Evaluation of the Occupational Health and Safety Program

On this page

- Highlights

- Management resonse

- Program and evaluation overview

- Context

- Key findings

- Recommendations

- Annexes

- Annex A - Definitions

- Annex B - Program logic model (2017)

- Annex C - Program background

- Annex D - Evaluation questions

- Annex E - Lines of evidence: descriptions and limitations

- Annex F - Employee rights and specific survey questions

- Annex G - Federal jurisdiction sectors under Part II of the Canada Labour Code

- Annex H - Provincial, territorial and federal average injury rates

- Annex I - References

Alternate formats

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

Highlights

This evaluation examined the performance of the Occupational Health and Safety Program, within the Labour Program of Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC). It complies with the 2016 Treasury Board policy on results, and covers the period from fiscal year 2011 to 2012 and up to fiscal year 2015 to 2016. A fiscal year runs from April 1 to March 31.

Definitions for terms marked with an asterisk (*) can be found in Annex A.

Key findings and recommendations

This evaluation found that program activities have contributed to a safe and healthy workplace. For instance, the majority of surveyed federally regulated employers (91%) and employees (71%) found that Occupational Health and Safety regulations adequately ensured a safe and healthy workplace. Key highlights of this evaluation are as follows:

Modernization and awareness

There are emerging challenges in occupational health and safety, particularly in the areas of mental health and non-standard* employment, leading to a rise in vulnerable* workers.

Recommendation 1: Increase awareness of occupational health and safety to address emerging challenges, prevent future issues and risks, and further support vulnerable workers.

Proactive activities

As the Disabling injury incidence rate* increased by 7% over the evaluation period, proactive inspections dropped by 45% and the number of inspection officers declined.

Recommendation 2: Explore ways to increase proactive activities, including strategically targeted inspections in high risk sectors, in order to detect violations and prevent potential injuries and/or illnesses.

Reactive activities

While all surveyed employers are satisfied with the results stemming from the internal complaints resolution process, employees are considerably less satisfied (60%) with the overall process, including the timeliness of services (55%).

Recommendation 3: Identify and address issues that may have hindered the effectiveness of the internal complaints resolution process, and develop service standards to address violations in a timely and effective manner.

Performance measurement practices

The performance measurement practices in place do not fully support the monitoring and measuring of expected outcomes, such as compliance with the Code and incidence rates in high-risk sectors.

Recommendation 4: To support monitoring and reporting activities, the program could improve performance measurement practices to capture reliable information with respect to key metrics, such as incidence rates, compliance levels, and the severity of violations.

Management response

Modernization and awareness

Recommendation 1

Increase awareness of occupational health and safety to address emerging challenges, prevent future issues and risks, and further support vulnerable workers.

Response:

The Labour Program agrees with the recommendation to modernize and increase awareness of occupational health and safety regulations.

In response to the recommendation of the 2016 Audit of the OHS Program to develop a strategic framework for data gathering and analysis to improve program monitoring and reporting, management created the Business Intelligence Unit and associated Business Intelligence Strategic Framework to improve data accessibility and data integrity.

Management will continue to engage with stakeholders, including employee and employer representatives, and federal, provincial and territorial jurisdictions by using established platforms such as the Occupational Health and Safety Advisory Committee (OHSAC) and the Canadian Association of Administrators of Labour Legislation - Occupational Health and Safety (CAALL-OHS).

Action 1:

The Labour Program will use various platforms (internal and external) to consult, monitor, gather information and increase awareness within the Labour Program of emerging occupational health and safety issues in the workplace (ongoing).

Action 2:

Establish a Strategic Stakeholder Relations Unit within the OHS Program to monitor key emerging issues (ongoing).

Action 3:

The Labour Program will create a framework to consolidate the activities in which the OHS Program participates (March 2019):

- having technical experts attend international conferences in order to remain up to date with international issues and practices

- participating in an artificial intelligence pilot project, and

- OHS regulatory harmonization

Action 4:

The Labour Program will develop a proposal to establish a prevention approach to occupational health and safety issues (November 2019).

This proposal will determine the best approach to anticipating the occupational health and safety risks that exist specifically for vulnerable workers.

Proactive activities

Recommendation 2

Explore ways to increase proactive activities, including strategically targeted inspections in high risk sectors, in order to detect violations and prevent potential injuries and/or illnesses.

Response:

The Labour Program agrees with the recommendation to increase proactive activities, including strategically targeted inspections in high-risk sectors.

Action 1:

The Program is conducting research on prevention to determine ways to improve its proactive activities, particularly in high-risk sectors such as transport (March 2020).

Action 2:

The Program is conducting a pilot project using data from workers compensation boards in Saskatchewan to gather information on where proactive activities should be targeted (Start date: January 2019).

Action 3:

A pilot project is underway in the Quebec and the Central regions to test the re-allocation of inspections using a new targeting tool to address prevention (March 2020).

Reactive activities

Recommendation 3

Identify and address issues that may have hindered the effectiveness of the internal complaint resolution process, and develop service standards to address violations in a timely and effective manner.

Response:

The Labour Program agrees with the recommendation to identify and address issues with the Internal Complaint Resolution Process and develop service standards.

In response to the 2016 Audit of the OHS Program recommendation to develop a comprehensive service delivery strategy to formalize regular activities and interactions with clients and stakeholders, management developed Client Service Delivery Standards and a Client/Stakeholder Engagement Strategy.

