Economic profile of the Canadian book publishing industry: Technological, legislative and market changes in Canada’s English-language book industry, 2008–2020

Turner-Riggs

March 2021

The views expressed in this document are solely those of Turner-Riggs and do not necessarily represent the views of the Canadian Heritage or any other person or agency.

On this page

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Introduction

- Change in context

- The most significant changes in the Canadian book market

- 1. The changing retail landscape

- 2. Technology effects

- 3. The 2012 Copyright Modernization Act

- Closing

List of figures

- Figure 1: The North American supply chain

- Figure 2: Distribution of CBF publishers by revenue, 2013/14 to 2017/18

- Figure 3: Total net revenues reported by English-language CBF recipients, 2008/09, 2012/13, 2016/17, and 2019/20

- Figure 4: Aggregate profit margin percentage reported by English-language CBF recipients, 2008/09, 2012/13, 2016/17, and 2019/20

- Figure 5: Total government assistance provided to English-language CBF recipients, 2008/09, 2012/13, 2016/17, and 2019/20

- Figure 6: Distribution of domestic book sales, excluding educational texts, in Canada, 2006

- Figure 7: The proportion of shoppers reporting that they bought books online as opposed to in-person, 2015–2020

List of tables

- Table 1: Canadian book publishers’ sales, online and offline, 2014, 2016, and 2018

- Table 2: Selected indicators for Coach House Books, 2008–2020

- Table 3: Selected indicators for Playwrights Canada Press, 2008–2020

- Table 4: Selected indicators for Fernwood Publishing, 2008–2020

- Table 5: Selected indicators for Orca Books, 2008–2020

- Table 6: Selected indicators for Broadview Press, 2008–2020

- Table 7: Selected indicators for Portage & Main Press, 2008–2020

Alternate format

Economic profile of the Canadian book publishing industry: Technological, legislative and market changes in Canada’s English-language book industry, 2008–2020 [PDF version - 1.16 MB]

Introduction

"The Canadian industry is more precarious than it was ten years ago. The demands on publishers are greater but resources are not keeping pace."

Two facts are important to keep in mind when discussing the structure of the book market in Canada. First, there are numerous types of participants and stakeholders in the industry and the marketplace looks different for each kind. A large, well-capitalized publisher, for example, may see a different set of opportunities and challenges than would a smaller independent press.

Second, there are notable gaps in the available data about Canada’s English-language book market. The market is complex, not all material data is publicly available, and reporting structures and methods have changed over the past two decades. This means in practice that there isn’t as complete or consistent a statistical picture of the marketplace as would be ideal; therefore, comparisons over time often require some interpretation.

Both of those factors figure in this paper, the purpose of which is to consider the most significant changes influencing the English-language book market in Canada from 2008 to the present day. The study relies in part on interviews with, and additional background supplied by, six independent Canadian publishers. Each of the presses noted below will be profiled in the context of key issues identified throughout this report, and each offers a distinct perspective on the Canadian market.

- Broadview Press

Broadview publishes for the higher education market with offices in Ontario, BC, Alberta, and Nova Scotia. - Coach House Books

A literary press based in Toronto. - Fernwood Publishing

Fernwood publishes for the post-secondary and general trade markets is based in Nova Scotia. - Orca Books

A children’s and young adult publisher based in Victoria, with a heavy emphasis on K-12 and library sales. - Playwrights Canada Press

A drama publisher based in Toronto with strong ties to theatre programs in post-secondary institutions. - Portage & Main Press

This Winnipeg-based publisher focuses on K-12 classroom resources and, through its High Water Press imprint, on children’s and young adult titles.

Change in context

Measured only by the integration of the Internet into everyday life and the dramatic shifts in the retail sector, the book industry has undergone a period of profound change since the turn of the century. There are therefore any number of trends and developments that we could explore for our period of interest from 2008 on, each of which has had an impact in terms of shaping the market today.

Before zeroing in on the most significant changes for Canadian-owned presses, however, we should first set out key elements of context that shape the Canadian industry.

The rewards of scale

The past two decades have seen a trend toward a growing consolidation of market share across the industry, both in terms of the proportion of sales accounted for by major retailers as well as by the largest publishing houses. In 2013, for example, two of the largest English-language multinational publishing houses – Penguin and Random House – merged, a move that shrunk the so-called “Big Six” publishing houses in the United States to the “Big Five.” That momentum continues today with the proposed sale (first announced in November 2020) of Simon & Schuster (S&S) to Bertelsmann, the parent company of Penguin Random House (PRH).

“It is impossible to imagine how a combined S&S/PRH will have a positive effect on the Canadian book business or benefit Canadian readers,” Association of Canadian Publishers Executive Director Kate Edwards has said of the pending sale. “Canadian authors will have fewer houses to present their manuscripts to, jobs will inevitably be lost as operations are combined, and S&S/PRH will have greater ability to demand even better terms of trade with retailers and suppliers. A culture of ‘blockbuster’ publishing will become more entrenched. All of this will increase pressure on independent presses who already struggle to compete in a concentrated market dominated by large global companies.”

However, this pattern of scale-via-acquisition can itself be seen as a response to the concentration of market share (and market power) in the hands of a small number of large booksellers, and of the dominant share of Amazon in particular. The cultural marketplace has defining structural characteristics that favour larger competitors and actively encourage market concentration.

Our understanding of the economics of cultural industries owes much to the work of Richard Cave, author of Creative Industries, and Peter Grant in his co-authored book, Blockbusters and Trade Wars. These works identify a number of distinguishing characteristics of cultural products, and Grant offers three observations that reflect what The Economist has referred to as the “curious economics” of the cultural marketplace.

“Most products fail to achieve commercial success, and it is virtually impossible to predict ahead of time which products those will be. This makes the cultural business exceptionally risky. That risk is further heightened by the brief opportunity that cultural products have to prove themselves….The second observation, however, is the converse of the first. If they are successful, cultural products can produce a much higher reward than any ordinary commodities can. Once the cost of the first or master copy has been recovered, the marginal costs of selling additional copies are tiny…the revenue from sales of additional copies in additional markets is profit.

A third observation is also worth noting at this point: cultural products that are attractive to consumers in a large geographical market have a lower risk and a much greater potential reward than do those that are produced for a smaller market. The reason is that with the larger market, there are a greater number of potential customers over which to amortize the fixed costs of the master copy, after which the product can go into profit.Footnote 1”

As Grant’s observations illustrate, cultural industries are characterized by sharply increasing returns to scale. These economies of scale are more available to – and represent a formidable source of competitive advantage for – larger firms in the cultural marketplace. Those larger players can translate that advantage into market power that they wield in their respective supply chains. Or, as one Canadian book industry veteran once put it more succinctly, “Big likes to play with big.”

The North American supply chain

This bias toward scale is evident in the growing integration of the Canadian and American book supply chains. Book distribution in Canada’ English-language market has historically been based in the Greater Toronto Area. But over the past 20 years, there has been much more integration of US and Canadian distribution networks – driven again by a pursuit of greater economies of scale.

