Evaluation of the Workforce Development Agreements

On this page

- Executive summary

- Management response

- Introduction

- Workforce Development Agreements

- Evaluation objectives, governance, scope, questions and lines of evidence

- Evaluation findings

- Conclusions and recommendations

- References

- Appendix A: Evaluation matrix

- Appendix B: Key literature review findings

- Appendix C: Documents included in the document review

- Appendix D: Survey methodology and respondent profile

- Appendix E: Additional labour market outcome tables

List of abbreviations

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- WDAs

- Workforce Development Agreements

- P/Ts

- Provinces and territories

List of charts

- Chart 1: Percentage of participants who identified pre-participation labour market needs

- Chart 2: Number of P/Ts experiencing challenges with each of the WDAs’ provisions

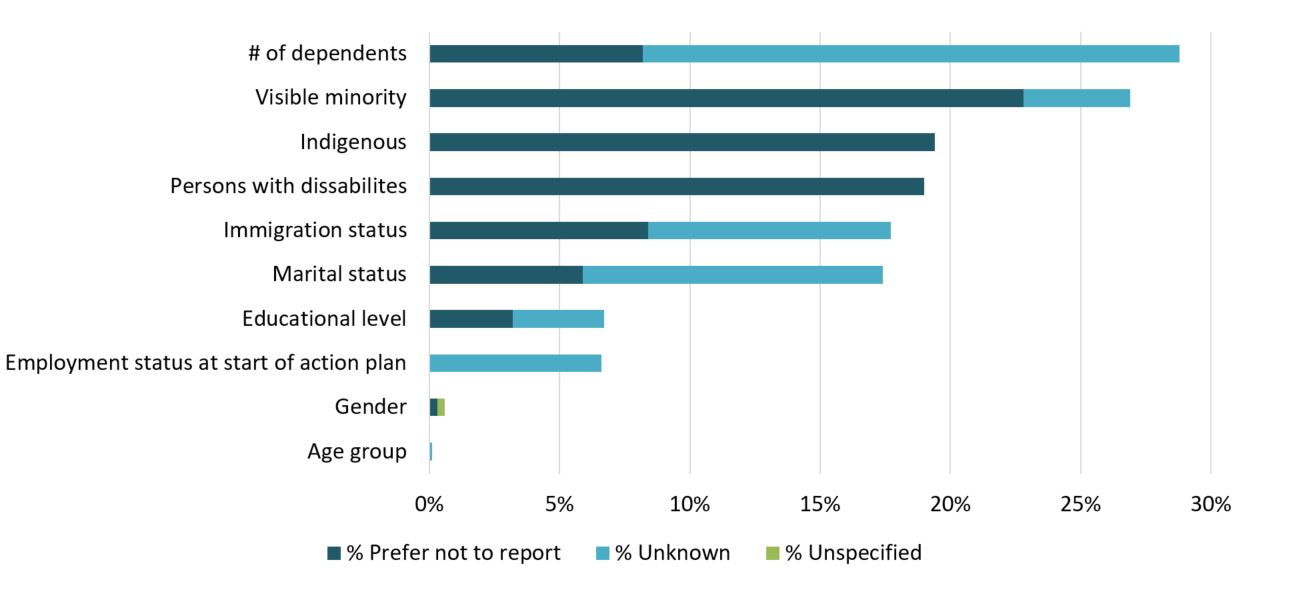

- Chart 3: Percentage of missing values in socio-demographic variables for the 132,402 WDA participants in 2020 to 2021

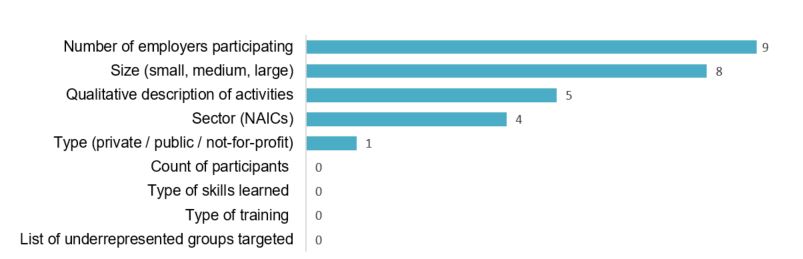

- Chart 4: Number of P/Ts reporting employer-sponsored training data by value

- Chart 5: Percentage of national survey respondents who reported that their labour market needs were addressed by the WDA programs and services they received

- Chart 6: Percentage of national survey respondents who reported being completely or very satisfied with the WDA program or service they received

List of tables

- Table 1: P/T funding allocation for fiscal years 2017 to 2018 and 2018 to 2019.

- Table 2: Preliminary profile of 132,402 WDA participants in 2020 to 2021

- Table 3: Programs and services provided to persons with disabilities

- Table 4: Missing values in participant data upload by P/Ts

- Table 5: Employment rates and changes in employment rates at 3 points in time, by WDA program and service for all national survey participants

- Table 6: Employment rates and changes in employment rates of national survey respondents at 3 points in time, by employment status at the beginning of their WDA participation

- Table 7: Employment rates and changes in employment rates at 2 points in time in the British Columbia survey, by employment status at the beginning of respondents’ WDA participation

- Table 8: Employment rates and changes in employment rates at 3 points in time, for all national survey participants by population subgroup

- Table 9: Weekly earnings and change in weekly earnings at 3 points in time, by WDA program or service, for all national survey respondents

- Table 10: Weekly earnings and change in weekly earnings at 3 points in time of national survey respondents, by employment status at the beginning of their WDA participation

- Table 11: Weekly earnings and change in weekly earnings at 3 points in time, by population subgroup, for all national survey participants

Alternate formats

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

Executive summary

The Workforce Development Agreements (WDAs) are a key mechanism to provide training and employment supports to Canadians. Through bilateral agreements with provinces and territories (P/Ts), financial support is provided for the design and delivery of programs and services to help participants obtain the training, skills, and work experience they need to improve their labour market outcomes. The agreements also allow for the provision of support to employers seeking to train current and future employees.

The agreements’ broad participant and program eligibility criteria aim to give P/Ts the flexibility they need to design and deliver programs and services that meet their jurisdictions’ labour market needs. The agreements aim to support those who are further away from the labour market or are underemployed, and include targeted funding for persons with disabilities as well as funding that can be used to serve other underrepresented groups, such as Indigenous peoples, youth, older workers, women, immigrants and newcomers to Canada.

Evaluation objectives

- Describe the types of programs and services funded by the agreements and the delivery approaches

- Identify the labour market needs and priorities that the agreements are being used to address

- Examine the labour market outcomes observed for participants

- Identify strengths and challenges associated with the design and implementation of the agreements

The WDA investment

With a total on-going annual funding envelope of $722M, an additional $900M over 6 years from April 2017 to March 2023, as well as an additional $1.5B in 2020 to 2021 to support economic recovery, the WDAs provide training and employment supports to Canadians, particularly those further from the labour market, through bilateral agreements with provinces and territories (P/Ts).

Evaluation methodology

The evaluation uses a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods to address the evaluation questions:

- 5 literature reviews

- a document review

- a national survey of 5,707 WDA participants and a survey of 3,017 participants in British Columbia

- 64 key informant interviews with ESDC officials, P/T representatives, and service provider/caseworkers who work with persons with disabilities

- an assessment of program data provided by the P/Ts

Key findings

- Nearly 132,400 individuals participated in 291,200 WDA-funded programs and services in the 2020 to 2021 fiscal year

- The agreements reached targeted participants, namely those who are unemployed or further from the labour market, as well as members of underrepresented groups

- Survey respondents’ employment rate increased by 16 percentage points post-participation, nationally from 48% to 64%, and in British Columbia from 66% to 82%

- The employment rate of those who were unemployed pre-participation increased by 43 percentage points post-participation nationally and 62 percentage points in British ColumbiaFootnote 1

- 36% of the national survey respondents reported earning more post-participation, and an average weekly earnings increase of $90

- Approximately 70% of national survey participants attributed the increase in their employment and earnings (in part or to a great extent) to the WDA programs or services they received

- 74% of national survey participants reported a high level of satisfaction with the programs and services they had received

- While challenges have been identified, almost all P/Ts emphasized that the WDAs are, overall, flexible enough to meet their needs and to respond to their priorities

Challenges and lessons learned

Key informants identified challenges relating to the agreements’ provisions and implementation.

