Technical Report - Incremental Impact of Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy and Skills Partnership Fund

By: Andy Handouyahia, Momath Wilane, Charles Bouwer

On this page

- Abstract

- Acknowledgement

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Program background

- 3. Methodology

- 4. Participants sociodemographic profile

- 5. Incremental Impacts Results

- 6. Cost benefit analysis

- 7. Conclusion

- 8. Reference

- Appendix A: Matching quality

- Appendix B: Detailed Socio-Demographic Characteristics Results

- Appendix C: Incremental Impacts Results

- Appendix D: Cost benefit results

-

List of abbreviations

- AHRDA

- Aboriginal Human Resources and Development Agreements

- APE

- Action Plan Equivalent

- ASETS

- Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy

- CRA

- Canada Revenue Agency

- CSGC

- Common System for Grants and Contributions

- EAS

- Employment Assistance Services

- EBs

- Employment Benefits

- EBSMs

- Employment Benefits and Support Measures

- EI

- Employment Insurance

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- JCP

- Job Creation Partnership

- ISET

- Indigenous Skills and Employment Training Program

- SD

- Skills Development

- SDA

- Skills Development Apprentice

- SDE

- Skills Development Essential Skills

- SE

- Self-Employment

- SPF

- Skills and Partnership Fund

- TWS

- Targeted Wage Subsidies

- WSE

- Work Student Experience

-

List of tables

- Table 1: Costs and benefits assigned to each perspective and their estimation methods

- Table A1: Mean Standardized Bias and Pseudo R² for active claimant

- Table A2: Mean Standardized Bias and Pseudo R² for former claimant

- Table A3: Mean Standardized Bias and Pseudo R² for non-EI claimant

- Table B1: Socio-Demographic Characteristic of Active EI Claimant Participants in ASETS

- Table B2: Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Former EI Claimant Participants in ASETS

- Table B3: Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Non EI Claimant Participants in ASETS

- Table C1: Incremental Impacts for Active claimant Participants in ASETS (n= 6,839)

- Table C2: Incremental Impacts for Former claimant Participants in ASETS (n= 9,463)

- Table C3: Incremental Impacts for Non-EI claimant Participants in ASETS (n= 33,061)

- Table C4: Incremental Impacts for active claimant in Skills Development Participants (n= 3,637) under ASETS

- Table C5: Incremental Impacts for former claimant in Skills Development Participants (n= 6,623) under ASETS

- Table C6: Incremental Impacts for non-EI claimant in Skills Development Participants (n= 20,855) under ASETS

- Table C7: Incremental Impacts for active claimant in Targeted Wage Subsidy Participants (n= 350) under ASETS

- Table C8: Incremental Impacts for former claimant in Targeted Wage Subsidy Participants (n= 1,105) under ASETS

- Table C9: Incremental Impacts for non-EI claimant in Targeted Wage Subsidy Participants (n= 1,471) under ASETS

- Table C10: Incremental Impacts for former claimant in Job Creation Partnership Participants (n= 802) under ASETS

- Table C11: Incremental Impacts for non-EI claimant in Job Creation Partnership Participants (n= 2,195) under ASETS

- Table C12: Incremental Impacts for active claimant in Employment Assistance Services participants (n= 2,657) under ASETS

- Table C13: Incremental Impacts for active claimant in Skills Development- Essential Skills Participants (n= 350) under ASETS

- Table C14: Incremental Impacts for former claimant in Skills Development- Essential Skills Participants (n= 1,087) under ASETS

- Table C15: Incremental Impacts for non-EI claimant in Skills Development- Essential Skills Participants (n= 4,662) under ASETS

- Table C16: Incremental Impacts for non-EI claimant in Work Student Experience Participants (n= 5,481) under ASETS

- Table C17: Incremental Impacts for active claimant participants (n= 635) in Skills and Partnership Fund

- Table C18: Incremental Impacts for former claimant in participants (n= 474) in Skills and Partnership Fund

- Table C19: Incremental Impacts for non-EI claimant in participants in Skills and Partnership Fund

- Table C20: Incremental Impacts for Active claimant Participants in ASETS (n=2,956) who were female

- Table C21: Incremental Impacts for Former claimant Participants in ASETS (n= 4,624) who were female

- Table C22: Incremental Impacts for Non-EI claimant Participants in ASETS (n= 17,158) who were female

- Table C23: Incremental Impacts for Active claimant Participants in ASETS (n= 4,360) who were male