Action 1:

The Labour program will produce a report examining the reasons as to why there is sometimes failure to achieve consensus within the workplace on refusal to work cases by consulting with stakeholders (May 2019).

Action 2:

The Program will conduct an analysis on ways in which health and safety officers (HSO) can better help workplace parties throughout the course of the internal complaint resolution process (September 2019). The Program will then develop more tools and guidance documents for use by HSOs.

Action 3:

The Labour Program developed and published service standardsFootnote 1 associated with specific processes in November 2018, in order to reduce employee dissatisfaction with the length of time in which their complaint was resolved.

The outcome and efficiency resulting from the implementation of the service standards is expected to be determined further to the strategic operational planning and yearly cycle reviews. Conducting systematic follow-ups and reviews of service standards and their outcomes will help identify areas in which improvements or other service standards can be implemented, in order to better respond to issues or concerns of clients and further reduce employee dissatisfaction (ongoing).

Performance measurement practices

Recommendation 4

To support monitoring and reporting activities, the program could improve performance measurement practices to capture reliable information with respect to key metrics, such as incidence rates, compliance levels, and the severity of violations.

Response:

The Labour Program agrees with the recommendation to improve performance measurement practices.

In response to the 2016 Audit of the OHS Program recommendation to develop a program-wide quality control process, including indicators to measure the on-going effectiveness of key OHS processes, management developed a quality control framework that is supported by an overarching OHS performance measurement framework.

Over the past 2 years, the Program has worked to examine processes and expected outcomes and, as part of TBS’ annual Performance Information Profile, develop a number of performance indicators by which to measure the effectiveness of its activities, as well as areas where improvements could be made.

Action 1:

The Program will continue to update the annual Performance Information Profile and track changes in incidence and compliance rates (ongoing).

Action 2:

The Program will continue to assess its expected outcomes and indicators on an annual basis, and implement adjustments based on legislative and regulatory changes (such as is currently being conducted for harassment and violence prevention) (ongoing).

Program and evaluation overview

Program

The Occupational Health and Safety Program (“the Program”) is administered by the Labour Program in Employment and Social Development Canada and is composed of the Workplace Directorate,Footnote 2 and the Regional Operations and Compliance Directorate.Footnote 3

The Program enforces the occupational health and safety provisions under Part II of the Canada Labour Code for federally regulated* workplaces.

The Program strives to ensure safe and healthy workplaces for all federal jurisdiction employees by preventing or reducing the incidence of work-related injuries and fatalities in federal jurisdiction workplaces. This is done through awareness of health and safety issues and assisting employers and employees understand their duties and rights.Footnote 4

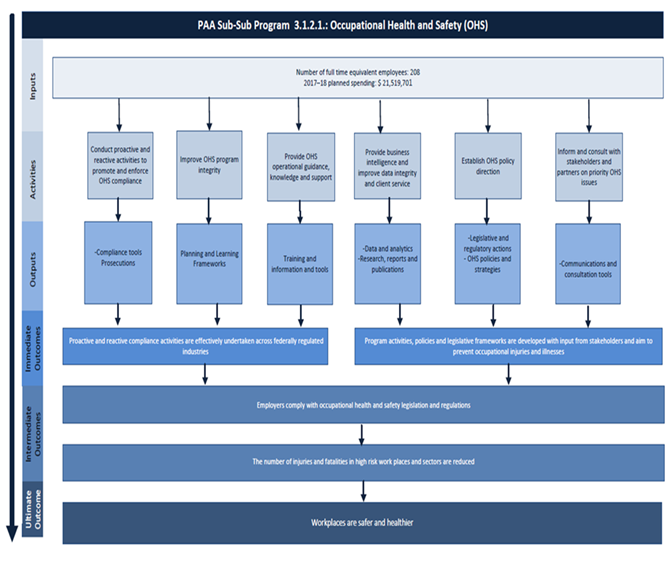

The Program’s logic model in Annex B outlines its activities, outputs, and expected outcomes.

The average annual program spending between fiscal year 2011 to 2012 and fiscal year 2015 to 2016 was $16.8 million.Footnote 5 See Annex C for more information about the program and a breakdown of program spending.

Evaluation

The evaluation assessed the Program’s performance by examining its:

- emerging issues and challenges

- proactive and reactive activities

- implementation of changes to Part II of the Canada Labour Code, and

- data collection and performance measurement strategies or practices

These issues were guided by 8 evaluation questions (Annex D) and relied upon 5 lines of evidence (Annex E).

Context

The changing nature of work may be making the standard definitions of employment outdated, including some employee occupational health and safety protections in federally regulated workplaces

Non-standard employment and health issues continue to emerge:

- unionization rates are declining and non-standard work arrangements are increasing (for example, term, contract* and casual employment).

- these developments have led to a rise in vulnerable* workers which can be associated with reduced control over working conditions and/or protections of rights.

- employees’ mental health and well-being in the workplace has also been a growing issue.

Technology is changing the workplace:

- technological advancements are broadening the scope of the physical workplace allowing more variations, such as telework.

- the increasing use of technology is altering the nature of work and leading to health and safety concerns.

Key findings

Modernize regulations and support vulnerable employees

The Program is working towards updating and modernizing regulations to reflect the changing nature of the workplace

Most advanced economies lack the capacity in their management of Occupational Health and Safety or its regulatory system to address emerging issues arising from precarious, casual, and temporary employment* (Gallagher, 2012).

