Evaluation of the Employment Insurance Parents of Critically Ill Children benefit

On this page

Alternate formats

Evaluation of the Employment Insurance Parents of Critically Ill Children Benefit [PDF - 1.31 MB]

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

1. Introduction

This evaluation assesses whether the Employment Insurance (EI) program's Parents of Critically Ill Children (PCIC) benefit was effective in meeting its policy objectives. The benefit provided temporary financial support to working parents who must interrupt their employment to provide care to a child under the age of 18 with a life-threatening illness or injury.

The evaluation looks at the benefit from its inception in early June 2013 to early December 2017 when the benefit was replaced by the Family Caregiver Benefit for Children, which intended to address some of the PCIC benefit's shortcomings and is highly similar in overall approach and designFootnote 1. This evaluation was conducted with the intent to inform the new benefit.

The overall evaluation approach and methodology are summarized in the annexes.

Key evaluation results

Six key findings emerged from this evaluation:

- low levels of awareness and incomplete understanding of the benefit were key barriers to accessing the benefit, particularly in the early years of implementation

- the benefit was effective in easing financial pressures on parents in order to allow them more time to provide care to their critically ill or injured child

- the benefit also had noticeable non-financial impacts and positive effects on the personal lives of recipients

- the benefit helped keep claimants attached to the labour force, but the gradual alignment of provincial and territorial employment standards may have reduced their time on leave or created a barrier to access the benefit

- slower-than-usual speed of pay for the benefit was likely related to difficulties with submitting and/or processing appropriate PCIC-specific medical certificates

- the Manual Pay System, through which the benefit was administered, limited tracking and reporting functions for claimants and for the Department

Based on these findings, the evaluation recommends the following to the Department for the new Family Caregiver Benefit for Children:

- seek to increase the level of awareness and understanding of the EI Family Caregiver Benefit for Children following its December 2017 launch.

- explore the feasibility of migrating the administration of the EI Family Caregiver Benefit for Children from the Manual Pay System for applicants in order to allow self-serve functionality for applicants.

2. Program background

The benefit was introduced in June 2013 as a new special benefit available under the EI program. It complemented the existing EI Compassionate Care Benefit.

The EI Compassionate Care Benefit continues to provide temporary income support for those who leave work to provide care to a family member at end-of-life, in other words with serious medical condition with a significant risk of death within 26 weeks (see Employment Insurance Caregiving Benefits).

Main components of PCIC

Eligible parents of minor children were provided with temporary income replacement of up to 35 weeks within a 52-week window.

Requirements

Applicants must have shown that they:

- have accumulated 600 insured hours of work in the 52-week period before applying for PCIC or since the start of their last claim, whichever is shorter;

- are parents or legal guardians of a critically ill or injured child under 18 years; and

- submitted a PCIC medical certificate, signed by a specialist medical doctor, along with and authorization to release information form.

Self-employed workers were eligible, provided they:

- have earned up to or beyond the earnings threshold in the previous calendar year; and

- have opted into the EI program voluntarily and experienced a reduction in terms of time devoted to your business by more than 40% in order to provide care or support for a critically ill or injured child

Weekly Benefit

- As with other EI benefits, the weekly benefit amounts to 55% of the claimant's weekly insurable earnings, up to an established maximum ($543 in 2017).

Combining with Other Employment Insurance Benefits

- The PCIC benefit could also be combined with other EI benefits, for example, parental, compassionate care, sickness or EI regular benefits, provided that all eligibility conditions were met.

More information and statistics on other benefits offered through the EI program can be found in the annual Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report.

Employment Insurance Caregiving Benefits

The Employment Insurance program offers 3 types of caregiving benefits that are available to eligible applicants. These benefits help caregivers take time away from work to provide care or support to a critically ill or injured person or someone needing end-of-life care.

The 3 types of caregiving benefits:

- family caregiver benefit for children with a maximum of 35 weeks for a person who is critically ill or injured person under 18

- family caregiver benefit for adults with a maximum of 15 weeks for a person of 18 years of age or older who is critically ill or injured

- compassionate care benefits for a person of any age and who requires end-of-life care

Requirements

Applicants must show that they:

- are a family member of the person who is critically ill or injured or needing end-of-life care, or considered to be like a family member;

- earn less on a weekly basis by more than 40% for at least one week because they need to take time away from work to provide care or support to a family member of someone needing care or support;

- have accumulated 600 insured hours of work in the 52-week period before applying, or since the start of their last claim, whichever is shorter; and

- have a medical doctor or nurse practitioner who has certified that the person they are providing care or support to is critically ill or injured or needing end-of-life care.

More information on these benefits, including definitions related to these benefits, can be found at: Caregiving Benefits and Leave.

The benefit's uptake was at its highest level with 5,183 applications per year, below the 6,000 applications anticipated.

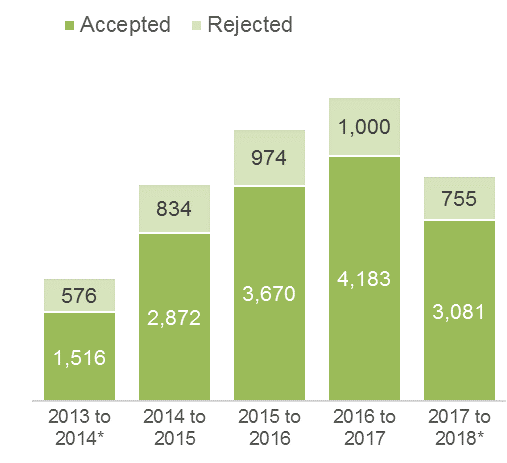

Using administrative data, between June 2013 and December 2017, just over 15,300 individuals received the benefit out of approximately 19,500 applicants. Just over 300 or about 2% of applications were submitted in paper format, and these were excluded from the analysis.

