Chapter 2: Impact and effectiveness of Employment Insurance benefits (Part I of the Employment Insurance Act)

From: Employment and Social Development Canada

Official title: Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for fiscal year beginning April 1, 2020 and ending March 31, 2021: Chapter 2: Impacts and effectiveness of Employment Insurance benefits (Part I of the Employment Insurance Act)

In chapter 2

- List of abbreviations

- 2.0 Introduction

- 2.1 Employment Insurance benefits overview

- 2.2 Employment Insurance regular benefits

- 2.3 Employment Insurance support while on training

- 2.4 Employment Insurance fishing benefits

- 2.5 Employment Insurance Work-Sharing benefits

- 2.6 Employment Insurance special benefits

- 2.7 Employment Insurance financial information

List of abbreviations

This is the complete list of abbreviations for the Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2020 and ending March 31, 2021.

Abbreviations

- AD

- Appeal Division

- ADR

- Alternative Dispute Resolution

- ASETS

- Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy

- B/C Ratio

- Benefits-to-Contributions ratio

- BDM

- Benefits Delivery Modernization

- CAWS

- Client Access Workstation Services

- CCDA

- Canadian Council of Directors of Apprenticeship

- CCIS

- Corporate Client Information Service

- CEIC

- Canada Employment Insurance Commission

- CERB

- Canada Emergency Response Benefit

- CESB

- Canada Emergency Student Benefit

- CEWB

- Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy

- COLS

- Community Outreach and Liaison Service

- CPP

- Canada Pension Plan

- CRA

- Canada Revenue Agency

- CRB

- Canada Recovery Benefit

- CRCB

- Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit

- CRF

- Consolidated Revenue Fund

- CRSB

- Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit

- CSO

- Citizen Service Officer

- CX

- Client Experience

- EBSM

- Employment Benefits and Support Measures

- ECC

- Employer Contact Centre

- EI

- Employment Insurance

- EI ERB

- Employment Insurance Emergency Response Benefit

- EICS

- Employment Insurance Coverage Survey

- eROE

- Electronic Record of Employment

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- eSIN

- Electronic Social Insurance Number

- FY

- Fiscal Year

- G7

- Group of Seven

- GDP

- Gross Domestic Product

- GIS

- Guaranteed Income Supplements

- HCCS

- Hosted Contact Centre Solution

- IQF

- Individual Quality Feedback

- ISET

- Indigenous Skills and Employment Training

- IVR

- Interactive Voice Response

- LFS

- Labour Force Survey

- LMDA

- Labour Market Development Agreements

- LMI

- Labour Market Information

- LMP

- Labour Market Partnerships

- MIE

- Maximum Insurable Earnings

- MSCA

- My Service Canada Account

- NAICS

- North American Industry Classification System

- NESI

- National Essential Skills Initiative

- NIS

- National Investigative Services

- NOM

- National Operating Model

- OAS

- Old Age Security

- PAAR

- Payment Accuracy Review

- PPE

- Premium-paid eligible individuals

- PRAR

- Processing Accuracy Review

- PRP

- Premium Reduction Program

- PTs

- Provinces and Territories

- QPIP

- Quebec Parental Insurance Plan

- R&I

- Research and Innovation

- ROE

- Record of Employment

- RPA

- Robotics Process Automation

- SAT

- Secure Automated Transfer

- SCC

- Service Canada Centre

- SDP

- Service Delivery Partner

- SEPH

- Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours

- SIN

- Social Insurance Number

- SIR

- Social Insurance Registry

- SST

- Social Security Tribunal

- STDP

- Short-term disability plan

- SUB

- Supplemental Unemployment Benefit

- TRF

- Targeting, Referral and Feedback

- TTY

- Teletypewriter

- UV

- Unemployment-to-vacancy

- VBW

- Variable Best Weeks

- VER

- Variable Entrance Requirement

- VRI

- Video Remote Interpretation

- WCAG

- Web Content Accessibility Guidelines

- WWC

- Working While on Claim

2.0 Introduction

This chapter of the Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report assesses income support provided by Employment Insurance (EI) Part I benefits: regular benefits, fishing benefits, Work-Sharing benefits and special benefits. This chapter includes several key indicators, such as the number of new claims established, total amount paid, level of benefits, maximum duration and actual duration of benefits as well as the exhaustion of benefits. Throughout the chapter, key EI program provisions and recent changes made to the EI program are discussed. Indicators related to level of claims and level of benefits are presented for claims established within the fiscal year for which at least 1 dollar in EI benefits was paid. Indicators such as maximum and actual duration are based on claims completed during the fiscal year for which at least 1 dollar was paid in EI benefits. Indicators related to the amount of EI benefits paid are presented on a cash basis, which means the expenses are accounted for during the fiscal year in which they are paid. More information on the definitions of the indicators presented throughout this chapter can be found in annex 2.1 of this report.

This chapter covers the period beginning April 1, 2020, and ending March 31, 2021 (FY2021). This period was characterised by major economic and labour market disruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In response, the Government implemented the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) between March 15, 2020 and October 3, 2020Footnote 1 to provide income support to eligible employed and self-employed Canadians who stopped working and lost their income due to COVID-19. As a result, no new claims for EI regular or sickness benefits were establishedFootnote 2 during the weeks the CERB was in effect. However, claims for all other types of EI benefits could be established.

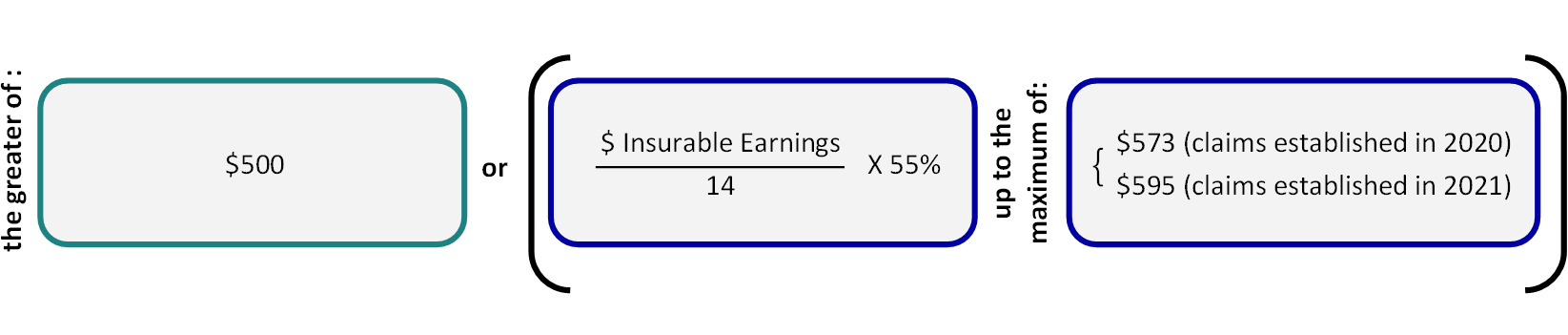

To continue supporting eligible workers, the Government transitioned from the CERB to a simplified EI program. Recognizing that many workers had lost their jobs or worked reduced hours, a set of temporary measures were introduced to facilitate access to EI benefits for all new claims established between September 27, 2020 and September 25, 2021. Table 1 lists the temporary measures and compares them to their associated original EI rules. The main temporary measures were:

- a 1-time hours credit to allow workers to qualify for EI benefits with 120 hours of insurable employment, applicable to the first EI claim

- a minimum benefit rate of $500 per week, or $300 per week for extended parental benefits

- a maximum of 50 weeks of regular benefitsFootnote 3, and

- a minimum unemployment rate of 13.1% applying to all EI economic regions across Canada

New EI claims established between September 27, 2020 and March 31, 2021 were subject to different rules and were provided a different level of income support than EI claims established prior to September 27, 2020 under the original EI rules. Consequently, some of the key indicators in this chapter are presented for 2 distinct periods:

- from April 1, 2020 to September 26, 2020, referred to as “the first half of FY2021”, during which the original EI rules applied and no new claims for EI regular or sickness benefits were established, and

- from September 27, 2020 to March 31, 2021, referred to as “the second half of FY2021”, during which new EI claims were established under the EI temporary measures

The results on amount of EI benefits paid, however, cover the full period of FY2021 (from April 1, 2020 to March 31, 2021). Year-over-year comparisons are not reported, unlike reports from previous years.

On September 27, 2020, the Government also implemented 3 temporary recovery benefits to provide income support to Canadian workers who were no longer employed or self-employed for reasons related to COVID-19. Those benefits were: the Canada Recovery Benefit (CRB), the Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit (CRSB), and the Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit (CRCB). These 3 recovery benefits applied to specific circumstances and could not be claimed at the same time as EI benefits. That said, the income support provided to Canadian workers through any of the CERB, CRB, CRSB and CRCB is not included in this chapter.

This chapter relies on several sources of information to provide a comprehensive analysis of the EI program. EI administrative data, generally based on a 10% sample, underpins the majority of the analysis. Some sections of this chapter also make use of tax data provided by the Canada Revenue Agency related to T4 tax slips with employment income or T1 returns. Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey, as well as Records of Employment, provide the basis for analysis of coverage, eligibility and access to EI benefits for unemployed people. Throughout the chapter, results by sociodemographic characteristics are discussed and compared to previous years.

Annex 2 of the report presents additional statistical information on benefits analyzed in this chapter and annex 7 provides an overview of major changes to the EI program between April 1996 and December 2021.

| Original EI rules for claims established prior to September 27, 2020 | EI temporary measures in effect for claims established between September 27, 2020 and September 25, 2021, or otherwise indicated |

|---|---|

| The EI program uses monthly regional unemployment rates that are a moving average of seasonally adjusted monthly rates of unemployment produced by Statistics Canada. | Same rule but a minimum unemployment rate of 13.1% was applied to all regions across Canada,1 resulting in:

|

| A minimum of 420 to 700 hours of insurable employment to qualify for EI regular benefits based on the regional unemployment rate. A minimum of 600 hours of insurable employment to qualify for EI special benefits. | 120 hours of insurable employment to qualify for regular and special benefits due to the 1-time credit of 300 hours for claims for regular benefits and 480 hours for claims for special benefits.2 |

| The benefit rate is calculated by averaging the 14 to 22 highest weeks of insurable earnings depending on the regional unemployment rate. | The benefit rate was calculated by averaging the 14 highest weeks of insurable earnings. A minimum benefit rate of $500 per week, or $300 per week for extended parental benefits, was applied if the claimant’s calculated rate was lower. |

| Between 14 and 45 weeks of regular benefits depending on the regional unemployment rate and the number of hours of insurable employment. | A maximum of 50 weeks of regular benefits.3 |

| A one-week waiting period must be served before a claimant can begin to receive EI benefits. | The one-week waiting period was waived for all EI claims established between January 31, 2021 and September 25, 2021.4 |

| The qualifying period is the shorter of the 52-week period immediately before the start date of an EI claim, or the period since the start of a previous claim. | The qualifying period was extended by 28 weeks if a claimant received CERB.5 |

| All reasons for separation from any employment within the qualifying period are considered in determining EI eligibility. | Only contentious reasons for separation in the 12 weeks before the Sunday where the claimant lost their job were assessed. |

| Separation monies are allocated against EI benefits. | Separation monies were not allocated against EI benefits. |

| Sickness benefit claimants must provide a medical certificate signed by a doctor or approved medical practitioner. | The need to submit a medical certificate for sickness benefits was waived between September 27, 2020 and September 25, 2021. |

| Work-Sharing agreements provide 6 to 26 weeks of benefits, with the possibility of an extension by 12 weeks if warranted. | Between March 15, 2020 and September 25, 2022, Work-Sharing agreements provided up to 76 weeks of benefits. |

| Between $2,500 and $4,200 insurable earnings threshold for fishers to qualify for fishing benefits depending on the regional unemployment rate. $3,760 insurable earnings threshold for fishers to qualify for special benefits. | $2,500 insurable earnings threshold for fishers to qualify for fishing or special benefits. The claim could be based on their earnings in their current qualifying period, or the earnings used to establish a fishing claim of the same type (summer or winter) from 1 of the 2 previous years, whichever amount was the highest. |

| The EI fishing benefit rate is calculated by using the earnings for the current claim. | The EI fishing benefit rate was calculated using either the earnings in the current qualifying period, or the earnings used to establish a fishing claim of the same type (summer or winter) from 1 of the 2 previous years, whichever was the highest. |

| In 2020, $7,279 earnings threshold (2019 earnings) for self-employed workers who opted-in EI to qualify for special benefits. | Between January 3, 2021 and September 25, 2021, $5,000 earnings threshold (2020 earnings) for self-employed workers who opted-in EI to qualify for special benefits. |

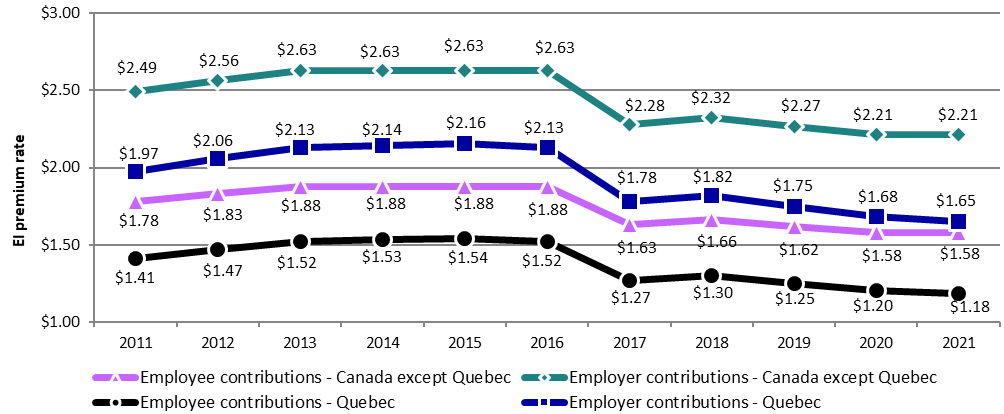

| The annual premium rate is set based on a 7-year break-even mechanism. | The EI premium rate was frozen at the 2020 premium rate for 2 years. |

- 1 Individuals in EI regions with an unemployment rate lower than 13.1% had their EI parameters calculated on the basis of the 13.1% rate, while those in regions with a higher rate had their parameters calculated using the actual higher rate. This temporary measure was supposed to end on September 11, 2021. The measure was extended to September 25, 2021 in Budget 2021.

