Chapter 3: Impact and effectiveness of Employment Benefits and support to workers and employers (Part II of the Employment Insurance Act)

From: Employment and Social Development Canada

Official title: Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2020 and ending March 31, 2021 - Chapter 3: Impact and effectiveness of Employment Benefits and support to workers and employers (Part II of the Employment Insurance Act)

In chapter 3

- List of abbreviations

- Summary

- 3.1 Overview

- 3.2 Provincial and territorial activities

- 3.3. LMDA results

- 3.4. Pan-Canadian activities and the National Employment Service

- Annex A – Provincial and territorial results

- Annex B – National overview

- Annex C – LMDA evaluation results

- Annex D – Targeting, referral and feedback study

List of abbreviations

This is the complete list of abbreviations for the Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2020 and ending March 31, 2021.

Abbreviations

- AD

- Appeal Division

- ADR

- Alternative Dispute Resolution

- ASETS

- Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy

- B/C Ratio

- Benefits-to-Contributions ratio

- BDM

- Benefits Delivery Modernization

- CAWS

- Client Access Workstation Services

- CCDA

- Canadian Council of Directors of Apprenticeship

- CCIS

- Corporate Client Information Service

- CEIC

- Canada Employment Insurance Commission

- CERB

- Canada Emergency Response Benefit

- CESB

- Canada Emergency Student Benefit

- CEWB

- Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy

- COLS

- Community Outreach and Liaison Service

- CPP

- Canada Pension Plan

- CRA

- Canada Revenue Agency

- CRB

- Canada Recovery Benefit

- CRCB

- Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit

- CRF

- Consolidated Revenue Fund

- CRSB

- Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit

- CSO

- Citizen Service Officer

- CX

- Client Experience

- EBSM

- Employment Benefits and Support Measures

- ECC

- Employer Contact Centre

- EI

- Employment Insurance

- EI ERB

- Employment Insurance Emergency Response Benefit

- EICS

- Employment Insurance Coverage Survey

- eROE

- Electronic Record of Employment

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- eSIN

- Electronic Social Insurance Number

- FY

- Fiscal Year

- G7

- Group of Seven

- GDP

- Gross Domestic Product

- GIS

- Guaranteed Income Supplements

- HCCS

- Hosted Contact Centre Solution

- IQF

- Individual Quality Feedback

- ISET

- Indigenous Skills and Employment Training

- IVR

- Interactive Voice Response

- LFS

- Labour Force Survey

- LMDA

- Labour Market Development Agreements

- LMI

- Labour Market Information

- LMP

- Labour Market Partnerships

- MIE

- Maximum Insurable Earnings

- MSCA

- My Service Canada Account

- NAICS

- North American Industry Classification System

- NESI

- National Essential Skills Initiative

- NIS

- National Investigative Services

- NOM

- National Operating Model

- OAS

- Old Age Security

- PAAR

- Payment Accuracy Review

- PPE

- Premium-paid eligible individuals

- PRAR

- Processing Accuracy Review

- PRP

- Premium Reduction Program

- PTs

- Provinces and Territories

- QPIP

- Quebec Parental Insurance Plan

- R&I

- Research and Innovation

- ROE

- Record of Employment

- RPA

- Robotics Process Automation

- SAT

- Secure Automated Transfer

- SCC

- Service Canada Centre

- SDP

- Service Delivery Partner

- SEPH

- Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours

- SIN

- Social Insurance Number

- SIR

- Social Insurance Registry

- SST

- Social Security Tribunal

- STDP

- Short-term disability plan

- SUB

- Supplemental Unemployment Benefit

- TRF

- Targeting, Referral and Feedback

- TTY

- Teletypewriter

- UV

- Unemployment-to-vacancy

- VBW

- Variable Best Weeks

- VER

- Variable Entrance Requirement

- VRI

- Video Remote Interpretation

- WCAG

- Web Content Accessibility Guidelines

- WWC

- Working While on Claim

Summary

The Federal government’s largest investment in training is through bilateral Labour Market Development Agreements (LMDAs) with Provinces and Territories (PTs). Each year, the Government of Canada provides over $2 billion for individuals and employers to receive training and employment supports, through the LMDAs. In FY2021, more than 600,000 participants across Canada received training and employment supports.

LMDAs were an important support in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. LMDAs assisted more than 226,000 participants while they were out of work and receiving federal emergency income benefits (Canada Emergency Response Benefits or Canada Recovery Benefits) helping them to be ready with the skills needed to participate in economic recovery. Over 155,000 Canadians returned to work following assistance funded through EI Part II.

Employers are an important partner in helping workers receive the training and supports they need to succeed in the labour market. Under the LMDAs, PTs collaborate and support employers and industry stakeholders to develop strategies to attract and retain skilled and diverse workforce, and other creative solutions to help address the labour market needs.

Supporting underrepresented individuals is a priority for the Government of Canada. Individuals from underrepresented groups, such as Indigenous peoples, persons with disabilities, visible minorities and women, have been disproportionately affected by unemployment, reduced working hours and business disruptions as result of the pandemic.

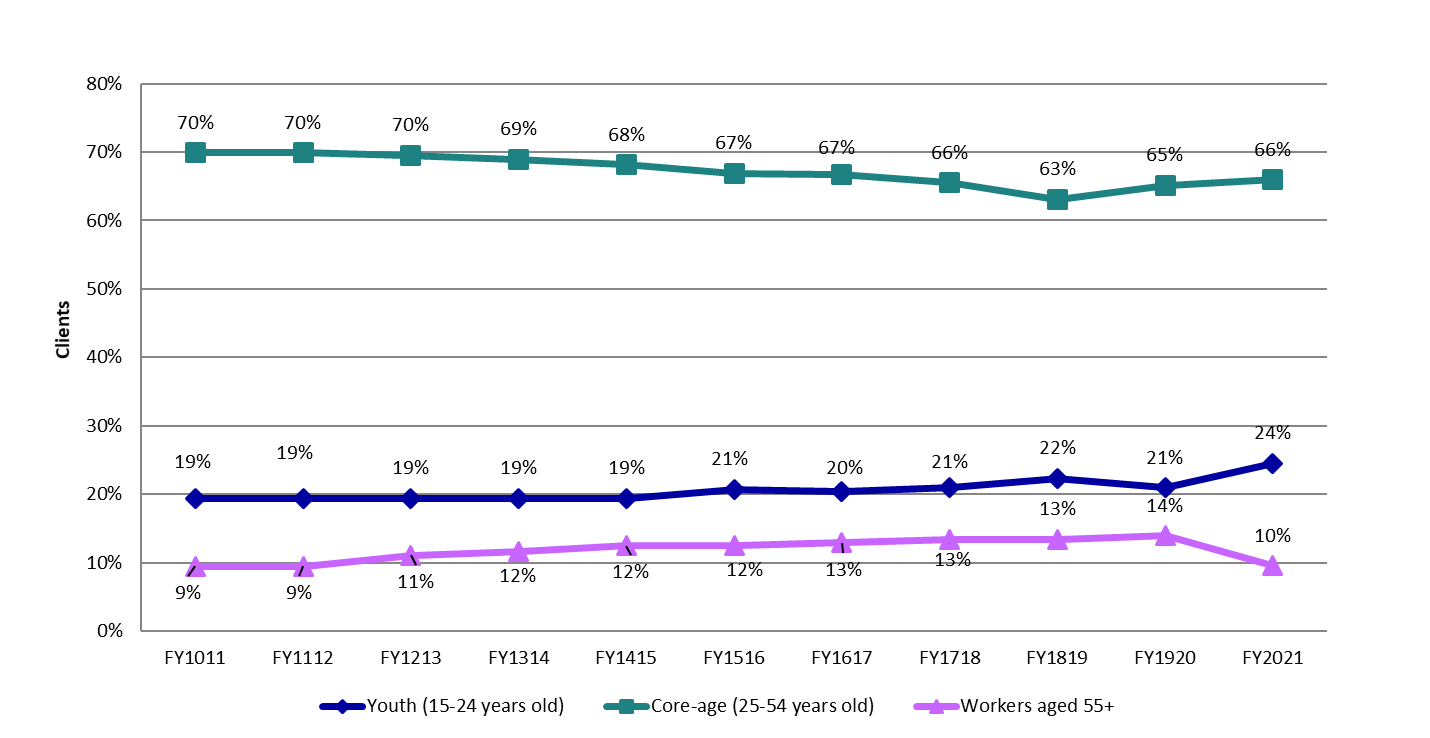

As jurisdictions continue to navigate the uncertainties related to the pandemic and fill labour shortages, assisting underrepresented groups gain access to training and employment programming is key for economic recovery. With the training supported by the LMDAs, underrepresented individuals will be better positioned to find and maintain in-demand employment opportunities. This year, under the LMDAs, clients served included:

- 92,000 participants were persons with disabilities representing 14% of participants served; persons with disabilities account for 16% the labour force

- 87,000 participants were visible minorities representing 17% of participants served; visible minorities account for 22% of the labour force

- 50,000 participants were Indigenous Peoples representing 8% of participants served; Indigenous Peoples account for 4% of the labour force

- 63,000 participants were older workers (55+) representing 10% of participants served; older workers account for 22% of the labour force

- 157,000 participants were youth (15-24) representing 24% of participants served; youth account for 14% of the labour force

- 301,000 participants were women representing 47% of participants served; women account for 47% of the labour force

EI Part II

Part II of the EI Act sets out the framework for the LMDAs, who is eligible for supports, and the categories of programs and supports that can be delivered by PTs. In addition, part II includes the framework for the Government of Canada’s pan-Canadian programming and the functions of the National Employment Service (NES).

