Updated Assessment of Inherent Risks of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing in Canada

March 2023

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Forward Looking Plan

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Risk Mitigation

- Chapter 2: Overview of the Methodology to Assess Inherent Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Risks in Canada

- Chapter 3: Assessment of Money Laundering Threats

- Chapter 4: Assessment of Terrorist Financing Threats

- Chapter 5: Assessment of Inherent Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Vulnerabilities

- Chapter 6: Results of the Assessment of Inherent Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Risks

- Evolution of the Risk Landscape in Canada

- Next Steps

- Annex: Key Consequences of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing

- Glossary

- List of Key Acronyms and Abbreviations

Executive Summary

Canada has a robust and comprehensive Anti-Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorist Financing (AML/ATF) Regime, which promotes the integrity of the financial system and the safety and security of Canadians. It supports combating transnational organized crime and is a key element of Canada’s counter-terrorism strategy.

The Government of Canada first conducted an assessment to identify inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks in Canada in 2015 when it published the Assessment of Inherent Risks of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing in CanadaFootnote 1 (the 2015 Report). Since 2015, the government has been monitoring and assessing new risks on a continual basis and developed internal analysis to ensure that its understanding of these risks remains current and up-to-date. In conjunction with this, various government partners and agencies such as the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC), have also published strategic intelligence reports to promote the awareness of new emerging trends in risks by reporting entities and the public. This report consolidates the work conducted before the release of the 2015 report and between 2015 and 2020 to provide a systematic and comprehensive update of all the areas assessed in 2015 using a similar approach and methodology. Furthermore, it also extends Canada’s assessment to other new areas not assessed in 2015.

It is important to note that this report provides an overview of the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing before the application of any mitigation measures. Those measures include a range of legislative, regulatory and operational actions that prevent, detect and disrupt money laundering and terrorist financing. Sectors confronted with higher inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks assessed in this report typically also have strong mitigation measures in place to limit those risks. The report presents overall vulnerabilities and risks, such as for sectors or products as a whole. Risks and risk mitigation practices will vary, and so in practice, should be considered on a case-by-case basis. This report is a tool to support that assessment.

Canada’s AML/ATF Regime provides a coordinated approach to mitigating the inherent risks identified in this assessment and in combating money laundering and terrorist financing more broadly. The AML/ATF Regime is operated by 13 federal Regime partners, which all contributed to the development of the report, coordinated by the Department of Finance Canada (Finance Canada). The inherent risks identified are being addressed through a strong regime that focuses on policy coordination, both domestically and internationally; the prevention and detection of money laundering and terrorist financing in Canada; disruption activities, including investigation and prosecution and the seizure of illicit assets; and the implementation of measures to continually enhance the AML/ATF Regime.

This report provides critical risk information to the public and, in particular, to over 24,000 regulated entities across the countryFootnote 2 that have reporting obligations under the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act (PCMLTFA), whose understanding of inherent, foundational money laundering and terrorist financing risks is vital in applying the preventive measures and controls required to effectively mitigate these risks. Building off of the 2015 Report, the Government of Canada encourages these entities to use the findings in this report to continue to inform their efforts in assessing and mitigating risks. Having an up-to-date understanding of Canada’s risk context and the intrinsic properties that expose sectors and products to inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks in Canada is important in being able to apply measures to effectively mitigate them.

This updated report also responds to the Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF) global AML/ATF standards calling on all members to assess money laundering and terrorist financing risks on an ongoing basis. This report will be considered as part of the next FATF Mutual Evaluation of Canada, which will assess Canada against these global standards.

The inherent risk assessment consists of an assessment of the money laundering and terrorist financing threats and inherent money laundering and terrorist financing vulnerabilities in Canada as a whole (e.g., economy, geography, demographics) and the country’s key economic sectors and financial products, while taking into account the consequences of money laundering and terrorist financing. The overall inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks were assessed by matching the threats with the inherently vulnerable sectors and products through the money laundering and terrorist financing methods and techniques that are used by money launderers, terrorist financiers and their facilitators, to exploit these sectors and products. By establishing a relationship between the threats and vulnerabilities, a series of inherent risk scenarios were constructed, allowing one to identify the sectors and products that are exposed to the highest money laundering and terrorist financing risks.

The money laundering threat assessment examined 23 criminal activities in Canada that are most associated with generating proceeds of crime that may be laundered. It also examined the money laundering threat emanating from third-party money laundering, which includes the use of money mules, nominees and professional money launderers. The money laundering threat was rated very high for illicit drug trafficking, certain types of fraud, illegal gambling, corruption, collusion and bribery, and third-party money laundering. Transnational organized crime groups (OCGs) and professional money launderers are the key money laundering threat actors in the Canadian context. Many of these threats are similar to those faced by several other countries.

The terrorist financing threat was assessed for the groups and actors listed by the United Nations and Canada that are of greatest concern to Canada. The assessment indicates that there are networks operating in Canada that are suspected of raising, collecting and transmitting funds abroad to various errorist groups. However, based in part on the existing strengths of the regime, the terrorist financing threat in Canada is not as pronounced as in other regions of the world, where weaker anti-terrorist financing regimes can be found and where terrorist groups have established a foothold, both in terms of operations but also in financing their activities.

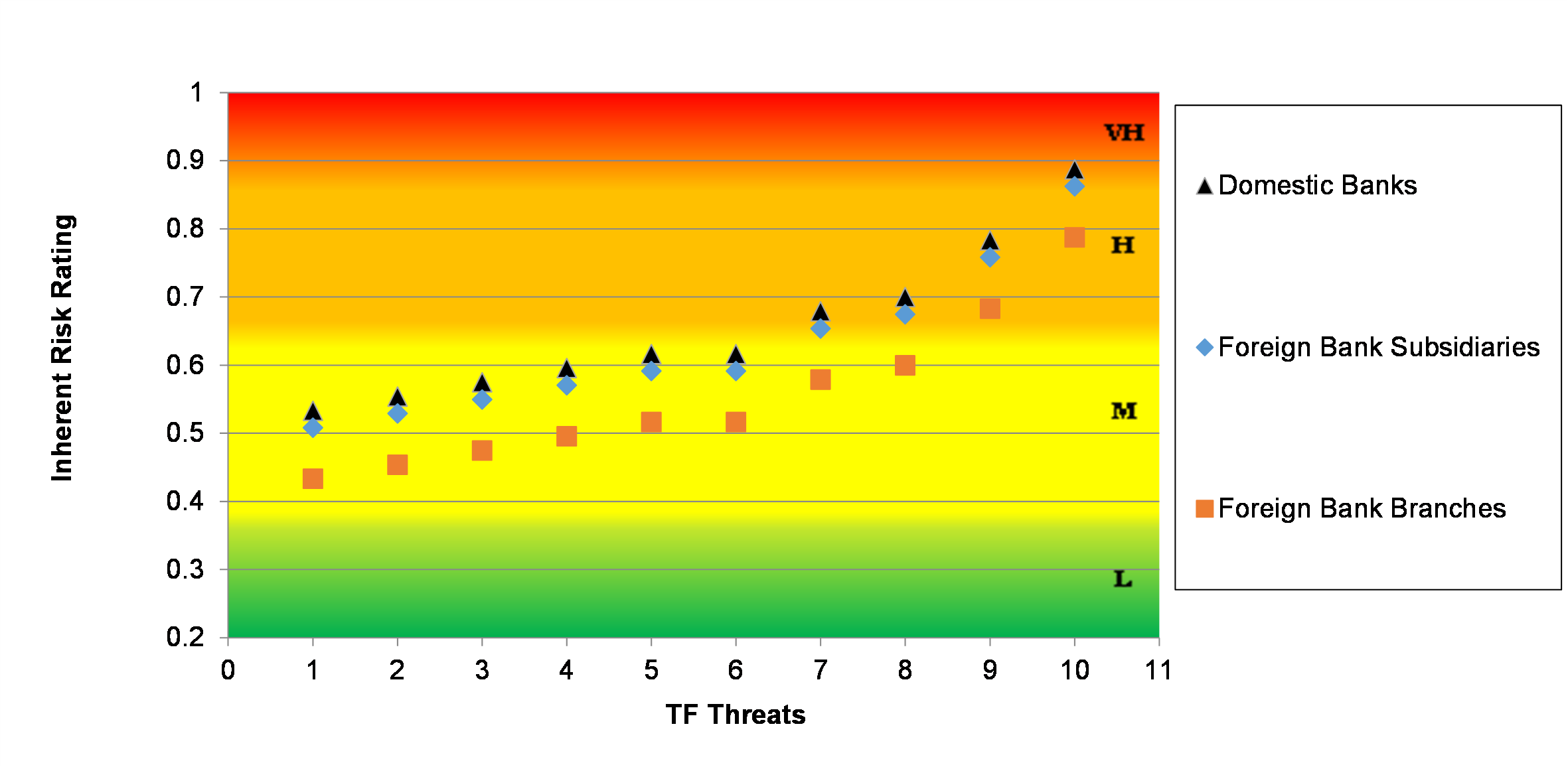

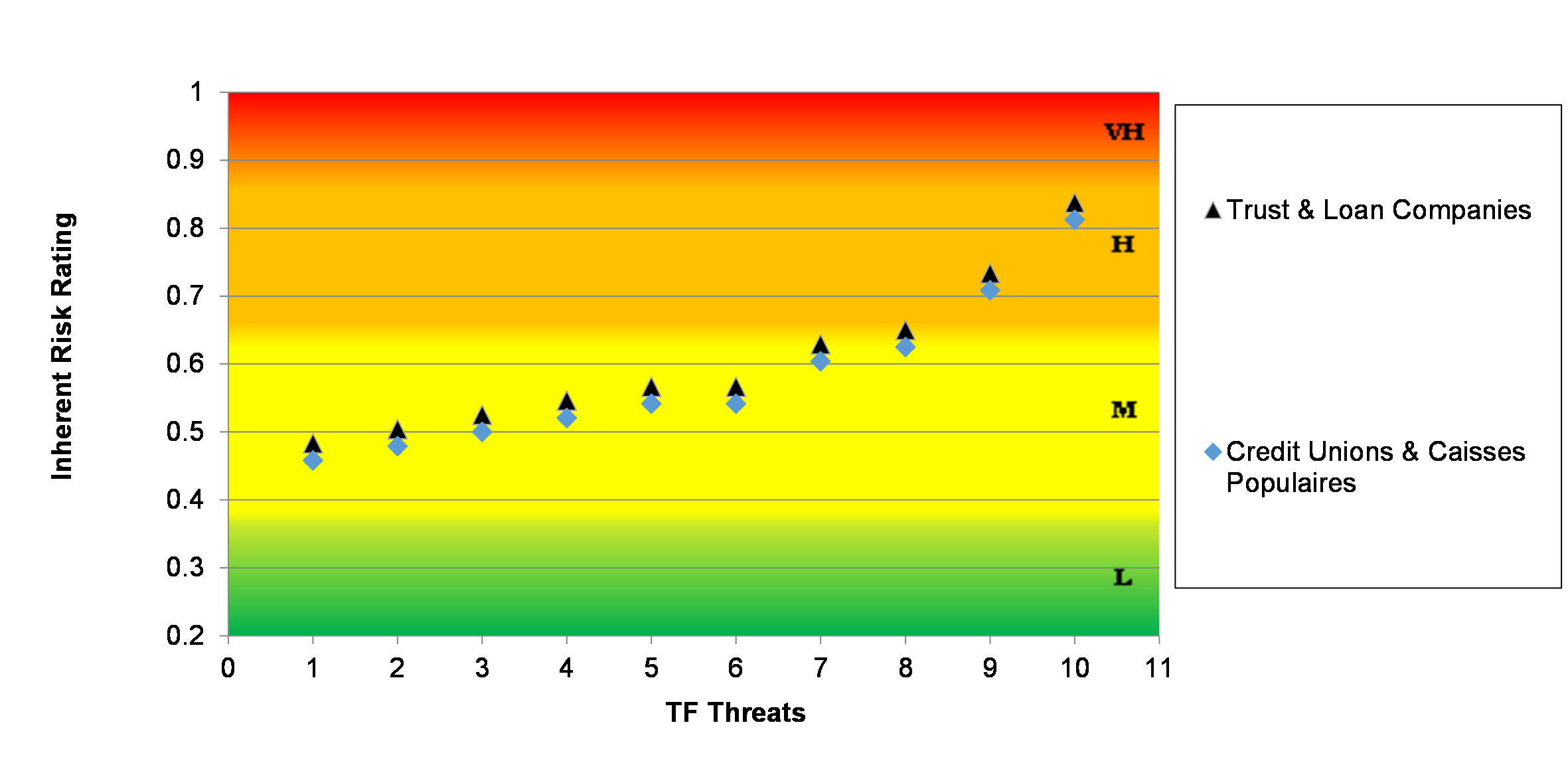

The inherent money laundering and terrorist financing vulnerabilities are presented for 33 economic sectors and financial products. The assessment indicates that there are many sectors and products that are highly vulnerable to money laundering and terrorist financing. Of the assessed areas, domestic banks, corporations (especially, private corporations), certain types of money services businesses and express trusts were rated the most vulnerable, or very high. In addition, 18 sectors and products had a vulnerability rating of high, nine sectors and products had a vulnerability rating of medium and one sector had a vulnerability rating of low. Many of the sectors and products are highly accessible to individuals in Canada and internationally and are associated with a high volume, speed and frequency of transactions. Many conduct a significant amount of transactional business with high-risk clients and are exposed to high-risk jurisdictions that have weak AML/ATF regimes and significant money laundering and terrorist financing threats. There are also opportunities in many sectors to undertake transactions with varying degrees of anonymity and to structure transactions in a complex manner.

By connecting the threats with the inherently vulnerable sectors or products, the assessment revealed that a variety of them are exposed to very high inherent money laundering risks involving threat actors (e.g., OCGs and third-party money launderers) laundering illicit proceeds generated from ten groups of profit-oriented crimes. The assessment also identified four very high inherent terrorist financing risk scenarios that involve six different sectors that have been assessed to be very highly vulnerable to terrorist financing, combined with one high terrorist financing threat group of actors.

This update to Canada’s risk assessment highlights the importance of maintaining a shared understanding of inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks in Canada on an ongoing basis. Criminal threats can evolve over time as criminals continuously look for new methods and techniques to obfuscate the source of illicit funds, for example by leveraging technological innovation. In addition, it is important to retain an awareness that many money laundering and terrorist financing vulnerabilities, threats and methods can remain the same or consistent over time. As such, this report provides a comprehensive overview of the money laundering and terrorist financing threats, vulnerabilities and risks that have persisted since the 2015 report, as well as of new trends identified in the risk landscape’s evolution.

Based on additional evidence from this updated assessment, the threat levels for tax evasion, illegal gambling, and wildlife trafficking have increased since the 2015 report, while they decreased for illegal tobacco smuggling and trafficking. This was often a reflection of changes in the average sophistication and capability exhibited by the threat actors involved. For example, concerns around tax evasion have increased following growing trends around the usage of complex offshore corporate structures and accounts and the leveraging of expertise from facilitators such as lawyers, accountants and financial advisors.

Some threat levels remained the same but were marked by new dynamics and trends that push government and private sectors to adapt. New typologies of threats and vulnerabilities have notably emerged from the fentanyl trade, new types of online mass-marketing fraud, capital market fraud and extortion schemes. Growing vulnerabilities in the real estate market partly a result of rapid price increases in some regions of Canada and constant technological developments around virtual assets were other notable trends.

