Chapter 1: Labour Market Context

Official title: Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2022, and ending March 31, 2023: Chapter 1 – Labour market context

In chapter 1

List of abbreviations

This is the complete list of abbreviations for the Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2022 and ending March 31, 2023.

- AD

- Appeal Division

- ADR

- Alternative Dispute Resolution

- AI

- Artificial Intelligence

- ASETS

- Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy

- B

- Beneficiary

- B/C Ratio

- Benefits-to-Contributions ratio

- B/U

- Beneficiary-to-Unemployed (ratio)

- B/UC

- Beneficiary-to-Unemployed Contributor (ratio)

- BDM

- Benefits Delivery Modernization

- BEA

- Business Expertise Advisor

- BOA

- Board of Appeal

- CAWS

- Client Access Workstation Services

- CCAJ

- Connecting Canadians with Available Jobs

- CCDA

- Canadian Council of Directors of Apprenticeship

- CCIS

- Corporate Client Information Service

- CEGEP

- College of General and Professional Teaching

- CEIC

- Canada Employment Insurance Commission

- CERB

- Canada Emergency Response Benefit

- CESB

- Canada Emergency Student Benefit

- CEWB

- Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy

- CFP

- Call for Proposals

- COEP

- Canadian Out of Employment Panel Survey

- COLS

- Community Outreach and Liaison Service

- CPI

- Consumer Price Index

- CPP

- Canada Pension Plan

- CRA

- Canada Revenue Agency

- CRB

- Canada Recovery Benefit

- CRCB

- Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit

- CRF

- Consolidated Revenue Fund

- CRSB

- Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit

- CSO

- Citizen Service Officer

- CWLB

- Canada Worker Lockdown Benefit

- CX

- Client Experience

- EAS

- Employment Assistance Services

- EBSM

- Employment Benefits and Support Measures

- ECC

- Employer Contact Centre

- EI

- Employment Insurance

- EI-ERB

- Employment Insurance Emergency Response Benefit

- EICS

- Employment Insurance Coverage Survey

- EIPR

- Employment Insurance Premium Ratio

- eROE

- Electronic Record of Employment

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- eSIN

- Electronic Social Insurance Number

- FY

- Fiscal Year

- G7

- Group of Seven

- GDP

- Gross Domestic Product

- GIS

- Guaranteed Income Supplement

- HCCS

- Hosted Contact Centre Solution

- HR

- Human Resources

- ID

- Identification

- IQF

- Individual Quality Feedback

- IS

- Income Security

- ISET

- Indigenous Skills and Employment Training

- IT

- Information Technology

- IVR

- Interactive Voice Response

- IWW

- Integrated Workload and Workforce

- JCP

- Job Creation Partnership

- LFS

- Labour Force Survey

- LMDA

- Labour Market Development Agreements

- LMI

- Labour Market Information

- LMP

- Labour Market Partnerships

- LTU

- Long-Term Unemployment or Long-Term Unemployed

- LTUR

- Long-Term Unemployment Rate

- LWF

- Longitudinal Worker File

- MAR

- Monitoring and Assessment Report

- MBM

- Market Basket Measure

- MIE

- Maximum Insurable Earnings

- MSCA

- My Service Canada Account

- MUS

- Monetary Unit Sampling

- NAICS

- North American Industry Classification System

- NERE

- New entrant re-entrant

- NESI

- National Essential Skills Initiative

- NHQ

- National Headquarters

- NIS

- National Investigative Services

- NOC

- National Occupation Classification

- NOM

- National Operating Model

- NQCP

- National Quality and Coaching Program

- OAG

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada

- OAS

- Old Age Security

- OASIS

- Occupational and Skills Information System

- OSC

- Outreach Support Centre

- PAAR

- Payment Accuracy Review

- PEAQ

- Processing Excellence, Accuracy and Quality

- P.p.

- Percentage point

- PPE

- Premium-paid eligible individuals

- PRAR

- Processing Accuracy Review

- PRP

- Premium Reduction Program

- PTs

- Provinces and Territories

- QPIP

- Quebec Parental Insurance Plan

- RAIS

- Registered Apprenticeship Information System

- RCMP

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- R&I

- Research and Innovation

- ROE

- Record of employment

- ROE Web

- Record of employment on the web

- RPA

- Robotics Process Automation

- SAT

- Secure Automated Transfer

- SCC

- Service Canada Centre

- SCT

- Skills and Competency Taxonomy

- SD

- Skills Development

- SD-A

- Skills Development – Apprenticeship

- SD-R

- Skills Development – Regular

- SDP

- Service Delivery Partner

- SE

- Self-Employment

- SEPH

- Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours

- SFS

- Skills for Success

- SIN

- Social Insurance Number

- SIP

- Sectoral Initiatives Program

- SIR

- Social Insurance Registry

- SRS

- Simple Random Sampling

- SST

- Social Security Tribunal

- SST-GD-EI

- Employment Insurance Section of the General Division of the Social Security Tribunal

- STDP

- Short-term disability plan

- STVC

- Status Vector

- SUB

- Supplemental Unemployment Benefit

- SWSP

- Sectoral Workforce Solutions Program

- TES

- Targeted Earning Supplements

- TIS

- Telephone Interpretation Service

- TRF

- Targeting, Referral and Feedback

- TTY

- Teletypewriter

- TWS

- Targeted Wage Subsidies

- U

- Unemployed

- UC

- Unemployed contributor

- UV

- Unemployment-to-job-vacancy

- VBW

- Variable Best Weeks

- VER

- Variable Entrance Requirement

- VRI

- Video Remote Interpretation

- WCAG

- Web Content Accessibility Guidelines

- WISE

- Work Integration Social Enterprises

- WWC

- Working While on Claim

List of figures

- Chart 1. Quarterly real gross domestic product, Canada, 2020‑21 to 2022‑23

- Chart 2. Change in real gross domestic product by industry, Canada, 2021‑22 to 2022‑23

- Chart 3. Year over year change in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), Canada, January 2010 to March 2023, not seasonally adjusted

- Chart 4. Change in employment by industry, Canada, 2021‑22 to 2022‑23

- Chart 5. Unemployment rate, Canada, April 2019 to March 2023

- Chart 6. Average duration of unemployment (in weeks) and share of long-term unemployment (% unemployed 52 weeks or more), Canada, April 2019 to March 2023

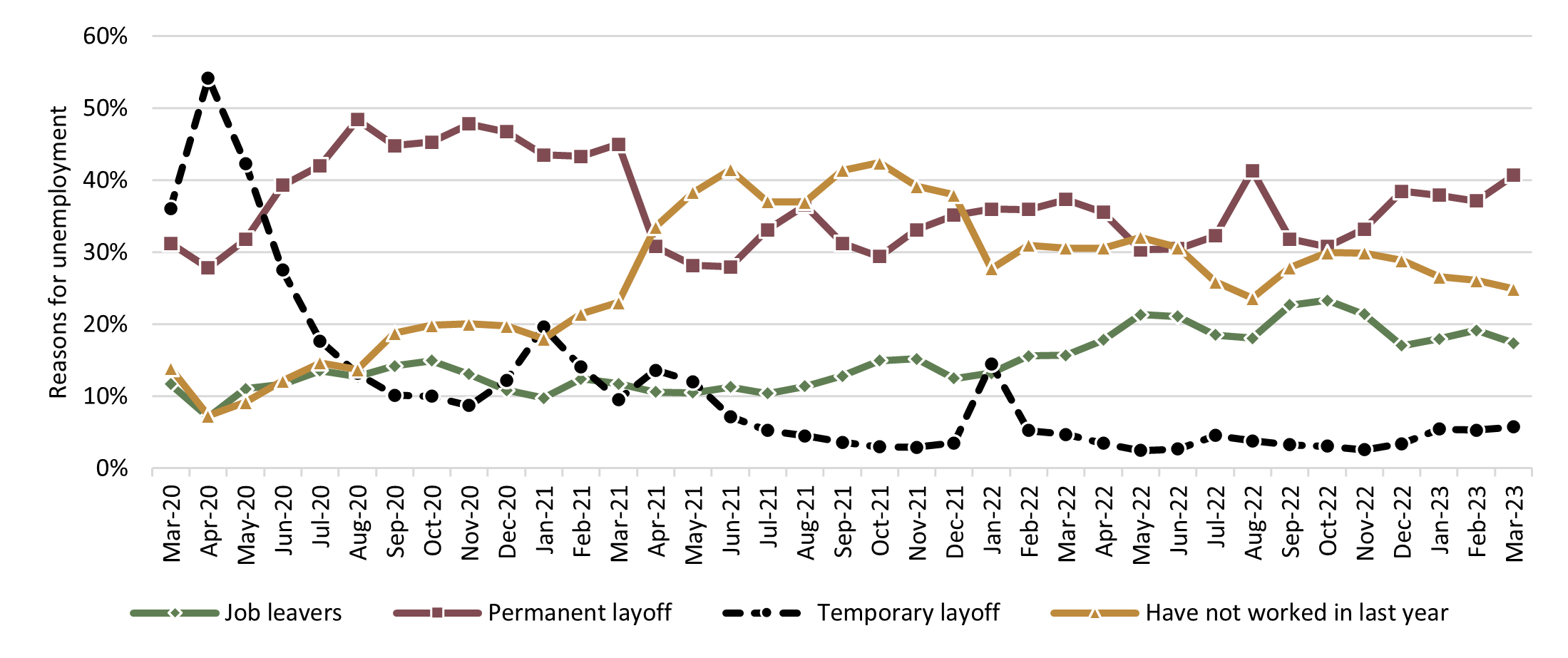

- Chart 7. Share of unemployment by reason for unemployment, Canada, March 2020 to March 2023

