Enabling older adults to age in community

From: Federal/Provincial/Territorial Ministers Responsible for Seniors Forum

On this page

- Introduction

- Assessing the issues and gaps to aging in place

- Integrating housing and community supports

- Emerging trends

- Social isolation and the COVID-19 pandemic

- Recommendations for action

- Conclusions

- References

- Appendix 1: A summary of key findings from the Report on Housing Needs of Seniors (Puxty et al., 2019)

- Appendix 2: A summary of key findings from the Report on Core Community Supports to Age in Community (Carver et al., 2019)

- Appendix 3: A summary of key findings from the Report on Social Isolation among Older Adults during the Pandemic (Wister and Kadowaki, 2021)

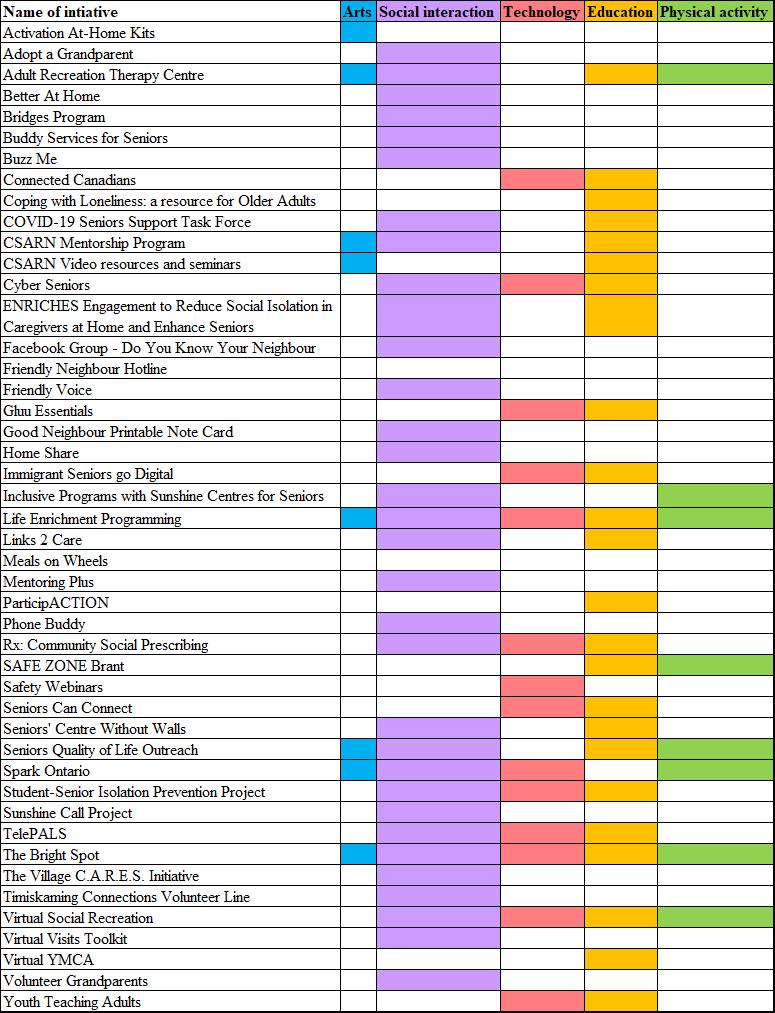

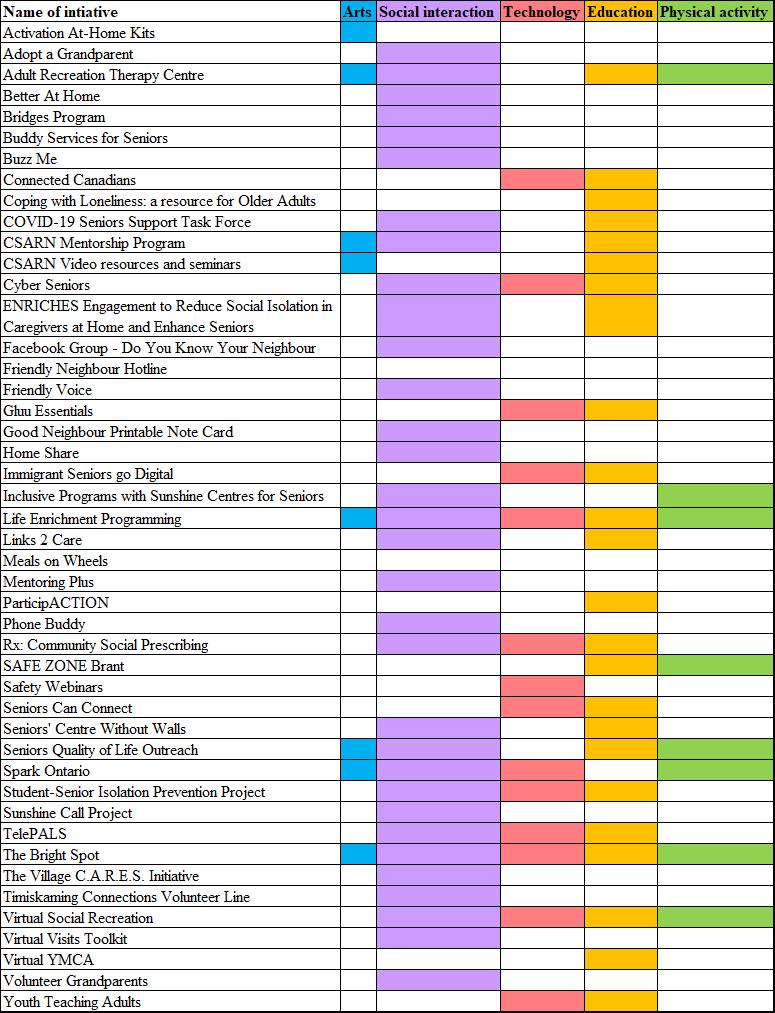

- Appendix 4: Canadian examples of community programming initiatives aimed at mitigating the negative effects of social isolation or loneliness in older adults

- Glossary

Alternate formats

Enabling Older Adults to Age in Community [PDF - 1.1 KB]

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

List of abbreviations

- CMHC

- Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation

- COVID-19

- Coronavirus disease of 2019

- FPT

- Federal, Provincial and Territorial

- GSS

- General Social Survey

- LGBTQ2

- Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (or questioning), and 2-Spirit

- LGBTQ+

- Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (or questioning) and other identities

- LHIN

- Local Health Integration Network

- LTC

- Long-term care

- NCE

- Networks of Centres of Excellence

- NORCs

- Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities

- NORC-SSP

- Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities with an integrated Supportive Services Program

- NOS

- National Occupancy Standards

- PTs

- Provinces and territories

- SCWW

- Senior Centre Without Walls

Participating governments

- Government of Ontario

- Government of Québec*

- Government of Nova Scotia

- Government of New Brunswick

- Government of Manitoba

- Government of British Columbia

- Government of Prince Edward Island

- Government of Saskatchewan

- Government of Alberta

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Government of Northwest Territories

- Government of Yukon

- Government of Nunavut

- Government of Canada

* Québec contributes to the Federal, Provincial and Territorial Seniors Forum by sharing expertise, information and best practices. However, it does not subscribe to, or take part in, integrated federal, provincial, and territorial approaches to seniors. The Government of Québec intends to fully assume its responsibilities for seniors in Québec.

Acknowledgements

Prepared by Professor Mark W. Rosenberg, Dr. John Puxty, and Professor Barbara Crow Queen’s University Network of Aging Researchers for the Federal, Provincial and Territorial (FPT) Forum of Ministers Responsible for Seniors. The views expressed in this report may not reflect the official position of a particular jurisdiction.