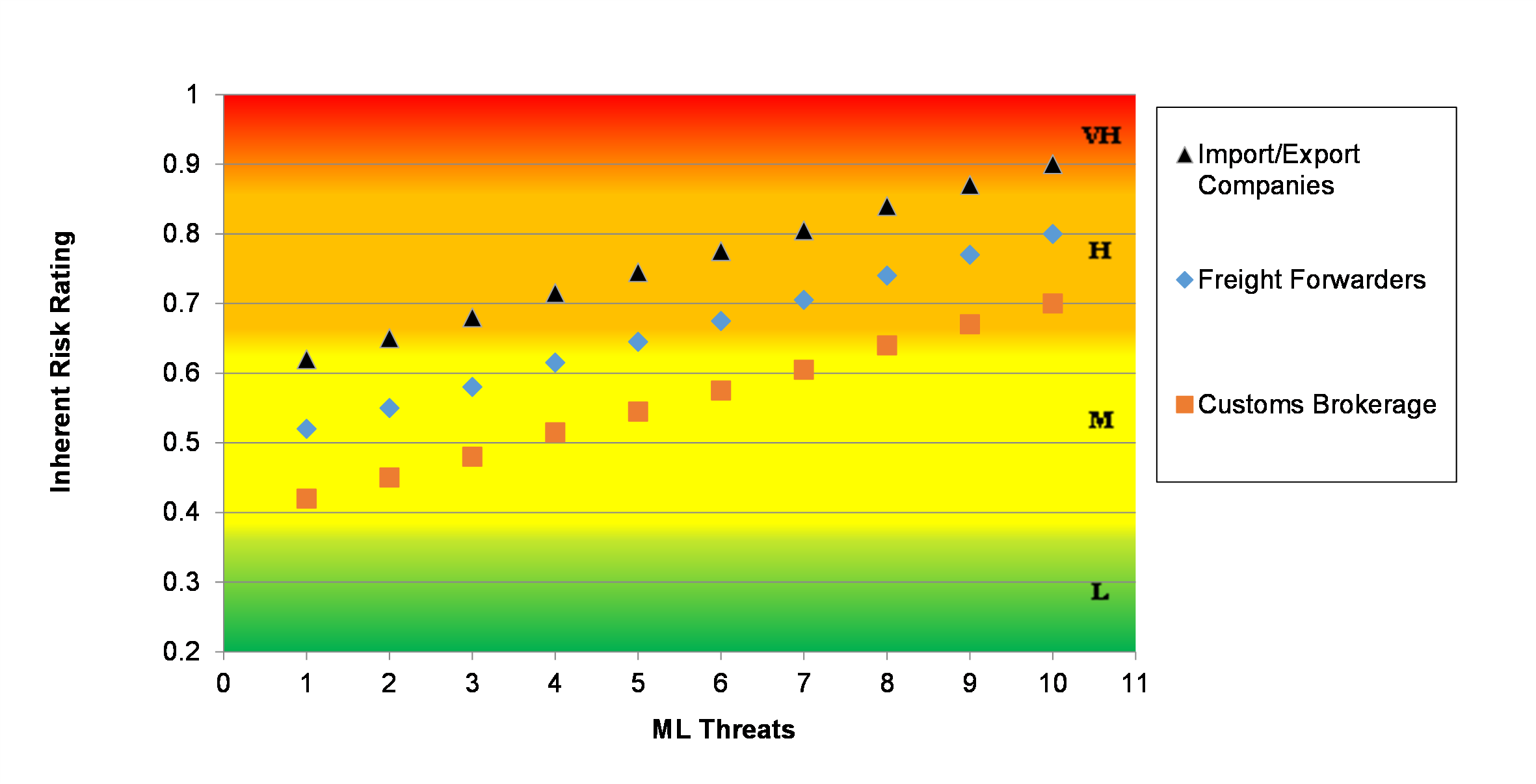

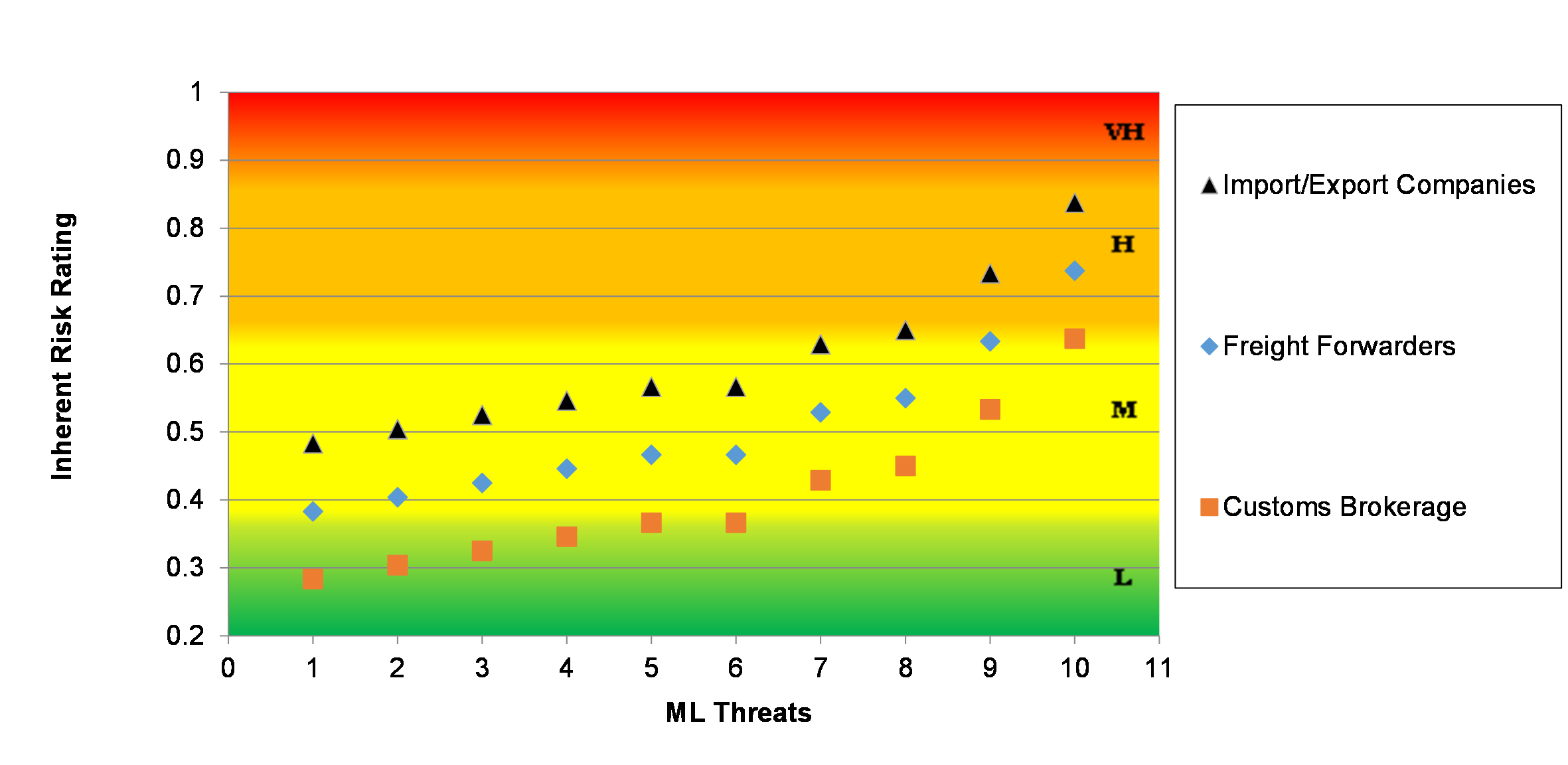

This update to Canada’s risk assessment also broadens the scope of the risks assessed in 2015. New issues assessed in this update include, among others, potential money laundering threats generated by illegal fishing activities, as well as inherent vulnerabilities faced by the armoured car sector, partnerships, unregulated mortgage lenders, import/export companies, freight forwarders and custom brokers. Canada also conducted a preliminary terrorist financing threat assessment of ideologically motivated violent extremists.

Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic has helped demonstrate how adaptable the Canadian financial sector is, with more and more consumers adopting digital channels as well as new financial services and products being made available by emerging technologies. The pandemic has also shown that criminal actors are adapting in the current context by leveraging online schemes and COVID-related fraud to generate funds. The shift to digital platforms and financial products may also present new opportunities for criminals and terrorist organizations to move funds. Furthermore, border closures disrupted traditional cash-courier techniques and affected trade-based fraud methodologies, while regional lockdowns of non-essential businesses such as casinos led to reports of increased underground illegal gambling and related money laundering activities.

New experiences from the COVID-19 pandemic reinforce the importance of national authorities and the private sector monitoring and understanding of evolving risks on an ongoing basis. The updated assessment has and will continue to help enhance Canada’s AML/ATF Regime, further strengthening the comprehensive approach it already takes to risk mitigation and control domestically, including with the private sector and with international partners. It also complements and completes the various information and documents published by the government since 2015 around new risks and typologies observed in relation to certain sectors or specific issues as they were unfolding.

Forward Looking Plan

The Updated Assessment of Inherent Risks of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing in Canada, unless otherwise noted, reflects analysis that was available up to December 2020. Certain targeted updates have been made to the report to communicate early findings for new and emerging risks, such as Ideologically Motivated Violent Extremism.

Emerging risks such as the use of crowdfunding platforms, payment service providers, cryptocurrency as well as the risk of actors trying to evade sanctions, for example, in relation to Russia’s unprecedented aggression towards Ukraine will continue to be monitored. Future updates on these risks will be included in subsequent updates to this report.

Introduction

Money laundering and terrorist financing compromise the integrity of the international financial system and are a threat to global safety and security. Money laundering is the process used by criminals to conceal or disguise the origin of criminal proceeds to make them appear as if they originated from legitimate sources. Money laundering frequently benefits the most successful and profitable domestic and international criminals and organized crime groups. Terrorist financing, in contrast, is the collection and provision of funds from legitimate or illegitimate sources for terrorist activity. It supports and sustains the activities of domestic and international terrorists that can result in terrorist attacks in Canada or abroad causing loss of life and destruction.

The Government of Canada is committed to combating money laundering and terrorist financing, while respecting the Constitutional division of powers, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the privacy rights of Canadians. To do so, the Government of Canada has put in place a robust and comprehensive Anti-Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorist Financing (AML/ATF) Regime. The Regime is operated by 13 federal departments and agencies each responsible for certain elements according to their mandates and expertise, coordinated by Finance Canada. Provincial and municipal law enforcement bodies and provincial financial sector and other regulators are also involved in combating these illicit activities. Within the private sector, there are over 24,000 Canadian financial institutions and non-financial businesses and professionsFootnote 3 with reporting obligations under the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act (PCMLTFA), known as reporting entities that play a critical frontline role in efforts to prevent and detect money laundering and terrorist financing.

Regime partners’ understanding of money laundering and terrorist financing risks plays a key role in the government’s ability to effectively combat these illicit activities. That understanding helps to support the policy-making process to effectively address vulnerabilities and other potential gaps in the Regime. It helps to inform operational decisions about priority setting and resource allocation to combat threats and to focus on those that have the greatest economic, social and political consequences. It also plays a central role in how the private sector, especially reporting entities, applies its risk-based approaches and mitigates their risks. Overall, Regime partners’ understanding of risks helps them focus on adequately mitigating the risks of greatest concern in Canada.

Given the central role that the understanding of risk plays in the Regime, the Government of Canada has built on existing practices to update the 2015 Assessment of Inherent Risks of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing in Canada (the 2015 Report).Footnote 4 This update consists of building on the foundational risk assessment that was published in 2015. This report presents the results of the updated assessment of inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks in Canada. These are the fundamental risks in Canada, which the AML/ATF Regime seeks to control and mitigate.

This report specifically examines these risks in relation to key economic sectors and financial products in Canada and it assesses the extent to which key features make Canada vulnerable to being exploited by threat actors to launder funds and to finance terrorism. It is meant to raise awareness about Canada’s risk context and the intrinsic properties that expose these sectors and products to money laundering and terrorist financing risks in Canada. The vast majority of businesses, professions and sectors assessed in this report follow Canadian laws and contribute to the social and economic prosperity of the country; only a very small subset of actors are complicit in illicit activities such as money laundering.

Nonetheless, properly understanding these inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks is critical in being able to identify and apply measures to effectively mitigate them. In this regard, the Government expects that this updated report will be used by financial institutions and other reporting entities to understand how and where they may be most vulnerable and exposed to inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks. The report presents overall vulnerabilities and risks, such as for sectors or products as a whole. Risks and risk mitigation practices will vary, and so in practice, should be considered on a case-by-case basis. This report is a tool to support that assessment. The report complements other analysis undertaken by Regime partners and will contribute to setting priorities and assessing the effectiveness of measures to address money laundering and terrorist financing risks.

The first chapter describes Canada’s AML/ATF Regime and the comprehensive approach taken to mitigate the inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks that are the subject of this assessment. The second chapter provides a general description of the methodology used to assess the inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks in Canada, while the subsequent three chapters present the results of the updated assessment of the money laundering and terrorist financing threats and inherent money laundering and terrorist financing vulnerabilities. These components of risk are then combined in the final chapter to provide an assessment of the inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks in Canada, including setting out a number of inherent risk scenarios and case examples.

Unless otherwise noted, the content of the report reflects what was available up to December 31, 2020, and it excludes some information, intelligence and analysis for reasons of national security.

Chapter 1: Risk Mitigation

Canada has a comprehensive AML/ATF Regime that provides a coordinated approach to mitigating the inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks identified in this assessment and in combating money laundering and terrorist financing more broadly. This chapter will briefly review the framework that exists in Canada to prevent, detect and disrupt money laundering and terrorist financing. The Regime also complements the work of law enforcement and intelligence agencies engaged in fighting domestic and transnational organized crime as well as terrorism, notably as part of Canada’s Counter-Terrorism Strategy.Footnote 5

The AML/ATF Regime is operated by 13 federal Regime partners, nine of which receive incremental funding totalling nearly $70 million annually from the AML/ATF horizontal funding initiative.Footnote 6 The nine funded partners are the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), Finance Canada, Justice Canada, the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC), the Public Prosecution Service of Canada (PPSC), Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). The remaining four Regime partners are Global Affairs Canada (GAC), Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED), the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) and Public Safety Canada. Although not receiving dedicated funding from the AML/ATF horizontal funding initiative, these four partners make important contributions to the Regime.

The AML/ATF Regime operates on the basis of three interdependent pillars: (i) policy and coordination; (ii) prevention and detection, and (iii) disruption.

(i) Policy and Coordination

The first pillar consists of the Regime’s policy and legislative framework as well as its domestic and international coordination, which is led by Finance Canada. The PCMLTFA is the legislation that establishes Canada’s AML/ATF framework, in conjunction with other key statutes, including the Criminal Code.

The PCMLTFA requires prescribed financial institutions as well as certain non-financial businesses and professions,Footnote 7 known as reporting entities, to identify their clients, keep records and establish and administer an internal AML/ATF compliance program. The PCMLTFA creates a mandatory reporting system for suspicious financial transactions, large cross-border currency transfers, and certain other prescribed transactions. It also creates obligations for the reporting entities to identify money laundering and terrorist financing risks and to put in place measures to mitigate those risks, including through ongoing monitoring of transactions and enhanced customer due diligence measures.

The PCMLTFA also establishes an information sharing regime where, under prescribed conditions respecting individuals’ privacy, information submitted by the reporting entities is analyzed by FINTRAC and the results are disseminated to Regime partners. The information disseminated under the PCMLTFA can be intelligence used to support domestic and international partners in the investigation and prosecution of money laundering and terrorist financing related offences, or can be in the form of trends and typologies reports used to educate the public, including reporting entities, on money laundering and terrorist financing issues. In addition to the PCMLTFA, other statutes also contribute a comprehensive AML/ATF Regime. For example, the Income Tax Act creates obligations around trusts registration with CRA, while the Canadian Business Corporations Act sets out beneficial ownership transparency requirements for federally incorporated companies.

