal governments, followed by non-governmental organizations, and other federal departments as primary partners.

- Over half of survey respondents identified collaboration with partners as an important factor in the success of their project(s). Internal key informants indicated that, in addition to their important role in leveraging investments (see details in Section 4.3), collaborations have led to the development of more viable, strategic and sustainable projects. Over half of survey respondents also indicated that the projects, in turn, contributed to stronger collaborations among community stakeholders on economic development issues. Survey results also demonstrate the enduring nature of these collaborations, with 96% of respondents indicating that they are still working with some or all of these partners.

- Key informant interviews and case studies reveal that ACOA staff are well connected, have credibility and have developed relationships of trust with partners.

- Case studies identified collaboration and stakeholder engagement (both internal and external, public and private sector) as key success factors for projects. Two examples:

- The Town of Souris worked with numerous stakeholders to develop the concept for the Souris Beach Park Gateway. Important non-financial partners included: a local utility company, which relocated utility poles and overhead wiring to improve a scenic vista popular with tourists; the Government of Prince Edward Island, which installed a crosswalk for pedestrian safety and provided direction on infilling a wet land area for recreational vehicle parking.

- Destination Cape Breton Association (DCBA) engaged its key financial partners to undertake strategic planning to address the needs of the tourism industry in Cape Breton, which led to the development and implementation of the Cape Breton Festivals and Events initiative. Key informants noted that the active participation of ACOA, DCBA and the regional municipalities in the planning, funding and implementation of this initiative was critical to its success.

- The client survey, key informant interviews, and case studies show that a number of projects also involved collaborators or partners who represented the interests of diverse groups in Atlantic Canada (e.g. youth, women, Indigenous communities, newcomers/immigrants, language minorities) as detailed in Section 4.2.

Finding 7: The nature of ACOA’s partnerships is changing to address gaps in the ecosystem. CIG staff are playing increasingly complex roles related to convening and pathfinding.

ACOA’s pathfinding role includes convening and seeking additional funding partners. The Agency capitalizes on its facilitation and convenor capacity to collaborate and engage with partners to advance the region’s economy and fill gaps in the ecosystem.

The Agency’s role in convening funding and other partnerships for community economic development is not new, but it is increasing and evolving. Key informant interviews and a review of internal documents highlight a variety of factors in the ecosystem that have contributed to ACOA’s increasingly complex role in supporting community economic development:

- The reorganization of some provincial departments caused some instability and uncertainty among stakeholders related to the availability of programming and partnerships.

- The dissolution of the regional economic development organization (REDO) model in 2012-2013 led to some gaps in capacity to coordinate and plan in some communities across the region. The role of REDOs was to develop and drive economic development at the local level in partnership with other stakeholders. To some extent, provincial governments and other stakeholders have introduced new models and programming to address current needs.

- Atlantic Canada’s aging population and the out-migration of youth from rural communities has led to challenges in leadership capacity and volunteerism. Research shows that success in community development is largely dependent on leadership and the availability of volunteers.

- Many rural community groups and municipalities lack the capacity to do strategic planning, or write funding proposals.

These gaps have contributed to an increased demand for non-financial support by ACOA staff, including general advice and guidance, as well as increasingly complex convening and pathfinding roles. Internal stakeholders highlighted shifts in approach over the period of the evaluation:

- ACOA is increasingly encouraging clients to take a broader and regional approach to partnerships and initiatives (e.g. multiple municipalities, pan-Atlantic).

- ACOA’s role in partnerships has become more complex and strategic with the Agency focusing on proactive approaches to developing new partnerships with other government departments. These partnerships are more open and collaborative than ever with increased focus on complementarity – especially with provincial and municipal governments.

- The repositioning of ACOA under the ISED portfolio in 2016 provided an opportunity for the Agency to play a stronger role in facilitating a whole-of-government approach in the region. Key informants state that ACOA has been leveraging national programs more proactively to fund the projects. The convening and pathfinding roles are also becoming more predominant due to increased focus on pan-Atlantic coordination and collaboration.