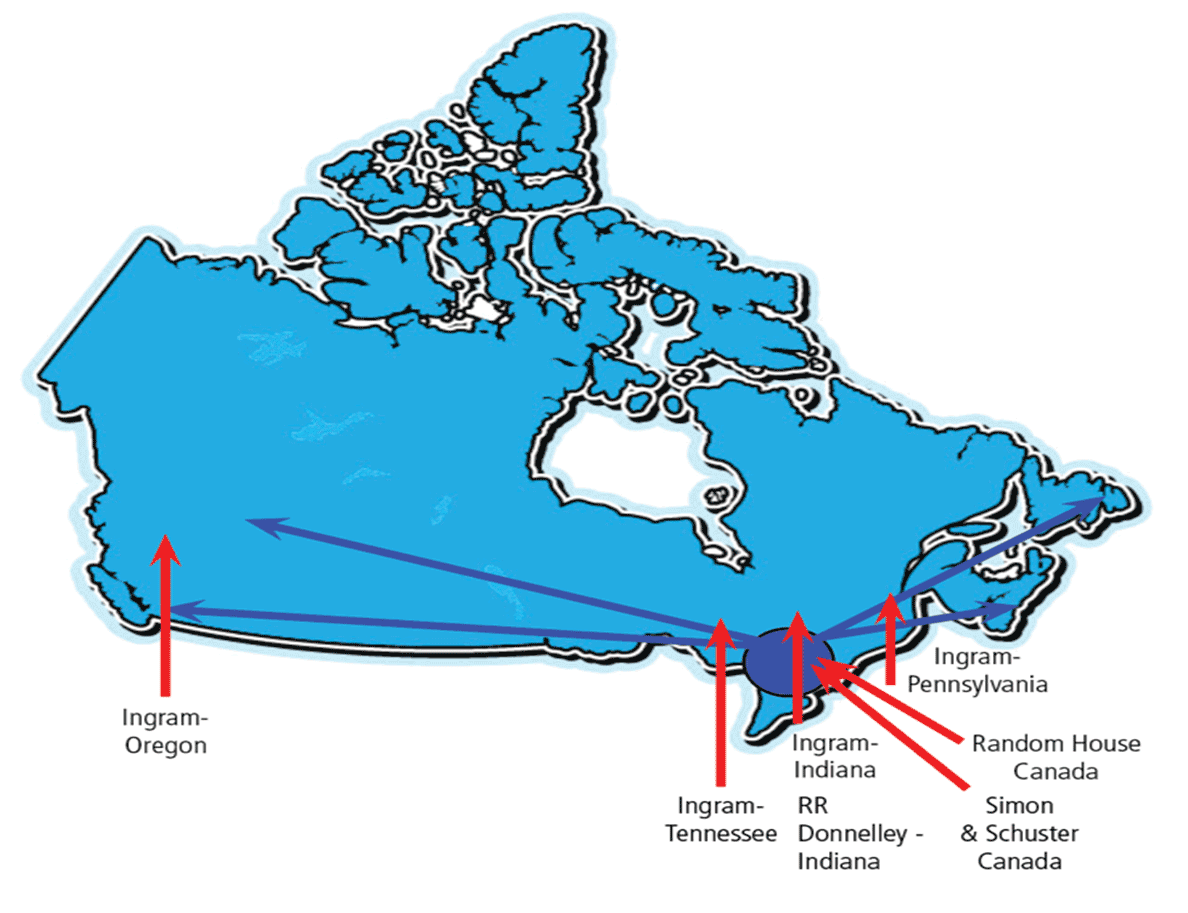

Some aspects of this greater integration can be seen in the internal fulfillment protocols of large retailers, such as Amazon, that may draw stock from consolidated systems spanning US or Canadian distribution centres to fill orders in Canada. But, as the following graphic shows, there are two other significant factors at work as well.

Figure 1: The North American supply chain – text version

A map of Canada representing the North American book supply chain. The red arrows show four non-centralized supply routes from the United States into Canada that belong to the company Ingram. The blue arrows show the Canada-Canada supply routs that originate from one source in central Canada going through:

- Ingram-Oregon

- Ingram-Tennessee

- Ingram-Indiana RR Donnelley Indiana

- Ingram-Pennsylvania

- Random House Canada

- Simon & Schuster Canada

First, Ingram is another major player in the US marketplace, and one for which there is no counterpart in Canada. Ingram is a national wholesaler that has what is reportedly the largest active inventory of books in the industry as well as a scale of operations that is unmatched in North America. The company provides a variety of distribution and fulfillment services to tens of thousands of customer accounts from a network of four distribution centres in the US. The efficiency of those large distribution hubs is such that they can often fill orders to Canadian accounts, especially those outside of the Toronto area, faster than Canadian distributors.

As a privately held company, Ingram does not report its Canadian sales publicly, but there is every indication that its sales volumes to Canadian accounts have increased significantly over the past decade.

At the same time, there is a large-scale transfer of distribution capacity from Canada to the United States in the form of large multinational firms moving to consolidate distribution capacity between the two markets. More specifically:

- Since the early 2000s, Random House Canada (now Penguin Random House) has shipped stock directly to Canadian accounts from Random’s US distribution centre in Westminster, Maryland. Random House Canada also moved its customer service desk to the Maryland centre in 2003 but continues to operate a warehouse in Mississauga to re-supply key titles and process Canadian returns.

- Similarly, Simon & Schuster Canada closed its Canadian warehouse operations in 2004, moving to a system of consolidated shipments from S&S’s distribution centres in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. These shipments are freight forwarded via Georgetown Terminal Warehouse for onward shipment to Canadian customers.

- Most recently, HarperCollins Canada shuttered its Canadian distribution centre in 2015, and contracted fulfillment of Canadian orders to the Indiana-based distributor R.R. Donnelly.

That consolidation into the US supply chain represents more than just a change in business practice for those large multinational publishers. It has also effectively narrowed the field in terms of distribution options available to independent Canadian publishers as those foreign-owned firms, to varying degrees, also provided contract distribution services for Canadian presses. HarperCollins in particular was a well-regarded distributor for several larger independent Canadian presses before closing its Canadian distribution centre several years ago.

The other side of scale

A 2018 industry profileFootnote 2 identified 245 English-language Canadian-owned publishers operating in Canada at the time with a combined economic impact estimated at nearly $500 million. However, nearly eight in ten (78%) of those publishers were small, privately owned firms with ten or fewer employees and many would have had annual revenues of under a million dollars.

A 2019 program evaluation for the Department of Canadian Heritage’s Canada Book FundFootnote 3 (CBF) made similar observations in terms of industry structure and composition. It reports that 55% of publishers in the program during the years 2013/14 through 2017/18 had five or fewer employees. Another 22.5% of CBF participants had between six and ten employees.

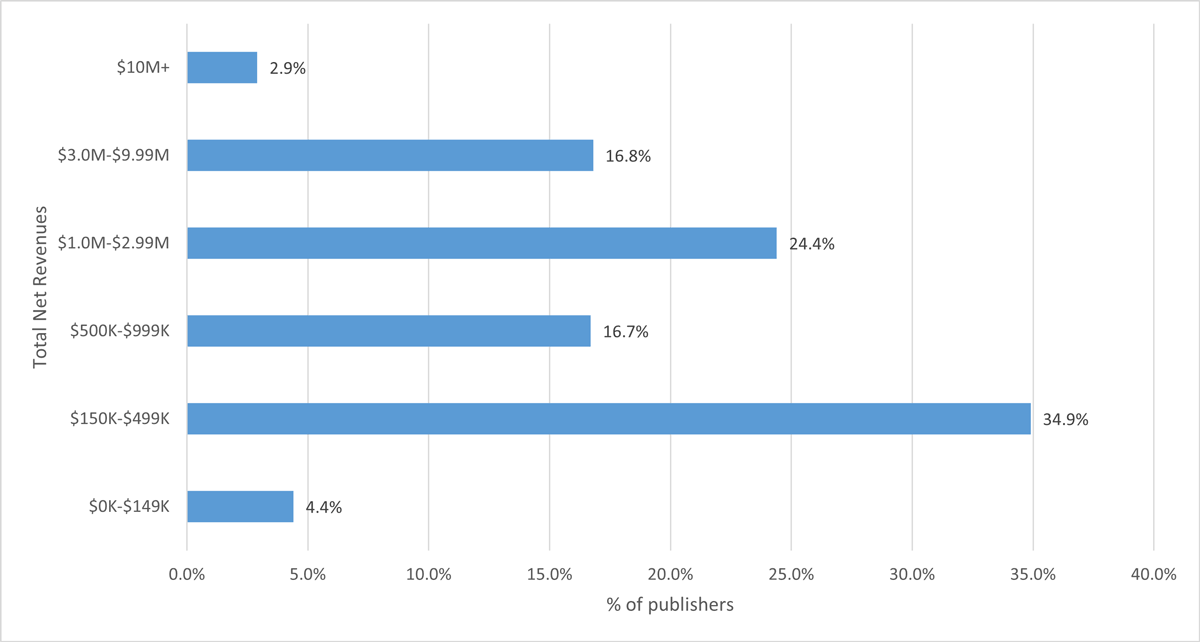

As the following chart illustrates, more than half of CBF recipients during those years (56%) reported annual revenues of under $1 million.

Source: PCH

Figure 2: Distribution of CBF publishers by revenue, 2013/14 to 2017/18 – text version

| Total Net Revenues | % of publishers |

|---|---|

| $0K-$149K | 4.4% |

| $150K-$499K | 34.9% |

| $500K-$999K | 16.7% |

| $1.0M-$2.99M | 24.4% |

| $3.0M-$9.99M | 16.8% |

| $10M+ | 2.9% |

The Canadian book publishing industry consistently demonstrates a high degree of resilience and imagination along with a strong commitment to connecting Canadian authors with Canadian readers. In spite of its considerable cultural successes, however, the industry continues to struggle with limited profitability. Many presses are undercapitalized, with limited access to additional working capital. Therefore, they also face real constraints in their ability to invest in new technologies and/or new markets.

Many Canadian-owned publishing houses operate at or near their borrowing capacity and have limited ability to attract external equity capital. The situation is particularly acute for those firms engaged in literary publishing in categories such as fiction, poetry, drama, and literary non-fiction. While they are highly culturally significant, such publishing programs often struggle with marginal profitability.

This means, in part, that many of these firms do not generate sufficient profits to fund long-term strategic investments. Nor do they generate sufficient working capital from operations to support the increased cash requirements that accompany growth – that is, the additional cash required to fund the increases in accounts receivable, inventory, and taxes that correspond with higher sales.