- Between 1997 and 2017, the proportion of temporary workers increased by 2.2 percentage points to reach 11.6%, or 2.1 million of the total workforce* in Canada.Footnote 6

- Contract employment experienced the biggest rise as a form of temporary employment, growing by almost 97% in the same period.Footnote 7

Mental health in the workplace was also identified as an issue that has emerged.

- Employer and employee interviewees reported becoming increasingly aware of mental health issues in the workplace, including its intersection with drugs, alcohol, and violence.

- Employers reported concerns regarding mental health issues in the workplace, including the scope of their responsibility, the challenges in investigating and capturing information, and the need for expertise and specialized services.

Employer interviewees noted that the rise in technology is increasing the risk of potential health issues.

- Program officials noted that violations related to handling hazardous materials were frequent, and employers noted the need for improvements to address technical issues.

The program has a number of tools to address emerging issues, such as providing website information on stress, violence and bullying; consulting with the tripartite Occupational Health and Safety Advisory Council; maintaining contact with field staff regarding emerging issues on the ground; and leveraging research conducted by the Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety.

Gender-based analysis plus

The Program collects limited gender-based plus information on vulnerable employees in both temporary and permanent employment situations

Disaggregated employee-related information, by type of employment, and other key areas such as gender and representation (for example, disability, minorities), is not collected by the Program.Footnote 8 This information could support the monitoring and reporting of information that could support strategic decision-making.

Gender-based information in the 2015 Federal Jurisdiction Workplace Survey indicates that 19% of women and 11% of men in federally regulated workplaces are part-time employees.Footnote 9

A survey conducted by Statistics Canada in 2017 found that women represented almost 52% of temporary workers in Canada. This proportion has been fairly consistent since 1997.

Between 1997 and 2017, the growth of women representation in temporary employment* was almost 75%, as compared to men at almost 59%.

Interviewees noted a need for greater Program support regarding emerging issues related to the more vulnerable* groups, such as protection for employees hired by human resource agencies, and employer safety compliance within non-traditional work arrangements, such as telework.

Legislation

The program has implemented several legislative changes, however, there is an indication that further training is needed to ensure a clear understanding of certain notions in the Code

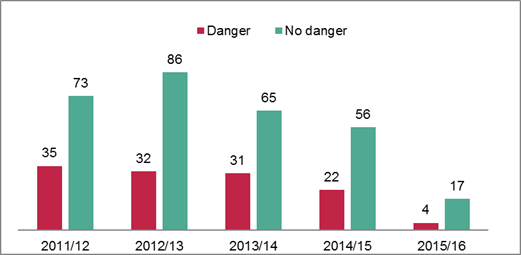

During the evaluation period, the majority of the refusal of dangerous work cases were found to present no danger.

Employers noted that it may be unclear to employees what constitutes a danger-related complaint.Footnote 10

Employees indicated that Labour Program inspection officers’ training was insufficient, which resulted in them not always being able to identify complex dangers or hazards.Footnote 11

In 2014, the definition of ‘danger’* was amended to:

- clarify its intended use for employers and employees

- channel non-dangerous cases through their applicable mechanisms, and

- encourage the use of the internal responsibility system* and the Hazard Prevention Program*

In fiscal year 2015 to 2016, the number of refusal of dangerous work cases reaching the Program decreased by 73%.Footnote 12

The Program does not collect data that could identify the cause for this drop nor track the cases managed through the internal responsibility system.

Figure 1 - Text version

| Year | 2011 to 2012 | 2012 to 2013 | 2013 to 2014 | 2014 to 2015 | 2015 to 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Danger | 35 | 32 | 31 | 22 | 4 |

| No danger | 73 | 86 | 65 | 56 | 17 |

- Source: Labour Application 2000 database

Compliance

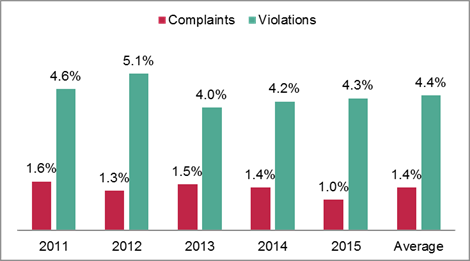

A majority of employers comply with Part II of the Canada Labour Code, and there has been compliance improvements since 2012

A sector’s violation rate may be affected by the extent it is targeted for proactive inspections. This may result in higher violation rates in high risk sectors.

The number of employers in a sector, and the violation rate per employer, are 2 different indicators in understanding the degree of code violations.Footnote 13

- Employers in the trucking sector had a below average violation rate of 3.6%, however this sector had the highest total employer population at 60%.

- Employers in the public service sector composed less than 2% of the total employer population, these employers had an annual violation rate of 16.2%.

Figure 2 - Text version

| Year | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complaints | 1.6% | 1.3% | 1.5% | 1.4% | 1.0% | 1.4% |

| Violations | 4.6% | 5.1% | 4.0% | 4.2% | 4.3% | 4.4% |

- Source: Labour Application 2000 database.

An average of 4.4% of employers had at least one violation against Part II of the Canada Labour Code, in each calendar year of the evaluation.

While an average of 1.4% of employers received a complaint filed with the Program in a year.