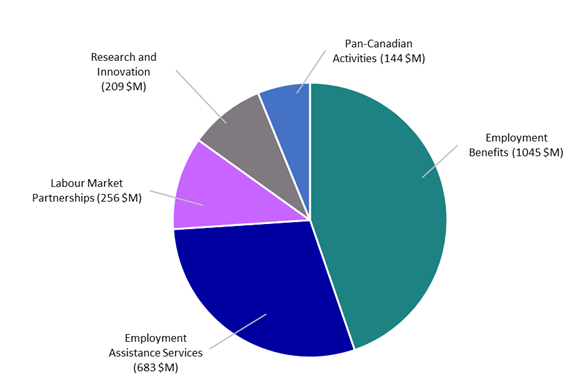

Employment Benefits and Support Measures include programs delivered under EI Part II to help individuals in Canada prepare for, find, and maintain employment. The PTs deliver these programs through LMDAs. In the case of pan-Canadian programming, the Government of Canada is responsible for program delivery.

Under the LMDAs, PTs deliver programs and services similar to the Employment Benefits and Service Measures (EBSMs) established under Part II of the Employment Insurance Act in 1996, and reflect the program categories delivered by Canada prior to the introduction of the LMDAs in 1997. The 8 EBSM categories are as follows:

Employment benefits:

- Targeted Wage Subsidies

- Assists participants to obtain on-the-job work experience by providing employers with financial assistance toward the wages of participants

- Targeted Earnings Supplements

- Encourages unemployed persons to accept employment by offering them financial incentives

- Self-Employment

- Provides financial assistance and business planning advice to eligible participants to help them start their own business

- Job Creation Partnerships

- Provides participants with opportunities to gain work experience that will lead to ongoing employment

- Skills Development

- Helps participants to obtain employment skills by giving them direct financial assistance that enables them to select, arrange for and pay for their own training

Support measures:

- Employment Assistance Services

- Provides funding to organizations to enable them to provide employment assistance to unemployed persons, which may include individual counselling, action planning, job search skills, job-finding clubs, job placement services, and more

- Labour Market Partnerships

- Provides funding to help employers, employee and employer associations, and communities to improve their capacity to deal with human resource requirements and to implement labour force adjustments

- Research and Innovation

- Supports activities that identify better ways of helping people to prepare for or keep employment and to be productive participants in the labour force

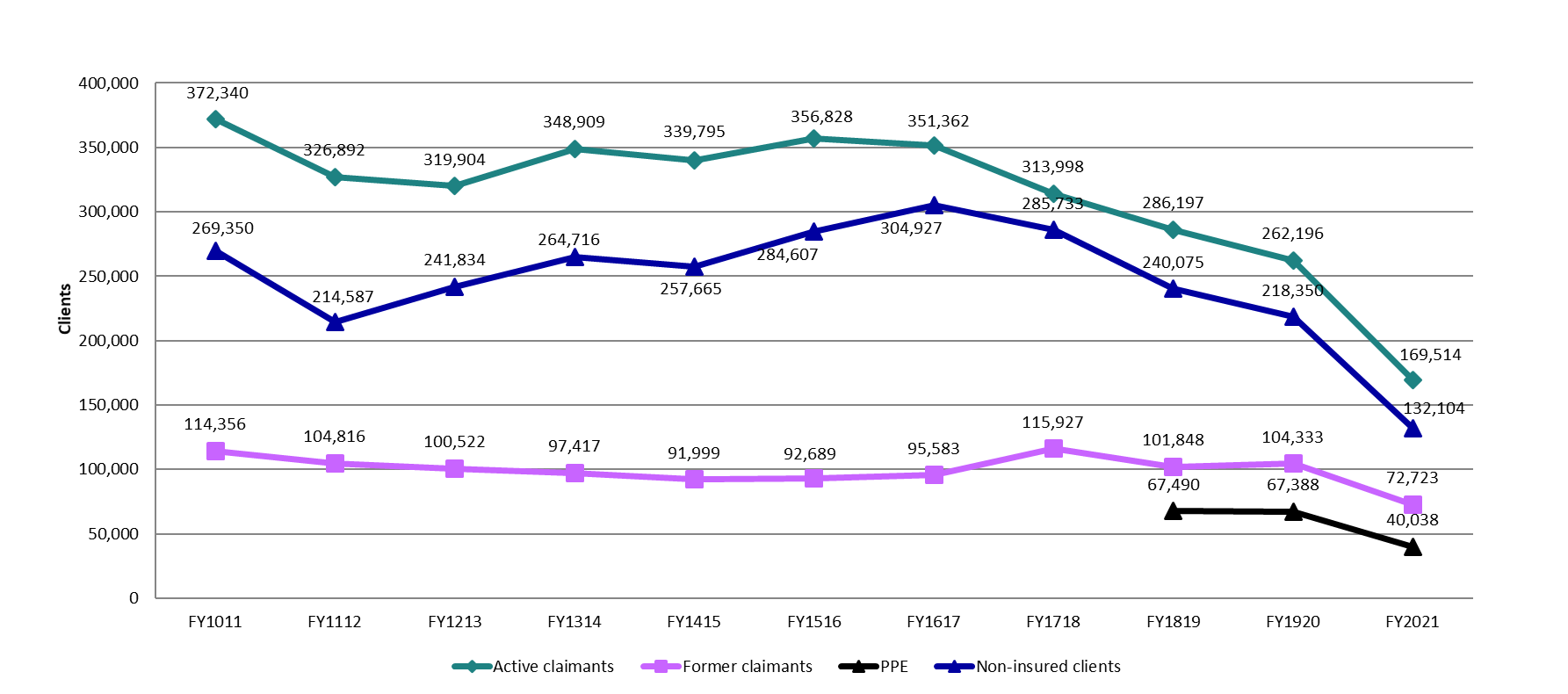

To ensure the broadest reach for EI contributors, EI Part II supports are available to active EI claimants, former EI claimants, premiums-paid eligible individuals (PPE), and non-insured clients.

- Active claimants are those who had an active EI Part I regular claim when they requested labour market supports. Typically, they have stronger and more recent job attachment. They tend to be able to return to work more quickly than those with weaker ties to employment

- Former claimants are those who completed an EI claim in the previous 5 years, or who claim in the last 5 years when they requested assistance under Part II

- In 2018, eligibility was expanded to include all unemployed individuals who have made EI premium contributions on $2,000 or more in earnings in at least 5 of the last 10 years. This change particularly benefits individuals with weaker labour force attachment

- Non-insured individuals can receive employment assistance services and include new labour force participants and individuals who were formerly self-employed without paid employment earnings. While these clients are not eligible for Employment Benefits under EI Part II, they may access Employment Assistance Services.

Results

This chapter presents program results for the year beginning on April 1, 2020 and ending on March 31, 2021.

- Section 1 - labour market context

- Section 2 - activities and results by PT

- Section 3 - national results

- Section 4 - Pan-Canadian Activities and the National Employment Service

Further details on the following are provided in Chapter 3 annexes: the national overview, PT programming, evaluation studies, and Targeting, Referral and Feedback (TRF) results.

3.1 Overview

In this section

3.1.1 Labour market context

In 2020, employment in Canada declined by almost 1 million compared to 2019, with the national unemployment rate rising by 3.8 percentage points to 9.5%. All jurisdictions experienced net job losses. Newfoundland and Labrador was the province to face the highest unemployment rate (14.1%), while the largest year-over-year increases were experienced by Alberta (+4.4 percentage points) and British Columbia (+4.2 percentage points).

The Government of Canada introduced support programs for businesses as the pandemic affected their ability to operate and survive. In the first quarter of FY2021, nearly 41% of businesses reported that they laid off staffFootnote 1. Even in the period between the first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, employers continued to face challenges ranging from a limited availability of inputs to rising prices or insufficient demand for their goods or services, leaving them uncertain how to hire or train staff for a post-pandemic recovery.

Both laid-off and actively employed workers were increasingly unsure about what type of training to take in the rapidly changing labour market. For example, Canada saw a drop of almost 29% in new apprenticeship registrationsFootnote 2, which could have a lasting impact on the supply of skilled trade workers in coming years.

