Evaluation of Land Equipment Acquisition Program

March 2023

1258-3-056 ADM(RS)

Reviewed by ADM(RS) in accordance with the Access to Information Act. Information UNCLASSIFIED.

Table of Contents

- Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Evaluation Scope

- Program Description

- Agile and Innovative Acquisition

- Technology innovation

- Fulfillment of Capability Gaps

- Costing Function

- Performance Measurement

- Conclusions

- Annex A: Key findings and recommendations

- Annex B: Management Action Plan

- Annex C: Methodology and limitations

- Annex D: Project funding and schedule profile

- Annex E: Project stakeholders

Alternate Formats

Assistant Deputy Minister (Review Services)

- ADM(Fin)

- Assistant Deputy Minister (Finance)

- ADM(Mat)

- Assistant Deputy Minister (Materiel)

- ADM(RS)

- Assistant Deputy Minister (Review Services)

- CA

- Canadian Army

- CAF

- Canadian Armed Forces

- CANSOFCOM

- Canadian Special Operations Forces Command

- CFB

- Canadian Forces Base

- CIO

- Chief Information Officer

- DASPM

- Director Armament Sustainment Programme Management

- DAVPM

- Director Armoured Vehicles Program Management

- DCED

- Director Cost Estimate Delivery

- DCSEM

- Director Combat Support Equipment Management

- DGLEPM

- Director General Land Equipment Program Management

- DLCSPM

- Director Land Command Systems Program Management

- DLEPS

- Director Land Equipment Programme Staff

- DLP

- Director Land Procurement

- DLR

- Director Land Requirements

- DND

- Department of National Defence

- DRI

- Departmental Results Indicators

- DRMIS

- Defence Resource Management Information System

- DSSPM

- Director Soldier Systems Program Management

- DSVPM

- Director Support Vehicles Program Management

- FOC

- Full Operational Capability

- FY

- Fiscal Year

- GBA Plus

- Gender-based Analysis Plus

- GPMG

- General Purpose Machine Gun

- IOC

- Initial Operational Capability

- IED

- Improvised Explosive Device

- IM

- Information Management

- ISED

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada

- ISS

- In-Service Support

- KPI

- Key Performance Indicator

- LEA

- Land Equipment Acquisition

- $M

- Millions of dollars

- MAP

- Management Action Plan

- MSP

- Munitions Supply Program

- NATO

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization

- NP

- National Procurement

- NCRR

- New Canadian Ranger Rifle

- OGD

- Other Government Department

- OCI

- Office of Collateral Interest

- OPI

- Office of Primary Interest

- PPA

- Preliminary Project Approval

- PSPC

- Public Services and Procurement Canada

- RAMD

- Reliability, Availability, Maintainability and Durability

- SAM

- Small Arms Modernization

- SPAC

- Senior Project Advisory Committee

- SRB

- Senior Review Board

- SSE

- Strong, Secure, Engaged

- SS (ID)

- Synopsis Sheet (Identification)

- TAPV

- Tactical Armoured Patrol Vehicle

- TB/TBS

- Treasury Board/Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

- VCDS

- Vice Chief of the Defence Staff

This report presents the results of the evaluation of the Land Equipment Acquisition (LEA) program, conducted during Fiscal Year (FY) 2021/22 by Assistant Deputy Minister (Review Services) (ADM(RS)) in compliance with the Treasury Board (TB) Policy on Results. The evaluation examines two case studies: Tactical Armoured Patrol Vehicle (TAPV) and General Purpose Machine Gun (GPMG) upgrades.

Program Description

The LEA program acquires, through the definition and implementation of approved capital equipment projects, new or modernized equipment required by the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) in response to evolving Defence requirements. The program is delivered under Director General Land Equipment Program Management (DGLEPM) under the authority of Assistant Deputy Minister (Materiel) (ADM(Mat)).

Scope

The report provides for a targeted assessment against key evaluation questions regarding program effectiveness, efficiency and use of performance measurement, focused on the latter phases of the acquisition process (Definition, Implementation and Closeout) related to acquisition of capital equipment within DGLEPM’s Land and Common equipment programs. The TAPV and GPMG upgrades projects were used as representative case studies of the LEA program.

Results

The evaluation identified notable successes; both projects are generally on budget, utilize Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA Plus) in planning, and are supported by a sound costing function. There are certain opportunities for improvement moving forward.

The evaluation identified a lack of awareness and utilization of agile procurement practices within both projects. There are also challenges in balancing the need for agile procurement with other policy requirements. For the TAPV project, static and overspecialized technologies were utilized without sufficient regard for modernization, which also impacts the agility of acquisition projects to effectively support evolving CAF operations. While GBA Plus factors are adequately considered during project planning and approval, there is a lack of tracking GBA Plus during equipment deployment.

The GPMG project is meeting CAF needs, while TAPV faces challenges in meeting evolving CAF strategic and long-term capability needs. Notable gaps include rigid/inflexible processes and insufficient consultation with key stakeholders needed to inform and adapt acquisition practices accordingly based on CAF needs. Both projects are behind schedule.

Overall, the costing function provides a value-added service, with elements of opportunities for improvement, such as insufficient embedding of costing analyst within projects. Finally, there is a lack of strategic operational performance information being collected. For example, TAPV performance information is limited to basic vehicle data, with a lack of robust operational performance data to inform deployment decision making. Issues were also identified with respect to standardized data collection and storage. These performance measurement challenges hinder informed and strategic decision making with respect to acquired equipment and ensuring it continues to meet CAF’s needs.

Overall Conclusions

The evaluation concluded that further promotion of agile procurement practices and consultation for input into acquisition projects is needed, along with more strategically focused performance measurement efforts and ensuring that GBA Plus is integrated into all phases of the acquisition process.

Recommendations

- Ensure a process for the management of consultation with end users, key stakeholders and external expertise for input into acquisition projects is in place.

- Enhance tactical and capability performance measurement efforts to better inform strategic and long-term decision making.

Evaluation Scope

Coverage and Responsibilities

The evaluation of the LEA program was conducted in accordance with the TB Policy on Results and the Department of National Defence (DND/)CAF Five-Year Departmental Evaluation Plan (FY 2017/18 to FY 2021/22). Its inclusion in the plan was endorsed by the Performance Management and Evaluation Committee in March 2021.

The evaluation focused on the activities related to acquisition of Major Capital equipment within DGLEPM’s Land and Common equipment programs.

Using five evaluation questions, the objective of the evaluation is to assess elements of the program effectiveness, efficiency and performance measurement through the use of two representative case studies of projects: TAPV and GPMG upgrades. The assessment focuses on the Definition, Implementation and Closeout phases of the projects’ lifecycle.

- To what extent were acquisition projects able to implement innovative procurement practices, such as agile procurement, and what are the challenges/barriers to effectively doing so?

- To what extent do the projects keep pace with technology and enable integration with allies?

- To what extent did the acquired equipment fill the original capability gaps?

- To what extent does the costing function enable effective and efficient planning and execution of projects, including alignment between resources and expected deliverables?