- 2 The hours credit measure was retroactive to March 15, 2020 for CERB claimants who were looking to switch to EI special benefits (except sickness benefits) or Work-Sharing benefits during the first half of FY2021, but couldn’t because they did not have enough hours.

- 3 When the temporary measures started on September 27, 2020, claimants were entitled to receive between 26 and 45 weeks of regular benefits. This was increased to 50 weeks in March 2021 and was applied retroactively to all regular claims established since September 27, 2020.

- 4 The waiting period was also waived for all EI claims established between September 27, 2020 and October 25, 2020; and for new EI sickness claims established between September 27, 2020 and September 25, 2021.

- 5 The qualifying period was extended by 16 weeks for EI claims established before July 5, 2020 and by 24 weeks for claims established on or after July 5, 2020 for claimants who received CERB and needed to transition to special benefits (except sickness benefits) or Work-Sharing benefits during the first half of FY2021.

2.1 Employment Insurance benefits overview

In this section

- 2.1.1 Employment Insurance claims and amount paid

- 2.1.2 Combined Employment Insurance claims

- 2.1.3 Benefits-to-Contributions ratios

The Employment Insurance (EI) program provides temporary income support to partially replace employment income for eligible unemployed contributors to the program while they search for work or upgrade their skills, and for those who are absent from work due to specific life circumstances (such as sickness, pregnancy, providing care to a newborn or newly adopted child, providing care or support to a critically ill or injured person or someone needing end-of-life care).

In this chapter, EI benefits refer to regular benefits, special benefits, fishing benefits and Work-Sharing benefits (consult table 2). Special benefits include maternity benefits, parental benefits, sickness benefits, family caregiver benefits for adults or children, and compassionate care benefits. Subsection 2.1.1 covers the number of new claims established in the fiscal year and total amount paid over the fiscal year, and provides information on benefit levels of claims. Subsection 2.1.2 examines combined (or mixed) benefit claims. Subsection 2.1.3 provides an analysis of the usage of EI benefits relative to EI premiums contributed.

| Benefit type | Circumstance | Insurable employment entrance requirement (first half of FY2021) | Insurable employment entrance requirement (second half of FY20211) | Maximum entitlement in FY2021, or otherwise indicated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | Unemployed with a valid reason for separation and searching for suitable employment or retraining in certain cases | Not available due to the CERB | 120 hours due to the one-time credit of 300 hours | Claims established in the second half of FY2021: 50 weeks |

| Fishing | Self-employed fishers without available work | Value of a catch between $2,500 and $4,200 depending on the Variable Entrance Requirement | Value of a catch of $2,500 that can be based on the current qualifying period, or the earnings used to establish a fishing claim of the same type (summer or winter) from 1 of the 2 previous years, whichever is highest. | 26 weeks per season (summer or winter) |

| Work-Sharing | Firm avoiding layoffs during a slowdown in business activity for reasons beyond the firm’s control with a recovery plan and a Work-Sharing agreement in place | 420 to 700 hours depending on the Variable Entrance Requirement and must be a year-round employee | 120 hours due to the one-time credit of 300 hours | 76 weeks2 |

| Special3 - Maternity | Unavailable to work because of pregnancy or has recently given birth | 600 hours | 120 hours due to the one-time credit of 480 hours | 15 weeks |

| Special3 - Parental | Caring for a newborn or a newly adopted child | 600 hours | 120 hours due to the one-time credit of 480 hours | Standard parental: 40 weeks available to share, with no parent able to receive more than 35 weeks Extended parental (at a lower replacement rate): 69 weeks available to share, with no parent able to receive more than 61 weeks |

| Special3 - Sickness | Unavailable to work because of illness, injury or quarantine | Not available due to the CERB | 120 hours due to the one-time credit of 480 hours | 15 weeks |

| Special3 - Family caregiver for children | Providing care or support to a critically ill or injured child under the age of 18 | 600 hours | 120 hours due to the one-time credit of 480 hours | 35 weeks4 |

| Special3 - Family caregiver for adults | Providing care or support to a critically ill or injured person 18 years or older | 600 hours | 120 hours due to the one-time credit of 480 hours | 15 weeks4 |

| Special3 - Compassionate care | Providing care to a person of any age who requires end-of-life care | 600 hours | 120 hours due to the one-time credit of 480 hours | 26 weeks4 |

- 1 The hours credit measure was applicable to the first EI claim established between September 27, 2020 and September 25, 2021. It could be retroactive to March 15, 2020 for CERB claimants who were looking to switch to EI special benefits (except sickness benefits) or Work-Sharing benefits during the first half of FY2021, but couldn’t because they did not have enough hours.

- 2 Temporary Work-Sharing special measures between March 15, 2020 and September 24, 2022.

- 3 Self-employed workers (other than fishers) who have opted into EI special benefits must meet an insurable earnings threshold for the calendar year preceding the claim. The threshold was $7,279 for claims established in 2020 and temporarily set to $5,000 for claims established in 2021 (until September 25, 2021).

- 4 Benefits can be shared between eligible claimants (i.e. parents or family members).

2.1.1 Employment Insurance claims and amount paid

There were 3.0 million new EI claims established in FY2021 (consult table 3). This is substantially higher than usual as, on average, 1.8 million EI claims were established annually over the last 10 fiscal years. The larger number of claims in FY2021 is attributable to the economic and labour market disruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic and to the related EI temporary measures introduced during the reporting period (consult section 2.0). Total EI benefit payments were also significantly higher, reaching $32.1 billion during FY2021.

| Types of Employment Insurance benefit | New claims established FY1920 | New claims established first half of FY2021 | New claims established second half of FY2021 | New claims established total FY2021 | Amount paid ($ millions) FY1920 | Amount paid ($ millions) FY2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | 1,367,080 | n/a | 2,472,860 | 2,472,860 | $11,064.4 | $24,930.1 |

| Fishing | 30,385 | 10,923 | 17,365 | 28,288 | $303.1 | $323.6 |

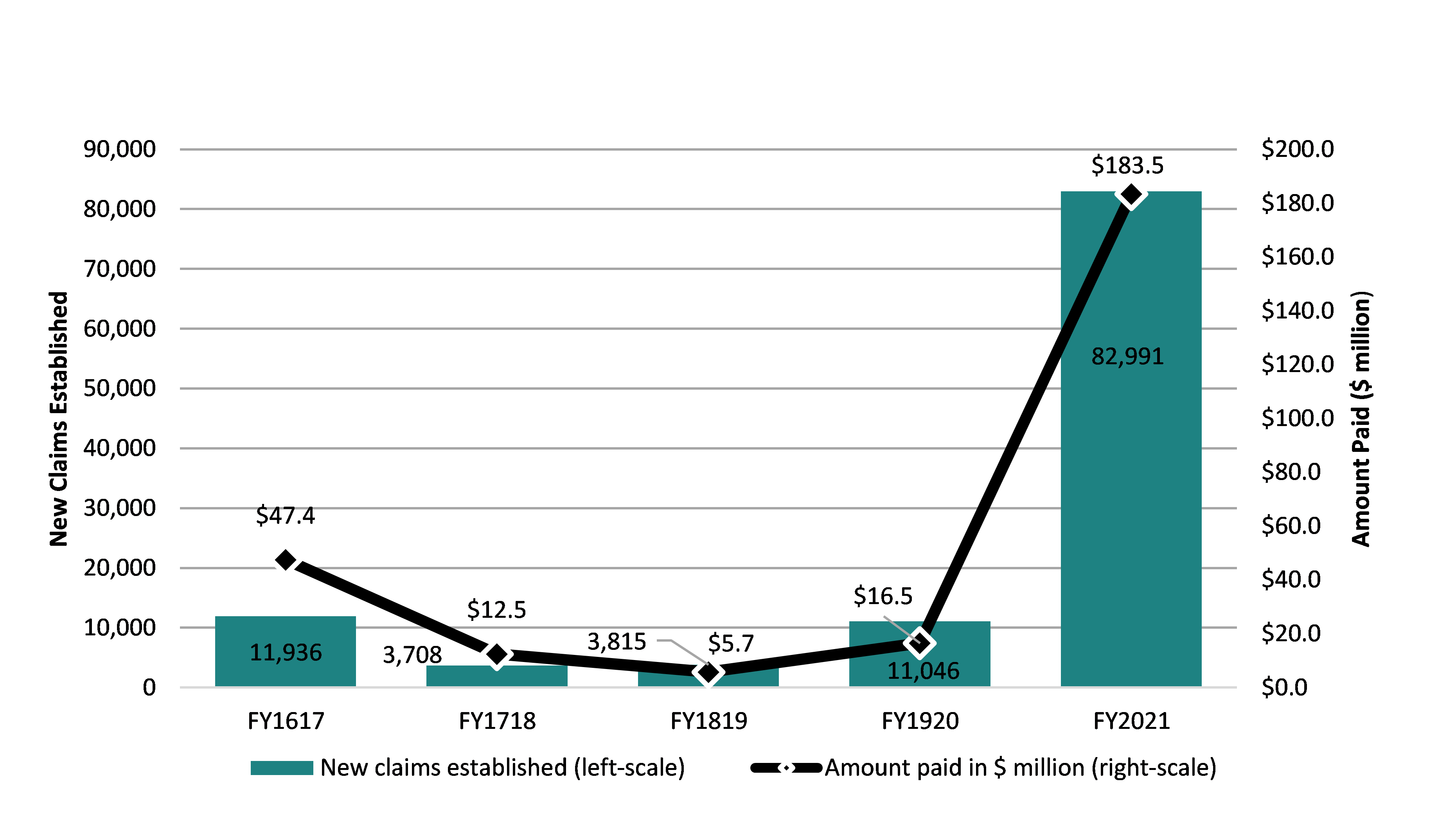

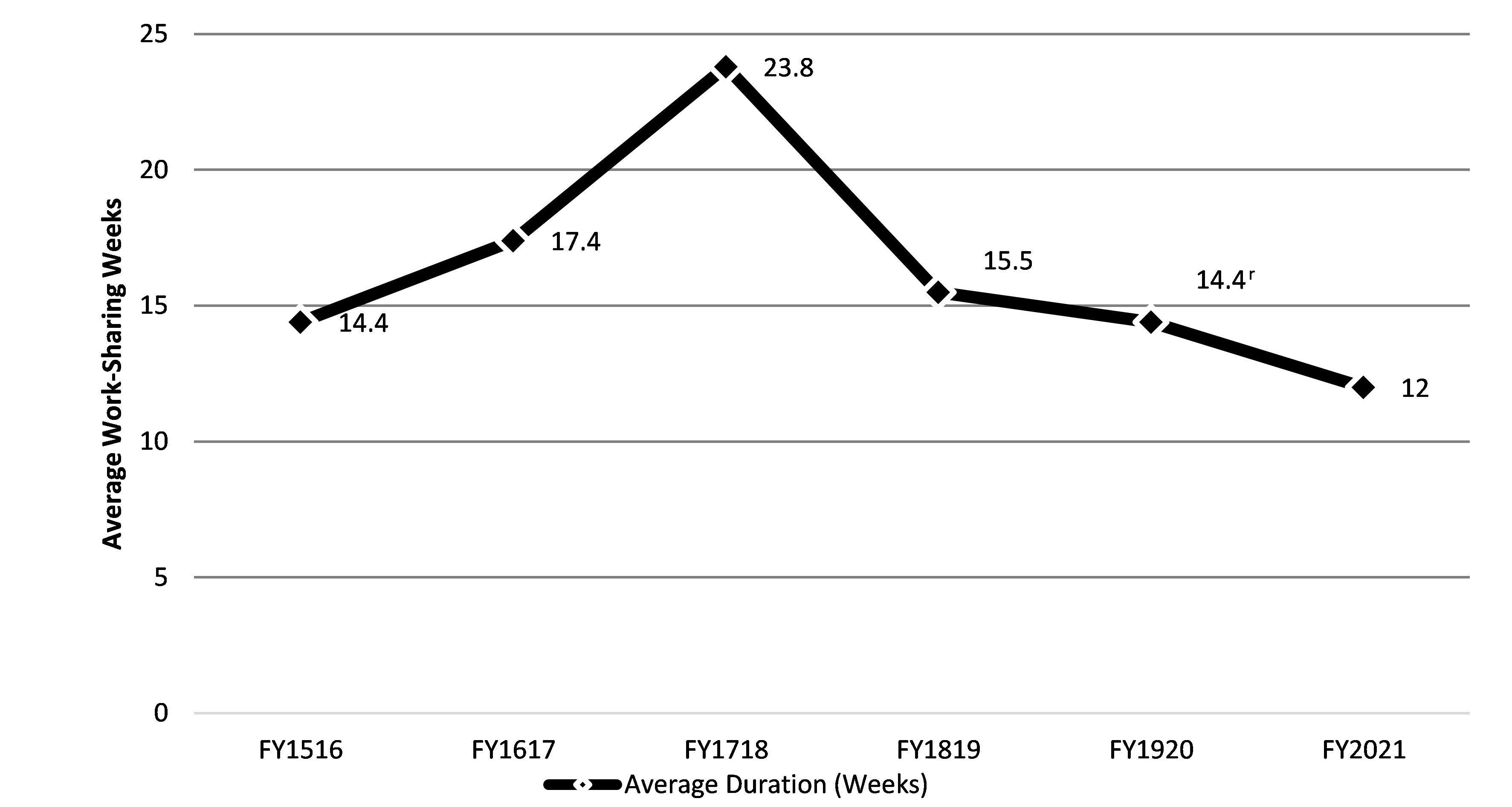

| Work-Sharing | 11,046 | 65,608 | 17,383 | 82,991 | $16.5 | $183.5 |

| Special* | 619,270 | 112,860 | 558,400 | 671,260 | $6,150.1 | $6,655.7 |

| Maternity | 167,690 | 74,330 | 92,580 | 166,910 | $1,208.1 | $1,324.7 |

| Parental | 212,750 | 97,960 | 115,140 | 213,100 | $2,921.7 | $3,177.8 |

| Sickness | 421,140 | n/a | 450,350 | 450,350 | $1,888.8 | $1,999.3 |

| Family caregiver for children | 5,403 | 2,272 | 3,250 | 5,522 | $36.3 | $41.2 |