- Given that the start and end date of the benefit, data for the first and last fiscal years reflect a 9-month period rather than 12-month period

- In 2013, the share of accepted applications was 72% and slowly increased to 77% in 2014 to remain at 80% in the last three years of the program

- Throughout the report, all figures are based on over 15,300 recipients, unless otherwise specified. See Annex A for data sources

Text description of Figure 1

| Year | Number of accepted applicants | Number of rejected applicants | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 to 2014* | 1,516 | 576 | 2,092 |

| 2014 to 2015 | 2,872 | 834 | 3,706 |

| 2015 to 2016 | 3,670 | 974 | 4,641 |

| 2016 to 2017 | 4,183 | 1,000 | 5,183 |

| 2017 to 2018* | 3,081 | 755 | 3,836 |

* Represents approximately a 9-month period

Administrative data and interviews reported the following reasons to deny benefits:

- absence of a Record of Employment

- age of the Child (over 18 years old)

- insufficient insurable hours (below 600 hourrs)

- outside the 52-week window to add an additional EI benefit type on an existing claim

- medical certificate signed by non-specialist physician

- specialist did not consider child "at risk"

- missing dates in the medical certificate or period require was listed as "indefinite", "unknown", "terminal" or "lifelong condition"

Text description of Figure 2

| Year | Benefits paid in $ millions (based on the application date) |

|---|---|

| 2013 to 2014* | $12,5 |

| 2014 to 2015 | $20,6 |

| 2015 to 2016 | $24,4 |

| 2016 to 2017 | $27,7 |

| 2017 to 2018* | $20,2 |

* Represents approximately a 9-month period

Characteristics of applicants

| Characteristics | Recipients | Non-recipients are applicants whose claim was not successful |

|---|---|---|

| Number of applicants | Over 15,300, excluding 300 or 2% paper-based applications | Over 4,100 with an unknown number of paper-based applications |

| Women | 80% | 78% |

| Men | 20% | 22% |

| Under 25 years of age | 5% | 7% |

| Between 25 to 30 | 19% | 15% |

| Between 30 to 35 | 33% | 24% |

| Between 35 to 40 | 24% | 23% |

| Between 40 to 45 | 11% | 15% |

| Older than 45 | 7% | 17% |

| Inuit, Metis, Indian status | 3% | 6% |

| Non-Indian status | 4% | 5% |

| Person with disabilities | 0.4% | 0.6% |

| Visible minorities | 12% | 13% |

| Primary education | 2% | 4% |

| Secondary education | 24% | 33% |

| College | 32% | 32% |

| University | 36% | 25% |

| Other levels of education | 6% | 7% |

| Working earnings in the year before PCIC | $40,990 | $31,180 |

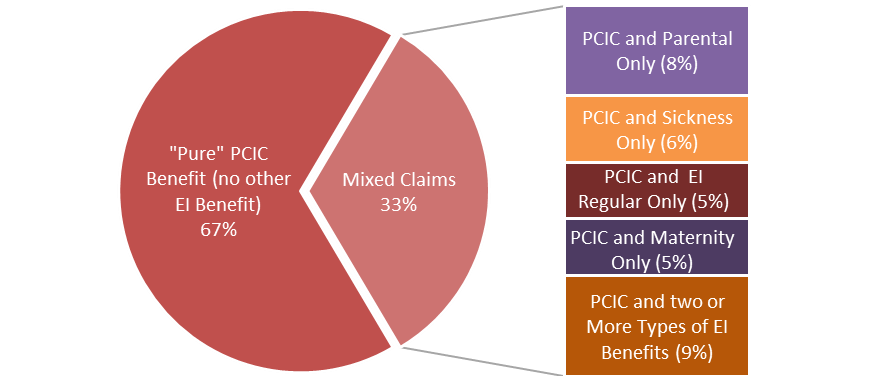

One out of three PCIC recipients (33%) combined their claim with other EI benefits (see Image A)

EI claimants are able to combine different types of benefits within a single benefit period (with some restrictions not relevant to this evaluation) if they meet eligibility requirements.

- If a claim included PCIC benefit, the entire claim was processed manually from that point onward—regardless if the claimant no longer collected the benefit and resumed a previous benefit type such as EI Parental —creating an additional layer of complexity in administering the benefit.

- The disadvantage of processing manual payments was related to the fact that recipients were not able to leverage any self-serve functionality such as status of payment, a feature that is usually available to claimants.

Using administrative data, it was found that mixed claims most commonly involved maternity and/or parental

- This likely reflects the young age of the majority of care recipients (68% of all claims involved a child that was less than one year old).

The fact that two-thirds of the claims did not involve another EI benefit is perhaps unanticipated.

- Amongst "pure" benefit recipients, half of these claimants were either parents of children that were 1-year old or older (at which point EI maternity and EI parental benefits were no longer available) or fathers of babies less than 1 year old. Representatives from hospitals and charities suggested that fathers were more likely to take the benefit at the same time with the mothers who were receiving EI maternity and/or EI parental benefits).

- Other factors could also partially explain why others did not combine their benefits, such as ineligibility due to the benefit period conditions, a need to return to work, or the death of the child.

Text description of Image A

| Benefit type | Percentage |

|---|---|

| "Pure" PCIC Benefit, no other EI Benefit | 67% |

| Mixed claims | 33% |

| PCIC and Parental benefit only | 8% |

| PCIC and Sickness benefit only | 6% |

| PCIC and EI Regular benefit only | 5% |

| PCIC and Maternity benefit only | 5% |

| PCIC and two or more types of EI benefits | 9% |

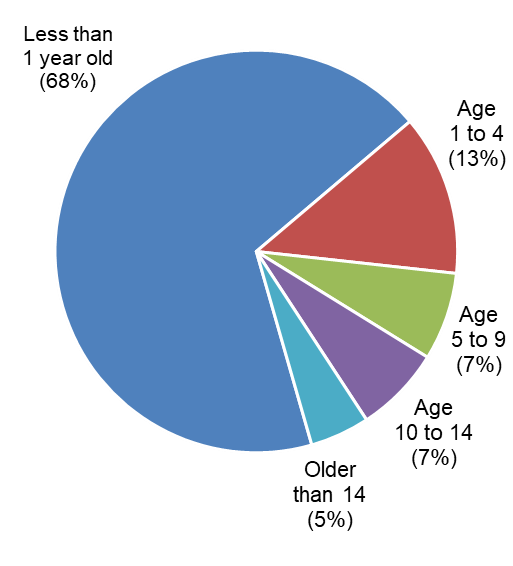

Parents applying for the benefit, generally did so to provide care to very young children—most less than 1-year old

Children of recipients

As shown in figure 3, among PCIC recipients, 68% of critically ill children were younger than 1-year-old.