In support of work on the topic of Aging in Community, the FPT Forum of Ministers Responsible for Seniors previously developed 3 documents:

- Report on Housing Needs of Seniors

- Core Community Supports to Age in Community

- Social Isolation among Older Adults during the Pandemic

These reports should be reviewed and considered together.

Executive summary

In this section

1. Introduction

This report identifies possible actions, strategies, approaches, policies and research to promote aging in community by addressing gaps or weaknesses in the existing system. It analyzes the roles of local, Indigenous, provincial or territorial, and federal government. The report examines the diversity of older adults, including in terms of gender, ethnicity, immigrant and refugee status, health and wellness, geographic location, income level, and access to housing. The multiple roles that older adults play in communities as caregivers, volunteers, employers and employees are also considered, as well as how the for-profit and not-for-profit sectors can support aging in community.

The current work builds on the reports of Puxty et al. (2019), Report on Housing Needs of Seniors, Carver et al. (2019), Core Community Supports to Age in Community and Wister and Kadowaki (2021), Social Isolation among Older Adults during the Pandemic. These 3 reports were approved by the FPT Forum of Ministers Responsible for Seniors and primarily addressed housing, community and social services, and social isolation. The 3 reports also discussed access to:

- health care services

- recreation services

- transportation services

- financial and retail services like banks and supermarkets

- volunteerism or employment

- technology

- communication

Following the Introduction, the report is divided into 4 substantive sections:

- Assessing the issues and gaps to aging in place

- Integrating housing and community supports

- Emerging trends

- Social Isolation and the COVID-19 Pandemic

These sections synthesize the key findings from the previous reports. The penultimate section of the report, Recommendations for actions, is organized by major themes, namely housing, core community supports, connection to community, and research, and by time frame, based on whether the results will be observable in the short, medium or long term. Running through all sections is the acknowledgement that there are variations by province or territory; and whether older adults live in Canada’s largest cities, medium size cities, small towns, or rural or remote communities.

2. A synthesis of the findings

In assessing the issues and gaps to aging in place, the main barrier to emerge is a lack of housing supply. This section focuses on improving access to housing along a continuum between remaining in one’s home and long-term care (LTC). A second group of gaps results from the demand for core community supports which outstrips the supply, the variations in core community supports, and the limitations of supplying core community supports through voluntary organizations and informal caregivers.

The section on integrating housing and community supports reviews various examples including supportive housing or assisted living, campus care models, naturally occurring retirement communities with integrated supportive services programs (NORCs), and co-housing models. The roles of open spaces, transportation, smart technologies, and communications are assessed for their impact on integrating housing and community supports. The final part of the section addresses enhancing social participation, respect and social inclusion, and civic participation and employment.

The theme of the emerging trends is how the older population is likely to change over time. Beyond the likelihood that a quarter of the population will be over 65 by 2041, the section highlights issues such as the future technological divide among the older population, breakdowns in family models that support older immigrants and refugees, the ongoing isolation of LGBTQ2 older adults, and the many unique challenges that Indigenous older adults face.

Many of the issues, gaps and solutions are re-evaluated in the section on social isolation in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Two broad themes are highlighted: first, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the social isolation of various populations of older adults, such as:

- in rural, remote, and northern communities

- LGBTQ2 older adults

- ethnic minority and immigrant older adults

- Indigenous older adults

- people living with dementia

- caregivers

- low-income older adults

Second, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the limitations of the current housing options available to older adults and the difficulties in providing core community services without in-person contact.

3. Recommendations for action

Recommendations for consideration by all levels of government are grouped by broad theme: housing, core community supports, connection to community, and research. Actions are also organized according to whether their impacts will be seen in the short, medium or long term (now, in the next 5 years and beyond 5 years, respectively).

To better meet the diverse housing needs of older adults, short-term actions include policy reviews to facilitate construction and incentivize universal design, and involving Indigenous groups to a greater degree in planning to meet their needs. Long-term actions include changes to the tax environment or the creation of partnerships in the for-profit and not-for-profit sectors to encourage construction.

To improve access to core community services, a short-term recommendation is to work with community and non-profit organizations to develop sustainable funding models. Partnerships with post-secondary institutions and community organizations to enable more and better care, improved visitation with families and caregivers, and programs to combat social isolation and loneliness would see results in the medium term. Actions to address the challenges that small towns, and rural, remote and Indigenous communities face to ensure that a similar range of services can be found regardless of where one lives would see results in the long term.

To better connect older adults to their communities, broad areas for action include transportation and technology. To reduce social isolation by increasing access to transportation, actions to consider include an examination of the arbitrary age criteria for mandatory driver’s tests, and incentivizing transportation providers to offer more age-friendly vehicles. To help older adults leverage technology, a review of policies and training programs to provide older adults with the skills and resources needed to take advantage of smart technologies that help monitor health or facilitate social interaction could be carried out immediately. Medium- and long-term actions target the complex issues of making high-speed internet services more widely available while protecting the privacy and security of the older population.

While many of the above actions work towards reducing social isolation and loneliness among older adults, some recommendations address these issues directly. In the short term, programs can be tailored to meet various linguistic and cultural needs and be delivered via a range of mechanisms to better serve diverse populations of older adults. In the medium term, legislation could be crafted to encourage the creation of new spaces and infrastructure to promote social activity among older adults and the rest of the population.

For all of the above themes, recommendations emerged for research in the medium and long term to better understand demographics and trends. One recommended area for research is what the future older population will look like with respect to its socio-economic and health status, diversity, and gender profile. Another research area for consideration involves large-scale studies of smart home technologies to assess their feasibility, validity, and reliability and to compare the effectiveness of various technologies. A further avenue of research is to find effective means to combat ageism, racism, and homophobia against older adults. Possible topics include how to broaden programs to break down prejudice towards racialized, Indigenous, and LGBTQ2 older adults and the intersectional identities of the aging population.

4. Conclusions

This report highlights the synergies from previous reports on the housing needs of older adults, core community supports to age in community and social isolation among older adults during the pandemic. What the pandemic clarified are the limitations and fragility of existing housing and core community support programs when older adults are isolated in their homes and service delivery is hampered by providers (formal and informal) being prohibited from in-person contact. While many creative alternative modes of delivery were found, many of them depending on the internet, these too had their limitations. Post pandemic, we will no doubt celebrate the resilience of older adults, formal and informal care providers, and service providers from the public, not-for-profit, and for-profit sectors, in their efforts to reduce the negative impacts on older adults. However, all levels of government will need to continue to promote successful aging in the community by addressing unmet housing and community support needs and reducing levels of social isolation and loneliness which continue as part of the lives of many older adults across Canada.

1. Introduction

In this section

1.1 Background

The overall goal in this report is to identify possible actions, strategies, approaches, policies and research that could be applied to address some of the gaps or weaknesses in the existing system to promote aging in community in the short, medium, and long terms. The analysis focuses on the roles of government (local, Indigenous, provincial, territorial and federal). As much as possible, the report takes into account the diversity of older adults (that is, gender, ethnicity, immigrants and refugees, health and wellness, low-income, homeless), the multiple roles that older adults play in their communities (for example, as caregivers, volunteers, employers and employees) and the for-profit and not-for-profit sectors. Where possible, distinctions are also drawn among older adults living in urban, rural and remote communities.

