Evaluation of Land Readiness

PDF Version

Assistant Deputy Minister (Review Services)

Departmental Evaluation Committee Meeting

November 2016

1258-228 (ADM(RS))

Reviewed by ADM(RS) in accordance with the Access to Information Act. Information UNCLASSIFIED

Table of Contents

-

Acronyms and Abbreviations

-

Executive Summary

-

1.0 Introduction

-

2.0 Findings and Recommendations

-

Annex A—Management Action Plan

-

Annex B—Evaluation Methodology and Limitations

-

Annex C—Logic Model

-

Annex D—Evaluation Matrix

-

Annex E—Key Training Elements of the Land Readiness Program and CA Organizations

-

Annex F—Comparative Analysis

- ADM(IE)

-

Assistant Deputy Minister (Infrastructure and Environment)

- ADM(IM)

-

Assistant Deputy Minister (Information Management)

- ADM(Mat)

-

Assistant Deputy Minister (Material)

- AEV

-

Armoured Engineering Vehicle

- ARCG

-

Arctic Response Company Group

- ARV

-

Armoured Recovery Vehicle

- BG

-

Battle Group

- Bde

-

Brigade

- BCT

-

Brigade Combat Team [U.S. Army]

- Bn

-

Battalion

- CA

-

Canadian Army

- CAX

-

Computer Assisted Exercise

- CBG

-

Canadian Brigade Group (Res F)

- CCA

-

Commander Canadian Army

- CDS

-

Chief of the Defence Staff

- CJOC

-

Canadian Joint Operations Command

- CMBG

-

Canadian Mechanize Brigade Group (Reg F)

- CMTC

-

Canadian Manoeuvre Training Centre

- CPX

-

Command Post Exercise

- CT

-

Collective Training

- DGLEPM

-

Director General Land Equipment Program Management

- FG

-

Force Generation

- FTE

-

Full Time Employee

- FoV

-

Family of Vehicles

- FP&R

-

Force Posture and Readiness

- FY

-

Fiscal Year

- HR

-

High Readiness

- HQ

-

Headquarters

- IRU

-

Immediate Response Unit

- IT

-

Individual Training

- LR

-

Land Readiness

- MR

-

Maple Resolve (HR confirmation exercise)

- MRP

-

Managed Readiness Plan

- O&M

-

Operations and Maintenance (budget)

- Op

-

Operation

- PAA

-

Program Activity Architecture

- RCAF

-

Royal Canadian Air Force

- RCN

-

Royal Canadian Navy

- RP

-

Real Property

- RTHR

-

Road to High Readiness

- TBG

-

Territorial Battalion Group (Res F)

- TF

-

Task Force

- VOR

-

Vehicle Off-road Rate

- WoG

-

Whole of Government

Overall Assessment

- There is an ongoing need for the Land Readiness Program that is the foundation of the Canadian Army. The program is aligned with the roles, responsibilities and priorities of the federal government and the DND/CAF.

- The CA Regular Force (Reg F) has been able to meet its readiness requirements, and has demonstrated its effectiveness across the full spectrum of operations ranging from disaster relief to combat. ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓

- The CA Reserves are ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓

- The Land Readiness Program is assessed to be operating in an economical manner as it identifies efficiencies to preserve its ability to sustain operational readiness.

Executive Summary

This report presents the results of the evaluation of the Land Readiness Program conducted by the Assistant Deputy Minister (Review Services)

(ADM(RS)). This evaluation is a component of the Department of National Defence (DND)/Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) Five-Year Evaluation Plan (FY 2013-14 to 2017-18). The Treasury Board (TB) Policy on Evaluation (2009) was rescinded 1 July 2016 and replaced by the new Policy on Results. Since the Policy on Results was only effective as of 1 July 2016, this evaluation was carried out in accordance with the Policy on Evaluation. As per the former TB policy, the evaluation examines the relevance and performance of the Land Readiness Program from FY 2010-11 to 2014-15.

Program Description

The Land Readiness Program is the responsibility of the Canadian Army (CA). The CA’s mission is to provide the Government of Canada with combat-capable, multi-purpose land forces. This program will generate and sustain scalable, agile, responsive, combat capable land forces that are effective across the spectrum of conflict, from peacekeeping and nation building to war fighting. This is accomplished by bringing land Forces to a state of readiness for operations, assembling and organizing land personnel, supplies, and materiel as well as the provision of individual and collective training to prepare land forces to defend Canadian interests domestically, continentally and internationally.1 Annual program expenditures are in excess of $3 billion.2

Relevance

The evaluation determined that there was a continued need to generate and employ land forces, which is the CA, as the CAF’s lead element across the full spectrum of land operations ranging from domestic humanitarian and disaster relief to international combat missions. The Land Readiness Program is aligned with federal government and departmental roles and responsibilities within the National Defence Act. As well, the CA has made a significant contribution to the federal government and departmental priorities of defending Canada, protecting Canadians at home and abroad, and making a highly visible and significant contribution to a safer and more secure world.

Performance

The Land Readiness Program has consistently delivered well trained and prepared CA elements when assigned to operations ranging from domestic relief or security operations, to international combat missions as evidenced by their performance. That said, the ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ such as the combat mission in Afghanistan and deploying Forces to a crisis elsewhere in the world for shorter periods of time, including the current CAF operations in Eastern Europe. To date the CA has always been able to meet their operational demands.

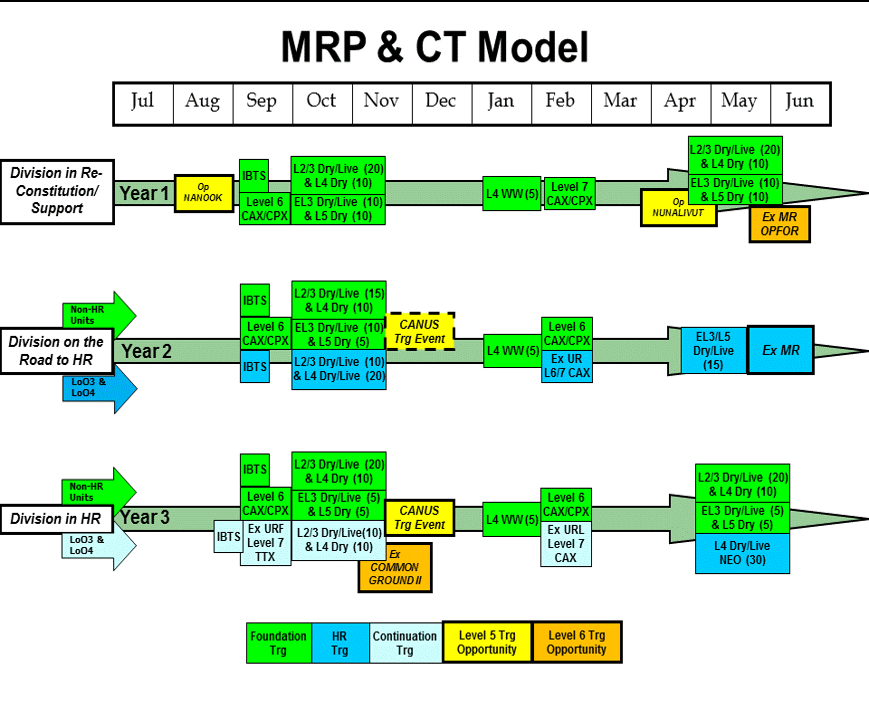

Land Readiness Program expenditures, along with the Defence budget, have declined over the period of the evaluation, with the exception of FY 2011-12, when the land and other readiness programs received additional funding. In the case of the CA, the increase reflected a peak in activity as it transitioned from the Afghanistan combat mission in Kandahar to the training mission in Kabul. Overall, the land readiness budget declined over the period FY 2011-12 to 2013-14, forcing the CA to seek economies and efficiencies to meet the land readiness requirements prescribed in the Chief of Defence Staff’s Force Posture and Readiness (FP&R) directives. A key element of this was revising the readiness cycle for the three principle CA divisions and their respective Reg F Canadian Mechanized Brigade Groups (CMBGs) from the 18 month cycle employed during Afghanistan operations to a post-Afghanistan cycle of 36 months. As well, commanders were directed to seize opportunities to maximize collective training opportunities between units, and elements of the Reg F and Reserves.