- By contrast, children of non-recipients were generally older with 48% between the ages of 1 to 14

Text description of Figure 3

| Age bands | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Less than 1 year old | 68% |

| 1 to 4 | 13% |

| 5 to 9 | 7% |

| 10 to 14 | 7% |

| Older than 14 | 5% |

Though not shown in figure 3, the evaluation found that among claims for children of less than 2 months old, about 14% (just over 1,100 claims) were related to parents who had 2 or 3 critically ill or injured children.

- Canadian data shows that twins account for around 2% to 3% of all births while triplets account for 0.05% to 0.1%.

This would be consistent with the literature on neonatal outcomes where the rates of perinatal mortality, preterm births and low birth weights dramatically increase with multiple gestations.

Types of Critical Illnesses were identified by interviewees

According to Service Canada processing agents, the majority of applications were established for premature babies and newborn infants with serious medical conditions.

Cancer amongst young children was the second most frequent type of critical illness.

- Though childhood cancer is relatively rare overall (accounting for less than 1% of all new cancer cases in Canada according to health data), the Canadian Cancer Society indicates that leukemia, brain and central nervous system, and lymphomas are 3 types of cancer commonly seen amongst the ages of 1 to 14

- Upon being diagnosed, an initial and critical period of chemotherapy normally takes 4 to 6 weeks or up to 24 weeks depending if the cancer comes back

Hospital social workers indicated that injuries at home or caused by car accidents, and mental health issues were other reasons for applying for the benefit.

3. Key findings

Key Finding #1:

Low levels of awareness and incomplete understanding of the benefit were key barriers to accessing the benefit, particularly in the early years of implementation

As shown previously, the number of applicants for the benefit was below the 6,000 per year as initially expected, particularly in the first years of implementation.

- Representatives from hospitals and charities, medical doctors who issued a medical certificate, social workers who might have advised parents in the application process, and Service Canada processing agents, indicated that insufficient awareness of the benefit was a key barrier

General awareness

Interviewees indicated that a lack of awareness of the benefit led to many late applications, sometimes even 6 or 8 months, especially in early years

- Whenever possible, late applications were backdated to allow the benefit to be claimed, provided that all eligibility conditions were met

Uptake was further hindered by a misperception that the benefit was only available during the child's hospitalization.

Complexity of the benefit

Service Canada processing agents and, to some extent, social workers in hospitals believed that parents did not always understand all the facets of the benefit.

The structure of the benefit—designed to provide a significant degree of flexibility—may have also created a higher degree uncertainty for claimants.

- Claimants needed to take into account considerations around the timing of the benefit, sharing the entitlement, and the ability to combine with other EI benefits

Service Canada processing agents recognised that the PCIC benefit was complex, especially related to combining with other EI related benefits, and felt it was difficult to explain and to understand.

"That was a very big problem, especially in the early days; we had a hard time with explaining this concept when we had to deny parents out of the window. It is still a problem, but it was a bigger problem in the early days" (Service Canada agent)

- In particular, to combine different EI benefit, a claimant must receive at least $1 in PCIC benefit within the first 52 weeks of an established claim

- Processing agents recalled that at times, some agents had advised parents to exhaust existing benefits first not realizing the risk of becoming ineligible

Obtaining and processing applications with medical certificates

Interviewees indicated that the medical certificates required several steps and created difficulties for applicants and healthcare professionals:

- not all parents realized that they had to apply online with a medical certificate completed and signed by a specialist doctor

- parents also had to provide consent to release the medical certificate since doctors are not otherwise authorized to release patient information to a third party

- Incomplete applications caused delays in issuing payments within the service standard of 28 calendar days

The lack of a clear definition of a critical illness, intended to provide medical specialists flexibility, sometimes itself created a barrier in obtaining the required medical certificate.

- Social workers in hospitals believed that in many cases, the interpretation given to "life at risk" was "very doctor-dependent" and that some doctors were uncomfortable with the wording as "they were trying to stay hopeful"

- In other situations, doctors took a very strict interpretation of the definition and, as such, preferred to sign the medical certificate only if the children were in intensive care units or "ready to die at any minute"

- Service Canada processing agents acknowledged that the terms "critically ill" and "life at risk" could be a source of confusion, as these terms were at times interpreted by physicians as the child being at risk of death in the "near-term"

Challenges with the application process

A number of challenges were highlighted with respect to the application process that may have led to reduced uptake with those unfamiliar with the process of applying for EI benefits.

- Immigrant parents not fluent in either French or English and parents without previous experience applying for EI benefit, had difficulties accessing the benefit

- Hospital social workers noted that having a dedicated telephone line to assist parents during a critical event such as this, would have helped parents to navigate through the application process

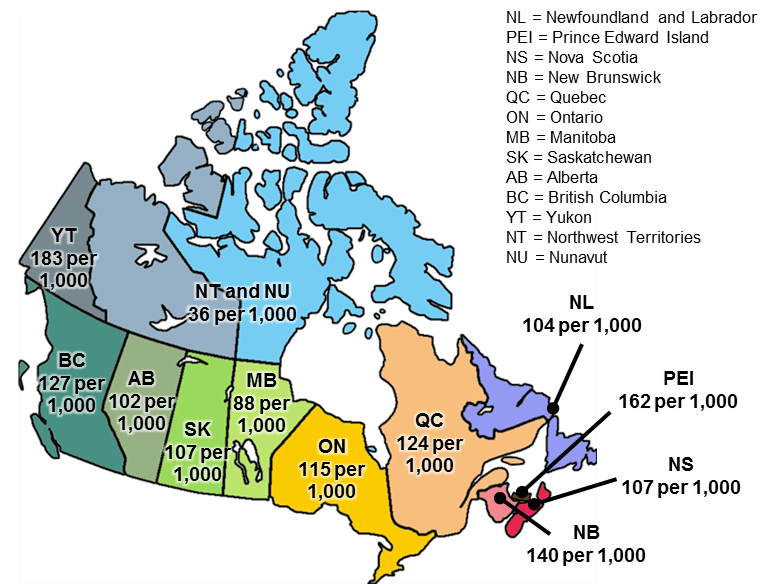

Some regions had particularly low levels of uptake compared to what might be expected based on Canadian health data.

