Chapter 3: Impact and effectiveness of Employment Insurance benefits (EBSMs–Part II of the Employment Insurance Act)

From: Employment and Social Development Canada

Official title: Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2018 and ending March 31, 2019: Chapter 3: Impact and effectiveness of Employment Benefits and Support Measures (EBSMs–Part II of the Employment Insurance Act)

In chapter 3

List of abbreviations

This is the complete list of abbreviations for the Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2018 and ending March 31, 2019.

Abbreviations

- ASETS

- Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy

- ATSSC

- Administrative Tribunals Support Service of Canada

- B/C Ratio

- Benefits-to-Contributions ratio

- B/U Ratio

- Benefits-to-Unemployed ratio

- B/UC Ratio

- Benefits-to-Unemployed Contributor ratio

- BDM

- Benefit Delivery Modernization

- CANSIM

- Canadian Socio-Economic Information Management System

- CAWS

- Citizen Access Workstation Services

- CCAJ

- Connecting Canadians with Available Jobs

- CCB

- Canada Child Benefit

- CCDA

- Canadian Council of Directors of Apprenticeship

- CEIC

- Canada Employment Insurance Commission

- COLS

- Community Outreach and Liaison Service

- CSO

- Citizen Service Officer

- CPI

- Consumer Price Index

- CPP

- Canada Pension Plan

- CRA

- Canada Revenue Agency

- CRF

- Consolidated Revenue Fund

- CUSMA

- Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement

- CX

- Client Experience

- EBSMs

- Employment Benefits and Support Measures

- ECC

- Employment Contact Centre

- EF

- Enabling Fund

- EI

- Employment Insurance

- EI PAAR

- Employment Insurance Payment Accuracy Review

- EI PRAR

- Employment Insurance Processing Accuracy Review

- EICS

- Employment Insurance Coverage Survey

- eROE

- Electronic Record of Employment

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- FLMM

- Forum of Labour Market Ministers

- FY

- Fiscal Year

- G7

- Group of Seven

- GDP

- Gross Domestic Product

- HCCS

- Hosted Contact Centre Solution

- HRSDC

- Human Resources and Social Development Canada

- IQF

- Individual Quality Feedback

- IVR

- Interactive Voice Response

- LFS

- Labour Force Survey

- LMDA

- Labour Market Development Agreements

- LMI

- Labour Market Information

- LMP

- Labour Market Partnerships

- MIE

- Maximum Insurable Earnings

- MSCA

- My Service Canada Account

- NAICS

- North American Industry Classification System

- NAFTA

- North American Free Trade Agreement

- NAS

- National Apprenticeship Survey

- NERE

- New-Entrant/Re-Entrant

- NESI

- National Essential Skills Initiative

- NIS

- National Investigative Services

- NOS

- National Occupational Standards

- NQCP

- National Quality and Coaching Program for Call Centres

- OAS

- Old Age Security

- OECD

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

- PPEs

- Clients who are Premiums Paid Eligible

- P/Ts

- Provinces and Territories

- PPTS

- Percentage points

- PRP

- Premium Reduction Program

- QPIP

- Quebec Parental Insurance Plan

- RAIS

- Registered Apprenticeship Information System

- ROE

- Record of Employment

- RSOS

- Red Seal Occupational Standards

- SA

- Social Assistance

- SCC

- Service Canada Centres

- SDP

- Service Delivery Partner

- SEPH

- Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours

- SIN

- Social Insurance Number

- SIR

- Social Insurance Registry

- SME

- Small and medium sized enterprises

- SO

- Scheduled Outreach

- SST

- Social Security Tribunal

- STDP

- Short-term disability plan

- SUB

- Supplemental Unemployment Benefit

- UV

- Unemployed-to-job-vacancy ratio

- VBW

- Variable Best Weeks

- VER

- Variable Entrance Requirement

- WWC

- Working While on Claim

Introduction - Chapter 3

Activities conducted under Part II of the Employment Insurance (EI) Act help individuals in Canada prepare for, find and maintain suitable employment. Under the umbrella of Employment Benefits and Support Measures (EBSMs), these activities include programs delivered by provinces and territories under Labour Market Development Agreements (LMDAs), as well as the Government of Canada's pan-Canadian programming and functions of the National Employment Service (NES).

This chapter presents program results for EBSMs achieved under Part II of the EI Act during the fiscal year beginning on April 1, 2018 and ending on March 31, 2019 (FY1819). Section 1 provides a national overview of EBSM-similar programming delivered under the LMDAs and by agreement holders under the Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy (ASETS), which transitioned to the Indigenous Skills and Employment Training (ISET) program as of April 1, 2019. Provincial and territorial employment programming activities are presented in Section 2, with a description of each jurisdiction's labour market and employment priorities. Section 3 presents an overview of Employment and Social Development Canada's (ESDC's) study of the Job Creation Partnerships program. The section also builds on the well-being analysis presented in the FY1617 MAR with new poverty analysis based on the Market Basket Measure, Canada's new official poverty line. Section 4 discusses the results of ESDC's delivery of pan-Canadian activities, and the administration of NES functions.

Notes to readers

- The data used to analyze EBSM activities were collected from provinces, territories, and ASETS agreement holders. Governments continue to improve data quality and collection to ensure accurate, reliable, and consistent information. While all data sets are verified before publication, systems and operational changes may affect the comparability of data from year to year. In this context, the number of interventions for FY1819 may be over-represented nationally. More accurate intervention counts will be provided in future years of this report.

- References to average levels of activity and to highs and lows generally use the 10-year period from FY0809 to FY1819 as a frame of reference.

- Statistics Canada's Labour Force Survey (LFS) is the source of labour market data reported. Data for Canada and the provinces are fiscal-year averages, calculated using seasonally unadjusted monthly data, while monthly references are seasonally adjusted. Data for the Northwest Territories, Yukon and Nunavut are calculated using unadjusted three-month moving averages of monthly data. In discussions of employment trends by industry, standard industry titles are taken from the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS).

- Real GDP data and other non-LFS macroeconomic indicators are from Statistics Canada's Economic accounts. Forecasts rely on published analyses from the Bank of Canada, the Conference Board of Canada, Canadian banks, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and Statistics Canada, as well as on internal analysis, using information available as of January 2020.

3.1 National overview

In this section

3.1.1 Economic and labour market context

According to key indicators, Canada's labour market performed well in FY1819. Overall, the labour force grew by 1.1% to a total of 19.9 million workers, while employment expanded at a faster pace, +1.4%, to a total of 18.7 million. Employment among women grew by 1.5%, while men's level increased by 1.3%. For both women and men, the employment growth was concentrated in full-time work. In sum, Canada's employment rate edged up to 61.9% in FY1819, compared to 61.6% in the previous fiscal year.

Canada's unemployment rate edged down to 5.8% in FY1819, compared to 6.1% in FY1718. The unemployment rate of both women and men declined, with women's unemployment rate registering at 5.5% (compared to 5.7% in the previous year) and men's at 6.1% (compared to 6.5% in the previous year).

Despite this, ongoing challenges in the energy sector had an impact on labour markets in the Prairie provinces. Unemployment rates in Saskatchewan and Alberta remain above the national rate. As well, employment growth in both jurisdictions has been weaker than the national growth. Between FY1617 and FY1819, Canada's employment expanded by 3.3%, while in Saskatchewan and Alberta employment grew by 0.6% and 3.1%, respectively.

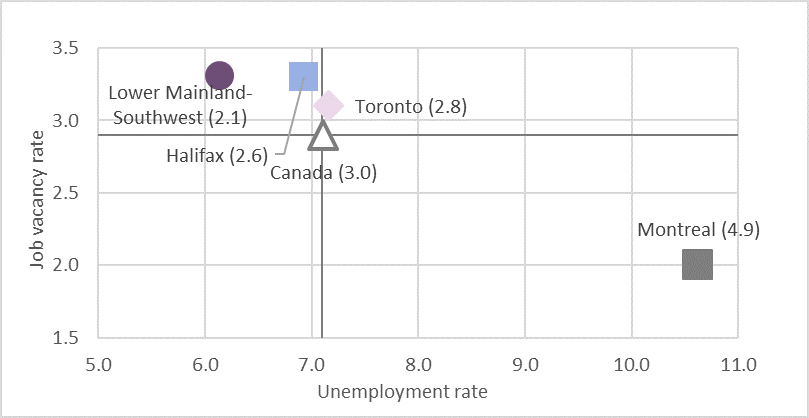

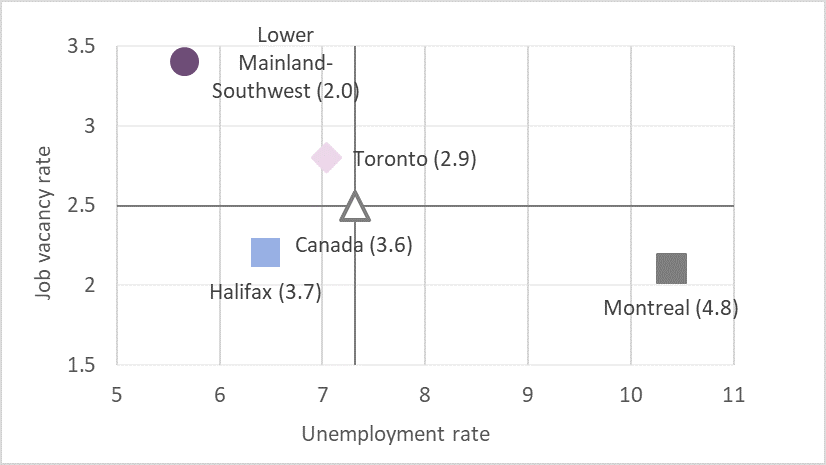

Statistics CanadaFootnote 1 reported 340,000 job vacancies across Canada in FY1819, compared to 287,900 in FY1718 (+18.1% increase year over year). The survey also reported 1.16 million unemployed workers in FY1819, declining by roughly 6% compared to the previous year. Taken together—expressed as the unemployment-to-job vacancies ratio (U/V ratio) —for every job vacancy in FY1819, 3.4 individuals were unemployed. In comparison, Canada's U/V ratio stood at 4.1 in the previous year.

In 2018, Canada's real gross domestic product (GDP) rose by 2.0%, following a 3.0% increase in 2017. Growth varied from 0.8% in New Brunswick to 7.6% in Nunavut. Real GDP increased in every province and territory, with the exception of Newfoundland and Labrador, where real GDP fell by 3.5%. For 2019, Canada's real GDP was forecast to grow by approximately 1.5%, with economic expansion projected in most parts of the country.

3.1.2 Main resultsFootnote 2

Decline in the number of EBSM clients and interventionsFootnote 3

In FY1819, provinces and territories served 670,431 clients under the Labour Market Development Agreements (LMDAs), a decline of 3.7% compared to the previous year. The number of LMDA interventions delivered to clients decreased by 4.5% year over year, to a total of 1,023,493 interventions.

Terminology guide

A client is a person who has participated in programs or services funded by the LMDAs or by Indigenous organizations. See section 1.3 for details for client types.

An intervention is a discrete program or service in which a client participates. See Section 1.4 and 1.5 for the type of interventions available to clients.

Any reference to participants is the number of interventions, where information on designated groups is collected at the intervention level, rather than individual client.

Combined with programs and services delivered by Indigenous organizations through the Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy (ASETS), a grand total of 695,610 EBSM clients were served (-2.8%), and 1,067,991 EBSM interventions (-3.6%) were delivered in FY1819.

The overall intervention-to-client ratio edged down to 1.54, compared to 1.55 in the previous year, as the number of interventions declined at a higher rate than the client totals.

Overall expenditures increased significantly by 18.4% to a total of $2.6 billion.

