Evaluation of Defence Intelligence

Table of Contents

Alternate Formats

Assistant Deputy Minister (Review Services)

- ACDI

- Assistant Chief of Defence Intelligence

- ADM(HR-Civ)

- Assistant Deputy Minister (Human Resources – Civilian)

- ADM(IM)

- Assistant Deputy Minister (Information Management)

- ADM(RS)

- Assistant Deputy Minister (Review Services)

- AMOR

- Annual Military Occupation Review

- CA

- Canadian Army

- CAF

- Canadian Armed Forces

- CANSOFCOM

- Canadian Special Operations Forces Command

- CDI

- Chief of Defence Intelligence

- CDS

- Chief of the Defence Staff

- CFD

- Chief of Force Development

- CFINTCOM

- Canadian Forces Intelligence Command

- CFIOG

- Canadian Forces Information Operations Group

- CFRG

- Canadian Forces Recruiting Group

- CFSMI

- Canadian Forces School of Military Intelligence

- CJOC

- Canadian Joint Operations Command

- CMP

- Chief of Military Personnel

- Comd

- Commander

- COS

- Chief of Staff

- DAOD

- Defence Administrative Orders and Directives

- DGIPP

- Director General Intelligence Policy and Partnerships

- DIE

- Defence Intelligence Enterprise

- DIER

- Defence Intelligence Enterprise Renewal

- DIPM

- Director of Intelligence Production Management

- DIR

- Defence Intelligence Review

- DIRC

- Directorate of Intelligence Review and Compliance

- DM

- Deputy Minister

- DND

- Department of National Defence

- DRF

- Departmental Results Framework

- DRP

- Defence Intelligence Officer Recruitment Program

- FA

- Functional Authority

- FD

- Force Development

- FOL

- First Official Language

- FY

- Fiscal Year

- GBA+

- Gender-based Analysis Plus

- GC

- Government of Canada

- ICMB

- Intelligence Capability Management Board

- Int O

- Intelligence Officer

- Int Op

- Intelligence Operator

- IRMCM

- Intelligence Requirement Management and Collection Management

- L1

- Level 1

- MDDI

- Ministerial Directive on Defence Intelligence

- MESIP

- Military Employment Structure Implementation Plan

- MIP

- Master Implementation Plan

- NATO

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization

- NORAD

- North American Aerospace Defence Command

- NSICOP

- National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians

- OCI

- Office of Collateral Interest

- OGD

- Other Government Department

- OPI

- Office of Primary Interest

- RCAF

- Royal Canadian Air Force

- RCN

- Royal Canadian Navy

- SDIAQ

- Strategic Defence Intelligence Analyst Qualification

- SIGINT

- Signals Intelligence

- SSE

- Canada’s defence policy: Strong, Secure, Engaged

- SWE

- Salary wage envelope

- TB

- Treasury Board

Key Findings and Recommendations

| Key Findings | Recommendations |

|---|---|

Program Management |

|

1. The DIE lacks clear lines of governance and hierarchy between committees and working groups, which leads to information blockages that impede its effectiveness. |

1. Review the governance structure of the DIE in order to develop and implement a governance operating model/Terms of Reference. |

2. Communication across the DIE enables effective coordination; however, the Intelligence Requirement Management and Collection Management (IRMCM) system remains unused by the majority of the DIE, which impedes its capacity to align intelligence activities. |

|

3. The CDI’s ability to effectively exercise FA is challenged by the size and structure of the DIE, and is limited to the extent of the cooperation of Level 1s (L1) across the DIE. |

Observation: The review and compliance function within the Directorate of Intelligence Review and Compliance (DIRC) may be a means to more effectively demonstrate their FA, and should be evaluated for effectiveness in the next evaluation. |

4. The Canadian Forces Information Operations Group (CFIOG), being organizationally located in Assistant Deputy Minister (Information Management) (ADM(IM)), provides effective intelligence support to CFINTCOM. CFINTCOM is currently strengthening the associated processes and communication flow between the two organizations. |

|

Personnel Generation |

|

5. Not all candidates for military positions that Defence Intelligence is receiving possess the desired skills and attributes in order to maintain and progress the Intelligence Enterprise. |

2. Review, revise and implement the selection standards (including academic prerequisites) for Intelligence Operators (Int Op) and Intelligence Officers (Int O). |

6. The instructional staff at the Canadian Forces School of Military Intelligence (CFSMI) were rated very highly from students and senior managers. However, greater training on instructional techniques is required. |

3. To address identified deficiencies with CFSMI, CFINTCOM should:

|

7. The necessary numbers of civilian, military and reservists needed within CFINTCOM is currently unclear; however, DGIE is conducting an internal Functional Model Analysis to determine the required force mixture. |

Observation: The next evaluation should review the force mixture of the DIE and/or CFINTCOM to meet future needs as defined. |

8. Civilians lack a professional development strategy and available time to access training, which hinders their ability to obtain the quality or quantity of training to advance within DND. |

4. Review and communicate career progression standards for civilian Intelligence Analysts and incorporate any necessary changes into the professional development program. |

9. Force Sustainment is a challenge for the Intelligence Enterprise and may come to the detriment of other parts of those organizations. |

|

10. There are GBA+ gaps in the DIE, in applied analysis integration, diversity of personnel, and access to training in both official languages. |

5. To close the gaps in GBA+ considerations, CFINTCOM should:

|

Force Development |

|

11. CFINTCOM risks becoming unable to meet its intelligence requirements and provide input into other L1s due to limited FD capability. |

6. To improve FD effectiveness, CFINTCOM should incorporate the results of the Functional Model Analysis and review its FD processes and procedures implementing necessary changes. |

12. Although the Intelligence Capability Management Board (ICMB) provides a good forum for information sharing, in its current format it is not optimized in the coordination and influence of intelligence FD. |

See recommendations 1 and 6 |

Table 1. Key Findings and Recommendations. This table lists the report’s key findings with associated recommendations.

Table 1 Details - Key Findings and Recommendations.

Note: Please refer to Annex A—Management Action Plan for the management responses to the ADM(RS) recommendations.

1.0 Introduction

1.1 Context for the Evaluation

The evaluation was conducted between January 2019 and March 2020, in accordance with the Five-Year DND/CAF Departmental Evaluation Plan (FY 2017/18 to FY 2022/23), as approved by the Performance Measurement and Evaluation Committee in November 2018.Footnote 2 The evaluation was conducted in compliance with the TB Policy on Results and Directive on Results.

At the March 2018 meeting of the Armed Forces Council Executive, the Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS) directed an in-depth review of the DIE. A joint CDS/Deputy Minister (DM) directive “Defence Intelligence Enterprise Renewal” (DIER) (May 8, 2019) resulted in the DIER initiative, jointly lead by the Chief of Force Development (CFD) and Comd CFINTCOM. The DIER operated concurrently and independently of this evaluation; however, efforts and information sharing were coordinated between the two teams. The DIER may leverage findings and recommendations found in this report. SSE initiative 71 is incorporated in the DIER review.

- DIER Phase Two Problem Definition Paper

The evaluation examined the relevance and performance of Departmental Results Framework (DRF) Programs 2.7 – Ready Intelligence Forces and 4.7 - Intelligence FD, covering the period from FY 2015/16 to 2018/19. The findings and recommendations in this evaluation may be used to inform management decisions related to program delivery and resource allocation. Although the Comd CFINTCOM is the program official, the DIE is much more complex and is dispersed across many operational L1s. Other DIE organizations include: the Canadian Army (CA); the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN); the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF); the Canadian Joint Operations Command (CJOC); the Canadian Special Operations Forces Command (CANSOFCOM); and the North American Aerospace Defence Command (NORAD). Each of these organizations has their own intelligence units.

There have been two previous Evaluations of Defence Intelligence conducted in 2002 and 2015. This program has not been audited previously by the ADM(RS) internal audit function. On completion of the 2002 evaluation, the Department initiated a comprehensive Defence Intelligence Review (DIR).Footnote 3 The approval of the DIR resulted in a significant defence intelligence transformation, including the creation of the CDI under the Vice Chief of the Defence Staff on December 1, 2005,Footnote 4 followed by the creation of CFINTCOM and the elevation of CDI to an L1 organization on June 27, 2013.Footnote 5 Following the 2015 evaluation, the CDI released DAOD 8008Footnote 6 on Defence Intelligence in 2017.