- P/T representatives in all 12 jurisdictions identified the insufficient funding level as the most important challenge associated with the agreementsFootnote 2

- ESDC officials acknowledged that WDA participants are generally further away from the labour market and require more intensive programs and services to improve their labour market outcomes

- More flexibility with respect to how funding can be used (year-to-year carryover funds, and administrative funds) would further enable P/Ts and third-party service providers to respond to labour market needs

- Third-party service provider staff retention and service continuity represent ongoing challenges, which have repercussions on service delivery and participant outcomes

- These can be exacerbated by the lack of multiyear funding provided by P/Ts to service providers

- Lack of clarity among service providers and P/Ts with respect to program, service, and participant eligibility criteria can hamper program/service design and delivery

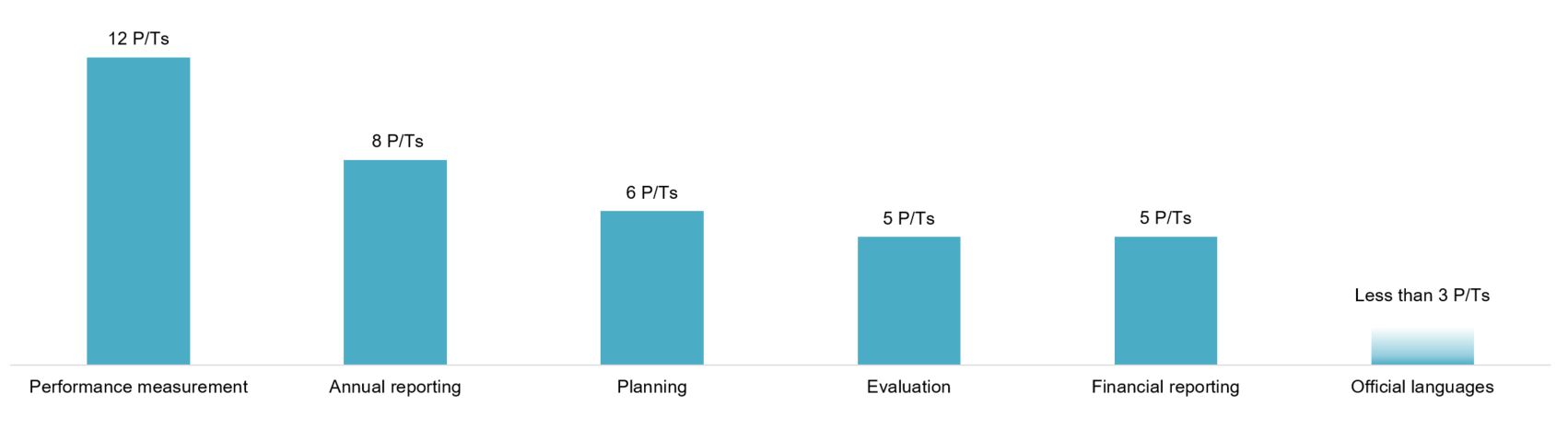

- All P/Ts identified challenges meeting some of the WDAs’ performance measurement provisions (such as data collection and reporting, and outcome and performance indicators)

- Most P/Ts identified challenges meeting the agreements’ annual reporting provisions, such as:

- delays in receiving data from service providers

- difficulty coordinating reporting from different P/T departments

- lack of alignment between federal and P/T reporting timelines

- duplication of efforts between the WDAs and Labour Market Development Agreements deliverables

The literature reviews and key informant interviews with P/T representatives and service providers/caseworkers identified lessons learned relating to the implementation and delivery of WDA programs and services.

- Meeting the needs of participants who are further from the labour market is resource intensive, requiring a broad spectrum of coordinated life stabilization,Footnote 3 health, mental health, education, pre-employment, employment, and employment maintenance supports and services offered over a longer time period

- Providing services to those who are further away from the labour market requires stable services and skilled staff who develop relationships of trust with participants, employers, and other service providers over time

- Wage subsidies are effective in helping to overcome barriers to labour market entry, particularly when combined with intensive employment services

- Although resource intensive, skills development and training are associated with more significant long-term improvements in earnings and career advancement

- When assisting those who are further from the labour market, using a dual model that focuses simultaneously on the needs of participants and those of employers, and that provide ongoing support to employers to deal with issues as they arise once they have hired a participant, leads to more successful outcomes

Capacity to assess the impact and effectiveness of the WDAs in the future

The transfer agreements require the assessment of the impact and effectiveness of funded programs and services. Based on established practices, this is achieved by comparing the outcomes of participants with those of similar non-participants (comparison group). However, building a comparison group requires access to a wide range of socio-demographic and labour market information on participants and similar non-participants.

A data assessment was conducted to determine the extent to which the participant data, and other available data sources, could be used to meet the agreements’ evaluation requirements. Overall, the data assessment revealed that assessing the impact and effectiveness of the WDA programs and services, as is done for the Labour Market Development Agreements, will be more challenging. This is especially the case for employer-sponsored training and programming for persons with disabilities.

A number of steps would enhance the ability to assess the impact and effectiveness of the WDA-funded programs and services in the future.

For exploration purposes, access to data on Employment Insurance applicants deemed to be not eligible, to P/T social assistance data and to data on immigration and citizenship, maintained by Statistics Canada, may further enable the building of comparison groups for some participants (for example, social assistance recipients, immigrant and visible minority participants).Footnote 4

In the case of employer-sponsored training,Footnote 5 this type of training does not lend itself to the construction of a comparison group given the fact that participants are already employed. In that context, the transfer agreements’ performance measurement strategy does not currently require the collection of data on these participants. Therefore, future evaluation would focus on assessing the relevance of investing in these programs using qualitative data on employers and the type of training provided.

Based on recent studies and on qualitative information collected from 40 organizations across Canada who provide services for persons with disabilities,Footnote 6 additional information on the severity of their disability and/or their capacity to work full-time would enable a sound interpretation of observed labour market outcomes and estimated impacts if adequate comparison groups were found.

Recommendations

A total of 3 recommendations emerge from the evaluation findings.

Challenges associated with assisting person with disabilities to integrate into the labour market

Recommendation 1

To support program and service delivery, ESDC and P/Ts are encouraged to share and discuss the lessons learned, best practices and challenges associated with serving persons with disabilities and individuals who are further removed from the labour market.

Rationale for recommendation 1

As noted in the report, third-party service providers interviewed as part of the evaluation reported the following challenges:

Staff retention and service continuity represent ongoing challenges, which have repercussions on service delivery and participant outcomes. These can be exacerbated by the lack of multiyear funding provided by P/Ts to service providers.

Meeting the needs of participants who are further from the labour market is resource intensive, requiring a broad spectrum of coordinated life stabilization,Footnote 7 health, mental health, education, pre-employment, employment, and employment maintenance supports and services offered over a longer time period. Providing services to those who are further away from the labour market requires stable services and skilled staff who develop relationships of trust with participants, employers, and other service providers over time. These approaches to service delivery are resource intensive.

Program and participant eligibility criteria

Recommendation 2

Building on existing flexibilities in addressing labour market challenges, ESDC and P/Ts are encouraged to continue working to ensure that the WDA programming responds to the needs of the ever-evolving labour market and discuss ways to reach more individuals who are further removed from the labour market.

Rationale for recommendation 2

Existing flexibility in terms of program, service, and participant eligibility criteria is widely appreciated by P/Ts and third-party service providers alike. Some P/Ts and over half of interviewed third-party service providers indicated that having more clarity around what is eligible and ineligible for funding would enable them to take fuller advantage of the WDA’s flexible eligibility criteria. Specifically, key informants reported that more clarity would be beneficial around:

- identifying programs and services that are eligible and ineligible for funding

- identifying participants who are eligible and ineligible for assistance

- defining what flexibility exists to offer pre-employment programs and services (such as mental health counselling, addictions counselling, and access to housing and transportation)

- this would help third-party service providers to understand which types of programs and services can be funded under the transfer agreements in their jurisdiction, and to develop their proposals

Data collection

Recommendation 3

ESDC and P/Ts are encouraged to discuss what further steps could be taken to facilitate the collection of data necessary to assess the impact of the WDA programming and demonstrate the results to Canadians.

Rationale for recommendation 3

As observed in the report and based on the first year of participant data uploaded (2020 to 2021), challenges around the completeness of the data collected in some P/Ts could limit the ability to assess the impacts of WDA programs and services in these jurisdictions in the future. Key informants identified issues relating to third-party service provider capacity (such as access to IT systems, software, and human resources), P/T capacity (such as access to appropriate IT systems, limited human resource capacity), and barriers to interdepartmental data collection, sharing, and reporting in some P/Ts.Footnote 8 Similar challenges were observed for the requirement to report aggregate-level information on employer-sponsored training. It is also acknowledged that the pandemic may have exacerbated participant data collection challenges.

Management response

ESDC would like to thank all members of the WDA Evaluation Steering Committee, including the Evaluation Working Group, for their valuable contributions to this evaluation of the Workforce Development Agreements.

The findings demonstrate that the Workforce Development Agreements reach the intended participants, namely those who are unemployed or further from the labour market, as well as members of underrepresented groups. During the period covered by the evaluation, nearly 15% of WDA participants were older workers, 22% were youth, 60% were persons with disabilities, 19% were immigrants, and 6.5% were indigenous peoples.

Results of the national survey of WDA participants, conducted as part of the evaluation, demonstrate efficacy of programming under the agreements.

- Nearly 75% of survey participants indicated that they were either completely or very satisfied with the program or service they received

- Over 70% have indicated that the WDA programs and services they received addressed their labour market needs

- Employment rate for those who were unemployed pre-participation increased by 43 percentage points post-participation

- Survey respondents reported earning an average of $90 more per week

The findings of the evaluation demonstrate the impact of these agreements and point to opportunities for collaboration with PTs on how they could be further strengthened to respond to the changing labour market conditions and continue to benefit employers and workers across the country. ESDC is looking forward to engaging with P/Ts on the identified strands of work.