| Family caregiver for adults | 11,592 | 4,190 | 8,018 | 12,208 | $55.7 | $69.3 |

| Compassionate care | 7,581 | 2,518 | 4,284 | 6,802 | $39.6 | $43.4 |

| Canada | 1,874,480 | 185,630 | 2,863,060 | 3,048,690 | $17,502.7 | $32,075.0 |

- Notes: Totals may not add up due to rounding. Includes all claims for which at least $1 of Employment Insurance benefits was paid. The sum of claims by benefit type does not add up as multiple benefit types can be combined in 1 single claim.

- * Starting in FY2021, data on family caregiver benefits are included in the total number of special benefit claims, which could affect comparisons with previous years. They were previously excluded due to the incompatibility of administrative data sources.

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a sample of 10% of the EI administrative data, except for family caregiver, Work-Sharing and compassionate care benefits as well as claims for fishing benefits (100%).

According to Statistics Canada,Footnote 4 there were 588,600 beneficiaries receiving EI benefits on average each month during the first half of FY2021. This number was higher than the amount of new EI claims established during that period (consult table 3). This is because some claims that were established in the previous fiscal year still received EI benefits in FY2021. The number increased to 1.8 million beneficiaries on average each month over the second half of FY2021 when regular and sickness benefits resumed.

New Employment Insurance claims established

The high number of new EI claims observed during the reporting period is largely due to claims for regular benefits established in the second half of FY2021. The share of regular claims among all new claims established increased from 72.9% in FY1920 to 81.1% in FY2021. Conversely, the share of claims for sickness benefits ─ which are the second most common benefit type claimed ─ decreased from 22.5% to 14.8% during the same period.

All provinces and territories experienced a higher number of new EI claims in FY2021 compared to the previous fiscal year (consult table 4). The distribution of new claims among regions also remained fairly stable, except for Ontario. The share of claims established in this province increased by 3.8 percentage points, from 31.2% in FY1920 to 35.0% in FY2021.

| Category | New claims established FY1920 | New claims established first half of FY2021 | New claims established second half of FY2021 | New claims established total FY2021 | Amount paid ($ millions) FY1920 | Amount paid ($ millions) FY2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 81,790 | 6,450 | 93,660 | 100,110 | $992.5 | $1,274.8 |

| Prince Edward Island | 21,770 | 1,700 | 23,490 | 25,190 | $226.0 | $293.8 |

| Nova Scotia | 82,540 | 7,530 | 95,530 | 103,060 | $851.3 | $1,187.6 |

| New Brunswick | 89,380 | 4,800 | 105,870 | 110,670 | $925.1 | $1,248.4 |

| Quebec | 475,220 | 17,760 | 731,550 | 749,310 | $3,210.3 | $6,547.8 |

| Ontario | 585,670 | 78,180 | 989,710 | 1,067,890 | $5,680.5 | $11,347.0 |

| Manitoba | 64,780 | 10,700 | 91,410 | 102,110 | $631.2 | $1,082.2 |

| Saskatchewan | 57,280 | 6,160 | 71,340 | 77,500 | $639.3 | $952.5 |

| Alberta | 200,450 | 25,900 | 338,520 | 364,420 | $2,266.4 | $4,304.4 |

| British Columbia | 210,060 | 25,620 | 314,770 | 340,390 | $2,004.3 | $3,734.2 |

| Yukon | 2,300 | 260 | 2,950 | 3,210 | $26.0 | $39.5 |

| Northwest Territories | 2,030 | 270 | 2,590 | 2,860 | $29.7 | $37.0 |

| Nunavut | 1,210 | 300 | 1,670 | 1,970 | $20.0 | $25.7 |

| Male | 1,018,710 | 78,350 | 1,527,190 | 1,605,540 | $8,833.7 | $16,252.2 |

| Female | 855,770 | 107,280 | 1,335,870 | 1,443,150 | $8,669.0 | $15,822.8 |

| 24 years old and under | 171,760 | 9,280 | 431,680 | 440,960 | $1,302.6 | $3,601.1 |

| 25 to 44 years old | 914,700 | 129,980 | 1,252,340 | 1,382,320 | $9,554.9 | $15,819.2 |

| 45 to 54 years old | 352,040 | 23,750 | 500,800 | 524,550 | $2,915.8 | $5,272.4 |

| 55 years old and over | 435,980 | 22,620 | 678,240 | 700,860 | $3,729.3 | $7,382.4 |

| Canada | 1,874,480 | 185,630 | 2,863,060 | 3,048,690 | $17,502.7 | $32,075.0 |

- Notes: Totals may not add up to the total due to rounding. Includes claims for which at least $1 of EI benefits was paid.

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a sample of 10% of the EI administrative data.

Men continued to account for just over half (52.7%) of all new claims in FY2021. However, during the first half of the reporting period, their share of all claims established drop to 42.2% because no new claims for regular or sickness benefits could be established at that time, and men are less likely to claim parental benefits and cannot receive maternity benefits.

All age groups registered a higher number of new EI claims in FY2021 compared to FY1920. The share of claims established by claimants 25 to 54 years old declined, while it remained unchanged for claimants 55 years old and over. The number of new EI claims more than doubled for claimants 24 years old and under in FY2021 compared to the previous fiscal year. Younger claimants established only 9.2% of the total number of claims in FY1920, whereas they established 14.5% of all claims in FY2021. This can be attributable, in part, to the EI temporary measure allowing claimants to qualify for benefits with as little as 120 hours of insurable employment (consult section 2.0).

Early impact of COVID-19 on Employment Insurance benefits and the Canadian labour market

At the beginning of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing health measures including provincial lockdowns led to an unprecedented number of Canadian workers that either suffered a job loss or experienced a reduction in their number of hours worked. The Government introduced the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) to provide support to workers who had stopped working due to the pandemic.

A recent departmental study* analyzed different sources of EI administrative data** to examine patterns of job separations, EI applications and EI claims established in the weeks leading up to the coming into force of the CERB on March 15, 2020. The study compared the data in the weeks before CERB to the same period in 2019 to examine the early impact of COVID-19 on the EI program. This comparison using EI administrative data yielded a wealth of information about changes in the labour market.

A significant increase in job separations was observed in the 5-week period before CERB when compared to the same period in 2019 (+14.5% or about 100,000 more job separations). The majority of this increase was for job separations due to shortage of work (layoff), and illness or injury. Inversely, job separations related to quit or dismissal decreased.

The study found that individuals who were laid-off during this 5-week period were significantly different compared to those laid-off during the same period in 2019. In general, they worked fewer weekly hours and had lower employment income. When examining the factors associated with the probability of having a job separation in 2020 compared to 2019 (using a regression analysis), the study found that the industry sector of previous work was a more important predictor of having a job separation than employment income. Workers in the Art, entertainment and recreation sector, and those from the Accommodation and food services sector experienced the highest increase in the probability of having a job separation. In addition, the probability of having a job separation in 2020 compared to 2019 was higher in British Columbia and Alberta. This seemed to be related to job separations in the Educational services sector, probably due to the timing of winter school breaks in these regions.

In terms of EI applications, data showed a significant increase in volume but only in the week before the coming into force of CERB.

Analysis on the number of EI claims established for regular or sickness benefits showed an increase in the 6-week period before CERB when compared to the same period in 2019. However, this increase was lower than the one in job separations, which might indicate that a portion of laid-off workers were not eligible for EI benefits. In addition, while the study found some differences in the characteristics of laid-off workers between 2019 and 2020 (such as, lower employment income), there was no such difference for EI claimants (such as, similar distribution of employment income between 2019 and 2020).

- * ESDC, Early impact of COVID-19 on Employment Insurance benefits and the Canadian Labour Market (Ottawa: ESDC, Evaluation Directorate, 2022).

- ** Datafile on Records of Employment (ROEs) for job separations, Status Vector file for EI claims established, and Appliweb for EI applications.

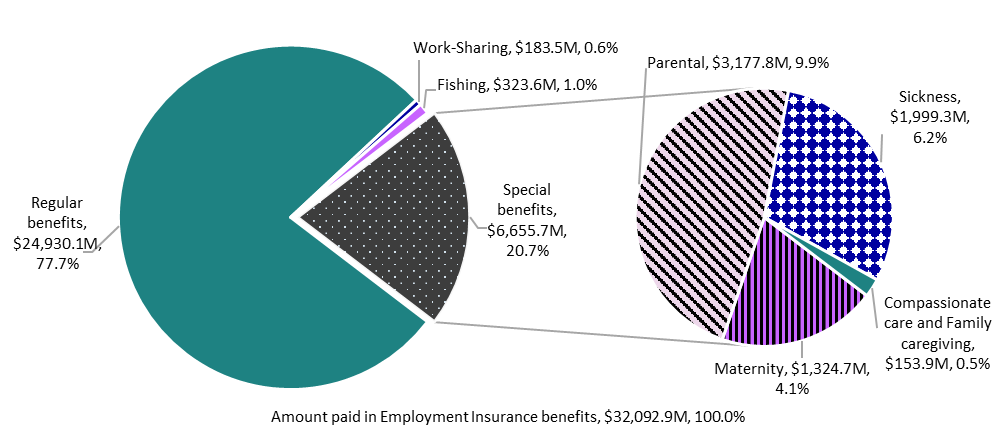

Total amount paid in Employment Insurance benefits

The amount paid for all types of EI benefits combined reached $32.1 billion in FY2021 compared to $17.5 billion in FY1920. This increase was mainly attributable to the high number of EI regular claims established in the second half of FY2021 and to the EI temporary measures generally providing a higher weekly benefit rate to claimants relative to the original EI rules (consult section 2.0 and the box on the initial impacts of temporary EI measures in Canadian communities during the pandemic). The share of EI benefits paid by benefit type also changed compared to the previous reporting period. The shares of regular and Work-Sharing benefits increased (+14.6 and +0.5 percentage points, respectively), whereas the shares of special benefits and fishing benefits decreased in FY2021 (‑14.3 and ‑0.7 percentage points, respectively).

Text description of Chart 1

| Benefit type | $ million | % share |

|---|---|---|

| Regular benefits | $24,930.1 | 77.7% |

| Work-Sharing benefits | $183.5 | 0.6% |

| Fishing benefits | $323.6 | 1.0% |

| Special benefits | $6,655.7 | 20.7% |

| Parental benefits | $3,177.8 | 9.9% |

| Sickness benefits | $1,999.3 | 6.2% |

| Maternity benefits | $1,324.7 | 4.1% |

| Compassionate care and Family caregiving benefits | $153.9 | 0.5% |

| Amount paid in Employment Insurance benefits | $32,092.9 | 100.0% |

- * The total amount paid reported in chart 1 does not correspond to the total reported in Tables 3 and 4 because data on compassionate care benefits and family caregiver benefits can only be reported on a 100% sampling basis on an aggregate level.

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a sample of 10% of the EI administrative data, except for Work-Sharing, family caregiver and compassionate care benefits (100%).

Claimants in Ontario and Quebec received higher shares of the amount paid in EI benefits in FY2021 compared to the previous fiscal year (+2.9 and +2.1 percentage points, respectively). As observed with the number of new claims, claimants 24 years old and under also saw their share of EI benefits paid increase by 3.8 percentage points, from 7.4% in FY1920 to 11.2% in FY2021.

Initial impacts of temporary Employment Insurance measures in Canadian communities during the pandemic

As presented in section 2.0, a set of EI temporary measures were introduced to facilitate access to EI benefits for all new claims established between September 27, 2020 and September 25, 2021. A recent departmental study* examined the initial impacts of the additional income support provided by the main temporary measures compared to what would have been provided under the original EI rules. The study covered the period from September 27, 2020 to April 3, 2021, which is virtually identical to the second half of FY2021. Since the EI temporary measures were in effect until September 25, 2021, the study did not cover the entire period of the measures.

Some temporary measures allowed claimants to qualify for benefits with only 120 hours of insurable employment. Among claims established during the study period, 13.2% of regular claims (about 326,000) and 7.6% of special benefit claims (about 37,000) benefitted from these measures. Those claimants would not have been able to qualify for EI benefits if the original eligibility requirements had been in place.