The starting point of this report is to consider and assess the issues and policies previously identified in the reports of Puxty et al. (2019), Housing Needs of Seniors, Carver et al. (2019), Core Community Supports to Age in Community and more recently, Wister and Kadowaki (2021), Social Isolation among Older Adults during the Pandemic. These 3 reports were approved by the Federal, Provincial and Territorial Forum of Ministers Responsible for Seniors. As the titles suggest, these reports primarily addressed housing, community and social services, and social isolation. To a much lesser extent, the 3 reports also discussed health care services (mainly home care and long-term care, not primary or secondary or tertiary acute care services); recreation services; transportation services; financial and retail services (for example, access to banks and supermarkets); voluntarism and employment; technology and communication. The key findings of the 3 reports are summarized in Appendices 1, 2 and 3.

For purposes of this report, the “short term” is defined in terms of acting now, the “medium term” is defined as starting now but recognizing that the impacts are more likely to be recognized over the next 5 years, and the “long term” is defined as starting now but that the impacts are more likely to be recognized beyond 5 years.

In the policy and research literature, “seniors”, “older population”, “elderly population” and “older adults” are terms used to refer to the population aged 65 and over. This report uses the term older adults for anyone aged 65 or over except where quoting or referencing work where other authors have used a different term.

1.2 Looking ahead

Several pre-existing or emerging trends across the country make it difficult for older adults to age well in their communities and need to be considered in developing future policies, practices, and research. While in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, we are also now recognizing unanticipated limitations of policies and practices. For example, public health measures implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic to minimize the spread of COVID-19, particularly to high-risk groups such as older adults aged 70 years and over, have led to experiences of social isolation and loneliness, which have had a serious impact on their mental well-being. During the first 3 waves of the pandemic, many older adults were unable to attend some social activities, be physically active outside their home, visit with friends and family or benefit from support systems such as funerals, religious rituals, and other face-to-face activities. In addition, older adults faced new challenges for such things as obtaining groceries and medical supplies and using transportation. Many of the practices that were used to slow the spread of COVID-19, and which made it more difficult to address core housing needs and access community supports and services to reduce social isolation and loneliness, have now been ended. As the pandemic lingers on, what practices might be reinstituted are difficult to predict.

What can be anticipated is that between 2036 and 2041, Canada’s older population will grow to 25% of the total population (Statistics Canada Seniors and Aging Statistics). Echoing the current geographic distribution of older people (see Atlas of the Aging Population of Canada), the vast majority of the older population will live in Canada’s largest urban centres. In rural and remote communities, and in many urban communities that do not benefit from large influxes of immigrants, older adults will make up well-above 25% of the population.

As the percentage of people who receive a post-secondary education continues to grow in Canada, (Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada, 2011; Statistics Canada, 2017) each new cohort of older adults will be better educated than the previous. A better educated older adult population is likely to manage their health and later years more effectively than a poorly educated older adult population. It is also likely that each successive cohort will be better positioned to take advantage of new “smart” technologies (Rosenberg and Waldbrook, 2017), such as those that support self-monitoring, analysis, and reporting.

What is less predictable than the size of future generations of older adults and their education trends is the cultural composition of those generations. It is more likely that the older adult population in the largest cities will be more diverse than in small town and rural communities. In small towns and rural communities, the challenge of serving small numbers of older adults with diverse backgrounds may lie in the higher cost per person of taking account of diversity issues in service delivery (Statistics Canada Seniors and Aging Statistics). What we already know from research about older immigrants is that they are mainly concentrated in the largest urban areas and many of the barriers that they face in aging in community relate to communication barriers, prejudice and changing familial models (for example, the breakdown in the tradition of children supporting their elderly parents, or “filial piety”) that make them vulnerable through isolation.

There is also a growing debate about whether each new cohort of older adults will have higher or lower incomes than previous ones given the changing nature of the Canadian labour market. Those who are optimistic focus on greater participation rates of women in the work force, growth in incomes, and declines in poverty of older adults over time (for example, MacDonald 2019). The more pessimistic focus on younger age cohorts having difficulty finding full-time employment, entering the labour market later in life and exiting earlier, the decline in long-term secure, unionized employment with substantial retirement benefits attached to those jobs, the growth in the nature of precarious work (that is, the “gig” economy) and the inability to purchase a home or entry into the housing market later in life (for example, Anani, 2018).

Population projections show that the total number of Indigenous people in Canada is expected to increase by 40% between 2006 and 2031, while the number of those aged 60 or over is expected to triple (Malenfant & Morency, 2011; Morency et al., 2015). Indigenous people have higher rates of many age-related chronic diseases with an earlier age of onset for conditions such as diabetes, renal disease, and dementia (Jacklin, 2012). A recent study of aging and frailty in First Nations communities noted much higher incidences of frailty at younger ages compared to other Canadian populations (First Nations Information Governance Centre and Jennifer D. Walker, 2017). Indigenous people are also more likely to have higher core housing need gaps than the rest of the population of Canada (Department of Indigenous Services, 2020; Statistics Canada, 2017; Wali, 2019).

Another emerging trend is the growing awareness of the needs of the older adult LGBTQ2 population. There is little Canadian or international literature on LGBTQ2 older adults or the expectations of the working age LGBTQ2 population for their later years. As a group they are particularly vulnerable in terms of financial insecurity, fragile social and family networks, isolation and risk of stigmatization and victimization. It is important to note that, like other older adults, LGBTQ2 older adults live in both urban and rural communities. This means they experience a great variability in local sensitivity to their past and present needs and circumstances, and availability of services specifically designed for them.

While the trends described above are still likely to continue beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, the COVID-19 pandemic highlights the vulnerability of all older adults living in the community. The COVID-19 pandemic amplifies social isolation and exposes the limitations of many of the systems that are in place to combat social isolation. The COVID-19 pandemic has also highlighted the limitations of the current housing stock (for example, skyrocketing rents and housing prices; lack of supply of housing specifically designed to meet the needs of older adults, housing in need of repair) to meet the needs of older adults aging in the community. Furthermore, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, additional barriers hindered access to important support programs and in-person services normally delivered to the home or at alternative sites to facilitate aging well in community. We return to these themes throughout the report.

To support older adults to age well in a community, communities across Canada may want to consider how they can align with international values, including the goals of the UN Decade of Healthy Aging and the principles of an age-friendly community as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2007). The Decade of Healthy Ageing is focused on combatting ageism, ensuring access to integrated care and long-term care, and creating age-friendly environments. The WHO summarizes its age-friendly principles across 8 dimensions: the built environment, transport, housing, social participation, respect and social inclusion, civic participation and employment, communication, and community support and health services. At a policy and practice level, it is important to consider how to enable older adults to age in community nested within the higher-level goal of living in an age-friendly community and for all governments to work to make communities as age-friendly as possible.

2. Assessing the issues and gaps to aging in place

In this section

Currently across Canada, numerous governments and communities are taking steps to become more age-friendly (see Plouffe et al., 2012 and 2013 for a more detailed discussion of age-friendly communities as a concept and its application in Canada). Many communities have taken part in age-friendly community development activities at various levels in support of active aging and promoting aging in place. Through these activities, participating communities have learned to assess their level of age-friendliness, how to link an aging perspective into planning, and developed plans for how to create age-friendly spaces and environments. Although progress is being made, gaps still exist. Unfortunately, there are older adults in every province and territory who live in core housing need (Puxty et al., 2019, pages 12 to 16), lack core community supports (Carver et al., 2019, pages 15 to 21) or who live in places lacking the characteristics that they would prefer and that might therefore be labelled as “age-unfriendly.”