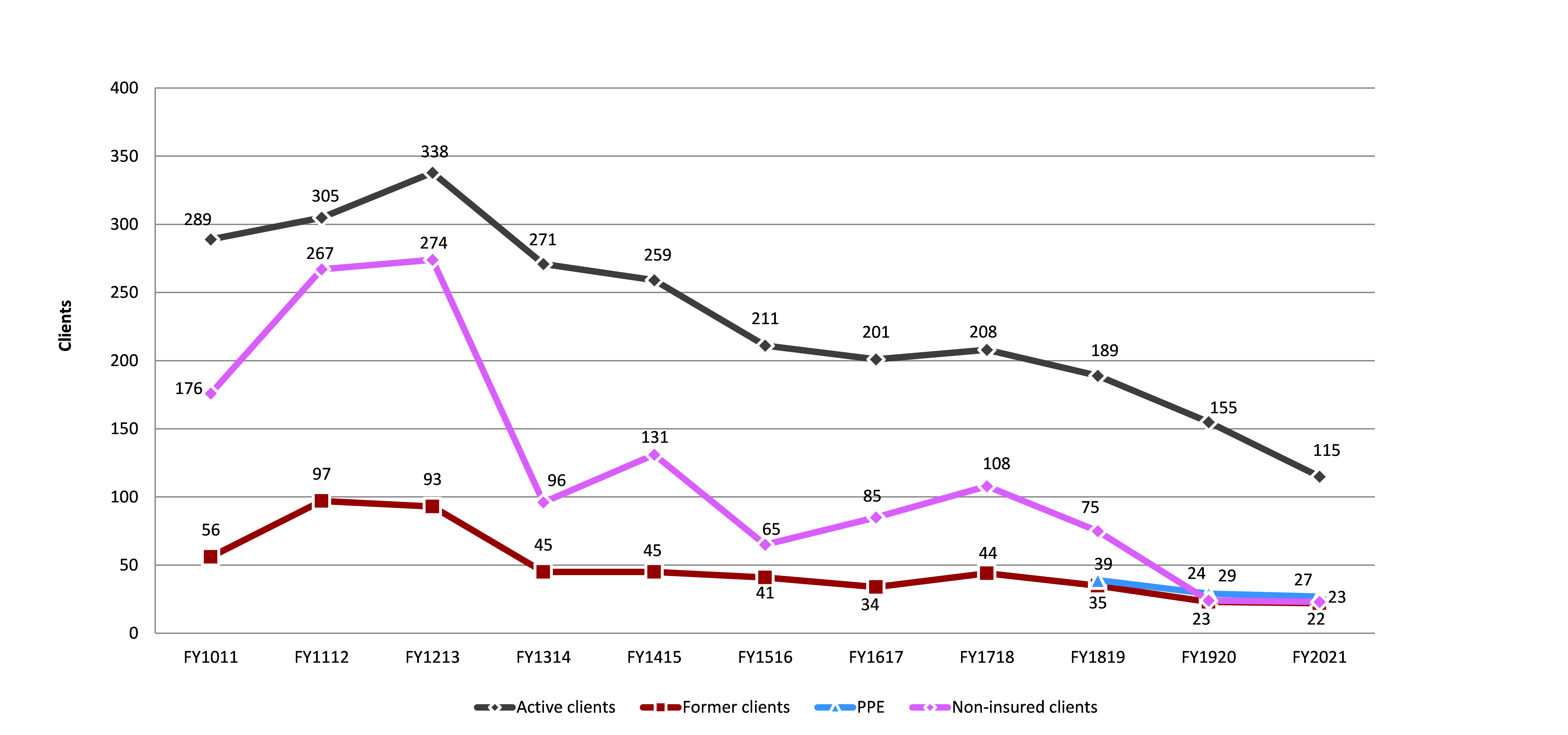

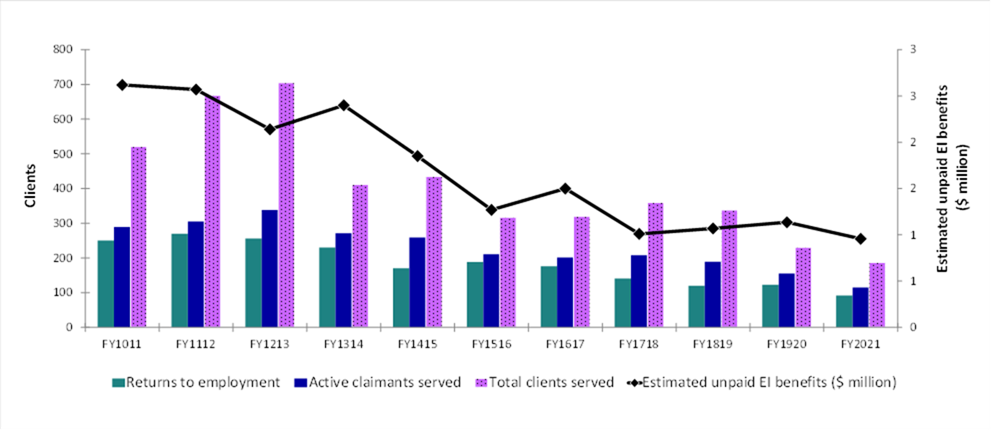

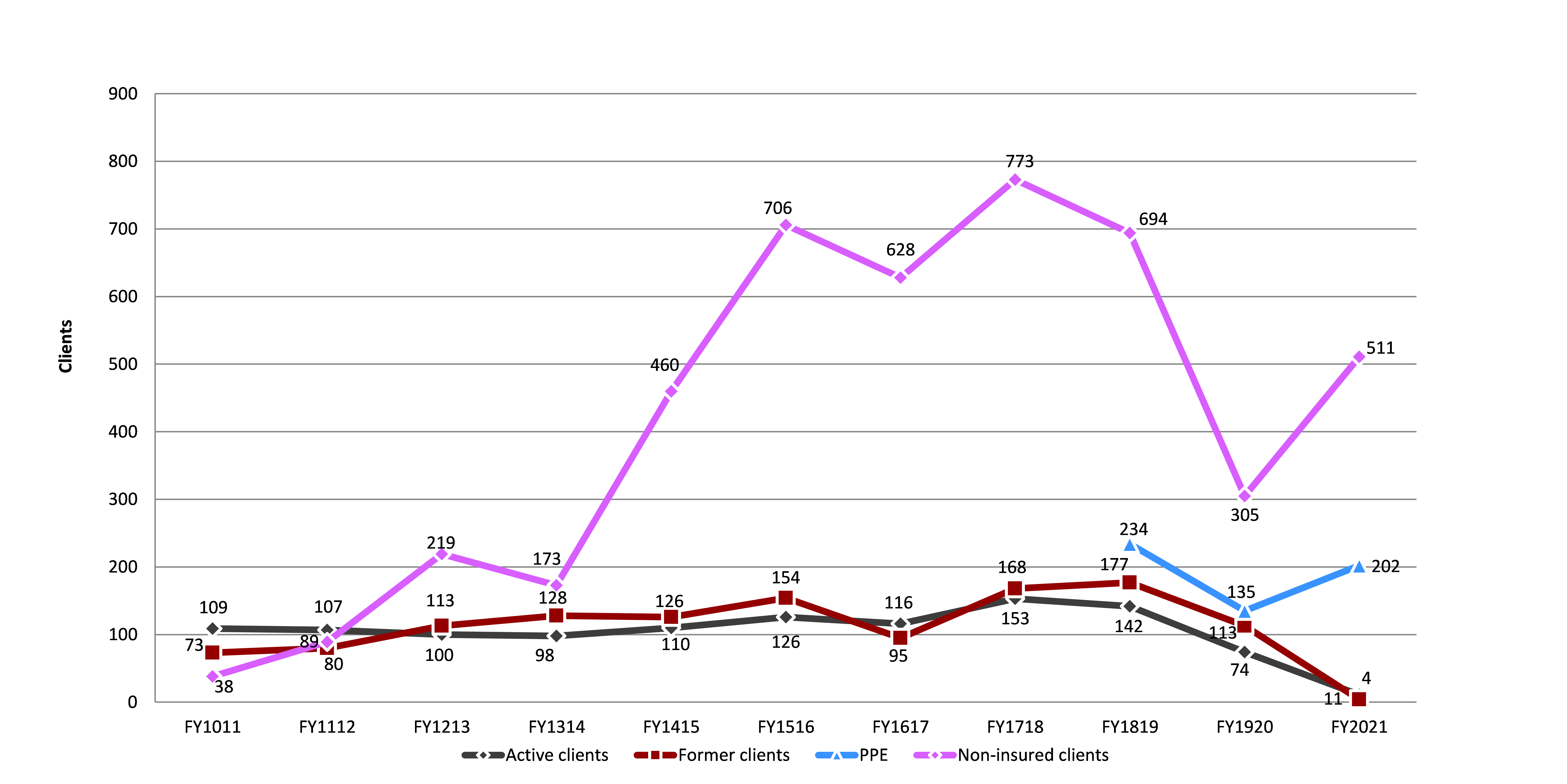

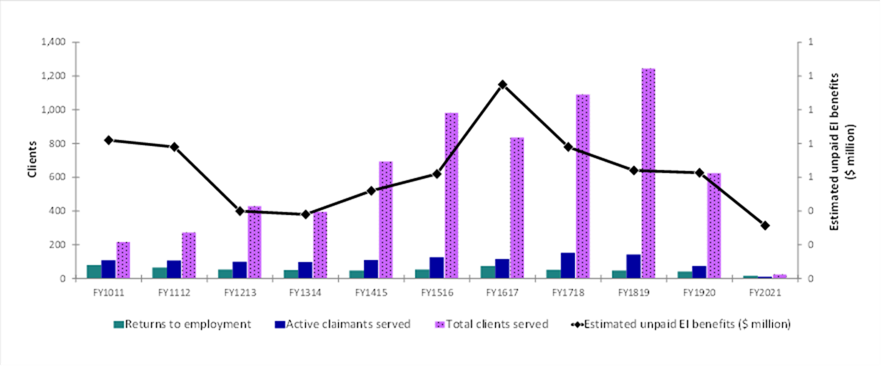

In a weaker economy, and with a 35% decrease in active claimants served, the fact that over 155,000 Canadians returned to work following assistance funded through EI Part II, and saving $800 million in unpaid EI Part I income benefits, are both positive results.

In the context of a year marked by COVID-19, PTs adapted their services and programs to respond to public health conditions which affected access to in-person training and services.

3.1.2 Adapting service delivery

In FY2021, PTs adapted their services and programs to remain effective while operating within the context of the pandemic. This entailed a rapid shift both for staff and clients from walk-in access and in-person service to mail, phone, and virtual communications platforms.