As part of the temporary measures, claimants could receive an increased benefit rate in 1 of 2 ways; either from a minimum $500 weekly benefit rate or, because the benefit rate was calculated based on their best 14 weeks of earnings. Among claims established during the study period, 65.6% of regular claims and 57.2% of special benefit claims had a higher weekly benefit rate than what they would have been entitled to without the temporary measures.

Among claimants who benefitted from the minimum weekly benefit rate of $500,** they received, on average, an additional $199 per week for regular claims and $167 per week for special benefit claims.*** Among claims with a weekly benefit rate above $500 and that benefitted from a higher benefit rate, claimants received, on average, an additional $56 per week for regular claims and $34 per week for special benefit claims.

Up to 50 weeks of regular benefits were available to eligible claimants under the temporary measures. All regular claims could potentially benefit from additional weeks (19 more weeks on average) compared to their original maximum entitlement. However, only a small proportion of claims (16.5%) had benefitted from additional weeks at the end of the study period. This is because most of the claimants had not exhausted their original entitlement at that time, and consequently, they had not started using the additional weeks of regular benefits offered to them.

The study also estimated the additional cost generated by the main EI temporary measures between September 27, 2020 and April 3, 2021. The additional cost represents the amount of EI benefits that would not have been paid if the temporary measures had not been implemented. Overall, around $6.1 billion was paid in additional income support through the EI temporary measures over the study period. The largest share is associated with the minimum $500 weekly benefit rate ($4.6 billion over the study period).

- * ESDC, Initial impacts of temporary Employment Insurance measures in Canadian communities during the pandemic (Ottawa: ESDC, Employment Insurance Policy Directorate, 2022).

- ** Minimum $300 weekly benefit rate for extended parental benefits.

- *** The additional weekly benefit rate for claims of extended parental benefits is calculated using the 55% replacement rate in order to reflect the cost on the same scale than other EI benefit types.

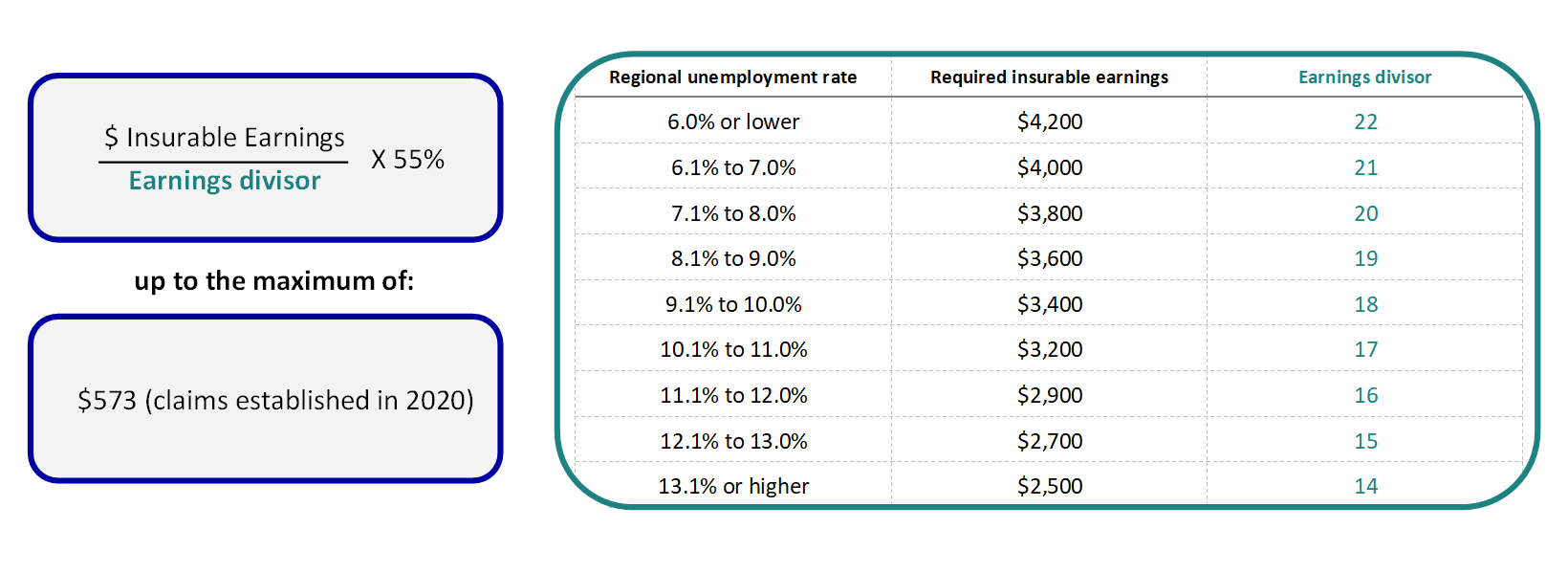

Calculation of the benefit rate

The weekly benefit rate to which EI claimants are entitled is typically subject to the Variable Best Weeks (VBW) provision. Under this provision, the weekly benefit rate is calculated based on an EI claimant’s highest (best) weeks of insurable earnings during their qualifying period. The number of weeks used to calculate the weekly benefit rate ranges from 14 to 22, depending on the monthly regional unemployment rate.

| Unemployment rate* | Number of weeks |

|---|---|

| 6.0% and under | 22 |

| 6.1% to 7.0% | 21 |

| 7.1% to 8.0% | 20 |

| 8.1% to 9.0% | 19 |

| 9.1% to 10.0% | 18 |

| 10.1% to 11.0% | 17 |

| 11.1% to 12.0% | 16 |

| 12.1% to 13.0% | 15 |

| More than 13.0% | 14 |

- *The monthly regional unemployment rates used for the EI program are a moving average of seasonally adjusted rates of unemployment produced by Statistics Canada, as per section 17 of the Employment Insurance Regulations.

The weekly benefit rate is paid as 55%Footnote 5 of the average weekly insurable earnings, up to the maximum weekly benefit rate.Footnote 6 Claimants with children (under the age of 18 years) and low annual family income may be eligible for the Family Supplement provision.Footnote 7

However, the COVID-19 pandemic may have had a negative impact on a worker’s weekly earnings either because they lost their job or saw their hours of work reduced. Therefore, as part of the EI temporary measures (consult section 2.0), the Government introduced a minimum benefit rate for new EI claims established between September 27, 2020 and September 25, 2021. Claimants could receive a minimum benefit rate of $500 per week, or $300 per week for extended parental benefits, less applicable taxes, up to the maximum weekly benefit rate.

In addition, the Government applied a minimum unemployment rate of 13.1% to all EI economic regions across Canada until September 25, 2021. As a result, the number of best weeks of earnings used in the calculation of the weekly benefit rate was 14 for all claims established between September 27, 2020 and September 25, 2021. If a claimant’s benefit rate based on this calculation was higher than the minimum $500, their benefit rate was set to that amount up to the maximum weekly benefit rate.

Consequently, the weekly benefit rate calculation was different depending on when a claim was established during FY2021. New EI claims established during the first half of FY2021 were subject to the Variable Best Weeks provision, whereas new EI claims established during the second half of FY2021 benefitted from the temporary measures.

Results on average weekly benefit rates by benefit type and by FY2021’s first or second half are presented throughout the chapter in their respective section.

Family Supplement provision

The Family Supplement provision, which targets low-income families, provides additional benefits to EI claimants with children under the age of 18 who have an annual family net income equal to or less than $25,921. The claimant must also receive the Canada Child Benefit. Under the Family Supplement provision, which is available to claims in all benefit types, the weekly amount of family supplement can increase a claimant’s benefit rate from 55% to a maximum of 80% of his or her weekly insurable earnings, up to the maximum weekly benefit rate. The supplement provided to eligible claimants is determined by the claimant’s family net income, the number of children in the claimant’s family, and the age of the claimant’s children.Footnote 8

In FY2021, low-income families received a total of $108.6 million in additional benefits through the Family Supplement provision. A total of 95,070 claims received the family supplement in FY2021, which represents 3.1% of all claims established during the reporting period, compared to 3.5% in FY1920. The proportion of EI claims receiving the family supplement has now decreased for the past 20 years, from a high of 10.7% of all claims in FY0001. This decrease can be explained by the fact that the eligibility threshold has not been indexed over time, as well as by changes in family composition and wage growth. Women (83.2%) and claimants aged 25 to 44 (72.8%) continue to be the main demographic groups benefitting from the Family Supplement provision. The average weekly family supplement was $39 in FY2021 which is slightly lower than the previous year ($45) mainly due to the EI temporary measures generally providing a higher weekly benefit rate to claimants relative to the original EI rules (consult annex 2.22 for more statistics on the Family Supplement provision).

Supplemental Unemployment Benefit plans

While the temporary support from EI benefits provide an income floor for claimants, employers can use a Supplemental Unemployment Benefit (SUB) plan to increase their employees’ weekly earnings when they are unemployed due to a temporary stoppage of work, training, illness, injury or quarantine.Footnote 9 These SUB plans need to be registered with Service Canada so that supplemental payments (or top-ups) are not considered as earnings and are not deducted from EI benefits. The combined weekly payments from the plan and EI weekly benefits cannot exceed 95% of the employee’s normal weekly earnings.

Employers can also provide supplemental payments to maternity, parental (including adoption), compassionate care and family caregiver benefits.Footnote 10 These plans do not have to be registered with Service Canada. The top-up amounts are not deducted from EI benefits if the combined weekly payments do not exceed 100% of the employee’s normal weekly earnings and the plan does not use the supplemental payments to reduce other accumulated employment benefits (such as banked sick leave, vacation leave credits or severance pay).

Results on average weekly benefit rates presented in this chapter do not include any supplemental payments made to EI claimants.

Study on Supplemental Unemployment Benefit plans

A departmental study* examined the characteristics of employers and employees with SUB plans**, and their utilization pattern of the EI program. From 2008 to 2017, an annual average of over 6,800 firms (0.5% of all firms in Canada) had active SUB plans, increasing over time. Around 63% of these plans were for illness, injury or quarantine, while plans for temporary stoppage of work, training and plans consisting of a combination of top-up plans accounted for around 10%, 7% and 20% respectively. Firms offering SUB plans were generally larger in size and more likely to be associated with the services industries.

Overall, EI claims that receive top-up payments through SUB plans constituted between 40,000 and 60,000 claims per year (around 3% of all EI claims). Most of these claims were for EI regular benefits, followed by claims for EI sickness benefits.

When firms offering SUB plans are compared with firms having similar characteristics but that do not offer SUB plans, results showed that the average number of EI claims and number of claims per worker were higher for firms offering SUB plans. However, EI claimants from firms offering SUB plans had shorter duration of EI benefits and lower EI exhaustion rates.

One of the main rationales behind a firm offering a SUB plan to their employees is to maintain the employee-employer relationship and facilitate employee retention. When comparing regular benefit claimants who previously worked in firms offering SUB plans, those who received SUB top-ups were more likely to return to the same firm after a claim compare to those who did not receive top-ups.***

- * ESDC, Supplemental Unemployment Benefit Plans (Ottawa: ESDC, Evaluation Directorate, 2021).

- ** Excluding SUB plans for maternity, parental (including adoption), compassionate care, and family caregiver benefits.

- *** The study found that among all EI claimants within SUB firms, only 13% received a top-up payment over the period examined. This suggests that not all employees in a given firm are entitled to SUB payments.

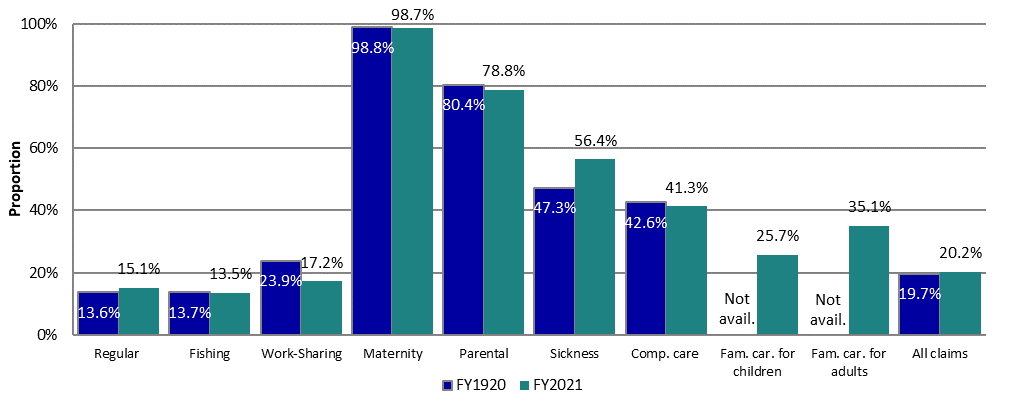

2.1.2 Combined Employment Insurance claims

Under certain provisions of the EI program, a claimant may receive multiple types of benefits as part of a single claim, assuming that the claimant meets each benefit type’s eligibility requirements.Footnote 11 A “pure” claim is one in which an EI claimant receives a single benefit type, while a “combined” claim is one in which the claimant receives more than 1 benefit type. The combination of EI benefit types in a single claim is examined using claims completed in FY2021, regardless of the year in which the claim was established. Pure claims represented 79.8% of all completed claims in FY2021 (consult table 5).

| Benefit type | Total claims level ('000s) | Pure claims level ('000s) | Pure claims share (%) | Combined claims level ('000s) | Combined claims share (%) | Benefit type most often combined with (share of combined claims) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | 1,470.7 | 1,248.2 | 84.9% | 222.5 | 15.1% | Sickness (89.9%) |

| Fishing | 30.3 | 26.2 | 86.5% | 4.1 | 13.5% | Sickness (90.0%) |

| Work-Sharing | 49.7 | 41.1 | 82.8% | 8.5 | 17.2% | Regular (75.5%) |

| Maternity | 172.0 | 2.2 | 1.3% | 169.8 | 98.7% | Parental (98.7%) |

| Parental* | 225.1 | 47.6 | 21.2% | 177.5 | 78.8% | Maternity (94.4%) |

| Sickness | 414.9 | 180.9 | 43.6% | 234.0 | 56.4% | Regular (85.5%) |

| Compassionate care | 7.4 | 4.3 | 58.7% | 3.0 | 41.3% | Sickness (59.2%) |

| Family caregiver for children** | 4.1 | 3.1 | 74.3% | 1.1 | 25.7% | Regular (56.6%) |

| Family caregiver for adults** | 11.4 | 7.4 | 64.9% | 4.0 | 35.1% | Regular (74.1%) |

| All claims*** | 1,957.1 | 1,561.0 | 79.8% | 396.1 | 20.2% | n/a |

- Note: Data may not add up to the total due to rounding. Includes completed claims for which at least $1 of EI benefits was paid. The sum of claims by benefit type for the “Total claims” and “Combined claims” columns does not add up to the total because more than 1 benefit type can be part of the same claim. This does not apply to pure claims that include only 1 benefit type.

