Summative Evaluation: Understanding the Early Years Initiative, September 2011

Official Title: Summative Evaluation of the Understanding the Early Years Initiative - September 2011

List of Abbreviations

- CDPD Community Development and Partners Directorate

- ECD Early Childhood Development

- EDI Early Development Instrument

- HRSDC Human Resources and Skills Development Canada

- PIDACS Parent Interviews and Direct Assessment of Children Survey

- UEY Understanding the Early Years

Executive Summary

Background

Human Resources and Skills Development Canada’s (HRSDC’s) Understanding the Early Years (UEY) Initiative aimed to enhance communities’ capacity to support young children and their families. This was to be accomplished by developing and using quality local information to foster community mobilization and to make informed, collective decisions on concrete actions to enhance children’s lives as well as building on the strengths of existing local approaches to support young children and their families. The objectives of the evaluation were to assess the impacts of the UEY Initiative in participating communities and to identify lessons learned using the UEY model.

The UEY Initiative was based on the following guiding principles: Footnote 1

- A good start in the early years of life enhances children’s well-being and lays the foundation for learning, behaviour and health as they grow;

- A child’s family and community are key influences on the child’s development and overall well-being;

- Research and knowledge are critical to the development of informed policies, programs and service delivery approaches that can enhance early childhood development outcomes; and

- Communities can mobilize their citizens and resources to find creative and effective ways to address challenges facing their young children and their families.

The primary objective of the Initiative was to enable community members to work together to address the needs of young children aged six years and under by:

- Enhancing family and community understanding about the importance of young children’s development and approaches to help children thrive; and

- Strengthening their ability to use local data to help them make decisions to enhance children’s lives. Footnote 2

Evaluation Strategy

The evaluation integrated results from six lines of evidence:

- Literature review;

- Document and file review;

- Key informant interviews with federal and provincial officials;

- Survey of UEY project team members;

- Survey of coalition members; and

- Case studies.

The evaluation findings include data from all 36 UEY projects through the document and file review. Twenty-one community projects ran from 2005 to 2008 and fifteen projects operated over the 2007 to 2010 period. Data from the survey of UEY team members, survey of coalition members and case studies were collected for 18 of the 36 UEY projects (50%). Of these eighteen projects, eight were funded in 2005 and ten in 2007. In addition to the 18 participating UEY sites, information was collected on one pilot UEY project to explore sustainability of the UEY Initiative. The case studies involved a document review, site visits and individual or group interviews with a total of 35 key informant interviewees. Twelve key informant interviews with federal and provincial officials and a literature review were also completed.

Limitations

As with any evaluation there were challenges encountered in implementing the methodologies for the UEY evaluation. These resulted in the following limitations to the findings and conclusions of this evaluation:

Lower than expected response rates in surveys and case studies, despite multiple solicitations. Possible explanations for low response rate include elapsed time since the end of the 2005 projects and data collection was conducted during the period when 2007 projects were nearing the end of the project, thus, wrapping up final project deliverables.

Possible bias in project reporting. The only line of evidence to include all UEY projects was the document and file review, which consisted of project self-reports to HRSDC as required under their funding agreements. The likelihood of their accuracy is enhanced because the reports would be circulated and therefore subject to quality control. However, the risk that the reports highlight successes and give less attention to challenges may exist.

Challenges in attribution of results to UEY . As identified throughout the report, for several of the expected outcomes, programs other than the UEY Initiative with similar objectives for early childhood development were also operating in some areas of Canada. As would be expected when evaluating the impact of projects with complex interactions with other activities and people in the community, it is difficult to attribute the observed results solely to UEY.

Findings

Evaluation findings were synthesized across the lines of evidence and across evaluation questions into three main issue areas: relevance, performance and lessons learned.

Relevance

The evaluation evidence suggests that the UEY Initiative was relevant to the needs of communities working to improve life chances for their young children, and that the Initiative was very much in keeping with federal government, HRSDC and provincial government policies and programming related to early childhood development. The UEY Initiative was conceived at a time when several converging factors created an ideal environment for the demonstration of federal leadership in an area that was cresting in terms of interest in other jurisdictions. There was demonstrable need for the contributions the Initiative offered within the many community coalitions working to improve early child development in their communities, at least sufficient to warrant the level of financial commitment established for the UEY Initiative. In addition, at the time it was implemented, UEY was highly relevant to federal objectives and roles. The evidence suggests that the UEY Initiative contributed to a broadening of efforts in early childhood development in Canada in the mid-2000s, catalyzing actions and drawing research into decision-making.

The evaluation found that the objectives of UEY fit well under the strategic outcome “Income security, access to opportunities and well-being for individuals, families and communities”. In addition, the UEY Initiative is in keeping with, and complements, a broader set of HRSDC and other federal government Initiatives targeting the well-being of young children. Building knowledge and gathering information were seen as appropriate roles for the federal government, as these activities brought a national perspective on early childhood development issues and in the use of standardized data collection instruments.

Performance

Through the UEY Initiative, participating communities produced research and community mapping reports, conducted planning sessions based on the research findings, and developed Action Plans. The evaluation results suggested that this contributed to: better understanding among community members of the experiences of Canadian children in their early years; participating communities addressing the needs of children age six and under; and communities making informed decisions that stand to benefit the lives of young children. The Initiative may also have contributed to the development of inclusive communities. The evaluation provided many examples of how the UEY research process and results have been used to inform the development of, and garner support for, changes in policies, programs and services for children and families.

The findings suggest that UEY communities have laid some groundwork for ongoing efforts to address child development. Most have established extensive partnerships with community organizations and individuals, and strengthened linkages with provincial and municipal governments and school boards. Decision-makers in health and social service institutions and various levels of government reportedly value and are using the data that the UEY Initiative has produced. In some cases, bodies other than UEY coalitions have adopted a new research-oriented approach to planning based on the UEY model. Moreover, the evaluation findings suggest that after the UEY funding ended, many participating communities continued to partner and build networks to address early childhood development issues, and transfer knowledge to address early childhood development issues. Overall, the evaluation evidence suggests that UEY efforts are being sustained, at least to some degree, as communities commit to move forward with implementing their Action Plans and in trying to find other resources to support their efforts.

The evaluation findings suggest that through its activities, the UEY Initiative was supportive of building community capacity to better address early childhood issues. The UEY approach built on community-level collaboration and partnerships to help develop a collective response to early childhood needs. The networks of dedicated people, the combination of national instruments and community level data and the sharing of information and tools among communities were seen as especially valuable. The Initiative made an important contribution to increasing awareness of the importance of early childhood development within communities, as well as provincial governments. Key elements of the UEY approach – in particular the Early Development Instrument (EDI) and mapping approaches to understanding communities – have become, or are becoming, institutionalized in many jurisdictions, which although not attributable solely to UEY, this illustrates UEY’s convergence of interests with those of the provinces around early childhood development (ECD) in the last decade.