- The case studies provide examples of the integral role ACOA staff played by providing ongoing advice and guidance, and convening and leveraging other stakeholders. For example, in the case of Holyrood (NL), ACOA staff provided early advice and guidance, convened partners, and supported project planning to achieve results related to stimulating economic growth in the community. In Cumberland County (NS), ACOA staff helped coordinate and facilitate interactions among collaborators that facilitated positive project outcomes related to clean energy.

Question 4: To what extent has the CIG programming undertaken capacity building activities to address skills gaps?

Finding 8: The program has contributed to addressing business skills gaps, including entrepreneurship, through both financial and non-financial supports to clients and other stakeholders.

ACOA funds a variety of projects that focus on business skill development. A review of program documents shows that ACOA funded universities, colleges and other third-party organizations to deliver entrepreneurship and community economic development training.

- University- and college-based projects focus on entrepreneurship programming and sector-specific technology and research. For example, ACOA provided funding to the Collège communautaire du Nouveau-Brunswick (CCNB) to enhance its skills development programming linked to industry opportunities in the Internet of Things (IoT) technology sector. ACOA also funded the Nova Scotia Community College to improve the competitiveness of the region’s manufacturing sector through the adoption of advanced welding technologies.

- ACOA funds third-party organizations for skill development, including:

- Venn Innovation Inc. (Venn): connect entrepreneurs with partners and resources;

- Centre for Entrepreneurship Education and Development (CEED): support entrepreneurs – training, financing and networking opportunities (NS);

- Joint Economic Development Initiative (JEDI): provide Indigenous business and workforce development services (NB);

- Le Réseau de développement économique et d’employabilité (RDÉE): provide community economic development services for Francophone and Acadian communities in Atlantic Canada; and

- Women in Business Initiative (WBI): provide a wide range of business development services, including business counselling, management skills, networking and mentoring (delivered by Community Business Development Corporations [CBDCs]).

Case studies illustrate several examples of how projects support skill development at different levels. For example, the Ulnooweg Financial Education Centre (UFEC) assists First Nation decision-makers by enhancing skills in governance and financial decision making to opening up opportunities for greater participation in the Canadian economy. The LearnSphere model addresses duplication in services and inefficiencies in delivering business management skills training to SMEs.

Key informants and case studies indicate that the role of ACOA staff has shifted to the provision of more non-financial support to help to mitigate skills gaps in community capacity for economic development. Specifically, key informants highlighted the non-financial supports ACOA provides to clients for project, proposal and partnership development and implementation. Case studies indicate that ACOA staff are instrumental in the early developmental stages of proposals and planning for projects.

A challenge in the ecosystem relates to awareness and coordination of services and supports for skill development in the region. Key informant interviews indicate that information about local business skills development service providers is not always readily available to program staff across the Agency or to external stakeholders.

Question 5: To what extent has the programming contributed to enhanced community infrastructure?

Finding 9: CIG programming makes a valued contribution to the enhancement of community and sector growth infrastructure, which supports sustained economic growth in communities.

Consistent with previous evaluations, the majority (65%) of ACOA’s CIG programming investments are infrastructure-related, with 38% coded to community infrastructure (e.g. multi-functional buildings, streetscapes, trails) and 27% to sector growth infrastructure (e.g. tourism, marine) (see Figure 2). These infrastructure projects improve the ability of communities to respond to economic opportunities and to attract and retain residents and skilled workers.

- A review of performance data and survey results indicates that infrastructure projects focus on: recreation and culture-related infrastructure to support tourism and quality of life; equipment for industry and sector-related research and other activities; upgrades to harbour fronts, electrical and buildings that enable economic activity; and buildings that accommodate commercial space.

- Key informants and case studies indicate that ACOA infrastructure funding has led to sustained economic growth in communities in Atlantic Canada and potential economic growth in others. Examples of larger recent investments include the Port Hawkesbury (NS) main street revitalization in 2017-2018 and the Huntsman Marine Science Centre in St. Andrews (NB) new salt-water intake system in 2016-2017.