Looking ahead, the CA will be under increasing resource pressures, particularly in its Operations and Maintenance (O&M) budget, further stressing its ability to achieve its required readiness. As well, required equipment availability and serviceability is becoming increasingly difficult before the delivery of new combat and utility vehicles, having a further impact on the CA’s ability to achieve its required readiness.

Key Findings and Recommendations

Findings

Key Finding 1: There is an ongoing and future need for land readiness for the Canadian Army to be prepared to conduct operations in support of Canada, Canadians, and Canadian national interests.

Key Finding 2: There is alignment between the generation and delivery of the Land Readiness (LR) Program with departmental and federal roles and responsibilities.

Key Finding 3: The generation and delivery of land readiness is consistent with federal government and the DND / CAF roles of defending Canada, defending North America and contributing to international peace and security.

Key Finding 4: The LR Program has met all actual operational requirements to-date; however certain ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓in the support trades and enablers, such as the intelligence and signals trades.

Key Finding 5: The LR Program is ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓to the required state of readiness for Reserve specific tasks based on personnel numbers and availability in the absence of an operational mission.

Key Finding 6: ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓

Key Finding 7: The CA’s readiness for Arctic Operations is ▓ ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓for those operations.

Key Finding 8: Current CA ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓

Key Finding 9: ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓

Key Finding 10: The Army has demonstrated its effectiveness across the full spectrum of operations from disaster relief and humanitarian operations to combat.

Key Finding 11: The CA operational capability in the Arctic remains in development and its mobility and sustainability in Arctic operations ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓

Key Finding 12: The CA has clearly demonstrated its ability to lead and conduct a major international operation for an extended period during its deployment to Op ATHENA.

Key Finding 13: CA operations with other government departments (OGDs) would be further enhanced through greater engagement with civil authorities / agencies in planning and exercises to improve familiarity and interoperability.

Key Finding 14: The CA has demonstrated an effective response capability to a variety of crisis in the world as part of WoG disaster relief operations as well as allied operations.

Key Finding 15: Reduced financial and material resources have driven the CA to successfully use available resources more efficiently.

Key Finding 16: There has been some degradation of the CA infrastructure portfolio as a result of the CA prioritizing available funding to other requirements.

Key Finding 17: The CA effectively employs a broad range of data to inform financial and other resource decisions and continues to develop its Performance Measurement Framework.

Key Finding 18: The Land Readiness Program is assessed to be an affordable program.

Key Finding 19: The CA has effectively maintained a high readiness output while its budget has been reduced.

Key Finding 20: The CCA has introduced initiatives to mitigate funding pressures across the Army.

Key Finding 21: The CA provides a relatively efficient and economical Land Readiness Program (Army) in comparison to the armies of some of Canada’s closest allies.

Recommendations

ADM(RS) Recommendation 1: The CA continue current efforts to increase the deployability level of available personnel through the Canadian Army Integrated Performance Strategy (CAIPS) and other similar initiatives to enhance the personal readiness and resilience of individual soldiers. OPI: CCA Office of Collateral Interest, OCI: CMP

ADM(RS) Recommendation 2: The CA work with CMP to address ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓and enhanced Reserve recruiting, while building on the success of well manned and supported Reserve units and maintaining less sustainable units until such time as those units can demonstrate growth potential. OPI: CCA, OCIs: Chief of Military Personnel (CMP), Chief Reserves (C Res)

ADM(RS) Recommendation 3: The CA continue to implement and refine the CA Equipment Readiness Strategy to achieve CA VOR targets. OPI: CCA, OCI: ADM(Mat) / DGLEPM

ADM(RS) Recommendation 4: The CA work with ADM(Mat) and ADM(IE) to document current ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ and develop a plan to address ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ that are being used to warehouse and repair new equipment and to enhance equipment availability for training and operations. OPI: CCA,

OCI: ADM(Mat) / DGLEPM and ADM(IE)

ADM(RS) Recommendation 5: The CA continue to rationalize and consolidate its infrastructure. Office of Primary Interest (OPI): Commander Canadian Army (CCA), OCI: ADM(IE)

ADM(RS) Recommendation 6: The CA continue development of a comprehensive Performance Measurement Framework and activity based accounting, leveraging divisions’ “best practices” as appropriate. OPI: CCA

Note: Please refer to Annex A—Management Action Plan for the management responses to the ADM(RS) recommendations.

1.1 Context for the Evaluation

This report represents the results of the evaluation of the Land Readiness (LR) Program conducted by ADM(RS) between December 2014 and April 2016 in compliance with the TB Policy on Evaluation (2009). As per the TB policy, the evaluation examines the relevance and performance of the program over a five year period, FY 2010-11 to 2014-15.

There have been previous evaluations of the LR Program as follows:

- CRS Evaluation: Perspectives on Vanguard / Main Contingency Force Readiness and Sustainment, October 2004. This evaluation noted deficiencies in the Army training and shortfalls in equipment, including vehicles; and

- Evaluation of Land Force Readiness and Training, March 2011. This evaluation noted that the Afghanistan mission stressed the Army’s capacity in terms of both personnel and equipment resources, and posed significant sustainment challenges, but the Canadian Army (CA) demonstrated effectiveness across the full spectrum of operations.

This evaluation was supported by an advisory group comprised of senior staff of the Commander Canadian Army (CCA). The advisory group was consulted regarding the program logic model, evaluation matrix, and sources of information, and provided feedback on the draft report.

1.2.1 Program Description

The CCA has functional command of the CA and is responsible for the LR Program that is embodied in the CA. LR is accomplished by assembling and organizing land personnel, supplies, and materiel as well as the provision of individual and collective training to prepare land Forces to defend Canadian interests domestically, continentally and internationally3.

The CA is the land component and largest element of the CAF, comprised of approximately ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓4

Reg F and Reserve operational units are organized in four CA Divisions, formerly identified as Land Force Areas, across the western, central Quebec, and Atlantic regions of the country as follows:

- 3rd Canadian Division (Cdn Div), formerly Land Forces Western Area, with Headquarters (HQ) in Edmonton;

- 4th Cdn Div, formerly Land Forces Central Area, with HQ in Toronto;

- 2nd Cdn Div, formerly Land Forces Quebec Area, with HQ in Montreal; and

- 5th Cdn Div, formerly Land Forces Atlantic Area with HQ in Halifax.

Since the end of operations in Afghanistan, each of the CA divisions above (less the 5th Cdn Div) provide the basis of the CA’s Task Forces (TFs) and go through a three year readiness cycle depicted in Figure E-1 at Annex E. In addition to their regular readiness training, each TF element may be provided additional Theatre Mission Specific Training (TMST) prior to deployment dependent on their assigned mission.5

The Canadian Army Doctrine and Training Centre (CADTC), formerly the Land Forces Doctrine and Training Systems in Kingston, ON, is responsible for the CA’s operational doctrine (how the CA will fight) and the individual and collective training (CT) that is at the heart of LR.

Additional information on the composition of each of the divisions and the CADTC organizations is available at Annex E.

The CA’s personnel, training, and materiel, including ammunition, which are the foundation of the LR Program, are managed through the CA’s annual Army Operating Plan, the “Op Plan”. The Op Plan provides detailed direction to divisions regarding their Reg F and Reserves’ training requirements for Normal Readiness (foundation training) and High Readiness (HR), and their allocated training resources including funds, equipment (Managed Readiness Training Fleet for Road to High Readiness (RTHR) training) and specific training objectives. The training standards and training confirmation requirements are clearly detailed in the Training for Land Operations and Collective Training Battle Task Standards documents.

As well, the Op Plan identifies the CA’s HR and standby units to meet the requirements of the CDS’ FP&R directives and CA’s mission remits through its Managed Readiness Plan (MRP). The standby units include the Reg F Immediate Response Units and the Reserve Territorial Battle Groups (TBGs) and Arctic Response Company Groups (ARCGs), which are available for domestic operations. Specific unit task assignments are detailed in a Force Generation task organization matrix, and the Force Generation / Force Employment Transition Plan provides preliminary planning for generating follow-on TFs in the event of a prolonged major operation, such as in Afghanistan.

