Evaluation of the Canada Disability Savings Program, 2025

On this page

- List of abbreviations

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Introduction

- Executive summary

- Management response and action plan

- Program background and description

- 1. Outreach and awareness

- 2. Barriers and facilitators to opening and maintaining an RDSP

- 3. The role of the CDSG and the CDSB in motivating savings

- 4. Early impacts of the RDSP on quality of life or well-being

- Conclusion

- Recommendation and observation

- Appendices

Alternate formats

Evaluation of the Canada Disability Savings Program [PDF - 2 631 KB]

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

List of abbreviations

- AHA

- Assistance Holdback Amount

- CBO

- Community-based organization

- CDSP

- Canada Disability Savings Program

- CDSG

- Canada Disability Savings Grant

- CDSB

- Canada Disability Savings Bond

- CRA

- Canada Revenue Agency

- CSD

- Canadian Survey on Disability

- DAC

- Disability Advisory Committee

- DAP

- Disability Assistance Payments

- DTC

- Disability Tax Credit

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- LDAP

- Lifetime Disability Assistance Payments

- MCA

- Multiple Correspondence Analysis

- PMEC

- Performance Measurement and Evaluation Committee

- PRA

- Prairie Research Associates

- SDSP

- Specified Disability Savings Plan

- SSPD

- Special Services to Persons with Disabilities

- RDSP

- Registered Disability Savings Plan

- RRSP

- Registered Retirement Savings Plan

- T1FF

- T1 Family File

List of figures

- Figure 1: First hearing about RDSPs

- Figure 2: RDSP take-up rate among eligible DTC holders under 50, by income level (%), 2010 to 2021

- Figure 3: Ease of setting up an RDSP for the first time

- Figure 4: Proportion of RDSPs in which private contributions have been made, 2010 to 2021

- Figure 5: Average contribution amounts by income level, 2010 to 2021

- Figure 6: Proportion of DTC-approved individuals aged between 0 and 49 years old from low-income families, who received either bonds only, grants only or both

- Figure 7: Proportion of DTC- approved individuals aged between 0 and 49 years old from modest-income families, who received either bonds only, grants only or both, 2010 to 2021

- Figure 8: Benefits from an RDSP

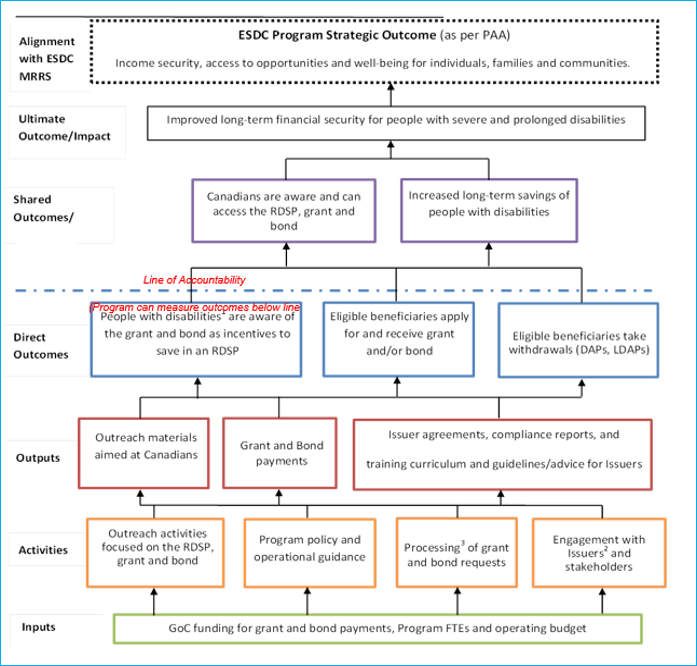

- Figure 9: Canada Disability Savings Program logic model

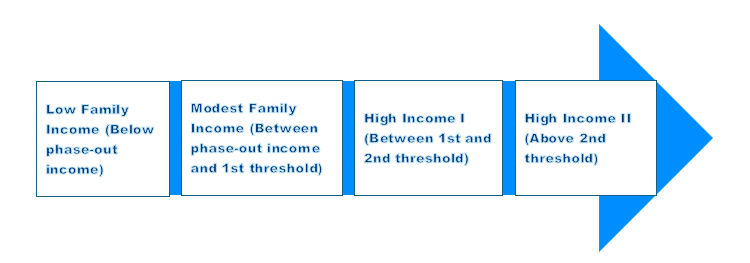

- Figure 10: Family income levels

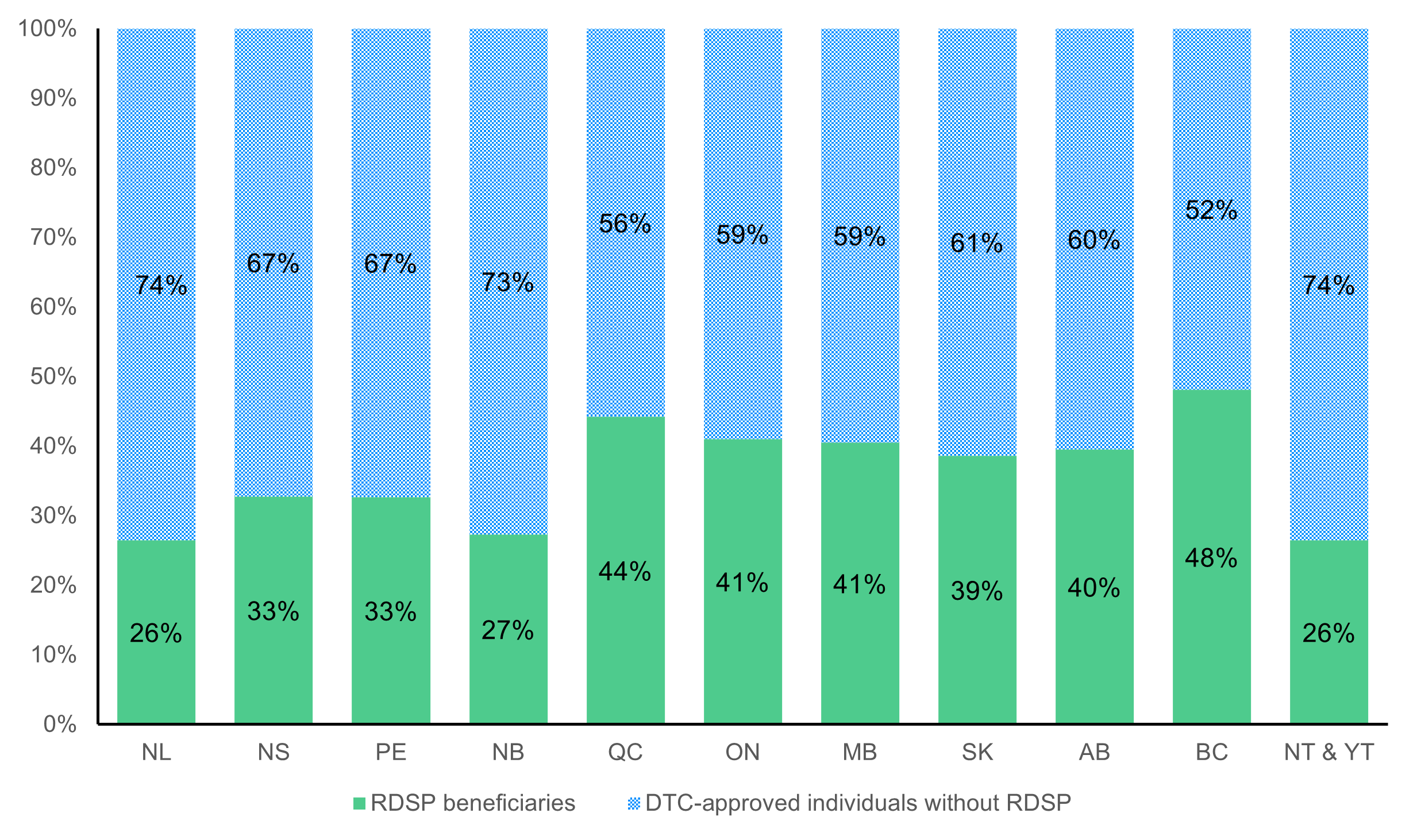

- Figure 11: Proportion of RDSP beneficiaries (RDSP take-up rate) among low and modest income DTC-approved individuals and proportion of DTC-approved individuals without RDSP, by provinces and territories (%), 2021

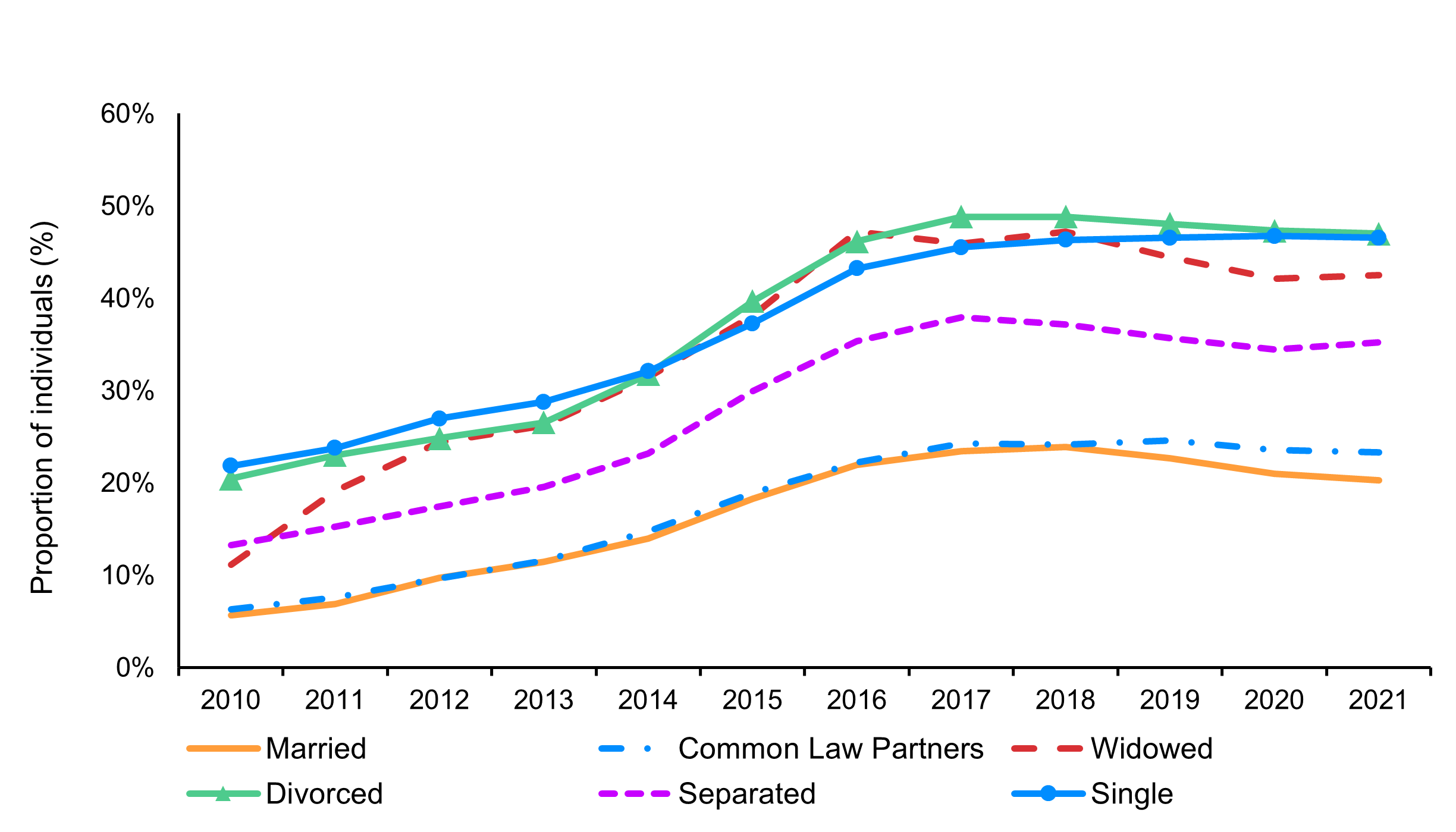

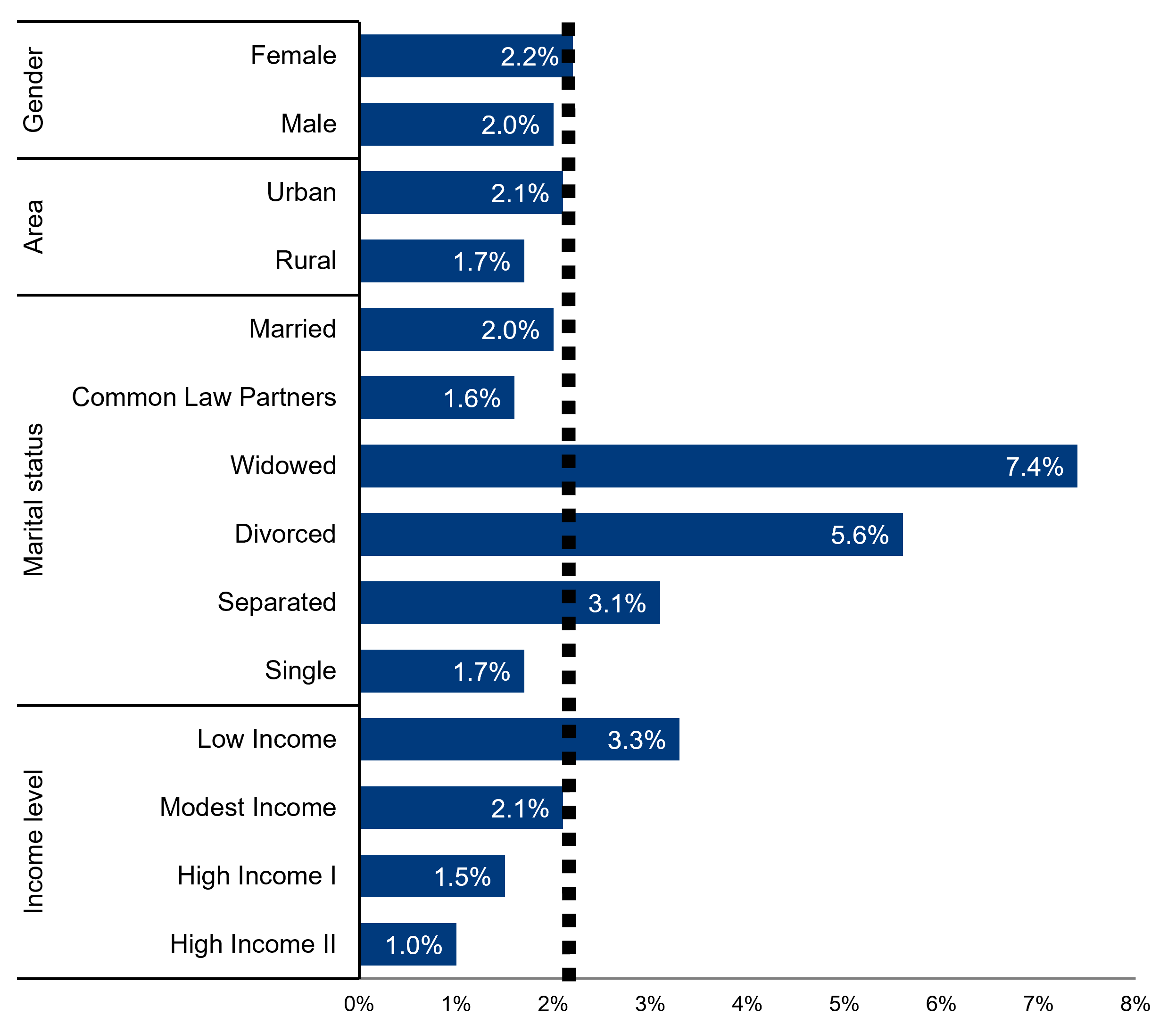

- Figure 12: RDSP take-up rate among eligible DTC holders, by marital status (%), 2010 to 2021

