Chapter 1: Labour market context

Official title: Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2021 and ending March 31, 2022: Chapter 1: Labour market context

In chapter 1

List of abbreviations

This is the complete list of abbreviations for the Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2021 and ending March 31, 2022.

Abbreviations

- AD

- Appeal Division

- ADR

- Alternative Dispute Resolution

- AI

- Artificial Intelligence

- ASETS

- Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy

- B

- Beneficiary

- B/C Ratio

- Benefits-to-Contributions ratio

- B/U

- Beneficiary-to-Unemployed (ratio)

- B/UC

- Beneficiary-to-Unemployed Contributor (ratio)

- BDM

- Benefits Delivery Modernization

- CAWS

- Client Access Workstation Services

- CCAJ

- Connecting Canadians with Available Jobs

- CCDA

- Canadian Council of Directors of Apprenticeship

- CCIS

- Corporate Client Information Service

- CEGEP

- College of General and Professional Teaching

- CEIC

- Canada Employment Insurance Commission

- CERB

- Canada Emergency Response Benefit

- CESB

- Canada Emergency Student Benefit

- CEWB

- Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy

- COEP

- Canadian Out of Employment Panel Survey

- COLS

- Community Outreach and Liaison Service

- CPP

- Canada Pension Plan

- CRA

- Canada Revenue Agency

- CRB

- Canada Recovery Benefit

- CRCB

- Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit

- CRF

- Consolidated Revenue Fund

- CRSB

- Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit

- CSO

- Citizen Service Officer

- CWLB

- Canada Worker Lockdown Benefit

- CX

- Client Experience

- EAS

- Employment Assistance Services

- EBSM

- Employment Benefits and Support Measures

- ECC

- Employer Contact Centre

- EI

- Employment Insurance

- EI-ERB

- Employment Insurance Emergency Response Benefit

- EICS

- Employment Insurance Coverage Survey

- EIPR

- Employment Insurance Premium Ratio

- eROE

- Electronic Record of Employment

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- eSIN

- Electronic Social Insurance Number

- FY

- Fiscal Year

- G7

- Group of Seven

- GDP

- Gross Domestic Product

- GIS

- Guaranteed Income Supplements

- HCCS

- Hosted Contact Centre Solution

- HR

- Human Resources

- ID

- Identification

- IQF

- Individual Quality Feedback

- IS

- Income Security

- ISET

- Indigenous Skills and Employment Training

- IVR

- Interactive Voice Response

- JCP

- Job Creation Partnerships

- LFS

- Labour Force Survey

- LMDA

- Labour Market Development Agreements

- LMI

- Labour Market Information

- LMP

- Labour Market Partnerships

- LWF

- Longitudinal Worker File

- MAR

- Monitoring and Assessment Report

- MBM

- Market Basket Measure

- MIE

- Maximum Insurable Earnings

- MSCA

- My Service Canada Account

- NAICS

- North American Industry Classification System

- NESI

- National Essential Skills Initiative

- NIS

- National Investigative Services

- NOM

- National Operating Model

- NQCP

- National Quality and Coaching Program

- OAG

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada

- OAS

- Old Age Security

- OSC

- Outreach Support Centre

- PAAR

- Payment Accuracy Review

- PEAQ

- Processing Excellence, Accuracy and Quality

- PPE

- Premium-paid eligible individuals

- PRAR

- Processing Accuracy Review

- PRP

- Premium Reduction Program

- PTs

- Provinces and Territories

- QPIP

- Quebec Parental Insurance Plan

- RAIS

- Registered Apprenticeship Information System

- RCMP

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- R&I

- Research and Innovation

- ROE

- Record of employment

- ROE Web

- Record of employment on the web

- RPA

- Robotics Process Automation

- SAT

- Secure Automated Transfer

- SCC

- Service Canada Centre

- SD

- Skills Development

- SD-A

- Skills Development – Apprenticeship

- SD-R

- Skills Development – Regular

- SDP

- Service Delivery Partner

- SEPH

- Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours

- SIN

- Social Insurance Number

- SIR

- Social Insurance Registry

- SRS

- Simple Random Sampling

- SST

- Social Security Tribunal

- STDP

- Short-term disability plan

- SUB

- Supplemental Unemployment Benefit

- TRF

- Targeting, Referral and Feedback

- TTY

- Teletypewriter

- TWS

- Targeted Wage Subsidies

- U

- Unemployed

- UC

- Unemployed contributor

- UV

- Unemployment-to-vacancy

- VBW

- Variable Best Weeks

- VER

- Variable Entrance Requirement

- VRI

- Video Remote Interpretation

- WCAG

- Web Content Accessibility Guidelines

- WWC

- Working While on Claim

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the economic situation and key labour market developments in Canada during the fiscal year (FY) beginning on April 1, 2021 and ending on March 31, 2022 (FY2122).Footnote 1 This is the same period for which this Report assesses the Employment Insurance (EI) program. Section 1.1 provides a general overview and context of the economic situation for FY2122, notably the impact of the subsequent waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, including public health measures and emergency programs that were put in place. Section 1.2 summarizes key labour market developments in the Canadian economy during the reporting period.Footnote 2 Section 1.3 concentrates on the evolution of regional labour market conditions. Definitions and more detailed statistical tables related to key labour market concepts discussed in the chapter can be found in Annex 1.

1.1 Economic overviewFootnote 3

The COVID-19 pandemic and public health measures in Canada

Over FY2122, with increased public immunity (through vaccination and infection) to the COVID-19 disease, governments and businesses in Canada began to ease up on public health restrictions and resume regular economic activities. During this period, the Canadian economy experienced a fast recovery overall with some intermittent fluctuations due to subsequent waves of COVID-19.

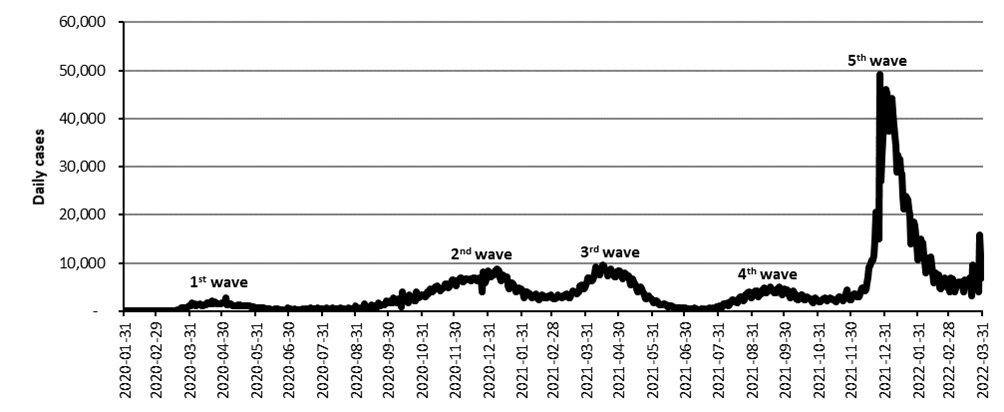

FY2122 started with the peak of the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2021 (consult Chart 1), which led to public health measures being tightened again in several provinces. In addition, temporary travel restrictions and the closure of the Canada-United States borderFootnote 4 were extended. At the same time, the national vaccination campaign was underway, and by August 2021, around 67% of eligible people in Canada had received 2 vaccine doses and more than 73% had received at least 1 dose.Footnote 5 This contributed to decisions by many of provincial governments to start to progressively ease public health measures in their jurisdictions, leading to more businesses re-opening.

When the fourth wave of the COVID-19 pandemic began in September 2021, close to 4 out of 5 eligible Canadians had already received 2 vaccine doses. Some public health measures were renewed at this time but their economic impact was milder than during previous waves. The fifth and strongest wave of COVID-19 began in early November 2021 with the emergence of the Omicron variant, leading to unprecedented numbers of COVID-19 infections in Canada. In late November, the Government of Canada adjusted international travel measures and some provinces renewed public health restrictions, including postponing return to school after the winter break, reducing indoor gathering capacity limits, and tightening restrictions on restaurants, bars, entertainment activities. These restrictions were gradually eased in early 2022 with this fifth wave coming under control.