- To what extent does the program’s performance measurement framework enable collection, monitoring and reporting of data to adequately assess achievement of outcomes?

Two concurrent (2022) evaluations also examine equipment acquisition. The Thematic Evaluation of Acquisition Effectiveness examines equipment acquisition effectiveness across three DND/CAF Programs (Maritime, Land and Aerospace Equipment Acquisition), and the Evaluation of Acquisition Project Management examines agile/innovative acquisition and GBA Plus across all equipment acquisition programs.

Out of Scope

The following components were out of scope for this evaluation:

- Identification and Options Analysis Project Phases: These aspects were examined as part of the Land Force Development Evaluation, Integrated Strategic Analysis (2021) and Audit of Preliminary Requirement Development Process for Capital Equipment Projects (2019).

- Lifecycle Management Activities (e.g., maintenance, disposal).

- Governance: Aspects of governance, including general oversight and committees, will be covered under concurrent Director General Audit.

The evaluation used multiple lines of evidence collected through qualitative and quantitative research methods (see Annex C for methodology and limitations).

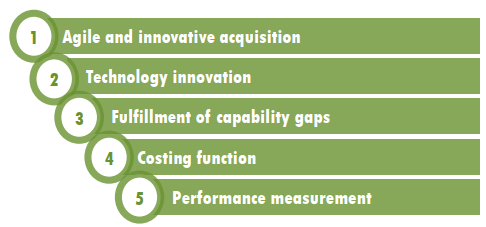

Findings were developed and themed based on the following categories:

Figure 1 Summary

The scope was developed in consultation with key stakeholders, including ADM(Mat), DGLEPM and the Canadian Army (CA). Guidance was also received from ADM(RS).

Program Description

The LEA program acquires, through the definition and implementation of approved capital equipment projects, new or modernized equipment required by the CAF in response to evolving Defence requirements. This program contributes to Core Responsibility 5 (Procurement of Capabilities): Procure advanced capabilities to maintain an advantage over potential adversaries and to keep pace with Allies, while fully leveraging defence innovation and technology. Streamlined and flexible procurement arrangements ensure Defence is equipped to conduct missions. The program is delivered under DGLEPM under the authority of ADM(Mat). In consultation with DGLEPM, the TAPV and GPMG upgrades projects were selected as case studies for the evaluation.

TAPV project overview

The main objective of the TAPV project is to provide a multi-purpose combat capability essential to the CA. The project is intended to field a modern fleet of modular general-utility armoured vehicles for use in domestic and expeditionary operations. The project is expected to deliver the capability within a total budget of $1,250M. The project reached full operational capability (FOC) in December 2019 and is now in the project Closeout phase, which is scheduled for completion in December 2022.

The TAPV serves reconnaissance and surveillance, security and armoured transport functions. The vehicle prioritizes crew protection, offering a high degree of survivability due to its downward-facing V-shaped hull armour plating. Equipped with a remote weapons system and optic and surveillance systems, the TAPV was originally intended to provide an evolutionary step from the RG- 31 Coyote reconnaissance vehicle that was ending its lifecycle. The TAPV was designed to take over the Coyote’s patrolling, liaison and VIP transport roles, and complement the Light Utility Vehicle Wheeled (LUVW/G-Wagon). The vehicle has been designed in two variants:

- A reconnaissance variant, with a crew of three and capable of transporting two passengers;

- A general utility variant, with a crew of three and capable of transporting three passengers.

GPMG upgrades project overview

The main objective for the GPMG upgrades project is to replace the remaining machine gun fleet with new, upgraded arms (C6A1). The GPMG Modernization Project will procure deliverables within a total budget of $110M. The Project is currently in Implementation phase, initial operational capability (IOC) has been achieved, and Project Closeout is currently slated for August 2024.

The C6A1 GPMG serves as a critical component of the small arms equipment of the CA, enabling all manner of small arms fire in the full spectrum of CAF operations. The weapon is an upgraded design of the Army’s existing C6 machine guns, which are Canadianized versions of the Belgian FN MAG, originally designed in the 1950s and widely utilized in North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) armies. The C6A1 GPMG is a belt-fed, fully-automatic, air-cooled, gas and spring-operated machine gun with a fast fire rate of 7.62mm NATO ammunition. It can be utilized either by dismounted infantry or mounted within or on top of a turret on a vehicle.

Additional details on project funding and schedule can be in found in Annex D, and Program stakeholders in Annex E.

Agile and Innovative Acquisition

FINDING 1: There is a lack of awareness and utilization of agile procurement within both project case studies.

Why it’s important

Canada’s defence policy: Strong, Secure, Engaged (SSE) commits to “implementing flexible new procurement mechanisms that allow Defence to develop and test ideas and the ability to follow through on the most promising ones with procurement.”

- The performance of Defence acquisition is a key enabler of CAF capabilities, and has received public/media coverage.

Agile procurement is a new way of procuring goods and services that employs an iterative approach, focussing on outcomes, using cross-functional teams, and collaborating with other government departments (OGD) and suppliers (definition by Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) and endorsed by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS)). This contrasts with the traditional “waterfall” method, which typically characterizes acquisition within DND, which tends to be less cooperative and flexible, has planning only at the beginning of the acquisition process, and relies on highly detailed technical requirements.

Lack of awareness

Document review, interviews and survey results indicate there is little to no guidance for project and operational personnel on how to implement agile procurement, and there is a lack of awareness of agile procurement concepts and practices.

56% of survey respondents disagreed or did not know if the concept of agile procurement was clearly articulated and well communicated by management, suggesting there is room for improvement.

Limited utilization

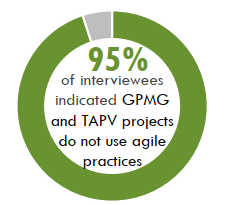

Evaluation evidence indicates minimal use of innovative or agile procurement practices.

- Survey results suggest there is room for improvement with respect to implementing agile procurement practices. 43% of respondents agreed that TAPV and GPMG projects implemented cross-functional teams, and only one third of respondents agreed the process was iterative, collaborative or outcome-focused.

- Limited evidence of innovation and agility was identified in the documentation reviewed.

- Site visits indicated that the TAPV project, in particular, lacks innovation and agility. Key issues are discussed on the following slide.

Figure 2 Summary

Barriers to implementing agile procurement

- Rigid and inflexible processes

- The project lifecycle is typically measured against standard policy requirements and budget/schedule milestones, without sufficient inclusion of alternative or innovative solutions.

- Interviewees indicated it is difficult to be innovative with layers of standard, interlaced and inflexible processes, particularly within the CA.

Figure 3. 60% of interviewees cited rigidity of processes as a primary challenge/barrier. Figure 3 Summary

60 % of interviewees cited rigidity of processes as a primary challenge/barrier. Both projects were described as a rigid process where phases require milestones to be met at an unrealistic pace, with staff turnover, lack of staff expertise in certain backgrounds, and significant red tape that prevents actual work/progress from occurring. These stepped approaches (e.g., reviews, costing) lead to purchasing “yesterday’s technology” and do not allow flexibility in the processes.