For example, in Newfoundland and Labrador, the suspension of in-person access for the general public and working from home arrangements for staff led to a new approach to case management. All program delivery models were revised to accommodate internal and external individuals’ ability to access on-line delivery. British Columbia’s efforts to effectively engage potential clients online included testing marketing emails, in collaboration with the B.C. Behavioural Insights Group. The province found that the best performing version, presenting information as a checklist, increased engagement by up to 60%.

As local public health measures permitted, in-person services resumed, in some cases by appointment. In Manitoba, both direct and alternate service models required adaptation, learning, and the acquisition of new tools and resources, such as online meeting platforms. Organizations also had to ensure their physical locations were in compliance with public health regulations, such as social distancing, physical barriers, and enhanced sanitization measures.

To address labour shortages caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and support economic recovery, Quebec established a free online employment service that helped match job seekers (full-time, part-time, student or seasonal workers) and employers according to profiles and labour market needs.

3.1.3 Working with stakeholders

All jurisdictions undertake extensive consultations with employers and with organizations representing employers. Under the LMDAs, PTs consult with labour market stakeholders in their jurisdictions to set priorities and inform the design and delivery of programs and services that meet the needs of their local labour markets. The resulting insights on their labour market needs then inform the programs and services offered to support employers through the LMDAs.

This year, in Atlantic Canada, provinces worked with communities and regional stakeholders to ensure programming responded to the demographic pressures posed by an aging workforce and out-migration.

Quebec launched an initiative to provide direct support to businesses that were experiencing a reduction in their usual operations due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. With the Programme d’actions concertées pour le maintien en emploi (PACME), Quebec used its LMDA funds to offer businesses a subsidy of up to 100% of wage expenses when their workers underwent training, helping employers retain workers and increase their skills. In FY2021, more than 6,000 businesses or organizations were assisted under the Business component of the program.

Quebec, in collaboration with the Commission des partenaires du marché du travail (CPMT), organized a Virtual Forum on Labour Force Requalification and Employment. A consensus reached at this forum on the need to upgrade skills and requalify unemployed workers, led to the launch of Programme d’aide à la relance par l’augmentation de la formation (PARAF). The objective of PARAF was to encourage unemployed people, including the pandemic unemployed, to upgrade their skills in preparation for economic recovery. With a budget of $115 million from the Canada-Quebec LMDA, this program increased participants’ income support to $500 per week. This benefited approximately 20,000 people, 40% of them in priority sectors such as Information Technology (IT), health, construction, and early childhood education and care.

Saskatchewan hosted webinars with Chambers of Commerce and industry associations to ensure employers were aware of provincial and federal support programs. More than 1,000 individuals from over 80 organizations participated in these events. The province also aided businesses by identifying critical jobs and competencies in order to offer the right training to help maintain a supply of qualified workers. The flow of workers to priority sectors was also promoted through hands-on, immersive virtual technology that allows labour market entrants and workers in transition to try out in-demand occupations.

As the pandemic increased the demand for health care services, job vacancies in that sector increased. British Columbia launched the Health Career Access Program to help employers attract, train, and retain health care assistants. This program expanded to address staffing shortages in the long term care, assisted living and home and independent living sectors.

British Columbia: Fast Track Training for Health Care Aides project

Western Community College in British Columbia, received over $620,000 in LMDA funding to support 48 unemployed job seekers to gain the skills needed to become employed in the health care industry. Participants in the project included immigrant job seekers and youth. The Fast Track Training for Health Care Aides project provided participants with occupational skills training and work experience to prepare them for employment as health care assistants. The participants of this project contributed to the care of individuals in care facilities, as well as the support of frontline workers, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Alberta launched the Energy Career Transition and Employment Resource website to help unemployed and under-employed oil and gas workers assess emerging opportunities in adjacent sectors, including clean technology and high technology in oil and gas.

In Nova Scotia, under the Cape Breton Infrastructure Projects: Workforce Development, the province partnered with industry and communities in Cape Breton to support training and skills development to ensure a qualified, ready, local construction sector workforce and to enhance employment opportunities among diverse communities. Nova Scotia also introduced the Human Resources Support Services (HRSS) for employers. Through HRSS, provincial workforce consultants work with employers to identify human resource (HR) needs, recommend flexible and innovative services to address those needs, and also to support employers with assistance in recruitment, training and other areas of HR management.

New Brunswick also introduced targeted supports for employers, through its own HRSS which mirror the case-management approach the province uses with individuals. HRSS assists employers in assessing their HR needs, recommends options and supports workforce management, including attracting and retaining the right employees to meet operational needs. Workforce consultants across the province conducted approximately 2,200 HR needs assessments and provided approximately 2,100 HRSS services in FY2021. A new client management system used to collect and track HR needs assessments and provided services was used to report on local labour market information and support evidence-based decisions related to employer initiatives.

New Brunswick provided employers and job seekers virtual job fairs. These events continued to be in high demand, as they not only were able to continue during the COVID-19 crisis, but they also allowed participation by job seekers from outside of New Brunswick.

In Ontario, the LMDA-funded Canada-Ontario Job Grant (COJG) program provided direct support to individual employers or employer consortia who wished to purchase training for their employees. COJG supports workforce development, encourages greater employer involvement in training and provides individuals with the skills necessary to obtain or maintain employment and to advance in their careers.

Also in Ontario, the LMDA-funded Skills Advance Ontario (SAO) initiative funds partnerships that connect employers with the employment and training services required to recruit and advance workers with the right essential, technical, and employability skills. It also supports jobseekers and incumbent workers by connecting them to the right employers and by providing them with sector-specific employment and training services. Approximately 7% of SAO clients in FY2021 were persons with disabilities and 14% of SAO were social assistance recipients.

3.1.4 Meeting the needs of underrepresented groups

Despite varying economic and labour market conditions, all jurisdictions prioritized improvements to both the labour market attachment of underrepresented groups, such as persons with disabilities, Indigenous people, recent immigrants, youth, and older workers, and employers’ access to a skilled workforce.

For example, the Yukon’s Working UP program focuses on strengthening workplace skills to build or maintain the labour market attachment of individuals from under-represented groups. The program has increased individuals’ foundational and vocational skills and their movement along the employment continuum in the food production, tourism and hospitality sectors. Support activities include training current staff for internal promotion or hiring and training new staff for hard to fill positions. Through LMDA supports, a number of employers have developed annual essential skills development programs for their employees.

As a result of the flexibility and diversity in Yukon’s Building Up, Yukon’s commitment to Truth and Reconciliation and developing labour market programming with First Nations, Kwanlin Dün First Nation House of Learning has delivered employment programming through traditional ways of knowing and doing. Whether on the land or through traditional knowledge circles, Yukon has noted that participation in this programming has resulted in progression toward citizen’s employment goals.

Alberta, used LMDA funds to implement programs to serve the province’s youth. Both in Edmonton and Calgary, new Transition to Employment Services (TES) programs aimed at combating the high unemployment rates among 18 to 24 year-olds. TES programs support unemployed or marginally employed young Albertans who require career change assistance or access to short term training funds to facilitate entry or re-entry into the workforce. To aid in securing a job, participants can access job placement, job search assistance, job matching, and skill transferability assistance, along with unpaid work exposure.

In Edmonton, a new Workplace Training program, YouthCO, provides workplace training opportunities for individuals aged 18 to 24. The program provides a progression of training and work experience that will lead to sustainable employment.

British Columbia: Heavy Equipment Operator Training for Tla’amin Nation Land Development for Cultural Gatherings

The Vancouver Island University received over $550,000 from the LMDA to support unemployed job seekers gain the skills needed to become employed as heavy equipment operators. Participants on the project included Indigenous job seekers. The Heavy Equipment Operator Training for Tla’amin Nation Land Development for Culture Gatherings project provided participants with occupational skills training and work experience to prepare them for employment as heavy equipment operators in the areas of road building, forestry operations, land development, mining, landscaping, and demolition.

The participants in this project contributed to development of raw land into cultural gatherings spaces for the Tla’amin Nation, including a campsite relocation, new cultural building site, and other land development projects to host up to 5,000 guests. This project helped achieve greater labor market participation for Indigenous Peoples.

3.2 Provincial and territorial activities

In this section

- 3.2.1 Newfoundland and Labrador

- 3.2.2 Prince Edward Island

- 3.2.3 Nova Scotia

- 3.2.4 New Brunswick

- 3.2.5 Quebec

- 3.2.6 Ontario

- 3.2.7 Manitoba

- 3.2.8 Saskatchewan

- 3.2.9 Alberta

- 3.2.10 British Columbia

- 3.2.11 Northwest Territories

- 3.2.12 Yukon

- 3.2.13 Nunavut

Each year, the Government of Canada provides support for individuals and employers across Canada to obtain skills training and employment supports through the bilateral LMDAs with PTs. All jurisdictions engage employers and other key stakeholders in establishing programming priorities to ensure that active labour market programs and services are responsive to local labour market needs, and that job seekers are connected with employers.

| Province/Territory | Base funding | Administrative funding | Budget 2017 top up | Final total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | $127.3 | $8.9 | $14.1 | $150.3 |

| Prince Edward Island | $23.8 | $2.7 | $3.3 | $29.8 |

| Nova Scotia | $77.3 | $10.1 | $13.7 | $101.1 |

| New Brunswick | $88.7 | $8.9 | $13.9 | $111.5 |

| Quebec | $558.6 | $58.9 | $89.0 | $706.5 |

| Ontario | $568.8 | $57.3 | $115.2 | $741.3 |

| Manitoba | $43.8 | $6.1 | $11.8 | $61.7 |

| Saskatchewan | $37.8 | $6.0 | $10.6 | $54.4 |

| Alberta | $140.5 | $9.6 | $42.3 | $192.4 |

| British Columbia | $273.9 | $20.5 | $34.8 | $329.2 |

| Yukon | $3.9 | $0.4 | $0.3 | $4.6 |

| Northwest Territories | $2.9 | $1.5 | $0.5 | $4.9 |

| Nunavut | $2.7 | $0.8 | $0.5 | $4.0 |

| Canada | $1,950.0 | $191.7 | $350.0 | $2,491.7 |

3.2.1 Newfoundland and Labrador

In FY2021, $150.3M was provided through the Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador LMDA for training and employment supports to individuals and employers. More than 15,700 participants across the province received training and employment supports, including more than 7,400 participants who were receiving federal emergency income benefits (CERB or CRB). Close to 1,500 individuals gained employment after receiving LMDA-funded supports. Compared to FY1920, the number of clients served dropped by 29%. For details, see annex A.