- Chart 8. Job vacancies and job vacancy rates, Canada, third quarter of 2020‑21* to fourth quarter of 2022‑23

- Chart 9. Unemployment-to-vacancy ratio, Canada, 2021‑22 to 2022‑23

- Chart 10. Average monthly nominal and real hourly wage, Canada, April 2021 to March 2023

- Chart 11. Unemployment-to-vacancy ratio by province, first quarter of 2022‑23 and fourth quarter of 2022‑23

List of tables

- Table 1. Job vacancies and job vacancy rates, by industry, Canada, fourth quarter of 2021‑22 and 2022‑23

- Table 2. Change in labour force and labour force participation rate, by province or territory, Canada, 2021‑22 to 2022‑23

- Table 3. Change in employment and employment rate, by province or territory, Canada, 2021‑22 to 2022‑23

- Table 4. Change in unemployment and unemployment rate, by province or territory, Canada, 2021‑22 to 2022‑23

- Table 5. Average duration of unemployment, by province, Canada, 2021‑22 to 2022‑23

- Table 6. Nominal weekly earnings, weekly hours worked and consumer price index by province or territory, Canada, 2021‑22 to 2022‑23

- Table 7. Change in number of job vacancies, job vacancy rate and unemployment-to-vacancy ratio, by province and territory, Canada, 2022‑23

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the economic situation and key labour market developments in Canada during the fiscal year beginning on April 1, 2022 and ending on March 31, 2023 (2022‑23).Footnote 1 This is the same period for which this Report assesses the Employment Insurance (EI) program. Section 1.1 provides a general overview and context of the economic situation for 2022‑23. Section 1.2 summarizes key labour market developments in the Canadian economy during the reporting period.Footnote 2 Section 1.3 concentrates on the evolution of regional labour market conditions. Definitions and more detailed statistical tables related to key labour market concepts discussed in the chapter can be found in Annex 1.

1.1 Economic overviewFootnote 3

Global economic development

The beginning of 2022‑23 saw slower growth and rising inflation across the global economy, something that has not been seen since the 1970s.Footnote 4 The war in Ukraine, combined with lingering supply chain disruptions caused by the COVID‑19 pandemic, caused a sharp rise in energy and food prices world-wide. Unprecedented levels of inflation were observed globally in the first half of 2022 (consult Chart 3, for Canada).

During 2022‑23, central banks increased their interest rates while supply chain pressures eased and energy prices declined in early 2023. These factors all contributed to bring global inflation down from its peak, but it remained above target in most G7 countries – a group consisting of the world’s major industrialized and advanced countries including Canada.Footnote 5 Nonetheless, Canada had a lower rate of inflation (6.6%) than the G7 average (7.1%) over the 2022‑23 period.Footnote 6

Canadian economic context in 2022‑23

Following the strong recovery in fiscal year 2021‑22, the Canadian economy experienced a slowdown in growth in 2022‑23. The real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased by 3.2% compared to 2021‑22, while it had increased by 5.7% in 2021‑22 compared to 2020‑21.Footnote 7

Looking at quarterly movements, the Canadian economy remained resilient during the first 2 quarters of 2022‑23. Economic growth halted in the third quarter (-0.1%), as businesses and households adjusted to higher borrowing costsFootnote 8, but growth resumed in the last quarter of 2022‑23 (consult Chart 1).

On the international horizon, Canada had the highest growth rate in real GDP among G7 countries in 2022‑23Footnote 9 compared to 2021‑22, and ranked third among G7 nations in terms of real GDP per capita (using fixed Purchasing Power Parity) with roughly US$46,359 per capita on average over 2022‑23.Footnote 10

Text description for chart 1

| Quarter | Real GDP at market prices ($ trillion, chained 2012 dollars) (left scale) | Change in real GDP at market prices, chained 2012 dollars (annualized quarterly percentage change) (right scale) |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 2020‑21 | 1.85 | -37.1% |

| Q2 2020‑21 | 2.02 | 41.3% |

| Q3 2020‑21 | 2.06 | 8.8% |

| Q4 2020‑21 | 2.09 | 5.3% |

| Q1 2021‑22 | 2.08 | -2.3% |

| Q2 2021‑22 | 2.11 | 5.8% |

| Q3 2021‑22 | 2.14 | 6.9% |

| Q4 2021‑22 | 2.16 | 2.6% |

| Q1 2022‑23 | 2.17 | 3.6% |

| Q2 2022‑23 | 2.19 | 2.3% |

| Q3 2022‑23 | 2.19 | -0.1% |

| Q4 2022‑23 | 2.20 | 2.6% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36‑10‑0104‑01.

As noted in the 2021‑22 Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessing ReportFootnote 11, the post pandemic recovery remained uneven across industries during the 2022‑23 period. All industries registered a positive growth between 2021‑22 and 2022‑23. The sectors with the highest growth in 2022‑23 were Accommodation and food services (+19.1%), Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting (+13.1%) and Transportation and warehousing (+13.1%) (consult Chart 2). However, Accommodation and food services as well as Transportation and warehousing were among the few sectors still lagging compared to their pre pandemic levels (respectively -6.2% and -8.2% in March 2023 compared to February 2020).

Text description for chart 2

| Industry | Change in real GDP 2021‑22 to 2022‑23 |

|---|---|

| Accommodation and food services | 19.1% |

| Transportation and warehousing | 13.1% |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | 13.1% |

| Other services (except public administration) | 8.0% |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 8.0% |

| Information and culture and recreation** | 7.9% |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction | 5.9% |

| Public administration | 2.7% |

| Business, building and other support services* | 2.7% |

| Educational services | 2.6% |

| Manufacturing | 2.5% |

| Health care and social assistance | 2.2% |

| Utilities | 1.1% |

| Construction | 0.9% |

| Finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing | 0.3% |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 0.3% |

- * Includes management of companies and enterprises and administrative and support, waste management and remediation services.

- ** Includes information and cultural industries and arts, entertainment and recreation industries.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36‑10‑0434‑01.

Although the inflation rate in Canada was lower than the G7 average, it rose well above the target level of 2% set by the Bank of Canada in 2022‑23, especially in the first 2 quarters. The year-over-year rate of increase of the Consumer Price Index (CPI), or CPI inflation, peaked in June 2022 at 8.1% (consult Chart 3). Over the calendar year 2022, the CPI inflation was on average 6.8%, which represented a 40 year high.

In response to rising inflation, the Bank of Canada increased its policy interest rate 7 times over 2022‑23, for a total increase of 4 percentage points (p.p.), from 0.75% to 4.75%. Towards the end of 2022‑23, the impact of these rate hikes started to materialize with CPI inflation lowering to 4.3% in March 2023. In general, the purpose of policy interest rate hikes is to reduce aggregate demand to help slow down the economic activity, and which could have an impact on unemployment levels.

