Pilots train for fighter jets at 15 Wing Moose Jaw

News Article / October 24, 2014

By Captain Mark Shular

The temperature is a cool -16C. A light breeze greets us as we walk out of operations area and head towards our aircraft for the flight in a CT-156 Harvard II turboprop tandem seat military training aircraft.

My student is Second Lieutenant Nigel Mahon, and I am his qualified flying instructor (QFI) for his first flight, also known as “clearhood 1”. He has been on his Phase II flight training course for 10 weeks, having completed ground school and flight training device missions to prepare him for this flight. The majority of the course workload and most rewarding challenges are yet to come.

I was in the same shoes years ago, flying the same airframe back in 2009. Now, instead of sitting in the front seat of the Harvard II, I am in the back seat – demonstrating and guiding the student in the basic principles of Canadian military aviation.

As an instructor pilot at 2 Canadian Forces Flying Training School (2 CFFTS), I am just one pilot in a long tradition of flight training at 15 Wing Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan.

The base originally stood up as part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan during the Second World War. In those days, the original Harvard introduced young airmen to the fantasy of flight and the rigours of military aviation. Later, the CT-114 Tutor was the training aircraft of choice, flying above the prairies for more than 40 years.

Today, in cooperation with Bombardier Military Aviation Training (MAT) and many sub-contractors, 2 Canadian Forces Flying Training School employs a mixed fleet of 23 CT-156 Harvard II trainers and 16 CT-155 Hawk jet training aircraft. Since 2000, this military and corporate relationship has produced Phase II (primary flying), Phase III (advanced jet) and Phase IV (fighter lead-in) training.

Students travel to 15 Wing Moose Jaw for Phase II after successfully completing Phase I at Portage La Prairie, Manitoba, on the Grob 120A aircraft. The trainee pilots then complete about 100 hours of training on the Harvard II.

Once they’ve successfully completed Phase II, the students are selected to fly a specific type of airframe for Phase III: multi-engine, helicopter or jet.

Multi-engine and helicopter advanced training courses are taught at 3 Canadian Forces Flying Training School in Portage La Prairie. Students selected to fly jet aircraft stay in Moose Jaw and fly more advanced maneuvers in the Harvard II during Phase III before continuing onto the Hawk for Phase IV transition.