1.2 Program Profile

1.2.1 Program Description

The DIE collects and exploits classified and unclassified information from a wide variety of sources, including national and international partners, to produce actionable defence intelligence for GC and DND/CAF decision makers. Defence intelligence encompasses joint, maritime, land and aerospace intelligence, from tactical to strategic levels, and is enabled by national and international partners and allies, such as the “Five Eyes” community and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).Footnote 7

The DIE has a significant role in Canada’s intelligence architecture, amassing intelligence through various means, including: Signals Intelligence (SIGINT); Geospatial Intelligence; Human Intelligence; Measurements and Signature Intelligence; Technical Intelligence; Social Media Intelligence; Open-Source Intelligence; counter-intelligence; and cyber. The DIE, the largest intelligence capacity in the GC,Footnote 8 employs activities such as all-source analysis, targeting, and information operations, which provide essential, in-demand material to military and political clients.

CFINTCOM, as an operational-support command, is responsible for providing intelligence services and products to DND/CAF decision makers at the tactical, operational and strategic levels. As the principal organization for defence intelligence in the DIE, CFINTCOM has three key roles: intelligence production; force generation of intelligence capability; and functional governance of the DIE.Footnote 9 CFINTCOM’s main mission is “to provide credible, timely and integrated defence intelligence capabilities, products and services to the CAF, DND, GC and Allies in support of Canada’s national security objectives.”Footnote 10 Defence Intelligence is an element of DND/CAF DRF Core Responsibilities 2: Ready Forces and 4: Future Force Design. FA for the DIE, as noted in the MDDI and outlined in DAOD 1000‑10, is held by the CDI, who is also the Comd CFINTCOM. The CDI has the authority to exercise FA for all defence intelligence activities, programs and administration across DND/CAF, and to act as the primary intelligence advisor within DND/CAF and to the GC.Footnote 11 The Comd CFINTCOM has the authority to “lead, coordinate and approve the defence intelligence requirements in support of anticipated, current and future operations; and to direct and employ assigned defence intelligence capability at the strategic level in support of operational objectives as directed by the CDS.”Footnote 12

CFINTCOM has seven principal roles:Footnote 13 develop/promulgate policy, processes and governance as FA for defence intelligence within the GC; identify/prioritize strategic defence intelligence requirements; coordinate the employment of capabilities across the DIE; generate defence intelligence capabilities; conduct defence intelligence operations in support of strategic defence objectives, requirements and missions; establish/maintain relationships with intelligence partners; and coordinate the development of CAF intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance capabilities.

Among other things, CFINTCOM is also responsible for CFSMI, which trains both military Int Ops and Int Os. A Transfer of Command Authority ceremony from CMP to CFINTCOM for CFSMI was held on April 17, 2018, making CFINTCOM the Designated Training Authority with full control over training material and delivery. Civilian Intelligence Analysts, as part of the Defence Intelligence Officer Recruitment Program are trained through the Strategic Defence Intelligence Analyst Qualification (SDIAQ) modules run by CFINTCOM, as well as courses run by other government departments (OGD).

With the implementation of SSE, the GC is committed to making significant new investments in DND/CAF capabilities in the coming decade. Specifically, SSE allocated new investments to CFINTCOM, including significant military and civilian personnel growth (SSE 70), with additional emphasis on new capabilities across the DIE (SSE 71).Footnote 14

1.2.2 Program Objectives

The objective of DRF program 2.7 – Ready Intelligence Forces is to prepare forces to provide responsive, reliable and fully integrated intelligence capabilities, products and services which will inform and support decision makers, resulting in actions relating to operations and activities carried out by National Defence. This objective ensures that CFINTCOM elements meet Force Posture and Readiness requirements, allowing for the success of mandated DND field operations in continually evolving, multifaceted theatres.

The objective of DRF program 4.7 – Intelligence FD is to invest in the development of Joint Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance and communication forces and platforms, including next generation surveillance aircraft, remotely piloted systems, space-based surveillance assets and classified networks. This objective allows CFINTCOM to provide near real-time support to missions and senior decision makers by understanding the future security environment, and developing and designing the future force to meet those future needs. Through collaboration, innovation and advanced research, this will enhance the identification, prevention, adaptation and response capabilities extending across a wide scope of possible scenarios.

DRFs 2.7 and 4.7 are specific to CFINTCOM. Defence Intelligence activities conducted by other members of the DIE are reflected in other DRFs.

1.2.3 Stakeholders

CFINTCOM is identified as the L1 for the program. Other stakeholders internal to DND/CAF include: the Minister of National Defence; the DM; CANSOFCOM; CJOC; NORAD; ADM(Information Management) – CFIOG; ADM(Science & Technology); ADM(Policy); CMP; CA; RCN; and RCAF. External stakeholders to DND/CAF include: Communication Security Establishment; Canadian Security Intelligence Service; Privy Council Office; Public Safety Canada; Transport Canada; Canadian Boarder Service Agency; Integrated Terrorism Assessment Centre; Global Affairs Canada; Royal Canadian Mounted Police; NORAD; and NATO.

1.3 Evaluation Scope

1.3.1 Coverage and Responsibilities

The evaluation examined the effectiveness of the program. Due to time and security limitations, the scope of the evaluation focused on three main themes: program management; personnel generation; and FD – the processes, people, and capabilities in place to create timely and actionable intelligence. As per the DND/CAF 2019/20 Departmental Plan,Footnote 15 the evaluation integrated GBA+ into all phases and methodologies of the project in order to help fulfil the commitment of leading a more inclusive and effective Defence Team.

The evaluation did not examine any areas requiring Level III (Top Secret) access or above due to classification restrictions.

1.3.2 Resources

Using the Chief of Programme DRF Expenditure Report, program expenditures are estimated at $169 million for FY 2018/19. Due to the sensitivity of the program and security issues, a cost benefit analysis was not completed. CFINTCOM has just under 1,100 personnel located across Canada and internationally, with approximately 75 percent Regular and Reserve Military and 25 percent civilian personnel.Footnote 16

1.3.3 Issues and Questions

In accordance with the TBS Directive on Results (2016),Footnote 17 the evaluation report addresses the evaluation issues related to relevance and performance. An evaluation matrix listing each of the evaluation questions, with associated indicators and data sources, is provided at Annex D. The methodology used to gather evidence in support of the evaluation questions can be found at Annex B.

2.0 Findings and Recommendations

2.1 Relevance

Defence intelligence is relevant, appropriate for the responsibilities of the federal government, and aligns with DND/CAF priorities. “Defence intelligence is critical to the success of CAF operations and the fulfillment of the DND/CAF mandate: for the defence of Canada; the defence of North America (with the United States); the promotion of international peace and security; and supporting lawful requests from other government departments for defence intelligence support.”Footnote 18 The National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians (NSICOP) also noted the essentiality of defence intelligence in a 2018 report. The 2015 evaluation also found that defence intelligence aligns with GC and DND priorities, federal roles and responsibilities, and that there is an ongoing and demonstrable need for defence intelligence activities in DND/CAF.

2.2 Performance

2.2.1 Program Management

Key Finding 1: The DIE lacks clear lines of governance and hierarchy between committees and working groups, which leads to information blockages that impede its effectiveness.

The governance structure of the DIE is made up of a number of committees and working groups to facilitate program management; however, the links between them and their overall hierarchy remain unclear and undocumented. While there was a general consensus that management was sometimes able to receive the information they needed to make decisions, there were concerns that information was not always disseminated up and down to the rest of the DIE. Thus, the channels enabling the flow of strategic initiatives and direction from the CDI across the DIE are hindered, impacting decision making and implementation.

Although the flow of information upwards within the DIE appears effective for senior management, there are risks within the governance structure that could limit their awareness. Results from the management survey indicated that 87 percent of respondents believe that intelligence committees provide useful information sharing to ensure sound decision making. DIE stakeholder interviews agreed with this and noted that management within their respective organizations was sufficiently aware of upcoming policy changes. Particular to CFINTCOM, managers noted that they were sufficiently informed by the governance structure. However, a risk identified by a few interviewees noted that the lack of clear governance lines has resulted in some committees and working groups lacking a higher authority to which they may raise issues or be held accountable; for example, the Defence Intelligence Open Source Network Working Group. Should this remain unresolved, the effectiveness and awareness of activities conducted by these groups may be negatively impacted.

