Section 2: The Military Profession in Canada

Civil-Military Relations

The Constitution Act of 1867 assigned Canada’s defence to the federal government. Thereafter, Militia and National Defence acts have specified how this would be executed in terms of organization, size, command and civil control.

A small regular force was created between 1871 and 1887 with the establishment of three artillery batteries, the Royal Military College of Canada, a troop of cavalry, three companies of infantry and a school of mounted infantry. In the early days, this force was primarily viewed as a training cadre for the militia. Nonetheless, the nucleus of the full-time profession of arms in Canada had been created. In due course, these forces expanded with the addition of the Royal Canadian Navy in 1910 and the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1924. In 1968 the government unified the three services and established the Canadian Forces

The profession of arms in Canada has always operated within the institutional context established by the government through its constitutional instruments. This structure makes the representative of the Crown—the Governor General—the Commander-in-Chief, in formal terms, though not in practice.

The profession operates within the context of a government department headed by a Minister of the Crown responsible to Parliament and the Canadian people, through the Prime Minister and his/her Cabinet, for all the activities of his/her department, as stipulated by the doctrine of responsible government. Below the Minister is the Deputy Minister (DM) and the senior military officer (since 1966, the Chief of the Defence Staff). The Governor in Council appoints both the Deputy Minister and the Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS), and the CDS has direct access to the Prime Minister should circumstances warrant such action. The Minister of National Defence approves the promotions of all other General/Flag officers, with the exception of the Judge Advocate General, on the recommendation of the Chief of the Defence Staff.

Essentially, the roles and responsibilities of the Deputy Minister and the CDS are divided along the lines of administering the department and directing the Canadian Forces, respectively.

In the Department of National Defence, a line of authority and accountability extends from the DM to every member of the department and the Forces who exercises modern comptrollership or financial management, manages civilian human resources or contracts, or has other authorities delegated by the DM.

To direct the Canadian Forces, the CDS heads up a military chain of command that is responsible for the conduct of military operations through the appropriate military echelons. The CDS is the sole military advisor to the government and has equally important responsibilities for the stewardship of the profession of arms embedded in the Canadian Forces. It is these responsibilities that form the main subject of this manual.Footnote 9 In particular, the relationship between the dual aspects of institutional command and control and professional responsibility, particularly as they affect the CDS’s principal professional advisors, will be explained under the heading “Professional Responsibilities”.

The Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces are two distinct entities and constitute two important components of the overall national security structure of the country. This structure includes all the other diplomatic, economic and information elements essential to developing security policy. At the apex are the Prime Minister and the Cabinet. Within this framework, the development and articulation of Canada’s defence policy is among the most important responsibilities of the Minister of National Defence.

Such policy is set within the larger context of national objectives and policy priorities that are decided by the government as a whole. Defence policy, as a subset of Canada’s overall security framework, profoundly influences the nature of the profession of arms in Canada by assigning the mission, roles and tasks to be undertaken by the Canadian Forces and thereby establishes the general type of expertise that members of the profession must master. Given the government’s authority to adjust the boundaries within which the CF operates, these borders are never absolutely rigid and this expertise will vary over time and according to task. The responsibilities inherent in the profession of arms, the identity and the ethos of all military professionals further shape the profession and its relations with civil authority.

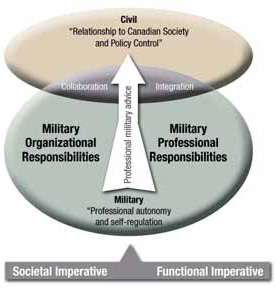

Figure 3-1 The civil-military relationship

This Venn diagram shows how civil and military are affected by societal imperative and functional imperative. The military has organizational responsibilities and professional responsibilities. The military (professional autonomy and self-regulation) provides professional military advice to the civil (relationship to Canadian Society and Policy Control). Both the civil and military communicate their responsibilities through collaboration and integration.