Lessons Learned and Transferability of the UEY Approach

Valuable lessons were learned by communities through the UEY Initiative about the use of research to inform the development of community programs and services. The UEY Initiative’s community research component was seen as having provided a unique and highly valuable contribution, providing an example of how data on the state of children’s development could inform community-level understanding, attitudes, and actions, and contribute to addressing areas of identified need. An additional lesson learned was that given the complexities and scope of the research component, and in order to maximise the benefits of the major investment in community-level research, a longer funding time frame and ensuring transition toward effective implementation of the Action Plan would have been beneficial.

The great majority of those who participated in the evaluation, including government and a range of community respondents believed that that the UEY approach is transferable to other populations and issues. The data suggest that successful transfer would necessitate a full alignment with provincial orientations and investment priorities.

Overall Conclusion

While some of the results of this evaluation cannot be extrapolated to the full set of 36 UEY given the response rate, the findings suggest that the UEY Initiative contributed to the achievement of its expected longer term outcome: progress toward inclusive communities that are responsive to the needs of children and families. The unique contribution made by UEY is harder to ascertain, as UEY contributions were closely linked to ongoing increasing prioritization and investment in children’s early years, especially in some provinces. There is nonetheless evidence to suggest that UEY contributed to, supported and in some cases catalyzed actions that should benefit children’s developmental outcomes. The evaluation shows the value of the research component of the UEY Initiative in generating and building knowledge in the area of early childhood development for communities and governments. This approach may have applicability for other areas that require local solutions to complex social issues.

Management Response

Introduction

The Understanding the Early Years (UEY) Initiative summative evaluation was designed to examine issues related to the relevance and performance of the Initiative, as well as lessons learned and transferability of the UEY model. This model used community research as a tool to stimulate and inform community action and investments.

The Community Development and Partnerships Directorate (CDPD) within the Income Security and Social Development Branch had responsibility for the UEY Initiative. The evaluation identified lessons learned with respect to the design and performance of the Initiative. These lessons learned as outlined in the evaluation report, and the experience of those closely involved in the UEY Initiative, can be used to inform subsequent policy and program design that involves working with communities to find solutions locally for groups facing complex and continuous social challenges. These lessons can be applied to the work the Government of Canada is planning to undertake to complement community efforts to address social issues by encouraging the development of government/community partnerships as announced in Budget 2011.

Lessons Learned

The community research component was a unique and highly valuable tool to inform and engage community understanding and involvement. However, given the complexities and scope of the research a longer funding time frame and ensuring transition to implementation of the Action Plan would have been beneficial

CDPD management acknowledges the importance that the UEY Initiative’s research component played in enabling communities to generate reliable local evidence related to early childhood development, and upon which to base decisions about local approaches to address the issues identified. Participants in the evaluation indicated that the data collected from each UEY project’s two sets of data collections (i.e. the Early Development Instrument and the Parent Interviews and Direct Assessment of Children Survey) were the most valuable aspect of the Initiative, because these data generated local information that could be used to influence attitudes and understanding in the community. The information forged new partnerships within the communities and influenced changes in public policy and delivery of services related to early childhood development. For example, several of the provinces and territories have adopted the Early Childhood Development Instrument for use throughout their jurisdictions, with others exploring province-wide or territory-wide coverage in the future.

The information obtained from UEY projects’ two sets of data collections has been of particular importance and value to each of the communities that participated in the Initiative. In the effort to share the research findings of the UEY projects more broadly, the Community Research Reports for each UEY project have been posted on HRSDC’s website. It is recognized that more consideration could have been given at the planning stages as to how the community data sets would continue to be used to inform future policy analysis, both at the community and national level.

As pointed out in the evaluation report and by project participants who participated in the “UEY Legacy Forum” in March 2010 Footnote 3 , projects that involve mobilizing partnerships centred around research require sufficient time and ideally would be funded for a minimum of four or five years. In addition, it was suggested that sustainability of the projects should have been considered by all partners from the beginning and that governments need to work together to facilitate effective complementary policy development and funding.

In applying these lessons learned to the current Social Partnerships work being done by the Department, recognition also needs to be given to the fact that programs must be informed by reliable and attainable evidence that is relevant for the specific user, which in many cases is at the local or community level. There is a role for the federal government in supporting the collection of data, especially in the case of multiple communities doing similar research given the economies of scale and the benefit of using standardized instruments.

Value of facilitating partnerships and opportunities for information sharing

As indicated above, the summative evaluation report’s findings indicated that the UEY Initiative facilitated partnerships and opportunities for information sharing at the local level. The experience of CDPD project staff has also indicated that the Initiative provided the opportunity for the UEY projects to do this at the regional and national level as well. Many of the UEY projects, particularly those in British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Nova Scotia, forged successful partnerships, which allowed for significant exchanges of information and knowledge. For example, businesses in many UEY communities began to understand that healthy families and children had an impact on the economic success of communities and provided in-kind and cash resources to support the projects. For example, in one community, a school bus was donated and outfitted to respond to the need for a mobile “hub” to service families living in outlying areas. As a result, UEY projects from a particular region often provided a regional analysis or perspective on the status of children and families in the communities comprising their respective projects.

Throughout the duration of the Initiative, UEY project members were brought together in Ottawa to undertake training on various aspects of the project, such as use of survey instruments, community-mapping software, or preparation of research reports. These meetings often led to significant and invaluable information-sharing opportunities between the UEY projects. Furthermore, the “UEY Legacy Forum” also provided a valuable opportunity for participants to meet face-to-face to share key factors that contributed to the success of their projects and to discuss how aspects of the community-mobilization approach could inform policy and program development to address issues other than early childhood development. One of the key messages reiterated by the forum participants was that the position of the UEY community coordinator, which was supported by HRSDC’s project funding, was invaluable as they were the liaison with the community and were essential in facilitating partnerships and enabling the data collection. Future community-based social partnership supported by HRSDC need to continue to recognize that successful outcomes are linked to supporting local capacity.

Similar to the current Social Partnerships approach being examined, where local partners are actively engaged, the UEY Initiative recognized the importance of a community coalition in mobilizing the community, both in terms of identifying their needs through active participation in the data-collection phase and in developing the Community Action Plan. Through their shared values of recognizing the importance of early childhood development, the coalition was able to leverage support at the community level. In moving forward, it is important to acknowledge that community coalitions need financial and in-kind supports from various partners if they are to be successful.

In conclusion, the UEY Initiative demonstrates that solutions to local social challenges can be addressed by equipping community partners with relevant evidence with which to fully understand the issue. This information can catalyze communities and build on existing partnerships and can foster new linkages which can lead to action. In addition, building effective social partnerships also takes time upfront to effectively plan, carefully consider the longer-term outcomes, and evaluate.