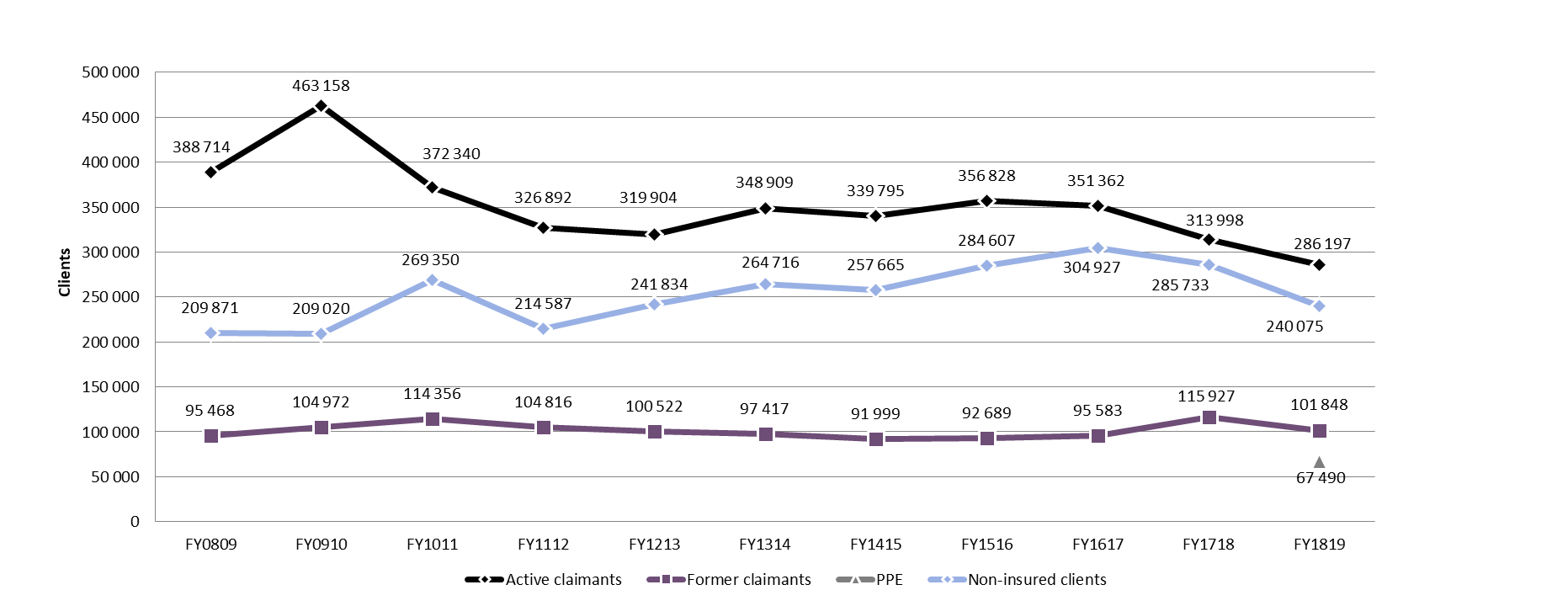

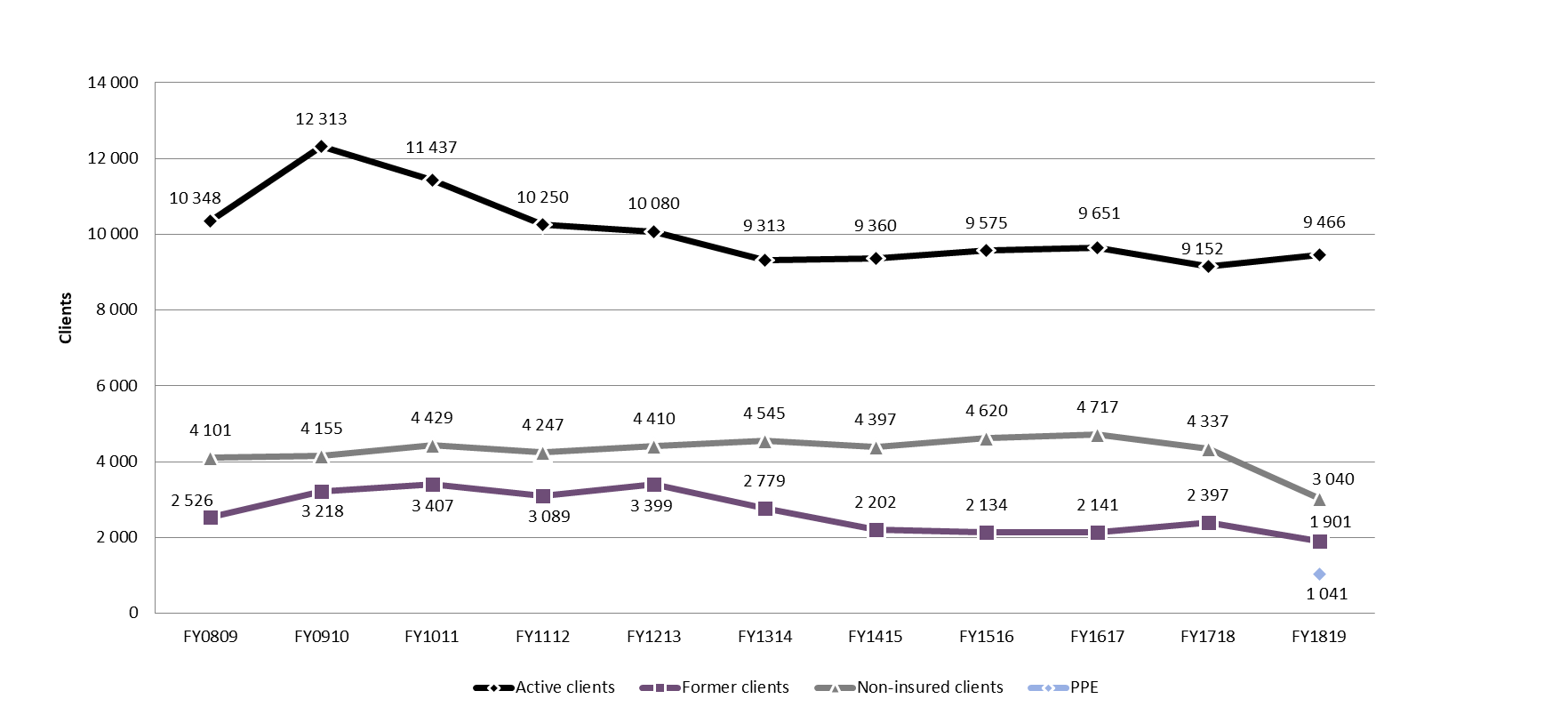

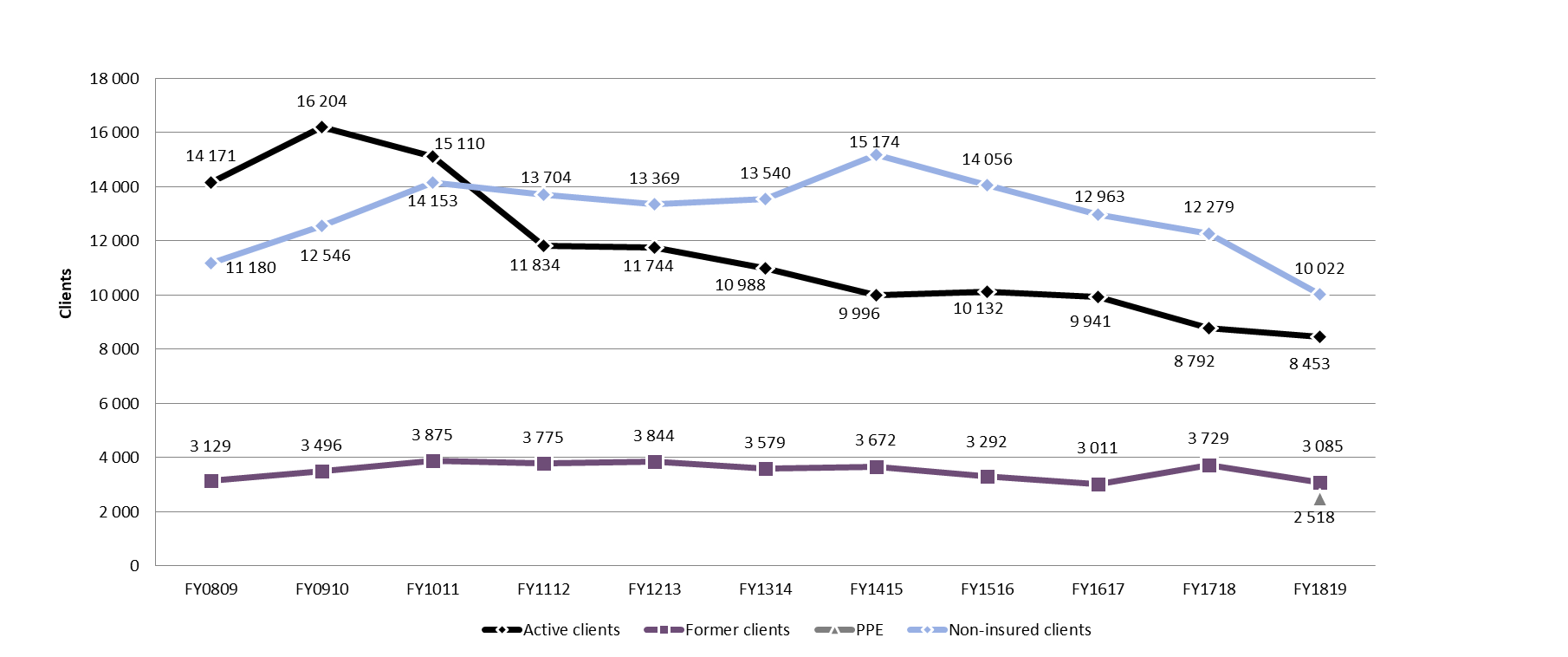

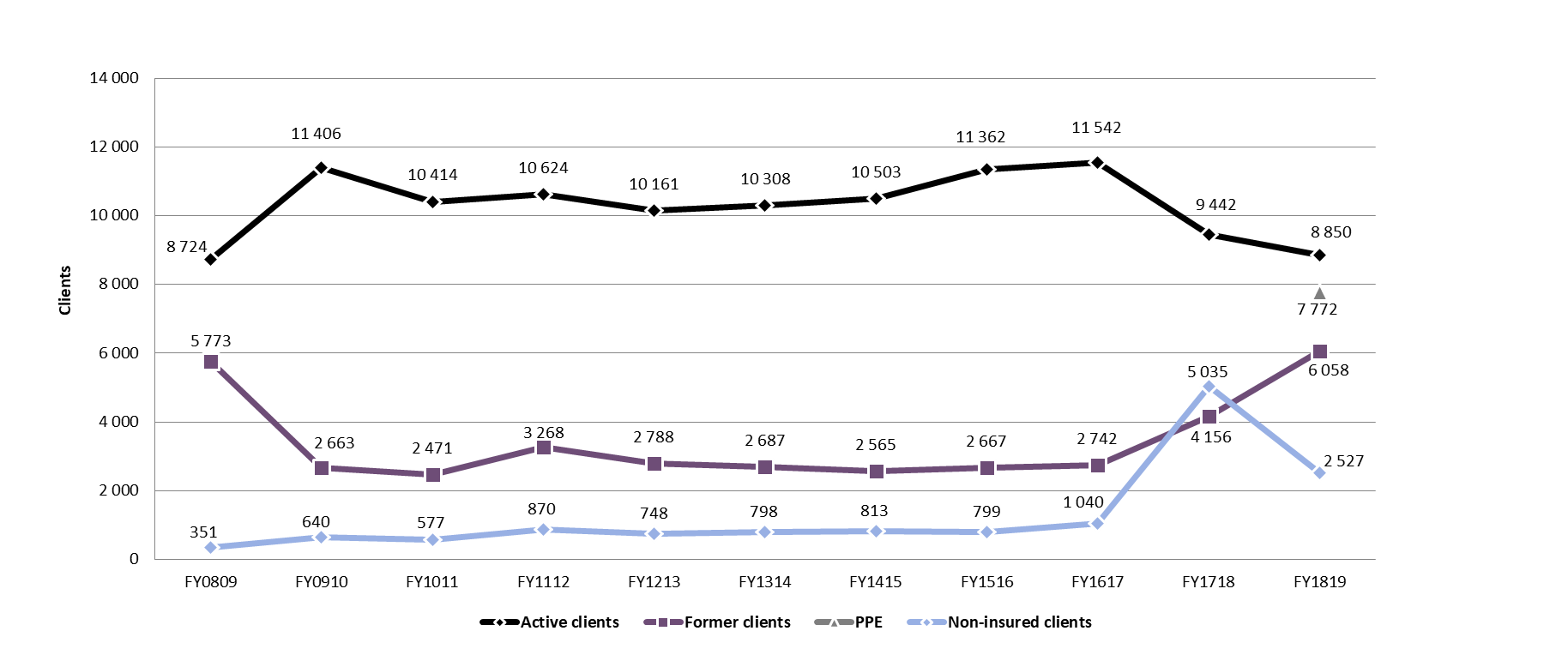

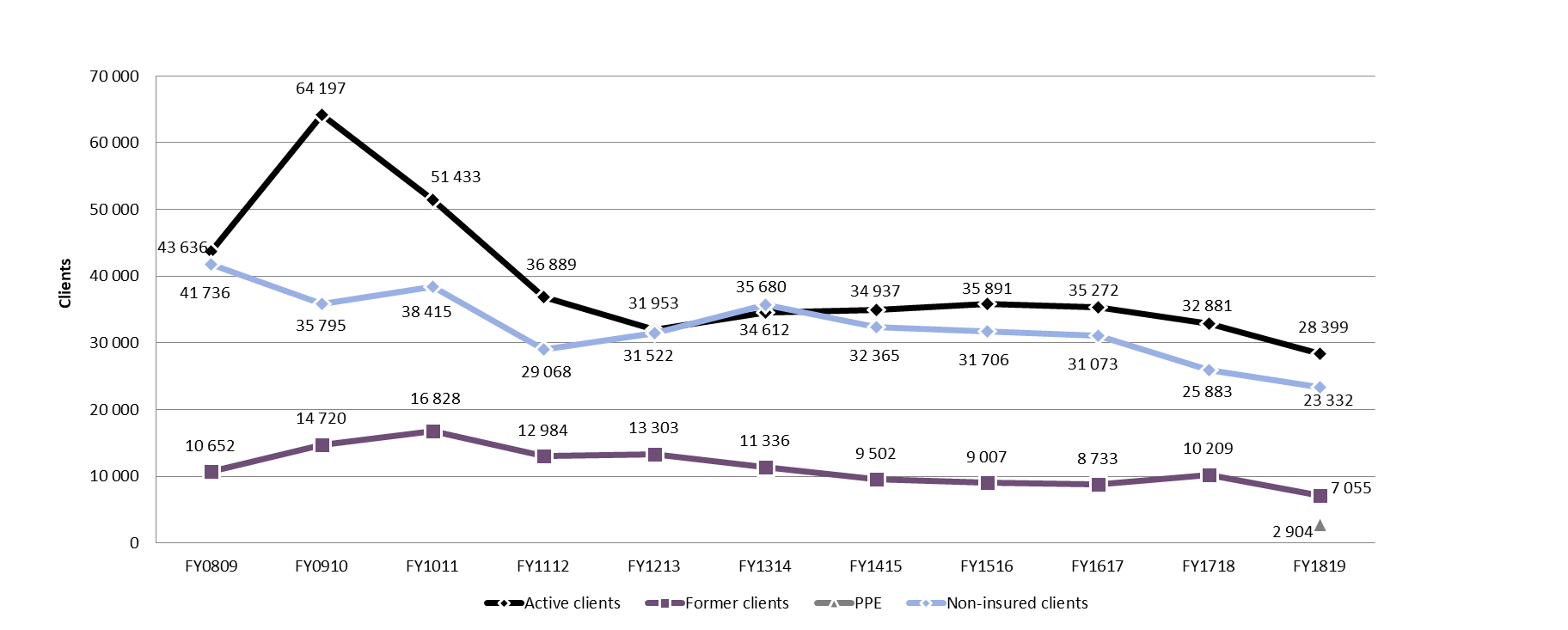

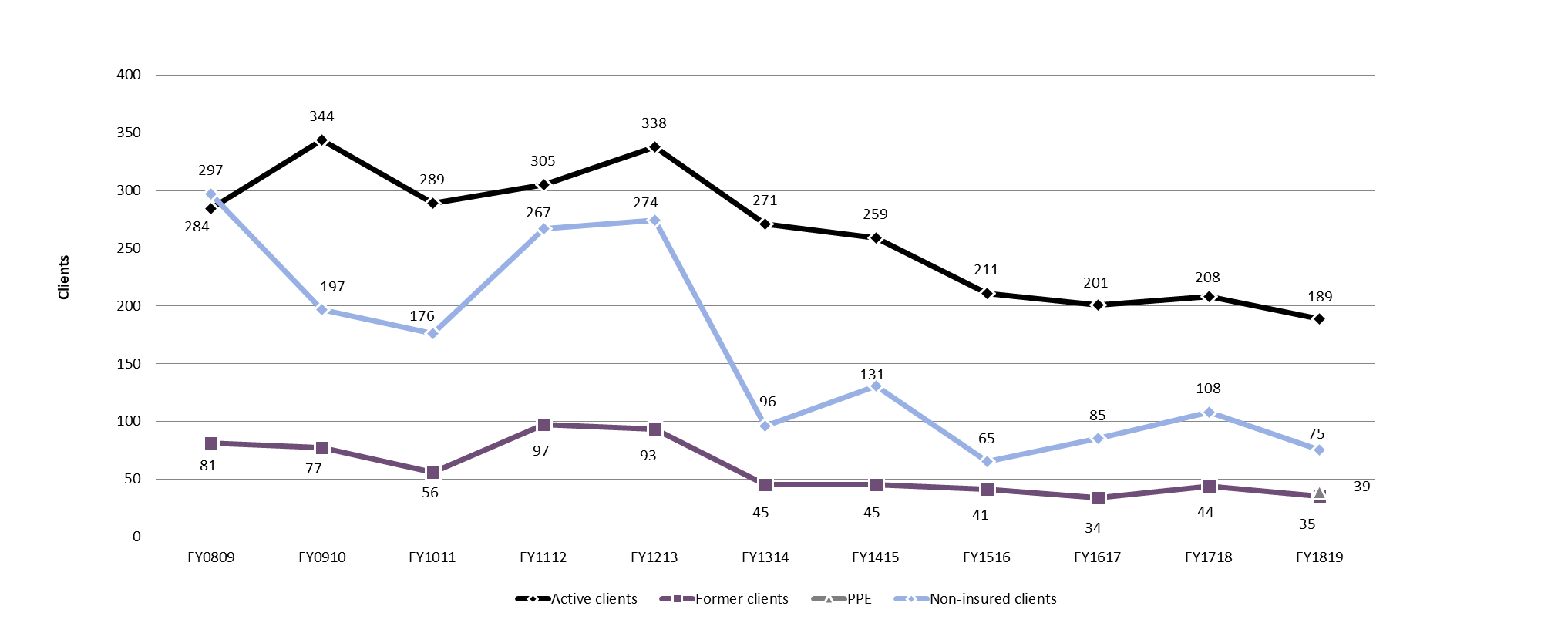

3.1.3 Client profile and participation

In FY1819, the total number of EBSM clients served declined by 2.8% year over year, with varying declines among the three traditional client groups. The number of active EI claimants declined by 8.9% year over year, to a total of 286,197, while former EI claimants dropped by 12.1%, to a total 101,848, and non-insured clients also declined by 16.0%, to a total of 240,075. The drop in non-insured clients is largely attribute to the creation of a new category for clients. As of April 2018, a new client group—Premiums Paid Eligible (PPE)—represented 9.7% of all clients, or a total of 67,490 in FY1819. See Table 1 for descriptions of the different client types and the box below for details on PPE.

Expanded eligibility under the LMDAs

Effective April 1, 2018, eligibility for Employment Benefits (for example, training, wage subsidies) was expanded to include all unemployed individuals who have made minimum EI premium contributions. With the expanded eligibility, a new client group—known as Premiums Paid Eligible (PPE)—was created to report on the unique characteristics of this clientele. In addition, eligibility for Employment Assistance Services was expanded to include all Canadians, whereas previous access was limited to unemployed Canadians.

PPE represented 9.7% of total clients; with those who were previously non-insured clients largely falling into the new group. Proportionally, Saskatchewan (27.1%), Nunavut (15.9%), Northwest Territories (15.0%) and Ontario (12.1%) had the highest percentage of PPE among their clients. The lowest proportion of PPE were in Newfoundland and Labrador (1.2% of all clients).

At the national level, roughly 54% of PPE clients were women and 46% were men. By comparison, across all client groups, fewer than 43% were women and more than 57% were men. This suggests the expanded eligibility under PPE has enabled more women to access training supports.

By age, most PPE were core-aged (69.4%) clients, followed by youth (16.6%) and workers aged 55 or older (13.8%). The largest cohorts of youth PPE were in New Brunswick (37%), Prince Edward Island (36%) and Saskatchewan (37%). PPE clients aged 55 or older were more prevalent in Nova Scotia and British Columbia, where they represented approximately 19% of all clients in both provinces.

Across Canada, PPE accessed a total of 104,537 interventions, most (82.6%) of which were Employment Assistance Services. With the broadened eligibility, PPE accessed 18,187 Employment Benefit interventions, previously accessible only by active and former EI claimants prior to the current fiscal year. ESDC will continue to monitor and assess PPE trends as data become available.

As a share of all clients, active EI claimants represented 41.4% of total clients, followed by non-insured (34.5%), and former EI claimants (14.6%) in FY1819. Active and former EI claimant client shares among all clients declined by 2.7 and 1.6 percentage points respectively, compared to the previous fiscal year.

Table 1 - Client descriptions

For accessibility reasons, the information is presented in text format. Consult the PDF version for the table.

Active claimants are those who had an active EI Part I regular claim when they requested assistance under Part II of the Employment Insurance Act. Typically, they have stronger and more recent job attachment. They tend to be able to return to work more quickly than those with weaker ties to employment. Active claimants who are considered job-ready from an analytical point of view often seek out short-term interventions under EI Part II to find their next employment opportunity. Others require longer-term Employment Benefits to upgrade their skills, establish certification or refine their job search strategies.

Former claimants are those who completed an EI claim in the previous 5 years, or who began a parental or maternity claim in the last 5 years when they requested assistance under Part II. They are no longer eligible for EI Part I; however, they remain eligible for EI Part II under certain criteria.Footnote 4Former claimants do not receive income support under Part I of the Employment Insurance Act while they complete an Employment Benefit intervention under EI Part II; however, they may receive Part II income support while completing their return-to-work action plan.

Premiums Paid Eligible are those who have made minimum Employment Insurance premium contributions above the premium refund threshold (that is $2,000 in earnings) in at least 5 of the last 10 years.

Non-insured clients are unemployed individuals who are neither active nor former EI clients. Non-insured clients usually have little substantive or recent job attachment. They include new labour force participants and individuals who were formerly self-employed without paid employment earnings. While these clients are not eligible for Employment Benefits under EI Part II, they may access Employment Assistance Services.

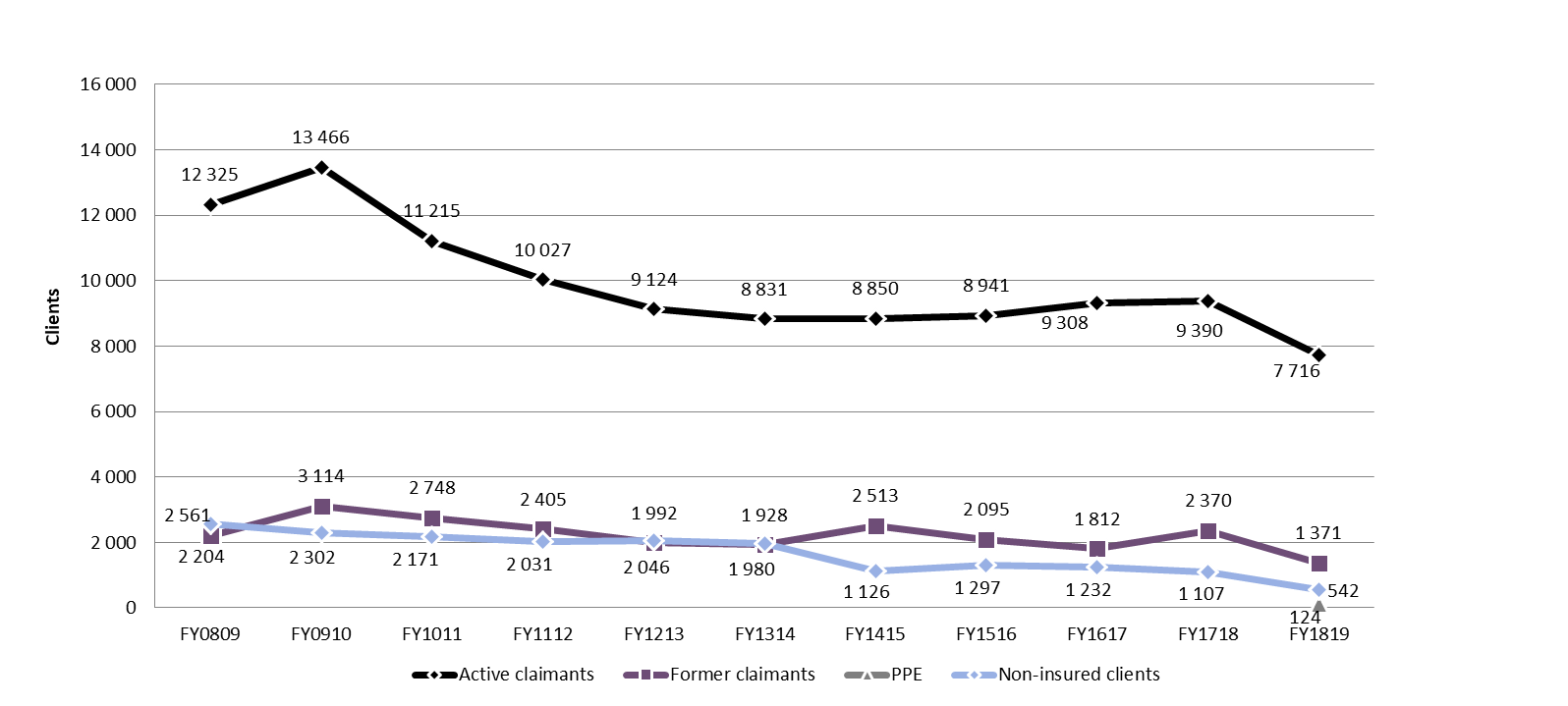

Chart 1 – Text version

| Client type | FY0809 | FY0910 | FY1011 | FY1112 | FY1213 | FY1314 | FY1415 | FY1516 | FY1617 | FY1718 | FY1819 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active claimants | 388 714 | 463 158 | 372 340 | 326 892 | 319 904 | 348 909 | 339 795 | 356 828 | 351 362 | 313 998 | 286 197 |

| Former claimants | 95 468 | 104 972 | 114 356 | 104 816 | 100 522 | 97 417 | 91 999 | 92 689 | 95 583 | 115 927 | 101 848 |

| PPE | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 67 490 |

| Non-insured clients | 209 871 | 209 020 | 269 350 | 214 587 | 241 834 | 264 716 | 257 665 | 284 607 | 304 927 | 285 733 | 240 075 |

Since FY0809, the number of EI active claimants has declined by 26.4%, while former EI claimants and non-insured clients increased by 6.7% and 14.4%, respectively. The drop in active EI claimants is largely attributable to the strong performance of Canada's labour market, resulting in an overall decline in EI program use among Canadians. In turn, provinces and territories focused on serving clients more removed from the labour market.