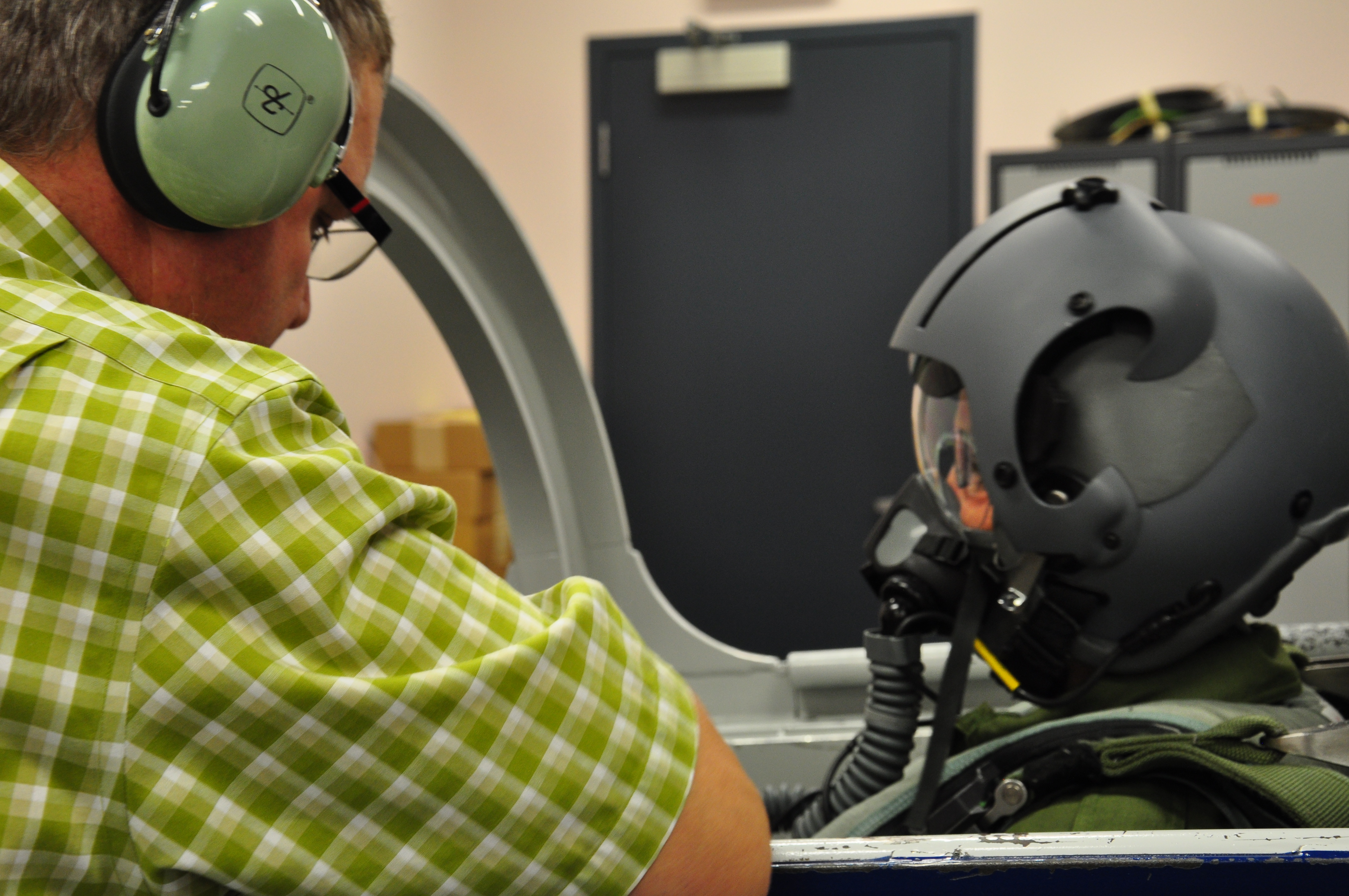

Students undergo Phase IV – Fighter Lead-In Training (FLIT) – flying the Hawk at 419 Tactical Fighter Training Squadron, located at 15 Wing, before ultimately flying the CF-188 Hornet at 410 Tactical Fighter Training Squadron at 4 Wing Cold Lake, Alberta.

A student arriving at Moose Jaw is accommodated in a modern, dormitory-style housing complex and has access to a fully staffed mess kitchen – which enables them to focus their efforts on the workload that will consume most of their time for the next eight to ten months.

Like most flight training courses, there are many ground school classes before students can start up the aircraft for the first time; Phase II flight training is no exception. Students learn aircraft operating instructions, aerodynamics, meteorology, navigation planning and instrument flight rules (IFR). The information starts as a trickle but – as the saying goes – they are soon drinking from a fire hose. Using a building block approach, all topics are tested at the ground school. Students must then demonstrate this knowledge practically in flight training devices and, finally, at an ever-increasing level of proficiency in the aircraft.

The ground school and simulators are handled by former Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) pilots now employed by BMAT as part of the NATO Flying Training in Canada (NFTC) program. BMAT is also responsible for maintaining the fleet of Harvard IIs and Hawks, looking after infrastructure on the base and providing food services for the students. The RCAF provides all in-flight instruction, enforces standards, provides students, provides airspace and dictates the syllabus.

Phase II is divided into four sub-phases of flying: clearhood (basic and aerobatic aircraft handling), instrument, low-level navigation and two-ship formation flying.

The RCAF recently modified the syllabus to optimize the program. When I started Phase II training in 2009, we would carry out a few basic clearhood flight training device missions before moving to flight training. When students progressed, they would return to the flight training device to learn additional new skills. This approach was inflexible in light of the environmental conditions in Moose Jaw.