- Case studies illustrate how ACOA investments in infrastructure have had sustained community and sector impacts. In the Town of Souris (PE), funding strengthened the community infrastructure (Souris Beach Gateway Park), created an improved first impression for visitors when entering (or exiting) the region leading to tourism revenue, and added amenities that have created commercial opportunities. In the Town of Holyrood (NL), large investments in physical infrastructure (breakwater, wharf, laydown space, and underwater infrastructure) led to continued growth within the ocean technology sector and subsequent growth of community amenities, including roads, schools and recreation.

- A literature review illustrates the links between infrastructure investments and outcomes related to livability, retaining workforce, attracting investment, and tourism (see Section 4.1, Finding 4).

Finding 10: Short-term programming (e.g. CIP 150, CIIF) facilitated the achievement of results related to infrastructure.

While not a focus of this evaluation, there is strong demand and benefit to clients for the funding received through short-term infrastructure programming in Atlantic Canada.

- Internal key informants indicate strong demand for the monies from short-term programs such as CIP 150 and CIIF as well as the need for more options and additional infrastructure funding at the community level. Short-term funding programs expanded the reach of ACOA existing community development programming, allowing for the provision of funding to smaller infrastructure projects in communities where it would otherwise not have been possible.

- Clients and case studies support the importance of infrastructure funding. In particular, case studies show that it can be challenging to access infrastructure funding for smaller projects, and that short-term programs were beneficial in addressing pressing needs that may not be eligible under other programs. Through the client survey, clients highlight three factors that presented a challenge to the success of their projects: lack of funding, sustainability challenges, and lack of or problems with existing infrastructure.

Question 6: To what extent are clients developing and implementing strategic investment plans?

Finding 11: ACOA supported fewer projects focused on planning through CIG programming compared to the previous evaluation period. However, other planning supports emerged in the Atlantic ecosystem and demand continued and increased for planning supports offered by ACOA staff.

ACOA supported strategic planning for communities and sectors. While there was a decrease in funding for projects focused on planning, ACOA staff contributed to strategic planning in a variety of ways.

- There was less G&C funding dedicated to strategic investment planning than in previous evaluation periods. Performance data indicate that strategic planning represented about 6%, or $10.3M, of overall CIG investments between 2012 and 2018. In comparison, the previous program evaluation done in 201443 reported $42.6M in strategic planning investments over four years (2008–2012).

- Key informants indicate that strategic planning activities are often integrated into a larger G&C project rather than coded separately. In addition, ACOA funds some strategic investment planning for projects through alternate mechanisms such as Consultant Advisory Services (CAS) through CBDCs, or through municipal or provincial governments.

- Key informants state that there was an increased demand for ACOA staff to provide non-financial supports, including advice and guidance related to strategic investment planning, compared to previous evaluation periods. Possible factors influencing the need for more direct strategic planning supports from ACOA: ACOA program and priority changes, reorganization of provincial government departments, dissolution of REDO model, and a lack of capacity in some rural communities due to demographic changes (aging population, volunteer experience).

Finding 12: Strategic investment plans built client capacity and partnerships, and supported decision making.

Survey findings and case studies support the importance of strategic planning for greater economic development impacts.

- Of those clients who undertook strategic planning, 92% indicated that concrete actions had taken place to implement the plan to a moderate, large or very large extent. A third (33%) of clients who completed the survey indicated that, within the last year, their projects contributed to the “development of economic development plans or strategies (e.g. operational plans, needs assessments or studies).”

- Clients who indicated, as a project result, the development of an economic development plan or strategy reported positive impacts. They stated that plans: helped make decisions about future activities or initiatives (73%); identified a process or strategy to engage partners or communities (67%); proposed initiatives that contribute to business/industry development or employment growth (67%); and engaged stakeholders during plan development (64%).