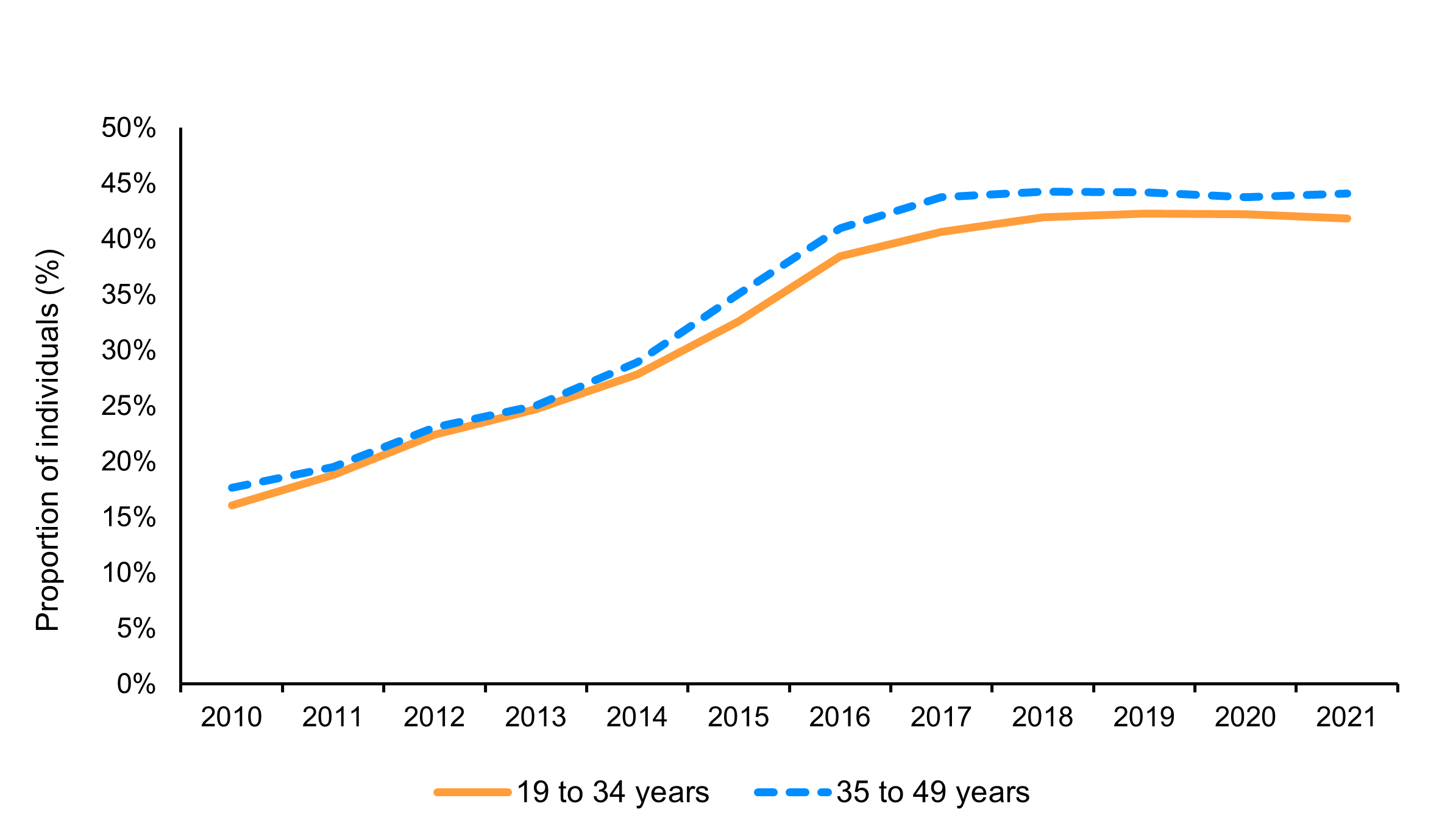

- Figure 13: RDSP take-up among eligible DTC holders, by age group (%), 2010 to 2021

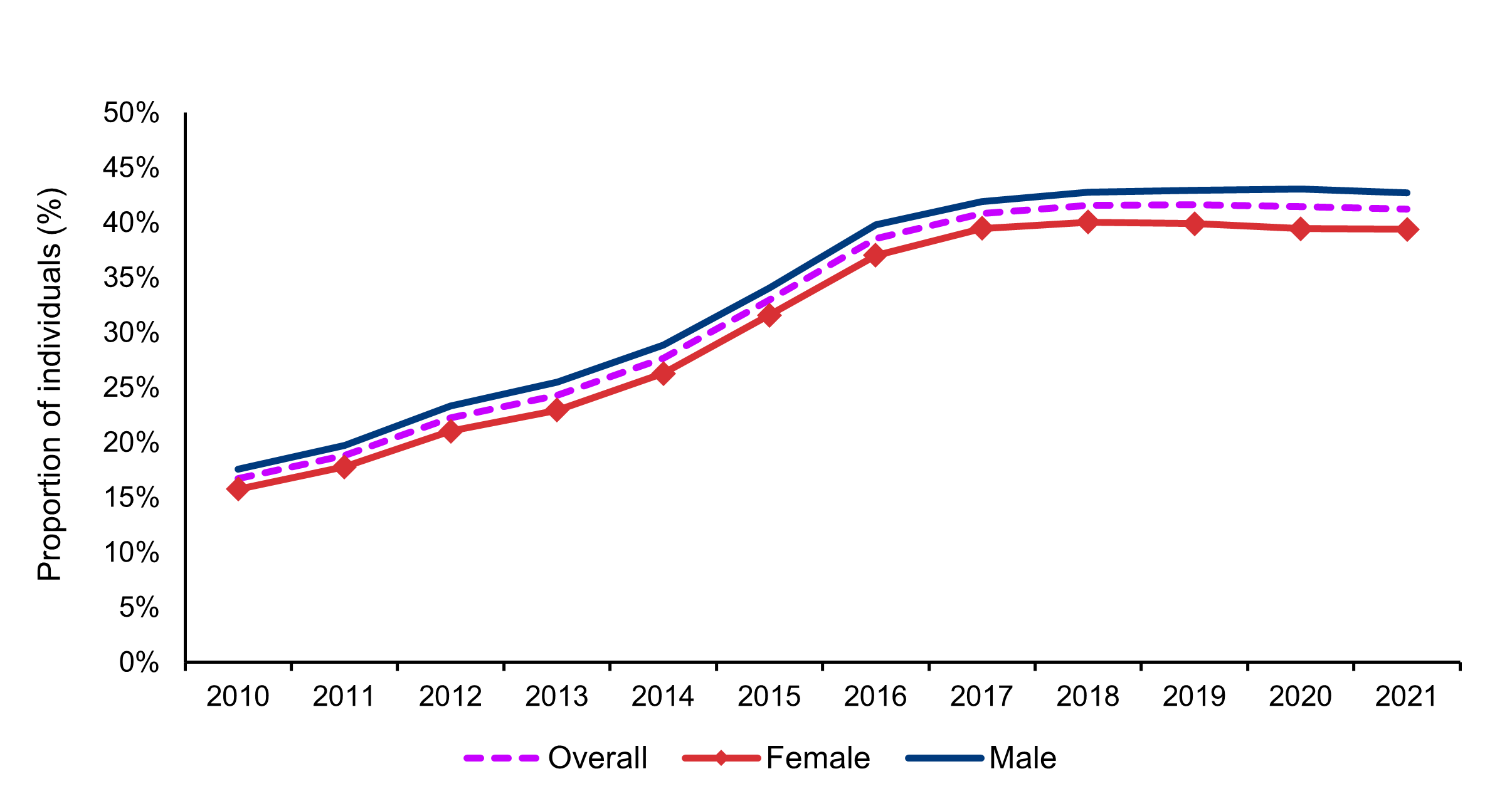

- Figure 14: RDSP take-up rate among eligible DTC holders, by gender (%), 2010 to 2021

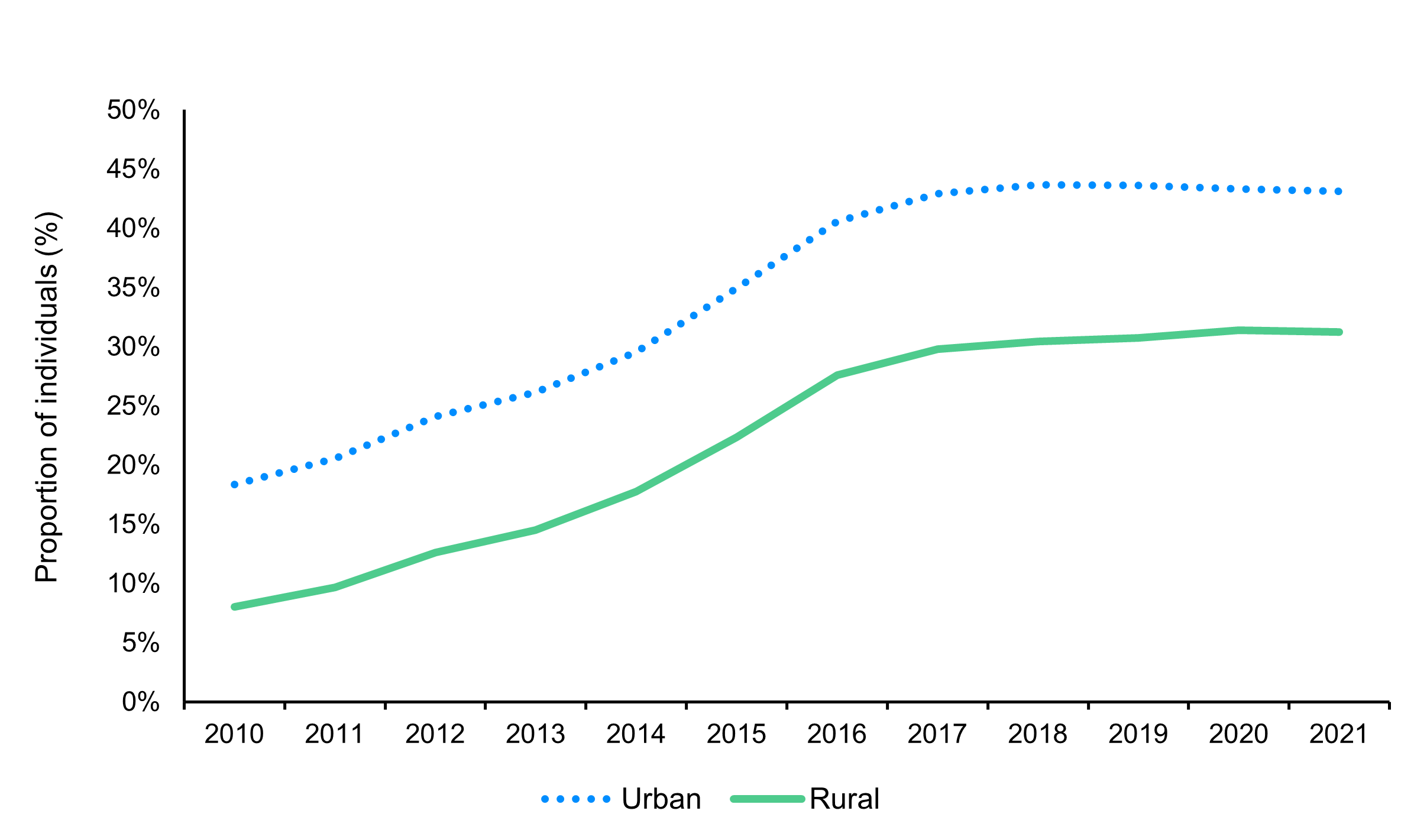

- Figure 15: RDSP take-up rate among eligible DTC holders, by urban and rural areas (%), 2010 to 2021

- Figure 16: Proportion of RDSP beneficiaries who withdraw money from their account, average for 2012 to 2021 (%)

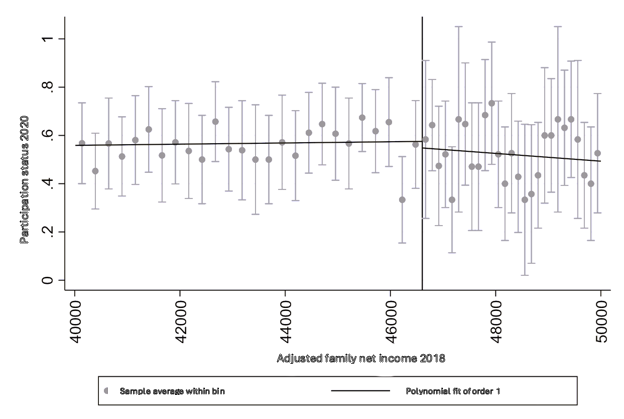

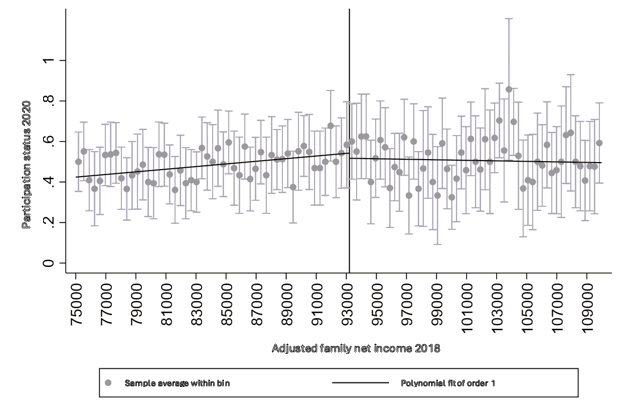

- Figure 17: Regression discontinuity analysis for low and modest income, 2020

- Figure 18: Regression discontinuity analysis for high income, 2020

List of tables

- Table 1: Management action plan

- Table 2: Distinct count of RDSP beneficiaries, as of December 31, 2023

- Table 3: CDSP financial summary (from inception to December 31, 2023)

- Table 4: CESP annual grant

- Table 5: CESP annual bond

- Table 6: CDSP annual grant

- Table 7: CDSP annual bond

- Table 8: RDSP take-up rate (2014 to 2021)

- Table 9: Examples of barriers

- Table 10: Difficulties getting approval for DTC

- Table 11: Reasons for contributing to other savings

- Table 12: Other savings plans or accounts

- Table 13: CDSP income levels and corresponding CDSG and CDSB, 2023

- Table 14: Income threshold definitions

- Table 15: Income thresholds used to determine eligibility

- Table 16: Actual spending (2017 to 2018, 2023 to 2024)

- Table 17: RDD estimation of the impact of being eligible for bonds, Low and Modest income in 2020

- Table 18: RDD estimation of the impact of being eligible for grants for high income in 2020

Introduction

The Canada Disability Savings Program (CDSP) was introduced in 2008 to encourage long-term savings into Registered Disability Savings Plans (RDSP).