- Table C24: Incremental Impacts for Former claimant Participants in ASETS (n=5,257) who were male

- Table C25: Incremental Impacts for Non-EI claimant Participants in ASETS (n= 17,454) who were male

- Table C26: Incremental Impacts for Active claimant Participants in ASETS (n= 3,453) who reside in rural area

- Table C27: Incremental Impacts for Former claimant Participants in ASETS (n=4,395) who reside in rural area

- Table C28: Incremental Impacts for Non-EI claimant Participants in ASETS (n= 20,927) who reside in rural area

- Table C29: Incremental Impacts for Active claimant Participants in ASETS (n= 3,392) who reside in urban area

- Table C30: Incremental Impacts for Former claimant Participants in ASETS (n= 4,326) who reside in urban area

- Table C31: Incremental Impacts for Non-EI claimant Participants in ASETS (n=14,299) who reside in urban area

Abstract

This technical report presents the methods used to estimate the incremental impacts for 2 labour market programs, the Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy (‘the strategy’) and the Skills and Partnership Fund (‘the fund’). It also presents the results from the cost-benefit analysis associated with the strategy. The study uses rich longitudinal administrative data from the Labour Market Program Data Platform covering all participants from 2011 to 2012. The study applies propensity score kernel matching combined with difference in differences methods to produce the incremental impact estimates over a 3-year, post-intervention period up to 2016. The evaluation results suggest that both the strategy and the fund increase Indigenous peoples’ participation in the Canadian labour market and improve their labour market attachment. The social benefits of participation exceed the cost of investments for most claimant typesFootnote 1 over time, yielding a positive social return on investment over the 12 years period.

Acknowledgement

This technical report on the incremental impact of Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy and Skills Partnership Fund Program was made possible by the contributions of numerous people in the Evaluation Directorate, Indigenous Affairs Directorate, and Program Operations. We are grateful for the insightful comments and the support we received from Laura MacFadgen and Jerome Mercier as well as our colleagues from Partnership Division. We would also like to thank our colleagues from the Skills Employment Branch and Program Operations Branch for the collaboration and assistance.

1. Introduction

The Government of Canada invests in specific programs to facilitate the participation of Indigenous peoples in the labour market. Over the past 2 decades, Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) has funded Indigenous organizations to provide labour market programming to Indigenous peoples. This technical report supports the quantitative analysis conducted as part of the 2020 EvaluationFootnote 2. Specifically, it presents the methodology used for selecting the comparison group, building the econometric model, and estimating the cost-benefit results of the programs in detail.

In 1999, the Aboriginal Human Resource Development Strategy (1999 to 2010) provided Indigenous organizations with funding to improve employment opportunities for Indigenous peoples and increase their participation in the labour market. ESDC has continued providing this support through the following labour market programs:

- the Aboriginal Human Resources Development Strategy

- the Aboriginal Skills Training and Employment Strategic Investment Fund (2009 to 2011)

- the Skills and Partnership Fund (‘the fund’, 2010 to present), and

- the Indigenous Skills and Employment Training Program (2019 to present), which replaced the Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy (‘the strategy,’ 2010 to 2018)

In 2015, ESDC’s Evaluation Directorate conducted a summative evaluation of the strategy and the fund. At that time, it was not possible to assess the net impacts of these programs on labour market attachment indicators adequately. This was due to the lack of EI and income tax data to inform post-program outcomes (such as, employment income, earnings, social assistance (SA) and Employment Insurance (EI) receipt) following participation in an intervention. Currently, the availability of additional income tax data from the CRA (up to 2016) allows for a sufficiently long post-program observation period, permitting for the assessment of long-term impacts of labour market indicators. The present study uses this data to conduct an incremental impact for both programs and a cost benefit analysis for the Strategy only. This analysis forms a key component of the 2020 Summative Evaluation of these programs as per the Financial Administration Act and Treasury Board Policy on Results requirements. The study examines the fund’s intervention and the following interventions under the strategy:

- Employment Assistance Services (EAS)

- Skills Development (SD)

- Targeted Wage Subsidies (TWS)

- Job Creation Partnership (JCP)

- Skills Development Essential Skills (SD-E), and

- Work Student Experience (WSE)

The study uses a rich longitudinal administrative dataset from the Labour Market Program Data Platform (LMPDP) to conduct the analysis. The LMPDP contains detailed information on all participants who started an intervention between January 2011 and December 2012. The study uses propensity score matching combined with the difference in differences methodsFootnote 3 to estimate the incremental impact of the program from the years 2010 to 2016. Furthermore, it estimates the net social benefits to analyze to what extent the Strategy is cost effective.