As much as anything else, this restricted access to capital therefore explains the limited capacity of the industry to fund necessary investments in systems, marketing, technology, and/or editorial acquisitions that would enable a more stable financial position, some economies of scale, and a stronger competitive footing overall.

It also means that those smaller firms remain vulnerable to the market pressures exerted by larger players. In particular, it means that already constrained profit margins are placed under further pressure. Book prices, for example, are highly inelastic and most firms (regardless of size) have limited room to maneuver around established pricing conventions for a given format or category. This arises in part from the massive (and quickly growing) inventory of titles in the marketplace, all competing with each other for shelf space, visibility, and reader attention.

At the same time, there is considerable upward pressure on publisher costs. More limited distribution options, for example, mean that publishers have a weaker negotiating position in establishing terms with distributors. A greater concentration of sales within a relatively small field of large retail accounts leaves smaller firms at a disadvantage when it comes to negotiating terms of trade, including the discount percentages extended to booksellersFootnote 4 as well as marketing or co-op budgets.

Especially within that context of declining margins, every sales channel and source of revenue is of critical importance to independent Canadian publishers, as is every opportunity for greater economies of scale or operating efficiency.

The most significant changes in the Canadian book market

"The majority of our sales used to be to the Canadian market, but that has shifted to the US. It is harder now to make products for the Canadian market – the market is shrinking because people are using free resources."

Based on the publisher interviews conducted for this study as well as the accumulated research in the industry, we can conclude with confidence that the following changes have had the greatest impact on publishers in Canada’s English-language market from 2008 through to the present day.

- The changing retail landscape, especially the erosion of the independent bookstore sector.

- The role of technology, in particular the mainstream adoption of e-books, ready access to cloud-based tools, and the shift in consumer discovery and purchase behaviour to online channels.

- The 2012 Copyright Modernization Act and the continuing uncertainty around the legislation’s fair dealing provisions.

We will explore each of these in detail below. The question that accompanies this review is whether any of these factors has put further pressure on the sustainability or competitive position of independent Canadian publishers. To walk that question back a step, we might ask whether the financial position of Canadian-owned presses has materially changed from 2008 up to the present.

To explore this in more detail, we looked to the Canada Book Fund (CBF) as a stable and consistent source of data on the Canadian-owned sector over the period in question. The CBF program collects information each year on the financial health and financial performance of recipient publishers, and as such represents an important window into overall trends in the Canadian-owned sector.