The Program uses two main savings incentives to support these objectives:

- the Canada Disability Savings Grant (CDSG): an incentive paid by the Government of Canada into a RDSP based on private contributions made

- the Canada Disability Savings Bond (CDSB): an incentive for low- and modest-income individuals, paid into their RDSPs without any required contribution

This evaluation examines the effectiveness of the Program using data from 2017 to 2021, by assessing the progress made towards the achievement of the following two key outcomes:

- increased awareness among program beneficiaries, their family members, and their caregivers of the benefits of contributing to RDSPs

- increased long-term savings of beneficiaries in RDSPs

The evaluation has 5 main questions to evaluate the Program's contribution towards these outcomes:

- How have communication and outreach strategies of ESDC and other partners helped in raising awareness among persons with disabilities, their families and others (friends, former colleagues, organizations, etc.) concerning accessing the RDSP (the CDSG and/or CDSB)?

- What are the efforts made by ESDC to engage with key program stakeholders as well as provincial/territorial counterparts, with regards to the promotion of the program?

- What are the barriers or facilitators for those persons with disabilities who have been approved for the DTC and those who may provide them with support to open and maintain an RDSP?

- To what extent do the CDSG and CDSB motivate eligible beneficiaries or plan holders to save money into a RDSP?

- What are the early impacts of the program on the quality of life or well-being of program beneficiaries and/or plan holders?

Executive summary

Key findings

Improvements in communication and outreach

- ESDC collaborated with partners to improve awareness of the Registered Disability Savings Plan (RDSP) among persons with disabilities

- Mass mail-outs from CRA / ESDC were effective in encouraging beneficiaries and plan holders to open an RDSP. Community-based Organizations (CBOs) also played an important role in encouraging applications and supporting individuals to apply for and open an RDSP

- Two key areas for improvement were the need for more one-on-one support for prospective plan holders to apply for and open an RDSP, and the need to improve the targeting of outreach efforts to different situations

Ongoing barriers to opening an RDSP

- Finding knowledgeable financial institutions that offer the RDSP remains a challenge, which in some cases delays account opening. However, the process is becoming easier than in previous years

- The complexity of the application process and the effort required were common barriers for potential beneficiaries and/or plan holders

Motivating savings

- The CDSP grants and bonds motivate saving for the future

- The extent to which plan holders choose to save outside an RDSP is unclear. For those who did, it was often due to a perception that other plans were better suited to the realities of persons with disabilities

Challenges related to rules and restrictions of the RDSP

- Plan holders, beneficiaries, and other stakeholders felt that certain aspects of the RDSP were not well adapted to the specific needs and circumstances of persons with disabilities

- Key challenges were related to penalties for early withdrawals, and certain age limits associated with the eligibility for the grants and bonds

Contributing to confidence in future financial security

- The CDSP has the potential to improve the quality of life and/or well-being of beneficiaries and/or plan holders in the future, though there may be limitations in certain contexts

- The program helps improve the confidence of plan holders and beneficiaries in meeting future financial needs

- Only a small proportion of beneficiaries have withdrawn funds to date, but a significant number of those who did faced penalties for early withdrawal. The need to withdraw funds was often related to day-to-day and health/disability-related expenses

Recommendation and observation

Recommendation 1: It is recommended that the Program continue to work with, and support partners and stakeholders, particularly community-based organizations, to improve their capacity to promote the RDSP and the grant and bond, broaden outreach and communication efforts, and provide more one-on-one support as required by certain individuals to open and maintain an RDSP.

Observation 1: In light of the interdependency between the Canada Disability Savings Program (CDSP) and the Registered Disability Savings Plan (RDSP) and their respective policy objectives, the Program could work with partners to continue to explore ways to better respond to the unique needs of persons with disabilities. Focus could be placed on identifying barriers some individuals may face in opening an RDSP or realizing the full potential of the CDSP and RDSP for long-term saving.

Management response and action plan

Overall management response

The Canada Disability Savings Program (CDSP) was introduced in 2008 to encourage Canadians with severe and prolonged disabilities and their families to save for the future. The program has two main incentives to encourage savings into Registered Disability Savings Plans (RDSP): the Canada Disability Savings Grant (grant) and the Canada Disability Savings Bond (bond).

The program complements other government measures that help support financial security for people with disabilities. As the bond is available to low-and modest-income beneficiaries without requiring any contribution to the RDSP, it reflects the Government of Canada's broader commitment to poverty reduction.

Program administration and delivery are a shared responsibility among Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC or the Department), the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), the Department of Finance Canada, and participating financial institutions (issuers). ESDC's key responsibilities include program policy, interpretation of the Canada Disability Savings Act and Regulations, reporting on program performance, issuing statements of entitlement for grants, public outreach, and the service delivery. The Department of Finance is responsible for the savings vehicle, including the requirements for opening an RDSP and withdrawing from it.

The Department acknowledges that the responsibilities and the rules around RDSPs, the grant, and the bond are complex. The Department agrees with the recommendation and remains dedicated to promoting awareness and improving understanding of the program among the disability community. The Department also takes note of the observation and will continue to look at ways to better respond to the unique needs of persons with disabilities, while being mindful that changes to Plan requirements are the prerogative of the Department of Finance.

Recommendation

It is recommended that the Program continue to work with and support partners and stakeholders, particularly community-based organizations, to improve their capacity to promote the RDSP and the grant and bond, broaden outreach and communication efforts, and provide more one-on-one support as required by certain individuals to open and maintain an RDSP.

Management response

The Department agrees with the recommendation and recognizes the critical role that community-based organizations play in reaching persons with disabilities and helping them access the RDSP, the grant, and the bond.

The Department recognizes the importance of broadening outreach and communication efforts. The Department also acknowledges that beneficiaries have different levels of awareness and has been taking steps to ensure effective and clear communication for clients. The Department continues to collaborate with partners with the specific goal of increasing program awareness. As of December 31, 2023, there were more than 282,000 active RDSPs.

Since the last evaluation reference period ended, the Department and partner organizations undertook the following actions to promote and increase access to the program:

- in 2022, web pages for the RDSP, the grant, and the bond were redesigned to improve accessibility, clarity, and user experience, resulting in increased web traffic. Further improvements were introduced through updates to the grant and bond application forms and policy changes permitting alternative consent methods, such as electronic or recorded consent, making the application process more accessible

- in 2023, the CRA launched a fully digital Disability Tax Credit (DTC) application process, making it faster and easier for persons with disabilities and medical practitioners to complete the DTC application form

- in 2024, ESDC's Social Development Partnerships Program - Disability component (SDPP-D) started funding not-for-profit community-based organizations to help address long-standing barriers related to awareness and take-up of benefits among persons with disabilities, including but not limited to the DTC, opening an RDSP, and many provincial and territorial disability benefits. Funded organizations may provide accessible, individualized disability benefits navigation support on a one-on-one basis

- in 2024, in response to stakeholder feedback, the CDSP team developed a new plain-language infographic, outlining the steps to open an RDSP. This bilingual, accessible resource has been published online, shared via email, and distributed at events

These novel undertakings build on the continuous efforts made by the Department and its partners to actively raise program awareness. This includes CDSP's active promotion and engagement through conferences, outreach events, and webinars targeted at disability communities, both in-person and virtually. Between January and December 2024, the team delivered 76 webinars, an increase from 70 in 2023, often in collaboration with the CRA or community-based organizations. These sessions provided information on the DTC, RDSP, grant, and bond, along with practical guidance on how to open a plan and its related benefits. Additionally, to further encourage participation, CDSP has continued to issue direct mail-outs to DTC-approved individuals who have not opened an RDSP. Since 2021, over 2 million promotional letters have been issued.

Management action plan

The Department remains committed to strengthening partnerships and maximizing the program's impact within its budgetary limits. In response to the recommendation, the Department will continue working with partners to raise awareness of the RDSP, the grant, and the bond among eligible Canadians and their families.

| Element | Management action plan | Estimated completion date |

|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | Strengthen partnerships with community-based organizations to review options for improving program engagement | March 31, 2026 |

| 1.2 | Review existing communications products and work with stakeholders to improve these products and provide simpler and clearer information on RDSP, grants and bonds | March 31, 2026 |

| 1.3 | Work with ESDC's Public Affairs and Stakeholder Relations Branch (PASRB) and partners such as the Canada Revenue Agency and Service Canada to improve outreach and communication strategy | December 31, 2026 |

| 1.4 | Leverage Canada Disability Benefit (CDB) promotional efforts to increase RDSP, grant and bond awareness | December 31, 2026 |

Program background and description

In 2006, an Expert Panel appointed by the Government of Canada explored approaches to assist parents (and others) to save for the long-term financial security of persons living with disabilities. In Budget 2007, based on recommendations proposed by the Panel, the Government announced the tax-deferred Registered Disability Savings Plan (RDSP). The RDSP became available to Canadians in December 2008. It was introduced to help persons with disabilities improve their long-term financial security by providing a tool to encourage individuals and their families to save for the future.

The Canada Disability Savings Program is jointly managed by Employment and Social Development Canada and the Canada Revenue Agency, which is also responsible for administering the Disability Tax Credit. The legislative authority for the Canada Disability Savings Grant and Canada Disability Savings Bond is the Canada Disability Savings Act and the Canada Disability Savings Regulations, for which Employment and Social Development Canada is responsible. Plans are governed by the Income Tax Act, for which the Department of Finance has responsibility.

The CDSP is comprised of two federal savings incentives that the Government transfers into an active RDSP on an annual basis, including:

- the Canada Disability Savings Grant (CDSG) - an incentive paid by the Government of Canada into a RDSP if the required contributions are made

- the Canada Disability Savings Bond (CDSB) - an incentive paid to low- and modest-income individuals without any required contribution

The CDSG amount is determined based on the value of the personal contributions and varies based on the beneficiary's adjusted net family income. The contribution matching rate is higher for low and modest-income families. In addition, eligible low- and modest-income families can obtain the CDSB without having to make personal RDSP contributions.

The Government CDSG and CDSB are available to eligible beneficiaries up to December 31st of the year that they turn 49. Withdrawals must commence by December 31 of the year the beneficiary turns 60. At any age, withdrawals can be made without repayment obligation if more than 10 years have elapsed since the last grants and bonds were paid into the plan.

Eligibility

To be eligible for the RDSP, an application for the Disability Tax Credit (DTC) must have been submitted to the Canada Revenue Agency for the intended beneficiary and they must have been deemed eligible for the credit by the agencyFootnote 1. To be eligible for the DTC, individuals must have an impairment in physical or mental functions that is severe and prolonged, resulting in a marked restrictionFootnote 2.

The DTC is a non-refundable tax credit that can be claimed by eligible individuals to reduce taxes owing, in recognition of their non-itemizable disability-related costs.

The RDSP is not the only program whose eligibility is tied to the DTC. Other programs include the Child Disability Benefit and the Canada Workers Benefit Disability Supplement as well as the newly introduced Canada Disability Benefit.

Assistance Holdback Amount

The total grant and bond that has been deposited into an RDSP within the previous 10 years is referred to as the Assistance Holdback Amount (AHA)Footnote 3.

Regular withdrawals from the plan must begin by December 31 in the year the beneficiary turns 60. A beneficiary may withdraw money from the account prior to age 60, subject to the terms and conditions of a particular RDSP. However, they may need to repay some, or all, of the Canada Disability Savings Grant (CDSG) and Canada Disability Savings Bond (CDSB) when making a withdrawal. To discourage early withdrawals, withdrawals before the age of 60 are subject to repayment of some or all grant and bond that has been deposited into the RDSP within the previous 10 yearsFootnote 4.

The RDSP is a long-term savings plan. As such, the CDSG and CDSB are intended to encourage long-term savings and must generally remain in an RDSP for at least 10 years. When money is withdrawn, generally all or part of the Assistance Holdback Amount (i.e., grants and bonds that have been in the RDSP for fewer than 10 years) must be repaid to the Government. However, through the Specified Disability Savings Plan, beneficiaries with a shortened life expectancy (i.e., of five years or less) can withdraw up to $10,000 per year in taxable savings without any requirement to repay grant and bond amounts, subject to certain conditions.