Recommendation 1

To support program and service delivery, ESDC and P/Ts are encouraged to share and discuss the lessons learned, best practices and challenges associated with serving persons with disabilities and individuals who are further removed from the labour market.

Management response

As the evaluation shows, the WDAs reach members of underrepresented groups and those further away from the labour market: 60% of participants covered by the scope of this study were persons with disabilities, 47% were unemployed, and most (56%) had low educational attainment (high school diploma or less). The surveys of WDA participants showed that WDAs lead to positive outcomes, such as an increased employment rate for those who were unemployed pre-participation and increased weekly earnings.

In order to identify opportunities to further enhance participant outcomes under the WDAs, ESDC will discuss with each of the P/Ts, the lessons learned, best practices and challenges associated with serving persons with disabilities and individuals who are further removed from the labour market.

In addition, ESDC will collect and analyse P/T feedback on the impact of temporary flexibilities introduced in response to COVID-19 in 2020 to 2021 on the WDA programs and services.

Recommendation 2

Building on existing flexibilities in addressing labour market challenges, ESDC and P/Ts are encouraged to continue working to ensure that the WDA programming responds to the needs of the ever-evolving labour market and discuss ways to reach more individuals who are further removed from the labour market.

Management response

P/Ts have the flexibility to establish eligibility criteria for their programs and services within the broad parameters set out in the WDAs, which specify eligible costs, beneficiaries and programs. Findings of this evaluation demonstrate that currently the WDAs reach the target populations, particularly those further from the labour market. In particular, based on interviews, the evaluation reveals that the WDAs are an effective labour market program for P/Ts.

- In most (11) jurisdictions, P/T representatives reported that the WDAs provided their jurisdiction with the flexibility to design and deliver employment programs and services aimed at addressing the needs of the local labour market and labour force

- Three P/Ts found that the WDAs are more flexible than the Labour Market Development Agreements, and that the WDAs allowed them to cover gaps in the Labour Market Development Agreements’ program and participant eligibility criteria

The evaluation also illustrates that the WDAs contribute to improving participants’ labour market outcomes and help to meet participants’ skill development and work experience needs. In the national survey of WDA participants, over 70% of respondents indicated that the WDA program or service they received addressed their labour market needs.

ESDC will work with P/Ts to ensure that the WDAs continue to respond to the rapidly evolving labour market conditions and needs of those further from the labour market and to identify ways to improve the labour market outcomes of an even higher number of Canadians. In particular, ESDC and P/Ts will discuss the impact of the WDA funding, including the additional investments provided through Budget 2017 and those in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, on P/T labour markets and identify lessons learned to inform future policy decisions.

Recommendation 3

ESDC and P/Ts are encouraged to discuss what further steps could be taken to facilitate the collection of data necessary to assess the impact of the WDA programming and demonstrate the results to Canadians.

Management response

ESDC has been working with P/Ts to implement data collection requirements of the WDAs since their introduction in 2017. All twelve jurisdictions with WDA information sharing agreements are currently providing data in accordance with the Performance Measurement Strategy. Work is underway to finalize an information sharing agreement with the remaining jurisdiction.

In addition, ESDC has worked with P/Ts to streamline annual planning and reporting requirements. ESDC and P/Ts will explore opportunities to further align LMDA and WDA reporting requirements to reduce duplication.

ESDC will continue to work with P/Ts to ensure that all stakeholders are well equipped to collect, compile, and share data necessary to assess the results of the WDA programming.

Introduction

This report presents the main findings and conclusions from the evaluation of the Workforce Development Agreements (WDAs). Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) worked jointly with 12 Provinces and Territories (P/Ts) to undertake the evaluation.

Evaluation objectives

- Describe the types of programs and services funded by the agreements and the delivery approaches

- Identify the labour market needs and priorities that the agreements are being used to address

- Examine the labour market outcomes observed for participants

- Identify strengths and challenges associated with the design and implementation of the agreements

Lines of evidence

Five literature reviews

The literature reviews summarise Canadian and international literature on effective labour market programs and services to assist specific population groups. These included immigrants and newcomers to Canada, Indigenous peoples, older workers, persons with disabilities, social assistance recipients and youth.

A document review

The review of federal, provincial, and territorial government documents provides insight on the design, implementation, and use of WDA programs and services.

Surveys of WDA participants

Two surveys were conducted to identify the short-term labour market outcomes for participants in WDA programs and services. These included:

- a survey of 5,707 participants in 8 jurisdictions

- a survey of 3,017 participants in British Columbia

Key informant interviews

Sixty-four key informant interviews with 110 individuals representing the federal and provincial/territorial governments and service providers were conducted. These include:

- 2 interviews with 6 federal ESDC officials

- 19 interviews with 47 P/T government officials in 12 jurisdictions

- 43 interviews with 57 case workers and service providers who provide WDA-funded programs and services to persons with disabilities

A data assessment

The assessment examines the extent to which the program data collection provisions under the performance measurement strategy were met.

The evaluation report is organised as follows:

- introduction providing a succinct summary of the evaluation objectives and lines of evidence

- overview of the WDAs

- overview of the evaluation scope and methodology

- evaluation findings

- key evaluation findings and recommendations

Workforce Development Agreements

Introduced in 2017, the WDAs are bilateral funding agreements between the Government of Canada and each P/T Government. The agreements support the delivery of employment and training programs and services for Canadians and employers. The WDAs consolidated and replaced the Canada Job Fund Agreements,Footnote 9 the Labour Market Agreements for Persons with Disabilities,Footnote 10 and the Targeted Initiative for Older Workers. They complement the long-standing Labour Market Development Agreements, which have similar goals.Footnote 11

The WDAs are open-ended agreements, with a total on-going annual funding envelope of $722 million. The Government of Canada allocated an additional $900 million to the WDAs over the 6 fiscal years from April 2017 to March 2023.Footnote 12 In the 2020 to 2021 fiscal year another $1.5B was allocated to the WDAs to support economic recovery efforts in response to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This section provides an overview of the agreements’ program objectives, eligible activities, eligible participants and employers, accountability framework, program funding, and evaluation provisions.

Program objectives

The WDAs support the provision of employment and training supports to Canadians. They aim to help participants improve their labour market outcomes. The agreements seek to provide P/Ts with the flexibility they need to address their labour market priorities and respond to emerging issues.

Overall, the WDAs:

- support Canadians, including those who are further away from the labour market, to develop the skills needed to find, keep, and advance in jobs, or reorient their careers

- require that a dedicated portion of each P/Ts’ annual allocation be used for programming for persons with disabilities

- P/Ts are also required to provide cost-matched programming

- can be used to provide supports to members of other underrepresented groups, which can include, for example:

- Indigenous peoples

- women

- youth

- older workers

- newcomers to Canada

- support employers seeking to train current or future employees

- encourage research and innovative projects to test new approaches to programs and service delivery

- complement the Labour Market Development Agreements, which focus primarily on unemployed workers with some connection to the Employment Insurance Program

Eligible activities

Examples of eligible activities include the following:

- skills training

- on-the-job training and workplace-based skills upgrading

- group interventions and job readiness assistance

- financial assistance and benefits related to the delivery of an eligible program

- employment counselling and services

- labour market connections

- employment opportunities or experiential learning and on the job development

- employer-sponsored training

Eligible participants and employers

Eligible participants and employers include the following:

- Canadian citizens

- permanent residents

- protected persons as per Immigration and Refugee Protection Act entitled to work in Canada

- employers, with the exception of federal and P/T governments, and federal crown corporations and agencies

WDA accountability framework and evaluation provisions

The agreements have an accountability framework and evaluation provisions.

As part of the accountability framework P/Ts produce and provide annual plans and annual reports to ESDC.P/Ts collect and report data on participants, programs and services to ESDC. Data is reported on a quarterly basis according to the provisions set out in the agreements. This provision took effect on April 1, 2020.Footnote 13

As part of the evaluation provisions: ESDC and P/Ts have a joint responsibility for the evaluation of the agreements. Together, they must ensure that funding is spent on programming and services that produce meaningful employment results for Canadians. All P/Ts, with the exception of Quebec, participated in the national level evaluation. Quebec is responsible for the conduct of its own evaluation activities. The evaluation is to be completed by March 31, 2022.