CA training, as with other CAF training, is comprised of Professional Military Education (PME), Individual Training (IT), and Collective Training (CT). Canadian Army (CA) PME is delivered by a variety of CA and CAF institutions, and IT for CA military occupations is primarily provided at the Combat Training Centre in Gagetown, NB. Much of the specialized army training, such as parachute training and mountain operations, is provided at the Canadian Army Advanced Warfare Centre located at the RCAF’s 8 Wing in Trenton, ON or through allied courses. The divisions provide some IT in a mix of occupation training and individual readiness training, the latter detailed in the CA’s Individual Battle Task Standards6.

Due to the nature of readiness training, this evaluation is focused primarily on CT that is detailed in the Army’s Training for Land Operations7 and Collective Training Battle Task Standards8 publications. CT is described as the means by which an Army commander takes a full complement of qualified solders, with the time, resources and applied tactics, techniques and procedures to produce competent, cohesive and disciplined organizations that are operationally deployable within realistic readiness timelines. CT is conducted predominantly in the divisions’ training and exercise areas as either field training serials or field training exercises for higher level CT (see Table 1 below). The CT conducted by units and headquarters (HQs) for HR is required for those elements to be deployed to international operations. The highest level CT is employed in the HR confirmation exercise, Ex MAPLE RESOLVE, conducted at the Canadian Manoeuvre Training Centre (CMTC) in Wainright, AB.

The CA’s CT levels are described in the table below:

Table 1. CA Levels of Collective Training.10

Table Summary

This table presents the Canadian Army’s different levels of collective training. The top row of the table has two columns, identified left to right as “Level” and “Remarks.” All rows beneath the top row are comprised of three columns, with the column for the level of training further divided into two columns with numbers descending from seven to two, indicating decreasing complexity, with accompanying descriptions of each level in the adjacent column, and additional comments for each level under the “Remarks” column.

| Level | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | Formation (Bde) | May be multinational and includes full spectrum operations in a joint interagency multinational public setting9. |

| 6 | Unit and combined arms unit (battle group (BG) / battalion group) | Level 6 CAX and CPX should be used for command and staff training.Level 6 field training will generally be limited to training for HR, and confirmed by force-on-force training in a joint and combined context. |

| 5 | Combined arms sub-unit (combat team) | Level 5 is the CA’s Reg F level of foundation training. During HR training, it will include live fire training. It is at this level that the synchronization of arms and services becomes critical. |

| 4 | Sub-unit (Squadron / Company / Battery | Similar to Level 3, focused on Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTP) Training. |

| 3 | Sub-sub-unit (troop / platoon | Increased command and control challenges and more complex tactical situations; battle drills should be less detailed. This is the training level to be achieved by Reserves, in a level 4/5 context. |

| 2 | Section / crew / detachment | Generally battle drills, aimed at executing battlefield tasks to a high standard; should culminate in a level 2 live fire event as an exercise serial, or field training exercise. |

1.2.2 Program Objectives

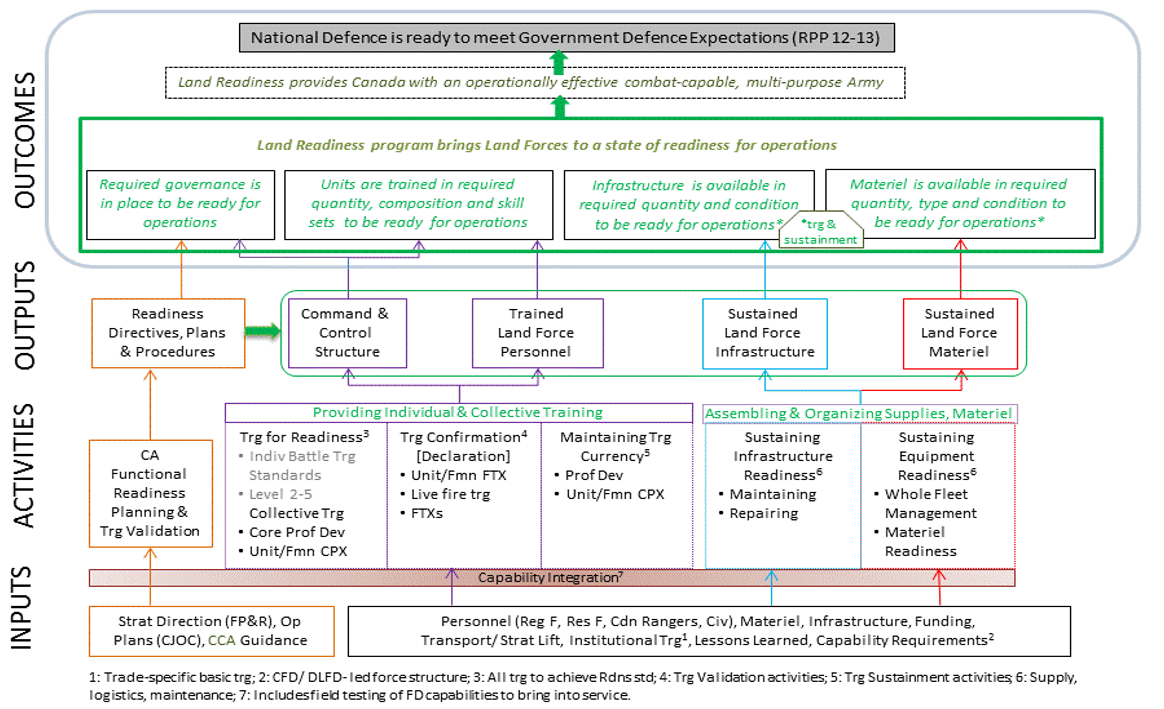

The LR Program objective is to provide the Government of Canada (GC) with a combat-capable, multi-purpose Army. The program will generate and sustain relevant, responsive, combat capable land forces that are effective across the spectrum of conflict, from peacekeeping and nation building to war fighting. The anticipated outcomes of the program are identified in the program logic model at Annex C.

1.2.3 Stakeholders

The principle CAF / DND stakeholder for LR Program is the Canadian Joint Operations Command (CJOC)11. Other CAF / DND elements that may be stakeholders, or partners, depending on the circumstances, include the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), Royal Canadian Navy (RCN), and Canadian Special Operations Forces Command (CANSOFCOM), all of which may operate with the CA in joint training and operations, and receive varying degrees of materiel and personnel support from the CA. Other key partners include the Assistant Deputy Minister (Material) (ADM(Mat)), Chief of Military Personnel (CMP), ADM(Infrastructure and Environment), and the ADM(Information Services). Other government department (OGD) stakeholders include Public Safety Canada and Global Affairs Canada12.

1.3.1 Coverage and Responsibilities

This evaluation covers fiscal year (FY) 2010-11 to 2014-15. The Department’s Program Activity Architecture (PAA) (2009) was substantially revised for FY 2014-15 in a new program alignment architecture with the resultant loss of coherence between program activities and cost capturing under PAA (2009) and the ability to compare FY 2014-15 with previous years’ data. Consequently, this evaluation has focused on activities under PAA (2009) Strategic Outcome 2 National Defence is ready to meet government defence expectations, Program 2.2 Land readiness, and the sub programs:

- 2.2.1 Primary International Commitment

- 2.2.2 Secondary International Commitment

- 2.2.3 Domestic and Standing Government of Canada Tasks

-

2.2.4 Sustain Land Forces

1.3.2 Resources

The table below describes the costs and personnel attributed to the LR Program in the PAA (2009).

Table 2. Land Readiness Expenditures ($ thousands) under the PAA (2009) structure.