Conversely, the flow of information downwards within the DIE is an issue that hinders strategic direction and implementation. Results from the management survey indicated that 67 percent of respondents external to CFINTCOM believe the governance structure does not establish strategic direction. This was supplemented by 64 percent of comments from respondents to open-ended questions pertaining to this issue. Further, 20 percent of comments indicated that information does not always flow downwards from committees to be actioned. The DIER governance focus group highlighted a need for clearer strategic direction and guidance,Footnote 19 which led to the conclusion in its Problem Definition Paper that there is no coherent strategy for the DIE as a whole.Footnote 20 Interviews with CFINTCOM management agreed with these conclusions, acknowledging that the governance structure lacked clear lines of governance to enable the flow of direction from the CDI at the strategic level downward to operational and tactical levels, impacting implementation. Within CFINTCOM, management has been using town halls as a means to engage lower levels of leadership to ensure that strategic initiatives are more thoroughly disseminated and understood. However, if there is no increased support of formal communication channels, the dissemination challenges at the operational and tactical levels of the DIE will persist, as discussed in Finding 2.

Key Finding 2: Communication across the DIE enables effective coordination; however, the IRMCM system remains unused by the majority of the DIE, which impedes its capacity to align intelligence activities.

In the coordination of intelligence activities, formal and informal means of communication are used across the DIE. The evaluation found that both methods of communication were satisfactory for coordination; 93 percent of respondents from the management survey indicated that they have sufficient levels of communication. Additional evidence from interviews with DIE stakeholders, supplementary survey comments, as well as observations of DIER focus groups and the ICMB supported this finding.

Informal methods of communication are prevalent throughout the DIE and integral to the coordination of intelligence activities. Interviews with stakeholders revealed that communication on an ad hoc basis with other organizations was a regular practice. Interviewees stated that since the DIE was such a small community, it was easy to contact each other personally; problems could be solved by “picking up the phone.” Using informal networks, the members of the DIE are able to effectively align, collaborate and prioritize their intelligence activities. However, a few interviewees noted a risk in the reliance on personality rather than processes; when an individual changes positions, it could severely impact the effectiveness of the network. This could be circumvented by formalized IRMCM processes.

The DIE has a number of fora which serve as formal bodies to share information: the Defence Intelligence Management Committee; the Intelligence Direction Collection Board; and the ICMB, to name a few. Eighty-seven percent of respondents to the management survey indicated that the committees were useful information-sharing bodies. Interviewees identified the Intelligence Direction Collection Board as a particularly successful committee. Despite this, interviews with stakeholders across the DIE questioned whether committees effectively coordinate intelligence activities since they lacked authority to make decisions. Thus, meetings rarely lead to actionable tasks. CFINTCOM senior management acknowledge this challenge and stated that many of the committees lack appropriate support in the form of secretariats to ensure greater follow-up on tasks.

The IRMCM system is a program management tool vital to coordination and the overall intelligence cycle.Footnote 21 However, there is no evidence that a system is in place and being used to facilitate formal coordination. Interviews revealed that a system referred to as ICECAP was once used as a request for information management tool; however, it presently remains unused and unmanaged. The DIER Problem Definition Report likewise identified this as an issue, stating “…IRMCM requires investment in order to properly drive the intelligence cycle and to ensure that critical information requirements are tasked for collection activity.”Footnote 22 A system should be decided upon to ensure that risks impacting the coordination of intelligence activities are decreased.

ADM(RS) Recommendation

Key Finding 3: The CDI’s ability to effectively exercise FA is challenged by the size and structure of the DIE, and is limited to the extent of the cooperation of L1s across the DIE.

The Comd CFINTCOM, in the role as CDI, is granted FA over defence intelligence by the CDS and the DM, as per the MDDI, the Ministerial Directive on Defence Intelligence Priorities, and DAOD 1000-10. Still, the concept of FA remains misunderstood across DND/CAF, which has made the interpretation of roles and responsibilities as well as the exercise of FA unclear. Nevertheless, 88 percent of management survey respondents indicated that the CDI had a sufficient level of FA. This was echoed in interviews with the CFINTCOM management.

As mentioned in the introduction, the DIE is comprised of a number of L1 organizations that undertake intelligence activities in support of their operations. However, CFINTCOM and the CDI are tasked with the coordination and guidance of the enterprise to provide holistic defence intelligence solutions for DND/CAF.Footnote 23 As such, the CDI has the capacity to set standards, priorities, etc.; however, the other L1s have significant autonomy in following them. Interviews with DIE stakeholders indicated that the Chain of Command would always take priority and that CFINTCOM has no tasking authority, in their opinion. Nevertheless, as discussed in Finding 2, the DIE’s collaborative network of communication enables CFINTCOM to coordinate tasks and adjust priorities. Interviewees repeatedly stated that there was “a lot of good will” that facilitates this effectiveness.

Although definitions of FA exist, in practice there is a lack of understanding in its interpretation into roles and responsibilities. Interviews with legal advisors concluded that FA was an unclear legal concept. They noted that the assignment of FA authorizes oversight but that it was not a legal delegation of authority. Thus, the CDI has oversight authority over defence intelligence but no direct authority over intelligence activities, such as committee decisions. In 2018, CFINTCOM released DAOD 8008, which links to both Ministerial Directives while also outlining a number of roles and responsibilities of L1s.Footnote 24 DIE stakeholder interviews noted that the DAOD helped in some respects, but it was not directive in nature and lacked teeth to ensure compliance. CFINTCOM acknowledges these concerns, and has indicated that a new CDS Directive is presently underway to operationalize the MDDI to fill in the “missing link” between the Chain of Command and FA.

A major component of the CDI’s FA has been the release of policies in the conduct of defence intelligence activities. DIE stakeholder interviews and the DIER governance focus group highlighted the importance of this role, indicating that they wished for increased policy direction.Footnote 25 A 2018 NSICOP report stated that in order to enhance accountability of the Defence Intelligence program, tracking and measurement of compliance should be done.Footnote 26 In response, the DIRC was organizationally moved under the direct authority of the Assistant Chief of Defence Intelligence (ACDI) to ensure greater visibility within the DIE. DIRC’s mandate includes the management of external review as well as compliance of DIE members to policy released by the CDI. DIRC is still in the early phases of its activities; however, it has developed a number of methods to monitor compliance and to provide support for units that have been unsuccessful in meeting compliance requirements. DIRC has indicated that they have been well received by the DIE, and that commanders have been requesting feedback and input. The activities of DIRC may be a means for CFINTCOM to successfully demonstrate its capacity to exercise FA in the context of defence intelligence policy; however, the initiative is not yet fully developed to reach a conclusion.

Observation: The review and compliance function within the DIRC may be a means to more effectively demonstrate their FA, and should be evaluated for effectiveness in the next evaluation.

Key Finding 4: CFIOG, being organizationally located in ADM(IM), provides effective intelligence support to CFINTCOM. CFINTCOM is currently strengthening the associated processes and communication flow between the two organizations.

During the conduct of initial interviews, a number of stakeholders and senior leadership raised the question of whether CFIOG was appropriately located to support CFINTCOM’s intelligence production. CFIOG, within ADM(IM), generates and employs SIGINT for the DIE.Footnote 27 As a result, discussions concerning whether it should be placed within CFINTCOM or remain under ADM(IM) have persisted since its creation. Opinions were incredibly mixed; the management survey indicated 38 percent who said they did not know if CFIOG’s current placement was optimal, while 31 percent said either yes or no. Even those who said no added that they were unsure of where else it could be placed. Interviews with DIE stakeholders made similar comments. An interview with CFIOG revealed that SIGINT is only a small portion of what they do and that the movement of CFIOG would do more harm than good to other activities of the organization (e.g., cyber operations).

Considering CFIOG’s effectiveness, 63 percent of respondents to the management survey stated that they were unsure of whether the flow of information from CFIOG to CFINTCOM was timely and effective, while 31 percent said that it was effective and only 6 percent of respondents said it was ineffective. This indicates that although communication is generally effective, the processes enabling it are unclear. Interviews with CFINTCOM and CFIOG revealed that there are a number of relationships enabling communication, such as tasking mechanisms and policy dialogues, as discussed in Finding 2. However, they also stated that these mechanisms are not well reported to the rest of the DIE, which has resulted in tasking requests coming from multiple points, rather than one concentrated point. This presents a risk to the effectiveness of the communication flows between the organizations. CFINTCOM has acknowledged this and is working to better promulgate the liaison role between CFINTCOM and CFIOG to ensure that requests flow through appropriate channels, and that the rest of the DIE is aware of these processes. As discussed in Finding 2, an appropriate IRMCM system may mitigate these risks.