2.1 Improving access to housing

To address the gaps identified in Puxty et al. (2019) and Carver et al. (2019), a critical starting point is addressing the overall supply of housing, the development of alternative types of housing (that is, housing with various forms of tenure and levels of medical and non-medical support services) and to encourage universal design either through retrofitting existing housing or in all new housing. It is not only older women living alone or older people on low incomes or in poor health who do not have the advantage of living in age-friendly housing. For example, housing for Indigenous older adults is a growing issue both on and off-reserves. Some of these issues may partly be addressed through actions, strategies and policies mentioned below in the short and medium term, but in the long term they also need to be addressed through policies targeted at people earlier in life (for example, improved income supports programs, improved benefits for people with disabilities) to ensure that older adults enter their later years with adequate incomes, housing and community supports.

How to integrate housing and community supports for older adults also must be tackled through long-term policy changes that break down silos among the various parts of the provincial and territorial governments (for example, provincial or territorial governments often divide policy making on housing and community supports in separate ministries or departments). In breaking down these silos, governments also need to remain responsive to a multiplicity of demands not only from older adults but other age groups as well if they are not to encounter gaps in housing and community supports throughout the life course. In this context, the main issues to aging in place can be clustered around the gaps related to individuals, gaps related to the types of housing available, and gaps related to core community supports as identified in Puxty et al. (2019) and Carver et al. (2019).

All levels of government may want to consider strategies that increase the supply of affordable housing for older adults overall, with options that consider the range of health needs and income status of older adults. As noted by Puxty et al. (2019, pages 23 to 31), the national and international evidence reviewed demonstrated that no single housing option is preferable to older adults, and all of the options reviewed had positive benefits in sustaining the well-being of older adults. All levels of government may also want to consider how to change the tax environment or create direct grants that encourage the residential construction industry either alone or in partnership with local governments, for-profit or not-for-profit organizations, to build various types of affordable housing for older adults which incorporate features supportive of their accessibility and adaptability needs.

In the short term, local governments (supported by provincial and territorial governments) may want to review their zoning policies and by-laws to facilitate residential construction of various housing options for older adults. For example, changing zoning by-laws to allow for the construction of housing for older adults as part of shopping or recreational centre developments may be options for improving access to needed services that reduce the need for private or public transit options. In addition, strategies that incentivize builders, planners and purchasers to incorporate features of universal design for future adaptability and accessibility into new builds and renovations are policies that all levels of government might consider in the short term. These strategies, if implemented, will ultimately address some of the needs of older adults who want to age in place or seek new forms of housing as they get older. Policies related to universal design would also have an added advantage in that universal design creates housing options that are attractive to all age groups and those with physical limitations. Encouraging universal design policies might also indirectly lead to a more flexible supply of housing that will address housing shortages for many groups in urban, rural and Indigenous communities across Canada.

2.2 Improving core community supports

Every provincial and territorial government provides core community supports (for example, medical, and non-medical home care services) to facilitate aging in place and, by extension, aging in community. Older adults who require home supports can access them through provincial or territorial home and community care programs, non-profit older adult groups and community organizations, or by for-profit providers. Researchers have identified that between 20 and 50% of individuals on long-term care waitlists could potentially be diverted safely and cost-effectively to independent living with community and housing services if these services were available and affordable (Williams et al., 2009).

There are, however, challenges in providing enough core community supports within jurisdictions (for example, limited budgets relative to the demand) and there are differences in what core community supports are offered depending on where one lives (for example, the lack of dementia care services in small town, rural, remote and Indigenous communities). In the short term, how to make core community supports more geographically equitable is an issue that provincial and territorial governments may want to consider. Closely related to these broader challenges, small towns, rural and remote communities, and Indigenous communities face the additional capacity challenges associated with small populations often dispersed over greater areas, longer distances to provide home care services and limited demand, all of which result in higher costs per service on average. All levels of government may also want to consider how to address the unique challenges that small towns, rural and remote communities, and Indigenous communities face in providing core community supports (for example, higher per capita grants for core community supports in small towns, rural and remote communities, and Indigenous communities).

Finding ways to deliver non-medical services, such as helping older adults with outdoor yard work, for example, is also challenging (see the explanation of home care services in the Glossary). The supply and delivery of non-medical services is highly variable and often done by volunteers and informal caregivers. In addition, coordinating the delivery of non-medical services with medical services to maximize their combined effectiveness also poses challenges. For example, some jurisdictions have instituted single-point access models (for example, Community Care Access Centres in Ontario), but there remains much to improve in terms of assessment for eligibility, the ability to provide all medical and non-medical services required, and the volume of services required to support individual older adults living in the community. Innovative ideas to address many of these issues have been proposed (for example, see AGE-WELL APPTA PROPAVIT: Exploring the Opportunities for Home Support).

In the short to medium term, some of the challenges identified above can be resolved or ameliorated through more effective use of voluntary organizations and informal networks of family members, friends, and neighbours. There is, however, overwhelming evidence that even the largest voluntary organizations face sustainability issues in providing medical and non-medical services as part of core community supports. For example, the Seniors Association (Kingston Region) used to provide some medical services in partnership with the Southeastern Ontario Local Health Integration Network (LHIN). Today, this is no longer the case mainly because of the high costs associated with providing medical care services for voluntary organizations (for example, salaries for licensed health care workers, liability insurance, modified space to ensure privacy). These issues are exacerbated in small town, rural, remote, and Indigenous communities where burn out and capacity issues among volunteers and volunteer organizations are even more likely to occur because of the smaller number of voluntary organizations, the smaller scale of the voluntary organizations that exist and the number of volunteers. To overcome the limitations that voluntary organizations and volunteers face, provincial and territorial governments should consider working more closely with voluntary organizations to develop new sustainable models. Some of the criteria for new sustainable models might be long-term agreements that cover part of the overall costs of operations, all of the costs for specific services and part of all of the costs associated with transporting clients to voluntary organization sites or the transportation costs of volunteer outreach, particularly for voluntary organizations operating in small town, rural, remote, and Indigenous communities.

Informal caregivers will always be part of core community supports, but all levels of government should recognize that an increasing number of older adults do not have children or immediate relatives on whom to depend. The very fact that informal caregivers are much more likely to be women than men also generates a unique set of challenges, including the withdrawal of working-age women from the labour force. This means that future cohorts of older women who become informal caregivers now are more likely to struggle with the same issues (for example, low retirement incomes) as today’s older women who need community supports and housing. Solutions both to the present situation and the future might be found if all levels of government were to examine new models of financial assistance (for example, direct grants to low-income older adults or tax breaks to higher income older adults) to pay for non-medical care community services. These types of policies would allow older adults to pay for non-medical community supports whether they are provided by the for-profit or not-for-profit sectors or informal caregivers.

3. Integrating housing and community supports

In this section

Housing and the provision of core community supports cannot be viewed in isolation from the community in which they are located. Older adults need not only age-friendly housing; they also need their communities to be environments and socio-economic structures that are supportive and responsive to their needs. Therefore, the over-arching question is how to create and integrate various housing options and community supports to meet the growing diversity of the older population and the differences among large urban centres, small towns, rural, remote, and Indigenous communities to create age-friendly communities?