- Over the 2013 to 2017 period, the number of applicants was reflective of the average rate of live births of pre-term babies with less than 37 weeks gestation across most regions of the country

However, some areas of the country, as shown in figure 4, had a much lower uptake compared to the national average of 114 PCIC claims per 1,000 pre-term live births:

- Alberta, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland & Labrador, Northwest Territories and Nunavut

Text description of Figure 4

| Provinces and Territories | Ratio of PCIC applicants for every 1,000 live births |

|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 104 |

| Prince Edward Island | 162 |

| Nova Scotia | 107 |

| New Brunswick | 140 |

| Quebec | 124 |

| Ontario | 115 |

| Manitoba | 88 |

| Saskatchewan | 107 |

| Alberta | 102 |

| British Columbia | 127 |

| Yukon | 183 |

| Northwest Territories and Nunavut | 36 |

- The reasons for these low levels cannot be determined based on aggregate data analysis, but could reflect low levels of awareness in those jurisdictions or challenges related to access among select populations or regions.

- Additional and targeted outreach and awareness activities for the implicated regions could be beneficial for the EI Family Caregiver Benefit for Children, which replaced the PCIC benefit in 2017.

Why pre-term births

As the majority of PCIC claims were for parents providing care to pre-mature babies, this metric gives a good sense of the expected distribution across the country. The number of applications of this type would likely be smaller, as not all pre-term live births result in serious medical conditions.

In addition to targeted regional outreach, further efforts are needed to raise awareness since estimates suggest that up to 30,000 children per year suffer non-trauma life-threatening conditions and trauma-related conditions such as injuries or accidents. Of these estimates, some may not meet the definition of the critically ill. (see Annex E for methodology).

Key Finding #2:

The benefit was effective in easing financial pressures on parents in order to allow them more time to provide care to their critically ill or injured child.

Social workers in hospitals noted during the interviews that the benefit gave more flexibility and allowed at least one parent (primarily the mother) to be away from work and to focus instead on the child and the child's treatment.

- Parents got involved in providing care to their ill child and received training given by medical staff

- In some situations where the mother was on maternity leave, the father applied for the PCIC benefit. In these cases, it allowed both the father and mother to take time off to focus on caring for their child

Service Canada processing agents and social workers reported that upon receiving the benefit, parents were "pleased", "very satisfied" or "happy" with the benefit.

- The benefit helped ease the financial stresses associated with caring for a critically ill or injured child, and provided some flexibility in managing family and work responsibilities

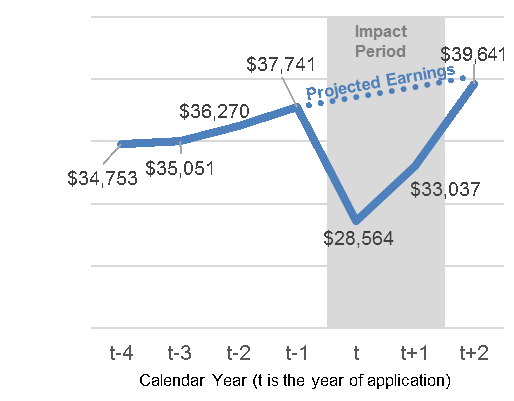

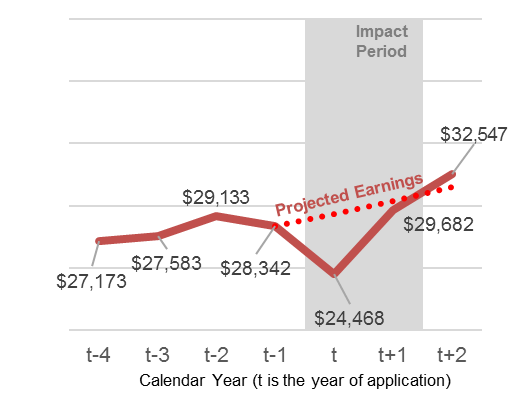

Based on a limited cohortFootnote 2, the impact analysis indicates that among applicants who were able to return to work in the two years following their application:

- the decrease in employment earnings during the potential benefit period was greater for recipients than non-recipients, suggesting benefit recipients were able to reduce their work hours to a greater extent (in line with the benefit's objective)

- average annual employment earnings for both groups following the benefit period returned approximately to their expected level based on pre-application employment income trends

However, available data do not allow analysis of the potential effect on family savings or debt levels, which may be significant for both groups.

In the year of application, both recipients and non-recipients experienced a drop in their total employment earnings from pre-application levels—likely related to a need to provide care to the critically ill or injured child in their application for benefits and a reduction in working hours.

- The impact period is both the year of application and the following year, as the benefit period seldom is contained in a single calendar year and would affect earnings in both years as a result

Compared to projected employment earnings based on observed pre-application levels, recipients experienced a 21% drop (-$16,350) over the event period, while non-recipients had a smaller reduction of 9% (-$5,600)

- Parents who provided care for a critically ill or injured child older than 1 year old received an average amount of $9,570 in benefits, thus substituting about 59% of their earning loss

Text description of Figure 5

| Calendar Year (t is the year of application) | Average Employment Earnings | Projected Employment Earnings |

|---|---|---|

| t-4 | $34,753 | n/a |

| t-3 | $35,051 | n/a |

| t-2 | $36,270 | n/a |

| t-1 | $37,741 | $37,741 |

| t | $28,564 | $38,559 |

| t+1 | $33,037 | $39,395 |

| t+2 | $39,641 | $40,249 |

Text description of Figure 6

| Calendar Year (t is the year of application) | Average Employment Earnings | Projected Employment Earnings |

|---|---|---|

| t-4 | $27,173 | n/a |

| t-3 | $27,583 | n/a |

| t-2 | $29,133 | n/a |

| t-1 | $28,342 | $28,342 |

| t | $24,468 | $29,352 |

| t+1 | $29,682 | $30,398 |

| t+2 | $32,547 | $31,482 |

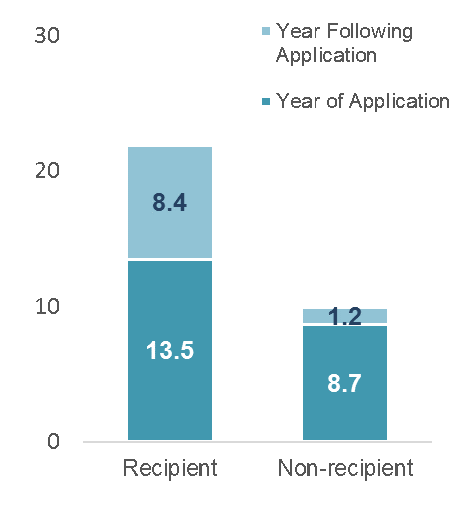

Given the reduction in annual employment earnings below projected levels, the benefit enabled recipients to take, on average, an equivalent of 12 weeks of additional leave compared to non-recipients.