Text description for chart 1

| Date | Daily cases |

|---|---|

| 2020-01-31 | - |

| 2020-02-08 | 3 |

| 2020-02-16 | 1 |

| 2020-02-21 | 1 |

| 2020-02-24 | 1 |

| 2020-02-25 | 1 |

| 2020-02-26 | 1 |

| 2020-02-27 | 1 |

| 2020-02-29 | 2 |

| 2020-03-01 | 9 |

| 2020-03-03 | 9 |

| 2020-03-05 | 12 |

| 2020-03-06 | 6 |

| 2020-03-07 | 6 |

| 2020-03-08 | 5 |

| 2020-03-09 | 15 |

| 2020-03-11 | 26 |

| 2020-03-12 | 38 |

| 2020-03-13 | 38 |

| 2020-03-15 | 54 |

| 2020-03-16 | 88 |

| 2020-03-17 | 99 |

| 2020-03-18 | 157 |

| 2020-03-19 | 276 |

| 2020-03-20 | 131 |

| 2020-03-21 | 367 |

| 2020-03-22 | 100 |

| 2020-03-23 | 620 |

| 2020-03-24 | 701 |

| 2020-03-25 | 617 |

| 2020-03-26 | 634 |

| 2020-03-27 | 646 |

| 2020-03-28 | 736 |

| 2020-03-29 | 833 |

| 2020-03-30 | 1,179 |

| 2020-03-31 | 1,111 |

| 2020-04-01 | 1,065 |

| 2020-04-02 | 1,670 |

| 2020-04-03 | 1,254 |

| 2020-04-04 | 1,367 |

| 2020-04-05 | 1,608 |

| 2020-04-06 | 1,155 |

| 2020-04-07 | 1,230 |

| 2020-04-08 | 1,392 |

| 2020-04-09 | 1,476 |

| 2020-04-10 | 1,383 |

| 2020-04-11 | 1,169 |

| 2020-04-12 | 1,066 |

| 2020-04-13 | 1,297 |

| 2020-04-14 | 1,383 |

| 2020-04-15 | 1,318 |

| 2020-04-16 | 1,711 |

| 2020-04-17 | 1,792 |

| 2020-04-18 | 1,469 |

| 2020-04-19 | 1,432 |

| 2020-04-20 | 2,045 |

| 2020-04-21 | 1,591 |

| 2020-04-22 | 1,769 |

| 2020-04-23 | 1,920 |

| 2020-04-24 | 1,778 |

| 2020-04-25 | 1,466 |

| 2020-04-26 | 1,541 |

| 2020-04-27 | 1,605 |

| 2020-04-28 | 1,526 |

| 2020-04-29 | 1,571 |

| 2020-04-30 | 1,639 |

| 2020-05-01 | 1,825 |

| 2020-05-02 | 1,653 |

| 2020-05-03 | 2,760 |

| 2020-05-04 | 1,298 |

| 2020-05-05 | 1,274 |

| 2020-05-06 | 1,449 |

| 2020-05-07 | 1,426 |

| 2020-05-08 | 1,512 |

| 2020-05-09 | 1,268 |

| 2020-05-10 | 1,146 |

| 2020-05-11 | 1,133 |

| 2020-05-12 | 1,175 |

| 2020-05-13 | 1,121 |

| 2020-05-14 | 1,211 |

| 2020-05-15 | 1,126 |

| 2020-05-16 | 1,251 |

| 2020-05-17 | 1,138 |

| 2020-05-18 | 1,070 |

| 2020-05-19 | 1,040 |

| 2020-05-20 | 1,011 |

| 2020-05-21 | 1,201 |

| 2020-05-22 | 1,156 |

| 2020-05-23 | 1,141 |

| 2020-05-24 | 1,078 |

| 2020-05-25 | 1,012 |

| 2020-05-26 | 936 |

| 2020-05-27 | 872 |

| 2020-05-28 | 993 |

| 2020-05-29 | 906 |

| 2020-05-30 | 772 |

| 2020-05-31 | 757 |

| 2020-06-01 | 758 |

| 2020-06-02 | 705 |

| 2020-06-03 | 675 |

| 2020-06-04 | 641 |

| 2020-06-05 | 609 |

| 2020-06-06 | 722 |

| 2020-06-07 | 642 |

| 2020-06-08 | 545 |

| 2020-06-09 | 409 |

| 2020-06-10 | 472 |

| 2020-06-11 | 405 |

| 2020-06-12 | 413 |

| 2020-06-13 | 467 |

| 2020-06-14 | 377 |

| 2020-06-15 | 360 |

| 2020-06-16 | 320 |

| 2020-06-17 | 386 |

| 2020-06-18 | 367 |

| 2020-06-19 | 409 |

| 2020-06-20 | 390 |

| 2020-06-21 | 318 |

| 2020-06-22 | 300 |

| 2020-06-23 | 326 |

| 2020-06-24 | 279 |

| 2020-06-25 | 380 |

| 2020-06-26 | 172 |

| 2020-06-27 | 238 |

| 2020-06-28 | 218 |

| 2020-06-29 | 668 |

| 2020-06-30 | 286 |

| 2020-07-01 | - |

| 2020-07-02 | 567 |

| 2020-07-03 | 319 |

| 2020-07-04 | 226 |

| 2020-07-05 | 219 |

| 2020-07-06 | 399 |

| 2020-07-07 | 232 |

| 2020-07-08 | 267 |

| 2020-07-09 | 371 |

| 2020-07-10 | 321 |

| 2020-07-11 | 221 |

| 2020-07-12 | 244 |

| 2020-07-13 | 565 |

| 2020-07-14 | 331 |

| 2020-07-15 | 341 |

| 2020-07-16 | 437 |

| 2020-07-17 | 405 |

| 2020-07-18 | 330 |

| 2020-07-19 | 339 |

| 2020-07-20 | 786 |

| 2020-07-21 | 573 |

| 2020-07-22 | 543 |

| 2020-07-23 | 432 |

| 2020-07-24 | 534 |

| 2020-07-25 | 350 |

| 2020-07-26 | 355 |

| 2020-07-27 | 686 |

| 2020-07-28 | 397 |

| 2020-07-29 | 412 |

| 2020-07-30 | 393 |

| 2020-07-31 | 513 |

| 2020-08-01 | 287 |

| 2020-08-02 | 285 |

| 2020-08-03 | 147 |

| 2020-08-04 | 761 |

| 2020-08-05 | 395 |

| 2020-08-06 | 374 |

| 2020-08-07 | 424 |

| 2020-08-08 | 236 |

| 2020-08-09 | 230 |

| 2020-08-10 | 681 |

| 2020-08-11 | 289 |

| 2020-08-12 | 423 |

| 2020-08-13 | 390 |

| 2020-08-14 | 418 |

| 2020-08-15 | 237 |

| 2020-08-16 | 198 |

| 2020-08-17 | 785 |

| 2020-08-18 | 282 |

| 2020-08-19 | 336 |

| 2020-08-20 | 383 |

| 2020-08-21 | 499 |

| 2020-08-22 | 257 |

| 2020-08-23 | 267 |

| 2020-08-24 | 750 |

| 2020-08-25 | 323 |

| 2020-08-26 | 448 |

| 2020-08-27 | 401 |

| 2020-08-28 | 492 |

| 2020-08-29 | 363 |

| 2020-08-30 | 267 |

| 2020-08-31 | 1,008 |

| 2020-09-01 | 477 |

| 2020-09-02 | 498 |

| 2020-09-03 | 570 |

| 2020-09-04 | 631 |

| 2020-09-05 | 371 |

| 2020-09-06 | 400 |

| 2020-09-07 | 247 |

| 2020-09-08 | 1,606 |

| 2020-09-09 | 546 |

| 2020-09-10 | 630 |

| 2020-09-11 | 702 |

| 2020-09-12 | 515 |

| 2020-09-13 | 518 |

| 2020-09-14 | 1,351 |

| 2020-09-15 | 793 |

| 2020-09-16 | 944 |

| 2020-09-17 | 1,120 |

| 2020-09-18 | 1,044 |

| 2020-09-19 | 863 |

| 2020-09-20 | 875 |

| 2020-09-21 | 1,766 |

| 2020-09-22 | 1,248 |

| 2020-09-23 | 1,090 |

| 2020-09-24 | 1,341 |

| 2020-09-25 | 1,362 |

| 2020-09-26 | 1,215 |

| 2020-09-27 | 1,454 |

| 2020-09-28 | 2,176 |

| 2020-09-29 | 1,660 |

| 2020-09-30 | 1,797 |

| 2020-10-01 | 1,777 |

| 2020-10-02 | 2,124 |

| 2020-10-03 | 1,812 |

| 2020-10-04 | 1,685 |

| 2020-10-05 | 2,804 |

| 2020-10-06 | 2,363 |

| 2020-10-07 | 1,800 |

| 2020-10-08 | 2,436 |

| 2020-10-09 | 2,558 |

| 2020-10-10 | 2,062 |

| 2020-10-11 | 1,685 |

| 2020-10-12 | 975 |

| 2020-10-13 | 4,042 |

| 2020-10-14 | 2,506 |

| 2020-10-15 | 2,345 |

| 2020-10-16 | 2,374 |

| 2020-10-17 | 2,215 |

| 2020-10-18 | 1,827 |

| 2020-10-19 | 3,289 |

| 2020-10-20 | 2,251 |

| 2020-10-21 | 2,672 |

| 2020-10-22 | 2,788 |

| 2020-10-23 | 2,584 |

| 2020-10-24 | 2,227 |

| 2020-10-25 | 2,145 |

| 2020-10-26 | 4,109 |

| 2020-10-27 | 2,674 |

| 2020-10-28 | 2,699 |

| 2020-10-29 | 2,956 |

| 2020-10-30 | 3,457 |

| 2020-10-31 | 3,445 |

| 2020-11-01 | 3,244 |

| 2020-11-02 | 3,273 |

| 2020-11-03 | 2,974 |

| 2020-11-04 | 3,283 |

| 2020-11-05 | 3,922 |

| 2020-11-06 | 3,669 |

| 2020-11-07 | 4,246 |

| 2020-11-08 | 4,594 |

| 2020-11-09 | 4,086 |

| 2020-11-10 | 4,302 |

| 2020-11-11 | 4,559 |

| 2020-11-12 | 4,981 |

| 2020-11-13 | 4,741 |

| 2020-11-14 | 5,267 |

| 2020-11-15 | 4,805 |

| 2020-11-16 | 4,802 |

| 2020-11-17 | 4,276 |

| 2020-11-18 | 4,641 |

| 2020-11-19 | 4,642 |

| 2020-11-20 | 4,968 |

| 2020-11-21 | 5,705 |

| 2020-11-22 | 5,418 |

| 2020-11-23 | 5,713 |

| 2020-11-24 | 4,889 |

| 2020-11-25 | 5,022 |

| 2020-11-26 | 5,631 |

| 2020-11-27 | 5,967 |

| 2020-11-28 | 6,496 |

| 2020-11-29 | 6,476 |

| 2020-11-30 | 6,103 |

| 2020-12-01 | 5,329 |

| 2020-12-02 | 6,307 |

| 2020-12-03 | 6,493 |

| 2020-12-04 | 6,300 |

| 2020-12-05 | 6,999 |

| 2020-12-06 | 6,987 |

| 2020-12-07 | 6,499 |

| 2020-12-08 | 5,981 |

| 2020-12-09 | 6,295 |

| 2020-12-10 | 6,739 |

| 2020-12-11 | 6,771 |

| 2020-12-12 | 6,710 |

| 2020-12-13 | 6,580 |

| 2020-12-14 | 6,731 |

| 2020-12-15 | 6,352 |

| 2020-12-16 | 6,416 |

| 2020-12-17 | 7,008 |

| 2020-12-18 | 6,707 |

| 2020-12-19 | 6,895 |

| 2020-12-20 | 6,693 |

| 2020-12-21 | 6,381 |

| 2020-12-22 | 6,196 |

| 2020-12-23 | 6,845 |

| 2020-12-24 | 6,796 |

| 2020-12-25 | 4,092 |

| 2020-12-26 | 8,129 |

| 2020-12-27 | 5,903 |

| 2020-12-28 | 5,790 |

| 2020-12-29 | 6,441 |

| 2020-12-30 | 7,477 |

| 2020-12-31 | 8,446 |

| 2021-01-01 | 7,512 |

| 2021-01-02 | 7,437 |

| 2021-01-03 | 7,137 |

| 2021-01-04 | 7,911 |

| 2021-01-05 | 7,447 |

| 2021-01-06 | 8,372 |

| 2021-01-07 | 8,340 |

| 2021-01-08 | 8,766 |

| 2021-01-09 | 8,665 |

| 2021-01-10 | 8,320 |

| 2021-01-11 | 6,849 |

| 2021-01-12 | 6,287 |

| 2021-01-13 | 6,860 |

| 2021-01-14 | 7,565 |

| 2021-01-15 | 6,809 |

| 2021-01-16 | 7,063 |

| 2021-01-17 | 7,080 |

| 2021-01-18 | 5,225 |

| 2021-01-19 | 4,679 |

| 2021-01-20 | 5,744 |

| 2021-01-21 | 5,955 |

| 2021-01-22 | 5,957 |