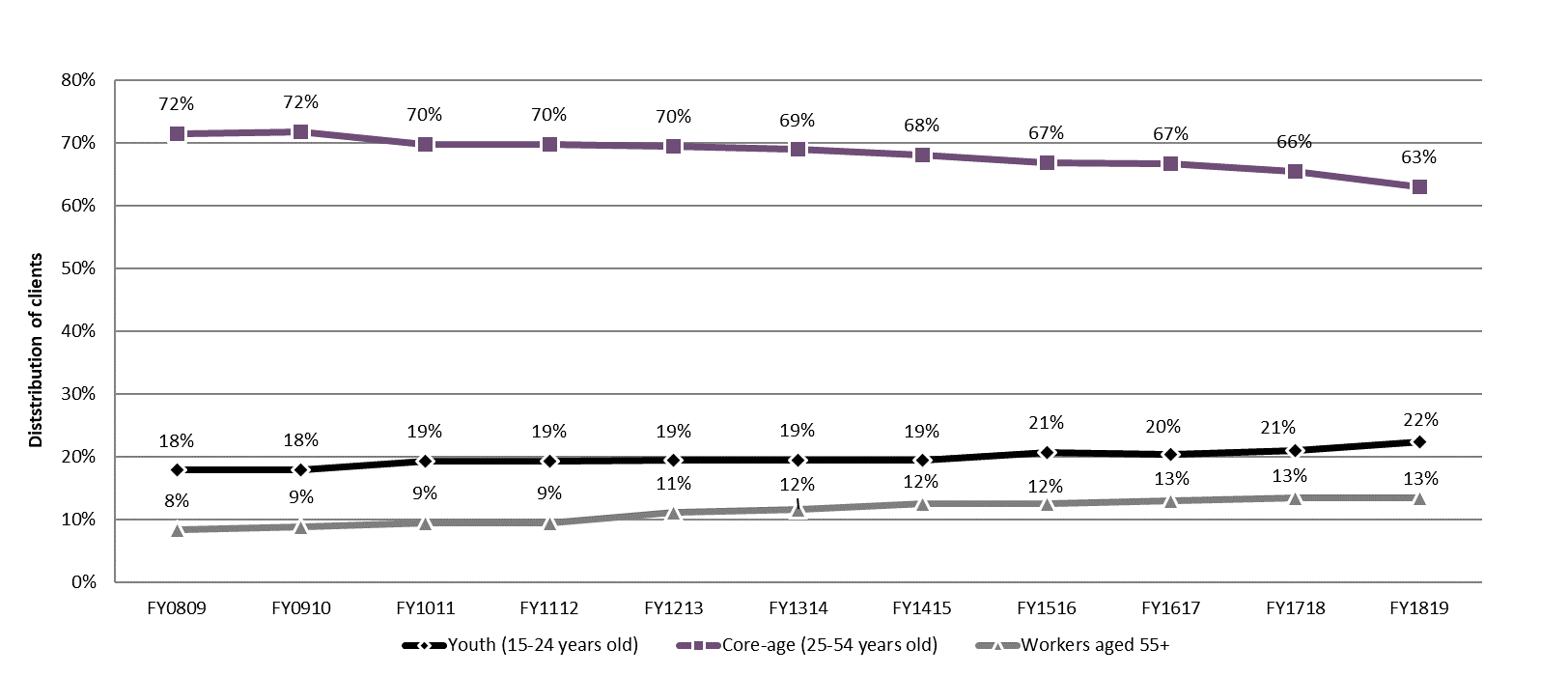

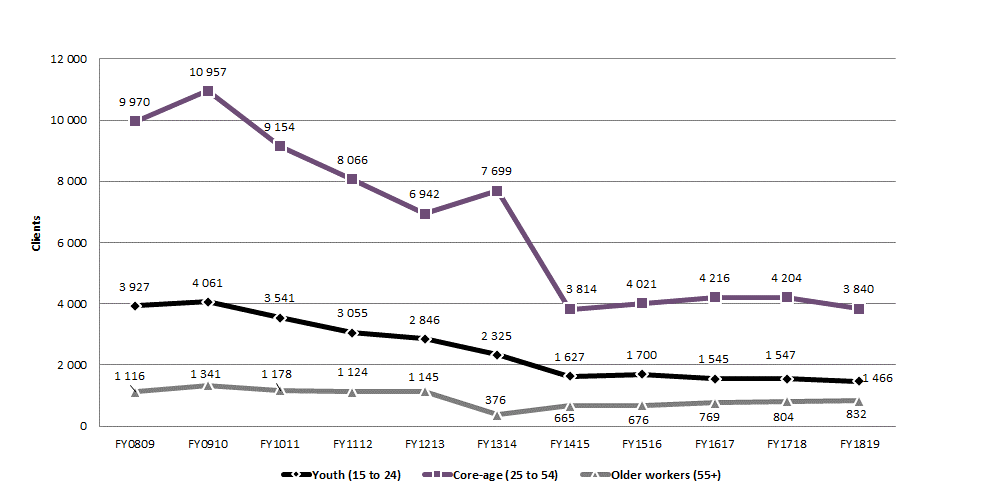

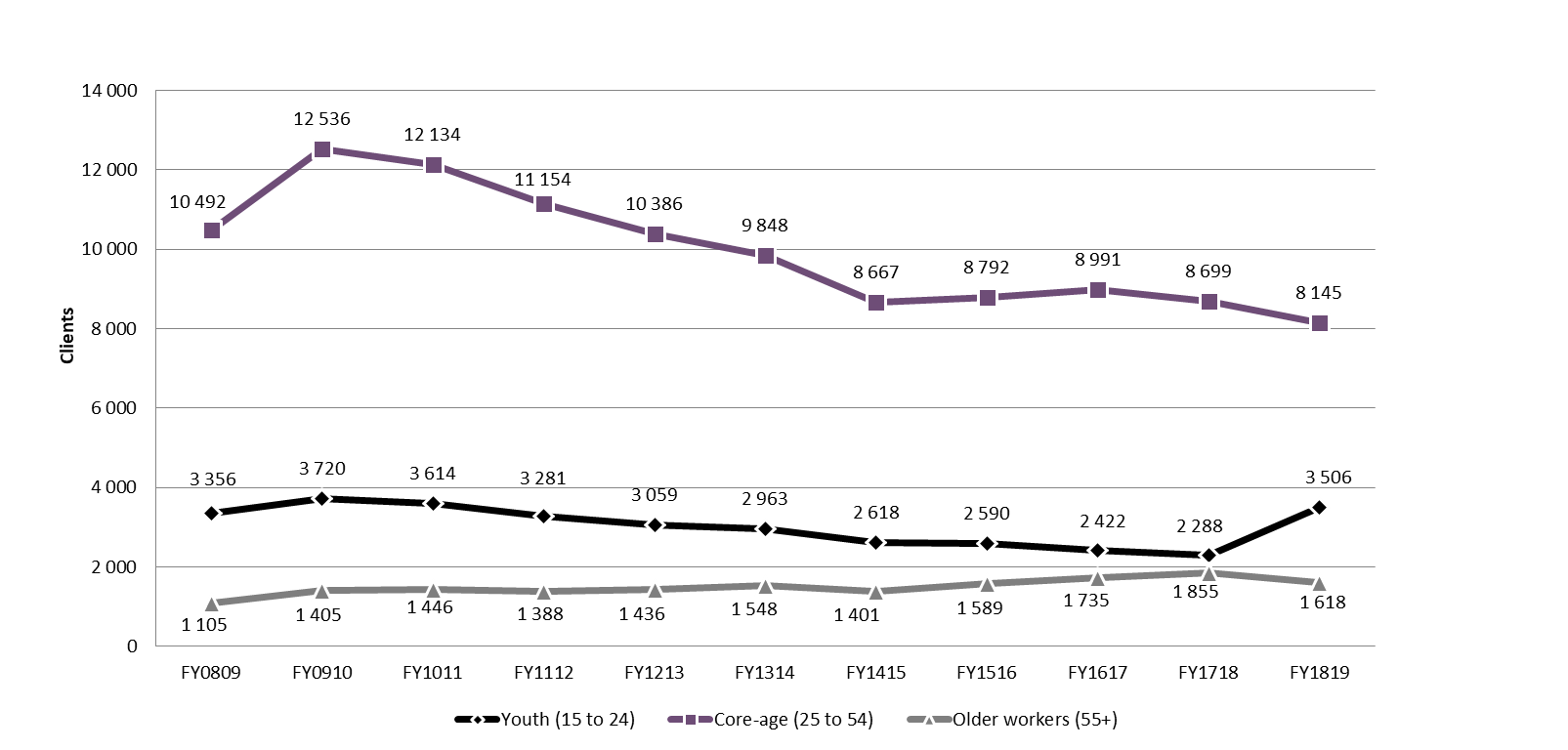

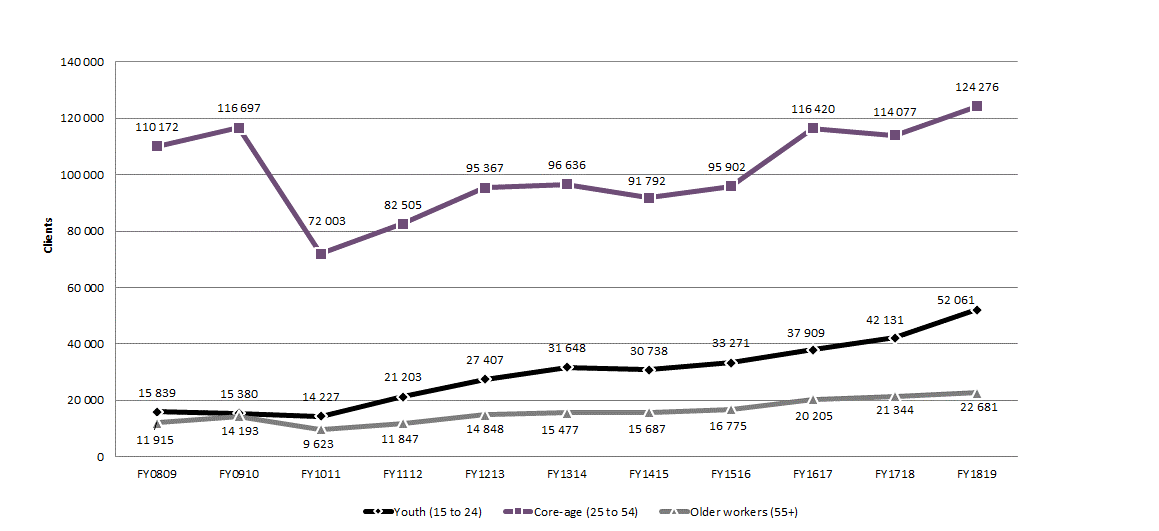

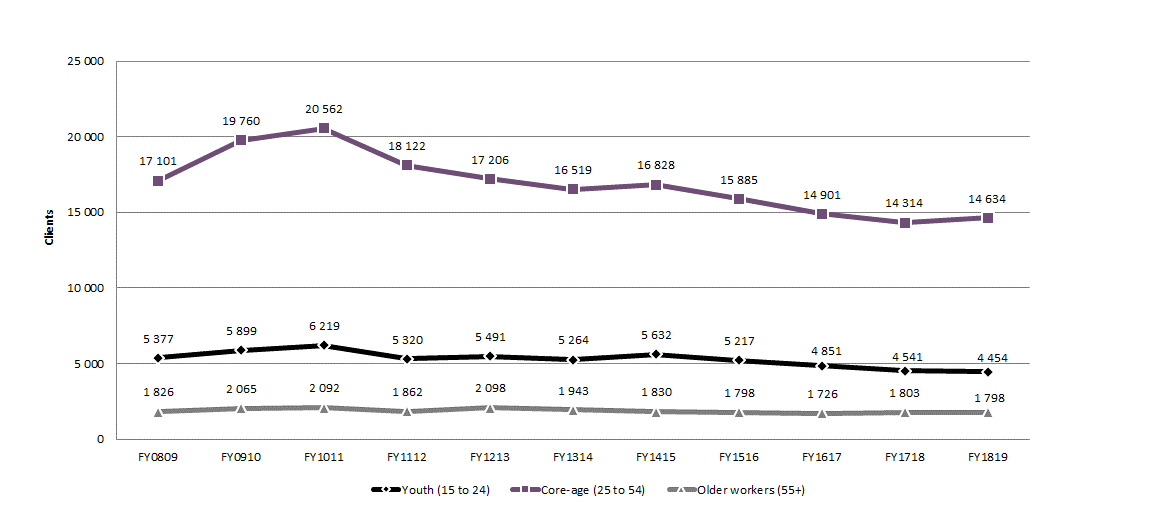

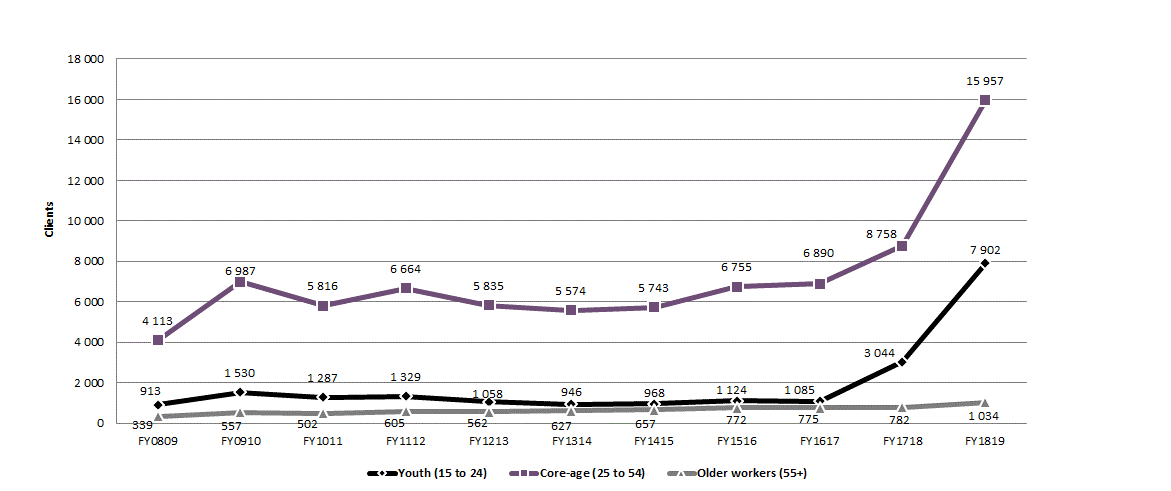

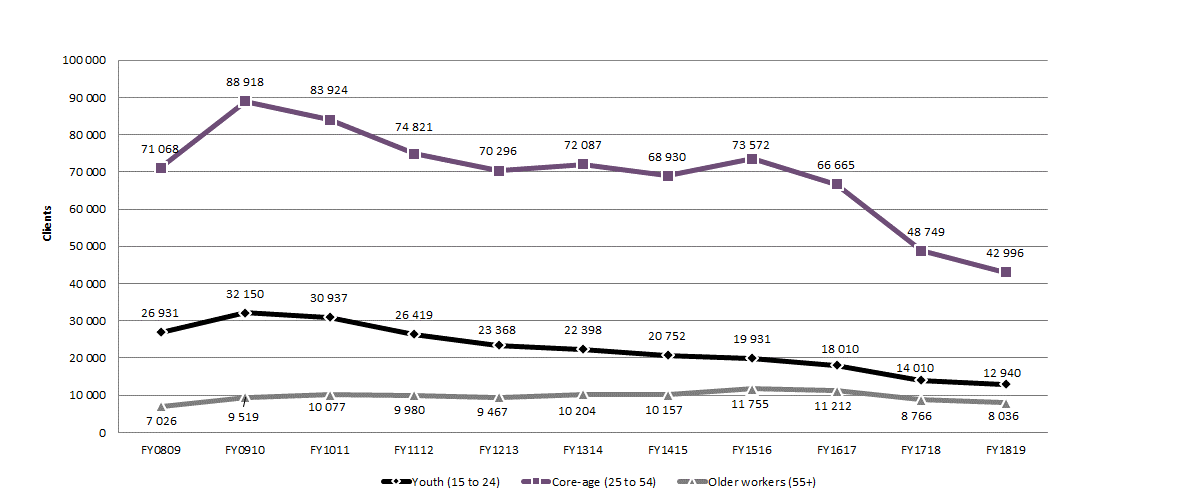

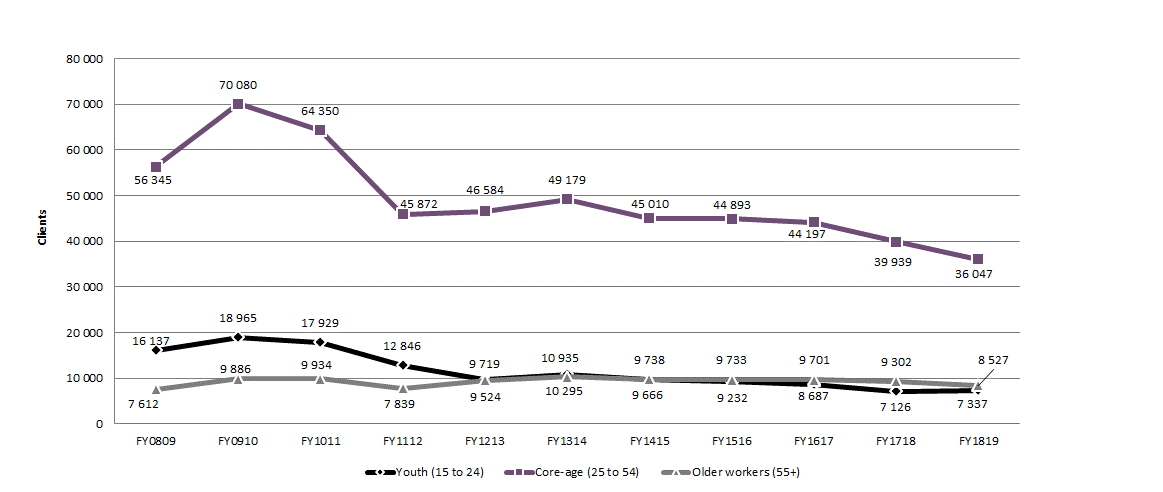

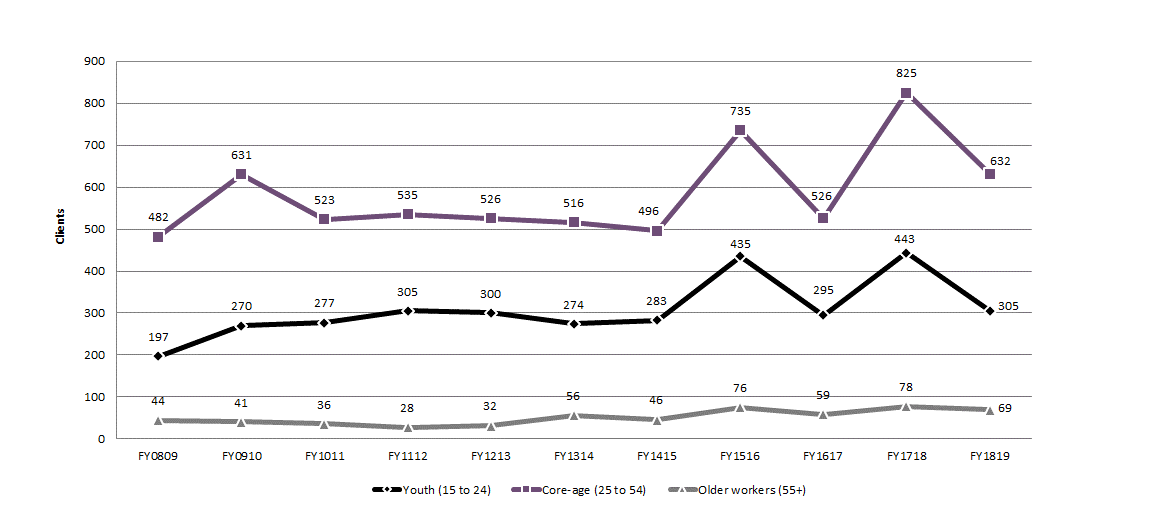

Age distributionFootnote 5

In FY1819, most EBSM clients were in their core working years (25 to 54 years old), totalling 406,743 individuals, or 63.1% of all clients. Youth - those aged 15 to 24 years old - represented 22.3% of all clients (143,684), and clients aged 55 or older were the remaining 13.4% of the shares (86,370 clients). Youth clients increased significantly by 8.2%, followed by clients aged 55 or older (+1.7%), compared to FY1718. Core-aged clients declined by 1.6% year over year. The increase in youth clients resulted in their overall shares edging up, with a decline in the share of core-aged. Whereas, clients aged 55 or older remained unchanged at 13.4% of overall client shares.

Chart 2 – Text version

| Age distribution | FY0809 | FY0910 | FY1011 | FY1112 | FY1213 | FY1314 | FY1415 | FY1516 | FY1617 | FY1718 | FY1819 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth (15 to 24 years old) | 18% | 18% | 19% | 19% | 19% | 19% | 19% | 21% | 20% | 21% | 22% |

| Core-age (25 to 54 years old) | 72% | 72% | 70% | 70% | 70% | 69% | 68% | 67% | 67% | 66% | 63% |

| Workers (aged 55+) | 8% | 9% | 9% | 9% | 11% | 12% | 12% | 12% | 13% | 13% | 13% |

In the context of an aging labour force, the number of EBSM clients aged 55 or older increased by over 79% compared to FY0809 results. Clients aged 55 or older now represent 13.4% all total clients, compared to 8.5% a decade earlier.

Youth participation in labour market programming also increased (+38.3%) in the past 10 years, as provinces and territories prioritized serving younger people to help counter the effects of an aging population, and developing and maintaining a competitive workforce. This age cohort now represents over 22% of all clients, compared to 17.8% 10 years earlier.

Given the growth of both youth and clients aged 55 or older, the share of core-age workers (25 to 54 years old) declined over the last 10 years. Core-age workers now represent 63.1% of all clients, compared to 73.3% in FY0809.

Designated groupsFootnote 6

In support of employment equity principles, ESDC collects information on the EBSM participation of women, Indigenous peoples, members of visible minority groups and persons with disabilities. As participantsFootnote 7 voluntarily self-identify, annual fluctuations may be due to changes in self-identification rates.

- Women participated in a total of 474,830 EBSM interventions in FY1819, a 1.5% increase year-over-year (45.3% of all interventions delivered to Canadians). Women accessed predominately EAS-only interventions (88.3%); at a higher rate than men (79.4%). Among participants who were women, most were non-insured clients (39.2%), followed by active EI claimants (31.1%) and former EI claimants (18.2%). The remainder of women participants (10.4%) were under the new PPE client category.

- In FY1819, a total of 141,046 participants self-identified as persons with disabilities, an increase of 0.3% year-over-year. Persons with disabilities participated in 13.4% of all interventions delivered in FY1819. The vast majority (90.5%) participated in an EAS-only intervention, compared to 9.5% who participated in Employment Benefits.

- Indigenous peoples participated in 111,515 interventions in FY1819, representing an increase of 27.4% year-over-year. The increase is reflective of a number of jurisdictions prioritizing to serve under-represented groups and improve their employment outcomes, as well as, continued growth observed under ASETS programming. As a share of all ESBM interventions delivered in Canada, Indigenous peoples participated in 10.6% of the total, including programming delivered through ASETS. As in previous years, most Indigenous participants accessed on EAS-only interventions (93.4% of all interventions).

- Members of visible minority groups participated in 73,772 interventions in FY1819, dropping by 5.1% year-over-year. Among all interventions delivered in Canada, members of visible minority groups represented 7.0% of all participants, compared to 7.2% in FY1718. The majority of interventions (91.9%) were EAS-only, compared to 8.6% for Employment Benefits.

Official languages

To foster the full recognition and use of both English and French in Canadian society, and to help ensure that labour market programs and services are delivered in both official languages, all LMDAs contain commitments by provinces and territories to have programs and services delivered in both official languages, where there is significant demand.

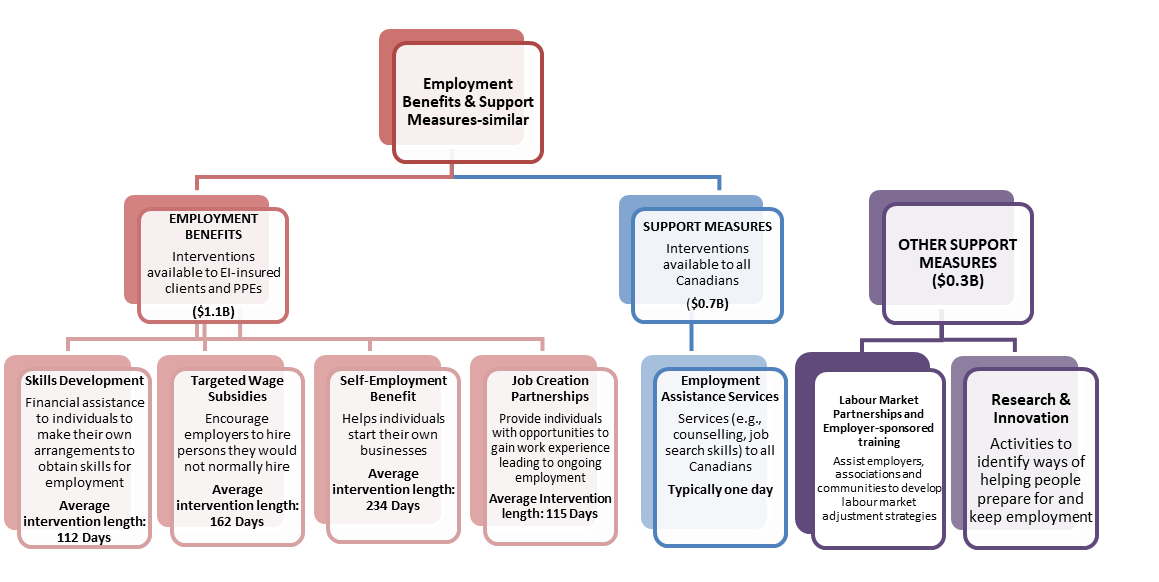

3.1.4 Interventions: Employment benefits

Employment Benefits are longer-term interventions focused on providing skills or work experience required to regain employment. Under the LMDAs, provinces and territories can provide Employment Benefits similar to the following 6 benefit types outlined in the EI Act:

- Skills Development-Regular (SD-R)

- Skills Development-Apprentices (SD-A)

- Targeted Wage Subsidies (TWS)

- Self-Employment (SE)

- Job Creation Partnerships (JCPs), and

- Targeted Earnings Supplements (TES)Footnote 8

In FY1819, Employment Benefit interventions totalled 164,442, a significant increase of 16.0% compared to the previous reporting period. With strong labour market conditions and a decline in EBSM interventions, the rise of Employment Benefits suggests provinces and territories focused on longer-term training and skills development investments. The average length of an Employment Benefit intervention was 125 days in FY1819, on average, longer than the duration observed in previous reporting periods.