- Insufficient CAF consultation and testing for TAPV where the project could not advance, pivot or abort as required.

- Lack of incentives to explore innovative procurement practices, and a risk-averse culture within both projects.

- Extensive multi-departmental (e.g., PSPC and TBS) processes and approvals.

- Keeping pace with rapidly changing technology, and tracking project changes that may be required.

Address existing recommendation from the Acquisition Project Management evaluation (ADM(RS) 1258-3-057): “Explore and promote innovative acquisition practices and processes and decide how and when to apply agility and innovation.”

FINDING 2: Procurement policy requirements and guidance were adhered to, with oversight in place. However, there are challenges in balancing the need for agile procurement with other policy requirements.

Innovation in acquisition: the creation and application of new products, services and processes. It encompasses new technology as well as new ways of doing things. It can mean: keeping pace with technology; leveraging digital technologies acquisition; and enabling creative solutions.

Why it’s important

- Consistent and timely guidance and documentation are required for the successful implementation of agile and innovative acquisition practices.

- Limited agility and innovation within acquisition poses risks to operational capabilities.

- A balanced approach to risk and flexibility is necessary when applying the principles of agility and innovation.

- Iterative approaches should be considered when exploring and promoting innovative/agile acquisition practices to keep pace with evolving CAF needs and emerging technologies.

Balancing agility with other policy requirements and accountabilities

Document review, site visits and interviews indicate that environmental, GBA Plus, official languages and indigenous-related policy obligations of the time were considered as appropriate and in alignment with policy expectations. Appropriate governance bodies/committees are in place to ensure oversight.

75% of interviewees indicated that although processes are followed, projects still faced challenges implementing agile procurement practices, citing the aforementioned issues of lack of communication on what is meant by agile procurement, along with following established policies and procedures which tend to be very rigid. Consequently, complying with other policy requirements tends to supersede the implementation of agile procurement practices.

Encouraging agility amidst the myriad of policy and other requirements for which projects are accountable was also noted as challenging.

Interviewees indicated that a risk-based approach is not being used to streamline processes, citing a risk-averse culture within the organization and reiterating inflexible policy and processes.

“Our system is inherently risk averse, mainly due to transparency programs and requirements. Individuals are more afraid of their decisions being looked at with 20/20 hindsight so they don’t assume risk. Additional governance has been imposed, which affects policy requirements. There now exists a reticence to accept anything outside of what’s on paper when it comes to our contracts.”

Interviewee

FINDING 3: While GBA Plus factors are considered during project planning and approval, there is a lack of tracking/performance measures during deployment of equipment.

GBA Plus is an analytical process used to assess systemic inequalities and understand how diverse groups of women, men and gender diverse people may experience policies, programs and initiatives. GBA Plus includes not only gender but also intersectional considerations.

Why it’s important

- SSE commits DND to integrating GBA Plus into every step of a program or project lifecycle, such as the findings, impact, design options, budgeting, risk assessment and evaluation of project success.

- DND seeks to use GBA Plus as a tool to achieve greater equality within acquisition processes and projects.

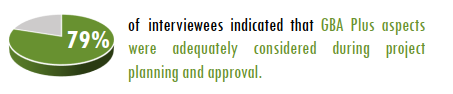

Document review, site visits and interviews indicate that GBA Plus considerations are in place, and in compliance with relevant policy, albeit not fully implemented throughout the acquisition process.

GBA Plus adequately considered early in the acquisition process

- There was solid support and consideration of GBA Plus during project planning and approval.

- GBA Plus factors were well documented and taken into account; particularly regarding the GPMG modifications included in the project, which were intended to enhance the ergonomics and ease-of- use of the weapon.

- Both TAPV and the GPMG utilize human factors engineering, with GBA Plus modulations written into contracting requirements and built into equipment modulations.

“GBA Plus is considered as part of the project and we are proud to use it as such .”

Site visit interviewee

Figure 4 Summary

This figure reflects the percentage of interviewees (79%) who indicated that GBA Plus aspects were adequately considered during project planning and approval.

Gaps in GBA Plus considerations later in the acquisition process

GBA Plus should not only be in early phases, but when assessed to be relevant, should be an ongoing and iterative process applied to inform every aspect of the project, from Identification to Closeout.

- Evaluation evidence indicates that awareness and use of GBA Plus tools and resources for contracting and project planning is sufficient, but less so during equipment deployment and usage monitoring.

- There was no documented evidence of GBA Plus, nor is there a formal tracking mechanism or performance measures in place to gauge performance, during deployment of equipment.

Address existing recommendation from the Evaluation of Acquisition Project Management (ADM(RS) 1258-3-057):

“Ensure accountability for GBA Plus in acquisition project management.”

Technology innovation

FINDING 4: For the TAPV Project, static and overspecialized technologies were utilized without sufficient regard for modernization.

Why it’s Important

- Keeping pace with emerging/innovative technologies is a key component of agile procurement, and helps CAF capabilities to meet evolving global circumstances.

- Insufficient modernization increases the risk of CAF capabilities becoming less relevant in multi-spectrum operations, reduces operational effectiveness in modern dynamic threat environments and limits interoperability with allied forces fielding modernized equipment.

TAPV Project – a niche role, yet overspecialized procurement

- The TAPV Project’s emphasis on Improvised Explosive Device (IED) protection for a specific theatre was of primary importance throughout the development of the vehicle, with overly specialized technologies incorporated into the project.

- Documentation, site visits and interviews indicate that the project was developed with little prioritization of adopting innovative technologies.

- The vehicle incorporated some effective technologies of its day; however, contract structures contributed to it being too specialized in its role and cannot be easily modernized or effectively used in a wider spectrum of operations that the CAF is required to conduct.

- Site visit and key informant interviewees raised concerns about the insufficient level of consultation with CA end users in the early stages of project development, as well as a lack of vehicle trials in a variety of environmental conditions.

- The TAPV contract is an inflexible arrangement with the vendor that impedes technological innovation for the vehicle.

- External consultations, in addition to end user consultations, did not adequately take place.

- The Army’s planning and operational expectations for the TAPV do not appear aligned with allied forces, and pose challenges for interoperability.

Additional Barriers for Keeping Pace with Technological Change

- Several respondents indicated that the primary barrier to the integration of new technologies in the projects was the length of the project lifecycle, with technological change outpacing the projects’ innovations of the day.

- Inflexible contract structures with vendors impedes modernization as deliveries of the initial requirements are the focus, rather than adapting to the needs of the Army.

GPMG Project – a simplified procurement of a proven design

- The upgraded GPMG improved upon the existing project by adding a number of weapon modifications and ancillary equipment designed to make the weapon more ergonomic, and upgradeable in the future.

- The weapon was tested in a series of user trials; however a greater variety of environmental conditions would have ensured a greater certainty in the weapon’s operational effectiveness for CAF end users.

- Where appropriate, consultation with allies did and currently takes place in planning and acquiring GPMG modifications.

36% of surveyed respondents disagreed that the projects have sufficient flexibility to enable the adoption of new technologies throughout project lifecycles.