Key actions since the 2019 evaluation

Since the last evaluation report of the CDSP in 2019, the Government took action to increase access to the CDSP and RDSP, and provide better support to persons with disabilities, including the following:

- 2019: The requirement to close an RDSP and repay grants and bonds when a beneficiary no longer qualifies for the Disability Tax Credit is eliminated

- 2021: Eligibility criteria for the Disability Tax Credit are revised to better recognize mental functions necessary for everyday life, and time spent on life-sustaining therapy. Amendments are also made to deem individuals with Type 1 Diabetes as meeting the updated criteria

- 2023: To improve access to RDSPs and ensure family members can replace each other as plan holder when one of them dies, Budget 2023 expanded the definition of a qualifying family member to include siblings of the RDSP beneficiary and provided an extension of the measure until the end of 2026

- 2023: The Canada Disability Benefit Act receives Royal Assent. Under the Act, a new Canada Disability Benefit will be provided annually by the federal government to support low-income, working-age Canadians, who are eligible for the DTC

- 2023: The Canada Revenue Agency launches a fully digital application process, making it faster and easier than ever for persons with disabilities and their medical practitioners to complete the Disability Tax Credit application form

- 2025: The Canada Disability Benefit Regulations came into force in May. It is expected that payments will begin in July 2025, providing up to $2,400 annually

Cumulative number of RDSP beneficiaries

Between the introduction of the RDSP in 2008 and December 2023, 303,389 RDSPs have been opened by persons with disabilities or their families/caretakers.

| Description | Persons |

|---|---|

| Cumulative number of RDSP beneficiariesFootnote 5 | 303,389 |

| Number of beneficiaries with an active RDSPFootnote 6 | 282,210 |

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC, 2025), Canada Disability Savings Program: 2023 Annual Report

By the end of 2023, a total of about $4.48B CDSG payments and a total of about $1.86B CDSB payments were made into these plans. During the same period, personal contributions made amounted to approximately $2.93B.

| Description | Amounts (billions $) |

|---|---|

| Cumulative contributions | 2.93 |

| Cumulative CDSGFootnote 7 | 4.48 |

| Cumulative CDSBFootnote 7 | 1.86 |

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC, 2025), Canada Disability Savings Program: 2023 Annual Report

Comparing the CDSP with the CESP

The CDSP provides higher annual maximum amounts and cumulative ceilings for bonds and grants than similar savings programs. However, obtaining the maximum $90,000 in grants and bonds available from the RDSP requires meeting various eligibility requirements. Some beneficiaries may not meet the thresholds to obtain the maximum or partial bond, or the most advantageous matching rates. Some beneficiaries and their families may not be able to make sufficient personal contributions to receive the full grant amount.

| Adjusted family net income for 2024Footnote 8 | Basic CESG on the first $2,500 of annual RESP contribution | Additional amount of the CESG on the first $500 or less of annual RESP contribution | Maximum yearly CESG depending on income and contributions | Lifetime maximum CESG (basic and additional combined) | Lifetime limit contribution | Annual limit of CESG (basic and additional combined) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than $55,867 | 20% = $500 | 20% = $100 | $600 | $7,200 | $50,000 | $600 or $1,100 with carry forward |

| Between $55,867 and $111,733 | 20% = $500 | 10% = $50 | $550 | $7,200 | $50,000 | $550 or $ 1,050 with carry forward |

| More than $111,733 | 20% = $500 | Beneficiary is not eligible | $500 | $7,200 | $50,000 | $500 or $1,000 with carry forward |

| Adjusted family net income for 2024 | Less than $55,867 | Between $55,867 and $111,733 | More than $111,733 |

|---|---|---|---|

| No contribution required | $500 first year, plus $100 for each year of eligibility | Not eligible | Not eligible |

| Lifetime maximum of Canada Learning Bond | $2,000 | Not eligible | Not eligible |

| Adjusted family net income for 2024 | $111,733 or less | More than $111,733 |

|---|---|---|

| Grant depending on income and contributions | $111,733 or less | More than $111,733 |

| Maximum yearly CDSG depending on income and contributionsFootnote 9 | First $500 is matched at 300% = $1,500 Next $1,000 is matched at 200% = $2,000 |

First $1,000 is matched at 100% = $1,000 |

| Lifetime maximum of CDSG | $3,500 | $1,000 |

| Lifetime limit of contribution | $70,000 | $70,000 |

| Adjusted family net income for 2024 | $36,502 or less | Between $36,502 and $55, 867 |

|---|---|---|

| No contribution requiredFootnote 10 | $1,000 | Less than $1,000 |

| Lifetime maximum | $20,000 | $20,000 |

1.Outreach and awareness

1.1 ESDC worked with partners to improve awareness of the RDSP

Since the previous evaluation in 2019, a broader and more diverse approach to engaging with potential beneficiaries has been a focus of the Program.

ESDC worked with partners to enhance communication and outreach strategies in efforts to improve awareness of the RDSP among persons with disabilities and their families/caregivers. Key examples of these efforts included:

- the implementation of easier-to-read materials

- mass mail outs

- improvements to website information accessibility

- webinars, training for issuers

- increased partnerships with non-governmental organizations

The promotional efforts most frequently identified by key informants includeFootnote 11:

- Communication from the Government of Canada, such as:

- the ESDC/CRA mailouts (22/37)

- joint ESDC/CRA presentations or webinars for community-based organizations (CBOs) (11/37)

- the Government of Canada website (14/37)

- Communication from community-based organizations, such as:

- general advertising or awareness building (10/37)

- one-on-one support to potential beneficiaries (7/37)

- workshops and information sessions (7/37)

- the provision of information (responsive) (6/37)

- Communication from financial institutions, such as:

- bank web pages (9/37)

- a centralized call line (8/37)

- paper educational materials, and the provision of information through unrelated interactions such as meetings with bank staff (4/37)

- Communication from provinces and territories, such as:

- participation in action groups or committees (6/37)

- grants to community-based organizations (5/37)

- web pages (3/37)

- financial incentives (2/37)

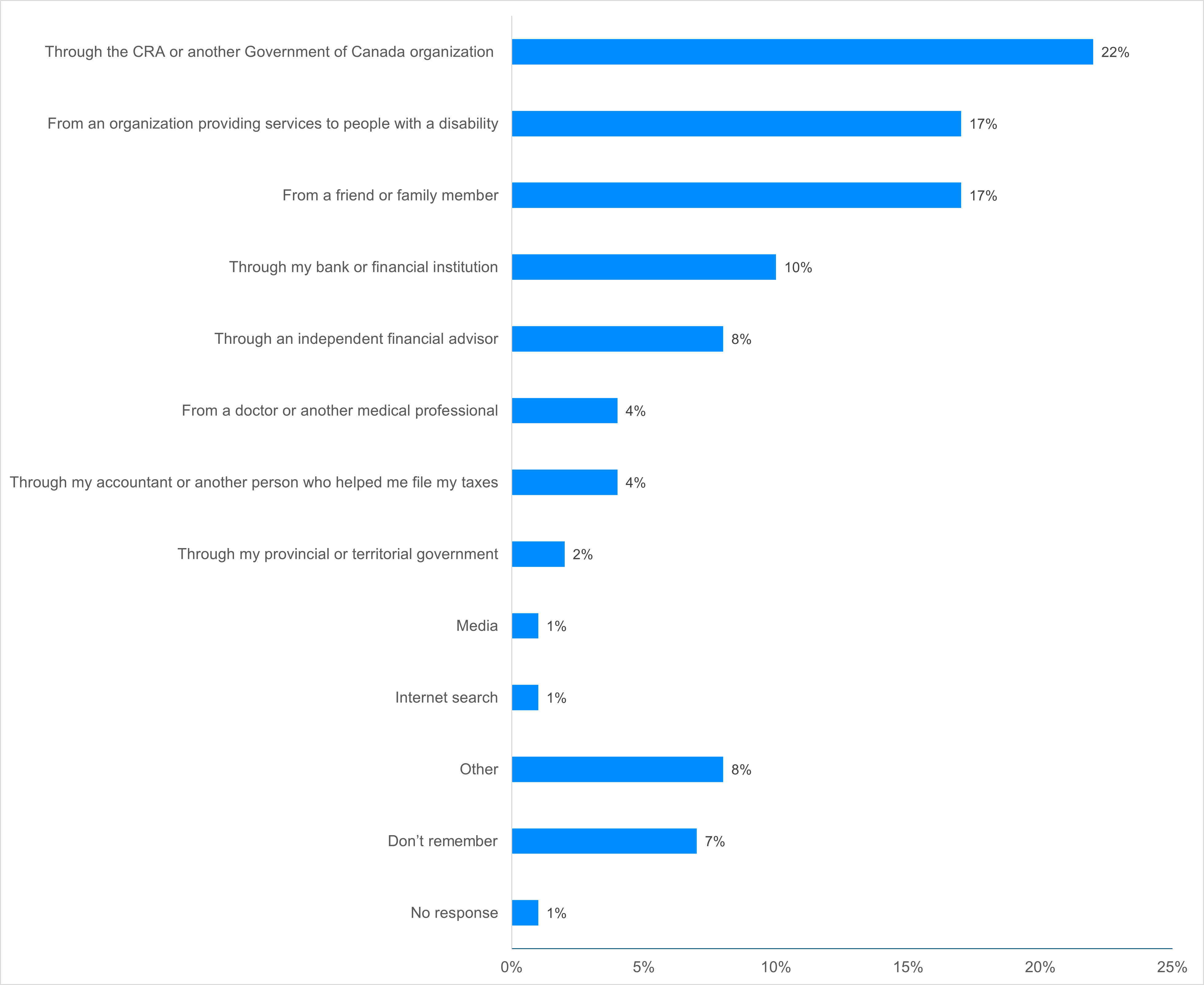

The survey results show that RDSP holders first learned about the Plan through both formal and informal channels.

The most frequently identified channels of information were the following:

- CRA and other federal departments (22%)

- organizations serving persons with disabilities (17%)

- friends and family members (17%)

RDSP holders learn about the program from a variety of stakeholders including the government, community-based organizations, banks or financial institutions, independent financial advisors, medical professionals, accountants or provincial governments.

Figure 1: Text description

| Response | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|

| Through the Canada Revenue Agency or another Government of Canada organization | 22% |

| From an organization providing services to people with a disability | 17% |

| From a friend or family member | 17% |

| Through my bank or financial institution | 10% |

| Through an independent financial advisor | 8% |

| From a doctor or another medical professional | 4% |

| Through my accountant or another person who helped me file my taxes | 4% |

| Through my provincial or territorial government | 2% |

| Media | 1% |

| Internet search | 1% |

| Other | 8% |

| Don't remember | 7% |

| No response | 1% |

- Source: PRA (2024). Survey for the Evaluation of the CDSP, conducted for ESDC’s Evaluation Directorate. Unpublished technical report.

- Note: Figure 1 shows the different communication channels through which RDSP holders heard about the RDSP for the first time, based on responses to the following survey question: “Q18. Thinking back to when you first opened an RDSP, how did you first hear about this type of savings plan?” Respondents could give more than one answer; therefore, results will sum to more than 100%. The following three categories represent less than 1% of responses each: media, internet search and no response.

1.2 Mass mail-outs from CRA / ESDC were well-recognized and encouraged some individuals to open an RDSP

The most effective form of outreach appeared to be mass mail-outs from CRA / ESDC and other federal departments/agencies serving persons with disabilities:

- The most recognized formal communication among focus group participants was mail-outs from CRA or other government agencies that serve persons with disabilities.

- Some (11/37) key informants, most of whom were from financial institutions (6/11), suggested that the inclusion of information about the RDSP in communications from ESDC and CRA is an effective promotional strategy. However, a few (4/37) suggested that these mailouts could be more effective. For example, one informant said that the letters do not always reach the right targets since they only go to those who have been approved for the DTC.

- According to a few informants (3/37), the webinars and in-person sessions, including tax clinics, are also effective in conveying information about the RDSP.

Community-based organizations (CBOs) also played a role in encouraging and supporting applications to the RDSP. While promotion by CBOs was not as well-recognized as government sources of outreach, some considered it to be effective, often because CBOs are well-placed to reach and provide one-on-one application support to persons with disabilities:

- A few informants (5/37) suggested that CBOs are effective promoters of the program or are the type of organization most suited to promoting the program. A few (5/37) also said that the one-on-one support that they provide is very effective. However, informants (2/27) noted that there is no coordinated strategy among CBOs or that there is a need for more of them to promote the program (4/37).

- A few informants (4/37) suggested that promotion by CBOs is limited or non-existent. Thus, their efforts appear to be effective but not widespread.

- Focus group participants also indicated that communication from CBOs was informal and did not seem to be part of a formal outreach program.

Few plan holders, beneficiaries or stakeholders spoke about outreach and promotion by provincial and territorial partners. However, those that did found it to be informal:

- When focus group participants heard about the program through provincial agencies, it was usually through informal means, such as word of mouth from an employee.

Most plan holders, beneficiaries and stakeholders indicated that any promotion by financial institutions was primarily passive:

- When discussing promotion by financial institutions, some informants (14/37) mentioned various forms of passive promotion such as bank web pages (9/37) and a centralized call line (8/37).

1.3 Some stakeholders and partners felt that communication and outreach to their organization could be improved to help them better promote and support the delivery of the RDSP

Outreach

Most informants (5/8) from financial institutions suggested that the federal government should do more to promote the program to the public, through means such as additional promotion or advertising of the program and of the existence of independent financial advisors.

Some informants (3/7) from provincial government organizations also suggested that the federal government should do more to promote the grants and bonds.

Some informants (13/37) mentioned support provided by ESDC for CBOs such as webinars on the Program and attending in-person events. A few informants also referred to information that ESDC provides to help support CBOs with program promotion (5/37).

While most informants from CBOs (7/12) indicated that they were not aware of any tools or supports provided by ESDC, some (5/12) specified certain ESDC tools or supports that were helpful, such as:

- the package of information that is provided during tax clinics

- contacts and emails

- webinars/seminars or in-person sessions

- the website

- the availability of information in a variety of formats

Informants also had many suggestions for improving outreach to CBOs, such as:

- providing additional communication materials for use with their clients

- more information about specific topics, such as the withdrawal rules

- a dedicated contact person

- providing more training on the RDSP for their staff

Informants from CBOs discussed the accessibility of the Program website and expressed mixed views. A third of those who commented said that the format was accessible (4/12), while almost half (5/12) said that the website's accessibility could be improved.

Additionally, the majority of CBO informants (9/12) said that the content of the website was not clear enough, or that some of their clients might find it overwhelming.

Delivery

A few key informants (6/37) mentioned that ESDC provides financial institutions with training or webinars. However, a few informants (4/27) from the provinces and from CBOs suggested providing more training for financial institutions.

Additionally, half of the informants (4/8) from financial institutions suggested that ESDC could provide more information or improve communications with their organizations to facilitate their ability to open and maintain RDSPs. For example, a few informants asked if ESDC could provide them with information about clients' DTC eligibility or offer a contact that they could reach out to with questions about specific cases.

On the other hand, some informants (3/8) from financial institutions indicated that no additional tools or supports were needed, or that they were satisfied with the current tools. Financial institution informants also commented on specific tools that were useful.

Collaboration

A few informants (6/37) mentioned ESDC's or CRA's engagement with the provinces and/or territories through different activities such as participation in action groups or committees. However, a few informants (3/27) from provincial government and community-based organizations felt that there were opportunities to enhance engagement with ESDC.

While a few informants (5/37) mentioned grants to CBOs as a form of collaboration and support, a few informants (3/27) from provincial government and community-based organizations suggested adopting a more sustained and coordinated approach to supporting promotion of the Program amongst CBOs.

Some (3/12) informants from CBOs specifically suggested that they would be interested in additional collaboration with ESDC.

1.4 There is a need for more one-on-one support and improved targeting of outreach efforts to better enable some potential beneficiaries to open an RDSP

Despite the general effectiveness of certain outreach and communication efforts to promote the RDSP, there are two key barriers that either prevent certain individuals from opening an RDSP or from maximizing their contributions to the Plan, including the need for more one-on-one support after raising awareness and the limitations of communication and outreach efforts.