As Bigonnesse et al. (2014) have pointed out, older adults want to live near services and amenities such as grocery stores and health clinics, with opportunities to socialize, and pride themselves in completing daily activities and taking care of their homes. In a 2017 study conducted in Edmonton, Alberta, research showed that low-income immigrants and refugees between the ages of 55 and 92 would prefer to live within walking distance to grocery stores, pharmacies, medical clinics, amenities, and social activities in their community (Keenan, 2017). Furthermore, they did not want to live near a commercial area, an industrial area, or bars, as they would not feel safe. Several also mentioned a willingness to live near a shopping mall to help them stay mobile (Keenan, 2017). Another study showed that it is important for low-income older adults to live within walking distance to a grocery store, their doctor, a pharmacy, and a bus stop (Barrett, 2013).

With these preferences as context, 1 set of possibilities is to focus on the potential to integrate housing and community supports in the same housing or the same immediate location. Across Canada, one can find examples of supportive housing or assisted living, campus concepts, naturally occurring retiring communities, and co-housing models that integrate housing and community supports. As a complement to any of these models, access to transportation, recreation and technology can be instrumental in facilitating age-friendliness. Ideally, any new model in the community would be established in alignment with the other key components of age-friendly communities (accessible open spaces, transportation, communications and technology, social participation and recreation, respect and social inclusion, civic participation and employment) as enablers.

3.1 Examples of integrating housing and community supports

3.1.1 Supportive housing and assisted living

Supportive housing and assisted living often include design features for safety and accessibility as well as providing support services such as counselling, personal support and assistance with medication, recreational activities, housekeeping, and meal preparation. Depending on the province or territory, age and need for supports may not be the only 2 criteria for eligibility. Adults below the age of 65 may be eligible for supportive housing based on income and functional need (mobility or frailty).

It is important to note that the terminology used to define supportive housing varies widely across Canada. In British Columbia, supportive housing is housing with support services (for example, housekeeping, meals, and social activities). It is for low-income older adults and people with disabilities who may need some support, while assisted living is another category where care services for those with health needs are provided. The Alberta equivalent would be a seniors lodge for functionally independent seniors and supportive living for those with health needs.

Increasingly, housing developers and sponsors are integrating support services with housing and are generically calling their developments supportive housing or assisted living. Whether the sponsor is a not-for-profit group or a for-profit developer, such projects generally involve collaboration between the sponsor and other entities such as service providers, community groups, and government agencies to ensure the effective delivery of services and their successful coordination with housing.

Data from Statistics Canada’s 2007 General Social Survey (GSS) showed that only about 7% of older adults live in supportive housing. A Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) commissioned study of Canadians aged 45 and older indicated a much higher potential demand with 62% saying they would consider moving into supportive housing later in life (Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, 2016). Respondents aged 75 years and older who lived alone were more likely to indicate a higher preference for moving into supportive housing in the future in the CMHC report. In a submission by the Alzheimer Society of Canada and other organizations (2017), they reported substantial lack of supportive housing for people with psychosocial disabilities, people with intellectual disabilities, people with dementia, and Indigenous persons. They wrote that for people with dementia, “Community-based assisted living options, with many at a cost of up to $5,000 per month are out of financial range for most people with dementia who need such supports. The only option is long-term care if they are unable to be supported by informal caregivers at home” (Alzheimer Society et al. 2017, page 8).

A study of supportive housing use in Winnipeg, Manitoba noted that 10% of new admissions to Personal Care Homes (nursing homes) were similar in terms of functional needs to new admissions into supportive housing (Doupe et al., 2016). The supportive housing tenants typically received help with meals, laundry, and light housekeeping. They also received 24-hour on-site access to assistance to complete personal tasks like bathing, dressing, and grooming, and some (but not 24-hour) professional home care services. The primary difference between the Personal Care Home residents and the supportive housing tenants was that the supportive housing tenants had lower incomes or their informal caregivers had health challenges. In terms of government or health region contributions, the median annual cost for a resident in a Personal Care Home was $45,348 in contrast to $14,400 for a resident in supportive housing, suggesting there were opportunities for significant cost efficiencies (Doupe et al., 2016). Studies have also shown that diversion rates from long-term care (LTC) facilities could be further increased by offering supportive housing, where needed services could be more easily added to those already received by older adults as they remain in the same building (Williams et al., 2009).

3.1.2 Campus care models

A second concept for integrating core community services and housing is the campus care model. A campus care model is a form of community hub with a range of housing options and services for older adults. In its ideal form, a campus care model involves the co-location of various types of housing, a range of home-based services, grocery stores, health care centers, and recreation programs. Within these community settings, the campus model can serve as an excellent template to establish central care coordinators available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and nurture the concept of self-directed funding within a bundled care model. The campus care model also addresses increased demand for housing and services and creates the opportunities for economic growth and operational sustainability. This approach eliminates the need for older adults to move to a different location if they require a greater level of services and improves their quality of life by increasing their access to daily services. Providing local governments with support and broader flexibility to provide and fund services in the manner appropriate to their community would allow for innovation such as the campus care model.

Georgian Village in Penetanguishene, Ontario is an example of a campus care model where a local government, Simcoe County, took the lead in its development. Another example is a re-developed shopping centre (Centennial Square Shopping Centre) in Kingston where the private sector took the lead. The role of the local government was to provide flexible zoning which resulted in the establishment of a large drug store outlet with physician and physiotherapy services, a well-known coffee franchise, an apartment with a variety of private services (for example, a small restaurant, a dry-cleaning service) on the ground floor and most recently a second apartment building with various levels of assistance for older adults. A third example is Trent University’s proposal to include an older adult village as part of the next phase of its property development, which will integrate a continuum of housing options and take advantage of the university’s nursing faculty and Centre on Aging and Society to provide services).

3.1.3 Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities with an integrated Supportive Services Program (NORC-SSP)

A third concept for the integration of housing and community supports service are Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities with an integrated Supportive Services Program (NORC-SSP). The term Naturally Occurring Retirement Community (NORC) was coined in the United States in the early 1980s to describe a geographic area that has naturally developed a high concentration of older residents. This phenomenon is due to older adults remaining in their own homes as they age, or because they have congregated to an area after retirement or downsizing. NORCs exist in 2 main configurations:

- “Vertical NORCs” that develop in high-rise apartment buildings or co-op buildings

- “Horizontal NORCs” or “Neighbourhood NORCS” that encompass several low-rise buildings or single-family homes

The NORC-Supportive Service Program (NORC-SSP) model was developed to wrap services around these naturally occurring groups of older adults, and to help them remain living independently for as long as possible. They offer supportive services in the home or immediate community, which address the social determinants that are not typically managed through government programs: social connections and supports; care navigation; and nutrition and exercise, among others. While the model provides some direct health care services, it is largely a preventative health model with the goal of increasing access to ancillary supports that slow down the need for more extensive home care, at the same time as providing opportunities for older adults to meaningfully participate in their communities.

A key aspect of NORC-SSP is the evolution of partnerships between older adults including building owners and managers, service providers such as health care providers, home repair and adaptation partners, and other partners within the community, which creates a network of services, as well as opportunities for volunteerism (Greenfield et al., 2013). The model is based on economies of scale, where the large concentrations of older adults and their need for accessing services increases purchasing power. It also serves to decrease the fragmentation that exists in health and social services for older adults and provides greater flexibility of delivery than exists with the usual publicly subsidized programs. This model is typically found where these partnerships grow to a sufficient size to make it worthwhile among service providers.

3.1.4 Co-housing models

A fourth concept is the co-housing model. Co-housing models come in various formats. The most common formats are:

- 1 house or building shared by the owners

- 1 shared building for group activities including cooking meals together and social events and separate units for sleeping and private social activities

- separate, fully contained units and shared costs for common property elements (that is, age-restricted condominium or strata developments)

Co-housing models are being developed across Canada (for example, Harbourside Cohousing in Sooke, B.C.). The level of community supports found within them is determined by the members. Experiments are also taking place in terms of intergenerational co-housing models and hybrid models that combine elements of co-housing with other older adults’ housing models.