“(You) want to field this capability, but don’t want to hold up its delivery to wait for a perfect integration of a new technology.”

Interviewee

Address existing recommendation from the Evaluation of Acquisition Project Management (ADM(RS) 1258-3-057):

“Explore and promote innovative acquisition practices and processes and decide how and when to apply agility and innovation.”

Fulfillment of Capability Gaps

FINDING 5: The TAPV achieved original requirements, but faces challenges in meeting evolving CAF strategic and long-term capability needs.

The TAPV acquisition fell behind evolving global strategic circumstances

- Despite some advantages, such as engaging dismounted targets and weak fortifications, evaluation evidence indicates that TAPV does not sufficiently meet the CAF’s long-term strategic needs.

- The majority of respondents consider the TAPV project to be overspecialized for a particular defence need (i.e., IED protection), rather than strategic land fleet needs in a modern global context, and is not fully aligned with the Army’s doctrine of balancing the armoured principles of Firepower, Protection and Mobility.

- Site visit and key informant interviewees reported that multiple TAPVs are not being used or are in bays for long-term maintenance, thereby limiting operational effectiveness and efficiency.

- Some CAF personnel interviewed expressed significant reluctance to operate the TAPV in any potential high-intensity combat environment, due to its vulnerabilities.

“We deliver to requirements, we don’t deliver to needs. We have to recognize that when there is a 10 year difference between requirement and need, requirement and need will not be the same within a changing environment.”

Interviewee

Challenges

There is a general perception from respondents that the TAPV is challenged to keep pace with long-term CAF needs. The perception is driven by the following feedback themes:

- Overly dependent on the sole-source provider, impacting operational readiness;

- Lack of diverse “real-world testing” (e.g., in different conditions/climates) before making procurement decisions; and

- Insufficient consultation with key stakeholders – particularly CAF operational personnel, the vendor and external experts (e.g., industry/academia) that could help identify lessons learned.

- Input from CAF operational personnel was not adequately solicited or considered during the selection and planning of the TAPV.

- Lack of a robust feedback process for CAF operational personnel to provide input and technical advice to help ensure continual improvement/lessons learned of the TAPV, and a cultural perception of being left to maintain a degrading vehicle.

“Project managers forget to do what is called user engagement. It’s fundamental but it’s often ignored. Project managers should have a plan to do user engagement. One of the key elements of the Project Management Plan is user engagement because it is validating what the industry is providing, with the user. Doing a cross check between industry and the user is fundamental on any procurement.”

Interviewee

A majority of interview respondents indicated that acquired equipment is not fulfilling the CAF’s capability gaps, or that they did not know.

FINDING 6: Overall, the upgraded GPMG is meeting CAF needs, although more time is needed to address initial quality control issues and to build performance data.

Evaluation evidence indicates that overall, the GPMG project is meeting CAF needs:

- Key informant and site interviewees, based on their experience, agree that the “Machine Gun is essential and is meeting core defence needs.” It is a critical weapon of the small arms fleet that is used in a full range of CAF operations. The new GPMG (C6A1s) is based on the original machine gun design with improved features such as:

- External gas regulator to control the rate of fire as needed.

- Durable polymer butt stock instead of the current wooden style.

- The weapons allow soldiers to attach pointing devices and optical sighting systems to help increase operational and tactical effectiveness.

- However, there does not appear to be a current capability gap analysis/study to confirm whether this machine gun is fully meeting CAF needs.

The GPMG is mostly a good news story, but there were some minor issues with parts specifications not matching vendor specifications on paper. There were some minor quality control issues (e.g., barrel extensions, certain misfires, clip spring weaknesses).

Site visit interviewee

While GPMG is meeting CAF needs, there were certain quality control/technical issues with some of the new GPMGs fielded to the CAF:

- Gas regulator: The weapons were returned to the vendor and fixed by the company. DND considers the issue now resolved.

- Barrel nut: The weapons were returned to the vendor and fixed by the company. DND considers the issue now resolved.

- Belt feed channel mechanism: The component was slightly out of specifications. The vendor was due to have the new feed channels manufactured by March 2022 for replacement in the field by CAF technicians.

- Firing pin: The firing pin protrusion was reported as being out of specifications. After the tolerance stack up of the various components was analyzed, a new measurement was recorded in the technical manuals and only a few firing pins were replaced.

“Une fois que tous les problèmes techniques liés au C6 va être régler, je suis convaincue que oui, cela va contribuer à répondre aux besoins des FAC.”

Interviewee

Work underway

Since August 2021, the vendor has adjusted some of its production processes which includes revising manufacturing work instructions, conducting enhanced employee education, and implementing additional weapon inspections prior to final packaging. Additionally, DND is conducting more on-site inspection and greater manufacturing oversight at the vendor facilities until deliveries are completed.

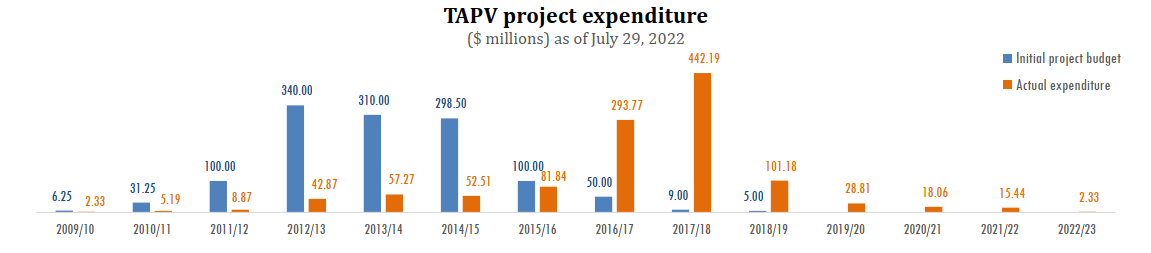

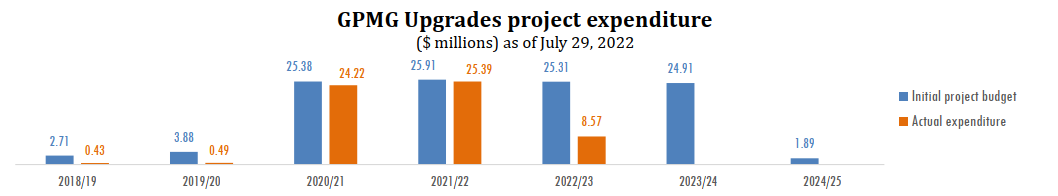

Project budget

Document and administrative/financial data review indicate that the TAPV and GPMG projects are generally within budget and expenditure authority.

Project schedule

In accordance with the Departmental Results Framework and Departmental Results Reports for the last three years (FY 2018/19 to FY 202021), 100% of capital equipment projects remain in most recent approved schedule and expenditure authority (DRI 5.2.2 and DRI 5.2.3).

