Report on the consultations – Cross-Canada Official Languages Consultations 2022

On this page

- Report on the Public Consultations – A Word from the Minister

- Introduction

- 1. Federal government commitment – Modernization of the Act and the next Action Plan for Official Languages 2023-2028

- 2. The 2022 Cross-Canada Official Languages Consultations

- 3. Outcome of public consultations: observations, comments and recommendations

- 3.1 Vitality and development of official language minority communities

- 3.2 Second-language learning and promotion

- 3.3 Appreciation and bridge building between English and French speakers

- 3.4 Protection and promotion of French: public and private sectors, international and cultural diplomacy, scientific knowledge

- 3.5 Diversity and inclusion

- 3.6 Government leading by example, research and knowledge about official language realities in Canada

- 4. Official Languages Summit, Ottawa, August 25, 2022

- Youth panel

- Demographic trends and substantive equality

- Promotion, reception, integration and retention of newcomers to Francophone communities

- Economic development, aging communities, youth out-migration, access to services, groups of interest within minority communities

- Intergovernmental affairs and international perspectives on the advancement of both official languages

- The educational continuum, from early childhood to post-secondary: literacy, development of language skills, infrastructure and learning tools

- Access to second-language learning, linguistic security, and social, cultural and artistic dialogue

- Leadership in official languages governance

- 5. Next steps

- Annex 1: Comprehensive Analysis of the Online Questionnaire

- Annex 2: List of organizations that participated in the in-person forums

- Vancouver, British Columbia, May 24, 2022

- Winnipeg, Manitoba, May 26, 2022

- Toronto, Ontario, June 10, 2022

- Montreal, Quebec, July 6, 2022

- Sherbrooke, Quebec, July 7, 2022

- Sudbury, Ontario, July 13, 2022

- Iqaluit, Nunavut, July 18, 2022

- Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, July 19, 2022

- Moncton, New Brunswick, July 20, 2022

- Whitehorse, Yukon, July 21, 2022

- Saint john’s, NewFoundland and Labrador, July 26, 2022

- Edmonton, Alberta, July 28, 2022

- Regina, Saskatchewan, July 29, 2022

- Summerside, Prince Edward Island, August 4, 2022

- Halifax, Nova Scotia, August 9, 2022

- Annex 3: list of organizations that submitted written reports and proposals

List of figures

- Figure 1: In which province or territory do you currently reside?

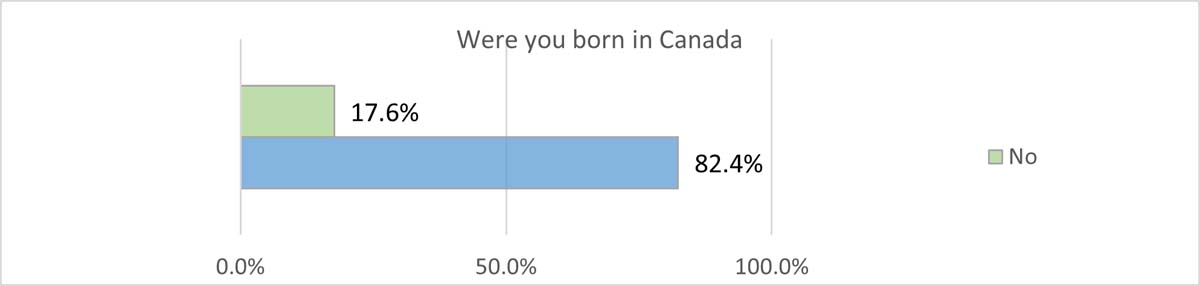

- Figure 2: Were you born in Canada?

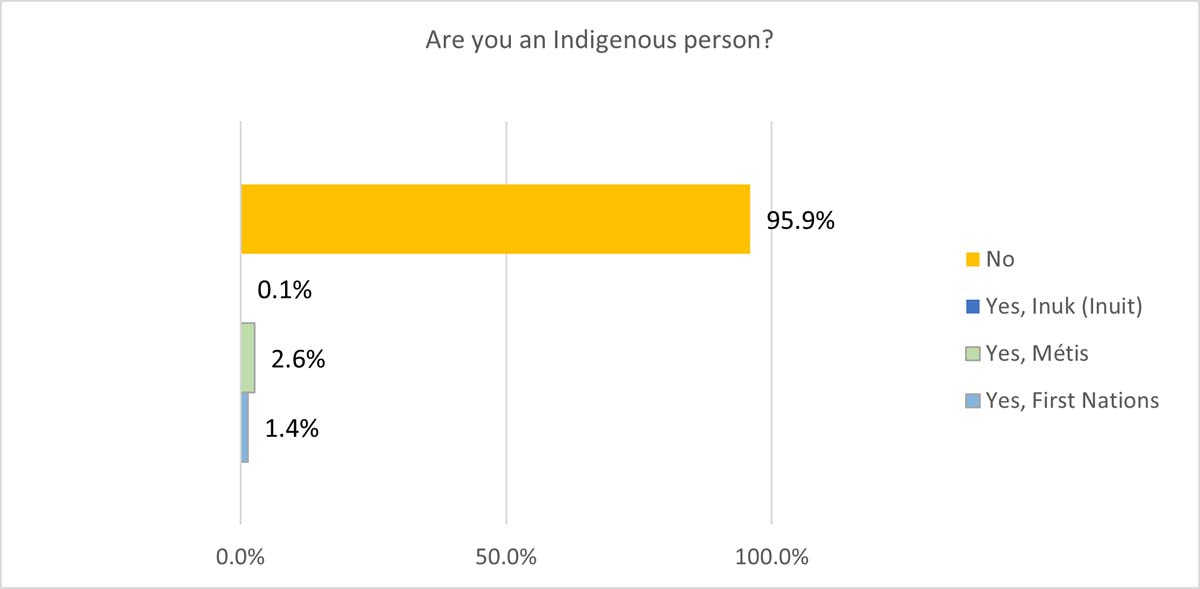

- Figure 3: Are you an Indigenous person?

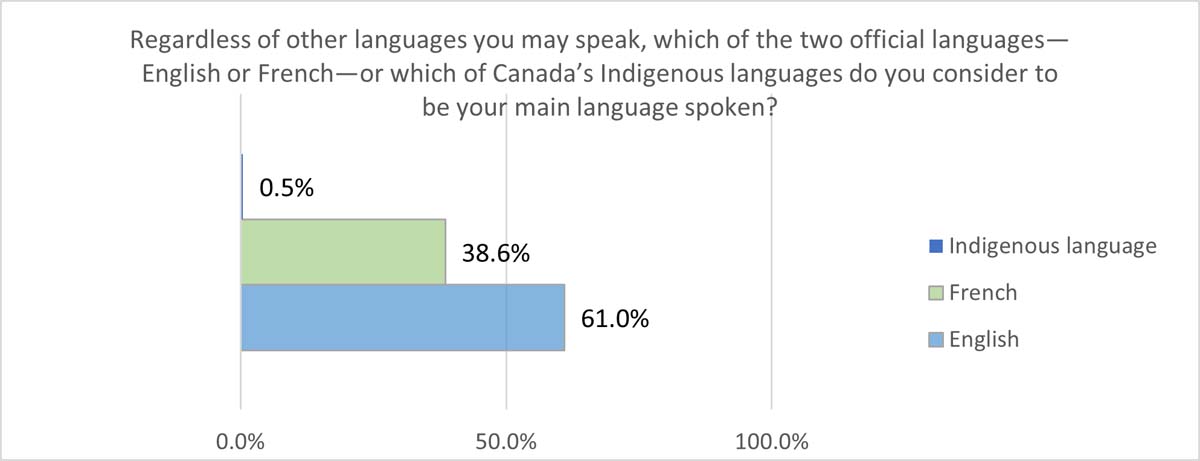

- Figure 4: Regardless of other languages you may speak, which of the two official languages—English or French—or which of Canada’s Indigenous languages do you consider to be your main language spoken?

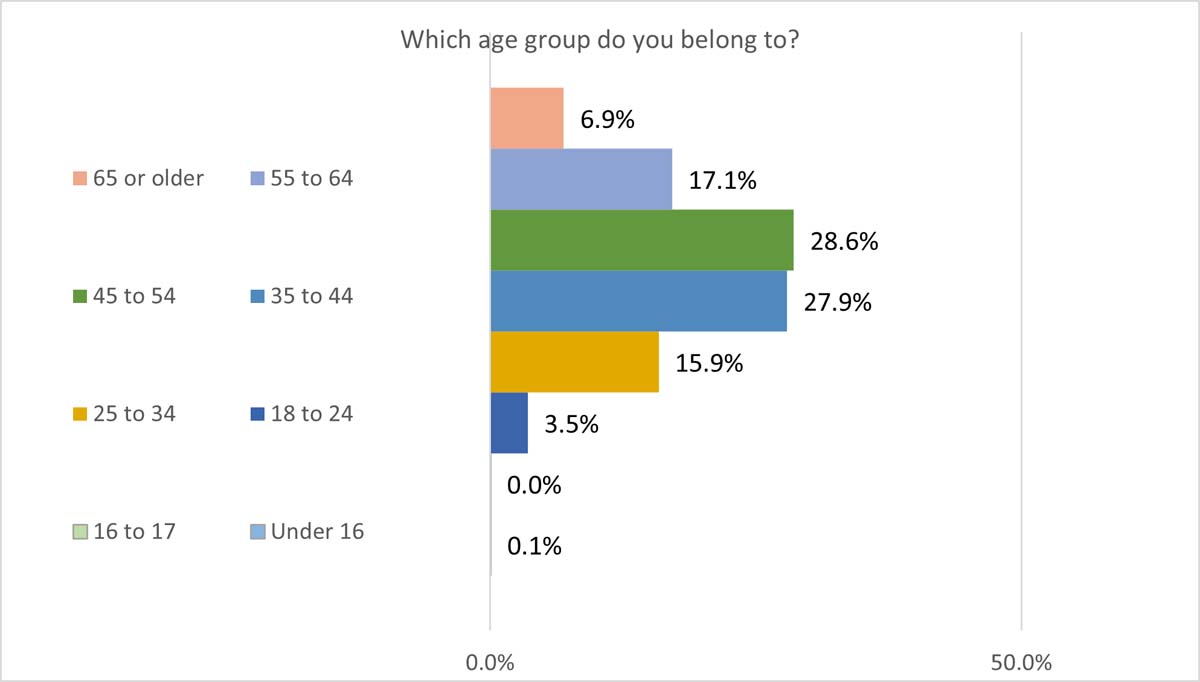

- Figure 5: Which age group do you belong to?

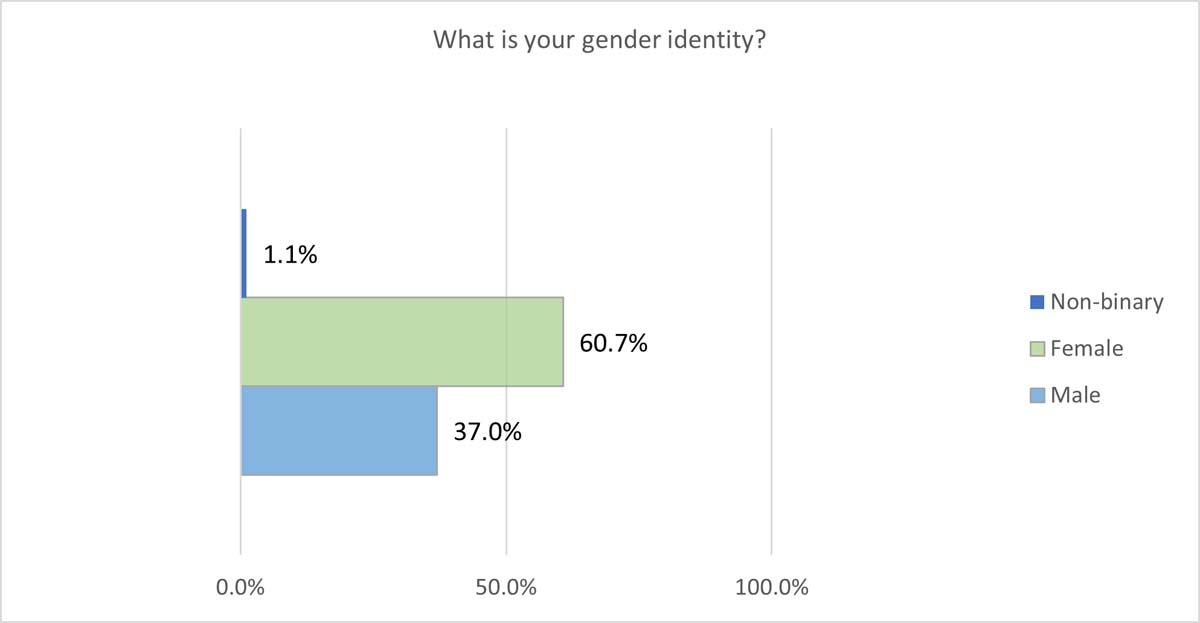

- Figure 6: What is your gender identity?

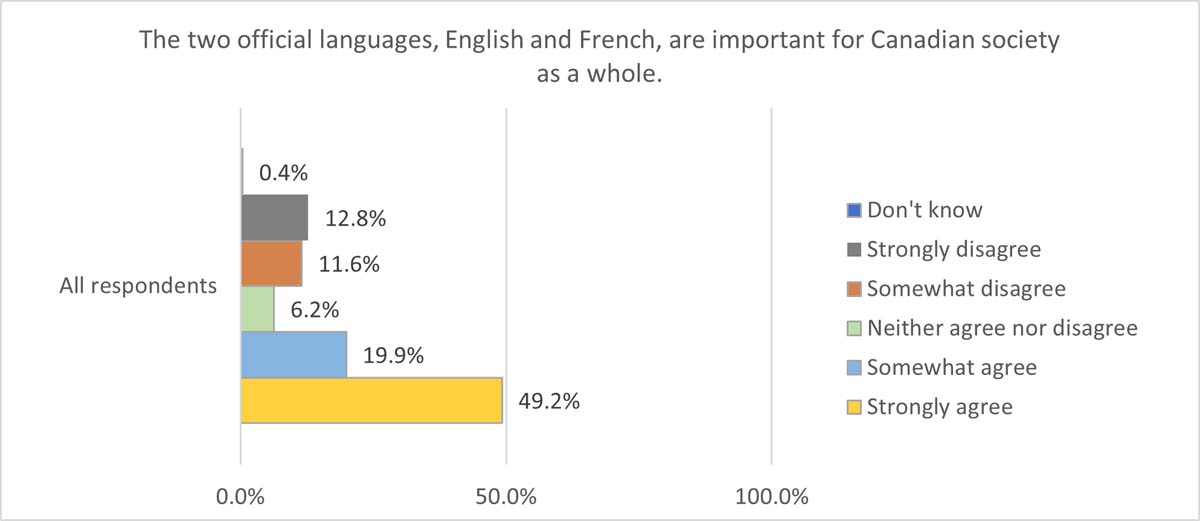

- Figure 7: The two official languages, English and French, are important for Canadian society as a whole