1. Introduction

1.1 Evaluation purpose and context

Human Resources and Skills Development Canada’s (HRSDC’s) Understanding the Early Years (UEY) Initiative aimed to enhance communities’ capacity to support young children and their families. This was to be accomplished by developing and using quality local information to foster community mobilization and to make informed, collective decisions on concrete actions to enhance children’s lives as well as building on the strengths of existing local approaches to support young children and their families. The objectives of the evaluation were to assess the impacts of the UEY Initiative in participating communities and to identify lessons learned using the UEY model. The evaluation addressed the UEY Initiative’s:

- relevance: the extent to which the Initiative addressed a demonstrable need, was appropriate to the federal government, and was responsive to the needs of Canadians;

- performance: the extent to which effectiveness and value were achieved by the Initiative and;

- lessons learned and transferability of the model: lessons that have been learned using the UEY model and the feasibility of using it elsewhere.

Drawing on the experiences of a number of government initiatives relating to early child development and the results of 12 UEY pilot projects, the UEY Initiative was implemented in 2004. In total, 36 projects were funded, 21 community projects ran from 2005 to 2008 and 15 projects operated over the 2007 to 2010 period. The focus of the summative evaluation is on the UEY Initiative and not the pilot projects.

The UEY Initiative, which ended in March 2011, used a distinct approach for achieving community-level impacts. The evaluation is expected to contribute to an understanding of the importance of research to inform the development of community programs and services, to assess the impact of the Initiative in funded communities and to provide lessons learned for future programming of a similar nature.

2. Initiative Profile

2.1 Overview: Initiative Rationale and Project Selection

2.1.1 Rationale

The UEY Initiative was developed as a pilot research initiative from 1999 to 2007 to enhance knowledge of community factors that influence early childhood development. Based on the results of 12 pilot projects (five funded from 1999 - 2000 to 2005 - 2006 and seven funded from 2001 - 2002 to 2006 - 2007), the seven-year national UEY Initiative was implemented starting in 2004. Twenty-one community projects ran from 2005 to 2008 and a further fifteen projects operated during the 2007 to 2010 period.

The UEY Initiative was based on the following guiding principles: Footnote 4

- A good start in the early years of life enhances children’s well-being and lays the foundation for learning, behaviour and health as they grow;

- A child’s family and community are key influences on the child’s development and overall well-being;

- Research and knowledge are critical to the development of informed policies, programs and service delivery approaches that can enhance early childhood development outcomes; and

- Communities can mobilize their citizens and resources to find creative and effective ways to address challenges facing their young children and their families.

The UEY objective was to enable community members to work together to address the needs of young children aged six years and under by:

- Enhancing family and community understanding about the importance of young children’s development and approaches to help children thrive; and

- Strengthening their ability to use local data to help them make decisions to enhance children’s lives. Footnote 5

2.1.2 Project Selection

UEY community projects were selected through a Call for Proposals process. Information and application forms and guides were disseminated mainly by Call for Proposals through on-line networks that link HRSDC and community organizations active in early childhood development. Applications then underwent a multi-stage review process. In a first, internal review, it was determined whether applications met the following set of mandatory eligibility criteria: Footnote 6

- The applicant organization was a legally incorporated not-for-profit organization and was actively pursuing social development issues;

- The proposed community was place-based: located within a certain geographical location defined by boundaries understood by residents. The geography had to be continuous or contiguous, and people within these boundaries shared a sense of belonging and identify with all, or parts, of the geographic community;

- The proposed community had to have an existing community coalition with experience and a record of accomplishments in dealing with social issues, such as early childhood education, homelessness or poverty. It was intended that each community project would involve the participation of parents, teachers, schools, school boards, community organizations and others interested in the well-being of children;

- Applicants were required to identify (in advance) all local schools/school boards (or their equivalent) that were willing to participate;

- Within the community, there had to have been suitable potential candidates (with appropriate skill sets and leadership qualities) for the UEY position of community coordinator;

- The proposed community was required to have at least 300 five-year old children entering senior kindergarten (or equivalent) in the upcoming school year.

Applications were then subject to an internal review by regional and national HRSDC staff using a structured scoring grid Footnote 7 , and then to an external review by provincial government officials.

There were a total of 36 successful applicants selected during the 2005 and 2006 Call for Proposals. Thirty-five proposals were received in response to the 2005 Call for Proposals, of which 21 (60%) were funded. In 2006, the Call for Proposals resulted in 31 proposals being received, of which 15 (48%) were funded.

UEY communities selected for funding included both urban and rural communities that were home to children from diverse cultural, linguistic and economic backgrounds, including First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, and children in immigrant families and low-income families. Table 1 summarizes the number of UEY projects funded by region and setting in 2005 and 2007.

| Funding in Region and Setting | Number of projects funded in 2005 | Number of projects funded in 2007 |

|---|---|---|

| Region | ||

| BC | 6 | 6 |

| Prairies (AB, SK, MB) | 2 | 5 |

| Central (ON, QC) | 9 | 2 |

| Atlantic (NB, NS) | 4 | 2 |

| Setting | ||

| Rural | 4 | 4 |

| Urban | 9 | 5 |

| Mixed | 8 | 6 |

| Total | 21 | 15 |

2.2 Initiative Resources and Activities

2.2.1 Resources

UEY Initiative resources

The 2004 federal budget set aside $68 million ($34.5 million in operating funds, and $33.5 million in contribution funding) over seven years for the UEY Initiative. UEY provided Contribution Agreement funding and was managed centrally within HRSDC. The operating funds for UEY included funding to undertake the research component and funds for staff to administer the program.

The September 2006 Expenditure Review reduced the Initiative’s original budget to $45.3 million ($23.9 million for operating and $21.4 million for contributions). A subsequent financial decision in late 2007 reduced the budget to $39.8 million ($23.4 million in operating funds and $16.4 million in contribution funding).

Funds per community

The UEY Initiative provided three years of Contribution Agreement funding to recipient organizations, who hired a project coordinator to mobilize community partners and strengthen community coalitions by means of three activities of the UEY projects: 1) generating information; 2) building knowledge; and 3) enabling the community. UEY funds were used to pay for: Footnote 8

- Salary of the project coordinator and other project staff such as a researcher;

- Replacement costs for teachers who attended training sessions and for their time spent completing questionnaires;

- Data analysis costs and data collection costs for some projects;

- Non-salary costs such as utilities, materials, supplies, travel, insurance, rental of premises, leasing or purchasing of equipment and supplies, translation, costs of evaluations and assessments, performance monitoring and reporting costs, data collection and communications and;

- Knowledge transfer and community engagement activities.

Community-level activities

UEY Initiative activities were sequentially launched in three distinct phases:

Phase I: Generating information

Research was conducted by independent contractors and the local UEY project staff, using a set of tools and data collection methods that included: the Early Development Instrument (EDI) that measured the school readiness of kindergarten children prior to Grade 1; the Parent Interviews and Direct Assessments of Children Survey (PIDACS) which examined the relationship between the development of kindergarten children and various family and community factors that could influence that development (an adaptation of the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY) for community-level research); the inventory of Community Programs and Services and; community socioeconomic characteristics based on the 2001 and 2006 Canadian Censuses.