Given the number of Regime participants and the complexity of money laundering and terrorist financing issues, the effective regime-wide coordination of strategic, policy and operational matters is important. All federal partners share responsibility for the outcomes of the Regime, which is governed by various inter-departmental committees with the participation of senior officials from each organization. These committees work together to maintain an efficient regime with a focus on both policy and operations.

There is also frequent collaboration and discussion between the public and private sectors. For example, the Advisory Committee on Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing (ACMLTF) is a public-private discussion forum to support emerging issues and overall AML/ATF policy.Footnote 8 Private sector representatives are invited to provide their perspective and advice on Canada’s AML/ATF Regime both within a domestic context, including its effectiveness and efficiency, and in support of international work. ACMLTF also provides an opportunity for the Government to provide valuable feedback to the private sector on overall AML/ATF trends and efforts. This committee benefits all participants by fostering more effective communication and results for the regime writ large.

In addition, given that many serious forms of money laundering and terrorist financing often have international dimensions, Canada’s cooperation internationally is also a key component. International cooperation is a core practice of the Regime, and for many partners it is conducted on a routine basis, in particular in supporting investigations and prosecutions of money laundering and terrorist financing. This includes information exchanges between FINTRAC and other financial intelligence units from partner countriesFootnote 9 and through formal mutual legal assistance led by Justice Canada.

Canada recognizes that protecting the integrity of the international financial system from money laundering and terrorist financing requires playing a strong international role to broadly increase legal, institutional, and operational capacity globally. Canada’s international AML/ATF initiatives are advanced through the leadership role that it plays in the FATF, the G-7, the G-20, the Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units and the counter-financing work stream of the Global Coalition against Daesh.Footnote 10

Canada is a founding member of the FATF and an active participant. The FATF develops international AML/ATF standards, and monitors their effective implementation among the 39 FATF members and over 200 countries in the global FATF network through peer reviews and public reporting. The FATF also leads international efforts related to policy development, risk analysis and identifies and reports on emerging money laundering and terrorist financing trends and methods. This work helps to ensure that countries have the appropriate tools in place to address money laundering and terrorist financing risks. Canada also provides expertise and funding to increase AML/ATF capacity in countries with weaker regimes, including through the Anti-Crime Capacity Building Program and the Counter-Terrorism Capacity Building Program, which are led by GAC.

(ii) Prevention and Detection

The second pillar provides strong measures to prevent individuals from placing illicit proceeds or terrorist-related funds into the financial system, while having correspondingly strong measures to detect the placement and movement of such funds. At the centre of this prevention and detection approach are the reporting entities who are core to the financial system and implement the prevention and detection measures under the PCMLTFA, and the regulators, FINTRAC and OSFI principally, that supervise them. FINTRAC is the primary agency conducting AML/ATF assessments of federally regulated financial institutions to promote compliance with the PCMLTFA and its associated regulations, whereas OSFI focuses on the prudential implications of a federally regulated financial institution’s AML/ATF compliance, as part of its ongoing assessment of their regulatory compliance management frameworks.

Greater transparency of corporations and trusts also contributes to preventing and detecting money laundering and terrorist financing. This is fostered by requirements on financial institutions, money services businesses (MSBs), life insurance dealers, and securities dealers to identify the beneficial owners of the corporations and trusts with whom they do business.Footnote 11 Provincial and federal corporate laws, registries and securities regulations also contribute in preventing and detecting money laundering and terrorist financing in Canada. Recent and ongoing federal, provincial and territorial legislative changes will require that information on the beneficial ownership of corporations is made available to relevant law enforcement agencies and authorities on a timely basis. As part of Budget 2022 the government committed to a publicly accessible beneficial ownership registry of federally incorporated businesses by 2023.

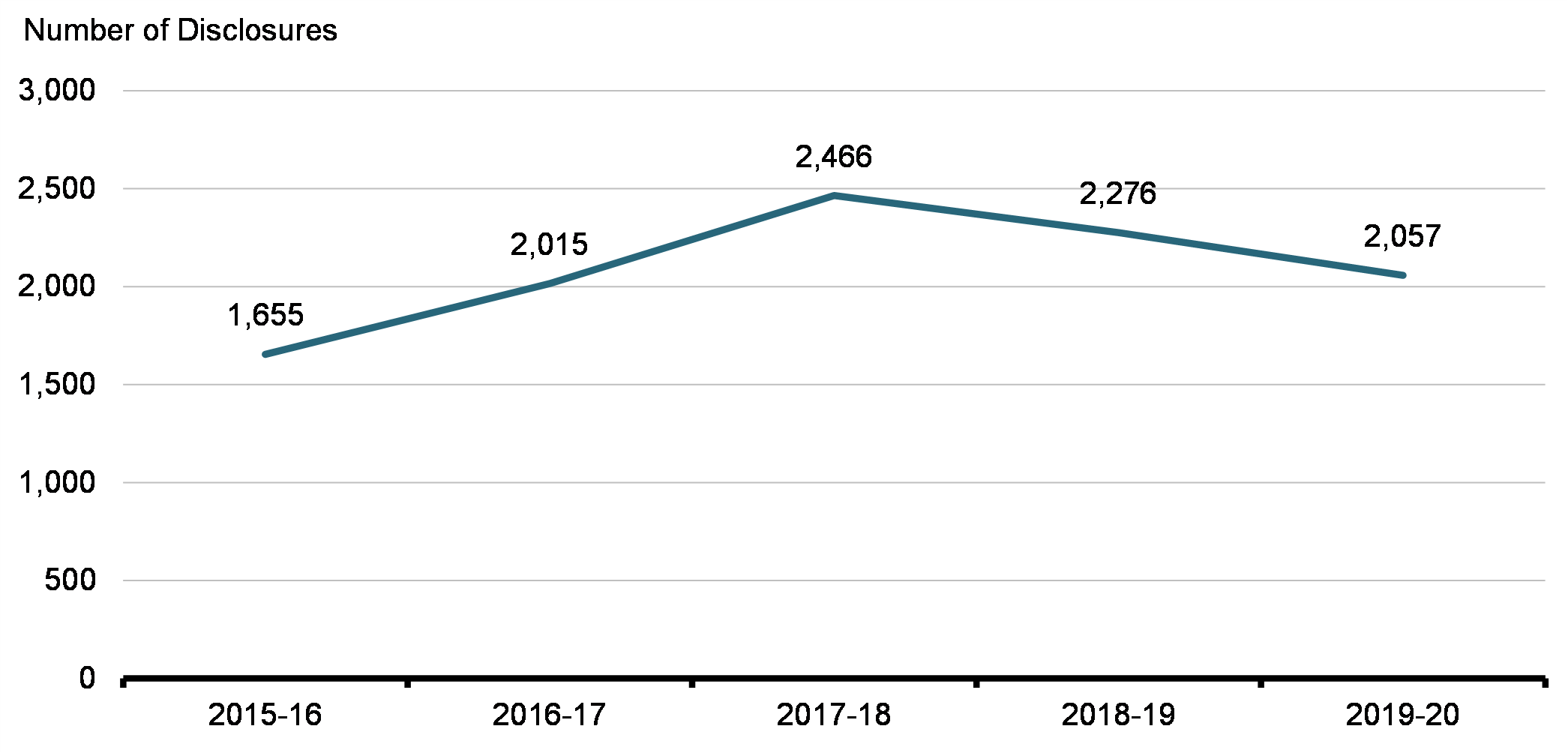

FINTRAC is also Canada’s financial intelligence unit; it acts at arm's length and is independent from the police services, law enforcement agencies and other entities to which it is authorized to disclose financial intelligence. The chart below provides the annual number of cases disclosed by FINTRAC to partners from 2015-16 to 2019-20. For example, in 2019-20, FINTRAC made 2,057 disclosures to Regime partners. Of these, 1,582 were associated with money laundering, while 296 dealt with cases of terrorist activity financing and other threats to the security of Canada. 179 disclosures dealt with all three areas.

FINTRAC Case Disclosure from 2015-16 to 2019-20Footnote 12

(iii) Disruption

The final pillar deals with the disruption of money laundering and terrorist financing. Regime partners, such as CSIS, CBSA and the RCMP, supported by FINTRAC’s intelligence disclosures and analysis activities, undertake financial investigations in relation to money laundering, terrorist financing, and other profit-oriented crimes. CRA also plays an important role in investigating tax evasion and its associated money laundering and in detecting charities that are at risk and taking actions to prevent them from being abused to finance terrorism. CBSA administers the Cross-Border Currency Reporting program, and transmits information from reports and seizures to FINTRAC.

Ultimately, PPSC prosecutes financial crimes to the fullest extent of the law. The restraint and confiscation of proceeds of crime is also an important law enforcement component of the Regime. PSPC manages all seized and restrained property for criminal cases prosecuted by the Government of Canada.

The Regime also has a robust terrorist listing process to freeze terrorist assets, pursuant to the Criminal Code and the Regulations Implementing the United Nations Resolutions on the Suppression of Terrorism, which is led by Public Safety Canada and GAC, respectively. Canada has 113 terrorist-related listings under the two processes.

Oversight and Enhancements

Canada’s AML/ATF Regime is reviewed on a regular basis by a variety of bodies to ensure that it operates effectively, in keeping with its legislative mandate, while respecting the Constitutional division of powers, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the privacy rights of Canadians.

The Parliament of Canada is required by statute to undertake a comprehensive review of the PCMLTFA, and indirectly the Regime, every five years. In addition to the parliamentary review, there are other periodic reports on performance,Footnote 13 reviews and audits, including a mandatory privacy audit of FINTRAC by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner every two years. Internationally, Canada’s Regime is assessed by the FATF against its global AML/ATF standards and is subject to the FATF’s follow-up process.

Since the publication of the 2015 Report, the Government has made significant amendments to its legislation and regulations. Notably, in July 2019, the Government finalized regulatory amendments to regulate money services businesses dealing in virtual currency, as well as to include foreign money service businesses (FMSBs) in Canada's AML/ATF Regime, update customer due diligence requirements and beneficial ownership reporting requirements, modernize client identification measures, update the schedules to the regulations, and clarify a number of existing requirements.Footnote 14 In June 2020, further regulatory amendments were finalized to apply stronger customer due diligence requirements and beneficial ownership requirements to certain businesses and professions, modify the definition of business relationship for the real estate sector, align customer due diligence measures for casinos with international standards, align virtual currency record-keeping obligations with international standards, and clarify the cross border currency reporting program.Footnote 15

As part of Budget 2019, the Government announced an investment of over $220 million starting in 2019-20 to modernize Canada’s AML/ATF Regime by strengthening federal policing operations and its technology infrastructure, increasing operational capacity for FINTRAC, strengthening available data resources, launching a pilot project to enhance information sharing, expertise, and coordination of financial crime investigations and prosecutions, building capacity and expertise related to trade-based money laundering (TBML)Footnote 16 and trade fraud, as well as increasing tax compliance and deterring financial crime in the real estate sectorFootnote 17. The Government also made amendments to the Criminal Code to add an alternative requirement of recklessness to the offence of money launderingFootnote 18.

In 2020, the Government announced additional funding of almost $700 million to combat financial crime. Approximately $70 million of that funding would be allocated directly to strengthening Canada’s AML/ATF framework and enhance FINTRAC’s effectiveness to identify and meet evolving threats.Footnote 19 $606 million will be used to fund new initiatives and extend existing programs to focus on individuals who avoid taxes by hiding income and assets offshore, enhance the audit function targeting higher-risk tax filings, including those of high-net worth individuals, and strengthen the CRA’s ability to fight financial crimes such as money laundering and terrorist financing by upgrading tools and increasing international cooperation.Footnote 20

Canada remains committed and engaged, both domestically and internationally, in the fight against money laundering and terrorist financing. The risks are present and evolving. Canada has a strong regime and it remains committed to take appropriate action to mitigate the money laundering and terrorist financing risks identified in this assessment and to continue to assess evolving risks on an ongoing basis.

Implementation

The Government of Canada expects that this report will be used by financial institutions and other reporting entities to contribute to their understanding of how and where they may be most vulnerable and exposed to inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks. FINTRAC will continue to include relevant information related to inherent risks in their guidance documentation to assist financial institutions and other reporting entities in integrating such information in their own risk assessment methodology and processes so that they can effectively implement controls to mitigate money laundering and terrorist financing risks. The valuable lessons learned from this exercise will also be used to help set priorities for policy development and operational efforts to combat money laundering and terrorist financing.

Chapter 2: Overview of the Methodology to Assess Inherent Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Risks in Canada

Overview

In 2015, the Government of Canada developed an assessment model to identify and understand inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks in Canada, and their relative importance, through a rigorous and systematic analysis of qualitative and quantitative data and expert opinion about money laundering and terrorist financing. This update uses the same methodology and continues to provide the basis to think critically and systematically about money laundering and terrorist financing risks, on an ongoing basis, as well as to promote a continued common understanding of these risks and their evolution. This chapter provides an overview of the risk assessment methodology.

Scope of the Methodology

The methodology continues to assess the inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks, which are the fundamental risks in Canada that are the subject of the broad suite of government and private sector controls and activities to effectively mitigate those risks. Understanding Canada’s risk context and the intrinsic properties that expose sectors and products to inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks in Canada is important to being able to identify and apply measures to effectively mitigate them.

The basis of the risk assessment is that risk is a function of three components: threats, inherent vulnerabilities and consequences. Furthermore, risk is viewed as a function of the likelihood of threats exploiting inherent vulnerabilities to launder illicit proceeds or fund terrorists and the consequences should this occur.

Key Definitions

Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Threats: a person or group who has the intention, or may be used as facilitators, to launder proceeds of crime or to fund terrorism.

Inherent Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Vulnerabilities: the properties in a sector, product, service, distribution channel, customer base, institution, system, structure or jurisdiction that threat actors can exploit to launder proceeds of crime or to fund terrorism.

Consequences of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing: the harm caused by money laundering and terrorism financing, including facilitating criminal and terrorist activity, on a society, economy and government.

Likelihood of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing: the likelihood of money laundering and terrorist financing threats exploiting inherent vulnerabilities.

The money laundering threat was assessed separately from the terrorist financing threat. Although there is some overlap, the nature of these criminal activities is different, warranting separate assessments. In contrast, the assessment of the money laundering and terrorist financing vulnerabilities did not require such separation since money laundering and terrorist financing threats seek to exploit the same set of vulnerable features and characteristics of products and services offered by sectors to launder proceeds of crime or to fund terrorism.

As a first step, the core components of the money laundering and terrorist financing threats and inherent vulnerabilities were identified and categorized. With these categories, criteria were developed to rate the extent of the money laundering and terrorist financing threats and the inherent money laundering and terrorist financing vulnerabilities. These ratings were then used to assess the likelihood of money laundering and terrorist financing occurring, which involved matching the threats with the inherent vulnerabilities, while considering the consequences of money laundering and terrorist financing, which then resulted in the assessment of inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks. The important types of economic, social and political consequences of money laundering and terrorist financing are identified in the Annex.

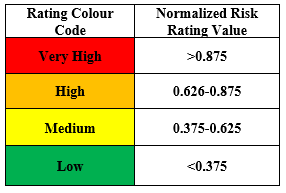

Assessing the ML/TF Threats and Inherent Vulnerabilities

Experts from Canada’s AML/ATF Regime, supported by a series of workshops, assessed the money laundering and terrorist financing threats and inherent vulnerabilities of sectors and products using the rating criteria set out in the methodology. In addition, the experts harnessed the Regime’s store of information, data and analysis to update and rate each threat and vulnerability. Experts provided ratings of low, medium, high or very high using the defined rating criteria to assess the range of threats and inherent vulnerabilities. The individual ratings were then aggregated to arrive at an overall rating.