Text description for chart 3

| Month | 12‑month CPI change rate |

|---|---|

| Jan-10 | 1.9% |

| Feb-10 | 1.6% |

| Mar-10 | 1.4% |

| Apr-10 | 1.8% |

| May-10 | 1.4% |

| Jun-10 | 1.0% |

| Jul-10 | 1.8% |

| Aug-10 | 1.7% |

| Sep-10 | 1.9% |

| Oct-10 | 2.4% |

| Nov-10 | 2.0% |

| Dec-10 | 2.4% |

| Jan-11 | 2.3% |

| Feb-11 | 2.2% |

| Mar-11 | 3.3% |

| Apr-11 | 3.3% |

| May-11 | 3.7% |

| Jun-11 | 3.1% |

| Jul-11 | 2.7% |

| Aug-11 | 3.1% |

| Sep-11 | 3.2% |

| Oct-11 | 2.9% |

| Nov-11 | 2.9% |

| Dec-11 | 2.3% |

| Jan-12 | 2.5% |

| Feb-12 | 2.6% |

| Mar-12 | 1.9% |

| Apr-12 | 2.0% |

| May-12 | 1.2% |

| Jun-12 | 1.5% |

| Jul-12 | 1.3% |

| Aug-12 | 1.2% |

| Sep-12 | 1.2% |

| Oct-12 | 1.2% |

| Nov-12 | 0.8% |

| Dec-12 | 0.8% |

| Jan-13 | 0.5% |

| Feb-13 | 1.2% |

| Mar-13 | 1.0% |

| Apr-13 | 0.4% |

| May-13 | 0.7% |

| Jun-13 | 1.2% |

| Jul-13 | 1.3% |

| Aug-13 | 1.1% |

| Sep-13 | 1.1% |

| Oct-13 | 0.7% |

| Nov-13 | 0.9% |

| Dec-13 | 1.2% |

| Jan-14 | 1.5% |

| Feb-14 | 1.1% |

| Mar-14 | 1.5% |

| Apr-14 | 2.0% |

| May-14 | 2.3% |

| Jun-14 | 2.4% |

| Jul-14 | 2.1% |

| Aug-14 | 2.1% |

| Sep-14 | 2.0% |

| Oct-14 | 2.4% |

| Nov-14 | 2.0% |

| Dec-14 | 1.5% |

| Jan-15 | 1.0% |

| Feb-15 | 1.0% |

| Mar-15 | 1.2% |

| Apr-15 | 0.8% |

| May-15 | 0.9% |

| Jun-15 | 1.0% |

| Jul-15 | 1.3% |

| Aug-15 | 1.3% |

| Sep-15 | 1.0% |

| Oct-15 | 1.0% |

| Nov-15 | 1.4% |

| Dec-15 | 1.6% |

| Jan-16 | 2.0% |

| Feb-16 | 1.4% |

| Mar-16 | 1.3% |

| Apr-16 | 1.7% |

| May-16 | 1.5% |

| Jun-16 | 1.5% |

| Jul-16 | 1.3% |

| Aug-16 | 1.1% |

| Sep-16 | 1.3% |

| Oct-16 | 1.5% |

| Nov-16 | 1.2% |

| Dec-16 | 1.5% |

| Jan-17 | 2.1% |

| Feb-17 | 2.0% |

| Mar-17 | 1.6% |

| Apr-17 | 1.6% |

| May-17 | 1.3% |

| Jun-17 | 1.0% |

| Jul-17 | 1.2% |

| Aug-17 | 1.4% |

| Sep-17 | 1.6% |

| Oct-17 | 1.4% |

| Nov-17 | 2.1% |

| Dec-17 | 1.9% |

| Jan-18 | 1.7% |

| Feb-18 | 2.2% |

| Mar-18 | 2.3% |

| Apr-18 | 2.2% |

| May-18 | 2.2% |

| Jun-18 | 2.5% |

| Jul-18 | 3.0% |

| Aug-18 | 2.8% |

| Sep-18 | 2.2% |

| Oct-18 | 2.4% |

| Nov-18 | 1.7% |

| Dec-18 | 2.0% |

| Jan-19 | 1.4% |

| Feb-19 | 1.5% |

| Mar-19 | 1.9% |

| Apr-19 | 2.0% |

| May-19 | 2.4% |

| Jun-19 | 2.0% |

| Jul-19 | 2.0% |

| Aug-19 | 1.9% |

| Sep-19 | 1.9% |

| Oct-19 | 1.9% |

| Nov-19 | 2.2% |

| Dec-19 | 2.2% |

| Jan-20 | 2.4% |

| Feb-20 | 2.2% |

| Mar-20 | 0.9% |

| Apr-20 | -0.2% |

| May-20 | -0.4% |

| Jun-20 | 0.7% |

| Jul-20 | 0.1% |

| Aug-20 | 0.1% |

| Sep-20 | 0.5% |

| Oct-20 | 0.7% |

| Nov-20 | 1.0% |

| Dec-20 | 0.7% |

| Jan-21 | 1.0% |

| Feb-21 | 1.1% |

| Mar-21 | 2.2% |

| Apr-21 | 3.4% |

| May-21 | 3.6% |

| Jun-21 | 3.1% |

| Jul-21 | 3.7% |

| Aug-21 | 4.1% |

| Sep-21 | 4.4% |

| Oct-21 | 4.7% |

| Nov-21 | 4.7% |

| Dec-21 | 4.8% |

| Jan-22 | 5.1% |

| Feb-22 | 5.7% |

| Mar-22 | 6.7% |

| Apr-22 | 6.8% |

| May-22 | 7.7% |

| Jun-22 | 8.1% |

| Jul-22 | 7.6% |

| Aug-22 | 7.0% |

| Sep-22 | 6.9% |

| Oct-22 | 6.9% |

| Nov-22 | 6.8% |

| Dec-22 | 6.3% |

| Jan-23 | 5.9% |

| Feb-23 | 5.2% |

| Mar-23 | 4.3% |

- Note: The shaded band indicates Bank of Canada’s 1-3% control range for the inflation target with inflation measured as the 12‑month rate of change in the consumer price index (CPI), Bank of Canada, Monetary Policy Report, July 2023.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Table 18‑10‑0004‑01.

1.2 The Canadian labour market

This section highlights key labour market developments in CanadaFootnote 12 during 2022‑23, including a number of elements related to the administration of the EI program. Overall, the Canadian labour market was characterised by strong employment growth, a low national unemployment rate and tighter labour market conditions.Footnote 13Footnote 14

Labour force and participation rate

For the first time in Canada's history, the population increased by more than 1 million individuals in 2022, international migration accounting for almost 96% if this growth.Footnote 15 The size of Canada's labour forceFootnote 16 increased by 1.5% (+315,917, from 20.6 million to 20.9 million) from 2021‑22 to 2022‑23. During the 12‑month period of 2022‑23, the growth in the size of the population aged 15 years old and over (+1.6%) slightly outpaced that of the labour force (+1.5%), leaving the participation rate unchanged at 65.5% in 2022‑23.

However, behind this unchanged national participation rate, there were changes in the participation rates of individuals by age, in particular an increase in the participation rate of individuals who are less than 55 years old and a decrease for those who are 55 years old and over. The population of individuals aged 15 to 24 years old increased by 0.9% while their labour force increased by 1.8%, leading to an increase in the participation rate (+0.6 p.p.). A similar trend was observed for individuals aged 25 to 54 years old where their population increased by 1.4% while their labour force increased by 2.1%, leading to an increase in the participation rate (+ 0.6 p.p.). Conversely, because of population aging, the population of individuals 55 years old and over increased the most (+1.7%), while their labour force decreased by 0.1%, leading to a reduction in their participation rate (‑0.7 p.p.).

Employment and employment rate

During the reporting period, total employment continued a gradual upward trend, increasing from 19.6 million in March 2022 to 20.1 million in March 2023 (+1.9%). The number of part‑time employees decreased by 35,600 (-1.0%) while full‑time employees increased by 472,100 (+2.9%) over the same period. Employment growth was slightly higher in the private sector (+2.3%) than in the public sector (+1.6%). Self‑employment increased by 0.7%, reaching almost 2.7 million in March 2023, which is close to the pre‑pandemic level of 2.8 million in February 2020. During 2022‑23, employment increased in large‑sized enterprisesFootnote 17 (500 employees and over) but decreased for all other sizes of enterprises.Footnote 18 Large‑sized enterprises accounted for nearly half of all employed individuals (46.9% in the last quarter of 2022‑23).

Between 2021‑22 and 2022‑23, most industry sectors experienced employment growth, although many had still not returned to their pre-pandemic levels. The 3 broad sectors with the biggest employment increases during the reporting period were Accommodation and food services (+9.7%), Information, culture and recreation (+9.3%) and Utilities (+8.7%) while Transportation and warehousing (-1.1%) and Forestry, fishing, mining, quarrying, oil and gas (-0.4%) were the only 2 sectors that registered a decrease in employment (consult Chart 4).

Text description for chart 4

| Industry | Change (%) in employment by industry 2021‑22 to 2022‑23 |

|---|---|

| Transportation and warehousing | -1.1% |

| Forestry, fishing, mining, quarrying, oil and gas | -0.4% |

| Educational services | 0.7% |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 1.1% |

| Other services (except public administration) | 1.5% |

| Manufacturing | 1.6% |

| Business, building and other support services | 2.1% |

| Agriculture | 2.5% |

| Health care and social assistance | 2.5% |

| Finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing | 3.0% |

| Total employed, all industries | 3.4% |

| Public administration | 5.3% |

| Construction | 7.0% |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 7.0% |

| Utilities | 8.7% |

| Information, culture and recreation | 9.3% |

| Accommodation and food services | 9.7% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14‑10‑0355‑01.

In terms of employment breakdowns by age, individuals aged 15 to 24 had the biggest increase in employment (+4.2%) in 2022‑23 compared to 2021‑22, followed by 25 to 54 years old (+3.5%) and 55 years and over (+2.7%). Even though the 55 years and over age group was the only group with a decrease in its labour force, their employment numbers increased nonetheless.

Over the 2022‑23 period, males represented on average 56.0% of full‑time employees while females represented 44.0%. Conversely, female represented 64.2% of part‑time employees on average while men represented 35.8%. These shares were similar for 2021‑22 where males represented 56.1% of full-time employees and 37.0% of part‑time employees, while females represented 43.9% of full‑time employees and 63.0% of part-time employees on average. Full‑time employment increased by 3.5% for males between 2021‑22 and 2022‑23, and by 4.1% for females. Part‑time employment decreased by 1.8% for males while it increased by 3.1% for females.

The changing nature of work since the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic

A recent study* from Statistics Canada examined trends in the nature of work. Looking back 3 decades before the pandemic, the study found a gradual shift in the nature of work in Canada. Globalization and technology caused employment to move from routine manual tasks to non‑routine, cognitive tasks.