| 2021-01-23 | 5,651 |

| 2021-01-24 | 5,323 |

| 2021-01-25 | 4,630 |

| 2021-01-26 | 4,011 |

| 2021-01-27 | 4,204 |

| 2021-01-28 | 4,877 |

| 2021-01-29 | 4,690 |

| 2021-01-30 | 4,663 |

| 2021-01-31 | 4,397 |

| 2021-02-01 | 3,736 |

| 2021-02-02 | 2,828 |

| 2021-02-03 | 3,234 |

| 2021-02-04 | 4,083 |

| 2021-02-05 | 4,022 |

| 2021-02-06 | 3,729 |

| 2021-02-07 | 3,668 |

| 2021-02-08 | 2,967 |

| 2021-02-09 | 2,677 |

| 2021-02-10 | 3,185 |

| 2021-02-11 | 3,181 |

| 2021-02-12 | 3,143 |

| 2021-02-13 | 3,499 |

| 2021-02-14 | 2,862 |

| 2021-02-15 | 2,522 |

| 2021-02-16 | 2,387 |

| 2021-02-17 | 2,605 |

| 2021-02-18 | 3,314 |

| 2021-02-19 | 3,091 |

| 2021-02-20 | 3,219 |

| 2021-02-21 | 2,825 |

| 2021-02-22 | 2,878 |

| 2021-02-23 | 2,790 |

| 2021-02-24 | 2,896 |

| 2021-02-25 | 3,134 |

| 2021-02-26 | 3,219 |

| 2021-02-27 | 3,295 |

| 2021-02-28 | 2,852 |

| 2021-03-01 | 2,596 |

| 2021-03-02 | 2,457 |

| 2021-03-03 | 2,812 |

| 2021-03-04 | 2,832 |

| 2021-03-05 | 3,363 |

| 2021-03-06 | 2,876 |

| 2021-03-07 | 3,025 |

| 2021-03-08 | 3,037 |

| 2021-03-09 | 2,820 |

| 2021-03-10 | 3,223 |

| 2021-03-11 | 3,022 |

| 2021-03-12 | 3,459 |

| 2021-03-13 | 3,539 |

| 2021-03-14 | 3,445 |

| 2021-03-15 | 2,846 |

| 2021-03-16 | 2,819 |

| 2021-03-17 | 3,384 |

| 2021-03-18 | 3,599 |

| 2021-03-19 | 4,214 |

| 2021-03-20 | 4,010 |

| 2021-03-21 | 3,866 |

| 2021-03-22 | 3,775 |

| 2021-03-23 | 3,606 |

| 2021-03-24 | 4,041 |

| 2021-03-25 | 5,200 |

| 2021-03-26 | 5,095 |

| 2021-03-27 | 5,364 |

| 2021-03-28 | 5,126 |

| 2021-03-29 | 4,574 |

| 2021-03-30 | 4,878 |

| 2021-03-31 | 5,513 |

| 2021-04-01 | 5,805 |

| 2021-04-02 | 6,921 |

| 2021-04-03 | 6,822 |

| 2021-04-04 | 6,448 |

| 2021-04-05 | 6,267 |

| 2021-04-06 | 6,520 |

| 2021-04-07 | 7,146 |

| 2021-04-08 | 7,995 |

| 2021-04-09 | 9,243 |

| 2021-04-10 | 8,542 |

| 2021-04-11 | 8,656 |

| 2021-04-12 | 8,539 |

| 2021-04-13 | 7,542 |

| 2021-04-14 | 8,598 |

| 2021-04-15 | 9,570 |

| 2021-04-16 | 9,341 |

| 2021-04-17 | 8,867 |

| 2021-04-18 | 8,524 |

| 2021-04-19 | 8,311 |

| 2021-04-20 | 7,275 |

| 2021-04-21 | 8,419 |

| 2021-04-22 | 8,381 |

| 2021-04-23 | 8,738 |

| 2021-04-24 | 8,305 |

| 2021-04-25 | 7,829 |

| 2021-04-26 | 7,203 |

| 2021-04-27 | 7,069 |

| 2021-04-28 | 7,749 |

| 2021-04-29 | 8,343 |

| 2021-04-30 | 8,340 |

| 2021-05-01 | 8,450 |

| 2021-05-02 | 7,828 |

| 2021-05-03 | 7,565 |

| 2021-05-04 | 6,688 |

| 2021-05-05 | 7,390 |

| 2021-05-06 | 8,001 |

| 2021-05-07 | 7,826 |

| 2021-05-08 | 7,398 |

| 2021-05-09 | 7,297 |

| 2021-05-10 | 6,338 |

| 2021-05-11 | 5,382 |

| 2021-05-12 | 6,212 |

| 2021-05-13 | 6,619 |

| 2021-05-14 | 6,000 |

| 2021-05-15 | 5,710 |

| 2021-05-16 | 5,396 |

| 2021-05-17 | 4,588 |

| 2021-05-18 | 4,034 |

| 2021-05-19 | 4,247 |

| 2021-05-20 | 5,052 |

| 2021-05-21 | 4,682 |

| 2021-05-22 | 4,000 |

| 2021-05-23 | 3,738 |

| 2021-05-24 | 3,151 |

| 2021-05-25 | 2,502 |

| 2021-05-26 | 2,592 |

| 2021-05-27 | 2,965 |

| 2021-05-28 | 3,204 |

| 2021-05-29 | 2,718 |

| 2021-05-30 | 2,473 |

| 2021-05-31 | 2,109 |

| 2021-06-01 | 1,638 |

| 2021-06-02 | 2,062 |

| 2021-06-03 | 2,169 |

| 2021-06-04 | 2,060 |

| 2021-06-05 | 1,887 |

| 2021-06-06 | 1,521 |

| 2021-06-07 | 1,232 |

| 2021-06-08 | 1,268 |

| 2021-06-09 | 1,403 |

| 2021-06-10 | 1,479 |

| 2021-06-11 | 1,425 |

| 2021-06-12 | 1,385 |

| 2021-06-13 | 1,233 |

| 2021-06-14 | 949 |

| 2021-06-15 | 807 |

| 2021-06-16 | 1,048 |

| 2021-06-17 | 1,107 |

| 2021-06-18 | 1,012 |

| 2021-06-19 | 959 |

| 2021-06-20 | 802 |

| 2021-06-21 | 560 |

| 2021-06-22 | 621 |

| 2021-06-23 | 725 |

| 2021-06-24 | 708 |

| 2021-06-25 | 668 |

| 2021-06-26 | 668 |

| 2021-06-27 | 505 |

| 2021-06-28 | 660 |

| 2021-06-29 | 602 |

| 2021-06-30 | 548 |

| 2021-07-01 | 604 |

| 2021-07-02 | 428 |

| 2021-07-03 | 416 |

| 2021-07-04 | 524 |

| 2021-07-05 | 379 |

| 2021-07-06 | 438 |

| 2021-07-07 | 554 |

| 2021-07-08 | 567 |

| 2021-07-09 | 770 |

| 2021-07-10 | 391 |

| 2021-07-11 | 475 |

| 2021-07-12 | 272 |

| 2021-07-13 | 336 |

| 2021-07-14 | 381 |

| 2021-07-15 | 425 |

| 2021-07-16 | 397 |

| 2021-07-17 | 380 |

| 2021-07-18 | 498 |

| 2021-07-19 | 265 |

| 2021-07-20 | 339 |

| 2021-07-21 | 400 |

| 2021-07-22 | 570 |

| 2021-07-23 | 618 |

| 2021-07-24 | 517 |

| 2021-07-25 | 675 |

| 2021-07-26 | 436 |

| 2021-07-27 | 578 |

| 2021-07-28 | 765 |

| 2021-07-29 | 894 |

| 2021-07-30 | 907 |

| 2021-07-31 | 769 |

| 2021-08-01 | 1,086 |

| 2021-08-02 | 701 |

| 2021-08-03 | 737 |

| 2021-08-04 | 958 |

| 2021-08-05 | 1,447 |

| 2021-08-06 | 1,520 |

| 2021-08-07 | 1,367 |

| 2021-08-08 | 1,810 |

| 2021-08-09 | 1,209 |

| 2021-08-10 | 1,346 |

| 2021-08-11 | 1,861 |

| 2021-08-12 | 2,141 |

| 2021-08-13 | 2,416 |

| 2021-08-14 | 2,259 |

| 2021-08-15 | 1,885 |

| 2021-08-16 | 1,979 |

| 2021-08-17 | 1,780 |

| 2021-08-18 | 2,418 |

| 2021-08-19 | 2,732 |

| 2021-08-20 | 2,962 |

| 2021-08-21 | 2,878 |

| 2021-08-22 | 2,843 |

| 2021-08-23 | 2,058 |

| 2021-08-24 | 2,333 |

| 2021-08-25 | 3,326 |

| 2021-08-26 | 3,364 |

| 2021-08-27 | 3,768 |

| 2021-08-28 | 3,918 |

| 2021-08-29 | 3,167 |

| 2021-08-30 | 2,735 |

| 2021-08-31 | 2,909 |

| 2021-09-01 | 3,838 |

| 2021-09-02 | 4,048 |

| 2021-09-03 | 4,161 |

| 2021-09-04 | 4,023 |

| 2021-09-05 | 4,134 |

| 2021-09-06 | 2,958 |

| 2021-09-07 | 3,319 |

| 2021-09-08 | 3,641 |

| 2021-09-09 | 4,178 |

| 2021-09-10 | 4,628 |

| 2021-09-11 | 4,861 |

| 2021-09-12 | 4,225 |

| 2021-09-13 | 3,897 |

| 2021-09-14 | 4,044 |

| 2021-09-15 | 4,283 |

| 2021-09-16 | 4,689 |

| 2021-09-17 | 5,094 |

| 2021-09-18 | 4,536 |

| 2021-09-19 | 4,335 |

| 2021-09-20 | 3,857 |

| 2021-09-21 | 3,818 |

| 2021-09-22 | 3,852 |

| 2021-09-23 | 4,618 |

| 2021-09-24 | 4,605 |

| 2021-09-25 | 4,952 |

| 2021-09-26 | 4,333 |

| 2021-09-27 | 4,279 |

| 2021-09-28 | 3,488 |

| 2021-09-29 | 4,278 |

| 2021-09-30 | 4,588 |

| 2021-10-01 | 4,417 |

| 2021-10-02 | 4,427 |

| 2021-10-03 | 3,634 |

| 2021-10-04 | 3,403 |

| 2021-10-05 | 2,814 |

| 2021-10-06 | 3,716 |

| 2021-10-07 | 4,100 |

| 2021-10-08 | 4,128 |

| 2021-10-09 | 3,701 |

| 2021-10-10 | 3,530 |

| 2021-10-11 | 2,657 |

| 2021-10-12 | 2,323 |

| 2021-10-13 | 2,640 |

| 2021-10-14 | 3,193 |

| 2021-10-15 | 3,438 |

| 2021-10-16 | 3,347 |

| 2021-10-17 | 2,894 |

| 2021-10-18 | 2,272 |

| 2021-10-19 | 2,257 |

| 2021-10-20 | 2,642 |

| 2021-10-21 | 2,894 |

| 2021-10-22 | 2,762 |

| 2021-10-23 | 2,551 |

| 2021-10-24 | 2,280 |

| 2021-10-25 | 1,856 |

| 2021-10-26 | 1,773 |

| 2021-10-27 | 2,496 |

| 2021-10-28 | 2,666 |

| 2021-10-29 | 2,592 |

| 2021-10-30 | 2,375 |

| 2021-10-31 | 2,056 |

| 2021-11-01 | 1,937 |

| 2021-11-02 | 1,853 |

| 2021-11-03 | 2,224 |

| 2021-11-04 | 2,577 |

| 2021-11-05 | 2,533 |

| 2021-11-06 | 2,754 |

| 2021-11-07 | 2,442 |

| 2021-11-08 | 2,138 |

| 2021-11-09 | 2,387 |

| 2021-11-10 | 2,601 |

| 2021-11-11 | 2,716 |

| 2021-11-12 | 2,628 |

| 2021-11-13 | 2,638 |

| 2021-11-14 | 2,310 |

| 2021-11-15 | 2,171 |

| 2021-11-16 | 1,915 |

| 2021-11-17 | 2,422 |

| 2021-11-18 | 2,754 |

| 2021-11-19 | 2,875 |

| 2021-11-20 | 2,895 |

| 2021-11-21 | 2,461 |

| 2021-11-22 | 2,305 |

| 2021-11-23 | 2,235 |

| 2021-11-24 | 2,606 |

| 2021-11-25 | 2,878 |

| 2021-11-26 | 4,357 |

| 2021-11-27 | 3,020 |

| 2021-11-28 | 2,619 |

| 2021-11-29 | 2,332 |

| 2021-11-30 | 2,352 |

| 2021-12-01 | 3,146 |

| 2021-12-02 | 3,222 |

| 2021-12-03 | 3,497 |

| 2021-12-04 | 3,608 |

| 2021-12-05 | 3,401 |

| 2021-12-06 | 2,876 |

| 2021-12-07 | 2,967 |

| 2021-12-08 | 3,530 |

| 2021-12-09 | 4,258 |

| 2021-12-10 | 4,756 |

| 2021-12-11 | 4,929 |

| 2021-12-12 | 4,306 |

| 2021-12-13 | 4,149 |