The money laundering threat in Canada was assessed for 23 criminal activities that are most associated with generating proceeds of crime in Canada as well as the threat from third-party money laundering. The money laundering threat was rated for each criminal activity against four rating criteria, namely the extent of the threat actors’ knowledge, expertise and overall sophistication to conduct money laundering; the extent of the threat actors’ network, resources and overall capability to conduct money laundering; the scope and complexity of the money laundering activity; and the magnitude of the proceeds of crime being generated annually from the criminal activity. The money laundering threat rating results are presented in Chapter 3.

The money laundering risks Canada faces are global in nature. Canada-linked professional money launderers and transnational organized crime groups (OCG) launder proceeds of crime using complex global networks that involve multiple jurisdictions at all stages of the money laundering cycle. These jurisdictions vary significantly and change based on many factors including the OCG involved, the predicate offence from which the criminal proceeds are derived, and any intermediary jurisdictions where the trade or financial system can be exploited for the purposes of money laundering.

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) maintains a current list of global jurisdictions as posing higher risks for money laundering and terrorist financing.Footnote 21 For all countries identified as high-risk, the FATF calls on all members and urges all jurisdictions to apply enhanced due diligence, and, in the most serious cases, countries are called upon to apply counter-measures to protect the international financial system from the money laundering, terrorist financing, and proliferation financing risks emanating from the jurisdiction.

The terrorist financing threat in Canada was assessed for terrorist groups as well as for foreign terrorist fighters that, based on financial and other intelligence available, are considered either because they represent the greatest risk of engaging in terrorist financing activities, or due to the emerging terrorist financing risks they pose. Foreign terrorist fighters are defined as those who travel abroad to support and fight alongside terrorist groups. The terrorist financing threat of these groups was assessed against six rating criteria, namely the extent of the threat actors' knowledge, expertise and overall sophistication to conduct terrorist financing; the extent of the threat actors' network, resources and overall capability to perform terrorist financing operations; the scope and global reach of their terrorist financing operations; the estimated value of their fundraising activities annually in Canada; the extent of the diversification of their methods to collect, aggregate, transfer and use funds; and the extent to which the funds may be used against Canadian domestic and international interests. The terrorist financing threat rating results are presented in Chapter 4.

The assessment considered the inherent features of Canada that may be exploited by threat actors for illicit purposes (e.g., geography, economy, demographics). Against this, the inherent money laundering and terrorist financing vulnerabilities were assessed for 33 economic sectors and products. The areas were assessed against five rating criteria, namely the inherent characteristics of the assessed areas (size, complexity, accessibility and integration); the nature and extent of the vulnerable products and services; the business relationship with its clients; geographic reach (extent of activity with high-risk jurisdictions and locations of concern); and the degree of anonymity and complexity afforded by the delivery channels. Canada’s inherent features and sector and product vulnerability assessment results are presented in Chapter 5.