3.2 Moving beyond housing and community supports

For older adults to age in place as their health status declines, they need to be connected to their communities. In this section, we focus on the role of accessible open spaces, transportation, technology, and communication.

3.2.1 Accessible open spaces

The physical environment, urban and rural landscapes, streets, sidewalks, parks and buildings, has a major role to play in the mobility, independence and quality of life of older adults. A clean city with well-maintained recreational areas, ample rest areas, well-developed and safe pedestrian and building infrastructure, and a secure environment provides an ideal living environment for older adults to age in place.

Universally designed environments, products, and services are safer, accessible, attractive, and desirable for everyone and easily repurposed for other uses. Walkable communities have been shown to reduce the risk of chronic disease and improve public health and quality of life. (Kerr, et al., 2012). Furthermore, positive environments go beyond physical activity benefits; they can also enhance social support and interpersonal connectivity (Kaiser, 2009). Older adults who remain active are likely to live longer, be healthier, and have lower health care utilization or costs. Neighbourhoods that are walkable are associated with higher physical activity across the age spectrum, (Renalds et al., 2010).

Older adults potentially spend more time in their immediate community, so it also is likely that their health is more sensitive to community characteristics. Examples of characteristics associated with older adults’ health include barriers to physical activity, social arrangements and relevant community-level policies, a sense of neighbourhood or feeling of belonging, and exposure to neighbourhood stressors (Fisher et al., 2004; Young et al., 2004).

Walking, possibly the easiest active transportation form for older adults, is a potential avenue for increasing physical activity rates. Features that enhance the walkability of a community help older adults maintain their walking habits (Kerr et al., 2012). These features include park benches (Cain et al 2014), lower traffic speeds (Lee et al., 2013), and features that address special safety needs such as marked crosswalks (Moudon et al., 2011).

Thus, a community can be made healthier for older adults by changing characteristics of the physical environment to increase activity, decrease stress, and provide a sense of community and well-being. In England and Sweden, positive health changes were reported after simple changes were made to the physical environment, such as closing alleyways, decreasing the speed and frequency of automobile traffic, and improving recreation facilities. (Curtis et al., 2002)

Local governments are well positioned to influence the health of older adults and thereby their capacity to age well because a positive community environment affects residents’ health. For example, local governments can develop policies that (1) promote physical activity by changing zoning laws to create accessible open spaces and (2) promote social activity by improving characteristics of parks or other public gathering places such as ensuring rest spaces (for example, benches), providing shade or shelter, and providing access to nutrition and hydration.

Provincial and territorial governments may want to consider whether existing legislation is already sufficient or whether new legislation might be developed to encourage local governments to do more to create accessible spaces and infrastructure to promote social activity among older adults and the rest of the population.

3.2.2 Transportation

Driving is the primary mode of transportation for a large majority of Canadian adults, including older adults. The contemporary reality is that older adults rely overwhelmingly on private vehicles, either as drivers or passengers. In 2009, 3.25 million people aged 65 and over had driver’s licenses, or three-quarters of all older adults. Of that number, about 200,000 were aged 85 and over (Turcotte, 2012). Among older adults aged 65 to 74, 68% reported driving their own vehicle as their main form of transportation. A shift from driver to passenger is associated with older age groups. For example, 25.9% of older adults aged 65 to 84 travel as passengers in Canada’s census metropolitan areas. At ages beyond 85, 53.8% of older adults travel as passengers (Turcotte, 2012). However, driving remains the dominant form of transportation across all census metropolitan areas among older adults (Turcotte, 2012).

The transportation challenge is more difficult for older adults, especially low-income, older adults living in smaller and more rural communities, where they must depend almost exclusively on private vehicles to get around. Two-thirds of older adults (65.5%) living outside of Canada’s census metropolitan areas use automobiles as their primary means of transportation, compared to 56.8% of older adults living in census metropolitan areas. The difference is even greater among older adults aged 85 and older (40.2% vs. 27.1%) (Turcotte, 2012).

For all older adults, reliance on public transit was highest in the metropolitan areas of Quebec (13.9% of all older adults) and British Columbia (12.1%). The reliance on public transit by older adults living in census metropolitan areas outside of these 2 provinces was far lower, reaching no higher than 8.9% (in Ontario). Overall, less than 8% of older adults relied on public transit as their main mode of transportation, while less than 5% walked or cycled. Use of taxis or accessible transit was a low 1.2% in the 65 to 74 age cohort, although it climbed to 2.6% among those aged 75 to 84 and 7.4% among those 85 and older (Turcotte, 2012).

Given the high dependence on private vehicles rather than cycling, walking, or public transportation, some older adults continue to drive even as their physical and mental capacities deteriorate. Among older adults with significant vision impairments, 9% reported driving in the previous month and 7% reported driving as their main form of transport (Turcotte, 2012). More than 1 in 5 older adults who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia drove in the previous month and 17% reported driving as their main form of transport (Turcotte, 2012).

Transportation is important to the health, social participation, and overall well-being of Canada’s older adults. When older adults are no longer able or allowed to drive, their health, social participation, and overall quality of life often deteriorates. Thus, ensuring that transportation systems can support the mobility needs of older adults is a growing imperative. Furthermore, the World Health Organization (2007, 2017) emphasizes the role that transportation plays in healthy aging and aging in community because of its role in breaking down social isolation and ensuring access to community and health care services.

Both pre-pandemic and ongoing during the COVID-19 pandemic, programs to support affordable and accessible transportation for older adults can be found across Canada (Carver et al., 2019; Wister and Kadowaki, 2021). The programs are motivated by concerns about older adults’ abilities to actively participate in their communities, access essential services, and connect to their loved ones, especially for those living in rural or remote regions. There are, however, many variations in these programs related to eligibility, whether transportation is delivered through public transit authorities or separate public or private accessible transit organizations, whether the transit services are for-profit or not-for-profit, and whether the jurisdiction provides tax subsidies or credits to individuals to use transit services, among other things (see Carver et al., 2019, Wister and Kadowaki, 2021).

As noted above, many older adults face transportation challenges. Supporting driver cessation requires that accessible, appropriate alternatives are available to meet the needs of older adults. If aging in place and other living arrangements are to remain viable alternatives to long-term care, greater attention must be paid to the transportation needs and issues of older adults because of the crucial role that transportation plays in connecting where they live to where they access community supports outside of their homes and overcoming social isolation.

To address these gaps and indeed many others, there are policy areas where all levels of government have roles to play beyond those detailed in the report of the Council of Canadian Academies (2017) Older Canadians on the Move. First and foremost is the issue of licensing of drivers, which is a provincial or territorial matter. Older adults are going to continue to rely on driving their own vehicles in linking where they live and where services are available. What the data noted above makes clear is that provincial and territorial governments may want to review their policies if older adults who are physically impaired or who have various forms of dementia are driving on a regular basis. Provincial and territorial governments may want to go beyond arbitrary age criteria for mandatory testing of driving skills and provide greater guidance and support for health care professionals to assess the competency of older adults to continue to drive.