- This assumes that the projected earnings (see figure 5 and figure 6) would have been equally distributed across a 52-week period.

This was particularly pronounced further out from the application.

- While the gap in equivalent weeks of reduced employment income was approximately 5 weeks in the year of application rose to more than 7 weeks in the calendar year following application.

Text description of Figure 7

| Type of applicant | Year of application (in weeks) | Year following application (in weeks) | Total (in weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient | 13.5 | 8.4 | 21.9 |

| Non-recipient | 8.7 | 1.2 | 9.9 |

Some social workers highlighted during the interviews that single parent families faced even greater financial difficulty because the sole parent usually had to stop or reduce work for a period to care for their critically ill or injured child.

- In some cases, non-PCIC recipients were referred to social assistance programs such as Ontario Works or to charitable organizations

In 2-parent families, social workers did not often see both parents taking leave.

- Both parents tended to be present when a child was in an acute phase that turned fatal, or had suffered severe trauma as a result of an accident

Overall, the temporary income support appears to be structured in a way that it was adequate to meet the needs of parents eligible to receive the benefit.

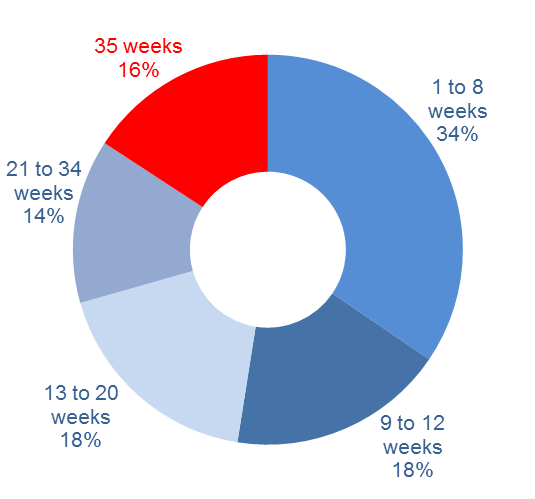

Based on administrative data, just over half of recipients (52%) required up to 12 weeks of EI benefits while 16% used all 35 weeks as shown in figure 8.

Text description of Figure 8

| Average number of weeks of EI benefits | Percentage |

|---|---|

| 1 to 8 weeks | 34% |

| 9 to 12 weeks | 18% |

| 13 to 20 weeks | 18% |

| 21 to 34 weeks | 14% |

| 35 weeks | 16% |

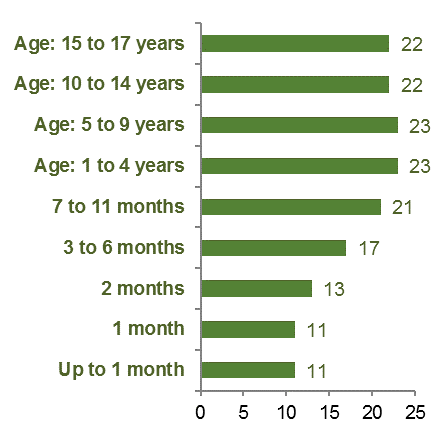

Figure 9 shows that the age of child affected the duration of benefits.

- Recipients with a child older than 1 year old spent on average 22 to 23 weeks to provide care to their critically ill or injured child

- For parents who provided care to a critically ill child under 1 year old, they required a shorter period, between 11 to 21 weeks, and therefore received a lower average amount of $5,600 in EI benefits (PCIC, maternity, parental and EI regular benefits)

- In some cases, recipients would end the PCIC benefit early in order to return to other EI benefits, particularly for maternity benefit which can only be claimed within the 17 weeks following the birth of a child, unless the child was hospitalized

Without feedback from parents, it is unclear how many weeks they were able to take leave from work beyond the weeks in receipt of the benefit (as prescribed by a medical specialist).

Text description of Figure 9

| Age of critically ill or injured child | Average duration in weeks of care |

|---|---|

| Up to 1 month | 11 |

| 1 month | 11 |

| 2 months | 13 |

| 3 to 6 months | 17 |

| 7 to 11 months | 21 |

| 1 to 4 years | 23 |

| 5 to 9 years | 23 |

| 10 to 14 years | 22 |

| 15 to 17 years | 22 |

Key Finding #3

The benefit also had noticeable non-financial impacts and effects on the personal lives of recipients.

Parents’ psychological well-being

Several studies and interviews with social workers indicated that finding out that their child was critically ill and providing care during sometimes long periods, were sources of continuous emotional strain and stress for parents.

- Parents experienced a wide range of emotions, including fear, uncertainty, guilt and grief, and accumulated symptoms of Acute Stress Disorder

- Sleep deprivation and sleep quality also affect parents’ psychological well-being

“…for many of them it is a non-stop job. A lot of parents don’t have access to consistent nursing. They are terrified, it takes one or two errors before a parent loses their trust in anybody looking after their child. (…) Some children are stable for a while then something happens, it’s a roller-coaster for months.” (Hospital Social Worker)

Many interviewees noted that parents with more than one child experienced additional pressures.

- The reliance on extended family or friends to care for their children in or outside of their homes was more frequent

- Siblings of the critically ill or injured child “struggled” throughout this process, and suffered emotionally from the lack of parents’ attention

“They wouldn’t be able to provide the same level of care to their child, wouldn’t be able to see their kid if they didn’t have this program to access. It was huge for every family that I spoke with”. (Charity Social Worker)

During this critical life event, parents often faced significant challenges in their personal lives ranging from relocation and family separation to sometimes a loss of relationships.