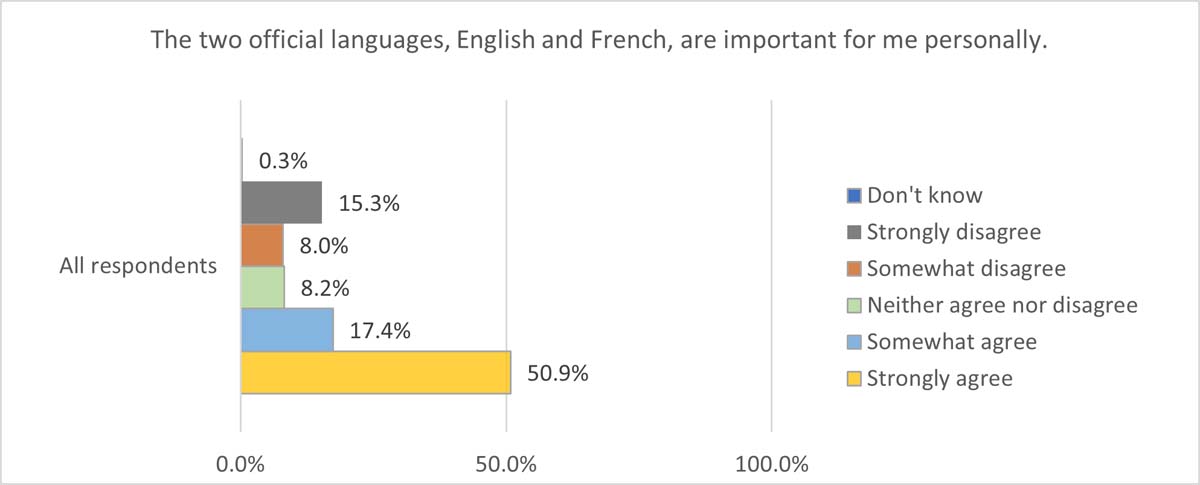

- Figure 8: The two official languages, English and French, are important for me personally

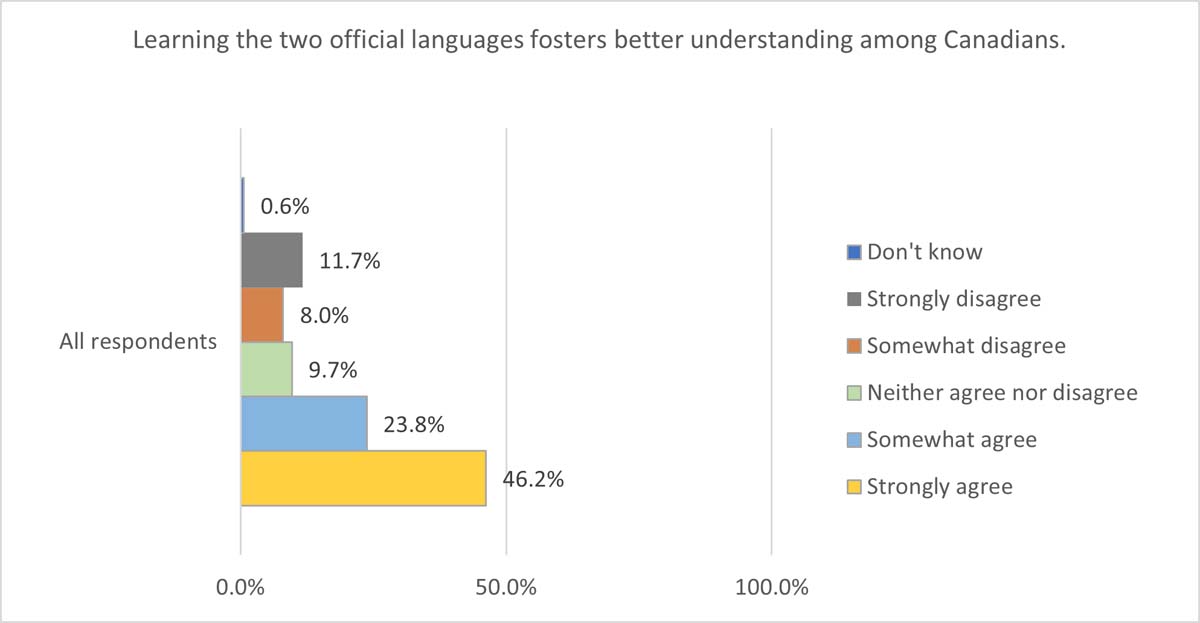

- Figure 9: Learning the two official languages fosters better understanding among Canadians

- Figure 10: The official languages (English and French) bring Canadians together, regardless of their origins

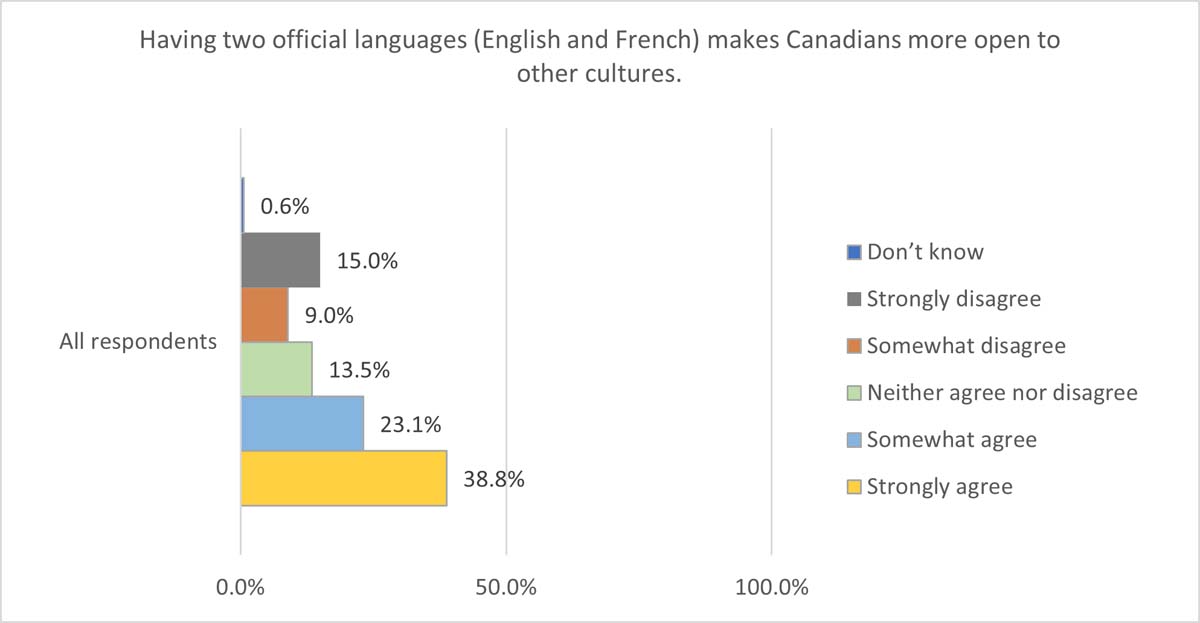

- Figure 11: Having two official languages (English and French) makes Canadians more open to other cultures

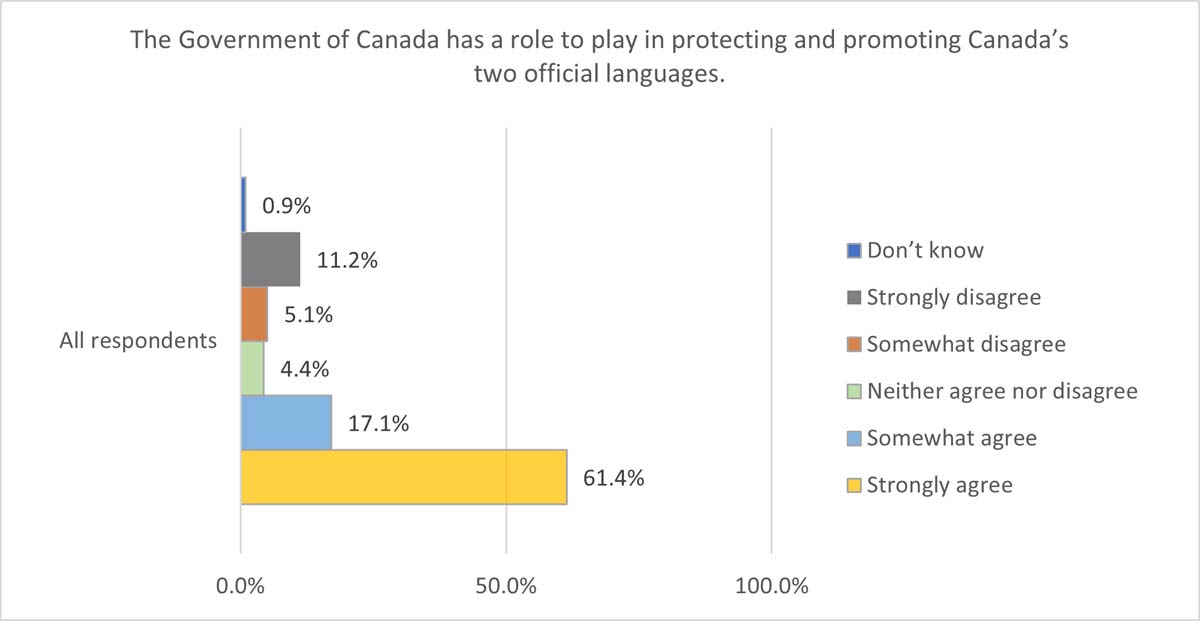

- Figure 12: The Government of Canada has a role to play in protecting and promoting Canada’s two official languages

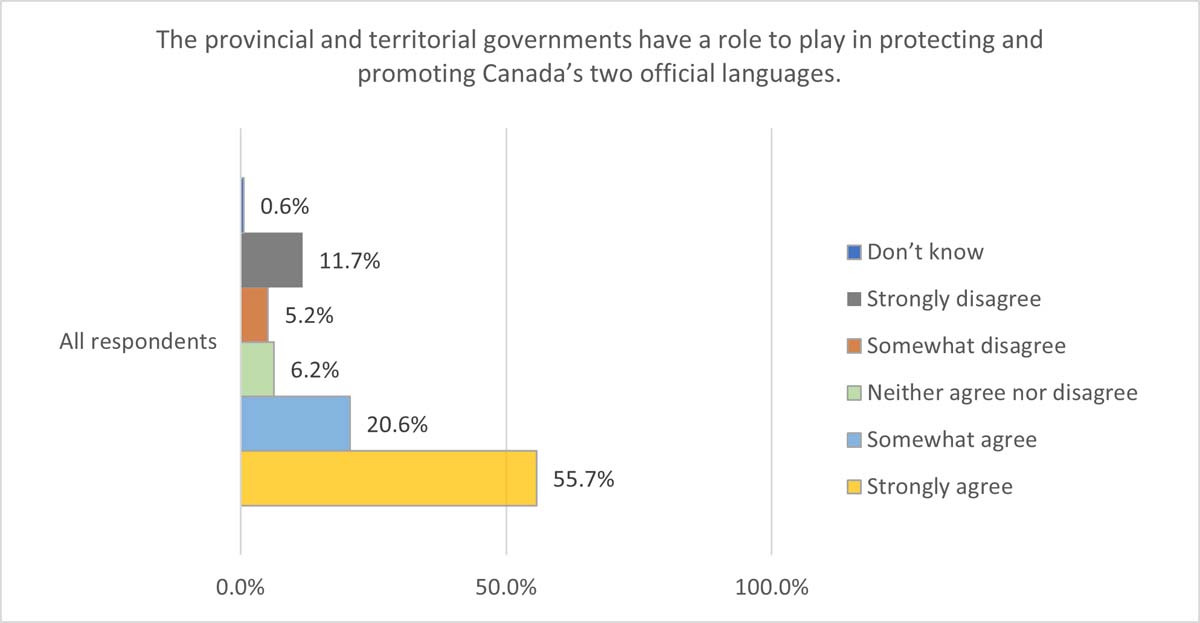

- Figure 13: The provincial and territorial governments have a role to play in protecting and promoting Canada’s two official languages

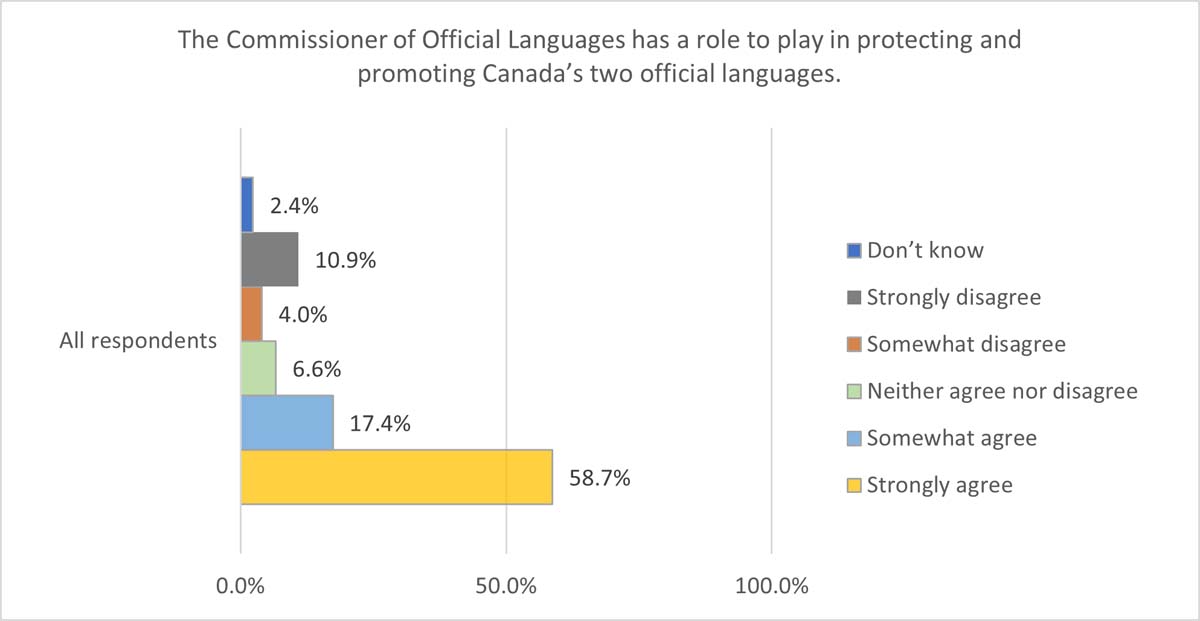

- Figure 14: The Commissioner of Official Languages has a role to play in protecting and promoting Canada’s two official languages

- Figure 15: The Government of Canada should further strengthen official languages governance and horizontal coordination to better engage and educate federal organizations

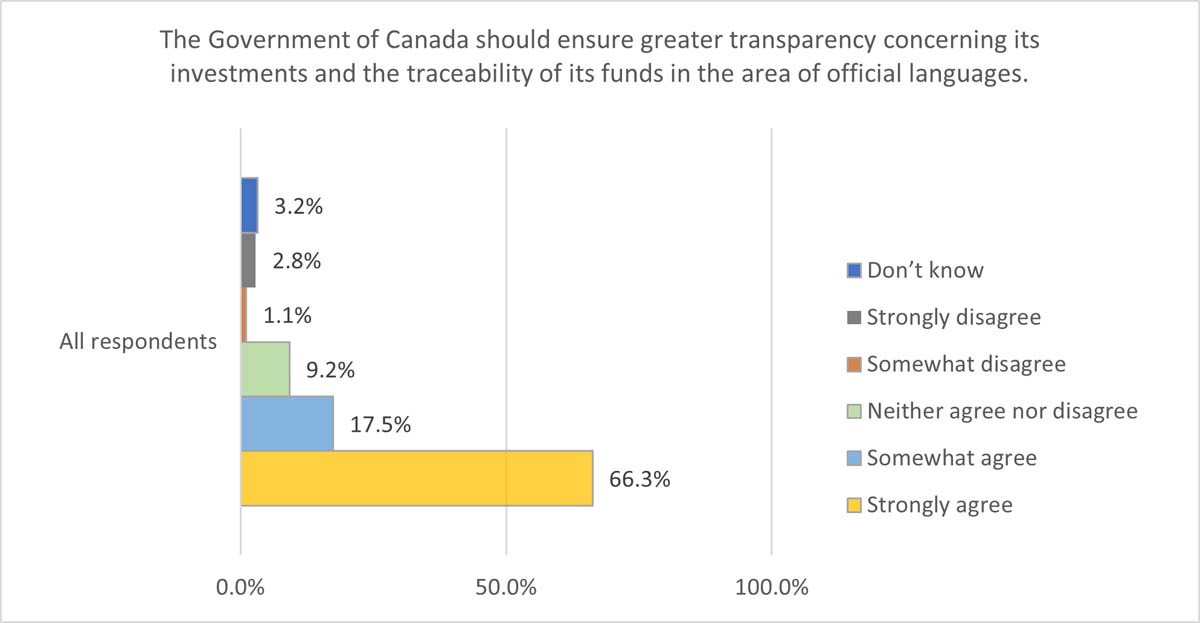

- Figure 16: The Government of Canada should ensure greater transparency concerning its investments and the traceability of its funds in the area of official languages