Awareness of regulations

Most employers and employees were aware of their rights and responsibilities

The evaluation surveys of federally regulated* employers and employees indicated that:

- 91% of employers and 71% of employees found that occupational health and safety regulations adequately ensured a safe workplace

- 92% of employers and 75% of employees stated that employers comply with the requirement to provide employees with information on their occupational health and safety rights and responsibilities, and

- 91% of employers and 79% of employees said that employees fulfill their responsibility to report hazards and contraventions

Employer and employee survey responses indicated that each party had a strong awareness of each party’s rights and responsibilities under Part II of the Canada Labour Code.Footnote 14

However, employees were consistently less favorable than employers regarding each party’s degree of compliance with their rights and responsibilities.Footnote 15

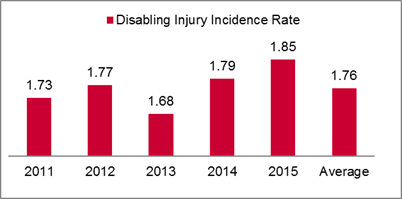

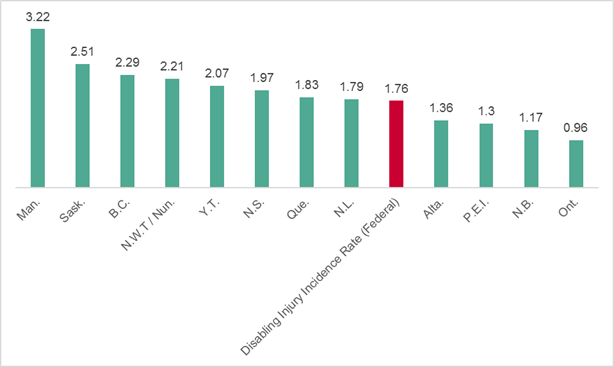

Disabling injury incidence rate

The federal jurisdiction has achieved success in reducing its disabling injury incidence rate, but it still lags behind some provincial levels

During the evaluation period, the Disabling injury incidence rate* was a key program indicator that measured safety levels in federally regulated* workplaces.Footnote 16 Between 2011 and 2015, the 2% annual reduction target for this Rate was only achieved in 2013.

As employment under the federal jurisdiction continued to rise, the number of federal inspection officers* declined annually until fiscal year 2015 to 2016, when it rose sharply by 43%.Footnote 17

The five-year average for this federal level incidence rate compared favourably with most provincial and territorial time-loss work injury ratesFootnote 18 over the same period.

The federal level rate lagged 4 provinces, with Ontario being in the lead at 46% lower than the federal rate.Footnote 19

Other available data indicates that nearly all of the provinces and territories registered declines in their work loss-time injury rates over 2011 to 2015.Footnote 20

During the evaluation period, the Disabling injury incidence rate increased from 1.73 to 1.85 disabling injuries per 100 full-time equivalents. This is largely due to changes in reporting practices by one industrial sector representing approximately 5% of employees.Footnote 21

Figure 3 - Text version

| Year | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disabling injury incidence rate | 1.73 | 1.77 | 1.68 | 1.79 | 1.85 | 1.76 |

- Source: Administrative Data Technical Study

Proactive and reactive activities

Improvements in the use of proactive activities would encourage greater employer compliance to the Code

The literature review indicated that proactive activities are viewed as a best practice.Footnote 22

The document review showed that inspections help prevent incidents, injuries and illnesses.Footnote 23

Proactive activities are included in the Program’s 2015 Strategic Operational Plan, including performing scheduled inspections to identify violations.

During the evaluation period, the administrative data review indicated that:

- the Program dedicated an average of 57% of all assignment hours towards proactive activities, thereby missing its annual target of spending 80% of its assignment hours on proactive work; and

- the relative number of inspections amongst the lowest compliant sectors was inconsistent over the evaluation period, thereby potentially skewing the calculated number of violations found.

As well, there was generally an inadequate number of Program officers available to undertake compliance and enforcement activities, particularly proactive inspections.Footnote 24

- For instance, the number of officers per employee under the federal jurisdiction dropped by 54% between 2007 and 2011.Footnote 25

As indicated in Table 1, the Program did less proactive inspections by the end of the evaluation period, but found more violations during each inspection.Footnote 26

| Fiscal year | Number of proactive inspections completed | Percentage change in the number of completed proactive inspections | Total violations found | Average number of violations per proactive inspection | Potential number of disabling injuries prevented |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 to 2012 | 2,653 | Not applicable | 12,010 | 4.5 | 875 |

| 2015 to 2016 | 1,465 | 45% decrease | 7,652 | 5.2 | 483 |

The literature review found that each proactive inspection reduced the number of disabling injuries in the following year by 0.33 on average.Footnote 27 Based on this, Table 1 shows the potential number of disabling injuries that was prevented based on the number of proactive inspections completed during the first and last fiscal years of the evaluation period.

The literature also proposed a targeting tool that suggests conducting the same number of proactive inspections, but shifting some inspections to sectors, such as the public service, where the Program could have a greater impact in reducing the injury rates.Footnote 28

The average cost and time to resolve a violation increased over the evaluation period, resulting in a 19% average increase in Program expenses to resolve each violation.Footnote 29

Internal complaint resolution process

The internal complaint resolution process does not sufficiently support some employees’ needs

Employees can initiate the internal complaint resolution process* where they perceive a situation is non-dangerous, or dangerous if it were ever carried out. Unlike a Refuse to Work situation, the employee continues to work, while collaborating with their employer to seek a resolution to the matter.