Need for more one-on-one support after raising awareness

Some informants (15/37),Footnote 13 including informants from all stakeholder groups and the majority of provincial/territorial government stakeholders (5/7), suggested that there is a need to provide more one-on-one support with applying for an RDSP following efforts to raise awareness.

Some informants (9/37) pointed out that the program can only benefit those who manage to open the RDSP, alluding to the barriers that some persons with disabilities or caregivers experience when accessing the Program.

Furthermore, some informants (5/37) indicated that the RDSP is easy to understand and access for some but less so for others.

A few (2/37) also indicated that marketing of the RDSP is effective, but that other elements of the Plan deter people, and that one-on-one support could help them better understand the complex elements.

Limitations of communication and outreach efforts

Some felt that the way outreach is targeted, and its timing, may be preventing certain individuals from maximizing their lifetime contributions.

Participants in several focus groupsFootnote 14 mentioned that the government should better promote the RDSP, especially early on in a person's disability, to allow more time for contributions.

Some participants felt they learned about the program too late, missing out on years of potential contributions due to lack of awareness.

A few informants (3/37) felt that the promotional strategies tend to be more appropriate for individuals with higher levels of financial literacy, hinting at the complexity of the RDSP and its rules for some people.

A few (2/37) informants felt that promotion tends to be directed at families with children rather than adults, so those who become disabled later in life might not become aware of the program in a timely manner to maximize the benefits.

1.5 From 2014 to 2021, the RDSP take-up rates increased.

According to the Program data in Table 8, take-up rates for the RDSP among all income levels increased between 2014 and 2021.

| Years | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDSP Take-up Rate (%) | 22.1 | 24.3 | 29 | 31.2 | 33.7 | 34.7 | 35.1 | 36.7 |

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC, 2025), Canada Disability Savings Program: 2023 Annual Report

The data used for Table 6 and Table 7 are drawn from the program's 2023 annual report. In the rest of the report some of the results come from quantitative analysis carried out at Statistics Canada via the linking of CDSP administrative data and personal income tax data. Among key limitations associated with the linking of both databases is the exclusion of beneficiaries under 19 years of age with no tax return. Therefore, results from this analysis should be interpreted accordingly and discrepancies may arise relative to the results presented in the program's annual report based on the entire population.

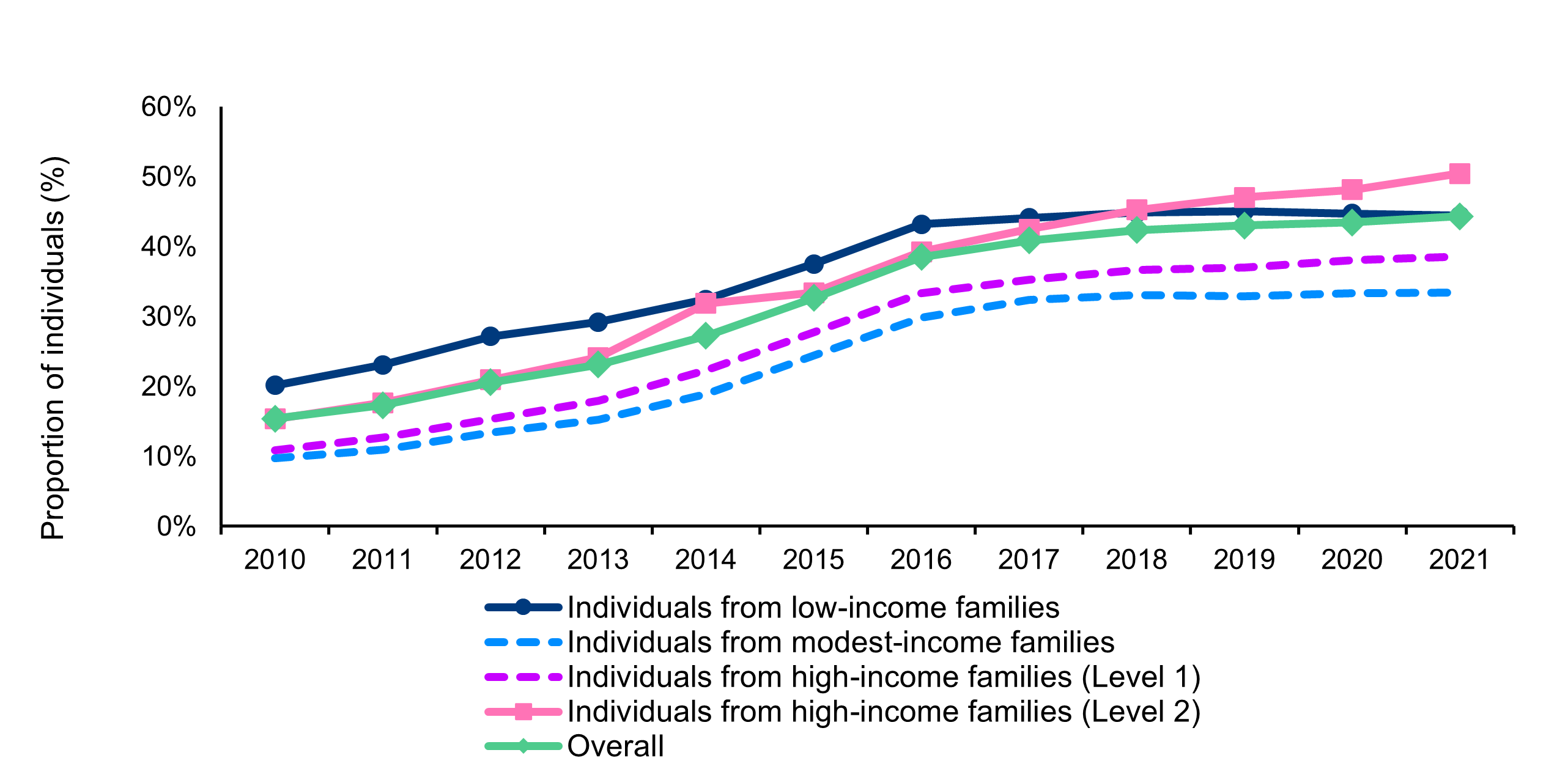

1.6 From 2010 to 2017 the take-up rates for low- and modest-income DTC-approved individuals increased steadily but started to slow around 2018.

The RDSP take-up rates in the low and modest family income groups increased steadily between 2010 and 2017 but were mostly stable between 2018 and 2021. The take-up rates for the low and modest family income groups increased from 20% and 10% in 2010 to 44% and 32% in 2017, respectively.

From 2014 to 2021, the take-up rates for DTC-approved individuals in the lowest and highest income groups were similar and exceeded those for the two intermediate income groupsFootnote 16. In 2021, for example, the take-rates for the "low family income" and "high family income level II" groups were 44.4% and 50.5% respectively, while those for the "modest family income" and "high family income level I" groups were 33.4% and 38.6%, respectivelyFootnote 17.

Appendix E provides additional information on the different income levels over time.

Figure 2: Text description

| Year | Proportion of individuals from low-income families (%) | Proportion of individuals from modest-income families (%) | Proportion of individuals from high-income families (Level 1) (%) | Proportion of individuals from high-income families (Level 2) (%) | Proportion of individuals overall (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 20% | 10% | 11% | 15% | 15% |

| 2011 | 23% | 11% | 13% | 18% | 17% |

| 2012 | 27% | 13% | 15% | 21% | 21% |

| 2013 | 29% | 15% | 18% | 24% | 23% |

| 2014 | 32% | 19% | 22% | 32% | 27% |

| 2015 | 37% | 24% | 28% | 33% | 33% |

| 2016 | 43% | 30% | 33% | 39% | 39% |

| 2017 | 44% | 32% | 35% | 42% | 41% |

| 2018 | 45% | 33% | 37% | 45% | 42% |

| 2019 | 45% | 33% | 37% | 47% | 43% |

| 2020 | 45% | 33% | 38% | 48% | 43% |

| 2021 | 44% | 33% | 39% | 50% | 44% |

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada (2025). Technical Report: Evaluation of the CDSP using linked administrative data

1.7 Certain aspects of the RDSP were identified as not well suited to the specific needs and circumstances of persons with disabilities

One aspect of the RDSP identified by focus group participants and key informants as being well-suited to the needs of persons with disabilities was the fact that the RDSP does not impact most provincial disability and income assistance benefits provided to the beneficiary, unlike other investments.

Focus group and interview participants, including RDSP account holders, beneficiaries and other stakeholders and partners, did not feel that the RDSP was well adapted to the unique circumstances or needs of persons with disabilities. They highlighted the following areas that could be improved to better meet the needs of persons with disabilities:

- penalties associated with early withdrawals

- age limit of 49 years for the grants and bonds

- perception of an age requirement of 60 before withdrawals begin

Penalties associated with early withdrawals

- The majority of interview informants (24/37) suggested that the penalties associated with early withdrawals were a source of concern for potential applicants or RDSP holders. It was often highlighted that they may be forced to withdraw the money due to factors such as unpredictable or imminent needs or expenses and/or financial strain or low income. Informants also mentioned that those who withdraw money early do so to meet urgent financial needs. In half of these cases, they withdraw money to pay for health-related expenses

- Some informants also suggested that time periods associated with withdrawals as per the AHA and the penalties are inappropriate for those with shorter or uncertain life expectancies. While beneficiaries can be eligible for exceptions from the AHA if they meet certain criteria, those who discussed this option felt that these criteria are too difficult to meet

- Some focus group participants felt that an increased flexibility of the RDSP to allow for early withdrawal, without triggering repayment, for sudden expenses related to their health or disability would better suit the unique circumstances of persons with disabilities

Age limit of 49 years for the grants and bonds

- In a few focus groups, there was confusion about why participants could no longer receive matching CDSGs for their contributions after the year in which they turn 49 years old. It was highlighted that other government programs (e.g., RRSPs) have a much higher age for ability to contribute and receive benefits (i.e., tax benefit for contributions)

- A few informants (10/37) also mentioned that the program does not benefit those who are over the age of 49 or close to that age when they sign up. Some persons with disabilities might discover their disabilities later in life and would therefore not benefit at all or as much from the grants and bonds. It was felt that the additional years of the CDSG after 49 could better help people in these situations to build savings to contribute to their financial security later in life

Perception of an age requirement of 60 before withdrawals begin

- While withdrawals from an RDSP must commence no later than the year that a beneficiary turns 60, there is a perception among multiple stakeholders, partners and beneficiaries that funds cannot be withdrawn without penalty until age 60. However,, withdrawal can generally be made without penalty 10 years after the last grant or bond is received

- Some interview informants (15/37) also suggested that the mandatory age to commence withdrawals should not be age 60, to allow for those who might want to start withdrawing from their RDSP after age 60Footnote 18

- In a few of the focus groups, both beneficiaries and their families/caregivers mentioned that the program should not have a set age of 60 for people to start withdrawing funds because people with a disability do not typically live to, or much beyond, that age

- While the Program has the Specified Disability Savings Plan, a few informants (4/37) indicated that it does not work for everyone with shorter life expectancies. For example, it may not be suitable for those whose life expectancy exceeds five years but remains uncertain, or for those experiencing administrative barriers to accessing the SDSP

| Description | Example | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Complexity of RDSP and withdrawal rules | The complexity of withdrawal rules can deter people from opening an RDSP. The fear of losing money or having to repay grants and bonds can be overwhelming and deter individuals from contributing to an RDSP | "Yeah, it's a complex plan type to say the least. It's the withdrawal rules are pretty complicated in terms of what you can receive and when you can receive it." |

| Assistance Holdback Amount | The AHA requires government contributions to remain in the RDSP for at least 10 years, which can be challenging for certain beneficiaries. | "The other thing I, but in terms of the RDSP, is if you have an individual, right, with a cognitive impairment or somebody who qualifies but there's a risk, you know, they have very poor judgment and they will not-and it's a savings venue. They might go spend that money, right? There's nothing to stop them from spending the money within that 10 years and having to pay it back, creating a debt." |

| Uncertainty of Life Expectancy and Lifetime Disability Assistance Payment formula | For individuals with uncertain life expectancies, planning for the long term can be challenging, leading to early withdrawals. | "They may not live until 83, right? They may be passing away in their 50s or their 60s. So, parents are saying, well, why am I going to put money away in this vehicle? Why am I going to manage this plan and divert my attention to investing monies in this plan if they've got to wait 10 years after the date of the last government contribution?" |

John's experience with the RDSP

John, a single man aged 20 to 24, has a permanent disability affecting his mobility and is employed part-time. He opened his RDSP in 2013 to benefit from the Bond and Grant without impacting other benefits. He faced significant challenges applying for the Disability Tax Credit (DTC) and had to reapply several times. He found the process complex due to the rules and challenges recognizing his disability. Opening his RDSP was neither easy nor difficult, but he struggled to understand the RDSP, CDSG, and CDSB rules. He also faced challenges obtaining specific information from his financial institution regarding RDSPs and felt that financial institutions were not very helpful in maximizing RDSP benefits. As of 2024, his RDSP balance is $28,000, including $20,000 in personal contributions and $8,000 from the CDSP. John expressed frustration with early withdrawal penalties and difficulty accessing funds before age 60.

Note: The case studies presented in this report are intended to illustrate individual experiences of respondents and contain inaccuracies about the program's rules and procedures. These examples provide insight into respondent's perspectives and not official policy.

2. Barriers and facilitators to opening and maintaining an RDSP

2.1 It is becoming easier to find knowledgeable financial institutions who offer the RDSP, but there are ongoing challenges for some.

Across the different lines of evidence for the evaluation, participants identified ongoing challenges with finding financial institutions who are sufficiently knowledgeable about the RDSP. This created delays in opening RDSPs for some potential account holders.

However, finding a knowledgeable institution is becoming easier than in the past. Those with more recent experiences with the RDSP tended to report fewer barriers related to finding knowledgeable staff in financial institutions than those with experience in the earlier years of the Program.

When discussing barriers to opening or maintaining RDSPs, the majority of informants (20/37) identified barriers associated with financial institutions.

Some interview informants (14/37) and focus group participants suggested that staff from financial institutions lack sufficient knowledge of the RDSP, although many of these informants did not differentiate between frontline staff or staff who work in centralized RDSP teams within banks.

In almost all focus groups, participants felt that it was difficult to find individuals within their financial institutions who were knowledgeable about the RDSP. This left a lot of unanswered questions and confusion about the program.

In a few groups, participants mentioned having to work with a specialist in their institution. This specialist was often located in another city or province which made opening the RDSP difficult, because of issues with scheduling and communication.

Focus group participants who opened an RDSP early in the Program lifecycle encountered significant barriers such as finding a financial institution that offered the program, finding people within these institutions who were knowledgeable about the program, or finding information about the program more generally. However, those who opened an RDSP more recently reported experiencing fewer of these barriers.