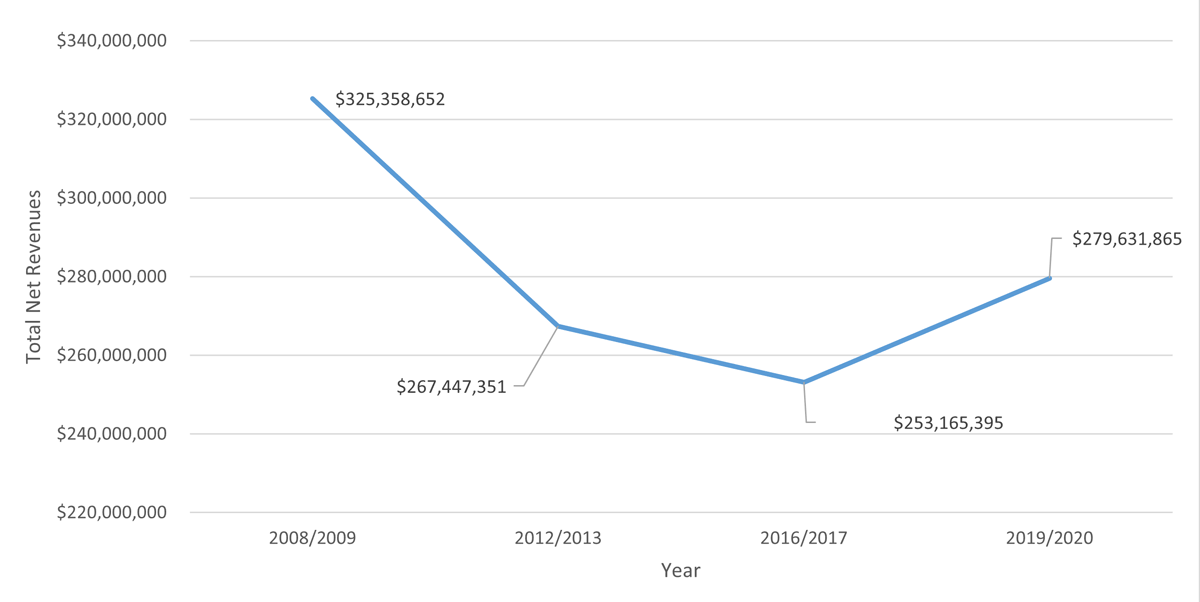

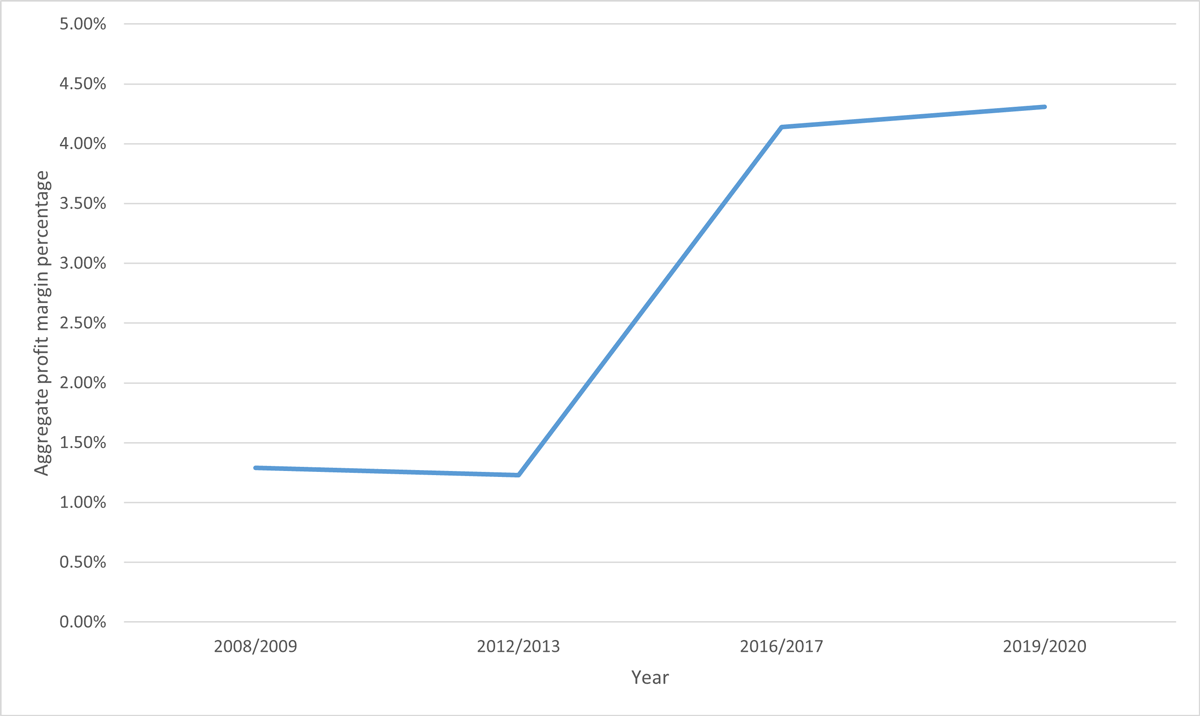

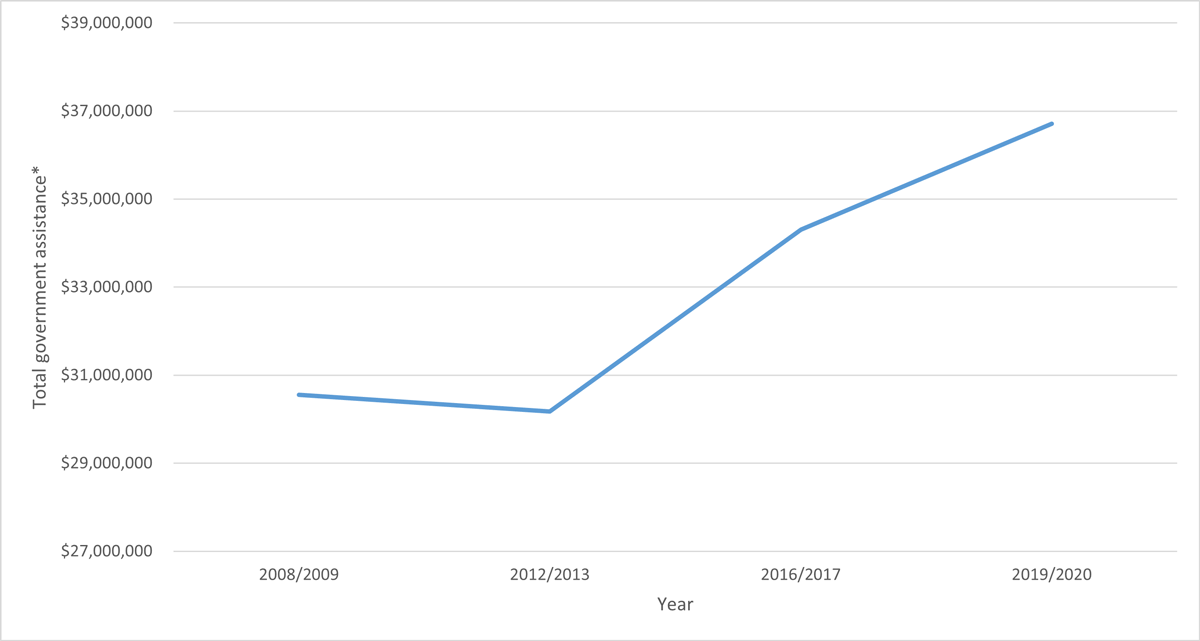

The CBF data provides, for example, aggregate values for total government support provided to firms along with total revenues for the sector and overall profitability. We sampled these values for English-language recipients for the reference years 2008/09, 2012/13, 2016/17, and 2019/20, and the trend lines for each are summarized in the charts below.

Source: PCH

Figure 3: Total net revenues reported by English-language CBF recipients, 2008/09, 2012/13, 2016/17, and 2019/20 – text version

| Year | Total Net Revenues |

|---|---|

| 2008/2009 | $325,358,652 |

| 2012/2013 | $267,447,351 |

| 2016/2017 | $253,165,395 |

| 2019/2020 | $279,631,865 |

Source: PCH

Figure 4: Aggregate profit margin percentage reported by English-language CBF recipients, 2008/09, 2012/13, 2016/17, and 2019/20 – text version

| Year | Aggregate profit margin percentage |

|---|---|

| 2008/2009 | 1.29% |

| 2012/2013 | 1.23% |

| 2016/2017 | 4.14% |

| 2019/2020 | 4.31% |

Source: PCH

Figure 5: Total government assistance provided to English-language CBF recipients, 2008/09, 2012/13, 2016/17, and 2019/20 – text version

| Year | Total government assistance |

|---|---|

| 2008/2009 | $30,556,089 |

| 2012/2013 | $30,178,066 |

| 2016/2017 | $34,303,424 |

| 2019/2020 | $36,707,654 |

There are a few broad observations that could be made of the trends shown in these charts:

- Total revenues reported by English-language CBF recipients dipped sharply through 2012/13 and declined by just more than 14% overall between 2008/09 and 2019/20. This amounts to a drop in sector revenues of nearly $46 million over this period.

- The total government assistance provided to English-language CBF recipients increased by 20% over that same period, or roughly $6 million overall.

- Sector profitability remained marginal throughout, rising from an aggregate profit margin percentage of 1.29% in 2008/09 to 4.31% in 2019/20.

Even with that improvement, overall sector profit levels remain modest and will have been influenced by the increase in government assistance from 2008 on. More to the point, that increase in support will have helped to partially offset the rather significant decline in sector revenues over that period. That improved profitability appears to have contributed to an overall improvement in liquidity on the part of sector publishers. The quick ratio is a commonly used measure of liquidity that relates current assets, excluding inventory, to current liabilities. It can be understood as a standard measure that reflects the firm’s ability to meet its current financial obligations.

The quick ratio for the sector improved from an aggregate value of 0.95 for English-language CBF recipients in 2008/09 to 1.41 for 2019/20. Along with the improved aggregate profitability over the 12 years in question, this increased ratio value also reflects a decrease in inventory holdings over the reference period, from $78,471,758 in 2008/09 to $64,141,236 in 2019/20.

This arises in part from the inventory effect of e-books (that is, a growing proportion of sales accounted for by e-books for which there is no accompanying physical inventory). It also stems from the fact that the entire supply chain has been working to manage inventory investments down since 2008. This is a bid to reduce inventory carrying costs, but it also reflects a pattern of more conservative buying on the part of trade accounts (and correspondingly more conservative print orders on the part of publishers). The overall 18% decrease in inventory values for CBF publishers appears to reflect that broader trend, along with the fact that overall sales volumes declined during our review period.

Similarly, the aggregate equity to debt ratio for sector publishers has improved since 2008. For the 2008/09 fiscal year, that overall ratio was 0.49 but it improved to 0.85 for 2019/20, indicating that Canadian firms were less highly leveraged at the end of this period than they were in the beginning.

The larger picture, then, is of a sector that is showing great resilience in the face of a significant drop in overall revenues. The industry remains marginally profitable, but, by some measures at least, is in a slightly improved financial position in 2019/20 than was the case in 2008/09.

1. The changing retail landscape

Canada’s book retail sector changed forever in 1994. That was the year in which a new national chain, Chapters, bought and merged the two national chains that had operated in English Canada up until that point: Coles and SmithBooks.

That development spelled the end of an era of two competing national chains, which would be replaced, beginning in 1995, with a network of Chapters big box stores and smaller “mall stores.” Chapters was itself subsequently bought out by and merged with its smaller (but well-capitalized) rival Indigo in 2001. The number of large-format and mall stores has changed over the years, but as of March 2020 Indigo reported “88 superstores under the banners Chapters and Indigo and 108 small format stores under the banners Coles, Indigospirit, and The Book Company.Footnote 6” Since that 2001 merger, Indigo has remained the only national bookselling chain in English Canada.

Alongside those major developments, there are a couple of other key trends that we can observe in book retail:

- Although there are signs that it has stabilized in recent years, the market share of independent bookstores has declined from the mid-2000s.

- Non-traditional retail, especially Costco but also other big box and specialty outlets, has continued to claim a larger share of book sales in English Canada.

- Online retail has seen dramatic growth from the mid-2000s through to the present day.

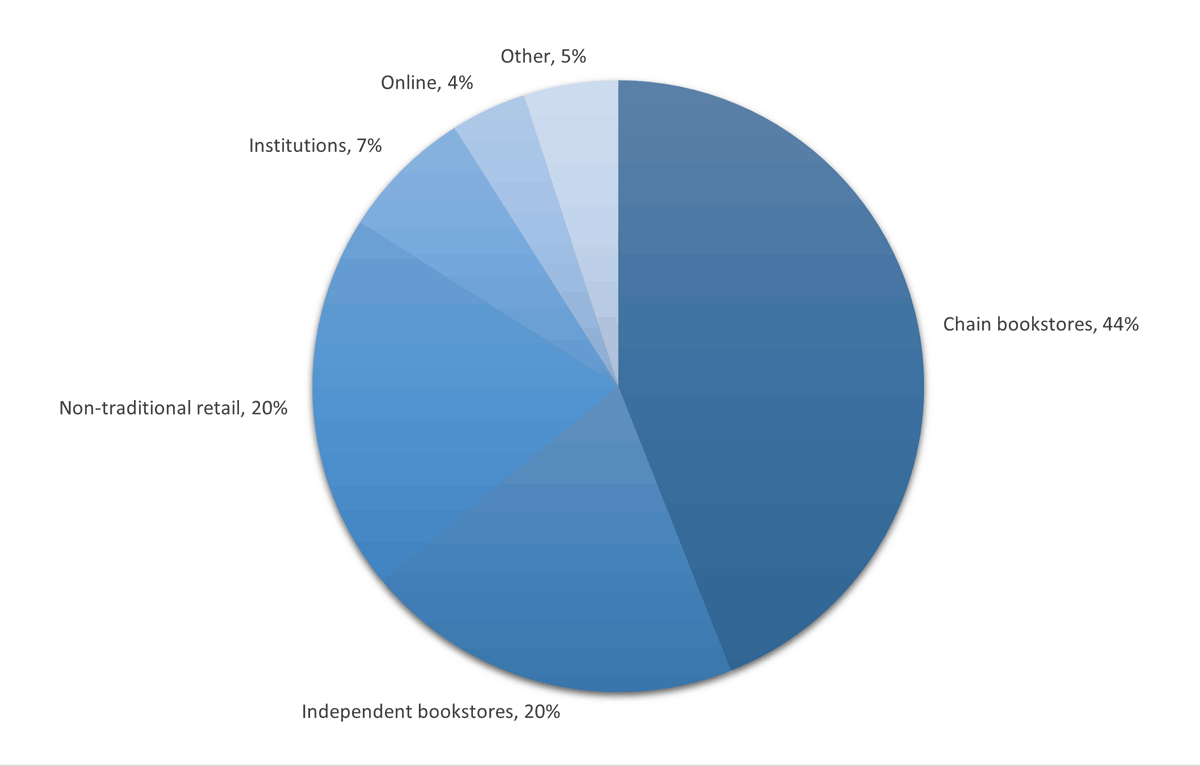

In our 2007 study for Canadian Heritage, The Book Retail Sector in Canada, we estimated the following distribution for Canadian book sales by channel.