Phase II: Building knowledge

Information generation activities of Phase I led to the production of two main reports: a Community Research Report providing UEY community projects with the results of the PIDACS (and the EDI for the 2005 projects); and, a Community Mapping Report presenting EDI, inventory of community programs and services and Census data. Both the EDI and the PIDACS reports indicated areas of strength and gaps in the community.

Using these reports along with additional tools and resources provided to UEY projects, the UEY recipient organizations and co-ordinators then worked collaboratively with their community coalitions and other community members to create an evidence-based Community Action Plan. Community coalition members consisted of school board representatives, parents, officials from non-profit organizations and others interested in early childhood development issues. The purpose of the Action Plan was to build on community resources and strengths to address identified gaps in programs and services for young children and their families.

Phase III: Enabling the community

Strengthening of local networks and partnerships and the transfer of knowledge were important processes that enabled communities to develop and share UEY research and implement the Action Plans. To support these processes, UEY projects were provided with a resource to provide guidance in and dissemination of research findings out into the communities. Footnote 9 In addition, workshops in Ottawa were held to provide UEY communities with an opportunity to exchange information and knowledge and to share their experiences with respect to the project.

Monitoring and reporting

UEY projects provided monitoring data as required by Contribution Agreements, including the submission of quarterly Activity and Progress Reports based on templates provided by HRSDC, Footnote 10 and quarterly financial reports. HRSDC staff also completed forms that provided internal updates on project progress.

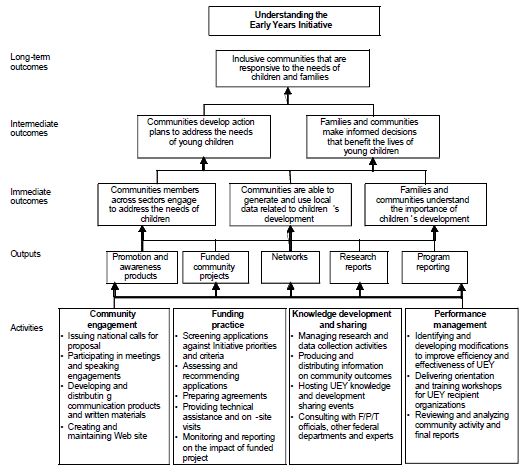

2.3 Logic Model

The logic model for the UEY Initiative demonstrates the intended relationships between the Initiative’s activities and its expected immediate, intermediate and long-term outcomes.

Logic model of the UEY Initiative Footnote 11

Text description of Figure 1 - Logic model of the UEY Initiative

UEY ACTIVITIES

The logic model identifies four major sets of activities directed at achieving the Initiative’s desired outcomes:

Community engagement: Community engagement involves all actions that seek to create awareness and engage communities in the UEY Initiative. Participation in meetings and speaking engagements, and development and distribution of communications products and written materials are ongoing activities. Issuing national calls for proposals includes responding to community inquiries.

Funding practice - Funding practice includes screening, review and assessment of submitted community proposals and recommending community projects for UEY funding. The UEY project cycle integrates administration of contribution agreements, finance and activity monitoring, and ongoing technical and on-site support to UEY communities.

Knowledge development and sharing - Knowledge development and sharing includes managing contracts for research and data collection, producing and distributing information on community outcomes and consultation with Service Canada, provincial/territorial officials and other departments and experts.

Performance management - Performance management activities involve identifying and developing modifications to improve efficiency and effectiveness of the UEY Initiative. The UEY project cycle includes delivery of orientation and training workshops for UEY communities and review and analysis of quarterly activity progress reports and final reports.

OUTPUTS

The identified outputs are HRSDC products resulting from ongoing activities undertaken by UEY management. These outputs are measured in five broad activity categories:

- Promotion and awareness products

- Funded community projects

- Networks

- Research reports

- Program reporting

EXPECTED OUTCOMES

Immediate Outcomes

Immediate outcomes are those expected results flowing from the actions and outputs undertaken by UEY management. Immediate outcomes for UEY are expected to occur within the first two years of the implementation of the national UEY Initiative.

Community members across sectors engage to address the needs of children

Child development is multi-faceted and, in order to successfully benefit children, a number of sectors need to be involved. UEY encourages the development of partnerships within and among different agencies and individuals in communities, allowing parents, service providers, educators and other community members to work together to best meet the needs of young children.

Communities are able to generate and use local data related to children’s development

The UEY Initiative is about helping communities generate and use multi-source data on the development of their young children, factors that influence early childhood development and the community’s resources. This will enable communities to see how the availability and distribution of community resources are linked to young children’s developmental outcomes and whether there are gaps in provision of services and programs to support young children and their families.

Families and communities understand the importance of children’s development

UEY allows communities to harness the information parents and communities have about early childhood development and to supplement it with new information. The Initiative encourages the sharing of this knowledge with all community members to enhance understanding of the importance of supporting the development and well-being of children.

Intermediate Outcomes

There are two intermediate outcomes, with expected results flowing from the immediate outcomes:

Communities develop action plans to address the needs of young children

Through UEY, parents and other community members will develop an understanding of how young children are doing and how the community is supporting them. UEY communities can then develop action plans, to propose concrete measures to address the community’s needs and problems identified by the UEY research.

Families and communities make informed decisions that benefit the lives of young children

Knowledge of factors that influence child development will enable families and communities to make informed decisions that benefit the lives of young children, and to participate in decisions related to community programs for young children.

Longer-Term Outcomes

Longer-term outcomes are the expected results flowing from the intermediate outcomes with the following longer-term outcome to be met:

Inclusive communities that are responsive to the needs of children and families

It is anticipated that the community action plans will lead communities to sustain the outcomes of their UEY project. Community engagement will have also been enhanced as a result of UEY participation.

3. Evaluation Methodology

3.1 Formative evaluation

A formative evaluation Footnote 12 of the UEY Initiative was completed in June 2009. It addressed the Initiative’s design and implementation, progress toward achieving objectives and accountability issues. This evaluation identified several potential operational improvements for UEY and guidance on the design of the summative evaluation.

3.2 Summative Evaluation Questions

The summative evaluation addressed the issues of relevance, performance and lessons learned. Appendix A sets out the evaluation matrix showing the evaluation issues and questions addressed by each method.

3.3 Data Sources and Collection Methods

The evaluation integrated results from six lines of evidence:

- Literature review;

- Document and file review;

- Key informant interviews with federal and provincial officials;

- Survey of UEY project team members;

- Survey of coalition members; and

- Case studies.

These research methods were undertaken between July and December 2010. The evaluation findings include data from all projects as collected through the document and file review. Semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted with key informants who were knowledgeable or had experience with early childhood programs. In addition, data from case studies, survey of UEY project team members and survey of UEY community coalition members was collected for 18 of the 36 UEY projects (50%). Of these eighteen projects, eight were from 2005 and ten were from 2007. In addition to the 18 participating UEY sites, information was collected on one pilot UEY project to explore sustainability of the UEY Initiative. The projects participating in the data collection covered all provinces, all types of project recipient organizations (school boards, non-profit agencies and other public sector agencies) and rural, mixed and urban settings.