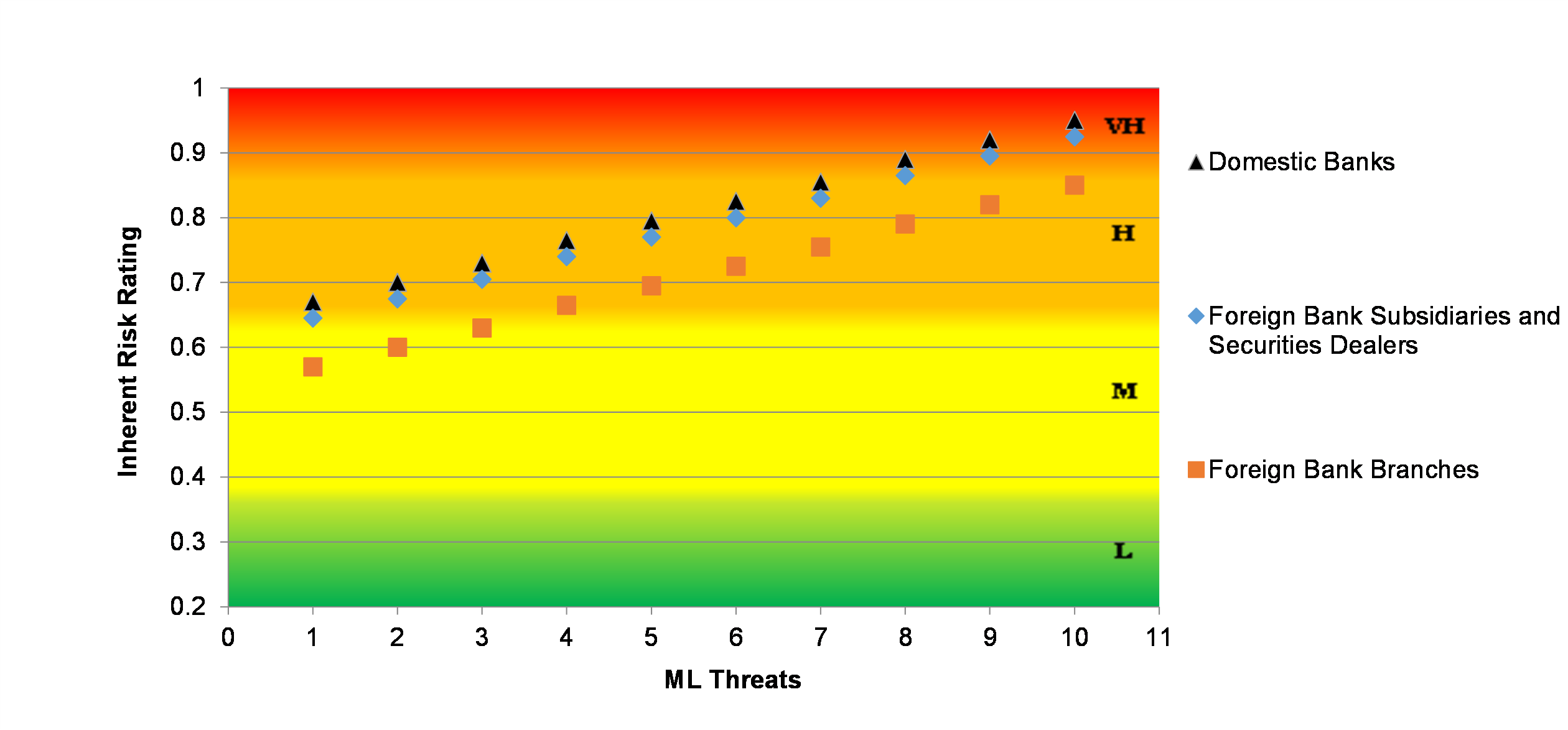

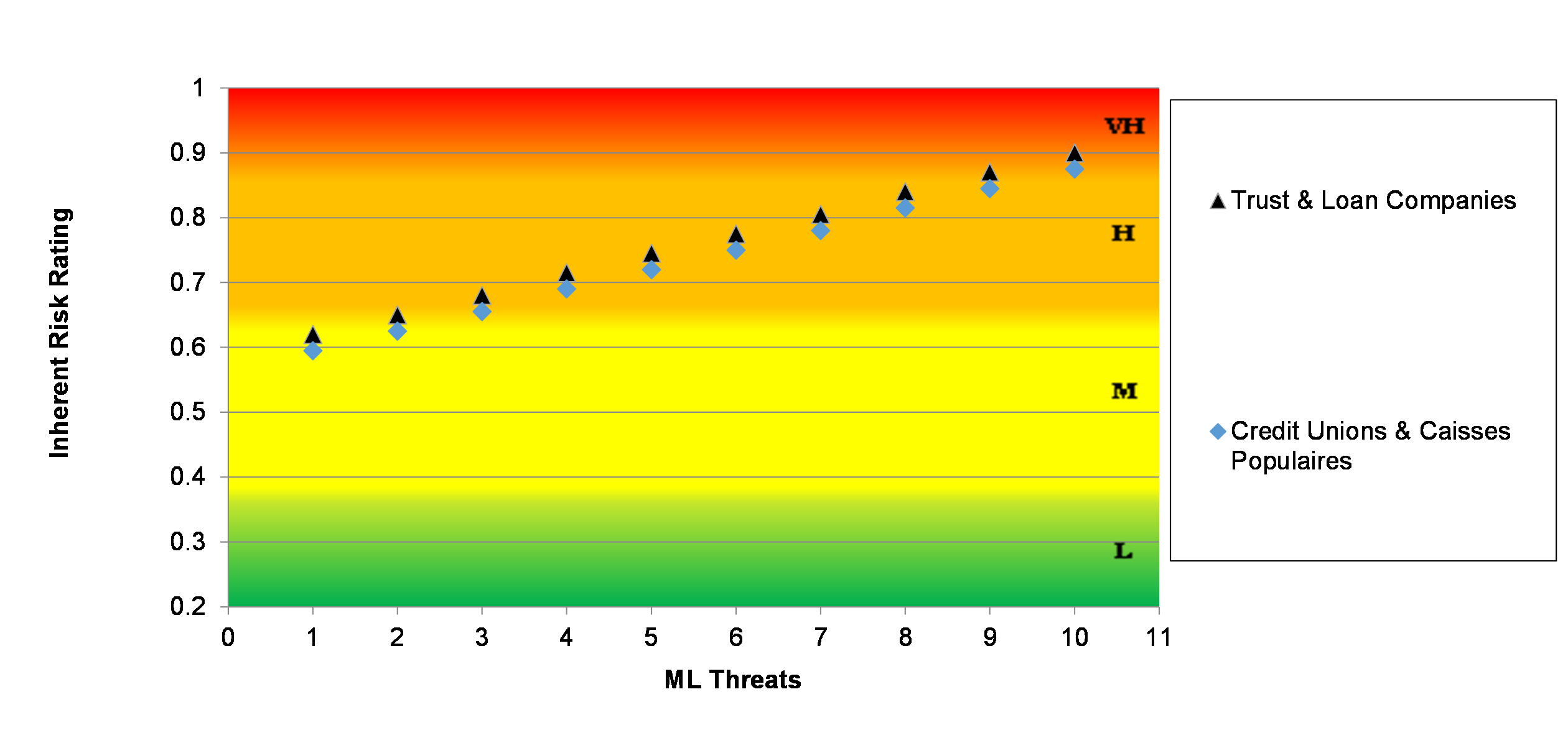

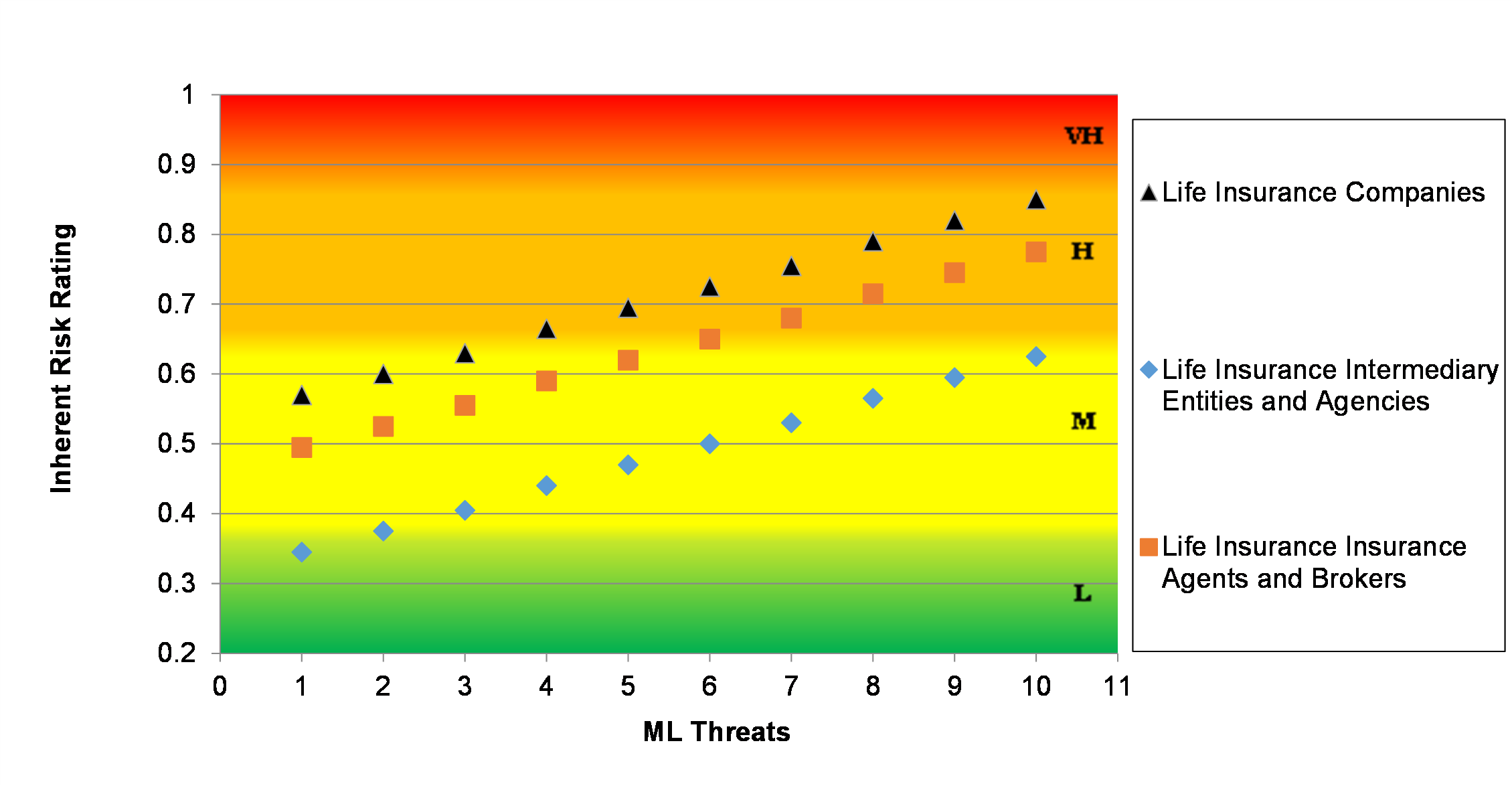

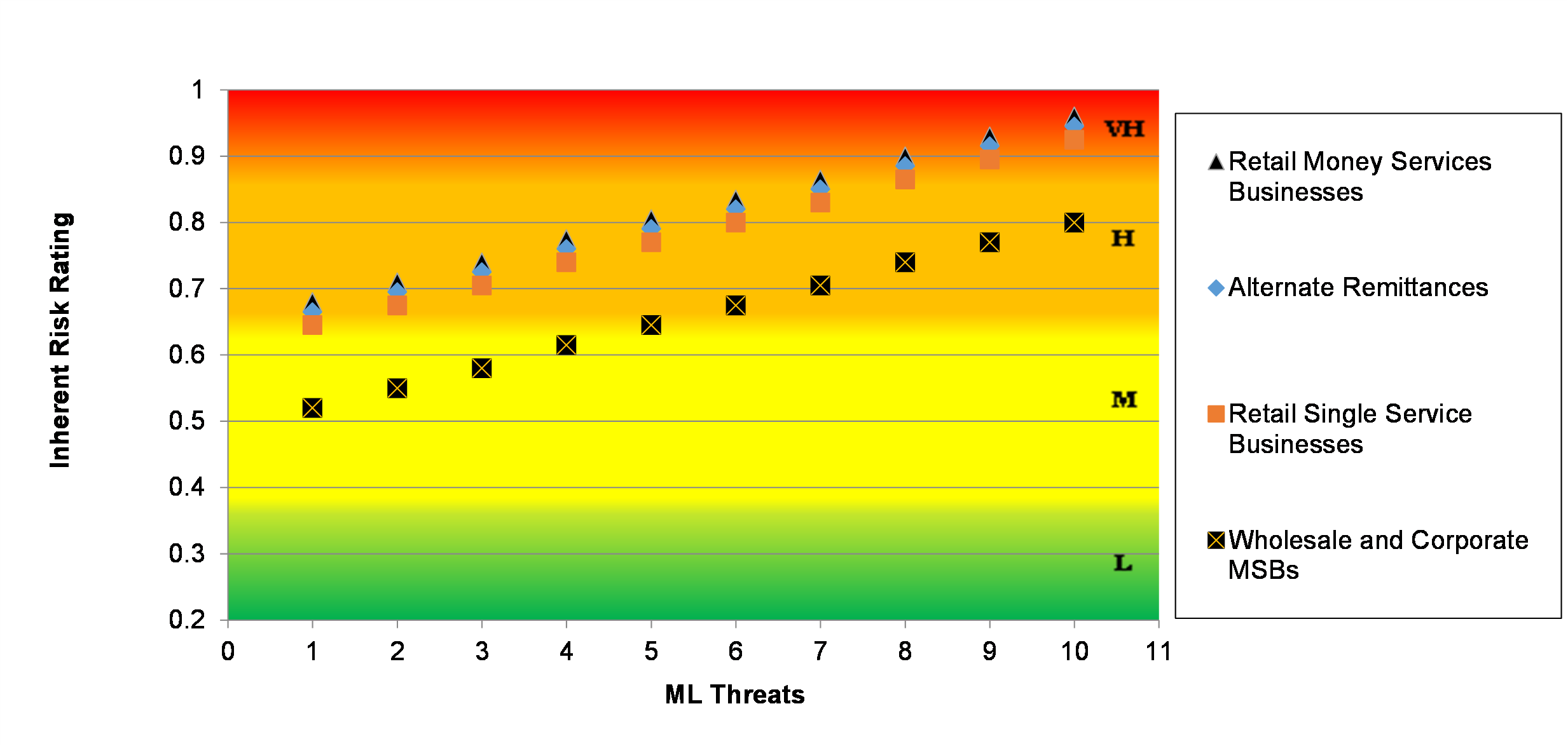

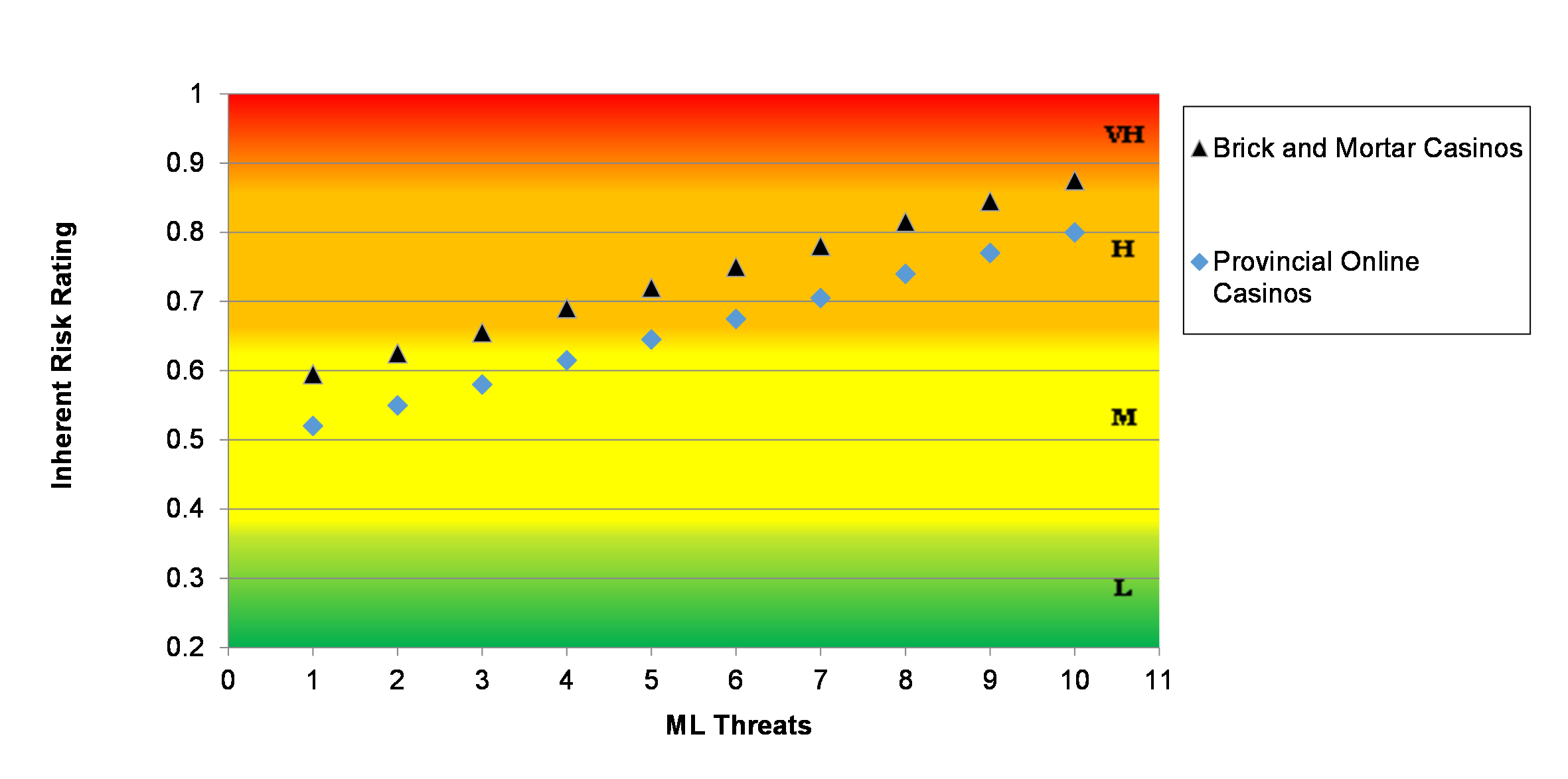

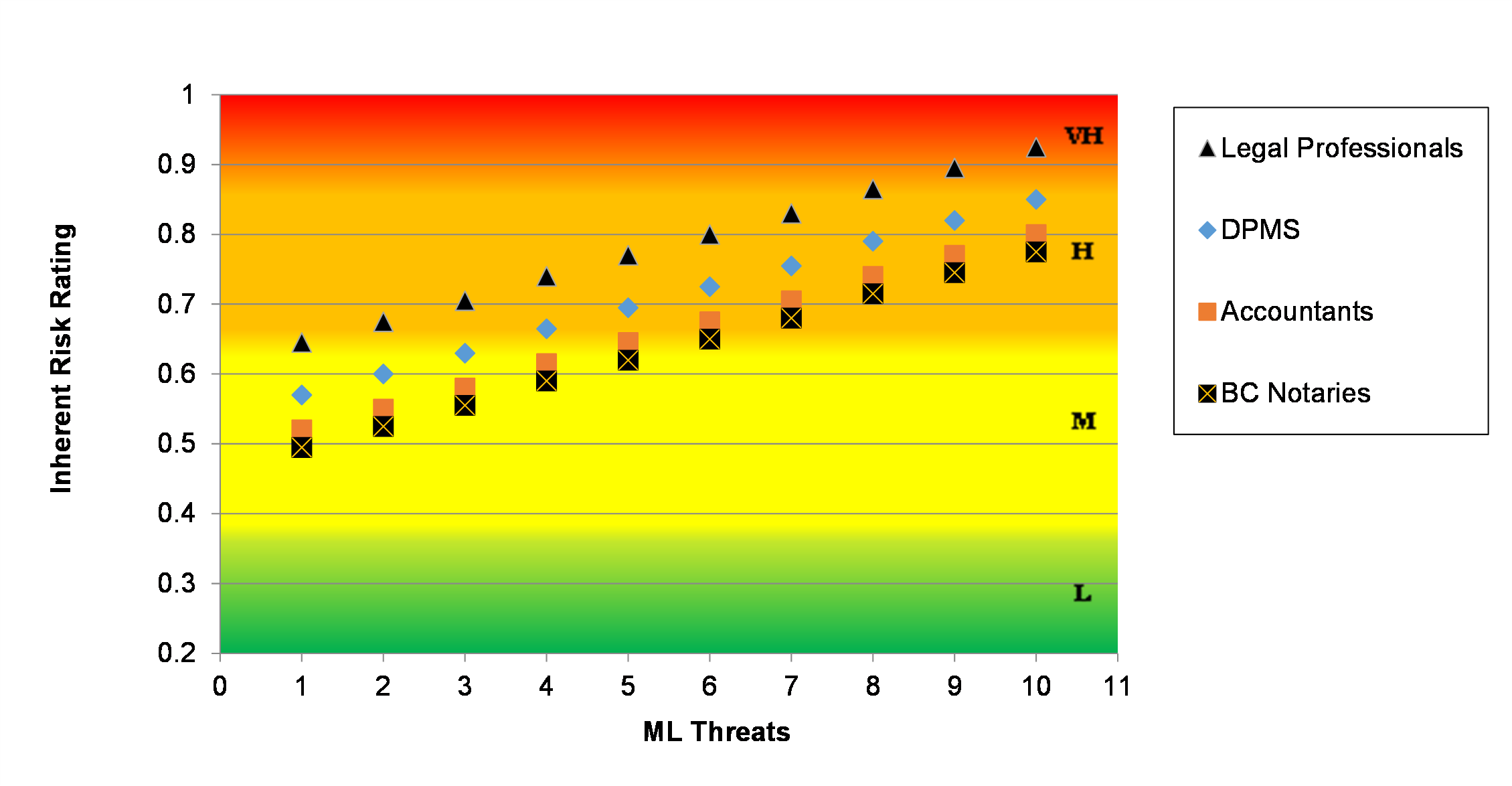

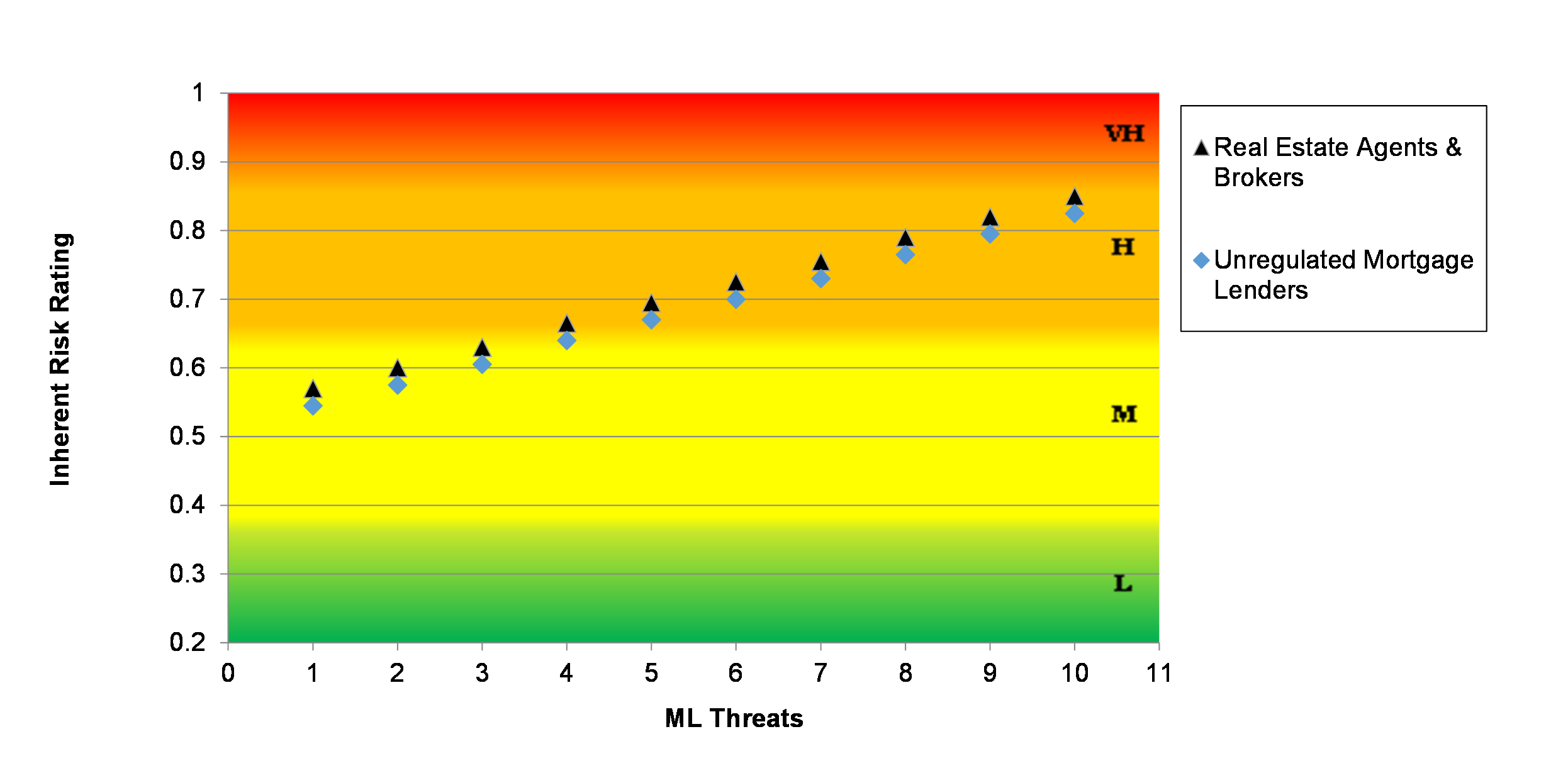

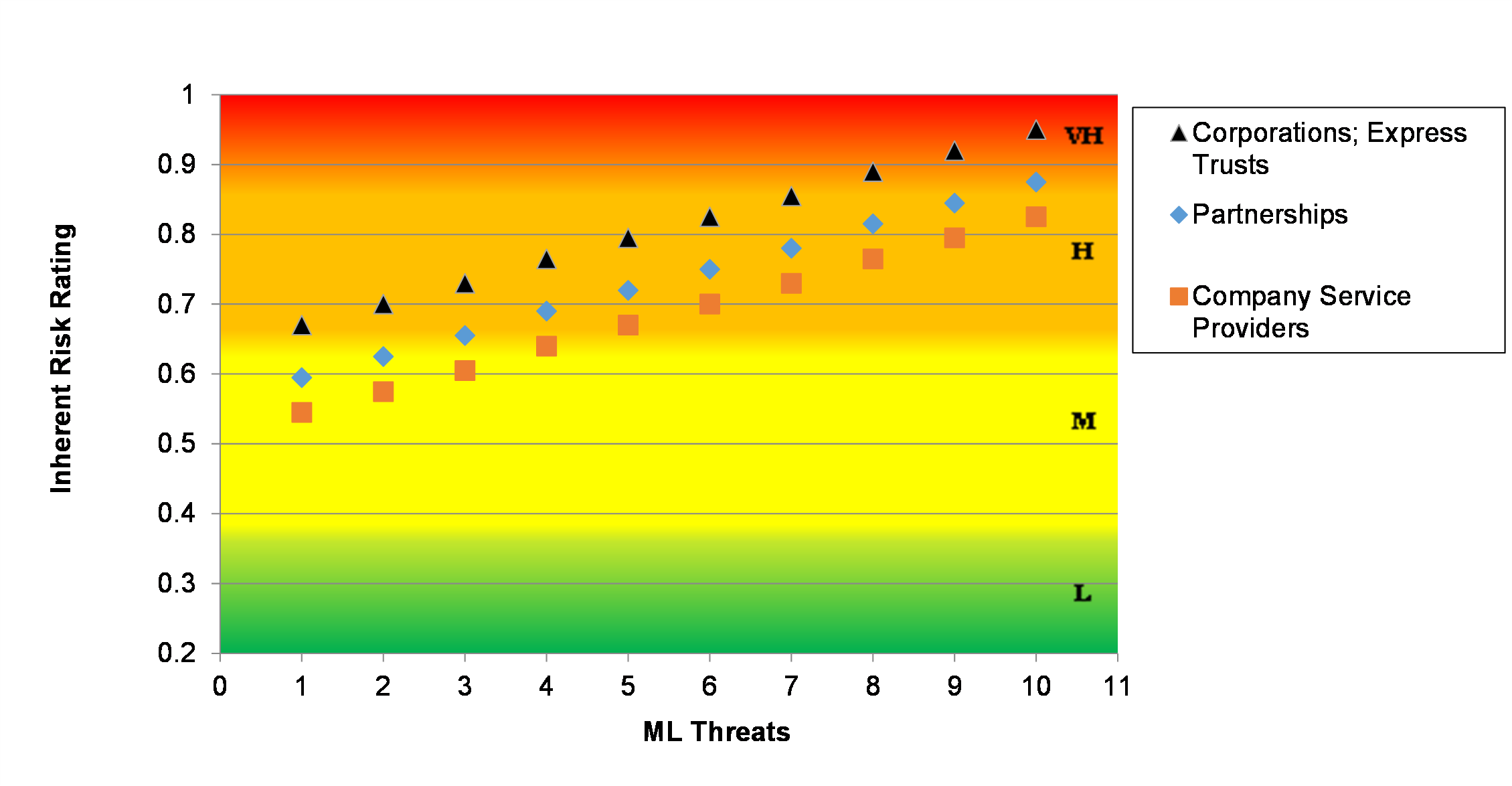

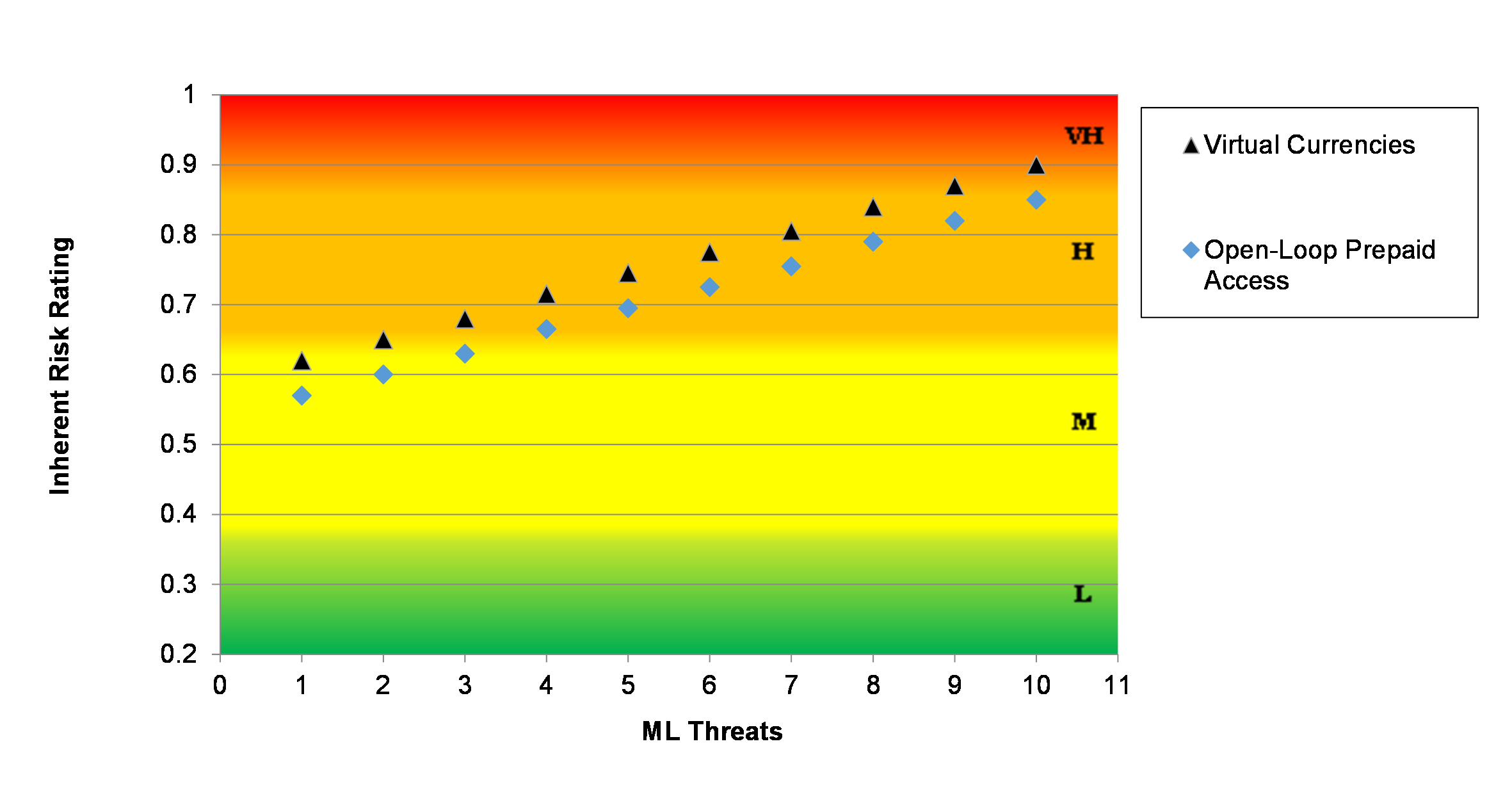

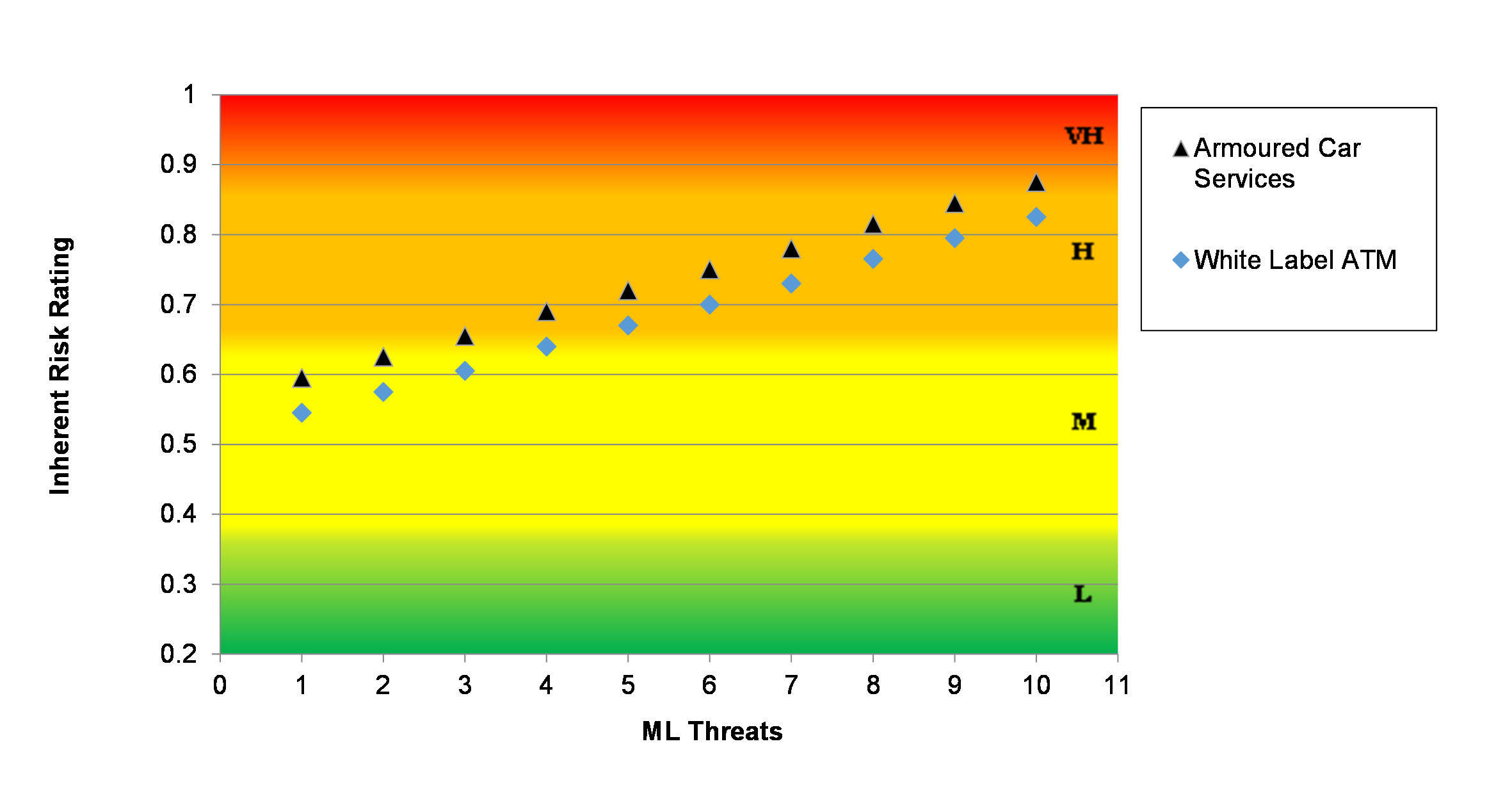

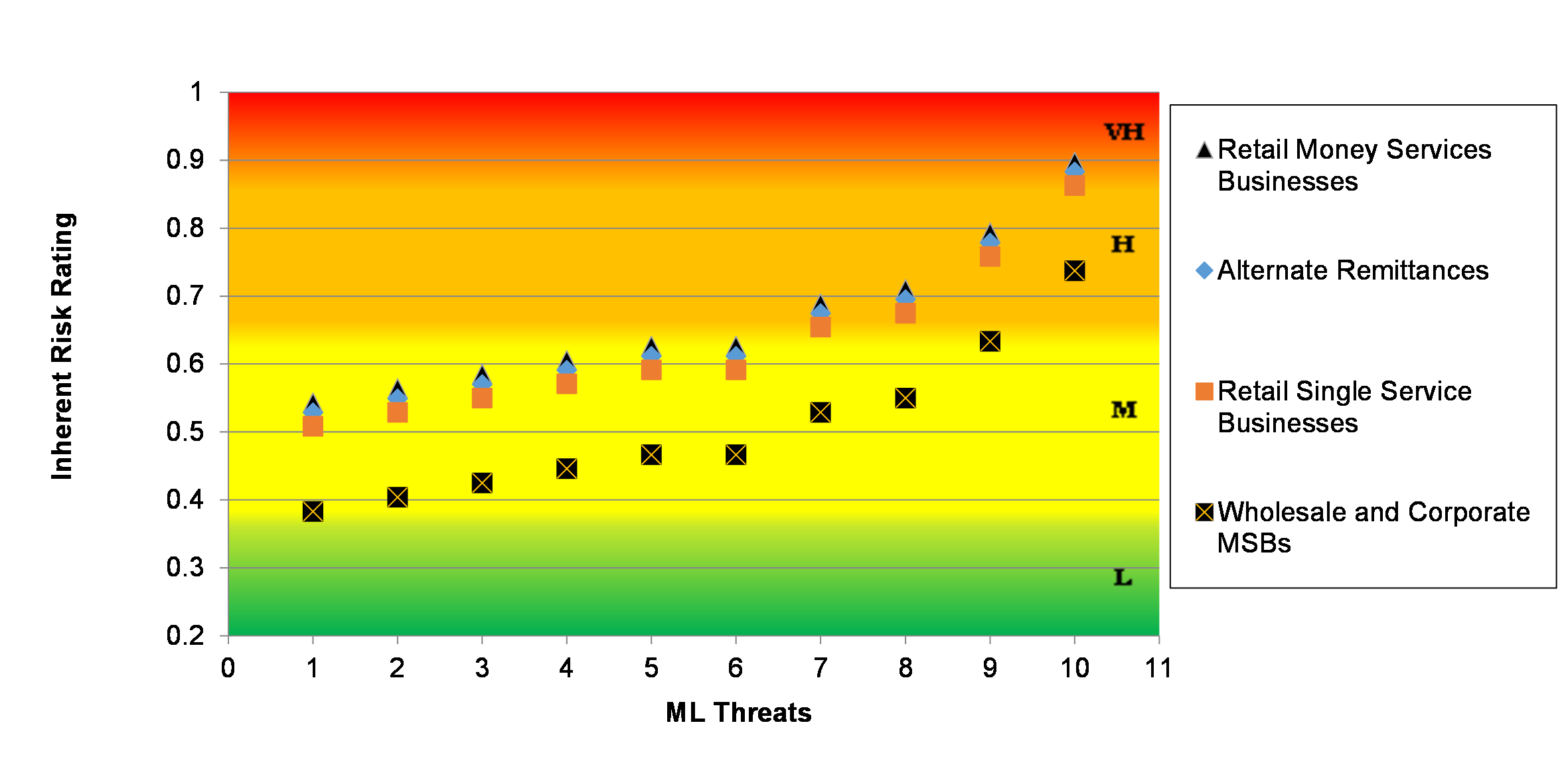

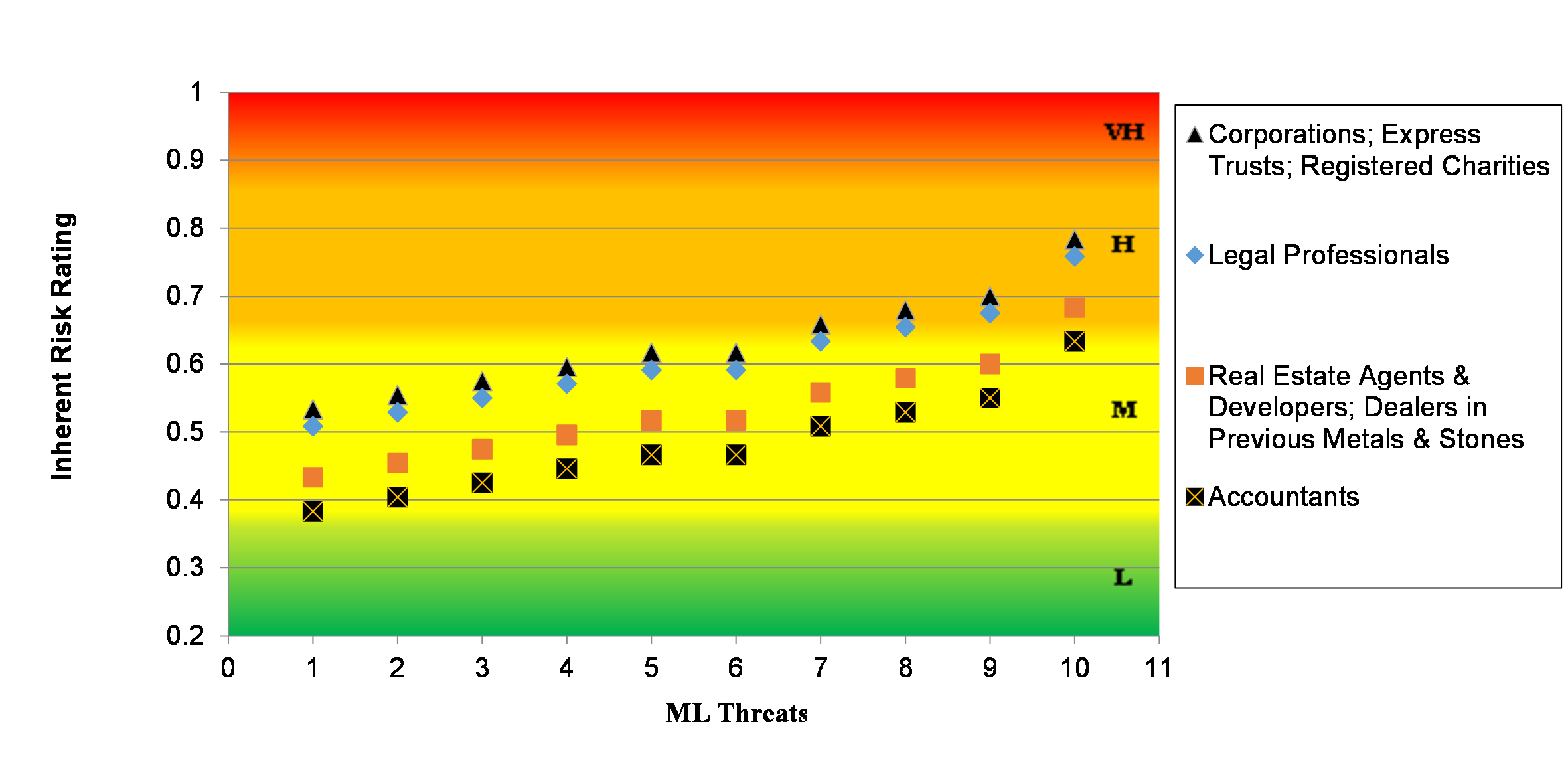

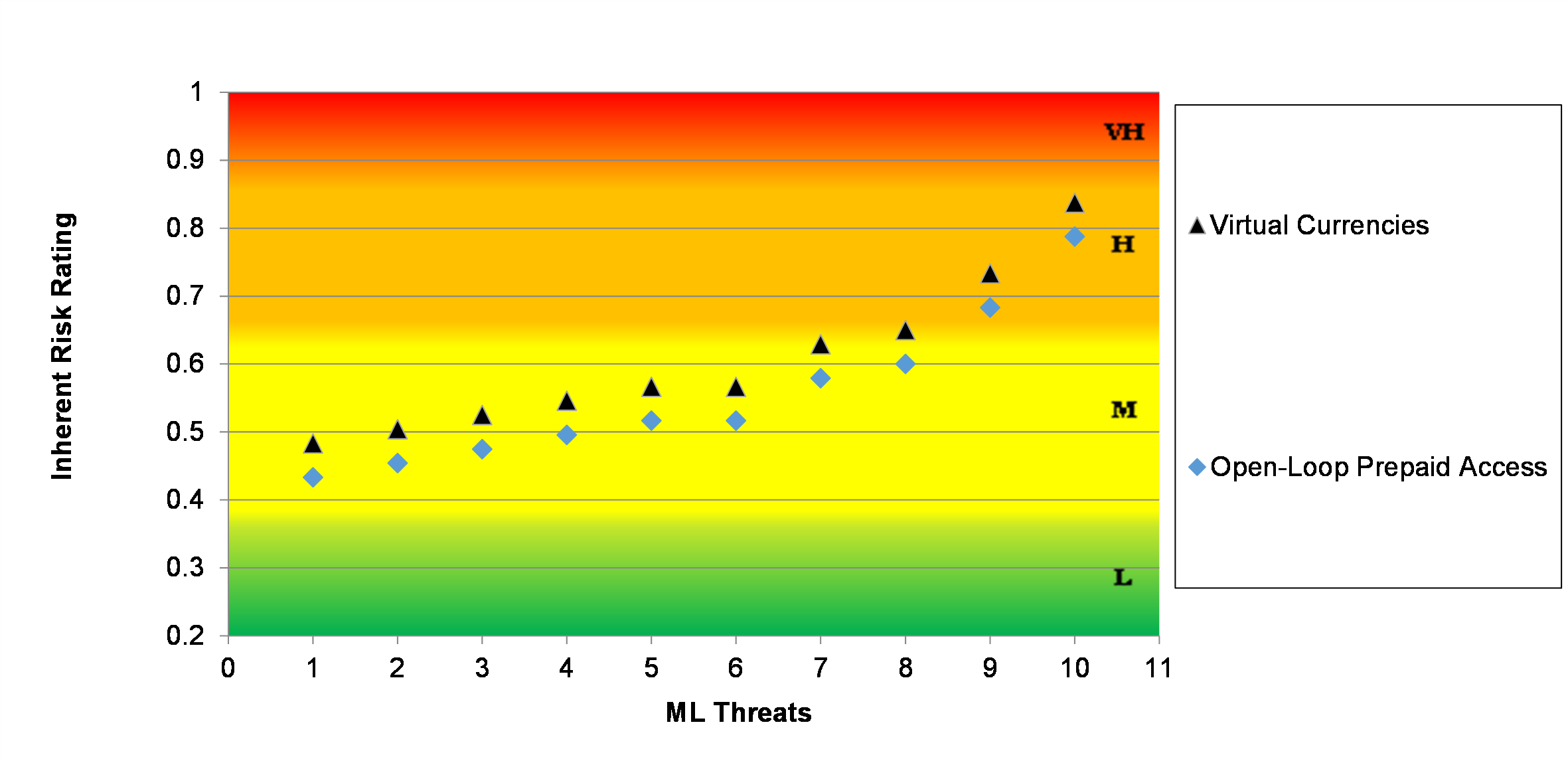

Assessing the Inherent ML/TF Risks

The inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks were assessed based on the likelihood of money laundering or terrorist financing occurring while considering the consequences of such events. The likelihood of the money laundering or terrorist financing was assessed by matching the money laundering and terrorist financing threats with the inherently vulnerable sectors and products through the money laundering and terrorist financing methods and techniques that are used by threat actors to exploit these sectors and products. Inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risk scenarios were created from these judgements and used to plot the inherent risk results by sector, product or service in a number of illustrative charts. This presentation allows one to compare the different levels of exposure of various sectors and products to inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks in CanadaFootnote 22 The results are presented in Chapter 6.

Risk Assessment and Mitigation Framework

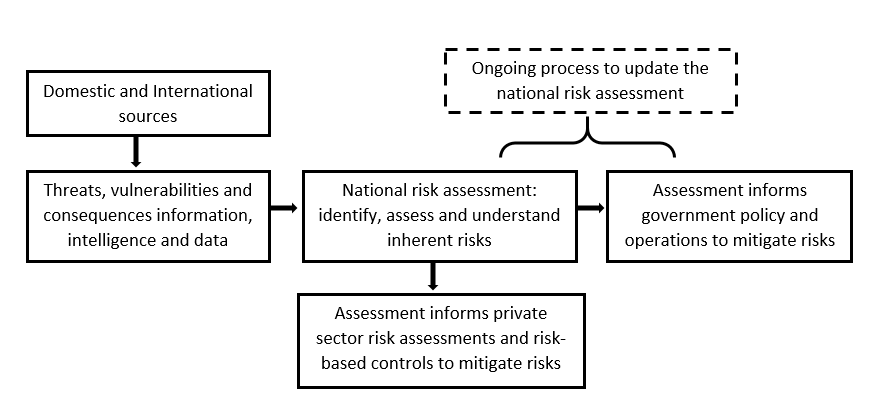

The inherent risk assessment and its methodology should be viewed as one core element of a larger framework to support an ongoing process to identify, assess and mitigate money laundering and terrorist financing risks in Canada. This framework is summarized below in Chart 2.

Canada's ML/TF Risk Assessment Framework

Chapter 3: Assessment of Money Laundering Threats

Overview

The money laundering threat assessment indicates that there is a broad range of profit-oriented crime conducted by a variety of threat actors in Canada. This criminal activity generates billions of dollars in proceeds of crime annually that might be laundered.

Threat actors who perpetrate profit-oriented crime in Canada range from unsophisticated, criminally-inclined individuals, including petty criminals and street gang members, to criminalized professionalsFootnote 23 and OCGs.Footnote 24 An OCG can be defined as a structured group of three or more persons acting in concert with the aim of committing criminal activities, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit. In 2020, the Criminal Intelligence Service Canada assessed 506 OCGs and believes that there could be more than 2000 operating in Canada. The majority of Canada-based OCGs are not considered transnational OCGs, even though many have international links and associations. While some of these domestic OCGs represent significant money laundering threats, transnational OCGs with a presence or ties to Canada are generally the most threatening both in terms of generating the most proceeds of crime and in the intensity of efforts to launder the proceeds.Footnote 25 The most powerful transnational OCGs in Canada, consist of factions with ties to Italy, Eastern Europe, Latin America and Asia, as well as certain Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs, are involved in multiple lines of profit-oriented crime and have the infrastructure and network to launder large amounts of proceeds of crime on an ongoing basis through multiple sectors using a diverse set of methods to avoid detection and disruption. These OCGs have strong networks and strategic relationships with other criminal organizations both domestically and internationally (e.g., transnational drug cartels).

Transnational OCGs appear to frequently rely on professional money launderers to establish and administer schemes to launder the proceeds emanating from their criminal activities. Large-scale, sophisticated money laundering operations rarely take place in Canada without the employ of professional money launderers. The nexus between transnational OCGs and professional money launderers is a key money laundering threat in Canada. In addition to professional money launderers, unwitting and witting facilitators appear to continue to play a key role in supporting the perpetration of profit-oriented crime and the laundering of criminal proceeds. The corruption of individuals and the infiltration of private and public institutions is also a notable concern as it establishes the conditions to foster money laundering and other criminal activity.