- All case studies included strategic planning at the outset or technical plans such as engineering plans and community economic development planning. For example, in the Town of Holyrood (NL), the project included the completion of a needs assessment and feasibility analysis into the development of an ocean technology park within the town. In Cumberland County (NS), ACOA funded a plan to identify the options, feasibility, and potential impact of smart grid technologies adoption.

Question 7: To what extent do program activities contribute to or limit inclusive growth (language minorities, youth, Indigenous, newcomers, etc.) and gender equality in communities in Canada?

Finding 13: CIG programming has contributed to inclusive growth in communities to some extent.

ACOA has contributed to some degree to achieving results through the CIG programming. Historically, ACOA community development programming has considered needs and opportunities for diverse groups, including youth, women, Indigenous communities and language minorities. More recently, the programming has supported initiatives focused on newcomers to Canada to align with priorities outlined in the Innovation and Skills Plan and the Atlantic Growth Strategy.

- While gaps in current project coding processes and systems make it challenging to assess the extent of program impact on diverse communities, examples of CIG funded projects include: Women in Business Initiative (WBI); Joint Economic Development Initiative (JEDI); Le Réseau de développement économique et d’employabilité (RDÉE); and Ulnooweg Development Group.44

- All case study projects show that the needs of youth, women, and Indigenous communities were reflected upon to some extent. The projects in two of the case studies considered the needs of newcomers and persons with disabilities. Ulnooweg focuses entirely on the needs of Indigenous communities. A component of the LearnSphere funding focused on Women in Business.

- The client survey highlights that some projects involved collaborators or partners who represented the interests of diverse groups. Of the 270 respondents who indicated that their project had partners, some indicated partners that represented the interests of the following diversity groups: youth (37%, n=99), women (29%, n=79), Indigenous (27%, n=72), newcomers (19%, n=51), and language minorities (19%, n=50).

Finding 14: Inclusive growth is a relatively new priority and concept for ACOA. The Agency has not yet fully developed its approach and capacity to meet the needs of diverse groups through its programming.

The Government of Canada is committed to incorporating the needs of diverse groups in program design and delivery. Gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) is an analytical process used to assess how diverse groups of women, men and non-binary people may experience policies, programs and initiatives. The “plus” in GBA+ acknowledges that GBA goes beyond biological (sex) and socio-cultural (gender) differences to acknowledge other identity factors, like race, ethnicity, religion, age, and mental or physical disability.45

Program documentation, internal key informant interviews and case studies indicate that there are opportunities to enhance the depth and consistency of ACOA’s approach to inclusive growth.

- There are gaps in coding of projects that create challenges for identifying the Agency’s reach to specific populations.

- Internal key informants note that ACOA has made progress even though it only began prioritizing inclusive growth late in the evaluation period. In particular, ACOA established new partnerships related to immigration, including through initiatives with: the Fredericton Chamber of Commerce, which undertook an immigrant business success-matching project; and the Atlantic Ballet Theatre of Canada, which organized and hosted four immigration summits.

- Results from internal key informants indicate inconsistencies in the understanding of the meaning and value of inclusive growth (i.e., economic benefits), as well as the best approaches for integrating for inclusive growth into daily work. However, when it comes to the importance and integration of a rural lens, internal key informants confirm a consistent understanding and application as part of program delivery.

- While all case studies reflected some integration of inclusivity in their projects, it was mostly a secondary consideration and not an explicit part of project planning.

4.3. Performance: Efficiency and economy

This section explores the extent to which ACOA uses CIG programming resources (i.e., G&C, and O&M [including human resources]) to maximize program results.

Question 8: To what extent are performance measurement structures effective in reporting on the achievement of program outcomes?

Finding 15: ACOA has made improvements to performance measurement structures since the previous evaluation, particularly related to project coding. However, there are gaps in the information available related to program outcomes, ACOA priorities such as inclusive growth, and the non-financial supports offered by the Agency.

The availability of useful and timely performance measurement data for decision making facilitates program efficiency. ACOA implemented new tools and processes since the last program evaluation to improve the availability of performance information.