WDA program funding

Table 1 presents the transfer agreements allocation by P/T for the 2017 to 2018 and 2018 to 2019 fiscal years.

| Province/Territory | 2017 to 2018 | 2018 to 2019 |

|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | $13,324,443 | $13,198,830 |

| Prince Edward Island | $3,884,484 | $3,881,167 |

| Nova Scotia | $23,318,201 | $23,273,724 |

| New Brunswick | $18,129,668 | $18,185,042 |

| Quebec | $177,714,656 | $176,480,928 |

| Ontario | $296,579,293 | $296,494,169 |

| Manitoba | $29,442,783 | $29,462,080 |

| Saskatchewan | $28,557,595 | $28,366,230 |

| Alberta | $91,076,291 | $90,783,116 |

| British Columbia | $105,545,197 | $107,447,325 |

| Yukon | $3,142,463 | $3,142,463 |

| Northwest Territories | $3,142,463 | $3,142,463 |

| Nunavut | $3,142,463 | $3,142,463 |

| National | $797,000,000 | $797,000,000 |

Evaluation objectives, governance, scope, questions and lines of evidence

Evaluation objectives

- Describe the types of programs and services funded by the agreements and the delivery approaches

- Identify the labour market needs and priorities the agreements are being used to address

- Examine the short-term outcomes observed for WDA participants

- Identify strengths and challenges associated with the design and implementation of the agreements

Appendix A presents a complete list of evaluation issues and questions.

Evaluation governance

The evaluation was overseen by an Evaluation Steering Committee. The committee was composed of representatives from P/Ts, the ESDC Evaluation Directorate, and the ESDC Skills and Employment Branch. An Evaluation Working Group, composed of members of the Evaluation Steering Committee, provided further guidance and support throughout the evaluation process.

Evaluation scope

The evaluation is national in scope. While some information was collected at the P/T level, the evaluation report summarizes information at the national level. The key outcome is a national evaluation synthesis report pertaining to the design and delivery, and short-term post-program outcomes for participants. The evaluation focused on participants who started and completed a WDA-funded program or service between April 1, 2018 and September 30, 2019. All provinces and territories, with the exception of Quebec, were included in the evaluation. Quebec is responsible for the conduct of its own evaluation activities.

Evaluation methodology and lines of evidence

The WDA evaluation relies on multiple lines of evidence: literature reviews, a document review, surveys of participants, key informant interviews, and a data assessment. Using multiple lines of evidence helped to corroborate findings and to increase general confidence in the evaluation results. For a complete summary of how each line of evidence is used to address specific evaluation questions and issues, please consult Appendix A.

Literature reviews

Five literature reviews summarising Canadian and international literature on effective programs and services to support the labour market integration underrepresented groups were completed. Specifically, the literature reviews focus on the following population groups:

- immigrants and newcomers to Canada

- Indigenous peoples

- older workers

- persons with disabilities

- social assistance recipients and youth

A summary of literature review findings is provided in Appendix B.

Document review

A document review of federal, provincial, and territorial government documents on the design, implementation, and use of the WDA programs was undertaken. The document review also summarised any documented best practices and lessons learned though the implementation and delivery of WDA-funded programs and services. A list of documents included in the document review is provided in Appendix C.

Surveys of WDA participants

Surveys of WDA participants were undertaken to identify their short-term labour market outcomes.Footnote 14 Two surveys were conducted.

- A survey of 5,707 individuals in 8 jurisdictions who started and completed participating in WDA-funded programs and services between April 1, 2018 and September 30, 2019Footnote 15

- Respondents could choose to participate over the phone or to complete the questionnaire online

- The survey received a completion rate of 19%, which represents a margin of error of +/- 1.1% with a 95% confidence levelFootnote 16

- A survey conducted by British Columbia of 3,017 individuals in its jurisdiction who started participating in WDA-funded programs and services during the same reference period as the national survey

- Program participants were surveyed 3 months post-intervention, and those who responded to the 3-month survey were surveyed again 9 months later (12 months post-intervention)

- The findings presented in this report are based on the 12-month survey

- The survey received a response rate of 66%, which represents a margin of error of +/- 1.02% with a confidence level of 95%

More information on the survey methodologies and samples is provided in Appendix D.Footnote 17

Key informant interviews

A total of 64 key informant interviews were conducted.

- Two interviews with 6 federal ESDC officials and 19 interviews with 47 P/T government officials in 12 jurisdictions

- The interviews capture their perspectives on key issues related to the governance, design, delivery, and implementation of the transfer agreements

- Forty-three interviews with 57 caseworkers and service providers who provide WDA-funded programs and services to persons with disabilities

- The interviews capture their perspectives on the successes and challenges associated with the design and delivery of these programs and services

Interviews were conducted over the telephone or through video conference calls using a standard interview questionnaire.

Data assessment

A data assessment was completed to examine the extent to which the WDA data collection provisions under the performance measurement strategy are met. The assessment relies on data uploaded by P/Ts to ESDC since April 1, 2020. It includes only participants who started their programs and services after March 31, 2020.

Evaluation limitations

Data collection for the evaluation, including for the key informant interviews and the surveys, took place during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic negatively affected labour markets across Canada. Accordingly, the evaluation includes contextual findings, taken from the key informant interviews, on the pandemic’s impact on WDA program and service design and delivery. The evaluation also sought to control for the pandemic’s impact on participants’ labour market outcomes. To this end, survey respondents were questioned about their labour market outcomes both before and after the start of the pandemic.

The evaluation faced some limitations related to adequately assessing the impact and effectiveness of WDA programs and services on participants.

First, individual-level participant data enabling the construction of comparison groups, which would have been required to conduct an impact analysis, was not available. Therefore, the evaluation relied exclusively on participant surveys to assess the labour market outcomes of participants in WDA-funded programs and services. The surveys asked respondents to provide pre/post-participation employment and earning information. The national survey also asked participants to assess the extent to which employment and earning outcomes can be attributed to their participation in a WDA-funded program or service. However, surveys are subject to a range of limitations, including but not limited to recall errors, non-response bias, and sampling errors.Footnote 18 Accordingly, definitive conclusions about the impact and effectiveness of WDA-funded programs and services cannot be drawn from this evaluation. Nevertheless, the surveys provides unique insights regarding the labour market outcomes of program participants and their perception of program effectiveness.

Second, following consultations with participating P/Ts, numerous programs and services were excluded from the national survey. This was due mainly to the lack of participant contact information and/or because written consent permitting the transfer of contact information to ESDC had not been obtained. These issues applied to many programs targeting persons with disabilities.Footnote 19 Accordingly, persons with disabilities are underrepresented in the national survey of WDA participants.Footnote 20 This limitation was in part addressed through the inclusion of key informant interviews with service providers and caseworkers who work with persons with disabilities.

Third, when comparing the profile of national survey respondents to the preliminary profile of the 2020 to 2021 participants, important differences were noticed. These differences related to participants’ education levels, immigration history, and employment status at the beginning of participation.Footnote 21 These limitations, combined with the exclusion of numerous programs and services from the survey, impact the extent to which the national survey is representative of all participants.

Fourth, the 12-month survey sample used for the British Columbia survey consists only of participants who completed the 3-month survey. Accordingly, the results may be skewed depending on who responded to the 3-month survey.

Finally, key informant interviews confirmed that the type and severity of participants’ disability have a direct impact on their labour market goals. The type and severity of disabilities impact participants’ capacity to work on a full-time basis. Inability to secure and maintain full-time employment with benefits can deter participants from accepting paid work when it jeopardises their access to publicly-funded disability supports and benefits. These considerations have a direct impact on the interpretation of employment and earnings outcomes collected through the surveys of WDA participants.

Evaluation findings

Evaluation findings are organized around 4 main evaluation issues:

- program design and delivery

- supports for employers

- governance, planning, reporting and accountability

- labour market outcomes for participants in WDA-funded programs and servicesFootnote 22

Program design and delivery

Labour market priorities, objectives, and challenges addressed through the WDAs

P/Ts address a range of labour market priorities, objectives, and challenges through the WDAs. The document review and interviews with P/T representatives identified 6 main labour market objectives and priorities being targeted through the WDAs:

- improving and increasing training to align participants’ skills with labour market needs (11 P/Ts)

- improving participants’ labour market participation (11 P/Ts)

- improving the labour market participation of specific population sub-groups (11 P/Ts)

- improving labour market participation in specific sectors and industries (9 P/Ts)

- expanding education initiatives, such as adult literacy and essential skills, continuous learning, post-secondary education, workplace educationFootnote 23 (6 P/Ts)

- increasing the size and/or productivity of the workforce (6 P/Ts)

The document review also identified 4 main challenges that P/Ts seek to address through the transfer agreements:

- high unemployment and few job openings, including downturns in key sectors and industries (7 P/Ts)

- serving geographically dispersed populations living in rural and remote areas (4 P/Ts)

- access to a workforce with the skills, training and education to meet labour market needs (4 P/Ts)

- employee retention (3 P/Ts)

Programs and services funded through the WDAs

P/Ts employ the WDAs to offer a variety of programs and services targeting specific sectors and industries, unemployed or underemployed jobseekers, and vulnerable populations.Footnote 24

Types of programs and services funded through the agreements include:

- skills training, such as occupational skills training, short-term training, and on-the-job training (12 P/Ts)

- employer-sponsored training (12 P/Ts)

- programs and services for persons with disabilities (12 P/Ts)

- programs and services that target other vulnerable groups (such as youth, women, Indigenous peoples, newcomers, older workers or the unemployed) (10 P/Ts)

- work experience programs for unemployed or underemployed participants, such as apprenticeships, job placements, and paid work experience (10 P/Ts)

- employment assistance services, such as resume writing, job search, interview practice (10 P/Ts)

- pre-employment supports, such as literacy, basic adult education, essential skills training, and official language training (6 P/Ts)

- wage subsidies (4 P/Ts)

These programs and services are often combined to meet specific needs, such as skills training programs for specific marginalised populations. All P/Ts have contracts with third-party service providers to deliver a variety of WDA-funded program and services, including those aiming to assist specific subgroups. Some P/Ts rely on these contracts exclusively for service delivery while others employ a mixed model including direct government delivered services.