The conduct of larger scale profit-oriented crimes often have a significant international dimension and tend to be supported by transnational distribution networks. These networks exhibit a high level of sophistication and capability in moving illicit goods into (destination), out of (source), or through (transit) Canada, including stolen goods, counterfeit products, illicit drugs, illicit firearms, wildlife and people. Mapped against this sophisticated illicit global supply chain appears to be a correspondingly sophisticated flow of illicit funds and a network to launder these funds. Some threat actors appear to have the sophistication and capability to exploit the global trade and financial systems to clandestinely deal in the transnational trafficking of illicit goods and launder illicit proceeds. This capability includes having criminal associates in legitimate positions of employment in ports of entry, or controlling employees using methods like bribery, blackmail or extortion, in order to have insiders facilitate the movement of illicit goods and proceeds into and out of Canada. These threats also appear to have the ability to exploit the AML/ATF weaknesses of foreign countries or situations of unrest or conflicts occurring in foreign countries to facilitate money laundering and other criminal activities.

Discussion of the Money Laundering Threat Assessment Results

Experts assessed the money laundering threat for 23 profit-oriented crimes and third-party money laundering using the following criteria:

- Sophistication: the extent to which the threat actors have the knowledge, skills and expertise to launder criminal proceeds and avoid detection by authorities.

- Capability: the extent to which the threat actors have the resources and network to launder criminal proceeds (e.g., access to facilitators, links to organized crime).

- Scope: the extent to which threat actors are using financial institutions and other sectors to launder criminal proceeds.

- Proceeds of Crime: the magnitude of the estimated dollar value of the proceeds of crime being generated annually from the profit-oriented crime.

As presented in Table 1, eight profit-oriented crimes and third-party money laundering were rated as a very high money laundering threat, ten were rated high, five were rated medium, and none were rated low.

Table 1: Overall Money Laundering Threat Rating Results

Very High Threat Rating

- Capital Markets Fraud

- Commercial (Trade) Fraud

- Corruption and Bribery

- Illegal Gambling

- Illicit Drug Trafficking

- Mass Marketing Fraud

- Mortgage Fraud

- Third-Party Money Laundering

High Threat Rating

- Currency Counterfeiting

- Counterfeiting and Piracy

- Human Smuggling

- Human Trafficking

- Identity Fraud

- Payment Card Fraud

- Pollution Crime

- Robbery and Theft

- Tax Evasion/Tax Fraud

- Tobacco Smuggling and Trafficking

Medium Threat Rating

- Extortion

- Firearms Smuggling and Trafficking

- Illegal Fishing

- Loan Sharking

- Wildlife Crime

Very High Money Laundering Threat

ML Threat from Capital Markets Fraud: Securities fraud, including investment misrepresentation and other forms of capital markets fraud-related misconduct, such as insider trading and market manipulation, continues to occur in Canada. When this fraud occurs, it frequently involves large dollar amounts and a significant number of investors. While fewer Canadians are being approached with investment fraud (18 per cent in 2017, down from 22 per cent in 2016 and 27 per cent in 2012), just as many Canadians are falling victim to investment fraud with the level of fraud victimization remaining steady at 4 per cent.Footnote 26 Although it is challenging to be definitive on the actual amount of reported losses, capital markets fraud is a rich source of proceeds of crime. Most of the large-scale securities frauds in Canada have been perpetrated by criminalized professionals, who have (or purport to have) professional credentials and financial expertise.