2.2.2 Personnel Generation

Key Finding 5: Not all candidates for military positions that Defence Intelligence is receiving possess the desired skills and attributes in order to maintain and progress the Intelligence Enterprise.

Of the military candidates that are recruited to the DIE, there is a lack in certain proficiencies required to perform effectively; namely, oral and written communication, and the ability to read, digest and accurately summarize vast amounts of information. Interviews and survey responses revealed that briefing is a challenge for some, and a better comprehension of intelligence to generate products is desired. “Most notably, there needs be more of an emphasis on identifying a set of desirable traits and qualities, not simply basing selection on the level of education required.”Footnote 28 Interviewees noted that the current educational requirements are sufficient, and yet the majority of respondents to the surveys indicated that the degree selection could be expanded to a variety of disciplines. This would be comparable to OGDs’ intelligence programs, which are open to diverse degrees.

The lack in these proficiencies is further challenged by under-informed recruiting practices. Interviews, focus groups and survey responses indicated dissatisfaction with recruitment, as recruiters are thought to have a poor grasp of intelligence occupations, restricting their ability to properly guide candidates to suitable occupations. One interviewee disagreed with this position. As found in the focus groups, “While it was noted that the DIE is enjoying success in attracting educated and motivated applicants, there was general consensus amongst participants that there is room for improvement in the screening and selection criteria for military members of the DIE.”Footnote 29 Half of the trainer survey respondents indicated the need for closer collaboration and communication with Canadian Forces Recruiting Group (CFRG). Twenty‑six percent of military respondents to the survey provided negative feedback regarding recruitment when asked if there are any challenges or barriers to recruitment within defence intelligence. An informal poll at the trainee focus group indicated that all participants were dissatisfied with the information provided by recruitment. Focus group attendees suggested having greater access to Int Os and Int Ops during recruiting to ask questions; however, a separate interviewee stated that intelligence personnel contact information is provided to recruiting centres. This inconsistency could be outside the control of the program as it could be due to different approaches of recruiters. CFRG confirmed that there are no specific materials provided for Int Os or Int Ops, and that recruiters encourage applicants to review information available on the website and ask questions to void any potential knowledge gaps.

Expectation management of recruits needs to be addressed during recruiting, as direct hires do not appreciate the academic nature of the intelligence function. Since intelligence occupations are generally unknown to the public, interviewees stated that recruits are often informed by popular perceptions. If this impression is not modified, interviewees noted that defence intelligence risks higher front-end attrition rates.

ADM(RS) Recommendation

Key Finding 6: The instructional staff at the CFSMI were rated very highly from students and senior managers. However, greater training on instructional techniques is required.

Collectively, the instructors at CFSMI were rated very highly by trainees, staff at the school, intelligence personnel and CFINTCOM senior management. Survey responses noted that the instructors care a lot about their students’ success, and that their enthusiasm, willingness to teach and career advice were appreciated. Interviewees noted that CFINTCOM attracts high-quality instructors needed to train future generations of intelligence occupations by selecting those with recent operational experience who have in-depth knowledge of the latest techniques in the intelligence function, and awarding additional career progression points for having taught at the school.

However, the evaluation also heard that the instructors are overextended. While the instructional force has only doubled, interviewees noted that CFSMI throughput has octupled. CFSMI is continuing to increase the number of courses they teach, but the personnel shortage is a barrier. As noted in Armed Forces Council Intelligence Command Way Forward, “There is no capacity to train additional intelligence personnel to meet growth targets established by SSE.”Footnote 30 Since the model for intelligence personnel now includes direct hires with no previous CAF experience, the instructional team now faces additional pressure to teach the standard aspects of military life, such as drill, which is in addition to the intelligence modules. Interviewees stated that CFSMI continues to receive increased funding to reduce this burden in order to fund contractors and develop course updates, and that CFINTCOM is providing phenomenal support to the school to facilitate their success, but the overwhelming amount of work at CFSMI continues to be a reality.

Course material has been identified as a particular area of concern by trainers, trainees and management alike. At present, CFSMI is concurrently running legacy courses as well as newly updated MESIPFootnote 31 courses, which creates an additional challenge of running two curricula. Of military intelligence personnel that responded to the survey, 35 percent felt unprepared to some degree for their future work in intelligence. Further, there is no course tracking for personnel nor any course validation being completed at this time. CFSMI is currently working to update and rewrite all training material as resources allow, and early indicators show an improvement over previous course material.

While trainers are valued for their commitment to teaching, evidence reveals that they receive little to no training themselves on how to be an effective instructor. Personnel acquire a posting at CFSMI based on their military leadership credentials, but arguably, leadership skills do not always equate to teaching skills. CFSMI provides a week’s worth of training on the Advanced Instructional Technics course taught by the Training and Development Officer; however, the course is not mandatory. One respondent to the survey stated “Instructors aren’t trained. There is not enough time to improve, and there is no training provided on how to teach, so they can’t grow and develop as instructors.” A “Train the trainer” course could be considered.

ADM(RS) Recommendation

Key Finding 7: The necessary numbers of civilian, military and reservists needed within CFINTCOM is currently unclear; however, DGIE is conducting an internal Functional Model Analysis to determine the required force mixture.

There is consensus among CFINTCOM that there is a shortage of intelligence personnel; however, the true force mixture and overall desired quantity remains unknown. SSE initiative 70 provided CFINTCOM with the means to recruit and hire 300 new intelligence personnel (i.e., 120 military and 180 civilians). Interviewees indicated this figure was generated within fiscal limitations and does not accurately reflect the necessities of the branch. DIER Focus Group participants expressed concern with the critical shortage of both military and civilian intelligence personnel, leading to burnout and retention issues, exasperated by the excess demand for intelligence compared to current and future capabilities.Footnote 32 Other causal factors are discussed in Finding 11.

The required ratio of civilian to reserves to regular force to best support CFINTCOM is unclear. Ninety percent of interviewees agreed that the DIE should employ more civilian personnel, as they provide longevity of corporate knowledge, subject matter expertise and consistency within the branch. However, civilians still require military knowledge and context at senior levels to align operational needs with corporate requirements. Reservists are seen as integral to the intelligence function, but face challenges regarding deployment, funding and recruitment. DGIE is conducting a Functional Model Analysis within CFINTCOM to determine the optimal force mixture essential to ensuring future defence intelligence success. This analysis will face the same fiscal realities of SSE, but may provide evidence in support of future DTEPFootnote 33 requests.

Observation: The next evaluation should review the force mixture of the DIE and/or CFINTCOM to meet future needs as defined.

Key Finding 8: Civilians lack a professional development strategy and available time to access training, which hinders their ability to obtain the quality or quantity of training to advance within DND.

Civilian career management within CFINTCOM may not sufficiently support analysts in meeting the requirements of senior management. Of the civilian intelligence analysts who responded to the survey, 77 percent believe current career management is inadequate for upward opportunities, and senior management agrees: “There is no talent management strategy to attract, secure, manage and retain the workforce.”Footnote 34 This issue is extant from the 2015 evaluation, which stated “There is no common career management framework for civilian intelligence personnel.”Footnote 35 That evaluation recommended the creation of an “appropriate DND/CAF human resources strategy for public servants who are employed within the DIE to support both federated production and human resources capability management.” In response to this, CFINTCOM created the Defence Intelligence Officer Recruitment Program (DRP). The DRP, while felt to be “an effective and appreciated endeavor,”Footnote 36 requires more formalized business processes, including standardized and mandated training, mentoring, a program mandate, as well as administrative and operational policies, according to interviewees and survey responses. After the DRP, which finishes at EC05, career management is expected to be self-directive. While the DRP has improved the development of analysts from the EC02 to EC05 levels, middle management positions may not be sufficiently trained for further upward movement.