| 2021-12-14 | 4,388 |

| 2021-12-15 | 5,875 |

| 2021-12-16 | 7,125 |

| 2021-12-17 | 9,173 |

| 2021-12-18 | 9,402 |

| 2021-12-19 | 10,605 |

| 2021-12-20 | 10,673 |

| 2021-12-21 | 11,679 |

| 2021-12-22 | 15,002 |

| 2021-12-23 | 20,693 |

| 2021-12-24 | 15,969 |

| 2021-12-25 | 17,402 |

| 2021-12-26 | 15,024 |

| 2021-12-27 | 49,148 |

| 2021-12-28 | 27,053 |

| 2021-12-29 | 32,120 |

| 2021-12-30 | 40,002 |

| 2021-12-31 | 45,837 |

| 2022-01-01 | 46,118 |

| 2022-01-02 | 45,329 |

| 2022-01-03 | 38,077 |

| 2022-01-04 | 37,408 |

| 2022-01-05 | 39,433 |

| 2022-01-06 | 43,137 |

| 2022-01-07 | 44,331 |

| 2022-01-08 | 41,056 |

| 2022-01-09 | 38,588 |

| 2022-01-10 | 34,174 |

| 2022-01-11 | 28,949 |

| 2022-01-12 | 32,475 |

| 2022-01-13 | 31,357 |

| 2022-01-14 | 31,670 |

| 2022-01-15 | 28,896 |

| 2022-01-16 | 28,538 |

| 2022-01-17 | 23,606 |

| 2022-01-18 | 21,163 |

| 2022-01-19 | 22,297 |

| 2022-01-20 | 23,949 |

| 2022-01-21 | 23,161 |

| 2022-01-22 | 21,301 |

| 2022-01-23 | 19,993 |

| 2022-01-24 | 13,863 |

| 2022-01-25 | 14,165 |

| 2022-01-26 | 18,489 |

| 2022-01-27 | 18,497 |

| 2022-01-28 | 17,695 |

| 2022-01-29 | 15,520 |

| 2022-01-30 | 13,561 |

| 2022-01-31 | 10,721 |

| 2022-02-01 | 11,077 |

| 2022-02-02 | 15,097 |

| 2022-02-03 | 14,215 |

| 2022-02-04 | 14,122 |

| 2022-02-05 | 11,500 |

| 2022-02-06 | 10,311 |

| 2022-02-07 | 7,877 |

| 2022-02-08 | 8,853 |

| 2022-02-09 | 11,139 |

| 2022-02-10 | 10,632 |

| 2022-02-11 | 10,190 |

| 2022-02-12 | 11,205 |

| 2022-02-13 | 7,811 |

| 2022-02-14 | 5,801 |

| 2022-02-15 | 6,034 |

| 2022-02-16 | 8,016 |

| 2022-02-17 | 7,583 |

| 2022-02-18 | 7,023 |

| 2022-02-19 | 7,545 |

| 2022-02-20 | 4,803 |

| 2022-02-21 | 4,729 |

| 2022-02-22 | 5,555 |

| 2022-02-23 | 6,374 |

| 2022-02-24 | 6,927 |

| 2022-02-25 | 6,742 |

| 2022-02-26 | 6,224 |

| 2022-02-27 | 4,795 |

| 2022-02-28 | 5,902 |

| 2022-03-01 | 3,921 |

| 2022-03-02 | 6,907 |

| 2022-03-03 | 5,995 |

| 2022-03-04 | 6,769 |

| 2022-03-05 | 5,436 |

| 2022-03-06 | 4,092 |

| 2022-03-07 | 5,654 |

| 2022-03-08 | 5,925 |

| 2022-03-09 | 6,034 |

| 2022-03-10 | 5,686 |

| 2022-03-11 | 6,169 |

| 2022-03-12 | 5,179 |

| 2022-03-13 | 5,023 |

| 2022-03-14 | 3,939 |

| 2022-03-15 | 6,427 |

| 2022-03-16 | 5,856 |

| 2022-03-17 | 5,631 |

| 2022-03-18 | 5,284 |

| 2022-03-19 | 6,968 |

| 2022-03-20 | 5,413 |

| 2022-03-21 | 3,142 |

| 2022-03-22 | 9,562 |

| 2022-03-23 | 5,207 |

| 2022-03-24 | 5,928 |

| 2022-03-25 | 5,951 |

| 2022-03-26 | 7,930 |

| 2022-03-27 | 7,051 |

| 2022-03-28 | 4,018 |

| 2022-03-29 | 15,847 |

| 2022-03-30 | 6,880 |

| 2022-03-31 | 7,127 |

- Source: Public Health Agency of Canada

Global economic development

On February 24, 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The impacts have been felt throughout the world’s economy including Canada and many of Canada’s important trading partners.Footnote 6 International supply chains were interrupted and energy and food prices surged, resulting in global inflation rates surging to multi-decade highs in the second half of 2022 (consult Chart 4, for Canada) and causing uncertainty in the economic development of many countries, including Canada.

Canadian economic context in FY2122

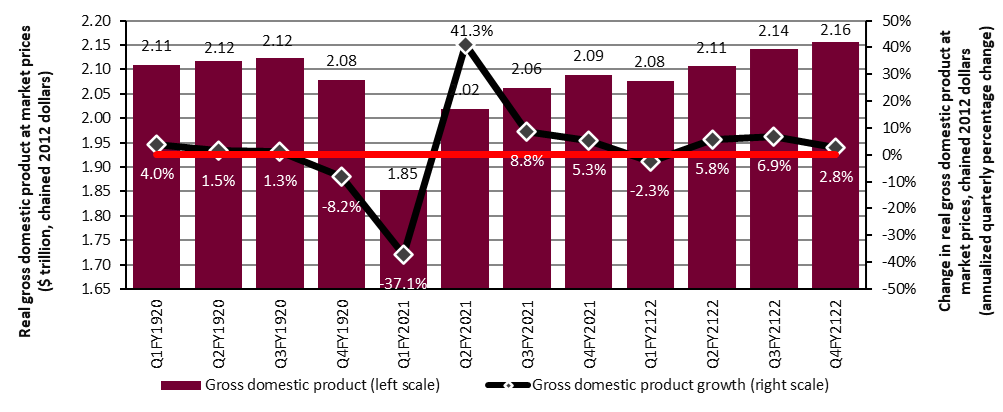

During FY2122, the global economy had been recovering strongly from the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in advanced economies. In Canada, real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased by 5.7% compared to FY2021.Footnote 7 By the end of FY2122, the real GDP level was 3.2% higher than its pre-pandemic level.

Looking at quarterly movement, the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic slowed economic growth in the first quarter of FY2122 (-2.3%), but a robust growth resumed in the 2 quarters that followed (+5.8% and +6.9%) (consult Chart 2). While the Canadian economy slowed again in the last quarter of FY2122 (+2.8%) due to the reintroduction of public health measures in response to the Omicron variant and widespread worker absences due to the disease, the economic impact was less severe than during previous waves.

Text description for chart 2

| Quarter | Gross domestic product (left scale) | Gross domestic product growth (right scale) |

|---|---|---|

| Q1FY1920 | $2.11 | 4.0% |

| Q2FY1920 | $2.12 | 1.5% |

| Q3FY1920 | $2.12 | 1.3% |

| Q4FY1920 | $2.08 | -8.2% |

| Q1FY2021 | $1.85 | -37.1% |

| Q2FY2021 | $2.02 | 41.3% |

| Q3FY2021 | $2.06 | 8.8% |

| Q4FY2021 | $2.09 | 5.3% |

| Q1FY2122 | $2.08 | -2.3% |

| Q2FY2122 | $2.11 | 5.8% |

| Q3FY2122 | $2.14 | 6.9% |

| Q4FY2122 | $2.16 | 2.8% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0104-01.

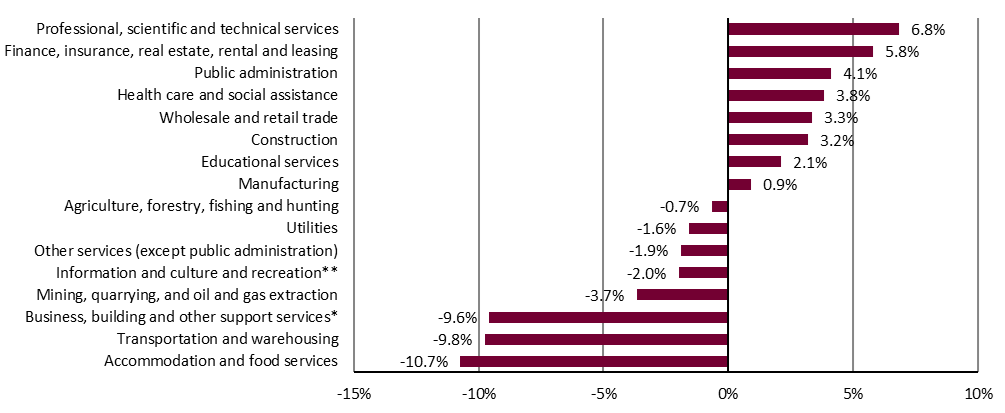

Over FY2122, recovery remained uneven across sectors (consult Chart 3). In March 2022, 8 out of 16 main industries had fully recovered output losses stemming from the first months of the COVID‑19 pandemic. Among these, Professional, scientific and technical services (+6.8%); Finance insurance, real estate, rental and leasing (+5.8%); and Public administration (+4.1%) saw the highest growth relative to February 2020. Among the remaining 8 industries, output was still lagging compared to their pre-pandemic levels. Accommodation and food services, Transportation and warehousing, and Business, building and other support services were the most affected compared to February 2020, with growth of -10.7%, ‑9.8%, and -9.6%. These 3 sectors were affected by the continuous supply chain disruptions,Footnote 8 and changes in work patterns (such as teleworking arrangements).

Text description for chart 3

| Industry | Change in real GDP |

|---|---|

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 6.8% |

| Finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing | 5.8% |

| Public administration | 4.1% |

| Health care and social assistance | 3.8% |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 3.3% |

| Construction | 3.2% |

| Educational services | 2.1% |

| Manufacturing | 0.9% |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | -0.7% |

| Utilities | -1.6% |

| Other services (except public administration) | -1.9% |

| Information and culture and recreation** | -2.0% |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction | -3.7% |

| Business, building and other support services* | -9.6% |

| Transportation and warehousing | -9.8% |

| Accommodation and food services | -10.7% |

- * Includes management of companies and enterprises and administrative and support, waste management and remediation services.

- ** Includes information and cultural industries and arts, entertainment and recreation industries.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0434-01.

Faced with high demand, supply chain disruptions and labour shortages in FY2122, Canadian firms passed the higher costs of production onto consumers. The war in Ukraine also added to inflationary pressure through increased prices for energy and other commodities and pre-existing supply chain disruptions. The inflation rate rose in FY2122, especially in the last two quarters, well above its target level of 2% set by the Bank of Canada. The year-over-year rate of increase of the all-item Consumer Price Index (CPI), or the CPI inflation, rose from 2.2% in March 2021 to 6.7% in March 2022, comparable to the highs experienced in early 1990s (consult Chart 4). Footnote 9 In response to rising inflation and inflation expectations, the Bank of Canada increased interest rates in March 2022 for the first time since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, a process that was continued for the remainder of the year 2022.