This trend began to accelerate during the pandemic. The study found that between 2019 and 2022, the increase in managerial, professional and technical occupations (non‑routine, cognitive tasks) was similar for men and women. However, men saw a decrease in production, craft, repair and operative occupations (routine, manual tasks) whereas women had a decrease in service occupations (non‑routine, manual tasks). The report also showed that the increase in occupations with non‑routine, cognitive tasks among younger workers (25 to 34 years old) was nearly double that of older workers (45 to 54 years old). As the author points out, "the trends by age group may provide insight into future trends".

- *Statistics Canada, The changing nature of work since the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic, Ottawa: Statistics Canada, Economic and Social Report. Vol. 3, No.7, 2023

The increase in the total number of employed individuals does not take into consideration how it compares to the growth in working‑age population. The employment rate, which is the proportion of people aged 15 years and over who were employed, accounts for changes in the working‑age population.

The employment rate increased by 1.1 p.p. and reached 62.2% in 2022‑23 compared to 2021‑22, still below its highest level of 63.2% recorded in 2007‑08. Both men and women had higher employment rates in 2022‑23 compared to the previous fiscal year (+0.9 p.p. and +1.3 p.p. respectively). By age group, the youth aged 15 to 24 years registered the highest increase (+1.9 p.p.) and reached 59.0%. This was closely followed by those aged 25 to 54 years, who registered an increase of 1.6 p.p. settling at 84.9%. Lastly, those aged 55 years and over had the smallest increase (+0.3 p.p.). They also had the lowest employment rate across all age groups (35.1% for 2022‑23). Compared to other G7 countries, Canada ranked first in terms of employment rate throughout 2022‑23.Footnote 19

Unemployment and unemployment rate

Unemployment rate is one of the core elements that determines eligibility for EI regular benefits. Under the original EI rulesFootnote 20, a lower unemployment rate in an EI economic region translates into a higher required number of hours of insurable employment within the qualifying period to be eligible for EI regular benefits. The unemployment rate in an EI economic region also plays a role in determining the EI regular benefit entitlement available to a claimant and the number of weeks of insurable earnings (known as the divisor) used in the calculation of their weekly benefit rate. Regional variations of the unemployment rate are discussed in subsection 1.3.

The number of unemployed individuals decreased from 1.4 million in 2021‑22 to 1.1 million in 2022‑23, a reduction of 24.2%. Combined with the increase in the size of the labour force during the same period, the unemployment rate fell from 6.8% in 2021‑22 to 5.1% in 2022‑23. In 2022‑23, women had a slightly lower unemployment rate than men (4.9% vs 5.2%). The decrease in unemployment rate was almost identical for men (-1.8 p.p.) and women (‑1.7 p.p.). In 2022‑23, the youth had the highest unemployment rate of 9.8%, compared to 4.2% for those aged 25 to 54 years old and 4.6% for those aged 55 years and over. By age group, individuals aged 55 year and over had the biggest reduction in their unemployment rate (-2.6 p.p.) compared to 2021‑22. This was followed by those aged 15 to 24 years old (‑2.1 p.p.).

The monthly unemployment rate reached 5.4% in March 2022, which was considered a historical low at the time. During 2022‑23, it continued to trend down and ended at 5.1% in March 2023 (consult Chart 5).

Text description for chart 5

| Month | Unemployment rate (%) |

|---|---|

| Apr-19 | 5.7% |

| May-19 | 5.4% |

| Jun-19 | 5.6% |

| Jul-19 | 5.8% |

| Aug-19 | 5.8% |

| Sep-19 | 5.6% |

| Oct-19 | 5.6% |

| Nov-19 | 5.9% |

| Dec-19 | 5.6% |

| Jan-20 | 5.5% |

| Feb-20 | 5.7% |

| Mar-20 | 8.4% |

| Apr-20 | 13.6% |

| May-20 | 14.1% |

| Jun-20 | 12.4% |

| Jul-20 | 11.0% |

| Aug-20 | 10.2% |

| Sep-20 | 9.2% |

| Oct-20 | 9.0% |

| Nov-20 | 8.7% |

| Dec-20 | 8.9% |

| Jan-21 | 9.2% |

| Feb-21 | 8.5% |

| Mar-21 | 7.7% |

| Apr-21 | 8.2% |

| May-21 | 8.3% |

| Jun-21 | 7.9% |

| Jul-21 | 7.4% |

| Aug-21 | 7.1% |

| Sep-21 | 7.0% |

| Oct-21 | 6.5% |

| Nov-21 | 6.1% |

| Dec-21 | 5.9% |

| Jan-22 | 6.5% |

| Feb-22 | 5.5% |

| Mar-22 | 5.4% |

| Apr-22 | 5.3% |

| May-22 | 5.2% |

| Jun-22 | 5.0% |

| Jul-22 | 4.8% |

| Aug-22 | 5.2% |

| Sep-22 | 5.1% |

| Oct-22 | 5.1% |

| Nov-22 | 5.1% |

| Dec-22 | 5.0% |

| Jan-23 | 5.0% |

| Feb-23 | 5.1% |

| Mar-23 | 5.1% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14‑10‑0287‑01.

Factors influencing the job search strategies of unemployed Canadians

A recent departmental study* investigated the job search methods of unemployed Canadians to better understand the determining factors behind these methods, and examine their effectiveness in terms of re‑employment. The study looked at Labour Force Survey data from 2015 to 2022. Over this period, the most frequently used job search method was looking at job ads. However, over time some job searchers have embraced more diversified job search strategies. For instance, the percentage of individuals utilizing a single method decreased from 43.3% to 32.9%, whereas those employing 3 methods increased from 15.9% to 20.8%.

The study also found that job searchers who prefer active methods (such as contacting employers directly) are more likely to use multiple job search methods. Conversely, single method job searchers used a more passive method, such as looking at job ads. Younger individuals, notably those aged 15‑44, demonstrated higher job search intensity by combining multiple methods. Additionally, higher educational attainment was associated with increased job search intensity.

On average, 20.4% of unemployed people who were looking for jobs successfully found one in the subsequent month during the period of 2015 to 2019.** Active job search methods resulted in a higher re‑employment rate (for example 22.6% for those who directly contacted employers) than passive methods (for example 19.1% for those who only looked at job ads). Additionally, the re‑employment rates varied among EI‑eligible and non-EI‑eligible job searchers over the same period (24.8% vs. 18.6%).

- * ESDC, Factors influencing the job search strategies of unemployed Canadians, (Ottawa: ESDC, Labour Market Information Directorate, 2024).

- ** The 2015 to 2019 period was used in this section of the study to separate the impact of COVID-related emergency measures from the pre 2020 period.

Duration of unemploymentFootnote 21

Along with the decrease in the national unemployment rate in 2022‑23, 2 indicators measuring unemployment duration also exhibited downward trends.

First, the average duration of unemployment spells (the number of continuous weeks of unemployment where an individual is looking for work or is on temporary layoff) decreased compared to the previous period. On an annual basis, it fell from an average of 22.3 weeks in 2021‑22 to 18.7 weeks in 2022‑23, representing a reduction of 3.6 weeks in the average duration of unemployment spells (consult Chart 6). This was almost back to the pre‑pandemic average of 16.1 weeks in 2019‑20. Most labour market indicators were already back to their pre‑pandemic levels at the beginning of 2022‑23, but the average duration of unemployment spells was one of the few that had not.

Second, the share of long‑term unemployment (continuously looking for work for 52 weeks or moreFootnote 22) continued its downward trend that started in 2021‑22. On an annual basis, the share of long‑term unemployment was 9.6% in 2022‑23, down by 6.4 p.p. from 15.9% in 2021‑22. This was closer to the pre‑pandemic share of 7.5% in 2019‑20. In absolute terms, this represented a decrease from 129,000 long‑term unemployed in March 2022 to 96,900 in March 2023. Among G7 countries, Canada reported in 2022 the lowest proportion of unemployment lasting for one year or over.Footnote 23

Text description for chart 6

| Month | Average weeks of unemployment spells (left scale) | Share of long-term unemployment (%) (right scale) |

|---|---|---|

| Apr-19 | 16.8 | 8.1% |

| May-19 | 16.3 | 8.0% |

| Jun-19 | 16.2 | 7.1% |

| Jul-19 | 16.8 | 8.1% |

| Aug-19 | 15.8 | 7.4% |

| Sep-19 | 15.5 | 6.7% |

| Oct-19 | 17.0 | 7.7% |

| Nov-19 | 16.1 | 7.3% |

| Dec-19 | 16.4 | 7.8% |

| Jan-20 | 17.4 | 8.6% |

| Feb-20 | 16.7 | 8.4% |

| Mar-20 | 11.7 | 5.4% |

| Apr-20 | 8.7 | 2.8% |

| May-20 | 11.1 | 3.0% |

| Jun-20 | 13.0 | 3.7% |

| Jul-20 | 16.1 | 4.4% |

| Aug-20 | 17.0 | 4.8% |

| Sep-20 | 20.1 | 5.5% |

| Oct-20 | 18.8 | 6.2% |

| Nov-20 | 18.6 | 5.9% |

| Dec-20 | 20.5 | 7.3% |

| Jan-21 | 21.0 | 8.7% |

| Feb-21 | 21.5 | 10.0% |

| Mar-21 | 22.6 | 16.1% |

| Apr-21 | 21.8 | 18.7% |

| May-21 | 21.9 | 17.9% |

| Jun-21 | 24.1 | 18.5% |

| Jul-21 | 24.0 | 18.1% |

| Aug-21 | 23.4 | 16.9% |

| Sep-21 | 23.7 | 16.7% |

| Oct-21 | 25.0 | 17.3% |

| Nov-21 | 22.0 | 13.8% |

| Dec-21 | 21.3 | 13.2% |

| Jan-22 | 20.6 | 12.6% |

| Feb-22 | 19.7 | 11.7% |

| Mar-22 | 19.8 | 11.6% |

| Apr-22 | 21.1 | 12.8% |

| May-22 | 20.0 | 10.4% |

| Jun-22 | 19.0 | 10.8% |

| Jul-22 | 19.6 | 9.4% |

| Aug-22 | 19.2 | 9.0% |

| Sep-22 | 17.8 | 8.8% |

| Oct-22 | 17.2 | 8.8% |

| Nov-22 | 18.2 | 8.8% |

| Dec-22 | 18.4 | 8.0% |

| Jan-23 | 17.6 | 10.0% |

| Feb-23 | 18.1 | 8.7% |

| Mar-23 | 17.6 | 9.0% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14‑10‑0342‑01.