This report is organized as follows. Section 2 presents a brief overview of the program. Section 3 describes the statistical methodology used to analyse the effectiveness of the programs, and Section 4 presents the participants’ socio-demographic profile. The incremental impact and cost-benefit analysis results are presented in Section 5 and 6, respectively. Section 7 concludes the report.

2. Program background

The strategy and the fund share the same objective of increasing Indigenous peoples’ participation in the Canadian labour market. The objective of the fund is to contribute to the skills development of Indigenous peoples and their transition from training towards long-term employment. The fund differs from the strategy in terms of its delivery model. The fund is a demand driven and project-based contribution program that supports government priorities and partnerships by funding short-term projects (in other words, from 1 to 3 years) or emerging large-scale projects such as, but not limited to, natural resource extraction projects. These projects contribute to the skills development, training and employment of Indigenous peoples.

The objective of the strategy is to improve Indigenous peoples' participation in the Canadian workforce, ensuring that First Nations, Inuit and Métis have the skills and training for sustainable and meaningful employment. The program accomplishes this objective by promoting demand-driven skills development, fostering partnerships with the private sector and other levels of government, and building accountability for improved results.

The strategy provides funding through contribution agreements to Indigenous organizations (for example, incorporated for-profit and not-for-profit Indigenous controlled organizations, Tribal Councils, Indian Act Bands). It assists them in designing and delivering demand-driven labour market programs and associated supports such as childcare and special supports for Persons with Disabilities. Given that the strategy utilizes a partnership-based approach, agreement holders have the flexibility and authority to make decisions that will best meet the needs of their Indigenous clients.

The 2018 federal budget announced the creation of the Indigenous Skills and Employment Training Program (ISET) with an investment of $2 billion over 5 years and $408 million ongoing from 2019 to 2028. It replaces the strategy with the goal of helping Indigenous peoples advance their skills and find employment. As with past Indigenous labour market programming, there is a high degree of similarity between the programs in terms of the participant population, the service delivery organizations and the types of interventions provided.

3. Methodology

3.1 Data and unit of analysis

The study uses administrative panel data from the Labour Market Program Data Platform (LMPDP). The data contains information from multiple integrated sources such as program participation data, the EI data (EI part I data on EI claims and EI part II data on program participation) and the income tax data from the Canada Revenue Agency.

The analysis covers all participants who began participating in interventions provided under the fund and the strategy (for example, Skills Development, Job Creation Partnership, Targeted Wage Subsidies, Employment Assistance Services, Skills Development Essential Skills, and Work Student Experience) between January 2011 and December 2012. The analysis examines the incremental impact for active and former claimants, and non-EI claimants.

- Active claimants are participants who started an intervention while collecting Employment Insurance benefits

- Former claimants are those who started an intervention up to 3 years after the end of their EI benefit period

- Non-EI claimants are those who do not qualify as either active or former claimants based on their claims history

Given the data limitations and the methodological challenge to select appropriate comparison groups, the study does not include the Skills Development-Apprentice and Self-Employment (SE) intervention delivered under the strategy.

The study uses Action Plan Equivalents (APE) as the unit of analysis. An APE regroups all interventions taken by a participant within an interval of 6 months of each other. Since APE contain more than 1 intervention, for reporting purposes, the observed effect is assigned to the longest intervention included in an APE unless it is composed only of EAS. For the fund, there are an insufficient number of participants to conduct the analysis by Action Plan Equivalents (APE) type and therefore, the study produced the incremental impact by EI eligibility status only.

3.2 Estimating the incremental impact

Assessing the impact of any intervention requires making an inference about the outcomes that would have been observed for program participants had they not participated. In this context, evaluators have to define 2 potential outcomes: (1) outcome under receipt of intervention and (2) outcome under no intervention. The fundamental problem that arises in this situation is that it is only possible to observe one of the potential outcomes for each individualFootnote 4. The unobserved outcomes are called counterfactual outcomes, as they are the outcomes that would have occurred for participation group members if participation had been withheld. The next sections discuss the approaches for determining the counterfactual and implementing the propensity score matching combined with difference in differences.