The pandemic affected many key industries in Newfoundland and Labrador, including the oil and gas, hospitality, and retail sectors. In some cases COVID-19 compounded existing drivers of change in the labour market, such as outsourcing, offshoring and the increased use of digital technologies to monitor and control the production and delivery of products and services.

Partnerships with the business community in several sectors focussed on generating new economic activity and fostering job creation. The province’s Workforce Innovation Centre hosted sessions with a number of organizations, including those representing: Indigenous people, persons with disabilities, youth, older workers, women, and newcomers to the province.

Key themes and focus areas included:

- increased collaboration and partnerships

- continued emphasis on immigration and attracting talent

- improved access to labour market information

- closing skills gaps through skills development and mentorship opportunities

- enhanced awareness and access to programs and services, and

- promotion of inclusive and diverse workplaces

Newfoundland and Labrador’s Performance Recording Instrument for Meaningful Evaluation (PRIME) research project was completed in FY2021. PRIME was piloted by career practitioners and data from this project demonstrated significant positive changes in clients across a range of employability indicators and outcomes as they progress through career and employment services. PRIME is now being implemented for wider use by community partners delivering employment assistance services.

3.2.2 Prince Edward Island

In FY2021, $29.8M was provided through the Canada-Prince Edward Island LMDA for training and employment supports to individuals and employers. More than 9,700 participants across the province received training and employment supports, including more than 4,900 participants who were receiving federal emergency income benefits (CERB or CRB). Close to 1,900 individuals gained employment after receiving LMDA-funded supports. For the second consecutive year, the number of clients served in Prince Edward Island declined. Compared to FY1920, the number of clients served decreased by 15%. For details, see annex A.

In FY2021, Prince Edward Island experienced labour shortages in many industries. This was acute in rural areas already affected by demographic decline. Pandemic-related closures of schools and non-essential businesses, border shutdowns and travel restrictions had a negative impact on the economy immediately, and continued to have a lingering effect on the labour market. The province increased expenditures in support measures to help industries prepare for the transitional requirements of the workforce and to support under-represented groups to participate in the workforce. In addition, small businesses were aided by access to human resource assistance.

Prince Edward Island concentrated on collaboration with industry partners to identify possible solutions to address labour current shortages and to ensure future sustainability and growth in priority areas such as bioscience, manufacturing, healthcare and early childhood education. Approximately 70 employers and representatives of industry and business groups, service providers, and post-secondary institutions participated in the Stakeholder Consultation Roundtable on Workforce Needs to inform planning and development of labour market programs and service delivery to help address workforce needs, and to share best practices and explore innovative opportunities for collaboration.

Overarching themes emerged:

- alignment of flexible and relevant education and training to industry needs

- attraction, integration, and retention of newcomers, youth, and underrepresented groups

- importance of building HR capacity within PEI’s employers and industries

- evolution to flexible, modern workplaces that incorporate intergenerational and cultural awareness, accommodations, and development opportunities, and

- opportunities for pilots, flexible funding and supports that best reflect industry needs

While the province worked quickly with service providers and internal staff to transition to virtual and essential services, organizations needed time to respond to the changing conditions and requirements for public safety in group settings. This impacted programs’ participation rates.

Prince Edward Island invested in substantial IT system updates to improve the quantity and quality of data collected from clients, programs and outcomes from its LMDA-funded programs. Prince Edward Island redesigned its client management system and enhanced its reporting capabilities, allowing for better analysis and understanding of the barriers affecting clients, as well as the barriers leading to specific programming decisions.

3.2.3 Nova Scotia

In FY2021, $101.1M was provided through the Canada-Nova Scotia LMDA for training and employment supports to individuals and employers. More than 17,500 participants across the province received training and employment supports, including more than 8,000 participants who were receiving federal emergency income benefits (CERB or CRB). Almost 2,800 individuals gained employment after receiving LMDA-funded supports. In FY2021, the number of clients served decreased by 28%. For details, see annex A.

Labour shortages due to the absence of temporary foreign workers, and recruitment challenges in retail and healthcare affected key industries. The province introduced several targeted measures within the LMDA funding streams to address COVID-19 impacts and also carried out a series of system innovations and service enhancements.

Changes in Nova Scotia Works (NSW) service provision include new approaches to job fairs, quality assurance, diversity and inclusion, and the development of essential skills. There was new emphasis on proactive engagement and recruitment of potential users who most need services. Focus groups were held with African Nova Scotian youth to inform the application of an Afrocentric lens in programming planning, development, delivery, and evaluation. Through the NSW Diversity and Inclusion Initiative, 16 African Nova Scotians were hired to be trained as Career Practitioners and will work across the NSW system. Mentors from within the system are being trained to support the new hires.

Service providers continue to develop their cultural competences and their focus on social equity, diversity and inclusion when addressing barriers to employment.

Under the NSW Service Provider Incentive, the service-providing organization will receive additional operating budget funding where case-managed individuals are known to have found employment either immediately, at 24 weeks, or at 52 weeks of unemployment. The performance incentive schedule prioritizes underrepresented individuals such as African Nova Scotians, Indigenous participants, new immigrants, and persons with disabilities.

The province consulted extensively with stakeholders to better understand employer needs in the areas of recruitment, retention, and training, and to explore potential solutions. A new data collection and reporting process, and tools for NSW Employer Engagement Specialists resulted in quarterly narrative reports and dashboards on the trends, challenges, and successes of regional employers across the province. Sectoral/government working groups have been established to address labour shortages, support productivity improvement initiatives, online job fairs, and the creation, implementation, and delivery of online learning to meet the immediate needs of small businesses. Industry focussed projects include the Cape Breton Infrastructure Projects, partnering with the construction sector industry and diverse communities for jobs the local workforce.

3.2.4 New Brunswick

In FY2021, $111.5M was provided through the Canada-New Brunswick LMDA for training and employment supports to individuals and employers. More than 30,900 participants across the province received training and employment supports, including more than 15,700 participants who were receiving federal emergency income benefits (CERB or CRB). In FY2021, the total number of clients served in New Brunswick dropped by 28%. Around 6,800 individuals gained employment after receiving LMDA-funded supports. For details, see annex A.

New Brunswick continued to experience a high unemployment rate relative to the rest of Canada. COVID-19 exacerbated challenges related to slow population growth, an aging population and the net out-migration of youth and skilled workers. Over the next decade, 127,000 job vacancies are expected. New Brunswick continues to focus on attracting, retaining and educating a highly skilled workforce and in FY2021, redesigned its labour market programming to respond to evolving challenges and opportunities.

The province’s LMDA-funded recruitment supports included financial support for work placements, assisting with job postings, promoting and supporting the use of its newest job matching platform, JobMatchNB, as well as organizing local, provincial and national job fairs, referring to partnering departments to address international recruitment needs, and experiential education through FutureNB. LMDA-funded training was provided through the Labour Force Training program and referrals to Workplace Essential Skills training.

Employers benefited from funding for external HR expertise in areas such as strategic planning, development of policies and procedures, job analysis and coaching on cultural diversity and workplace culture. Employers are the target of a new service delivery approach which focuses on collaborative assessment of HR needs and flexible, customized solutions. Employers, job seekers and workers will benefit from a new Employer Directory, a new virtual job fair platform and better dissemination of relevant labour market information.

New Brunswick continued to provide client-focused wage subsidies to employers through Workplace Connections (WPC). Under WPC, a work placement is initiated as part of a job seeker’s employment action plan. While driven primarily by the needs of job seekers, they also meet employers’ recruitment needs identified through HR needs assessments and often result in long-term employment.

New Brunswick consulted extensively with stakeholders, including with Francophone groups, organisations serving persons with disabilities and the New Brunswick Multicultural Council Immigrant Settlement Agencies. Consultations with stakeholders serving persons with disabilities focused on a new outsourced service delivery model for target groups, scheduled for implementation in 2022.

3.2.5 Quebec

In FY2021, $706.5M was provided through the Canada-Quebec LMDA for training and employment supports to individuals and employers. More than 114,400 participants across the province received training and employment supports funded by the Canada-Quebec LMDA, including more than 43,300 participants who were receiving federal emergency income benefits (CERB or CRB). Almost 43,800 individuals gained employment after receiving LMDA-funded supports. In FY2021, the total number of clients served dropped by 54%. For details, see annex A.