Individuals aged 55 years and over are generally more likely to have longer durations of unemployment. Over 2022‑23, the average duration of unemployment was higher among those aged 55 and over (27.9 weeks) as opposed to the core‑age population (19.7 weeks) and youth (10.0 weeks). The duration decreased by 1.5 weeks, 3.8 weeks and 2.9 weeks respectively for these 3 groups compared to 2021‑22. Similarly, over the same 12‑month period, the share of long-term unemployed was 15.2% among those aged 55 and over, compared to 10.6% among the core‑age and 3.5% among youth. This represented a decrease of 7.9 p.p., 6.2 p.p. and 3.8 p.p. respectively for these 3 groups compared to 2021‑22.

The share of long‑term unemployment was similar for men and women. It reached 10.3% for men compared to 8.7% for women in 2022‑23. Compared to 2021‑22, the share of long-term unemployment decreased by 6.4 p.p. for men and 6.3 p.p. for women. Between 2021‑22 and 2022‑23, unemployment duration decreased by 3.6 weeks for both men and women, with an annual average in 2022‑23 of 19.6 weeks and 17.6 weeks respectively.

The long-term unemployed and EI, a profile and training participation

A recent departmental study* examined the evolution of the long-term unemployment** in Canada from 2006 to 2022 using Labour Force Survey data. The study examined the long-term unemployment rate*** and its relationship to the overall unemployment rate and examined these concepts for several key periods of reference, including the 2008‑09 recession, the oil crisis of the mid-2010s and the COVID-19 pandemic. The study also examined the issue from gender, age and geographic perspectives, and identified which groups historically experienced higher rates of long-term unemployment.

Overall, there is usually a delay of 10 to 12 months between cycles observed in the long-term unemployment rate and the total unemployment rate. However, after a period of economic disruptions, the long-term unemployment rate tends to take significantly longer than the total unemployment rate to return to levels observed before the economic shock.

In terms of gender, men were proportionally more represented than women in long-term unemployment during the majority of the reference period, with a higher rate of long-term unemployment in 62 of the 68 quarters analyzed. Additionally, on average over the entire reference period, men accounted for 59.9% of long-term unemployed individuals, compared to 56.1% of total unemployment and 52.8% of the labour force.

Individuals aged 55 years and over had the highest long-term unemployment rate in all 68 quarters of the reference period. This group's share of labour force, total unemployment and long-term unemployment all gradually increased over the reference period for, but its share of long-term unemployment increased at a higher rate.

In terms of geography, Newfoundland and Labrador and Ontario had long-term unemployment rates above the national average for the majority of the reference period. In addition, Alberta and Saskatchewan exhibited high rates of long-term unemployment relative to the national average since the oil crisis of the mid-2010s.

- * ESDC, The long-term unemployed and EI, a profile and training participation (Ottawa: ESDC, Employment Insurance Policy Directorate, 2024).

- ** In the study, long-term unemployment is defined as individuals who are unemployed continuously for 52 weeks or more. In certain sections, a definition of 27 weeks of continuous unemployment is used due to small sample sizes.

- *** The long-term unemployment rate refers to the share of long-term unemployment among the unemployed population.

Reason for unemploymentFootnote 24

In general, workers can become unemployed for a number of reasons, and the cause of unemployment is a key factor in determining if the individual is eligible for EI benefits. EI regular benefits are only available to individuals who have lost their job for reasons outside their control or who left their job with just cause.

In the Labour Force Survey, 5 categories of reasons for unemploymentFootnote 25 are reported: job leavers, permanent layoff, temporary layoff, not worked last year and never worked. Among these, the permanent and temporary layoff are most relevant to the administration of the EI program. However, the pandemic led many individuals to lose their jobs and remain unemployed. This caused a higher proportion of unemployed individuals who did not work in the last year among the unemployed population. In the beginning of 2021‑22, there was a significant increase in the number of unemployed individuals who did not work in the last 52 weeks, which implied that these individuals lost their jobs in the beginning of the pandemic and had not yet resumed working since. Towards the end of 2021‑22, this share started to decrease, and it continued in 2022‑23. The share of unemployed individuals who did not work in the last year was down from 30.6% in April 2022 to 24.9% in March 2023.

For most of 2022‑23, unemployment because of permanent layoffs represented the largest share of all unemployment (35.0% on average for 2022‑23), which is in line with the reasons for unemployment provided before the pandemic. The share of unemployment because of temporary layoffs, which had increased in the last 2 fiscal years (2020‑21 and 2021‑22), also reverted to pre-pandemic levels (3.8% on average for 2022‑23). Lastly, the share of job leavers, which had decreased during the last 2 fiscal years, increased back to pre-pandemic levels (19.6% on average for 2022‑23).

Text description for chart 7

| Month | Job leavers | Permanent layoff | Temporary layoff | Have not worked in last year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mar-20 | 12% | 31% | 36% | 14% |

| Apr-20 | 7% | 28% | 54% | 7% |

| May-20 | 11% | 32% | 42% | 9% |

| Jun-20 | 12% | 39% | 28% | 12% |

| Jul-20 | 14% | 42% | 18% | 15% |

| Aug-20 | 13% | 48% | 13% | 14% |

| Sep-20 | 14% | 45% | 10% | 19% |

| Oct-20 | 15% | 45% | 10% | 20% |

| Nov-20 | 13% | 48% | 9% | 20% |

| Dec-20 | 11% | 47% | 12% | 20% |

| Jan-21 | 10% | 43% | 20% | 18% |

| Feb-21 | 12% | 43% | 14% | 21% |

| Mar-21 | 12% | 45% | 10% | 23% |

| Apr-21 | 11% | 31% | 14% | 34% |

| May-21 | 10% | 28% | 12% | 38% |

| Jun-21 | 11% | 28% | 7% | 41% |

| Jul-21 | 10% | 33% | 5% | 37% |

| Aug-21 | 11% | 37% | 5% | 37% |

| Sep-21 | 13% | 31% | 4% | 41% |

| Oct-21 | 15% | 29% | 3% | 42% |

| Nov-21 | 15% | 33% | 3% | 39% |

| Dec-21 | 12% | 35% | 4% | 38% |

| Jan-22 | 13% | 36% | 14% | 28% |

| Feb-22 | 16% | 36% | 5% | 31% |

| Mar-22 | 16% | 37% | 5% | 31% |

| Apr-22 | 18% | 36% | 3% | 31% |

| May-22 | 21% | 30% | 2% | 32% |

| Jun-22 | 21% | 31% | 3% | 31% |

| Jul-22 | 19% | 32% | 5% | 26% |

| Aug-22 | 18% | 41% | 4% | 24% |

| Sep-22 | 23% | 32% | 3% | 28% |

| Oct-22 | 23% | 31% | 3% | 30% |

| Nov-22 | 21% | 33% | 3% | 30% |

| Dec-22 | 17% | 38% | 3% | 29% |

| Jan-23 | 18% | 38% | 5% | 27% |

| Feb-23 | 19% | 37% | 5% | 26% |

| Mar-23 | 17% | 41% | 6% | 25% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14‑10‑0125‑01, seasonally unadjusted.

Hours of workFootnote 26

Hours of work are closely related to the administration of the EI program. The number of hours of insurable employment is a key eligibility criterion of the EI program, as claimants must have worked a minimum number of insurable hours in the qualifying period to be eligible to receive EI benefits. The number of hours of insurable employment also determines, along with the regional unemployment rate, the maximum number of weeks of EI regular benefits that a claimant is entitled to receive.

The average number of hours usually worked from all jobs by Canadians was 36.6 per week in 2022‑23. This was similar to previous fiscal years, with just a small increase (+0.2 hours) compared to 2021‑22. In contrast, the average number of actual hours worked reflects temporary decreases or increase in work hours, for example, hours lost due to illness or vacation or more hours worked due to overtime. The average actual hours worked per worker from all jobs barely changed between 2021‑22 and 2022‑23, only a small decrease of 0.3% from 32.8 per week in 2021‑22 to 32.7 per week in 2022‑23.