Civilian trainees who are enrolled in the DRP are developed through the SDIAQ modules; however, support to attend training may not be factored into daily business, and the quality of training has been questioned in interviews and surveys. Responses from the management survey indicated that a majority believe the quality of training for intelligence analysts needs to be improved; 44 percent disagreed to some extent that civilians are capable and knowledgeable as a direct result of the training received through the SDIAQ modules. Of current intelligence personnel who responded to their survey, only 45 percent were satisfied to some degree with the training they had received, and 80 percent of current civilian trainees who responded to their survey are satisfied with the training they are receiving, indicating improvement in this area. Furthermore, since the SDIAQ modules available to DRP trainees are not mandatory for progression through the development program, combined with the rapid pace and high volume of business, training is not prioritized. Intelligence analysts without the foundational training provided by all eight SDIAQ modules limits their competitiveness for high-level work.

The training and experience required to obtain senior management positions within CFINTCOM is not well articulated or emphasized within the branch. Interviewees acknowledged that little value is placed on managerial skill enhancement and training. Deployments and OGD experience are vital to career development, and yet this is not communicated well. Moreover, due to the fast-paced environment, there is little time to take these opportunities. Interview and survey responses revealed that internal DND candidates were screened out of recent EC07 and EX01 competitions, putting into question whether their training standards align with those of senior management expectations. This was also echoed by the DIER report.Footnote 37 If analysts do not see opportunities for upward progression, CFINTCOM risks increased attrition rates.

ADM(RS) Recommendation

Key Finding 9: Force Sustainment is a challenge for the Intelligence Enterprise and may come to the detriment of other parts of those organizations.

While intelligence forces are able to be deployed with minimal difficulty, sustainment has been identified as a risk area that hinders domestic organizations. Sixty-four percent from the management survey disagreed to some extent that intelligence forces are able to be deployed and sustained effectively within the prescribed timelines, and interviewees emphasized that the issue is sustainment. One interviewee stated, “there needs to be a balance between intelligence architecture overseas and intelligence based domestically to support operations. All deployed missions are met, but the sacrifice has been our own institution/missions here in Canada. The branch suffers.” The majority of interviewees agreed that the ability to sustain is not strong, and one environment will be conducting a manning analysis to gather further evidence to this effect. As intelligence units are notably understaffed,Footnote 38 and may continue to be so, deployed operations risk the capacity of the domestic organization to fulfill their responsibilities.

The lack of capacity to sustain operations jeopardizes future operations as well. According to interviewees, with eight new missions named in SSE,Footnote 39 not all organizations within the DIE may be able to continue to deploy and sustain effectively. “At this time, demand for Intelligence personnel and capabilities is far outstripping current capability and there is fear that even with future growth, future demand will increasingly outpace future personnel capability.”Footnote 40 This is compounded by the lack of rest cycles and limited specialty capabilities available for deployment. As a result of “widespread DIE personnel shortages,”Footnote 41 the DIE may have challenges training and retaining intelligence forces, further endangering the health of defence intelligence.

Key Finding 10: There are GBA+ gaps in the DIE, in applied analysis integration, diversity of personnel, and access to training in both official languages.

Integration of GBA+ into all facets of business is essential for success, and mandated by the GC;Footnote 42 however, the DIE is lacking in multiple areas in this regard. Overwhelmingly, interviewees, survey respondents and focus group participants agreed that the DIE should be “an organization that not only leverages the operational and institutional advantages associated with a broad range of backgrounds, perspectives and capabilities, but one that – ultimately – understands them as necessary for success.”Footnote 43 The DIE has shortcomings when applying GBA+ into intelligence products, the diversity of the personnel generating those products, and equal access to training in both French and English.

Analysis

Incorporating GBA+ into intelligence analysis and production ensures contextual clarity and maximum coverage of perspectives. All interviewees agreed that diversity is crucial. Survey respondent opinions were equally mixed on whether gender and diversity requirements were taken into consideration in the development of training for intelligence analysts, and 41 percent responded that they did not know, indicating a gap. A senior manager within CFINTCOM stated that “limited amounts of CFINTCOM staff have taken GBA+ training opportunities, limiting understanding and senior leadership ability to influence greater GBA+ conceptual application within the command.” The evaluation confirmed there is GBA+ training available in which examples are provided where intelligence assessments have been flawed due to inherent biases. Senior leadership concurred that, going forward, all CDI operational orders and CFINTCOM tasking orders will have GBA+ considerations. Improvement is vital to contextual analysis while on operations as well as building partner capacity.

Diversity of personnel

The DIE is impacted by a legacy of occupational transfers into the community, thus leaving the enterprise disadvantaged without the true representation of Canada it requires in the modern age. Previously, intelligence occupations were only open to those transferring from other occupations, having served elsewhere in the military first. This inherently decreased the number of women entering intelligence. Diversity is mentioned 47 times in SSE as a priority of DND and the GC, and includes all types of identity factors. The Women in the Canadian Armed Forces backgrounder states “Canada’s military continues to strive to better reflect Canadian society in our ranks as we promote Canadian values at home and abroad,”Footnote 44 which indicates its importance to senior DND/CAF officials. Table 2 shows the various identity factors of different populations studied during the evaluation, and indicates a lack of diversity among those in defence intelligence and potential barriers. Interviewees suggested the legacy gender imbalance may eventually resolve as the younger generation of direct hires is more diverse.

Population |

Identity Factors |

n = |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Intelligence Occupation Survey |

80% Caucasian 89% menFootnote 45 92% male |

20% non-Caucasian 11% women 8% female |

167 |

Senior Management Survey |

76% male |

24% female |

19 |

CFSMI Trainers Survey |

100% male |

0% female |

15 |

DND Total |

84% men |

16% womenFootnote 46 |

96,822 |

Table 2. Identity Factors of Defence Intelligence Personnel compared to DND Statistics. Source: Analysis of ADM(RS) Evaluation of Defence Intelligence distributed surveys. (2019).

Table 2 Details - Identity Factors of Defence Intelligence Personnel compared to DND statistics.

However, no specific hiring strategy has been identified to increase diversity. The 2018 Int Op Annual Military Occupation Review (AMOR) indicates that the representation of women is slightly lower than the rest of the regular force, with a higher representation in the lower ranks, optimistically indicating a future shift in the senior management gender split. Although CFRG has a current intake goal for Int Ops of 42.8 percent female and Int Os has an intake goal of 68.7 percent female to reach DND-wide targets of 25 percent female by 2023, no similar targets have been set for visible minorities or indigenous applicants for Int Os and Int Ops. The 2018 Int O AMOR indicates slightly lower representation of women, visible minorities and First Official Language (FOL) French than the rest of the regular force on whole. Int Ops have a slightly lower representation of indigenous peoples and FOL French, but 3 percent higher for visible minorities. Security clearances were also noted as a potential barrier for those with diverse backgrounds or travel experience. Civilian intelligence analysts tend to be a more diverse group of individuals, as can be seen in Table 3. Without concrete strategies for increasing diversity within CFINTCOM, intelligence risks missing possible advantages that a diverse workforce brings.

Diversity in CFINTCOM - % |

||

|---|---|---|

Civilian Analysts |

Military |

|

Women |

32 |

14 |

Visible Minorities |

9 |

7 |

Persons with Disabilities |

7 |

3 |

Aboriginal Peoples |

2 |

3 |

Table 3. Diversity in CFINTCOM. Average of years CMP DHRD, study of CFINTCOM workforce evolution from FY 2014/15 – 2017/18.

Table 3 Details - Diversity in CFINTCOM.

Training in both official languages

While CFINTCOM, as the organization responsible for CFSMI, has an obligation to provide intelligence training in both official languages, that requirement is not always met with equal opportunity due to a lack of resources. Evidence from multiple sources reveals that CFSMI has few French-speaking instructors and little funding for translation. The lesson plans that are translated still require improvement to meet language equivalency requirements. Interviewees and focus group participants voiced that French courses “are the exception, not the rule,” and that non-English-speaking trainees are at a disadvantage; however, data does not exist to verify this challenge. To offset this obstacle, exams at CFSMI are offered in both official languages, French assist is available, and the school is devoting time and resources where possible to ensure satisfactory future French serials.

ADM(RS) Recommendation

2.2.3 Force Development

Key Finding 11: CFINTCOM risks becoming unable to meet its intelligence requirements and provide input into other L1s due to limited FD capability.