3.2.1 Selection of comparison group

This study uses a non-experimental method to determine the counterfactual. Non-experimental methods generate comparison groups that are akin to the group of programme participants by using techniques, such as propensity score matching combined with difference in differences. This approach avoids the ethical and political challenges of an experimental design that would require creating a comparison group of units that are randomly, denied access to a programme.

This study examines 3 types of EI claimants (active, former, or non-EI) and creates three distinct comparison groups to determine the counterfactual for each group.

- For active claimants, incremental impacts are measured relative to a comparison group of Indigenous EI active claimants who were eligible to participate in the program, but did not

- For former and non-EI claimants, it was not possible to identify a comparison group of non-participants using the administrative data. In this context, comparison groups for former and non-EI claimant participants are created using Indigenous former and non-EI claimants who received low-intensity employment services interventions during the same reference period (in other words, Employment Assistance Services)

3.2.2 Implementation of the Matching Estimator combined with Difference in Differences

A major step before implementing the approach and estimating the program impact is to ensure that program participants and comparison groups are comparable over the same period of time (temporal alignment). Indeed, comparison candidates should be eligible to participate in the program at the same time as the program participants to whom they are being compared. To coordinate and control the timing of eligibility among comparison group candidates and actual participation among program clients, the observation period is divided into time selection intervals defined in terms of calendar quarters. Program participants are assigned to a selection interval according to the date they started their APEs. A sequence of separate comparison pools (which may share members) correspond to each selection interval (or annual quarter) into which the observation period has been divided. Members of each comparison group are individuals who were eligible to enter in the labour market program in a given selection interval, but did not. As a result, participants in each selection interval are accompanied by a comparison group of individuals eligible to enter the program at hypothetical APE start dates within the same selection interval.

In order to use propensity score matching combined with difference in differences methods, the study works with some identifying assumptions.

Conditional Independence Assumption: The conditional independence assumption requires that the common variables that affect participation assignment and intervention-specific outcomes be observable. The richness of the available administrative data allow for the inclusion of the most relevant variables influencing the decision to participate in the interventions and the labour market outcomes in the propensity-score model. In this context, this study assumes that the Conditional Independence Assumption is satisfied.

Overlap assumption: This assumption ensures that persons with the same covariate values have a positive probability of being both participants and non-participants (Heckman, LaLonde, and Smith, 1999). The validation tests shows a good overlap of the distribution of the propensity score between participants and comparison group members.

Conditional Bias Stability Assumption (BSA): The BSA assumes that the available conditioning variables do not suffice to solve the selection problem on their own, but do suffice once the fixed effect has been removed, as we do by differencing. The motivation for the BSA comes from the concern that some relatively stable unobserved characteristics, such as ability, motivation, and/or attractiveness, may persistently affect labour market outcomes, but not fully capture conditioning on the available pre-program labour market outcomes. To satisfy the BSA, this analysis includes the pre-participation variables in the propensity score model. However, it should be noted that 5 years of pre-participation data may not be available for some individuals who have recently entered or re-entered the labour force. These cases are also flagged in the current study and are taken into account in the propensity-score models.

Assuming that conditional independence, common support and the BSA hold, this study can use the propensity score matching (PSM) combined with the difference-in–differences methods to estimate the impact of the program.

3.2.2.1 Propensity score model

This study uses propensity score matching to predict the probability of participating in the program. The data used for the model cover a large number of characteristics reflecting the labour market experiences and socio-demographic characteristics of participants and comparison cases. These characteristics include age, gender, marital status, disability status, and distinct Indigenous group. For both groups, the data also have information on their economic region and province and qualifications (for example, occupational group, skill levels related to the last job before opening their EI claim, industry codes). The data also includes labour market history (for example, use of EI benefits and weeks, employment/self-employment earnings, use of social assistance, incidence of employment) in the 5 years preceding participation. To capture the regional labour market, geographical location or community where Indigenous participants reside, this study uses indicators from the Service Canada Centre for active claimant participants from the EI Part I databank, and the agreement holder number for former non-EI claimant participants.

3.2.2.2 Matching algorithm

This study uses the kernel matching algorithm to match participants and the comparison group with respect to their propensity scores. Kernel matching is a non-parametric technique that uses weighted averages of the outcomes of all individuals in the comparison group to construct the counterfactual. A major advantage of this approach is that it results in lower variance of the estimated effects.