3.3.1 Document and File Review

The review collected and synthesized relevant background documents, project files and pre-existing secondary data to provide evidence for some of the evaluation questions. The review examined available UEY and other federal government documents, and Initiative files that included reports from participating projects in the 2005 and 2006 Calls for Proposals. The review did not include projects undertaken in the pilot phases. The review was organized around the set of questions identified for the evaluation, and a set of pre-determined indicators for each question.

For information on the impacts of the UEY Initiative the document and file review relied heavily on project reports submitted by the recipient organizations in each community as part of their contribution agreement with HRSDC. These reports contained information about the activities undertaken in the communities, and the proponents’ assessments of what had been achieved.

Based on the project reports and the other supporting documentation, the review was able to identify findings in three areas: relevance, performance and lessons learned.

3.3.2 Updated Literature Review

This line of evidence was an update of the formative evaluation’s literature review. The literature review was aimed at providing current information on federal, provincial and territorial interest and funding for early childhood initiatives. It also updated research and evaluation findings of similar programs since the formative evaluation. Sources of information for the literature review included published national and international literature on early childhood development programs similar to the UEY Initiative.

3.3.3 Key Informant Interviews with Federal and Provincial Officials

The objective of the key informant interviews was to assess the relevance of the UEY Initiative’s alignment with HRSDC and federal government objectives, progress toward the achievement of intermediate and longer-term outcomes, lessons learned and transferability of the model.

Semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted with 12 key informants who were knowledgeable or had experience with early childhood programs, including six from three federal departments and six representatives from provincial governments. All had some knowledge of the UEY Initiative.

These qualitative data were analyzed using a matrix approach, where responses and evaluation questions were arrayed, and emerging themes were synthesized for each question.

3.3.4 Survey of UEY Community Project Team Members

The objective of the survey of community team members was to assess the progress toward the achievement of intermediate and long-term outcomes as well as the Initiative’s efficiency. The survey also collected information on the lessons learned and transferability of the UEY model to other populations and issues.

The survey population consisted of the main community project team members from 24 UEY sites that had not been invited to participate in the case studies. Each UEY site was considered to have three main project team members: the Executive Director of the UEY recipient organization, the UEY co-ordinator and the UEY researcher, with a total potential sample of 72 respondents. Eleven of the 24 projects ultimately participated in this survey, four of which were funded in 2005, and seven of which were funded in 2007. From the 11 participating UEY sites, 19 project team members completed the survey. Nine respondents represented 2005 funded projects and 10 represented 2007 funded projects.

To maximize the response rate, respondents were asked to complete a web survey followed by a telephone interview. The web survey was used to obtain factual information that required respondents to refer to documents to provide information. It also allowed respondents from the 2005 projects sufficient time to recall information dating back a few years. The subsequent telephone interviews allowed for further clarification or for obtaining more in-depth information than was provided in the web survey. Fifteen of the 19 community project team members who completed the web survey participated in the subsequent telephone interview. The survey was divided into two sections: project performance; and lessons learned and the transferability of the UEY project to other populations and social issues.

3.3.5 Survey of UEY Community Coalition Members

3.3.5.1 Sampling and Data Collection

The objective of the survey of community coalition members was to assess progress toward the achievement of intermediate and long-term outcomes, and to collect information on the lessons learned and transferability of the model to other populations and issues. The community coalitions consisted of groups of individuals and organizations working with the UEY project in the communities (e.g., parents, teachers, local businesses, and social or health service providers).

The survey population consisted of the coalition members of UEY sites not selected for case studies. Each project had 10 to 15 coalition members. In order to obtain contact information (i.e. names, mailing addresses, and telephone numbers) of the coalition members, UEY project Executive Directors were asked to contact their coalition members and obtain their agreement to participate in the evaluation. Of the 91 coalition members who agreed to participate, 61 interviews were completed. Evaluators were not able to reach the remaining contacts. The successful survey interviews included 32 from projects funded in 2005 and 29 from 2007. The 61 completed surveys represented 12 UEY sites, 6 projects funded in 2005 and 6 projects funded in 2007. This includes the same projects that responded to the survey of community project team members and two additional projects.

The questionnaire had three sections: the nature and length of the involvement of the coalition member with the UEY project; the performance of the project (including questions about the Action Plan); and lessons learned and the transferability of the UEY project to other populations and social issues.

The unit of analysis for the survey was the survey respondents. However, as there were multiple responses about the same projects, the number of different projects represented in each response category was identified.

3.3.6 Case Studies of UEY Projects

The objective of the case studies was to gather information on the longer term results of the program and the sustainability of the activities, lessons learned and transferability of the model, along with details of the community contexts within which the projects were implemented.

Initially, 10 potential case studies were randomly selected, taking into consideration their region of Canada; urban, rural or mixed setting; language; type of project recipient organization (school board, other public sector entity; or not-for-profit organization or coalition); and relative level of socio-economic advantage or disadvantage. Footnote 13 A sample of 10 backup case studies was also selected, using the same criteria and aiming for the same overall distribution of characteristics.

All 10 initial cases were then invited to participate in the case studies. The most similar case studies from the back up list were selected to replace those among the initial 10 case studies that declined to participate. As the case study solicitation process from the initial list of 10 potential cases and 10 backup cases had yielded only five case studies and none from the 2007 group by the data collection deadline, a sixth was solicited from among three 2007 projects that had not responded to the survey invitations. One of these accepted and was included, for a total of six completed cases out of 15 Footnote 14 that were contacted for the case studies.

The cases studies included the following elements:

Document review. A document review was conducted of all materials on this project held by HSRDC. This included: proposal and supporting documentation; contribution agreement and amendments; documents from any prior or parallel projects or activities related to the UEY project; research, mapping reports and other information collected by projects; promotional materials; knowledge translation and outreach materials; site visit reports prepared by UEY staff; project websites; and any other relevant documentation.

Key informant interviews. Once the project had accepted to participate as a case study, a visit was arranged to the project site and in-person interviews were conducted with individuals identified in the project documentation and /or through discussion with the project recipient organization. Follow-up telephone interviews with relevant individuals who were not available on the day of the visits were also conducted. For the last recruited case, only telephone interviews were conducted. Depending on the site, those interviewed included: the project’s community coordinator; members of the community coalition including its chair or president; the recipient organization sponsoring the project; and researchers involved in the UEY research process. Individual or group interviews were conducted with a total of 35 case study participants.

The interviews used a semi-structured interview guide based on the evaluation questions. The qualitative data for each case were synthesized into narrative case reports using basic content analysis, by each evaluation question. The case reports were then subject to a cross case analysis using a matrix approach, summarizing key findings by evaluation question.