- Administrative data shows a higher number of divorces or separations during or immediately following this life event, which could be due in part to the increased emotional strain and pressures

Within the impact analysis, there was a reduction in the divorce or separation rate among recipients compared to non-recipients. This reduction was statistically significant (see Annex C for methodology).

- The divorce or separation rate was reduced by 2.8%, perhaps due in part to, in addition to other factors—the reduced financial stress and increased flexibility to take leave for caregiving responsibilities

Key Finding #4

The benefit helped keep claimants attached to the labour force, but the gradual alignment of provincial and territorial employment standards may have reduced their time on leave or created a barrier to access the benefit

Within the impact analysis, recipients had a 3.6% higher probability of returning to a job in the short-run compared to non-recipients.

- Both men and women were more likely to return to work if they received the benefit

- Nearly 84% of recipients returned to work in the year following a period of leave of absence from work, regardless of the age of the child

- Among those that returned to work during the application year, 20% of non-claimants reporting on their application that they would not return to the same employer, compared to only 6% of claimants

Administrative data shows that returns to work were higher among recipients.

- 90.9% of male recipients returned to work compared to 86.2% of male non-recipients

- 82.6% of female recipients returned to work compared to 81.3% of female non-recipients

The decision to leave or to return to work depended on the employers' top-up programs.

- Some employers provided a full salary during the one-week waiting period, while others covered 70% to 100% of salary for the first 6 weeks as part of their short-term disability plan, most commonly for recovery from childbirth. In these situations, mothers of critically ill children believed that they did not need and/or were not eligible to apply for the benefit

- Others relied on provincial or territorial employment standards to provide a minimum period of unpaid leave to allow parents to take time away from work

Alignment of employment standards at all levels of government—federal, provincial and territorial—as they pertain to statutory leaves, was seen as another factor that affected the uptake of the benefit.

- Outside of federally-regulated industries, job protection is subject to provincial and territorial employment standards or to specific collective bargaining agreements

- Four provinces gradually amended their legislation within two years following the introduction of the benefit, with most following thereafter (as recently as 2018 for Alberta)

- British Colombia, Nunavut and Northwest Territories do not have a leave related to critical illness of a child

Key Finding #5

Slower-than-usual speed of pay for the benefit was likely related to difficulties with submitting and/or processing appropriate medical certificates.

According to Service Canada processing agents, the first benefit payment for a claim was often issued beyond the Department's service standard of 28 calendar days, particularly in the early implementation stages, due to incomplete applications and shortage of resources.

- The decision on the claim was usually made within the 28-day period and a notification letter of approval was sent to applicants

- Delays happened when required documents were not provided or key information were missing causing payments to be issued 2 weeks beyond the 28th day

- Parents of critically ill or injured children living in remote areas experienced the highest delays since they were required to travel to see a specialist doctor

Several factors could further add to processing delays, including:

- overall increased non-PCIC claim volume in the same period

- increased complexity for situations where PCIC was combined with other EI-related benefits

- lack of completeness of claimants' and employers' information such as medical certificates and record of employments, and

- Service Canada employees limited training

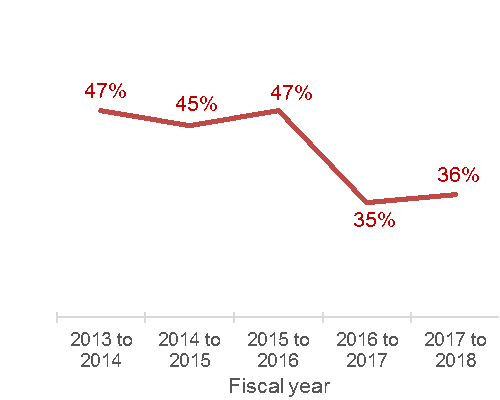

Administrative data shows that fewer than half of first payments issued were within 4 weeks of application.

- As such, the majority of parents went at least 4 weeks between application and receipt of benefits.

- Data from the Manual Pay System indicates that around 1 out of 6 claims had processing times that went beyond 8 weeks.

- The administrative data do not indicate the reasons for the delays or why it was lower in later years.

Text description of Figure 10

| Year | Percentage of claims receiving benefits within 28 days of application |

|---|---|

| 2013 to 2014 | 47% |

| 2014 to 2015 | 45% |

| 2015 to 2016 | 47% |

| 2016 to 2017 | 35% |

| 2017 to 2018 | 36% |

Key Finding #6

The Manual Pay System, through which the benefit was administered, limited tracking and reporting functions for claimants and for the Department.

Information stored in the Manual Pay System prevented parents of critically ill or injured children to access their applications through their My Service Canada Account.

- My Service Canada Account was designed as a single point of access and online services for users to view and update their information for Employment Insurance, Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security benefits

This limitation was a source of frustration among recipients who called to inquire about the status of their payments.

“(…) once they (parents) are in the MPS [Manual Pay System], they stay in the MPS. To me, that's the worst with these benefits and continues to be”. (Service Canada agent)

Moreover, the Manual Pay System creates challenges within the Department from both a policy development, performance measurement and an evaluation perspective. The data are not easily accessible or comparable with other EI administrative data and introduces reliability issues.

Acknowledging that reporting for performance measurement and evaluation is not the primary purpose of the Manual Pay System, the following issues were identified in the development of the evaluation report:

- there were persistent problems in defining the combinations of PCIC benefit with other EI related benefits

- challenges to recover accurate PCIC-related information in the Manual Pay System, which significantly affected the ability to conduct financial estimates for the program

- about 4% of all PCIC payments were issued during the same week, according to the administrative data, affecting the accuracy of EI benefit duration estimates

- evaluators were unable to use information from the Computer Pay System (CPS) to find out why an application was rejected since the reason was missing in 71% of 4,100 rejected applications

- paper-based applications were not taken into account and it is unclear how many paper-based applications were rejected

4. Conclusions and recommendations

The overall report presents analysis and findings that demonstrate that the Parents of Critically Ill Children benefit was effective overall in meeting its policy objectives. The benefit:

- was effective in easing financial pressures on parents in order to allow them more time to provide care to their critically ill or injured child;

- provided adequate temporary income support;

- helped keep claimants attached to the labour force; and

- contributed to positive social impacts among PCIC recipients.

The evaluation identified areas of improvement related to targeted outreach efforts to increase the level of awareness and take-up of the benefit. It also noted evidence that signalled the need for greater attention to the tracking and reporting functions for claimants and for the Department.