In almost all focus groups, participants believed that people within their institutions have become more knowledgeable about the program. At the same time, participants in some groups say that they still do their own research and often know more about the program than those they interact with at their financial institutions. Participants in some groups felt that there could be more training for financial institutions in how to properly administer it.

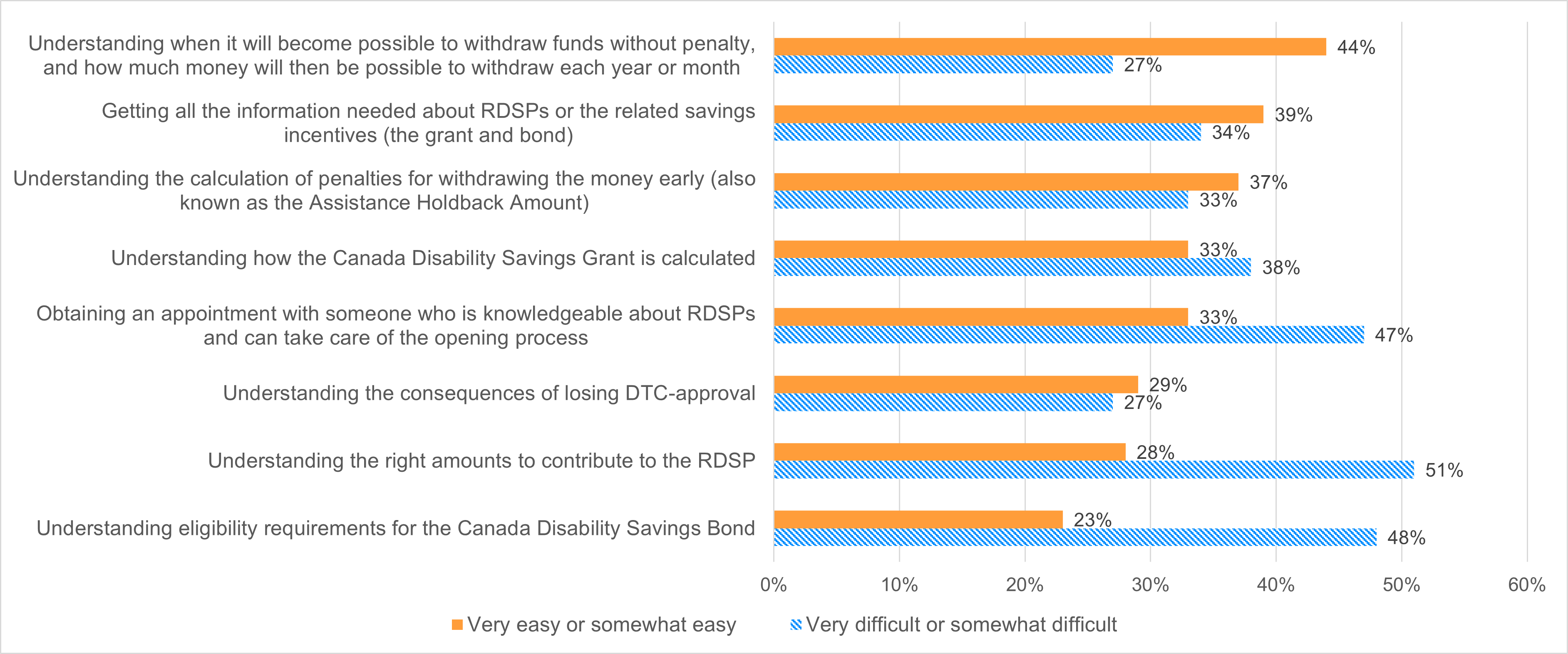

When working with their financial institution or advisor to open an RDSP, survey respondents reported the greatest ease with obtaining an appointment with someone who is knowledgeable about RDSPs and understanding the right amounts to contribute to the RDSP, with 22% of respondents saying each of these was "very easy." This was followed by understanding the eligibility requirements for the Canada Disability Savings Bond, which 20% found "very easy" and 28% found "somewhat easy."

Respondents had the least ease in understanding when it will become possible to withdraw funds without penalty from some or all of the CBSGs and/or CDSBs received, and how much money could then be withdrawn annually or monthly. Only 10% of respondents said this was "very easy" and only 17% said this was "somewhat easy."

Therefore, survey respondents appeared to find financial institutions more knowledgeable about topics related to opening and contributing to the account, and less knowledgeable about specific rules and restrictions after the account is opened.

Figure 3: Text description

| Response option | Very easy or somewhat easy | Very difficult or somewhat difficult |

|---|---|---|

| Understanding when it will become possible to withdraw funds without penalty and how much money will then be possible to withdraw each year or month | 44% | 27% |

| Getting all the information needed about RDSPs or the related savings incentives (the grant and bond) | 39% | 34% |

| Understanding the calculation of penalties for withdrawing the money early (also known as the Assistance Holdback Amount) | 37% | 33% |

| Understanding how the Canada Disability Savings Grant is calculated | 33% | 38% |

| Obtaining an appointment with someone who is knowledgeable about RDSPs and can take care of the opening process | 33% | 47% |

| Understanding the consequences of losing DTC approval | 29% | 27% |

| Understanding the right amounts to contribute to the RDSP | 28% | 51% |

| Understanding eligibility requirements for the Canada Disability Savings Bond | 23% | 48% |

- Source: PRA (2024). Survey for the Evaluation of the CDSP, Conducted for ESDC’s Evaluation Directorate. Unpublished technical report

- Note: The information in this figure is from responses to survey questions 29 to 36: “The following questions are about when you met with your financial institution or with an independent financial advisor to set up an RDSP for the first time. Please rate how easy or difficult the following steps may have been in setting up the RDSP.”

2.2 The complexity of the application process and the level of effort required to complete it were the most common barriers for potential beneficiaries and plan holders

Barriers related to the complexity of the application process and the effort it requires were frequently identified by multiple sources. These barriers can be particularly challenging for those who have disabilities affecting mental functions or who are struggling with day-to-day expenses.

Multiple studies outside of this evaluation have found that the RDSP process is complicated and has discouraged people from opening an RDSP. For example, applicants have reported the DTCFootnote 19 and RDSP processes are both lengthy and complex (Abrams, 2017Footnote 20; Moss, 2012Footnote 21). In addition, recent data from the 2020 Survey on Savings for Persons with Disabilities reported that 15% of respondents described the process as being too complicated and opted to not open an RDSP, citing difficulties in completing tax forms and/or visiting financial institutions to open the plan (Statistics Canada 2022cFootnote 22).

Most interview informants (23/37) agreed that the complexity of the application process and the effort required to apply were barriers to opening or maintaining an RDSP. Some (16/37) discussed specific challenges related to families or individuals who are so focused on managing day-to-day requirements that they do not have the time or energy to consider the RDSP or follow through with the application process.

The 2024 Fifth Report of the Disability Advisory CommitteeFootnote 23 reported the following:

- navigating the application process remains a significant challenge for many applicants. A complete application requires Part A (tax filer information completed by applicant) and Part B (eligibility information completed by medical practitioner) of the T2201 form for the DTC

- one quarter of persons with disabilities who are likely eligible submit a completed DTC application. Most completed applications (96.6%) are approved (fewer than 4% are either rejected or under appeal). This suggests that more support and accessibility in the process is needed for applicants to successfully complete the process

Sarah's Experience Opening an RDSP

Sarah, a single woman aged 25 to 34, has a temporary disability that affects her mobility and independence. She is currently unemployed but actively looking for work. She opened her RDSP in 2019 to take advantage of both the Bond and the Grant and to accumulate assets without impacting eligibility for other benefits. She applied for the Disability Tax Credit (DTC) but faced significant challenges and found it very difficult. She had to reapply multiple times due to challenges having her disability recognized. Then, in opening her RDSP she found the process itself relatively easy but finds it difficult to understand the different parameters and rules of the RDSP and the CDSG and CDSB. As of 2024, Sarah has an RDSP balance of $6,000, funded entirely by the CDSB, as she has not made any personal contributions meaning she has not received the CDSG.

Note: The case studies presented in this report are intended to illustrate individual experiences of respondents and contain inaccuracies about the program's rules and procedures. These examples provide insight into respondent's perspectives and are not official policy.

2.3 Some beneficiaries and account holders found the process to obtain the DTC difficult and time-consuming to navigate.

The Disability Tax Credit (DTC) application process is easier for some than for othersFootnote 24. Since DTC approval is required to open an RDSP, challenges in understanding and applying for the tax credit can be a barrier to opening an RDSP.

Survey respondents were split on the difficulty of the DTC process. Some (37%) found the application forms and related documents somewhat or very easy to understand and a similar proportion (34%) found them somewhat or very difficult to understand.

Overall, focus group participants did not have many concerns or issues with understanding or applying for the DTC. In addition, family members who hold accounts on behalf of beneficiaries expressed fewer concerns than beneficiaries themselves indicating that the DTC process tends to be more difficult for beneficiaries trying to navigate it themselves.

| Responses | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Bureaucratic/too many forms | 23 | 31% |

| Told disability was not severe enough to qualify/had to apply multiple times | 23 | 31% |

| Delays in getting approval | 15 | 20% |

| Had to get additional information from physician/missing information | 12 | 16% |

| DTC is not permanent/need to reapply | 9 | 12% |

| Costs associated with applying | 7 | 9% |

| Difficulties communicating with CRA | 5 | 7% |

| Need assistance from others to complete DTC application | 5 | 7% |

| Had to get information from multiple healthcare workers | 4 | 5% |

| Doctors unsure how to complete forms | 2 | 3% |

| Other | 2 | 3% |

| No response | 1 | 1% |

- Source: PRA (2024). Survey for the Evaluation of the CDSP, Conducted for ESDC’s Evaluation Directorate. Unpublished technical report

- Note: The information in the table is based on responses to survey question 25: “Please describe the difficulties you experienced getting approval for the DTC from the CRA.” (Base : Those who rated getting DTC approval from the CRA difficult)

2.4 There was a general lack of clarity related to the Assistance Holdback Amount

There is a lack of clarity related to the Assistance Holdback Amount (AHA).

Overall, it was apparent in all focus groups that participants did not understand the AHA well and perceive the repayment obligation as a penalty.

Some key informants (19/37) also felt that the program parameters for the Assistance Holdback Amount are not easy to understand for applicants and beneficiaries.

There were many different points of view in the focus groups concerning the timelines for when a participant could start withdrawing funds, with a particular lack of clarity around the 10-year rule for grant or bond withdrawals, and the age at which it becomes possible to withdraw without penalty. This demonstrated a lack of common understanding of the AHA, timelines and their purpose.

In all focus groups, participants spoke about the penalties associated with withdrawing early, although there was very little specific reference to exactly what the penalties would be. This demonstrated a concern amongst beneficiaries and their families/caregivers about the consequences of withdrawing funds early.

Survey results similarly suggested that understanding the parameters of the AHA was one of the primary areas of concern among respondents, all of whom were RDSP holders. Areas related to penalties or withdrawing funds were among the top areas of difficulty respondents had when first opening their RDSP.

Emily's Experience Opening an RDSP

Emily, a divorced woman aged 35 to 44 with a permanent mobility disability, is employed part-time. Her legal parent opened her RDSP in 2022 to leverage the Canada Disability Savings Grant (CDSG) alongside her contributions for medium-term financial needs. Emily found the DTC application process straightforward and reported no major difficulties. Managing her RDSP was relatively easy, though she faced challenges understanding the RDSP, CDSG, and CDSB rules. By 2024, her RDSP balance reached $4,500, including $1,500 in personal contributions, benefiting from the CDSG. Despite the generous grant, Emily struggled with withdrawal penalties and eligibility requirements, and her financial institution was not very helpful. Overall, she found managing her RDSP easier than John, likely due to third-party involvement in opening the account and straightforward DTC approval. Emily emphasized that the RDSP helps maintain her future quality of life, despite some rule comprehension challenges.

Note: The case studies presented in this report are intended to illustrate individual experiences of respondents and contain inaccuracies about the program's rules and procedures. These examples provide insight into respondent's perspectives and not official policy.

3. The role of the CDSG and the CDSB in motivating savings

3.1 The CDSG appears to be a stronger motivator than the CDSB for eligible beneficiaries and plan holders to open an RDSP

Survey respondents and focus group participants identified the CDSG and CDSB as strong motivators to open an RDSP:

- Access to the CDSG and CDSB was the second most selected (50%) reason for opening an RDSP amongst survey respondents

- However, the CDSG, which requires a contribution, seems to be a much stronger motivator as 24% of survey respondents selected the CDSG as a primary motivator compared to only 4% who selected the CDSB as a primary motivator

- Participants in all focus groups indicated that the grant and bond provide strong motivation to open an account and that the CDSG was a significant reason for opening and contributing to an RDSP

- In almost all focus groups participants said that they try to contribute as much as possible to the RDSP when they have additional money. However, in some groups participants said that putting money into their RDSP is a lower priority relative to covering their day-to-day expenses

- Participants primarily spoke about the value of the government matching contributions, and how those matched components add significantly to the value of their RDSP

- In some groups, there are others who mentioned that the bond is the primary benefit. These participants tended to be individuals who put less (or even no) money into their RDSP

The findings from the administrative data analysis also suggest that the Canada Disability Savings Bond (CDSB) has a positive impact on opening an RDSP account for those who have incomes close to the maximum allowable net income to receive the CDSBFootnote 25. In 2018, for example, individuals with net family income close to but lower than $46,605 and who were eligible to receive a portion of the bonds were more likely to have opened an RDSP account by 6.7 percentage points compared to similar non-eligible individuals with net family income just above $46,605 (consult Appendix H for more information). However, around the net-family income threshold of $93,208 (where the matching rate of the Canada Disability Savings Grant is reduced), there was no statistically significant difference in the probability of opening an account between those who were eligible for the higher matching rate and those eligible for the lower contribution rate.

The CDSG and CDSB were not the only significant motivators for focus group participants to open and contribute to an RDSP:

- Focus group participants also mentioned being motivated to open an RDSP because of the government grant and bond

- Participants also felt that it offered some assurance that their child would have sufficient income to support themselves in the future when they may no longer be able to support them. This helps to ease their anxiety and concern about the future well-being of their child

Why Marc chose to open an RDSP

Marc is a 41-year-old male living with a permanent disability who opened his own Registered Disability Savings Plan (RDSP) sometime between 2016 and 2019. Holding an undergraduate university degree, he is currently looking for a job and has an annual household income of less than $35,000. The total amount accumulated in his RDSP is approximately $30,000. Part of this amount includes his own personal contributions, as well as a mix of grants and bonds received from CDSP. In addition to the RDSP, Marc has other savings accounts totaling $1,256 but he chose to open an RDSP to maximize the benefits of both the Canada Disability Savings Bond (CDSB) and the Canada Disability Savings Grant (CDSG), increase his savings, and ensure his long-term financial security while preserving eligibility for other social programs.

