Increasing Retirement Savings in Workplace Pension Plans through Simplified Enrolment

Full title: Increasing Retirement Savings in Workplace Pension Plans through Simplified Enrolment: A Demonstration Project - Final Report, September 2018

On this page

- Executive summary

- 1. Introduction: What is the Current Situation?

- 2. Project Design: What did we do—how and why?

- 2.1. What research has been done in this area?

- 2.2. The Intervention

- 2.3. Test Groups, research questions, and outcomes of interest

- 3. Objectives: Why did we need to do this research?

- 3.1. Improving employee participation

- 3.2. Enhancing individual financial decision-making

- 3.3. Supporting Canadians as their responsibility to save for their retirement increases

- 3.4. Providing evidence for CAP sponsors and governments as savings options and regulations change.

- 4. Project Implementation: What data did we gather?

- 4.1. Recruitment of firms and randomization

- 4.2. Implementation and data collection

- 4.3. Protection of privacy and data security

- 5. Methodology: How did we analyse the data?

- 6. Results: What did we find out?

- 6.1. Does simplification and nudging prompt newly hired employees to complete pension enrollment forms (i.e. make a conscious decision about their employers plan) or not?

- 6.2. Does simplification and nudging work to increase participation rates?

- 6.3. Is there a difference between the effectiveness of simplified forms and simplified process compared to simplification alone?

- 6.4. Are new hires that use simplified forms more likely to choose a contribution rate that maximizes the employer contribution?

- 6.5. Do simplified forms result in a wider range of contribution rates?

- 6.6. What is the overall story coming from the work done?

- 7. Conclusion: Why do these results matter?

- Annex 1: Additional tables

- Annex 2: Examples of Sun Life Financial Standard Enrolment and Simplified Enrolment Forms

- Annex 3: Process Diagrams

Acknowledgements

The Research Team would like to thank the employers and employees who took part in this study.

- Kim Duxbury, Assistant Vice President, Product and Research, Group Retirement Services, Sun Life Financial.

- Hugh Kerr, Vice-president and Associate General Counsel, Sun Life Assurance

- Mazen Shakeel, Vice-president, Market Development, Group Retirement Services, Sun Life Financial.

- Louise Matta, Regional Director, Sun Life Financial

- Nicholas Meace, Manager, Small Business Centre, Group Retirement Services, Sun Life Financial

- Amina Gilani, Product Manager, Digital Enrolment, Sun Life Financial

- Tara Junker, Product Development, Digital Enrolment, Sun Life Financial

- Lori Buddle Smith, Product Manager, GRS Product Development Innovation, Sun Life Financial

- Carole Vincent, Vincent Consultation

- Karen Hall, Director General, Social Policy Directorate, Employment and Social Development Canada

- Doug Murphy, Director General, Social Policy Directorate, Employment and Social Development Canada

- Patrick Bussière, Director, Social Research Division, Employment and Social Development Canada

- Urvashi Dhawan-Biswal, Director, Innovation Lab, Employment and Social Development Canada

- John Rietschlin, Manager, Social Research Division, Employment and Social Development Canada

- Maxime Fougère, Manager, Social Research Division, Employment and Social Development Canada

- Maureen Williams, Senior Research Advisor, Social Research Division, Employment and Social Development Canada

- Sasha Koba, Research Analyst, Social Research Division, Employment and Social Development Canada

- Mathieu Audet, Senior Research Advisor, Innovation Lab, Employment and Social Development Canada

- Miroslav Kucera, Senior Research Advisor, Service Research Division, Employment and Social Development Canada

- Christopher Poole, Senior Research Advisor, Social Research Division, Employment and Social Development Canada

- Dominque Fleury, Senior Research Advisor, Social Research Division, Employment and Social Development Canada

- Renée Myltoft, Analyst, Social Research Division, Employment and Social Development Canada

- Sultan Ahmed, Research Analyst, Service Research Division, Employment and Social Development Canada

Executive summary

Many working Canadians worry that they will not have sufficient income for their retirement. The Canadian retirement income system (RIS) is robust; however, there are concerns whether some individuals are saving enough through third pillar instruments such as registered retirement savings plans (RRSPS) and employer sponsored capital accumulations plans (CAPS) including defined contribution pension plans (DCPPs), Pooled Registered Pension Plans (PRPPs), group RRSPs and deferred profit sharing plans (DPSPs). To address this challenge, a study was designed to examine the effects of restructuring the enrolment choice environment in employer sponsored CAPs by applying the precepts of behavioural economics. Four objectives guided the study: improving employee participation; enhancing individual financial decision-making; supporting Canadians as their responsibility to save for their retirement increases; and providing evidence for CAP sponsors and governments as savings options and regulations change.

Currently, newly hired employees in firms with capital accumulation plans generally can enrol once they have worked for the firm for a specified period of time, as well as meeting other criteria. Employees receive enrolment forms at eligibility, and must complete them, indicating their choice to enrol, the amount of their contribution and how their contribution will be allocated amongst the options available in their plan. Generally, no guidance is provided to complete these complex forms. With these circumstances in mind, Sun Life Financial and Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) collaborated to design two straightforward, low cost, interventions with the goal of increasing both enrolment and contribution levels.

The interventions consisted of simplifying the enrolment forms and encouraging newly hired employees to fill out forms in advance of their eligibility date. Forty-four firm worksites were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: a control group receiving a standard form and experiencing a standard process; a group receiving a simplified form but a standard process (Simplified Form Only Group); and a group receiving a simplified form and being encouraged to complete the form on hiring in advance of eligibility (Verbal Nudge Group). The firms participating in the study contributed information on 3,760 newly hired employees.

The results of the study showed that using a simplified form, either with or without a verbal nudge to complete it in advance, increased enrolment in employer sponsored CAPs; and the Simplified Form Only Group was equally likely to enrol as the Verbal Nudge Group. Looking at the likelihood of making a contribution that would attract the maximum employer match, more employees in both the Simplified Form Only Group and the Verbal Nudge Group than the control group made such a contribution. Finally, larger proportions of employees in both the Simplified Form Only and the Verbal Nudge Groups contributed higher percentages of their earnings to retirement savings.

In completing this study ESDC and Sun Life Financial have demonstrated that it is possible to significantly increase the number of individuals who save for retirement in employer sponsored plans by simplifying their enrolment forms.

1. Introduction: What is the Current Situation?

1.1. The Canadian Retirement Income System

While the first two pillars of the Canadian retirement income system (RIS), Old Age Security (including the Guaranteed Income Supplement) and the Canada Pension Plan (and its counterpart, the Quebec Pension Plan), offer the assurance that older Canadians will receive a basic minimum income and level of earnings replacement, it is the third pillar that helps many Canadian households “bridge the gap between public pension benefits and their retirement goals”.Footnote 1 These third pillar savings vehicles include individual registered retirement savings plans (RRSPs) as well as employer sponsored capital accumulation plans (CAPs) such as defined contribution pensions plans (DCPPs), Pooled Registered Pension Plans (PRPPs), group RRSPs and deferred profit sharing plans (DPSPs).

Despite the strengths of the RIS, there are concerns whether some Canadians are saving enough through third pillar instruments. While present-day seniors are generally doing well, recent studies have indicated that as many as one half of non-retired adults may be at risk of not being able to maintain their economic well-being in retirement—middle- and upper-earners being at particular risk. Moreover, there are concerns about the perceived decline in the share and the quality of private-sector pension coverage rates among younger cohorts of Canadians.Footnote 2

1.2. Sources of risk in current environment

The concerns about pension coverage amongst younger Canadians are rooted in both demographic change as well as structural transformations of the pensions saving environment. They can be summed up as follows:

- Population Aging: A combination of factors is contributing to the changing age structure of the population including increased longevity and smaller families. Increased longevity has a significant impact as the period of retirement is now likely to be longer and, to the extent that retirement savings are not annuitized, there is a greater risk of individuals outliving their financial resources.

- Delayed entry in the labour force: When compared to previous generations of young workers, today’s young Canadians tend to stay in school or college longer, and often have a non-linear approach to entering the labour market. People in their twenties may navigate between entry-level positions and higher education, before settling into career employment. Further, compared to their predecessors, today’s young Canadians are also delaying family formation and homeownership, both of which can result in postponement of wealth accumulation and personal saving.

- Declining participation in workplace pensions arrangements: Overall, there have been shifts in employment in the private sector to industries where there are lower levels of employment-related benefits. This has led to a declining coverage rate in employer- sponsored registered pension plans (RPPs).

- Shift away from defined benefit (DB) to defined contribution (DC) pension schemes: To reduce exposure risk and contain costs, private-sector employers are shifting away from defined benefit (DB) pension plans towards capital accumulation retirement savings plans. And while DB plans still cover most pension plan participants, membership has declined in recent years. In Canada, just over 4,380,000 employees were in defined benefit pension plans in 2014, down 0.5% from 2013 and down 8.3% from a high of 4,776,000 in 1992.Footnote 3 This decline is more pronounced in the private sector where DB coverage between 2002 and 2012 has fallen from 73% to 48%.Footnote 4 Further, where DB plans exist in the private sector, many are not open to new employees. In contrast, as of 2014, just over one million Canadians have DC pension plans with more having access to other savings plans in the workplace, such as Group RRSPs and Deferred Profit Sharing Plans.