Sectors and industries targeted through the agreements

Sectors and industries targeted for labour force development through the agreements include:

- construction and manufacturing (6 P/Ts)

- services and tourism (6 P/Ts)

- communication and technology (5 P/Ts)

- health care and social assistance (5 P/Ts)

- professional and scientific (5 P/Ts)

- raw materials industries (4 P/Ts)

- transportation (4 P/Ts)

- mining and forestry (3 P/Ts)

- agriculture (fewer than 3 P/Ts)

Population subgroups targeted through the agreements

Key subgroups targeted for assistance under the agreements include:

- persons with disabilities (12 P/Ts)

- Indigenous peoples (10 P/Ts)

- newcomers and immigrants (10 P/Ts)

- youth, including at-risk youth (10 P/Ts)

- unemployed participants (9 P/Ts)

- women (7 P/Ts)

- older workers (6 P/Ts)

- Social assistance recipients (3 P/Ts)

- visible minorities (3 P/Ts)

- low-income individuals, people involved with the justice system and rural workers (Fewer than 3 P/Ts each)

Profile of 2020 to 2021 WDA participants

Nearly 132,400 individuals participated in 291,200 WDA-funded programs and services in 2020 to 2021.Footnote 25 On average, every participant took 2.2 programs and/or services. Table 2 presents the preliminary profile of participants by key socio-demographic variables. Considering the scope and the target population under the WDAs, it is noted that:

- nearly 15% of participants were older workers and 22% were youth

- persons with disabilities represent 60% of participants

- immigrants accounted for 19% of participants

- Indigenous participants accounted for 6.5% of participants

- nearly 39% of participants were employed or self-employed at the start of participation

- unemployed participants represented 47% of the total participants and 7% were out of the labour force at the start of participation

Compared to the profile of national survey respondents, it is noted that:

- persons with disabilities represent 60% of participants in 2020 to 2021 compared to 14% of the national survey respondents

- immigrants represent 19% of participants in 2020 to 2021 compared to 37% for national survey respondents

- participants with less than a high-school degree represent 27% of participants in 2020 to 2021 compared to 15% of national survey respondents

- participants with a university degree represent 6% of participants in 2020 to 2021 compared to 29% of national survey respondents

| Characteristics | % of WDA participants |

|---|---|

| Gender: Female | 50.5 |

| Gender: Male | 48.9 |

| Age: 15 to 24 | 21.7 |

| Age: 25 to 54 | 63.5 |

| Age: 55 and over | 14.7 |

| Indigenous (self-reported) | 6.5 |

| Persons with disabilities (self-reported) | 60.1 |

| Visible minorities (self-reported) | 7.6 |

| Immigrants (self-reported) | 19 |

| Marital status: Single | 58 |

| Marital status: Married or common-law | 24.7 |

| Education level: Less than high school | 27.3 |

| Education level: High school diploma or equivalent | 28.7 |

| Education level: Some post-secondary training | 4.6 |

| Education level: College or other non-university certificate or diploma | 6.4 |

| Education level: University certificate of diploma | 3.4 |

| Education level: University degree | 6.2 |

| Programs and services: Employment assistance services | 63.4 |

| Programs and services: Skills development | 26 |

| Programs and services: Targeted earnings supplements | 6.6 |

| Programs and services: Targeted wage subsidies | 1.9 |

| Programs and services: Job creation partnerships | 1.9 |

| Programs and services: Self-employment assistance | 0.2 |

| Employment status at start of action plan: Unemployed | 47.3 |

| Employment status at start of action plan: Employed | 35.6 |

| Employment status at start of action plan: Self-employed | 3.6 |

| Employment status at start of action plan: Not in the labour force | 6.9 |

*Values may not equal to 100% due to rounding or missing information.