- *Parental benefits include benefits for biological parents and adoptive parents.

- ** Starting in FY2021, data on family caregiver benefits are included in the analysis on combined claims. They were previously excluded due to the incompatibility of administrative data sources.

- *** The total number of claims is based on claims completed during the fiscal year. This explains why the total number of claims here is different from the total numbers of claims in Tables 3 and 4 which are based on established claims.

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data.

Women were more likely to claim more than 1 type of EI benefit (31.6%) than men (11.7%), mostly due to their high probability of claiming both maternity and parental benefits.

In fact, maternity benefits were the benefits most often combined with other types of benefits, usually parental benefits. However, a significant proportion also claimed sickness benefits with maternity benefits (15.3%), resulting in the claimant starting her leave before becoming eligible for maternity benefits (available 12 weeks prior to the child’s expected date of birth). The combination of sickness, maternity and parental benefits was the most common among claims with 3 or more benefit types (24,970 claims representing 14.5% of completed claims for maternity benefits in FY2021).

Claims for parental benefits were combined at a slightly lower rate than maternity, as only 16.5% of men who claimed parental also received another benefit payment. Of those male claimants, 86.7% received regular benefits and 16.9% claimed sickness benefits. Among women, virtually all (99.4%) who combined parental benefits with other types of benefits combined them with maternity benefits.

Sickness benefits were the third most likely to be combined with other benefit types, mostly with regular benefits. Men combined their sickness benefits predominantly with regular benefits (95.2%), while sickness claims from women were most often combined with regular (75.7%), maternity (22.2%) and parental benefits (21.4%). Sickness also represented the greatest share of combined regular claims.

When combined, compassionate care benefits are shared with sickness benefits (59.2%) or regular benefits (58.9%). Men tended to combine compassionate care benefits with regular benefits (68.4%) more often than women (54.5%). Women were most likely to combine compassionate care benefits with sickness benefits (62.2%) compared to men (52.6%).

Similarly to compassionate care benefits, family caregiver benefits for children were most often combined with regular benefits by men (84.6%), while women were more likely to combine them with sickness benefits (70.1%). Conversely, when family caregiver benefits for adults were combined, both men and women most often received them with regular benefits (84.2% and 68.3%, respectively).

Less than one-fifth of all Work-Sharing claims were combined with other benefit types (17.2%), predominantly regular benefits. This is attributable to the fact that both benefit types are typically used during a downturn in business activity, which increases the risk of layoffs (Work-Sharing benefits) and actual layoffs (regular benefits). Regular benefits are usually claimed following Work-Sharing benefits, reflecting a continued downturn in a participating firm’s activity that eventually leads to a downsizing of the firm’s labour force.

While it is possible for fishers to combine fishing benefits with other benefit types (under some restrictions), only 13.5% of fishing claims were combined claims. Of those claims, 90.0% were combined with sickness benefits. No fishing claims were shared with maternity, parental, compassionate care or Work-Sharing benefits during the reporting period.

Trends in combined claims are relatively stable over time. However, in FY2021, the proportion of claims combining sickness benefits with other benefit types increased compared to the previous fiscal year, whereas the proportion of claims receiving Work-Sharing benefits with other benefit types decreased (consult chart 2). The fact that no pure EI sickness claims could be established during the first half of FY2021 could explain that there were less pure sickness claims among all sickness claims completed in FY2021. In terms of Work-Sharing benefits, the labour market and economic conditions which improved throughout the reporting period could, in part, explain that firms using Work-Sharing were less likely to lay employees off compared to previous years. Therefore, a lower proportion of completed Work-Sharing claims were combined with other benefit types (generally regular benefits) in FY2021.

Text description of Chart 2

| Benefit type | FY1920 | FY2021 |

|---|---|---|

| Regular | 13.6% | 15.1% |

| Fishing | 13.7% | 13.5% |

| Work-Sharing | 23.9% | 17.2% |

| Maternity | 98.8% | 98.7% |

| Parental | 80.4% | 78.8% |

| Sickness | 47.3% | 56.4% |

| Compassionate care | 42.6% | 41.3% |

| Family caregiver for children | not available | 25.7% |

| Family caregiver for adults | not available | 35.1% |

| All claims | 19.7% | 20.2% |

- Note: Includes completed claims for which at least $1 of EI benefits was paid.

- * Starting in FY2021, data on family caregiver benefits are included in the analysis on combined claims. They were previously excluded due to the incompatibility of administrative data sources.

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data.

2.1.3 Benefits-to-contributions ratios

The EI benefits paid to eligible claimants are financed solely by the mandatory contributions (that is, EI premiums) made by employers and employees, and by the self-employed who have opted into the EI program. The amount of EI benefits paid relative to the contributions made provides valuable insights into the usage of the program, especially when the claimants are analyzed by their socio-demographic characteristics. This subsection examines this using 2 different ratios: the total benefits-to-contributions ratio (total B/C ratio) and the regular benefits-to-contributions ratio (regular B/C ratio) for 2019.Footnote 12 As EI contributions are not assigned to specific benefit types, the regular B/C ratio accounts for reductions in EI contributions related to special benefits.Footnote 13

The total B/C ratios and the regular B/C ratios presented below are normalized, with the ratio for Canada set at 1.0. Consequently, the adjusted total and regular B/C ratios provide a quick interpretation of the net usage of the EI program by socio-demographic characteristic relative to the national level. An adjusted ratio higher than 1.0 means that the underlying sub-population (such as region or industry) received comparatively more benefits than contributions made than the Canadian average, and thus is a net beneficiary of the EI program. On the other hand, an adjusted ratio less than 1.0 means that the representing sub-population received comparatively less benefits than contributions made relative to the national level, and is a net contributor.

In 2019, the Atlantic provinces and Saskatchewan had adjusted total B/C ratios above the national level, meaning claimants in these provinces received comparatively more in EI benefits than the contributions made (consult chart 3). Generally, regionsFootnote 14 with a larger share of seasonal claimants exhibit adjusted total B/C ratios that are above 1.0, highlighting the greater use of EI benefits by claimants in these regions compared with other regions. On the other hand, Ontario, British Columbia and Nunavut had adjusted total B/C ratios below the national average, as claimants in these regions received comparatively less in EI benefits than the contributions made to the EI program. Quebec, Manitoba, Alberta, Yukon and the Northwest Territories had ratios very close to the national level.

A similar pattern can be observed when the payments for EI special benefits are excluded. In 2019, the Atlantic provinces, Quebec and Saskatchewan had adjusted regular B/C ratios above the national average; while Ontario, British Columbia and Nunavut had ratios below the national average. Manitoba, Alberta, Yukon and the Northwest Territories had ratios very close to the national level.

Text description of Chart 3

| Province or territory | Adjusted total benefits-to-contributions ratio (left scale) | Adjusted regular benefits-to-contributions ratio (left scale) | Adjusted total benefits-to-contributions ratio for Canada (1.0) (left scale) | Unemployment rate (right scale) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 4.22 | 5.65 | 1.0 | 12.3 |

| Prince Edward Island | 3.21 | 3.47 | 1.0 | 8.8 |

| Nova Scotia | 1.92 | 2.24 | 1.0 | 7.4 |

| New Brunswick | 2.56 | 3.07 | 1.0 | 8.1 |

| Quebec | 1.02 | 1.08 | 1.0 | 5.1 |

| Ontario | 0.79 | 0.70 | 1.0 | 5.6 |

| Manitoba | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.0 | 5.3 |

| Saskatchewan | 1.17 | 1.20 | 1.0 | 5.6 |

| Alberta | 0.97 | 0.95 | 1.0 | 7.0 |

| British Columbia | 0.81 | 0.70 | 1.0 | 4.7 |

| Yukon | 0.93 | 1.03 | 1.0 | 3.7 |

| Northwest Territories | 0.96 | 1.03 | 1.0 | 7.8 |

| Nunavut | 0.74 | 0.74 | 1.0 | 13.4 |

- Sources: Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), T4 slips with employment income (for data on contributions); Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data (for data on benefits); and Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Tables 14-10-0287-01 and 14-10-0292-01 (for data on unemployment rates). CRA data are based on a 10% sample of T4 slips with employment income, and ESDC data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data.

As outlined in table 6, in 2019 women received approximately $1.12 in EI benefits for each dollar they contributed in premiums (adjusted total B/C ratio of 1.12). In particular, women aged between 25 and 44 years received the highest level of EI benefits relative to their contributions compared to those in other age groups (adjusted total B/C ratio of 1.57). This is likely due to the fact that women aged between 25 and 44 years are more likely to receive EI maternity and/or parental benefits. In comparison, men received approximately 90 cents in EI benefits for each dollar contributed in premiums (adjusted total B/C ratio of 0.90). However, this was reversed when only EI regular benefits were considered—the overall adjusted regular B/C ratio for men was higher than that for women (1.19 versus 0.76, respectively). Notably, the adjusted regular B/C ratios for men in all age groups were higher than the national average and greater than those for women.

| Age category | Adjusted total B/C ratio men | Adjusted total B/C ratio women | Adjusted total B/C ratio total | Adjusted regular B/C ratio men | Adjusted regular B/C ratio women | Adjusted regular B/C ratio total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 years old and under | 1.06 | 0.87 | 0.98 | 1.31 | 0.50 | 0.96 |

| 25 to 44 years old | 0.81 | 1.57 | 1.13 | 1.04 | 0.68 | 0.88 |

| 45 to 54 years old | 0.82 | 0.65 | 0.74 | 1.11 | 0.79 | 0.96 |

| 55 years old and over | 1.14 | 0.79 | 0.99 | 1.57 | 1.01 | 1.32 |

| Total | 0.90 | 1.12 | 1.00 | 1.19 | 0.76 | 1.00 |

- Sources: Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), T4 slips with employment income (for data on contributions); Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data (for data on benefits). CRA data are based on a 10% sample of T4 slips with employment income, and ESDC data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data.

As illustrated in chart 4, claimants who had worked in the goods-producing industries were net beneficiaries of EI benefits with both adjusted B/C ratios above the national average in 2019, while those who had worked in the services-producing industries were net contributors. The greater use of EI regular benefits by claimants who had worked in the goods-producing industries relative to those who had worked in the services-producing industries may be due to the higher proportion of seasonal employment in these industries, particularly the Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting industry and the Construction industry. As seasonal employment fluctuates during certain periods of the year, workers employed in these industries generally rely on EI benefits during the “off-seasons”, leading to higher adjusted regular B/C ratios. The difference between the goods-producing industries and the services-producing industries is less significant for the adjusted total B/C ratio. This may partly be due to the larger proportion of women working in certain services-producing industries, such as the Health care and social assistance industry and the Educational services industry, who can claim EI maternity and/or parental benefits and thus increase the relative use of EI in these industries.

Text description of Chart 4

| Industry | Adjusted regular benefits-to-contributions ratio | Adjusted total benefits-to-contributions ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Goods-producing industries | 1.91 | 1.53 |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | 3.90 | 4.05 |

| Mining and oil and gas extraction | 1.58 | 1.19 |

| Utilities | 0.41 | 0.46 |

| Construction | 3.28 | 2.28 |

| Manufacturing | 0.94 | 0.85 |

| Services-producing industries | 0.74 | 0.85 |

| Wholesale trade | 0.78 | 0.72 |

| Retail trade | 0.71 | 0.82 |

| Transportation and warehousing | 0.97 | 0.87 |

| Finance and insurance | 0.29 | 0.54 |

| Real estate and rental and leasing | 0.95 | 0.92 |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 0.70 | 0.73 |

| Business, building and other support services* | 1.37 | 1.21 |

| Educational services | 0.96 | 1.01 |

| Health care and social assistance | 0.35 | 0.86 |

| Information, culture and recreation** | 0.92 | 0.84 |

| Accommodation and food services | 1.14 | 1.15 |

| Other services (except public administration) | 1.02 | 1.03 |

| Public administration | 0.47 | 0.71 |

| Canada | 1.00 | 1.00 |

- *Includes Management of companies and enterprises and Administrative support, waste management and remediation services.

- ** Includes Information and cultural industries and Arts, entertainment and recreation services.

- Sources: Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), T4 slips with employment income (for data on contributions); Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data (for data on benefits). CRA data are based on a 10% sample of T4 slips with employment income, and ESDC data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data.