Table 2 - Text version

Table 2 - Text version

- Employment benefits and support measures similar

- Employment benefits: Interventions available to EI-insured clients and PPEs ($1.1B):

- Skills Development: Financial assistance to individuals to make their own arrangements to obtain skills for employment. Average intervention length: 112 Days

- Targeted Wage Subsidies: Encourage employers to hire persons they would not normally hire. Average intervention length: 162 Days

- Self-Employment benefit: Helps individuals start their own businesses. Average intervention length: 234 Days

- Job Creation Partnerships: Provide individuals with opportunities to gain work experience leading to ongoing employment. Average Intervention length: 115 Days

- Support measures: Interventions available to all Canadians ($0.7B):

- Employment Assistance Services: Services (for example, counselling, job search skills) to all unemployed individuals. Typically 1 day

- Other support measures ($0.3B):

- Labour Market Partnerships and Employer-sponsored training: Assist employers, associations and communities to develop labour market adjustment strategies

- Research & Innovation: Activities to identify ways of helping people prepare for and keep employment

- Employment benefits: Interventions available to EI-insured clients and PPEs ($1.1B):

SD-R interventions dramatically increased, by 30.5%, to a total of 72,226, while SD-A interventions increased by 4.9%, to a total of 65,323 in FY1819. Combined, Skills Development interventions made up 83.6% of all Employment Benefits, and Skills Development expenditures totalled $877.7 million, an increase of 5.8%, or $48.1 million, compared to FY1718 results.

In FY1819, TWS interventions shot up by 23.1% year-over-year, to 18,793, and represented 11.4% of all Employment Benefits. Corresponding with this increase, expenditures on TWS programming totalled $142.4 million, an increase of $32.5 million in spending compared to the previous fiscal year.

The number of SE interventions rose by 1.7%, to 4,978, with their shares among all Employment Benefits representing 3.0%. However, SE expenditures decreased in FY1819; going from $61.6 million in FY1718, to $60.6 million in the current reporting year.

Overall, JCP interventions totalled 3,122, dropped by 1.7% year over year. JCP expenditures edged up to $34.0 million, compared to $37.0 million in the previous year.

| Employment benefits | Interventions | Share of Employment benefits | Year-over-year change | Expenditures ($ thousands) |

Estimated cost per intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted Wage Subsidies | 18,793 | 11.4% | +23.1% | $142.4 | $7,575 |

| Self-Employment | 4,978 | 3.0% | -13.4% | $60.6 | $12,180 |

| Job Creation Partnerships | 3,122 | 1.9% | +1.7% | $34.0 | $10,904 |

| Skills Development-Regular | 72,226 | 43.9% | +30.5% | $877.7 | $6,381 |

| Skills Development-Apprentice | 65,323 | 39.7% | +4.9% | ||

| Canada | 164,442 | 100% | +16.0% | $1,114.8 | $6,779 |

3.1.5 Interventions: Support measures

Part II of the Employment Insurance Act authorizes 3 support measures:

- Employment Assistance Services (EAS)

- Labour Market Partnerships (LMPs), and

- Research and Innovation (R&I)

Under the LMDAs, provinces and territories deliver these measures at regional and local levels, while ESDC retains responsibility for pan-Canadian delivery of LMPs and R&I (see section 4: Pan-Canadian Activities and the National Employment Service). However, LMPs and R&I are generally not associated with direct client services, so counts on participants or interventions are not available. The EAS component of support measures provides a full range of self-help and assisted services, such as support in determining career objectives through employment counselling, improving job search techniques, completing a return-to-work action plan and accessing labour market information in support of career choices.

Employment Assistance Services

EAS interventions provide crucial support to those who have been absent from the labour market for an extensive period or who have low job attachment. They may also support new immigrants or young people who are entering the Canadian labour market for the first time. These interventions are reported in one of the 3 following categories:

- Employment services

- Group services, or

- Individual counselling

In FY1819, a total of 859,051 EAS interventions were delivered, a decrease of 7.6% year-over-year. Total expenditures on EAS increased by 1.6% compared to the previous year, to a total of $705.4 million.

Employment services interventions continued to be the most common EAS intervention type, accounting for 58.8% of all EAS interventions in FY1819. A total of 505,182 employment services interventions were delivered, a decrease of 5.9% year-over-year. Group services dropped by 14.1%, for a total of 18,698 interventions delivered. In turn, the share of group services among all EAS-type interventions edged down to 2.2%, compared to 2.3% in the previous year. Individual counselling is particularly important when supporting clients who face barriers to employment, and often need action plans as a pathway to Employment Benefits. A total of 335,171 interventions were delivered in FY1819, declining by 9.7% year-over-year.

Other support measures

The Labour Market Partnership (LMP) measure facilitates collaboration between employers, employees and employer associations, as well as community groups and communities to develop solutions to labour force imbalances, such as persistent high unemployment or skill shortages. Under LMPs, employer-sponsored training includes assistance to employers to support approved training activities for employees in order to maintain their employment. This may include employees affected by technological or structural changes in the economy. In FY1819, LMP expenditures totalled $253.4 million, increasing by 47.4% year-over-year.

Research and Innovation (R&I) initiatives identify better ways of helping people prepare for, return to or maintain employment and participate productively in the labour force. In FY1819, R&I expenditures totalled $94 million, compared to $320.3 million in the previous year.

| Employment Assistance Services* and other support measures | Interventions | Share of employment support measures | Year-over-year change | Expenditures ($ thousands) |

Estimated cost per intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment services | 505,182 | 58.8% | -5.9% | n/a | n/a |

| Group services | 18,698 | 2.2% | -14.1% | n/a | n/a |

| Individual counselling | 335,171 | 39.0% | -9.7% | n/a | n/a |

| Total Employment Assistance Services | 859,051 | 100% | -7.6% | $705.4 | $821 |

| Labour Market Partnerships | n/a | n/a | n/a | $253.4 | n/a |

| Research & Innovation | n/a | n/a | n/a | $94.0 | n/a |

| Canada | 859,051 | 100% | -7.6% | $1,052.8 | n/a |

*Expenditures for Employment Assistance Services are reported at the aggregate level by most provinces and territories.

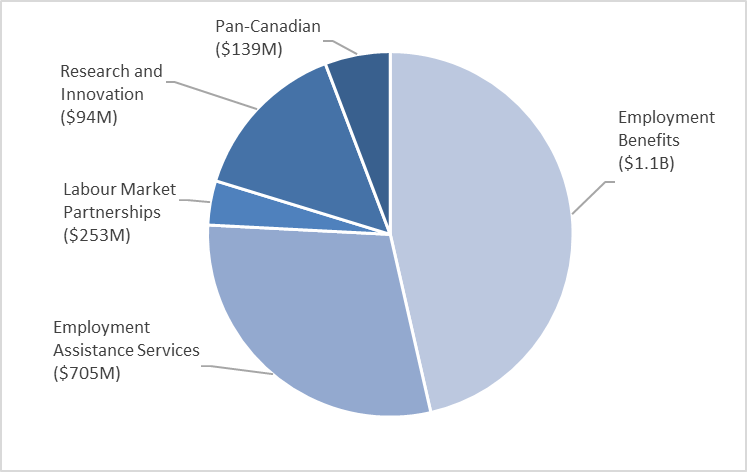

3.1.6 Expenditures

Total expenditures under Part II of the Employment Insurance Act were $2.6 billion in FY1819, which included EBSM programming, and pan-Canadian activities. This represented an increase of 18.4% compared to the previous year.

Under the LMDAs, Employment Benefits remained the largest investment, at $1.115 billion, representing more than half of expenditures by provinces and territories. Compared to FY1718, spending on Employment Benefits increased by over $80 million (+7.7%). Employment Assistance Services expenditures increased as well, up 1.6%, to a total of $705.4 million.

Chart 3 – Text version

| Expenditures | Total |

|---|---|

| Employment benefits | $1.1B |

| Employment Assistance Services | $705M |

| Labour Market Partnerships | $253M |

| Research and Innovation | $94M |

| Pan-Canadian | $139M |

Expenditures towards LMPs and R&I measures increased, going from $320.3 million in FY1718, to $347.4 million in FY1819 (+8.4%).

Pan-Canadian expenditures increased significantly (+15.6%), increasing from $120.2 million in FY1718 to $139.0 million in FY1819. See section 4 of this chapter for details on Pan-Canadian activities.

Targeted measures under LMDAs in FY1819

In FY1819, the Government of Canada made available additional time-limited targeted funding under LMDAs to support workers and communities affected by duties and tariffs imposed by the United States on Canadian softwood exports, as well as steel and aluminum products. In addition, Budget 2018 announced additional funding to assist workers in seasonal industries. For FY1819, nearly $75 million was available to provinces and territories under these 3 measures:

- $20.5M for workers in seasonal industries

- $25M for workers affected by steel and aluminum trade dispute, and

- $29.1M for workers affected by the softwood lumber trade dispute

Provinces and territories accessed roughly $59 million of the total to support workers with LMDA-funding programming. For example, British Columbia used some of the funding towards 6 projects offering skills training and work experience in communities affected by the softwood lumber downturn.

To support workers, provinces and territories accessed more than $59M under the 3 targeted measures of the $75M made available in FY1819.

SkillsAdvance Ontario supported laid off steel and aluminum workers with training during rotating and temporary plant shutdowns to deal with reduced business, resulting from US-imposed steel tariffs, skilled labour shortages and a surge in imports from non-NAFTA countries.

Newfoundland and Labrador used additional funding for workers in seasonal industries to respond to circumstances such as industry closures and downsizing in fish processing. Through the Fish Plant Worker Program, the Province focused on creating short-term employment with wage subsidy supports for workers impacted by the downturn in the fishing sector.

In Nova Scotia, Workplace Initiatives worked with the Fishery and Tourism industries and other government partners to develop innovative approaches for seasonal workers. This included symposia to understand the needs and challenges in relation to seasonal work in these industries.

More information on the additional targeted funding measures is available in section 2 of this chapter.

3.1.7 Key performance indicatorsFootnote 9

FY1819 Employment benefits and support measures key facts

For accessibility reasons, the table has been simplified. Consult the PDF version for the full table.

| EI Active, Former, and Premiums-Paid Eligible (LMDA) | Non-insured clients (LMDA) | Pan-Canadian1 |

|---|---|---|

| 455,535 | 240,075 | 25,179 |

1 EI Part II Pan-Canadian services to individuals are through the Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy.

| Active claimants | Former claimants | PPEs | Pan-Canadian2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 41.1% | 14.6% | 9.7% | 34.5% |

| Youth clients (15-24)2 | Core age workers (25-54)2 | Clients aged 55 or older2 | |

| 22.3% | 63.1% | 13.4% |

2 Age distribution does not equal 100%, as the “unknown” category is not reported here. Date of birth is not collected for clients in SD-Apprentices and Group Services.

| Interventions | FY1819 | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 164,442 | 16.0%  |

| Support Measures: EAS | 859,051 | 7.6%  |

| Pan-Canadian | 44,498 | 24.1%  |

| Relative share | FY1819 | Year-over-year change (p.p.) |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 16.1% | 3.0  |

| Support Measures: EAS | 83.9% | 3.0  |

| Expenditures | FY1819 ($ million) |

Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | $1,114.8 | 7.7%  |

| Support Measures: EAS | $705.4 | 1.6%  |

| LMPs and R&I | $347.4 | 8.4%  |

| Pan-Canadian | $408.6 | 240%  |

| Total Expenditures | $2,618 | 18.4%  |

3 Totals may not add up exactly due to rounding; accounting adjustments are not included.

| Indicator | Total | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Active Claimants Served | 286,197 | 8.9%  |

| Returns to Employment | 190,754 | 7.6%  |

| Estimated Unpaid Benefits ($ Million) | $1,071.0 | 2.9%  |

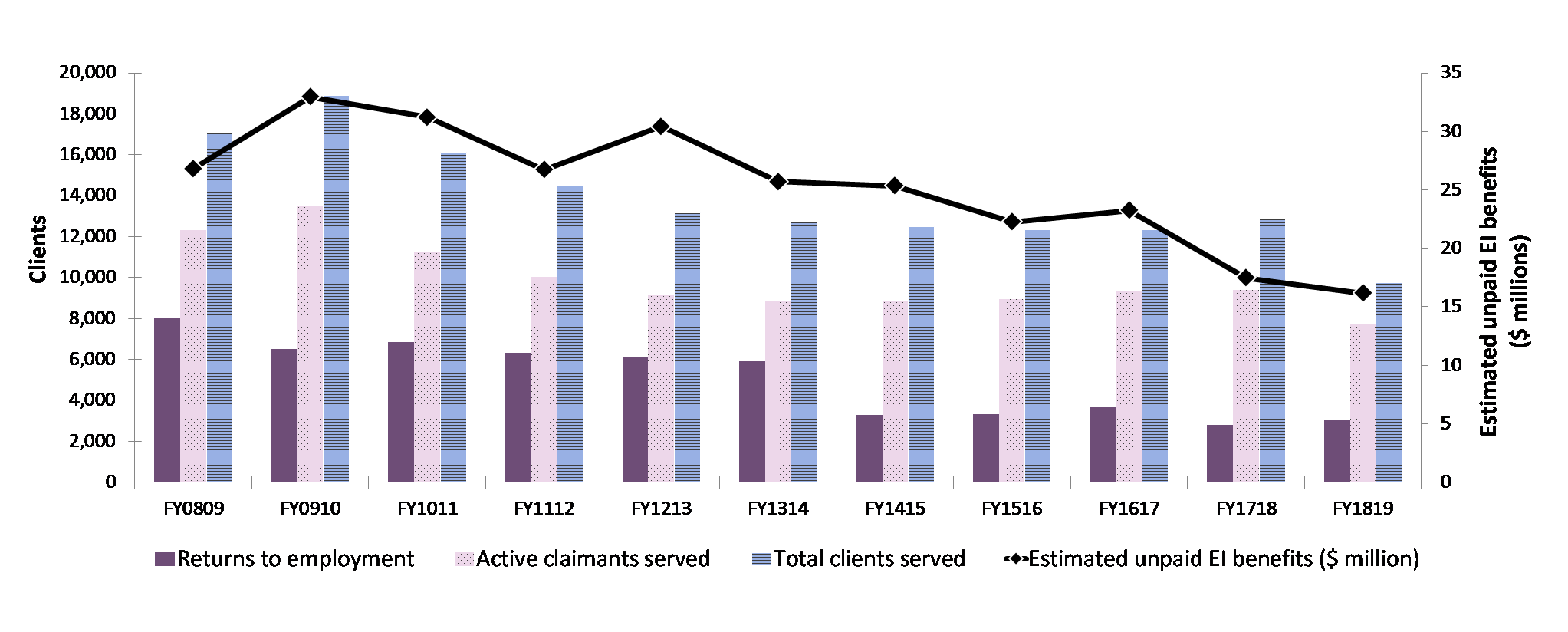

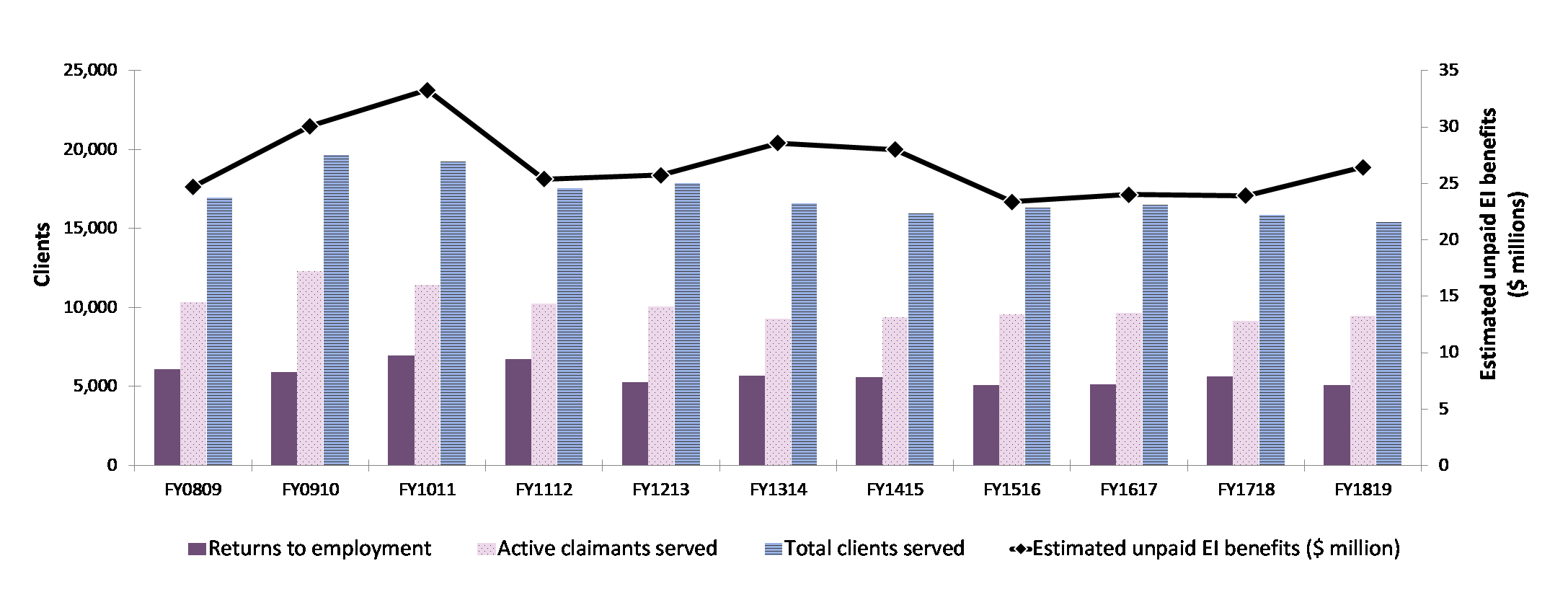

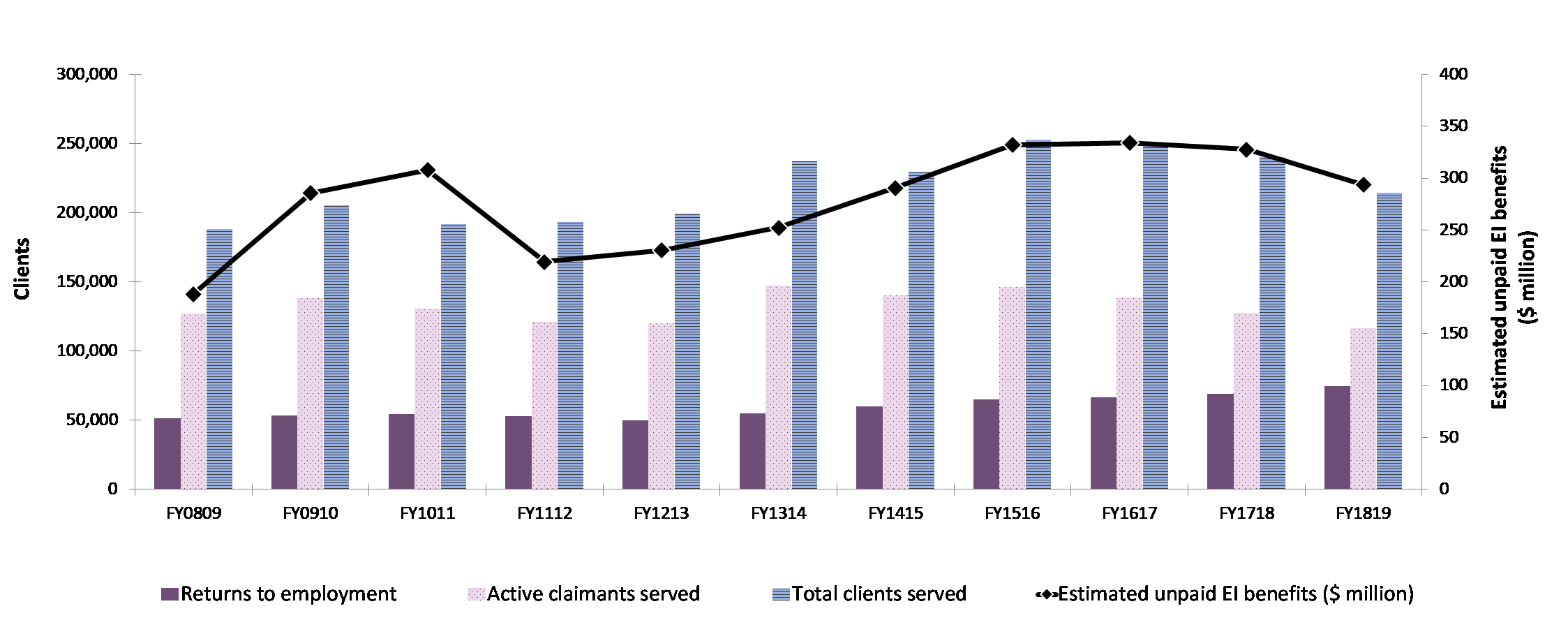

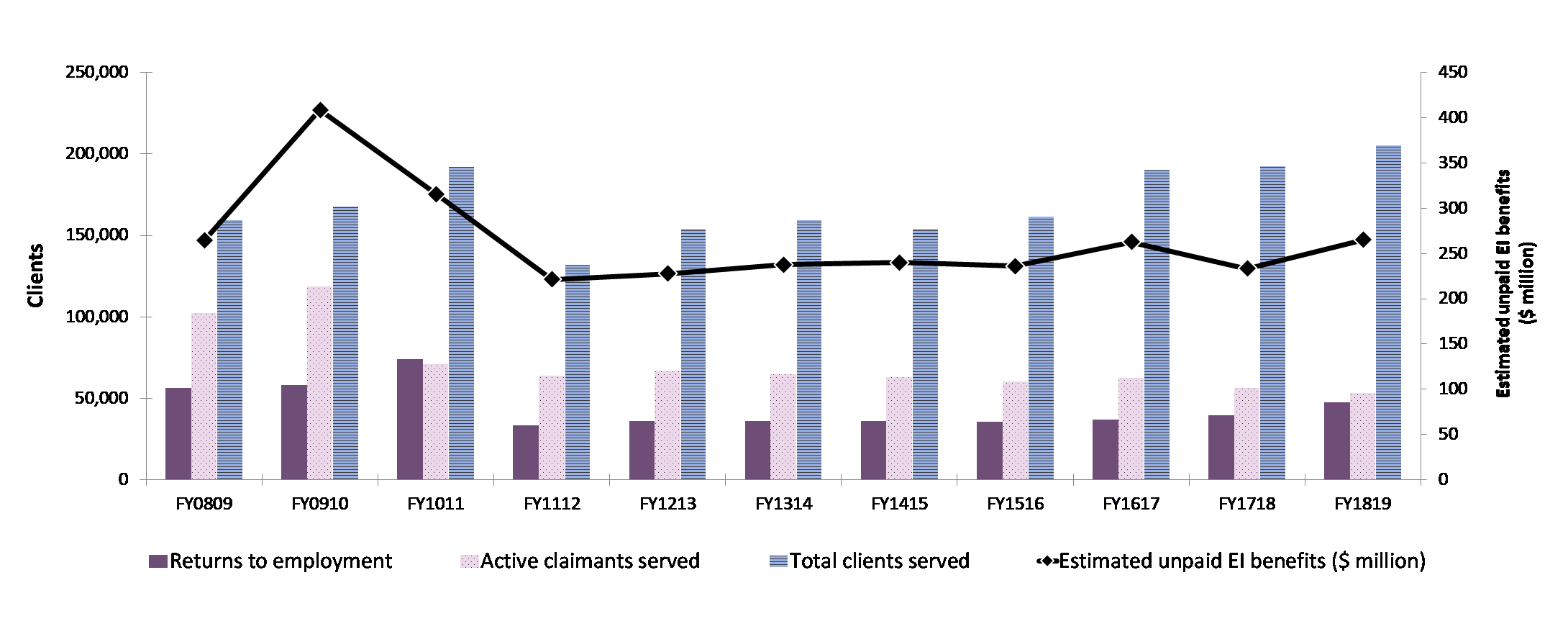

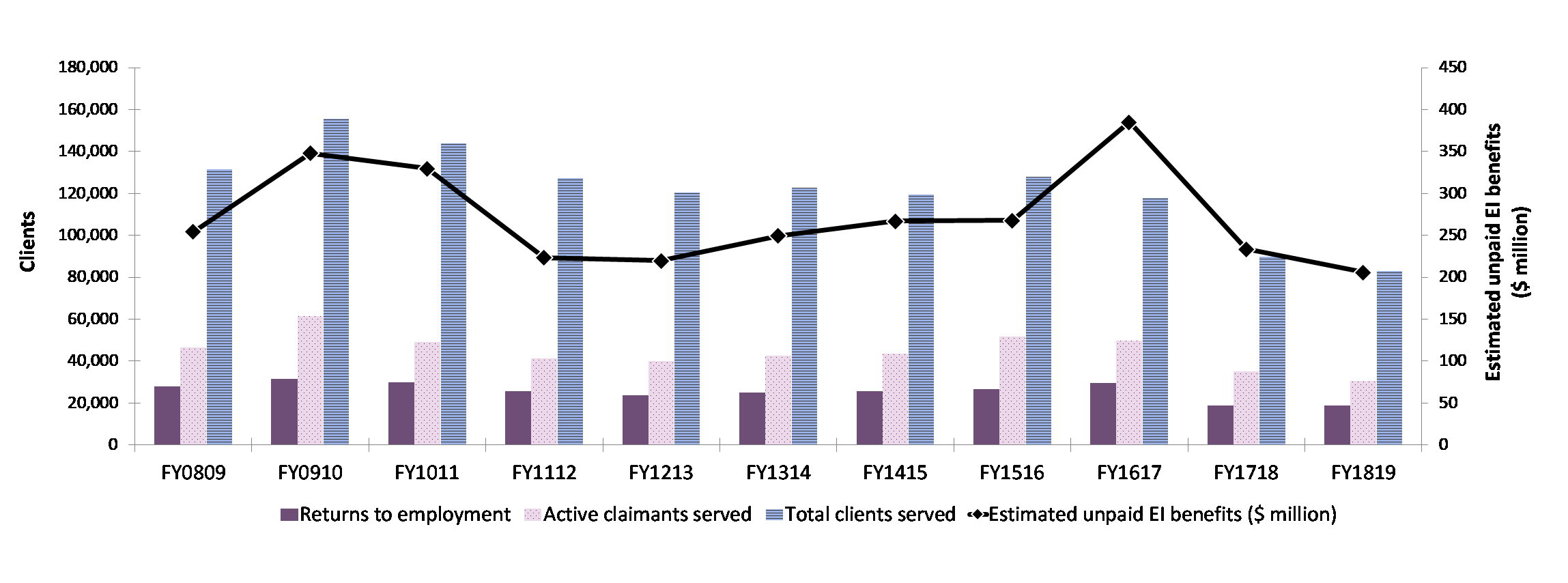

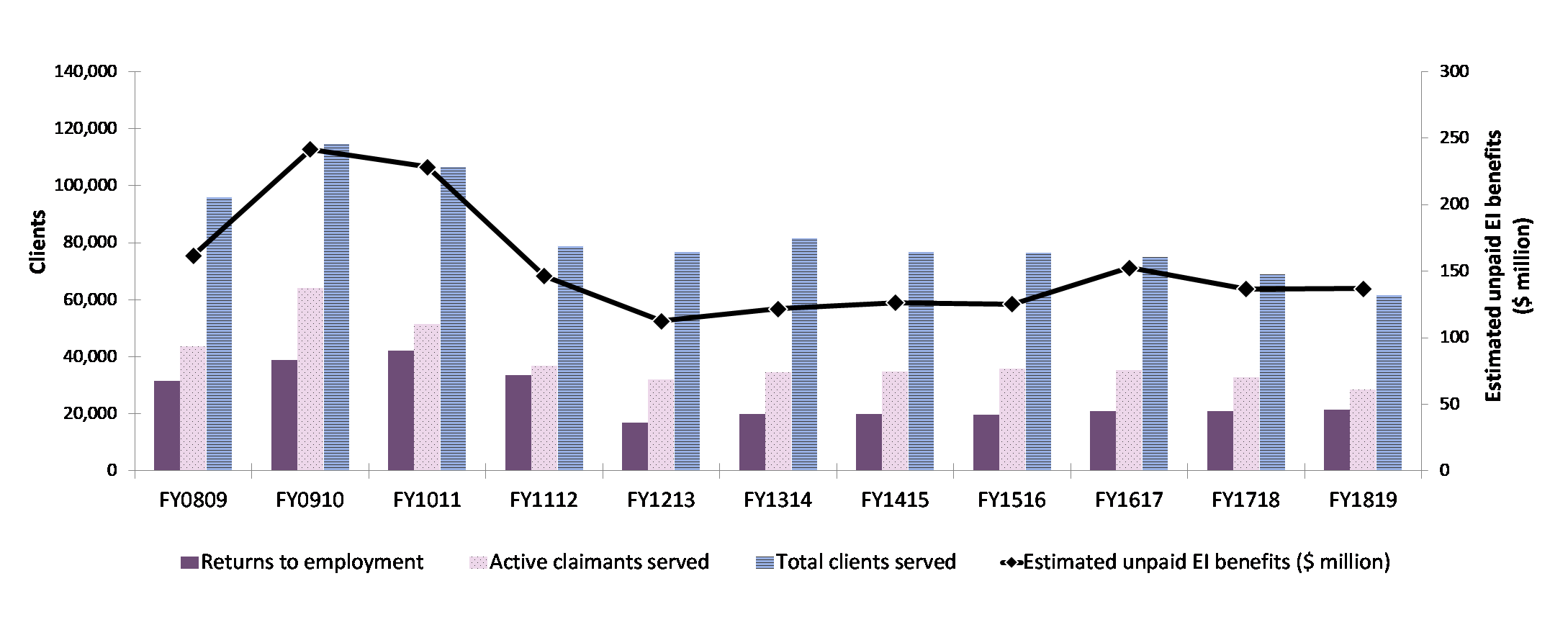

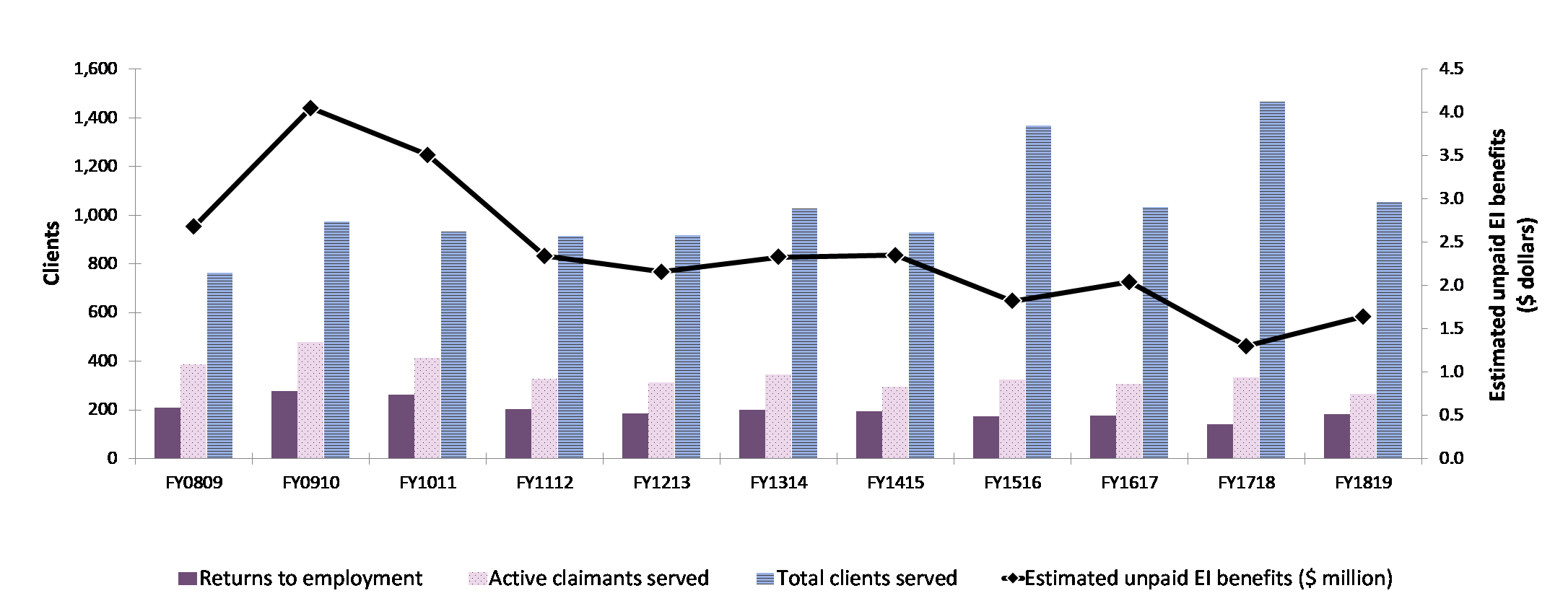

ESDC monitors the results of EBSM-similar programming delivered by provinces and territories through 3 key performance indicators:

- the number of active EI claimants servedFootnote 10

- the number of EI clients who return to employment following an intervention,Footnote 11 and

- the amount of unpaid EI Part I benefits resulting from returns to employment

In the context of improving labour market and economic conditions in FY1819 throughout most parts of Canada, the number of active EI claimants served (286,197) dropped by 8.9% year-over-year. Returns to work increased by 7.6% year-over-year, with a total of 190,754 clients finding employment within 6 months of completing their interventions. Stemming from the declines in active EI claimants, unpaid EI Part I benefits totalled $1.071 billion, declining by 2.9% compared to the previous year.

Table 5 presents supplementary performance indicators at the national and provincial/territorial level, contextualized with labour market aggregates. Since multiple factors can influence results at the individual, jurisdictional and national level, these indicators cannot be solely attributed to the LMDAs.

At the national level, 62.6% of active EI claimants began their first LMDA-funded intervention within 12 weeks after their Benefit Commencement Period (BCP). Compared to FY1718, this is an increase of 3.1 percentage points, where 59.5% of active claimants began within 12 weeks that year. At the provincial/territorial level, most jurisdictions experienced an increase, as well, with results ranging from 76.3% in Quebec, to 32.1% in Newfoundland and Labrador.

In FY1819, Canada's returns to work from interventions among active clients, expressed as a proportion of the country's labour force, was 1.0%. Quebec and the four Atlantic provinces were at or above the national average. At the same time, unpaid EI regular benefits stemming from returns to work, expressed as a proportion of total EI regular benefits paid, was 10.0% at the national level. Quebec, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia posted higher proportions than the national figure. Only Quebec registered above the national average for these 2 ratios. This suggests an effective and efficient balance between returning clients to work as soon as possible, while ensuring the necessary active employment services for employment success over a mid-to long-term horizon.

| Provinces and territories | Unemployment rate (FY1819) | Job vacancy rate (FY1819) | EI active claimants (%) beginning EI Part II within 12 weeks following their Part I Benefit Period Commencement* (FY1819) | Returns to work among active EI clients from EBSM interventions, as a proportion of the labour force (FY1819) | Estimated unpaid EI regular benefits resulting from EBSM interventions, as a proportion of Part I regular benefits paid (FY1819) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland & Labrador | 13.0% | 2.0 | 32.1% | 1.2% | 2.0% |

| Prince Edward Island | 9.3% | 3.6 | 60.8% | 2.9% | 4.2% |

| Nova Scotia | 7.2% | 2.7 | 54.1% | 1.0% | 4.4% |

| New Brunswick | 7.9% | 3.0 | 54.3% | 2.1% | 4.0% |

| Quebec | 5.4% | 3.2 | 76.3% | 1.7% | 11.4% |

| Ontario | 5.7% | 3.2 | 56.3% | 0.6% | 9.6% |

| Manitoba | 5.8% | 2.5 | 42.6% | 0.6% | 11.4% |

| Saskatchewan | 6.0% | 2.2 | 45.6% | 0.8% | 12.5% |

| Alberta | 6.7% | 2.8 | 63.9% | 0.7% | 15.5% |

| British Columbia | 4.7% | 4.6 | 42.0% | 0.8% | 13.8% |

| Northwest Territories | 6.9% | 3.3 | 57.3% | 0.8% | 9.9% |

| Yukon | 3.4% | 4.5 | 40.0% | 0.5% | 5.0% |

| Nunavut | 14.5% | 3.4 | 37.8% | 0.3% | 5.5% |

| Canada | 5.8% | 3.3 | 62.6% | 1.0% | 10.0% |

Source: Labour Force Survey, Business Payroll Survey, and EI administrative data.

*This includes a small percentage of clients who began EI Part II programming up to 2 weeks prior to their Part I Benefit Period Commencement. SD-A participants and those who were non-insured participants were excluded, if they had taken EAS in the previous year.

3.2. Provincial and territorial EBSM activities

In this section

- 3.2.1 Context

- 3.2.2 Newfoundland and Labrador

- 3.2.3 Prince Edward Island

- 3.2.4 Nova Scotia

- 3.2.5 New Brunswick

- 3.2.6 Quebec

- 3.2.7 Ontario

- 3.2.8 Manitoba

- 3.2.9 Saskatchewan

- 3.2.10 Alberta

- 3.2.11 British Columbia

- 3.2.12 Northwest Territories

- 3.2.13 Yukon

- 3.2.14 Nunavut

This section analyzes the provincial and territorial economic environment and EBSM-similar activities in FY1819. It links trends in clients served, interventions and expenditures to local labour market conditions, as well as employment programming priorities.

3.2.1 Context

Under the LMDAs, provinces and territories receive funding to support the delivery of programs and services, similar to the EBSMs established under Part II of the Employment Insurance Act.Footnote 12 To address unique labour market challenges, provinces and territories deliver employment programming under LMDAs, which were individually negotiated with the Government of Canada. Provinces and territories design and deliver all EI-funded active employment programming, except for pan-Canadian activities, discussed in section 4 of this chapter.

Broad-based consultations were held in FY1617 with provinces, territories and stakeholders to identify ways to improve the labour market transfer agreements and guide future investments to strengthen labour market programming. Comments received indicated a desire for agreements to be more flexible and responsive to the needs of employers and Canadians, especially those who are underrepresented in the workforce.

Budget 2017 announced new measures to rationalize and expand the existing bilateral labour market transfer agreements with provinces and territories, including the LMDAs. This included amending the EI Act to expand eligibility for Employment Benefits to include unemployed individuals who have made minimum Employment Insurance premium contributions in at least 5 of the last 10 years. In addition, eligibility for Employment Assistance Services was broadened to include both the unemployed and employed. Provinces and territories were also provided with increased flexibility to support employer-sponsored training under the Labour Market Partnerships Support Measure. These changes took effect on April 1, 2018 and were reflected in amending agreements signed with provinces and territories. These amendments can be found on the LMDA website.

In addition, the amended LMDAs require provinces and territories to consult with employer and employee organizations, as well as stakeholders representing Official Language Minority Communities, as part of their annual planning process. Provinces and territories are required to provide ESDC with lists of stakeholders consulted, key priorities coming out of the consultations, and linkages with labour market programming priorities.

Budget 2017 announced an additional $1.8 billion investment in the LMDAs over 6 years (2017-2018 to 2022-2023), to help more Canadians access EI-funded skills training and employment supports.

Overall, Canada's economy and labour market performed well in FY1819, contributing to a decline in the number of clients served and LMDA-funded interventions delivered in most Provinces and territories. Despite varying economic and labour market conditions throughout Canada, all jurisdictions prioritized improvements to the labour market attachment of underrepresented groups, such as persons with disabilities, Indigenous peoples, recent immigrants, youth, and older workers; as well as assuring employers ready access to a skilled workforce. An aging workforce and out-migration remain a particular labour market challenges for Atlantic Canada, where the Provinces worked with communities and regional stakeholders to ensure labour market programming responds to the demographic pressures.

The Managing for results section for each provincial and territorial summary highlights innovative approaches to improve outcomes for clients. These include:

- better employer engagement in setting priorities and design

- improved strategies to deliver active employment supports earlier for EI claimants, and

- innovative approaches in some jurisdictions to Research and Innovation support measures

3.2.2 Newfoundland and LabradorFootnote 13

In 2018, for a second consecutive year, Newfoundland and Labrador registered the lowest real GDP growth among all provinces and territories, with a contraction of 3.5% compared to 2017. A consensus of private sector banks projects that Newfoundland and Labrador's economic growth has surpassed the national average in 2019, increasing by about 2.0%.

Newfoundland and Labrador: EBSM key facts

For accessibility reasons, the table has been simplified. Consult the PDF version for the full table.

| Insured clients | Non-insured clients |

|---|---|

9,211 |

542 |

| Intervention type | FY1819 | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 7,246 | 9.8%  |

| Support Measures: EAS | 13,687 | 26.5%  |

| Intervention type | FY1819 | Year-over-year change(pp) |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 34.6% | 4.5  |

| Support Measures: EAS | 65.4% | 4.5  |

| Total expenditures | FY1819 ($ million) |

Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | $113.3 | 0.9%  |

| Support Measures: EAS | $10.1 | 47.2%  |

| LMP and R&I | $10.6 | 8.8%  |

| Total Expenditures2 | $134.0 | 4.0%  |

1 Newfoundland and Labrador invested $486,760 of its total allocation towards administration costs, representing almost 6.0% of the Budget 2017 additional funding the Province received in FY1819.

2 Totals may not add up due to rounding; does not include accounting adjustments.

| FY1718 | FY1819 | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| $17.47 | $16.16 | 7.5%  |

Compared to the previous fiscal year, labour market conditions improved slightly in FY1819. Employment increased by 3,700 (+1.7%), all in part-time positions, ending 5 consecutive years of decline, while the unemployment rate improved from 14.7% to 13.0%, the lowest in the past 4 years. Employment growth was concentrated in the services-producing sector (+4,400; +2.5%), led by gains in public administration (+2,400; +16.2%), wholesale trade (+1,600; +37.5%), as well as in information, culture and recreation (+1,500; +23.4%). In the goods-producing sector (-700; -1.4%), declines were recorded in most industries, led by construction (-1,200; -5.9%). This partially offset the increase in forestry, fishing, mining, quarrying, oil and gas (+1,600; +13.5%).

In an ongoing period of economic adjustment, the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador offered programs and services under its LMDA to improve the skills of residents. The aim was to address labour market demands, support displaced workers impacted by labour force adjustments and company closures, and address new and ongoing challenges and opportunities. Provincial investment priorities for FY1819 included:

- providing mechanisms to develop a highly educated and skilled workforce

- implementing initiatives to support a strong labour supply, with a focus on under-represented groups

- continuing development of a comprehensive human resource plan to support sector diversification and a productive and knowledge-intensive economy, and

- developing a responsive and adaptive workforce, through effective employment and skills training programming, with a focus on unemployed and underemployed individuals from underrepresented groups (women, persons with disabilities, Indigenous groups, youth, and mature workers)

Stakeholder engagement led to the redesign of the Targeted Wage Subsidies Program

The department engaged with stakeholders, including employers, industry, community organizations, post-secondary institutions and individuals to gain a better understanding of their labour market needs and issues. This engagement provided an opportunity to share information that was then taken into account in the redesign and implementation of labour market initiatives with a focus on providing more responsive and timely supports for clients.

As an example, these consultations led to the redesign of the department's JobsNL wage subsidy program. The subsidy amount increased, along with the duration of the subsidy, and completion bonuses were given to employers and individuals who maintained employment 10 weeks beyond the intervention completion date. Additionally, the department used information from these consultations to inform the development of other programs supported through labour market transfer agreements with a focus on priority sectors such as forestry, aquaculture, agriculture and others.

3.2.2.1 Managing for results

As 1 of the conditions of the amended LMDA, Newfoundland and Labrador is working with ESDC to implement the Targeting, Referral and Feedback (TRF) system. Evaluations of the LMDAs demonstrated that clients who accessed services in the first 2 to 3 months of their EI Part I claim had better employment and earnings outcomes, and were able to return to work more quickly. LMDA clients who were active EI claimants often did not access programs and services until 6 months or later into their claim. The TRF system will assist the Province in improving outcomes for LMDA clients. A pilot test started in February 2020.

As noted in the FY1718 Monitoring and Assessment Report, the Province contracted a third‑party service provider (Employment Options) to deliver employment counselling and case management to EI-eligible clients in the larger centres of the Province. In FY1819 Employment Options opened its first office in Grand Falls. The company has since expanded and opened offices in St. John's East, St. John's West, and Corner Brook. This increase in capacity aligns with the vision and goals of the Workforce Innovation Centre. The focus was to identify ways to better help people prepare for, find, return to, or maintain sustainable employment. Employment Assistance Services are still available at the Department's employment centres across the Province. They assist EI-eligible individuals with job searches, resume writing, labour market information, as well as career and employment needs assessments. As part of the Performance Measurement Strategy, changes were made in the Labour Market Programs Support System (LaMPSS) to capture the required reporting fields for ESDC. This increase in capacity, combined with the enhancements in LaMPSS, allowed for improved capture of data and program results. As well, the Province is working with Community Partners to make similar changes to their Accountability Resource Management System (ARMS), to better capture the required fields as outlined in the Performance Measurement Strategy. The schema was provided to the ARMS technical team, who will create xml files for each community partner. This will be sent to ESDC via secure upload. Full implementation is expected for 2020.

The province also updated its online resources to better assist clients with their career planning and job search needs. Through the Provincial SkillsPass NL Project, targeted online programs help clients secure and maintain employment. This training program will give job searchers the tools and confidence needed to find suitable employment and build their career. Every client training record associated with a client's online profile is secured in an online database allowing the client to demonstrate training completion and credential attainment. The SkillsPass Program gives career counsellors the ability to track and monitor the client's progress. Clients can complete up to 22 learning activities related to career planning and job search. The program delivers consistent service in rural and urban areas of the province, and will increase the number of clients served.

3.2.2.2 Clients, interventions and expenditures

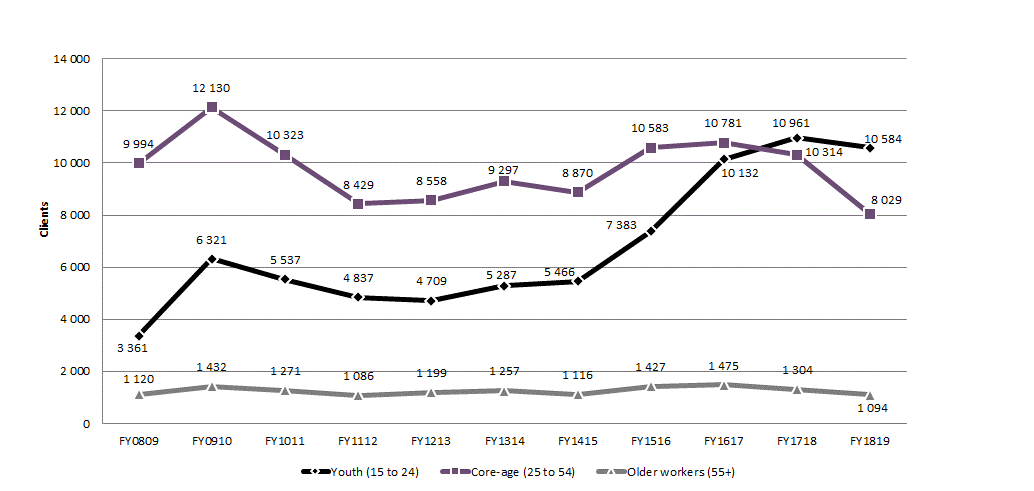

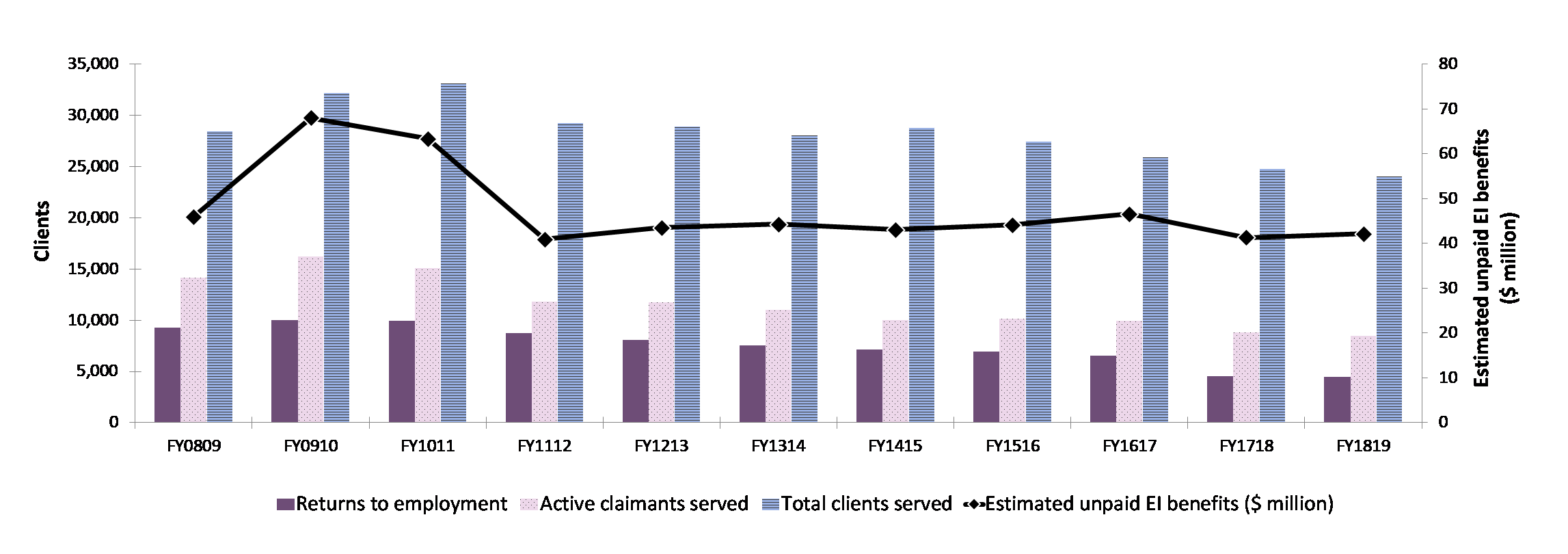

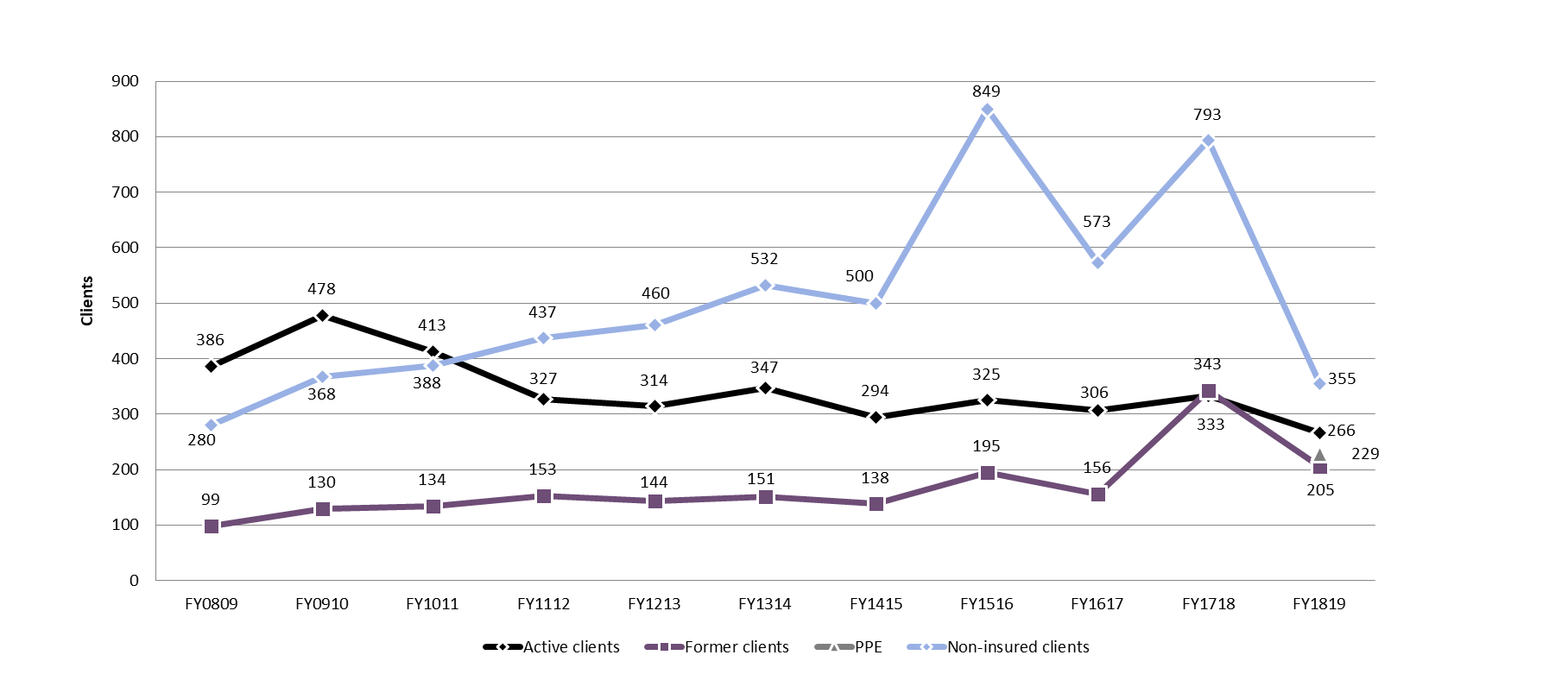

Compared to the previous fiscal year, the total number of clients served in Newfoundland and Labrador during FY1819 decreased from 12,867 to 9,753, a 24.2% year-over-year decline. The number of active claimants (-1,674; -17.8%), former claimants (-999; -42.2%) and non-insured clients (-565; -51.0%) dropped.

The new client group, Premiums-Paid Eligible (PPE), totalled 124 of all clients served by the province, and represented 1.3% of all clients. With respect to the shares of the 3 other client groups, active claimants (79.1%) increased by 6.1 percentage points, while former claimants (14.1%) and non-insured clients (5.6%) fell by 4.3 and 3.0 percentage points respectively. The decline in the proportion of non-insured clients may be attributable to the new PPE category.

The total number of EBSM-similar interventions in Newfoundland and Labrador dropped to 20,933 (‑21.5%) in FY1819, with the shares of Employment Benefits and Support Measures representing 34.6% and 65.4%, of all EBSM-similar interventions. A total of 3,055 (+9.3%) insured clients returned to employment after participating in an EBSM-similar program. Unpaid EI benefits decreased from $17.47 million to $16.16 million, representing a 7.5% year-over-year drop. EBSM total expenditures advanced by 4.0% to $134.0 million, including $7.8 million from the province's share of the additional $225.0 million LMDA investment announced in Budget 2017, as well as funding measures provided to support workers in seasonal industries ($1.6 million), and those affected by trade disputes in the steel and aluminum industries ($500,000).

The Impacted Fish Plant Worker Program is an example. The targeted program is focused on creating short-term employment for workers from fish plants deemed impacted by the downturn in the fishing sector. The Fish Plant Worker Program is administered by Municipal Affairs and Environment (MAE) as impacted fish plants are identified by the Department of Fisheries and Land Resources (FLR).Once a fish plant is identified by FLR, MAE will make contact with the plant to obtain a plant worker list, as well as, reach out to the community in which the plant is located to secure a sponsor. If another sponsor is needed to accommodate the workers of the impacted plant, then MAE will reach out again and pursue projects in other communities tied to those impacted workers.

Under the Impacted Fish Plant Worker Program, workers can work 420 hours less any insurable hours they have already accumulated in the current year.

Newfoundland and Labrador also supports directly or indirectly impacted steel and aluminum workers through the provision of similar types of supports.

One such example was the Labour Market Partnership with NewCo Metals aimed to address the human resource planning needs of the company. A company was hired to conduct onsite training at the Newco's newly constructed processing facility at Foxtrap. There were 3 main components within Newco's training plan. The first component was provided by Wendt Industries, suppliers of the shredder and the downstream ancillary equipment. This highly specialized equipment enables the secondary processing of metal products, the first and only of its kind in Newfoundland and Labrador.

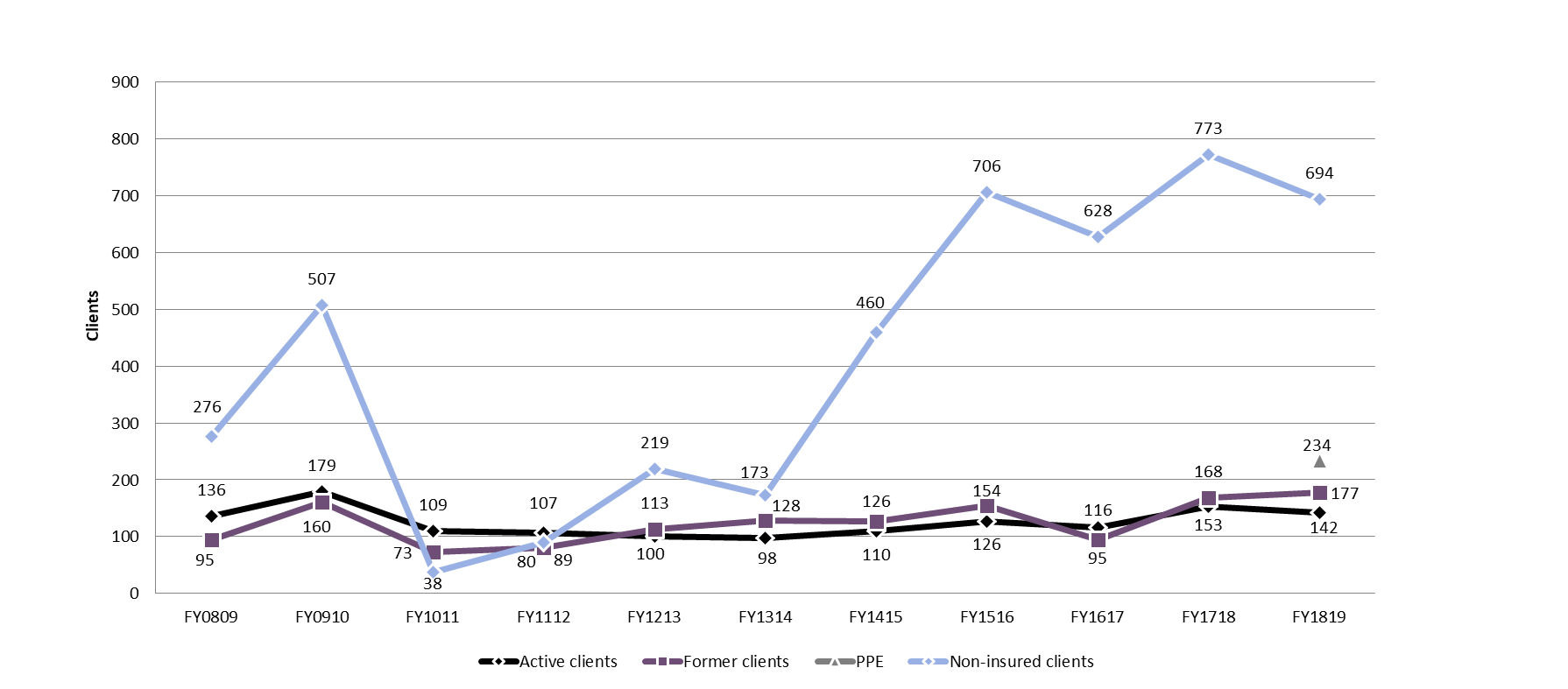

Chart 4 – Text version

| Client type | FY0809 | FY0910 | FY1011 | FY1112 | FY1213 | FY1314 | FY1415 | FY1516 | FY1617 | FY1718 | FY1819 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active claimants | 12,325 | 13,466 | 11,215 | 10,027 | 9,124 | 8,831 | 8,850 | 8,941 | 9,308 | 9,390 | 7,716 |

| Former claimants | 2,204 | 3,114 | 2,748 | 2,405 | 1,992 | 1,928 | 2,513 | 2,095 | 1,812 | 2,370 | 1,371 |

| PPE | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 124 |

| Non-insured clients | 2,561 | 2,302 | 2,171 | 2,031 | 2,046 | 1,980 | 1,126 | 1,297 | 1,232 | 1,107 | 542 |

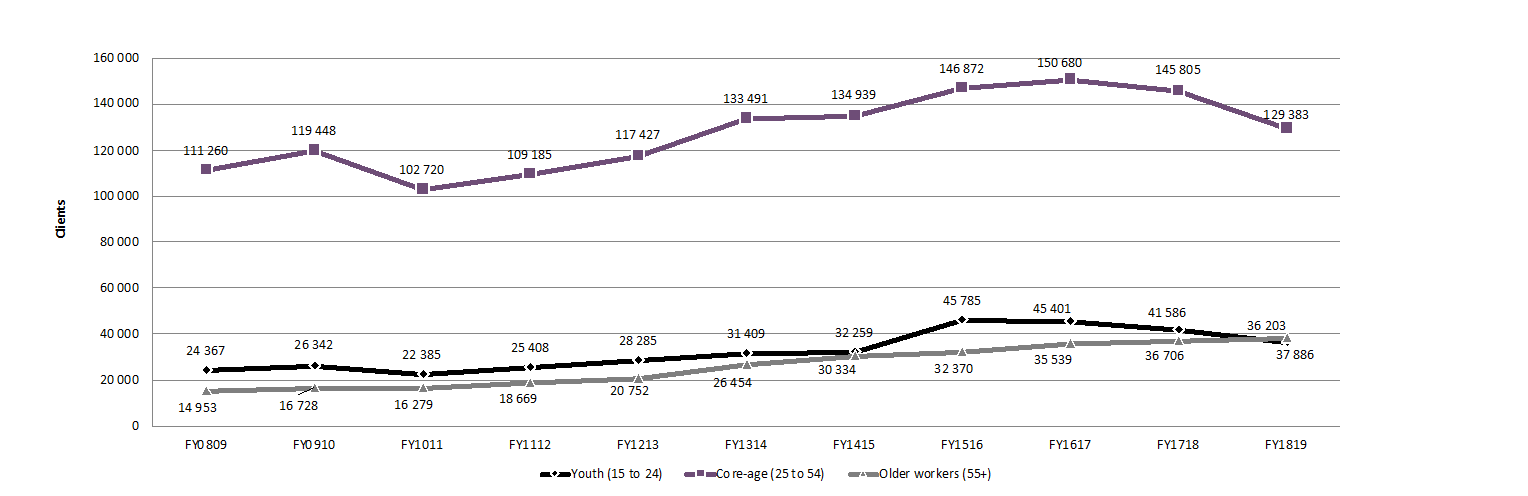

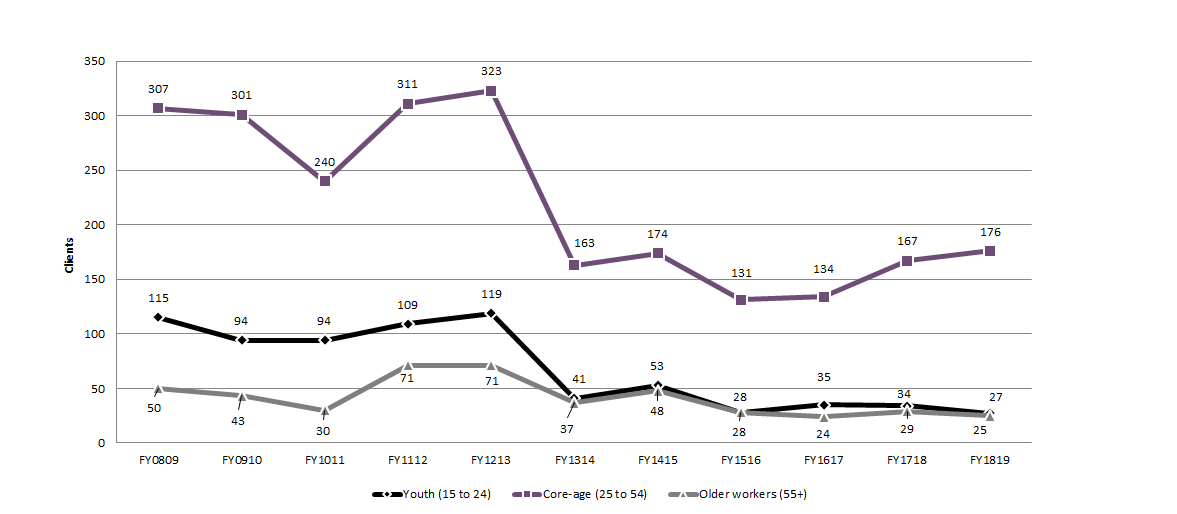

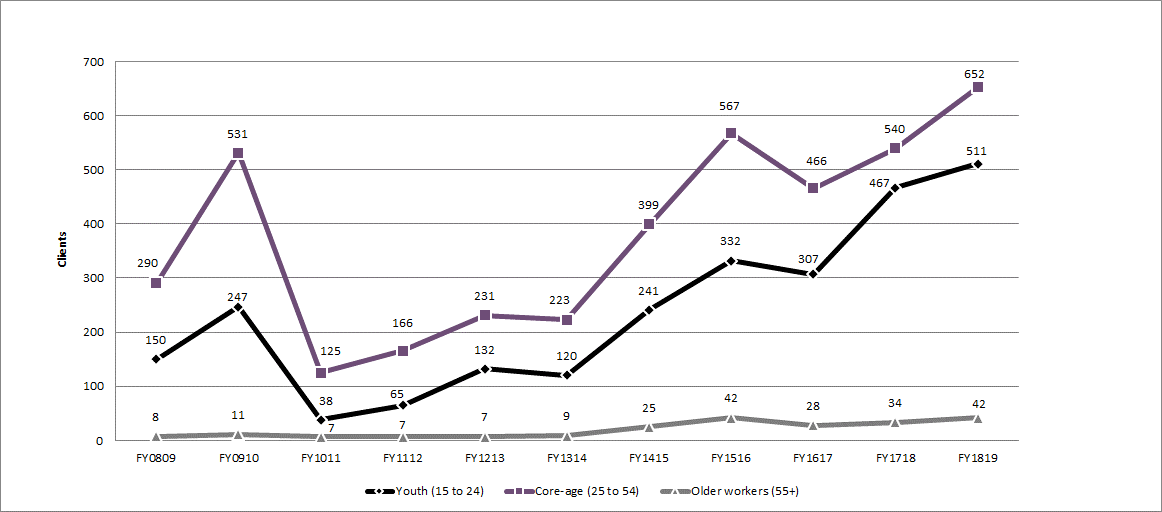

Chart 5 – Text version

| Client age | FY0809 | FY0910 | FY1011 | FY1112 | FY1213 | FY1314 | FY1415 | FY1516 | FY1617 | FY1718 | FY1819 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth (15 to 24) | 3,927 | 4,061 | 3,541 | 3,055 | 2,846 | 2,325 | 1,627 | 1,700 | 1,545 | 1,547 | 1,466 |

| Core-age (25 to 54) | 9,970 | 10,957 | 9,154 | 8,066 | 6,942 | 7,699 | 3,814 | 4,021 | 4,216 | 4,204 | 3,840 |

| Older workers (55+) | 1,116 | 1,341 | 1,178 | 1,124 | 1,145 | 376 | 665 | 676 | 769 | 804 | 832 |