Source: Turner-Riggs

Figure 6: Distribution of domestic book sales, excluding educational texts, in Canada, 2006 – text version

| Channel | % of domestic book sales |

|---|---|

| Chain bookstores | 44% |

| Independent bookstores | 20% |

| Non-traditional retail | 20% |

| Institutions | 7% |

| Online | 4% |

| Other | 5% |

But even at that point, there were important changes afoot. If we look at just the sales distributions for English-language CBF recipients, we can see that the share of market for independent bookstores was starting to decline through the mid-2000s, from 13% of publisher sales to 10% by 2012/13. At the same time, CBF recipient sales to non-traditional big box retail (e.g., Costco and others) and online sales had increased from 11% to 22% and 4% to 9% respectively.

Most recently, a discussion paperFootnote 7 from the More Canada steering committee noted that, “Prior to COVID-19, English Canada’s surviving independent bookstores accounted for a combined 7% of retail book sales in 2019, their share dwarfed by Indigo and Amazon, with Costco and Walmart also capturing a significant portion.”

The More Canada paper reinforces a point that has been long understood in the book trade: there is a tremendous affinity between independent bookstores and Canadian-owned publishers, with the former accounting for a proportion of sales of Canadian-authored titles that considerably exceeds the stores’ overall market share. More Canada estimates that independent stores account for roughly 20% of the sales of Canadian-authored books and adds, “For independent Canadian publishers, responsible for three-quarters of all the new books by Canadian authors published annually, independent bookstores are a crucial channel by which their books find readersFootnote 8.”

Just as independent bookstores have been pressured by the emergence of a consolidated national chain, bricks-and-mortar stores of all stripes have also lost some market share to the rapidly growing online channel. The data in this channel is notoriously incomplete, in part because Amazon does not report its Canadian sales in any detail. At the same time, online sales made via bricks-and-mortar retailers – whether Indigo or independent stores – are not often fully differentiated from overall sales volumes.

Even with those caveats in place, it is clear that online sales have surged in Canada, even before the COVID pandemic. Statistics Canada data in this arena is problematic as well in that it does not offer a whole market view; but even within the Statistics Canada sample the signs of significant growth are clear.

The following chart indicates that overall online sales grew by 42% between 2014 and 2018 alone. Also, over that period, the proportion of total publisher sales made via online channels, including e-books, grew from 23% to 33%.

| Electronic sales, dollars (x 1,000,000) | 2014 | 2016 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total sales of own and agency titles | $1,351.8 | $1,324.4 | $1,341.8 |

| Internet sales of print books | $152.1 | $187.1 | $258.9 |

| Sales of e-books | $159.6 | $171.2 | $183.2 |

| Sales of print books (not on internet) | $1,040.1 | $966.1 | $899.7 |

Source: Statistics Canada

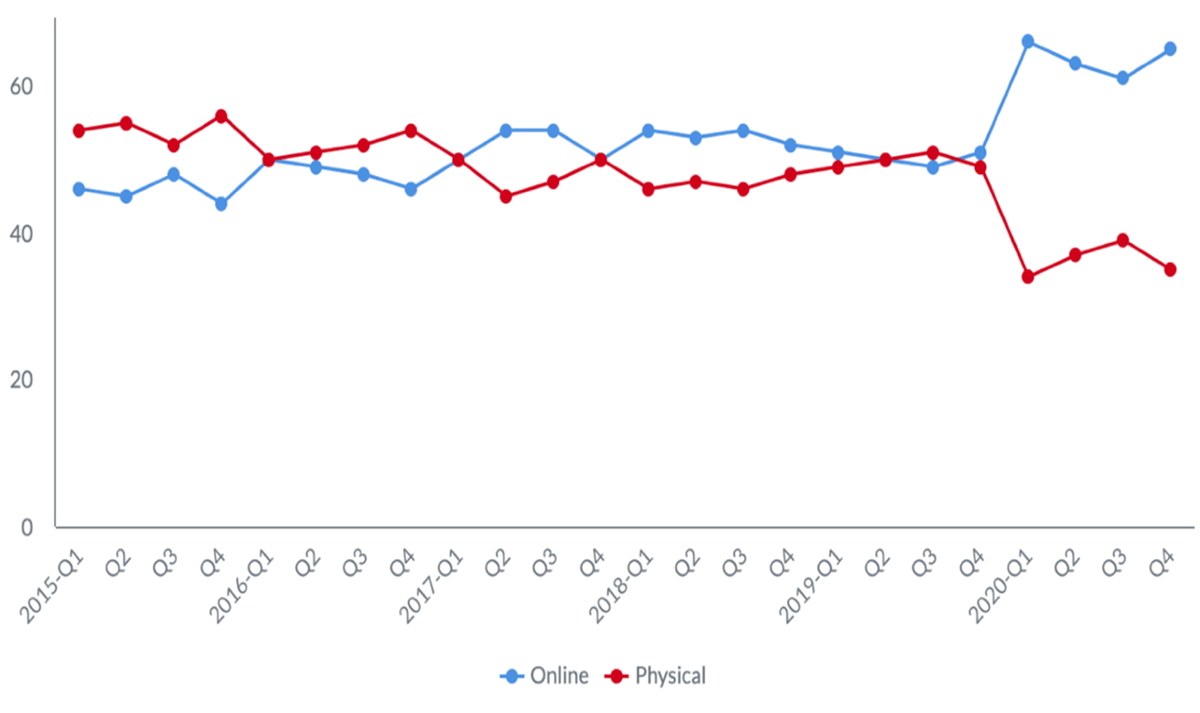

BookNet Canada offers another window on the growing online channel through its annual consumer tracking studies. These ongoing surveys gather data from adult respondents who purchased a book in any format in the previous month.

The following chart shows, strictly within the BookNet sample of book buyers, what proportion of shoppers bought their books either online or in person. Stretching back over the last several years, we see that online sales have been claiming a larger share of sales within the sample, and, as of 2018, began to account for more than half of sales reported by survey respondents.

The chart also shows us that, as has been extensively documented elsewhere, the pandemic has been a major accelerator of that underlying trend through most of 2020.

Source: BookNet Canada

Figure 7: The proportion of shoppers reporting that they bought books online as opposed to in-person, 2015–2020 – text version

The proportion of shoppers reporting that they bought books online as opposed to in person increased between 2015-2020.

In Quarter 1 of 2015, the proportion of shoppers reporting that they bought books online was roughly 10 percent lower than those that reported that they bought physical books.

These numbers fluctuated until Quarter 1 of 2017 when online sales overtook physical sales. The difference between online sales and physical sales fluctuated marginally between Quarter 1 of 2017 and Quarter 2 of 2019.

In Quarter 2 of 2019, online sales dipped slightly below physical sales. However, in Quarter 4, online sales increased exponentially while physical sales decreased exponentially.

In Quarter 4 of 2020, online sales represented almost 30% more sales than physical sales.

This shift to online represents a sea change in terms of how publishers ensure the visibility of their books, how they engage with readers, and how those readers find and select the books they choose to purchase and read.

We will explore this further in the next section of the paper but, for now, suffice to say that the online channel places additional demands on publishers: it requires new tools and processes. While the shift to online presents new opportunities – it is a powerful new platform for promoting backlistFootnote 9 for example, and many publishers are seeing real growth in direct-to-consumer sales via their own websites – there are challenges as well, especially when it comes to driving frontlist sales for independent publishers, an arena where independent stores have always played a critical role. For many smaller publishers in particular, the main issue remains adapting to the different ways that readers encounter and select books online.

Publisher’s perspective - Alana Wilcox

"I've been very frustrated the last year because I don't know how to reach people," says Alana Wilcox, the editorial director of Coach House Books. “Our sales took a real hit last year in Canada. Our books are browsing books and so sales will be down so long as bookstore traffic is down.”

"It's a really different world than it was ten years ago, and I don't totally know how to adjust to it,” she adds. “It used to be a problem that we had no direct access to readers. At the same time talking to your readers is kind of exhausting. If it takes 12 tweets to sell three copies, that’s a lot of labour."

Those comments perfectly reflect the experience and perspective of many publishers who now find themselves working across an expanding range of offline and online sales channels. Even so, Coach House has some real advantages, especially in relation to smaller presses, in meeting those challenges.

Founded in 1965, Coach House is one of the longest established and most highly regarded literary presses in English Canada, and it is one of few publishers in Canada that prints nearly all of its own books (through Coach House Printing). With a focus on fiction, poetry, film and drama, and select non-fiction (including a series of books about Toronto), the press boasts an impressive backlist and had a tremendous commercial success in 2015 with Andre Alexis’ runaway bestseller Fifteen Dogs. “The life of Coach House has been changed so much by Fifteen Dogs,” says Wilcox.