Job vacanciesFootnote 27 and labour market tightness

The number of job vacancies is the number of unoccupied positions for which employers are actively seeking workers, whereas the job vacancy rate is number of job vacancies expressed as a percentage of all occupied and vacant jobs.

The first 2 quarters of 2022‑23 reached unprecedentedly elevated levels of job vacancies and job vacancy rates, higher than the record high in 2021‑22 (consult Chart 8), representing an increase in tightness of the labour market. The first quarter of 2022‑23 hit a historical high of the job vacancy rate at 5.9%. Levels of job vacancies and vacancy rates persistently decreased afterwards. Compared to the last quarter of 2021‑22, the last quarter of 2022‑23 had a decrease of 12.3% in job vacancies and a reduction of 0.8 percentage points in the job vacancy rate.

Text description for chart 8

| Quarter | Job vacancies (in thousands) (left scale) | Job vacancy rate (%) (right scale) |

|---|---|---|

| Q3 2020‑21 | 560.2 | 3.5% |

| Q4 2020‑21 | 553.5 | 3.6% |

| Q1 2021‑22 | 731.9 | 4.6% |

| Q2 2021‑22 | 912.6 | 5.4% |

| Q3 2021‑22 | 915.5 | 5.3% |

| Q4 2021‑22 | 890.4 | 5.2% |

| Q1 2022‑23 | 1,032.0 | 5.9% |

| Q2 2022‑23 | 991.7 | 5.6% |

| Q3 2022‑23 | 855.9 | 4.8% |

| Q4 2022‑23 | 781.2 | 4.4% |

- * Statistics Canada temporarily suspended the data collection of the Job Vacancy and Wage Survey during the first and second quarters of 2020‑21.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Job Vacancy and Wage Survey, Table 14‑10‑0326‑01, seasonally unadjusted.

In the last quarter of fiscal year 2022‑23, a decrease in levels of job vacancies had been observed in most industrial groups, except for Utilities (+7.2%), Educational services (+2.5%) and Health care and social assistance (+6.1%) compared to the last quarter of the previous fiscal year (consult Table 1). Among sectors with lower levels of job vacancies, Information and cultural industries (-27.8%), Manufacturing (-26.8%), and Professional, scientific and technical services (-25.4%) had the highest decreases in the last quarter of 2022‑23 compared to the last quarter of 2021‑22.

The job vacancy rate also decreased for most industrial groups. The strongest decrease was registered in Accommodation and food services industry (-2.6 p.p.), which is in line with the sharp increase in employment observed in this industry. However, this industry still had the highest job vacancy rate of 7.3% in the last quarter of 2022‑23 among all industrial groups (consult Table 1). This is explained in part by a higher employee turnover in this industry which leads to more frequent job postings. Professional, scientific and technical services (‑1.8 p.p.) and Manufacturing (-1.4 p.p.) were the other 2 industries with the strongest decrease in job vacancy rate in the last quarter of 2022‑23 relative to the same quarter in 2021‑22. Health care and social assistance (+0.2 p.p.) and Utilities (+0.1 p.p.) were the only 2 industrial groups who registered an increase of their job vacancy rate between the last quarter of 2022‑23 compared to the same quarter in 2021‑22.

| Industry | Job vacancies Q4 2021‑22 |

Job vacancies Q4 2022‑23 | Job vacancies change (%) Q4 2021‑22 to Q4 2022‑23 |

Job vacancy rate Q4 2021‑22 (%) |

Job vacancy rate Q4 2022‑23 (%) |

Job vacancy rate change (p.p.) Q4 2021‑22 to Q4 2022‑23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | 13,745 | 11,455 | -16.7% | 6.2 | 5.2 | -1.0 |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction | 8,760 | 8,045 | -8.2% | 4.2 | 3.7 | -0.5 |

| Utilities | 2,850 | 3,055 | +7.2% | 2.2 | 2.3 | +0.1 |

| Construction | 72,090 | 64,315 | -10.8% | 6.5 | 5.6 | -0.9 |

| Manufacturing | 82,705 | 60,550 | -26.8% | 5.2 | 3.8 | -1.4 |

| Wholesale trade | 36,105 | 28,730 | -20.4% | 4.3 | 3.4 | -0.9 |

| Retail trade | 85,740 | 73,335 | -14.5% | 4.1 | 3.5 | -0.6 |

| Transportation and warehousing | 44,130 | 43,790 | -0.8% | 5.3 | 5.0 | -0.3 |

| Information and cultural industries | 17,720 | 12,785 | -27.8% | 4.6 | 3.3 | -1.3 |

| Finance and insurance | 35,450 | 30,655 | -13.5% | 4.3 | 3.5 | -0.8 |

| Real estate and rental and leasing | 11,240 | 10,420 | -7.3% | 3.9 | 3.5 | -0.4 |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 69,565 | 51,885 | -25.4% | 5.9 | 4.1 | -1.8 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 4,810 | 4,720 | -1.9% | 3.7 | 3.6 | -0.1 |

| Administrative and support, waste management and remediation services | 57,930 | 47,430 | -18.1% | 6.8 | 5.5 | -1.3 |

| Educational services | 23,505 | 24,100 | +2.5% | 1.6 | 1.6 | 0.0 |

| Health care and social assistance | 135,570 | 143,870 | +6.1% | 5.8 | 6.0 | +0.2 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 15,160 | 13,860 | -8.6% | 6.0 | 4.8 | -1.2 |

| Accommodation and food services | 121,665 | 98,140 | -19.3% | 9.9 | 7.3 | -2.6 |

| Other services (except public administration) | 35,745 | 34,960 | -2.2% | 6.4 | 6.0 | -0.4 |

| Public administration | 15,900 | 15,105 | -5.0% | 3.0 | 2.8 | -0.2 |

| All industries | 890,385 | 781,205 | -12.3% | 5.2 | 4.4 | -0.8 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Job Vacancy and Wage Survey, Table 14‑10‑0326‑01, seasonally unadjusted.

Job vacancies usually become more difficult to fill when the available labour force, primarily unemployed individuals, declines relative to the number of vacant positions. It is said that the labour market is "tightening" in this situation. On the other hand, job vacancies usually become easier to fill when the number of unemployed individuals increases relative to the number of vacant positions in which case, it is said that the tightness of the labour market is easing. An indicator of labour market tightness is the Unemployment‑to‑Vacancy (UV) ratio. It measures the potential number of available unemployed people for every vacant position. A lower UV ratio corresponds to a tighter labour market and as fewer unemployed persons are available to fill vacant positions, it could lead to longer vacancy durations. Conversely, a higher UV ratio corresponds to easing of tightness in the labour market. A comparison of the UV ratio at 2 points of time indicates how labour market conditions evolve over the period.

On an annual basis, there was a downward trend of the UV ratio from 1.7 in 2021‑22 to 1.2 in 2022‑23. Similar to the higher levels of job vacancies and job vacancy rate observed at the beginning of the fiscal year, the first 3 quarters of 2022‑23 had the lowest level of UV ratio, indicating tight labour market conditions during this period. However, the labour market tightness began to ease with a higher UV ratio of 1.4 during the last quarter of 2022‑23 (consult Chart 9).

Text description for chart 9

| Quarter | Unemployment-to-vacancy ratio |

|---|---|

| Q1 2021‑22 | 2.3 |

| Q2 2021‑22 | 1.7 |

| Q3 2021‑22 | 1.3 |

| Q4 2021‑22 | 1.4 |

| Q1 2022‑23 | 1.0 |

| Q2 2022‑23 | 1.1 |

| Q3 2022‑23 | 1.1 |

| Q4 2022‑23 | 1.4 |

- Sources: Statistics Canada, Job Vacancy and Wage Survey, Table 14‑10‑0326‑01, seasonally unadjusted (for job vacancies) and Labour Force Survey, Table 14‑10‑0022‑01 (for unemployment).

WagesFootnote 28

Employment earnings are another important element for the administration of the EI program. They determine the EI premiums paid by employers and employees, as well as the level of benefits that claimants can receive. Employment earnings can be a combination of hourly wages and hours worked, a fixed amount paid for a specific time period (a week, for example) or in the form of commissions, tips or bonuses. Average hourly wages and average weekly earnings are therefore examined.

Wage growth dynamics are linked to a variety of factors, notably labour productivity, labour market tightness, inflation expectations, demographic shifts, structural changes and minimum wage increases. In 2022‑23, the average nominal hourly wage continued its upward trend observed in 2021‑22. It went from $30.72 in April 2021 to $33.12 in March 2023. This was to be expected given labour market tightness, as labour shortages pushed wages higher.Footnote 29 However, in the context of high inflation during that same period, the average real hourly wage slightly decreased in 2022‑23 compared to 2021‑22 (consult Chart 10).