Implicit income redistribution and the Employment Insurance program

Due to differences in income support provided by the EI program across socio-economic sub-populations, the program can act as an implicit income redistribution mechanism in Canada, providing greater income support (relative to contributions) to individuals in the lower part of the income distribution as compared to those with greater earnings. A 2012 evaluation study* showed that the benefit and contribution aspects of the program tend to be redistributive and that the impact of the program on the redistribution of earnings increased substantially during the late 2000s recession.

Moreover, a study on the financial impact of receiving EI benefits** concluded that the EI program has a considerable positive income redistribution effect, with lower income families having a higher adjusted total benefits-to-contributions ratio than higher income families. In fact, families with after-tax incomes below the median received 34% of total EI benefits and paid 18% of all premiums, representing an adjusted total benefits-to-contributions ratio of close to 2.0.

- *Ross Finnie and Ian Irvine, The Redistributional Impact of Employment Insurance 2007 to 2009 (Ottawa: HRSDC, Evaluation Directorate, 2013).

- **Constantine Kapsalis, Financial Impacts of Receiving Employment Insurance (Ottawa: Data Probe Economic Consulting Inc., 2010).

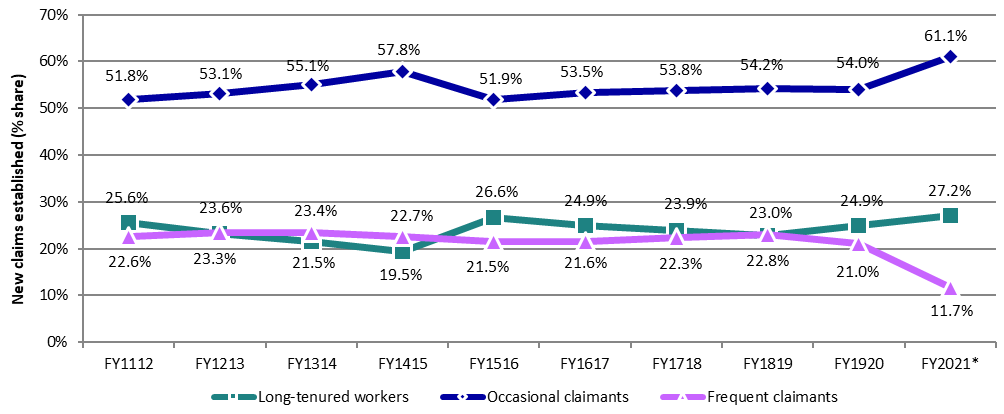

2.2 Employment Insurance regular benefits

In this section

- 2.2.1 Employment Insurance regular claims and benefits paid

- 2.2.2 Coverage and eligibility to Employment Insurance regular benefits

- 2.2.3 Level of Employment Insurance regular benefits

- 2.2.4 Employment Insurance regular benefit entitlement

- 2.2.5 Employment Insurance regular benefits and seasonal claimants

- 2.2.6 Exhaustion of Employment Insurance regular benefits

- 2.2.7 Working while on claim

Employment Insurance (EI) regular benefits are designed to provide temporary income support to partially replace lost employment income for eligible claimants while they search for work or upgrade their skills.

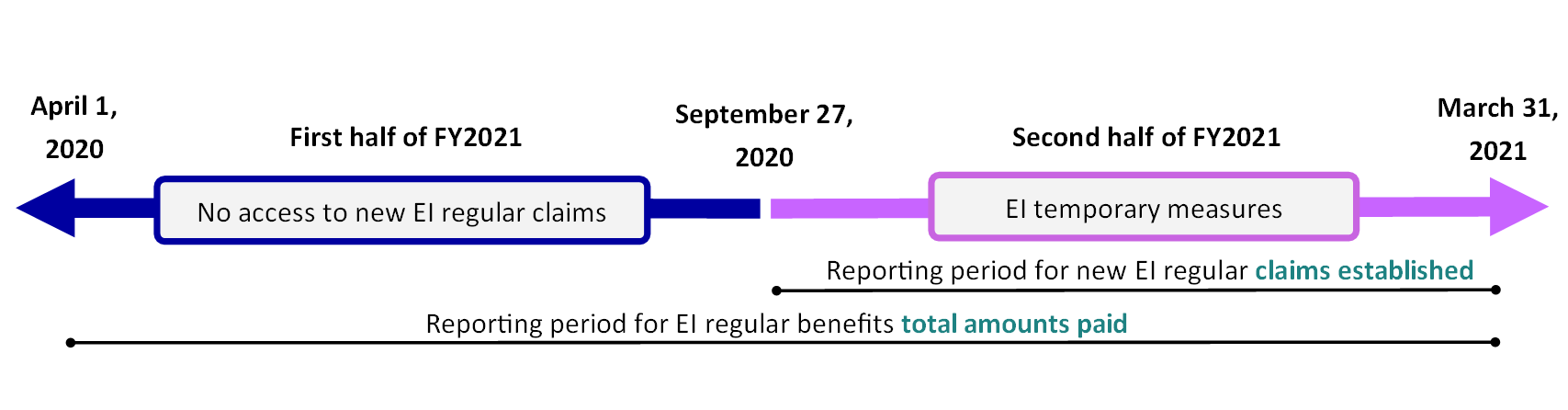

As explained in section 2.0, no new claims for EI regular benefits were established during the first half of FY2021, and some of the main indicators covered in the following subsections are presented separately for the first and the second half of FY2021.Footnote 15

Under the EI temporary measures, to qualify for EI regular benefits in the second half of FY2021, the claimant must:

- be unemployed and available for work

- have worked a minimum number of 420 hours of insurable employment (essentially 120 hours with the one-time 300 hours credit) and paid EI premiums during the qualifying period (defined as either the previous 52 weeks (or 80 weeks for claimants who received CERB) or since the establishment of their last claim, whichever is shorter), and

- have had a valid reason for job separation according to the Employment Insurance Act

2.2.1 Employment Insurance regular claims and benefits paid

Since no new EI regular claims could be established between April 1, 2020 and September 26, 2020, the reporting period of new EI regular claims is limited to only the second half of FY2021. However, the total amounts paid is reported on the entirety of FY2021 as EI regular benefits from previously established claims continued to be paid throughout the whole year.

Text description of Chart 5

| Category | Timeline |

|---|---|

| Reporting period for EI regular benefits total amounts paid | First and second half of FY2021, between April 1, 2020 and March 31, 2021 |

| Reporting period for new EI regular claims established | Second half of FY2021, between September 27, 2020 and March 31, 2021 |

| No access to new EI regular claims | First half of FY2021, between April 1, 2020 and September 27, 2020 |

| EI temporary measures | Second half of FY2021, between September 27, 2020 and March 31, 2021 |

The number of new claims established during a given period tends to be influenced by labour market conditions and overall economic cycles, as well as initiatives such as EI pilot projects or changes to the program design. During periods of economic growth and robust labour market conditions, fewer claims for EI regular benefits are established, while the opposite is true during periods of economic stagnation and unfavourable labour market conditions. As discussed in chapter 1, the COVID-19 pandemic and the public health measures in place to limit its spread had an unprecedented negative impact on the economy and the labour market in terms of employment losses aligned with each wave of the pandemic. In the second half of FY2021, 2.47 million new EI regular claims were established. This is almost double the number of claims established in the entire FY1920 (1.37 million). However, given the temporary changes to the EI program and the unprecedented labour market conditions and benefit schemes available in FY2021, this is not comparable with previous years. Therefore, year-over-year comparisons of the number of new EI regular claims established are not examined in this section.

The total amount of EI regular benefits paid increased from $11.1 billion in FY1920 to $24.9 billion in FY2021. The increase in the total amount of EI regular benefits paid in FY2021 is attributable to the temporary changes to the EI programFootnote 16 and the relatively higher number of EI regular claims established.

There was an average of 1.5 million beneficiaries receiving EI regular benefits each month in the second half of FY2021 when the EI temporary measures were in place.Footnote 17 This is significantly higher than the 344,200 average monthly EI regular beneficiaries in the first half of FY2021.Footnote 18

Because the number of beneficiaries is based on previously established claims, these 2 measures generally trend in the same direction, with the count of beneficiaries usually lagging behind the number of new claims established. To illustrate this, suppose there is an increase in the number of claims established for EI regular benefits after an economic shock. The number of beneficiaries will increase following the increase in claims. However, the count of beneficiaries can still remain elevated even after the volume of new claims has subsided once the labour market conditions improve, as payments continue to be made on previously established claims until benefits are exhausted or the claimants have found employment. Because no new EI regular claims could be established between April 1 and September 26, 2020, the number of beneficiaries of EI regular benefits in the first half of FY2021 were solely from claims established in the previous fiscal year and were decreasing each month. When EI regular benefits were made available again on September 27, 2020 under the temporary measures, there was a large increase in new EI regular claims established and the number of beneficiaries climbed. The effect of the increase in the number of claims established will likely continue to be reflected on the number of beneficiaries in the next reporting period.

Employment Insurance regular claims and amount paid by province or territory, gender and age

Table 7 outlines the number of EI regular claims established in the second half of FY2021 and the total amount paid over the entire reporting period by province or territory, gender and age. The columns presenting the percentage point change (p.p.) show the change of the shares of each respective category over the total population in FY2021 in comparison to their relative shares in FY1920. While both the number of new EI regular claims established and total amount paid increased in every category in FY2021, changes in certain categories were more significant than in others in terms of their relative shares.

| Category | Number of claims and share FY1920 | Number of claims and share Second half of FY2021 | p.p. change of relative share compared to FY1920 | Amount paid ($ million) and share FY1920 | Amount paid ($ million) and share FY2021 | p.p. change of relative share compared to FY1920 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 62,980 (4.6%) | 81,400 (3.3%) | -1.3 | $759.2 (6.9%) | $1,029.1 (4.1%) | -2.7 |

| Prince Edward Island | 14,860 (1.1%) | 18,820 (0.8%) | -0.3 | $155.5 (1.4%) | $211.6 (0.8%) | -0.6 |

| Nova Scotia | 62,100 (4.5%) | 81,630 (3.3%) | -1.2 | $588.6 (5.3%) | $905.1 (3.6%) | -1.7 |

| New Brunswick | 68,720 (5.0%) | 91,520 (3.7%) | -1.3 | $680.0 (6.1%) | $989.9 (4.0%) | -2.2 |

| Quebec | 400,460 (29.3%) | 653,980 (26.4%) | -2.8 | $2,622.2 (23.7%) | $5,906.0 (23.7%) | 0.0 |

| Ontario | 393,950 (28.8%) | 848,920 (34.3%) | +5.5 | $3,011.1 (27.2%) | $8,352.1 (33.5%) | +6.3 |

| Manitoba | 42,900 (3.1%) | 76,120 (3.1%) | -0.1 | $370.7 (3.4%) | $785.2 (3.1%) | -0.2 |

| Saskatchewan | 40,800 (3.0%) | 60,370 (2.4%) | -0.5 | $405.9 (3.7%) | $700.7 (2.8%) | -0.9 |

| Alberta | 140,540 (10.3%) | 296,840 (12.0%) | +1.7 | $1,354.1 (12.2%) | $3,304.1 (13.3%) | +1.0 |

| British Columbia | 135,800 (9.9%) | 257,310 (10.4%) | +0.5 | $1,068.7 (9.7%) | $2,675.9 (10.7%) | +1.1 |

| Yukon | 1,680 (0.1%) | 2,440 (0.1%) | 0.0 | $17.0 (0.2%) | $27.6 (0.1%) | 0.0 |

| Northwest Territories | 1,520 (0.1%) | 2,200 (0.1%) | 0.0 | $19.5 (0.2%) | $26.4 (0.1%) | -0.1 |

| Nunavut | 770 (0.1%) | 1,310 (0.1%) | 0.0 | $12.2 (0.1%) | $16.4 (0.1%) | 0.0 |

| Men | 830,770 (60.8%) | 1,371,140 (55.4%) | -5.3 | $7,348.8 (66.4%) | $14,578.4 (58.5%) | -7.9 |

| Women | 536,310 (39.2%) | 1,101,720(44.6%) | +5.3 | $3,715.6 (33.6%) | $10,351.7 (41.5%) | +7.9 |

| 24 years old and under | 122,860 (9.0%) | 381,160 (15.4%) | +6.4 | $939.3 (8.5%) | $3,157.6 (12.7%) | +4.2 |

| 25 to 44 years old | 603,290 (44.1%) | 1,042,340 (42.2%) | -2.0 | $4,783.1 (43.2%) | $10,578.0 (42.4%) | -0.8 |

| 45 to 54 years old | 286,640 (21.0%) | 445,220 (18.0%) | -3.0 | $2,342.4 (21.2%) | $4,660.7 (18.7%) | -2.5 |

| 55 years old and over | 354,290 (25.9%) | 604,140 (24.4%) | -1.5 | $2,999.6 (27.1%) | $6,533.9 (26.2%) | -0.9 |

| Canada | 1,367,080 (100.0%) | 2,472,860 (100.0%) | 0.0 | $11,064.4 (100.0%) | $24,930.1 (100.0%) | 0.0 |

- Note: Data may not add up to the total due to rounding. Percentage point change is based on unrounded numbers. Includes claims for which at least $1 of EI regular benefits was paid.

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data.