Text description for chart 4

| Month | 12-month CPI change rate |

|---|---|

| Jan-1996 | 1.6% |

| Feb-1996 | 1.3% |

| Mar-1996 | 1.5% |

| Apr-1996 | 1.4% |

| May-1996 | 1.5% |

| Jun-1996 | 1.5% |

| Jul-1996 | 1.3% |

| Aug-1996 | 1.5% |

| Sep-1996 | 1.5% |

| Oct-1996 | 1.8% |

| Nov-1996 | 1.9% |

| Dec-1996 | 2.2% |

| Jan-1997 | 2.2% |

| Feb-1997 | 2.3% |

| Mar-1997 | 1.9% |

| Apr-1997 | 1.7% |

| May-1997 | 1.5% |

| Jun-1997 | 1.7% |

| Jul-1997 | 1.7% |

| Aug-1997 | 1.8% |

| Sep-1997 | 1.7% |

| Oct-1997 | 1.5% |

| Nov-1997 | 0.9% |

| Dec-1997 | 0.8% |

| Jan-1998 | 1.1% |

| Feb-1998 | 1.0% |

| Mar-1998 | 1.0% |

| Apr-1998 | 0.9% |

| May-1998 | 1.1% |

| Jun-1998 | 1.0% |

| Jul-1998 | 1.0% |

| Aug-1998 | 0.9% |

| Sep-1998 | 0.7% |

| Oct-1998 | 1.1% |

| Nov-1998 | 1.2% |

| Dec-1998 | 1.0% |

| Jan-1999 | 0.7% |

| Feb-1999 | 0.7% |

| Mar-1999 | 1.0% |

| Apr-1999 | 1.6% |

| May-1999 | 1.5% |

| Jun-1999 | 1.6% |

| Jul-1999 | 1.9% |

| Aug-1999 | 2.1% |

| Sep-1999 | 2.6% |

| Oct-1999 | 2.3% |

| Nov-1999 | 2.2% |

| Dec-1999 | 2.6% |

| Jan-2000 | 2.2% |

| Feb-2000 | 2.7% |

| Mar-2000 | 3.0% |

| Apr-2000 | 2.2% |

| May-2000 | 2.4% |

| Jun-2000 | 2.8% |

| Jul-2000 | 2.9% |

| Aug-2000 | 2.6% |

| Sep-2000 | 2.7% |

| Oct-2000 | 2.8% |

| Nov-2000 | 3.2% |

| Dec-2000 | 3.2% |

| Jan-2001 | 3.0% |

| Feb-2001 | 2.9% |

| Mar-2001 | 2.4% |

| Apr-2001 | 3.5% |

| May-2001 | 3.9% |

| Jun-2001 | 3.4% |

| Jul-2001 | 2.7% |

| Aug-2001 | 2.8% |

| Sep-2001 | 2.6% |

| Oct-2001 | 1.9% |

| Nov-2001 | 0.6% |

| Dec-2001 | 0.7% |

| Jan-2002 | 1.3% |

| Feb-2002 | 1.4% |

| Mar-2002 | 1.9% |

| Apr-2002 | 1.7% |

| May-2002 | 1.1% |

| Jun-2002 | 1.2% |

| Jul-2002 | 2.1% |

| Aug-2002 | 2.5% |

| Sep-2002 | 2.3% |

| Oct-2002 | 3.2% |

| Nov-2002 | 4.4% |

| Dec-2002 | 3.8% |

| Jan-2003 | 4.5% |

| Feb-2003 | 4.7% |

| Mar-2003 | 4.2% |

| Apr-2003 | 2.9% |

| May-2003 | 2.8% |

| Jun-2003 | 2.6% |

| Jul-2003 | 2.1% |

| Aug-2003 | 2.0% |

| Sep-2003 | 2.2% |

| Oct-2003 | 1.6% |

| Nov-2003 | 1.6% |

| Dec-2003 | 2.1% |

| Jan-2004 | 1.3% |

| Feb-2004 | 0.7% |

| Mar-2004 | 0.8% |

| Apr-2004 | 1.7% |

| May-2004 | 2.4% |

| Jun-2004 | 2.5% |

| Jul-2004 | 2.3% |

| Aug-2004 | 1.8% |

| Sep-2004 | 1.8% |

| Oct-2004 | 2.3% |

| Nov-2004 | 2.4% |

| Dec-2004 | 2.1% |

| Jan-2005 | 1.9% |

| Feb-2005 | 2.1% |

| Mar-2005 | 2.3% |

| Apr-2005 | 2.4% |

| May-2005 | 1.6% |

| Jun-2005 | 1.7% |

| Jul-2005 | 2.0% |

| Aug-2005 | 2.6% |

| Sep-2005 | 3.2% |

| Oct-2005 | 2.6% |

| Nov-2005 | 2.0% |

| Dec-2005 | 2.1% |

| Jan-2006 | 2.8% |

| Feb-2006 | 2.2% |

| Mar-2006 | 2.2% |

| Apr-2006 | 2.4% |

| May-2006 | 2.8% |

| Jun-2006 | 2.4% |

| Jul-2006 | 2.3% |

| Aug-2006 | 2.1% |

| Sep-2006 | 0.7% |

| Oct-2006 | 1.0% |

| Nov-2006 | 1.4% |

| Dec-2006 | 1.7% |

| Jan-2007 | 1.1% |

| Feb-2007 | 2.0% |

| Mar-2007 | 2.3% |

| Apr-2007 | 2.2% |

| May-2007 | 2.2% |

| Jun-2007 | 2.2% |

| Jul-2007 | 2.2% |

| Aug-2007 | 1.7% |

| Sep-2007 | 2.5% |

| Oct-2007 | 2.4% |

| Nov-2007 | 2.5% |

| Dec-2007 | 2.4% |

| Jan-2008 | 2.2% |

| Feb-2008 | 1.8% |

| Mar-2008 | 1.4% |

| Apr-2008 | 1.7% |

| May-2008 | 2.2% |

| Jun-2008 | 3.1% |

| Jul-2008 | 3.4% |

| Aug-2008 | 3.5% |

| Sep-2008 | 3.4% |

| Oct-2008 | 2.6% |

| Nov-2008 | 2.0% |

| Dec-2008 | 1.2% |

| Jan-2009 | 1.1% |

| Feb-2009 | 1.4% |

| Mar-2009 | 1.2% |

| Apr-2009 | 0.4% |

| May-2009 | 0.1% |

| Jun-2009 | -0.3% |

| Jul-2009 | -0.9% |

| Aug-2009 | -0.8% |

| Sep-2009 | -0.9% |

| Oct-2009 | 0.1% |

| Nov-2009 | 1.0% |

| Dec-2009 | 1.3% |

| Jan-2010 | 1.9% |

| Feb-2010 | 1.6% |

| Mar-2010 | 1.4% |

| Apr-2010 | 1.8% |

| May-2010 | 1.4% |

| Jun-2010 | 1.0% |

| Jul-2010 | 1.8% |

| Aug-2010 | 1.7% |

| Sep-2010 | 1.9% |

| Oct-2010 | 2.4% |

| Nov-2010 | 2.0% |

| Dec-2010 | 2.4% |

| Jan-2011 | 2.3% |

| Feb-2011 | 2.2% |

| Mar-2011 | 3.3% |

| Apr-2011 | 3.3% |

| May-2011 | 3.7% |

| Jun-2011 | 3.1% |

| Jul-2011 | 2.7% |

| Aug-2011 | 3.1% |

| Sep-2011 | 3.2% |

| Oct-2011 | 2.9% |

| Nov-2011 | 2.9% |

| Dec-2011 | 2.3% |

| Jan-2012 | 2.5% |

| Feb-2012 | 2.6% |

| Mar-2012 | 1.9% |

| Apr-2012 | 2.0% |

| May-2012 | 1.2% |

| Jun-2012 | 1.5% |

| Jul-2012 | 1.3% |

| Aug-2012 | 1.2% |

| Sep-2012 | 1.2% |

| Oct-2012 | 1.2% |

| Nov-2012 | 0.8% |

| Dec-2012 | 0.8% |

| Jan-2013 | 0.5% |

| Feb-2013 | 1.2% |

| Mar-2013 | 1.0% |

| Apr-2013 | 0.4% |

| May-2013 | 0.7% |

| Jun-2013 | 1.2% |

| Jul-2013 | 1.3% |

| Aug-2013 | 1.1% |

| Sep-2013 | 1.1% |

| Oct-2013 | 0.7% |

| Nov-2013 | 0.9% |

| Dec-2013 | 1.2% |

| Jan-2014 | 1.5% |

| Feb-2014 | 1.1% |

| Mar-2014 | 1.5% |

| Apr-2014 | 2.0% |

| May-2014 | 2.3% |

| Jun-2014 | 2.4% |

| Jul-2014 | 2.1% |

| Aug-2014 | 2.1% |

| Sep-2014 | 2.0% |

| Oct-2014 | 2.4% |

| Nov-2014 | 2.0% |

| Dec-2014 | 1.5% |

| Jan-2015 | 1.0% |

| Feb-2015 | 1.0% |

| Mar-2015 | 1.2% |

| Apr-2015 | 0.8% |

| May-2015 | 0.9% |

| Jun-2015 | 1.0% |

| Jul-2015 | 1.3% |

| Aug-2015 | 1.3% |

| Sep-2015 | 1.0% |

| Oct-2015 | 1.0% |

| Nov-2015 | 1.4% |

| Dec-2015 | 1.6% |

| Jan-2016 | 2.0% |

| Feb-2016 | 1.4% |

| Mar-2016 | 1.3% |

| Apr-2016 | 1.7% |

| May-2016 | 1.5% |

| Jun-2016 | 1.5% |

| Jul-2016 | 1.3% |

| Aug-2016 | 1.1% |

| Sep-2016 | 1.3% |

| Oct-2016 | 1.5% |

| Nov-2016 | 1.2% |

| Dec-2016 | 1.5% |

| Jan-2017 | 2.1% |

| Feb-2017 | 2.0% |

| Mar-2017 | 1.6% |

| Apr-2017 | 1.6% |

| May-2017 | 1.3% |

| Jun-2017 | 1.0% |

| Jul-2017 | 1.2% |

| Aug-2017 | 1.4% |

| Sep-2017 | 1.6% |

| Oct-2017 | 1.4% |

| Nov-2017 | 2.1% |

| Dec-2017 | 1.9% |

| Jan-2018 | 1.7% |

| Feb-2018 | 2.2% |

| Mar-2018 | 2.3% |

| Apr-2018 | 2.2% |

| May-2018 | 2.2% |

| Jun-2018 | 2.5% |

| Jul-2018 | 3.0% |

| Aug-2018 | 2.8% |

| Sep-2018 | 2.2% |

| Oct-2018 | 2.4% |

| Nov-2018 | 1.7% |

| Dec-2018 | 2.0% |

| Jan-2019 | 1.4% |

| Feb-2019 | 1.5% |

| Mar-2019 | 1.9% |

| Apr-2019 | 2.0% |

| May-2019 | 2.4% |

| Jun-2019 | 2.0% |

| Jul-2019 | 2.0% |

| Aug-2019 | 1.9% |

| Sep-2019 | 1.9% |

| Oct-2019 | 1.9% |

| Nov-2019 | 2.2% |

| Dec-2019 | 2.2% |

| Jan-2020 | 2.4% |

| Feb-2020 | 2.2% |

| Mar-2020 | 0.9% |

| Apr-2020 | -0.2% |

| May-2020 | -0.4% |

| Jun-2020 | 0.7% |

| Jul-2020 | 0.1% |

| Aug-2020 | 0.1% |

| Sep-2020 | 0.5% |

| Oct-2020 | 0.7% |

| Nov-2020 | 1.0% |

| Dec-2020 | 0.7% |

| Jan-2021 | 1.0% |

| Feb-2021 | 1.1% |

| Mar-2021 | 2.2% |

| Apr-2021 | 3.4% |

| May-2021 | 3.6% |

| Jun-2021 | 3.1% |

| Jul-2021 | 3.7% |

| Aug-2021 | 4.1% |

| Sep-2021 | 4.4% |

| Oct-2021 | 4.7% |

| Nov-2021 | 4.7% |

| Dec-2021 | 4.8% |

| Jan-2022 | 5.1% |

| Feb-2022 | 5.7% |

| Mar-2022 | 6.7% |

- Note: The grey band indicates Bank of Canada’s 1-3% control range for the inflation target with inflation measured as the 12-month rate of change in the consumer price index (CPI), Bank of Canada, Monetary Policy Report, July 2022.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Table 18-10-0004-01.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought a challenging environment for many Canadian businesses. The impact was uneven on firms; it hit harder to small businesses in high-contact service industries. However, with governments’ financial support, many businesses managed cash flow pressures in spite of falls in revenues. Default risks was generally contained. By the end of FY2122, 4 out of 5 businesses reported capacity pressures related to labour or supply chain challenges. This is reflected in job vacancy figures reported in this chapter.Footnote 10,Footnote 11

On the international horizon, among G7 countries—a group consisting of the world’s major industrialized and advanced countries including CanadaFootnote 12—real GDP in Canada grew by 5.7% in FY2122Footnote 13 compared to FY2021. By the end of FY2122, economic output in all G7 countries, except for Japan and Italy, had returned to pre-pandemic levels. Canada continued to enjoy a high standard of living and ranked third among G7 nations in terms of real GDP per capita (using fixed Purchasing Power Parity) with roughly US$45,600 per capita on average over FY2122.Footnote 14

1.2 The Canadian labour market

This section highlights key labour market developments in CanadaFootnote 15 during FY2122, including some labour market elements linked to the EI program. Overall, the Canadian labour market was characterised by strong employment growth, a low national unemployment rate and tighter labour market conditions.Footnote 16,Footnote 17

Labour force growth and the labour force participation rate

In FY2122, the size of the total Canadian labour forceFootnote 18 grew by 2.8% (+556,780, from 20.0 million to 20.6 million) relative to FY2021. Compared to its pre-pandemic level recorded in February 2020, the size of the overall Canadian labour market stood 1.8% higher by March 2022. With population aging, the labour force for youth (15 to 24 years old), constrained by its decreasing size of population, was the only group still slightly below its pre-pandemic level (-0.6%) compared to the labour force for individuals aged 25 to 54 years and those aged 55 years and over (+2.7% and +0.6% respectively).

During the 12-month period of FY2122, the growth in the size of the labour force outpaced that of the working age population, leading to an increase in the overall participation rate. Accounting for the negative impact of the COVID-19 at the onset of the pandemic at the beginning of FY2021, the overall participation rate increased from 64.3% in FY2021 to 65.5% in FY2122. However, the participation rate in March 2022 (65.6%) remained slightly lower than what was observed in February 2020 (65.9%).

Compared to its pre-pandemic levels, the participation rate for individuals aged 25 to 54 years was higher in March 2022 (+1.2 percentage points, or p.p.) while it stood at the same level for youth. However, among population 55 years old and over, as the size of the working age population grew faster than the size of the labour force, the participation rate for this age group was still 1.4 p.p. lower. This could be explained by the share of those aged 65 and older among the age group 55 and over that continues to increase, which lower the overall participation rate for the group.

Employment growth

During the reporting period, total employment continued a gradual upward trend, increasing from 18.0 million in FY2021 to 19.2 million in FY2122 (+6.6%). Part-time employment, which was more impacted by the COVD-19 pandemic, grew stronger than full-time employment (+10.0% versus +5.9%) in FY2122 compared to FY2021. As shown in Chart 5, by September 2021, employment regained its pre-pandemic level recorded in February 2020, and by the end of March 2022, employment was 2.3% higher than its pre-pandemic level (+439,900). By March 2022, both full-time employment and part-time employment had surpassed their pre-pandemic levels recorded in February 2020 (by +2.6% and +1.0% respectively).