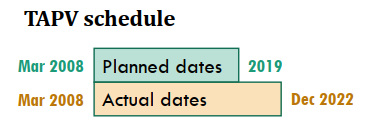

As for specific TAPV and GPMG projects, evaluation evidence indicates that projects were experiencing delays from the originally approved schedule, which impacts the ability to fully address CAF needs (e.g., operational readiness):

- The TAPV project experienced a delay against the 2012 approved schedule, primarily as a result of the need to return to the design phase following identification of the design challenges and as a result of production and quality issues. There are also delays in Project Closeout due to slippage related to completion of infrastructure upgrades and ammunition delivery.

- The GPMG project experienced a 2-year production/delivery delay due to delays in establishing the upgraded GPMG production line with the vendor.

46% of survey respondents indicated that, in general, acquired equipment has been rarely or almost never delivered on schedule.

See Annex D for details on project budget and schedule.

Costing Function

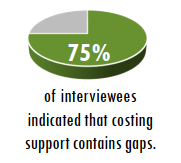

Evaluation evidence indicates that costing support for both projects overall is perceived as a positive value-added service:

- Survey results indicate that best practices have been applied to enable accurate costing throughout the project’s lifecycle.

- Although inflating costs over time, as projects take longer than originally planned pose costing challenges, particularly regarding in-service support costs, costing remained relatively stable and static for the two projects. The GPMG project benefited from a stable and well-established global market for military small arms, and the TAPV project utilized contingency funds to compensate for the unforeseen fluctuations in foreign exchange rate costs.

However, there are certain gaps in costing support:

- A high turnover of costing analysts that are not sufficiently embedded within projects, which is viewed as causing delays and with input that lacks a long-term strategic lens for financial analyses.

- A lack of flexibility to examine/analyze alternative costing options and vehicle modulation. It is not clear the extent to which costing analysis explored alternative vehicle features, capabilities and usages.

- A lack of a formal structure to develop and use a repository of lessons learned during the costing function, and costing feedback is typically restricted to immediate policy compliance/checklist, rather than long-term strategic considerations.

- Insufficient consideration of infrastructure, repair/parts supply chain and maintenance in the procurement and contracting process.

Insufficient costing resources were available during initial stages of TAPV, especially during times where multiple large projects are ongoing.

Interviewee

Figure 5 Summary

A third of interviewees suggested engaging industry early to gather initial costing information/estimates.

26% of survey respondents who commented on challenges/barriers affecting the costing function identified departmental shortcomings/delays as a main area of concern, which includes: policy and data mismatches regarding costing; a general lack of dedicated/embedded resources; high personnel turnover; a lack of effective planning. and a silo effect on costing efforts.

Support from TBS and PSPC is perceived as positive and useful, although lengthy in wait times.

46% of interviewees recognized there is close consultation between ADM(Mat) and Assistant Deputy Minister (Finance) (ADM(Fin)) in terms of costing analysis and corresponding quality; however, they often have to leverage more extensive costing support through the life cycle of projects from other entities such as PSPC.

38% of survey respondents agreed that there had been sufficient consultation with external experts. The remainder did not know or were neutral.

Work underway

The costing services provided by ADM(Fin) have matured in the years since GPMG and TAPV projects were launched, such as the use of a risk-driver method for capital acquisition projects, development and standardization of full life cycle costing templates, and alignment of DND costing practices to international standards.

The Department continues to evolve costing practices by making improvements to cost, schedule and risk uncertainty management, and assessing projects at earlier stages in project development. For example, DND introduced a new federal best practice related to contingency application, which is expected to produce better project and program outcomes by ensuring sufficient financial flexibility.

The costing function is committed to continual improvement, and will continue to evolve in response to requirements and stakeholders needs.

Performance Measurement

FINDING 9: There is a lack of strategic operational performance information to inform decision making.

Why it’s Important

- Effective performance measurement is key for supporting informed, strategic and long-term organizational decision making.

- Strategic operational performance information helps ensure acquired equipment continues to meet CAF needs, and supports agile procurement practices.

Insufficient Standardization

- Evidence and feedback indicate that both projects lacked a standardized performance measurement approach.

- Variations in Information Management (IM) practices between operational members and project teams led to difficulties in locating saved data and duplication of efforts in data storage.

- Interviewees identified challenges related to data storage and maintenance due to insufficient guidelines for uniform data storage practices.

- The projects utilized appropriate IM systems and practices; however, a lack of standardization and common practices meant that information was lost or stored improperly from person-to-person.

Ineffective Key Performance Indicators (KPI)

- Survey and interview evidence identified issues with the KPIs currently being collected. 83% of interviewees indicated a lack of effectiveness of KPIs for projects

- Interviewees indicated a lack of effective KPIs for the projects due to:

- A non-standardized approach to performance measurement.

- Insufficient long-term strategic perspective in performance measurement for both projects, as discussed in the adjacent project analyses.

- Often, KPIs were not specifically labeled as such, leading to inconsistent objectives and a general lack of standardization, according to program documents.

Figure 6 Summary

GPMG Project

- The modernized GPMG, as a proven design approaching full operational capability within the CA, has plentiful operational performance data demonstrating its effectiveness such as:

- Performance trials, as reflected in relevant program documents, to inform design improvements and identify manufacturing faults, which led to improved ancillary equipment for the GPMG .

- DRMIS is effectively used to store and access project documentation, according to interviewees.

TAPV Project

- TAPV performance information is limited to basic vehicle data, with a lack of strategic operational performance data to inform deployment decision making. Interviewees indicated this was primarily due to the inapplicability of the TAPV to current CA deployments and limited use by the CA.

- CAF personnel indicated their dissatisfaction that their input was not sought earlier in the project to address this inapplicability to multi- spectrum operations.

- As multiple TAPVs are in bays for long-term maintenance, it is unclear how operational decisions will be affected.

Conclusions

The purpose of the evaluation was to assess five key evaluation questions related to LEA program effectiveness, efficiency and performance measurement through the use of two representative project cases – TAPV and GPMG upgrades.

Reflecting the operational situation of the time, the TAPV prioritizes crew protection, offering a high degree of survivability due to its downward-facing V-shaped hull armour plating. The main objective for the GPMG project is to replace the remaining machine gun fleet with a new, upgraded arms.

The evaluation identified successes: both projects are generally on budget; utilize GBA Plus in planning; adhere to established project management requirements; and the costing function is providing a value-added service overall.

However, there are opportunities for improvement moving forward. The evaluation found that there was a lack of awareness and utilization of agile procurement practices. Additional gaps include rigid/inflexible processes and insufficient consultation to inform and adapt acquisition practices accordingly based on CAF needs.

The GPMG project is meeting CAF needs. The TAPV’s specialized design, although achieving requirements developed in 2010, faces challenges meeting evolving CAF strategic and long-term capability needs. Corresponding results further point to the importance of adequate consultation and input into acquisition projects.

While GBA Plus factors are considered during project planning and approval, there is a lack of tracking of results during equipment usage.

Enhanced performance measurement efforts would better inform strategic and long-term decision making. As well, certain opportunities for improvement were identified regarding the costing function.