The complaints process has been an effective mechanism for identifying violations, with a possible 79% of complaints over the evaluation period resulting in a violation.Footnote 30

As shown in Table 2, the evaluation survey found that most employees who had made an Occupational Health and Safety complaint were unsatisfied with various aspects of the complaint process.Footnote 31 For example, while all employers believed their organization had made changes based on a complaint, 66% of employees said that changes were not made.

| Employees and employers | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Employees unsatisfied with the overall process | 60% |

| Employees who disagree with the amount of time it took to resolve their complaint | 55% |

| Employees unsatisfied with the inspection officer’s help during the process | 49% |

| Employees who believe the ruling on their complaint was unfair and inaccurate | 59% |

| Employees who found the level of effort required to make a complaint unreasonable | 55% |

| Employers who found the level of effort required to resolve a compliant unreasonable | 14% |

| Employees who believe their organization did not make changes based on their complaint | 66% |

| Employers who believe their organization did make changes based on the complaint | 100% |

Performance measurement and data collection

The Program data collection systems need improvement to more accurately capture its client universe, and to support performance measurement

Data collection and reporting

The Program’s database of employers contains information on those who make themselves known to the Program.Footnote 32 As a result, some employers do not receive program services such as inspections, and some employers and employees are not aware Program consultation processes and educational material developed.

In order to improve data integrity, the Program has identified the need to improve the employers’ compliance with their legislative requirement to annually report on hazardous occurrences, as a priority.Footnote 33

A 2017 Employment and Social Development Canada Innovation Lab study and evaluation interviews found the report used to collect annual injury data requires core modifications, such as a simpler format and clearer instructions, in order to improve the response rate. This was corroborated by evaluation interviewee feedback.

Labour database

The Integrated Labour System, which is in the process of replacing the current Labour databases, is expected to centralize all data, as well as improve data timeliness and integrity issues.Footnote 34

Information agreements

The document review indicated that the Program does not have data sharing agreements with all provincial and territorial Worker Compensation Boards or commissions, or other relevant parties.Footnote 35

Information gaps in measuring program performance limit the Program’s ability to effectively support and improve employer compliance

Gaps in measuring program performance

The Program’s ability to conduct certain program activities (for example, monitoring program performance, strategically planning for proactive and reactive activities, and raising awareness to employers and employees) is limited due to the lack of information on the complete employer universe.

The Disabling Injury Incidence Rate, a Key Performance Indicator utilized during the evaluation period, is used to inform the strategic planning of inspections for high risk sectors. The results for each year of the evaluation are considered representative of the Disabling Injury Incidence Rate in the federal jurisdiction.

Internal Audit noted the Program’s limited capacity to measure and report on its performance with the current set of indicators, such as the Disabling Injury Incidence Rate*. This indicator is not considered to be a predictive indicator.Footnote 36

In addition, the following information was not available for this evaluation or was incomplete.

- Data on hazards related to vulnerable* workers, temporary employment*, and mental health issues was lacking.

- Data on Occupational Health and Safety Direction* orders by sector, issued by the Program to employers regarding dangerous work situations was not available.

- Data on employers in violation of the Canada Labour Code, Part II, after they were found in violation in previous years, was not available.

- Program costing information, such as the average cost to conduct an inspection, was not available.

Recommendations

The program continues to make significant progress in establishing and protecting federally regulated employees’ rights to a safe and healthy work environment. In order to further support the achievement of program outcomes, the following recommendations are offered:

Recommendation 1: Increase awareness of occupational health and safety to address emerging challenges, prevent future issues and risks, and further support vulnerable workers.

Recommendation 2: Explore ways to increase proactive activities, including strategically targeted inspections in high risk sectors, in order to detect violations and prevent potential injuries and/or illnesses.

Recommendation 3: Identify and address issues that may have hindered the effectiveness of the internal complaints resolution process, and develop service standards to address violations in a timely and effective manner.

Recommendation 4: To support monitoring and reporting activities, the program could improve performance measurement practices to capture reliable information with respect to key metrics, such as incidence rates, compliance levels, and the severity of violations.

Annexes

Annex A - Definitions

- Assurance of voluntary compliance:

- A written commitment by an employer or employee to correct a contravention related to a non-dangerous situation within a specified time. Employers and employees are required to inform the Program of their corrective action taken to address the Assurance of voluntary compliance.

- Contract employment:

- Statistics Canada defines this form of temporary employment, which includes temporary help agency work, as having a termination date.

- Danger (pre October 2014):

- Any existing or potential hazard or condition or any current or future activity that could reasonably be expected to cause injury or illness to a person exposed to it before the hazard or condition can be corrected, or the activity altered, whether or not the injury or illness occurs immediately after the exposure to the hazard, condition or activity, and includes any exposure to a hazardous substance that is likely to result in a chronic illness, in disease or in damage to the reproductive system.

- Danger (post October 2014):

- Any hazard, condition or activity that could reasonably be expected to be an imminent or serious threat to the life or health of a person exposed to it before the hazard or condition can be corrected or the activity altered [Subsection 122(1)].

- Direction:

- A formal written order directing an employer or employee to correct a contravention within a specified period. Issued during inspections or investigations, where either the Assurance of voluntary compliance was unaddressed or the situation is deemed dangerous.