Text description for chart 5

| Month | Total employment (in millions) |

|---|---|

| Feb-20 | 19.22340 |

| Mar-20 | 18.07500 |

| Apr-20 | 16.08360 |

| May-20 | 16.39540 |

| Jun-20 | 17.43120 |

| Jul-20 | 17.84760 |

| Aug-20 | 18.07290 |

| Sep-20 | 18.50140 |

| Oct-20 | 18.56610 |

| Nov-20 | 18.60250 |

| Dec-20 | 18.53980 |

| Jan-21 | 18.35300 |

| Feb-21 | 18.62250 |

| Mar-21 | 18.87510 |

| Apr-21 | 18.67810 |

| May-21 | 18.61940 |

| Jun-21 | 18.87290 |

| Jul-21 | 18.98200 |

| Aug-21 | 19.05240 |

| Sep-21 | 19.21860 |

| Oct-21 | 19.25510 |

| Nov-21 | 19.39430 |

| Dec-21 | 19.47320 |

| Jan-22 | 19.28600 |

| Feb-22 | 19.64380 |

| Mar-22 | 19.66330 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0287-01.

Employment by class of workerFootnote 19

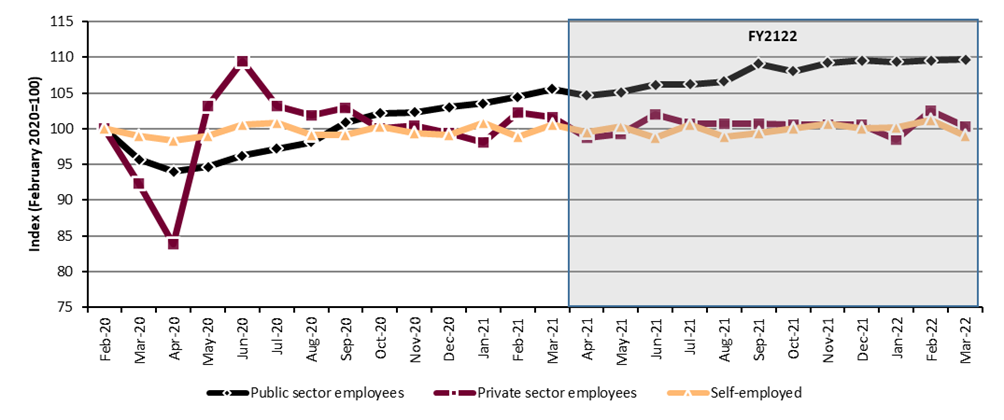

Public health measures imposed at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 led to massive lay-offs in the private sector (consult Chart 6). By the end of March 2022, the size of employment for public and private sectors were above their pre-pandemic levels recorded in February 2020 (+9.7% and +1.9% respectively). However, by the end of FY2122, self-employment was well below its pre-COVID level (‑5.7%). During the decade before the pandemic, self-employment persistently accounted for around 15% of total employment. It stood at 13.8% in FY2122.

Text description for chart 6

| Month | Public sector employees | Private sector employees | Self-employed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feb-20 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Mar-20 | 96 | 93 | 99 |

| Apr-20 | 94 | 78 | 97 |

| May-20 | 94 | 81 | 96 |

| Jun-20 | 95 | 88 | 97 |

| Jul-20 | 96 | 91 | 96 |

| Aug-20 | 97 | 93 | 94 |

| Sep-20 | 101 | 95 | 93 |

| Oct-20 | 101 | 96 | 94 |

| Nov-20 | 101 | 96 | 95 |

| Dec-20 | 102 | 96 | 93 |

| Jan-21 | 102 | 94 | 93 |

| Feb-21 | 103 | 96 | 93 |

| Mar-21 | 104 | 98 | 95 |

| Apr-21 | 104 | 96 | 95 |

| May-21 | 104 | 95 | 95 |

| Jun-21 | 105 | 97 | 93 |

| Jul-21 | 104 | 98 | 92 |

| Aug-21 | 105 | 99 | 92 |

| Sep-21 | 107 | 100 | 92 |

| Oct-21 | 107 | 100 | 91 |

| Nov-21 | 107 | 101 | 92 |

| Dec-21 | 108 | 101 | 92 |

| Jan-22 | 108 | 100 | 92 |

| Feb-22 | 108 | 102 | 91 |

| Mar-22 | 108 | 103 | 93 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0288-01.

Employment by industry and firm sizeFootnote 20

During FY2122, employment continued to grow in most industries. 11 out of 16 broad industrial groups saw employment fully recover to pre-pandemic levels recorded in February 2020. However, employment in Agriculture (-16.5%); Accommodation and food services (‑14.7%); Other services (-9.1%); Business, building and other support services (-8.1%); and Transportation and warehousing (-4.3%) was still below pre-pandemic levels (consult Chart 7). Employment in these industrial groups was more affected by public health measures aiming to control the COVID-19 pandemic waves, such as closureFootnote 21 of non-essential businesses, teleworking arrangements, border closures that reduced the number of foreign workers, and supply chain interruptions.

Text description chart 7

| Industry | Change in total employment by industry Feb 2020 to March 2022 |

|---|---|

| Agriculture | -16.5% |

| Accommodation and food services | -14.7% |

| Other services (except public administration) | -9.1% |

| Business, building and other support services | -8.1% |

| Transportation and warehousing | -4.3% |

| Construction | 1.9% |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 2.2% |

| Total employed, all industries | 2.3% |

| Manufacturing | 2.8% |

| Utilities | 3.5% |

| Health care and social assistance | 3.8% |

| Information, culture and recreation | 3.8% |

| Forestry, fishing, mining, quarrying, oil and gas | 6.8% |

| Finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing | 8.0% |

| Educational services | 9.8% |

| Public administration | 11.3% |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 13.2% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0355-01.

Compared to FY2021, employment grew in enterprises of all sizes.Footnote 22 The distribution of employment across enterprises of various sizes in FY2122 mostly recovered to its pre-pandemic allocation recorded in FY1920. In FY2122, 19.8% of employment was in small-sized enterprises, 19.1% in small-to-medium sized enterprises, 15.3% in medium-to-large sized enterprises and 45.9% in large-sized enterprises.Footnote 23

Employment by age group

Employment increased among workers of all age groups during FY2122 as the labour market continued its recovery. Employment growth was most pronounced for youth who were hard hit with pandemic job losses (+16.1% compared to +5.4% and +4.8%, respectively, among workers aged 25 to 54 years and workers aged 55 years and over). Focusing on the recovery, with successive waves of closures and reopenings in the industries where youth are generally overrepresented (for example, Accommodation and food services; and Wholesale and retail trade), youth employment had a more volatile recovery path. It dropped in May 2021 (due to the 3rd wave) and January 2022 (due to the 5th wave) (consult Chart 8). In February 2022, it finally surpassed its pre-pandemic level recorded in February 2020. Employment in the 25 to 54 age group recovered faster than for youth and surpassed its pre-pandemic level as early as in September 2021, while employment for the 55 years old and over age group returned to its pre-pandemic levels in March 2022.

Text description chart 8

| Month | 15 to 24 years | 25 to 54 years | 55 years and over |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feb-20 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Mar-20 | 83 | 96 | 95 |

| Apr-20 | 65 | 87 | 86 |

| May-20 | 66 | 88 | 88 |

| Jun-20 | 77 | 94 | 91 |

| Jul-20 | 82 | 95 | 93 |

| Aug-20 | 85 | 96 | 94 |

| Sep-20 | 91 | 98 | 95 |

| Oct-20 | 90 | 98 | 96 |

| Nov-20 | 90 | 98 | 97 |

| Dec-20 | 88 | 98 | 97 |

| Jan-21 | 84 | 97 | 97 |

| Feb-21 | 89 | 98 | 98 |

| Mar-21 | 93 | 99 | 100 |

| Apr-21 | 90 | 98 | 98 |

| May-21 | 87 | 98 | 98 |

| Jun-21 | 94 | 99 | 99 |

| Jul-21 | 96 | 99 | 99 |

| Aug-21 | 98 | 99 | 99 |

| Sep-21 | 99 | 101 | 99 |

| Oct-21 | 99 | 101 | 98 |

| Nov-21 | 100 | 102 | 99 |

| Dec-21 | 100 | 102 | 99 |

| Jan-22 | 96 | 102 | 99 |

| Feb-22 | 101 | 103 | 100 |

| Mar-22 | 101 | 103 | 101 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0287-01.

Employment by gender

Though women’s employment was impacted more by the COVID-19 pandemic than that of men in FY2021, it recovered more quickly during FY2122. Compared to the previous fiscal year, total employment of women grew by 7.4% in FY2122 compared to 5.9% for men. By the end of FY2122, employment for both genders was higher than their pre-pandemic levels recorded in February 2020 (+2.1% among men and +2.5% among women). Employment of men working part-time was above its pre-pandemic level in March 2022 (+2.7%), whereas employment of women working part-time was closed to (+0.1%) its pre-pandemic level.

Employment rates

Employment growth may be shaped by demographic trends such as growth in the working-age population or by improved labour market conditions. In order to examine net job creation in the Canadian labour market, this section looks at the employment rate indicator, that is the proportion of the working age population 15 years and over who are currently employed.

On yearly basis, in FY2122, the employment rate was up by 3.2 p.p., increasing from 57.8% in FY2021 to 61.0% (consult Table 1). Yet, it was still below its pre-pandemic level recorded in FY1920 (61.9%) and also below its historical peak of 63.4% recorded in FY0708. The employment rate for men increased by 3.0 p.p., slightly below the increase of 3.4 p.p. for women between FY2021 and FY2122. Higher rates were also registered for individuals across all 3 age groups in FY2122 (+8.2 p.p. for youth, +3.8 p.p. for those aged 25 to 54 years and +1.0 p.p. for those aged 55 years and over, respectively) compared to FY2021.

Focusing on the recovery path between time points of February 2020 and March 2022, the employment rate recovered to its pre-pandemic level for women (by +0.2 p.p.). However, it was still slightly below its pre-pandemic level for men (by -0.1 p.p.) By age group, only employment rate for youth and individuals aged 25 to 54 years had fully recovered (+0.9 p.p. and +1.5 p.p. respectively). For those aged 55 years and over the employment rate remained below its pre-pandemic level ( 1.3 p.p.), mostly due to the increasing share of those aged 65 and over among the age group, as they tend to have low employment rate.

| Category | Employment rate FY2021 |

Employment rate FY2122 |

Change in employment rate FY2021 to FY2122 (p.p.) |

Employment rate February 2020 |

Employment rate March 2022 |

Change in employment rate February 2020 to March 2022 (p.p.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 61.9% | 64.9% | +3.0 | 66.1% | 66.0% | -0.1 |

| Women | 53.8% | 57.2% | +3.4 | 58.2% | 58.4% | +0.2 |

| 15 to 24 years old | 49.0% | 57.2% | +8.2 | 58.7% | 59.6% | +0.9 |

| 25 to 54 years old | 79.5% | 83.3% | +3.8 | 83.3% | 84.7% | +1.5 |

| 55 years old and over | 33.9% | 34.8% | +1.0 | 36.4% | 35.1% | -1.3 |

| Canada | 57.8% | 61.0% | +3.2 | 62.1% | 62.2% | +0.1 |

- Note: Percentage point change is based on unrounded numbers.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0287-01.

Compared to other G7 countries, Canada registered the largest increase in employment rate between FY2021 and FY2122. With this, Canada ranked first in terms of employment rate in FY2122, up from the fourth place in FY2021.Footnote 24

Unemployment rates

Unemployment rate is one of the core elements that determines eligibility for EI regular benefits. Under EI original rules, a lower unemployment rate in an EI economic region translates into a higher required number of hours of insurable employment within the qualifying period to be eligible for EI regular benefits. The unemployment rate in an EI economic region also plays a role in determining the EI regular benefit entitlement available to a claimant and the number of weeks of earnings (knows as divisor) used in the calculation of their weekly benefit rate. Regional variations of the unemployment rate are discussed in subsection 1.3. Consult section 2.1 in Chapter II to learn how the different EI temporary measures affected the eligibility for, and entitlement to, EI regular benefits.