The evaluation concluded that further promotion of agile procurement practices and consultation for input into acquisition projects is needed, along with more strategically focused performance measurement efforts and ensuring that GBA Plus is integrated into all phases of acquisition projects. These improvements will impact the ability of the CAF to adequately conduct missions based on evolving needs.

These findings are consistent with concurrent evaluations also undertaken in 2022 (e.g., Thematic Evaluation of Acquisition Effectiveness and Evaluation of Acquisition Project Management.)

Annex A: Key findings and recommendations

KEY FINDING |

RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|

AGILE AND INNOVATIVE ACQUISITION |

|

1. There is a lack of awareness and utilization of agile procurement within both project case studies. |

Address the following existing recommendations from the Evaluation of Acquisition Project Management (1258-3-057 ADM(RS)):

|

2. Procurement policy requirements and guidance were adhered to, with oversight in place. However, there are challenges in balancing the need for agile procurement with other policy requirements. |

|

3. While GBA Plus factors are considered during project planning and approval, there is a lack of tracking/performance measures during deployment of equipment. |

|

4. For the TAPV Project, static and overspecialized technologies were utilized without sufficient regard for modernization. |

|

FULFILLMENT OF CAPABILITY GAPS |

|

5. The TAPV achieved original requirements, but faces challenges in meeting evolving CAF strategic and long-term capability needs. |

1. Ensure a process for the management of consultation with end users, key stakeholders and external expertise for input into acquisition projects is in place. |

6. Overall, the upgraded GPMG is meeting CAF needs, although more time is needed to address initial quality control issues and to build performance data. |

|

7. Both the TAPV and GPMG are generally on budget, although behind schedule. |

|

COSTING SUPPORT |

|

8. Overall, the costing function provides a value-added service. |

|

PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT |

|

9. There is a lack of strategic operational performance information to inform decision making. |

2. Enhance tactical and capability performance measurement efforts to better inform strategic and long-term decision making. |

Table A-1 Summary

Annex B: Management Action Plan

ADM(RS) Recommendation

Management Action

- ADM(Mat), in collaboration with the Vice Chief of the Defence Staff (VCDS) (and the other implementers – ADM(IE) and Chief Information Officer (CIO) – as well as sponsors – RCN, CA, RCAF, Canadian Special Operations Forces Command (CANSOFCOM)) will review and update project management guidance/documentation and training processes, to ensure that the consultations are captured and the resultant decisions itemized in project documentation. Examples of documentation and training would include but are not limited to the following:

- Project Approval Course

- Defence Resources Management Course

- Project Approval Directive

Closure/Deliverable: The Management Action Plan (MAP) will be considered closed once project management/guidance documentation and training processes have been updated and communicated to project management teams across DND/CAF.

OPI: ADM(Mat)/Director Project Management Support Organization

OCI: VCDS/CA/RCN/RCAF/CANSOFCOM/ADM(IE)/CIO

Target Date: December 31, 2024

ADM(RS) Recommendation

Management Action

- The CA will continue the collection of information and feedback from Unsatisfactory Condition Reports, Operational Lessons Learned and Safety Technical Bulletins, which as separate and uncoordinated activities have been insufficient performance measurements. Through existing Army Equipment Working Groups and Army Capability Development Boards, and the Canadian Army National Procurement Oversight Committee, the CA will align equipment performance feedback with capability development and sustainment boards with a focus on longer term strategic impact.

- In conjunction with ADM(Mat), the establishment of a Continuous Capability Sustainment approach would assist with ensuring the continuous alignment of upgrades and funding associated with sustainment and changing strategic environments. As directed by the governance bodies, this would greatly help retain subject matter expertise, historical developments, and align ongoing support investments with the evolving strategic needs.

Closure/Deliverable: The MAP will be considered complete once a formalized equipment performance measurement and continuous capability development and sustainment mechanisms are in place, with the associated terms of references, performance measurement tracking system, and decision-making tools.

OPI: CA

OCI: ADM(Mat)

Target Date: December 2024 (a one-page status update to be provided at mid-term, approx. December 2023)

Annex C: Methodology and limitations

Evaluation methodology

The evaluation findings and recommendations were informed by multiple lines of evidence and qualitative and quantitative research methods collected throughout the conduct phase to strengthen rigour and ensure the reliability of information and data supporting findings. These lines of evidence were triangulated, and draft findings shared with program management as part of a collaborative process to ensure accuracy and impartiality. The research methodology used in the scoping and conduct of the evaluations are as follows:

Document and literature review, administrative and financial data review

A preliminary review of the foundational documents was

conducted during the planning phase, which supported developing a comprehensive understanding of the program and informed the development of the scope and the evaluation matrix. The review was expanded extensively during the conduct phase of the evaluation, and the program provided a database of planning, performance measurement, financial and Human Resources, and other documents that were requested for data gathering and analyses. The evaluation team reviewed over 200 documents, including: departmental administrative reports; program documents; program status reports; minutes of meetings; departmental plans; results reports; policies and mandates applicable to the program; and internal and external websites.

Key informant interviews

The evaluation team worked with a program liaison to identify interviewees. There was a total of 21 interviews conducted with a range of stakeholders including Army (Director Land Requirements (DLR 5 and DLR 6), DGLEPM (DASPM, DAVPM, DCSEM, DLCSPM, DLEPS, DLP, DSSPM, DSVPM), ADM(Fin) Chief Financial Management and DGCIPA/DCED/EDCCD). A number of program stakeholders had confidential discussions with the evaluation team. Interview data was thoroughly captured, which allowed a robust thematic analysis. The data was cross-referenced against other lines of evidence.

Survey

Two confidential and anonymous bilingual web-based surveys were developed and administered to different categories of respondents (ADM(Mat), Army and ADM(Fin) personnel). The surveys focused on assessing the effectiveness and efficiency of the program. They were developed using Snap Survey Software and conducted using the internal Defence Wide Area Network platform. The web survey links were distributed by email to a broad list of anonymous ADM(Mat) recipients from eight directorates and to specific ADM (Fin) recipients with knowledge and experience in the financial/costing aspects of capital projects such as TAPV/GPMG. The online survey for ADM(Mat) and Army personnel was live for six weeks (April 1st to May 13th, 2022). During this timeframe, one reminder email and one deadline extension notification email were sent. The response rate was ~ 15% (198/1326), reflecting the proportion of personnel having experience/involvement with the projects. The online survey for ADM(Fin) personnel was live for three weeks (June 6th to June 24th, 2022). During this timeframe, one reminder email was sent. One out of nine respondents completed the questionnaire.

Case studies and site visits

In order to capture fulsome and operational information pertaining to program, the evaluation team employed a case study approach which included conducting site visits to capture client and project staff responses. The evaluation team undertook three site visits in different regions: Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Gagetown (NB), CFB Edmonton (Alberta) and Le Régiment de Hull (Gatineau/QC). These locations were selected due to the unique regional and focused perspectives. The site visits included group workshops, an orientation and operations debrief tour for evaluators and private consultation periods for personnel.