3.3.7 Summary of data sources

The table below summarizes the data sources for the evaluation.

| Data source | Pilot project | 2005 (n = 21 projects) | 2007 (n = 15 projects) | Total (n = 36 projects) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| File review | N/A | 21 | 15 | 36 |

| Survey of community project team members (72 potential respondents) | N/A | 4 projects 9 interviews |

7 projects 10 interviews |

11 projects 19 interviews |

| Survey of community coalition members (190 potential respondents) | N/A | 6 projects 32 interviews |

6 projects 29 interviews |

12 projects 61 interviews |

| Case studies (15 projects invited) | 1 project 6 individuals interviews |

4 projects 26 individuals interviews |

1 project 3 individuals Interviews |

6 projects 35 individuals interviews |

3.4 Methodological Limitations

As with any evaluation there were challenges encountered in implementing the methodologies for the UEY evaluation. These resulted in the following limitations to the findings and conclusions of this evaluation:

Lower than expected response rates in surveys and case studies, despite multiple solicitations. Possible explanations for the low response rate include elapsed time since the end of the 2005 projects and data collection was conducted during the period when 2007 projects were nearing the end of the project, thus, wrapping up final project deliverables. When a response was received, the reasons for refusal given were most often lack of time.

Possible bias in project reporting. The only line of evidence to include all UEY projects was the document and file review, which consisted of project self-reports to HRSDC as required under their funding agreements. The likelihood of their accuracy is enhanced because the reports would be circulated and therefore subject to quality control. However, the risk that the reports highlight successes and give less attention to challenges may exist.

Challenges in attribution of results to UEY . As identified throughout the report, for several of the expected outcomes, programs other than the UEY Initiative with similar objectives for early childhood development were also operating in some areas of Canada. As would be expected when evaluating the impact of projects with complex interactions with other activities and people in the community, it is difficult to attribute the observed results solely to UEY.

4. Findings

This chapter presents the evaluation findings, synthesized across the lines of evidence and across evaluation questions into three main issue areas: relevance of the UEY Initiative, performance as measured by achievement of value and progress toward achievement of intended outcomes, and lessons learned.

4.1 Findings Related to the Relevance of the UEY Initiative

The evaluation evidence suggests that the UEY Initiative was relevant to the needs of communities working to improve life chances for their young children and that the Initiative was in keeping with federal government, HRSDC and provincial government policies and programming related to early childhood development. Building knowledge and gathering information were seen as appropriate roles for the federal government, as these activities brought a national perspective on early childhood development issues and assisted in the use of standardized data collection instruments.

It is important to recognize that the UEY Initiative was expected to operate for a specified period of time (i.e. seven years) after which the funding for the Initiative was to end. As such, findings suggest that the Initiative served its intended purpose in enabling communities to better understand the needs of young children and families so that communities can work together to enhance programs and services to meet those needs.

4.1.1 Need for UEY

Data in this section are drawn from: document and file review, literature review, key informant interviews, and case studies.

Initial need

Evidence from all the lines of evidence suggests that there was a demonstrable need for the UEY Initiative within many communities working to improve life chances for children. The document and file review found that a total of $14.7 million out of the available $16.4 million (about 90% of available funds) was used by the recipient organizations. Most of the remaining funds were allocated to projects but not spent for a variety of reasons. This suggests that the level of need was at least sufficient to warrant the level of financial commitment established for the UEY Initiative.

In addition, federal and provincial key informants concurred that the UEY Initiative responded to a demonstrable need. All federal representatives interviewed stated that the UEY Initiative was conceived at a time when several converging factors created an ideal environment for an initiative that aimed at gathering empirical knowledge about the impact of the community on children’s development during the early years. Moreover, its design was aligned with emerging research showing that supportive communities for young children in the early years contribute to later positive developmental outcomes.

In considering whether there is a continued need for the UEY Initiative, findings are less clear. The document and file review focused on evidence of Initiative uptake with the view that evidence of demand for the Initiative among communities across the country would indicate continued need. In two UEY Calls for Proposals, a total of 66 applications were received – 35 in 2005 and 31 in 2007. Of these sixty-six applications, a total of 36 projects (55%) were successfully funded (21 in 2005 and 15 in 2007) in eight provinces. Thus, uptake on the Calls for Proposals exceeded funding capacity. This can be seen as an expression of need for the kind of research and organizational support offered by the UEY Initiative.

Federal and provincial government representatives agreed that there is a continued need for governments to focus on early childhood development, especially in terms of school readiness. The findings from the key informant interviews show that the circumstances that led to the creation of the Initiative are still present. The continued need in communities for support in collecting and applying empirical data on young children’s development is demonstrated by an increased use of EDI in planning and policy development by provinces and territories.

From a provincial perspective, the extent to which a continued need was perceived for a UEY-like program depended largely on the jurisdiction under consideration. The evaluation found that provinces are continuing to invest in early childhood development, drawing on research that describes children’s development. All provincial jurisdictions interviewed stated they have the desire, intent or commitment to continue the ongoing EDI administration. There is, however, variation in political prioritization, level of resourcing, and degree of organization of action in ECD across jurisdictions. Some provinces are providing ongoing support to community coalitions and mobilization, including continued funding of UEY sites as well as many others. In the larger jurisdictions provincial investments in ECD continue and have considerably exceeded, or will exceed, the UEY support, which was in a relatively small number of communities in each province. It is important to recognize that the UEY Initiative was expected to operate for a specified period of time (i.e. seven years) after which the funding for the Initiative was to end. As such, findings suggest that the Initiative served its intended purpose in enabling communities to better understand the needs of young children and families so that communities can work together to enhance programs and services to meet those needs. There is nonetheless the view that the federal government demonstrate commitment to and leadership in early childhood development, in a national child care plan and other forms of support.

The evaluation findings suggest that there is continued need for federal support for research-driven and other types of early childhood development initiatives in certain jurisdictions but not necessarily for the full UEY approach where relevant data and operational support are available provincially or regionally.

The UEY Initiative was designed to culminate in Community Action Plans based on empirical evidence. The case studies and surveys suggest that more investment is needed to implement UEY Action Plans. Coalition and community project team members reported that they lack time and resources to ensure implementation of their Action Plans in order to maximize the gains made under the UEY Initiative. This suggests that, in some jurisdictions at least, communities would continue to benefit from some form of continued government support.

Evidence from the research literature

The review of provincial initiatives on ECD found that there has been a burgeoning growth in early childhood interventions across Canada since UEY was launched, and new investments continue to be announced. While research still supports the importance of early intervention, evidence also suggests that the issue may be more complex than originally envisioned, and in particular that parenting variables may largely outweigh community or neighborhood effects. Research questions continue to be framed around the influences of communities and community-based intervention on children’s development, but findings are not always supportive of either a strong or a direct link, and some neutral and negative findings as well as positive ones have been reported. Nonetheless, the evidence is now much stronger that early intervention – at least intervention in the early school years – is associated with improved long-term educational and social outcomes, supporting one of UEY’s key underlying premises.

4.1.2 Consistency of UEY with departmental and federal government objectives

Data in this section are drawn from: document and file review and key informant interviews.