Thinking back over the period to 2008, Wilcox zeroes in on “cultural homogenization” as the biggest change she has observed. “Everybody is reading the same books, and shopping at [big box bookstores], and there is less support for small press titles within big retail.”

This translates, she explains, into a reduced selection of books available in bookstores – helped along in part by the declining market share of independent booksellers – and a hollowing out of what is often referred to as midlist titles (books that find an audience and sell steadily without reaching bestseller status). “Now you have books that sell 400 copies, and books that sell 400,000 copies, and not much in between,” she adds.

Looking at some of the top-line indicators for Coach House in the table below, we can see a distinct shift after the publication of Fifteen Dogs in 2015, and a vivid illustration of some of the “curious economics” of cultural industries that we explored earlier. Thanks in part to the tremendous success of that one book, amplified over time by continuing rights sales and by the author’s more recent works, the selected indicators for the press are stronger at the end of our review period than was the case in 2008.

| 2008 | 2012 | 2016 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title Output | 14 | 13 | 14 | 18 |

| Staff | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5Footnote 10 |

| RevenueFootnote 11 | 100 | 106 | 214 | 187 |

Source: Coach House

2. Technology effects

What parts of our lives have not been touched by technology over the past 12 years? The effects of technological change have been just as far-reaching within the book industry, but we will focus on a few key impacts in this section.

First, the mainstream adoption of e-books and the steady increase in e-book sales volumes over the past decade. Overall sales volumes have not risen to the heights of some of the more enthusiastic early projections, and there is no question that some types of books and some publishers see much more traction in terms of e-books sales than others. But it is equally clear that digital books have become a very important format for Canadian publishers and one that is here to stay.

Second, the lowering of barriers to entry for online tools, services, and systems that allow publishers to work more efficiently, to collaborate more widely, and to pursue new opportunities in Canada and abroad.

Finally, the fundamental shift of consumer and buying behaviour from in-person interactions (and in-store shopping) to online.

E-books

It is funny to think back to this now, but the idea of mainstream adoption of digital books was still under some level of debate in 2008. The years since have seen a dramatic expansion of e-book sales – fuelled in part by the emergence of major retail and reading platforms such as Amazon Kindle, Kobo, and Apple Books – and an ever-growing catalogue of Canadian-authored work.

In the 2019 edition of its The State of Publishing in Canada reportFootnote 12, BookNet Canada noted that roughly half of Canadian publishers had dedicated staff working on e-books as of that year. Nearly all publishers (91%) were actively producing e-books, and 55% had produced digital editions for most or all of their backlists by that time.

It has now also become commonplace for publishers to release new titles simultaneously in both print and digital editions (71% of publishers responding for the BookNet study reported doing so). Most recently, there has been a greater emphasis on accessibility standards and features to better address the needs of print-disabled readers in Canadian e-book production.

Most publishers produce e-books to allow them to reach new readers (83% according to BookNet) or increase sales (78%). About two-thirds of presses (62%) responding to the (pre-pandemic) survey said they thought their e-book sales would increase further in the year ahead.

The Statistics Canada data we looked at earlier would suggest that e-books accounted for about 14% of publishers’ sales in 2018. The overall volume of e-books sold continues to increase year-over-year, but the distribution of those sales is uneven with more commercial titles, along with genre fiction, accounting for large proportion of sales. Even with those aggregate increases in sales volumes over time, the place of e-books within the sales mix of independent Canadian publishers still varies substantially from press to press.

Publisher’s perspective - Annie Gibson

“E-books have been an absolute dream for the press,” says Playwrights Canada Press Publisher Annie Gibson. “Sales are growing every year but have not been cannibalizing our print sales and we offer higher royalties on digital editions to playwrights.”

“Our digital sales have been growing steadily over the past several years,” she adds. “E-books accounted for 11% of total sales in 2019 but we saw that jump up to 25% of sales in 2020 [during the pandemic]. We are now putting an even greater focus on digital with additional backlist conversions and upgrading our existing e-books for better performance and accessibility.”

Playwrights is a great example of a niche publisher that is well suited for the e-book market. A large proportion of the press’s sales are made via theatre programs in universities, colleges, and high schools that have adopted Playwrights titles (individually or in course bundles) for teaching and performance. Needless to say, those institutions are full of “digital natives” who live busy online lives and who are at ease with digital content of all sorts.

The press was founded in 1984 as an imprint of the Playwrights Guild of Canada, the national association of professional playwrights. In August of 2001 the press was separately and legally incorporated from the Guild with its own board of directors and now publishes roughly 25 books per year, the majority of which are new Canadian plays.

Playwrights is the only publishing house in the country to focus solely on drama. In addition to plays, the press publishes occasional biographies and books of Canadian theatre history and criticism. The Playwrights team is committed to supporting diverse playwrights from across Canada, including Black writers, writers of colour, Indigenous writers, women writers, 2SLGBTQIA+ writers, writers from underrepresented regions, writers in translation, and both established and emerging playwrights. In fact, Gibson sees an even greater emphasis on diverse voices on the horizon. “We are really pushing for more diversity in terms of our editorial process and in terms of what we publish,” she says. “It's possible we will produce fewer books in order to invest more heavily in the works we do publish.”

Books by Playwrights Canada Press are frequently finalists for Lambda Literary Awards and provincial playwriting prizes, and have won the Trillium Book Award, the Patrick O’Neill Award, and the Governor General’s Literary Award in both the drama and translation categories.

“Our sales have been really stable,” says Gibson, and that stability shows through loud and clear in the following summary of selected indicators for the press. While the press has not grown substantially over that period, its output and financial performance have been quite consistent during a period of significant change.

| 2008 | 2012 | 2016 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title Output | 33 | 22 | 27 | 17 |

| Staff | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| RevenueFootnote 13 | 100 | 102 | 88 | 108 |

Source: Playwrights

Digital tools

Along with e-books and online bookstores have come a whole host of digital applications and services that are increasingly affordable and accessible to Canadian publishers. Many of these factor in our day-to-day lives outside of work, including social media, cloud-based file sharing and collaboration tools, video and online conferencing, and chat or messaging apps.

Most of those tools are affordable, or even free, and their mainstream adoption and ease of use has put them in reach for every publishing house. This means that publishers, staff, and contractors can work remotely if need be, or that an extended network of staff and authors or other stakeholders can collaborate easily over distance and time. As one experienced technologist put it to us recently, “We’ve solved all of the messy stuff – standards, how things are built, how interfaces work – now we can just get on to doing stuff [with digital tools].”

We saw a vivid illustration of this last year when one major international trade event after another was cancelled due to COVID-19. Losing the opportunity to attend the London Book Fair or Frankfurt in person was a serious challenge for many Canadian publishers. But it was fascinating to watch people adapt in real time and, regardless of virtual events mounted in place of some of those major international industry events, Canadian publishers took to their mobile devices, emails, and Zoom accounts and scheduled meetings with their foreign colleagues on their own.

This pattern is playing out again this year as the pandemic lingers and as major events, most recently the London Book Fair, are again being postponed, cancelled, or transitioned to virtual. Many experienced rights staff within Canadian publishing houses have already conducted one-to-one Skype or Zoom calls with colleagues they would have otherwise met in London this spring.

It is interesting to note in this context that aggregate marketing expenditures for CBF recipient publishers have been declining over our reference period, from $33.3 million in 2008/09 to $26.5 million in 2019/20. Part of this is a move to control costs as revenues have declined, but it reflects as well a growing reliance on online marketing efforts via social media, email, or other low-or-no-cost digital channels.

Publisher’s perspective - Errol Sharpe

“Technology has made it possible to do a lot more things than you could before with a lot less people which in turn has been a very big contributing factor to our growth over the last 15 years,” says Fernwood Publishing Publisher Errol Sharpe. “Thinking about digital production in particular, we are now doing 30–40 books a year. Twenty to 25 years ago that would have been unimaginable, at least not without a lot more people.”

As that comment suggests, Sharpe has seen major technology-driven gains for his press, especially in the areas of book production, but in also the promotion of international rights sales and more efficient communications with authors and others. “[Technological change] has also given us a lot more options for how we publish,” he explains. “For example, we might decide to publish a book with a smaller page count and with larger appendices provided online.”

Marketing has changed as well and is also now much more driven by technology. “We have much better ability to communicate with people and get information about our books out there via email and social media, for example. I’ve spent much of my life as a salesperson and would routinely travel back and forth across the country two or three times a year. Traditionally, marketing was a much more hands-on thing but now we spend more time and effort on those digital channels.”