Focus group interviews

Due to the pandemic, the evaluation team conducted only two focus group sessions to capture direct in-person information from ADM(Mat) (DAVPM) and CA (DLR 3 and DLR 5). The focus group was also followed up with confidential discussions that were requested by either some of the focus group participants or other stakeholders who were referred to the evaluation management by their colleagues to share their perspectives on some aspects of the evaluation.

Evaluation limitations

The limitations encountered by the evaluation and mitigation strategies employed in the evaluation process are outlined in the following table.

Limitations |

Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|

Pandemic impact: Due to the global pandemic and restrictions on travel, the evaluation undertook a moderate number of site visits. |

The evaluation team used multiple lines of evidence and conducted a larger than normal number of interviews. Additionally, a broad and in-depth review and analysis of program documents was performed. |

Low survey response rate: due to the fact that the survey questionnaire was sent out to as wide a range of recipients as possible, and the evaluation focused on staff involvement in two specific projects that were selected as case studies. |

This limitation was addressed by triangulating evidence from multiple sources and lines of evidence to inform the findings and formulate overall conclusions (e.g., interviews with stakeholders at varying levels, site visits workshops and program document review). |

Interview bias: Interviews might have included subjective impressions and comments, which could lead to biased perceptions. |

Interviewees were invited from a broad range of specialities and responsibilities, and data was supplemented from other lines of evidence. The evaluation team relied also on in-depth analysis of program documents, survey results, site visits and focus group interviews. |

Table C-1 Summary

Annex D: Project funding and schedule profile

The TAPV project has a funding envelope of $1,250M, and $126M of contingency, set by the terms of the Preliminary Project Approval (PPA) approved by TB on June 18, 2009. The TAPV project was launched in FY 2009/10 and was expected to be completed in 2019.

Figure D-1 Summary

Figure D-2 Summary

TAPV project |

in $ millions |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2009/10 |

2010/11 |

2011/12 |

2012/13 |

2013/14 |

2014/15 |

2015/16 |

2016/17 |

2017/18 |

2018/19 |

2019/20 |

2020/21 |

2021/22 |

2022/23 *** |

TOTAL |

Initial project budget * |

6.25 |

31.25 |

100.00 |

340.00 |

310.00 |

298.50 |

100.00 |

50.00 |

9.00 |

5.00 |

|

|

|

|

1,250 |

Actual expenditure ** |

2.33 |

5.19 |

8.87 |

42.87 |

57.27 |

52.51 |

81.84 |

293.77 |

442.19 |

101.18 |

28.81 |

18.06 |

15.44 |

2.33 |

1,153 |

Variance from Initial budget |

3.92 |

26.06 |

91.13 |

297.13 |

252.73 |

245.99 |

18.16 |

-243.77 |

-433.19 |

-96.18 |

-28.81 |

-18.06 |

-15.44 |

-2.33 |

97.33 |

Variance from Initial budget, in % |

63% |

83% |

91% |

87% |

82% |

82% |

18% |

488% |

4813% |

1924% |

|

|

|

|

|

Cumulative variance from Initial budget |

3.92 |

29.98 |

121.11 |

418.24 |

670.97 |

916.96 |

935.12 |

691.35 |

258.16 |

161.98 |

133.17 |

115.11 |

99.67 |

97.33 |

|

Cumulative variance from Initial budget, in % |

62.7% |

79.9% |

88.1% |

87.6% |

85.2% |

84.4% |

78.8% |

55.9% |

20.7% |

13.0% |

10.7% |

9.2% |

8.0% |

7.8% |

|

Table D-1 Summary

Notes: * Source: C6 Charter Update V3 Nov 18 (p.7) and C6 GPMG Cost Concurrence Letter - Final Signed (p. 1); ** Source: Fin information, 2022_07_29 (PYE Expenditures with EBP); *** FY 2022/23 Actual expenditure is what is currently spent as of 29 July 2022.

Figure D-3 Summary

Milestone |

Planned Date * |

Currently Scheduled |

Actual Date |

Variance from Planned date |

Reason |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

SS (ID) |

26 Mar 2008 |

- |

|||

2 |

SPAC Approval of Procurement Strategy |

Nov 2008 |

14 Nov 2008 |

- |

||

3 |

Options Analysis PPRA Approved (V1.0) |

Jun 2009 |

26 May 2009 |

- |

||

4 |

PMB Approval of Definition Phase |

Jun 2009 |

2 Jun 2009 |

- |

||

5 |

PPA |

Jun 2009 |

18 Jun 2009 |

- |

||

6 |

Effective Project Approval (EPA) |

Summer 2011 |

7 Jun 2012 |

1 year |

||

7 |

Acquisition & ISS Contracts Awarded |

Fall 2011 |

7 Jun 2012 |

< 1 year |

||

8 |

IOC |

2013 |

22 Aug 2017 |

4 years |

Add-on armour kits have not been delivered as originally planned. |

|

9 |

FOC |

2015 |

30 Oct 2020 |

5 years |

Completion of LCSS procurement, C6 procurement, Weapons Effect Simulator, Infrastructure upgrades. |

|

10 |

Effective Project Completion (EPC) |

30 Oct 2020 |

||||

11 |

Project Closeout |

2019 |

31 Dec 2022 |

3 years |

Slippage related to delivery of EMI Vanner Enclosures, completion of Infrastructure upgrades (Meaford), and delivery of 76mm Smoke Grenades. | |

Table D-2 Summary

Note: * Source: TAPV Project Charter May 2009; TAPV Project Charter Jan 2019. Other sources: TAPV Brief Sep 13 2021; TAPV SRB Winter 2020; TAPV SRB Apr 2017.

The expenditure authority for the GPMG Upgrades project is ~$110M (risk-adjusted, net of tax). Plans to replace the GPMG fleet started as early as 2007 with the Small Arms Replacement Project II project, which evolved into a more focused Small Arms Modernization (SAM) project. The SAM project was broken down into four distinct projects over time to fit within the Investment Plan. The modernization of the GPMG was programmed in the SAM 1 project. On February 25, 2014, the Defence Capability Board approved the SAM 1 Business Case Analysis. Shortly afterwards, the SAM 1 project was split into two projects, including the GPMG Modernization project. The project is expected to be completed in FY 2022/23.

Figure D-4 Summary

Figure D-5 Summary

GPMG Upgrades project |

in Budget Year $ |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Previous Years Expenditures (PYE) |

2018/19 |

2019/20 |

2020/21 |

2021/22 |

2022/23 *** |

2023/24 |

2024/25 |

TOTAL |

|

Initial project budget * |

- |

2,713,784 |

3,880,175 |

25,384,851 |

25,913,521 |

25,305,171 |

24,905,762 |

1,890,567 |

109,993,831 |

Actual expenditure ** |

- |

430,382 |

490,432 |

24,220,379 |

25,393,156 |

8,567,093 |

59,101,442 |

||

Variance from Initial budget |

2,283,402 |

3,389,743 |

1,164,472 |

520,365 |

16,738,078 |

24,096,060 |

|||

Variance from Initial budget, in % |

84% |

87% |

5% |

2% |

66% |

||||

Cumulative variance from Initial budget |

2,283,402 |

5,673,145 |

6,837,617 |

7,357,982 |

24,096,060 |

||||

Cumulative variance from Initial budget, in % |

84% |

86% |

21% |

13% |

29% |

||||

Table D-3 Summary

Notes: * Source: C6 Charter Update V3 Nov 18 (p.7) and C6 GPMG Cost Concurrence Letter - Final Signed (p. 1); ** Source: Fin information, 2022_07_29 (PYE Expenditures with EBP); *** FY 2022/23 Actual expenditure is what is currently spent as of 29 July 2022.