In this changing environment, almost half of middle-income Canadians are not covered by either an RPP or have an RRSPFootnote 5; and of those who have only RRSPs, saving levels are likely to be inadequate unless there is an additional employer match.Footnote 6 This has significant implications for Canadian’s standard of living in retirement, with approximately two-thirds of households currently saving at levels that will not generate sufficient income to cover their non-discretionary expenses: half of middle-income earners born between 1945 and 1970 would see a decline of at least 25% in their standard of living.Footnote 7 And some groups are more vulnerable than others: households with no RPP coverage and single individuals are considerably more likely than other groups to accumulate less retirement wealth than those with more optimal levels of saving.

It is this context that provided the incentive to examine the potential beneficial effects of simplified enrolment schemes in facilitating retirement saving decisions and improving participation in employer-sponsored pension plans. A systematic examination of such enrolment has the benefit of evaluating options and has important implications for the design of future plans. The study involved multiple employers and various industries, and is to our knowledge, the first large-scale randomized experiment looking at enrolment behaviours in Canada or elsewhere in the world.Footnote 8

This report presents the final results of the project. It also describes the project design, recruitment of plan sponsor (employer) participants, enrolment simplification, and implementation of the field experiment.

2. Project Design: What did we do—how and why?

Currently, newly hired employees in firms with capital accumulation plans (CAPs) can generally enrol once they have worked for their firm for a specified period of time, as well as meeting other criteria. Under existing practices, employees receive enrolment forms at eligibility, making an active choice to enrol, indicating the amount of their contribution and how their contribution will be allocated amongst the fund options available in their plan. Generally, no guidance is provided to complete these complex forms. Even though funds may grouped between “Built for Me” and “Built by Me” categories, the investment decision is often complex. It can involve selecting funds with many competing choices, as well as deciding how much to allocate to each different fund, sometimes using an asset allocation tool that may be included in their enrolment package as a guide (See Annex 2 for an example of a standard enrolment form). With these circumstances in mind, Sun Life Financial and Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) worked together to design two straightforward, low cost, interventions with the goal of increasing both enrolment and contribution levels.

2.1. What research has been done in this area?

The project design was driven by research on financial literacy and behavioural economics as well as a review of similar investigations undertaken in a methodology report prepared by ESDC. A feasibility study carried out by Social Research and Demonstration Corporation (SRDC) also contributed to the design.Footnote 9

Evidence from research on financial literacy indicates that a substantial proportion of the Canadian population lack basic numeracy skills and knowledge of fundamental financial principles. Keown (2011), in an analysis of the first cycle of the Canadian Financial Capability Survey (CFCS 2009), showed that this phenomenon is closely linked to both income and demographic characteristics such as educationFootnote 10: those with a high school diploma or less scored lower on the test that made up part of the survey than those with higher levels of education. Analysis of the second cycle of the CFCS (2014) found that Canadian’s level of financial knowledge was effectively unchanged from 2009.Footnote 11

Studies have also shown that individuals commonly engage in behaviours that can negatively affect their long-term financial well-being such as procrastination, inertia, naïve diversification, excessive risk-taking, and under-saving. But perhaps more importantly, evidence suggests that financial decisions are often shaped in large part by the way choices are offered and presented, and that uncertainty about potential saving options and the perceived consequences of making wrong choices influence some individuals to postpone, or avoid, investment decisions altogether.Footnote 12

In this context, simplified enrolment processes are seen as a promising way to enhance participation and coverage in workplace retirement savings plans. The literature indicates that such processes, as well as automatic enrolment, have been effective in raising participation rates in the United States and elsewhere. However, there are issues to look at when designing an effective enrolment system, particularly when individual’s decision-making about contribution levels and asset allocation are considered.

Substantial evidence indicates that people are influenced by decision framing and default choices, and a number of schemes have been designed to “nudge” people into increasing their savings. Using choice framing, these schemes have been shown to influence people’s choices with regards to the decisions they have to make: whether to enroll in a given retirement saving plan (participation), what percentage of income to put into the retirement saving plan (contribution rate), and when offered, which investment options to choose (investment allocation). One study focused on simplification was shown to increase enrolment at a preselected contribution rate by about 16 percentage points.Footnote 13 Another indicated that design and default options matter when looking at how investors choose. For example, when employees are allowed to choose contribution rates, they tend to cluster around multiples of 5%; the maximum rate offered by the plan; and/or the rate that maximizes the amount contributed by the employer (Hewitt 2002).Footnote 14

Overall, there is a well-developed international body of work showing positive results for both automatic and active-choice environments. However, while this work certainly has relevance, the Canadian retirement income system itself, as well as Canadian individuals and households, face specific circumstances and challenges requiring the development of appropriate solutions.

Following an assessment of research options, it was proposed to undertake interventions focussed on simplified enrolment processes combined with a choice of contribution rate. Further, as reliable evidence as to an intervention’s effectiveness (i.e. simplified enrolment procedures) requires a comparison of outcomes of interest (i.e. coverage rates in workplace pension savings plans) with outcomes in the absence of the intervention (counterfactuals) random assignment is necessary. Random assignment minimizes the likelihood of selection bias; increasing the probability that participants in the control group and those receiving the intervention share the same observable and unobservable characteristics. It also ensures that all groups will not differ systematically. Under experimental designs such as these, any difference in outcomes between the groups following the intervention being tested can thus be attributed to the intervention.

For this study, participating firm worksites were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: a control group where the standard processes (as described above) remain unchanged and two test groups receiving the simplified enrolment intervention.Footnote 15

2.2. The Intervention

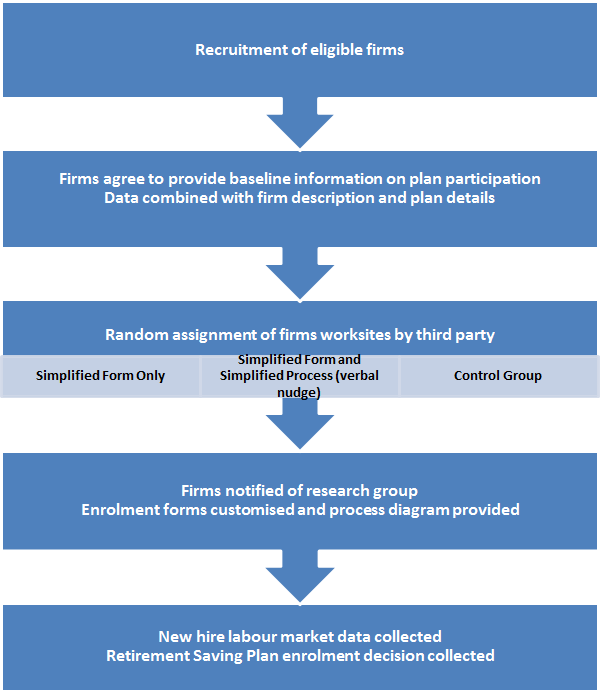

The interventions modified the design of pension plan enrolment forms and process that Sun Life Financial provides to plan sponsors with two areas of simplification being developed for the study: simplified forms and a simplified process—a verbal nudge (see Figure 1).

Customized simplified forms were developed for, and approved by, each plan sponsor (see Annex 2 for examples). Using these, new hires who wished to enroll still needed to make an active decision about how much to contribute. However, the contribution decision was presented in a simplified manner, incorporating the parameters of the savings plan and the specific requirements of the plan sponsor. In most cases, a range of contribution percentages was presented where the contribution rate attracting the maximum employer match was highlighted. The decision about which investment option to choose was also greatly simplified: new employees were informed that investments would be allocated to the plan’s default fund, unless they indicated otherwise. Employees were advised to review the other investment options available and were encouraged to assess the different options based on their risk profile. There were small variations in the way these instructions were conveyed.

Text description of Figure 1

The figure is a series of steps, described here as a list:

- Recruitment of eligible firms

- Firms agree to provide baseline information on plan participation

- Data combined with firm description and plan details

- Random assignment of firms worksites by third party

- Simplified Form Only

- Simplified Form and Simplified Process (verbal nudge)

- Control Group

- Firms notified of research group

- Enrolment forms customised and process diagram provided

- New hire labour market data collected

- Retirement Saving Plan enrolment decision collected

The simplified process, or verbal nudge took into account the likelihood that new hires were influenced both by the types of choices offered (i.e. simplified versus standard enrolment forms) but also by different contexts in which these choices were offered. New hires, as potential enrollees, may receive an orientation session, a mail-out, or may be contacted online or through an in-person one-on-one meeting with a human resource representative from their employer. Further, decisions may be affected by the presence, or not, of a deadline for making that decision. Amongst Sun Life plan sponsors, the standard practice is to give new hires pension plan enrolment forms close to the time at which they become eligible to enroll in the plan (typically between the first day of employment and six months following the date they were hired). In order to simplify the enrolment process, new hires were presented with a simplified enrolment form and were strongly encouraged to complete it at the same time they completed other payroll- and benefits-related forms typically provided. To ensure that the implementation of the simplified process was consistently applied, each worksite was provided with a process diagram showing when the form should be distributed and specifying the text (or script) to use.