Perpetrating capital markets fraud, especially the larger, more elaborate national and international schemes (such as Ponzi schemes), requires significant knowledge and expertise and, often, access to a network of witting or unwitting facilitators to help orchestrate and perpetuate the fraud. Alongside the sophisticated fraudulent schemes, there are sophisticated money laundering schemes designed to integrate and legitimize the fraud-related proceeds into the financial system. Money laundering schemes in this context would involve a range of sectors and methods, including shell or front companies, electronic funds transfers (EFTs), structuring and/or smurfing depositsFootnote 27 and nominees. However, an emerging trend that has been observed is the presence of Internet scammers in capital markets fraud, using the Internet and other high technology (as well the public’s interest in emerging technology, such as blockchain) to commit capital markets fraud.

ML Threat from Commercial (Trade) Fraud: Commercial trade fraud is unique in that it is a designated offence for money laundering and terrorist financing as well as a money laundering mechanism itself. The transnational OCGs and the terrorist actors and networks that use commercial fraud to launder are very sophisticated and capable, with the knowledge, expertise and international relationships to manipulate multiple trade chains, customs processes and financing mechanisms, often operating under the cover of front or legitimate companies. This is known as trade-based money laundering (TBML).

A high degree of sophistication and capability in terms of conducting the commercial fraud and laundering proceeds of crime continues to be observed. The threat actors in this space appear to use multiple sectors to launder proceeds both in Canada and internationally. Actors are suspected of using domestic and foreign front and shell companies, to commingle illicit funds within legitimate businesses (both cash and non-cash intensive businesses), and to use third-party money launderers, including professional money launderers. It has been observed that criminal organizations will manipulate customs and shipping documents and engage in fraudulent international trading activity with colluding foreign importer/exporters. The trade in misdescribed goods allows illicit finances to flow to the jurisdiction of choice in the form of payment for the goods in question with the importer/exporter paying inflated amounts to move illicit proceeds. Further, it has been observed that TBML schemes reveal a preference for goods which are either subject to spoilage (increasing the incentive by customs authorities to minimize examination of goods), difficult to physically examine, or where average and mean unit prices for goods can be difficult to establish as a result of variable values, making misdescription more difficult to detect. Recent law enforcement reports indicate an increased observance of use of customs fraud techniques for TBML to and from Canada, which may have been exacerbated in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

ML Threat from Corruption, Collusion and Bribery: Corruption and bribery in Canada comes in many different forms, ranging from small-scale bribe paying activity to obtain an advantage or benefit to large-scale schemes aimed at illegally obtaining lucrative public contracts. Public contracts can also be obtained illegally through collusive schemes that do not implicate the payment of a bribe. Although these schemes do not generate proceeds in the form of the payment of a bribe, they still generate illicit funds, e.g., through inflated procurement costs incurred. Direct control of legitimate business by OCGs or resorting to threats and intimidation to coerce other entrepreneurs are typically used to conduct these criminal activities.

The money laundering threat from corruption, collusion and bribery is rated very high principally due to the size of the public procurement sector and the opportunities this presents to illegally obtain high-value contracts. In addition to corrupt activities carried out domestically, some Canadian companies have also been implicated in paying of bribes to foreign officials to advance their company’s business interests. OCGs with the ability to infiltrate the public procurement process and the legitimate economy have the sophistication and capability to launder large amounts of illicit funds, using a variety of money laundering methods and techniques, including banks, MSBs, high-end goods, investments and front companies. Cases have especially illustrated how networks and layers of shell companies have been used for the payment of bribes and corruption of foreign officials. Lawyers, accountants, professional money launderers and public officials may also be used to facilitate the laundering of corruption-related proceeds.