Text description for chart 10

| Month | Average nominal hourly wage rate ($) | Average real hourly wage rate ($) |

|---|---|---|

| Apr-21 | 30.72 | 21.90 |

| May-21 | 30.52 | 21.65 |

| Jun-21 | 30.29 | 21.42 |

| Jul-21 | 30.33 | 21.31 |

| Aug-21 | 30.43 | 21.34 |

| Sep-21 | 30.87 | 21.60 |

| Oct-21 | 30.87 | 21.45 |

| Nov-21 | 30.93 | 21.45 |

| Dec-21 | 31.18 | 21.65 |

| Jan-22 | 31.59 | 21.74 |

| Feb-22 | 31.47 | 21.44 |

| Mar-22 | 31.44 | 21.11 |

| Apr-22 | 31.72 | 21.17 |

| May-22 | 31.64 | 20.83 |

| Jun-22 | 31.8 | 20.80 |

| Jul-22 | 31.65 | 20.67 |

| Aug-22 | 31.91 | 20.91 |

| Sep-22 | 32.38 | 21.20 |

| Oct-22 | 32.52 | 21.14 |

| Nov-22 | 32.71 | 21.24 |

| Dec-22 | 32.67 | 21.34 |

| Jan-23 | 33.01 | 21.45 |

| Feb-23 | 33.16 | 21.46 |

| Mar-23 | 33.12 | 21.33 |

- Sources: Statistics Canada, Consumer Price Index Measures, Table 18‑10‑0004‑01 (for CPI) and Labour Force Survey, Table 14‑10‑0063‑01 (for hourly wage).

Average nominal weekly earnings are influenced not only by the average nominal hourly wage, but also by the number of actual hours worked per week. As mentioned previously, average actual hours worked per week remained relatively stable over the reference period. As a result, average nominal weekly earnings followed the same patterns observed in the average nominal hourly wages. They trended up by 2.9% from $1,139 in 2021‑22 to $1,171 in 2022‑23, equivalent to a $32.91 increase weekly. In real terms, the average weekly earnings declined relative to the increase in the CPI.Footnote 30

1.3 Canada's regional labour market

General labour market developments at the national level may not be consistently observed across regions. This subsection examines labour market developments in Canada at the provincial and territorial level.Footnote 31

Labour force and participation rate

In 2022‑23, each province and territory experienced an increase in its respective labour force compared to 2021‑22. Excluding the territories, Alberta posted the highest growth in the size of its labour force (+2.5%), followed by Nova Scotia (+2.0%) and New Brunswick (+1.7%) over the 2 fiscal years (consult Table 2).

Participation rate at the national level, including the territories, remained stable in 2022‑23 compared to 2021‑22. Northwest Territories (+1.4 p.p.), Nunavut (+1.4 p.p.), Newfoundland and Labrador (+0.3 p.p.) and Quebec (+0.2 p.p.) were the only ones registering a higher increase in participation rate over the 2 fiscal years. The highest decrease in participation rate was registered in Prince Edward Island (-1.7 p.p.) (consult Table 2).

| Province or territory | Change in labour force 2021‑22 to 2022‑23 | Participation rate 2021‑22 | Participation rate 2022‑23 | Change in participation rate (p.p.) 2021‑22 to 2022‑23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | +1.5% | 57.9% | 58.2% | +0.3 |

| Prince Edward Island | +1.1% | 66.6% | 65.0% | -1.7 |

| Nova Scotia | +2.0% | 62.1% | 61.8% | -0.3 |

| New Brunswick | +1.7% | 61.1% | 60.7% | -0.4 |

| Quebec | +1.3% | 64.3% | 64.5% | +0.2 |

| Ontario | +1.5% | 65.5% | 65.4% | 0.0 |

| Manitoba | +1.0% | 67.0% | 66.7% | -0.3 |

| Saskatchewan | +1.3% | 67.8% | 67.6% | -0.2 |

| Alberta | +2.5% | 69.8% | 69.8% | 0.0 |

| British Columbia | +1.2% | 65.3% | 65.1% | -0.3 |

| Yukon | +0.2% | 73.4% | 72.2% | -1.2 |

| Northwest Territories | +2.2% | 74.1% | 75.6% | +1.4 |

| Nunavut | +4.7% | 62.7% | 64.1% | +1.4 |

| Canada* | +1.5% | 65.5% | 65.5% | 0.0 |

- * Figures for Canada’s labour force and participation rate exclude the territories. Percentage change is based on unrounded numbers.

- Sources: Statistics Canada; Labour Force Survey, Table 14‑10‑0287‑01 and 14‑10‑0292‑01, seasonally adjusted data.

Employment and employment rate

Each province and territory experienced growth in employment in 2022‑23 compared to 2021‑22. The greatest employment gains were recorded in Alberta (+4.8%), Prince Edward Island (+4.4%) and Newfoundland and Labrador (+4.4%) (consult Table 3). Over the same 2 fiscal years, the employment rate increased in each province and territory, except for Yukon where it remained barely unchanged. In 2022‑23, employment rates in Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Yukon and Northwest Territories were higher than the national level (consult Table 3).

| Province or territory | Change in employment 2021‑22 to 2022‑23 | Employment rate 2021‑22 | Employment rate 2022‑23 | Change in employment rate (p.p.) 2021‑22 to 2022‑23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | +4.4% | 50.4% | 52.1% | +1.7 |

| Prince Edward Island | +4.4% | 60.0% | 60.4% | +0.4 |

| Nova Scotia | +4.0% | 57.1% | 57.9% | +0.8 |

| New Brunswick | +3.8% | 55.8% | 56.5% | +0.8 |

| Quebec | +2.7% | 60.8% | 61.8% | +1.0 |

| Ontario | +3.7% | 60.6% | 61.9% | +1.3 |

| Manitoba | +2.4% | 63.1% | 63.7% | +0.6 |

| Saskatchewan | +2.9% | 63.8% | 64.6% | +0.8 |

| Alberta | +4.8% | 64.4% | 65.9% | +1.5 |

| British Columbia | +2.7% | 61.5% | 62.1% | +0.7 |

| Yukon | +1.7% | 69.4% | 69.3% | -0.1 |

| Northwest Territories | +2.6% | 70.1% | 71.6% | +1.5 |

| Nunavut | +3.9% | 55.3% | 56.1% | +0.8 |

| Canada* | +3.4% | 61.0% | 62.2% | +1.1 |

- * Figures for Canada’s employment and employment rate exclude the territories. Percentage change is based on unrounded numbers.

- Sources: Statistics Canada; Labour Force Survey, Table 14‑10‑0287‑01 and 14‑10‑0292‑01, seasonally adjusted data.

Unemployment and unemployment rate

All provinces and territories noticed a significant decrease in unemployment in 2022‑23 compared to the previous fiscal period, except for Nunavut where an increase of 11.5% in the number of unemployed was registered (consult Table 4). Prince Edward Island (-29.2%), Ontario (-26.3%), Yukon (-25.6%), Alberta (‑24.9%) and Saskatchewan (‑24.2%) registered the largest drops.

Between 2021‑22 and 2022‑23, all but one provinces and territories experienced a reduction in their unemployment rate resulting from lower unemployment and a growing labour force. Nunavut had an increase in unemployment rate of 0.8 p.p., caused by higher unemployment. In 2022‑23, Quebec (4.2%), Manitoba, Saskatchewan and British Columbia (4.5%), as well as Yukon (4.1%) reported lower unemployment rates than the national level (5.1%) in 2022‑23 (consult Table 4).

| Province or territory | Change in unemployment 2021‑22 to 2022‑23 | Unemployment rate 2021‑22 | Unemployment rate 2022‑23 | Change in unemployment rate (p.p.) 2021‑22 to 2022‑23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | -18.2% | 13.0% | 10.5% | -2.5 |

| Prince Edward Island | -29.2% | 10.0% | 7.0% | -3.0 |

| Nova Scotia | -20.9% | 8.1% | 6.2% | -1.8 |

| New Brunswick | -20.2% | 8.8% | 6.9% | -1.9 |

| Quebec | -22.1% | 5.5% | 4.2% | -1.3 |

| Ontario | -26.3% | 7.4% | 5.4% | -2.0 |

| Manitoba | -20.8% | 5.7% | 4.5% | -1.2 |

| Saskatchewan | -24.2% | 6.0% | 4.5% | -1.5 |

| Alberta | -24.9% | 7.7% | 5.6% | -2.0 |

| British Columbia | -22.5% | 5.9% | 4.5% | -1.4 |

| Yukon | -25.6% | 5.5% | 4.1% | -1.4 |

| Northwest Territories | -0.6% | 5.6% | 5.5% | -0.2 |

| Nunavut | +11.5% | 11.9% | 12.7% | +0.8 |

| Canada* | -24.2% | 6.8% | 5.1% | -1.7 |

- * Figures for Canada’s unemployment and unemployment rate exclude the territories. Percentage change is based on unrounded numbers.

- Sources: Statistics Canada; Labour Force Survey, Table 14‑10‑0287‑01 and 14‑10‑0292‑01, seasonally adjusted data.