3.2.2.3 Quality of the matching

To illustrate the quality of the matching, Table A1 in Appendix A presents the summary results of covariate balancing tests before and after matching in each program using standardized mean differences between participants and non-participants. The results suggest that the difference in the distribution of the covariates between the participation and comparison groups is reduced substantially after the matching. For example, for active claimants participating in Skills Development, the average cross-group standardized difference prior to matching was about 6.8 and 0.6 after matching. The reduction of differences in the covariate distributions between the participation and comparison groups is very substantial, lending confidence to the results of the subsequent incremental impact analysis. Further details on the full list of covariates used in the propensity score model, as well as the balancing scores, are available upon request.

After assessing the matching quality, the incremental impact estimates were produced using the propensity score matching combined with the difference in differences methods. A rigorous sensitivity analysis was also carried out by applying Nearest Neighbor and Inverse Probability Weighting matching estimators. The results revealed that the estimated effects were not sensitive to different matching algorithms.

The study's main strength is its reliance on the rich administrative data in the LMPDP, which allows for controlling numerous socioeconomic and labour market characteristics in the propensity score model. The techniques used to build the counterfactual successfully matched participants to similar non-participants for each intervention. In addition, rigorous statistical tests using other estimation methods to validate the results helped to ensure robustness.

A potential limitation of this study is the possibility that there might have been pre-existing differences between the participants and non-participants that were not measured during the matching process. For example, factors such as ability, health, and motivation to seek employment. Although these variables are not available in data, the pre-existing differences between participants and non-participants are well captured by the very informative data on their respective labour market history (EI usage pattern and earnings’ profile in the 5 years before participation) and skills level related to their last occupation. Furthermore, the sensitivity analysis revealed that omitting unobserved characteristics in the propensity score model did not influences the sign of the estimated impact. Another potential challenge of this study is controlling for communities where Indigenous peoples reside. As there is no indicator for living in an Indigenous community in the available data, this study use the Service Canada Centre and the agreement holder number as well as the second digit of participants and non -participants’ postal code to capture the geographical location and local labour market.

4. Participants sociodemographic profile

Funding provided through the strategy and the fund supported over 80,000 participants between January 2011 and December 2012. Most individuals (n=75,625 or approximatively 94%) participated in the strategy and approximately 6% of participants (or n=4,487) were associated with interventions delivered under the fund.

In the strategy, 69% of the participants included in this analysis were non-EI claimant participants, while 21% and 10% were former claimant participants and active claimant participants, respectively. Similarly, Non-EI claimants made up the majority of participants in the fund (63%). Fund participants were slightly more likely (14%) to be active claimants than were strategy participants.

Under both programs, more than half of the participants were 30 years old or younger. The majority of participants were men, representing 63% of participants under the fund and 54% under the strategy. Most participants had at least a secondary school diploma at the start of the intervention, but only a few had completed a post secondary degree.

The study includes 7,869 active claimant participants in the strategy from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2012, representing about 10% of all participants. The highest proportion of participants was in Skills Development (n=3,637) and the lowest was in Work Student Experience (54). The majority of the strategy's participants were men, representing 61% of participants. More than half of the participants were 30 years old or younger (57%) and resided in rural areas (53%). Close to half of the participants (47%) had a high school diploma and 27% completed some post-secondary education at the time of participation. See Table B1 in Appendix B for more details.

The study included 16,012 former claimant participants in the strategy. A majority of these participants were male (56%) and 30 years old or younger (58%), and just over half resided in rural areas (51%). Over half of former claimant participants (53%) had a high school diploma and 25% had completed some post-secondary education at the time of participation. Please see Table B2 in Appendix B for more information.

Non-EI claimants comprised the majority of participants in the strategy (69%). The majority were male (52%) and almost two-thirds of participants (65%) were 30 years old or younger. Participants were more likely to live in rural areas (52%). Almost two-thirds of participants (64%) had a high school diploma and 20% had completed some post-secondary education at the time of participation. Please see Table B3 in Appendix B for more information.

5. Incremental impacts results

This section discusses the results of the incremental impact analysis on labour market attachment (incidence of employment, earnings) and reliance on income support (receipt of EI benefits and social assistance). This study broke down the results by socio-demographic subgroups including rural and urban areaFootnote 5. Tables presenting net impact results for participants broken down by EI claimant status and interventionsFootnote 6 are in Appendix C.