Figure D-6 Summary

Milestone |

Planned Date * |

Currently Scheduled |

Actual Date |

Variance from Planned date |

Reason |

Table color coding: |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

SS (ID) |

8 June 2011** |

- |

||||

2 |

Project Charter (SAM 1) |

Apr 2013 |

12 Jul 2013** |

- |

|||

3 |

SAM SORs |

Jun 2013 |

27 Jun 2013** |

- |

|||

4 |

SAM1 C6A1 GPMG Business Case Analysis |

19 Mar 2014** |

Business Case Analysis approved with caveat to split SAM 1 to C6 GPMG Mod and NCRR with priority going to NCRR. | ||||

5 |

Final Decision on C6 GPMG Mod Procurement Strategy |

17 Mar 2017** |

Contracting Authority Approval from TB for the sole source contract to the vendor through the Munitions Supply Program (MSP) was granted. |

||||

6 |

Project Approval (Definition) - Waived |

Jun 2014 |

25 Jan 2018*** |

3.5 years |

Delays in establishing the C6A1 (C6 Flex) production line with the vendor (under the MSP/sole source supplier). The GPMG upgrades project requested to skip definition and move directly into implementation as there is no definition work required. |

||

7 |

Project Approval (Imp) |

Jun 2016 |

27 Apr 2018*** |

~ 2 years |

|||

8 |

Contract Award |

Aug 2016 |

23 Jan 2020*** |

3.5 years |

PSPC requested to delay contract award from Apr 1, 2019 to Nov 2019. |

||

9 |

IOC |

Aug 2019 |

26 Aug 2020*** |

1 year |

Overall on schedule |

||

10 |

FOC |

Aug 2022 |

28 Feb 2024*** |

1.5 years |

Delay 1 year or less |

||

11 |

Project Closeout |

Nov 2022 |

30 Aug 2024*** |

~ 2 years |

Delay +1 year |

||

Source: * 2013-04-25 SAM 1 SRB Presentation and GPMG Project Charter (SAM_1) (p. 11); ** C6 Mod 10 Nov 2017 SRB Presentation; *** C6 GPMG Modernization: DRMIS Project Details, 25 July 2022.

Table D-4 Summary

Detailed project schedule information

TAPV delays

- RAMD 1 testing

- In August 2014, RAMD 1 testing (Jul 2013 - Aug 2014) was suspended due to significant and numerous technical issues experienced with test vehicles.

- Program returned to design phase, with increased emphasis on component analysis and interrelated stresses, and supportive testing to validate assumptions prior to formal qualification testing.

- IOC

- IOC delayed, as add-on armour kits have not been delivered.

- FOC

- Completion of the following will likely lag FOC: LCSS procurement, GPMG procurement, Weapons Effect Simulator, Infrastructure upgrades. Transfer as part of Effective Project Closure.

- Project Closeout

- Delays in Project Closeout due to slippage related to delivery of EMI Vanner Enclosures, completion of Infrastructure upgrades (Meaford), and delivery of 76mm Smoke Grenades.

GPMG delays

- Production / Delivery

- The National Procurement (NP) Initiative was scheduled to be completed in December 2017 but has been delayed by 2 years due to delays in establishing the C6A1 (C6 Flex) production line with the vendor (MSP/sole source supplier). This has resulted in a 2-year production/delivery delay for the GPMG upgrades project, as delivery for the NP initiative must be completed first.

- Contract Award

- PSPC requested to delay contract award until Nov 2019. Delays in Project Closeout due to slippage related to delivery of EMI Vanner Enclosures, completion of Infrastructure upgrades (Meaford), and delivery of 76mm Smoke Grenades.

Annex E: Project stakeholders

DND/CAF: Assistant Deputy Minister Materiel (ADM(Mat)), Canadian Army (CA), Canadian Special Operations Forces Command (CANSOFCOM), Canadian Joint Operations Command (CJOC), Strategic Joint Staff (SJS), Chief of Force Development (CFD), and Assistant Deputy Minister Finance (ADM(Fin)).

Other Government Departments (OGD): PSPC, Innovation, Science, and Economic Development Canada (ISED), TBS

TAPV and GPMG Project Stakeholders

DND/CAF

- Commander, CA

- DLP

- DGLEPM

- PCO

- DGMPD

- DGMSSC

Industry

- Contract Partners/Vendor

- TAPV

- GPMG

See next slide for a description of stakeholder roles and responsibilities.

Roles and Responsibilities

DND/CAF Stakeholders

- ADM(Mat) - ADM(Materiel) is a central service provider and the Functional Authority for the Land Equipment Acquisition Program, responsible for defence materiel liaison and coordination with other departments, governments and interdepartmental organizations.

- ADM(Fin) – ADM(Finance) provides financial support services and advice to enable sound decision making and accountability across the department.

- CA, RCN, RCAF, CANSOFCOM are clients/project sponsors for equipment or services and are the Functional Authorities for defining the operational requirements for the capability to be implemented, and for confirming that the delivered capability satisfies the specified requirements.

- CFD – Chief of Force Development provides guidance and support for project development in the Identification and Options Analysis phases.

- C Prog – Chief of Programme provides policy and guidance for projects in the Definition, Implementation and Closeout phases.

- DLP – Director Land Procurement provides procurement, contracting and materiel management support for both the Division’s National Procurement and capital expenditures throughout all steps of the acquisition process.

- DGLEPM – Director General Land Equipment Program Management is the program official and delivery agent.

- PCO – Program Control Office provides coordination support for three functions: program performance management; change management; and communications related to acquisition projects.

- DGMPD – Director General Major Project Delivery is a capability delivery organization for major projects over $100 million.

- DGMSSC – Director General Materiel Systems and Supply Chain provides and manages both the Materiel Acquisition and Support framework and the Supply Chain to deliver optimized materiel support to CAF operations and Departmental activities.

Other Government Departments

- PSPC is the principal Functional Authority for the contracting of goods and services for the Government of Canada (e.g., leads the stakeholder and industry engagement before and during the procurement process; develops the procurement strategy; leads the solicitation process; oversees the technical benefits and price evaluation; and manages the resulting procurement, contract and vendor performance).

- ISED administers the Industrial and Technological Benefits Policy; makes recommendations on the application of the policy to procurements; and determines evaluation criteria intended to leverage economic benefits from resulting contracts and export components of those criteria.

- TBS is involved at the third stage (Definition) of the equipment acquisition process, and is responsible for determining if the project meets Program Management Board approval, as well as preparing a Corporate Submission to the Minister of National Defence or TB to receive expenditure authority to proceed to the Implementation stage.