Table Summary

This table summarizes the resources used to generate and deliver Land Readiness from FY 2010/11 to FY 2013/14. The left column, in descending rows, lists Land Readiness (PAA 2.2), Total Land Readiness Expenditures, CA Expenditure on Land Readiness, CMP (CA Military Pay), Other Land Readiness Expenditures, Military (Regular Force) Person Years (PYs), and Civilian Full Time Employees (FTEs). The second, third, fourth and fifth columns provide the expenditures in thousands of dollars, and the number of personnel for each fiscal year against each of the left column rows.

| 2.2 Land Readiness | FY 2010/11 | FY 2011/12 | FY 2012/13 | FY 2013/14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Land Readiness Expenditures | $3,350,735 | $3,626,299 | $3,624,786 | $3,308,404 |

| CA Expenditure on Land Readiness | $1,082,597 | $1,206,709 | $1,062,941 | $962,329 |

| CMP (CA Military Pay) | $1,161,689 | $1,224,644 | $1,345,675 | $1,260,118 |

| Other Land Readiness Expenditures13 |

$1,106,449 | $1,194,946 | $1,216,170 | $1,085,957 |

| Military (Reg F) PYs | 17,471 | 15,173 | 16,479 | 17,003 |

| Civilian FTEs | 5,039 | 4,954 | 4,605 | 4,092 |

For the purpose of the evaluation, the focus will be on the CA LR expenditures and CA personnel.

1.3.3 Issues and Questions

In accordance with the Treasury Board Secretariat Directive on the Evaluation Function (2009),14 the evaluation addresses the five core issues related to relevance and performance. An evaluation matrix that lists each of the evaluation questions, with associated indicators and data sources, is provided at Annex D. The methodology used to gather evidence in support of the evaluation questions can be found at Annex B.

2.0 Findings and Recommendations

The following sections evaluate the relevance and performance of the LR Program. The evaluation examined the extent to which the generation and delivery of LR addresses an ongoing need, is aligned with Government of Canada priorities and DND / CAF strategic outcomes and objectives, is appropriate to the role of the federal government, achieves its intended outcomes, and demonstrates efficiency and economy.

2.1 Relevance—Continued Need

Is there a continued need for the Land Readiness Program?

To determine whether land force readiness continues to address a demonstrable need, two key indicators were used:

- Evidence of past engagement of LR (number and type of actual operational employment of the Canadian Army over the past five years); and

- Requirement for LR in future security environment (FSE).

The following findings are based on evidence from document reviews and key informant interviews with CA and Canadian Joint Operations Command (CJOC) staff.

Key Finding 1: There is an ongoing and future need for land readiness for the Canadian Army to be prepared to conduct operations in support of Canada, Canadians, and Canadian national interests.

Indicator: Evidence of past engagement of land readiness (number and type of actual operational employment of Canada’s Army over the past five years)

The LR Program ensures that the CA is ready to support a wide spectrum of operations as evidenced by their readiness to deploy both domestically and internationally. Over the past five years, the CA has been actively engaged in a wide range of defence and security activities, including domestic, continental, and international operations, ranging from major to minor operations15, as summarized in the table below. The decline in deployed personnel reflects the CA’s evolving missions, from a large, highly complex combat mission in Afghanistan in 2010/11 to a large training mission in Afghanistan in 2011/12 and mission close out in Afghanistan in 2012/13. The increase in FY 2013/14 of CA personnel deployed to domestic operations was in support domestic disaster relief operations, such as extensive flood relief and mitigation operations in Alberta, and underscores the unpredictability of the number of CA personnel that may be required in these operations from one year to the next. As this report is prepared, the CA is deployed to central and eastern Europe as part of NATO assurance measures (Op REASSURANCE) and the multinational effort to build the professionalism and capacity of the Ukrainian Armed Forces (Op UNIFIER). Deployment of CA personnel to international operations is at the discretion of the GC based on the strategic situation and government priorities.

Table 3. CA Total Number of Operational Deployments and Cumulative Number of Personnel Deployed FY 2010/11 to 2014/15.

Table Summary

The left column is divided into Number of CA Operations and Personnel Deployed. The second column adjacent to the Number of CA Operations is subdivided into rows for Major and Minor operations, and the column adjacent to Personnel Deployed is subdivided into rows for International Operations, International Support, Domestic Operations and Total. The following columns from left to right for each FY from 2010/11 to 2014/15, present the number of operations and personnel deployed for each year.

| FY 2010/11 | FY 2011/12 | FY 2012/13 | FY 2013/14 | FY 2014/15 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of CA Operations | Major | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Minor | 16 | 17 | 16 | 14 | 13 | |

| Personnel Deployed | Intl | 5562 | 2532 | 903 | 925 | 784 |

| Intl support | 106 | 266 | 41 | 103 | 4 | |

| Domestic | 2636 | 1155 | 376 | 1989 | 512 | |

| TOTAL | 8304 | 3953 | 1320 | 3017 | 1300 |

Indicator: Requirement for land readiness in the future security environment (FSE)

Current DND / CAF assessments of the future security environment16 indicate it will remain characterized by the activities of non-state actors and asymmetric threats while there are increased tensions between NATO and Russia over Russia’s annexation of Crimea, and increasing potential for conflict over disputed international boundaries and resources in the South China Sea. It is also acknowledged that the future environment will constantly challenge CAF capabilities. The LR Program is essential to ensure that CA elements are properly manned, trained and equipped to mitigate unpredictable defence and security risks and be a highly capable Force ready to meet future challenges.

Interviews with CJOC senior staff underscored and confirmed the relevance and future need of the LR Program to ensure that the CA is prepared for international, domestic, and continental operations, highlighting the CA’s annual support to provincial emergency services for floods and forest fires, and the CJOC’s ongoing contingency planning for an array of international operations. The LR Program provides a highly trained and responsive force that is uniquely equipped to support Canada’s defence needs in complex joint and combined operations17, and to assist civil authorities in domestic security and emergencies as necessary when requested.

Accordingly, there will be an ongoing need for the LR Program.

2.2 Relevance—Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

Does the Land Readiness Program align with federal roles and responsibilities and those of DND / CAF?

This section examines the extent to which the generation and delivery of LR by the CA aligns with departmental and federal roles and responsibilities. The findings in this section are based on documents reviewed and key informant interviews, including senior CA and CJOC staff.

The following indicators were used in the assessment of alignment with federal roles and responsibilities:

- Alignment with government acts, legislation and strategic direction; and

- The extent to which Canada’s land forces, the Canadian Army, conduct activities that are the responsibilities of other government departments, other levels of government or the private sector.

Key Finding 2: There is alignment between the generation and delivery of the Land Readiness Program with departmental and federal roles and responsibilities.

Indicator: Alignment with government acts, legislation and strategic direction

Defence is a core federal government responsibility as articulated in the Constitution Act,18 which defines and outlines the responsibilities and duties of the federal government, including the Canadian Armed Forces and the Department of National Defence. Furthermore, the National Defence Act, Article 17 establishes the DND and CAF as separate entities, operating within an integrated National Defence Headquarters (NDHQ), as they pursue their primary responsibility of providing defence for Canada and Canadians. The National Defence Act and various federal government Orders in Council also provide for CAF assistance to federal and provincial civil authorities.

The government also provides strategic direction to the CAF with respect to the types of missions it is prepared to undertake and in which land forces played a central role. Those missions include being prepared to support civilian authorities during a crisis in Canada, such as natural disasters, as well as the ability to lead or conduct a major international operation for an extended period of time, and deploy forces to crises elsewhere in the world for shorter periods.

Indicator: The extent to which Canada’s land forces, the Canadian Army, conduct activities that are the responsibilities of other government departments, other levels of government or the private sector

Land Force operations have occurred in direct support of other federal and provincial government departments and agencies and their provincial and community counterparts, within a whole-of-government framework, and as provided for in the Federal Emergency Response Plan. In each case, the CA has played a complimentary role, augmenting civil agencies when they have become overwhelmed or required a unique CA capability in support of the domestic crisis or security operations for which they were the lead department. When conditions are established to permit civil authorities to assume full responsibility for managing a crisis, such as a flood or wildfire, or a special support task has been completed, the CA involvement is terminated.

2.3 Relevance—Alignment with Government Priorities

Does the Land Readiness Program align with federal government priorities and defence strategic outcomes?

This section examines the extent to which the generation and delivery of LR is consistent with federal government priorities and DND strategic objectives. The findings in this section are based on evidence from documents reviewed for the evaluation, which include Federal Budget Plans (2010-2014), Speeches from the Throne, policy, and Reports on Plans and Priorities.