Box 1: Script for verbal nudge to be used by employers

There are a number of forms that we'd like you to complete today for payroll to get you up and running in our benefits and retirement savings plan. We strongly encourage you to complete this paperwork today. The new hire package we've provided also includes all of the additional details about the plans. If, after you review the material about the Company's retirement savings plan in particular, you decide that you'd like to make some changes, it's easy enough to do and instructions are included in your package.

2.3. Test Groups, research questions, and outcomes of interest

The study compared three conditions, a control group and two test groups. The groups received the interventions as follows:

Control Group:

- Standard Form: Employees decide on contribution rates (no guidance given) and must select funds from various investment allocations options offered by the employer’s plan

- Standard Process (no verbal nudge): Once eligible for their employer’s plan, employees complete the forms at their convenience.

Simplified Form Only Group:

- Simplified Form: Employees choose from a list of contribution rates (highlighting the rate attracting the maximum employer match). Investments are allocated in a default fund.

- Standard Process (no verbal nudge): Once eligible for their employer’s plan, employees complete the forms at their convenience.

Verbal Nudge Group:

- Simplified Form: Employees choose from a list of contribution rates (highlighting the rate attracting the maximum employer match). Investments are allocated in a default fund.

- Simplified Process, a verbal nudge: Regardless of when they become eligible for the employer’s plan, employees are strongly encouraged to complete the enrolment form upon hiring.

There were five research questions that the study sought to address:

- Question 1:

Are employees who are presented with a simplified enrolment form more likely, on average, to enroll in a workplace pension plan than those employees who are presented with a standard enrolment form?

Outcome of interest: Simplified Form Only enrolment compared to Control Group enrolment.

- Question 2:

Are employees who are presented with a simplified enrolment form and are strongly encouraged to complete their enrolment form upon hiring more likely, on average, to enroll in a workplace pension plan than those employees who are presented with a simplified enrolment form but are told, as is the standard practice, that they can complete the enrolment form at their convenience?

Outcome of interest: Verbal Nudge Group enrolment compared to Simplified Form Only Group enrolment.

- Question 3:

Are employees who are presented with a simplified enrolment form and are strongly encouraged to complete their enrolment form upon hiring more likely, on average, to enrol in a workplace pension plan than those employees who are presented with a standard enrolment form and are told, as is the standard practice, that they can complete the enrolment form at their convenience?

Outcome of interest: Verbal Nudge Group enrolment compared to Control Group enrolment.

- Question 4:

Are employees who are presented with a simplified enrolment form more likely, on average, to choose the contribution rate that maximizes the amount contributed by the employer than those employees who are presented with a standard enrolment form?

Outcome of interest: Maximization of both groups receiving the simplified form compared to Control Group maximization.

- Question 5:

Are employees who are presented with a simplified enrolment form more likely to exhibit wider-ranging contribution rates, as a group, than those employees who are presented with a standard enrolment form?

Outcome of interest: Distribution of test groups’ contribution percentages compared to distribution of Control Group contribution percentages.

3. Objectives: Why did we need to do this research?

As described in the Introduction, demographic, labour market and RIS changes in Canada have long term implications for future seniors’ income security. Consequently, answering the research questions will provide evidence to: improve participation in employer-sponsored retirement savings plans; ease and enhance individual financial decision making related to saving for retirement; provide evidence for CAP sponsors and governments as savings options and regulation change; and, more generally, improve the long-term economic well-being of individuals and households, particularly among those at risk of lowered income in retirement.

3.1. Improving employee participation

By assessing the effectiveness of simplified enrolment systems, this study aims to help Canadian employers adopt “best practices” in terms of developing appropriate and effective retirement savings plans. Savings plan sponsors have an interest in supporting employees to prepare for their retirement, specifically those who may currently be under saving by not enrolling in available voluntary employer plans or by contributing an amount less than that which maximizes the employer matching contribution. This is particularly relevant for Canadians who have been shown to have lower levels of financial knowledge overall and who may be less likely to invest. While this group includes young adults, recent immigrants and Canadians living in households with low income or low net-worth, it should be noted that financial knowledge and behaviours associated with longer term decision making are also challenging for some middle income earners.Footnote 16

3.2. Enhancing individual financial decision-making

For common behavioural challenges such as choice overload, procrastination and under-saving, simplified enrolment processes may improve both decision-making and the execution of financial preparations for retirement which, in turn, have the potential to improve long-term economic well-being for individuals and households. As noted above, the increasing complexity of the financial system along with a number of behavioural tendencies often combine to hinder or negatively affect individual financial decision making. Simplified enrolment systems are important because they have the potential to help Canadians make “better” financial decisions while respecting their individual rights and freedom to make their own decisions.

3.3. Supporting Canadians as their responsibility to save for their retirement increases

Simplified enrolment may also help Canadians take on more responsibility for their own retirement. The ongoing shift in the private sector away from DB pension towards savings based retirement vehicles such as DC pensions, group RRSPs and, more recently, TFSA’s as well as the more targeted role of elements of the public pensions (such as OAS and GIS) means that tomorrow’s seniors will increasingly need to take on more responsibility for their own retirement. Supporting the ability of individuals to make prudent savings decisions in preparing for their retirement is of strategic importance to the Canadian government as improved income adequacy enhances Canadians’ well-being and has the potential to reduce pressures on public pensions and other income supports over the longer term.

3.4. Providing evidence for CAP sponsors and governments as savings options and regulations change.

Finally, simplified enrolment is important to explore because many of the recent changes in the labour market and the retirement income system in Canada over the past several years are likely to have long term implications. Changes made now are likely to take time to realize any full effect, and it is important for Canada’s RIS to evolve and adapt today in order to appropriately address the new challenges and emerging needs not only of today’s seniors but also of tomorrow’s.

4. Project Implementation: What data did we gather?

4.1. Recruitment of firms and randomization

With the project launched, recruitment of plan sponsors took place between November 2013 and November 2015. This phase was undertaken by Sun Life Financial and proved to be challenging in terms of criteria needed to participate and the subsequent discussions required to ensure accurate implementation of the intervention at study sites.

Several criteria were used to guide recruitment so as to reduce variation amongst the sample of participant firms:

- Voluntary participation to DC plan or Group RRSP: The employer offers eligible employees the possibility of voluntarily participating into a workplace pension plan (no mandatory participation).

- Average employers’ matched contribution: Employers’ matched contribution rates are in the 3%-6% average.

- Average eligibility period: Eligibility to enrolment in the pension plan is given to employees within three to six months of their hiring date.

- Stability: There were no significant changes to workplace pension-plan design in the past few years and none expected in the foreseeable future.

- Openness to change: The plan sponsors/firm is planning on changing enrolment procedures or options within a year or is open to making changes to its enrolment procedures or options.

- Paper enrolment only: Enrolment into the plan is done through paper forms (no online enrolment).

- Adequate system for data collection: The employer has set up a system that will provide reliable information on firm’s own characteristics but more importantly on all new hires that are eligible for pension plan participation.

Additionally, efforts were also focused on ensuring a cross-section of industry type, geographical location and firm size, to enable the results to be more widely applicable.

As groups of plan sponsors were recruited into the study, each was assigned a unique identification number; for firms with multiple work sites, a further numerical identifier was added. These numbers were then linked to the basic data of each plan and the study group assignment. They also ensured that the participant firms remained anonymous to the research team. The task of randomization was undertaken by a third party.

4.2. Implementation and data collection

Following the recruitment and randomization, research team members worked with firms to revise and simplify forms, and to ensure that the intervention was implemented. Support was provided to ensure that firm participants did not experience any additional administrative burden. Data on each specific plan was collected including key information on pension-plan design such as the length of time before an employee becomes eligible to enroll in the plan, the type of plan (defined-contribution plan, group retirement savings plan or a combination of both), the type of default investment fund (when applicable), the employer’s contribution formula (e.g. employer’s matching rate, employer’s maximum contribution) and the employee’s allowable contributions (e.g. minimum and maximum contribution percentages and amounts).

Information on each participating firms’ new hires was also collected. At the time of hiring, each new employee was assigned a unique anonymous identification number, which was then used to link the employee’s basic information, as provided by their employer, with information about their employers. This data was also linked to subsequent key outcomes of interest: whether new hires enroll in the workplace pension plan, how much they contribute (contribution rate and dollar amount), and how much their employer contributes (contribution rate and dollar amount).

Finally, information was collected at the firm level to capture the extent to which employers and plan sponsors engage in proactive practices to inform new hires about the advantages of pension plan enrolment. These would normally be done through regular employee workshops on pension, benefits and retirement planning, or other types of communication.

4.3. Protection of privacy and data security

ESDC and Sun Life adhere to the highest standards of handling and storing confidential data, employing the appropriate security technologies and procedures to help protect participants’ personal information from unauthorized access, use, or disclosure.

As described previously, each participating firm or worksite and each participating employee was assigned a unique, anonymous identification number. This ensured privacy as, before being securely shared with ESDC, all detailed personal data was stripped from the analysis file. All information collected through the study was stored on computer systems located in controlled facilities with access restricted to the research team. All files containing study data were further password protected.