Labour market needs of WDA participants

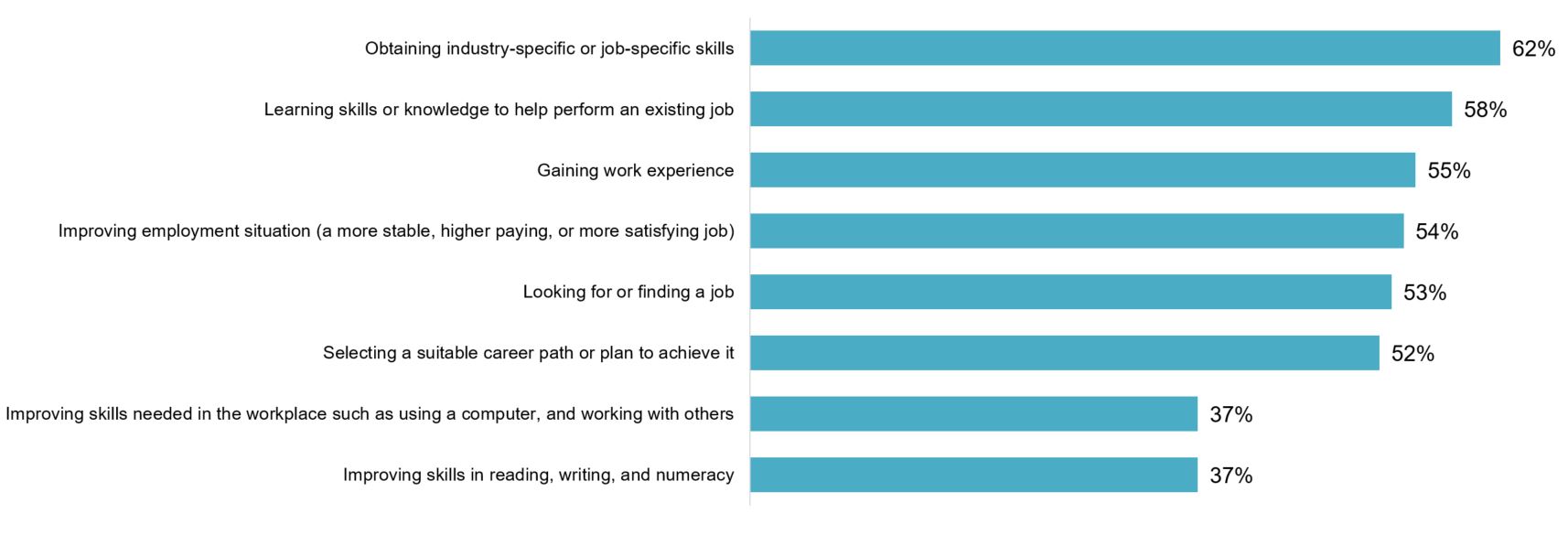

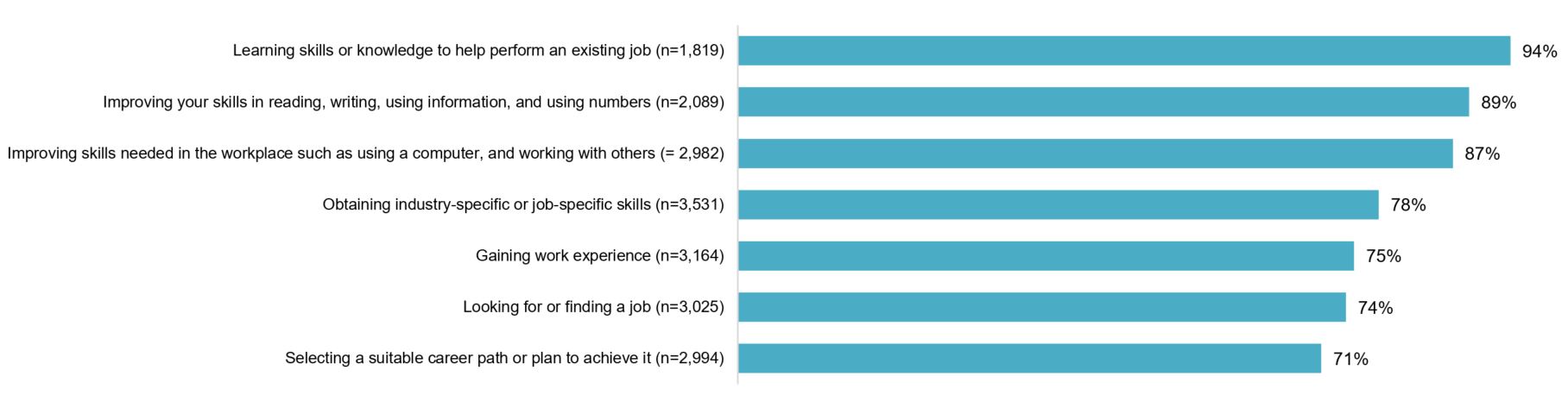

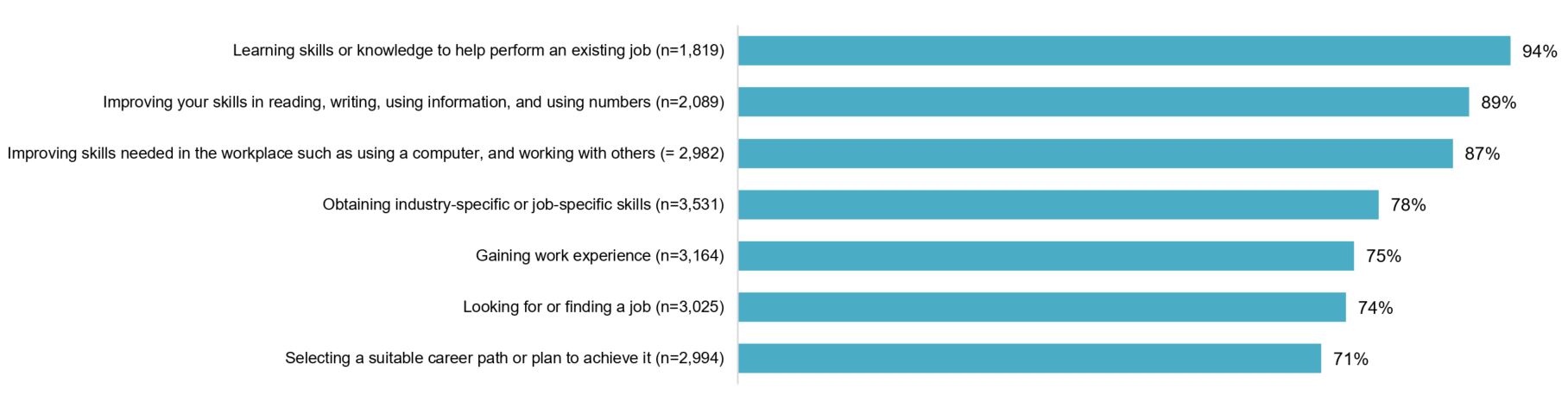

National survey respondents identified their labour market needs at the start of their WDA participation; these are presented in Chart 1. Survey respondents could select all applicable categories.

Text description – Chart 1

| Pre-participation labour market need | % of surveyed participants who reported having need |

|---|---|

| Improving skills in reading, writing, and numeracy | 37% |

| Improving skills needed in the workplace such as using a computer, and working with others | 37% |

| Selecting a suitable career path or plan to achieve it | 52% |

| Looking for or finding a job | 53% |

| Improving employment situation (a more stable, higher paying, or more satisfying job) | 54% |

| Gaining work experience | 55% |

| Learning skills or knowledge to help perform an existing job | 58% |

| Obtaining industry-specific or job-specific skills | 62% |

Programs and services provided to persons with disabilities

P/T representatives in 12 jurisdictions and 43 service providers/caseworkers who work in organizations that offer WDA-funded services to persons with disabilities across the country were interviewed. These interviews aimed to identify:

- the main challenges experienced by persons with disabilities and those who serve them

- the type of programs and services offered to them

- the best practices for supporting these participants to improve their labour market outcomes

Challenges and labour market needs experienced by persons with disabilities

Key informants identified a wide range of challenges experienced by persons with disabilities seeking entry and advancement in the labour market.

Societal attitudes

- Discrimination, stigma and lack of awareness on the part of employers and colleagues (51 key informants in 12 P/Ts)

Lack of service availability, affordability, and infrastructure

- Access to transportation (40 key informants in 12 P/Ts)

- Access to childcare (14 key informants in 9 P/Ts)

- Access to a reliable internet connection and to telecommunication technology to receive services and to participate in training and employment (6 key informants in 4 P/Ts)

Lack of accessibility supports

- Access to accessibility and accommodation supports (25 key informants in 12 P/Ts)

Poor health and wellbeing

- Mental health challenges, including trauma, and access to mental health services (17 key formants in 10 P/Ts)

- Inability to work full-time (14 key informants in 8 P/Ts)

- Low self-confidence (12 key informants in 8 P/Ts)

- Substance use (7 key informants in 6 P/Ts)

Limited work opportunities and experience

- Lack of work opportunities and tight labour market (17 key informants in 9 P/Ts)

- Lack of work experience and gaps in resume (15 key informants in 10 P/Ts)

- Maintaining employment for some persons with disabilities (5 key informants in 4 P/Ts)

Need for essential skills development and education

- Lack of social and communication skills (20 key informants in 8 P/Ts)

- Lack of employment readiness and need for more pre-employment supports and essential skills training (15 key informants in 10 P/Ts)

- Low education and/or skill level (11 key informants in 6 P/Ts)

- Fewer pre-employment and employment opportunities for persons with disabilities, increasing the challenge of the school to work transition (8 key informants in 6 jurisdictions)

- Barriers to accessing training and education for persons with disabilities (5 key informants in 5 P/Ts)

Insufficient service navigation and coordination

- Service navigation, knowing which services are available and how to access them, in a poorly coordinated and a competitive service provider environment (11 key informants in 7 P/Ts)

Poverty and vulnerability

- Poverty and low-paying jobs (11 key informants in 6 P/Ts)

- Fear of losing benefits and the security that these represent inhibits after finding employment (9 key informants in 5 jurisdictions)

Cultural and language barriers

- Cultural and language barriers impeding persons with disabilities from accessing services, obtaining employment, and maintaining employment (7 key informants in 5 P/Ts)

In the territories, person with disabilities experience additional challenges. These include living in areas with poorer service infrastructure and fewer programs and services targeted toward their distinct labour market needs. These challenges are further exacerbated for those who live in remote areas.

Subgroup-specific labour market challenges and needs of persons with disabilities

Interviewed service providers and caseworkers were asked whether participants experience different challenges and labour market needs depending on their age or gender. Most (35 out of 43) of those interviewed reported that they did.

Youth: 25 service providers/caseworkers in 10 P/Ts reported that youth with disabilities are more likely to experience the following:

- lack of work experience (15 service providers/caseworkers in 9 P/Ts)

- mental health challenges (8 service providers/caseworkers in 5 P/Ts)

- need for more pre-employment supports (8 service providers/caseworkers in 4 P/Ts)

- school-to-work transition related challenges (4 service providers/caseworkers in 3 P/Ts)

Women: 19 service providers/caseworkers in 10 jurisdictions reported that women with disabilities are more likely to experience the following:

- lack of access to childcare (12 service providers/caseworkers in 8 P/Ts)

- discrimination based on sexism, traditional gender roles, and difficulty finding employment in male dominated industries (6 service providers/caseworkers in 6 P/Ts)

- gaps in resumes due to caregiving responsibilities (3 service providers/caseworkers in 3 P/Ts)

Older adults: 17 service providers/caseworkers in 8 P/Ts reported that older adults with disabilities are more likely to experience the following:

- ageism, assumptions about older workers’ abilities and character based on their age (7 service providers/caseworkers in 3 P/Ts)

- lack of technological literacy (6 service providers/caseworkers in 5 P/Ts)

- resistance to change (5 service providers/caseworkers in 3 P/Ts)

- age related decline (4 service providers/caseworkers in 4 P/Ts)

Men: 7 service providers/caseworkers in 6 P/Ts reported that men with disabilities are more likely to experience the following:

- mental health challenges (3 service providers/caseworkers in 3 P/Ts)

- outdated skills (3 service providers/caseworkers in 3 P/Ts)

- lack of technological literacy (3 service providers/caseworkers in 3 P/Ts)

- mismatched expectations about job prospects (3 service providers/caseworkers in 3 P/Ts)

Program design and delivery responsiveness to labour market needs of persons with disabilities

Most service providers and case workers (35 out of 43) reported that persons with disabilities are more likely to experience certain challenges based on their age and gender. However, only 7 service providers/caseworkers in 5 P/Ts reported having targeted programming based on age or gender. Most of these (in 4 out of 7 organizations with targeted programming) are school to work transition programs for youth.

In general, service providers and caseworkers reported that they assess each participant and provide services based on their unique needs, challenges, and strengths. These key informants identified a variety of approaches used by their organization to achieve this objective, including:

- individual-centred approaches (35 service providers/caseworkers in 12 P/Ts)

- strength-based approaches focusing on the strengths rather than the limitations of participants (11 service providers/caseworkers in 7 P/Ts)

- disability-specific services, such as services for individuals with autism, hearing impairments, or mental illnesses (10 service providers/caseworkers in 7 P/Ts)

- holistic approaches targeting a variety of employment and non-employment related needs to improve labour market outcomesFootnote 26 (10 service providers/caseworkers in 7 P/Ts)

- accessible programs and services designed to be inclusive of all participants regardless of personal characteristics, such as disability type, age, gender, and culture (6 service providers/caseworkers in 4 P/Ts)

- trauma-informed programs and services (4 service providers/caseworkers in 3 P/Ts)

- culturally grounded services for Indigenous peoples (4 service providers/caseworkers in fewer than 3 P/Ts)

Organizations often combine several of these approaches to determine participants’ needs.