With the reopening of businesses and tightening labour market conditions, the number of unemployed individuals decreased significantly in FY2122, from 2.0 million in FY2021 to 1.4 million in FY2122, registering a 31.0% decline. Combined with the increase in the size of the Canadian labour force during the same period, the unemployment rate dropped from 10.2% in FY2021 to 6.8% in FY2122 (consult Table 2). The unemployment rate decreased at similar pace for men and women between FY2021 and FY2122 while it decreased at varied paces across age groups. The unemployment rate for youth experienced the largest drop (-9.0 p.p.), followed by that for the 25 to 54 age group (-2.7 p.p.) and the 55 years old and over age group (-1.6 p.p.).

The unemployment rates for youth and individuals aged 25 to 54 years registered lower levels in March 2022 compared to February 2020, with youth seeing the largest decline (-1.4 p.p.). This is mainly because the labour force for youth was still below its pre-pandemic level due to faster drop in the number of unemployed (-13.6%) among youth. However, the unemployment rate for individuals aged 55 years and over was slight above its pre-pandemic level (+0.1 p.p.) The unemployment rate for women was the same as its pre-pandemic level, while that for men was slightly lower (-0.8 p.p.) (consult Table 2).

| Category | Unemployment rate FY2021 |

Unemployment rate FY2122 |

Change in unemployment rate FY2021 to FY2122 (p.p.) |

Unemployment rate February 2020 |

Unemployment rate March 2022 |

Change in unemployment rate February 2020 to March 2022 (p.p.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 10.3% | 7.0% | -3.3 | 6.0% | 5.2% | -0.8 |

| Women | 10.0% | 6.6% | -3.4 | 5.4% | 5.4% | 0.0 |

| 15 to 24 years old | 21.0% | 11.9% | -9.0 | 10.6% | 9.2% | -1.4 |

| 25 to 54 years old | 8.3% | 5.6% | -2.7 | 4.8% | 4.4% | -0.4 |

| 55 years old and over | 8.7% | 7.1% | -1.6 | 5.3% | 5.3% | +0.1 |

| Canada | 10.2% | 6.8% | -3.3 | 5.7% | 5.3% | -0.5 |

- Note: Percentage point change is based on unrounded numbers.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0287-01.

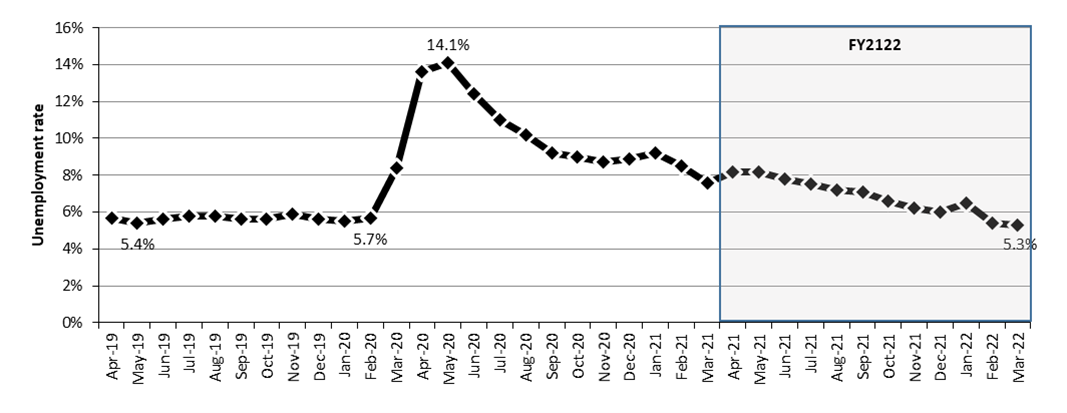

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the monthly unemployment rate hit a historical low of 5.4% in May 2019 (consult Chart 9). It peaked at 14.1% in May 2020 at the onset of the pandemic and trended down afterwards with small increases associated with subsequent pandemic waves. During FY2122, the unemployment rate rose slightly in January 2022 due to the impact of the fifth wave but resumed its downward trend afterwards. In March 2022, the unemployment rate stood at a new historical low level of 5.3%, indicating tighter conditions in the Canadian labour market. This was not only lower than the pre-pandemic level of 5.7% recorded in February 2020, but it also registered a new historical low of monthly unemployment rate since comparable data became available in January 1976.

Text description chart 9

| Month | Unemployment rate |

|---|---|

| Apr-19 | 5.7% |

| May-19 | 5.4% |

| Jun-19 | 5.6% |

| Jul-19 | 5.8% |

| Aug-19 | 5.8% |

| Sep-19 | 5.6% |

| Oct-19 | 5.6% |

| Nov-19 | 5.9% |

| Dec-19 | 5.6% |

| Jan-20 | 5.5% |

| Feb-20 | 5.7% |

| Mar-20 | 8.4% |

| Apr-20 | 13.6% |

| May-20 | 14.1% |

| Jun-20 | 12.4% |

| Jul-20 | 11.0% |

| Aug-20 | 10.2% |

| Sep-20 | 9.2% |

| Oct-20 | 9.0% |

| Nov-20 | 8.7% |

| Dec-20 | 8.9% |

| Jan-21 | 9.2% |

| Feb-21 | 8.5% |

| Mar-21 | 7.6% |

| Apr-21 | 8.2% |

| May-21 | 8.2% |

| Jun-21 | 7.8% |

| Jul-21 | 7.5% |

| Aug-21 | 7.2% |

| Sep-21 | 7.1% |

| Oct-21 | 6.6% |

| Nov-21 | 6.2% |

| Dec-21 | 6.0% |

| Jan-22 | 6.5% |

| Feb-22 | 5.4% |

| Mar-22 | 5.3% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0287-01.

Internationally, Canada posted the second largest decline in unemployment rate among the G7 countries in FY2122 compared to FY2021. Canada recorded the third highest unemployment rates in FY2122 among the G7, just below France and Italy.Footnote 25 Unemployment rate rose sharply in Canada and in the United States at the onset of the pandemic, whereas there were relatively small increases in the remaining G7 countries. As noted by the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), the heterogeneity of the impact on unemployment across OECD countries reflected fundamental differences in countries’ policy mix to cushion the economic and social effects of the crisis.Footnote 26

Duration of unemploymentFootnote 27

Along with the decrease in the national unemployment rate in FY2122, 2 indicators measuring unemployment duration also exhibited a downward trend over the reporting period: average duration of unemployment and share of long-term unemployment (looking for work for 52 weeks or more). The average duration of unemployment (the number of continuous weeks of unemployment where an individual is looking for work or is on temporary layoff) at the early stage of the pandemic dropped noticeably due to a significant increase in recent unemployed individuals. This was followed by large growth in average duration of unemployment as the pandemic’s impact lingered (consult Chart 10). It was 22.3 weeks in March 2021, peaked at 25.6 weeks in October 2021 and then went down to 19.6 weeks in March 2022 with the gradual re-opening of nonessential businesses. However, this was still above the 16.7-week level recorded in February 2020. On an annual basis, the average duration of unemployment was 22.3 weeks for FY2122, up by 4.9 weeks from 17.4 weeks recorded in FY2021.

Accompanying the evolution of the average duration of unemployment, the proportion of unemployed Canadians who had been continuously searching for a job for a period of at least 52 consecutive weeksFootnote 28 (the share of long-term unemployment) rose dramatically in the second half of FY2021. In FY2122, it peaked in April 2021 at 18.9% of total unemployed (accounting for 313,100 long-term unemployed) and gradually trended down to 11.8% of total unemployed (representing 129,000 long-term unemployed) in March 2022. This share of long-term unemployment was still above its pre-pandemic level of 8.4% observed in February 2020. Among G7 countries, Canada reported the lowest proportion of unemployment lasting for one year or over in 2021.Footnote 29

Text description chart 10

| Month | Average weeks of unemployment spells (left scale) | Share of long-term unemployment (%) (right scale) |

|---|---|---|

| Mar-19 | 17.2 | 9.7 |

| Apr-19 | 16.8 | 8.1 |

| May-19 | 16.3 | 8.0 |

| Jun-19 | 16.2 | 7.1 |

| Jul-19 | 16.8 | 8.1 |

| Aug-19 | 15.8 | 7.4 |

| Sep-19 | 15.5 | 6.7 |

| Oct-19 | 17 | 7.7 |

| Nov-19 | 16.1 | 7.3 |

| Dec-19 | 16.4 | 7.8 |

| Jan-20 | 17.4 | 8.6 |

| Feb-20 | 16.7 | 8.4 |

| Mar-20 | 11.7 | 5.4 |

| Apr-20 | 8.7 | 2.8 |

| May-20 | 11.1 | 3.0 |

| Jun-20 | 13 | 3.7 |

| Jul-20 | 16.1 | 4.4 |

| Aug-20 | 17 | 4.8 |

| Sep-20 | 20.1 | 5.5 |

| Oct-20 | 18.8 | 6.2 |

| Nov-20 | 18.6 | 5.9 |

| Dec-20 | 20.5 | 7.3 |

| Jan-21 | 21 | 8.7 |

| Feb-21 | 21.7 | 10.1 |

| Mar-21 | 22.3 | 16.3 |

| Apr-21 | 21.3 | 18.9 |

| May-21 | 21.9 | 18.1 |

| Jun-21 | 24.4 | 18.6 |

| Jul-21 | 23.1 | 18.0 |

| Aug-21 | 23 | 16.8 |

| Sep-21 | 24.6 | 16.5 |

| Oct-21 | 25.6 | 17.1 |

| Nov-21 | 22 | 13.7 |

| Dec-21 | 21.3 | 13.2 |

| Jan-22 | 20.6 | 12.6 |

| Feb-22 | 19.9 | 11.7 |

| Mar-22 | 19.6 | 11.8 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0342-01.

Individuals aged 55 years and over are generally more likely to have longer durations of unemployment. The COVID-19 period was no exception. In February 2020, the share of long-term unemployed was 14.5% among those aged 55 years and over, compared to 8.2% among those aged 25 to 54 years and 4.2% among youth. By the end of FY2122, it increased to 17.8%, 11.6% and 6.7% respectively for the 3 age groups. Similarly, relative to February 2020, in March 2022, the average duration of unemployment reached 26.2 weeks (+3.0 weeks) among workers aged 55 years and over, 20.9 weeks (+4.0 weeks) among those aged 25 to 54 years, and 12.5 weeks (+1.6 week) among youth.

In February 2020, the share of long-term unemployment was similar for men and women (8.9% and 7.8% respectively). By the end of FY2122, it reached 13.3% for men and 10.1% for women. Compared to February 2020, the average duration of unemployment increased by 3.6 weeks for men, reaching 20.9 weeks in March 2022, while it increased by 2.8 weeks for women, reaching 18.4 weeks.

Reasons for unemploymentFootnote 30

In general, workers can become unemployed for a number of reasons, and the cause of unemployment is a key factor in determining if the individual is eligible for EI benefits. EI regular benefits are only available to individuals who have lost their job for reasons outside their control or who left their job with just cause. As labour market conditions improved from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, reasons for unemployment continued to change during FY2122.

In the Labour Force Survey, 5 categories of reasons for unemployment are reported: job leavers, permanent layoff, temporary layoff, not worked last year and never worked. Among these, the permanent and temporary layoff are most relevant to the administration of the EI program.

Before May 2021, individuals who became unemployed because they lost their job (due to temporary or permanent layoffs) accounted for the largest share of the unemployed population in Canada. As many individuals lost their jobs at the beginning of the pandemic and remained unemployed through FY2021, unemployed individuals who did not work in the last year dominated the unemployment population starting May 2021 until January 2022 (consult Chart 11).

With public health restrictions easing and gradual re-opening of businesses, the share of temporary layoffs among the unemployed population decreased from 22.2% in FY2021 to 7.1% in FY2122, and the share of permanent layoffs decreased from 41.2% to 32.7% over the same period. The share of job leavers and unemployed individuals who have never worked stood at 12.6% and 11.2% in FY2122, similar to their levels in FY2021.

From an EI perspective, eligibility for regular benefits is largely based on the number of hours of insurable employment that an individual has accumulated in the previous 52 weeks (hours threshold for eligibility varies depending on the EI economic region where worker resides). The COVID-19 pandemic led to a higher proportion of unemployed individuals who did not work in the last year among the unemployed population (increased from 15.6% in FY2021 to 36.5% in FY2122). This, in conjunction with the different EI temporary measures put in place to facilitate access to EI benefits, would likely affect the indicators of access and coverage of the EI program in FY2122.