From these two lines of evidence there was convergence that at the time it was implemented, UEY was relevant to federal government and HRSDC objectives. Interviews with HRSDC officials and other federal and provincial representatives indicated that, following on the 1999 National Children’s Agenda Footnote 15 , the Initiative was one demonstration of federal leadership in ECD, an area that was cresting in interest across jurisdictions. The Communiqué on Early Childhood Development (ECD) of 2000 involved the transfer of funds to the provinces and territories to target healthy pregnancy, birth and infancy; parenting and family supports; early childhood development, learning and care; and community supports Footnote 16 . Under the Multilateral Framework Agreement on Early Learning and Child Care (2003), the federal government transferred funds to the provinces and territories to fund community-based early learning and child care programs and services. Both agreements have been extended to 2013-2014.

An examination of a 2006-2007 inventory of federal activities reported under Federal/ Provincial/Territorial agreements that targeted young children, found that HRSDC was supporting the development of young children through a range of programs including, among others, Footnote 17 parental and maternity benefits via employment insurance, universal child care benefits, and the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY).

In terms of current alignment, the document and file review found that the objectives and approaches of the UEY Initiative fit well under HSRDC’s current mandate and its strategic outcomes Footnote 18 , and in particular with its social development program area, which is directed to “support individuals, families and communities in overcoming barriers to social/economic inclusion and well-being.”

4.1.3 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

Data in this section are drawn from: document and file review, key informant interviews, and case studies.

Interviews with federal and provincial government representatives found that when the UEY Initiative began it was seen as showing an appropriate federal leadership role, in that some jurisdictions had not yet undertaken any action in ECD, or in using research to support ECD investments. However, the federal government was not the only jurisdiction with interest in acting to improve children’s outcomes during the 2005-2010 period. Although the UEY pilot phase first introduced the Early Development Instrument (EDI) in 1999, by the time the 2005 UEY projects began, the EDI as well as mapping approaches to understanding communities, and the community coalition model, were already being used in some jurisdictions. The document and file review found evidence that the UEY Initiative was designed and implemented with provincial/territorial support in a social policy environment that provided assurance that the Initiative was complementary to provincial and territorial roles and minimized the risk of duplication. Provincial and territorial officials were informed of federal plans for the national UEY Initiative and assisted with the assessment of UEY proposals.

Although the UEY Initiative was designed to complement provincial/territorial roles, evidence from the case studies and interviews with provincial government representatives showed some overlap with initiatives focusing on ECD and a research-based approach in some provinces. In particular, by 2007, there was notable sustained investment in this approach. This is reflected in the pattern of interest in the UEY Initiative. Provinces with existing activities had the highest number of projects: these were British Columbia (12 projects) and Ontario (9 projects). The result of this was that there was both some convergence of approaches and some complementarities with initiatives being implemented by some provinces. The case studies indicated that although there was overlap of funding from other sources in some UEY projects, these were reportedly used to complement and not to duplicate efforts. In other jurisdictions, where there was less investment in using research to support programming at the time, UEY gave communities unprecedented access to new data about children’s developmental status and community resources and new ways of looking at their needs and resources for young children.

In terms of current alignment, federal and provincial government representatives noted that current federal priorities have changed, so early childhood development has declined in importance. In addition, at this point in time, not all parts of the UEY approach are seen as appropriate for direct federal investment. While research and the creation of demonstration programs are still seen as relevant federal roles especially in areas where leadership is needed, government representatives, especially at the federal level, see that the federal government now prefers to play a lesser role in community mobilization for ECD issues than when UEY was first implemented.

4.2 Findings Related to the Performance of the UEY Initiative

The evaluation results suggest that the UEY projects produced research and community mapping reports, conducted planning sessions based on the research findings, and developed Action Plans. The findings suggest that UEY communities have laid important groundwork for ongoing efforts to address child development. The evaluation results also suggest that the UEY Initiative contributed to: better understanding among community members of the experiences of Canadian children in their early years; participating communities addressing the needs of children age six and under; and communities making informed decisions that benefited the lives of young children. In this way the UEY may also have contributed to the development of inclusive communities.

4.2.1 Achievement of Immediate Intended Outcomes

Data in this section are drawn from the document and file review. Available reports and documents indicate in anecdotal terms that community engagement in early childhood development existed prior to UEY. The presence of a community coalition with a mandate to address social development issues such as ECD was a UEY eligibility requirement. Although it was difficult to assess the extent of pre-existing community engagement, the project reports reviewed do indicate uniformly that the UEY Initiative successfully expanded the level of community engagement. The reports also indicate that this expansion of engagement has been accomplished through a number of different types of efforts:

- Early project presentations to community members and organizations of intermediaries such as school board members, teachers, health and social service workers and care givers, describing the UEY Initiative and seeking to recruit participation;

- The UEY research process itself, whereby organizations and individuals became aware of the Initiative and had an opportunity to participate;

- Periodic community events reporting on progress, reporting on research findings and actively seeking advice from the community as a basis for developing the Action Plans;

- Dissemination of UEY materials and reports to prospective participants; and,

- Community involvement, for example in-kind or financial contributions from the business community, in specific UEY projects.

4.2.1.1 Communities Are Able to Generate and Use Local Data Related to Children’s Development

A substantial number of children and their parents contributed to knowledge of the experiences of young children in Canada as part of the UEY Initiative, by the application of the two main research elements: the Parent Interviews and Direct Assessment of Children Survey (PIDACS) and the EDI.

For the 36 participating communities, a total of 14,169 children and 13,084 responded to the PIDACS. Participation in the EDI was also substantial with 43,632 children participating in the EDI research.

As noted above, EDI was in use prior to the 2005 and 2007 UEY projects in some communities. It must be recognized that the EDI is used more widely than just for the UEY Initiative, in particular by school boards. As well, the PIDACS was a community-level adaptation of an existing national survey, the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY). This means that care must be taken in attributing the knowledge gained through the use of these tools exclusively to the UEY Initiative.

Production of research and use in decision-making

The document review showed that research was used in decision-making in every participating community. Every community based its project on the collection of local data and on data provided by HRSDC-supported research at the national level. In every case this led to a mapping report and a research report that together described in considerable detail the state of the communities’ young children, the facilities, programs and services available to them and their parents, and the gaps that existed. Furthermore, every project used this information as a basis for developing an Action Plan for pursuing the community’s objectives.

The most common direct use of the UEY research, as demonstrated in the Action Plans, was to identify the range of issues that the community needed to address, and then to set priorities for action in the short and longer terms. For example, communities typically identified from the research findings that they needed more of a certain type of program or service such as more child care spaces, programming geared to specific population groups, or services in outlying areas where children were lagging behind in certain measures of development.

UEY community products developed

The document and file review described the number and types of products that were produced as a result of the UEY, based on the UEY data and the efforts of the community coalitions to draw research findings into a coherent plan for their communities. These included: resource guides (29 projects); research briefs (29 projects); website page/web tools (23 projects); presentations (21 projects); UEY brochures/fact sheets (19 projects); posters/calendars (17 projects); parenting tools (16 projects); a UEY Newsletter (15 projects); and, news articles, press releases, media interviews, television ads, CDs/DVDs/videos, and various other items. They were designed to provide information about early childhood development status and resources to the general public, intermediaries such as teachers, care givers and people working in health and social services positions, and parents.