5. Methodology: How did we analyse the data?

Data were collected from 44 firm worksites in all Canadian provinces and territories with the exception of Yukon.Footnote 17 The final sample collected consisted of 3,760 new hires (498 new hires were dropped from the data set to conform to the study requirement that each work site contribute a maximum of 300 employees). The Simplified Form Only Group contributed the largest share of new hires (39 percent), while the Verbal Nudge Group and the Control Group were similar in size (31 percent and 30 percent of the total sample, respectively). Employee contribution percentages ranged from 0 percent to 13 percent, with only 5 percent of new hires contributing more than 6 percent to a pension plan.

5.1. Variables

Guided by the research questions, the following variables were used.

- Outcome Variable 1: Decision making was generated from employee decisions to contribute or not contribute to a pension plan, and is a dichotomous variable.

- Outcome Variable 2: Contributed to a pension plan was generated from employee contribution percentages and is a dichotomous variable.

- Outcome Variable 3: Employer match percentage selected was generated from employee and employer contribution percentages. This variable is dichotomous and is defined as the employee percentage matching the employer maximization percentage, or not.Footnote 18

- Control Variables: Seven demographic characteristics were included in this analysis as control variables: sex, year of birth, marital status, work tenure, annual salary, firm size, and maximum employer match percentage.

- The sample of new hires was primarily male (70%).

- Year of birth was coded into five, ten year categories: born in 1950 or before to born in 1990 or later. The largest proportion of new hires were born between 1980 and 1989 (32 percent) and between 1970 and 1979 (25%).

- 70 percent of the sample reported being married, and

- 92 percent were working full-time at the time of data collection.

- Annual salary was coded into 5 categories: 1) less than $40,000, 2) $40,000 - $59,999, 3) $60,000 – $ 79,999, 4) $80,000 - $99,999, and 5) $100,000 or more per year. Employees who did not have an annual salary, but earned an hourly wage were all full time employees. Thus, hourly wage was multiplied by 2080 (annual full time hours) to yield their annual salary. The majority of employees earned between $60,000 and $79,999 per year (33%).

- Firm size was categorized as small, medium or large. Small firms are comprised of fewer than 100 total employees, medium sized firms employ between 100 and 500 employees and large firms employee over 500 employees. 298 (8%) newly hired employees were hired by small firms, 1,380 (37%) were hired by medium sized firms, and 2,082 (55%) were hired by large firms.

- Employer matching percentage rates ranged from 2% - 8%. The largest proportions of employees were employed by firms matching up to 4% (39% of employees), 6% (23% of employees), and 5% (20% of employees).

Although data regarding Province/ Territory of residence were collected, they were not included in this analysis because of concentrations of employees in Ontario and Quebec; 51 percent of new hires reported living in Ontario while 28 percent reported residing in Quebec.

5.2. Descriptive and empirical analysis

Logistic regression and subsequent average marginal effects were initially used to answer the research questions one, two, three, and four.Footnote 19 Recognising, however, that there were limitations to the randomization of the employee sample, subsequent mixed effect logistic regression models were also run. Results from both modelling techniques are largely the same (i.e. in the case of decision making), however, mixed effect models produced estimates which took into account differences in groups at the firm level. Descriptive statistics were used to explore the distributions of contribution percentages to determine if there were differences between the test groups and the Control Group.

6. Results: What did we find out?

6.1. Does simplification and nudging prompt newly hired employees to complete pension enrollment forms (i.e. make a conscious decision about their employers plan) or not?

Answering this question provides an assessment of the effectiveness of simplified forms (Simplified Forms Only Group), and simplified forms and process (Verbal Nudge Group) in influencing the rates of decision making when faced with the option of enrolling in a pension savings plan over that of standard enrolment (Control Group). In this case, making any decision regarding enrolment, whether yes or no (including contributing 0%), is considered positive. The analysis provides insight into employee’s behaviour in that any active choice is compared to a passive negative response (non-completion). This latter group may include individuals who do not complete enrolment forms for many reasons: because they are not interested in contributing to a pension plan (e.g. due to having other savings vehicles in place or perhaps having other financial needs); because they are affected by inertia, procrastination or choice-overload; or because they simply forget.

Average marginal effects (without control variables) are reported from logistic regression models (mixed effect models did not produce estimates) regarding making a decision about pension plan enrolment. These results show that individuals in the Simplified Form Only Group are 15 percent more likely to make a decision compared to the Control Group. Individuals in Verbal Nudge Group are 27 percent more likely to make a decision regarding pension plan enrolment, compared to the Control Group.

When controlling for sex, year of birth, work tenure, marital status, annual salary, firm size, and maximum employer match percentage, average marginal effects from mixed effect models indicate that compared to those in the Control Group, individuals in the Simplified Form Only Group are 26 percent more likely to make a decision regarding pension plan enrolment, while those in the Verbal Nudge Group are 29 percent more likely to make a decision. These findings suggest that simplifying the enrolment process and encouraging employees to complete forms at the time of hiring has a strong positive effect on their likelihood to make a decision regarding pension plan enrolment.

6.2. Does simplification and nudging work to increase participation rates?

This addresses research questions 1 and 3: do simplified forms (Simplified Forms Only Group), and simplified forms and process (Verbal Nudge Group) function to increase participation rates (i.e. choosing a positive contribution amount) over that of standard enrolment (Control Group).

Average marginal effects (without control variables) for contributing to a pension plan show that individuals in the Simplified Form Only Group are 17 percent more likely to contribute to a pension plan compared to the Control Group. Individuals in Verbal Nudge Group are also 17 percent more likely to contribute to a pension plan, compared to the Control Group.

When controlling for sex, year of birth, work tenure, marital status, annual salary, firm size, and maximum employer match percentage, average marginal effects indicate that compared to those in the Control Group, individuals in the Simplified Form Only Group are 24 percent more likely to contribute to a pension plan, while those in the Verbal Nudge Group are 25 percent more likely to contribute. These findings suggest that simplifying the enrolment process and encouraging employees to complete forms at the time of hiring has a positive effect on their likelihood to enroll in a pension plan.

6.3. Is there a difference between the effectiveness of simplified forms and simplified process compared to simplification alone?

This addresses research question 2: is there a difference in enrolment between the Simplified Form Only Group and the Verbal Nudge Group.

Average marginal effects (without control variables) for contributing to a pension plan show that individuals in the Verbal Nudge Group do not differ from those in the Simplified Form Only Group in their likelihood to contribute to a pension plan. This does not differ even when controlling for sex, year of birth, work tenure, marital status, annual salary, firm size, and maximum employer match percentage,. This finding provides evidence to suggest that the simplified enrolment process is no more effective with the additional ‘verbal nudge’ (encouragement to complete the form).

6.4. Are new hires that use simplified forms more likely to choose a contribution rate that maximizes the employer contribution?

Research question 4 is answered using two outcome variables. First, the outcome of selecting the exact percent that maximizes the employer match contribution is analyzed. This match percentage is bolded on forms and is paired with a written indication of employer maximum match. Second, the outcome of selecting or exceeding the employer maximizing contribution percentage is analyzed. This second outcome is analyzed because those who exceed the employer contribution maximum still receive the maximum benefit from their employer. However, it is necessary to analyze the selection of the exact maximizing percentage to evaluate the effectiveness of the experimental design and simplification of forms.

Employer Maximization Match

Average marginal effects (without control variables) show that individuals in the Simplified Form Only Group are 22 percent more likely than the Control Group to select the contribution percentage that maximizes their employers’ contribution. Individuals in the Verbal Nudge Group are 26 percent more likely than the Control Group to maximize their employers’ contribution.

When controlling for sex, year of birth, work tenure, marital status, annual salary, firm size, and maximum employer match percentage, average marginal effects show that individuals in the Simplified Only Group are 30 percent more likely to maximize employer contribution, while those in the Verbal Nudge Group are 29 percent more likely. These findings suggest that simplifying the enrolment process and providing an explanation of employer matching leads to greater likelihood of selecting the maximizing percentage. It is also interesting to note that there is no statistically significant difference between the Simplified Form Only Group and the Verbal Nudge Group. This finding suggests that while providing information about employer matching on the enrolment form is beneficial, encouraging employees to fill the form out at the time of hiring does not further increase the likelihood of enrolment.

Exceeding Employer Maximization Match

Average marginal effects (without control variables) indicate that individuals in the Simplified Form Only Group do not differ from the Control Group in likelihood of selecting or exceeding the contribution percentage that maximizes their employers’ contribution. Individuals in the Verbal Nudge Group also do not differ from the Control Group to maximize or exceed their employers’ contribution.

When controlling for sex, year of birth, work tenure, marital status, annual salary, firm size, and maximum employer match percentage, average marginal effects show that individuals in either the Simplified Form Only Group or the Verbal Nudge Group do not differ from the Control Group in their likelihood of maximizing or exceeding employer contribution.

Matching or exceeding results are considerably different than matching the exact employer maximizing percentage. This finding indicates that in the simplified form, bolding the employer maximizing percent and providing a written indication of the benefits leads to increased selection of that contribution option. However, the reason for non-statistically significant results when considering matching or exceeding employer match rates is unclear.