- Disabling injury incidence rate:

- the total number of disabling and fatal occupational injuries per 100 employees, expressed as full-time equivalents (FTEs). It is calculated by taking the sum of the total number of disabling and fatal injuries on the job divided by the total number of FTEs and multiplied by 100.

- Extended jurisdiction:

- Extended jurisdiction partners to Employment and Social Development Canada (for example, a Transport Canada official responsible for air or rail safety) to whom the Minister of Labour has delegated his/ her powers, duties and functions to administer Part II of the Canada Labour Code.

- Federal inspection officers:

- Beyond those employed by the Labour Program, this includes officers from the National Energy Board and Transport Canada.

- Federally regulated employers under Part II of the Canada Labour Code:

- Applies to interprovincial and international industries, and includes workplaces in the private and public sectors, including crown corporations. See Annex G for details.

- Hazardous Prevention Program:

- Part XIX of the Regulations, entitled Hazard Prevention Program, covers obligations concerning the identification of hazards, the assessment of those hazards, the choice of preventive measures, and employee education.

- Internal complaint resolution process:

- A process established by the Occupational Health and Safety legislative process that allows for a graduated series of investigations to resolve work place issues while maintaining employment safety. The process allows for the resolution of work place health and safety issues in a more timely and efficient manner and reinforces the concept of the internal responsibility system.

- Internal responsibility system:

- An underlying philosophy of occupational health and safety legislation in Canada. All workplace parties are responsible for health and safety at their work place; employers, in consultation with workplace parties are required to implement measures and control procedures that are appropriate for their individual workplaces. The System is supported by Health and Safety Representatives in workplaces with less than 19 employees, by Workplace Committees in workplaces with more than 20 employees, and by Policy Committees in work places with more than 300 employees.

- Non-standard employment:

- Can consist of part-time or temporary work, or self-employment (Chaykowski, R., 2008).

- Prosecution:

- Court proceedings based upon non-compliance with provisions of the Canada Labour Code, Part II. Usually pursued as a result of serious contravention or when a Direction has not been addressed. Involves escalating fines and/or imprisonment based on the offence, with a maximum penalty of two years in prison and $1 million dollars for willfully committing an act likely to cause serious injury or death.

- Total workforce/employment:

- All forms of employment, or the combination of non-standard and standard employment (Statistics Canada).

- Temporary employment:

- Casual, seasonal, or term/contract. It also includes work via temporary help agencies (Statistics Canada).

- Vulnerable workers/employees:

- Workers with low wages and benefits and in non-standard work arrangements and hours (Chaykowski, R. 2008).

Annex B - Program logic model (2017)

Annex B - Text version

Annex B presents the Occupational Health and Safety program logic model, which outlines the program’s inputs, activities, outputs, immediate outcomes, intermediate outcomes, and the ultimate outcome it intends to achieve or towards which it intends to contribute.

Inputs

- Number of full time equivalent employees: 208

- 2017 to 2018 planned spending $21,519,701

Activities

Inputs 1 and 2 are expected to produce the following six activities:

- Conduct proactive and reactive activities to promote and enforce occupational health and safety compliance.

- Improve occupational health and safety program integrity.

- Provide occupational health and safety operational guidance, knowledge and support.

- Provide business intelligence and improve data integrity and client service.

- Establish occupational health and safety policy direction.

- Inform and consult with stakeholders and partners on priority occupational health and safety issues.

Outputs

Activity 1 is expected to produce:

- Output 1 Compliance tools and prosecutions

Activity 2 is expected to produce:

- Output 2 Planning and learning frameworks

Activity 3 is expected to produce:

- Output 3 Training and information and tools

Activity 4 is expected to produce:

- Output 4 Data and analytics, and research, reports and publications

Activity 5 is expected to produce:

- Output 5 Legislative and regulatory actions, and OHS policies and strategies

Activity 6 is expected to produce:

- Output 6 Communications and consultation tools

Immediate outcomes

Outputs 1, 2, and 3 are expected to produce:

Immediate outcome 1: Proactive and reactive compliance activities are effectively undertaken across federally regulated industries.

Output 4, 5, and 6 are expected to produce:

Immediate outcome 2: Program activities, policies and legislative frameworks are developed with input from stakeholders and aim to prevent occupational injuries and illnesses.

Intermediate outcomes

Immediate outcomes 1 and 2 are expected to contribute towards:

Intermediate outcome 1: Employers comply with occupational health and safety legislation and regulations.

Intermediate outcome 2: The number of injuries and fatalities in high risk work places and sectors are reduced.

Ultimate outcome

Intermediate outcome 2 is expected to contribute towards:

Ultimate outcome 1: Workplaces are safer and healthier.

Annex C - Program background

Program background

Conduct proactive activities that support employer and employee compliance to Part II of the Canada Labour Code. This includes conducting annual inspections, investigations sourced by employee complaints, developing information tools, supporting the employer internal responsibility system*, and issuing Assurances of Voluntary Compliance*.

Engage in reactive activities to enforce compliance. Activities include conducting investigations, and pursuing legally binding actions such as issuing Directions* for dangerous situations and initiating prosecutions*.

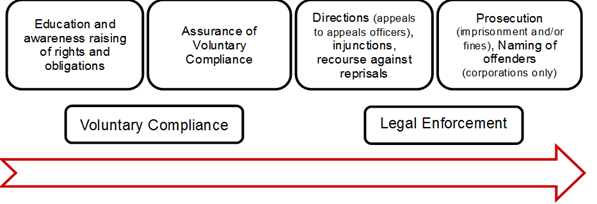

The continuum of proactive to reactive measures applied to align an employer’s compliance with Part II of the Canada Labour Code.