Note: The case studies presented in this report are intended to illustrate individual experiences of respondents and contain inaccuracies about the program's rules and procedures. These examples, taken from survey responses, provide insight into respondents' perspectives and not official policy.

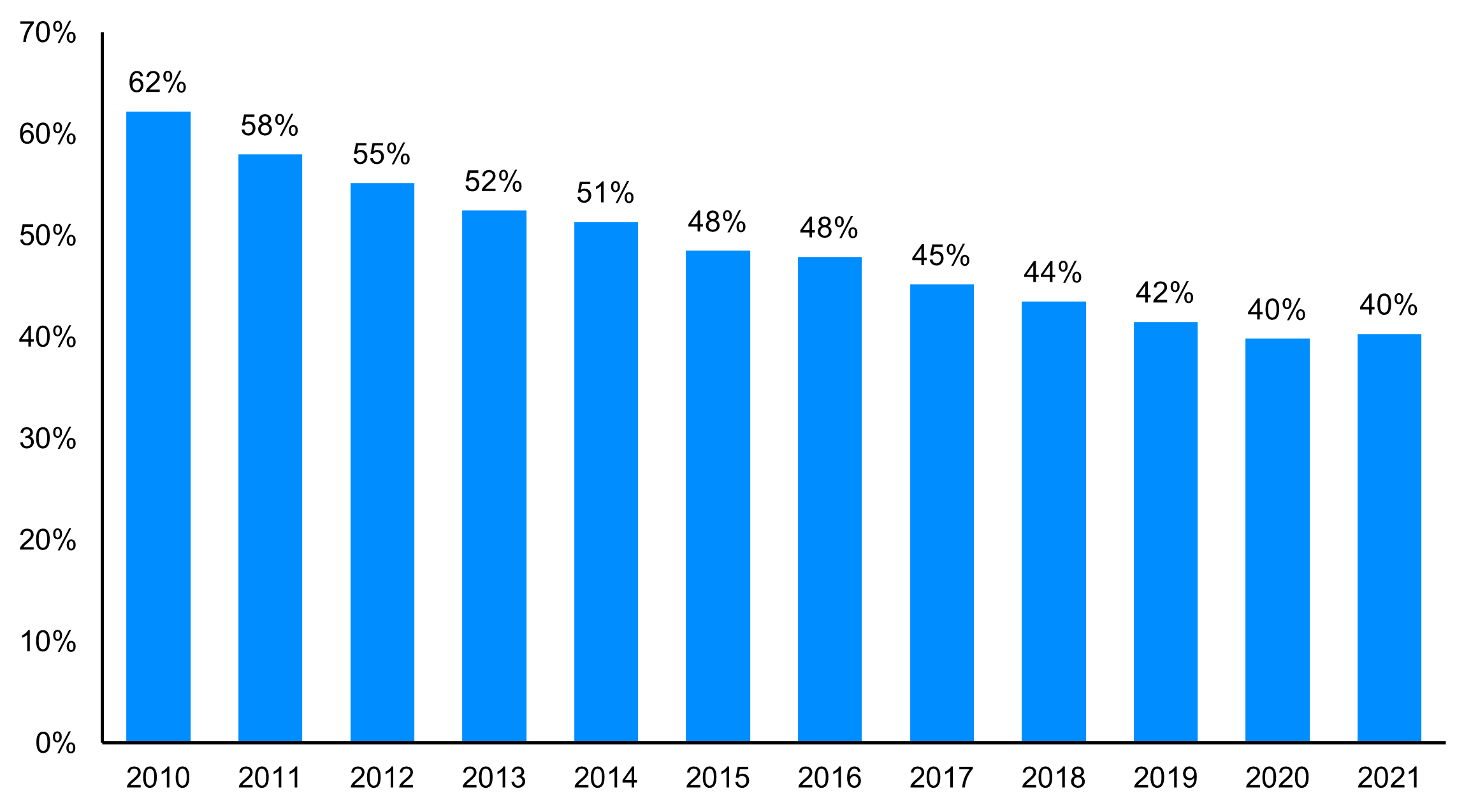

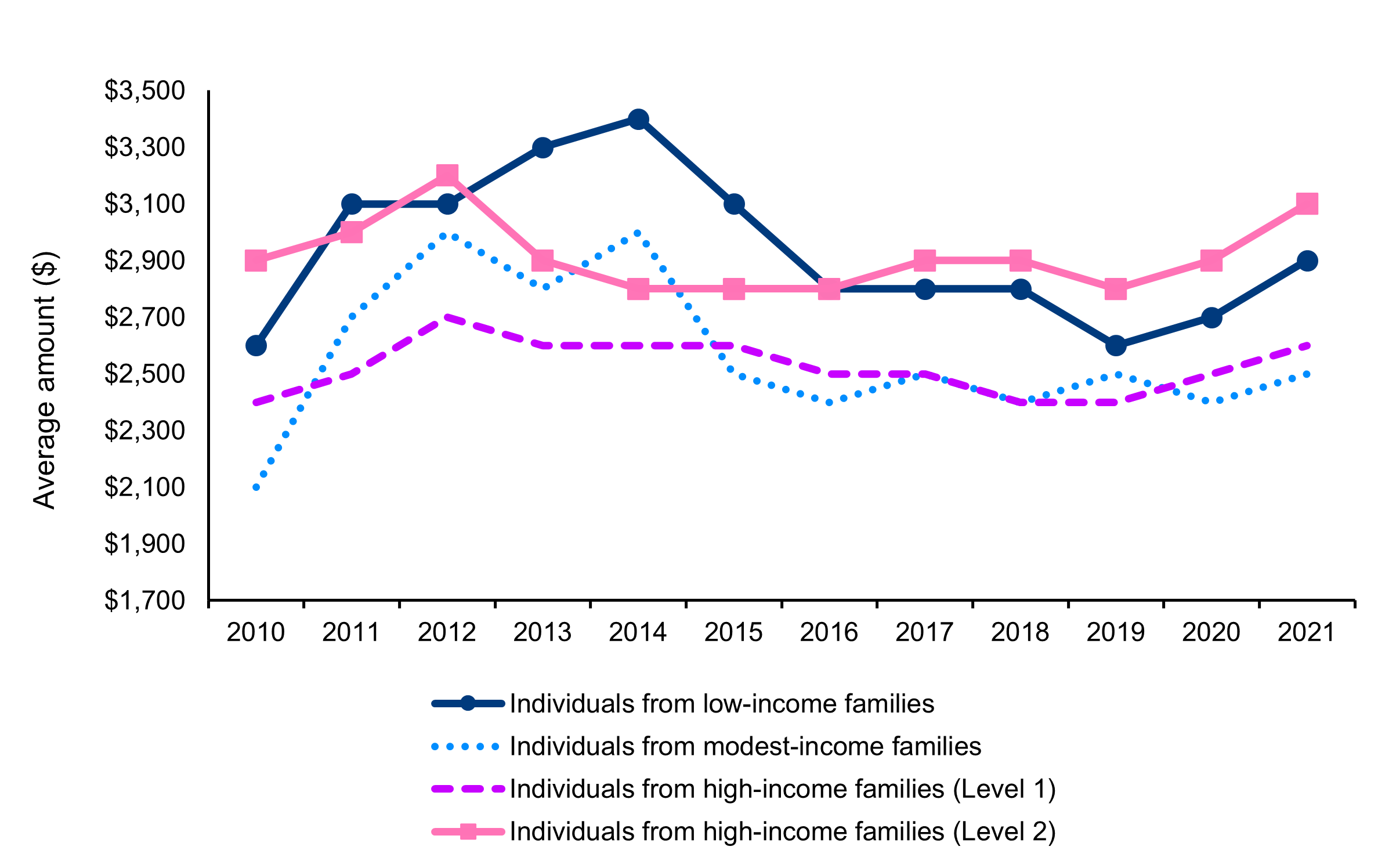

3.2 The proportion of RDSP beneficiaries who contributed decreased over time, but the amount they contributed has remained relatively stable over time and across income categories

The proportion of RDSPs in which a private contribution was made decreased by 22% over the evaluation period, from 62% in 2010 to 40% in 2021.

The average amount of contribution made remained relatively stable amongst all income levels over the evaluation period. Contribution amounts were higher for those with Low Income and High Income Level II.

Figure 4: Text description

| Year | Proportion of RDSP beneficiaries who contributed to their accounts |

|---|---|

| 2010 | 62% |

| 2011 | 58% |

| 2012 | 55% |

| 2013 | 52% |

| 2014 | 51% |

| 2015 | 48% |

| 2016 | 48% |

| 2017 | 45% |

| 2018 | 44% |

| 2019 | 42% |

| 2020 | 40% |

| 2021 | 40% |

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada (2025). Technical Report: Evaluation of the CDSP using linked administrative data

- Note: The calculations only considered RDSP beneficiaries and DTC-approved individuals who filed taxes individually and did not include a large proportion of individuals under 19 years. Therefore, results from this analysis should be interpreted accordingly and discrepancies may arise relative to the results presented in the program’s annual report based on the entire population.

Overall, more savings were made in RDSPs of High Income Level II and Low Income beneficiaries than those in other two income categories throughout the evaluation period.

Figure 5: Text description

| Year | Individuals from low-income families | Individuals from modest-income families | Individuals from high-income families (Level 1) | Individuals from high-income families (Level 2) | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | $2,600 | $2,100 | $2,400 | $2,900 | $2,400 |

| 2011 | $3,100 | $2,700 | $2,500 | $3,000 | $2,700 |

| 2012 | $3,100 | $3,000 | $2,700 | $3,200 | $2,800 |

| 2013 | $3,300 | $2,800 | $2,600 | $2,900 | $2,800 |

| 2014 | $3,400 | $3,000 | $2,600 | $2,800 | $2,900 |

| 2015 | $3,100 | $2,500 | $2,600 | $2,800 | $2,700 |

| 2016 | $2,800 | $2,400 | $2,500 | $2,800 | $2,600 |

| 2017 | $2,800 | $2,500 | $2,500 | $2,900 | $2,600 |

| 2018 | $2,800 | $2,400 | $2,400 | $2,900 | $2,600 |

| 2019 | $2,600 | $2,500 | $2,400 | $2,800 | $2,500 |

| 2020 | $2,700 | $2,400 | $2,500 | $2,900 | $2,600 |

| 2021 | $2,900 | $2,500 | $2,600 | $3,100 | $2,800 |

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada (2025). Technical Report: Evaluation of the CDSP using linked administrative data

- Note: The calculation only considered RDSP beneficiaries and DTC-approved individuals who filed taxes individually and did not include a large proportion of individuals under 19 years. Therefore, results from this analysis should be interpreted accordingly and discrepancies may arise relative to the results presented in the program’s annual report based on the entire population.

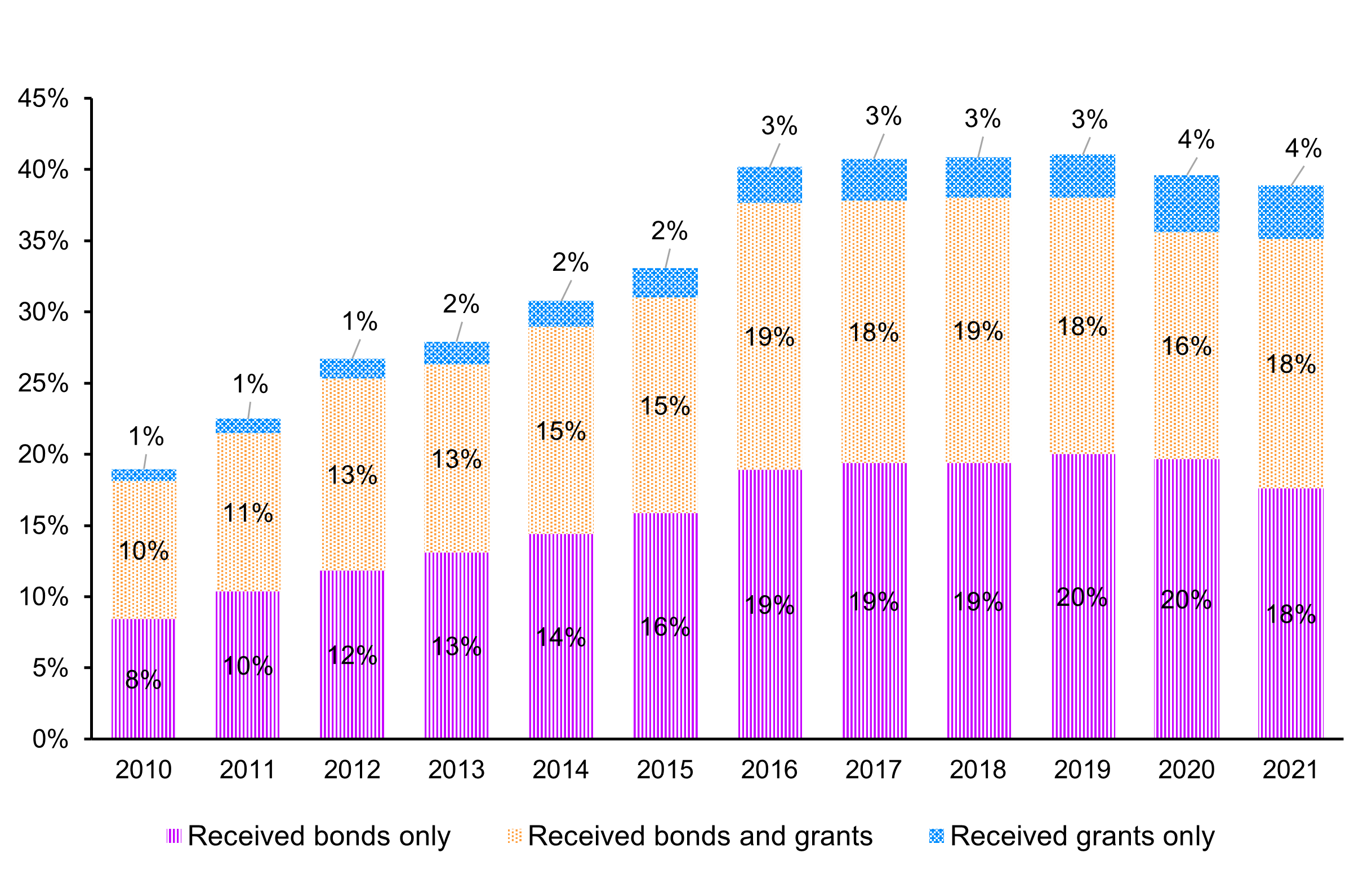

3.3 The proportion of DTC-approved individuals from low- or modest- income families receiving grants and/or bonds remained relatively stable over the evaluation period with most RDSP beneficiaries receiving bonds.