Graph 1 shows the proportion of employer match rates at the employee level for each group. Given that the Control Group comprises many firms who have a low match rate (close to 50% of employees have a match rate of 3% or below), it may simply be easier for employees to exceed their employers contribution. Conversely, the test groups have higher proportions of employees whose firm matches at 5% or above (Over 50% of the Simplified Form Only Group and nearly 50% of the Verbal Nudge Group) making it more difficult for employees to exceed their employer maximum contribution. Additionally, over half of employees in the Verbal Nudge Group work for a firm whose maximum contribution is 4%, compared to 37% of the Simplified From Only Group and 26% of the Control Group.

Text description of Graph 1

| Test group | 2% | 3% | 4% | 5% | 6% | 7% | >= 8% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 17% | 29% | 26% | 19% | 8% | 0% | 0% |

| Simplified Form Only | 1% | 8% | 37% | 25% | 27% | 1% | 1% |

| Verbal Nudge | 2% | 1% | 52% | 14% | 32% | 0% | 0% |

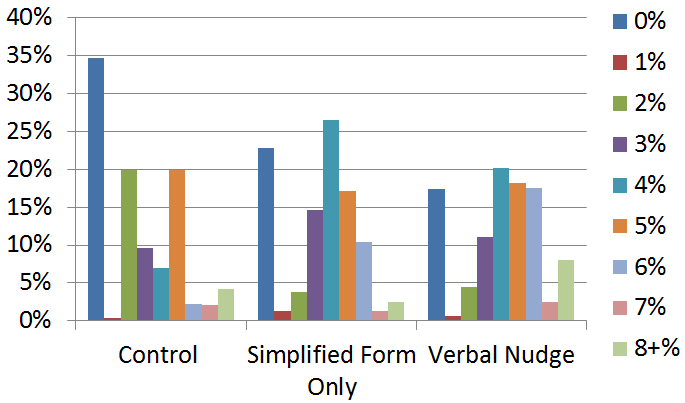

6.5. Do simplified forms result in a wider range of contribution rates?

Question 5 investigates whether individuals have a wider range of preferred contribution rates not necessarily aligning with the highlighted maximum employer match.

Graph 2 illustrates the differences in the distribution of employee contribution percentages between the test groups and the Control Group. First, 35% of those in the Control Group contributed 0% to a pension plan, compared to 23% of the Simplified Form Only Group and 17% of the Verbal Nudge Group. This figure includes individuals who did not respond or make a decision regarding retirement savings. A considerably larger proportion of employees in the Control Group contributed 2% than did those in the test groups (20%, and less than 5% respectively). Conversely, larger proportions of the test groups than the Control Group contributed 3% or 4%. Proportions of employees who contributed 5% are fairly consistent across all groups (20% of the Control Group, 17% of the Simplified Form Only Group and 18% of the Verbal Nudge Group). Finally, larger proportions of the test groups contributed over 5% compared to the Control Group, with especially high proportions of 6%, 8% or more in the Verbal Nudge Group. These differences could partially be attributed to the differences in employer match percentages outlined in Graph 1. However, it is possible that the differences are also a result of simplified enrolment processes (verbal nudges) and forms, or of underlying characteristics of the employees in all of groups.

Text description of Graph 2

| Test group | 0% | 1% | 2% | 3% | 4% | 5% | 6% | 7% | 8+% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 35% | 0% | 20% | 10% | 7% | 20% | 2% | 2% | 4% |

| Simplified Form Only | 23% | 1% | 4% | 15% | 27% | 17% | 10% | 1% | 2% |

| Verbal Nudge | 17% | 1% | 4% | 11% | 20% | 18% | 17% | 3% | 8% |

6.6. What is the overall story coming from the work done?

The results from the empirical analysis show that both simplifying the enrolment form and pairing it with a simplified process ‘verbal nudge’ increases the number of Canadians who will have retirement savings. The simplified enrolment form without the ‘verbal nudge’ is also effective in increasing the number of Canadians who will maximize their employers’ contribution percentage.

However, simplifying the enrolment form without including a simplified process ‘verbal nudge’ is more effective in increasing the number of Canadians who will have retirement savings. Simplifying the enrolment form without an associated ‘verbal nudge’ is also more effective in increasing the number of Canadians who will maximize their employers’ contribution percentage.

The contrary effect of the ‘verbal nudge’ may be caused by several circumstances experienced by the new hires, amongst others:

- Reduced time available for employees to make a decision to the point that some employees opt not to contribute at that time. Additionally, the ‘verbal nudge’ could limit time available for employees to process the information to the point of not selecting the percentage that maximizes their employer’s contribution.

- Reduced comfort level of new hires being required to fill out paperwork in a supervised setting to the point of opting not to contribute at that time. Furthermore, it is possible that employees are not comfortable maximizing their employers’ contribution while supervised.

- An environment of information overload in which employees are not able to properly evaluate the benefits of enrolling in a pension plan or maximizing their employer’s contribution at that time.

Based on our results, simplifying the enrolment form was more effective in helping Canadians save for their retirement and maximize their employers’ contributions to their retirement savings compared to simplifying the form and adding a ‘verbal nudge’ or maintaining the current enrolment process.

Nevertheless, our results also indicate that requiring new hires to fill out the enrolment at the time of hiring reduced the number of individuals who did not contribute to retirement savings (See Graph 2). Thirty-five percent of individuals in the control group chose not to contribute to a pension plan, whether their decision was passive (no form returned) or a conscious ‘No’. The proportions of individuals in the test groups that chose not to contribute to retirement savings was considerably lower, with 23 percent of the Simplified Form Only Group and 17 percent of the Verbal Nudge Group not enrolling. This pattern suggests that some individuals in the Control Group who passively did not contribute to a pension plan will select a percentage contribution other than 0 if the form is simplified, or they are required to fill out the form. This finding provides further support of the overall benefits to Canadians of simplifying enrolment processes.

7. Conclusion: Why do these results matter?

The Simplified Enrolment Demonstration Project is one of the first, and possibly the largest, field study of its kind to have been completed in Canada. It has taken place during a period when there is increasing government and industry interest in behavioural interventions. Within the Federal government, departments are exploring how knowledge of Canadians behaviour and preferences can improve programs and services. On the industry side, more Canadian companies are using behavioural approaches to understanding their client’s reactions and decision-making as they interact with products and service-offerings. Clearly, behavioural approaches are seen as an integral part of improving both citizen and client experience.

At the beginning of this research collaboration, ESDC and Sun Life Financial identified several goals:

- Improve employee participation

- Enhance individual financial decision-making

- Support Canadians as their responsibility to save for their retirement increases

- Provide evidence for plan sponsors and governments as savings options and regulations change.

The results of the study clearly indicate that there are significant opportunities to improve employee participation in savings plans offered by their employers, and further, that the effort needed to achieve this improvement is relatively small. The implementation phase of the study showed that forms can be simplified and remain aligned with plan sponsor needs. Looking to future developments, the principles of simplification used in this study could be applied to e-forms and web-based solutions.

One of the benefits that comes with this increased ease of decision making is that a greater proportion of employees are likely to make an active decision about the opportunity that their employers provide. And for these Canadians, the decision to participate means that they will have retirement savings. Further, enrolment in their employer sponsored retirement saving plan represents an important opportunity for Canadians to learn about how the Canadian RIS as a whole will work for them.

In providing evidence that the proportion of employees enrolling in retirement savings plans can be increased, the Simplified Enrolment Project also illustrates that it is possible to support Canadians to make decisions in their best interest. While, the first two pillars of the Canadian RIS are designed to provide a base income for seniors in retirement, the third pillar—individual savings—has the potential to contribute meaningfully to Canadian’s well-being in their senior years. For middle income Canadians employed in sectors where employer sponsored plans are available, taking the opportunity to save is central to maintaining their standard of living in retirement.

The final goal of the study was to contribute solid evidence for both industry and government. An aging population means that there is ongoing pressure on the Canadian RIS. Equally, the current economic environment of low interest rates has increased the need for Canadians to save more in order to ensure a secure retirement. These changes have prompted responses in all sectors: there have been modifications to both the Canadian Pension Plan and Old Age Security; provincial governments have introduced regulations enabling automatic enrolment in certain circumstances; and the financial sector has continued to innovate and provide leadership. Working collaboratively to complete this study, Sun Life Financial and ESDC have added new and valuable knowledge that will contribute to the ongoing development of the Canadian Retirement Income System.