Annex C - Text version

The continuum of proactive to reactive measures applied to align an employer’s compliance with Part II of the Canada Labour Code consists of four steps.

A large arrow from left to right indicates that as employers move right through the four steps of the continuum, the measures evolve from those that apply voluntary compliance to those that apply legal enforcement.

Step 1 is education and awareness raising of rights and obligations

Step 2 is Assurance of voluntary compliance

Step 3 is Directions (appeals to appeals officers), injunctions, and recourse against reprisals

Step 4 is Prosecution (imprisonment and/or fines), naming of offenders (corporations only)

Actual annual program spending by fiscal year

| Year | 2011 to 2012 | 2012 to 2013 | 2013 to 2014 | 2014 to 2015 | 2015 to 2016 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spending | $12.9M | $12.0M | $12.6M | $21.8M | $24.6M | $16.8M |

| Sources | Financial branch, ESDC | 2014 to 2015 and 2015 to 2016 ESDC Departmental Performance Reports | n/a | |||

Annex D - Evaluation questions

- To what extent does the program respond to the need to establish health and safety standards for employees under federal jurisdiction?

- To what extent is the current mix of proactive and reactive assignments effective in encouraging compliance with the Canada Labour Code, Part II?

- To what extent does the use of different mechanisms of enforcement (issuance of Assurance of voluntary compliance, Directions Investigation of complaints, filling orders or Prosecution in federal court) help to correct and/or prevent a breach of the Canada Labour Code, Part II?

- To what extent are training and policy and regulatory development in headquarters aligned with the operational requirements of the program in the regions?

- To what extent are the regulations implemented by the program adequate to accomplish its stated outcomes?

- To what extent do the programs effectively target the sectors/areas/sections of legislation where non-compliance is higher?

- To what extent have recent legislative and regulatory changes affected the program’s performance?

- Are there other types of activities which would be more cost effective?

Annex E - Lines of evidence: descriptions and limitations

The five lines of evidence are the literature review, the document review, administrative data review, key informant interviews, and a survey of employers and employees. Each line of evidence includes a description and its limitations.

Literature review

Description: An examination of Occupational Health and Safety issues during the evaluation period, as well as recent issues and emerging issues (external documents, studies).

Limitation: There was a limited amount of literature related directly to the federal Occupational Health and Safety program.

Document review

Description: An analysis of internal Government of Canada, Employment and Social Development Canada documents, during the evaluation period, to better understand program activities.

Limitation: There may be a gap in the information available, given that the document review was solely based on readily available documents. Some internal, unpublished Labour Program documents or studies were difficult to obtain.

Administrative data review

Description: An analysis of administrative data from the Labour Program’s Labour Application 2000 database was conducted.

Limitation: The evaluation team (including contractors) did not have direct access to the Labour Application 2000 database therefore, the data analysis may not be comprehensive.

Key informant interviews

Description: Interviews were conducted with 57 key informants, within 6 groups: program officials, labour law experts, employer and employee representatives, extended jurisdiction* partners and provincial labour officials.

Limitation: The views of key informants are subject to biases. Additionally, the limited sample of respondents may not be representative of the views of other non-respondents.

Survey of employers and employees

Description: 344 employers and 140 employees responded to the surveys. The surveys assessed aspects, such as satisfaction with program services, understanding of procedures, and awareness of proactive activities.

Limitation: Employers and employees known to be federally regulated, with available contact information, were included. The initial target was 650 for both surveys. Only 344 out of 6,100 employers responded to the survey. Only 140 of nearly 3,000 employees responded. Therefore, the sample is not fully representative of employees and employers in the federal jurisdiction.

Annex F - Employee rights and specific survey questions

The three employee rights under Part II of the Canada Labour Code:

- the Right to know: Employees have the right to be informed of known or foreseeable hazards in the work place and to be provided with the information, instruction, training and supervision necessary to protect their health and safety;

- the Right to participate: As health and safety representatives or committee members, employees have the right and the responsibility to participate in identifying and correcting job-related health and safety concerns through an internal complaint resolution* process; and

- the Right to refuse dangerous work: If the person has reasonable cause to believe that a condition exists at work that presents a danger to himself or herself; the use or operation of a machine or thing presents a danger to the employee or a co-worker; and the performance of an activity constitutes a danger to the employee or to another employee.

| Survey issues | Employers’ awareness | Employees’ awareness | Employee view on compliance with the issue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Question 1: Employees must follow prescribed health and safety procedures and take necessary precautions | 99% | 97% | 69% |

| Question 2: Employer must disseminate to employees a record of hazardous substances in the workplace | 93% | 87% | 68% |

| Question 3: Employer must appoint a health and safety representative who has been selected by the employees (only asked if fewer than 20 employees) | 82% | 78% | 61% |

Questions 4 to 9:

|

All responses were in the 90% - 100% range | All responses were in the 90% - 100% range | All responses were in the 70% to 80% range |

Annex G - Federal jurisdiction sectors under Part II of the Canada Labour Code

Occupational health and safety in the federal jurisdiction has been consolidated under Part II of the Canada Labour Code. The Code applies to the following interprovincial and international industries, and includes workplaces in the private and public sectors, including crown corporations:

- Railways

- Highway transportation

- Telephone and telegraph systems

- Pipelines

- Ferries, tunnels and bridges

- Shipping and shipping services

- Radio and television broadcasting and cable systems

- Airports

- Banks

- Grain elevators licensed by the Canadian Grain Commission, and certain feed mills and feed warehouses, flour mills, and grain seed cleaning plants

- The federal public service and persons employed by the public service and about 40 Crown corporations and agencies

- Employment in the operation of ships, trains and aircraft

- The exploration and development of petroleum on lands subject to federal jurisdiction.