The following indicators were used to make this determination:

- Alignment with or inclusion of land readiness in stated government priorities; and

- Alignment with or inclusion of land readiness in DND / CAF priorities or strategic outcomes.

Key Finding 3: The generation and delivery of land readiness is consistent with federal government and the DND / CAF roles of defending Canada, defending North America and contributing to international peace and security.

Indicator: Alignment with or inclusion of land readiness in stated government priorities

The 2013 Speech from the Throne pledged the government to renew defence policy. It stipulated, “now and in the future, Canada’s Armed Forces will defend Canada and protect our borders; maintain sovereignty over our Northern lands and waters; fight alongside our allies to defend our interests; and respond to emergencies within Canada and around the world”.19 The Government’s continued financial support to the LR Program, and employent of the CA as one of its instruments of foreign policy, is further evidence of the LR Program’s alignment with the Government’s priorities.

Indicator: Alignment with or inclusion of land readiness in DND / CAF priorities or strategic outcomes

Document review clearly indicates that the delivery of combat-ready land forces by the LR Program is directly aligned with the DND / CAF priority of “ensuring operational excellence both at home and abroad” and in accordance with CDS Force Readiness and Posture direction. The LR Program activities, which generate deployable, combat-ready land forces, provides direct support to CAF combat-ready forces in support of the CAF’s enduring missions.20 The program continues to generate and sustain relevant, responsive, combat capable land forces that are effective across the spectrum of conflict, from peacekeeping and nation-building to war fighting.21

The CA also aligned to the DND / CAF priority of “reconstituting and aligning the CAF post-Afghanistan.” Alignment over the evaluation period includes disengaging from the Afghanistan combat mission, implementing the training mission, and reconstituting personnel and equipment, as addressed in the CA’s plan. Further, this reorientation and reorganization supported land forces’ alignment to fulfill the CAF’s six enduring missions.

Finally, the Report on Plans and Priorities for the Department (FYs 2010/11 to 2013/14) placed specific emphasis on providing Canada with combat-capable, multi-purpose land forces. These reports consistently included the priority to “generate and sustain relevant, responsive, combat capable land forces that are effective across the spectrum of conflict, from peacekeeping and nation-building to war fighting. The CA embodies this by “bringing land forces to a state of readiness for operations, assembling and organizing land personnel, supplies, and materiel as well as the provision of individual and collective training to prepare land forces to defend Canadian interests domestically, continentally and internationally”.22

Therefore, the LR Program is deemed to be a high priority for the DND / CAF.

2.4 Performance—Achievement of Expected Outcomes (Effectiveness)

This section presents the assessment of the effectiveness of the LR Program. To make this assessment, the evaluation examined the ability of the program to achieve the following outcomes:

- Immediate outcome: The Land Readiness Program brings land forces to a state of readiness for operations; and

-

Intermediate outcome: The Land Readiness Program provides Canada with an operationally effective combat-capable multi-purpose Army.

2.4.1 Immediate Outcome

The LR Program brings land forces to a state of readiness for operations.

Broadly speaking, readiness refers to the operational capability and responsiveness of land forces to conduct the operations or tasks that they are assigned. Operational capability is a function of three factors23:

- Personnel—numbers, qualification levels and deploy ability from a physical and mental health perspective;

- Training—individual and collective; and

- Equipment—availability and serviceability.

Responsiveness is defined by the ability of a unit or Task Force to meet a prescribed Notice to Move: a warning order that specifies the time given to a unit to be ready to deploy.24

The following indicators were used to assess achievement of the immediate outcome:

- Land Unit / Brigade (Bde) manning and training are confirmed against stated CCA’s requirements (High Readiness (HR) and Normal Readiness (NR))25;

- Land operational equipment and materiel availability meet CCA’s requirements;

- Land infrastructure meets CCA’s training and operational requirements;

- Land Force governance structure and function support CCA’s requirements; and

- CCA’s readiness requirements comply with CDS force posture and readiness direction.

Indicator: Land Unit / Bde manning and training are confirmed against stated CCA’s requirements (HR and NR)

Key Finding 4: The LR Program has met all actual operational requirements to-date; however certain concurrent operational requirements could ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓in the support trades and enablers, such as the intelligence and signals trades.

Document review and key informant interviews indicate that Reg F units consistently achieve the foundation NR and HR training that they are required to complete, however HR units are challenged by the portion of their personnel who are deployable. For example, the portion of CA Reg F personnel deployable was ▓▓▓▓percent in September 2012 and was ▓▓▓▓percent in September 2015.26 Consequently, HR units may be reliant on augmentation from other units from within or, occasionally, outside their Division, depending on an assigned mission’s requirements. In fact, the portion of personnel that is deployable means that the three infantry battalions in a CMBG are required in order to generate two that are fully manned. The CA MRP requires only two of the three infantry battalions within the HR CMBG be assigned to HR tasks; one on standby for deployment with the HR battle group (BG) to a major international operation and the other on standby for a minor international surge operation. The MRP leaves the third battalion to augment the two HR battalions, as required, and provide elements to the 1st Cdn Division HQ in support of a non-combatant evacuation operation and the Disaster Assistance Response Team.

Notwithstanding the augmentation available from the CMBG’s third battalion, the CA is seeking to increase its number of deployable personnel by implementing an integrated program of resources and services to strength the personal readiness and resilience of its soldiers and to assist Army families and DND Army civilians in preparing for the demands of Army life.27

As already alluded to, the CA has an extensive list of tasks related to the CAF FP&R direction and CA elements are assigned against these tasks in the CA’s MRP and Force Generation Task Organization Matrix that are promulgated annually in the CA Op Plan. 28 The MRP and Task Organization Matrix cover a five year period in the Op Plan, and are updated annually or as may be required by operational requirements. In each case, the adequacy of the assigned elements for an operational TF will be determined by the actual size and complexity of the mission assigned. Depending on circumstances, an infantry battalion, company or a brigade HQ assigned to a mission may require augmentation from other elements within the brigade or from another division. As well, some specialty / support elements in the Task Organization Matrix are assigned more than one task that may create concurrency issues if they are required for simultaneous tasks. An example cited by the 4th Cdn Div HQ staff was that one of the Royal Canadian Regiment’s battalions in Petawawa was part of the HR Div for Domestic Ops, the Immediate Response Unit (IRU) for the Division, and also tasked to support the 1st Cdn Div in the event it was required to deploy. They also stated that there is ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓29

A study was conducted to assess personnel operational requirements reflecting a similar level of commitment (and casualties) as when the CA was deployed to its combat mission in Afghanistan, with simultaneous missions for the lead mounting divisions supporting a CA line of operation (LoO) 3 (major international mission) and CA LoO 4 (response to crisis elsewhere in the world for shorter periods).30 Modelling for several different operational cycles (e.g., 24 and 36 month cycles) revealed the lead mounting divisions required ever increasing augmentation to force generate multiple rotations, as depicted at Figure 1 below.

The level of personnel shortages and augmentation varied for each mission rotation of the CA divisions (at the time of the study referred to as Land Force Western Area (LFWA), Land Force Central Area (LFCA), and Land Force Quebec Area (LFQA) for the 3rd, 4th and 2nd Canadian divisions, respectively). As seen in Figure 1, there is a diminishing number of personnel available from the primary HR brigade (bright green in the figure) over repeated operational rotations, with increasing levels of other CAF and Reserve personnel from both within and from outside the division, and varying levels of personnel shortages (red) that could not be filled from any source. Identifying the required augmentees was a continual challenge during the CA’s combat mission in Afghanistan and there were consistently personnel shortages, as indicated in red in the modelling at Figure 1.

The total number of deployable personnel required is only a part of the challenge the CA faces as it has also had to deal with shortages in certain critical officer classifications and non-commissioned member occupations (part of the personnel shortages in the red in Figure 1). These have been most pronounced in specialty and support trades (combat engineers, crewman, and vehicle technicians), which has necessitated a further CA wide approach to sourcing required personnel.

Figure 1. Combined Sustained Major Operation and Minor Surge Operation with 16 months between personnel deployments (24 month cycle) and pan-Army augmentation31.