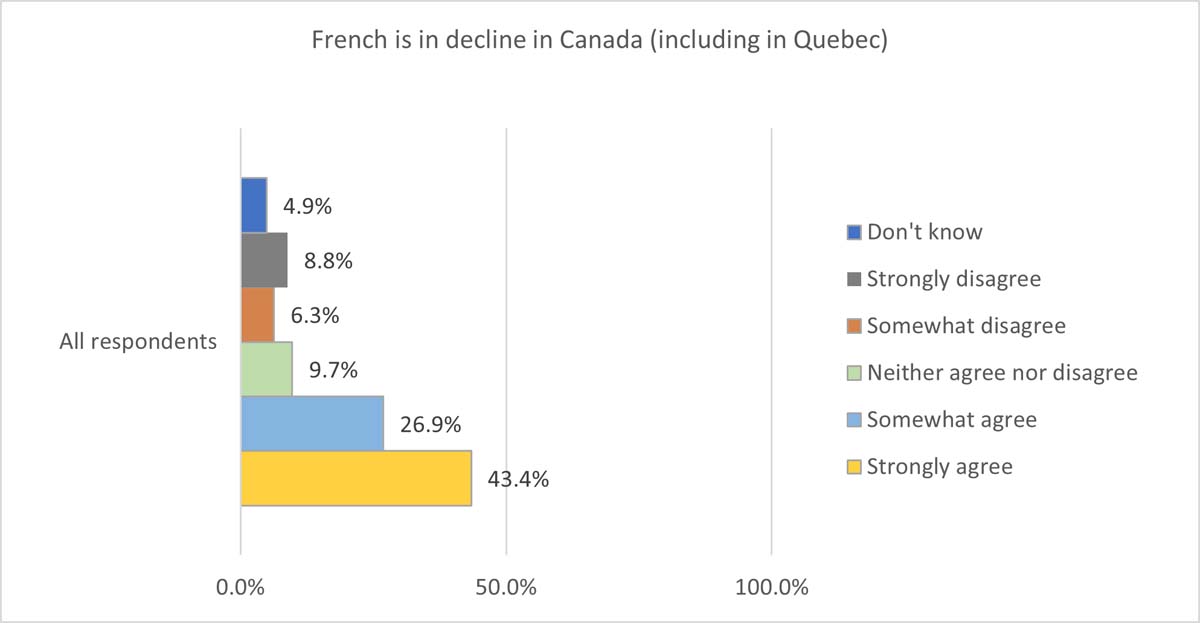

- Figure 17: French is in decline in Canada (including in Quebec)

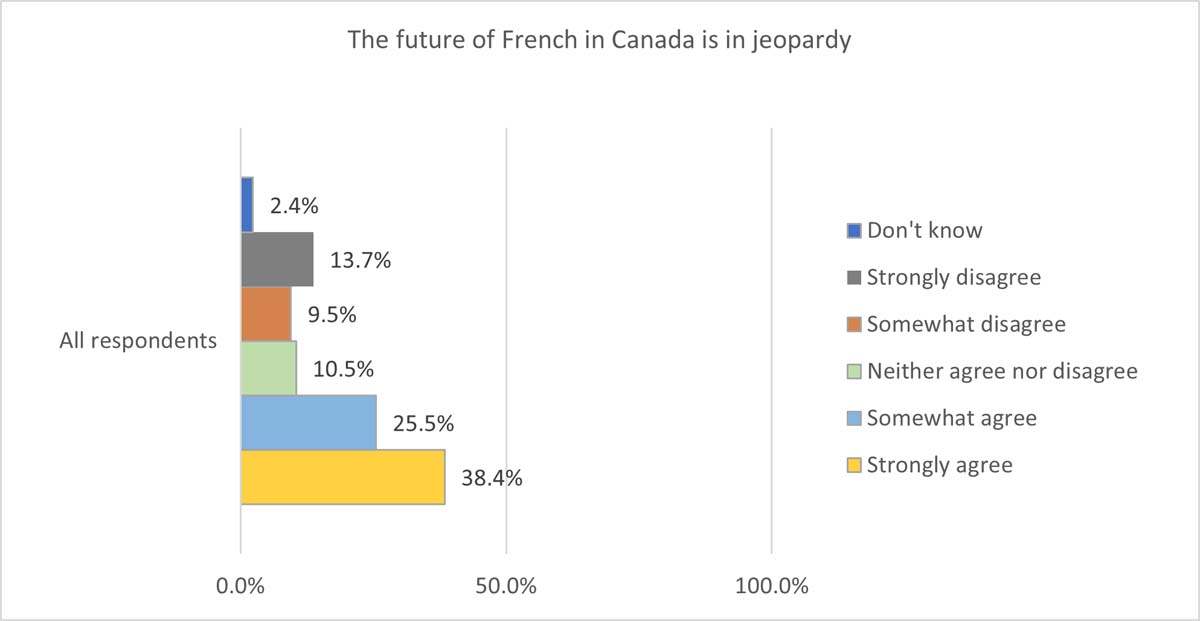

- Figure 18: The future of French in Canada is in jeopardy

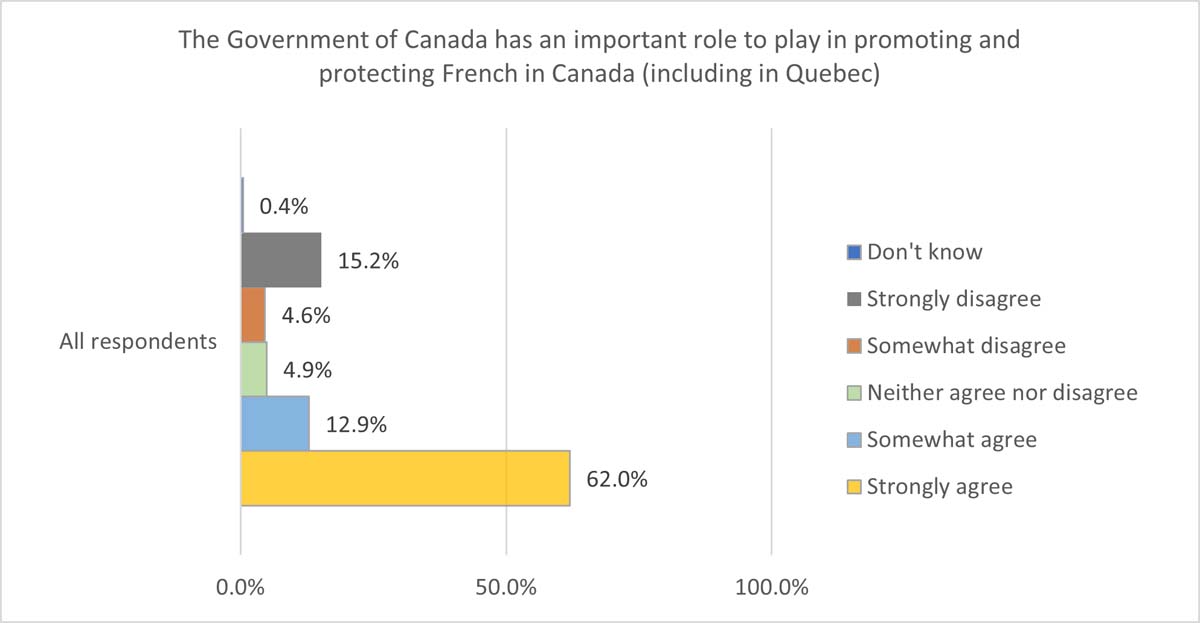

- Figure 19: The Government of Canada has an important role to play in promoting and protecting French in Canada (including in Quebec)

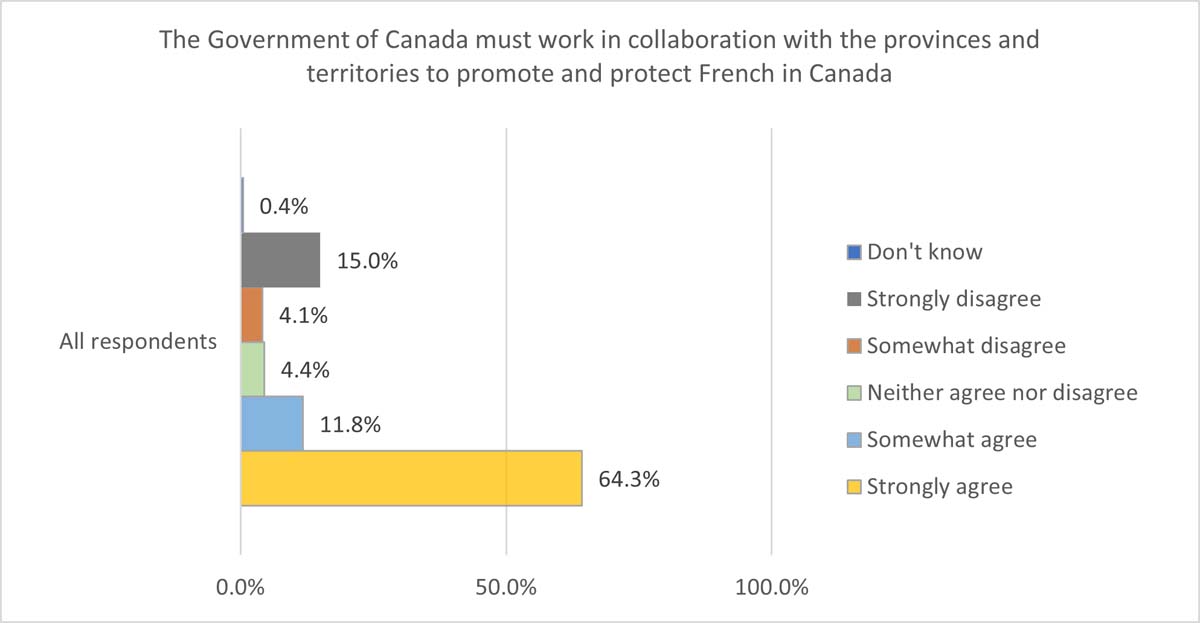

- Figure 20: The Government of Canada must work in collaboration with the provinces and territories to promote and protect French in Canada

- Figure 21: Population who strongly agrees with the various statements

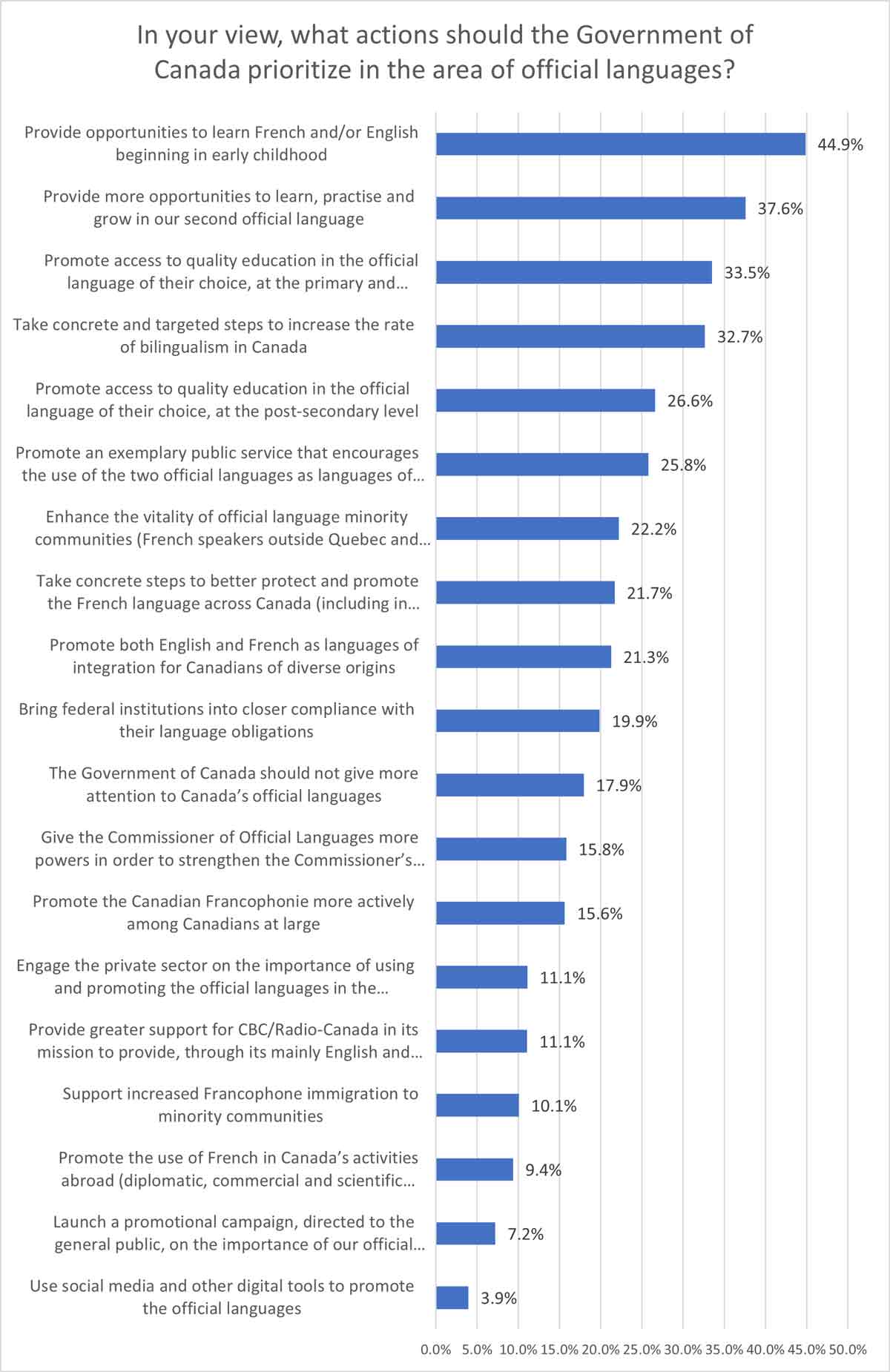

- Figure 22: In your view, what actions should the Government of Canada prioritize in the area of official languages?