Annex 1: Additional tables

| Details | Count % of the total | Total 3,760 |

Simplified Form Only Group 1,465 39.0 |

Verbal Nudge Group 1,179 31.4 |

Control Group 1,116 29.7 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | ||

| Number of new hires | < 10 | 34 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 21 | 1.8 | 13 | 1.2 |

| 10-100 | 1088 | 28.9 | 325 | 22.2 | 273 | 23.2 | 490 | 43.9 | |

| > 100 | 2638 | 70.2 | 1140 | 77.8 | 885 | 75.1 | 613 | 54.9 | |

| Industry | Agriculture, forestry, fishing, etc. | 128 | 3.4 | 11 | 0.8 | 17 | 1.4 | 100 | 9 |

| Mining, quarrying, oil extraction, etc. | 770 | 20.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 346 | 29.4 | 424 | 38 | |

| Utilities | 50 | 1.3 | 50 | 3.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Construction | 12 | 0.3 | 12 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Finance and insurance | 598 | 15.9 | 300 | 20.5 | 46 | 3.9 | 252 | 22.6 | |

| Accommodation and food services | 299 | 8.0 | 299 | 20.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Manufacturing | 1,222 | 32.5 | 278 | 19.0 | 756 | 64.1 | 188 | 16.9 | |

| Retail trade | 419 | 11.1 | 407 | 27.8 | 12 | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Real estate and rental | 85 | 2.3 | 85 | 5.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Professional, scientific, and technical services | 89 | 2.4 | 11 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 78 | 7 | |

| Educational Services | 18 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 18 | 1.6 | |

| Transportation and warehousing | 62 | 1.7 | 12 | 0.8 | 2 | 0.2 | 48 | 4.3 | |

| Other Services | 8 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 0.7 | |

| Province of Residence | NL | 47 | 1.3 | 2 | 0.1 | 33 | 2.8 | 11 | 1.1 |

| PE | 5 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.2 | |

| NS | 53 | 1.4 | 7 | 0.5 | 33 | 2.8 | 13 | 1.2 | |

| NB | 38 | 1.0 | 13 | 0.9 | 20 | 1.7 | 5 | 0.5 | |

| QC | 1,046 | 27.8 | 572 | 39.0 | 184 | 15.6 | 290 | 26 | |

| ON | 1,923 | 51.2 | 711 | 48.5 | 810 | 68.7 | 402 | 36 | |

| MB | 43 | 1.1 | 13 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.1 | 29 | 2.6 | |

| SK | 114 | 3.0 | 5 | 0.3 | 8 | 0.7 | 101 | 9.1 | |

| AB | 264 | 7.0 | 92 | 6.3 | 29 | 2.5 | 143 | 12.8 | |

| BC | 189 | 5.0 | 49 | 3.3 | 23 | 2.0 | 117 | 1.5 | |

| NT | 2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| NU | 35 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 35 | 3.0 | 0 | 0 | |

| US | 1 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Gender | Female | 1,147 | 30.5 | 672 | 45.9 | 274 | 23.4 | 201 | 18 |

| Male | 2,613 | 69.5 | 793 | 54.1 | 905 | 76.8 | 915 | 82 | |

| Year of birth | 1959 or earlier | 219 | 5.8 | 57 | 3.9 | 109 | 9.3 | 53 | 4.8 |

| 1960-1969 | 657 | 17.5 | 220 | 15.0 | 272 | 23.1 | 165 | 14.7 | |

| 1970-1979 | 934 | 24.8 | 315 | 21.5 | 327 | 27.8 | 292 | 26.2 | |

| 1980-1989 | 1,202 | 32.0 | 431 | 29.4 | 349 | 29.6 | 422 | 37.8 | |

| 1990 or later | 748 | 19.9 | 442 | 30.2 | 122 | 10.4 | 184 | 16.5 | |

| Marital status | Unmarried | 1,131 | 30.1 | 566 | 38.6 | 244 | 20.7 | 321 | 28.8 |

| Married | 2,628 | 69.9 | 899 | 61.4 | 935 | 79.3 | 794 | 71.2 | |

| Unknown | 1 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Work tenure | Part time | 293 | 7.8 | 291 | 19.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.1 |

| Full time | 3,467 | 92.2 | 1,174 | 80.1 | 1,179 | 100.0 | 1,114 | 99.8 | |

| Annual Earnings | < $40,000 | 495 | 13.2 | 376 | 25.7 | 105 | 8.9 | 14 | 1.25 |

| $40,000 - $59,999 | 835 | 22.2 | 259 | 17.7 | 302 | 25.6 | 274 | 24.6 | |

| $60,000 - $ 79,999 | 1,224 | 32.6 | 425 | 29.0 | 338 | 28.7 | 461 | 41.3 | |

| $80,000 - $99,999 | 872 | 23.2 | 303 | 20.7 | 330 | 28.0 | 239 | 21.4 | |

| >= $100,000 | 334 | 8.9 | 102 | 7.0 | 104 | 8.8 | 128 | 11.5 | |

| Worksite size | Large | 2,082 | 55.4 | 1,287 | 87.9 | 139 | 11.8 | 656 | 58.8 |

| Medium | 1,380 | 36.7 | 34 | 2.3 | 1,004 | 85.2 | 342 | 30.7 | |

| Small | 298 | 7.9 | 144 | 9.8 | 36 | 3.1 | 118 | 10.6 | |

| Maximum employer match percentage | 2% | 220 | 6 | 21 | 1.4 | 21 | 1.9 | 178 | 17.4 |

| 3% | 426 | 11.8 | 119 | 8.1 | 7 | 0.6 | 300 | 29.3 | |

| 4% | 1,396 | 38.5 | 540 | 36.9 | 592 | 52 | 264 | 25.8 | |

| 5% | 715 | 19.7 | 362 | 24.7 | 154 | 13.5 | 199 | 19.4 | |

| 6% | 840 | 23.2 | 402 | 27.4 | 360 | 31.6 | 78 | 7.6 | |

| 7% | 12 | 0.3 | 12 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8% | 18 | 0.5 | 9 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.4 | 5 | 0.5 | |

| Detail | Decision Making | Pension Enrolment | Maximization | Maximization or Greater |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Group | N = 3,760 | N = 3,760 | N = 3,627 | N = 3,627 |

| Simplified Form Only Group vs. Control |

0.154*** | 0.115*** | 0.225*** | -0.010 |

| Verbal Nudge Group vs. Control |

0.270*** | 0.173*** | 0.162*** | -0.118*** |

| Simplified Form Only Group vs. Verbal Nudge Group |

0.116*** | 0.058*** | -0.063*** | -0.108*** |

*P<.05 **P<.01 ***P<.001, Reference category in parenthesis. Average marginal effects presented in table

| Detail | Decision Making | Pension Enrolment | Maximization | Maximization or Greater |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Group | N = 3,558 | N = 3,596 | N = 3,626 | N = 3,626 |

| Simplified Form Only Group vs. Control |

0.258*** | 0.187*** | 0.311*** | -0.004 |

| Verbal Nudge Group vs. Control |

0.287*** | 0.096*** | 0.119*** | -0.108*** |

| Simplified Form Only Group vs. Verbal Nudge Group |

0.029* | -0.090*** | -0.192*** | -0.104*** |

| Gender (Female) | ||||

| Male | -0.023* | -0.011 | 0.033 | 0.047*** |

| Year of Birth (<=1959) | ||||

| 1960-1969 | 0.009 | 0.020 | 0.031 | -0.034 |

| 1970-1979 | -0.021 | 0.006 | 0.058 | -0.058 |

| 1980-1989 | -0.051 | -0.062 | -0.058 | -0.162*** |

| >=1990 | -0.082* | -0.139*** | -0.184*** | -0.270*** |

| Marital status (Unmarried) | ||||

| Married | 0.028 | 0.046* | 0.047* | 0.026 |

| Work Tenure (Part Time) | ||||

| Full Time | 0.077* | 0.305*** | 0.007 | -0.306*** |

| Annual Earnings (>$40,000) | ||||

| $40,000-$59,999 | 0.057 | 0.019 | 0.112*** | 0.178*** |

| $60,000-$79,999 | 0.095** | 0.159*** | 0.102*** | 0.090* |

| $80,000-$99,999 | 0.075* | 0.063 | 0.116*** | 0.248*** |

| >$100,000 | 0.087* | 0.074 | 0.124*** | 0.130* |

| Firm Size (Large) | ||||

| Medium | 0.094*** | 0.018 | 0.072*** | -0.005 |

| Small | -0.036 | 0.064* | 0.284*** | 0.172*** |

| Employer Match (2%) | ||||

| 3% | -0.153*** | -0.285*** | -0.486*** | -0.226*** |

| 4% | -0.027 | -0.055 | -0.280*** | -0.216*** |

| 5% | -0.024 | -0.170*** | -0.152*** | -0.268*** |

| 6% | -0.211*** | 0.006 | -0.207*** | -0.244*** |

| 7% | N/A | N/A | -0.210 | -0.229 |

| 8% | N/A | N/A | -0.654*** | -0.870*** |

*P<.05 **P<.01 ***P<.001, Reference category in parenthesis. Average marginal effects presented in table

| Detail | Decision Making | Pension Enrolment | Maximization | Maximization or Greater |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Group | N = 3,760 | N = 3,760 | N = 3,627 | N = 3,627 |

| Simplified Form Only Group vs. Control |

N/A | 0.172+ | 0.217** | 0.018 |

| Verbal Nudge Group vs. Control |

N/A | 0.167+ | 0.262** | 0.110 |

| Simplified Form Only Group vs. Verbal Nudge Group |

N/A | -0.005 | -0.063*** | -0.008 |

+ P< 0.1*P<.05 **P<.01 ***P<.001, Reference category in parenthesis. Average marginal effects presented in table

| Detail | Decision Making | Pension Enrolment | Maximization | Maximization or Greater |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Group | N = 3,596 (39 worksites) |