As in other jurisdictions, COVID-19 had significant impacts as the intermittent shut-down of non-essential services to control the spread of the virus raised unemployment rates and reduced labour force participation. In response, Quebec established new activities to support businesses and individuals:

- a simple and free job placement service which allowed personalized research and optimal matching between businesses and job seekers

- the Programme d’actions concertées pour le maintien en emploi (PACME) to support businesses so that they can retain and train their workforce

- the Programme d’aide à la relance par l’augmentation de la formation (PARAF) which encouraged unemployed workers to upgrade their skills and retrain, in preparation for economic recovery, and

- a virtual forum on the requalification of workers with labour market partners on the actions to be implemented for a post-pandemic recovery

To ensure that it responds adequately and quickly to the needs of the labour market, Quebec leverages the Commission des partenaires du marché du travail (CPMT). The CPMT brings together employers, unions, education sector, and community organizations to work with the Minister of Labour, Employment and Social Solidarity to guide action on public employment services. This collaboration takes the form of an annual action plan for labour and employment. During the pandemic period, partners came together for a virtual forum on worker retraining. They also actively participated in the development and monitoring of the exceptional measures implemented by Quebec, including the PARAF.

While they still adhere to the direction of the national action plan, the regional branches of Services Quebec identify their contribution in their regional employment and workforce action plan, are autonomous in the implementation of labour market strategies and manage their own budgets. To adapt to the needs of regional labor markets, employment services may differ from one region to another, depending on the priorities and characteristics of the region. Public employment services are managed according to a results-based approach. This management method allows for the implementation of effective supports and the assessment of concrete results, particularly with regard to those who have benefited from public employment services and have consequently returned to work.

The province of Quebec also worked in partnership with specialized employability development organizations and economic organizations to complement the activities of public employment services, as well as to offer businesses and the public a variety of services based on their training needs. During the pandemic period, the province maintained its support to these organizations despite a significant drop in traffic.

3.2.6 Ontario

In FY2021, $741.3M was provided through the Canada-Ontario LMDA for training and employment supports to individuals and employers. More than 186,700 participants across the province received training and employment supports funded by the Canada-Ontario LMDA, including more than 77,400 participants who were receiving federal emergency income benefits (CERB or CRB). Almost 51,600 individuals gained employment after receiving LMDA-funded supports. The total number of clients served in Ontario decreased by 30% in FY2021. For details, see annex A.

The pandemic profoundly affected the Ontario job market and disrupted the way people work. As of March 2021, an estimated 215,000 Ontarians had been affected by job loss, work absence or significantly reduced work hours. COVID also accelerated longer-term economic changes caused by automation, international economic recovery, changes in investor confidence, shifts in business models and new business costs. The magnitude of employment challenges differed by sector and client group. Many Ontarians sought support from the federal government. More than 2.5 million Ontarians received CERB benefits beginning in March 2020.

While public health measures resulted in a substantial decrease in client intake and exit activity for Employment Ontario programs, throughout FY2021 the province engaged stakeholders to help inform a policy and program response to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as to address longer-term structural issues. For example, 40 providers in the SkillsAdvance Ontario program were engaged to assess the effects of COVID-19 on service delivery and to identify considerations and potential adjustments to support service delivery during and after the pandemic.

A key apprenticeship program supported by LMDA funding is the Apprenticeship Development Benefit, which provides financial assistance to EI-eligible apprentices who attend full-time in-class training. Assistance can be used to ease barriers to apprenticeship participation, including basic living expenses, dependent care, expenses for living away from home, and special assistance for persons with disabilities.

Several Ontario ministries sought feedback from Indigenous groups regarding employment and training programs across the province. During conversations regarding apprenticeship with the ministry and Youth Advisors, common themes expressed included:

- general lack of opportunity for Indigenous people to obtain the “hours” required to qualify as apprentices and/or journeypersons

- anti-Indigenous racism in the skilled trades

- barriers to Indigenous participation in the skilled trades including travel for apprentices from remote and rural communities and for youth without access to a car, and

- general lack of Indigenous people with skilled trades, carpenters, electricians, plumbers, construction craft workers, etc. available for projects in First Nations communities which makes it more difficult for youth in those communities to gain exposure to the trades

Ontario: Skilled Trades Strategy

In FY2021, Ontario began implementing a client-focused apprenticeship and skilled trades system through the Skilled Trades Strategy. The strategy is intended to modernize Ontario’s skilled trades and apprenticeship system and help enable the province’s economic recovery by breaking the stigma and supporting awareness of the skilled trades, simplifying the system and encouraging employer participation. A Skilled Trades Panel was established to capture industry perspectives from employers, tradespeople, unions, trainers, and apprentices on a new service delivery model.

Ontario also engaged with various stakeholders as part of a comprehensive review of its provincial workforce development and training system. In addition to stakeholder meetings, 3 bilingual surveys were distributed to service providers, employers and industrial partners, and learners currently participating in workforce development programs. The review aims to support programming to meet the evolving needs of Ontario’s jobseekers, workers and industries, and to develop Ontario’s first Workforce Development Action Plan.

Ontario’s goal is an efficient service delivery and outcomes-based system that meets the needs all job seekers, particularly those with a more tenuous labour market attachment, as well as employers and communities. As part of the transformation, the government integrated employment services from the Ontario Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services’ Social Assistance programs into the Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development’s Employment Ontario - Employment Service. In the transformed system, selected Service System Managers plan, design and deliver core employment service activities and specialized services for people with higher or more complex employment needs. Managers receive outcome-based funding for assisting clients to achieve sustainable employment outcomes across the spectrum of need and are also required to meet other key performance indicators.

Implementation of the integrated employment services system started with 3 prototype catchment areas in January 2020. In June 2021, the province-wide phased roll-out of the model was announced and will be implemented through a sequenced approach, starting with 4 additional Targeting Referral and Feedback (TRF) catchment areas in 2022.

3.2.7 Manitoba

In FY2021, $61.7M was provided through the Canada-Manitoba LMDA for training and employment supports to individuals and employers. More than 72,500 participants across the province received training and employment supports funded by the Canada-Manitoba LMDA, including more than 29,100 participants who were receiving federal emergency income benefits (CERB or CRB). Almost 4,800 individuals gained employment after receiving LMDA-funded supports. The total number of clients served in Manitoba decreased by 29% in FY2021. For details, see annex A.

As in other jurisdictions, the emergence of COVID-19 in Manitoba had a severe impact on the labour market. The intermittent closure of non-essential businesses and services to control the spread of the virus raised unemployment rates, reduced labour force participation and significantly reduced hours worked.

Throughout FY2021, most direct services through the 13 Manitoba Jobs and Skills Development Centres and contracted programming through community-based organizations shifted to alternate service delivery models. Manitoba consulted regularly with stakeholders whose operations were adversely impacted by the pandemic to inform the development and design of government relief and recovery supports and to address matters related to the public health orders.

Manitoba also held virtual meetings with its contracted disability service providers regarding the changes made to their programming as a result of COVID-19. Key themes in consultations included:

- impacts of COVID-19 and opportunities to support businesses, organizations and individuals with economic recovery

- engagement of underrepresented groups to fill employment opportunities and increase availability of skilled workers, including Indigenous peoples, persons with disabilities, and newcomers to Manitoba

- access to supports to facilitate success in training, education and the workplace and address barriers to participation, including financial supports and other wrap around services;

- improved alignment of education and training programming with the needs of the labour market, and

- creation of opportunities for Indigenous peoples to participate in the labour market and promote economic development opportunities in the north

Manitoba engaged across sectors, communities and regions of the province. These stakeholders identified key labour market barriers and opportunities, and informed annual planning priorities and employment programming. Following extensive engagement, the province officially launched its Skills, Talent and Knowledge Strategy to ensure Manitobans have the skills needed to rebound from the effects of the pandemic and support economic resilience and growth.

Manitoba implemented enhancements to its main IT systems to improve service level data collection and reporting functions related to service provider needs determination, support for continuous improvement, and labour market outcomes. A number of planned program evaluations and reviews were put on hold temporarily due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

3.2.8 Saskatchewan

In FY2021, $54.4M was provided through the Canada-Saskatchewan LMDA for training and employment supports to individuals and employers. More than 23,900 participants across the province received training and employment supports, including more than 8,900 participants who were receiving federal emergency income benefits (CERB or CRB). Around 6,900 individuals gained employment after receiving LMDA-funded supports. In FY2021, the total number of clients declined by 22%. For details, see annex A.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused labour market disruption, impacting all major sectors of the economy. Saskatchewan’s seasonally adjusted unemployment rate fluctuated from a high of 12.4% in May 2020 to 7.3% in March 2021 when employment in construction, health care and social assistance, and wholesale and retail trade sector returned to or exceeded pre-pandemic levels. Reduced hours of work and job shortfalls persisted in other sectors, particularly accommodation and food services, culture and recreation, and agriculture.