Second, new public transportation infrastructure, including vehicles that are age-friendly, will be needed as the older adult population grows in the future. This is often achieved through partnership with local governments or public transit authorities. It might also be useful for all levels of government to consider how to incentivize the for-profit and not-for-profit sectors to provide transportation in the development of various forms of communal housing described in the previous section and in more detail in Puxty et al. (2019). Private providers of transportation services at the local level (for example, taxi services and Uber type services) might also be incentivized to provide more age-friendly vehicles in their fleets and have basic disability awareness (that is, how to safely assist passengers, communicate effectively and provide door-to-door service). Provincial and territorial governments may want to review their regulatory frameworks to ensure drivers with large public transit authorities are properly trained to drive older adults who are frail or disabled.

A third broad policy area where all levels of government have a role to play is in the development of the built environment that facilitates other forms of mobility (for example, walking, cycling and e-bikes). It is up to local governments to make decisions about where new and better signs, traffic signals, and lighting would make it easier to navigate roads and sidewalks; more seating and public washrooms on pedestrian routes making them more suitable for older adults; and changes to the design of intersections, as well as introducing traffic calming measures and cycling infrastructure. Local governments are, however, hampered in making these decisions because of the significant investment that is required. Again, this is a role where all levels of government might consider how to finance changes to the built environment that would make transportation more age-friendly.

3.2.3 Technology

Certain smart technologies (for example, smart phones and digital home security systems) can help older adults age in place by allowing them to remain in their homes for as long as possible. Smart technologies can support aging in place by assisting older adults with functional impairments, communication challenges, or the need for monitoring of chronic diseases (Peek et al., 2014). They have also been shown to help alleviate social isolation, depression, anxiety and loneliness (Czaja et al., 2018). Smart technologies can potentially promote independent living and safety through a variety of mechanisms.

As individuals strive to maintain their independence, there may be a need for monitoring health and mobility that can identify changes that may put them at risk. Such monitoring could include changes in broader health markers that might suggest the risk of adverse events. As examples, smart home technologies have been demonstrated that can identify abnormalities in gait (Lockhart et al., 2014), onset of infection (Rantz et al., 2015) and changes in cognitive functioning (Seelye et al., 2018). As older adults walk around their smart homes, floor tiles can collect vital signs such as heart rate and blood pressure. Motion sensors detect falls and connect the older adult to a caregiver or emergency services.

Smart communication technologies in the home have also been used to facilitate social connections (Gustafson et al., 2015), relationships with healthcare providers, and tele-rehabilitation (Khan et al., 2014).

Current technologies allow older adults to consolidate control of a broad range of systems, including lighting, temperature, security, and entertainment in easily accessible electronic formats that can be operated through interactive touch commands or by voice. Looking to the future, homes will likely be designed with smart technologies such as sensor networks, motion sensors, infrared cameras, and robots that provide interactive technologies and unobtrusive support systems to enable older adults to enjoy a higher level of independence, activity, participation, or well-being.

New technologies offer innovative new approaches to access health care. Virtual care platforms allow older adults in remote communities to access health professionals from their homes. Wearable health technologies will empower older adults to play an active role in their own health management. Technology-based solutions offer a way to track, monitor and improve health, while empowering older adults to take control of their own well-being (Hirani et al., 2014).

There is a need to strengthen the social networks of older adults and caregivers and enhance their capacity to be active members of social and family networks. Technology-based innovations in teleconferencing applications and digital storytelling tools offer new ways for older adults and caregivers to foster intergenerational dialogue and stay connected with friends and relatives who live far away.

Older adults are long-standing contributors to the Canadian economy and have an abundance of knowledge and expertise to share with younger generations. New technologies can support older adults to remain in the labour force longer and protect their financial well-being, thus positively impacting their autonomy and independence. Technology-based solutions can also support caregivers in the workforce who are striving to balance their care work and paid work roles.

Cognitive changes that may happen during aging increase in prevalence at older ages, varying in severity and impact. Technology holds the promise to help seniors monitor changes in their cognition, provide mental training to reduce the impact of these changes, and create systems that assist individuals and families to monitor safety, and maintain financial security (Chouvarda et al., 2015). Wander detection systems can provide caregivers with the peace of mind that comes from knowing that seniors are safe at home.

While some seniors remain completely independent and continue to drive without assistance, others may be able to drive but require vehicle modification or advanced technologies to assist them while operating a vehicle (Classen, 2018). New technologies could also help seniors more safely and easily use public transportation. Modernizing public transport to ensure accessibility and include user-friendly navigation technologies like talking maps, obstacle-detection systems for wheelchairs and autonomous vehicles, would result in a more inclusive transportation system and a better quality of life for older Canadians.

However, use and acceptance of technology by older adults to support aging in place varies. Overall, older adults express several concerns with using home technologies to help facilitate aging in place (Peek et al., 2014). For example, they report concerns about cost, difficulty in its use, false alarms and forgetting or losing portable technology (Peek et al., 2014). Furthermore, older adults might view use of technology as an indicator for decline in function (Reeder et al. 2013). In a study in 2017, the vast majority of older adults indicated that they would like to age in their homes and communities, but only 33% would consider installing smart home technologies (HomeStars, 2017). In a survey of municipal, community, and health organizations in Ontario, the most common barriers for technology use by older adults that organizations reported were limited access to the internet, lack of knowledge on the use of technology, and the need for assistance with setting up technology (Ontario Age-Friendly Communities Outreach Program (2021a, 2021b).

In the future as smart technologies continue to improve and become more affordable, there is the potential to optimize quality of life for older adults. For example, home robots have the potential to reduce the stress and burden on formal and informal caregivers. It is also no longer beyond the realm of possibility that some older adults will be able to delay or avoid the move to long-term care facilities with the use of smart technologies.

Current large-scale studies of smart homes and other new smart technologies are needed to assess the feasibility, validity, and reliability of functional monitoring and to compare the effectiveness of various technologies. In addition, research is needed to determine which parameters should be measured. Evaluation of optimal monitoring strategies and timing, usability issues, and cost should all be performed. Importantly, users’ preferences should be explored to determine what they would like to know and with whom they wish to share that information. Compatibility among different smart home platforms should be considered to avoid over reliance on a single vendor or solution. Future studies will be needed to assess issues like privacy, surveillance, and who should control the data generated by smart technologies.

All levels of government may want to consider ongoing consultation with industry, sector leaders, researchers, and older adults specifically with a focus on “age-tech” and the “silver economy” to better understand the perspectives of older adults, industry, and health care organizations on this massive and growing opportunity. All levels of government may want to consider the expansion of their investments and support of research opportunities that include more work on age-tech and how these technologies can support aging in community.

An example of the necessary investment is AGE-WELL, which was launched in 2015 through the federally funded Networks of Centres of Excellence (NCE) program. AGE-WELL is a pan-Canadian network that brings together researchers, older adults, caregivers, partner organizations and future leaders to accelerate the delivery of technology-based solutions that make a meaningful difference in the lives of Canadians.

These investments will produce the national data necessary for evidence-based decision-making, allowing Canada to be less reliant on international bodies for this information. This important research will be of use to stakeholders and industry across all sectors, private and public alike. Research is also needed to develop deployable smart home sensing packages that are tailored to meet the needs of individuals and are safe, reliable, effective and affordable. Best practice guidelines should be developed through public-private partnerships that are informed using smart technology in community testbeds across a diverse range of communities.

Ultimately, the greatest challenge for all levels of government will be to make high quality internet access available and affordable to all older adults wherever they live in Canada because internet access is at the heart of smart technology uptake.

3.2.4 Communications

As people age, communication skills may change subtly at least in part because of changes in physical health, depression, and cognitive decline. Aging may also impact physiologic changes in hearing, voice, and speech processes. Communication changes are commonly reported by older people. For those older adults whose culture or first-language is neither English nor French, the challenges of communication are even more complex in both making themselves understood and understanding everyday information.