Specifically, the relative share of claims established for EI regular benefits increased in Ontario (+5.5 p.p.), Alberta (+1.7 p.p.), and British Columbia (+0.5 p.p.) in the second half of FY2021 compared to the previous fiscal year. The relative share of claims for EI regular benefits decreased across all Atlantic provinces and Saskatchewan, while staying relatively unchanged in Manitoba and all 3 territories. The most significant relative decrease in the share of EI regular claims established was observed in Quebec (-2.8 p.p.). The relative share of total amount paid in EI regular benefits similarly increased in Ontario (+6.3 p.p.), British Columbia (+1.1 p.p.) and Alberta (+1.0 p.p.) in FY2021 compared to FY1920. It stayed relatively unchanged in all 3 territories, Quebec and Manitoba, while decreasing slightly in the Atlantic provinces and Saskatchewan. Similar to previous years, Ontario and Quebec continued to account for more than half (60.8%) of total EI regular claims established in the second half of FY2021. They also made up over half (57.2%) of the total amount paid in EI regular benefits in FY2021, up from 50.9% in FY1920.

The relative share of new claims established by women increased by 5.3 percentage points during this period. Despite this, men still accounted for the majority (55.4%) of EI regular claims in the second half of FY2021, similar to previous reporting periods. In FY2021, men accounted for the over half (58.5%) of the total amount paid in EI regular benefits. This share has remained relatively stable in recent years as well.

Those aged 24 years and under had the most significant increase in their relative shares of new claims, from 9.0% in FY1920 to 15.4% in the second half of FY2021 (+6.4 p.p.). In terms of total amount paid in EI regular benefits, the share of younger claimants also had the highest increase (+4.2 p.p.) in FY2021 from FY1920. Similar to the previous years, claimants aged between 25 and 44 years continued to account for the largest share of new regular claims (42.2%) in the second half of FY2021 as well as the total amount paid in FY2021 (42.4%). Despite the largest relative increases among age groups, those aged 24 years and under still had the smallest shares (15.4% of total claims and 12.7% of total amount paid, respectively).

Employment Insurance regular claims and amount paid by industry

As outlined in Table 8, the relative share of new EI regular claims established in the second half of FY2021 increased in services-producing industries (+9.0 p.p.) from FY1920. This increase was driven mostly by increases in the share of new claims in Accommodation and food services (+7.5 p.p.) and Retail trade (+6.0 p.p.), 2 sectors heavily impacted by closures and economic shutdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic. Among the goods-producing industries, the overall share of new claims established in FY2021 decreased in all industries with a total relative decline of 11.3 percentage points from the previous reporting period. A notable relative decrease was observed in the Construction industry (‑7.0 p.p.). The relative share of new claims in the Unclassified industries category also increased by 2.3 percentage points. This was due to the missing information in the EI claims that is required to classify them. This indicates that the increases in the number of EI regular claims in some industries in FY2021 would have been even higher if these unclassified claims had been categorized. Similar to previous reporting periods, the Construction sector continued to hold the largest share of new claims established among all industry groups (14.2%).

| Industry | Number of claims and share FY1920 | Number of claims and share Second half of FY2021 | p.p. change of relative share compared to FY1920 | Amount paid ($ million) and share FY1920 | Amount paid ($ million) and share FY2021 | p.p. change of relative share compared to FY1920 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goods-producing industries | 523,350 (38.3%) | 667,470 (27.0%) | -11.3 | $4,590.7 (41.5%) | $7,138.4 (28.6%) | -12.9 |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting | 51,240 (3.7%) | 59,370 (2.4%) | -1.3 | $525.8 (4.8%) | $689.3 (2.8%) | -2.0 |

| Mining and oil and gas extraction | 24,130 (1.8%) | 33,730 (1.4%) | -0.4 | $270.0 (2.4%) | $430.8 (1.7%) | -0.7 |

| Utilities | 4,870 (0.4%) | 3,980 (0.2%) | -0.2 | $42.2 (0.4%) | $46.8 (0.2%) | -0.2 |

| Construction | 289,330 (21.2%) | 350,210 (14.2%) | -7.0 | $2,592.1 (23.4%) | $3,691.3 (14.8%) | -8.6 |

| Manufacturing | 153,780 (11.2%) | 220,180 (8.9%) | -2.3 | $1,160.7 (10.5%) | $2,280.1 (9.1%) | -1.3 |

| Services-producing industries | 801,070 (58.6%) | 1,671,510 (67.6%) | +9.0 | $6,151.8 (55.6%) | $16,428.9 (65.9%) | +10.3 |

| Wholesale trade | 41,670 (3.0%) | 83,080 (3.4%) | +0.3 | $425.2 (3.8%) | $937.8 (3.8%) | -0.1 |

| Retail trade | 76,100 (5.6%) | 286,270 (11.6%) | +6.0 | $610.1 (5.5%) | $2,405.4 (9.6%) | +4.1 |

| Transportation and warehousing | 64,460 (4.7%) | 114,250 (4.6%) | -0.1 | $499.1 (4.5%) | $1,131.8 (4.5%) | 0.0 |

| Finance and insurance | 12,480 (0.9%) | 22,230 (0.9%) | 0.0 | $148.8 (1.3%) | $258.8 (1.0%) | -0.3 |

| Real estate, rental, and leasing | 18,800 (1.4%) | 39,840 (1.6%) | +0.2 | $174.8 (1.6%) | $445.6 (1.8%) | +0.2 |

| Professional, scientific, and technical services | 55,220 (4.0%) | 87,120 (3.5%) | -0.5 | $516.5 (4.7%) | $996.0 (4.0%) | -0.7 |

| Business, building, and other support services* | 85,720 (6.3%) | 170,190 (6.9%) | +0.6 | $768.0 (6.9%) | $1,845.5 (7.4%) | +0.5 |

| Educational services | 170,300 (12.5%) | 120,670 (4.9%) | -7.6 | $823.5 (7.4%) | $793.5 (3.2%) | -4.3 |

| Health care and social assistance | 50,050 (3.7%) | 105,120 (4.3%) | +0.6 | $359.2 (3.2%) | $978.2 (3.9%) | +0.7 |

| Information, culture, and recreation** | 39,900 (2.9%) | 110,510 (4.5%) | +1.6 | $317.1 (2.9%) | $1,156.8 (4.6%) | +1.8 |

| Accommodation and food services | 72,130 (5.3%) | 317,070 (12.8%) | +7.5 | $489.4 (4.4%) | $3,383.5 (13.6%) | +9.1 |

| Other services (excluding Public administration) | 45,450 (3.3%) | 116,740 (4.7%) | +1.4 | $376.7 (3.4%) | $1,126.7 (4.5%) | +1.1 |