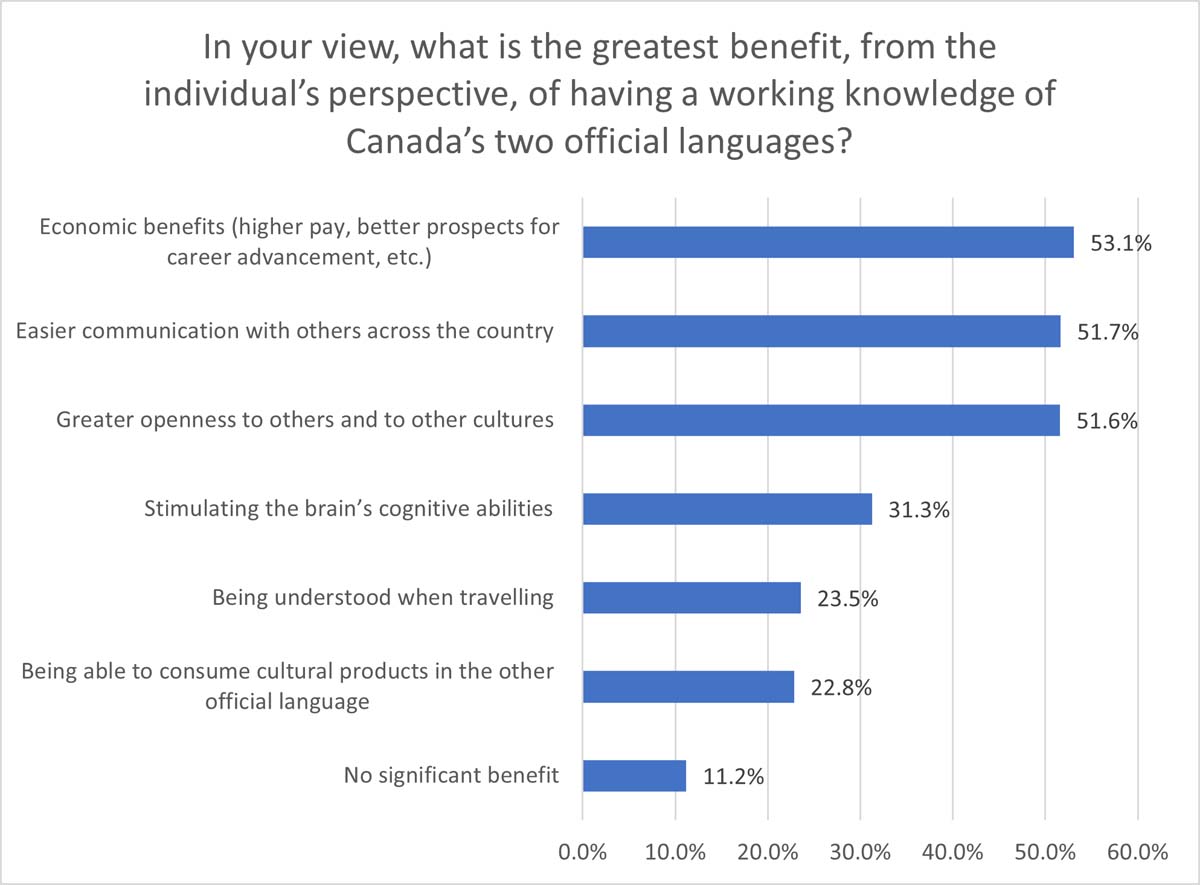

- Figure 23: In your view, what is the greatest benefit, from the individual’s perspective, of having a working knowledge of Canada’s two official languages?

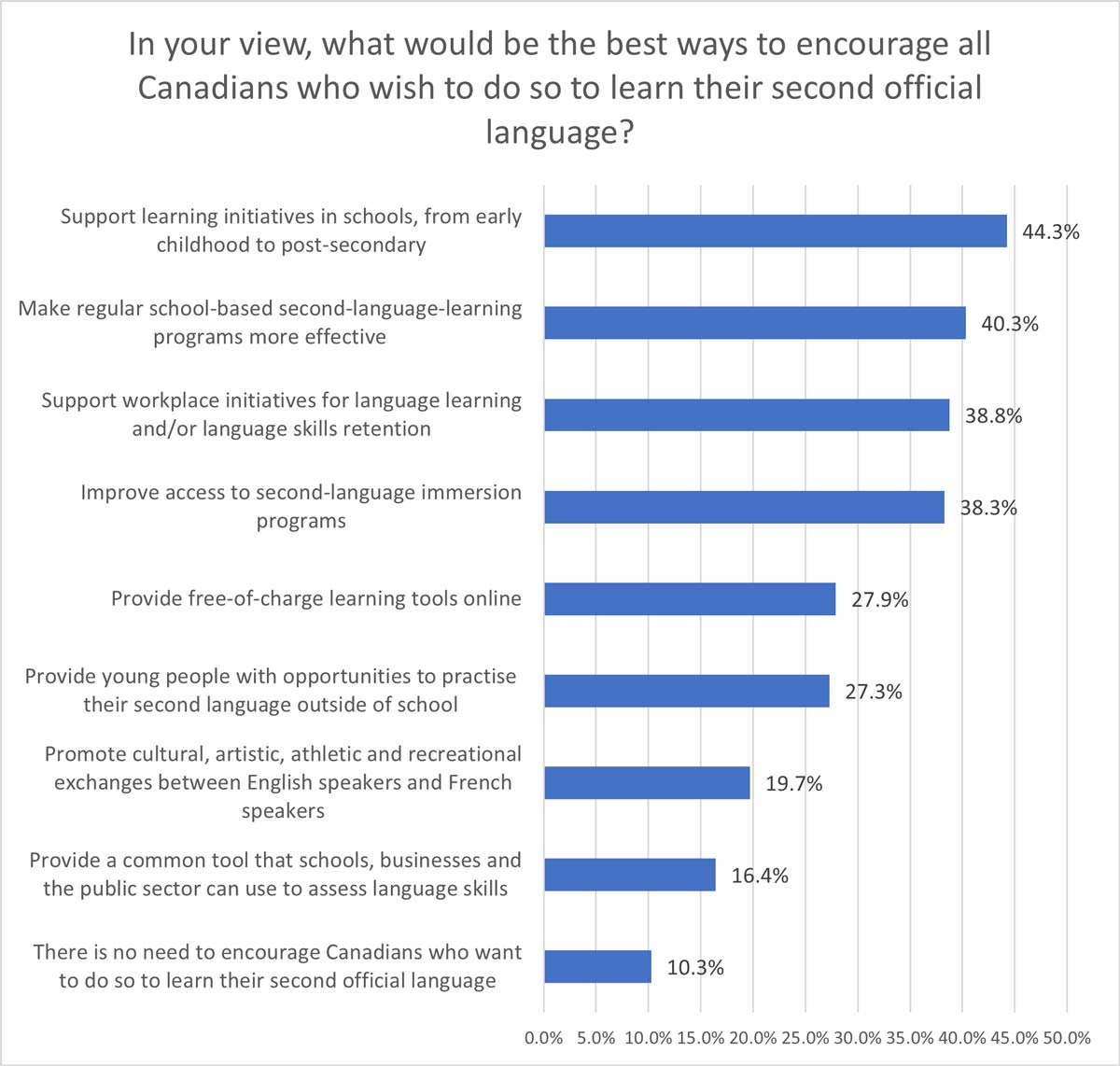

- Figure 24: In your view, what is the greatest benefit, collectively speaking, of having a working knowledge of Canada’s two official languages?

- Figure 25: In your view, what would be the best ways to encourage all Canadians who wish to do so to learn their second official language?

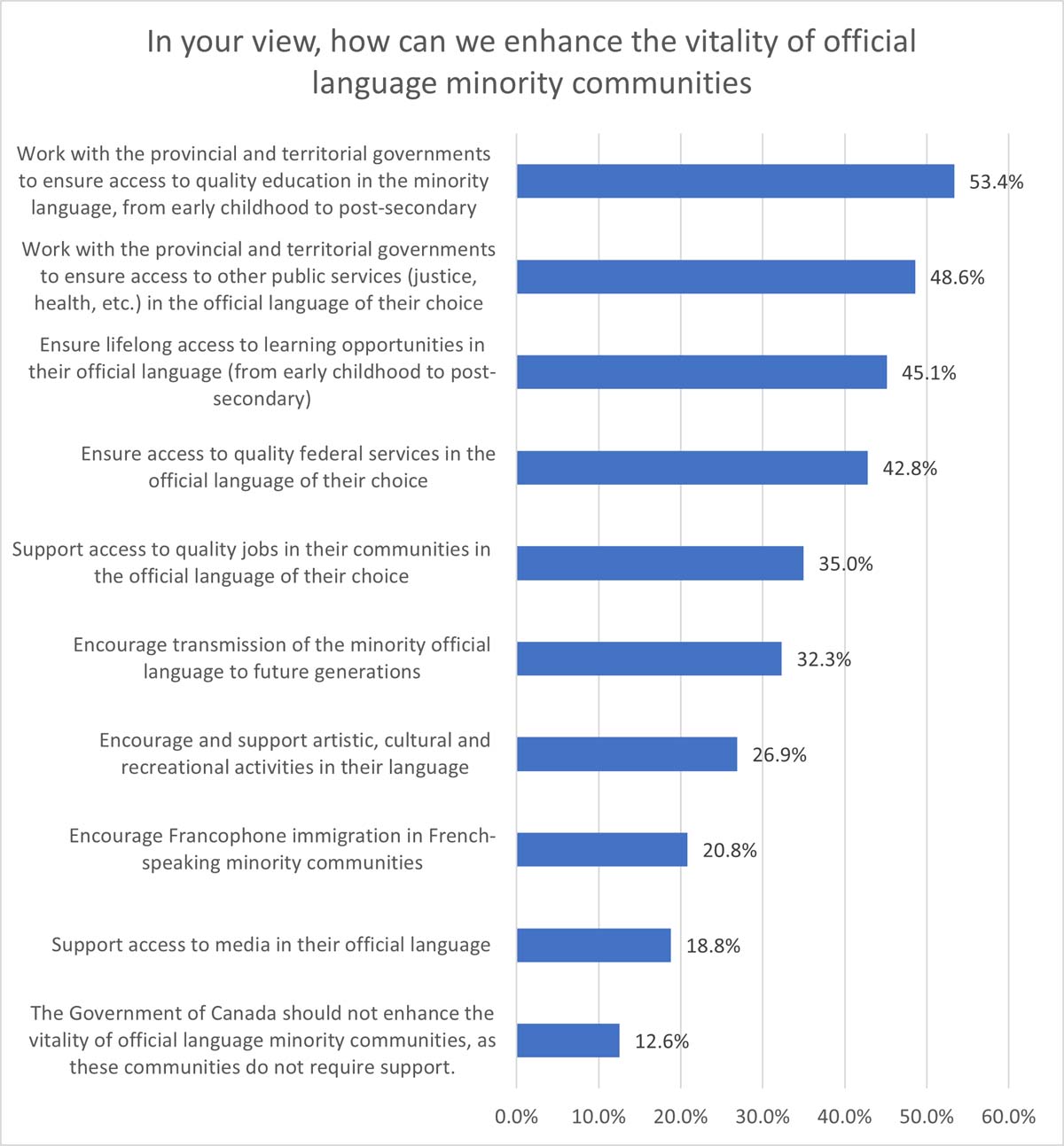

- Figure 26: In your view, how can we enhance the vitality of official language minority communities

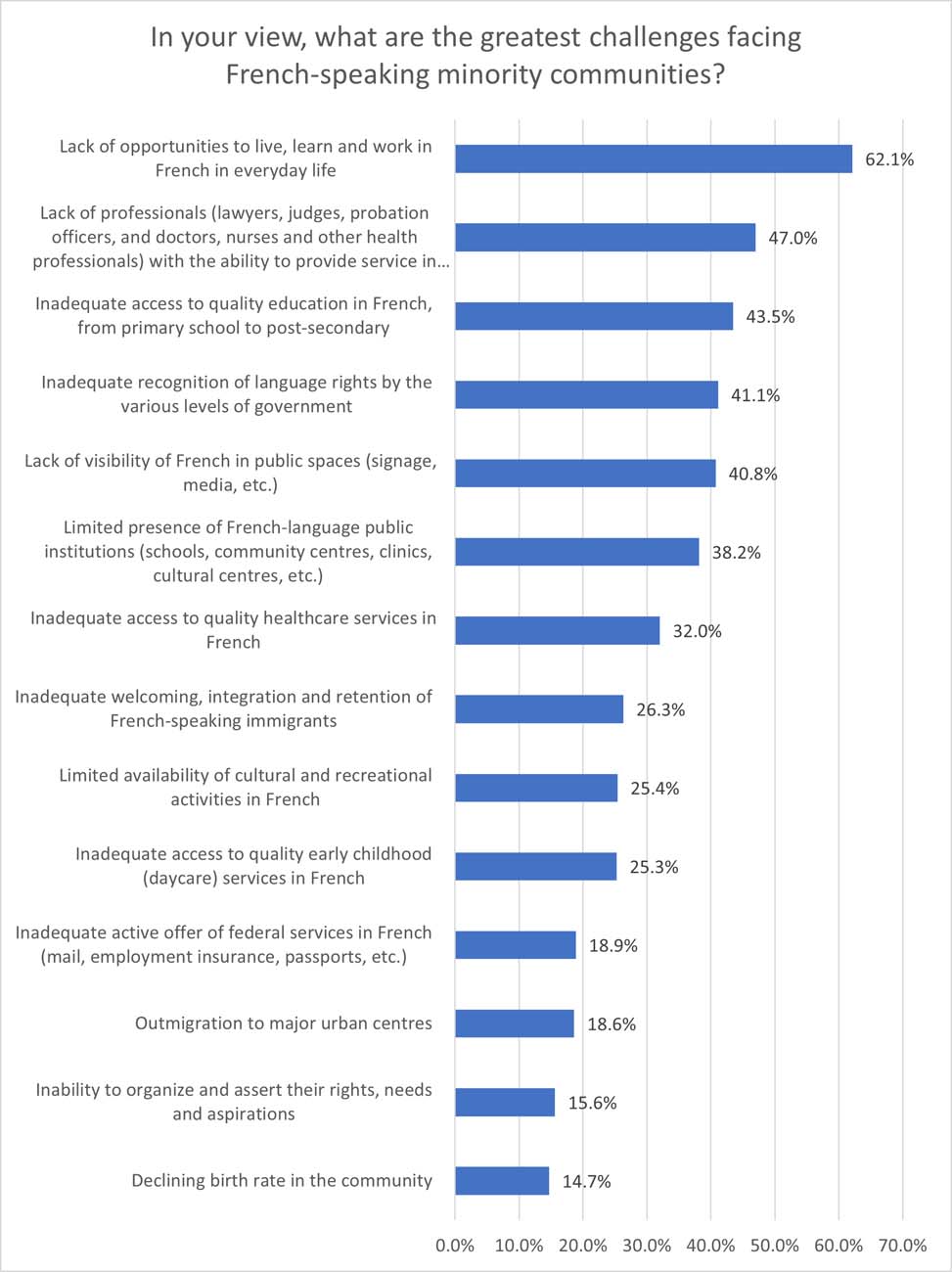

- Figure 27: In your view, what are the greatest challenges facing French-speaking minority communities?

- Figure 28: In your view, what would be the best measures for promoting awareness and recognition of the specific realities and priorities of French-speaking minority communities?