People use communication to perform many functions in their day-to-day activities, including employment, social and leisure activities, community involvement, personal relationships, and meeting needs for daily living. Many of these functions may change with aging as people retire from their careers, their social circles and personal relationships change and their activity patterns change. They may require more services such as health care services or in-home help to meet their daily needs. With these changing roles, the effects of communication challenges also change. Limitations in communication also have an undesirable effect on ability to access and utilize health and community services through problems in communication via written information, telephone, and computer (for example, e-mail).

There is an increasing need for health care and other service providers to play a role in making their communities age friendly. Health care and other service providers need to be well versed in the appropriate strategies for communicating effectively with older adults because of the higher prevalence of communication disorders among older adults. Medical institutions and other public and private organizations will need to support health care and other service providers with the tools and training to serve older adults most effectively. Further research is needed to better understand the experiences and implications of aging with communication disorders, and to learn how to best minimize the disability associated with those disorders.

All levels of government, with their training partners (for example, universities and colleges), may want to review their policies on training in communications skills specifically to address the challenges that older adults have in understanding and communicating their needs and go beyond training in Canada’s 2 official languages. All levels of government may also want to investigate how communications technologies might be developed through private-public partnerships to meet the new communications challenges of older adults.

3.3 Participation and inclusion

Accessibility to open spaces, transportation, communications, and technology are ways of connecting older adults living in their own home with the community supports they need. There are, however, older adults who do not participate in their communities and feel excluded.

3.3.1 Social participation

Social participation is a form of social interaction that includes activities with friends, family, and other individuals. It can be 1-to-1 or in a group. Social participation has been shown to have health-protective effects in later life (Vogelsang, 2016; Douglas et al., 2017). Participation in activities at the community level and within family groups is linked to a sense of belonging, interpersonal social connections, and attachment to geographic location, and may be the key to achieving successful aging in this last stage of life (Douglas et al., 2017).

Older adults benefit from volunteering and participating in their communities due to a sense of satisfaction and efficacy, and communities benefit from the services and social capital older adults provide. Socially isolated older adults are less able to participate in and contribute to their communities. A decrease in contributions by older adults is a significant loss to organizations, communities, and society at large.

In one study, environmental variables associated with social participation differed according to location (Levasseur et al., 2017). Social participation of older adults living in metropolitan areas was associated with transit availability and quality of the social network, whereas social participation in rural areas was correlated with the presence of children living in the neighbourhood and more years lived in the dwelling. Having a driver’s license and greater proximity or accessibility to resources were associated with social participation in all areas.

The National Seniors Council Report on Social isolation of Seniors for 2013 to 2014 recommended 4 areas for federal action under 4 broad directions.

- Raise public awareness of the social isolation of older adults

- Promote improved access to information, services and programs for older adults

- Build the collective capacity of organizations and address the social isolation of older adults through social innovation

- Support research to better understand the issue of social isolation

The policy implications of reducing isolation, increasing participation in recreational activities and the community that can be drawn from above are both indirect and direct. Indirectly, breaking down social isolation of older adults results in improved physical and mental health, thus making communities more age-friendly may reduce costs to all levels of government in other sectors (for example, health care costs). The FPT Social Isolation Toolkits and Supplements linked to immigrant and Indigenous older adults are examples of valuable steps in helping break down social isolation. The FPT Social Isolation Toolkits and Supplements raise awareness about social isolation among seniors; introduce useful concepts related to social innovation; and show how social innovation can help to address social isolation in Canadian communities through successful examples. The Toolkits also offer insights into addressing the social isolation of older adults who may be more vulnerable, Indigenous, LGBTQ2 or new immigrants or refugees.

More directly, not-for profit organizations provide services for older adults and play a valuable role in communities across Canada. The vulnerability of these organizations especially in small town, rural and remote settings is well-documented (Skinner, 2014; Skinner et al., 2016). If these organizations are going to continue to deliver much needed programs and services, all levels of government may want to review their supports for these organizations including continuous funding which is essential to the sustainability of these organizations.

3.3.2 Respect and social inclusion

Persistent disrespectful attitudes and misconceptions about older adults and growing old are acknowledged as being a significant barrier to the development of good public health policies on aging (Officer, 2017). They lead to negative perceptions of aging (for example, by disregarding the contribution older people make to society) and can negatively impact health and wellbeing in later life (Nelson, 2005; Angus and Reeve, 2006).

While respect for older adults is mostly positive across Canada, negative preconceptions of aging still exist. All levels of government may want to consider ways to facilitate education about aging at an early age to raise awareness and dispel negative misconceptions. Intergenerational interactions have been shown to help dispel such notions and the social engagement can contribute to older adults’ self-esteem.

Age-friendly initiatives to involve older adults in activities where they have experience can keep them engaged with the community and help them feel valued in their community. An inclusive society encourages older adults to participate more in their community’s social, civic, and economic life. This, in turn, promotes active aging. A recent systematic review identified that music and singing, intergenerational interventions, art and culture and multi-activity interventions were associated with an overall positive impact on health outcomes in community residing older adults (Ronzi, 2018).

3.3.3 Civic participation and employment

Older adults are an enormous resource to their communities especially through voluntarism and increasingly in the labour force. Upwards of 50% of older workers indicate they plan to continue to work on a part-time basis when they retire (Pignall, 2010). Offering and promoting a wide range of volunteer and employment opportunities that cater to older adults’ diverse preferences, needs and skill sets helps to connect older adults to their communities. Age-friendly urban and transport infrastructure removes physical barriers older adults may face in accessing the volunteer or job opportunity. Continued training also helps older adults to improve their existing skills, learn new ones and strengthen their mental health. A job-related training study of older workers conducted by Statistics Canada shows that the participation rate in employer-supported training among workers aged 55 to 64 more than doubled between 1991 and 2008.

Entrepreneurial opportunities are another way to support older adults’ participation in the workforce and ensure their sustained self-sufficiency. Many older workers plan on remaining connected to the workforce in some way when they retire from their primary career (Thorpe, 2008). In a knowledge economy, the payback period on investment in training is becoming shorter for all workers, meaning that spending money on training older workers is likely to be recovered before those workers retire.

All levels of government may want to review their policies on older workers to ensure that they are encouraged to remain engaged within the work force. Older adults are a resource with valuable skills. The Government of Québec and the Government of Nova Scotia are both exploring policy initiatives to incentivize and support older adults to remain in the workforce longer. In fact, Québec has recently introduced 2 new tax credits to encourage experienced workers to remain in the workforce, which include an enhanced tax credit for experienced workers over the age of 60, and a reduction in payroll expenses for wages paid to workers aged 60 and over (Government of Québec 2019).

Some of the policy options that all levels of government might pursue are:

- strengthening financial incentives to carry on working with opportunities for phased retirement

- reducing potential barriers to employment of older workers through creation of age-friendly workplaces (for example, elimination of ageism among the workforce)

- improving the employability of seniors through provision of suitable training opportunities at all ages

4. Emerging trends

As alluded to in several places in the previous sections of this report, the only certainties are that the older population (aged 65 and over) will grow to about 25% of the total population of Canada sometime between 2036 and 2041 and that the majority of older adults will live in urban centres. In small towns, rural and remote communities, the percentage of the population that is over 65 and indeed, the percentage of the population aged 80 and over will, however, likely be much higher than the respective national averages and much higher than what is found in many larger urban communities in Canada. What is also likely is that the older adult population will continue to become more diverse.