Most (38) service providers and caseworkers reported that they take the severity and nature of participants’ disability into account when designing their programs and services. They use a variety of strategies when developing programs and services, including:

- assessments (27 service providers/caseworkers in 11 P/Ts)

- employer engagement (12 service providers/caseworkers in 8 P/Ts)

- stakeholder engagement (12 service providers/caseworkers in 7 P/Ts)

- environmental scans (11 service providers/caseworkers in 8 P/Ts)

- community engagement (11 service providers/caseworkers in 7 P/Ts)

- labour market reports (11 service providers/caseworkers in 7 P/Ts)

Most (35) service providers and caseworkers reported that over 20% of the participants with disabilities served by their organization require ongoing assistance for 2 years or more. In 11 of the organizations interviewed, over 80% of participants with disabilities require ongoing assistance.

Programs and services for persons with disabilities funded through the WDAs

P/T representatives in 12 jurisdictions and 43 service providers/caseworkers were asked to identify the types of WDA-funded labour market programs and services that they provide to persons with disabilities. Service providers could not always identify the source of funding for individual programs and services. Accordingly, the services identified by service providers/caseworkers may not all be funded through the WDAs.

Table 3 presents the list of programs and services provided to persons with disabilities according to the P/T representatives and service providers/caseworkers interviewed. There are important differences between the list of programs and services identified by P/T representatives and the list provided by service providers. This can be explained partially by the use of multiple sources of funds by service providers. It is also possible that not all P/T representatives provided a complete list of WDA-funded programs and services as part of this evaluation exercise.

| Program or service | # of P/Ts (out of 12) that fund the program or service through the WDAsFootnote 27 | # of interviewed service providers (out of 43) that offer the program or service | # of P/Ts (out of 12) where service providers reported offering the program or service |

|---|---|---|---|

| Job placements | < 3Footnote 28 | 39 | 12 |

| Short-term training | N/AFootnote 29 | 37 | 12 |

| Job maintenance supports | 8 | 21 | 11 |

| Paid work experience | < 3 | 28 | 11 |

| Pre-employment supports | 5 | 23 | 11 |

| Wage subsidies | 3 | 25 | 11 |

| Literacy and essential skills training | N/A | 27 | 10 |

| Employment services | 3 | 23 | 11 |

| Skills training | 6 | 18 | 10 |

| Occupational skills training | 3 | 14 | 8 |

| Assessments | < 3 | 10 | 6 |

| Accessibility and accommodations supports | 6 | < 3 | < 3 |

| School to work supports | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Transportation supports | 4 | < 3 | < 3 |

| Employer/community education | 5 | < 3 | < 3 |

| Job development | < 3 | 5 | 3 |

| Community-based work assessments | N/A | 4 | 3 |

| Culturally grounded programs and services | N/A | 4 | < 3 |

Best practices to improve the labour market outcomes of persons with disabilities

The document review and interviews with P/T representatives and service providers/caseworkers identified a number of best practices to improve the labour market outcomes of persons with disabilities.

- Most effective service delivery approaches:

- providing services through a holistic approach (23 key informants in 12 P/Ts)

- providing services through an individual-centred approach (12 key informants in 8 P/Ts)

- comprehensively assessing participants’ employability and skills to develop individualised plans (9 key informants in 6 P/Ts)

- providing ongoing personalized services (reviewed documents of 7 P/Ts)

- collaborating with other service providers and coordinating service delivery (4 key informants in 4 P/Ts)

- Most effective labour market programs and services:

- providing job maintenance supports (22 key informants in 10 P/Ts)

- providing wage subsidies (22 key informants in 9 P/Ts)Footnote 30

- providing skills training (20 key informants in 10 P/Ts)

- providing job placements (15 key informants in 10 P/Ts)

- providing pre-employment services (11 key informants in 7 P/Ts)

- job development (11 key informants in 6 P/Ts)

- case management (5 key informants in 5 P/Ts)

- self-esteem building (5 key informants in 5 P/Ts)

- Employer education, engagement, and support:

- educating employers about hiring persons with disabilities (22 key informants in 10 P/Ts)

- conducting employer engagement activities (8 key informants in 7 P/Ts)

- providing HR type supports for employers (4 key informants in 4 P/Ts)

- Most effective supports:

- providing transportation (16 key informants in 9 P/Ts)

- providing accessibility and accommodation supports (11 key informants in 7 P/Ts)

- providing childcare supports (5 key informants in 5 P/Ts)

- Having skilled staff:

- having skilled staff to better assist persons with disabilities (8 key informants in 7 P/Ts)

Targeted services based on age and gender

Service providers and caseworkers were asked whether there were differences in terms of the programs and services that work best for persons with disabilities of different ages and genders. Most (23 service providers in 12 P/Ts) reported no differences. However, a significant minority (18 service providers in 11 P/Ts) reported that participants of different ages and genders benefit from targeted programs and services. Key informants identified targeted services for youth, older workers, women, and men.

- Youth benefit from targeted programs, such as school to work pre-employment supports (16 service provider in 10 P/Ts)

- Older workers benefit from targeted programs, such as technological literacy training support to adapt to changing workplaces (8 service providers in 7 P/Ts)

- Women benefit from targeted services to address gender specific barriers (6 service providers in 5 P/Ts)

- Men benefit from gender specific service delivery approaches (3 service providers in 3 P/Ts)

Support for employers

All jurisdictions provide WDA-funded programs and services to assist employers to address their labour market challenges and needs. In 10 jurisdictions, P/T representatives reported that employers in specific sectors and industries are targeted. These include:

- health care and social assistance (5 P/Ts)

- construction and manufacturing (4 P/Ts)

- mining and forestry (4 P/Ts)

- agriculture (3 P/Ts)

- essential services, food processing, hospitality and tourism, IT sector, oil and gas, professional and scientific services, and transportation (Fewer than 3 P/Ts each)

P/T representatives in 3 jurisdictions also reported that employers in rural and remote regions are targeted.

According to P/T representatives, the following employer needs are targeted through the WDAs:

- access to labour (6 P/Ts)

- employee training (6 P/Ts)

- employee retention (3 P/Ts)

- support to employ persons with disabilities (3 P/Ts)

- job matching (Fewer than 3 P/Ts)

The following types of programs and services are funded through the WDAs to address employers’ labour market challenges and needs:Footnote 31

- employer-sponsored training (12 P/Ts)

- job grants, financial assistance benefits, and wage subsidies (10 P/Ts)

- partnerships, employer engagement, working groups, and consultations (4 P/Ts)

- pandemic related programs to fill labour need through youth employment, training grants, and worker attraction and retention programs (Fewer than 3 P/Ts)

P/T representatives were asked whether the WDAs had been successful at assisting employers to address their labour market needs and challenges. P/T representatives in 6 jurisdictions responded that it had been successful. The other half were either unsure (5 P/Ts) or thought that the WDAs had been unsuccessful at assisting employers. In 4 jurisdictions, P/T representatives identified specific challenges that the WDAs were unable to address. Reported challenges include: improving access to labour; employer awareness of WDA-funded programs and services; and developing employer-friendly application and reporting processes (each in fewer than 3 P/Ts).

Interviewed service providers and case workers were asked about the programs and services they provide to help employers hire persons with disabilities. Thirty-three service providers and caseworkers (out of 43) reported that their organization offered services to employers. These included:

- employer education (24 service providers/case workers in 9 P/Ts)

- support with training and human resources issues (20 service providers/caseworkers in 9 P/Ts)

- wage subsidies (12 service providers/caseworkers in 9 P/Ts)

- job matching (10 service providers/caseworkers in 6 P/Ts)

- accessibility and accommodation supports (Fewer than 3 service providers/caseworkers)

Seven service providers/caseworkers in 5 P/Ts also reported that organized activities to publicly recognize employers who hire persons with disabilities.

Service providers/caseworkers identified several benefits of employer focused programs and services.

- Employee retention supports help employers to keep positions filled longer and reduces onboarding costs (20 service providers/caseworkers in 10 P/Ts)

- Employer education creates a more supportive environment for employees with disabilities (18 service providers/caseworkers in 9 P/Ts)

- Assistance with human resources issues helps employers feel supported, which lessens the perceived risks of hiring persons with disabilities (16 service providers/caseworkers in 9 P/Ts)

- Job matching services help employers to more easily access the labour they need (8 service providers/caseworkers in 6 P/Ts)

- Providing job-specific training to persons with disabilities saves employers time and resources (6 service providers/caseworkers in 4 P/Ts)

- Participants with disabilities have more opportunities to work (5 service providers/caseworkers in 5 P/Ts)

- Participants with disabilities experience pride and independence when given the opportunity to work in a supportive environment (3 service providers/caseworkers in 3 P/Ts)

Innovation

The document review identified programs and services being designed and delivered in an innovative way in 10 provinces and territories. Each of these jurisdictions reported innovation within existing programs and services. Four jurisdictions also reported developing new innovative programs and services. Innovation occurred in the following areas.