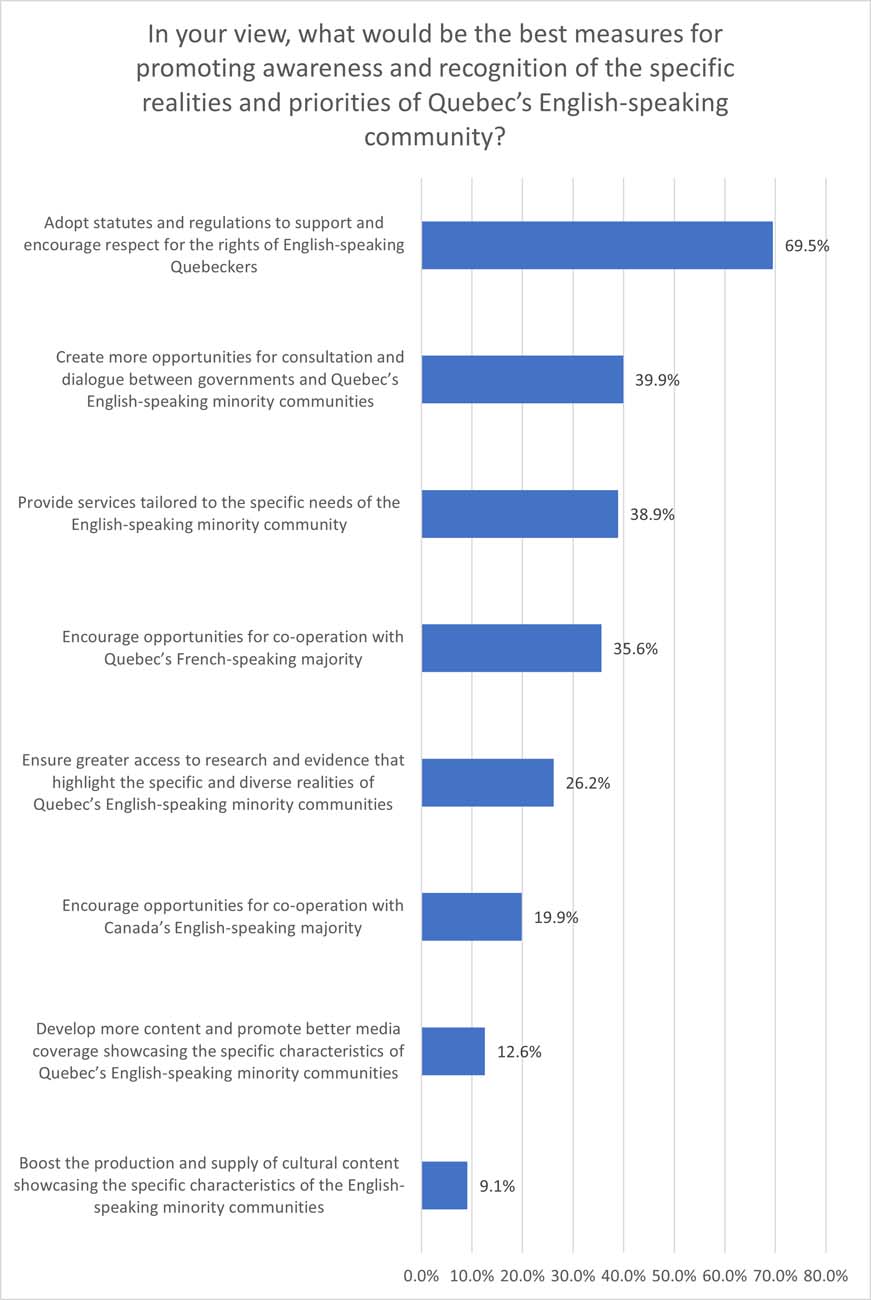

- Figure 29: In your view, what are the greatest challenges facing Quebec’s English-speaking communities?

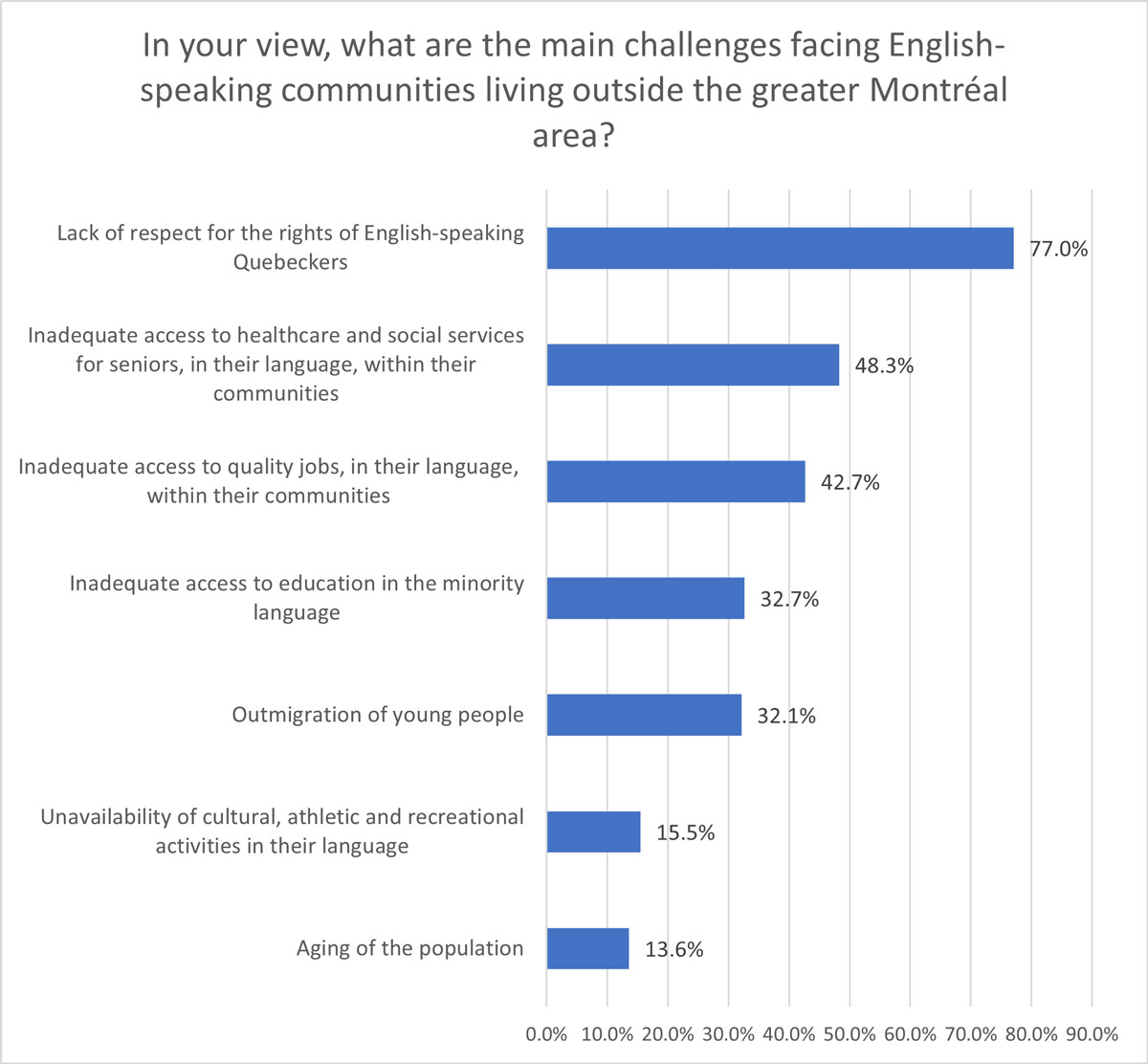

- Figure 30: In your view, what would be the best measures for promoting awareness and recognition of the specific realities and priorities of Quebec’s English-speaking community?

- Figure 31: In your view, what are the main challenges facing English-speaking communities living outside the greater Montreal area?

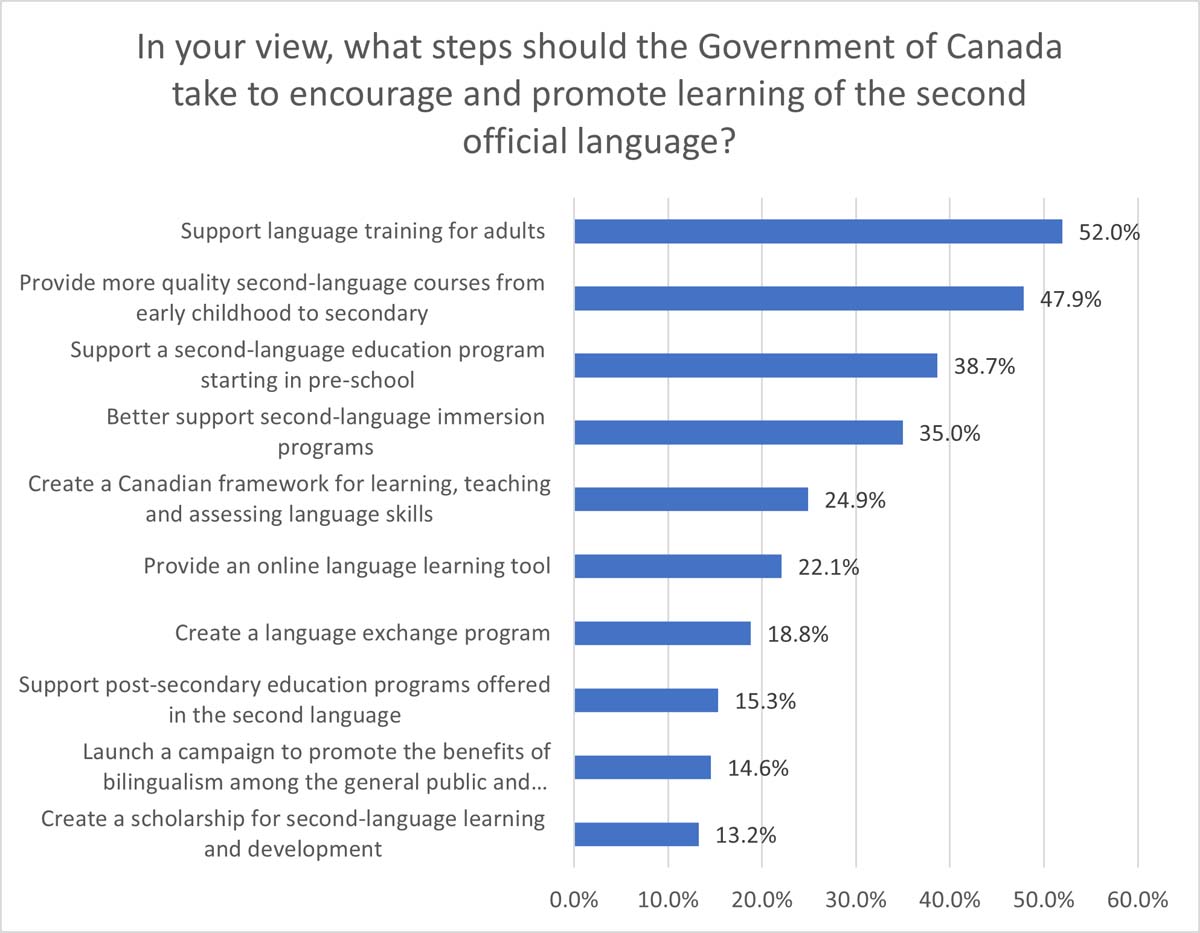

- Figure 32: In your view, what steps should the Government of Canada take to encourage and promote learning of the second official language?

- Figure 33: In your view, what key steps could be taken to showcase our two official languages?

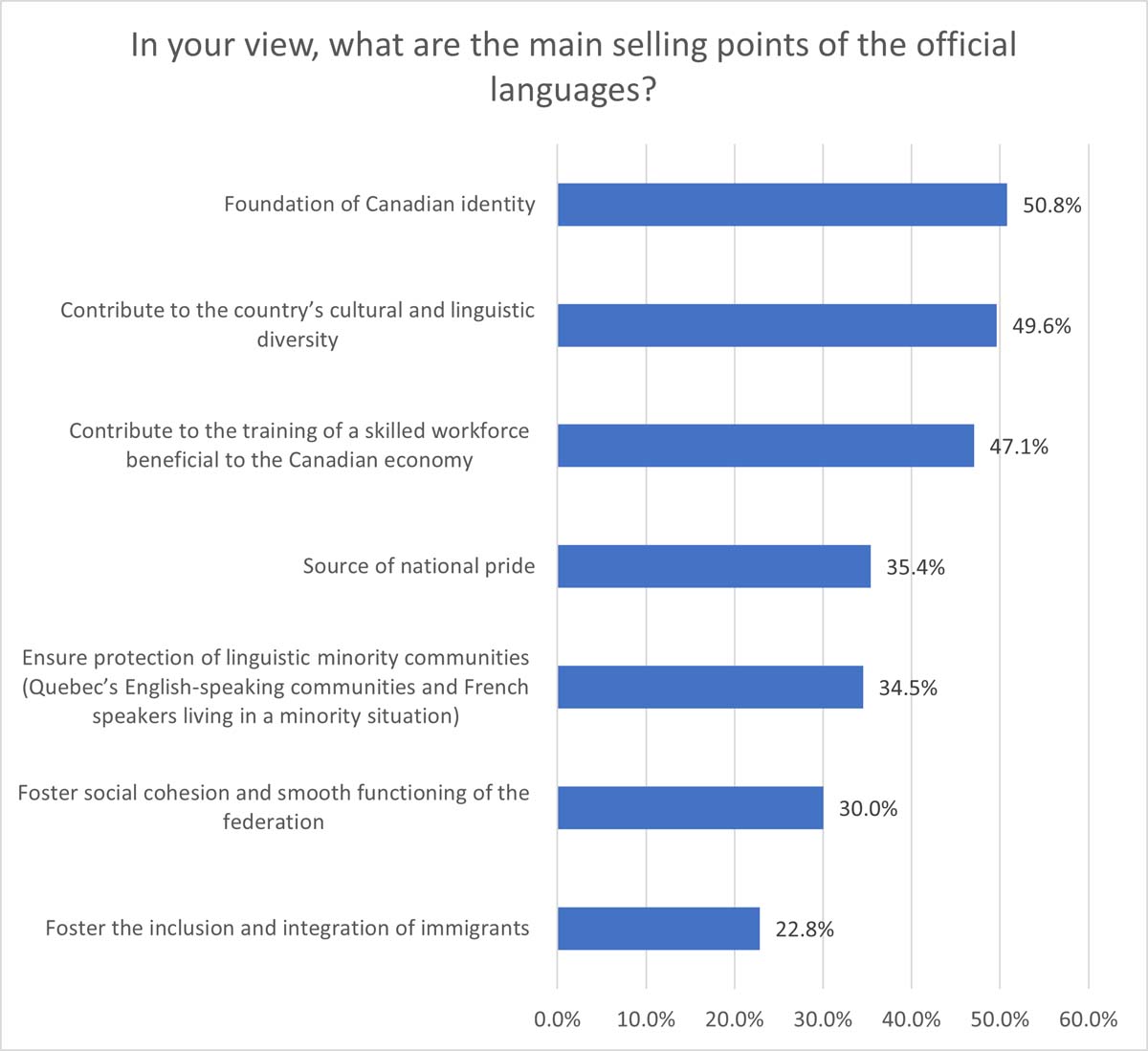

- Figure 34: In your view, what are the main selling points of the official languages?

Alternate format

Report on the consultations – Cross-Canada Official Languages Consultations 2022 [PDF version - 2.4 MB]

List of acronyms and abbreviations

- Action Plan 2018-2023

- Action Plan for Official Languages 2018-2023: Investing in Our Future

- Commissioner

- Commissioner of Official Languages

- ESCQ

- English-speaking communities of Quebec

- FCFA

- Fédération des communautés francophones et acadienne

- FMC

- Francophone minority communities

- OCOL

- Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages

- OL

- Official Languages

- OLMCs

- Official Language Minority Communities

- QCGN

- Quebec Community Groups Network

- Reform document

- refers to the reform document entitled English and French: Towards a substantive equality of official languages in Canada

Report on the Public Consultations – A Word from the Minister

The bilingual character of Canada means different things to different Canadians. For my part, I am proud to have grown up and to live in a bilingual city, a bilingual province and a bilingual country. Canada’s linguistic duality is part of my identity, just as it is part of the identities of millions of Canadians, and it was with this in mind that I embarked on the Cross-Canada Consultations. With the support of my Parliamentary Secretary, Marc Serré, I met with hundreds of people across the country who are passionate about the English and French languages. My goal was to learn about the issues and realities facing our two official languages.

After 15 consultations spanning all provinces and territories, seven virtual thematic discussions, a closing summit in Ottawa attended by upwards of 300 stakeholders from across the country, and an online questionnaire that received over 5,200 responses, I believe I now have a much more fulsome picture of Canada’s linguistic landscape. I would like to thank all those who participated in this broad consultation and all those who took the time to send in written submissions or recommendations. You have given me food for thought, and that input will help ensure that the next Action Plan addresses the major challenges communities face every day.

The message coming out of these consultations couldn’t be clearer: French is in decline across Canada, and official language minority communities face significant challenges in ensuring their survival and vitality. At the same time, we heard from English-speaking Canadians who are seeing the opportunities for their children to learn French as a second language slipping between their fingers due to a lack of funding for French immersion and French second-language programs in schools.