Societal and Functional Imperatives

The very existence of armed forces creates two fundamental imperatives. The left side of Figure 3-1 indicates a societal imperative that the military remain subordinate to civil authority and that it reflect, to an appropriate degree, societal values and norms. The functional imperative depicted on the right side of the figure demands that the military maintain its professional effectiveness for applying military force in the defence of the nation. To achieve the first, the military must be well integrated into its parent society. To achieve the second, the military is distinguished from this society by its unique function. For example, the expertise required to accomplish its mission and the values and norms necessary to sustain a military force in combat are quite different from anything in civil society.

The two imperatives and their associated responsibilities establish the overall framework for civil-military relations in Canada and give rise to two sets of responsibilities for the military, organizational and professional, as indicated in Figure 3-1.

The functional imperative requires that the military be granted a high degree of what is referred to as rightful and actual authority over technical military matters, including those dealing with doctrine, the professional development of its members, discipline, military personnel policy, and the internal organization of units and other entities of the armed forces. Self-regulation in these areas contributes significantly to professional effectiveness. In operations, the military frequently has a high degree of autonomy at the tactical level, but even here, as with the operational level, integrated operations with non-military security partners is increasingly common. The strategic level, however, requires further collaboration and integration at the civil-military interface, and this dynamic relationship defies strict differentiation between the civil and military components of the national security structure.

In essence, there are three sets of civil-military relationships operating in the Canadian context. There is an important relationship between the profession of arms and the society that depends on it for its security. There is also the political and structural relationship with the government, established by law and by custom. The Prime Minister and the Cabinet, through the Minister of National Defence, exercise civil control at this level. Finally, there is an effective relationship with public servants who provide continuity within the overall government structure and manage the bureaucratic administration of government on a day-to-day basis.

In light of this overall structure, it is perhaps not surprising that civilmilitary relations characteristically exhibit a healthy tension between control and oversight, and legitimate autonomy and self-regulation.

The CDS is charged in the National Defence Act with the “control and administration” of the Canadian Forces. Thus, all direction from the Minister of National Defence to the CF is executed through the office of the CDS, and the senior leadership of the profession of arms, led by the CDS, engages in a continuous dialogue with civilian officials and civil authorities to help shape Canada’s security policy. This dialogue begins in National Defence Headquarters and thereafter extends to other government departments and agencies, Cabinet, Parliament, society in general, allies and a number of relevant international organizations.

The CDS and the DM, who together manage the integrated militarycivilian headquarters, draw on the complementary skills of military and civilian personnel to carry out the business of the two organizations. Mutual respect and common understanding of the defence mission ensure that all elements of defence — policy, military strategy, economic/ financial, military/civilian professional development and technology — are coordinated as effectively and efficiently as possible.

Figure 3-2 depicts the relationship between the civilian and military orientations. Politicians and civil servants balance competing demands from a pluralist population and integrate political, social, economic and financial programs to promote the country’s overall well-being. Military professionals advise on what military capabilities are necessary to support these national programs and help formulate security policies that provide the stability and international influence necessary to facilitate long-term success. The area of overlap is a graphic demonstration that the distinction between policy and strategy diminishes as the point of view is raised. Civil authorities must integrate consideration of the means to achieve political objectives, and military professionals must be cognizant of how political factors will influence strategic plans.

Figure 3-2 The Interface between Civilian Policy and Military Strategy

This Venn diagram illustrates the relationship between civilians and the military in Canada. Civilians are responsible for policy, political objectives, and allocation of resources. Military personnel are responsible for professional effectiveness, military doctrine, and military training. Both the military and civilians are responsible for integrating capabilities, national security strategy, and strategic military objectives.

Vigorous, non-partisan debate makes a major contribution to policy decisions. In the final analysis, however, the civil authority decides how the military will be used by setting political objectives and allocating the appropriate resources, while military professionals develop the force to achieve these objectives. Only extensive knowledge and acceptance of the democratic political processes that sustain the Canadian state and its relationship to the international system will allow military professionals to collaborate effectively in this civilmilitary equation.

Page details

- Date modified: