Chapter 1: Labour Market Context

From: Employment and Social Development Canada

Official title: Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2020 and ending March 31, 2021: Chapter 1: Labour market context

In chapter 1

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1.1 Economic overview

- 1.2 The Canadian labour market

- 1.3 Job vacancies

- 1.4 Summary

List of abbreviations

This is the complete list of abbreviations for the Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2020 and ending March 31, 2021.

Abbreviations

- AD

- Appeal Division

- ADR

- Alternative Dispute Resolution

- ASETS

- Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy

- B/C Ratio

- Benefits-to-Contributions ratio

- BDM

- Benefits Delivery Modernization

- CAWS

- Client Access Workstation Services

- CCDA

- Canadian Council of Directors of Apprenticeship

- CCIS

- Corporate Client Information Service

- CEIC

- Canada Employment Insurance Commission

- CERB

- Canada Emergency Response Benefit

- CESB

- Canada Emergency Student Benefit

- CEWB

- Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy

- COLS

- Community Outreach and Liaison Service

- CPP

- Canada Pension Plan

- CRA

- Canada Revenue Agency

- CRB

- Canada Recovery Benefit

- CRCB

- Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit

- CRF

- Consolidated Revenue Fund

- CRSB

- Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit

- CSO

- Citizen Service Officer

- CX

- Client Experience

- EBSM

- Employment Benefits and Support Measures

- ECC

- Employer Contact Centre

- EI

- Employment Insurance

- EI ERB

- Employment Insurance Emergency Response Benefit

- EICS

- Employment Insurance Coverage Survey

- eROE

- Electronic Record of Employment

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- eSIN

- Electronic Social Insurance Number

- FY

- Fiscal Year

- G7

- Group of Seven

- GDP

- Gross Domestic Product

- GIS

- Guaranteed Income Supplements

- HCCS

- Hosted Contact Centre Solution

- IQF

- Individual Quality Feedback

- ISET

- Indigenous Skills and Employment Training

- IVR

- Interactive Voice Response

- LFS

- Labour Force Survey

- LMDA

- Labour Market Development Agreements

- LMI

- Labour Market Information

- LMP

- Labour Market Partnerships

- MIE

- Maximum Insurable Earnings

- MSCA

- My Service Canada Account

- NAICS

- North American Industry Classification System

- NESI

- National Essential Skills Initiative

- NIS

- National Investigative Services

- NOM

- National Operating Model

- OAS

- Old Age Security

- PAAR

- Payment Accuracy Review

- PPE

- Premium-paid eligible individuals

- PRAR

- Processing Accuracy Review

- PRP

- Premium Reduction Program

- PTs

- Provinces and Territories

- QPIP

- Quebec Parental Insurance Plan

- R&I

- Research and Innovation

- ROE

- Record of Employment

- RPA

- Robotics Process Automation

- SAT

- Secure Automated Transfer

- SCC

- Service Canada Centre

- SDP

- Service Delivery Partner

- SEPH

- Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours

- SIN

- Social Insurance Number

- SIR

- Social Insurance Registry

- SST

- Social Security Tribunal

- STDP

- Short-term disability plan

- SUB

- Supplemental Unemployment Benefit

- TRF

- Targeting, Referral and Feedback

- TTY

- Teletypewriter

- UV

- Unemployment-to-vacancy

- VBW

- Variable Best Weeks

- VER

- Variable Entrance Requirement

- VRI

- Video Remote Interpretation

- WCAG

- Web Content Accessibility Guidelines

- WWC

- Working While on Claim

Introduction

This chapter outlines the overall economic situation and key labour market developments in Canada during the fiscal year beginning on April 1, 2020 and ending on March 31, 2021 (FY2021).Footnote 1 This is the same period for which this Report assesses the Employment Insurance (EI) program. The chapter starts with a short timeline of the COVID-19 pandemic, including the public health measures and the emergency programs that were put in place. Section 1.1 provides a general overview and context of the economic situation for FY2021. Section 1.2 summarizes key labour market developments in the Canadian economy during the reporting period.Footnote 2 Section 1.3 concentrates on the evolution of the job vacancies during the last two quarters of FY2021.Footnote 3 Definitions and more detailed statistical tables related to key labour market concepts discussed in this chapter can be found in annex 1.

COVID-19 and public health measures timeline

On March 11th 2020, the World Health Organization announced that COVID-19 could be characterized as a pandemic. In the following days, the federal and provincial governments imposed different public health measures to reduce the spread of COVID-19, forcing non-essential businesses to close. International travelling restrictions were put in place and the Canada/United States border was closed for all non-essential travel. This led to a massive and an unprecedented output decline and employment losses during the first 2 months of the pandemic, in March and April 2020.

In response to those exceptional events, the Government of Canada provided support to Canadians and businesses facing hardship. Among others, measures such as the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), the Canada Emergency Student Benefit (CESB) and the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS) were implemented.

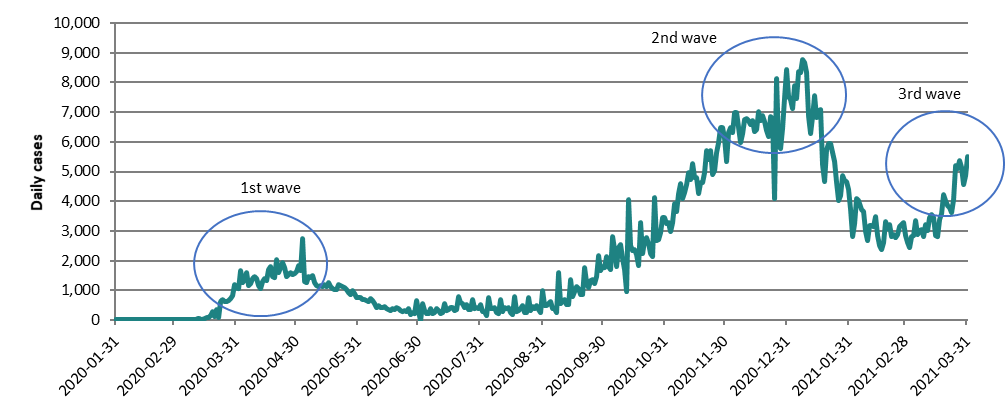

As the number of COVID-19 cases started to decline in early May 2020 (consult chart 1), several provincial governments announced partial and progressive reopening of some non-essential services. By mid-July 2020 all provinces had allowed reopening of a significant proportion of business that had been closed in March and April.

Following the emergence of a second wave of COVID-19 cases in late September, many provinces began introducing targeted public health measures. In early November, additional restrictions were imposed, including the closure of many recreational and cultural facilities, in-person dining services, as well as various degrees of restrictions on retail businesses.

In the meantime, temporary changes were made to the EI program to broaden its access, permitting previously ineligible contributors to get full access to the benefits. CERB and CESB ended in September 2020 and were replaced by a set of new programs, the Canada Recovery Benefit (CRB), the Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit (CRSB) and the Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit (CRCB) for those who were not eligible to receive EI benefitsFootnote 4.

In early February 2021, public health restrictions were eased in many provinces. This allowed for the re-opening of many non-essential businesses, cultural and recreational facilities, and some in-person dining. However, capacity limits and other public health requirements, which varied across jurisdictions, remained in place.

By the end of FY2021, a third wave of COVID-19 emerged. In response, public health measures were tightened again in several provinces in late March and early April.

This succession of closures and reopening of non-essential services led to important fluctuations in employment, hours worked and unemployment during the whole fiscal year.

Text description of Chart 1

| Date | Daily cases |

|---|---|

| 2020-01-31 | 4 |

| 2020-02-08 | 3 |

| 2020-02-16 | 1 |

| 2020-02-21 | 1 |

| 2020-02-24 | 1 |

| 2020-02-25 | 1 |

| 2020-02-26 | 1 |

| 2020-02-27 | 1 |

| 2020-02-29 | 2 |

| 2020-03-01 | 9 |

| 2020-03-03 | 9 |

| 2020-03-05 | 12 |

| 2020-03-06 | 6 |

| 2020-03-07 | 6 |

| 2020-03-08 | 5 |

| 2020-03-09 | 15 |

| 2020-03-11 | 26 |

| 2020-03-12 | 38 |

| 2020-03-13 | 38 |

| 2020-03-14 | 20 |

| 2020-03-15 | 54 |

| 2020-03-16 | 88 |

| 2020-03-17 | 99 |

| 2020-03-18 | 157 |

| 2020-03-19 | 276 |

| 2020-03-20 | 131 |

| 2020-03-21 | 367 |

| 2020-03-22 | 100 |

| 2020-03-23 | 620 |

| 2020-03-24 | 701 |

| 2020-03-25 | 617 |

| 2020-03-26 | 634 |

| 2020-03-27 | 646 |

| 2020-03-28 | 736 |

| 2020-03-29 | 833 |

| 2020-03-30 | 1,179 |

| 2020-03-31 | 1,111 |

| 2020-04-01 | 1,065 |

| 2020-04-02 | 1,670 |

| 2020-04-03 | 1,254 |

| 2020-04-04 | 1,367 |

| 2020-04-05 | 1,608 |

| 2020-04-06 | 1,155 |

| 2020-04-07 | 1,230 |

| 2020-04-08 | 1,392 |

| 2020-04-09 | 1,476 |

| 2020-04-10 | 1,383 |

| 2020-04-11 | 1,169 |

| 2020-04-12 | 1,066 |

| 2020-04-13 | 1,297 |

| 2020-04-14 | 1,383 |

| 2020-04-15 | 1,318 |

| 2020-04-16 | 1,711 |

| 2020-04-17 | 1,792 |

| 2020-04-18 | 1,469 |

| 2020-04-19 | 1,432 |

| 2020-04-20 | 2,045 |

| 2020-04-21 | 1,591 |

| 2020-04-22 | 1,769 |

| 2020-04-23 | 1,920 |

| 2020-04-24 | 1,778 |

| 2020-04-25 | 1,466 |

| 2020-04-26 | 1,541 |

| 2020-04-27 | 1,605 |

| 2020-04-28 | 1,526 |

| 2020-04-29 | 1,571 |

| 2020-04-30 | 1,639 |

| 2020-05-01 | 1,825 |

| 2020-05-02 | 1,653 |

| 2020-05-03 | 2,760 |

| 2020-05-04 | 1,298 |

| 2020-05-05 | 1,274 |

| 2020-05-06 | 1,449 |

| 2020-05-07 | 1,426 |

| 2020-05-08 | 1,512 |

| 2020-05-09 | 1,268 |

| 2020-05-10 | 1,146 |

| 2020-05-11 | 1,133 |

| 2020-05-12 | 1,175 |

| 2020-05-13 | 1,121 |

| 2020-05-14 | 1,211 |

| 2020-05-15 | 1,126 |

| 2020-05-16 | 1,251 |

| 2020-05-17 | 1,138 |

| 2020-05-18 | 1,070 |

| 2020-05-19 | 1,040 |

| 2020-05-20 | 1,011 |

| 2020-05-21 | 1,201 |

| 2020-05-22 | 1,156 |

| 2020-05-23 | 1,141 |

| 2020-05-24 | 1,078 |

| 2020-05-25 | 1,012 |

| 2020-05-26 | 936 |

| 2020-05-27 | 872 |

| 2020-05-28 | 993 |

| 2020-05-29 | 906 |

| 2020-05-30 | 772 |

| 2020-05-31 | 757 |

| 2020-06-01 | 758 |

| 2020-06-02 | 705 |

| 2020-06-03 | 675 |

| 2020-06-04 | 641 |

| 2020-06-05 | 609 |

| 2020-06-06 | 722 |

| 2020-06-07 | 642 |

| 2020-06-08 | 545 |

| 2020-06-09 | 409 |

| 2020-06-10 | 472 |

| 2020-06-11 | 405 |

| 2020-06-12 | 413 |

| 2020-06-13 | 467 |

| 2020-06-14 | 377 |

| 2020-06-15 | 360 |

| 2020-06-16 | 320 |

| 2020-06-17 | 386 |

| 2020-06-18 | 367 |

| 2020-06-19 | 409 |

| 2020-06-20 | 390 |

| 2020-06-21 | 318 |

| 2020-06-22 | 300 |

| 2020-06-23 | 326 |

| 2020-06-24 | 279 |

| 2020-06-25 | 380 |

| 2020-06-26 | 172 |

| 2020-06-27 | 238 |

| 2020-06-28 | 218 |

| 2020-06-29 | 668 |

| 2020-06-30 | 286 |

| 2020-07-01 | n/a |

| 2020-07-02 | 567 |

| 2020-07-03 | 319 |

| 2020-07-04 | 226 |

| 2020-07-05 | 219 |

| 2020-07-06 | 399 |

| 2020-07-07 | 232 |

| 2020-07-08 | 267 |

| 2020-07-09 | 371 |

| 2020-07-10 | 321 |

| 2020-07-11 | 221 |

| 2020-07-12 | 244 |

| 2020-07-13 | 565 |

| 2020-07-14 | 331 |

| 2020-07-15 | 341 |

| 2020-07-16 | 437 |

| 2020-07-17 | 405 |

| 2020-07-18 | 330 |

| 2020-07-19 | 339 |

| 2020-07-20 | 786 |

| 2020-07-21 | 573 |

| 2020-07-22 | 543 |

| 2020-07-23 | 432 |

| 2020-07-24 | 534 |

| 2020-07-25 | 350 |

| 2020-07-26 | 355 |

| 2020-07-27 | 686 |

| 2020-07-28 | 397 |

| 2020-07-29 | 412 |

| 2020-07-30 | 393 |

| 2020-07-31 | 513 |

| 2020-08-01 | 287 |

| 2020-08-02 | 285 |

| 2020-08-03 | 147 |

| 2020-08-04 | 761 |

| 2020-08-05 | 395 |

| 2020-08-06 | 374 |

| 2020-08-07 | 424 |

| 2020-08-08 | 236 |

| 2020-08-09 | 230 |

| 2020-08-10 | 681 |

| 2020-08-11 | 289 |

| 2020-08-12 | 423 |

| 2020-08-13 | 390 |

| 2020-08-14 | 418 |

| 2020-08-15 | 237 |

| 2020-08-16 | 198 |

| 2020-08-17 | 785 |

| 2020-08-18 | 282 |

| 2020-08-19 | 336 |

| 2020-08-20 | 383 |

| 2020-08-21 | 499 |

| 2020-08-22 | 257 |

| 2020-08-23 | 267 |

| 2020-08-24 | 750 |

| 2020-08-25 | 323 |

| 2020-08-26 | 448 |

| 2020-08-27 | 401 |

| 2020-08-28 | 492 |

| 2020-08-29 | 363 |

| 2020-08-30 | 267 |

| 2020-08-31 | 1,008 |

| 2020-09-01 | 477 |

| 2020-09-02 | 498 |

| 2020-09-03 | 570 |

| 2020-09-04 | 631 |

| 2020-09-05 | 371 |

| 2020-09-06 | 400 |

| 2020-09-07 | 247 |

| 2020-09-08 | 1,606 |

| 2020-09-09 | 546 |

| 2020-09-10 | 630 |

| 2020-09-11 | 702 |

| 2020-09-12 | 515 |

| 2020-09-13 | 518 |

| 2020-09-14 | 1,351 |

| 2020-09-15 | 793 |

| 2020-09-16 | 944 |

| 2020-09-17 | 1,120 |

| 2020-09-18 | 1,044 |

| 2020-09-19 | 863 |

| 2020-09-20 | 875 |

| 2020-09-21 | 1,766 |

| 2020-09-22 | 1,248 |

| 2020-09-23 | 1,090 |

| 2020-09-24 | 1,341 |

| 2020-09-25 | 1,362 |

| 2020-09-26 | 1,215 |

| 2020-09-27 | 1,454 |

| 2020-09-28 | 2,176 |

| 2020-09-29 | 1,660 |

| 2020-09-30 | 1,797 |

| 2020-10-01 | 1,777 |

| 2020-10-02 | 2,124 |

| 2020-10-03 | 1,812 |

| 2020-10-04 | 1,685 |

| 2020-10-05 | 2,804 |

| 2020-10-06 | 2,363 |

| 2020-10-07 | 1,800 |

| 2020-10-08 | 2,436 |

| 2020-10-09 | 2,558 |

| 2020-10-10 | 2,062 |

| 2020-10-11 | 1,685 |

| 2020-10-12 | 975 |

| 2020-10-13 | 4,042 |

| 2020-10-14 | 2,506 |

| 2020-10-15 | 2,345 |

| 2020-10-16 | 2,374 |

| 2020-10-17 | 2,215 |

| 2020-10-18 | 1,827 |

| 2020-10-19 | 3,289 |

| 2020-10-20 | 2,251 |

| 2020-10-21 | 2,672 |

| 2020-10-22 | 2,788 |

| 2020-10-23 | 2,584 |

| 2020-10-24 | 2,227 |

| 2020-10-25 | 2,145 |

| 2020-10-26 | 4,109 |

| 2020-10-27 | 2,674 |

| 2020-10-28 | 2,699 |

| 2020-10-29 | 2,956 |

| 2020-10-30 | 3,457 |

| 2020-10-31 | 3,445 |

| 2020-11-01 | 3,244 |

| 2020-11-02 | 3,273 |

| 2020-11-03 | 2,974 |

| 2020-11-04 | 3,283 |

| 2020-11-05 | 3,922 |

| 2020-11-06 | 3,669 |

| 2020-11-07 | 4,246 |

| 2020-11-08 | 4,594 |

| 2020-11-09 | 4,086 |

| 2020-11-10 | 4,302 |

| 2020-11-11 | 4,559 |

| 2020-11-12 | 4,981 |

| 2020-11-13 | 4,741 |

| 2020-11-14 | 5,267 |

| 2020-11-15 | 4,805 |

| 2020-11-16 | 4,802 |

| 2020-11-17 | 4,276 |

| 2020-11-18 | 4,641 |

| 2020-11-19 | 4,642 |

| 2020-11-20 | 4,968 |

| 2020-11-21 | 5,705 |

| 2020-11-22 | 5,418 |

| 2020-11-23 | 5,713 |

| 2020-11-24 | 4,889 |

| 2020-11-25 | 5,022 |

| 2020-11-26 | 5,631 |

| 2020-11-27 | 5,967 |

| 2020-11-28 | 6,496 |

| 2020-11-29 | 6,476 |

| 2020-11-30 | 6,103 |

| 2020-12-01 | 5,329 |

| 2020-12-02 | 6,307 |

| 2020-12-03 | 6,493 |

| 2020-12-04 | 6,300 |

| 2020-12-05 | 6,999 |

| 2020-12-06 | 6,987 |

| 2020-12-07 | 6,499 |

| 2020-12-08 | 5,981 |

| 2020-12-09 | 6,295 |

| 2020-12-10 | 6,739 |

| 2020-12-11 | 6,771 |

| 2020-12-12 | 6,710 |

| 2020-12-13 | 6,580 |

| 2020-12-14 | 6,731 |

| 2020-12-15 | 6,352 |

| 2020-12-16 | 6,416 |

| 2020-12-17 | 7,008 |

| 2020-12-18 | 6,707 |

| 2020-12-19 | 6,895 |

| 2020-12-20 | 6,693 |

| 2020-12-21 | 6,381 |

| 2020-12-22 | 6,196 |

| 2020-12-23 | 6,845 |

| 2020-12-24 | 6,796 |

| 2020-12-25 | 4,092 |

| 2020-12-26 | 8,129 |

| 2020-12-27 | 5,903 |

| 2020-12-28 | 5,790 |

| 2020-12-29 | 6,441 |

| 2020-12-30 | 7,477 |

| 2020-12-31 | 8,446 |

| 2021-01-01 | 7,512 |

| 2021-01-02 | 7,437 |

| 2021-01-03 | 7,137 |

| 2021-01-04 | 7,911 |

| 2021-01-05 | 7,447 |

| 2021-01-06 | 8,372 |

| 2021-01-07 | 8,340 |

| 2021-01-08 | 8,766 |

| 2021-01-09 | 8,665 |

| 2021-01-10 | 8,320 |

| 2021-01-11 | 6,849 |

| 2021-01-12 | 6,287 |

| 2021-01-13 | 6,860 |

| 2021-01-14 | 7,565 |

| 2021-01-15 | 6,809 |

| 2021-01-16 | 7,063 |

| 2021-01-17 | 7,080 |

| 2021-01-18 | 5,225 |

| 2021-01-19 | 4,679 |

| 2021-01-20 | 5,744 |

| 2021-01-21 | 5,955 |

| 2021-01-22 | 5,957 |

| 2021-01-23 | 5,651 |

| 2021-01-24 | 5,323 |

| 2021-01-25 | 4,630 |

| 2021-01-26 | 4,011 |

| 2021-01-27 | 4,204 |

| 2021-01-28 | 4,877 |

| 2021-01-29 | 4,690 |

| 2021-01-30 | 4,663 |

| 2021-01-31 | 4,397 |

| 2021-02-01 | 3,736 |

| 2021-02-02 | 2,828 |

| 2021-02-03 | 3,234 |

| 2021-02-04 | 4,083 |

| 2021-02-05 | 4,022 |

| 2021-02-06 | 3,729 |

| 2021-02-07 | 3,668 |

| 2021-02-08 | 2,967 |

| 2021-02-09 | 2,677 |

| 2021-02-10 | 3,185 |

| 2021-02-11 | 3,181 |

| 2021-02-12 | 3,143 |

| 2021-02-13 | 3,499 |

| 2021-02-14 | 2,862 |

| 2021-02-15 | 2,522 |

| 2021-02-16 | 2,387 |

| 2021-02-17 | 2,605 |

| 2021-02-18 | 3,314 |

| 2021-02-19 | 3,091 |

| 2021-02-20 | 3,219 |

| 2021-02-21 | 2,825 |

| 2021-02-22 | 2,878 |

| 2021-02-23 | 2,790 |

| 2021-02-24 | 2,896 |

| 2021-02-25 | 3,134 |

| 2021-02-26 | 3,219 |

| 2021-02-27 | 3,295 |

| 2021-02-28 | 2,852 |

| 2021-03-01 | 2,596 |

| 2021-03-02 | 2,457 |

| 2021-03-03 | 2,812 |

| 2021-03-04 | 2,832 |

| 2021-03-05 | 3,363 |

| 2021-03-06 | 2,876 |

| 2021-03-07 | 3,025 |

| 2021-03-08 | 3,037 |

| 2021-03-09 | 2,820 |

| 2021-03-10 | 3,223 |

| 2021-03-11 | 3,022 |

| 2021-03-12 | 3,459 |

| 2021-03-13 | 3,539 |

| 2021-03-14 | 3,445 |

| 2021-03-15 | 2,846 |

| 2021-03-16 | 2,819 |

| 2021-03-17 | 3,384 |

| 2021-03-18 | 3,599 |

| 2021-03-19 | 4,214 |

| 2021-03-20 | 4,010 |

| 2021-03-21 | 3,866 |

| 2021-03-22 | 3,775 |

| 2021-03-23 | 3,606 |

| 2021-03-24 | 4,041 |

| 2021-03-25 | 5,200 |

| 2021-03-26 | 5,095 |

| 2021-03-27 | 5,364 |

| 2021-03-28 | 5,126 |

| 2021-03-29 | 4,574 |

| 2021-03-30 | 4,878 |

| 2021-03-31 | 5,513 |

- Source: Public Health Agency of Canada.

1.1 Economic overview

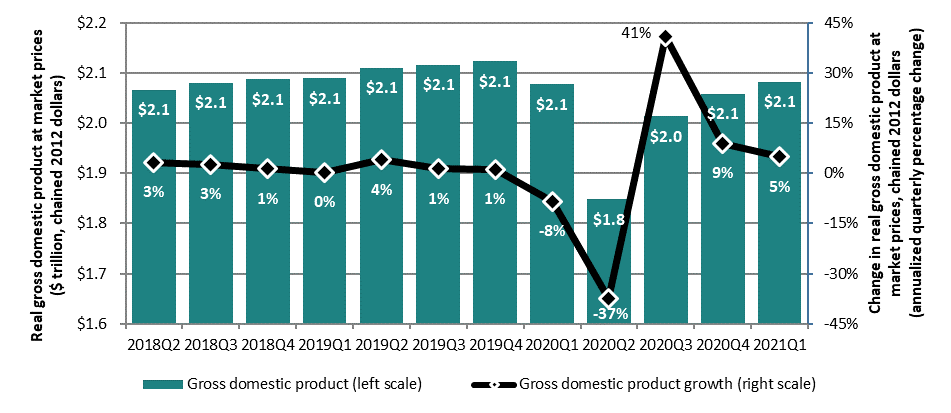

As a result of the public health measures put in place in early 2020, the Canadian economy experienced its steepest decline since quarterly data were first recorded in 1960. In the first quarter of FY2021, real gross domestic product (GDP) fell at an annualized rate of 37.4% (consult chart 2). Sharp decreases in household spending, business investment, and international trade were recorded due to widespread shutdowns of non-essential businesses, border closures, and restrictions on travel and tourism.

With the progressive reopening of non-essentials services and the relaxation of public health measures, the Canadian economy rebounded in the second quarter of FY2021. The economy grew by 41.1%, led by substantial upturns in housing investment, household spending on durable goods, and exports.

Starting in late September, ongoing fluctuations in the number of COVID-19 cases in following months led to a succession of closures and reopenings. Despite this, the Canadian economy remained resilient in the last two quarters of FY2021, recording solid economic growth. Despite this rebound, by the end of FY2021, the Canadian economy still remained 1.9% below its pre-pandemic peak recorded in the third quarter of the previous fiscal year (FY1920).

Text description of Chart 2

| Quarter | Gross domestic product (left scale) | Gross domestic product growth (right scale) |

|---|---|---|

| 2018Q2 | $2.1 | 3% |

| 2018Q3 | $2.1 | 3% |

| 2018Q4 | $2.1 | 1% |

| 2019Q1 | $2.1 | 0% |

| 2019Q2 | $2.1 | 4% |

| 2019Q3 | $2.1 | 1% |

| 2019Q4 | $2.1 | 1% |

| 2020Q1 | $2.1 | -8% |

| 2020Q2 | $1.8 | -37% |

| 2020Q3 | $2.0 | 41% |

| 2020Q4 | $2.1 | 9% |

| 2021Q1 | $2.1 | 5% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0104-01.

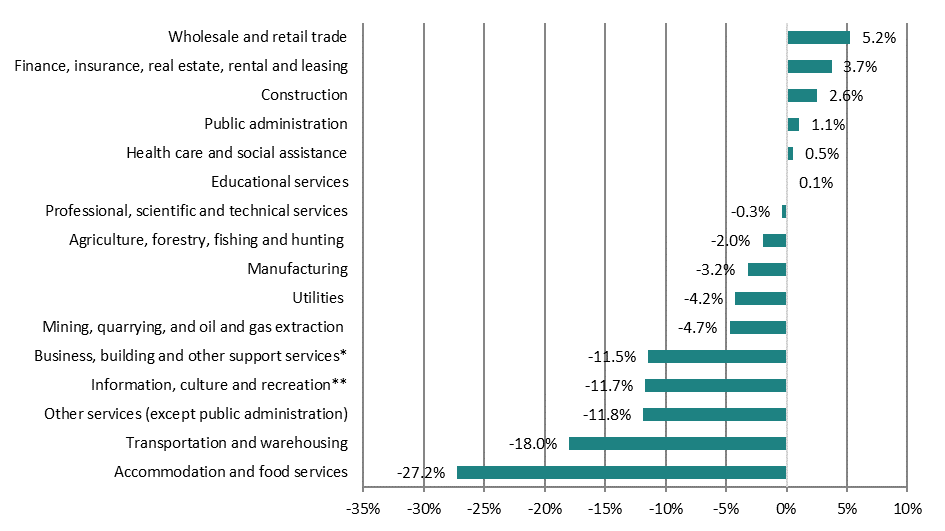

All industries were affected by the COVID-19 restrictions imposed in March and April 2020. However, some industries experienced greater challenges than others. With mandatory closures of all non-essential businesses, industries where social distancing was difficult to implement or teleworkingFootnote 5 was not an option, recorded unprecedented drops in output. For instance, the accommodation and food services industry recorded a cumulative decline of more than 60% in output during those 2 months alone. The transportation sector was also severely impacted by international traveling restrictions. On the other hand, sectors where teleworking was generally possibleFootnote 6, such as finance and insurance; as well as professional, scientific and technical services, recorded only relative modest declines.

The progressive reopening of non-essential services and the relaxation of public health measures starting in mid-2020 led to a generalized, but still uneven recovery of the economy. The burden of subsequent closures and reopenings accompanying the second and third wave of COVID-19 remained on the same sectors such as accommodation and food services; information, culture and recreation; and retail trade; while other sectors recorded uninterrupted output growth.

In March of 2021, 6 of the 16 main industries had fully recovered output losses during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, for the other remaining 10 industries, output was still lagging compared to their pre-pandemic levels, with accommodation and food services remaining the most impacted sector, having a GDP that was still 27.2% below its pre-pandemic level, followed by transportation and warehousing (-18.0%, consult chart 3).

Text description of Chart 3

| Industry | Change in real GDP |

|---|---|

| Wholesale and retail trade | 5.2% |

| Finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing | 3.7% |

| Construction | 2.6% |

| Public administration | 1.1% |

| Health care and social assistance | 0.5% |

| Educational services | 0.1% |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | -0.3% |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | -2.0% |

| Manufacturing | -3.2% |

| Utilities | -4.2% |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction | -4.7% |

| Business, building and other support services* | -11.5% |

| Information, culture and recreation** | -11.7% |

| Other services (except public administration) | -11.8% |

| Transportation and warehousing | -18.0% |

| Accommodation and food services | -27.2% |

- * Includes management of companies and enterprises and administrative and support, waste management and remediation services.

- ** Includes information and cultural industries and arts, entertainment and recreation industries.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0434-01.

As for international comparison, all G7 countries—a group consisting of the world’s major industrialized and advanced countries including CanadaFootnote 7—experienced significant economic activity declines in the second quarter of 2020. While they all saw a rebound in the following quarter, the recovery was uneven across the G7. The recovery across these countries reflected the timing and relative importance of COVID-19 cases fluctuations and the severity of the public health measures put in place.Footnote 8

1.2 The Canadian labour market

This section highlights key labour market developments in Canada during the reporting period, including some that are linked to the EI program.Footnote 9

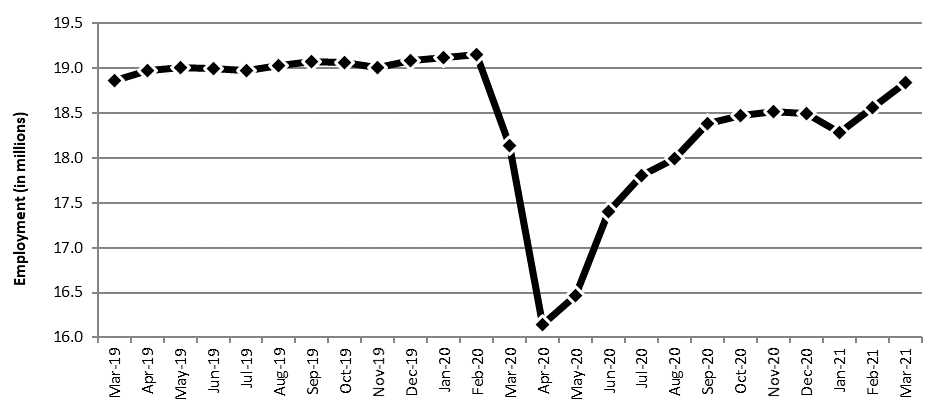

The decline in economic activity described in the previous section was accompanied by massive employment losses. At its peak in April 2020, employment declined by 3.0 million (-15.7%) compared with February 2020 (consult chart 4). In addition, the number of workers still employed, but working less than half their usual hours increased by 2.5 million (+308.2%). This increase mostly reflected a surge of those that worked zero hours (2.2 million or +391.6%, consult chart 5).

Text description of Chart 4

| Month | Total employment (in millions) |

|---|---|

| Mar-19 | 18.8617 |

| Apr-19 | 18.9712 |

| May-19 | 19.0043 |

| Jun-19 | 18.9957 |

| Jul-19 | 18.9659 |

| Aug-19 | 19.0255 |

| Sep-19 | 19.0731 |

| Oct-19 | 19.0634 |

| Nov-19 | 19 |

| Dec-19 | 19.0824 |

| Jan-20 | 19.1165 |

| Feb-20 | 19.1436 |

| Mar-20 | 18.1314 |

| Apr-20 | 16.1458 |

| May-20 | 16.4672 |

| Jun-20 | 17.3977 |

| Jul-20 | 17.8018 |

| Aug-20 | 17.9937 |

| Sep-20 | 18.3777 |

| Oct-20 | 18.4677 |

| Nov-20 | 18.5163 |

| Dec-20 | 18.4934 |

| Jan-21 | 18.2856 |

| Feb-21 | 18.5581 |

| Mar-21 | 18.8344 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. Table 14-10-0287-01.

As of March 2021, about 547,600 Canadians were still impacted by the pandemic, including an additional 309,200 unemployed (-1.6%). In addition, another 238,400 were still employed but working less than half their usual hours relative to February 2020 (+29.4%).

Text description of Chart 5

| Month | Employment losses (millions) | Zero hours (millions) | Less than 50% (millions) | Total impacted (millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feb-20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mar-20 | -1.0122 | -1.5001 | -0.6919 | -3.2042 |

| Apr-20 | -2.9978 | -2.2274 | -0.2684 | -5.4936 |

| May-20 | -2.6764 | -1.8314 | -0.3511 | -4.8589 |

| Jun-20 | -1.7459 | -1.073 | -0.2678 | -3.0867 |

| Jul-20 | -1.3418 | -0.7704 | -0.1812 | -2.2934 |

| Aug-20 | -1.1499 | -0.6246 | -0.0896 | -1.8641 |

| Sep-20 | -0.7659 | -0.4425 | -0.1482 | -1.3566 |

| Oct-20 | -0.6759 | -0.3887 | -0.0451 | -1.1097 |

| Nov-20 | -0.6273 | -0.382 | -0.0462 | -1.0555 |

| Dec-20 | -0.6502 | -0.4136 | -0.059 | -1.1228 |

| Jan-21 | -0.858 | -0.4687 | -0.0472 | -1.3739 |

| Feb-21 | -0.5855 | -0.3436 | -0.0567 | -0.9858 |

| Mar-21 | -0.3092 | -0.2266 | -0.0118 | -0.5476 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Supplement Table.

Labour force growth and the labour force participation rate

As millions of Canadians lost their job, a significant proportion of them dropped out of the labour force. Given the high level of uncertainty, many individuals were not actively looking for work, leading to a significant decline in the labour force.Footnote 10 Indeed, in April 2020, there were 1.7 million fewer Canadians in the labour force compared to February 2020. Of those, 1.15 million wanted to work but did not look for a job.

With the reopening of the economy, by June 2020 the size of the labour force was only 2.4% below its February 2020 level. As restrictions continued to loosen across the country, the gradual recovery continued through the rest of the summer and into the fall. As a result, more individuals either returned to their jobs or look for (and eventually find) new jobs. By October 2020, the size of the Canadian labour force was 0.1% above its February level. However, new public measures put in place during the second wave of COVID-19 halted the recovery of the labour market. This lead to a second, but less pronounced, decline in the size of the labour force, reaching its lowest point in January 2021. Yet, as the second waved eased, restrictions started being lifted and by March 2021, the labour force had rebounded, standing 0.3% above its pre-pandemic level.

Led by the large decrease in the labour force, the participation rate fell from 65.6% in February to 59.9% in April 2020. The participation rate remained slightly lower in March 2021 (65.2%) than it was in February 2020 (65.6%), despite the size of the labour force being slightly above its pre-pandemic level. This is explained by the fact that the size of the population aged 15 and over grew at a faster rate then the labour force.

Employment growth

As mentioned earlier, public health measures led to significant employment losses, and by April 2020, employment had fallen by 15.7% from its February level (consult chart 5). With the gradual reopening of non-essentials services and the relaxation of public health measures, employment grew consistently through the summer and fall. In December 2020 and January 2021, the second wave caused a new, but much smaller, decline in employment. Once Canada has passed this wave, employment rebounded as public health restrictions were once again relaxed. By March 2021, employment levels had reached their highest point since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, but still remained 1.6% (-309,200) below pre-pandemic high.

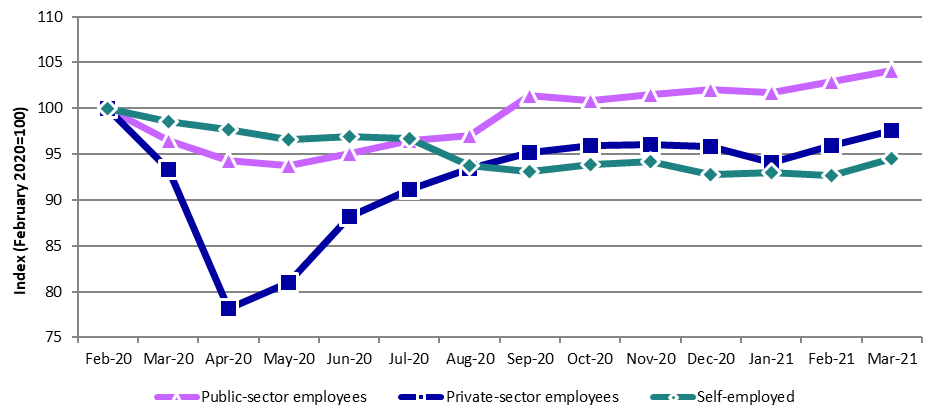

Public health measures imposed led to massive lay-offs in the private sector. The number of private-sector employees fell by 21.8% (-2.7 million) during the first 2 months of the pandemic (consult chart 6). They progressively recovered during the summer and fall, but slightly declined again at the time of the second wave. By the end of FY2021, it had risen to its highest level since February 2020, but still remained 2.5% (-307,800) below pre-pandemic level.

Text description of Chart 6

| Month | Public-sector employees | Private-sector employees | Self-employed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feb-20 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Mar-20 | 96.51566154 | 93.37870536 | 98.51813292 |

| Apr-20 | 94.26985636 | 78.159115 | 97.67829256 |

| May-20 | 93.7764987 | 81.01981857 | 96.57470068 |

| Jun-20 | 95.06385384 | 88.16146183 | 96.89050842 |

| Jul-20 | 96.46683968 | 91.12817732 | 96.74128058 |

| Aug-20 | 97.04242362 | 93.38356087 | 93.70813812 |

| Sep-20 | 101.3567336 | 95.18009889 | 93.09387472 |

| Oct-20 | 100.8942108 | 95.89952335 | 93.90942218 |

| Nov-20 | 101.552021 | 96.07594015 | 94.15582162 |

| Dec-20 | 102.0505178 | 95.82426297 | 92.736422 |

| Jan-21 | 101.7755737 | 94.11593335 | 93.04875933 |

| Feb-21 | 102.9447285 | 95.94565068 | 92.6184279 |

| Mar-21 | 104.1138834 | 97.57467367 | 94.5757418 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. Table 14-10-0288-01.

On the other hand, public-sector employment fell relatively modestly during the first 3 months of the pandemic. At its worst, in May 2020, the number of public-sector employees had fallen by 6.0% (-234,300) compared to February 2020. This is more than 3 times less than that observed in the private-sector. Starting in June 2020, employment in the public sector increased at a relatively steady pace and by March 2021, it was 4.0% (+154,400) higher than its February 2020 level. Public-sector employment includes individuals working in government funded establishments such as hospitals. As a result, the increased employment in this sector partially reflected the growing need for workers in these organisations to meet the new demands brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finally, throughout the fiscal year, the number of self-employed workers in Canada fell gradually. There was no dramatic decline at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and it reported relatively small growth only during a few sporadic months. By the end of FY2021, there were 5.4% fewer self-employed workers (-155,800) than in February 2020.

Turning to full-time and part-time employment, while employment losses were widespread, part-time workers were much more affected. By April 2020, part-time employment had declined by 29.3% compared to February 2020, a rate more than twice as high as the decline in full-time employment. This is largely because part-time workers are more likely to work in sectors that were heavily impacted by public health restrictions or sectors for which teleworking was not an option. Over the course of the summer and the fall, employment grew among both full-time and part-time workers. However, when the second wave hit in January 2021, part-time employment accounted entirely for decline in overall employment. By March 2021, full-time employment was only 1.1% (-168,100) lower than its February 2020 levels, progressing in every month since May 2020. In contrast, part-time employment was still 3.9% (-141,100) below its pre-pandemic levels, as its recovery continued to lag behind that of full-time employment.

Employment by industry

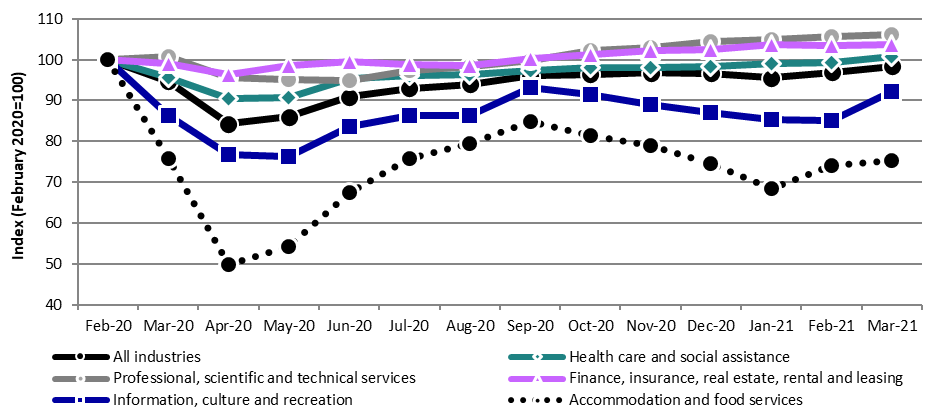

The relative importance of employment losses across industriesFootnote 11 was largely driven by the ease with which social distancing or remote working could be practiced and whether essential services were being provided. Industries with broader remote work options were able to bounce back quickly and maintain employment growth through the remainder of FY2021, despite additional waves of COVID-19 and public health measures. Conversely, industries that were more exposed to constraining public health measures experienced deeper losses and much more volatile employment growth throughout FY2021.

The most severe employment losses were experienced in the accommodation and food services, as well as information, culture, and recreation industries. In April 2020, employment in these industries was 50.2% and 23.1% below pre-pandemic levels, respectively (consult chart 7). These industries experienced another significant decline in employment during the second wave of the pandemic. At the end of FY2021, employment remained 24.8% and 7.7% below February 2020 levels, respectively. Meanwhile, employment losses in finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing; as well as professional, scientific, and technical services industries were more modest. It declined by 3.7% and 4.4% respectively during the first 2 months of the pandemic. Moreover, employment levels had fully recovered by September and October 2020, respectively, in these 2 industries. By the end of FY2021, 8 out of 16 industries had recovered all employment losses recorded during early months of the pandemic.Footnote 12

Employment losses were unevenly spread across enterprises of all sizes over FY2021.Footnote 13 Small-medium-sized and medium-large-sized firms recorded the largest decline in the number of employees. It declines by 27.4% and 21.4%, respectively, in the first quarter of FY2021 relative to their pre-pandemic levels recorded in the third quarter of FY1920.Footnote 14 Small-sized and large-sized firms recorded more modest decline in their payroll (-17.9% and -12.2%, respectively). By the end of FY2021, the distribution of employees by enterprise size shift slightly from medium-sized to small and large-sized enterprises.

Text description of Chart 7

| Month | All industries | Health care and social assistance | Professional, scientific and technical services | Finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing | Information, culture and recreation | Accommodation and food services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feb-20 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Mar-20 | 94.71259324 | 95.72659709 | 100.7147034 | 98.92542619 | 86.42627173 | 75.76474427 |

| Apr-20 | 84.34045843 | 90.57558507 | 95.64680658 | 96.29150844 | 76.88345138 | 49.84093319 |

| May-20 | 86.0193485 | 90.60721063 | 95.04905464 | 98.44065606 | 76.35544108 | 54.18875928 |

| Jun-20 | 90.87998078 | 95.34709045 | 94.89961666 | 99.44251434 | 83.60592402 | 67.46064116 |

| Jul-20 | 92.99086901 | 96.18121442 | 97.27113248 | 98.83655167 | 86.40051513 | 75.87894608 |

| Aug-20 | 93.9932928 | 96.44607843 | 98.31719836 | 98.5860871 | 86.40051513 | 79.55787585 |

| Sep-20 | 95.99918511 | 97.31973435 | 99.72061594 | 100.2100671 | 93.20025757 | 84.77037279 |

| Oct-20 | 96.46931612 | 98.08665402 | 102.2285751 | 101.3331179 | 91.44880876 | 81.29537483 |

| Nov-20 | 96.72318686 | 98.16176471 | 102.8783055 | 102.1895451 | 88.91178364 | 78.92160861 |

| Dec-20 | 96.60356464 | 98.42267552 | 104.4246638 | 102.5773612 | 87.01867354 | 74.54931071 |

| Jan-21 | 95.51808437 | 99.12239089 | 104.8989669 | 103.6115375 | 85.40888603 | 68.53740109 |

| Feb-21 | 96.9415366 | 99.38330171 | 105.7501137 | 103.3287549 | 85.00965873 | 74.12513256 |

| Mar-21 | 98.3848388 | 100.8222644 | 106.204925 | 103.7084916 | 92.27301996 | 75.21004976 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0355-01.

Employment by age group

Youth aged 15 to 24 were disproportionally impacted in FY2021 by the pandemic (consult chart 8), relative to other age groups, as they are more likely to be overrepresented in industries that were severely impacted by the public health restrictions (for example, accommodation and food services; wholesale and retail trade). Indeed, in the first wave of the pandemic (February to April 2020), employment among youth declined by 34.2%, compared with 12.7% for core-age (aged 25 to 54) and 13.0% for older individuals (aged 55 and over).

With successive waves of closures and reopening in these industries, youth employment recovery was much more volatile. Core-age and older workers also suffered job losses, but the immediate impact was much more limited and their recovery has been less bumpy. In March 2021, youth employment remained 6.2% below their pre-pandemic level. In contrast, employment among core-age individuals was 1.2% below February 2020, while employment among older individuals had returned to its pre-pandemic level.

Text description of Chart 8

| Month | 15 to 24 years | 25 to 54 years | 55 years and over |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feb-20 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Mar-20 | 84.11248565 | 96.44489337 | 95.8868943 |

| Apr-20 | 65.8351435 | 87.30979576 | 86.71324005 |

| May-20 | 67.65875809 | 88.69291206 | 89.08096365 |

| Jun-20 | 77.66692265 | 93.35079517 | 91.08279538 |

| Jul-20 | 83.35525047 | 94.74920421 | 92.81920228 |

| Aug-20 | 85.17286152 | 95.68093117 | 93.30765047 |

| Sep-20 | 90.16076811 | 97.36277765 | 94.12488256 |

| Oct-20 | 90.35834406 | 97.7793369 | 94.67347745 |

| Nov-20 | 90.94259874 | 97.90384617 | 94.87939604 |

| Dec-20 | 89.74153512 | 97.7931632 | 95.2737479 |

| Jan-21 | 85.78392777 | 96.95333035 | 95.17822739 |

| Feb-21 | 89.85964395 | 98.0135938 | 95.7376025 |

| Mar-21 | 94.27978666 | 98.56656171 | 97.7351904 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. Table 14-10-0287-01.

Employment by gender

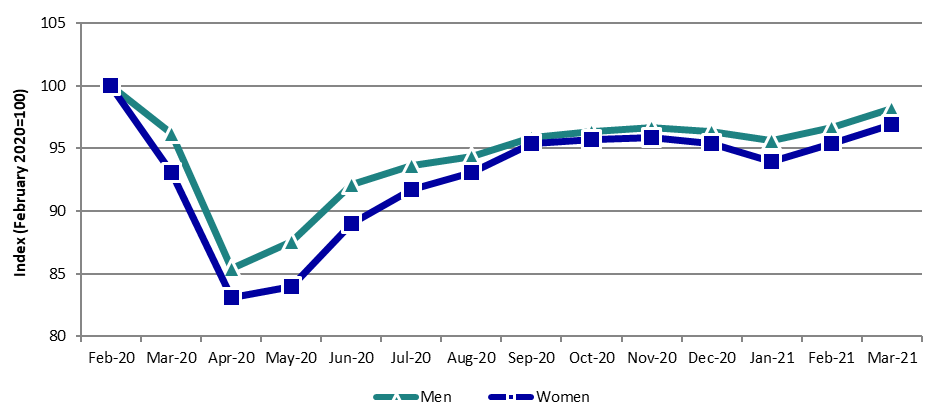

During the first 2 months of the pandemic, employment losses among women were slightly more pronounced (16.8%) than among men (14.6%). In addition, 22.2% of women were still employed, but working less than half their usual hours, compared to 19.1% for men. This reflected the fact that women were more likely than men to work in industries that were severely affected by public health measures. This industries include accommodation and food services; information, culture and recreation; other services; as well as retail trade (27% for women on average in 2019 versus 20% for men, for all 4 of those industries). Because of this, the employment recovery of women also lagged that of men (consult chart 9).

In addition to weak labour market conditions, gender trends in employment during the pandemic were also partly due to balancing work and family obligations.Footnote 15 Employment of parents decreased for both men and women during the pandemic. However, the decline was greater for mothers with children aged less than 12 years old. This is in part because they were more likely to engage in unpaid work such as caring for children or family members.

As previously mentioned, in the initial months of the pandemic, the decline in employment was considerably more pronounced among part-time than full-time workers. This was true for both men and women (consult chart 10). As a greater proportion of women than men work in part-time jobs (25% vs 13%), it also contributed to the larger employment losses observed among women. As business reopened following public health measures easing, full-time employment partially recovered. By the end of FY2021, it was standing 1.4% below its pre-pandemic level for men and 0.7% below for women.

Text description of Chart 9

| Month | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| Feb-20 | 100 | 100 |

| Mar-20 | 96.19482496 | 93.10344828 |

| Apr-20 | 85.38812785 | 83.10344828 |

| May-20 | 87.51902588 | 83.96551724 |

| Jun-20 | 92.08523592 | 88.96551724 |

| Jul-20 | 93.60730594 | 91.72413793 |

| Aug-20 | 94.36834094 | 93.10344828 |

| Sep-20 | 95.89041096 | 95.34482759 |

| Oct-20 | 96.34703196 | 95.68965517 |

| Nov-20 | 96.65144597 | 95.86206897 |

| Dec-20 | 96.34703196 | 95.34482759 |

| Jan-21 | 95.58599696 | 93.96551724 |

| Feb-21 | 96.65144597 | 95.34482759 |

| Mar-21 | 98.17351598 | 96.89655172 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. Table 14-10-0287-01

While the initial impact on part-time employment was similar for men and women, the recovery was faster for men. During the second wave, employment losses were concentrated among part-time workers, affecting both men and women. By the end of FY2021, part-time employment among men had fully recovered, standing 1.6% above its pre-pandemic level. However, for women working part-time, it was still 7.0% below the February 2020 level.

Text description of Chart 10

| Month | Men full-time | Men part-time | Women full-time | Women part-time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feb-20 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Mar-20 | 97.7570817 | 85.79643926 | 95.85210571 | 84.74561668 |

| Apr-20 | 87.37703798 | 71.58500079 | 87.6168811 | 70.27527678 |

| May-20 | 89.50040987 | 74.22404285 | 88.92417685 | 70.82669194 |

| Jun-20 | 93.30767829 | 86.01701591 | 91.2965124 | 83.14306639 |

| Jul-20 | 93.64354677 | 95.84843233 | 92.09713872 | 91.56076337 |

| Aug-20 | 94.27315785 | 96.93556011 | 93.55953735 | 92.59035885 |

| Sep-20 | 96.05155296 | 98.62139594 | 95.64530186 | 95.3991298 |

| Oct-20 | 96.20411695 | 101.2131716 | 96.24651019 | 95.52836772 |

| Nov-20 | 96.60260497 | 101.0004727 | 97.10179181 | 93.73626847 |

| Dec-20 | 96.99995446 | 97.50275721 | 97.5006278 | 91.99586439 |

| Jan-21 | 96.9737681 | 91.69686466 | 97.66902522 | 85.82690734 |

| Feb-21 | 97.42121323 | 98.32991965 | 98.49771777 | 89.82466721 |

| Mar-21 | 98.60073777 | 101.6228139 | 99.33231901 | 93.03838366 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. Table 14-10-0287-01.

Examining the role of the Canada Emergency Response Benefit during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic

A recent departmental study* examined the usage of the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) patterns and how short-term labour market outcomes differed between laid off CERB recipients and non-recipients.

The study found that workers in “hard-hit” industries (that is, workers in the arts, entertainment and recreation industry and the accommodation and food services industry) displayed the highest likelihoods of layoffs. Educational service workers also had a high likelihood of layoff (but a seasonal component needs to be taken into account) and finally, workers in the finance and insurance industry had the lowest likelihood of layoff.

Younger workers, those aged between 15 and 24, were disproportionally impacted, with employment losses significantly more pronounced than other age groups. Overall, workers who are more concentrated in those “hard-hit” industries, namely women, youth, immigrant, less educated, as well as low paid, low tenure, part-time, and private sector employees were more likely to be laid off than their respective counterparts.

Across nearly all characteristics studied, those who displayed higher layoff likelihoods were also more likely to receive the CERB than their counterparts. These workers also tended to receive the CERB for a longer period of time (or with lower exit likelihoods); however, there are noteworthy exceptions to this pattern, including young workers and workers in the construction industry, the finance and insurance industry, and the professional, scientific and technical services industry.

Laid off workers who had not received CERB payments in a given month were more likely to be re-employed the following month than CERB recipients.

Overall, these results suggest that the factors associated with CERB use and duration were very similar to those that determined layoffs during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. The results hold for both men and women.

*ESDC, Examining the role of the Canada Emergency Response Benefit during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (Ottawa: ESDC, Economic Policy Directorate, 2022).

Employment rates

The indicator of employment growth presented in the previous section does not take into consideration the working-age population growth. The measure of employment rate, which is the proportion of people aged 15 years and over who were employed, accounts for that.

The employment rate dropped significantly during the first 2 months of the pandemic, falling by nearly 10 percentage points from 61.9% in February to 52.1% in April 2020. As the pandemic ran its course, the rate followed similar patterns to that of employment levels, finally bouncing back to 60.3% at the end of FY2021. However, by March 2021, the employment rate remained well below the level observed in February 2020 (61.9%). This reflects the fact that not only employment had not fully recovered, but also the working age population had increased over the fiscal year.

The decline in employment rates was widespread across all the Canadian population. As already mentioned, youth were disproportionally impacted by the pandemic. This was also reflected in their employment rate, which fell by 19.9 percentage points during the first 2 months (58.1% in February 2020 to 38.2% in April 2020). By March 2021, their employment rate had recovered significantly but remained 3.4 percentage points below its pre-pandemic level. Individuals aged 25 to 54 experienced a 10.6 percentage points decline in their employment rate during the first 2 months of the pandemic. Those aged 55 and over recorded a milder decline of 4.8 percentage points. By the end of FY2021, both had recovered a large part of that loss. The employment rate of individuals aged 25 to 54 stood at 82.0% compared to 83.2% in February 2020. For those aged 55 and over, it stood at 35.3%, compared to 36.1% prior to the pandemic.

Men and women recorded similar decline in their employment rates during the first 2 months of the pandemic (-9.7 percentage points for men and -9.8 for women). However the recovery was slower for women. By the end of FY2021, the employment rate for men stood at 64.5% compared to 65.8% in February 2020, a gap of 1.3 percentage points. Women’s employment rate stood at 56.2% compared to 58.0% prior to the pandemic, a gap of 1.8 percentage points.

Unemployment rates

By May 2020, the number of unemployed individuals reached its highest level since comparable data collection began in 1976. The number of unemployed individuals increased from 1.2 million in February 2020 to 2.6 million in May 2020. Over the same period, the unemployment rate more than double, from 5.7% to 13.4%. As public health restrictions loosened over the summer and fall, many individuals returned to work. As a result, unemployment and the unemployment rate fell consistently until the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, which brought a temporary rebound in both. By the end of the fiscal year, both were at their lowest levels since the COVID-19 pandemic began. After peaking at 2.6 million in May 2020, unemployment had fallen to 1.5 million in March 2021, still remaining 31.5% (+364,600) higher than its February 2020 level. Correspondingly, the unemployment rate had fallen to 7.5% in March 2021.

Focusing solely on the unemployment rate, however, underestimates the true impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. As individuals who left the labour force were not counted as unemployed, the unemployment rate underestimated unused labour. Labour underutilizationFootnote 16, a broader measure of unemployment that includes inactive individuals that wanted to work, but did not look, increased from 11.4% in February 2020 to 36.1% in April. This increase was explained by the number of individuals who wanted to work but did not look, which almost quadruple. As with the unemployment rate, the labour utilization rate declined relatively quickly, standing at 14.7% in March 2021.

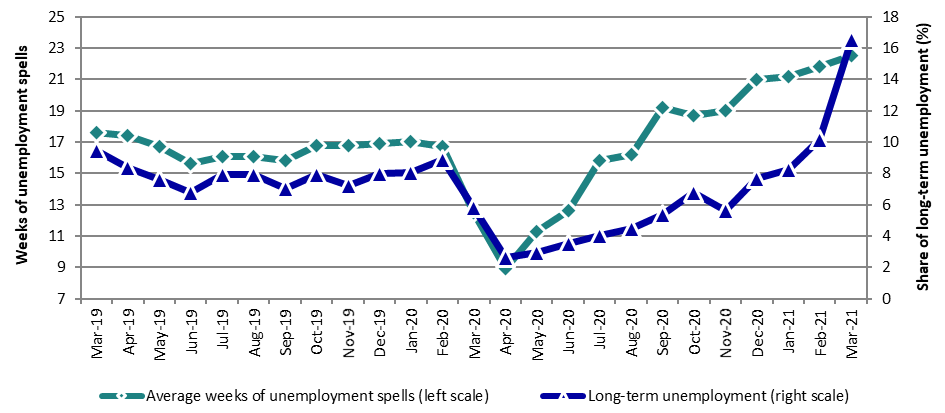

Duration of unemployment

In addition to the large overall increase in unemployment, the COVID-19 pandemic also had an important impact on unemployment duration and the share of long-term unemployed.Footnote 17 The number of new unemployed individuals increased significantly due to the early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. This lead to a quick decline in the average duration of unemployment, from 16.7 weeks in February 2020 to 8.9 weeks in April 2020 (consult chart 11). The same happened with long-term unemployment. In February 2020, they accounted for 8.9% of total unemployment, a share that had remained relatively stable throughout FY1920. By April 2020, the share of long-term unemployed fell to 2.6% as a result of the increase in newly unemployed individuals. While the unemployed who had been temporary laid off gradually returned to their jobs, a significant number of those who had permanently lost their job remained jobless for several months. As a result, the average duration of unemployment and the share of long-term unemployment increased constantly throughout FY2021, reaching 22.5 weeks and 16.5%, respectively, in March 2021. Compared to their respective pre-pandemic levels, this is 6 more weeks of unemployment and almost twice the share of long-term-unemployed.

Text description of Chart 11

| Month | Average weeks of unemployment spells (left scale) | Long-term unemployment (%) (right scale) |

|---|---|---|

| Mar-19 | 17.6 | 9.48 |

| Apr-19 | 17.4 | 8.38 |

| May-19 | 16.7 | 7.62 |

| Jun-19 | 15.6 | 6.75 |

| Jul-19 | 16.1 | 7.92 |

| Aug-19 | 16.1 | 7.93 |

| Sep-19 | 15.8 | 7.04 |

| Oct-19 | 16.8 | 7.92 |

| Nov-19 | 16.8 | 7.23 |

| Dec-19 | 16.9 | 7.97 |

| Jan-20 | 17 | 8.03 |

| Feb-20 | 16.7 | 8.88 |

| Mar-20 | 12.5 | 5.81 |

| Apr-20 | 8.9 | 2.60 |

| May-20 | 11.3 | 2.95 |

| Jun-20 | 12.6 | 3.49 |

| Jul-20 | 15.8 | 4.05 |

| Aug-20 | 16.2 | 4.49 |

| Sep-20 | 19.2 | 5.35 |

| Oct-20 | 18.7 | 6.77 |

| Nov-20 | 19 | 5.65 |

| Dec-20 | 21 | 7.70 |

| Jan-21 | 21.2 | 8.24 |

| Feb-21 | 21.8 | 10.14 |

| Mar-21 | 22.5 | 16.55 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour force Survey, Table 14-10-0342-01.

- *Long-term unemployment is defined as unemployed individuals who have been searching for a job for a period of at least 12 consecutive months. The percentages presented in this chart are the long-term unemployed as a proportions of all unemployed individuals.

Long-term unemployment is usually more common among older individuals. In February 2020, the share of long-term unemployed was 13.0% among those aged 55 and over, compared to 8.9% among the core-age and 5.8% among youth. By the end of FY2021, the share of long-term unemployed had increased to 24.2% among older individuals, 18.2% among core-age and 7.8% among youth. Similarly, relative to February 2020, at the end of FY2021, the average duration of unemployment increased by 7.9 weeks among older workers reaching 29.6 weeks. Among core-age, it increase by 7.3 week, reaching 24.5 weeks. Among youth, the duration increased by only 2.8 weeks, reaching 14.5 weeks.

Prior to the pandemic, the share of long-term unemployment was similar for men and women. Compared to February 2020, by the end of FY2021, the share of long-term unemployment reached 18.4% for men compared to 14.3% for women. Unemployment duration increased by 6.9 weeks for men, reaching 24.4 weeks, while it increased by 4.8 weeks for women, reaching 20.4 weeks.

Reasons for unemployment

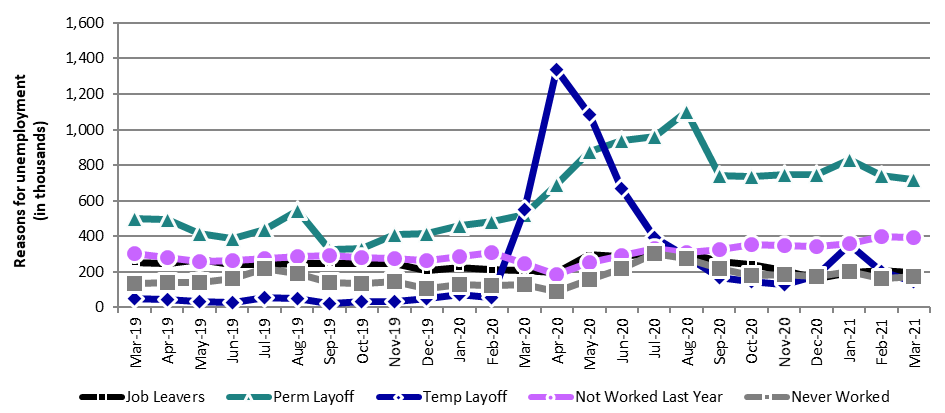

In general, workers can become unemployed for a number of reasons, and the cause of unemployment is a key factor in determining if the individual is eligible for EI benefits.Footnote 18 As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, and subsequent variation in labour market conditions, reasons for unemployment significantly shifted during FY2021.

At the beginning of the pandemic, as businesses expected closures to be short and anticipated a relatively quick return to normal, several Canadian were temporarily laid off. As a result, temporary layoffs quickly accounted for a little more than half of total unemployment by April 2020 (53%). A large proportion of those who were temporarily laid off returned to work relatively quickly. By the end of the FY2021, they accounted for less than 10% of total unemployment (consult chart 12). However, as the economy was still operating under a number of restrictions, permanent layoffs started to grow and outpaced the number of temporary layoffs. By the end of FY2021, temporary and permanent layoffs accounted for 10% and 44% of unemployed, respectively, slightly above their pre-pandemic share.Footnote 19

Individuals who have not worked in the previous year and those who had never worked before accounted for 37% of total unemployment in February 2020. During the first 2 months of the pandemic, their numbers fell by 35.9%, as a number of them became inactive. By the end of FY2021, their number had doubled.

Text description of Chart 12

| Month | Job Leavers | Permanent Layoffs | Temporary Layoffs | Not Worked Last Year | Never Worked |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mar-19 | 254.4 | 500.2 | 53 | 302.2 | 133 |

| Apr-19 | 244.4 | 492.5 | 44.6 | 279.2 | 138.7 |

| May-19 | 271.1 | 417.8 | 32.6 | 258.7 | 141.5 |

| Jun-19 | 241 | 387.6 | 29.5 | 261.9 | 162.4 |

| Jul-19 | 244 | 438.7 | 57.8 | 272.5 | 217.7 |

| Aug-19 | 249.7 | 547.4 | 49.3 | 284.7 | 189.5 |

| Sep-19 | 247.9 | 326.7 | 20.7 | 290.9 | 139.8 |

| Oct-19 | 246 | 328.9 | 32.1 | 280.4 | 137 |

| Nov-19 | 244.7 | 411.7 | 33 | 275.3 | 144.6 |

| Dec-19 | 206.4 | 415.3 | 48.8 | 264.3 | 107.2 |

| Jan-20 | 224.7 | 463.2 | 75.4 | 284.1 | 131.4 |

| Feb-20 | 211.6 | 481.6 | 58.1 | 310.1 | 124.7 |

| Mar-20 | 206.2 | 520.3 | 549.7 | 247.5 | 128 |

| Apr-20 | 196.3 | 692.6 | 1336.4 | 187.3 | 91.3 |

| May-20 | 295.9 | 875.8 | 1084.1 | 254.2 | 156.9 |

| Jun-20 | 288.8 | 937.5 | 666.4 | 293.8 | 220.1 |

| Jul-20 | 310.6 | 962 | 391.5 | 328.7 | 300.5 |

| Aug-20 | 308.9 | 1102.4 | 284.7 | 311 | 275.2 |

| Sep-20 | 255.6 | 741 | 169.5 | 327.7 | 216.3 |

| Oct-20 | 243.5 | 733.5 | 146.7 | 351.8 | 181.9 |

| Nov-20 | 206.9 | 748.2 | 130.4 | 345.9 | 187.4 |

| Dec-20 | 165.2 | 749.5 | 178 | 344.1 | 175.9 |

| Jan-21 | 194 | 833.8 | 356.1 | 359.8 | 201.5 |

| Feb-21 | 209.8 | 744.1 | 203.7 | 398.7 | 164.1 |

| Mar-21 | 196 | 719.6 | 144.2 | 395.1 | 176.7 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. Table 14-10-0125-01. Data not adjusted for seasonality.

Hours of work

The number of hours of insurable employment is a key eligibility criterion of the EI program, as claimants must have worked a minimum number of insurable hours in the previous year to qualify for EI benefits. It also determines, along with the regional unemployment rate, the maximum number of weeks of EI regular benefits a claimant is entitled to receive.

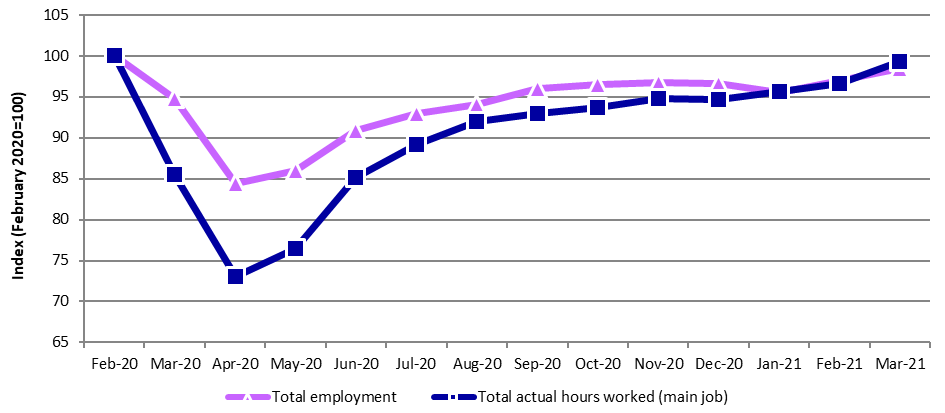

The total number of hours actually worked by Canadians declined significantly at the beginning of FY2021. This was due to the massive employment losses, as well as the significant number of Canadians that were employed, but that worked reduced hours due to public health measures. As a result, the level of actual hours worked was 27.0% below pre-pandemic levels in April 2020 (consult chart 13). Since then, actual hours worked increased every month throughout the remainder of the fiscal year. There was 1 exception, a slight decline in December 2020, coinciding with the second wave of the pandemic. By the end of FY2021, actual hours worked were still 0.8% below their February 2020 level.

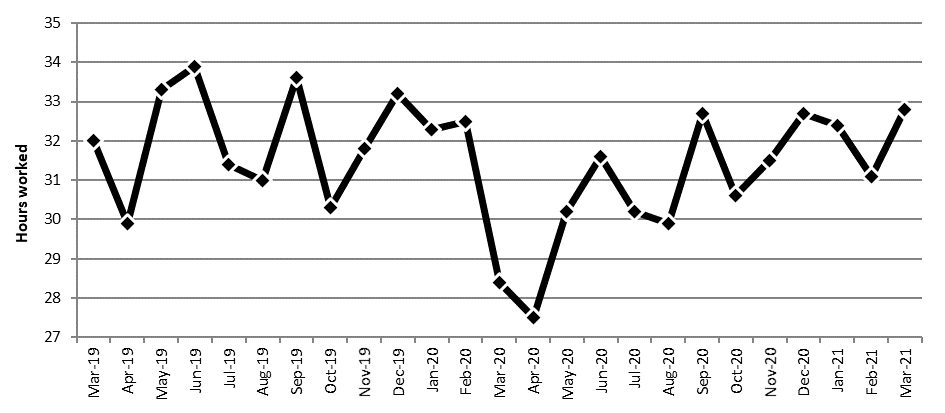

As mentioned previously, many workers suffered a significant reduction in the number of hours worked. As a result, the average of actual hours worked per worker fell from 32.5 hours a week in February 2020 to 27.5 hours in April (consult chart 14). This means that on a year-over-year basis, March, April, and May of 2020, the average declined by 11.2%, 8.0%, and 9.3%, respectively. The average then rebounded through the summer of 2020 and remained near levels observed in the previous year for most of the second wave of the pandemic. Following the second waves of COVID-19 cases, public health measures were eased further. This resulted in an increase in the average of actual hours worked, reaching 32.8 hours a week in March 2021, 2.5% above the level observed in March 2019.

Text description of Chart 13

| Month | Total employment | Total actual hours worked (main job) |

|---|---|---|

| Feb-20 | 100 | 100 |

| Mar-20 | 94.71259324 | 85.43656327 |

| Apr-20 | 84.34045843 | 73.02222914 |

| May-20 | 86.0193485 | 76.50503244 |

| Jun-20 | 90.87998078 | 85.08686483 |

| Jul-20 | 92.99086901 | 89.10400595 |

| Aug-20 | 93.9932928 | 91.8988779 |

| Sep-20 | 95.99918511 | 92.93923908 |

| Oct-20 | 96.46931612 | 93.71065277 |

| Nov-20 | 96.72318686 | 94.78428302 |

| Dec-20 | 96.60356464 | 94.6878583 |

| Jan-21 | 95.51808437 | 95.66376164 |

| Feb-21 | 96.9415366 | 96.64261871 |

| Mar-21 | 98.3848388 | 99.2289198 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. Table 14-10-0287-01 and 14-10-0289-01.

Text description of Chart 14

| Month | Hours worked |

|---|---|

| Mar-19 | 32 |

| Apr-19 | 29.9 |

| May-19 | 33.3 |

| Jun-19 | 33.9 |

| Jul-19 | 31.4 |

| Aug-19 | 31 |

| Sep-19 | 33.6 |

| Oct-19 | 30.3 |

| Nov-19 | 31.8 |

| Dec-19 | 33.2 |

| Jan-20 | 32.3 |

| Feb-20 | 32.5 |

| Mar-20 | 28.4 |

| Apr-20 | 27.5 |

| May-20 | 30.2 |

| Jun-20 | 31.6 |

| Jul-20 | 30.2 |

| Aug-20 | 29.9 |

| Sep-20 | 32.7 |

| Oct-20 | 30.6 |

| Nov-20 | 31.5 |

| Dec-20 | 32.7 |

| Jan-21 | 32.4 |

| Feb-21 | 31.1 |

| Mar-21 | 32.8 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0042-01.

WagesFootnote 20

Earnings are also an important element for the administration of the EI program. They determine the EI premiums paid by employers and employees, as well as the level of benefits that claimants can receive. Earnings can be a combination of hourly wages and hours worked, a fixed amount paid for a specific time period (for example, a week) or in the form of commissions, tips or bonuses.Footnote 21 Indicators of average hourly wages and average weekly earnings are therefore examined.

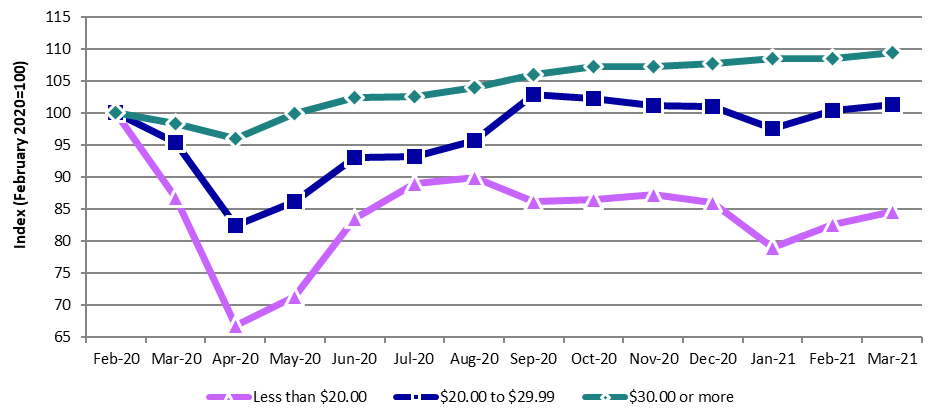

First, looking at the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic by hourly earnings threshold, low-wage employeesFootnote 22 were disproportionately impacted. When analyzing the distribution of job losses by wage group, we can see that employees earning less than $20.00 per hour were significantly more affected by the crisis than others (consult chart 14). This group represents one-third of all employees. Compared to February 2020, employment among these employees was down by one-third in April 2020. In comparison, it fell by 17.6% for those earning between $20 and $29.99 per hour, and by only 4% among those earning more than $30. Moreover, by March 2021, employees with higher wages had fully recovered their pre-pandemic level. By contrast, the number of low-wage employees was still 15.3% below its pre-pandemic level (consult chart 15).

Text description of Chart 15

| Month | Less than $20.00 | $20.00 to $29.99 | $30.00 or more |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feb-20 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Mar-20 | 86.88929534 | 95.42750156 | 98.34322537 |

| Apr-20 | 66.79237456 | 82.42770959 | 95.98439885 |

| May-20 | 71.41213961 | 86.14520491 | 99.92538579 |

| Jun-20 | 83.48386853 | 92.97274808 | 102.3537392 |

| Jul-20 | 89.00118794 | 93.25982942 | 102.5029676 |

| Aug-20 | 89.93268342 | 95.63137092 | 103.9952518 |

| Sep-20 | 86.15390417 | 102.8250468 | 106.0183144 |

| Oct-20 | 86.56119774 | 102.2384023 | 107.2443615 |

| Nov-20 | 87.32675881 | 101.2003328 | 107.2392742 |

| Dec-20 | 86.05208078 | 101.0380695 | 107.6632186 |

| Jan-21 | 78.98101182 | 97.64510089 | 108.4517551 |

| Feb-21 | 82.6391115 | 100.389016 | 108.5484144 |

| Mar-21 | 84.69820678 | 101.3397129 | 109.4471765 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. Table 14-10-0113-01.

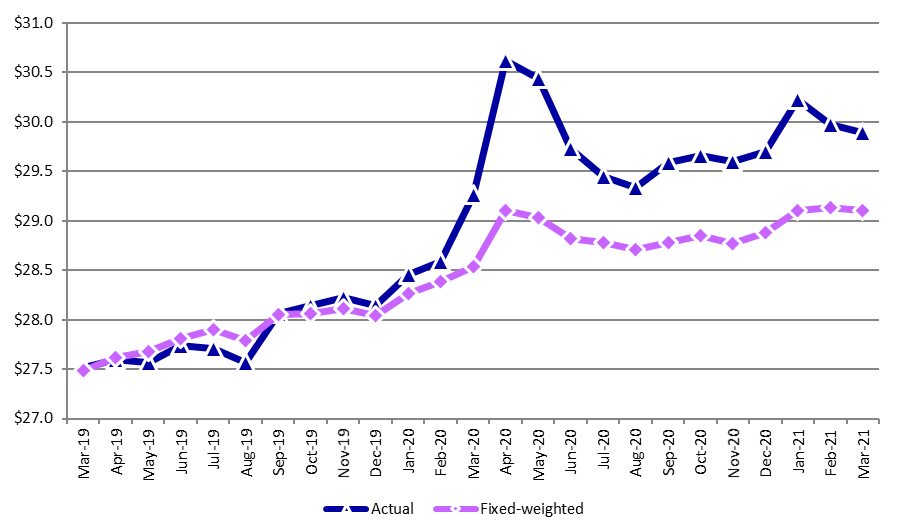

This reflects the fact that the 2 industries with the highest share of low-wage employees, accommodation and food services and retail trade, were among those that were hit the hardest. This means that those still employed were, on average, earning more than those who had lost their job. This caused a shift in the wage distribution that resulted in a higher overall nominal average hourly wage in months following the closure of the economy. Based on Labour Force Survey (LFS) data, in April 2020, average hourly wage was up by 10.9% (+$3.02) compared to April 2019Footnote 23, reaching $30.62 per hour. As low-wage employees were slowly re-employed, the nominal average hourly wage dropped from its inflated level and by March 2021. It had declined to $29.89, remaining 8.6% (+$2.37) above their March 2019 level, as the number of low-wage employees remained below their pre-pandemic level (consult chart 16).

Statistics Canada published a fixed-weighted average wage using LFS data to paint a picture of wage trends that are less influenced by these structural shifts. This approach maintains employment composition by occupation and tenure at the 2019 average. The fixed-weighted nominal average hourly wage was 5.4% (+$1.48) higher in April 2020 than in April 2019, reaching $29.10 per hour.Footnote 24 By the end of FY2021, the fixed-weighted nominal hourly wage still stood at $29.10, 5.9% (+$1.61) above its March 2019 level.

Text description of Chart 16

| Month | Actual | Fixed-weighted |

|---|---|---|

| Mar-19 | 27.52 | 27.49 |

| Apr-19 | 27.6 | 27.62 |

| May-19 | 27.57 | 27.68 |

| Jun-19 | 27.74 | 27.81 |

| Jul-19 | 27.71 | 27.9 |

| Aug-19 | 27.57 | 27.79 |

| Sep-19 | 28.06 | 28.05 |

| Oct-19 | 28.14 | 28.06 |

| Nov-19 | 28.22 | 28.11 |

| Dec-19 | 28.14 | 28.04 |

| Jan-20 | 28.46 | 28.26 |

| Feb-20 | 28.59 | 28.39 |

| Mar-20 | 29.27 | 28.54 |

| Apr-20 | 30.62 | 29.1 |

| May-20 | 30.44 | 29.03 |

| Jun-20 | 29.73 | 28.82 |

| Jul-20 | 29.45 | 28.78 |

| Aug-20 | 29.34 | 28.71 |

| Sep-20 | 29.59 | 28.78 |

| Oct-20 | 29.66 | 28.85 |

| Nov-20 | 29.6 | 28.77 |

| Dec-20 | 29.7 | 28.88 |

| Jan-21 | 30.23 | 29.1 |

| Feb-21 | 29.97 | 29.13 |

| Mar-21 | 29.89 | 29.1 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Custom tabulation.

Similarly, the nominal average weekly wage increased significantly at the beginning of the pandemic, by 9.5% in April 2020 compared to the same months in 2019. The average wage was influenced not only by the average hourly wage, but also by the number of hours worked per worker. As low-wage employment progressively increase, the annual growth in nominal weekly wage slowly declined. However, it remained at 7.0% in March 2021, reaching $1,120.90 a week compared to $1,047.79 a year earlier, an increase of $73.11 per week.Footnote 25

During FY2021, the inflation rate fluctuated significantly as the massive output losses experienced during the first 2 months led to price declines. The inflation rate fell from 2.2% in February 2020 to -0.4% in May 2020. With the progressive reopening and economic recovery, prices started to go up, and inflation rate was back at 2.2% in March 2021.Footnote 26

As a result, the real average hourly wage also fluctuated significantly during the period. By April 2020, the average real hourly wage was up by 11.2%, and by a more modest 5.6% based on the fixed-weighted measure. From that point, gains in real average hourly wage progressively fell and ended FY2021 at essentially the same level as it was in March 2020. Looking over a 2-year period to smooth out the heavy fluctuations, real average hourly wage was up by 5.3% in March 2021 compared to March 2019. Looking at the fixed-weighted measure, the increase was a more modest 2.7%. Similarly, in March 2021, the average real weekly wage was up by 7.1% compared to March 2019.

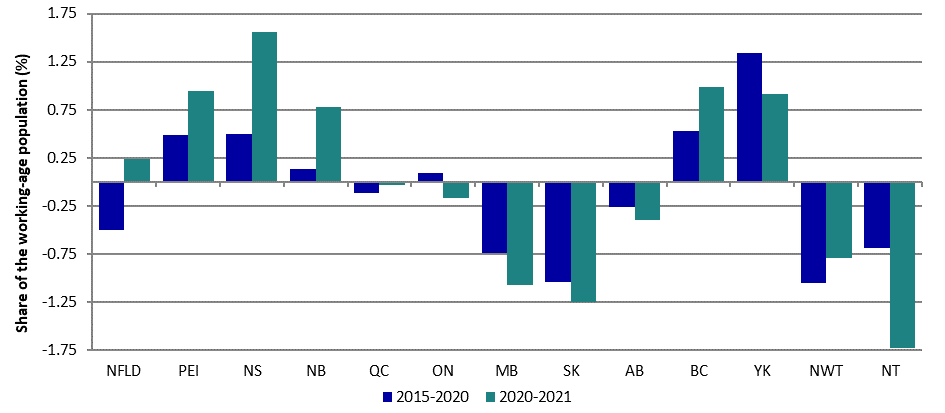

1.2.1 Canada’s regional labour market

Canada’s regional labour markets were characterized by high volatility during FY2021 because of the evolving COVID-19 crisis and the different associated public health measures. The fiscal year started with record employment losses across the country, followed by an inconsistent recovery. By April 2020, every province experienced employment declines greater than 13.0% relative to the pre-pandemic levels, mostly led by Quebec who recorded the largest employment losses. By the end of FY2021, British Columbia had temporarily recovered all the employment losses suffered during the pandemic.

Looking at industries, the impacts of COVID-19 in Canada’s regional labour markets were fairly similar during FY2021, although different in magnitude. Due to the nature of the pandemic, employment losses were largely driven by the same characteristics across all regions. That is, workers in industries in which physical distancing was difficult and remote work options were limited were especially at risk, regardless of region. The accommodation and food services; as well as the information, culture, and recreation industries experienced above average employment declines in every province. Conversely, the finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing and professional; as well as the scientific and technical services industries experienced relatively mild declines in each province. The health care and social assistance sector, which led the frontline fight against COVID-19 in FY2021, maintained above average employment growth in every province except for Manitoba.

Labour force

Each province experienced a significant decline in their respective labour force and participation rate in March and April 2020, as a significant proportion of individuals dropped out of the labour force. The largest labour force declines were observed in Nova Scotia (-12.1%), Prince Edward Island (-12.0%), and Newfoundland and Labrador (-11.1%). Those same provinces also experienced declines in labour force participation rates that were greater than the national average, along with Ontario, Alberta, and British Columbia. Quebec experienced the lowest declines in labour force and participation rates, in part due to the high proportion of workers temporarily laid off relative to the other provinces.Footnote 27 Notable declines were also observed in the territories at the beginning of the pandemic, especially Nunavut (consult table 1).

By September 2020, provincial labour forces were at or within 1% of pre-pandemic levels in the majority of provinces. There was 3 exceptions, Prince Edward Island (-4.8%), Nova Scotia (-3.9%), and Saskatchewan (-2.6%). During the second wave of the pandemic in the ensuing months, provinces were able to avoid the scale of labour force exit experienced during the first wave. As a result, most provincial labour forces and participation rates were near or above pre-pandemic levels by the end of the fiscal year. Prince Edward Island and Saskatchewan were the 2 exceptions to this. Their labour force and participation rates remained notably lower than their relative pre-pandemic level, when compared to other provinces. In the territories, the labour force fully recovered in Yukon and Northwest Territories during the final quarter of FY2021. Nunavut’s labour force and participation rate remained, however, well below pre-pandemic levels.

| Province or territory | Characteristic | Apr-20 | May-20 | Jun-20 | Jul-20 | Aug-20 | Sep-20 | Oct-20 | Nov-20 | Dec-20 | Jan-21 | Feb-21 | Mar-21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NFL | Growth (%) | -11.1 | -5.8 | -5.1 | -3.1 | -4.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | -0.2 | 0.2 | -0.8 | -4.1 | -1.3 |

| NFL | Participation rate (%) | 51.0 | 54.1 | 54.5 | 55.6 | 55.0 | 57.4 | 57.6 | 57.3 | 57.5 | 57.0 | 55.1 | 56.7 |

| PEI | Growth (%) | -12.0 | -6.5 | -1.9 | -4.0 | -3.0 | -4.8 | -3.3 | -2.4 | -3.1 | -4.4 | -3.5 | -3.4 |

| PEI | Participation rate (%) | 59.3 | 63.0 | 66.0 | 64.5 | 65.1 | 63.9 | 64.9 | 65.4 | 64.8 | 64.0 | 64.6 | 64.5 |

| NS | Growth (%) | -12.1 | -9.3 | -3.1 | -4.7 | -3.9 | -3.9 | -2.2 | -2.9 | -1.7 | -0.8 | -0.2 | 0.3 |

| NS | Participation rate (%) | 55.0 | 56.7 | 60.5 | 59.5 | 60.0 | 59.9 | 60.9 | 60.4 | 61.1 | 61.7 | 62.1 | 62.3 |

| NB | Growth (%) | -7.7 | -3.5 | -0.2 | 0.1 | -0.5 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.9 |

| NB | Participation rate (%) | 56.2 | 58.7 | 60.7 | 60.8 | 60.5 | 61.4 | 61.6 | 61.9 | 61.6 | 61.2 | 60.8 | 61.2 |

| QC | Growth (%) | -6.2 | -4.6 | -1.8 | -1.1 | -0.4 | -0.2 | -0.3 | -0.4 | -1.1 | -1.5 | -1.0 | -0.5 |

| QC | Participation rate (%) | 60.8 | 61.8 | 63.6 | 64.1 | 64.4 | 64.5 | 64.4 | 64.3 | 63.8 | 63.5 | 63.8 | 64.1 |

| ON | Growth (%) | -9.1 | -7.4 | -3.5 | -2.1 | -1.2 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.1 | -0.7 | -0.1 | 0.5 |

| ON | Participation rate (%) | 59.1 | 60.2 | 62.7 | 63.5 | 64.0 | 64.9 | 65.1 | 65.0 | 65.3 | 64.1 | 64.5 | 64.8 |

| MB | Growth (%) | -8.2 | -6.1 | -2.3 | -1.8 | -1.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | -2.0 | -2.3 | -2.1 | -0.8 | -0.2 |

| MB | Participation rate (%) | 61.5 | 62.9 | 65.4 | 65.7 | 66.1 | 67.2 | 67.0 | 65.5 | 65.3 | 65.4 | 66.2 | 66.6 |

| SK | Growth (%) | -8.2 | -6.9 | -2.8 | -2.4 | -3.3 | -2.6 | -2.9 | -2.7 | -2.9 | -3.4 | -2.9 | -3.4 |

| SK | Participation rate (%) | 63.3 | 64.3 | 67.1 | 67.4 | 66.8 | 67.3 | 67.0 | 67.2 | 67.0 | 66.7 | 67.0 | 66.6 |

| AB | Growth (%) | -9.3 | -6.0 | -1.6 | -1.2 | -1.6 | -0.1 | 0.0 | -0.4 | -0.6 | -0.2 | -0.4 | -0.4 |

| AB | Participation rate (%) | 63.7 | 66.0 | 69.0 | 69.2 | 68.9 | 69.8 | 69.8 | 69.5 | 69.3 | 69.5 | 69.3 | 69.3 |

| BC | Growth (%) | -9.3 | -6.1 | -1.1 | -0.6 | -1.1 | -0.9 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 2.6 |

| BC | Participation rate (%) | 58.9 | 61.0 | 64.1 | 64.4 | 64.0 | 64.1 | 64.7 | 64.9 | 65.0 | 65.4 | 65.5 | 66.1 |

| YK* | Growth (%) | -2.6 | -4.3 | -3.0 | -2.1 | -1.3 | -3.8 | -2.1 | -1.7 | -0.9 | -1.7 | -1.3 | 0.0 |

| YK* | Participation rate (%) | 71.3 | 70.1 | 70.8 | 71.2 | 71.8 | 69.8 | 71.0 | 71.3 | 71.9 | 71.3 | 71.6 | 72.5 |

| NWT* | Growth (%) | -2.5 | -3.3 | -4.9 | -4.5 | -4.9 | -5.7 | -4.1 | -2.9 | -1.6 | -1.2 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| NWT* | Participation rate (%) | 70.4 | 69.6 | 68.4 | 68.9 | 68.4 | 67.8 | 69.0 | 69.9 | 70.8 | 71.1 | 72.6 | 72.6 |

| NT* | Growth (%) | -4.1 | -10.1 | -11.5 | -2.7 | -2.0 | -1.4 | -4.1 | -5.4 | -9.5 | -12.2 | -12.2 | -10.8 |

| NT* | Participation rate (%) | 58.2 | 54.1 | 53.3 | 58.2 | 58.6 | 58.8 | 57.1 | 56.3 | 54.1 | 52.3 | 52.1 | 53.0 |

| Canada** | Growth (%) | -8.5 | -6.3 | -2.4 | -1.6 | -1.2 | -0.3 | 0.1 | -0.1 | 0.0 | -0.6 | -0.3 | 0.3 |

| Canada** | Participation rate (%) | 59.9 | 61.3 | 63.8 | 64.3 | 64.5 | 65.1 | 65.3 | 65.1 | 65.1 | 64.7 | 64.8 | 65.2 |

- Sources: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0287-01 for Canada and provinces and Table 14-10-0292-01 for territories.

- * 3-month moving average.

- ** Excluding territories.

Employment

FY2021 began with unprecedented job losses, with employment declining by more than 13.0% in every province during the first 2 months of the pandemic. Compared to February 2020 levels, the greatest employment losses were recorded in Quebec (-18.9%), followed by Nova Scotia (-16.0%). The lowest declines in employment occurred in Saskatchewan (-13.0%) and Manitoba (-13.8%). The employment rate fell by more than 7.0 pp. in each province over the same period, with the largest declines observed in Quebec (-11.7 pp) and Alberta (-9.9 pp). In the territories, Nunavut experienced the largest declines in both employment (-14.1%) and the employment rate (-7.5 pp) relative to the pre-pandemic period (consult table 2).

Employment started to rebound in all provinces with the gradual easing of public health measures throughout the summer of 2020. However, the recovery stalled with the onset of the second wave of the pandemic in September 2020. Employment losses during the second wave peaked in December 2020 and January 2021, with Prince Edward Island, Quebec, Ontario, and the Prairie provinces experiencing above average employment declines. Despite the second wave, British Columbia was able to maintain consistent employment growth until the end of FY2021. At this point, employment in the province had exceeded pre-pandemic levels (+0.8%). Conversely, Saskatchewan and Prince Edward Island were still the most affected provinces in terms of employment losses (-4.2% and -3.3%, respectively) and employment rates (-2.8 pp, for both). The Northwest Territories was the only territory with higher employment (+3.6%) and a higher employment rate (+1.9 pp) relative to the pre-pandemic period during the final quarter of FY2021.

Unemployment

The increase in total unemployment between February 2020 and April 2020 was largely driven by temporary layoffs. It was especially the case in Quebec, where unemployment rose by 260.1% and the unemployment rate by 12.9 pp. Among other provinces, British Columbia and Manitoba experienced the largest increases in total unemployment (+102.7% and +94.3%, respectively) and the unemployment rate (+6.4 pp and +5.8 pp, respectively). Modest increases occurred in Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia, where the unemployment rates were the highest prior to the pandemic. The largest rise in unemployment in the territories during the first quarter of FY2021 occurred in Yukon. Conversely, Nunavut experienced a decline in its unemployed population. Despite this, Nunavut recorded the highest rise in the unemployment rate over the same period as the labour force decline exceeded the decline in unemployment.

| Province or territory | Characteristic | Apr-20 | May-20 | Jun-20 | Jul-20 | Aug-20 | Sep-20 | Oct-20 | Nov-20 | Dec-20 | Jan-21 | Feb-21 | Mar-21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NFL | Growth (%) | -14.5 | -10.5 | -10.0 | -7.0 | -4.9 | -2.9 | -0.3 | -0.8 | -0.7 | -1.4 | -7.5 | -1.5 |

| NFL | Employment rate (%) | 42.9 | 45.0 | 45.2 | 46.7 | 47.8 | 48.8 | 50.1 | 49.8 | 49.9 | 49.6 | 46.5 | 49.5 |

| PEI | Growth (%) | -14.7 | -11.7 | -8.6 | -7.3 | -5.5 | -7.0 | -5.7 | -4.9 | -5.1 | -4.4 | -4.8 | -3.3 |

| PEI | Employment rate (%) | 52.8 | 54.6 | 56.5 | 57.2 | 58.3 | 57.3 | 58.0 | 58.5 | 58.3 | 58.8 | 58.5 | 59.3 |

| NS | Growth (%) | -16.0 | -14.1 | -8.0 | -7.2 | -5.9 | -3.8 | -3.1 | -1.3 | -2.6 | -1.0 | -0.4 | -0.2 |

| NS | Employment rate (%) | 48.3 | 49.3 | 52.7 | 53.1 | 53.8 | 55.0 | 55.4 | 56.3 | 55.6 | 56.5 | 56.8 | 56.9 |

| NB | Growth (%) | -13.4 | -9.1 | -2.6 | -2.3 | -2.4 | -2.4 | -1.6 | -0.9 | -1.0 | -0.9 | -1.7 | -1.1 |

| NB | Employment rate (%) | 48.7 | 51.2 | 54.8 | 54.9 | 54.8 | 54.8 | 55.2 | 55.6 | 55.6 | 55.6 | 55.2 | 55.5 |

| QC | Growth (%) | -18.9 | -13.3 | -8.0 | -6.0 | -4.9 | -3.4 | -3.6 | -3.3 | -3.5 | -5.8 | -3.1 | -2.5 |

| QC | Employment rate (%) | 50.2 | 53.6 | 56.9 | 58.1 | 58.8 | 59.6 | 59.4 | 59.6 | 59.4 | 58.0 | 59.6 | 59.9 |

| ON | Growth (%) | -14.5 | -15.0 | -10.1 | -8.1 | -6.6 | -4.3 | -3.9 | -3.6 | -3.5 | -5.5 | -4.0 | -1.7 |

| ON | Employment rate (%) | 52.5 | 52.2 | 55.2 | 56.3 | 57.2 | 58.6 | 58.7 | 58.9 | 58.9 | 57.7 | 58.6 | 59.9 |

| MB | Growth (%) | -13.8 | -11.7 | -7.0 | -5.2 | -4.4 | -1.7 | -1.8 | -4.6 | -5.6 | -5.0 | -2.6 | -1.9 |

| MB | Employment rate (%) | 54.7 | 56.0 | 59.0 | 60.1 | 60.6 | 62.3 | 62.2 | 60.4 | 59.8 | 60.2 | 61.6 | 62.0 |

| SK | Growth (%) | -13.0 | -12.8 | -7.8 | -5.0 | -4.8 | -3.4 | -3.4 | -3.8 | -4.7 | -4.3 | -3.8 | -4.2 |

| SK | Employment rate (%) | 56.2 | 56.4 | 59.6 | 61.4 | 61.5 | 62.4 | 62.4 | 62.2 | 61.6 | 61.9 | 62.1 | 61.8 |

| AB | Growth (%) | -15.1 | -13.9 | -9.9 | -7.0 | -6.7 | -4.9 | -3.8 | -4.3 | -4.7 | -3.7 | -3.1 | -2.0 |

| AB | Employment rate (%) | 55.2 | 55.9 | 58.4 | 60.2 | 60.4 | 61.5 | 62.1 | 61.8 | 61.5 | 62.1 | 62.4 | 63.0 |

| BC | Growth (%) | -15.4 | -14.1 | -9.3 | -6.9 | -6.8 | -4.4 | -2.9 | -1.9 | -1.6 | -1.6 | -0.5 | 0.8 |

| BC | Employment rate (%) | 52.1 | 52.9 | 55.8 | 57.2 | 57.2 | 58.6 | 59.5 | 60.1 | 60.2 | 60.2 | 60.8 | 61.6 |

| YK* | Growth (%) | -1.3 | -4.9 | -5.3 | -5.8 | -5.8 | -6.6 | -4.9 | -2.7 | -3.1 | -4.0 | -4.0 | -2.7 |

| YK* | Employment rate (%) | 69.5 | 67.0 | 66.5 | 65.9 | 65.9 | 65.1 | 66.4 | 67.9 | 67.6 | 67.0 | 67.0 | 67.9 |

| NWT* | Growth (%) | -2.7 | -2.7 | -5.4 | -5.8 | -7.2 | -6.7 | -3.6 | -0.4 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 2.7 | 3.6 |

| NWT* | Employment rate (%) | 64.2 | 64.0 | 62.2 | 62.1 | 61.1 | 61.4 | 63.4 | 65.5 | 66.7 | 67.0 | 67.6 | 67.9 |

| NT* | Growth (%) | -8.6 | -14.1 | -14.1 | -7.8 | -5.5 | -4.7 | -3.9 | -3.9 | -4.7 | -5.5 | -4.7 | -4.7 |

| NT* | Employment rate (%) | 47.8 | 45.0 | 45.0 | 47.8 | 48.9 | 49.1 | 49.3 | 49.4 | 49.0 | 48.6 | 48.8 | 49.0 |