That being said, I would point out that, despite the challenges official language minority communities face, all are demonstrating resilience and innovation. I witnessed this in Edmonton during a visit to the Cité francophone, a welcoming space at the heart of the Albertan Francophonie where new Canadians, Francophiles as well as the “Franco-curious” can come together. I witnessed the same thing in Montreal during a visit to the English Language Arts Network, which provides support for English-speaking cultural creators and entrepreneurs. I also noted the entrepreneurial spirit of the Acadian community in southwestern Nova Scotia, where the Acadian World Congress will be hosted in 2024. Such success stories bode very well for the future of these communities.

In its reform document English and French: Towards a Substantive Equality of Official Languages in Canada and in Bill C-13—An Act for the Substantive Equality of Canada’s Official Languages—our Government made key commitments to support the protection and promotion of French across the country and to support the vitality of official language minority communities. Our next Action Plan (2023–2028) will give us the tools to realize our ambitions. My sincere thanks to all those who took part in these consultations and to the many communities that gave me so warm a welcome.

Ginette Petitpas Taylor

Minister of Official Languages and Minister responsible for the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency

Introduction

On August 25, 2022, the Honourable Ginette Petitpas Taylor, Minister of Official Languages and Minister responsible for the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency, concluded the 2022 Cross-Canada Official Languages Consultations at a summit held in Ottawa.

Between the launch of these consultations on May 24 and their official closure, close to 6,500 Canadians shared their views on the challenges facing official languages in Canada, discussed issues and recommended concrete courses of action for the next Action Plan for Official Languages (2023-2028), which the Government will be releasing in 2023.

This report outlines what we heard during these extensive public consultations.

The upcoming Action Plan 2023-2028 is the next major step in the official languages reform launched by the Government. It will build on the investments provided in Action Plan 2018-2023, but more importantly it will give effect to some of the major innovations in the Act to amend the Official Languages Act, to enact the Use of French in Federally Regulated Private Businesses Act and to make related amendments to other Acts (Bill C-13), which will modernize the Official Languages Act. Bill C-13 is currently going through the legislative process in the Parliament of Canada.

1. Federal government commitment – Modernization of the Act and the next Action Plan for Official Languages 2023-2028

On March 28, 2018, after extensive public consultations, the Government launched the Action Plan for Official Languages 2018-2023: Investing in Our Future. This Action Plan 2018-2023, the fourth five-year strategy in support of official languages, was also the first major reinvestment since the first Action Plan launched in 2003. It contained more than $500 million in new funding over five years to support some 20 permanent initiatives to strengthen our official language minority communities, improve access to essential services in both official languages, and promote a bilingual Canada.

The Government’s commitment continued in summer 2018, when the Prime Minister of Canada mandated the Minister of Tourism, Official Languages and La Francophonie to undertake the work leading to the modernization of the Official Languages Act. The Act was passed in 1969 and had not been substantially amended since 1988. Consultations and analyses followed, and in February 2021, a reform document entitled English and French: Towards a Substantive Equality of Official Languages in Canada (hereafter the reform document) was released, presenting Canadians with some 50 legislative, regulatory and administrative proposals for modernizing both the Official Languages Act and Canada’s overall language regime.

In particular, the Government proposed to take action to: provide all individuals with opportunities to learn English and French throughout their lives; support the key institutions of official language minority communities; protect and promote French throughout Canada, including in Quebec; and promote the Government of Canada’s leadership role by strengthening horizontal coordination and federal institutions’ compliance with the Act. Bill C-32, An Act to amend the Official Languages Act and to make related and consequential amendments to other Acts, introduced in June 2021, sought to put these commitments into action.

After the federal election in October 2021, the Honourable Ginette Petitpas Taylor, Minister of Official Languages and Minister responsible for the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency, was mandated to continue the work by introducing a new bill and establishing a new Action Plan for Official Languages.

On March 1, 2022, an enhanced bill was introduced in the House of Commons: Bill C-13, An Act to amend the Official Languages Act, to enact the Use of French in Federally Regulated Private Businesses Act and to make related amendments to other Acts. The adoption of this bill will allow for the implementation of the legislative and regulatory amendments proposed in the February 2021 reform document.

In May 2022, at the beginning of the consultation process, Canada’s Commissioner of Official Languages, Raymond Théberge, released a report entitled Monitoring the Implementation of the Action Plan for Official Languages 2018-2023: Investing in Our Future – Analysis and Recommendations for the Next Five-Year Plan. His recommendations, addressed to the Minister of Official Languages, fell into two broad categories: observations on each initiative, including education, immigration, local media; and overall observations on the next Action Plan 2023-2028, including the consultation process, federal institutions and administrative measures to support community organizations.

The next step is therefore to introduce the next Action Plan for Official Languages in 2023. This Action Plan will continue the work begun by the current Action Plan, but above all, it will put forward a series of measures and the funding necessary for the concrete implementation of the commitments and improvements contained in Bill C-13 and, more generally, in the reform document.

To prepare for this next step, federal institutions have been conducting a detailed assessment of the measures in the current Action Plan and looking for ways to improve administrative processes.

Minister Ginette Petitpas Taylor also undertook to consult her provincial and territorial counterparts in the context of her regular discussions and through a formal call for proposals. The Minister also launched the 2022 Cross-Canada Consultations to hear from as many Canadians as possible about the state of official languages in their communities, their successes, issues and challenges, and their outlook for the future, in order to develop an Action Plan that reflects the reality of our communities.

2. The 2022 Cross-Canada Official Languages Consultations

These consultations sought to reach and engage as many people as possible by combining virtual events with in-person meetings, inviting written comments online and reaching out to various stakeholders on the ground.

In total, between May 24 and August 31, 2022, close to 6,500 people provided comments and recommendations and shared their vision of the place that our two official languages have in Canada’s future.

The consultations began in May with the launch of a webpage dedicated to the consultation exercise. The page contained a discussion guide and detailed the various ways Canadians could participate.

An online questionnaire was also made available to Canadians. More than 5,200 people used this platform to share their views on the importance of official languages and official languages issues, in particular with respect to promoting the French language across Canada, supporting the development of official language minority communities, bilingualism and second-language learning, and the best way to reflect Canadian diversity and inclusion.

More than 80 people and organizations also presented written submissions presenting their observations and recommendations on these matters.

Between May 24 and August 9, 15 regional forums were held, giving Minister Petitpas Taylor and her Parliamentary Secretary, Marc Serré, an opportunity to meet with stakeholders on the ground in every province and territory. These in-person exchanges allowed representatives of official languages communities, organizations involved in promoting second-language learning, and other members of the communities visited to report on the issues in their region and suggest possible solutions. In total, close to 300 people responded to Minister Petitpas Taylor’s invitation.

| Date | Cities |

|---|---|

| May 24, 2022 | Vancouver, British Columbia |

| May 26, 2022 | Winnipeg, Manitoba |

| June 10, 2022 | Toronto, Ontario |

| July 6, 2022 | Montreal, Quebec |

| July 7, 2022 | Sherbrooke, Quebec |

| July 13, 2022 | Sudbury, Ontario |

| July 18, 2022 | Iqaluit, Nunavut |

| July 19, 2022 | Yellowknife, Northwest Territories |

| July 20, 2022 | Moncton, New Brunswick |

| July 21, 2022 | Whitehorse, Yukon |

| July 26, 2022 | St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador |

| July 28, 2022 | Edmonton, Alberta |

| July 29, 2022 | Regina, Saskatchewan |

| August 4, 2022 | Summerside, Prince Edward Island |

| August 9, 2022 | Halifax, Nova Scotia |

Alongside these in-person meetings, seven virtual thematic sessions were held in June and July to hear from key stakeholders on topics of importance for the next Action Plan and the official languages reform. In addition, on July 21, 2022, Minister Petitpas Taylor met with women from all over the country in a virtual consultation organized in collaboration with the Alliance des femmes de la francophonie canadienne (AFFC). In total, close to 600 people, interested individuals, academics and representatives of organizations, took part in these thematic sessions.

| Date | Theme |

|---|---|

| June 2, 2022 | Francophone immigration: Francophone immigration strategy and immigration continuum, demographic weight and vitality of French-speaking minority communities, and recognition of credentials |

| June 8, 2022 | Educational continuum: Early childhood, post-secondary, professional development, linguistic security, and sense of belonging |

| June 16, 2022 | Appreciation of English and French: Arts and culture, youth, seniors, and key institutions |

| July 4, 2022 | Official languages, diversity and inclusion |

| July 4, 2022 | Second language: Learning and promotion of a second language, and French immersion |

| July 5, 2022 | Protection and promotion of French: Private sector (including federally regulated private businesses), international and cultural diplomacy, and scientific knowledge |

| July 5, 2022 | Government leading by example, research, and knowledge about official language realities in Canada |

Lastly, the Minister invited many English and French speakers who are active in the official languages field to attend a closing summit at the National Arts Centre in Ottawa on August 25, 2022. The summit was an opportunity to celebrate our official languages, look back at the highlights of the consultations and consider new avenues and ideas to strengthen our official languages through the next Action Plan. Nearly 300 people from across the country participated in the summit.

The following pages summarize what we heard during these public official languages consultations between May and August 2022. However, this summary cannot do full justice to the abundance of testimonials from the people we met or the wealth of information and proposals in the written submissions. Thank you for sharing.

3. Outcome of public consultations: observations, comments and recommendations

3.1 Vitality and development of official language minority communities

The presence of French-speaking minority communities across Canada and English-speaking communities in Quebec reflects a rich history of the French and British extending and defending their languages across the land, adding to the existing wealth of Indigenous languages.

By choosing to live in their language, the 2.2 million members of official language minority communities demonstrate resilience every day. Through the networks of organizations that unite and represent them, through their school boards, and through their cultural and community institutions, these Canadians contribute daily to building strong, diverse communities in spite of the challenges.

Since the adoption of the first Official Languages Act in 1969, the Government of Canada has made support for these communities a pillar of its language policy.

The Cross-Canada Consultations provided an opportunity to discuss many aspects of the vitality of official languages communities and gather proposals and recommended courses of action for the next Action Plan for Official Languages 2023-2028. The pages that follow present what we heard under three broad themes: support for institutions and access to services in the language of the community; strengthening the educational continuum, from early childhood to post-secondary; and immigration as a means of addressing the demographic decline of Francophone communities. In addition, we will address the unique challenges facing Quebec’s English-speaking community.

3.1.1 Support for institutions and community services

Background

Access to services in one’s official language is one of the main challenges facing official language minority communities. Where such services are available, they quickly become the best way to ensure that the members of these communities can live, learn, work and thrive in their own language.

In the absence of minority-language organizations, institutions and services, there is no public space in which community members can live in their language and realize their full potential. The services in question are those offered by provincial or municipal governments, or the many community-based (or community-administered) organizations, such as school boards, child care centres, community health clinics and cultural organizations. These services not only play an important role in daily life, but are essential to the assertion and expression of cultural identity and sense of belonging. An official language minority community is only as strong as its institutions.

During the 2022 Cross-Canada Consultations, a majority (62%) of respondents to the online questionnaire identified the ability to live, learn and work in French in everyday life as one of the five greatest challenges facing Francophone minority communities. In addition, almost half (47%) of respondents felt that offering services tailored to the needs of these communities was one of the three measures that should be put in place to support community vitality. A similar proportion (48%) of respondents felt that access to English-language health care and social services for seniors was one of the top three challenges facing the English-speaking community outside the greater Montreal area.

Lifelong access to quality education in one’s first official language is certainly the bedrock of these essential services. We will discuss this further in the next section, which deals with the minority educational continuum.

In the pages that follow, we will share the comments and recommendations that we heard and received in numerous submissions on how the next Action Plan 2023-2028 could strengthen support for the network of community organizations and institutions, and support the development of, and access to, services in key sectors such as economic development, health and justice.

Bill C-13 commits all federal institutions to take concrete positive measures to support these sectors that are essential to enhancing the vitality of the communities, and to protecting and promoting the presence of strong institutions serving those communities. The next Action Plan 2023-2028 will be an opportunity to put this commitment into action.

Main courses of action recommended

Increase funding for community organizations and institutions

The topic of funding figured prominently in the regional/virtual consultations and in the submissions received. For the vast majority of community organizations, funding from various levels of government remains a critical factor in their ability to deliver services and programs and meet community needs. The need to increase core funding for organizations was emphasized across the board. Many stakeholders, particularly in Vancouver and the northern territories, called for government support to be adjusted to reflect the high cost of living in these regions. Also across the board, there were calls for a comprehensive plan to keep pace with inflation in order to make up for what the Fédération acadienne de la Nouvelle-Écosse (FANE) characterizes in its written submission as community organizations’ “loss of power to act.” Many called for a re-examination of the way federal funding is distributed to the various communities and for departments to demonstrate transparency in this respect.

Implement a strategy to address labour shortages

The challenges of recruiting and retaining skilled workers in community institutions and organizations are of concern to stakeholders in every community. The issue is particularly acute in smaller communities, such as in the territories or in Newfoundland and Labrador, where the public and even the private sector are offering better wages for bilingual employees. The labour shortage is making it very difficult to serve the population, submit project applications, and even carry out funded projects and complete the associated reporting. The Fédération des francophones de la Colombie-Britannique (FFCB) has therefore requested that the next Action Plan 2023-2028 contain a human resources strategy. Funding for community organizations must be increased so they can compete in the marketplace and offer competitive wages to their employees. In its written submission, the Assemblée de la francophonie de l’Ontario (AFO) suggested rethinking federal support to ensure that grants to organizations at least allow for adequate wages for three employees for provincial organizations and one employee for local and regional organizations. Stakeholders in Summerside, Prince Edward Island, suggested establishing a fund to encourage young Francophone and immersion high school graduates to join the French-language workforce. It was also suggested that interested seniors be encouraged to return to the workforce.

Streamline administration and provide stable, long-term funding rather than project-based funding

A majority of community stakeholders across Canada called for Canadian Heritage and other funding agencies to review their funding formulas and reduce their reporting requirements. In particular, it was noted that project-based funding puts organizations in a precarious and unstable position. Promising projects have to be shelved because of a lack of recurring funding or a lack of human resources to administer a new funding application. In Halifax, for example, it was noted that completing a funding application requires 80 to 100 hours of work, which is too onerous, especially for small organizations. It was suggested that the application process be simplified and funding be awarded on a multi-year basis so that organizations have the flexibility and resources to better plan programs. A shift from project based funding to stable core funding was requested. In its submission, the FFCB also suggested that departments harmonize their administrative requirements to reduce the administrative burden.

Invest in new community infrastructure

A number of stakeholders stressed the importance of investing in gathering places to strengthen communities and facilitate service delivery. For example, they lamented that the absence of a community or cultural centre for Francophones in Yellowknife had resulted in a lack of recreation and essential services for Francophones and Francophiles. It was pointed out that the lack of a Francophone cultural centre in Saskatchewan is detrimental to the promotion of the Fransaskois culture in this community, which is spread out over a large geographic area. In Halifax, it was argued that the creation of a community centre would help revitalize the community and foster closer ties with Francophiles by providing a space to interact in French. Youth who are part of Quebec’s English-speaking community also lamented the lack of community spaces where they can gather and share. The presence of community and cultural infrastructure brings together and provides visibility for the community, promotes language use and cultural transmission, and encourages community members, youth in particular, to stay in the community.

Support access to media, arts and culture

In addition to requests for new cultural and community infrastructure, support for arts and culture was raised at several regional tables. Some stakeholders welcomed the recognition of culture in Bill C-13, as arts and culture are important drivers that unite and connect communities. However, stakeholders expressed concern that cultural organizations often remain fragile, particularly in smaller communities, owing to a lack of stable and adequate funding. Even in larger centres, as was noted in Toronto, organizations can be fragile because of competition with other cultural events. In its written submission, the Fédération culturelle canadienne-française (FCCF) proposed that the next Action Plan 2023-2028 increase core funding for these organizations to strengthen the capacity of the arts and culture ecosystem. The FCCF also suggested putting in place a paid internship program in the arts and culture sector and supporting community-based cultural entrepreneurs through Regional Development Agencies. Lastly, it suggested creating a data observatory on arts and culture in the Canadian Francophonie.