The evaluation repeatedly found evidence of challenges concerning intelligence FD. Surveys, interviews with managers across the DIE and CFINTCOM, as well as focus groups run by the DIER all concluded that there were a number of FD limitations. This has impacted both CFINTCOM’s ability to meet its own intelligence FD requirements, as well as CFINTCOM’s ability to provide input into the FD of other L1s across the DIE. The DIER Problem Definition Paper highlighted this issue stating, “We are underinvested in the force development of defence intelligence capabilities.”Footnote 47 In a 2018 briefing to the Armed Forces Council, the Comd CFINTCOM noted, “emerging capabilities critical to the future of the DIE are unserviced…”

The following challenges were identified in CFINTCOM’s conduct of FD:

- CFINTCOM managers indicated that FD is often sacrificed to meet operational needs and cited Afghanistan as an example, in which operations were “so strapped for personnel, all FD things ended up getting cut.”

- Twenty-six out of 50 DGIE FD tasks are coded “red” receiving limited attention.

- Eighty three percent of respondents to the senior management survey indicated that CFINTCOM is not present at key capability development committees, and that their intelligence capability requirements are not articulated or understood. Thus, CFINTCOM is often late to engage in project development, which increases the risk of sub-optimal solutions.

- DIE stakeholder interviewees noted the difficulty in obtaining CFINTCOM support to action priority files, which is vital to ensure that intelligence systems across the DIE are appropriately integrated into CFINTCOM’s networks.

- Interviewees noted that ill-defined processes contributed to these challenges, and that the “conceive, design, build, manage” ethos of FD was deficient in CFINTCOM.

- Additionally, a few comments noted that Canada lags behind its Allies in this regard, which complicates the integration of intelligence activities between nations. An example was provided explaining how Canadians receive intelligence training abroad in the United States and United Kingdom, but upon return to Canada are faced with working with limited capabilities.

There are a number of factors contributing to these challenges:

- Seventy-one percent of respondents to the management survey indicated that there is insufficient staff capacity for CFINTCOM to conduct FD, while 86 percent of respondents stated that CFINTCOM’s lack of resources has hindered it from participating in FD across DND/CAF. This sentiment was overwhelmingly confirmed by interviewees internal to CFINTCOM and DIE stakeholders.

- There is a lack of project management expertise in intelligence personnel to effectively facilitate FD, as identified from a number of interviews with CFINTCOM senior management. Thus, CFINTCOM lacks individuals skilled and trained in the understanding of FD processes.

- Survey comments and interviewees have indicated a need for clearer governance and organizational structures for FD intelligence in order to ensure that intelligence FD processes align with the greater DND/CAF FD processes, as well as those of Allies.

- Particular to CFINTCOM’s lack of FD input, it was noted that when a project does not directly involve intelligence activities, project managers will not seek out the intelligence FD community, due in part to Technical Authorities not understanding the business of intelligence. Further, senior review boards do not always require intelligence input.

- The DIE looks to CFINTCOM to establish FD standards; however, as stated by interviewees, there are few established and those that do exist are not always followed. DIE stakeholder interviews reveal that L1s find solutions in the absence of standards. Nevertheless, the lack of standards will hinder the DIE as they proceed in intelligence FD.

In response to these concerns, CFINTCOM senior managers indicated that the Functional Model Analysis (discussed in Key Finding 7) may alleviate personnel shortages. Later phases of the DIER will develop a Course of Action and Implementation Plan that will seek to address many of these concerns.

ADM(RS) Recommendation

Key Finding 12: Although the Intelligence Capability Management Board (ICMB) provides a good forum for information sharing, in its current format it is not optimized for the coordination and influence of intelligence FD.

The ICMB is the principle board concerning matters of defence intelligence FD.Footnote 48 While DIE stakeholders strongly agreed that it is a useful information-sharing body, its effectiveness as an influence, integration and decision-making committee has been questionable. CFINTCOM management state that the ICMB has no teeth. Additionally, there are no working groups in support of the ICMB. DIE stakeholder interviews indicated that they are unsure as to whether it is meeting its mandate. One interviewee questioned the necessity of the ICMB if it was only an information-sharing body, while other DIE stakeholders stated that there was already awareness of DIE FD activities. CFINTCOM management disagrees with this view warning against underestimating the value of an information-sharing forum.

Personnel shortages were widely cited as the major factor influencing the ineffectiveness of the ICMB impacting the development of strategy, plans or doctrine in support of FD. Furthermore, the lack of a secretarial staff to take minutes, track tasked action items, and monitor the health of the board hinders the effectiveness of the ICMB.

An additional factor identified was the impact of representation to and the authority of the ICMB. Comments from the management survey noted that FD components of other L1s are not always present at the ICMB. For example, the RCN is currently represented by Director Naval Information Warfare and not by Director Naval Requirements; further, CFD is not represented. As a result, those with the most FD influence and expertise are not present to provide their input. The authority of the ICMB is challenged similarly in that it has no cross-L1 executive authority to make any decisions. This is a problem inherent to DIE committees, as discussed in Finding 2. An interviewee added that the ICMB should have a reporting line to the Defence Intelligence Management Committee in order to raise issues to a higher authority. As discussed in Finding 3, the DIE looks to CFINTCOM for the development of policies and standards. This may be an area where the ICMB could seek to be more effective.

There is evidence of change underway in the functioning of the ICMB. Recent meetings have included action items and follow-up. The DIER has noted FD as a problem area in its Phase 2 report and will be developing plans to improve the current situation.

ADM(RS) Recommendation

Conclusion

The activities of program management, personnel generation and FD, contribute effectively in meeting the outcomes of the Defence Intelligence program as outlined in the program logic model in Annex C. Completion of the recommendations in this report will help ensure that these capabilities are preserved and enhanced.

The Defence Intelligence program is making progress in addressing its SSE OPI responsibilities. SSE 70, the establishment of additional intelligence positions is being addressed by a Functional Model Analysis to determine the required force mixture. SSE 71, building CFINTCOM’s capacity to provide more advanced intelligence support to operations, is being addressed through the work of the DIER.

Annex A—Management Action Plan

Program Management

Note: The DIERFootnote 49 Master Implementation Plan (MIP) will address the majority of the ADM(RS) recommendations contained in the Evaluation of Defence Intelligence Report (2020). Formulation of the DIER MIP will commence in September 2020, following the approval of the selected DIER Course of Action by the CDS and DM. Implementation of the DIER MIP will involve a program-centric approach, with CFINTCOM L2s responsible for project advancement, in consultation with DIER staff and L1 Defence Intelligence stakeholders. As noted in this Management Action Plan, CFINTCOM will immediately commence efforts to address the ADM(RS) recommendations. These efforts will be closely aligned with DIER MIP development.

ADM(RS) Recommendation

Management Action

CFINTCOM Action Item 1.1

ADM(RS) Recommendation 1 and Key Findings 1, 2, 3 and 4 are directly related to DIER Problem Statement 2: Defence Intelligence does not function as an enterprise.Footnote 50 CFINTCOM has significantly improved coordination with the broader DIE and the OGD intelligence communities over the past few years, but challenges remain. The DIER Rapid Implementation Initiative – Governance Operating Framework is intended to develop and implement a more effective governance model through the development of enhanced functional directives, orders, policy and terms of reference. Led by the DIER, this effort will be conducted in partnership with the Director General Intelligence Policy and Partnerships (DGIPP), who is responsible for overseeing Defence Intelligence governance and policy, and managing Defence Intelligence programs on behalf of CDI.

OPI: DGIE and DGIPP

OCI: COS, ACDI, CF Int Gp, L1 Defence Intelligence Stakeholders

Target Date: July 2021

Personnel Generation

ADM(RS) Recommendation

Management Action

CFINTCOM Action Item 2.1

ADM(RS) Recommendation 2 and Key Finding 5 are directly related to DIER Problem Statement 3: The Defence Intelligence workforce must evolve. CF Int Group, in consultation with the DIER study team and the Special Advisor to Comd CFINTCOM/Intelligence Branch Advisor, are currently conducting the annual MESIP review for the Int Op (MOSID 000099) and Int O (000213) occupations. A review, revision and implementation of the selection standards will be included in their annual review. This effort will be augmented by the DIER Rapid Implementation Initiative – MESIP Review, which will commence in the fall of 2020. This work is also being done in consultation with OGDs and the Five Eyes DIE.