- ACOA developed guidance tools to help improve strategic investments and coding of community development projects since the previous evaluation of the programming.46 According to key informants and program documentation, these efforts led to more consistent project type coding in QAccess compared to the 2014 evaluation. As a result of the new coding guidelines introduced in 2014-2015, program data shows the identification of standard project types for almost 64% ($254M) of all approved CIG contributions over the period of the evaluation. About 32% ($144M) in approved contributions, mostly from the early part of the evaluation period, had no project type specified.

- However, internal key informant interviews also highlighted that ACOA staff do not have consistent awareness or ability to implement community development coding guidance. In some cases, they identified the need for better training on project coding.

Key informants report challenges in accessing performance data for program management and reporting. A review of current measurement and tracking tools highlights the continued need to address gaps in the collection and use of performance data, in particular with respect to reporting on current priorities and broader outcomes.

- Key informant interviews indicate that there are challenges compiling performance information for corporate reporting from existing tracking tools such as QAccess and GX. Internal management key informants suggested the new Grants and Contributions Performance Management (GCPM) system as an opportunity to enhance data collection moving forward.

- A review of program information reveals that challenges remain with using current administrative tools to track program outcomes, including those related to newer Government of Canada priorities. While current project management tools have components for tracking outcomes, the actual information collected relates to activities or outputs of projects. More recently, ACOA added fields (“flags”) to its project management system to address information needs related to some identified priorities, such as clean technology and tourism, with positive early results.

- Based on a review of performance measurement data, current administrative tools do not support the consistent tracking of data on investments to support various diversity groups (i.e., women, youth, Indigenous, newcomers, language minorities, rural/urban, etc.). While there are fields (“flags”) in ACOA’s project management tool for tracking the reach to women, rural and urban communities, Indigenous, and official language minority communities, the coding has not been consistent across the organization.

- Key informant interviews and a review of performance measurement systems reflect that there is no current mechanism to track the non-financial activities of ACOA staff in supporting clients and community development initiatives. As mentioned, ACOA staff play an important role related to consensus building, pathfinding, convening, and providing general advice and guidance. There was consistent feedback from internal and external key informants that non-financial supports represent a substantial ACOA investment and is a critical element in ACOA’s approach to successful program delivery. Key informants expressed that having data to track investments in non-financial supports would help to tell a more cogent story about program impacts.

Question 9: In the context of the results being achieved, to what extent are the allocated resources (e.g. FTEs, financial) efficiently utilized?

Finding 16: Delivery costs are comparable to amounts reported in previous evaluations.

Overall, ACOA delivered CIG programming in a cost-effective manner. Its financial and non-financial supports enabled projects to leverage substantial funds from other organizations. Mechanisms that fostered efficient and economical delivery include changes in structure and governance, physical presence in communities, and redesign of the Agency’s project approval form. Factors challenging the efficiency of delivery include changes in expectations around the pathfinding role, and the need for more modern tools and technology in the field.

- Internal costs are proportionate to the amount of funding delivered, compared reasonably between ACOA regions, and are comparable with previous evaluations. An analysis of financial (GX) data indicates that the total of expenditures for CIG programming over the evaluation period was $452.8M.

- The program leveraged substantial funding from other organizations, which contributed to its efficiency. CIG programming contributed $392.6M of a total $1.2B in project costs, leveraging $777.8M from other organizations. On average, every ACOA dollar invested leveraged an additional $1.95 from other organizations. This is comparable with the previous evaluation, which reported leveraging of $2.14 for every ACOA dollar invested.

- Internal key informants report that there have been positive changes in terms of organizational structure and governance, which have allowed development officers to focus more on proactive project development and priority files. In some cases, ACOA has reorganized teams around priorities and centralized contract management to allow development officers to spend more time communicating with, and understanding, the communities they serve.