The fate of community media was also raised. These media are seen as flagship institutions because of the visibility they bring to the community, but in the digital age, many radio stations and newspapers are facing difficult times. Community media, in both Quebec and Francophone communities, called on the federal government to provide them with adequate core funding so they can continue to serve their communities by showcasing their language, culture and heritage.

Support economic development initiatives

Several community representatives emphasized that economic development is essential to community vitality and that investments in this sector can yield significant returns. In particular, economic integration is crucial to attracting and retaining immigrants. Moreover, participants noted that special attention should be given to minorities in the community, such as women or racialized people who need additional support to integrate into the labour market. In Saskatchewan, it was suggested that to support recruitment efforts, a directory of Francophone jobs for individuals located in the province, in Canada and worldwide be created. The Réseau de développement économique et d’employabilité (RDÉE Canada) proposed investing in strengthening the entrepreneurial capacities of communities and reinforcing specialized sectors, such as tourism, sustainable development, youth and early childhood. In Manitoba and New Brunswick, the suggestion was also made to invest in tourism and showcase the communities’ culture and heritage. Quebec’s English-speaking community pointed out that English speakers in Quebec have higher unemployment and poverty rates than the province’s French-speaking population and that their community’s vitality depends on its economic vitality. A proposal was made to increase support for community organizations that encourage innovation and entrepreneurship, particularly among immigrants. The federal government was also urged to support French-language training for English-speaking residents of Quebec as a way to increase their employability. Lastly, stronger collaborations with majority organizations were proposed.

Improve access to health care in the language of the community

Regional table participants noted that across the provinces, there are major differences in access to health care in the language of the community, with negative consequences for people’s well-being. The impact of the lack of health care in one’s own language is reflected in a significant health deficit among the most vulnerable populations, particularly seniors. In several provinces, it was lamented that information and services related to the COVID-19 pandemic were not available in French. In the aftermath of the pandemic, it is the availability of adequate mental health services that is of concern to community members, be they in Edmonton, Winnipeg, Sherbrooke, Moncton or Halifax. The fragility of community institutions working on the front lines was stressed. The Quebec Community Health and Social Services Network (CHSSN) pointed out that the community-based service-access-network model had proven its worth in Quebec and in the Canadian Francophonie, and suggested that they be given the means to better reach remote communities. Stakeholders also proposed including language clauses in federal-provincial agreements on health to compel provincial and territorial governments to increase the availability of services. At the Sherbrooke meeting, it was suggested that interprovincial exchanges of specialists be facilitated to address the shortage of English-speaking specialists in Quebec and French-speaking specialists in the other provinces. Similarly, the Official Languages and Bilingualism Institute (OLBI) at the University of Ottawa proposed establishing a specialized second-language program for health professionals.

Improve access to justice

According to some stakeholders, one of the major gaps in government services to Francophone communities is the accessibility of provincial courts and legal services in French. There is a need for more judges who are actually able to hear a case in French, without the need for an interpreter. It was also noted that legal aid in French, or in English in Quebec, is often lacking and there is a need for more support for community organizations that help people navigate the justice system. The Association des juristes d’expression française du Nouveau-Brunswick (AJEFNB) and other stakeholders called for increased funding for lawyers’ associations. The Association des collèges et universités de la francophonie canadienne (ACUFC) called for support for the development of various justice professionals and an increase in the capacity of post-secondary institutions to offer programs in law and justice. Like the OLBI, the ACUFC supports the idea of specialized second-language training for justice professionals. Lastly, the Alliance des femmes de la francophonie canadienne (AFFC) noted that the problem of violence against women worsened during the pandemic, and asked the federal government to fund services for women victims of violence.

Include municipalities in the offer of services

Municipal governments are often best positioned to provide community-based services to their residents. This is also true for minority language services. The Association des municipalités bilingues du Manitoba (AMBM) therefore called for Bill C-13 to reaffirm and strengthen the federal-municipal partnership on official languages and for the next Action Plan 2023-2028 to include a funding program to strengthen the capacity of municipalities to offer services in both official languages.

3.1.2 The educational continuum, from early childhood to post-secondary and beyond the classroom

Background

The importance of education for the vitality and sustainability of official language minority communities is well established. Schools and educational institutions, some of which had to be fought for over several decades, are now at the heart of these communities. They are their rallying point, their best tool for transmitting language and culture.

Access to primary and secondary school instruction in the minority language is a right guaranteed by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (section 23). This right includes the right of the community to manage its education system. Today, minority language school boards manage their programs and schools in every province and territory in the country.

But there is still work to be done. First, the quality and substantive equality of minority language education must be improved, and second, access to the entire educational continuum must be expanded through the development of early childhood services, on the one hand, and post-secondary education, on the other. As an essential support for families, which are increasingly exogamous (where the parents do not share the same mother tongue), child care in the language of the community is the surest way to reinforce the transmission of language and help the child integrate into the minority language school system. Also, giving high school graduates access to post-secondary education in their own language and in their own community solidifies the use of that language and allows the community to retain its talent or attract new talent. Lastly, some community members, like the rest of the population, have literacy problems and often have less access to continuing education programs that would allow them to increase their employability.

For decades, the federal government has been working with the provinces and territories and helping fund minority language education. Bill C-13 commits the federal government to strengthening opportunities for community members to receive quality education in their own language “throughout their lives, including from early childhood to post-secondary education.” It also requires federal institutions to take concrete positive measures to protect and promote the presence of strong institutions in sectors that are essential to enhancing the vitality of the communities, including institutions working in the educational continuum.

For respondents to the online questionnaire administered in the course of our consultations, working to ensure access to quality education in the minority language from early childhood to post-secondary education (53%) and providing lifelong learning opportunities (45%) are among the most important measures to prioritize, ahead of the provision of other public services. However, respondents recognized that this is one of the greatest challenges facing English-speaking (33%) and French-speaking (44%) minority communities.

The importance of developing, strengthening and investing in the educational continuum was discussed at all regional tables and in many submissions. More broadly, there was frequent mention of fostering lifelong learning. A virtual thematic session was also devoted to these issues. The pages that follow outline the main challenges and potential solutions identified during the public consultations in terms of strengthening the educational continuum.

Main courses of action recommended during the consultations

Catch up on federal funding for minority language education

Collaboration between the federal government and the provincial and territorial governments is crucial to making progress on the minority language educational continuum. However, the Fédération nationale des conseils scolaires francophones (FNCSF) expressed concern that funding for intergovernmental agreements on education has remained unchanged since 2009, despite cost of living increases (35%) and significant enrolment increases (20%). In its written submission, the FNCSF therefore suggested that the Government prioritize minority language education and reinvest significantly in these agreements. In addition, stakeholders called for agreements with the provinces and territories to include detailed language clauses that take into account community needs and provide for transparent accountability mechanisms.

Review school funding in small communities

In several provinces and territories, participants reported underfunding of small schools, particularly in rural and remote areas, as provincial funding is often proportional to the number of students. Less funding makes these schools less attractive and makes it more difficult for them to attract students and fulfill their mandate. In addition, the lack of nearby high schools often means that students are lost to the majority system. Lastly, these small schools are facing increased challenges in recruiting and retaining the human resources they need to operate, in a context where all school systems are dealing with teacher shortages.

Invest in school infrastructure at all levels of the continuum

Most stakeholders cited a lack of capacity or inadequate infrastructure to support continuity of school instruction, including at the primary and secondary levels. For the FNCSF, improving infrastructure is the priority of minority-language school boards. It was noted that while the school population and the need for child care services are constantly growing, the facilities remain the same. The facilities are too small or outdated, or they simply do not exist, especially in rural areas.

Increase the availability of post-secondary programs in the communities

All stakeholders across the country agreed that post-secondary institutions have a powerful and transformative impact on their communities. They are crucial to the transmission of knowledge, as well as the community’s development and its ability to attract and retain people. They help train the workforce for the school system, as well as the early childhood and health sectors.

Stakeholders in regions that do not have access to post-secondary education (Yukon, Nunavut, and Newfoundland and Labrador) noted that this situation is forcing their youth to leave for other parts of the country or to study in English. Similarly, stakeholders in Western Canada and Ontario in particular pointed out that the lack of diverse program offerings often has the same result (youth out-migration). It also prevents Francophone institutions from attracting more students, notably immersion students.

There were calls for major investments to increase the availability of high-quality programs in Francophone institutions that provide learners with technical skills and knowledge to prepare them for the labour market. There were also calls to expand post-secondary education opportunities in regions without institutions. The disappearance of several French-language programs in Northern Ontario, Alberta and Manitoba owing to institutions’ financial problems or major provincial budget cuts was cited. The Assemblée de la Francophonie en Ontario (AFO) led the calls for multi-year, inflation-adjusted core federal funding for minority post-secondary institutions. As with community organizations, it was pointed out that project-based funding rather than recurring grants is a barrier to the institutions’ survival. To solve this problem, the AFO proposed creating a Francophone university network to increase collaboration between institutions, increase program offerings and help serve all regions. Lastly, there were calls for federal-provincial agreements on education to contain guarantees of transparency and accountability to protect investments in post-secondary education.

Award mobility bursaries and bursaries for students wishing to study in French

Stakeholders across the country and organizations such as the Association des collèges et universités de la francophonie canadienne (ACUFC) proposed increasing investments in bursaries as a way to support, and remove barriers to, post-secondary education in French. For example, it was proposed that mobility bursaries be offered to support students who, because of a lack of institutions or programs in their community, are forced to choose between studying in French in another region and enrolling an English-language institution. More bursaries were also proposed to encourage English-speaking students, often from immersion, to attend minority French-language institutions.

Attract and retain foreign students

Francophone international students are a large segment of the student population and contribute significantly to the communities’ post-secondary institutions. Consultation participants called for immigration and education policies and programs to take into account ways to better serve this community. In particular, they called for increased access to study permits and the creation of bursaries for international students who choose to study in minority French-language institutions. Lastly, they called for the recognition of foreign credentials to be made easier to help immigrants integrate into their studies or the workforce.

Provide for the creation of more child care spaces in minority communities

Many communities reported a critical shortage of subsidized and private child care spaces. In Francophone communities in particular, early childhood in French is seen as the cornerstone of language transmission, identity building, and development of future generations of Francophones. The lack of French-language child care services and excessive waiting lists still too often force children to attend child care in English, which is often a determiner of subsequent school choice. Stakeholders expressed concern about Francophones’ access to federal investments. For example, none of the early childhood education centres in British Columbia are participating in the $10/day child care initiative. In Winnipeg, it was noted that the province does not fund preschool education in French. English-speaking stakeholders in Sherbrooke reported a similar problem and criticized the lack of access to subsidized English-language child care. Many stakeholders across the country called for federal-provincial agreements to contain language clauses requiring funding in official language minority communities.

Concerns were also raised about the project-based funding model on which many community-based child care centres depend. For example, it was noted that in Alberta, small one-time projects have doubled the number of early learning and child care spaces (from 600 to 1,200) but these spaces are now at risk if funding is not guaranteed. Calls were made for a review of support mechanisms and access to ongoing core funding. In response to the project-based funding model, the Commission nationale des parents francophones (CNPF) recommended to the federal government a more structured, strategic and long-term funding program for community child care centres.

Create a consortium for early childhood training

In its written submission, the ACUFC proposed creating a consortium for early childhood training similar to what exists in the health field. By pooling and coordinating the efforts of a large number of post-secondary institutions, such a consortium would improve basic training in the field, make it available across the country and encourage an increase in the number of Francophone early childhood educators. It would support initiatives tailored to provincial, regional and territorial realities and would contribute to the mobilization of knowledge and to research on early childhood in minority settings.

Recognize the full value of the profession of educator

Early childhood stakeholders expressed concern that the recruitment and retention of highly skilled educators is a major systemic problem in official language minority communities. Burnout among trained, skilled and specialized staff is a serious issue. A high proportion of bilingual child care staff are also reportedly leaving the French-language system for English-language programs where their profession is often better recognized and better paid. There is a need to recognize the early childhood educator profession, the skills required to do the job, and the importance and value of educators’ professional work, and to make the necessary investments to ensure they are adequately paid.

Support adult education and literacy as part of the continuum

Education and instruction, according to many stakeholders, is a lifelong process. However, there are few services and initiatives available to seniors in the communities, even though they represent a growing proportion of the population. According to a 2012 Employment and Social Development Canada study published in the report Skills of Official-Language Minority Communities in Canada (2021), Francophones in minority settings who speak French at home “have lower literacy scores than those who speak English. … However, Quebec anglophones who speak English most often at home have higher literacy scores” (p. 2).Footnote 1 Thus, there are many people in the communities who have limited literacy and numeracy skills and who do not have access to literacy services in their own language, which greatly limits their participation in the workforce. It was suggested that French-language literacy organizations be integrated into the educational continuum and receive adequate support. In Quebec, there were also calls for continued support for adult education, particularly to help English-speaking adults learn French.

3.1.3 Francophone immigration

Background

Canada is a country that relies on immigration for its economic and demographic development, but not all communities in the country benefit equally from this added value. Francophone minority communities have called for Francophone immigration targets outside Quebec to be increased and met in order to maintain or increase the demographic weight of those communities. However, promoting Francophone immigration abroad has its challenges, and to strengthen our recruitment approach, we must also work on our integration efforts.

In 2019, a Francophone Immigration Strategy was launched to strengthen the immigration continuum, from attraction to selection and retention, for French-speaking newcomers outside Quebec. One objective of the Strategy is to bring Francophone immigration in Canada outside Quebec up to a target of 4.4% by 2023. The Strategy has already yielded promising results: in 2020, admissions of French-speaking permanent residents outside Quebec rose to 3.6% compared with 2.8% the previous year. The Strategy is currently being evaluated.

Bill C-13 requires the adoption of a Francophone immigration policy that includes objectives, targets and indicators, as well as a recognition of the issue of the demographic weight of Francophone minority communities and the important role of immigration in countering this decline. The bill underscores the importance of a government-wide effort to address this challenge.

The Cross-Canada Consultations gave prominence to this issue. Immigration was raised in the vast majority of regional forums and in many written submissions. A virtual thematic session was also devoted to the topic. Although just over a quarter (27%) of respondents to the online questionnaire identified the reception, integration and retention of immigrants in Francophone communities as one of the five main challenges to vitality, participants in the various forums agreed on the importance of strengthening government action and made proposals to achieve this. It was also pointed out that the Government of Canada must provide leadership in this area.

Main courses of action recommended

Develop a robust plan to meet targets

Many stakeholders indicated that the Government should adopt more concrete tools to increase Francophone immigration outside Quebec, believing that it had not met its targets to date. Stakeholders called for an ambitious Francophone immigration policy designed to restore the demographic weight of Francophone communities by 2036 and increase it thereafter. According to stakeholders, such a policy should give the communities the means to participate in all stages of the promotion, recruitment, reception and integration of French-speaking immigrants. It was also suggested that the immigration targets be tailored to each provincial community (for example, aim for a target of 32% for New Brunswick) and that the policy put in place new measures adapted to the realities of communities such as Nunavut. Nevertheless, a national target for Francophone communities outside Quebec is again required and strongly recommended.

Increase funding for community organizations providing reception and integration services

Participants underscored the important role of community organizations in receiving and integrating newcomers. Governments must provide more funding options for immigrant-serving organizations, including multi-year funding to stabilize their workforce and relieve them of the need to submit short-term projects. It was noted that organizations in this sector often have to undertake costly marketing initiatives that extend beyond Canada’s borders and require larger investments.

Improve stakeholder awareness

A number of stakeholders stressed the importance of better informing and raising awareness among the various immigration stakeholders. In particular, they want to make immigrants themselves more aware of the opportunities to live, study and work in French in the various communities. They also stressed the importance of getting English-language integration organizations to refer Francophone immigrants to Francophone integration networks.