In response, Saskatchewan shifted its focus to help businesses avoid or mitigate the impact of layoffs and service providers were engaged to ensure business continuity plans were activated and service delivery was maintained through:

- transitioning to online service delivery, meeting the demand from individuals and businesses

- supporting community-based organizations and other third-party service delivery partners to convert career, employment, and training services to a virtual environment and to modify employment service centres

- incremental program investments to support post secondary institutions to continue addressing the training needs of Saskatchewan business and industry in the areas of greatest labour market demand

- expanded access to virtual reality technology to try out different occupations and support career decision-making for in-demand occupations

- outreach to create awareness around the availability of various supports in response to the pandemic, and

- identification of critical public services for employers and support to ensure a supply of qualified workers for these critical roles

Saskatchewan regularly engages and consults with clients, stakeholders and government partners to determine priorities and consider program design and service delivery improvements. In response to the issues raised in the course of outreach and consultations, Saskatchewan took the following actions:

- introduced new apprenticeship legislation and supporting regulatory framework

- supported employers in hiring essential staff through SaskJobs.ca, the National Job Bank and the Saskatchewan Immigrant Nominee Program

- worked with the Northern Labour Market Committee to align programs and services to the skill demand of northern industry

- made additional mid-year investments in programming including training for Indigenous health care workers and workers affected by the phase out of the coal industry, and

- through the Training Voucher Program, provided funding assistance to support participation in skills training for laid-off workers in sectors impacted by the pandemic

The province continued to offer the Enhanced Career Bridging program to help unemployed individuals gain skills necessary to participate in the changing world of work. Most participants are from under-represented groups. As of March 31, 2021, of the 57 participants who completed the program, 34 were employed, 8 went on to further training. Additionally, 27 individuals were still participating in the program.

3.2.9 Alberta

In FY2021, $192.4M was provided through the Canada-Alberta LMDA for training and employment supports to individuals and employers. More than 87,200 participants across the province received training and employment supports, including more than 39,600 participants who were receiving federal emergency income benefits (CERB or CRB). Almost 17,900 individuals gained employment after receiving LMDA-funded supports. For a fifth consecutive year, the total number of clients served in Alberta decreased. In FY2021, the year-over-year decline was 34%. For details, see annex A.

Alberta offers a range of programs through its LMDA. This includes a comprehensive suite of employment services, such as career planning, job search, job placement and labour market information, available through in-person, print and online services. Transition to Employment Services provide customized, work-directed services to help individuals acquire workplace and occupational skills to facilitate their rapid reattachment to the labour market.

Immigrant Bridging programs provide training for skilled immigrants with prior education and/or experience in a specific occupation to fill gaps in knowledge or skills necessary to gain employment in that occupation, or a related occupation. English as a Second Language training assists those individuals whose first language is other than English. Through is Occupational Training programs, Alberta offers work experience to participants, and its Integrated Training programs combine academic and general employability skills with occupation-related skills. A Living Allowance program provides participants in other Alberta labour market programs with the basic costs of maintaining their household while in training.

Most career planning and job search support services were provided remotely, via the Alberta Learning Information Service website and through Alberta Supports phone access. Workers in the retail, tourism, hospitality and aerospace sectors experienced near total business closures as a result of the pandemic. Workers in the transportation, energy and construction sectors were classified as essential, and while not as negatively impacted, they still experienced reduced activity. An increased reliance on technology to maintain business operations in the face of COVID-19 placed a spotlight on the importance of this industry to Alberta’s economic resilience.

In addition to delivering its ongoing suite of LMDA programs in FY2021, Alberta responded to the pandemic by programs to address high unemployment among youth and adults transitioning from one sector to another, by developing training for new occupations and for emerging industry sectors, and by supporting individuals looking work.

Alberta: Supports for Francophones

In July 2020, francophone career and employment services in downtown Calgary transitioned from a single stand-alone service provider to a model where French-language services are delivered as a part of the services offered in 3 locations across the city. An additional job placement service for French-speaking job seekers was added to the services available.

To ensure a seamless transition for services from the single location to 3 locations, meetings were held with francophone stakeholders (including Francophone Secretariat, Canadian Heritage, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, Cité des Rocheuses, and Conseil de développement économique de l'Alberta) in June, August and September 2020.

On the basis of consultations with frontline staff, community service providers and current contract holders, it was determined that existing employment supports with providers in northwest Alberta are sufficient to meet the current need of the francophone community in the North Zone.

Alberta regularly engaged stakeholders via the ministries that administer their labour market programs. The Ministry of Community and Social Services met civil society organizations to develop techniques that use the ministry’s procurement process to increase the value of career and employment programs and assist vulnerable Albertans to secure employment while supporting social enterprises.

Feedback from stakeholders is incorporated into the labour market information used to track current and evolving needs and to plan for needed supports. For example, Alberta’s new apprenticeship legislation will make apprenticeship education and the trades profession system more flexible, reduce red tape for apprentices, employers, educators and industry, and enable Alberta to respond quickly to changing needs.

3.2.10 British Columbia

In FY2021, $329.2M was provided through the Canada-British Columbia LMDA for training and employment supports to individuals and employers. More than 81,400 participants across the province received training and employment supports, including more than 35,700 participants who were receiving federal emergency income benefits (CERB or CRB). Close to 17,000 individuals gained employment after receiving LMDA-funded supports. For a seventh consecutive year, British Columbia served a decreasing total number of clients, dropping by 34% year-over-year. For details, see annex A.

Prior to FY2021, British Columbia’s economy was among the strongest in the country. The consequences the COVID-19 pandemic included the fastest and largest declines in employment and contraction in overall economic activity in the province’s history.

British Columbia consulted extensively with stakeholders and with service providers to understand the pandemic challenges clients faced and to inform the development of strategies to ensure services met evolving needs. With funding provided under the province’s LMDA:

- 102 WorkBC Centres quickly shifted to safe service delivery strategies, including adoption of innovative virtual service delivery, and physically distanced in-person service, by appointment

- facilitated forums helped service providers to discuss struggles and share best practices for working in the context of the pandemic

- clients did not experience a disruption in living supports due to COVID-19 while participating in services

- employer outreach prioritized sectors with severe staffing shortages in promoting promote WorkBC Centres as a source of talent

- community and Employer Partnerships provided targeted funding for projects that provided work experience and skills development to help unemployed individuals get and keep jobs and support businesses and communities with economic recovery, and

- community and Employer Partnerships project eligibility expansion was pursued, to include more persons with disabilities

Regular communications supported an understanding of challenges and collaboration on progress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Discussions included Indigenous service providers, persons with disabilities service delivery partners, Community Living BC and the Ministry of Health. Employers provided valuable insights into in-demand skills and workforce training gaps.

British Columbia engaged with large, provincial-footprint employers and facilitated connections between them to increase employment opportunities for individuals. Partnerships with organizations such as TC Energy and its prime contractors as well as BC Infrastructure Benefits helped to ensure service providers were aware of job opportunities on large infrastructure projects around the province. In 2020, a virtual roundtable discussion with employers from the province’s trucking sector identified skill gaps and barriers to entry into the industry. This work continued in 2021 with the province facilitating dialogue between WorkBC service providers and the BC Trucking Association HR Advisory committee. Opportunities for greater collaboration between trucking sector employers and WorkBC service providers remains a priority.

3.2.11 Northwest Territories

In FY2021, $4.9M was provided through the Canada-Northwest Territories LMDA for training and employment supports to individuals and employers. More than 390 participants across the territory received training and employment supports, including more than 125 participants who were receiving federal emergency income benefits (CERB or CRB). Around 150 individuals gained employment after receiving LMDA-funded supports. The Northwest Territories served a total of 248 clients in FY2021, a decline of 17% year-over-year. For details, see annex A.

In the Northwest Territories, as elsewhere in Canada in FY2021, most education and training courses either were delivered remotely or postponed. Since education and training providers were expected to deliver their programming almost entirely online, the territory aimed to ensure, to the greatest extent possible, that participating students and individuals in were not negatively impacted by these pandemic-related changes.

In addition to providing financial assistance for tuition, books, course materials, software and other fees, the LMDA funded a $750 Technology Grant for students in the Skills Development Program and the Self-Employment Program, to assist with the purchase of equipment required to learn remotely, such as computers, printers and scanners. Resources and materials outlining tips, tricks and best practices were developed to assist students in achieving success in online learning. Participants also were eligible for a new COVID-19 Support Grant, a monthly grant of $100 to assist with additional costs related to online learning and training, such as internet fees.

Northwest Territories’ suite of LMDA-funded programs includes its Skills Development Program which provides training opportunities to upgrade skills and knowledge and/or develop essential employability skills. Eligible activities include education and training programs that lead to labour market attachment. This may include academic upgrading, life skills, employment readiness programs, pre-employment training courses, skill-specific training programs and post-secondary programs.

The Self-Employment Program provides support to eligible clients with the opportunity to start a small business. This program provides supports for clients in assessing their business idea, their personal suitability, family issues, financial risks, and the resources available, or required, to be successful.

Through the Wage Subsidy Program, the territory provides support to an employer to hire and train Northwest Territories residents. This program is intended to provide work experience and training that will better enable clients to obtain meaningful long-term employment.

The Northwest Territories also uses its LMDA to fund Job Creation Partnerships that provide opportunities to improve the subsequent employment prospects of the clients. The program provides support for third party organizations to deliver community and regional activities that either include a work experience component or have a guarantee of meaningful employment at the end of the project. Work experience projects may also include a skills development component.

Finally, through its Strategic Workforce Initiatives, the Northwest Territories supports community partners in undertaking labour market activities that promote labour force development, workforce adjustments and effective human resources planning. Activities must address a community labour market need, and may include identifying economic trends, creating strategies, and initiating projects to develop a responsive local labour force.

The territory regularly engaged with employers, employee organizations, not-for-profit organizations, and community stakeholders to identify and discuss key labour market needs and priorities and how they could be supported and advanced through labour market programs and services. Consultations with underrepresented groups also included, but were not limited to, organizations serving persons with disabilities and official language minority communities; Indigenous organizations and Governments, and other Northwest Territories’ government departments.