Skills training (5 P/Ts)

Examples include:

- incorporating trauma-informed pedagogy in language training programs for refugees occupation-specific skills training for refugees

- combining occupation specific training with on the job learning

Service delivery (5 P/Ts)

Examples include:

- online employment services

- programs to help offset the cost of transportation

- pilot projects to test best practices in service delivery to Indigenous participants

Education (3 P/Ts)

Examples of innovation related to education include:

- experiential co-op training to help persons with disabilities acquire transferable job skills

- using a GBA+ lens to train youth, women, immigrants, and non-binary individuals in trades-related occupations

- using experiential learning to help participants acquire the skills, experience, and support to transition into employment

Employer partnership (Fewer than 3 P/Ts)

An example includes:

- creating employment opportunities in partnership with employers to hire and train persons with disabilities

Incorporating new technologies (Fewer than 3 P/Ts)

An example includes:

- creating a mobile web application to connect recent graduates, youth, newcomers and international students with local business leaders

Uptake of the research and innovation stream

In most (7 out of 12) provinces and territories, P/T representatives reported that no projects had been undertaken under the Research and Innovation stream. Reasons provided for not doing so included the following:

- P/Ts use the Labour Market Development Agreements for Research and Innovation projects (3 P/Ts)

- research and innovation is integrated into program and service delivery (fewer than 3 P/Ts)

P/T representatives in 5 provinces and territories reported having projects funded under the Research and Innovation stream of the WDAs.

Examples of Research and Innovation Stream projects

- Housing renovation:

Funding was used to develop an innovative training program where students contributed to repairing damaged housing units. Participants acquired trades skills while improving housing quality and availability. - Modular housing:

Funding was used to develop an innovative program where students developed modular housing units, which were then shipped throughout the jurisdiction to improve housing availability. - Sub-journeyman certification:

Funding was used to pilot an innovative certification program that allows experienced trades people to be certified below the journeyman level without having to take written exams. The program seeks to address significant employment barriers for individuals with low literacy levels and learning disabilities. - Culturally grounded service delivery:

Funding was used to co-develop a culturally grounded service delivery approach with a First Nations community. The program seeks to increase engagement and employment outcomes for at-risk youth. - Service delivery model:

Funding was used to engage in a broad community consultation in order to develop a new service delivery model. The program seeks to ensure that all individuals in the jurisdiction receive the support they require to improve their labour market integration and employment outcomes.

Flexibility and responsiveness of the WDA model to workforce needs

Overall, ESDC officials and P/T representatives reported that the WDAs provided P/Ts with the flexibility needed to meet the needs of their jurisdiction. When asked about the strengths of the model, ESDC officials identified the following:

- the WDAs have strong focus on those who are more removed from the labour market

- the agreements have broad program and participant eligibility criteria

- they are adaptable to P/T policy objectives

P/T representatives in 11 out of 12 P/Ts also found the agreements to be flexible. They reported that the WDAs provide their jurisdiction with the flexibility to design and deliver employment programs and services that are adapted their respective labour market needs and priorities. In particular, P/Ts found that the WDAs:

- are more flexible than the Labour Market Development Agreements (3 P/Ts)

- allow them to cover gaps in the Labour Market Development Agreements’ program and participant eligibility criteria (Fewer than 3 P/Ts)

Challenges associated with the WDAs

ESDC representatives, P/T representatives in all jurisdictions, and most (39 out of 43) service providers/caseworkers who work with persons with disabilities identified challenges with the agreements.

Funding level and flexibilityFootnote 32

P/T representatives in all 12 jurisdictions identified the insufficient funding level as the most important challenge associated with the agreements.

ESDC officials noted the smaller budget for the WDAs compared to the Labour Market Development Agreements. It was also acknowledged that WDA participants are generally further away from the labour market and require more intensive programs and services to improve their labour market outcomes. This would suggest the need for a more even allocation of funding between the WDAs and the Labour Market Development Agreements.

P/T representatives identified a number of funding related adjustments that would improve their ability to meet current and emerging needs; these included:

- increased flexibility to fund programs and services targeting those who are further away from the labour market and who require more intensive supports (6 P/Ts)

- increasing year-to-year carryover funds (4 P/Ts)

- more flexibility to offer holistic services, including mental health services, connectivity supports and technological literacy training, life stabilization measures, and transportation supports (4 P/Ts)

- increasing the flexibility in the use of administrative funds (3 P/Ts)

P/T representatives and service providers reported that more funding is required for specific types of programs and services; these included:

- job-readiness and employment maintenance supports that reflect the resource intensive and long-term nature of serving persons with disabilities (Reported in 18 interviews, 15 with service providers and 3 with P/T representatives, in 8 P/Ts)

- transportation supports (9 service providers/caseworkers in 5 P/Ts)

- mental health supports (Reported in 8 interviews, 4 with providers/caseworkers and 4 with P/T representatives, in 3 P/Ts)

- employer education and awareness (5 service providers in 5 P/Ts)

- funding to cover the cost of criminal record checks and pardons (4 service providers in fewer than 3 P/Ts)

- life stabilization supports, such as providing food, clothing, transportation, and temporary housing (3 service providers in fewer than 3 P/Ts)

Sixteen service providers/caseworkers in 10 P/Ts who work with persons with disabilities reported that the funding level allocated to their organization is insufficient to stabilize their staff. They reported that staff turnover results in:

- a continuous loss of organizational knowledge

- increased resources needed for onboarding and training

- suboptimal service delivery

- loss of crucial relationships with the community, employers, and participants with disabilities

Nine service providers/caseworkers in 5 P/Ts reported that the lack of multi-year funding exacerbates these issues. According to these key informants, the provision of multi-year funding would significantly increase the stability of their staff and services. It would also significantly reduce the administrative burden associated with annual funding applications.

Program and service eligibility criteria unclear and inflexible

Twenty-three service providers/caseworkers in 12 P/Ts reported a lack of flexibility and clarity with respect to eligible programs and services. This hampered service providers’ ability to effectively apply for funding and to use funding in a way that best served the needs of persons with disabilities. In particular, they lacked the flexibility to respond to the needs individuals who require more intensive, holistic program design and delivery approaches.

Participant eligibility criteria

ESDC officials, P/T representatives in 6 jurisdictions, and 10 service providers/caseworkers in 6 P/Ts identified populations who are ineligible for participation in WDA-funded programs and services, these included:

- international students, temporary foreign workers, and some refugees (ESDC officials, P/T representatives in 6 jurisdictions, and 4 service providers/caseworkers in 4 P/Ts)

- employed participants (P/T representatives in 4 jurisdictions, and 4 service providers/caseworkers in 4 P/Ts)Footnote 33

- participants who are unwilling to identify as persons with disabilities, and those who do not have a formal assessment (5 service providers/caseworkers in 3 P/Ts)Footnote 34

Overall, key informant interviews revealed that there is a need to clarify the participant, program, and service eligibility criteria.

Data collection

ESDC officials, P/T representatives in 5 jurisdictions, and 10 service providers/caseworkers in 6 jurisdictions identified the data collection requirements as a barrier. According to these key informants, data collection form a barrier to both the development and delivery of programs and services to serve vulnerable populations.

P/T representatives and service providers/caseworkers also reported that the data collection provisions limit their ability to:

- serve marginalised individuals, such as those who do not have social insurance numbers or fixed addresses (P/T representatives in 3 jurisdictions, and 10 service providers in 6 P/Ts)

- serve marginalised individuals who, for a variety of reasons, are not comfortable sharing personal information (P/T representatives in 3 jurisdictions, and 10 service providers in 6 P/Ts)

- work with third-party service providers who do not have the capacity to collect, store, and report data in a timely manner (P/T representatives in 3 jurisdictions)

- maintain balance between administrative work and service delivery, because data collection and reporting is time-consuming (6 service providers/caseworkers in 3 P/Ts)

P/T representatives were asked how this barrier could be mitigated. Representatives in 4 jurisdictions suggested that more flexibility be provided to exempt some vulnerable individuals from having to provide personal information, including social insurance numbers.

Service delivery to Indigenous peoples

P/T representatives in 3 jurisdictions reported that more funding and flexibility is needed to provide intensive, culturally and linguistically appropriate supports to Indigenous participants.

Micro-credentialing

P/T representatives in 3 jurisdictions identified micro-credentialing as an existing need that is not currently funded under the WDAs in their respective jurisdictions. The relevance of micro-credential is growing given the increasingly ad-hoc nature of employment (gig economy).

Contextual challenges affecting service delivery

P/T representatives and service providers/caseworkers who provide services to persons with disabilities identified several significant challenges that affected their ability to deliver WDA-funded programs and services in their jurisdictions.

Service delivery in rural and remote areas: P/T representatives in 7 jurisdictions reported that service delivery in sparsely populated rural and remote areas remains challenging and resource intensive. This challenge is exacerbated by the lack of internet connectivity and difficult access to transportation.

Online service delivery

P/T representatives in 3 jurisdictions reported that online service delivery creates a significant barrier for individuals who:

- do not have access to communication technology