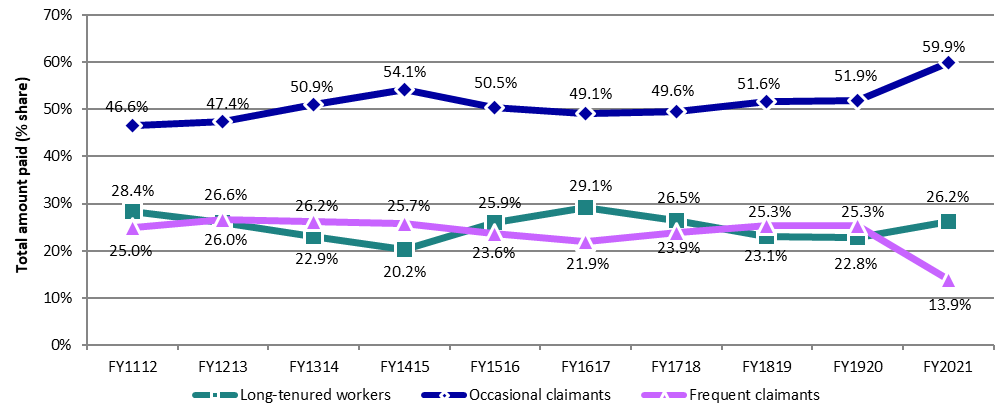

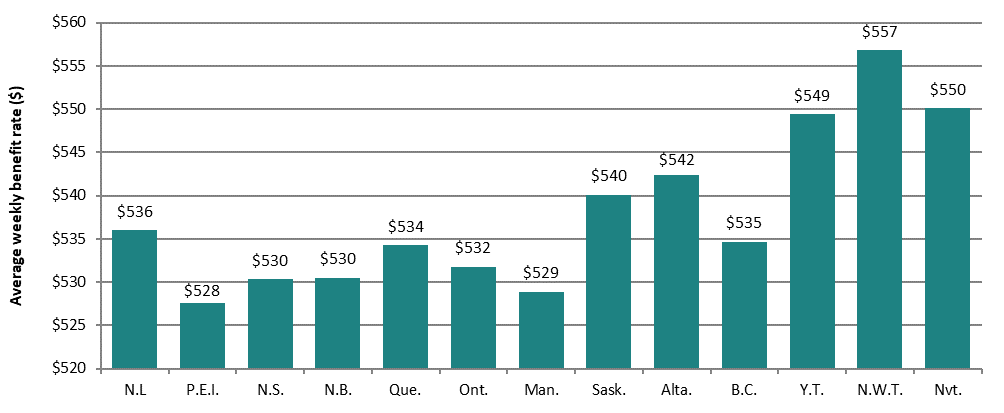

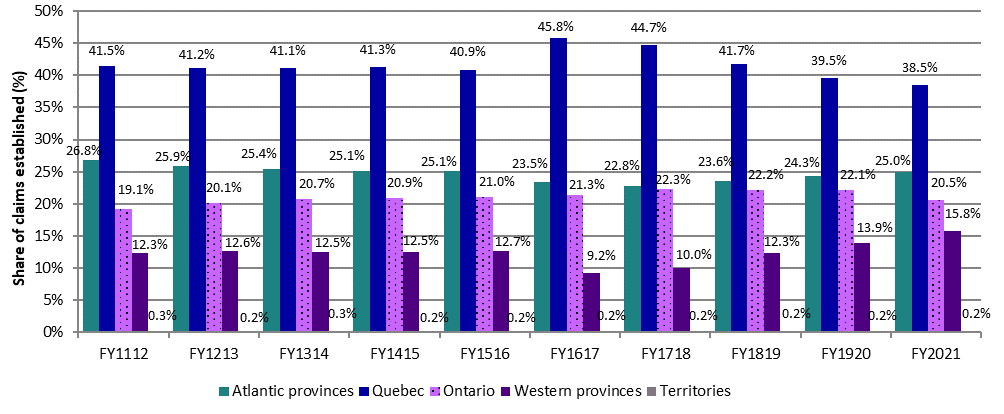

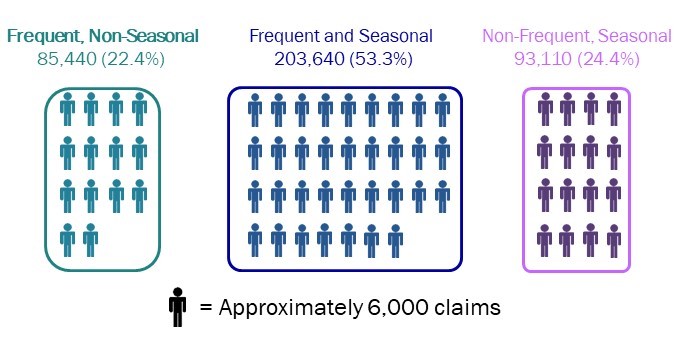

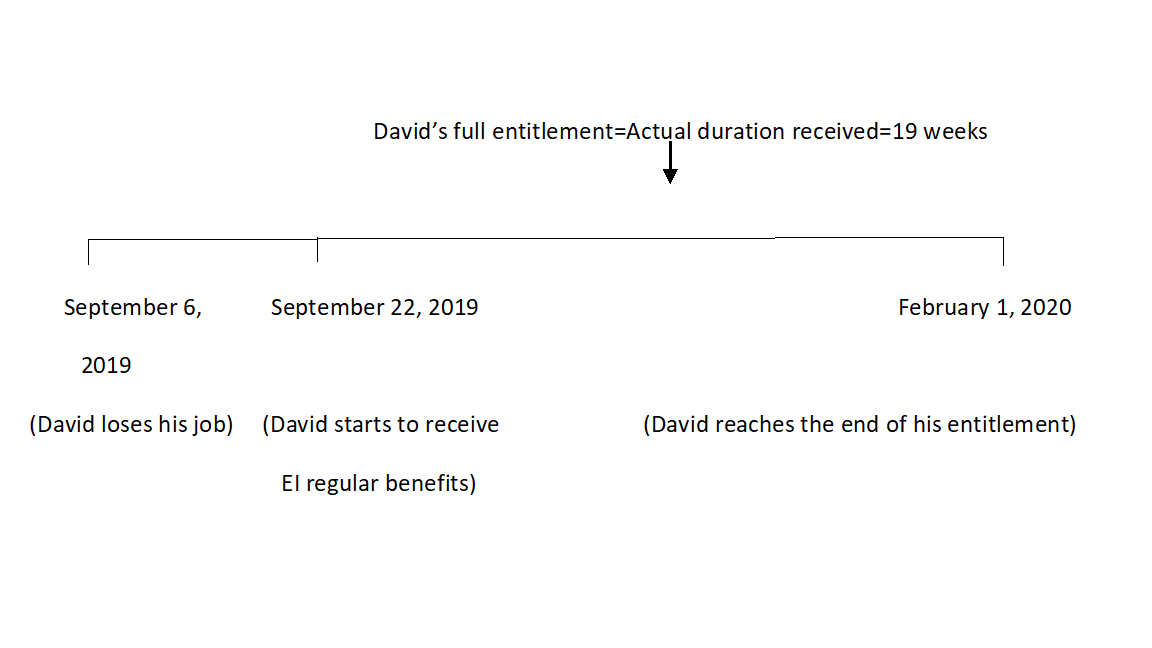

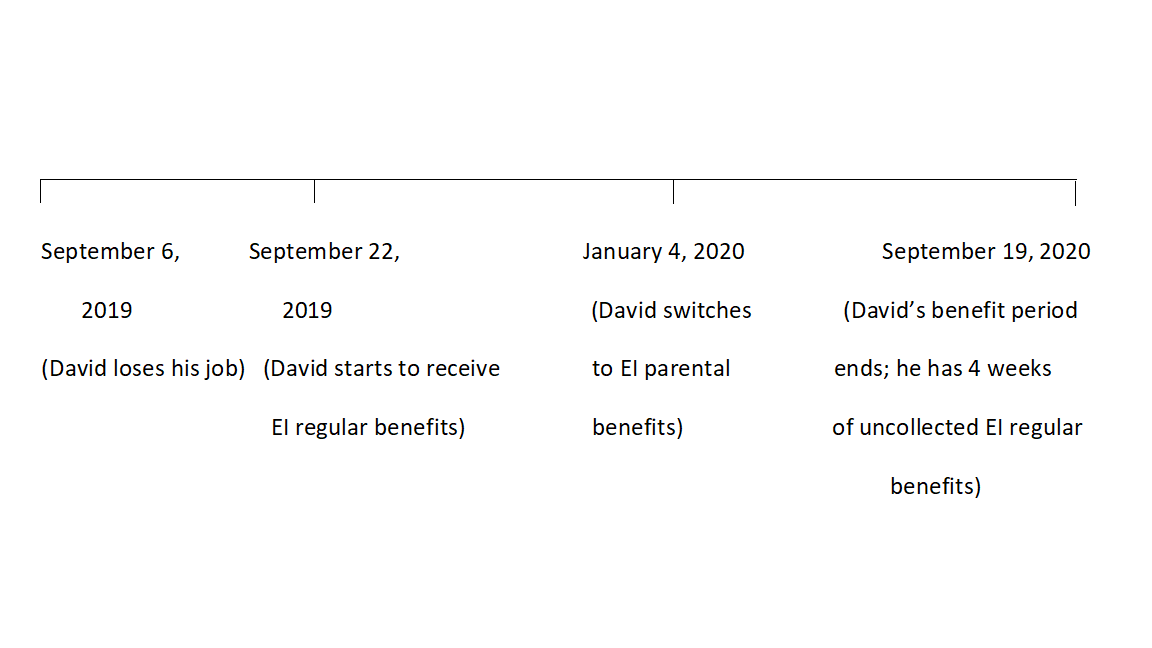

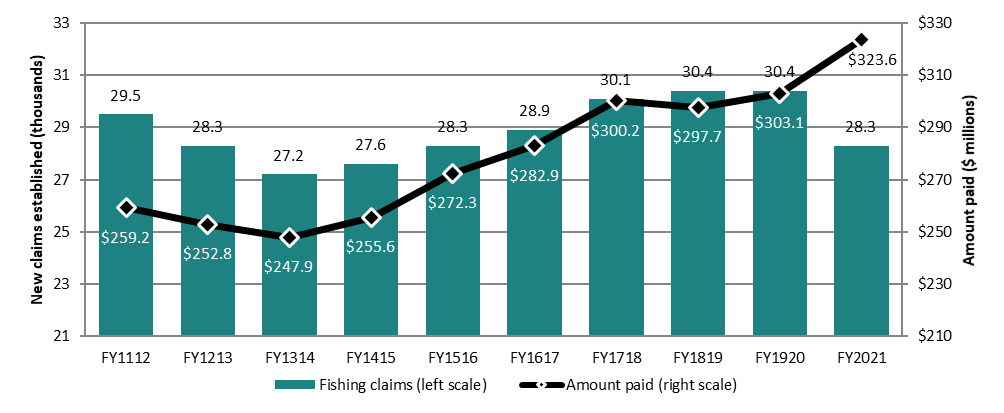

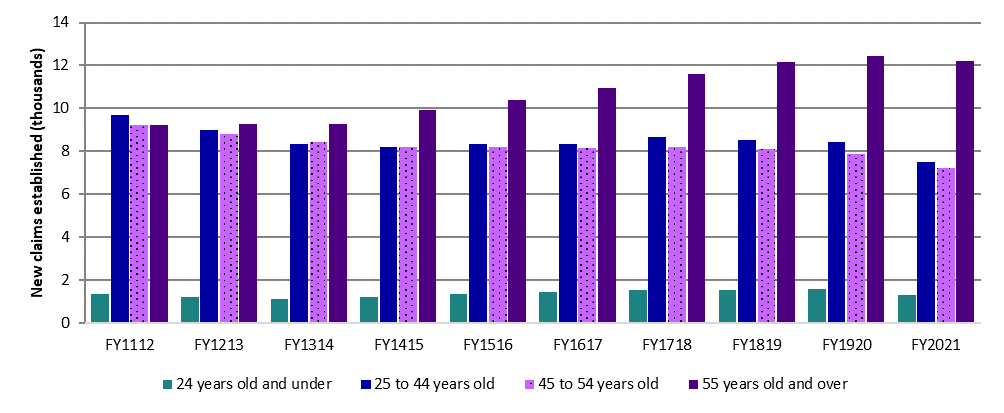

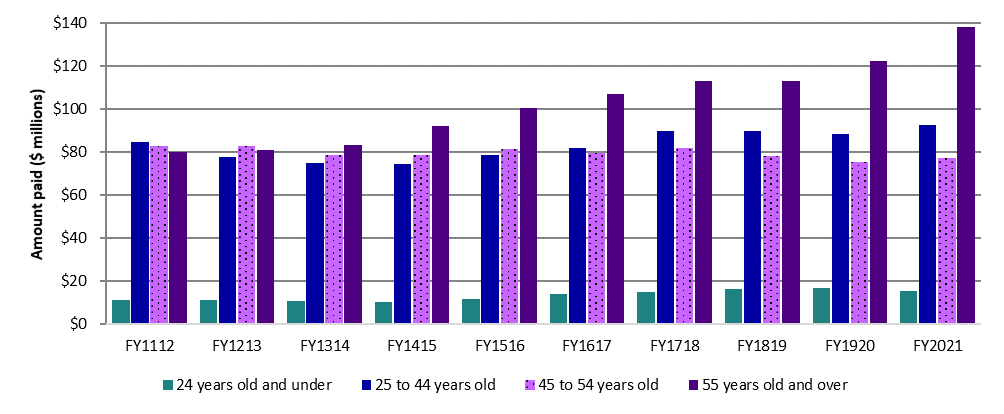

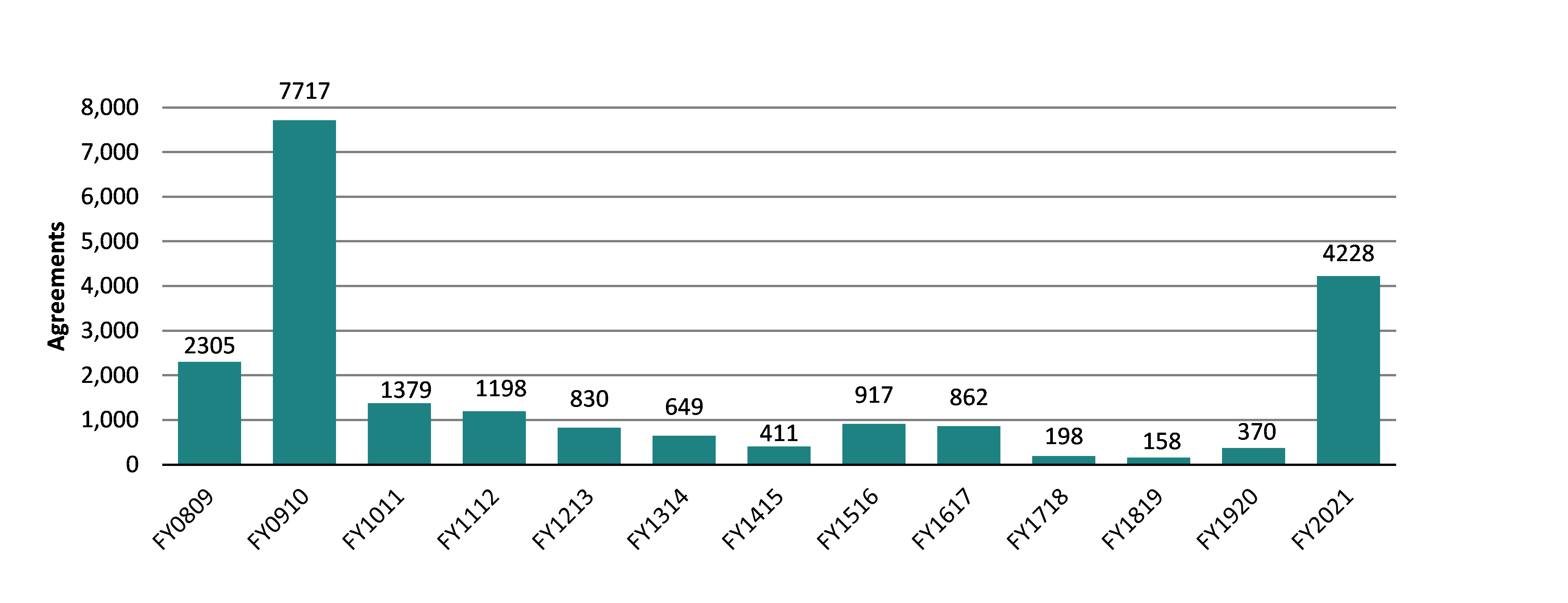

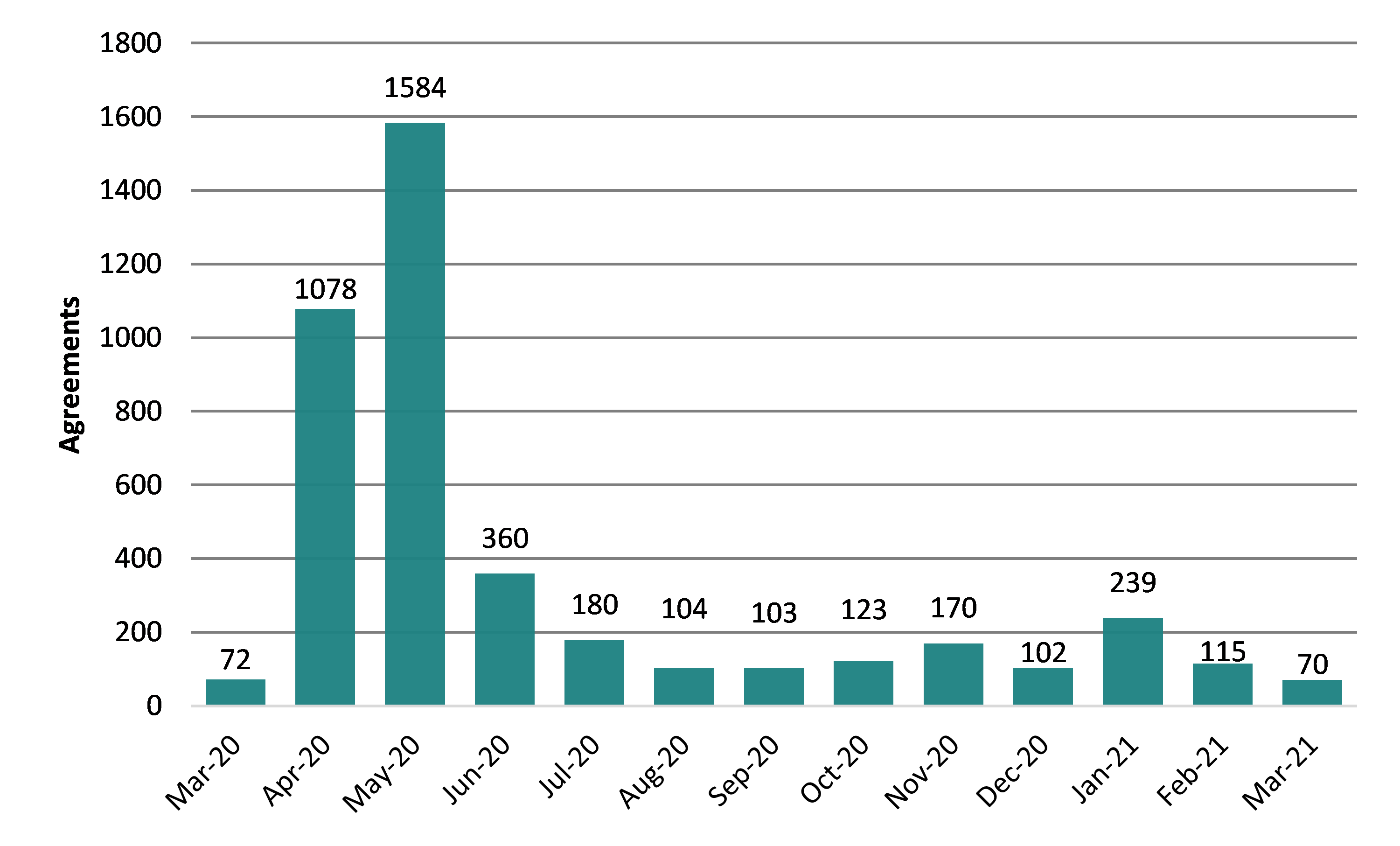

| Public administration | 68,790 (5.0%) | 98,420 (4.0%) | -1.1 | $643.4 (5.8%) | $969.2 (3.9%) | -1.9 |