N = 3,596 | N = 3,626 (41 worksites) |

N = 3,626 (41 worksites) |

| Simplified Form Only Group vs. Control |

0.267*** | 0.236* | 0.302*** | 0.066 |

| Verbal Nudge Group vs. Control |

0.287*** | 0.053** | 0.290*** | 0.044 |

| Simplified Form Only Group vs. Verbal Nudge Group |

0.020 | 0.017 | 0.010 | -0.022 |

| Gender (Female) | ||||

| Male | -0.009 | -0.006 | 0.010 | 0.030* |

| Year of Birth (<=1959) | ||||

| 1960-1969 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.015 | -0.035 |

| 1970-1979 | -0.023+ | -0.007 | 0.037 | -0.046+ |

| 1980-1989 | -0.036* | -0.037+ | -0.022 | -0.104*** |

| >=1990 | -0.048** | -0.096*** | -0.148*** | -0.217*** |

| Marital status (Unmarried) | ||||

| Married | 0.010 | 0.005 | 0.032+ | 0.013 |

| Work Tenure (Part Time) | ||||

| Full Time | -0.032+ | -0.076 | -0.153 | 0.020 |

| Annual Earnings (>$40,000) | ||||

| $40,000-$59,999 | -0.009 | 0.070* | 0.167*** | 0.207*** |

| $60,000-$79,999 | 0.005 | 0.118** | 0.204*** | 0.095* |

| $80,000-$99,999 | 0.016 | 0.194*** | 0.273*** | 0.325*** |

| >$100,000 | 0.001 | 0.185*** | 0.257*** | 0.245*** |

| Firm Size (Large) | ||||

| Medium | 0.098+ | 0.058 | 0.002 | -0.076 |

| Small | 0.040 | 0.099 | 0.101 | 0.040 |

| Employer Match (2%) | ||||

| 3% | -0.162 | -0.144 | -0.494*** | -0.126 |

| 4% | 0.021 | -0.008 | -0.398** | -0.272** |

| 5% | -0.004 | -0.151 | -0.172 | -0.312*** |

| 6% | -0.205** | 0.114 | -0.303** | -0.232** |

| 7% | N/A | N/A | -0.303 | -0.374 |

| 8% | N/A | N/A | -0.728*** | -0.914*** |

+P<0.1 *P<.05 **P<.01 ***P<.001, Reference category in parenthesis. Average marginal effects presented in table

Annex 2: Examples of Sun Life Financial Standard Enrolment and Simplified Enrolment Forms

| Contributions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Select your contribution preferences. | My Basic contribution (1% to 6% per pay) ADDITIONAL contribution (above 6% per pay) |

|

| Investment instructions | ||

Choose funds from one or more of the following investment approaches. Percentages must be in whole numbers and total 100%. Pick from any of the funds listed on this form to build your own portfolio that matches your Investment Risk Profile. |

I request Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada to allocate contributions to the plan as follows. This instruction applies to all future contributions: |

|

| built BY me | Percentage allocation |

|

| SLA 5 Year Guaranteed Fund (060) | % | |

| Sun Life Financial Money Market Segregated Fund (GM3) | % | |

| Sun Life Financial Universal Bond Segregated Fund (SZ9) | % | |

| Beutel Goodman Balanced Segregated Fund (DRD) | % | |

| CC&L Group Canadian Equity Segregated Fund (HNT) | % | |

| BlackRock U.S. Equity Index Segregated Fund (DMQ) | % | |

| MFS International Equity Segregated Fund (PCE) | % | |

| Total | 100% | |

If the total % does not equal 100%, or this information is not completed, Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada reserves the right to invest the difference/total in the default fund chosen for the plan by your plan sponsor, which is the Beutel Goodman Balanced Segregated Fund. |

||

| Contributions upon enrolment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Employer contributions: Under your pension plan, ABC Inc. will match any contributions you make at a rate of 50 cents per dollar up to a maximum of 3% of your annual salary. Contributing at least to this match level allows you to benefit fully from employer contributions. |

|||||

| Select your contribution preferences. | Your contributions: I authorize my employer to deduct the following percentage of my pay to be deposited into the DCPP: |

||||

Full Employer Match |

|||||

| For enrolment in the plan, please also complete sections 1 to 4 of this form. | Investment allocation upon enrolment: The BlackRock Target Date fund closest to but not exceeding your 65th birthday will be used as the default investment option when you are enrolled in the plan. This fund is provided as a temporary investment option at enrolment and you are encouraged to assess different options based on your risk profile. Refer to your mymoney@work guide for full details and to complete your Investment Risk Profile. |

||||

| If you do not wish to be enrolled and do not wish to contribute to the plan at this time, check and sign here. | |||||

Employee name |

Employee identification number |

||||

Employee signature |

Date (yyyy-mm-dd) |

||||

| Contributions upon enrolment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Employer contributions: ABC Inc. will contribute 3% of your annual salary until you have 5 years of service and then ABC Inc. will contribute 5% of your annual salary. Contributing at least to this match level allows you to benefit fully from employer contributions. |

|||||

Your contributions: I authorize ABC Inc. to deduct 3% of my pay as my basic required contribution to the RSP component of the Employee Saving Plan, increasing to 5% of my pay when I have 5 years of service. |

|||||

Additional voluntary contributions: You may increase your retirement savings by making additional voluntary contributions to either the RSP or the DCPP, or to both. It is your responsibility to ensure that you do not contribute more than your allowable maximum. Your RRSP allowable maximum contribution is reported by the Canada Revenue Agency on your income tax notice of assessment. When determining how much you will contribute to the Retirement Savings Plan you must remember to consider contributions to other RRSPs or to spousal RRSPs. To determine your contribution limit under the DCP, contact ABC Inc. |

|||||

| Select one or both options for your additional voluntary contributions | |||||

Investment allocation upon enrolment: The BlackRock Target Date fund will be the default investment option when you are enrolled in the plan. This fund is provided as a temporary investment option at enrolment and you are encouraged to assess different options based on your risk profile. Refer to your mymoney@work guide for full details and to complete your Investment Risk Profile. |

|||||

| If you do not wish to be enrolled and/or do not wish to contribute to the Employee Savings Plan at this time, check the applicable box and sign here. | |||||

Employee name |

Employee identification number |

||||

Employee signature |

Date (yyyy-mm-dd) |

||||

| Contributions upon enrolment | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Contribution options |

Employer contributions: ABC Inc. will match your required contribution to a maximum of 9% as shown in the following table. |

|||||||||||

| If you contribute 3% 4% 5% 6% |

ABC Inc. will contribute 3% 4.6% 6.25% 9% |

Total contribution 6% 8.6% 11.25% 15% |

||||||||||

Your contributions: Required contributions As a member of the plan you are required to contribute an amount between 3% and 6% of your eligible earning. Contributing at least to this match level allows you to fully benefit from your employer’s contributions. If you do not make an election, your contribution will be defaulted to 6%. I authorize my employer to deduct the following percentage of my pay to be deposited into the DCPP: |

||||||||||||

Full Employer Match | ||||||||||||

Additional voluntary contributions You may increase your retirement savings by making additional voluntary contributions to the DCPP. It is your responsibility to ensure that you do not contribute more than your allowable maximum. To determine your contribution limit under the DCP, contact ABC Inc. I authorize my employer to deduct the following percentage of my pay to be deposited into the DCPP. I understand that this additional contribution will not be matched by my employer. | ||||||||||||

| For enrolment in the plan, please also complete sections 1 to 4 of this form. | Investment allocation upon enrolment: The BlackRock Target Date fund closest to but not exceeding your 65th birthday will be used as the default investment option when you are enrolled in the plan. This fund is provided as a temporary investment option at enrolment and you are encouraged to assess different options based on your risk profile. Refer to your mymoney@work guide for full details and to complete your Investment Risk Profile. |