From April to June 2020, Career Development Officers and Regional Managers of the 5 Regional Service Centres met with Designated Community Authorities, employers and organizations. The meetings and consultations were in-person and/or remotely, depending on the region and the level of access to a community. Some employers and community organizations were notified of the funding opportunities via emails, and offered an opportunity to meet and discuss further the program that fit their needs.

3.2.12 Yukon

In FY2021, $4.6M was provided through the Canada-Yukon LMDA for training and employment supports to individuals and employers. More than 220 participants across the territory received training and employment supports, including 14 participants who were receiving federal emergency income benefits (CERB or CRB). Almost 100 individuals gained employment after receiving LMDA-funded supports. The total number of clients served in Yukon decreased by 19% in FY2021. For details, see annex A.

Yukon began to feel the impacts of the pandemic in March 2020; the cancelation of the Arctic Winter Games, businesses closing and people working and studying from home. That month, a Business Advisory Council was established to gather and share information to guide the government’s COVID response. The flexibilities built into Yukon’s existing Building UP, Working UP, and Staffing UP programs meant that it was not necessary to design new programs to respond to COVID, however, Yukon did pivot its labour market strategy to respond to the ongoing feedback received from First Nations, industries and stakeholders.

Yukon continued to use its LMDA to invest in preserving jobs and preventing layoffs, especially for populations at-risk, or in circumstances that have a greater impact on the labour market. For example, in rural Yukon, if the only hotel or gas station closes due to reduced revenue, other businesses relying on those services are severely impacted, leading to additional job losses. With wage subsidies to prevent layoffs and keep businesses open, Yukon is ensuring communities are positioned to support their employers and to grow once the economy stabilizes. Through the Working UP program, Yukon increased participants’ foundational and vocational skills, and helped individuals advance along the employment continuum. Working UP focuses on individuals from under-represented groups.

Yukon consulted with stakeholders, for example, large employers and the Chambers of Commerce. Employers reported challenges recruiting staff with the skills and competencies they require, even in entry-level jobs. They also indicated they valued funding for third-party training for their staff. As a result, Yukon continued providing LMDA training funds in the Staffing UP program. To encourage new hires, especially for persons in underrepresented groups, Yukon provided incentives by funding a larger percentage of costs. Via the Staffing UP program, there was increased or sustained employment in the food production, tourism and hospitality sectors. Staffing UP helped to strengthen workplace skills, and to build or maintain attachment to the labour market during the pandemic.

Yukon’s Labour Market Framework guided its consultations with other governments, employers and organizations such as First Nation governments and service organizations, Chambers of Commerce, educational institutions, labour market service providers, unions and associations. The Framework’s 3 strategies have corresponding action plans: Labour Market Information, Recruitment and Employee Retention, and Comprehensive Skills and Trades Training. While not active, the principles of the framework are longstanding and continue to guide the Yukon’s work to strengthen the labour market. Renewing employer engagement and participation in strategic discussions remains a priority.

In March 2021, the Yukon Department of Economic Development released its Economic Resilience Plan: Building Yukon’s COVID-19 economic resiliency. This plan was informed by local industry organizations, the Business Advisory Council and experts from multiple sectors.

3.2.13 Nunavut

In FY2021, $4.0M was provided through the Canada-Nunavut LMDA for training and employment supports to individuals and employers. More than 720 participants across the territory received training and employment support, including 14 participants who were receiving federal emergency income benefits (CERB or CRB). Approximately 10 individuals gained employment after receiving LMDA-funded supports. The total number of clients served in Nunavut increased by 16% in FY2021. For details, see annex A.

The COVID-19 pandemic had 3 significant effects on LMDA-funded programs in Nunavut. First, the Territory’s ability to offer programming was curtailed as it became very difficult to persuade trainers to take up temporary residence in Nunavut to deliver much needed programming. Second, as a consequence of the uncertain course of the pandemic in Southern Canada and the need to protect Nunavut’s Elders and health care system from the worst effects of COVID-19, clients were urged to postpone training at southern-based institutions. Third, the creation of the CERB benefit diverted some potential clients from seeking EI-funded supports.

The COVID-19 pandemic also severely curtailed outreach and consultation activities in FY2021. The only significant activity was the conclusion of the public consultations on reform of the apprenticeship legislation and programming. The Territory conferred with:

- employers

- journeypersons

- apprentices

- career development and apprenticeship officers

- cities and hamlets

- Inuit organizations

- training partners and providers

- housing associations

- Nunavut Arctic College, and

- territorial government departments

The results were a complete overhaul of the apprenticeship and vocational certification legislation, and a redesign of support programs for apprentices. These changes will be gradually introduced in the next 2 fiscal years.

3.3. LMDA results

In this section

While unemployed individuals in receipt of EI benefits often have strong labour market attachment and recent work experience, many require targeted supports to quickly find new employment. Evidence shows that individuals who receive training and employment supports while receiving EI income benefits earn more and reduce their dependence on EI and social assistance. If provided to participants early, during the first 4 weeks of an EI claim, less intensive supports also have a positive impact on earnings and facilitate earlier returns to work. While approximately 25% of individuals take training while receiving EI benefits, one-quarter of those clients wait 6 months into their EI claim before starting training activities.

Recent evaluations have examined the effectiveness of LMDA-funded supports and sought out lessons for the design and delivery of particular measures. An incremental impact analysis examined unemployed individuals who participated in programs and services in the years 2010 to 2012 and cover a 5-year post-participation period up to 2017. Incremental impacts estimate the effects on employment, earnings, and collection of Social Assistance and EI due to participation, and are estimated by comparing participants’ experience to that of similar non-participants. The incremental impact analysis demonstrated that Employment Assistance Services (EAS), Skills Development (SD) and Targeted Wage Subsidies (TWS) resulted in improvements in labour market attachments overall. These supports have also been shown to benefit subgroups of participants: females, males, youth, older workers, Indigenous people, persons with disabilities, recent immigrants and visible minorities.

The first in-depth examination of the Labour Market Partnerships (LMP) Support Measure delivered under the LMDAs provides detailed descriptions of design and delivery, challenges and valuable lessons that will help inform future potential improvements. Key findings indicated funded organizations included non-profits, businesses/employers, educational institutions and training providers, municipal and local governments, and Indigenous organizations. Funded projects targeted current and/or forecasted skills and/or labour shortages. These projects also targeted specific populations, for example, women, youth, Indigenous people, newcomers, persons with disabilities and the self-employed.

Partnerships were established to support the delivery of the majority of projects and partners made a financial or in-kind contribution. PT departments and key informants explained that partners’ expertise, network and financial contribution are all essential to project implementation and success. For details, see annex C.

3.3.1 Repeat and combined use of skills developmentFootnote 3

A recent studyFootnote 4 examined the repeat use of SD benefits and how SD is used in combination with similar skills-oriented programs outside of the LMDA framework. The analysis indicated that repeated participation in skilled-related labour market programming occurs most frequently among SD-Apprentice clients, who typically participated in apprentice-oriented, rather than other skilled-related services:

- 18% of active and 19% of former claimant participants in SD-Apprentice were repeat users, compared to participants in SD-Regular programming, where less than 1% of active and former claimants were repeat users

- the typical active claimant among repeat SD-Apprentice users was male (97%), young (78%), and working in skilled crafts and trades (88%). Most of the SD-Apprentice repeaters had a college diploma (92%), and

- repeat SD-Apprentice users had a strong labour market attachment, with the highest average earnings (approximately $43,000) and no reliance on social assistance benefits 1 year before the participation

Participants with weak labour force attachment are expected to be rare among individuals who repeatedly engage in apprentice-oriented training.

3.3.2 Targeting, referral and feedback

In 2018, the LMDAs introduced a requirement for PTs to implement the federal Targeting, Referral and Feedback (TRF) solution to actively reach out to unemployed individuals to offer them employment programs and services available in their jurisdiction.

Through the TRF system, PTs set criteria to identify the new EI applicants in their jurisdiction, and select by location and demographic characteristics to match individuals with training and employment opportunities in their local labour markets.

Since the introduction of the TRF system, PTs have reached out to more than 2 and a half million EI applicants across Canada. In FY2021, half (1.5 million) of all EI applicants (3.1 million) were referred to PTs for outreach. For details, see annex D.

3.4. Pan-Canadian activities and the National Employment Service

In this section

The Government of Canada plays a leadership role in responding to challenges that extend beyond local and regional labour markets by delivering pan-Canadian activities. Pan-Canadian activities have 3 primary objectives:

- promoting an efficient and integrated national labour market and preserving and enhancing the Canadian economic union

- helping address common labour market challenges and priorities of international or national scope that transcend provincial and territorial borders, and

- promoting equality of opportunity for all Canadians with a focus on helping underrepresented groups reach their full potential in the Canadian labour market

These objectives are supported through 3 funding streams:

- Indigenous programming

- Enhancing Investments in Workplace Skills and Labour Market Information, and

- Supporting Agreements with PTs and Indigenous Organizations

In FY2021, expenditures on pan-Canadian activities totalled $144.3 million, compared to $147.3 million in FY1920. Pan-Canadian programming delivered through the Indigenous Skills and Employment Training Strategy (ISET) comprised $122.5 million of the total, followed by expenditures on Labour Market Partnerships at $19.6 million and Research and Innovation at $2.2 million.

3.4.1 Indigenous programming

With Indigenous partners, the Government is advancing reconciliation by creating more job training opportunities for Indigenous people and helping to help reduce the skills and employment gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. The ISET program was introduced in April 2019 as the successor to the Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy (ASETS).