Even so, Fernwood is always trying to find the right balance between that personal touch and the use of technology. “Publishing is built on ideas and sharing of ideas,” adds Sharpe. “It's a process of thinking through ideas, and a lot of technology just doesn't give you that.”

Fernwood’s publishing program has always been heavily weighted to the post-secondary education market, but that balance has shifted in recent years due to changes arising from the 2012 copyright legislation (more on that in our next section). Today, the sales base for the press is more balanced with about half of overall sales made in higher education and the other half representing an expanded focus on trade channels.

However, Fernwood remains a press with a very clear perspective:

“We are political publishers in that our books acknowledge, confront and contest intersecting forms of oppression and exploitation. We believe that in publishing books that challenge the status quo and imagine new ways forward we participate in the creation of a more socially just world…As an independent Canadian publisher, we also emphasize, though not exclusively, Canadian authors and the Canadian context. The quality of the books we publish and the relationships with our authors demonstrate that every member of our small team is dedicated to the publishing and political goals of social justice.”

That expansion of Fernwood’s trade program is reflected in a pattern of steady growth over our reference period as reflected in the table below.

| 2008 | 2012 | 2016 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title Output | 29 | 31 | 37 | 39 |

| Staff | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 |

| RevenueFootnote 14 | 100 | 135 | 138 | 154 |

Source: Fernwood

The consumer shift to online

Even with all of these key developments in the e-book market and the ready access to digital tools and services, it could be argued that the most important technological change in the industry has been the great extent to which the discovery and purchase of books has moved online.

The tipping point for this in the Canadian market appears to have been some time in late 2016 or early 2017. It was around that time that tracking studies began to show that reader awareness of books – that is, the means by which readers discover and select new books – was equally split between offline and online channels. In other words, a full 50% of all book discovery now happens online, through an online bookseller, social, messaging, or email channels, or other community sites.

Further, more than four in ten (42%) of all book recommendations received by readers are now transmitted via online sources. Given the critical role that word-of-mouth and personal recommendations play in influencing purchasing behaviour, this is a powerful indicator of the extent to which the conversation among readers about books has now transitioned to the web.

It is not surprising, therefore, that buyer behaviour has shifted as well. Roughly half of all consumer book purchases in BookNet tracking studies are now made online (before the pandemic, that is). This speaks not only to the increasing prominence of the web as a sales channel, but also to consumer expectations about pricing, service standards, stock availability, and user experience when buying books on the web.

There are a number of implications in this for Canadian publishers, not least of which are:

- The need to produce and share rich bibliographic informationFootnote 15 for their books. The research in this area is clear and there are significant sales impacts arising from the use of extended title information online, including excerpts, reviews, awards information, and more.

- The need to adapt to new buying behaviours online, including acknowledgement that discovery (i.e., finding out about a title of interest) and purchase behaviours are often “decoupled” in the online space; readers often find out about books in one part of the Internet and buy them in another. This is in sharp contrast to bricks-and-mortar stores, where readers often discover and immediately buy books during their in-store experience.

- The need for better data and analytics, especially around book purchasing and user/reader behaviour.

- The need to make published work as widely available online and in as many forms and formats as possible so that the reader can select the option that is best for them.

None of this adds up to just an additional task or set of tasks for a publishing team. Rather, this shift to online marks a fundamental change in how books are marketed and sold, and it affects everything from the publisher’s decisions around pricing and format, to the information that publishers share about their books, to the publisher’s relationship with its readers, suppliers, trade accounts, and other key audiences.

John Thompson sums up the situation in his recently released book, Book Wars: The Digital Revolution in Publishing:

“As bookstores began to close and book superstore chains began to scale back or go under, publishers increasingly began to realize that they could no longer count on physical bookstores to do what the intermediaries in the traditional book supply chain had always done: make books visible and available to readers. It became increasingly clear that readers were finding books in new and different ways – less by walking into a bookstore and browsing the tables at the front of the store, more by browsing online or receiving an email with a list of recommended titles or in some other way….E-book sales may have levelled off but e-books were never the essence of the digital revolution in the publishing industry: they were just one manifestation of a much deeper and more profound transformation that was taking place in our societies. Thanks to the digital revolution, the information and communication structures of our world are in flux. People are communicating differently and spending their time differently, old practices that worked well in an earlier era may no longer be so effective in this new world of digitized information and communication flows.”

Publisher’s perspective - Andrew Wooldridge

“We now see ourselves as an e-commerce company,” says Orca Books Publisher Andrew Wooldridge. “And that understanding affects everything we do, from how we prepare our bibliographic data to how we market and sell our books. This is how we access new and bigger markets.”

“Roughly 25% of our revenue comes from digital,” he adds. “Both e-books and digital licensing to schools. But it’s taken us a lot of investment to get there, and a lot of work to open up those online sales channels.”

Founded in 1984, Orca Book Publishers is a leading children’s book publisher in Canada with over 1,000 titles in print. A company statement adds, “Orca publishes everything from beautifully illustrated board books and picture books to middle-grade and young-adult fiction. We strive to produce books that illuminate the experiences of people of all ethnicities, people with disabilities and people who identify as LGBTQ+. Our goal is to provide reading material that represents the diversity of human experience to readers of all ages. Orca aims to help young readers see themselves reflected in the books they read. We are mindful of this in our selection of books and have a particular interest in publishing books that celebrate the lives of Indigenous people. Providing young people with exposure to diversity through reading creates a more compassionate world.”

School and library markets have always been important to Orca and the company has enjoyed good success in those institutional channels in the US. However, Wooldridge points out that there is less sales and marketing infrastructure to help publishers reach libraries and schools in Canada, especially in the form of large-scale wholesalers such as there are in the US. Orca is now confronting this challenge head on by adding staff with a focus on school sales, and by developing new digital license products for use in classrooms.

In spite of Orca’s continued growth, Wooldridge says that the Canadian industry is more precarious than it was ten years ago. “It’s not just copyright, it’s access to resources [for publishers] especially beyond a top tier [of the largest independent presses].”

“The demands on publishers are greater — especially the number of things they have to do to publish and market books — but resources are not keeping pace. Orca owns a building that can be used to secure financing, but many firms don’t have access to capital. There is a real divide in that smaller firms don’t have access to capital and the Canadian market is not going to get any easier, especially on the retail side. We’re lucky that we have our US sales to support our ability to compete in Canada — the last couple of years our Canadian sales are actually declining.”

The importance of the new foreign and institutional markets that Orca is pursuing is made very clear in the following selected indicators, which describe a continuing pattern of growth over our reference period even with challenging trading conditions in the Canadian market.

| 2008 | 2012 | 2016 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title Output | 74 | 78 | 93 | 99 |

| Staff | 18 | 20 | 25 | 31 |

| RevenueFootnote 16 | 100 | 100 | 125 | 175 |

Source: Orca

3. The 2012 Copyright Modernization Act

“Fair dealing for the purpose of research, private study, education, parody or satire does not infringe copyright.”

Canada’s updated copyright legislation received Royal Assent in June 2012Footnote 17, and opened the door to considerable disruption and uncertainty in Canadian publishing and education. The Act included a provision, quoted above, that enshrined educational use within the fair dealing provisions of the legislation. However, the Act did not define educational use in this context, and that ambiguity remains today.

Prompted by the new legislation, the Council of Ministers of Education, Universities Canada, and Colleges and Institutes Canada established and adopted a set of Fair Dealing GuidelinesFootnote 18 in 2012. This meant that the usage guidelines were effectively adopted by all K-12 schools and post-secondary institutions in the country, outside of Quebec. A key provision in the guidelines is that educators may “communicate and reproduce” short excerpts of copyrighted works for educational purposes, where a “short excerpt” is defined as up to 10% of a book, or one chapter.

The implementation of the guidelines marked the end of a system of licensing fees that had to that point been paid since 1991 by ministries of education and post-secondary institutions to Access Copyright, a copyright collective acting on behalf of authors and publishers. Effective January 2013, all public K-12 schools stopped paying licensing fees. Many post-secondary institutions followed suit, suspending their license fee payments to Access Copyright between 2013 and 2015.

A 2015 impact assessment prepared for Access Copyright by PwC estimated the annual direct revenue loss for Canadian publishers at $30 million per year. In a 2018 submission to the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage, the Association of Canadian Publishers explained the full weight of that lost revenue:

“The loss of this licensing revenue has had a greater impact than would an equivalent loss of sales of finished books. Ten million dollars in lost book sales is the equivalent of approximately $1 million in lost profit. Because licensing revenue is received by publishers net of all expenses, $10 million in lost licensing revenue is $10 million in profits lost to authors and publishers. Lost licensing revenue is exacerbated by an unknown loss of primary book sales.”

Put another way, Canadian publishers would have to generate the equivalent of an additional $300 million in gross sales to offset the bottom-line impact of $30 million in lost licensing revenue. To put that in context, BookNet Canada reported total print sales for Canadian-owned publishers (in English Canada) of just under $900 million in 2019.