4.2.2 UEY contribution to a better understanding of the early years’ experiences of Canadian children growing up in various social, economic, cultural and geographical environments

The evaluation findings suggest that UEY helped participating communities better understand the early years’ experiences of their children. All the lines of evidence converge on the finding that the data provided through UEY was useful to communities. As the previous section showed, there was considerable evidence from project reports that an extensive and broad array of products and community events were carried out, focusing on local UEY research findings and what they showed about needs and assets within communities for programs, resources and coordination to better support early childhood development.

All 19 of the community project team members surveyed agreed that the UEY Initiative led to a better understanding and increased knowledge of the early years’ experiences of Canadian children, as did all but one of the 61 coalition members interviewed.

Data from the case studies illustrate ways in which the UEY Initiative made contributions to communities’ understanding of the early years’ importance for later developmental outcomes. In one case, the access to information provided through the research was seen as having been of enormous benefit to inform and mobilize stakeholders. The research also served to validate service providers’ perceptions that the community faced significant challenges. The project increased the perceived importance of prevention among providers. It reportedly increased awareness among the general public of the importance of parents’ role in children’s development. In another case study, stakeholders reported gaining a better and more broadly shared understanding of their community, and it was realized that crucial data was not being collected and updated.

The findings suggest that gains in understanding considered to be most important were not necessarily among early childhood stakeholders, where the data were often seen as having confirmed what was already suspected by people working with children and families. Gains were more likely among external stakeholders such as municipal governments.

Three of the case studies found that the UEY Initiative gave information about children more credibility to stakeholders who were less directly involved in the front-line work. Much was learned about inequities in the socioeconomic and geographic distributions of developmental outcomes within communities, which was often new to these external stakeholders.

The case studies and document review found that problems in implementing the data collection meant that some projects only had access to their PIDACS data very late; in one of the case studies, the data were not available for dissemination and use with partners before the project ended. The document review noted that these projects were left with the challenges of disseminating the information and forward planning.

Case study respondents in three cases noted that the mapping component of the UEY approach was viewed as highly successful, bringing new insight to communities about inequities in the geographic distributions of socioeconomic characteristics and developmental outcomes. This facilitated the engagement of new partners who had not previously been connected to early childhood actions, in particular municipal governments.

The research process itself was also viewed to be useful by many community members. Almost all of the coalition members surveyed agreed that the research process was useful for orienting future collaboration and action. Case study respondents in two cases noted that they had developed community capacity to engage more critically with research and to understand how research could be beneficial to decision-making for policy and program development that could affect children’s outcomes.

4.2.3 Achievement of Intermediate Outcomes

Findings in this section are drawn from: document and file review, surveys of community project team members and community coalition members, and case studies.

All data sources indicate that the UEY initiative achieved its intended outcomes, with greater perceived success among the earlier project wave: coalition members from 2007 projects were less positive in their assessment of overall success than members of 2005 projects (75% of respondents from 2005 projects versus 55% of 2007 projects said the project had been very successful). Fourteen out of 19 community project team members agreed that their project had been very successful. Data on specific expected outcomes are described below.

4.2.3.1 Communities Develop Action Plans to Address the Needs of Young Children

As required under the Contribution Agreements, all the UEY projects surveyed had developed Action Plans, and the file review found that the Plans were directed toward benefiting the lives of young children. While the document review could not determine the quality of the recommendations, or how suitable they were for the communities, it can be said that the large majority of Action Plans included clear statements of objectives and specific, targeted actions to achieve set objectives.

Converging with the findings of the file review, the case study projects’ Action Plans’ contents ranged in scope from detailed strategic and operational plans with action items and responsibilities identified, to an identification of actions that could be carried out.

The review of the projects’ Action Plans documented considerable range and diversity in the action strategies established by the UEY projects. The majority of projects focused on three strategic areas: 1) continued expansion of community awareness and engagement to keep ECD on the public agenda; 2) continued emphasis on collaboration and joint planning; and 3) continued development of new knowledge and continued dissemination of knowledge to help ensure informed decision-making. The majority of projects also emphasized the improvement of specific services for young children and their parents.

Almost all of the community project team members (16 out of 19 respondents) said that they were satisfied or very satisfied with the Action Plan that was developed as part of their UEY project. Among the coalition members surveyed, 47 out of 61 (77%) said they were satisfied or very satisfied with their Action Plan.

Survey respondents were asked to rate the extent to which their Action Plans addressed the needs of young children. These ratings confirmed that the Action Plans were seen as achieving this Initiative outcome – although a few respondents were not able to answer the question. All who did answer agreed that their Action Plans addressed the needs of young children at least to some extent.

Although implementation of Action Plans was not part of project funding through the UEY Initiative, it was intended that after developing Action Plans based on sound research and a planning process, communities would continue to implement the Plan once the project was completed. The data suggest that not all the communities surveyed had implemented their Action Plans by the time of the summative evaluation. Eight of the 19 community project team members (42%, equally split between 2005 and 2007 sites) said their Action Plans were implemented, while among coalition members surveyed, 69% (72% of 2005 projects, 66% of 2007 projects) said their Action Plans were implemented. The case studies provided examples of how some Action Plans have been integrated into other, expanded initiatives, such as ones targeting children and youth aged 0 to 17. Case studies also suggested that the Action Plans were generally developed at the end of UEY project funding, and because the research component had taken longer than expected to be carried out, there was not as much time as desired to develop, validate and disseminate the plans.

4.2.3.2 Communities Make Informed Decisions that Benefit the Lives of Young Children

The evaluation provided evidence that UEY helped the participating communities make informed decisions about the lives of young children. Almost all of the surveyed coalition members (92%) and all 19 community project team members agreed that their communities used UEY information for that purpose. According to the survey responses, the UEY research results were most often used in improving services (89% of community project team members and 75% of coalition members reported this) and filling gaps in services (84% of community project team members and 67% of coalition members reported this).

In addition, a majority of the community project team (17/19) and coalition members (2007 – 86%; 2005 – 65%) agreed that as a result of UEY, new or improved services were put into place. Examples of new or improved services or policies based on UEY research data were documented in the case studies and the file review. These were grouped into several types:

- Enhanced planning and coordination: using data to make a case for new services or sites, to identify locations for new services, to improve coordination among providers and reduce duplication of services;

- Redirection of resources towards addressing young children’s physical health and well-being needs and to improve future EDI scores;

- Resource allocation decisions that take specific groups of children’s needs into account rather than making decisions based solely on population;

- Early detection and referral: new mobile early screening programs; enhanced kindergarten registration processes for earlier screening, and new transition to kindergarten programs;

- Integration of EDI results into municipal and regional family-related policies;

- Wraparound services for families of young children: school-based integrated educational, health, social services for parents and preschool children; and