OPI: CF Int Gp in consultation with Special Advisor Comd CFINTCOM and DIER

OCI: COS, ACDI, DGIPP, L1 Defence Intelligence Stakeholders

Target Date: Analysis complete by July 2020; implementation complete by July 2021

ADM(RS) Recommendation

Management Action

CFINTCOM Action Item 3.1

Currently, approximately half of the instructors at CFMSI have received the Advanced Instructional Technics course. Every effort is made to provide the training to new personnel upon posting to the school; however, due to the high tempo of courses throughout the year, this has not always been possible. CFSMI is reviewing its calendar in order to better synchronize the provision of advanced instructional training; it will also examine additional professional development opportunities in order to improve the overall skills of its instructors.

CFSMI is completing the second year of a five year plan to implement the MESIP courses, phase out legacy courses, and rewrite all courseware. Significant additional financial and personnel resources have already been provided to CFSMI in order to implement this plan, and the baseline funding for this support beyond the five year plan will be the subject of future business plan submissions by CFINTCOM.

OPI: CF Int Group/COS

Target Date: Summer 2023

ADM(RS) Recommendation

Management Action

CFINTCOM Action Item 4.1

ADM(RS) Recommendation 4 and Key Findings 7 and 8 are directly related to DIER Problem Statement 2: Defence Intelligence does not function as an enterprise, andProblem Statement 3: The Defence Intelligence workforce must evolve. This effort will be conducted by the Director of Intelligence Production Management (DIPM), who is responsible for the Defence Intelligence Officer Recruitment Program and the SDIAQ. Broad consultation is already underway with OGDs and Five Eyes partners, which has led to a best practices and lessons learned exercise with the Five Eyes Enterprise. Courses and information sessions will be reviewed and some added to better align with requirements, in particular in focussing on the development of leadership and managerial skills for the EC-05, EC-06 and EC-07 levels. Particular attention will be paid to offer more iterations of courses, announced in advance, to answer the issue of a fast-paced environment and high volume of business. Online training options will be explored; online training is sometimes easier to enroll in than in a class training, when available time for training is constrained. ACDI is also leading efforts to increase work force understanding of Public Service staffing processes.

Close alignment with ACDI’s Human Resource Management Plan and the DIER MIP will be imperative. The latter is intended to develop a Defence Intelligence Human Resource Strategy for civilian employees that will address broader issues such as recruitment, retention, tradecraft, career progression and future workforce requirements. Intelligence Policy Officers will also be included in this review.

OPI: DIPM in consultation with DIER

OCI: ACDI, COS, DGIPP, CF Int Gp, L1 Defence Intelligence Stakeholders

Target Date: Analysis complete by July 2021; implementation complete by July 2022

ADM(RS) Recommendation

Management Action

CFINTCOM Action Item 5.1

ADM(RS) Recommendation 5 and Key Findings 9 and 10 are directly linked to the hiring of a Gender Advisor within the command. This responsibility is currently a secondary duty for the ACOS Ops J3. In order to continue supporting the implementation of the GBA+ policy within CFINTCOM activities as a whole, this position will need to be filled, but must be considered against all other staffing requirements within CFINTCOM. Meanwhile, CFINTCOM will continue to ensure all managers maintain an up-to-date Staffing Sub-Delegation for Managers qualification. All civilian staffing actions will continue to incorporate GBA+ considerations, as per ADM(HR-Civ) policy. Training will be provided at the lowest level to begin with – a course is currently under consideration for addition in the SDIAQ compendium – and GBA+ will be taken into account in all products from CFINTCOM. Further, we are consulting OGDs to incorporate their best practices and lessons learned.

OPI: COS/DIPM

Target Date: ongoing; target date for hiring Gender Advisor no later than September 2021, pending salary wage envelope (SWE) availability

Force Development

ADM(RS) Recommendation

Management Action

CFINTCOM Action Item 6.1

ADM(RS) Recommendation 6 and Key Findings 11 and 12 are directly related to DIER Problem Statement 5: We are underinvested in the force development of Defence Intelligence capabilities. DGIE/ACOS Dev is currently conducting a Functional Model Analysis and reviewing its FD processes and procedures. The CFINTCOM Functional Model Analysis aims to address this recommendation through the development of a CFINTCOM 10-year Growth Plan by July 2020. The functional review will also inform CFINTCOM’s return on the CFD-led Force Mix Structure Design Phase 2, and manage the prioritization and milestones associated with SSE-directed growth. Execution of the plan will follow the DTEP process on a year-by-year basis. Once successful, this growth will provide relief to the Command’s FD efforts. The DIER study will support the functional model and FD review and implementation through the provision of DI-related recommendations and synchronization with other DIER lines of effort.

OPI: DGIE/ACOS Dev in consultation with DIER

OCI: ACDI, COS, DGIPP, CF Int Gp, L1 Defence Intelligence Stakeholders

Target Date: Functional Model Analysis - July 2020, FD review and implementation – July 2021

Annex B—Evaluation Methodology and Limitations

1.0 Methodology

1.1 Overview of Data Collection Methods

The evaluation of Defence Intelligence gathered data from a number of sources in order to assess the program. The research methodology relied on both qualitative and quantitative research methods which, through data triangulation, ensured the validity of data collected for analysis. Based on evidence collected, the evaluation developed objective findings concerning the relevance and performance of the program.

Data collection methods used for the evaluation include:

- Literature and document review

- Key informant interviews

- Focus groups

- Observations

- Site Visit

- Surveys

1.2 Details on Data Collection Methods

1.2.1 Literature and Document Review

As part of the planning phase of the evaluation, a preliminary document review was conducted to develop a foundational understanding of defence intelligence and its components as well as determine the scope of the evaluation. This was expanded upon during the conduct phase of the evaluation, as other documents were examined to find data that would help in the assessment of the relevance and performance of the program. Documents included: government websites; government documents; program documents, including strategic policy and terms of reference; and government reports.

1.2.2 Key Informant Interviews

In the conduct of the evaluation, to ensure that broad perspectives of defence intelligence were included, it was deemed necessary to not only interview CFINTCOM but also other defence intelligence stakeholders across the DIE. Some interviewees were contacted afterwards for further clarification of comments or additional examples for the corroboration of evidence. Table B-1 lists organizations internal to CFINTCOM and other stakeholders interviewed throughout the conduct of the evaluation.

| Interviews internal to CFINTCOM | Interviews external to CFINTCOM |

|---|---|

|

|

Table B-1. Evaluation Key Informant Interviews. This table lists organizations interviewed during the conduct of the evaluation. They are distinguished by those internal to CFINTCOM and those external to CFINTCOM.

Table B-1 Details - Evaluation Key Informant Interviews.

1.2.3 Focus Groups

The evaluation undertook a number of focus groups to capture data from targeted populations within the program areas of the population. Three focus groups were conducted by the evaluation team with three key targeted groups: civilian trainers within CFINTCOM; military trainers at the CFSMI; and military trainees currently attending CFSMI. Additionally, the evaluation team attended focus groups conducted by the DIER team in support of their project. The DIER conducted three focus groups with targeted themes of governance and processes, people and technology.

1.2.4 Observations

The evaluation team was invited to attend two ICMB meetings. In doing so, the team was able to observe the activities of the committee to serve as first-hand experience corroborating comments on the ICMB from interviews and the survey.

1.2.5 Site Visit

During the conduct of the evaluation, the evaluation team went to Canadian Forces Base Kingston to visit CFSMI. While at CSFMI, the evaluation team was able to observe the infrastructure of the school as well as conduct a number of interviews and focus groups with school officials, staff and trainees.

1.2.6 Survey

To engage a broader number of stakeholders, the evaluation developed three surveys in English and French. The first survey was targeted for senior managers across the DIE, the second survey was targeted for trainers and trainees of defence intelligence, and the third survey was targeted for intelligence analysts (both military and civilian) across the DIE. The organizations from which the population of the survey was drawn included: CFINTCOM, CJOC, CANSOFCOM, NORAD, and the Environmental Commands (CA, RCAF, RCN).

The distribution of the survey relied on the point of contact who was identified through research or the DND Directory as one of the targeted individuals. These individuals were invited to respond to the survey and to also pass the survey on to relevant individuals targeted as described in the invitation.