On top of that lost revenue, Access Copyright has been locked in legal challenges with the education system, as arguments over the fair dealing provisions continue to proceed through the courts. Initial decisions on the matter remain under appeal at this timeFootnote 19.

PwC’s 2015 analysis projected a number of outcomes arising from the fair dealing guidelines, including that:

- Canadian publishers would reduce their title output, or would stop producing titles for educational use altogether;

- Publisher sales to the education sector would further decline;

- Publishers would in particular reduce their investment in titles tailored for the Canadian market; and

- A reduction in the diversity and quality of materials available to Canadian educators.

Based on our interviews for this paper, it would appear that all of those concerns have been borne out in the years since. Each of the six publishers profiled here cited the continuing ambiguity around the 2012 copyright legislation as one of the most significant changes and challenges for the industry, and an issue still in urgent need of clarity.

“The most enduring impact of [the 2012 copyright legislation] is the difficulty in selling to Canadian schools when the message they get from the Ministry is, ‘Take what you want and don’t worry about paying for it,’” says Orca’s Andrew Wooldridge.

“I’m convinced our material is being used in ways it shouldn't be,” echoes Annie Gibson from Playwrights. “When I'm at events, the number of people that walk up to me and say, ‘Oh great, I'll photocopy this for my students,’ is just awful. One playwright was invited to a university class and found that all students were sitting there with photocopied copies of his book and learned that the professor in question had been doing the same for the last six years. I never saw these things before copyright reform, but after 2012 it became the wild west."

That comment reflects a perspective among many publishers that the copyright triggered a cultural shift, and that is has fueled an expectation of free content in the years since. This is an observation shared by all of the publishers in our sample. “Copyright reform is training people that content is free,” says Alana Wilcox. And Errol Sharpe adds that, “As free use of copyright material increases, publishing for post-secondary becomes more and more unsustainable. We can’t give stuff away free. The only way we get paid for doing the work we do is by selling our books."

As with all other publishers in our sample, Playwrights reports an immediate and deep drop in licensing revenues immediately following the 2012 legislation. Gibson says as well that licensing revenues made a modest recovery in the years following but only because the press actively pursues direct licensing deals with educators where possible and has shifted staff priorities to account for this additional work. “I used to spend summers acquiring plays and other publishing work,” she says. “Now I spend them working on licensing arrangements."

For Coach House, that revenue loss amounted to, “$10,000 a year off our bottom line, and another $20,000 in lost sales because profs are using our books for free.” Portage & Main Press Publisher Catherine Gerbasi adds that, “We saw an immediate drop in revenue from Access Copyright [after 2012]. AC revenue could make the difference between profit and loss in any given year, it was that significant.”

The following pages will expand on these observations with some additional detail from the last two publishers in our study sample: Broadview Press and Portage & Main.

Publisher’s perspective - Leslie Dema

“We have seen a decrease in revenues from licensing [royalties via Access Copyright],” says Broadview Press President Leslie Dema. “But the bigger impact is the interpretation that works can be freely used online and in course packs and therefore course adoptions have fallen significantly.”

She adds that, "The majority of our sales used to be to the Canadian market, but that has shifted to the US. It is harder now to make products for the Canadian market – the market is shrinking because people are using free resources. So the conclusion we came to was that we'll adjust our publishing program: we'll publish fewer materials specific to the Canadian market and fewer materials for upper-level classes."

Founded in 1985, Broadview is an independent academic publisher focused on publishing in the humanities for the post-secondary market. The company is well known for its landmark anthologies and other major works requiring extensive up-front investments.

"We think about what the profs and students needs intensively,” says Dema. “We are most closely connected with Canadian professors. In a non-pandemic year, we have a large team of representatives who are on campuses across Canada and the US. But partly because of curriculum changes in past decade, profs want shorter works. They say students are reluctant to read longer works so that affects what we acquire and publish. Page count has gone down dramatically in the past decade. People used to want the whole essay, the whole work; now in many cases they are happy to have excerpts."

She adds that, “New editions of anthologies for the Canadian market aren't doing as well. Our biggest project right now is an American literature anthology."

The company’s 2019 annual report makes reference to the same US-focused project: “[We have made] increased investments in the sales and editorial staff, and in long-term editorial projects, the most notable of which is the Broadview Anthology of American Literature, which will still be in development over the next couple of years.” Looking ahead, Dema sees additional investments in digital content. “We are making major adaptations to improve our digital offerings, and to achieve wider distribution of our e-books. One big investment in 2020 was in clearing digital rights that we previously didn't have, which reflects a greater focus generally on acquiring and promoting digital rights and digital editions.”

Selected indicators for Broadview are summarized in the table below and reflect a gradual and steady pattern of growth over the reference period. What is not obvious in the table is the profound shift toward US sales since 2008. In that year, US sales accounted for half of company revenues. By 2020, the US share had risen to nearly two-thirds of overall sales (63%).

| 2008 | 2012 | 2016 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title Output | 50 | 45 | 44 | 31 |

| Staff | 26 | 26 | 26 | 32 |

| RevenueFootnote 20 | 100 | 99 | 112 | 131 |

Source: Broadview

Publisher’s perspective - Catherine Gerbasi

Portage & Main Press Publisher Catherine Gerbasi has a different perspective on the impact of the 2012 copyright legislation, and it starts with the wedge that the copyright dispute has driven between publishers and educators. “That collaborative relationship we had with ministries of education is now gone,” she says. “Previously, we would have directly engaged with ministry around curriculum and resource planning, which would have fed directly into the development of new learning materials. Our publishing decisions are different now. We've pulled back in terms of our engagement with the educational sector because of the closed doors and barriers arising from copyright reform.”

Gerbasi adds that, "This simply means at the end of the day less choice for educators. You don't get those nuanced educational resources that are written by Canadians for Canadian students. Without that revenue coming in, you are not [as a publisher] putting it back into the development of new resources.” As a result, she says that “The education market is stagnant. When you go to major conferences, you just see the shrinkage in terms of what companies are offering.

“Without some sort of resolution [of the copyright dispute] very soon those relationships between publishers and the education system are only going to get worse. It's been going on too long and the government needs to take action.”

Founded in 1967, Portage & Main (PMP) publishes a wide range of innovative and practical educational resources. The press focuses on materials that inspire child-centred, inclusive learning while prioritizing Indigenous and marginalized voices. The catalogue includes hands on classroom resources, inquiry and inclusion texts, novels, graphic novels, and teacher guides. Through its HighWater Press (HWP) imprint, the press also publishes a complementary list of award-winning children's and young adult titles by emerging and established Indigenous writers.

In the absence of that direct engagement with ministries of education, Gerbasi says that Portage & Main now approaches acquisitions more like a trade publisher. “Who are the emerging, innovative authors/educators? What are the trends? And we have a greater focus on Indigenous pedagogies and knowledge. This marks a fundamental change in our acquisitions and publishing processes. We’re not competing for major textbook contracts (the big publishers will get those). Instead, we are developing a niche in Indigenous, inclusive education and we take those decisions to publish for schools or to renew our books based on street-level inputs from teachers or librarians.”

The following table tells the story of that major disruption for the company after 2012, and its recovery and growth over the last several years. Looking ahead, the press is putting an even greater emphasis on export sales, including right sales. “Last year, our export sales grew significantly and sales of HWP titles exceeded PMP sales for the first time,” says Gerbasi.

| 2008 | 2012 | 2016 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title Output | 9 | 7 | 11 | 18 |

| Staff | 8 | 8 | 10 | 7 |

| RevenueFootnote 21 | 100 | 65 | 76 | 125 |

Source: Portage & Main

Closing

The publishers we have sampled in this paper offer some powerful examples of a resilient sector that is working hard to respond and adapt to change, to develop new sales channels, and to navigate a marketplace where several important aspects of change are unfolding at the same time.

As we have seen, there are a number of important shifts in how Canada’s independent presses acquire, publish, and market their books. Some of these are informed by technology, but some reflect a larger ambition on the part of publishers to reach new markets and readers.

The 2012 copyright reform looms large as a priority issue for the industry, and no wonder given its wide-ranging effects. The financial impacts on publishers are clearly significant. But what we learn from the publishers profiled here is that the copyright issue has had important cultural effects as well. It has undermined the value of published work, contributed to an expectation of free content, and diverted publisher focus and investments away from publishing Canadian-authored work for Canadian classrooms.

As much as anything else, the lesson to be learned from the publishers profiled throughout this paper is that the industry is seeking balance amidst all of this change. Balance in terms of the interests of publishers and their trading partners across the supply chain. Balance with respect to leveraging technology to enable and encourage connections between authors, publishers, and readers. And also in terms of the natural affinity and shared interests that publishers and educators have in ensuring high-quality resources for Canadian classrooms.