Figure Description:

A bar graph that depicts operational rotations (ROTOs) for a mission along the X-axis and the number of personnel required for each ROTO on the Y-axis. It is comprised of personnel from the Primary Force generating area (now referred to as Canadian Division), the number of augmentees provided by Reserves, other Regular Force Units in the area, Regular Force units from outside the area, and the number of unfilled personnel requirements.

| R0 - LFWA | R1 - LFCA | R2 – SQFT | R3 – LFWA | R4 – LFCA | R5 – SQFT | R6 – LFWA | R7 – LFCA | R8 - SQFT | R9 - LFWA | R10 - LFCA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | 2030 | 1410 | 1470 | 2121 | 1364 | 1500 | 2152 | 1455 | 1561 | 2136 | 1479 |

| CF/ PRes | 320 | 940 | 940 | 940 | 940 | 940 | 940 | 940 | 940 | 940 | 940 |

| Area Augment | 1075 | 1120 | 1068 | 749 | 1195 | 1021 | 647 | 989 | 919 | 692 | 1074 |

| Out of Area Augment | 442 | 713 | 533 | 404 | 687 | 629 | 472 | 798 | 686 | 441 | 670 |

| Unfilled | 8 | 57 | 229 | 26 | 54 | 150 | 29 | 29 | 134 | 31 | 77 |

| Total | 3875 | 4240 | 4240 | 4240 | 4240 | 4240 | 4240 | 4240 | 4240 | 4240 | 4240 |

Key Finding 5: The LR Program is ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ based on personnel numbers and availability in the absence of an operational mission.

Figure 1 also reveals the critical augmentation role of the Reserves in CA operations, reflecting the Army’s moto, “One Army”. However, the CA Reserves have also been assigned specific operational tasks beyond individual augmentation for CA Reg F units. The CA Res F is responsible for generating ten TBGs of ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ personnel each, one per CBG and four ARCGs of ▓▓▓ personnel each, one per division as tasked in the CA Op Plan. The role of these two force employment models is to augment or replace the CA Reg F IRU within each division. Each division’s CBGs are additionally responsible for generating up to more than 800 personnel for other Reserve specific HR elements that may be required for international operations.

In all cases, the current FG tasks assigned to the Reserves do not take into account the Reserves available in the CBGs assigned to the divisions. The number of personnel, their availability, rank and military occupation all vary significantly between each of the CBGs. The CA has also estimated that five Reservists are required to generate just one (5:1 ratio) for international operations and that three Reservists are required to generate one (3:1 ratio) for domestic operations, which may be ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓of the Reserves.32 As well, in 2015, only ▓▓percent of Reservists were normally deployable, albeit this was still significantly higher than the ▓▓▓▓percent that were available when Reservists were deploying to Afghanistan in September 2012. 33

Reserve readiness information, which is tracked at the division level, was not reviewed by this evaluation. However key informant interviews indicated that the Reserves have inconsistent confirmation methods, which are not captured systematically. Interviews also indicated that CBGs have successfully mobilized company sized elements of a TBG and each year the TBG HQ and other key staffs complete a readiness confirmation CPX / CAX conducted by their respective division. All that said, the viability of the ARCG and HR Reserve elements, such as the Convoy Escort, Influence Activity Company, or Force Protection Company remain to be confirmed.

When the CA is not force generating for a named mission there is currently no direction similar to the CA Op Plan regarding managed readiness to force generate HR Reserve elements. The current plan is the Reserves will not participate in Roto 0 of an international mission (except for some small influence activity and intelligence capability elements) as participation in the RTHR becomes potentially wasteful of training resources if there is no mission for the Reserves to be assigned to. Ideally, CBG elements will be tasked to achieve a higher state of readiness at a moment in time when they may be integrated into the Reg F RTHR training for Roto 1 of a mission.34

In the meanwhile, it remains uncertain whether, in any circumstance, a division could successfully field the required HR Reserve elements solely from its own CBGs. That said, after the first rotation of a prolonged mission, and with a pan-Army effort, the CA would likely be able to assemble most of the individual Reserve augmentees required and the Reserve-specific HR elements for follow on mission rotations, and ensure their full integration with the Reg F RTHR training prior to deployment.

The CA also trains to be ready for operations in the arctic through annual division level exercises, including IRU and ARCG exercises, and the conduct of joint sovereignty operations such as Op NANOOK35. Reg F and Reserve Arctic training has also been enhanced by increased integration of the Canadian Rangers in their training to improve soldiers’ non-combat skills in the harsh northern environment.36 Additional improvements are required however, through training and the acquisition of improved transport and communication capabilities37, for the CA to achieve a sustainable response capability for the Arctic38.

Finally, regarding the Canadian Rangers, they are not trained to Reg F or Reserve standards, but receive their own “foundational” training. Through their training, and their local / environmental knowledge, they provide valuable support to both Reg F and Reserve training and operations, and are available to support crisis operations, such as Search and Rescue within their local areas.

ADM(RS) Recommendation

1. The CA continue current efforts to increase the deployability level of available personnel through the Canadian Army Integrated Performance Strategy (CAIPS) and other similar initiatives to enhance the personal readiness and resilience of individual soldiers.

OPI: CCA

OCIs: CMP

ADM(RS) Recommendation

2. The CA work with CMP to address ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ Reg F and Reserve trades and enhanced Reserve recruiting while building on the success of well manned and supported Reserve units and maintaining less sustainable units until such time as those units can demonstrate growth potential.

OPI: CCA

OCI: CMP, C Res

Indicator: Land operational equipment and materiel39 availability against CCA’s requirements

Key Finding 6: ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓

Interviews and CA documents have underscored a ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ ▓ In the case of training, units ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ for unit level CT. More importantly, as detailed below, units ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓or commercial lease in the case of B fleet (logistical support / utility) vehicles in domestic operation.

The ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓in both the A fleet (fighting) and B fleet vehicles have been exacerbated by:

- ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓

- High vehicle off road (VOR) rates for existing fleets attributable to:

- Responsiveness of the National Procurement Program to ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ of the vehicle fleets (and other equipment)40,

- A possible lack of responsiveness in the spare part supply system,

- Cancellation of a national maintenance contract to provide B fleet maintenance,

- A continuing shortage of ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓41,

- Low vehicle tech productivity42, and

- ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ for new equipment.

- Increased usage rates / maintenance requirements of available vehicles; and

- Delays and cancellations in major equipment programs ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ on original program delivery schedules. ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ Significant major equipment transition gaps and risks are highlighted in Figure 2 below.

The new Leopard 2 fleet of vehicles (Leo 2 FoV), confronted with several of the above challenges, epitomizes CA’s current equipment difficulties. 43

Figure 2. Canadian Army Major Equipment Transition.44

Figure Description:

A graphic figure, depicting time in calendar years from 1980 to 2030 along the X-axis, with a vertical line, labeled “Now” around the year 2015 on the X-axis. Various major Army equipment are depicted above the X-axis and moving left to right along the X-axis for each equipment this figure depicts how it is disposed of, modernized or replaced by new equipment. There is a line for each equipment transition from green, indicating it is meeting requirements; to yellow, meaning it is insufficient to meet requirements, to red, meaning there is a critical shortage pending delivery of modernized or new equipment. The line then transitions back to green as the new equipment becomes available.

1. Leo 1

a. In 1980 the CF had 140 serviceable (green) Leopard 1 Main Battle Tanks

b. In the early 2000’s, the serviceability declined to yellow

c. In 2010, a total of 82 new Leopard 2 tanks were purchased in three variants:

i. 20 x A6M tanks,

ii. 20 x A4M tanks, and

iii. 42 x A4 tanks.

d. In 2015, the Leopard 2 tank fleet availability transitioned to yellow, with green status forecast for 2018

e. In 2015, Leopard 1 engineering versions turned red and they are being replaced by:

i. 18 x Armoured Engineering Vehicles (AEVs) with ploughs, rollers, and dozer blades, and

ii. 4 x Armoured Recovery Vehicles (ARVs)

f. Around 2018, Leopard 2 AEVs and ARVs will become green.