|||||||||||

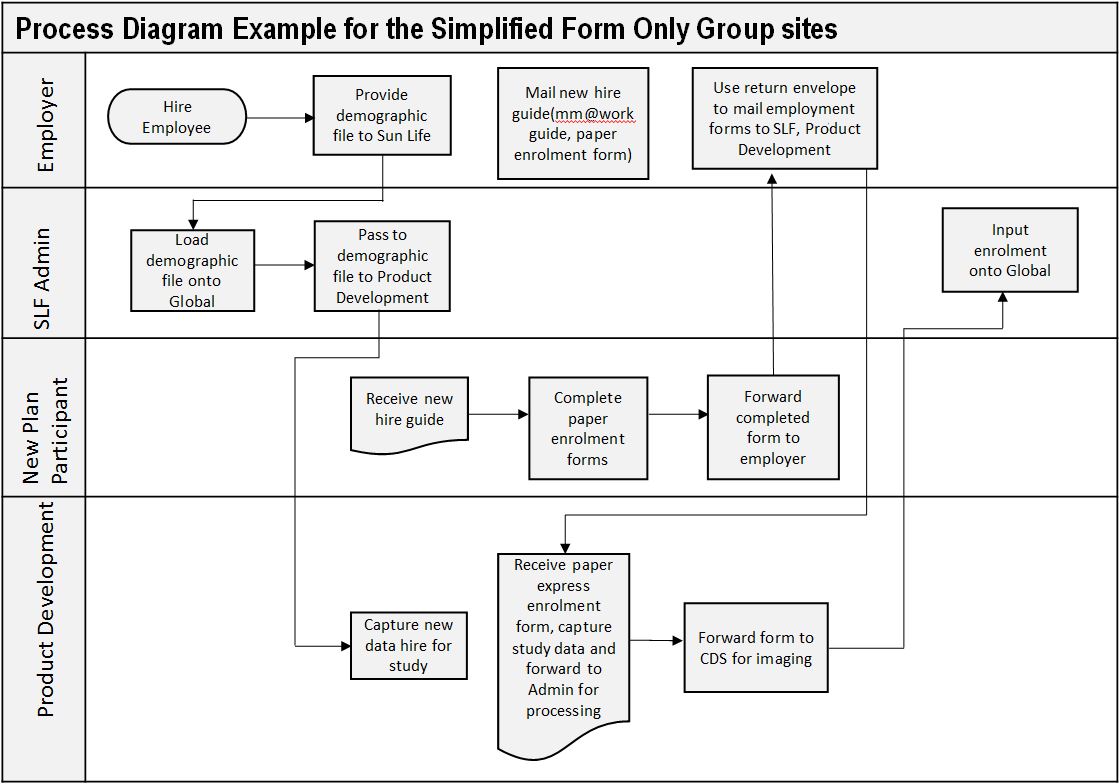

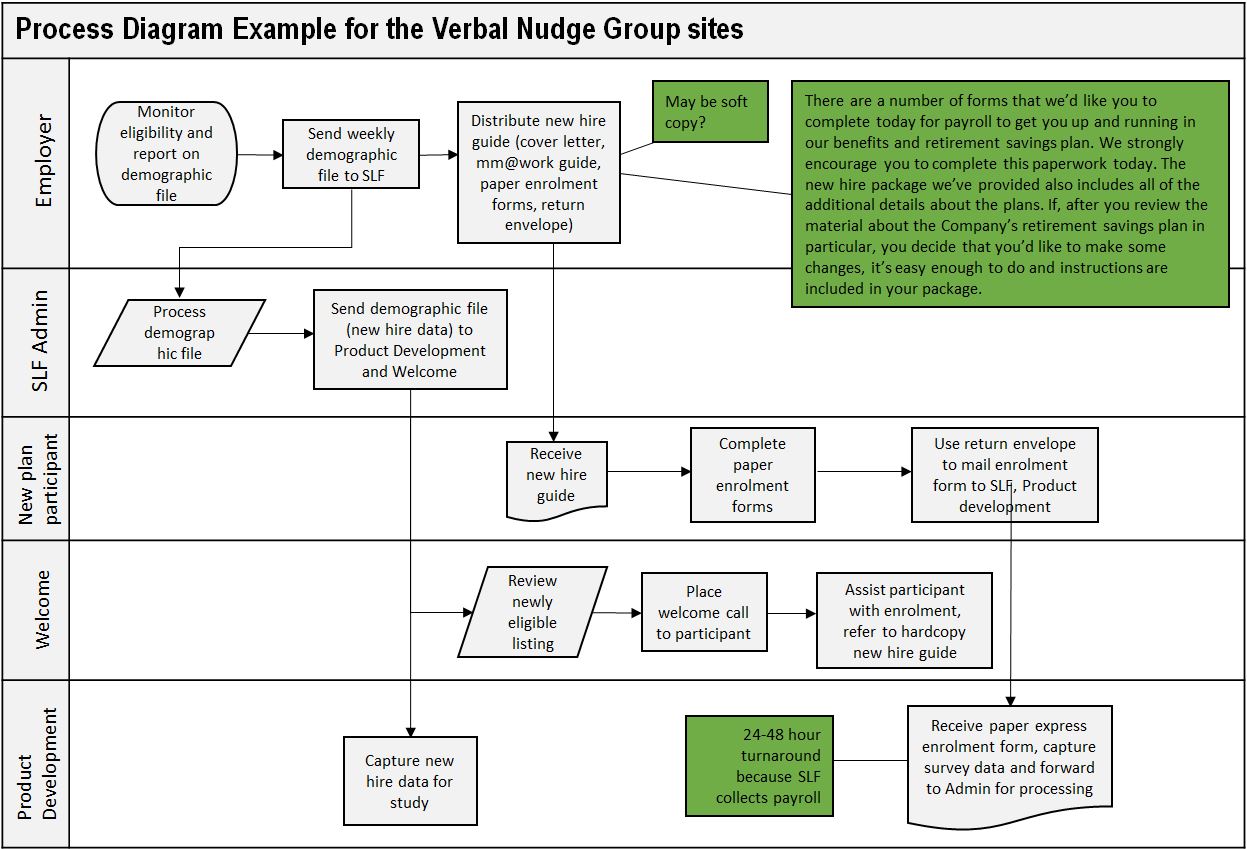

Annex 3: Process Diagrams

Process guidelines for the Simplified Form Only Group focused on the transfer of information on new hires and the timing of enrollment, taking in to account the eligibility period. Process guidelines for the Verbal Nudge Group focused on the transfer of information on new hires, and highlighted the additional task of encouraging enrollment on the first day of work. The text to be used is included on the process diagram. Process guidelines for the Control group described the existing process at the project site. The focus was on the transfer of information on new hires, and ensuring that enrollment decisions were communicated to Sun Life Financial.

Text description of Figure 3.1

The figure is a series of four flow charts across four lanes representing different stakeholders, which are:

- Employer

- SLF Admin

- New plan participant

- Product development

At each step in the chart, arrows point forward to one or more boxes. Here the flow chart is described as lists in which the possible next steps are listed beneath each box label. When a step falls into a different lane, it will be described in parentheses. When a step has more than one possible next step, they are listed beneath it.

The first chart starts in the Employer lane and has the following steps:

- Hire employee

- Provide demographic file to SLF

- (SLF Admin) Load demographic file onto Global

- Pass demographic file to product development

- (Product development) Capture new hire data for study

The second chart is a single step in the Employer lane and has the following steps:

- Mail new hire guide - mm@work guide, paper enrollment form

The third chart starts in the New plan participant lane and has the following steps:

- Receive new hire guide

- Complete paper enrollment forms

- Forward completed form to employer

- (Employer) Use return envelope to mail enrolment form to SLF, Product development

- (Product development) Receive paper express enrolment form, capture study data and forward to admin for processing

- Forward form to CDS for imaging

- (SLF Admin) input enrolment into Global

The fourth chart starts in the Product development lane and has the following steps:

- Email address on file?

- If yes, pull email address and email study survey to participant

- If no, mail hardcopy study survey to participant

- (New plan participant) Complete study survey and send / mail to SLF, Product development

- (Product development) Capture results for study

Text description of Figure 3.2

The figure is a set of two flow charts across five lanes representing different stakeholders, which are:

- Employer

- SLF Admin

- New plan participant

- Welcome

- Product development

At each step in the chart, arrows point forward to one or more boxes. Here the flow chart is described as lists in which the possible next steps are listed beneath each box label. When a step falls into a different lane, it will be described in parentheses. When a step has more than one possible next step, they are listed beneath it.

The first chart starts in the Employer lane and has the following steps:

- Monitor eligibility and report on demographic file

- Send weekly demographic file to SLF

- Distribute new hire guide - cover letter, mm@work guide, paper enrolment forms, return envelope. This may be a soft copy.

- (SLF Admin) Process demographic file

- Distribute new hire guide - cover letter, mm@work guide, paper enrolment forms, return envelope. This may be a soft copy. The cover letter says “There are a number of forms that we’d like you to complete today for payroll to get you up and running in our benefits and retirement savings plan. The new hire package we’ve provided also includes all of the additional details about the plans. If, after you review the material about the Company’s retirement savings plan in particular, you decide that you’d like to make some changes, it’s easy enough to do and instructions are included in your package.

- (New plan participant) Receive your new hire guide

- Complete paper enrolment forms

- Use return envelope to mail enrolment form to SLF, Product development

- (Product development) Receive paper express enrolment form, capture survey data and forward to Admin for processing. 24-48 hour turnaround because SLF collects payroll.

- (SLF Admin) Process demographic file

- Send demographic file (new hire data) to Product development and Welcome

- (Welcome) Review newly eligible listing

- (Product development) Capture new hire data for study

- (Welcome) Review newly eligible listing

- Place welcome call to participant

- Assist participant with enrolment, refer to hardcopy new hire guide.

The second chart starts in the Product development lane and has the following steps:

- Email study survey to participant

- (New plan participant) Complete study survey and send/mail to SLF, Product development

- (Product development) Capture results for survey.

Text description of Figure 3.3

The figure is a set of two flow charts across four lanes representing four different stakeholders, which are:

- Employer

- SLF Admin

- New plan participant

- SLF Product development