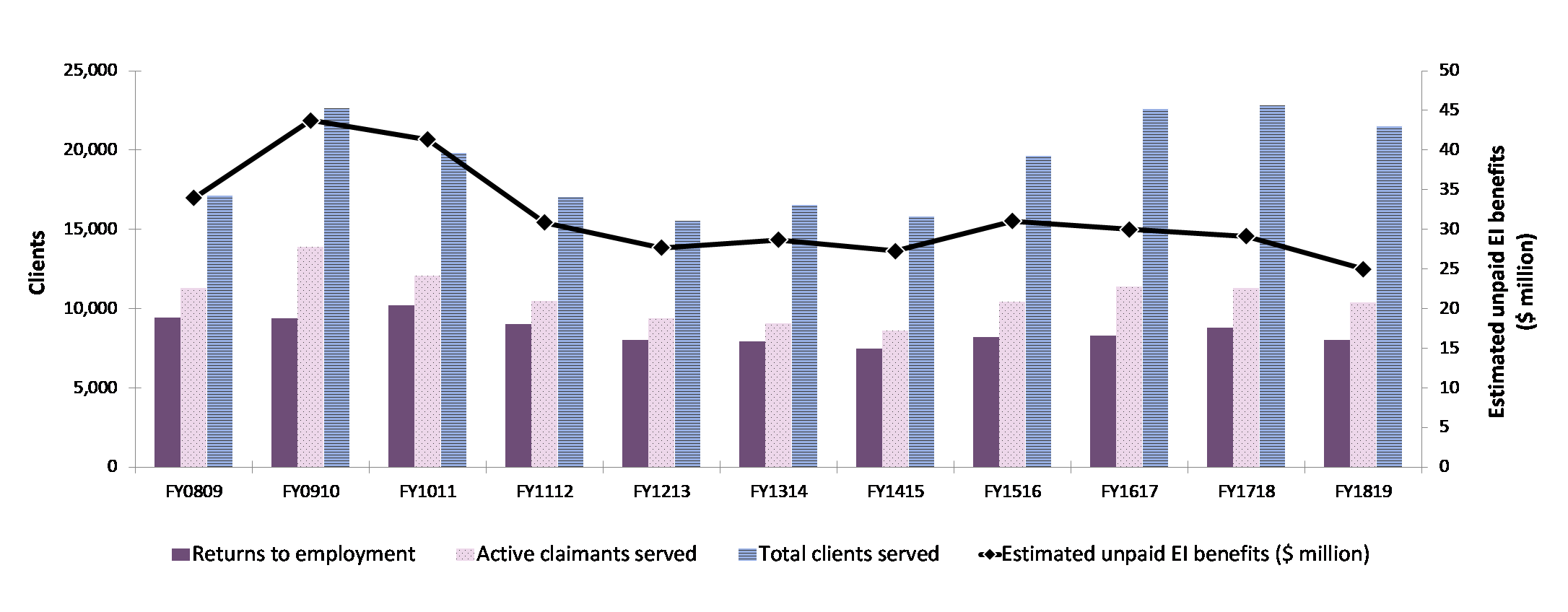

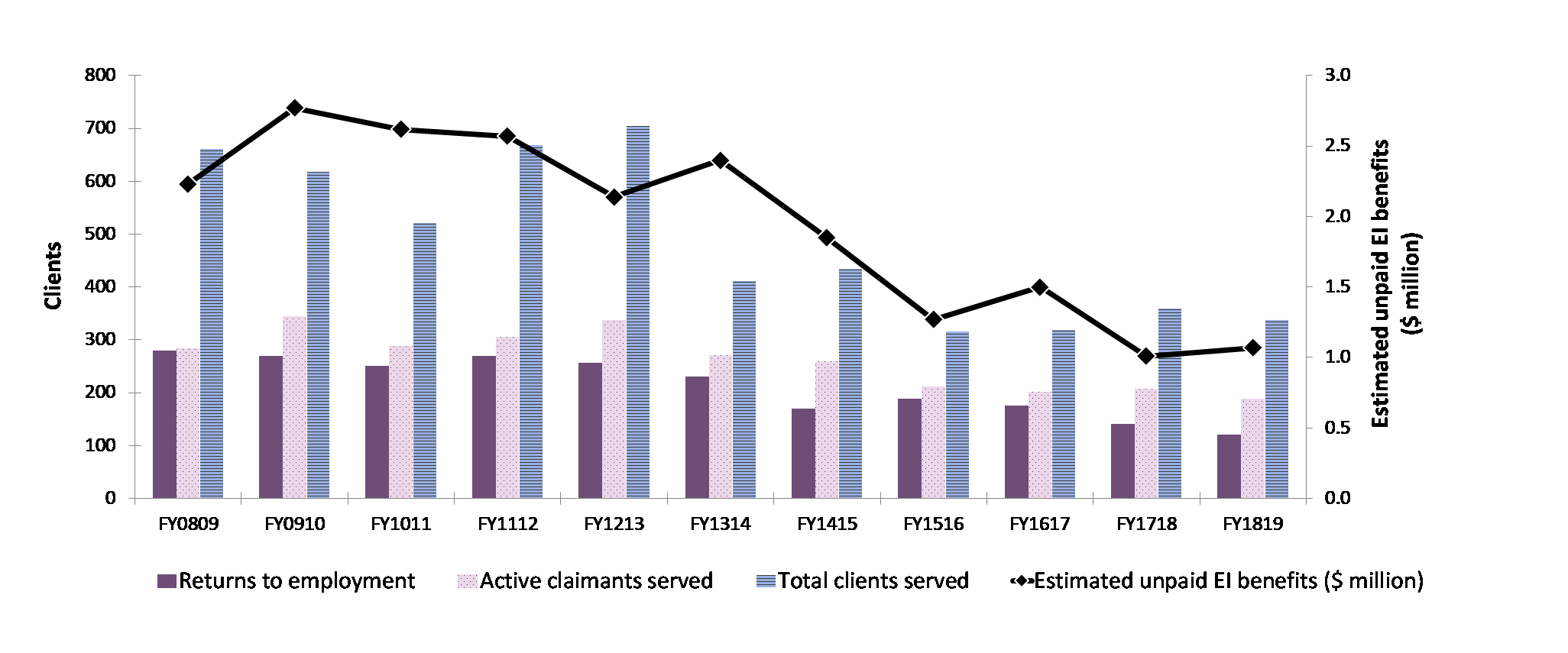

Chart 6 – Text version

| Key performance indicators | FY0809 | FY0910 | FY1011 | FY1112 | FY1213 | FY1314 | FY1415 | FY1516 | FY1617 | FY1718 | FY1819 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Returns to employment | 7,995 | 6,526 | 6,857 | 6,335 | 6,114 | 5,918 | 3,298 | 3,306 | 3,696 | 2,795 | 3,055 |

| Active claimants served | 12,325 | 13,466 | 11,215 | 10,027 | 9,124 | 8,831 | 8,850 | 8,941 | 9,308 | 9,390 | 7,716 |

| Total clients served | 17,090 | 18,882 | 16,134 | 14,463 | 13,162 | 12,739 | 12,489 | 12,333 | 12,352 | 12,867 | 9,753 |

| Estimated unpaid EI benefits ($ million) | $26,83 | $32,94 | $31,20 | $26,71 | $30,42 | $25,69 | $25,35 | $22,25 | $23,23 | $17,47 | $16,16 |

Table 6 - Newfoundland and Labrador: EBSM-similar programming, FY1819

For accessibility reasons, the table has been simplified. Consult the PDF version for the full table.

| Employment benefits | Interventions | Year-over-year change |

Expenditures ($ 000s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SD-R: Newfoundland and Labrador Skills Development | 3,244 | -10.1% | 90,792 |

| SD-A: Newfoundland and Labrador Skills Development | 1,547 | -23.1% | |

| TWS: Newfoundland and Labrador Wage Subsidies | 802 | -2.2% | 7,519 |

| SE: Newfoundland and Labrador Self-Employment Assistance | 267 | -6.6% | 6,507 |

| JCP: Newfoundland and Labrador Job Creation Partnerships | 1,386 | +5.7% | 8,509 |

| Support measures | Interventions | Year-over-year change |

Expenditures ($ 000s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EAS: Newfoundland and Labrador Employment Assistance Services | 13,687 | -26.5% | 10,060 |

| LMP: Newfoundland and Labrador Labour Market Partnerships | n/a | n/a | 7,448 |

| R&I: Research and Innovation | n/a | n/a | 3,123 |

3.2.2.3 Employment benefits

The total number of Employment benefit interventions in Newfoundland and Labrador dropped from 8,037 to 7,246 in FY1819, representing a 9.8% year-over-year decline. With the exception of JCP (+75; +5.7%), all other benefit types dropped: TWS (-18; -2.2%), SE (-19; -6.6%), SD-R (-364; -10.1%) and SD-A (-465; -23.1%). Total expenditures towards Employment Benefits ($113.3 million) remained relatively stable (+0.9%).

3.2.2.4 Support measures: EAS

After 4 consecutive years of growth, EAS interventions in Newfoundland and Labrador dropped by 26.5% to 13,687. All EAS types contributed to this decline: Employment services (-3,311; -39.4%), group services (-44; -1.2%) and individual counselling (-1,585; -24.1%). Total EAS expenditures advanced by 47.2% to $10.1 million.

3.2.2.5 Other support measures: LMP and R&I

In FY1819, Newfoundland and Labrador's total funding for LMP and R&I reached $10.6 million (+8.8%). While funding towards LMP ($7.4 million) increased by 66.1%, R&I funding ($3.1 million) declined by 40.3%.

EBSMs in action: Research and innovation - Newfoundland and Labrador

FY1819 was the second year, of the 3-year Workforce Innovation Centre funded Research and Innovation grant, to the Collective Interchange Cooperative and Canadian Career Development Foundation, for their Evidence for Community Employment Services: A Collaborative Regional Approach project. Results from this project have been positive to date with the development and implementation of the PRIME (Performance Recording Instrument for Meaningful Evaluation) front line service delivery recording tool. The initial PRIME application was developed by the Canadian Career Development Foundation. Following an initial period of studying 10 years of data and consequently tailoring the PRIME system, the project moved to targeting training and upskilling for practitioners. PRIME was implemented in 6 significant client service delivery organizations in NL. The following milestones have been achieved. PRIME is a simple tool that supports a more effective approach of tracking incremental meaningful client changes and it collected and enabled analysis of a much wider range of client outcomes and progress indicators. This resulted in information being provided to government, supervisors, frontline workers and the client themselves. Information is being used collaboratively with clients with measurable immediate effects. Based on the feedback that has been produced during the study, the Canadian Career Development Foundation was able to refine the initial PRIME 1.0 with a new release of PRIME 2.0 with a number of enhancements. This study is ongoing and set to be completed by November 2020 with the next big milestone to move further toward using PRIME to foster a culture of evidence-based decision making for services providers, government and clients.

3.2.3 Prince Edward Island

For a fourth consecutive year, in 2018, Prince Edward Island's real GDP growth surpassed the national average, increasing by 2.6%. The latest forecasts from the major banks point to a growth rate of over 2.0% for 2019.

Prince Edward Island: EBSM key facts

For accessibility reasons, the table has been simplified. Consult the PDF version for the full table.

| Insured clients | Non-insured clients |

|---|---|

4,774  |

1,595  |

| Intervention type | FY1819 | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 3,4753,946 | 5.6%  |

| Support Measures: EAS | 6,888 | 4.5%  |

| Intervention type | FY1819 | Year-over-year change(pp) |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 33.5% | 0.2  |

| Support Measures: EAS | 66.5% | 0.2  |

| Total expenditures | FY1819 ($ million) |

Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | $21.3 | 13.7%  |

| Support Measures: EAS | $4.7 | 9.2%  |

| LMP and R&I | $1.7 | 0.6%  |

| Total Expenditures2 | $27.7 | 8.3%  |

1 Prince Edward Island invested $75,240 of its total allocation towards administration costs, representing almost 3.5% of the Budget 2017 additional funding the Province received in FY1819.

2 Totals may not add up due to rounding; does not include accounting adjustments.

| FY1718 | FY1819 | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| $7.13 | $6.66 | 6.5%  |

Prince Edward Island enjoyed favourable labour market conditions in FY1819. Employment grew by 1,800 (+2.4%) year-over-year, entirely in full-time positions, to reach 76,100, marking a new high for the province. Employment in full-time positions increased by 3.9%, from 62,000 to 64,400, while employment in part-time positions decreased by 5.3%, from 12,300 to 11,600. The unemployment rate declined from 9.9% in FY1718 to 9.3% in FY1819, the lowest rate since comparable data became available in FY7677. Employment growth was the strongest in the goods-producing sector (+1,400; +7.6%), with gains in all industries, led by growth in agriculture (+700; +19.6%) and construction (+300; +5.3%). Employment in the services-producing sector advanced by 400 positions on a net basis (+0.7%), with as many industries expanding as those contracting. A notable gain was in accommodation and food services (+600; +10.7%).

Investments in labour market programs were aimed at supporting continued economic growth and prosperity in Prince Edward Island. This was achieved by ensuring that these programs continued to address labour market demand challenges and meet the needs of job seekers. The province's investment priorities for FY1819 included:

- assisting Islanders in developing the necessary skills to prepare for, find and keep employment

- continuing support for persons with disabilities to gain and maintain meaningful employment

- providing employers with an access to a skilled and diverse workforce, and

- ensuring that communities in Prince Edward Island are able to respond effectively to their own labour market opportunities and challenges

3.2.3.1 Managing for results

Prince Edward Island had a unique advantage when it came to understanding the needs and expectations of its stakeholders. Because of its small geographic size, Prince Edward Island was able to remain connected with industry, sector councils, employers and job seekers. This allowed the province to respond quickly to labour force changes.

To learn more about labour market issues and opportunities that employers across the province were facing, the Department of Education and Lifelong Learning consulted directly with key stakeholders; including sector councils and industry associations, Indigenous and Francophone communities, employment assistance providers, chambers of commerce and post-secondary institutions, and various non-profit organizations.

This consultation process provided a forum for partners to discuss labour market issues important to them and to job seekers. The collaborative effort ensured programs and services were responsive, timely, relevant, and aligned with the labour force needs of Prince Edward Island's key economic sectors.

Across the province employers, industry associations, and sector councils confirmed that a shortage of workers was one of the main areas of concern. Prince Edward Island's traditional sectors such as agriculture, fisheries, seafood processing, aquaculture, and tourism identified the lack of reliable and available labour was affecting their ability to expand their industries. Many of these industries were located in rural areas and demographic changes, such as a declining population and an aging workforce, depleted the labour supply. In response, the province continued to work closely with these sectors to attract local workers, through a variety of recruitment initiatives, with a focus on underrepresented groups such as newcomers, social assistance recipients, and Indigenous participants.

Newer sectors such as biotechnology, aerospace, advanced manufacturing, and information technology indicated challenges in accessing a skilled workforce. In this context, the province continued to invest in skills development training, by providing financial assistance to unemployed Islanders to complete training programs, to gain the skills and education necessary to find and maintain long-term sustainable employment.

3.2.3.2 Clients, interventions and expenditures

In FY1819, Prince Edward Island served 6,369 clients, a rise of 4.0% year-over-year, and the fourth consecutive year of annual growth. This growth was attributed to an increase in the number of active claimants (+137; +3.9%), combined with the 438 clients served under the new PPE category. The number of non-insured clients (-257; -13.9%) and former claimants (‑72; ‑9.2%) declined compared to FY1718. The share of active claimants remained unchanged in FY1819, at 56.9% of all clients served. The proportions of former claimants (11.2%) and non-insured clients (25.0%) declined by 1.6 and 5.2 percentage points respectively. The decline in the proportion of non-insured clients may be attributable to the new PPE category, which accounted for 6.9% of all clients served. In prior years, those clients could have been classified in the non-insured category.

For a fifth consecutive year, the number of EBSM-similar interventions in Prince Edward Island grew, reaching 10,363 in FY1819 (+4.8%). A total of 2,470 (+12.2%) insured clients returned to employment after participating in an EBSM-similar intervention. Unpaid EI benefits decreased from $7.13 million to $6.66 million, a 6.5% decline year-over-year. EBSM total expenditures reached $27.7 million (+8.3%). In addition to the province's share of the ongoing 1.95 billion dollars in LMDA program funding ($24.1 million), expenditures included its share of the additional $225.0 million envelope announced in Budget 2017 ($2.1 million). Expenditures also included the additional targeted funding provided to support workers in seasonal industries ($500,000), as well as those affected by the trade disputes in the forest sector ($500,000), and the steel and aluminum industries ($500,000).

Investments in targeted funding supported workers directly and indirectly affected by the lumber and steel-aluminum trade disputes to transition to sustainable employment through wage subsidies and training. In addition, the province received an allocation of $525,000 to support workers impacted by the seasonal nature of employment in a number of PEI's key sectors.

Chart 7 – Text version

| Client | FY0809 | FY0910 | FY1011 | FY1112 | FY1213 | FY1314 | FY1415 | FY1516 | FY1617 | FY1718 | FY1819 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active clients | 3,035 | 2,740 | 2,882 | 2,921 | 3,032 | 2,963 | 2,709 | 2,876 | 2,798 | 3,487 | 3,624 |

| Former clients | 512 | 487 | 572 | 574 | 708 | 703 | 621 | 657 | 709 | 784 | 712 |

| PPE | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 438 |

| Non-insured clients | 1,072 | 885 | 1,071 | 1,340 | 1,316 | 1,285 | 1,470 | 1,681 | 1,893 | 1,852 | 1,595 |

Chart 8 – Text version

| Age | FY0809 | FY0910 | FY1011 | FY1112 | FY1213 | FY1314 | FY1415 | FY1516 | FY1617 | FY1718 | FY1819 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth (15 to 24) | 1,060 | 950 | 1,124 | 1,202 | 1,265 | 1,259 | 1,276 | 1,456 | 1,542 | 2,309 | 2,488 |

| Core-age (25 to 54) | 2,784 | 2,504 | 2,705 | 2,937 | 3,023 | 2,920 | 2,776 | 2,954 | 3,137 | 3,072 | 2,943 |

| Older workers (55+) | 323 | 275 | 312 | 364 | 446 | 463 | 438 | 508 | 458 | 499 | 507 |