2. M113

a. In 1980, the CF had1300 serviceable M113 Armoured Personnel Carriers

b. Around 1995, the M113 fleet went yellow and was replaced by:

i. in the late 1990’s 651 x Light Armoured Vehicles (LAV)-3, and

ii. in the early 2000’s 274 x M113s were modified to a Tracked Light Armoured Vehicle (TLAV) configuration

c. Around 2010, LAV-3 and TLAV serviceability turned yellow

d. Around 2015, 550 LAV-3s were updated to LAV 6.0

e. Around 2015, TLAV fleet turned red, it was reduced to 135 critical variants, and is scheduled to be replaced by an Armoured Combat Support Vehicle (CSV) (TBD) around 2020.

3. LAV-2 Bison

a. Around 1990, the CAF had 199 serviceable Light Armoured, type 2, Bison vehicles

b. From 2001-2010, vehicles were converted and upgraded to extend vehicle life to 2020.

c. In 2015, it reached a red serviceability status

d. Around 2020, LAV-2s are scheduled to be replace by 307 Tactical Armoured Patrol Vehicles (TAPV) (Utility) vehicles

4. LAV-2 Coyote Reconnaissance

a. In early 1990’s, CAF had 202 serviceable Light Armoured, type 2, Coyote Reconnaissance vehicles

b. In mid-2000’s, the fleet went yellow and around 2010 it became red.

c. In 2015, LAV-2 Coyotes were replaced by:

i. 66 x LAV Reconnaissance Surveillance System Upgrades (LRSS UP) (LAV 6.0). These vehicles will help offset reduced numbers from the M113/LAV-3 replacement, and

ii. 193 x TAPV (Recce) vehicles

5. MLVW

a. In 1980, the CF had 2792 serviceable Medium Logistics Vehicles - Wheeled

b. In late 1990’s, the fleet went yellow

c. Around 2010, the fleet was reduced to retain 105 essential shelters while the remainder was replaced by 1300 x Militarized Commercial Off the Shelf (MILCOTS) vehicles

d. In 2015, the retained vehicles turned- red and they are scheduled to be replaced around 2020 by 1500 x Medium Support Vehicle System – Standard Military Pattern (MSVS SMP)

6. HLVW

a. Around 1990, the CF had 1212 serviceable Heavy Logistics Vehicles – Wheeled

b. In early 2000’s, fleet went yellow and was reduced to 591

c. In 2015, the fleet turned red and it is scheduled for replacement in early 2020’s

d. Vehicle numbers to be ‘Offset ? by MSVS SMP procurement

7. LSVW

a. In early 1990’s, the CF had 2877 serviceable Light Service Vehicles – Wheeled

b. In the early 2000’s, the fleet went yellow and was reduced to 1333

c. In 2015, the fleet went red and it is scheduled to be replaced in the early 2020’s by the Logistics Vehicle Modernization (LVM) Project (TBC)

8. LOSV and ATV

a. In late 2000’s, the CF procured 310 Light Over Snow Vehicles and 310 All-Terrain Vehicles for the Arctic

b. In 2015, these fleets turned yellow due to the heavy use in extreme conditions

9. BV-206

a. In the early 1980’s, the CF had 108 serviceable Medium Over Snow Vehicles (BV-206)

b. In the 1990’s, the fleet went yellow

c. In the early 2000’s, the fleet went red

d. In the late 2000’s, 14 vehicles were rebuilt and retained for essential Ops

e. In the early 2020’s, the fleet is scheduled for replacement by the Domestic and Arctic Mobility Enhancement (DAME) Project (TBC)

10. (PSS) – (P Res)

a. In early 2010’s, a Persistent Surveillance System (PSS) (an aerostat with a stabilized electro-optical surveillance system) was purchased for Army Primary Reserve (P Res)

b. In 2015, the PSS required one year to prepare for operations.

The Canadian Army Equipment Readiness Strategy45, promulgated 27 May 2013, noted that equipment availability was the ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓, with most standard military pattern vehicles achieving CA-wide operability levels of ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ as of January 2013. It also noted that each Lead Mounting Division had ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ to force generate routine domestic and international operational commitments without reinforcement from other divisions, and this was projected to remain ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ for the duration of the LAV upgrade (LAV 6) program and introduction of the tactical armoured patrol vehicle (TAPV). The ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓, as of 9 June 2015, was ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ LAVs among the three principal divisions. 46

The CA’s overall armoured vehicle fleet also declined from ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ in 2014 to ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ in 2015 as leopard tank / engineering variants, and particularly tracked LAV (TLAV) (M113 variants), were reduced and a smaller number of new light armoured vehicle (LAV) 6 vehicles entered service than the number of LAV IIIs removed from service.47

The CA has sought to ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ through:

- Whole fleet management, assigning vehicles and equipment to divisions based on their organizations and operational requirements, prioritizing support to divisions for their RTHR training and HR standby periods;

- Establishment of a Managed Readiness Training Fleet assigned to divisions on the RTHR;

- A quarantine fleet of vehicles and equipment maintained and preserved for a major international operation, ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓48;

- The Canadian Army Equipment Readiness Strategy that seeks to reduce vehicle VOR rates through a variety of initiatives49; and

- Extensive leasing of commercial utility vehicles.

While there is a persistent ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ for the Reg F Divisions, the ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ for their respective CBGs and Reserve units. Many of the Reserve’s B fleet vehicles were taken by the Reg F to meet their requirements resulting in an increased dependence by the Reserves on commercial vehicles to meet their training requirements.50

In addition to the Reserves’ ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ of B fleet vehicles, the maintenance of their military vehicles is ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ and accessibility to the limited Reg F maintenance services.

While CA ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ have been the focus of the above analysis, the CA also has a ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ of other smaller but also critical equipment. Those deficiencies are epitomized by the ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ impacts both training and operations as the CA awaits delivery of its new communications equipment, and has led to Reserve units having to use commercially available radios and walkie-talkies in their field training exercises.51

Key Finding 7: The CA’s readiness for Arctic Operations ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ required for those operations.

Finally, both Reg F and Reserve capabilities in the Arctic are ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ to support CA training and operations in the region. The most important vehicle available to support Army activity in the north is the BV-206 tracked carrier that is used primarily by the CA IRUs and ARCGs for domestic operations and training in the North. The BV-206 ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓; having entered service in ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ The Army has been slowly divesting these vehicles over the past 20 years and the numbers have now been reduced to ▓▓▓▓▓ as per Figure 2 above. The lack of a replacement vehicle for the foreseeable future will be a significant constraint on the Army’s responsiveness and capabilities in the Arctic.

ADM(RS) Recommendation

3. The CA continue to implement and refine the CA Equipment Readiness Strategy to achieve CA VOR targets.

OPI: CCA

OCI: ADM(Mat) / DGLEPM

Indicator: Land infrastructure meets CCA’s training and operational requirements

The CA is supported by extensive, and largely aged infrastructure, which has not been adequately maintained for many years as reported by the Office of the Auditor General52, and much of which is not optimized for today’s CA training and operational requirements. Notwithstanding these impediments, to-date, the CA has been able to meet its training and operational requirements.

As reported in the 2011 Evaluation of Land Force Readiness and Training, and to some extent still, “as a result of geography, environmental, and property issues, virtually all heavy calibre weapons firing and collective training above Level 3 or 4 (particularly live fire) must take place at either Wainright or Gagetown”. During the CA’s Afghanistan operations, training also had to be undertaken at the U.S. Army’s National Training Centre at Fort Irwin in California during winter months to more closely simulate environmental operating conditions in Afghanistan.53 As well, there is increasing encroachment on existing ranges and training areas, by both urban settlement and commercial activity including petroleum exploitation in key training areas. There are no practical solutions to overcome these constraints beyond most units having to move significant numbers of personnel and equipment to the required exercises areas that are distant from their bases, at significantly greater cost. Nonetheless, based on training documentation, readiness reports, and key informant interviews, CA training requirements are being met for Reg F elements and are largely met for Reserve units.