The proportion of DTC approved individuals from low family income receiving grants or bonds between 2010 and 2016 remained stable.

Figure 6: Text description

| Receipt of bonds and/or grants | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Received bonds only | 8% | 10% | 12% | 13% | 14% | 16% | 19% | 19% | 19% | 20% | 20% | 18% |

| Received bonds and grants | 10% | 11% | 13% | 13% | 15% | 15% | 19% | 18% | 19% | 18% | 16% | 18% |

| Received grants only | 1% | 1% | 1% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 4% | 4% |

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada (2025). Technical Report: Evaluation of the CDSP using linked administrative data (draft)

- Note: Calculation only considered RDSP beneficiaries and DTC-approved individuals who filed taxes individually and did not include a large proportion of individuals under 19 years. Therefore, results from this analysis should be interpreted accordingly and discrepancies may arise relative to the results presented in the program’s annual report based on the entire population.

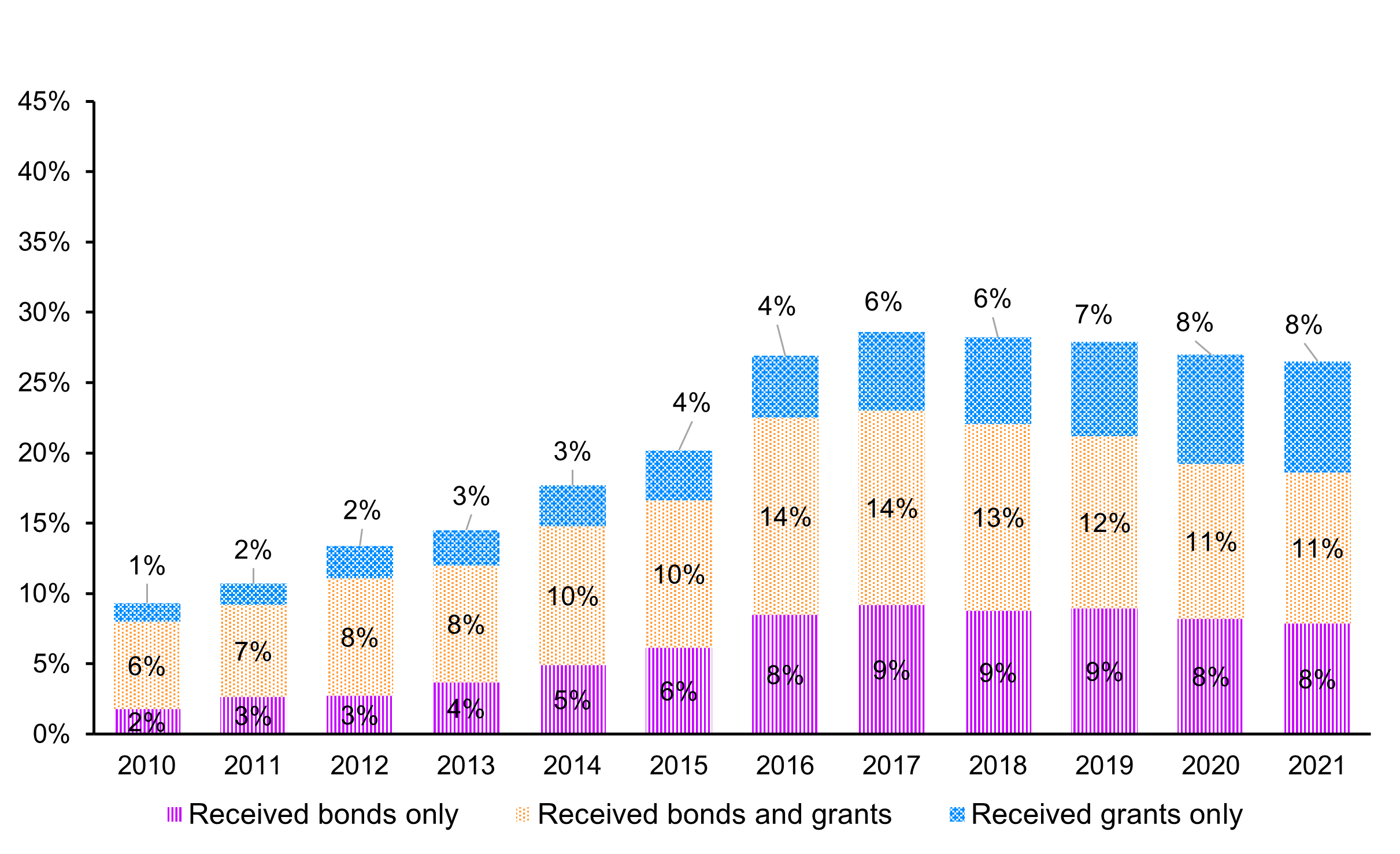

The proportion of DTC approved individuals from modest family income receiving grants or bonds increased between 2010 and 2016, then remained stable from 2017.

Figure 7: Text description

| Year | Received bonds only | Received bonds and grants | Received grants only |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2% | 6% | 1% |

| 2011 | 3% | 7% | 2% |

| 2012 | 3% | 8% | 2% |

| 2013 | 4% | 8% | 3% |

| 2014 | 5% | 10% | 3% |

| 2015 | 6% | 10% | 4% |

| 2016 | 8% | 14% | 4% |

| 2017 | 9% | 14% | 6% |

| 2018 | 9% | 13% | 6% |

| 2019 | 9% | 12% | 7% |

| 2020 | 8% | 11% | 8% |

| 2021 | 8% | 11% | 8% |

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada (2025). Technical Report: Evaluation of the CDSP using linked administrative data (draft)

- Note: calculation only considered RDSP beneficiaries and DTC-approved individuals who filed taxes individually and did not include a large proportion of individuals under 19 years. Therefore, results from this analysis should be interpreted accordingly and discrepancies may arise relative to the results presented in the program’s annual report based on the entire population.

3.4 Some plan holders or beneficiaries are saving money outside of an RDSP and it is often related to a perception that other accounts were better suited to the realities of persons with disabilities

The extent to which plan holders choose to save outside of an RDSP is unclear.

Some interviewees (5/37) felt that there were no better savings vehicles for persons with disabilities. The majority of these informants (3/5) pointed out that the benefit associated with the RDSP is more generous than the benefits offered through other savings options.

However, others felt that different account types were better suited to the needs of persons with disabilities:

- Some interviewees (15/37) suggested that other account types might be better adapted to the needs of persons with disabilities than RDSPs. Most of these informants (12/15) said that account types with greater flexibility to withdraw money without penalties might be more appropriate for some persons with disabilities

- In addition, a few informants (8/37) suggested that accounts that are easier to open or manage are appealing to persons with disabilities

Survey respondents who have savings in other types of accounts shared the perception that these options may be better suited to the realities of persons with disabilities. The most common reason for an alternative savings plan or account was for funds to be accessible more easily and without penalty in case of emergency (46%).

| Response | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| For funds to be accessible more easily and without penalty in case of emergency | 201 | 46% |

| To accumulate additional retirement savings | 148 | 34% |

| To accumulate money for major purchases | 114 | 26% |

| To diversify investments | 98 | 23% |

| Already contributed the maximum allowable to the RDSP(s) | 94 | 22% |

| For tax purposes | 85 | 20% |

| It was recommended by a financial professional | 85 | 20% |

| To obtain a higher interest rate/return on investments | 77 | 18% |

| For day-to-day banking/finances | 19 | 4% |

| Had before the RDSP | 12 | 3% |

| To avoid penalties from RDSP withdrawals | 3 | 1% |

- Source: PRA (2024). Survey for the Evaluation of the CDSP, Conducted for ESDC’s Evaluation Directorate. Unpublished technical report

- Note: The information is based on responses to the following survey question: “Why did you choose to open other types of savings plans or account, in addition to the RDSP? (Base: Those who have at least one other savings plan or account but do not currently contribute to it).” Of the informants who mentioned complementary or alternative investment or savings vehicles used by those who are eligible for RDSPs, most (15/19) mentioned TFSAs. Informants also mentioned the following other savings vehicles: RRSPs (5/27), RESPs (4/37), trusts (4/37), savings accounts (3/37), non-registered plans (2/37), segregated funds (1/37).

Survey responses provide a sense of the most common alternative investment vehicles used by plan holders and beneficiariesFootnote 29.

The most common types of other plans/accounts that survey respondents actively contribute to outside of their RDSP were:

- Registered savings account at a financial institution (37%)

- Tax Free Savings Accounts (32%)

- Registered Retirement Savings Plan (23%)

| Type of savings plan or account | Have and currently contribute to (Number) | Have and currently contribute to (Percentage) | Have and currently withdraw from (Number) | Have and currently withdraw from (Percentage) | Have but do not currently contribute to or withdraw from (Number) | Have but not currently contribute to or withdraw from (Percentage) | Do not have (Number) | Do not have (Percentage) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular savings account at a financial institution | 2,801 | 37% | 1,434 | 19% | 1,222 | 16% | 1,758 | 23% |

| Tax-Free Savings Account (TFSA) | 2,439 | 32% | 349 | 5% | 1,240 | 17% | 3,249 | 43% |

| Registered Retirement Savings Plan (RRSP) | 1,702 | 23% | 216 | 3% | 1,271 | 17% | 4,096 | 55% |

| Employer-sponsored pension plan | 1,351 | 18% | 323 | 4% | 435 | 6% | 5,120 | 68% |

| Mutual funds | 936 | 12% | 122 | 2% | 551 | 7% | 5,508 | 73% |

| Guaranteed Investment Certificates (GIC)s | 746 | 10% | 89 | 1% | 588 | 8% | 5,725 | 76% |

| Registered Education Savings Plan (RESP) | 526 | 7% | 205 | 3% | 331 | 4% | 6,267 | 83% |

| Tax-Free First Home Savings Account (FHSA) | 186 | 3% | 20 | <1% | 83 | 1% | 7,018 | 93% |

| Other type of trust fund | 53 | 1% | 51 | 1% | 96 | 1% | 6,983 | 93% |

| Henson Trust | 44 | 1% | 29 | <1% | 327 | 4% | 6,751 | 90% |

| Registered Retirement Income Fund (RRIF) | 40 | 1% | 151 | 2% | 95 | 1% | 6,954 | 92% |

| Other | 375 | 5% | 118 | 2% | 151 | 2% | 6,878 | 91% |

- Source: PRA (2024). Survey for the Evaluation of the CDSP, Conducted for ESDC’s Evaluation Directorate. Unpublished technical report

- Note: The information in the table is based on responses to the following survey question: “Q41. Which of the following other types of savings plans or accounts do you currently have, contribute to, or benefit from, if any? Currently refers to the past 12 months.” Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

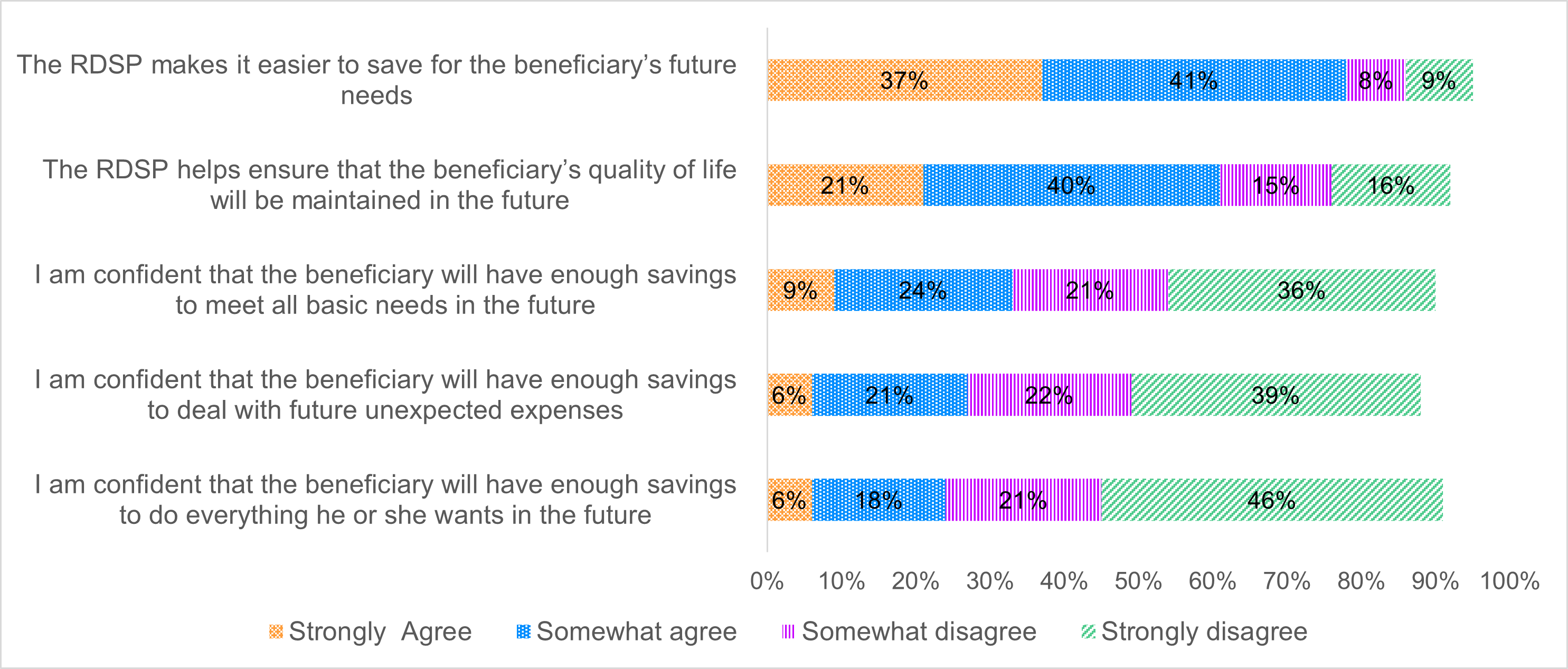

4. Early impacts of the RDSP on quality of life or well-being

4.1 Beneficiaries, plan holders and other stakeholders believe that the program has the potential to help improve the quality of life and/or well-being of beneficiaries and/or plan holders in the future

There was a shared sense amongst interviewees and focus group participants that it is still too early to assess impacts to the quality of life of beneficiaries and/or plan holders as there are few beneficiaries who have begun receiving Lifetime Disability Savings Payments.

Most key informants (32/37) felt positive about the RDSP's potential impact on beneficiaries' future financial security and ability to maintain their current quality of lifeFootnote 30 in the future but said that this depends on various factors that might limit their ability to either access or to take full advantage of the program.