Ultimately, the senior management survey had 19 total responses; the trainer and trainee survey had a total of 15 responses; and the intelligence analyst survey had a total of 162 responses. To note, the senior management survey had additional routing for issues concerning governance, personnel and FD according to their responsibilities. Governance and personnel respondents were 18 of 19 responses while FD respondents were 6 of 19 responses. Further, the evaluation team learned that none of the military trainees had received the survey due to a lack of access to the Defence Wide Area Network. As a result, a large focus group was conducted while the evaluation team visited CFSMI. Survey responses were corroborated against interview comments to ensure validity.

2.0 Limitations

Table B-2 describes the limitations and mitigation strategies employed in the evaluation process of the Program.

| Limitation | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|

Security Clearances: Due to the nature of defence intelligence, the evaluation was constrained to topics and data that were within the realm of unclassified. Classified information was excluded from the scope of this evaluation. Further, due to available clearances to the evaluation, Top Secret information was outside of scope. |

The evaluation team worked closely with the defence intelligence community to ensure that data remained in the unclassified domain. CFINTCOM and the other DIE stakeholders were as open and transparent as they could be, which facilitated successful data collection throughout the conduct of the evaluation. |

Questionnaire responses: The evaluation team had difficulty receiving completed questionnaires from stakeholders. In particular, the team did not receive enough responses from some parts of ADM(IM), which would have resulted in a skewed perspective of the organization. |

The team withdrew results collected from ADM(IM) and focused primarily on the questionnaire results from the service providers. Interview comments were relied upon to a greater extent for perspectives from ADM(IM) and corroborated with program data or other interviews for validity. |

Survey selection bias: Bias could arise based on the selection of the individuals or organizations chosen for the survey, which could skew survey results. |

All organizations that are members of the DIE were contacted for the purposes of the survey. Respondents were selected from intelligence units from within the respective member organizations. |

Interview bias: Bias could arise based on the subjective impressions and comments of interviewees, which could lead to biased views. |

Interview comments were corroborated with other sources to ensure validity. Interview notes were conducted by more than one individual to confirm understanding of discussions and decrease the likelihood of bias. |

Focus group bias: Bias could arise in the conduct of focus groups, where “group-think” or over-bearing voices dominate the discussion, leading to a lack of dissenting opinion. |

The evaluation took this potential risk into consideration during the conduct of the focus group and employed facilitation skills to ensure that a variety of participants had an opportunity to voice their opinions. Additionally, focus group comments were corroborated with individual interview comments for validity. |

Program Expenditure Availability: Due to the secure nature of defence intelligence expenditure and the respective clearance level of the evaluation, financial analyses could not be conducted. |

The evaluation states program expenditures but it does not go into an in-depth analysis. |

Table B-2. Evaluation Limitations and Mitigation Strategies. This table lists the limitations of the evaluation and the corresponding mitigation strategies.

Table B-2 Details - Evaluation Limitations and Mitigation Strategies.

Annex C—Logic Model

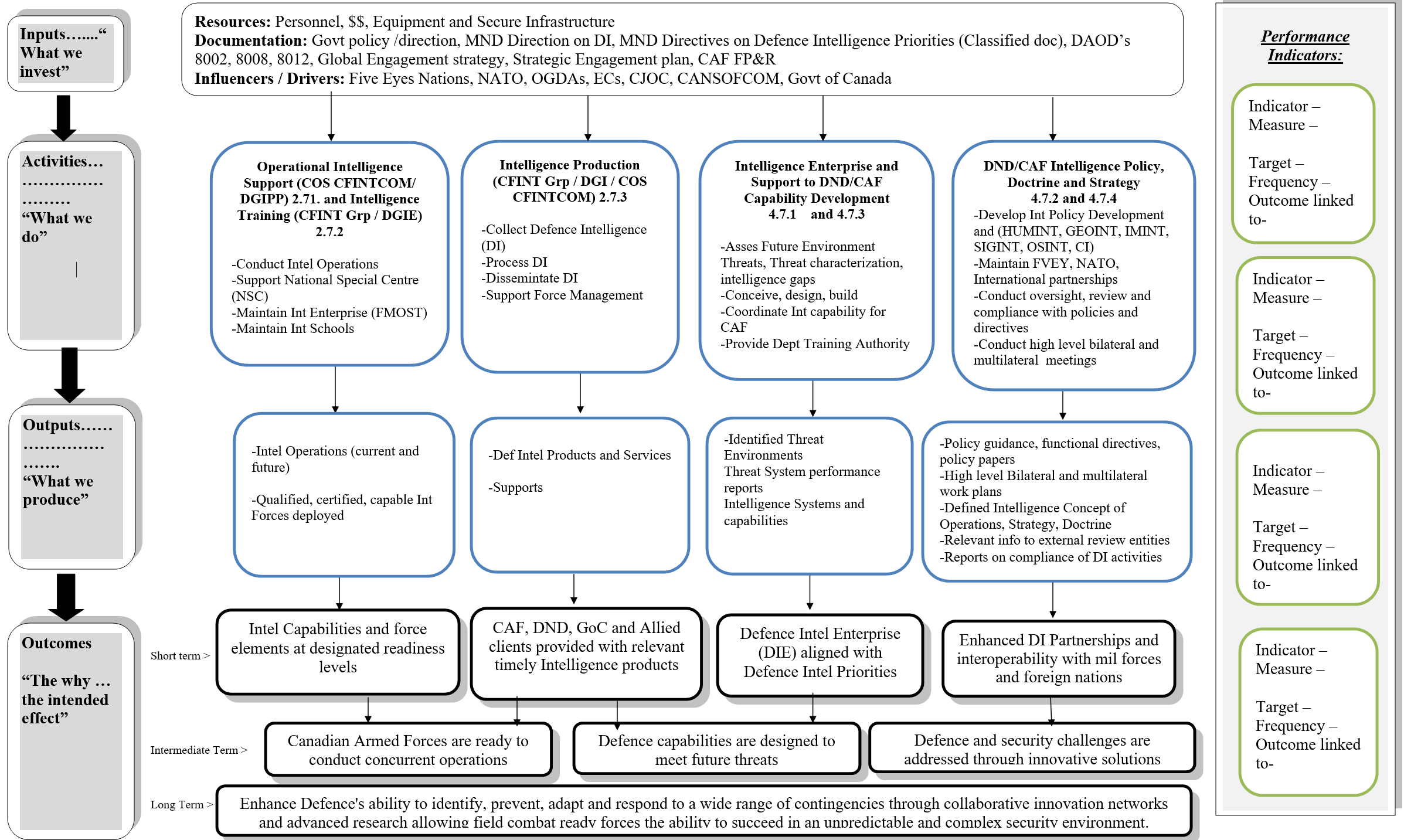

Figure C-1. Logic Model. This flowchart outlines the logic model for the evaluation.

Figure C-1 Details - Logic Model.

Annex D—Evaluation Matrix

Evaluation Issues/Question |

Performance Measures |

Key Performance Indicators |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

PERFORMANCE - (Effectiveness) Achievement of Expected Outcomes |

||||

Issues |

|

|

|

|

1.0 |

To what extent does the Defence Intelligence program employ the appropriate governance strategy? |

1.1 |

Evidence that the current governance structure of CFINTCOM enables effective governance of the Defence Intelligence program, including the location of CFIOG |

1. Evidence the governance structure effectively informs the CDI and senior intelligence officials of current and future force issues, ensuring sound decision making. |

2. Evidence that the governance structure effectively establishes strategic direction/framework to achieve DND/CAF/CFINTCOM goals. |

||||

3. Program manager perception that the current governance structure facilitates effective governance. |

||||

4. Evidence that the current organizational structure enables effective alignment of intelligence activities. |

||||

5. Perceived impact of CFIOG's being organizationally located outside of CFINTCOM on intelligence activities. |

||||

6. Evidence that the governance structure incorporates GBA+ considerations in intelligence activities. |

||||

1.2 |

Impact of the governance strategy in enabling the CDI to exercise an effective level of functional authority |

1. Evidence and alignment of Defence Intelligence functional guidance documents with DIE stakeholder intelligence activities. |

||

2. Evidence of program manager and CDI stakeholder perception that the CDI has a sufficient level of functional authority within the DIE. |

||||

3. CDI perception that they have a sufficient level of functional authority within the DIE. |

||||

1.3 |

Evidence the governance structure facilitates effective coordination across the DIE |