- Internal key informants underline the importance of having a physical presence in building relationships with the communities, particularly in rural areas. Internal key informants also expressed the importance of these relationships as they work to encourage communities to focus on achieving broader regional impacts.

- Internal key informants indicate that the transition to the redesigned Project Approval Form (PAF) facilitates programming efficiency. They report that the form is more straightforward, coherent and efficient, allowing for better capturing and reporting of data.

Finding 17: There is a high degree of client satisfaction with ACOA service features.

Client survey respondents indicate that ACOA staff are proactive, efficient and generally helpful at all stages of the project life cycle, including completing forms and navigating the applications and claims process. They describe ACOA as the cornerstone of many projects and stressed the importance of the physical presence of an ACOA representative in their community.

- As detailed in Figure 3, the overwhelming majority of client survey respondents indicate strong satisfaction with ACOA’s service features47. They are: very satisfied with the courteousness and professionalism of ACOA personnel (95%), the availability of ACOA personnel (94%), as well as the ongoing business relationship with ACOA personnel (93%) and business knowledge and advice offered by ACOA personnel (92%).

Figure 3: Client survey – Satisfaction with ACOA service features

- Clients who completed the survey provided written comments that reiterated their general satisfaction with the services provided by ACOA personnel. For example, clients elaborated on the collaborative working relationships they have built with their local program officers over the years, and how critical this relationship has been to the success of their projects. They spoke about the valuable knowledge and guidance provided by ACOA staff in the development of projects and recommendations for approaches to diversification and community development.

Finding 18: There is a lack of clarity about the role of community development programming in supporting newer ACOA priorities, which may lead to inefficiencies in program delivery for the achievement of results.

Uncertainty around recently changing and competing ACOA priorities may have an impact on the efficiency of program delivery. Internal key informants indicate:

- The absence of a consistent, coherent approach to addressing newer priorities may affect the Agency’s ability to deliver the programming in an efficient manner to some extent. Some internal key informants indicate that they need more information on the direction of the programming and the linkages with community development activities.

- Community development programming must remain flexible and responsive to address unique needs across the Atlantic region while also adapting to meet new government priorities. They state that it is often challenging to support community development projects in rural areas that fit under the newer priorities.

- The transition to newer priorities is requiring ACOA staff to evaluate projects and manage expectations of clients differently, since the Agency cannot support all of the same types of projects it did in the past. For example, the push for technology and automation may be causing a disconnect with some CIG clients, who continue to struggle to meet basic economic development needs such as infrastructure.

- There are challenges in addressing enhanced convening and pathfinding roles, as previously detailed in Section 4.2 (Finding 7). There are gaps in CIG staff knowledge about where to find and how to access information on available alternate funding sources for pathfinding, in particular other national programming. This issue has an impact on efficiency, as it takes time to search for and collect this information. Other challenges associated with pathfinding include lack of clear direction, federal program delivery limitations (e.g. stacking limits, different departments/programs have different eligibility criteria) and additional approval levels and layers of complexity in working with other federal departments.

- There are gaps in internal information sharing and coordination stemming from the reorganization of program areas and transition to working more collaboratively on new priorities. There is evidence to suggest that CIG has good communication between regions at the management level, and ACOA is working to break down internal silos. They suggest the establishment of regional knowledge groups for priority area to promote engagement at all levels of the Agency.

Question 10: What impact would the absence of program funding have on community strategic planning and development?

Finding 19: CIG programming has an incremental effect on clients’ ability to proceed with their projects, as well as the quality, scope and timeliness of projects, and the leveraging of funds. The absence of CIG funding would have had significant negative impacts in the community.

ACOA’s financial investments lead directly to the achievement of project results and allow projects to proceed as planned, including through the leveraging of other funding. Key informant interviews and client survey results reflect that ACOA supports have a notable impact in communities in Atlantic Canada.