In December 2017, the EI Family Caregiver Benefit for Children was implemented to take the place of the EI Parents of Critically Ill Children benefit. Like its predecessor, this benefit provides income support to eligible claimants who needed to be absent from work to provide care or support to a critically ill child. Moreover, it improved on the previous Parents of Critically Ill Children benefit by:

- no longer restricting the benefit to parents of the critically ill child

- eligibility was expanded to any eligible family member who is providing care or support to the child, and the benefit can be shared among claimants providing care and support

- the required medical certificate can be completed by a medical doctor or a nurse practitioner, and

- if more than one child is critically ill as a result of the same event, up to 35 weeks of benefits can be paid for each child

These modifications to the design parameters are having a positive impact on client service to Canadian families. Speed of Pay for Family Caregiver Benefits (both for children and for adults) is currently within the standard processing timeframe of 28 calendar days.

As such, the Evaluation Directorate offers the following recommendations to improve the EI Family Caregiver Benefit for Children:

Recommendation 1:

Seek to increase the level of awareness and understanding of the EI Family Caregiver Benefit for Children following its December 2017 launch.

Recommendation 2:

Explore the feasibility of migrating the administration of the EI Family Caregiver Benefit for Children from the Manual Pay System for applicants in order to allow self-serve functionality for applicants.

5. Management response/action plan

The Department would like to thank the Evaluation Directorate for its work on the first program evaluation of the Employment Insurance Parents of Critically Ill Children (PCIC) benefit.

Preliminary analysis shared over the evaluation process helped inform policy analysis as well as outreach and communications activities over the course of 2017 and 2018.

Recommendation 1:

Seek to increase the level of awareness and understanding of the EI Family Caregiver Benefit for Children following its December 2017 launch.

Changes to make EI benefits for caregivers more flexible, inclusive and easier to access, came into effect on December 3, 2017. The PCIC was enhanced and renamed as the Family Caregiver Benefit for children. It continues to provide up to 35 weeks of benefits for the care or support of a critically ill or injured child, with expanded eligibility to include any family members, rather than only parents. Access to EI caregiving benefits has been enhanced by expanding the list of eligible health care professionals that may sign the medical certificate to include medical doctors and nurse practitioners. Caregivers can share the 35 weeks of benefits, either at the same time or one after another, and receive their benefits when most needed during a 52-week period.

Management agrees with this recommendation.

A proactive, national communications approach including digital and social media was adopted in launching the EI Family Caregiver benefit for children and adults in December 2017. Elements of this strategy included: communications products used for the launch and throughout 2018 including echo announcements, social media posts and videos on commemorative dates; updates to ESDC webpages; messaging to inform and assist staff at 1-800-O-Canada and Service Canada Centres and Members of Parliament.

In order to further increase the level of awareness of the benefit and understanding of the application process, the Department reviewed EI websites (EI Website Optimization project), including user experience testing so that information on EI benefits for caregivers is easy to find, written in plain language and meets the needs of our clients. The new websites were launched in August 2018. The Department will continue to track and analyze website metrics.

The EI Program will continue to raise awareness among the public and stakeholders of EI Caregiving benefits. Departmental social media platforms will be used to promote the benefit on specific commemorative dates, and other government departments will be encouraged to promote the benefit using their networks and communications activities.

Actions planned for recommendation 1

1.1 Employment Insurance benefits for caregivers website optimization, which was completed in August 2018.

1.2 Develop Communications plan and materials (for example, website updates, social media, promoting EI benefits for caregivers at conferences and stakeholder events). The communications plan has an anticipated completion date of Spring 2019 while activities will be ongoing through March 31, 2020.

Recommendation 2:

Explore the feasibility of migrating the administration of the EI Family Caregiver Benefit for Children from the Manual Pay System for applicants in order to allow self-serve functionality for applicants.

Management agrees with the recommendation.

As of June 2019, it is expected that 55-60% of EI Family Caregiver Benefit for Children will be automated.

The following combinations will still require the manual pay system once the claim converts to the second type of benefits:

- family caregiver benefits combined with Maternity benefits

- family caregiver benefits combined with Parental benefits

- family caregiver benefits combined with Compassionate care benefits

Due to the complexity and options for combining benefits, further analysis is required to determine the feasibility of migrating additional combination benefit types within the computer pay system.

Actions planned for recommendation 2

2.1 System Implementation of the Family Caregiver Benefit for Children in the computer pay system, with an anticipated completion date of June 29, 2019

2.2 Prioritize which benefit type combinations will be assessed for migration into the computer pay system, with an anticipated completion date of December 31, 2019

6. Annexes

Annex A: Bibliography

External sources:

- Canadian Cancer Society. Canadian Cancer Statistics (June 2018). A 2018 special report on cancer incidence by stage.

- Chavoschi, N. et al. (2015), Mortality trends for pediatric life-threatening conditions, in American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine, Vol. 32(4), 464-469.

- Fell B. D. and Joseph KS (2012), Temporal trends in the frequency of twins and higher-order multiple births in Canada and the United States, in BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, Vol. 12(1), 103-110.

- Handouyahia, A, Stéphanie, R, Gingras, Y, Haddad, T and Awad, G. (2016). Estimating the Impact of Active Labour Market Programs using Administrative Data and Matching Methods. Proceedings of Statistics Canada Symposium 2016.

- Hunter, T. et al. (2018), Neonatal outcomes of preterm twins according of birth and presentation, in The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, Vol. 31(5), 682-688.

- Kiely L. J. (1990), The epidemiology of perinatal mortality in multiple births, in Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, Vol. 66(6), 618-637.

- Widger, K et al.(…). Pediatric palliative care in Canada in 2012: a cross-sectional descriptive study, in CMAJ Open, 4(4). E562-E568.

Internal and technical sources (available upon request):

- Archambault, J. (Forthcoming). Ebauche: rapport porté sur la méthodologie dans le cadre de l’Évaluation du programme parents d'enfants gravement maladies.

- Key Information Interviews Report (2018) as part of the Evaluation of the Parents of Critically Ill Children Benefit.

Data sources:

- Canada Revenue Agency tax file data. Data are based on a 10% sample covering the years from 2010 to 2016.