Duration of unemployment

In 2022‑23, only Prince Edward Island had an increase in its average duration of unemployment (+10.9%) compared to 2021‑22 for a third consecutive fiscal year (consult Table 5). All other provinces had a decrease in the average duration of unemployment. Alberta (-26.6%) and Ontario (-18.0%) were the only 2 provinces with a greater decrease in the average duration than the national average (-16.3%) between 2021‑22 and 2022‑23.

| Province | Average weeks of unemployment 2021‑22 | Average weeks of unemployment 2022‑23 | Difference in average weeks of unemployment 2021‑22 to 2022‑23 | Change (%) in average duration of unemployment 2021‑22 to 2022‑23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 21.6 | 18.8 | -2.8 | -13.1% |

| Prince Edward Island | 17.2 | 19.0 | +1.9 | +10.9% |

| Nova Scotia | 21.9 | 19.8 | -2.0 | -9.3% |

| New Brunswick | 19.0 | 16.9 | -2.1 | -11.1% |

| Quebec | 19.0 | 18.0 | -1.0 | -5.5% |

| Ontario | 23.0 | 18.8 | -4.1 | -18.0% |

| Manitoba | 20.5 | 18.2 | -2.3 | -11.2% |

| Saskatchewan | 23.1 | 20.3 | -2.8 | -12.3% |

| Alberta | 27.7 | 20.3 | -7.4 | -26.6% |

| British Columbia | 20.2 | 17.1 | -3.2 | -15.6% |

| Canada | 22.3 | 18.7 | -3.6 | -16.3% |

- * Excludes the territories. Percentage change is based on unrounded numbers.

- Sources: Statistics Canada; Labour Force Survey, Table 14‑10‑0342‑01.

Weekly hours and earnings

The average weekly hours actually worked in 2022‑23 decreased from the previous fiscal year in almost all provinces, except for Prince Edward Island (+0.2%) and Ontario (+0.2%). Manitoba (-2.4%), New Brunswick (-0.8%) and Alberta (-0.8%) registered the highest decrease between 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 (consult Table 6). However, Alberta still had the highest average weekly hours actually worked in 2022‑23, at 34.0 hours.

Average nominal weekly earnings increased in 2022‑23 in all provinces and territories compared to 2021‑22. However, the inflation also increased during the same period. Except for Nunavut, all provinces and territories had an increase in nominal weekly earnings lower than the increase in CPI, indicating a decrease in the average purchasing power of workers in 2022‑23. The change in average nominal weekly earnings was above the national average for most of the provinces, including all Atlantic provinces. Ontario and Alberta had an increase that was somewhat below the national average, and given their size, drove down the national average (consult Table 6).

| Province or territory | Average weekly hours worked* 2022‑23 | Change in average weekly hours worked (%) 2021‑22 to 2022‑23 | Average nominal weekly earnings** 2022‑23 | Change in average nominal weekly earnings (%) 2021‑22 to 2022‑23 | Change in consumer price index (%) 2021‑22 to 2022‑23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 33.7 | -0.7% | $1,160 | 4.6% | 6.3% |

| Prince Edward Island | 33.9 | +0.2% | $987 | 3.5% | 8.4% |

| Nova Scotia | 32.4 | -0.7% | $1,027 | 3.8% | 7.5% |

| New Brunswick | 33.6 | -0.8% | $1,076 | 5.5% | 7.1% |

| Quebec | 31.8 | -0.5% | $1,119 | 3.3% | 6.6% |

| Ontario | 32.9 | +0.2% | $1,200 | 2.4% | 6.5% |

| Manitoba | 32.7 | -2.4% | $1,069 | 4.0% | 7.8% |

| Saskatchewan | 33.8 | -0.7% | $1,147 | 2.8% | 6.8% |

| Alberta | 34.0 | -0.8% | $1,261 | 2.3% | 6.0% |

| British Columbia | 32.2 | -0.2% | $1,171 | 3.1% | 7.0% |

| Yukon | n.a. | n.a. | $1,339 | 2.2% | 7.3% |

| Northwest Territories | n.a. | n.a. | $1,570 | 1.5% | 7.0% |

| Nunavut | n.a. | n.a. | $1,582 | 4.8% | 3.9% |

| Canada*** | 32.7 | -0.3% | $1,171 | 2.9% | 6.6% |

- * Weekly hours worked reflect the number of hours actually worked in the reference week of the Labour Force Survey from all jobs, including overtime.

- ** Earnings data are based on gross payroll before source deductions; this includes earnings for overtime.

- *** Excludes the territories. Percentage change is based on unrounded numbers.

- Sources: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14‑10‑0042‑01, unadjusted for seasonally (for hours worked), Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours, Table 14‑10‑0203‑01, unadjusted for seasonality (for nominal weekly earnings) and Consumer Price Index Measures, Table 18‑10‑0004‑01, unadjusted for seasonality (for CPI).

Job vacancies and labour market tightness

When comparing the last quarter of 2022‑23 to the same quarter in 2021‑22, the number of vacancies decreased in all provinces except Saskatchewan (+14.6%), Manitoba (+2.3%), Nova Scotia (+2.1%) and all territories (consult Table 7). British Columbia (-17.2%), Ontario (-16.9%) and Quebec (-12.4%) registered the biggest decrease in the number of vacancies across all provinces. Apart from the territories, British Columbia and Quebec (5.8% and 5.6% respectively) were the only provinces with a job vacancy rate higher than the national average (5.2%) in 2022‑23.

The decrease in the number of vacancies in most provinces indicates a reduction of the labour market tightness. However, based on the annual UV ratio, the labour market still appeared tight in many provinces in 2022‑23. Nonetheless, the UV ratio was at a historical low in the beginning of 2022‑23 but increased in all provinces during the rest of the fiscal year, which denoted less tightness in the labour market (consult Chart 11).

| Province and territory | Change in number of job vacancies (%) Q4 of 2021‑22 to Q4 of 2022‑23 | Job vacancy rate (%) 2022‑23 | Unemployment-to-vacancy ratio 2022‑23 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | -9.3% | 3.6% | 3.7 |

| Prince Edward Island | -0.3% | 5.2% | 1.7 |

| Nova Scotia | +2.1% | 5.0% | 1.5 |

| New Brunswick | -7.6% | 4.5% | 1.9 |

| Quebec | -12.4% | 5.6% | 0.9 |

| Ontario | -16.9% | 5.0% | 1.3 |

| Manitoba | +2.3% | 4.6% | 1.1 |

| Saskatchewan | +14.6% | 4.9% | 1.1 |

| Alberta | -1.7% | 4.7% | 1.5 |

| British Columbia | -17.2% | 5.8% | 0.9 |

| Yukon | +2.1% | 7.4% | n.a. |

| Northwest Territories | +20.5% | 6.6% | n.a. |

| Nunavut | +54.2% | 3.4% | n.a. |

| Canada | -12.3% | 5.2% | 1.2 |

- Sources: Statistics Canada, Job Vacancy and Wage Survey, Table 14‑10‑0326‑01, unadjusted for seasonality (for job vacancies) and Labour Force Survey, Table 14‑10‑0287‑01, unadjusted for seasonality (for unemployment).

Text description for chart 11

| Region | Unemployment-to-vacancy ratio, first quarter of 2022-23 | Unemployment-to-vacancy ratio , last quarter of 2022-23 |

|---|---|---|

| Canada | 1.0 | 1.4 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 3.1 | 5.4 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1.4 | 2.6 |

| Nova Scotia | 1.4 | 1.7 |

| New Brunswick | 1.5 | 2.3 |

| Quebec | 0.7 | 1.1 |

| Ontario | 1.1 | 1.6 |

| Manitoba | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| Saskatchewan | 1.1 | 1.3 |

| Alberta | 1.3 | 1.9 |

| British Columbia | 0.8 | 1.1 |

- Sources: Statistics Canada, Job Vacancy and Wage Survey, Table 14‑10‑0326‑01, seasonally unadjusted (for job vacancies) and Labour Force Survey, Table 14‑10‑0287‑01 (for unemployment).

1.4 Summary

Following the strong recovery of the previous fiscal year, the Canadian economy experienced a slowdown in real GDP growth (+3.2%) in 2022‑23. The fiscal year was also marked by unprecedented levels of inflation, with a peak at 8.1% in June 2022. In response, the Bank of Canada increased its interest rate 7 times over the fiscal year, going from 0.75% to 4.75%. The impact of these rate hikes started to materialize with inflation lowering to 4.3% in March 2023.

The Canadian labour market, on the other hand, continued its strong recovery during the beginning of 2022‑23, notably with a historical low annual unemployment rate of 5.1%. Growth in employment also held its ground with an increase of 1.9% over the course of 2022‑23. Meanwhile, both job vacancies and job vacancy rates rose to record levels in Canada in 2022‑23, indicating a tighter labour market. This trend started to reverse approaching the end of the fiscal year with the UV ratio gradually increasing, indicating less concern about labour shortages in the Canadian labour market.

At the regional level, all provinces and territories experienced growth in employment in 2022‑23 compared to the previous fiscal year, with the greatest gains in Alberta (+4.8%), Prince Edward Island (+4.4%) and Newfoundland and Labrador (+4.4%). All provinces and territories, except Nunavut, experienced a decrease in their unemployment rates, resulting from lower unemployment and a growing labour force. British Columbia and Quebec had the tightest labour markets, while Alberta and the Atlantic provinces had less labour market tightness compared to the national average.

The impact of these recent labour market developments on the EI program is shown in the following sections in this report.