- Clients report a strong link between ACOA funding and project results. Through a survey, clients were asked what would have occurred in the absence of the funding received. Ninety-four percent (94%; n=288) of respondents indicated that if ACOA funding had not been available, it would have had a major negative impact on their project(s). The majority indicated that their project would not have proceeded (56%; n=172) or their project would have proceeded with smaller scope (31%; n=94). Other negative impacts listed include time delays and lost partners.

- ACOA influences other partners to support planning and investment projects. Key informants, including most case study clients, reported challenges securing funding from other public and private sector sources. They stated that ACOA’s involvement and investments had an important influence on leveraging other project funding from provincial governments, and from municipal governments and other federal departments.

- Eighty percent (80%, n=244) of clients responding to the survey indicated that ACOA’s existing programs contribute to economic development in their communities to a great extent (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Client survey – Extent ACOA programs contribute to economic development in communities

- Clients reported that if ACOA funding had not been available, there would have been a variety of negative community impacts. These negative impacts would have included: reduced economic development/business activity (68%); reduced tourism development opportunities (59%); reduced training and skills development opportunities (41%); deteriorated/inadequate community infrastructure/equipment (41%); and decreased quality of life/livability (39%).

5. Conclusions

Overall, the evaluation finds that ACOA’s CIG programming remains relevant to current needs and government priorities and is achieving expected outcomes related to community economic development in Atlantic Canada. There are some areas for attention to ensure ongoing and strengthened strategic investments through the programming. The evaluation concludes:

- ACOA’s CIG programming is relevant to current needs and priorities. There is a continued need for CIG programming and this programming is aligned with government priorities. Community development investments lay a foundation for future economic growth.

- ACOA is a valued and trusted partner in economic development in Atlantic Canada. Partnerships have been an integral part of ACOA’s approach and critical to its success. Results achieved are facilitated by ACOA’s regional delivery model and non-financial supports provided by ACOA staff. ACOA staff are playing an increasingly complex role in facilitating local community economic development, including convening, pathfinding and skill development.

- Activities have contributed to the achievement of intended outcomes. ACOA continues to play a key role in supporting community and sector partnerships, skills, infrastructure, and planning. These strategic investments are a catalyst to attracting investments and future economic growth. Leveraging other programming (including short-term infrastructure funding) will continue to be necessary to meet ongoing needs.

- There are opportunities to solidify ACOA’s approach to integrating new Government of Canada priorities, including diversity, in current programming. ACOA can further strengthen its leadership, strategic planning and direction, engagement of staff, and results monitoring to better address key government priorities through the programming.

- ACOA delivered CIG programming in a cost-effective manner. Internal costs are proportionate to the corresponding level of G&C funding expended. CIG program funding was incremental to the implementation of projects.

- There are ongoing performance measurement gaps. While availability of performance data related to project types is improving, there is inconsistency in knowledge about, and use of, performance measurement as a tool to support program management. There are opportunities across ACOA to enhance the quality of performance information on broader program outcomes, results for diverse groups, and non-financial supports.

6. Recommendations

Based on the evaluation findings and conclusions, the evaluation makes two recommendations to ensure continued and enhanced programming relevance and operational effectiveness in the future. Appendix A presents a one-page summary of key findings, conclusions and recommendations.

Recommendation 1: Continue to improve program performance and the integration of government priorities across ACOA programming by drawing upon change management principles to: articulate direction and engage staff; explore innovative approaches to engage and collaborate with external stakeholders and clients; and enhance understanding of inclusive growth.

Recommendation 2: In tandem with current Grants and Contributions Program Management system development and Departmental Results Framework integration, ensure that adequate Agency performance measurement information is available to inform decision making for program direction and strategic investment. In particular, identify ways to better report on program outcomes, integration of Government of Canada priorities, and non-financial support provided to clients, a key facilitator to the achievement of results.

ACOA senior program management has agreed with the evaluation’s recommendations. It has developed a management action plan (MAP) that details the actions that the Agency will take to address each of the two recommendations. Appendix B presents the MAP.

Appendix A: Summary of Findings, Conclusions and Recommendations

| Summary of Findings, Conclusions and Recommendations | ||