Key Finding 8: Current CA infrastructure ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓

Interviews and documentary evidence have highlighted that the CA’s current infrastructure is ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ some of the newer vehicle fleets being acquired. The principle reason for this was ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ requirement when the CA was focused on the urgent acquisition of new equipment for operations. This is particularly a result of the increased size, weight and numbers for the ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ being assigned to units in Edmonton and Gagetown and the larger LAV 6 that will be distributed to all divisions.54

As well, the CA has noted that the repair and maintenance of its facilities has been consistently ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓, and the infrastructure ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓, with Reserve armouries (accommodations) among the worst cases.55 While most infrastructure remains serviceable, the CA is divesting itself of surplus or non-viable infrastructure to save on the personnel and financial resources required to maintain them.

Finally, CA infrastructure in the North is ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ and the only significant facility is the CAF Arctic Training Centre in Resolute, which is shared with Natural Resources Canada. While intended for training, it could provide limited support for accommodations, supplies, and equipment for northern operations.

ADM(RS) Recommendation

4. The CA work with ADM(Mat) and ADM(IE) to document current infrastructure deficiencies and develop a plan to address inadequate facilities that are being used to warehouse and repair new equipment and to enhance equipment availability for training and operations.

OPI: CCA

OCI: ADM(Mat) / DGLEPM and ADM(IE)

Indicator: Land Force governance structure and function against CCA’s requirements

The CA is comprised of a highly developed governance structure that entails training and professional development, capability development and force management, which support Army command decisions and informs CA engagements with CAF command and department resource authorities. The various governance bodies inform in-year CA resource allocation, the CA’s force development, and priority of work to meet both its near-term and long-term requirements. During the course of the CA’s Afghanistan operations, it successfully fielded new doctrine, Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures and equipment to meet the CA’s immediate operational needs, while still planning for the post-Afghanistan CA as reflected in its strategic concept documents56.

Notwithstanding these success stories, the CA Army Training Authority and the Chief of Staff Land Strategy (now Chief of Staff Army Strategy) recognized in 2010 that the CA needed to update its existing governance structure.57 As the governance structure was reviewed, it was concluded in early 201458 that:

- As a result of changes in leadership at the strategic and operational levels, the manner in which the CAF/DND is governed had changed. Various decision-making boards / committees had changed, been created, or eliminated and it was noted:

- The Defence Renewal Team was examining the governance of DND / CAF, and

- Both the RCAF and RCN had changed their governance models to better align with that of the higher NDHQ DND / CAF governance model; and

- The CA had a strategy (Advancing with Purpose) and was producing an annual Op Plan that governed its allocation of resources and key readiness activities. However, it did not have a campaign plan to operationalize the strategy, nor to link it to the Op Plan, and had not identified the timeframe or the ends, ways and means to achieve the strategy.

In July 2014, the CCA issued direction to review the Army’s Strategic Decision Making Handbook, originally published in July 2004, to reinvigorate the effectiveness and discipline in the Army’s decision making process.59 Part of this will be to align processes with the new CAF and CA structures, and synchronize activities of the CA’s various boards and working groups with the analogous CAF and DND entities. As well, the CA is developing a campaign plan to better synchronize and advance the Army strategy across all lines of governance. These initiatives remain a work in progress.

Indicator: CCA’s readiness requirements comply with CDS Force Posture and Readiness direction

Review of CDS strategic guidance and directives on CAF FP&R indicate that the CCA’s readiness requirements are closely aligned with those documents.60 The CA’s annual Op Plan and MRP identify the CA elements assigned to CAF missions and provide detailed training and readiness direction along with prioritized allocation of financial and other resources required for units to achieve their prescribed readiness requirements. In his CDS Guidance to the CAF, the CDS continues to give priority to large-scale CAF exercises and training opportunities. The CA meets this intent through its HR confirmation exercise, Ex MAPLE RESOLVE, the most complex operational level exercise conducted in Canada with ever increasing joint and combined elements. Additionally, the CA is a key player in the major joint exercises JOINTEX and Op NANOOK.

Annex F of the report provides a comparative analysis of challenges faced by the CA with those faced by the US, British and Australian armies. Based on that comparison, the CA budget cuts fall between the cuts made to the US and British armies and the growth that the Australian Defence Force and Australian Army are enjoying. Also noteworthy is that defence cuts for the CA have not extended to a reduction in personnel, units and base closures as with the U.S. and British armies.

Key Finding 9: A ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ in the three pillars of readiness (personnel, training and equipment) in the CA may ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓

To date, the CA has done an admirable job of maintaining readiness with its available personnel, equipment, and infrastructure; however CAF ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ in the CA’s equipment and training programs, even as the CA’s personnel strength and operational tasks have so far remained untouched. In the context of the three pillars of readiness (personnel, training, and equipment) there is a ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ between the pillars, with training and materiel ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ It has been suggested by several authorities, including U.S. Senator McCain and former CAF CDS, Gen Natynczyk, that ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓61 While this balance could be re-established, in part, by ▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓

2.4.2 Intermediate Outcome

The Land Readiness Program provides Canada with an operationally effective combat-capable, multipurpose army.62

The following indicators were used to assess achievement of the intermediate outcome:

- The CA has demonstrated it is an operationally effective combat-capable, multi-purpose Army;

- The CA has demonstrated the ability to lead or conduct a major international mission for an extended period with WoG and allies; and

- The CA has demonstrated the ability to respond to a secondary crisis elsewhere in the world for a shorter period of time with WoG and allies.

Indicator: The CA has demonstrated it is an operationally effective combat-capable, multi-purpose Army

Key Finding 10: The Army has demonstrated its effectiveness across the full spectrum of operations from disaster relief and humanitarian operations to combat.

The Canadian Army has made its primary mission to be an operationally effective combat capable multipurpose army, and is dedicated to being ready to execute a wide range of land-centric missions at home, in North America, and internationally within a joint, interagency, multinational and public environment. This capability has been confirmed on exercises and demonstrated on both domestic and international operations.

Expeditionary Operations: The CA has been successful on overseas missions, which can be attributed to an effective readiness program. The RTHR model culminates in a final exercise, followed by the achievement of HR training requirements which is confirmed by the Commander Canadian Army Doctrine and Training Centre on behalf of the CCA. Following this confirmation, a declaration of operational readiness is submitted by the CCA to CJOC63. As a mission progresses and an operational environment evolves, as it did in Afghanistan, a robust lessons learned process informed requirements of the next RTHR training cycle and Theatre Mission Specific Training, which were then confirmed during the final HR exercise, MAPLE RESOLVE64.

Interviewees in Dr Windsor’s 2013 study of Op ATHENA65 unanimously agreed that the Road to High Readiness training model worked in preparing their platoons, companies and battalions for the Kandahar campaign. With but few exceptions, they felt collective training exercises at the CMTC in Wainwright, Alberta, and at locations in the southwestern United States provided opportunities for sub-units to develop cohesion and hone small-task confidence and flexibility. Senior veterans who recalled pre-deployment training for missions in the 1990s were especially positive about the system, including the opportunity to work through the unique rules of engagement that evolved through the campaign. Among other things, the centralized CMTC collective training system served as a vehicle for disseminating the latest lessons learned coming out of the theatre. It was arguably always a tool for transmitting the most recent experience but, by 2009, the process became more systematic. In particular, by 2009, CMTC collective training included the latest air-land tactics, the importance of gathering “white situational awareness” or information about the local population, and the latest methods of conducting influence and information operations. The one exception to this highly adaptive training was the training for the Task Force closing out the combat mission, prior to commencement of CA training for the Afghanistan Army training mission centred on Kabul, Op ATTENTION. That TF was prepared for the former combat mission, but not optimally prepared or structured to be most effective in the close out of Op ATHENA.66

Domestic Operations: The CA has been highly responsive and effective when deployed to the nine domestic operations that occurred during the evaluation reporting period,67 consistently meeting the requesting agency’s expectations68. Reg F Immediate Response Units have responded to short notice requests for assistance, and have been reinforced by Reserve TBG elements in accordance with their notices to move. In 2013, Op LENTUS 13-01, the CAF flood relief operation in Alberta, had a significant CA component that clearly demonstrated effective integration of Reg F units, a Reserve TBG, and specialist elements. Assigned units had commenced disaster relief operations within 24 hours of reconnaissance elements being deployed.69 That said, as with expeditionary operations, interoperability and operational effectiveness would be further enhanced by greater routine engagement of provincial and local levels of government, particularly in regions that are commonly victims of floods or forest fires.