Now, all basic clearhood and instrument flight training devices are taught in periods of three weeks, which provides scheduling flexibility when the students arrive at the flight line. Students then complete the clearhood phase and basic instrument phase before they return to the flight training devices for enroute instrument and low-level navigation training.

After these flight training devices are completed, the students complete the remaining phases, which normally culminates in the formation phase

The phases themselves are divided into blocks; each block consists of three to five missions where a limited amount of new work is added. In the old syllabus, each mission was scripted – the student was required to fly the set manoeuvres and meet the required levels. The block system allows flexibility to accommodate both weather conditions and students’ learning rates.

The onus is on the students to plan their missions accordingly. If they are strong during certain sequences and weak in others, they can spend more time bringing the items in which they are less proficient up to par. Overall, with the flexibility built into both the schedule and block system, the training program has become more efficient.

A Harvard II instructor like me sees a constant stream of new students showing up to one of three Harvard flights during the year. The school is broken down into three training flights for the Harvard II (Apache, Bandit and Cobra), one training flight for the Hawk (Dragon), a standards flight, and a Flight Instructor School (FIS). Each training flight has their own traditions and methods, but all flights share a common goal: teach basic and advanced military pilot skills to new students.

My student, a member of Apache flight, will be taught by the military instructional method “EDIC”: explain, demonstrate, imitate and critique. Each new manoeuvre is thoroughly explained in the briefing room in a one-on-one setting between the student and the qualified flight instructor. The students are expected to know all the parameters of a manoeuvre from the standard manoeuvre manual (SMM) by the time they reach the flight line. The students know “what” a manoeuvre is; the flight instructors provide the “how” by leveraging their previous experience and training.

During the briefing, the instructor confirms a student’s SMM knowledge by asking questions. If the student answers correctly, the instructor continues and explains key points of each manoeuvre. These key points need to be accomplished for the successful completion of a sequence.

For example, we fly a loop (360 degrees direction change in the vertical) at 230 knots, pull between 3 to 4 Gs and, after 360 degrees of direction change in the vertical, we exit at 230 knots straight and level. That is essentially SMM knowledge; I would explain the “how” as follows:

“Pull 3.5 G to set the ‘rate’ [that the nose of the aircraft is travelling across the sky]; over the top of the loop, freeze the stick to maintain that rate and, off the backside of the loop, maintain that rate to the horizon.

“My own technique is to aim for 180 knots when passing 45 degree nose down. If you are slower than 180 knots, decrease your rate of nose travel to the horizon and if faster increase your rate.”

Each manoeuvre, from basic 45-degree turns to advanced aerobatics such as vertical rolls or instrument approaches, is explained in the same fashion. Once in the air, I briefly go over the key points and then demonstrate the manoeuvre.

The demonstration must be conducted with a high degree of proficiency to appeal to a student’s sense of “primacy”; that is, the first time a student sees an event, that event will be remembered above all else. I direct the student to “follow through” on the controls to provide a sense of intensity and to promote muscle memory. The student is then directed through the manoeuvre to focus attention on the key points that were briefed on the ground.

Once my demonstration is complete, it is the student’s turn, which is the “imitate” component of EDIC. The student tries the manoeuvre and, once complete, I offer my critique of the performance. Using fault analysis, I comment on what the student did well, what areas need improvement, and how to make that improvement.

Even during the first clearhood flight, the student is expected to transfer their knowledge and skill from ground school and the simulation missions to the air. Using the building block approach, the instructor demonstrates every event and the student practices it soon after. The normal flow for clearhood 1 is a take-off, departure to the training areas and then a slow flight stall sequence to demonstrate the basic handling capabilities of the Harvard II.