Text description chart 11

| Month | Job leavers | Permanent layoff | Temporary layoff | Not worked last year | Never worked |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mar-19 | 20.8% | 40.6% | 5.0% | 23.2% | 10.5% |

| Apr-19 | 20.7% | 40.9% | 4.7% | 22.6% | 11.2% |

| May-19 | 25.4% | 36.0% | 3.5% | 23.2% | 11.9% |

| Jun-19 | 22.2% | 35.5% | 3.6% | 24.7% | 14.0% |

| Jul-19 | 20.2% | 36.5% | 5.4% | 22.0% | 15.9% |

| Aug-19 | 19.2% | 41.4% | 4.2% | 21.2% | 14.0% |

| Sep-19 | 24.6% | 32.4% | 2.9% | 27.1% | 12.9% |

| Oct-19 | 23.7% | 33.0% | 3.8% | 26.2% | 13.3% |

| Nov-19 | 22.3% | 37.1% | 3.9% | 24.4% | 12.4% |

| Dec-19 | 20.2% | 39.7% | 5.6% | 24.4% | 10.1% |

| Jan-20 | 19.1% | 39.8% | 7.1% | 24.0% | 10.0% |

| Feb-20 | 18.0% | 40.9% | 5.5% | 25.6% | 10.0% |

| Mar-20 | 11.7% | 31.2% | 36.1% | 13.9% | 7.1% |

| Apr-20 | 7.1% | 27.8% | 54.1% | 7.3% | 3.6% |

| May-20 | 11.1% | 31.8% | 42.3% | 9.2% | 5.7% |

| Jun-20 | 11.7% | 39.3% | 27.5% | 12.1% | 9.4% |

| Jul-20 | 13.6% | 42.1% | 17.7% | 14.7% | 12.1% |

| Aug-20 | 12.8% | 48.4% | 13.2% | 13.7% | 11.9% |

| Sep-20 | 14.2% | 44.8% | 10.2% | 18.8% | 12.0% |

| Oct-20 | 15.0% | 45.3% | 10.0% | 19.9% | 9.9% |

| Nov-20 | 13.1% | 47.8% | 8.7% | 20.1% | 10.3% |

| Dec-20 | 10.9% | 46.7% | 12.2% | 19.8% | 10.4% |

| Jan-21 | 9.7% | 43.5% | 19.6% | 18.0% | 9.2% |

| Feb-21 | 12.4% | 43.3% | 14.1% | 21.4% | 8.8% |

| Mar-21 | 11.7% | 45.0% | 9.6% | 23.0% | 10.6% |

| Apr-21 | 10.6% | 30.8% | 13.6% | 33.5% | 11.5% |

| May-21 | 10.5% | 28.2% | 12.0% | 38.3% | 11.0% |

| Jun-21 | 11.3% | 28.0% | 7.2% | 41.5% | 12.1% |

| Jul-21 | 10.4% | 33.1% | 5.3% | 37.0% | 14.2% |

| Aug-21 | 11.4% | 36.5% | 4.5% | 37.0% | 10.5% |

| Sep-21 | 12.8% | 31.3% | 3.6% | 41.4% | 10.9% |

| Oct-21 | 14.9% | 29.4% | 3.0% | 42.4% | 10.2% |

| Nov-21 | 15.2% | 33.1% | 2.9% | 39.2% | 9.6% |

| Dec-21 | 12.5% | 35.2% | 3.5% | 38.0% | 10.9% |

| Jan-22 | 13.2% | 36.0% | 14.5% | 27.7% | 8.5% |

| Feb-22 | 15.6% | 35.9% | 5.3% | 31.0% | 12.2% |

| Mar-22 | 15.7% | 37.3% | 4.7% | 30.6% | 11.7% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0125-01, seasonally unadjusted.

Hours of workFootnote 31

“Hours of work” is closely related to the administration of the EI program. The number of hours of insurable employment is a key eligibility criterion of the EI program, as claimants must have worked a minimum number of insurable hours in the qualifying period to be eligible for EI benefits. It also determines, along with the regional unemployment rate, the maximum number of weeks of EI regular benefits a claimant is entitled to receive.

The average number of hours usually worked from all jobs by Canadians—hours usually worked in a typical week, not including any overtime—held constant at 36.4 per week in FY2122. It has been flat in recent years and below the FY0809 pre-recession level.

In contrast, the average actual hours worked often reflects temporary decreases or increases in work hours (for example, hours lost due to illness or vacation, or more hours worked due to overtime). At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the average actual hours worked per worker from all jobs (including overtime) fell from 33.1 hours a week in February 2020 to 27.9 hours in April 2020 (consult chart 12). The average then rebounded in the following months and remained close to levels observed before the pandemic. Over the FY2122, the average actual hours worked from all jobs per week steadily followed a regular month-to-month fluctuation. In March 2022, the average actual hours worked from all jobs stood at 32.5 hours a week.

Text description chart 12

| Month | Hours worked |

|---|---|

| Mar-19 | 32.6 |

| Apr-19 | 30.5 |

| May-19 | 34 |

| Jun-19 | 34.6 |

| Jul-19 | 32 |

| Aug-19 | 31.6 |

| Sep-19 | 34.3 |

| Oct-19 | 31 |

| Nov-19 | 32.4 |

| Dec-19 | 33.9 |

| Jan-20 | 33 |

| Feb-20 | 33.1 |

| Mar-20 | 28.8 |

| Apr-20 | 27.9 |

| May-20 | 30.6 |

| Jun-20 | 32.1 |

| Jul-20 | 30.8 |

| Aug-20 | 30.4 |

| Sep-20 | 33.2 |

| Oct-20 | 31.1 |

| Nov-20 | 32 |

| Dec-20 | 33.3 |

| Jan-21 | 32.9 |

| Feb-21 | 31.6 |

| Mar-21 | 33.5 |

| Apr-21 | 33.1 |

| May-21 | 34 |

| Jun-21 | 33.8 |

| Jul-21 | 31.7 |

| Aug-21 | 31.3 |

| Sep-21 | 33.8 |

| Oct-21 | 32 |

| Nov-21 | 32.4 |

| Dec-21 | 33.7 |

| Jan-22 | 32.3 |

| Feb-22 | 33.3 |

| Mar-22 | 32.5 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0042-01, seasonally unadjusted.

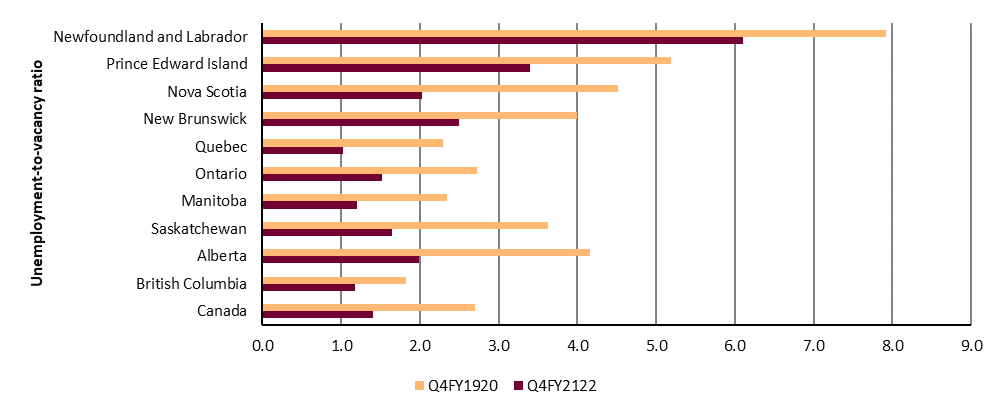

Job vacanciesFootnote 32 and labour market tightness

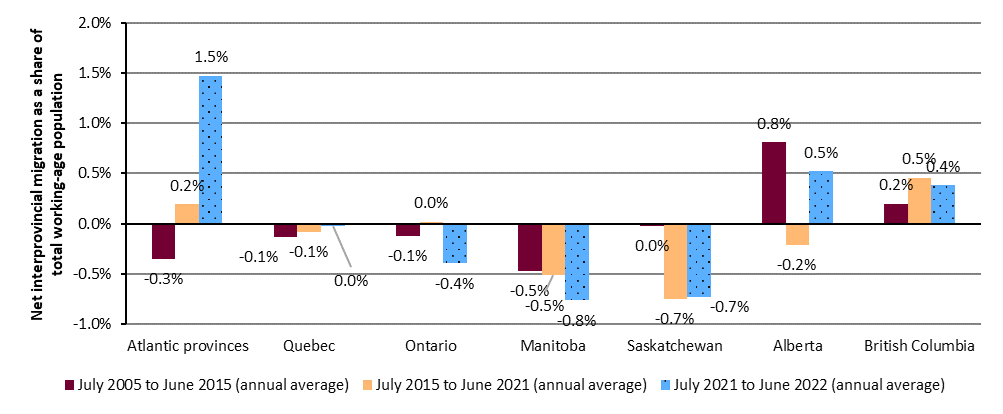

Over FY2122, both job vacancies and job vacancy rates reached record levels in Canada. This was potentially influenced by factors such as population aging, declines in immigration inflows during the COVID-19 pandemic, and structural changes of the labour market brought by economic lockdowns.

The number of job vacancies is the number of unoccupied positions for which employers are actively seeking workers. As the economy continued to recover, in the third quarterFootnote 33 of FY2122, the number of job vacancies went up by 63.4% compared to the same quarter of FY2021 (+80.0% compared to the third quarter of FY1920), hitting a historical high of 915,545 vacant positions (consult Chart 13). This increase was larger than the increase in employment. The same situation prevailed in the last quarter of FY2122, with job vacancies being 60.9% higher than a year earlier (+73.6% compared to two years earlier). Over this period, the job vacancy rate (number of job vacancies expressed as a percentage of all occupied and vacant jobs) hit historical high of 5.4% in the second quarter of FY2122. It remained high at 5.3% and 5.2% in the last two quarters of FY2122.

Text description chart 13

| Quarter | Job vacancies, in thousands (left scale) | Job vacancy rate (right scale) |

|---|---|---|

| Q1FY1920 | 581.6 | 3.5% |

| Q2FY1920 | 562.9 | 3.3% |

| Q3FY1920 | 508.6 | 3.0% |

| Q4FY1920 | 512.8 | 3.1% |

| Q1FY2021 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Q2FY2021 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Q3FY2021 | 560.2 | 3.5% |

| Q4FY2021 | 553.5 | 3.6% |

| Q1FY2122 | 731.9 | 4.6% |

| Q2FY2122 | 912.6 | 5.4% |

| Q3FY2122 | 915.5 | 5.3% |

| Q4FY2122 | 890.4 | 5.2% |

- * Statistics Canada temporarily suspended the data collection of the Job Vacancy and Wage Survey during the first and second quarters of FY2021.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Job Vacancy and Wage Survey, Table 14-10-0326-01, seasonally unadjusted.

An increase in the job vacancies has been observed in all industrial groups (consult Table 3). Among them, Management of companies and enterprises (+117.2%), Construction (+107.0%), and Accommodation and food services (+101.8%) had the highest increases, more than doubling in the last quarter of FY2122 compared to the same period two years ago.

| Industry | Fourth quarter of FY1920 | Fourth quarter of FY2021 | Fourth quarter of FY2122 | Change (%) fourth quarter of FY1920 to fourth quarter of FY2122 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | 12,105 | 11,700 | 13,745 | +13.5% |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction | 4,500 | 5,090 | 8,760 | +94.7% |

| Utilities | 2,080 | 1,560 | 2,850 | +37.0% |

| Construction | 34,830 | 46,370 | 72,090 | +107.0% |

| Manufacturing | 42,075 | 52,205 | 82,705 | +96.6% |

| Wholesale trade | 21,875 | 23,425 | 36,105 | +65.1% |

| Retail trade | 50,380 | 54,795 | 85,740 | +70.2% |

| Transportation and warehousing | 24,840 | 27,170 | 44,130 | +77.7% |

| Information and cultural industries | 12,860 | 11,225 | 17,720 | +37.8% |

| Finance and insurance | 22,820 | 23,760 | 35,450 | +55.3% |

| Real estate and rental and leasing | 7,535 | 6,790 | 11,240 | +49.2% |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 42,565 | 47,795 | 69,565 | +63.4% |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 2,215 | 2,320 | 4,810 | +117.2% |

| Administrative and support, waste management and remediation services | 38,895 | 36,750 | 57,930 | +48.9% |