- Employment and Social Development Canada. EI administrative data. Data are based on a 10% sample covering the years from 2015 to 2018.

- Statistics Canada. Table: 13-10-0425-01 (formerly CANSIM 102-4512). Live births by less than 37 weeks of gestation and by place of residence of the mother.

Annex B: Evaluation approach

The evaluation looks at the PCIC benefit program from its inception in early June 2013 to early December 2017 when it was replaced by the program for Family Caregiver Benefit for Children.

Lines of evidence

Quantitative lines of evidence were developed using Departmental administrative data and Canada Revenue Agency tax records to obtain income earnings data. Tax records with personal information were masked to ensure privacy and confidentiality. They were linked to the electronic applications via Appliweb and to the Department’s EI Administrative Database Status Vector file (SV) to produce information that was used to analyse the impacts of the PCIC benefit on recipients and non-recipients.

Where appropriate, these lines of evidence were enriched with other external sources of data and relevant literature to provide context to the analysis.

Key Informant Interviews provided an important source qualitative evidence. Interviews started in May 2018 with 20 representatives from hospitals and charities, and with 5 Service Canada processing agents at the Center of Specialization in Sudbury, for a total of 25 participants. Interviews were completed in June 2018.

Evaluation considerations

- The comparison between recipients and non-recipients requires that the use of the variable entitled “date of application”. The Benefit Period Commencement (BPC) provides a better approximation of the date of the child illness or injury but is unavailable for non-recipients.

- Canada Revenue Agency data are only available until 2016 which limited the impact analysis to the first years of PCIC.

- Paper-based applications were not taken into account because they were not available. Hence, evaluators were unable to estimate the number of paper-based applications that were rejected.

- Administrative cost information to estimate the level of resources associated with this benefit was deemed to be difficult to isolate from financial sources.

- Due to the highly personal and emotional circumstances surrounding the benefit, interviews with parents and guardians were not undertaken for this evaluation.

Annex C: Impact methodology

Population

In order to assess the impact of PCIC, the evaluation refers to parents who received the PCIC benefit as the treatment group. For parents who did not receive the benefit because they did not meet all eligibility requirements, the evaluation refers them as non-recipients as the control group. The comparison is strictly limited to these 2 groups.

The impact analysis excludes applicants who had a critically ill child less than 1 year old. While this decreases the number of observations to about 4,800 from over 15,000, it is done to minimize entangling the impact of the PCIC benefit with the effects of the EI maternity and parental.

On average, recipients who had a critically ill child 1-year old or older were more educated (25% had a university degree compared to 20% of non-recipients), were generally older than non-recipients, had higher employment earnings prior to application, and were more likely to be a woman. The impact analysis uses propensity score matching to adjust for these differences in the populations and get a more accurate analysis of the impact

Propensity Scoring

In order to improve the comparability between the 2 groups of claimants, this evaluation uses propensity score model to weight observations across groups. This model has been peer-reviewed and the variable that were used to match both groups are: year of applications, age of child, age of parent, gender of parent, number of child, level of education, province, union status, minority status, lag income (3 year before).

Data limitations

Propensity scoring helps to get at the attributable impact of the benefit, it is limited to what can be observed in the anonymized administrative data.

Most notably, the severity of the illness of the child can reasonably be assumed to play an important role in the duration of care and, additionally, access to other supports such as receiving guidance from a hospital social worker.

While it might be reasonable to expect that parents who did not receive the benefit due to a lesser degree of severity of the illness or injury in general (and therefore facing greater difficulty in obtaining a medical certificate) would have more moderate negative effects, this is by no means certain or provable with the administrative data.

Annex D: Health-related data

| Provinces and Territories | Number PCIC claims by parents with a child under one-year of age | Percentage of PCIC claims by parents with a child under one-year of age |

|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 176 | 1.2% |

| Prince Edward Island | 78 | 0.5% |

| Nova Scotia | 327 | 2.1% |

| New Brunswick | 338 | 2.2% |

| Quebec | 3,391 | 22.2% |

| Ontario | 5,651 | 36.9% |

| Manitoba | 561 | 3.7% |

| Saskatchewan | 570 | 3.7% |

| Alberta | 2,181 | 14.3% |

| British Columbia | 1,980 | 12.9% |

| Yukon | 22 | 0.1% |

| Northwest Territories and Nunavut | 27 | 0.2% |

Source: Administrative Database: Manual Pay System

| Provinces and Territories | Number of pre-term live births babies | Ratio of PCIC claims per 1 000 pre-term live births babies |

|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1,693 | 104 |

| Prince Edward Island | 481 | 162 |

| Nova Scotia | 3,067 | 107 |

| New Brunswick | 2,411 | 140 |

| Quebec | 27,435 | 124 |

| Ontario | 49,047 | 115 |

| Manitoba | 6,402 | 88 |

| Saskatchewan | 5,319 | 107 |

| Alberta | 21,379 | 102 |

| British Columbia | 15,570 | 127 |

| Yukon | 121 | 183 |

| Northwest Territories and Nunavut | 740 | 36 |

| Canada | 133,661 | 114 |

Source: Statistics Canada. Table: 13-10-0425-01 (formerly CANSIM 102-4512). Live births by less than 37 weeks of gestation and by place of residence of the mother.

Annex E: Health-related data, estimation methodology

- Non-trauma life-threatening conditions (LTC), and

- Trauma related conditions such as injuries and accidents

Based on estimates for British Columbia, the evaluation extrapolated this estimation to include the whole population of children up to 18 years of age in Canada for non-trauma LTC. As such, the number of non-trauma LTC is between 3,900 and 7,260.

Though the number of hospitalizations for critical injuries that can put a child’s life at risk could not be established easily, the evaluation suggests using 23,000 injuries that were reported in 2012 to 2013 for children up to 19 years of age. It is understood that life-threatening conditions vary from acute end-of-life situations where a death may occur rapidly or slowly due to progressive diseases with a life expectancy into the teens or 20s.

Sources: Widger, K et al.(…). Pediatric palliative care in Canada in 2012: a cross-sectional descriptive study, in CMAJ Open, 4(4) E562-E568

Chavoschi, N. et al. (2015), Mortality trends for pediatric life-threatening conditions, in American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine, Vol. 32(4), 464-469.