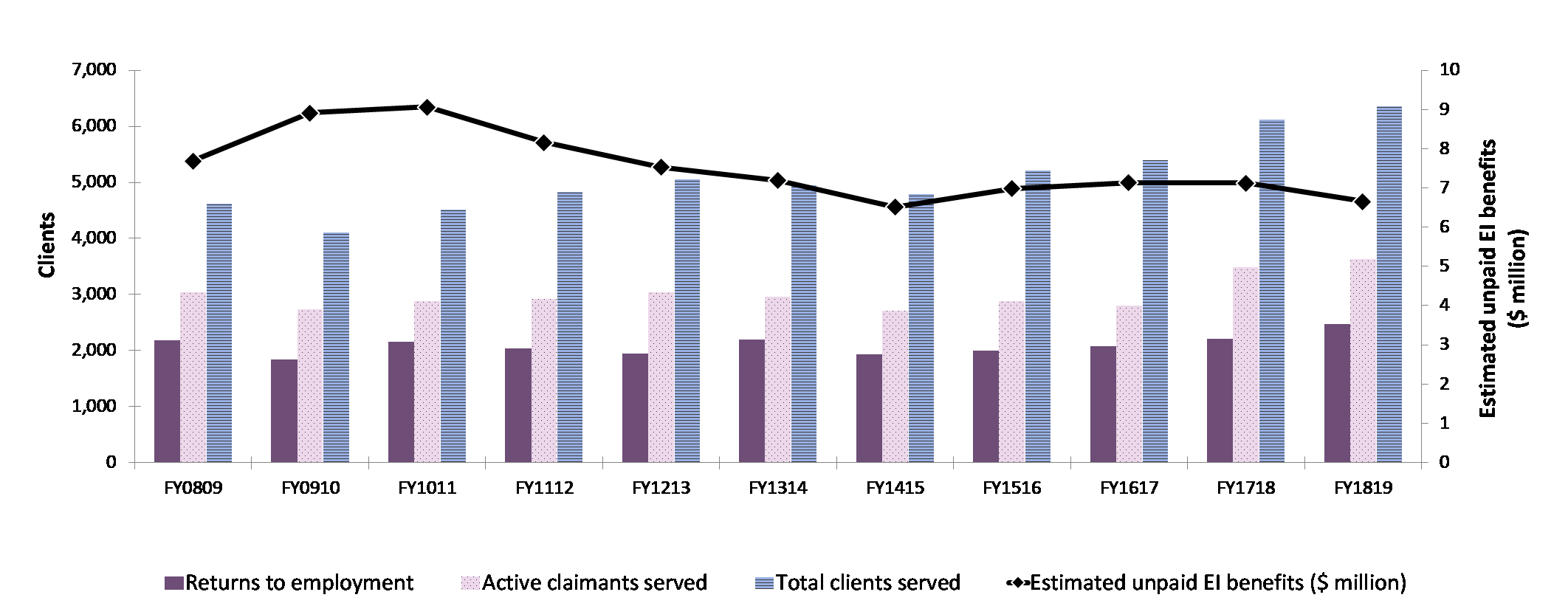

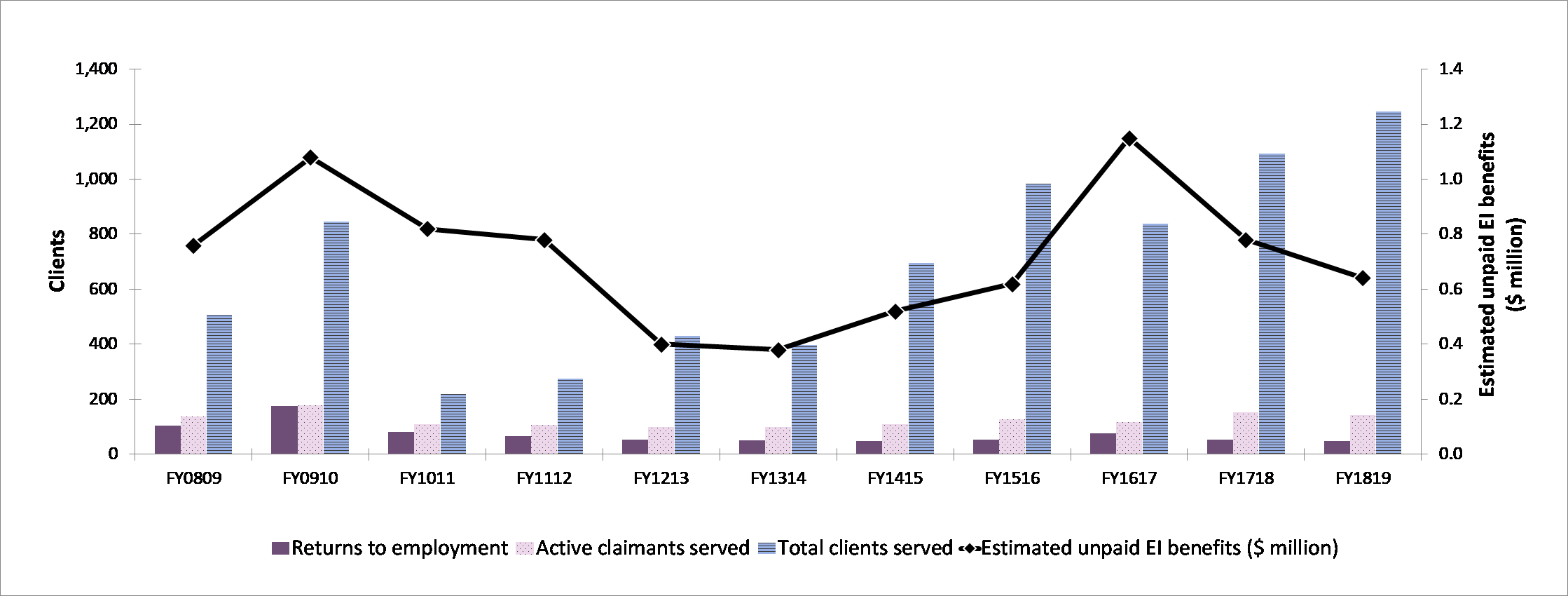

Chart 9 – Text version

| Key performance indicators | FY0809 | FY0910 | FY1011 | FY1112 | FY1213 | FY1314 | FY1415 | FY1516 | FY1617 | FY1718 | FY1819 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Returns to employment | 2,186 | 1,839 | 2,159 | 2,034 | 1,939 | 2,194 | 1,934 | 1,997 | 2,081 | 2,202 | 2,470 |

| Active claimants served | 3,035 | 2,740 | 2,882 | 2,921 | 3,032 | 2,963 | 2,709 | 2,876 | 2,798 | 3,487 | 3,624 |

| Total clients served | 4,619 | 4,112 | 4,525 | 4,835 | 5,056 | 4,951 | 4,800 | 5,214 | 5,400 | 6,123 | 6,369 |

| Estimated unpaid EI benefits ($ million) | $7,69 | $8,92 | $9,07 | $8,16 | $7,53 | $7,19 | $6,52 | $6,99 | $7,14 | $7,13 | $6,66 |

Table 7 - Prince Edward Island: EBSM-similar programming, FY1819

For accessibility reasons, the table has been simplified. Consult the PDF version for the full table.

| Employment benefits | Interventions | Year-over-year Change |

Expenditures ($ 000s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SD-R: Training PEI—Individual | 2,398 | +13.0% | 14,923 |

| SD-A: Training PEI—Apprentice | 305 | +14.2% | |

| TWS: Employ PEI | 562 | -19.3% | 3,696 |

| SE: Self‑Employ PEI | 151 | +3.4% | 1,986 |

| JCP: Work Experience PEI | 59 | -1.7% | 734 |

| Support measures | Interventions | Year-over-year Change |

Expenditures ($ 000s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EAS: Employment Assistance Services | 6,888 | +4.5% | 4,651 |

| LMP: Labour Market Partnerships | n/a | n/a | 1,731 |

| R&I: Research & Innovation | n/a | n/a | 0 |

3.2.3.3 Employment benefits

In FY1819, Prince Edward Island delivered 3,475 Employment Benefit interventions, a 5.6% increase over FY1718. While SD-R (+275; +13.0%), SD-A (+38; +14.2%) and SE (+5; +3.4%) increased, TWS (-134; - 19.3%) and JCP (-1; -1.7%) decreased. The significant rise in SD-R interventions since FY1718 may be attributed to the implementation of the Career Connect Program. This program provides unemployed individuals, who qualified for benefits, an opportunity to continue receiving benefits while attending full-time, post-secondary training within Canada, for the duration of their claim. Expenditures on Employment Benefits increased from $18.8 million to $21.3 million, a 13.7% rise over FY1718.

3.2.3.4 Support measures: EAS

The province delivered 6,888 EAS interventions in FY1819, an increase of 296 (+4.5%) over the previous fiscal year. The number of individual counselling interventions in Prince Edward Island sharply increased (+1,314; +122.6%), while the number of employment services interventions decreased significantly (- 1,018; -18.4%). Expenditures on EAS decreased by $500,000 (-9.2%) to $4.7 million.

Prince Edward Island's Prosper Program

The Prosper Program provides life and employability skills training, as well as ongoing employment coaching and mentoring, to clients who received social assistance and to newcomers to Canada. Targeted clients transitioned to entry-level employment opportunities in high demand sectors, that experience shortage of workers.

The Prosper Program delivered 2 types of training supports for clients to transition into the workforce. Clients could participate in the classroom component, which focused on life and employability skills, followed by job coaching support. For participants who were ready to transition directly to the labour market, a job coach was available to provide coaching and mentoring to assist with the transition to employment.

In the first year of delivery, the program focused on employment opportunities in the agriculture sector. Based on the success of the Prosper Program over the past 3 years of delivery, the program expanded to also support the construction, tourism, and seafood processing sectors.

3.2.3.5 Other support measures: LMP and R&I

Expenditures on LMP ($1.7 million) remained relatively stable in FY1819 compared to FY1718 (+0.6%). There were no reported expenditures under R&I in FY1819.

eForcePEI.ca

The program was designed to meet specific needs of rural learners, small to medium enterprises, non-profit groups, and unemployed or under-employed individuals by providing e-learning courseware to better enhance their employability skills.

The intent of the online learning platform was to provide cost-effective and widely accessible training to businesses and individuals to increase their skills and knowledge. eForcePEI used Bluedrop's online learning platform, CoursePark.com, to provide access to courses from leading publishers and subject experts.

The short courses were mainly delivered using audio over text slides and video. The courses were not interactive and the online format was flexible for employers and employees. Course bundles (groups of related courses) covered a variety of topics. The most popular course bundle since the program started in 2013 was Microsoft Office Excel.

Targeted clientele included small and medium-sized businesses, non-profit organizations, as well as individuals interested in improving their skills and knowledge. The number of individual users and learning networks (each learning network represented a business or organization) grew steadily. As of February 2019, there were 7,000 individual users, and over 700 learning networks.

3.2.4 Nova Scotia

Similar to the situation in 2017, Nova Scotia's real GDP growth remained at 1.5% in 2018. The province's economy is projected to have expanded by about the same rate in 2019. Real GDP growth is projected at 0.8% in 2019 and 0.9% for 2020.

Nova Scotia: EBSM key facts

For accessibility reasons, the table has been simplified. Consult the PDF version for the full table.

| Insured clients | Non-insured clients |

|---|---|

12,408  |

3,040  |

| Intervention type | FY1819 | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 7,136 | 72.5%  |

| Support Measures: EAS | 20,232 | 24.1%  |

| Intervention type | FY1819 | Year-over-year change(pp) |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 26.1% | 12.7  |

| Support Measures: EAS | 73.9% | 12.7  |

| Total expenditures | FY1819 ($ million) |

Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | $48.3 | 5.8%  |

| Support Measures: EAS | $33.4 | 15.3%  |

| LMP and R&I | $5.0 | 113.5%  |

| Total Expenditures2 | $86.7 | 5.0%  |

1 Nova Scotia invested $833,951.50 of its total allocation towards administration costs, representing 9.7% of the Budget 2017 additional funding the Province received in FY1819.

2 Totals may not add up due to rounding; does not include accounting adjustments.

| FY1718 | FY1819 | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| $23.91 | $26.43 | 10.5%  |

In contrast to the modest economic growth, labour market conditions in the province improved markedly in FY1819. The employment growth of 8,500 (+1.9%), entirely realized in full-time positions, was Nova Scotia's highest annual net gain since FY0405. The decline in the number of unemployed (‑5,100; -12.6%) pushed the unemployment rate down to 7.2%, the lowest since Statistics Canada began reporting these estimates in 1976. Employment growth was concentrated in services-producing industries (+7,000; +1.9%), led by gains in accommodation and food services (+4,400; +14.2%), as well as in wholesale and retail trade (+4,000; +5.2%). These were partially offset by declines in health care and social assistance (-1,500; -2.1%), as well as in finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing (‑1,200; ‑5.2%). In the goods-producing sector (+1,500; +1.8%), employment growth was mainly supported by increases in construction (+1,200; +3.6%), and agriculture (+600; +13.3%).

Despite its employment growth, Nova Scotia still faces several labour market challenges moving forward. Shifts that occurred in traditionally dominant industries disproportionally impacted low-skilled workers, while Nova Scotians living outside the Halifax metropolitan area had fewer employment and education opportunities. Many young people had difficulty attaching to the labour market and filling the vacancies created by retirements. In response, the province addressed these challenges by ensuring its more vulnerable residents had the skills needed to successfully keep or gain employment. A skilled workforce will generate productivity gains that will mitigate the losses resulting from a declining workforce. Nova Scotia prioritized groups typically underrepresented in employment such as African Nova Scotians, persons with disabilities, visible minorities, persons in gender-non-traditional careers, and new immigrants to Canada.

3.2.4.1 Managing for results

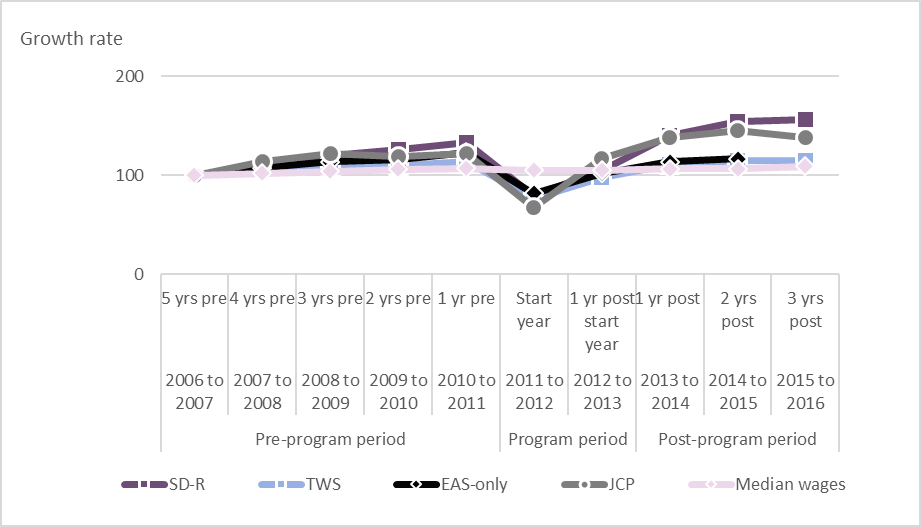

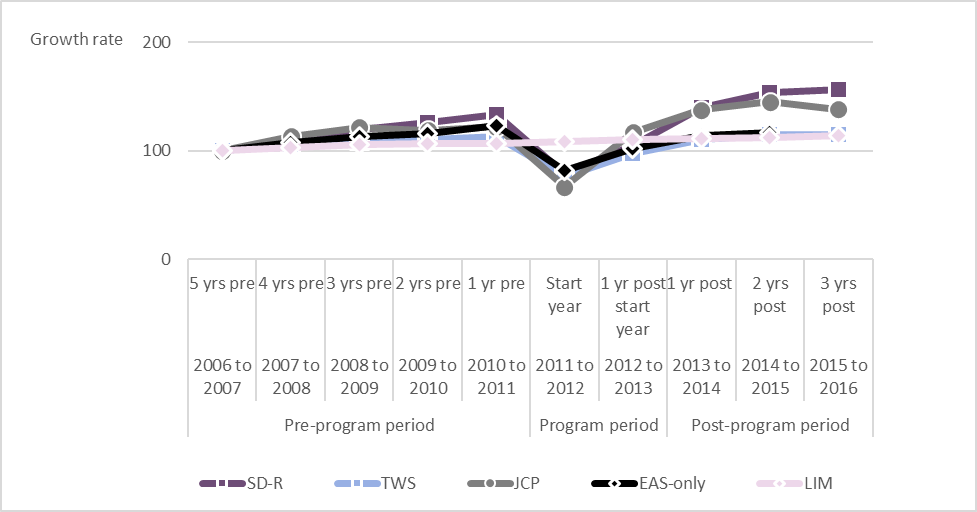

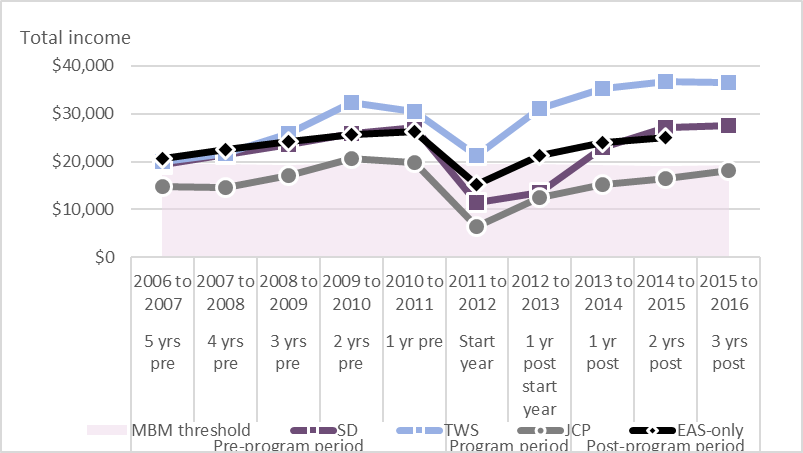

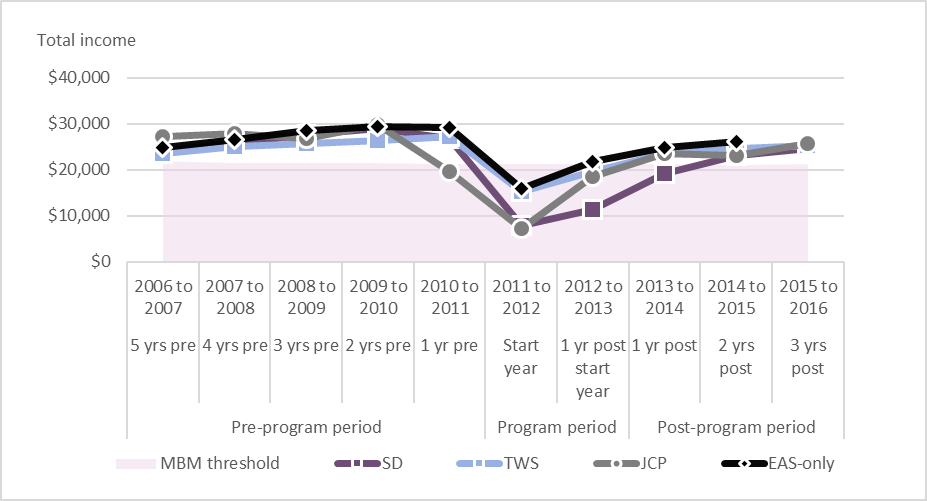

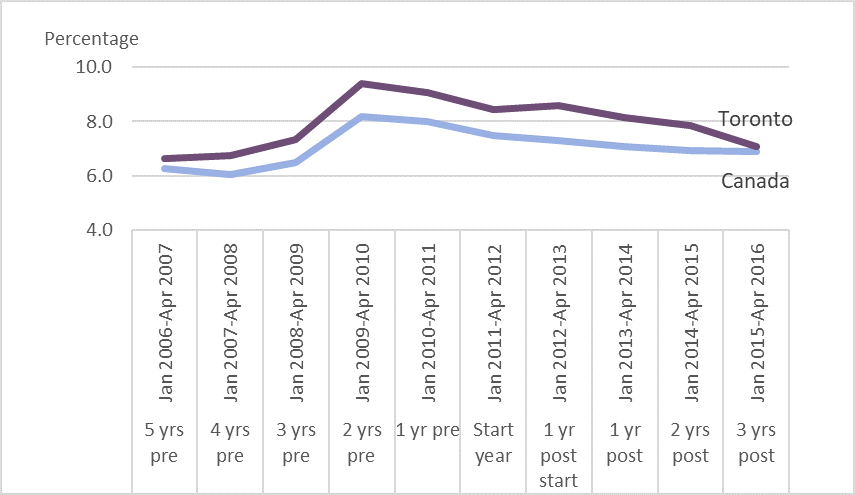

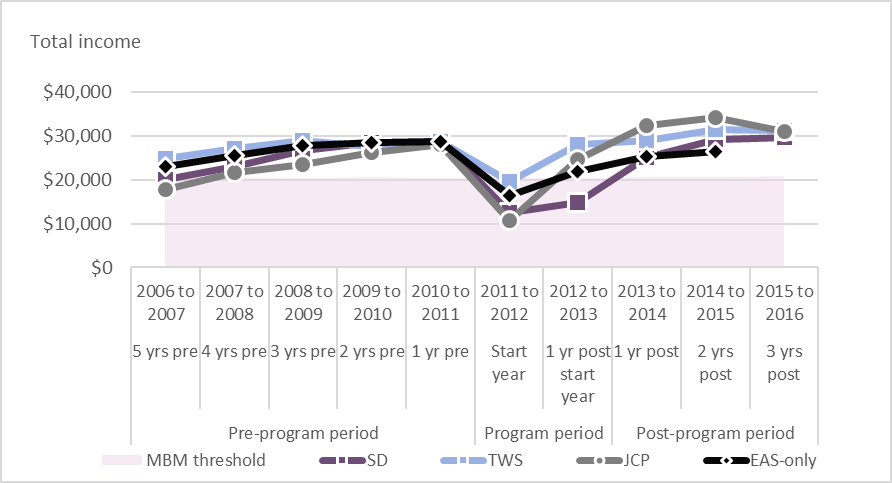

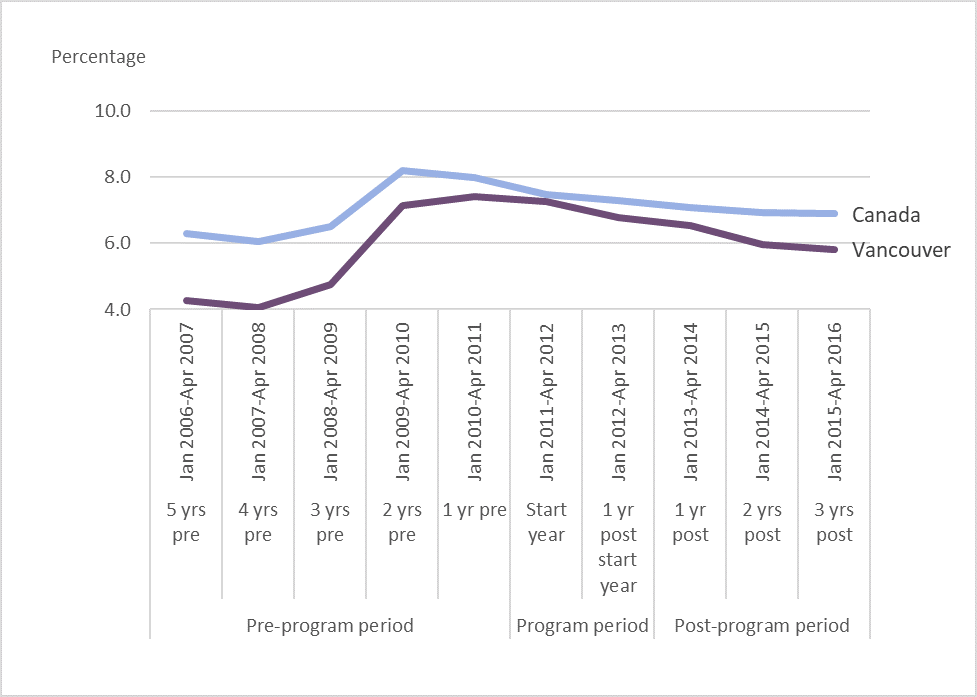

Targeting, Referral and Feedback System