The federal public service and persons employed by the public service, and more than 40 Crown corporations and agencies (as defined by Part 3 of the Federal Public Service Labour Relations Act and Schedules I, IV and V of the Financial Administration Act).

Part II of the Canada Labour Code does not apply to certain undertakings regulated by the Nuclear Safety and Control Act.

Annex H - Provincial, territorial and federal average injury rates

The Disabling injury incidence rate* (federal) is the combined rate of disabling and fatal injuries that occurred in federal jurisdictional workplaces. This rate indicates that, as an annual average over the 2011 to 2015 period, there were 1.76 full-time equivalents for every 100 full-time equivalents working under the federal jurisdiction that experienced either a disabling injury or fatality.

The provincial and territorial average time-loss work injury rates count only disabling injuries, also known as time-loss injury rates.

Figure 4 - Text version

| Provinces and Territories | Rate |

|---|---|

| Manitoba | 3.22 |

| Saskatchewan | 2.51 |

| British Columbia | 2.29 |

| North-West Territories and Nunavut | 2.21 |

| Yukon Territories | 2.07 |

| Nova Scotia | 1.97 |

| Quebec | 1.83 |

| Newfoundland | 1.79 |

| Disabling Injury Incidence Rate (Federal) | 1.76 |

| Alberta | 1.36 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1.3 |

| New Brunswick | 1.17 |

| Ontario | 0.96 |

- Source: Association of Workers’ Compensation Boards of Canada and the Evaluation Administrative Data Review Technical Study.

Annex I - References

Anderson, J. (2015). Waiting to happen: why we need major changes to the health and safety regime in federally regulated workplaces (PDF, 1.25 MB). Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

Arntz-Gray, J. (2016). Plan, Do, Check, Act: The need for independent audit of the internal responsibility system in occupational health and safety. Safety Science, 84, 12-23.

Association of Workers’ Compensation Boards of Canada, 2018. Key Statistical Measures), Summary Tables: Statistics: Detailed Key Statistical Measures Report, 2011 to 2015.

Canada Labour Code, Part II - Current to September 16, 2018, (Last Amended December 12, 2017).

Dean, T., & Ontario Ministry of Labour. (2010). Expert Advisory Panel on Occupational Health and Safety Report and Recommendations to the Minister of Labour. Toronto, Ont.: Ministry of Labour.

Employment and Social Development Canada. (2017). 2016 to 2017 Internal Audit Services Branch Annual Follow-up on Internal Audit Management Action Plans.

Employment and Social Development Canada. (2018). 2016 Internal Audit Report on Occupational Health and Safety.

Employment and Social Development Canada, (2018). Labour Program, Open Government datasets, “Occupational Injuries Amongst Canadian Federal Jurisdiction Employers by Province: 2008 to 2016”.

Employment and Social Development Canada. (2015). Departmental Performance Report 2014 to 2015 and 2015 to 2016.

Employment and Social Development Canada. (2018). Profile of Temporary Workers in 2017, with Statistics Canada data sources.

Employment and Social Development Canada. (2016). Labour Program. Optimizing Health and Safety Inspections in Canada.

Employment and Social Development Canada. (2015). Labour Program. Optimizing Health and Safety Inspections in Canada - PowerPoint Presentation.

Gallagher, C., & Underhill, E. (2012). Managing work health and safety: recent developments and future directions. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 50(2), 227-244.

Law Commission of Ontario (2012). Vulnerable Workers and Precarious Work: Final Report. Toronto, Ont.: Law Commission of Ontario.

St. Amant, P-A. (2016). Optimizing Health and Safety Proactive Inspections in Canada. Gatineau, Que.

Statistics Canada. 2015 Federal Jurisdiction Workplace Survey.

Statistics Canada. 2017 Labour Force Survey.

Technical Studies in support of this evaluation (not published, but are available upon request):

- Occupational Health and Safety Document Review (prepared by Daria Sleiman, Evaluator, Employment and Social Development Canada) - August 2018

- Occupational Health and Safety Literature Review (prepared by Ron Logan, Evaluator, Employment and Social Development Canada) - August 2018

- Occupational Health and Safety Administrative Data Review (prepared by R.A. Malatest and Associates) - August 2018

- Occupational Health and Safety Key Informant Interviews (prepared by R.A. Malatest and Associates and ESDC Evaluation) - August 2018

- Occupational Health and Safety Surveys of Employees and Employers (prepared by R.A. Malatest and Associates) - August 2018

Tucker, S., Keefe, A. (2018). 2018 Report on Work Fatality and Injury Rates in Canada. Regina: University of Regina.

Vosko, L. F., Tucker, E., Gellatly, M., & Thomas, M. P. (2011). New approaches to enforcement and compliance with labour regulatory standards: The case of Ontario, Canada. Toronto: Osgoode Hall Law School, York University.