Once the area work is done, we return to base to do some pattern work. During clearhood 2, the student flies all maneuvers previously demonstrated and should be already showing proficiency in some of them. The student adds additional maneuvers to each trip, including overhead breaks, flapless approaches, unusual attitude recoveries and aerobatics (such as loop, rolls, cloverleafs, Cuban 8s and more.) Within eight flights, the student is expected to fly the aircraft solo in the pattern.

After a student’s first solo flight, it is traditional for his or her course mates to give the student a “solo dunking” in the flight line bathtub.

The instrument phase teaches basic instrument flying skills such as turns to headings, standard rate climbs and turns, VOR radial interception and tracking, holds, and full instrument approaches.

The missions are first flown in the training area and progress to flights to Swift Current, Regina and Saskatoon for actual instrument procedure experience.

The navigation phase teaches the student low-level visual navigation. These missions are flown at 500 feet (152 metres) above ground and timed to simulate a tactical environment; +/- 10 seconds is the allowable margin of error over the target.

The students make their own maps – following approved routes – throughout southern Saskatchewan. Some of the skills that they must demonstrate include timing and track corrections, low level awareness, and mental dead reckoning to an impromptu target.

The final phase of training is the formation phase; two students are paired up and fly in close formation with one another, under the watchful eye of their instructors. The students practice maintaining a position approximately 10 feet (three metres) from the lead aircraft as well as rejoining to these positions.

The students lead for half the mission and then fly as wingman thereafter. This is a change from years past; previously the instructor flew the other aircraft as the lead. Now students plan and fly the whole mission, which develops the “thinking wingman” concept. If they know how to lead another aircraft, they will know what is next and can anticipate position changes, radio frequency changes and cue their lead if something unwanted develops.

At the end of each phase students are flight tested by a member of the standards section. The students fly as if they are solo – making all decisions affecting the flight. The “snapper” (standards pilot) only takes control of the aircraft if a dangerous situation is developing or if mission flow needs to be streamlined.

Although there are many aircraft in the RCAF that have crews, Canada’s front line fighter is single seat. As a result, all Phase II students must have a “solo pilot” mentality.

The students are then ranked according on their flying performance, academics and officer development. The students may indicate their preference of communities (multi-engine, helicopter or jet) but the needs of the RCAF are the overriding factor.

The students selected to fly jets continue to fly the Harvard II and continue to developing that single seat fighter mentality.

They fly advanced clearhood sequences such as maximum performance turns, vertical aerobatics, simulated “engine out” approaches or practice forced landings.

During the instrument portion of Phase III, students plan and execute a trip, both within Canada and the United States, to further develop their instrument flight rules (IFR) skills. The navigation phases teach the student how to integrate the GPS into their low-level skills. The formation phase introduces tactical formations such as double attack (line abreast at about one mile or 1.6 kilometres), which they will further develop as they continue in their fighter training.

Graduation day marks the successful completion of Phase III.

This is a momentous day for graduates and includes an opportunity for them to showcase their talents in a formation flypast. Afterwards, Canadian Armed Forces pilots' wings are presented at a ceremony attended by fellow students, instructors, family, friends and guests. It is only with wings on their chest that they can truly call themselves RCAF pilots for the first time.

The newly-winged pilots then take on the challenge of flying the Hawk single engine jet trainer.

This phase is about 50 hours of “transition” flying. The students know how to safely fly clearhood, instruments, navigation and formation missions on the Harvard II; now they must adapt to a much faster aircraft.

Phase IV showcases the jet’s better range, climb rate, more sustained Gs and more complex systems. It is, again, a building block approach with the ultimate goal of preparing students to be successful on the Hawk at Fighter Lead-In Training at 419 Tactical Fighter Training Squadron at Cold Lake and, ultimately, on the CF-188 Hornet.

Flight training at 2 Canadian Forces Flying Training School is a unique experience; students have access to student-focused teaching tools, and state of the art, high-performance aircraft and facilities. In addition, through their instructors, they are also able to draw upon a vast amount of real-life experience that differs significantly from that available at any other flying training school.

Captain Shular is an instructor at 2 Canadian Forces Flying Training School.