Enhance the delivery of services for newcomers

As one Sudbury stakeholder commented, there is a close relationship between the language in which newcomers receive services and the language they choose for their children’s schooling and the community they join. The needs are great when it comes to ensuring newcomers’ social and economic integration. It was noted that in addition to access to schooling in their first official language, they need access to child care, affordable or subsidized housing policies, access to health care and access to justice. As the Alliance des femmes de la francophonie canadienne (AFFC) pointed out, these challenges are even greater for immigrant women. Even where some of these services exist, it is sometimes difficult to access them, especially outside the major centres. Some participants suggested making life easier for newcomers by creating hubs that combine all the services offered in French or by creating a clear “map” of these services. In Toronto, several participants spoke of the importance of informing Francophone immigrants, on their arrival at Pearson Airport, of the available French-language services and resources. In short, strengthening the Francophone integration pathway is essential in this respect.

Facilitate the recognition of credentials

Because of labour shortages in all fields, but particularly in health, facilitating the recognition of credentials of people coming from abroad, but also from other regions of Canada, was felt to be essential. It was nevertheless recognized that this issue is complex and goes well beyond the mandate of the Department of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship, requiring the support of federal partners, provincial governments and the collaboration of professional associations. A firmer and more concrete commitment would not only facilitate the integration of newcomers but would also help improve the availability of French-language services for the entire community. Similarly, it was suggested that Canada develop its own language proficiency tests rather than using tests made in France or the United States, and that it increase the availability of tests in French.

Facilitate the recruitment and retention of international students

It is generally estimated that 80% of international students remain in Canada after graduation. Representatives from the Université de Hearst in Ontario estimate that close to 50% of their international graduates settle in their community. Participants felt this contribution was essential to the vitality of Francophone communities and called for more efforts by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) and Global Affairs Canada to support the recruitment of international students, particularly from French-speaking Africa, and urged the Government to make it easier for international students to obtain permanent residence once they have completed their studies. In particular, it was proposed that study permits be more readily accepted and barriers to the students’ participation in job training opportunities such as internships be removed.

Focus on employability and entrepreneurship

In its written submission, RDÉE Canada proposed creating a distinct Francophone immigration pathway for minority settings focusing on employability matters and entrepreneurship. In particular, it was proposed that Francophones be recruited within the various categories of temporary foreign workers and that it be made easier for them to obtain permanent residence.

Promote the Express Entry system to Francophone and Francophile employers to manage immigration applications from skilled workers

Access to employment is seen as critical to the effective placement of newcomers to Canada, as well as in addressing the skills shortage. As small businesses employ the largest share of people in Canada, it is important to reach out to them and include them in conversations about the appreciation of English and French within their work cultures and with their employees. Francophone immigration is seen as an excellent solution to address labour shortages in many fields and to promote French-language culture in workplaces, small businesses and public spaces.

Better meet the needs of increasingly diverse immigrants

Today, immigrants from more than 50 countries have integrated into Francophone communities and represent a growing asset. Participants noted, however, that many challenges arise when trying to serve this diverse community. According to them, the design of immigration services and support programs must take an intersectional approach and recognize the complexity of an immigrant’s identity. In communities in Western Canada and Ontario, the strong growth in Franco-African immigration was highlighted, as was the need to pay particular attention to the specific needs of this community, especially its women. It was emphasized that the services tailored to these newcomers need to be developed using an anti-racist lens to ensure successful integratation into the community. To better accommodate immigrants from Africa, it was recommended that IRCC open a second visa office on that continent. Lastly, participants from Ontario called for Canadian Heritage to increase its support for the organizations of racialized communities in the province.

Increase support for learning English

Learning English and French is seen as an important part of the newcomer experience, including their successful integration and retention. Participants underscored the need to better support Francophone newcomers in learning English. This will allow them to better integrate into their communities and make them more employable, thus contributing to a more bilingual workforce.

Increase intergovernmental and interdepartmental co-operation

Some stakeholders commented that Francophone immigration services are fragmented and called for a comprehensive approach. Given the magnitude of the challenge and the variety of services required, they recommended better co-operation among federal departments and with provincial and territorial governments. Some even went so far as to suggest that, to receive the attention it deserves, Francophone immigration should be included in the mandate letters of all federal ministers.

3.1.4 Particular issues facing Quebec’s English-speaking community

Background

English speakers in Quebec number over 1.25 million (first official language spoken) and form the only English-speaking minority in Canada. The community is bilingual and deeply rooted in the history of Montreal and Quebec’s various regions, from the Eastern Townships to Gaspésie to the Outaouais to the Lower North Shore. Although the community is concentrated in the greater Montreal area, nearly 250,000 of Quebec’s English speakers live in other parts of the province, where their situation is often much more precarious.

As we heard throughout the forums and thematic sessions and in some written submissions, Quebec’s English-speaking community shares many of the concerns and challenges of Francophone minority communities. While English speakers in Quebec recognize that, unlike French speakers, the use of their language is not under threat in the province, they share a deep concern about their community’s vitality.

Like French speakers, English speakers in Quebec called for an increase in core funding for organizations that play a key role in engaging, and delivering services to, the community, but they also called for support for the community’s capacity to develop policy. As with French speakers, there were calls for greater transparency in the use of federal funding and the inclusion of binding language clauses and accountability requirements in federal-provincial agreements.

The English-speaking community also faces significant challenges in accessing health services, in particular mental health services, as well as social services, and early childhood and literacy services. Like Francophone communities, English speakers in Quebec called for increased research on their realities.

Throughout the consultation, English-speaking participants expressed sympathy for the situation of Francophone minority communities across Canada and the need to do more to support their development. However, they also made a point of expressing their unique situation and their specific concerns, notably with respect to the recognition of their community by the governments of Quebec and Canada. The following paragraphs outline these concerns.

Main concerns specific to Quebec’s English-speaking community

Legal asymmetry in official languages

While supporting the Government’s intention to do more to promote the French language across the country, representatives of English-speaking organizations expressed deep concerns about what they perceive to be a lack of symmetry in the approaches to the two minority language communities in Bill C-13. They see it as setting a legal precedent with long-term consequences that are hard to gauge. For some organizations, the official languages reform does not do justice to the community, and the Government has an obligation to ensure substantive equality in the way it treats official language minority communities. The English-speaking community also asked for official recognition of its status as a minority community in Canada. Half of the respondents to the online questionnaire (51%) identified Government recognition of the community’s language rights as one of the community’s main challenges (77% outside the metropolitan area), ahead of access to quality health services in English (31% in Quebec, 48% outside the metropolitan area). The community called on the federal government to consult it more closely on all aspects pertaining to official languages. There were also calls for the Government to help bring to light that English-speaking and French-speaking minority communities face similar realities and have similar grievances, regardless of the language they speak.

The importance of economic development

Like Francophone communities, Quebec’s English-speaking community asked the Government to consider the importance of community economic development as a means of strengthening communities and ensuring their full participation in Quebec society. This is particularly pressing, as this community has a higher unemployment and poverty rate than the province’s French-speaking population, especially outside the Montreal area. With this in mind, the Quebec Community Groups Network (QCGN) and other community organizations called on the federal government to directly support French language training for English speakers in Quebec as a way to increase their employability.

Youth and leadership

Issues affecting youth are of concern to community organizations. There are concerns about keeping young people in the communities and about their participation in the labour market. There were calls for support initiatives in this respect. There is a desire to develop young people’s sense of belonging to the community. One organization, Youth for Youth (Y4Y), is working to promote civic engagement among English-speaking youth, and the QCGN proposed creating a Leadership Institute to mobilize and train the next generation of community leaders. Such an institute would support the community’s capacity to develop policies and be involved long term in discussions on issues affecting the community.

Diversity and inclusion

As in other official languages communities, members of equity groups such as racialized, immigrant, Indigenous or LGBTQ+ communities are often in a dual minority situation, in terms of both language and identity. However, according to stakeholders, in Quebec, these communities’ English-speaking members and organizations rarely identify with the English-speaking community, thus depriving themselves of additional support networks. Therefore, calls were made for the Government to support engagement within these communities so that the English-speaking community reflects the full range of needs and challenges in Quebec’s English-speaking population.

Culture and heritage

Lastly, in their written submissions, the English Language Arts Network (ELAN), the Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network (QAHN) and the Quebec English-language Production Council (QEPC) called for special attention to the community’s cultural and heritage institutions. They pointed out that the majority of these institutions, especially outside Montreal, are struggling to survive, often after being around for centuries. In particular, they requested that federal cultural institutions enter into a multiparty agreement on culture with the English-speaking community, as they do with French-speaking communities. They also proposed that the Canada Media Fund set aside an envelope for productions by Quebec’s English-speaking community.

3.2 Second-language learning and promotion

Background

More than ever, Canadians have a positive view of bilingualism. This is particularly true of young people, who see bilingualism as a gateway to the world. In Canada, English-speaking parents are enrolling their children in immersion classes in record numbers, and people of all backgrounds and ages are calling for more opportunities to learn French. This reflects the desire of Canadians to master both of Canada’s official languages, which are among the most widely spoken languages in the world.

The Government of Canada values bilingualism and devotes significant financial resources to establishing partnerships with provincial and territorial governments to promote the learning of official languages as second languages. The Government is therefore working to ensure that 2.5 million young people learn their second official language in primary and secondary schools across the country, including over 487,000 in French immersion programs outside Quebec. The popularity of French immersion continues to grow, with enrolment increasing by nearly 75% since 2002. For years, more than 80% of Canadians have said they are committed to bilingualism.

Despite this support for our official languages, the bilingualism rate of Canada’s total population is growing very slowly, reaching 18% in 2021 according to the most recent census data. Our goal for 2036 is to achieve a bilingualism rate of 20%, largely by raising the bilingualism rate among English speakers outside Quebec from 6.8% to 9%.

Having a large number of bilingual people is not only essential to the effective operation of federal institutions, it also contributes to social cohesion in Canadian society. Bilingual people facilitate exchanges and promote understanding between our two major linguistic and cultural groups. They also contribute substantially to the vitality of official language minority community institutions.

The question of how to promote second-language learning figured prominently in the Cross-Canada Consultations. For example, when online respondents were asked to choose five measures to which the government should devote more attention, three concerned the second language. Nearly half (45%) of respondents were in favour of promoting second language learning in early childhood; 37.6% called for more opportunities to learn, practise and thrive in the second official language; and one-third (33%) requested concrete measures to increase Canada’s bilingualism rate. There is no doubt that this interest can be attributed to the belief of 70% of respondents that learning both official languages contributes to a better understanding among Canadians or strengthens Canadian unity (49%).

Bill C-13 amends the Official Languages Act to include, in its preamble, recognition of the importance of providing every person in Canada with the opportunity to learn the second official language and of the contribution of bilingual people to building a mutual appreciation between the two major linguistic communities. The new Act will strengthen the Department of Canadian Heritage’s mandate in this respect.

The measures on second-language learning that the next Action Plan 2023-2028 should contain were discussed in a virtual thematic session and at several of the regional round tables held between May and August. The following are the main recommendations received.

Main courses of action recommended

Foster the recruitment and retention of second-language educators

Stakeholders all over the country raised the issue of recruiting and retaining second-language educators, particularly those teaching French, as a significant challenge to program delivery. This challenge is most acute in rural, northern and other remote locations. Investments are required to attract and retain qualified teachers. In its written submission, the Canadian Association of Second Language Teachers (CASLT) proposed encouraging more post-secondary institutions to offer the second-language teaching diploma and providing sizeable bursaries for post-secondary students entering the field. The University of Ottawa’s Official Languages and Bilingualism Institute (OLBI) suggested creating an immersion certificate program for teachers as a way to promote the profession. The CASLT and other stakeholders recommended supporting teacher retention by providing financial support for ongoing professional development to maintain language skills and supporting teachers in the classroom with assistants or mentors. Several stakeholders also suggested promoting and leveraging immigration from French-speaking countries as a potential source of French-language educators.

Expand and improve the availability and accessibility of French immersion programs across the country

Several stakeholders reported barriers and restrictions to accessing second-language programs, particularly French immersion. They lamented that some school boards limit the number of available spaces or deny access to students who have learning disabilities or who may require additional accommodations. In several provinces, immersion programs are even being eliminated altogether, particularly in rural areas where transportation is an additional challenge for school boards. In Saskatchewan, some boards have reportedly abandoned French as a second language in favour of Indigenous languages, saying they cannot support both. Demand for immersion is strong everywhere, but long waiting lists are discouraging many parents. Therefore, stakeholders suggested that the Government of Canada establish, through policies or Bill C-13, a right to second-language learning, and that federal-provincial agreements contain clear targets for access to immersion.

Expand support for second-language learning to the entire educational continuum, from early childhood to post-secondary

Some stakeholders suggested taking a holistic approach to second-language learning and the promotion of bilingualism by embracing the entire educational continuum. To better prepare students to enter French immersion programs, for example, it was suggested that increased investments be made to support second-language programs in early childhood centres.

Like the stakeholders who attended the thematic session, the Canadian Association of Immersion Teachers, the CASLT and the OLBI pointed out that second-language instruction does not generally continue after high school and that students who wish to continue their studies face multiple barriers, including a lack of knowledge of the programs offered and a lack of financial support. The OLBI pointed out that many students leave immersion programs in their final years of high school because they want to focus on content courses for university admission. A summer credit program was proposed as an incentive for these students to pursue university studies in their second language.

Francophone minority communities see these immersion graduates as attractive potential clients to support the growth of their post-secondary institutions. According to stakeholders, immersion students need guidance and advice to ensure that they continue their education in French. It was also proposed that bursary opportunities be increased to support the pursuit of post-secondary education in French for bilingual English-speaking students.

Support opportunities to learn outside the classroom

Stakeholders, particularly those in Francophone communities, noted that core French programs do not lead to real proficiency in French. Therefore, it is important to maximize opportunities for second-language learning outside the school system. In particular, it was stated that the arts and culture play an important role in second-language learning and that cultural institutions in the communities can play an essential role in building connections with the linguistic majority. One suggestion was to increase language exchange opportunities for youth through national programs such as Young Canada Works, Odyssey, Explore and Vice-Versa, or through similar local programs. These non-formal learning opportunities have a powerful effect in addressing linguistic insecurity and increasing students’ comfort in speaking and using their second language. In addition, Quebec’s English-speaking minority expressed a need for specific support to enable French second-language learning as a means of increasing the employability of adults in the province.

Increase intergovernmental co-operation

Some stakeholders expressed the view that the current federal-provincial agreements on education do not fully support the common vision of a bilingual Canada. Stakeholders indicated a need for increased intergovernmental co-operation to tackle the challenges of educator recruitment and retention, and awareness of the value of bilingualism. It was suggested that governments set specific targets for the growth of second-language instruction.

Recognize “bilingual identity.”

Lastly, the concept of bilingual identity was discussed in the thematic session. Stakeholders indicated that, unlike Francophone identity, bilingual identity enjoys no recognition. However, the enthusiasm shown by many English-speaking parents for whom French language learning is central to Canadian identity should be recognized and encouraged. Stakeholders indicated that the next Action Plan 2023-2028 should help cultivate a bilingual identity and encourage broader policy frameworks for guaranteeing second-language instruction.

3.3 Appreciation and bridge building between English and French speakers

Background

English and French are the common threads that bind social dialogue and national conversations among Canadians. In fact, 98% of Canadians speak English and/or French. In terms of perceptions, 78% of Canadians believe that having two official languages is one of the realities defining Canada and its collective identity. Yet, all too often, English and French speakers know little about one another, and there are few places where they can come together. Only 43% of Canadians are interested in consuming cultural products in the other official language: 79% of French-speaking Canadians want to consume English-language cultural products, whereas only 34% of English speakers say they are inclined to consume French-language cultural products.