ML Threat from Illegal Gambling: This threat is being upgraded to Very High to reflect heightened law enforcement awareness of the known extent of the capabilities, scope and proceeds of crime associated with these activities. Illegal gambling in Canada continues to comprise private betting and gaming houses, unregulated video gaming and lottery machines, and unregulated online gambling.Footnote 28 Organized crime is the major provider of illegal gambling opportunities in Canada, although there are some smaller operators. The illegal gambling market appears to be small in terms of the numbers of threat actors involved, but it is suspected to be highly profitable for those involved. Traditional bookmaking betting activities use pyramid-style schemes to protect more senior members of the pyramid, with bookmakers accepting only cash to benefit from its anonymity.

OCGs also continue to run illegal gambling sites in jurisdictions where online gambling is legal or enforcement is lacking. OCGs operating in this space continue to have the sophistication and capability to launder proceeds of crime through a variety of sectors and methods. The main forms of illegal gambling proceeds are cash and possibly high value goods (in instances where gamblers may have run out of cash). Illegal gambling can further be a laundering technique in itself through the lending of proceeds of crime to gamblers. Law enforcement reports that closures of brick and mortar casinos due to the COVID-19 pandemic have led to an increase in underground illicit gaming and related money laundering activities.

According to the RCMP, illegal gambling is a key source of income for organized crime networks, with Criminal Intelligence Service Canada reporting that these proceeds are used to fund other criminal activity including drug trafficking and money laundering. OCGs may further be collaborating in sharing some overhead costs involved in the creation and upkeep of illegal online gambling websites, hosting onshore or offshore gambling servers as well as providing initial start-up capital.Footnote 29

ML Threat from Illicit Drug Trafficking: Illicit drug trafficking remains the largest criminal market in Canada. Cannabis (post-legalization), cocaine, methamphetamines and heroin each comprise a significant share of this market, with fentanyl and its analogues rising in prominence. Although numerous threat actors engage in drug trafficking, transnational OCGs remain the most threatening and powerful actors, exhibiting very high levels of sophistication, capability and scope in their money laundering activities. They are often connected to other OCGs, and multiple organized networks at both the domestic and international levels to launder drug-related proceeds. OCGs continue to have access to professional money launderers, facilitators (such as money mules and nominees), and often have control over a number of companies (front and/or legitimate) as part of their money laundering operations. OCGs use a large number of money laundering methods, including the use of multiple sectors, commingling of illicit funds within legitimate businesses, domestic and foreign front and shell companies, bulk cash smuggling, TBML, and prepaid cards. Despite the prevalence of cash transactions for laundering drug proceeds, the use of virtual currencies to procure drugs via the dark web is becoming more common. With border closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic, traditional cash-courier money laundering techniques have been disrupted.Footnote 30 It is not yet clear if OCGs will seek permanent alternative methods such as wire transfers or return to traditional techniques once borders reopen.

ML Threat from Mass Marketing Fraud (MMF): MMF remains prevalent in Canada and the scams associated with MMF have been growing in frequency and sophistication over time. Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, Calgary and Edmonton continue to be considered the main bases of operation for MMF schemes. Common types of scams in Canada include extortion scams, phishing scams, service scams, and cyber scams. The CRA tax scam is an example of extortion scam. Fraudsters pretending to be the CRA have been calling consumers and telling them they owe money from a past tax return. The consumers are told they will incur additional fees, face jail time or be deported if they fail to pay the sum — by wire transfer, pre-paid credit cards, gift cards or bitcoin. The CRA scam alone has resulted in reported losses of more than $17.2 million in Canada between 2014 and 2019.Another rising trend is continuity scams, which involve a “free” trial or product offered online, where the victim must cover the cost of shipping via credit card and is subsequently charged hidden monthly fees. There has been an 859 per cent increase in continuity scams over the past two years. Another emerging trend is fraudsters impersonating banks or credit card providers to obtain financial information or money transfers abroad via MSBs.

While some Canada-based OCGs are involved, foreign actors, sometimes using Canadian associates for payment forwarding, are major threats in this activity. They use a range of money laundering methods and techniques, including smurfing, structuring, the use of nominees and money mules, shell companies, MSBs, informal banking system and front companies. Although reported losses have averaged at about $74 million annually from 2014 to 2017,Footnote 31 the actual losses are viewed as being much higher, in the hundreds of millions of dollars annually, given that MMF is generally under-reported by victims. The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an observed increase in online schemes and pandemic-related fraud, using prepaid cards and virtual currencies.

ML Threat from Mortgage Fraud: Mortgage fraud is suspected to have increased since the first publication of this report in 2015. It continues to occur across Canada, although it is most prevalent in large urban areas in Quebec, Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia, especially the Greater Vancouver and Toronto areas. Some forms of mortgage fraud are undertaken by persons misrepresenting their personal information such as their income in order to qualify for a loan they would not obtain otherwise. This is often referred to as fraud for housing as the borrower try to access property ownership and has no intent to default on the loan. However other types of mortgage fraud schemes are also undertaken by OCGs to facilitate another criminal activity (e.g., illicit drug production and distribution, money laundering) or directly for profit by defrauding a lender.

Rapid escalation of housing prices in certain areas of Canada in recent years have provided new lucrative opportunities for mortgage fraud (e.g., by making overvaluation schemes easier) which may have significantly increased the attractiveness of this type of fraud for OCGs. OCGs conducting mortgage fraud schemes are sophisticated in terms of the fraud and the associated money laundering activity. To orchestrate the fraud, they often seek the assistance of witting or unwitting professionals in the real estate sector, including agents, brokers, appraisers and lawyers. OCGs also frequently use straw buyers as nominees and misrepresent information to obfuscate the real identify of the borrower. As a result, discrepancies that could originally appear to a lender as fraud for housing may in fact involve more egregious criminal activities by OCGs which are in fact using a straw buyer to obfuscate the real party to the transaction. To launder mortgage-fraud related proceeds, professional money launderers can use criminally inclined real estate professionals, including real estate lawyers. OCGs involved in mortgage fraud also appear to launder funds through banks, MSBs, legitimate businesses and trust accounts. Victims of mortgage fraud, which can include Canadian homeowners and lending institutions, can incur significant financial losses.

ML Threat from Third-Party Launderers: Large-scale and sophisticated money laundering operations in Canada, notably those connected to transnational OCGs, frequently involve third-party money launderers, namely professional money launderers, nominees or money mules.Footnote 32 Of the three, professional money launderers pose the greatest threat both in terms of the level of funds and sophistication employed in laundering domestically generated proceeds of crime as well as laundering foreign-generated proceeds through Canada (and through its financial institutions). Professional money launderers specialize in laundering proceeds of crime and generally offer their services to criminals for a fee and are usually not associated with the underlying criminal activity. These individuals are in the business of laundering large sums of money and by their very nature have the sophistication and capability to support complex, sustainable and long-term money laundering operations. As a group, they use many different methods and techniques, often involving the use of multiple shell businesses, unregulated MSBs and nominees to conduct multiple layers of transactions to obfuscate the trail and impede the ability to link funds to its criminal origins. Professional money launderers are of principal concern since they are often the masterminds behind large-scale money laundering schemes and are frequently used by the most powerful transnational OCGs in Canada. Nominees and money mules are less of a threat, but are nonetheless important because they may be critical in carrying out or facilitating money laundering schemes, both large and small.

High Money Laundering Threats

ML Threat from Counterfeiting and Piracy: This threat is being downgraded to High to reflect more recent intelligence on the relative known prevalence of these activities in the Canadian environment. A broad prevalence of counterfeit and pirated products in Canada has continued to persist. China is the primary source of counterfeit products imported into Canada, with Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver providing entry points. Foreign and potentially domestic OCGs appear to have established links and have tapped into illicit global distribution channels, allowing them to bring increasingly more counterfeit products into Canada. Available information indicates that involved actors are sophisticated and capable in terms of laundering the proceeds from counterfeit goods. These capabilities would continue to be fundamental to the sustainability of the operations given the large numbers of participants throughout the global supply chain.

ML Threat from Currency Counterfeiting: The large-scale production of Canadian counterfeit currency continues to be primarily undertaken by OCGs based in major cities in Canada, with a target on the new polymer series of bank notes. This is a proceeds-generating crime, but OCGs also launder the proceeds generated from currency counterfeiting. In 2019, the value of passed counterfeit notes was approximately $1.6 million, which has remained relatively consistent between 2015 and 2020. OCGs continue to conduct currency counterfeiting alongside other profit-oriented criminal activities. OCGs that produce and distribute high-quality counterfeit currency are suspected to exhibit a high level of sophistication and capability in terms of the methods used to launder the proceeds arising from currency counterfeiting. OCGs have the network and infrastructure in place to successfully launder, through a number of sectors, predominantly cash proceeds arising not only from currency counterfeiting but also from their other criminal activities.

ML Threat from Human Smuggling: Canada is a target for increasingly sophisticated global human smuggling networks. Human smuggling continues to be carried out primarily by a small number of OCGs that are well-established, having developed the sophistication and capability to smuggle humans for profit across multiple borders, which requires a high degree of organization, planning and international connections. OCGs in this space continue to be very sophisticated and capable in terms of laundering the proceeds of crime arising from human smuggling. A review of recent suspected money laundering cases largely related to human smuggling reinforced that OCGs may use a variety of sectors and methods to launder the proceeds, including front companies, legitimate businesses, banks, MSBs and casinos. Changes in technology, such as the use of cryptocurrencies, cheap labour demand, and the ease of money movement may be facilitating human smuggling services.

ML Threat from Human Trafficking: Canada continues to be a source, transit, and destination country for human trafficking. Police services in Canada have reported 1,708 incidents of human trafficking between 2009 and 2020. Between 2008/2009 and 2017/2018, there were 582 completed cases in adult criminal courts that involved at least one charge of human trafficking. Domestic human trafficking for sexual exploitation is the most common form of human trafficking in Canada.Footnote 33 Sex trafficking is largely perpetrated by criminally inclined individuals, who recruit and traffic domestically and, to a lesser extent, OCGs, some of which only recruit and traffic domestically, while others recruit and traffic domestically and internationally. Criminally inclined individuals are not believed to exhibit significant levels of sophistication or capability in terms of laundering their sex trafficking-related proceeds. It is suspected that most of their activity would center on laundering mostly cash proceeds for immediate personal use, leveraging a very limited or non-existent network, and using a limited number of sectors and methods. The OCGs that conduct sex trafficking and generate significant proceeds are suspected to use established money laundering infrastructure to launder the proceeds. Some OCGs, although less sophisticated in terms of money laundering, are nonetheless more capable because they may have access to venues to facilitate money laundering (e.g., strip clubs and massage parlors) as well as victims that can be used as nominees for deposits and wire transfers.

ML Threat from Identity Theft and Fraud ("Identity Crime"): Identity crime continues to be prevalent in Canada and it is a concern given that stolen identities are often used to support the conduct of other criminal activities. In 2018, police services across Canada reported 19,584 incidents of identity theft and fraud, representing a 37 per cent increase over 2015. These can be conducted by individual criminals, foreign-based OCGs, and Canadian OCGs. The OCGs conducting identity crime are well-established, resilient and have well-developed domestic and international networks. They are also associated with drug trafficking, human smuggling and counterfeiting currency. It is suspected that these OCGs use multiple methods and sectors to launder the funds. Identity crime itself can support money laundering by providing individuals with fake credentials to subvert customer due diligence safeguards. In 2017, Canadians reported over $11 million in losses to identity crime.Footnote 34 Identity theft also facilitates the conduct of other criminal activities that generate significant proceeds of crime.

ML Threat from Payment Card Fraud: Between 2014-2019, reported losses from credit card fraud increased significantly while debit card fraud over the same period decreased (largely due to technology advancements). Payment card fraud continues to be a profitable market as reinforced by the fact that in 2013, Canadians reported close to $500 million annually in payment card fraud-related losses which, by 2016, had increased to $700 million annually.Footnote 35 “Card not present”Footnote 36 fraud comprises the largest value of all categories of credit card fraud in Canada, followed by credit card counterfeiting.Footnote 37 As with other frauds, OCGs, are heavily involved, with 24 domestic OCGs reported to be involved with payment card fraud in 2017 and possibly many more predominantly operating abroad. Organized crime involvement in payment card fraud can involve card thefts, fraudulent card applications, fake deposits, skimming or card-not-present fraud. In large part, the OCGs in this space are sophisticated and have specialized technological knowledge in committing payment card fraud. This is further reflected by high levels of sophistication and capability in laundering the proceeds generated. Multiple sectors are suspected to be used to launder payment card-related proceeds, including financial institutions, MSBs and casinos, as well as multiple methods, including structuring bank deposits, smurfing, front companies and the use of nominees and money mules.

ML Threat from Pollution Crime: Pollution crime in Canada continues to come in a variety of forms with some OCGs and companies being involved. Of the forms taken, there is particular concern that OCGs have infiltrated the waste management sector, as owning waste management companies can be an effective vehicle to generate illicit profits, by dumping waste illegally, and to launder proceeds from other criminal activities. OCGs may also be involved in the trafficking of electronic waste and in the importation of counterfeit products that do not meet Canada’s environmental standards (e.g., counterfeit engines). Finally, some private and public companies may be using deceptive practices to undermine emissions schemes and may be dumping or using third parties to dump waste illegally. The OCGs continue to show a high degree of sophistication in the nature of their activities and operations, it is observed that there is a great degree of sophistication, capability and scope in terms of being able to launder the proceeds arising from pollution-related crime.

ML Threat from Robbery and Theft: Smaller scale thefts and robberies continue to be most frequently carried out by opportunistic individuals and petty thieves, while larger scale thefts and robberies are more frequently associated with OCGs, which are heavily involved in motor vehicle, heavy equipment, and cargo theft. There is a long-term downward trend of police-reported vehicle theft and robbery, but the rising proportion of uncovered vehicles suggests that vehicles are stolen by OCGs and then trafficked. The most sophisticated and capable actors continue to be the OCGs that have well-established auto theft networks in Canada, which are used to supply foreign markets with stolen Canadian vehicles. The OCGs that have established auto theft networks in Canada are also suspected to be highly sophisticated and capable from a money laundering perspective.

As with the previous assessment, OCGs appear to use a range of trade-based fraud and related money laundering techniques to disguise the illicit origin of the automobiles as well as a range of methods to move the proceeds back into Canada, including bulk cash smuggling and EFTs. Front companies, shell companies and nominees may be used to obscure the flow of funds back to Canada arising from the illicit sales in other countries. Professional money launderers may be utilized to mastermind money laundering schemes given the large amounts of proceeds generated by these networks and the challenges of laundering proceeds that are generated across multiple jurisdictions.

ML Threat from Tax Evasion: Tax evasion is carried out in many different forms in Canada, with the ultimate objective of underpaying or evading the payment of taxes owing or to unlawfully claim refunds or credits. Although frequently carried out by opportunistic individuals using relatively unsophisticated techniques to misrepresent their tax situation, offshore tax evasion presents an increasingly complex, global and aggressive threat. Some tax preparers – including some accountants, lawyers and financial advisors – provide counsel on how to evade taxes or obtain fraudulent refunds using a variety of different techniques. Tax evasion is also conducted by professional criminals, including OCGs, who may orchestrate tax evasion schemes (e.g., duty or tax refund fraud). Money laundering techniques continue to reflect the sophistication of techniques involved in the tax evasion schemes themselves, while the globalization of financial transactions, increased prevalence of technology and greater access to facilitators increases their capability and sophistication. There is a trend towards using increasingly complex offshore corporate structures and accounts to shift profits to low-tax countries and move funds to accounts that are undeclared to tax authorities.