5.1 Active EI claimants

In the 3 year period following the receipt of an intervention by active claimants, the strategy led to:

- a cumulative gain in earnings amounting over $10,920

- an average annual increase of 3.9 percentage points in their employmentFootnote 7; and

- a cumulative decrease of $180 in receipt of social assistance benefits

Looking at the results by intervention type, participants who took part in Skills Development, Targeted Wage Subsidies and Employment Assistance Services interventions raised their employment, increased their earnings, and decreased their use of social assistance benefits relative to non-participants. On the other hand, participants who took part in the Skills Development Essential Skills intervention experienced positive but small impacts, suggesting that this type of intervention, while necessary, may not be sufficient to foster a stronger attachment to the labour market. The findings suggest also that improvements in labour market attachment were observed across gender and urban/rural.

Similarly, for active EI claimants, the fund led to a cumulative increase in post-participation earnings ($5,000 over 3 years), an average annual increase in their employment (0.3 percentage point), and a cumulative decrease in their use of social assistance ($220 over 3 years).

5.2 Former EI claimants

In the 3-year period following the receipt of an intervention by former claimants, the strategy led to:

- a cumulative gain in earnings amounting over $4,000

- an average annual increase of 2.7 percentage points in their employment; and

- a cumulative decrease of $830 in receipt of social assistance benefits

Looking at the results by intervention type, participants who took part in the Skills Development, Targeted Wage Subsidies, and Skills Development Essential Skills interventions increased their earnings and employment. At the same time, they decreased their use of social assistance benefits. Among former EI claimants, the findings show larger positive incremental impacts for women and urban participants relative to those found for men and rural participants, respectively.

Similarly, for former EI claimants, the fund led to a cumulative increase in post-participation earnings ($6,010 over 3 years), an average annual increase in their employment (5.3 percentage points), and a cumulative decrease in their use of social assistance ($480 over 3 years).

5.3 Non-EI claimant

Similarly, non-EI claimants experienced increases in their earnings and employment in the 3 years after participation, albeit with smaller impacts relative to the other claimant types. Following the same trend, they also decreased their use of social assistance. The Skills Development intervention led to the largest improvements in labour market attachment for this group of participants. In contrast, participants in the Essential Skills and Targeted Wage Subsidies had smaller improvements in their labour market attachment. The findings for non-EI claimants who took part in the Job Creation Partnership and the Work Student Experience interventions showed mixed results. For Job Creation Partnership, the mix of positive and negative results reflect, in part, the short-term nature of these interventions. Further, this intervention generally targets individuals with multiple barriers and relatively weaker labour market attachments. Regarding Work Student Experience, these results are expected since students participate in the intervention during their school breaks and return to school afterwards.

In the 3-year period following the receipt of an intervention by non-EI claimants, the fund led to:

- a cumulative increase in post-participation earnings ($1,240)

- an average annual increase in their employment (1.1 percentage points), and

- a cumulative decrease in their use of social assistance ($210 over 3 years)

Overall, the evaluation results show that the strategy and the fund improve the labour market outcomes of participating Indigenous peoples. However, the magnitude of the impacts varies according to their EI claimant type and associated attachment to the labour market as well as depending on the intervention received. Following an intervention, program participants experience an increase in employment earnings, incidence of employment, and a decrease in reliance on social assistance compared to non-participants.

6. Cost benefit analysis

The incremental impact analysis assesses program effectiveness using yearly impact estimates during and up to 3 years after an intervention delivered under the strategy or the fund (from 2011 to 2012 up to 2016). As a result, this type of analysis cannot inform the longer-term impacts of these interventions on participants. To better address this issue and conduct a more robust cost-benefit analysis, the study assesses the effectiveness and efficiency of the program by using an older cohort from the ASETS program's predecessor, the Aboriginal Human Resources and Development Agreements (AHRDA). In particular, this analysis considers participants who completed their AHRDA intervention between January 2003 and December 2005, allowing a 10-year post-program observation window for their labour market outcomes.

The main objective of this analysis is to assess the cost effectiveness of the program. Specially, it aims to address the following questions:

- did the program result in net financial benefits or losses 10 years after the participation end?

- when does investment in the program “break even” (where the benefits equal the costs) from government and societal perspectives?

- what is the rate of return on investment of an intervention over 10 years post?

This analysis examines the cost effectiveness of the program from 3 perspectives:

- Individual: Account for the costs incurred by participants when taking part in the intervention (foregone earnings) and the benefits accrued following the intervention (higher-earnings profile relative to non-participants)

- Government: Account for the direct costs of the intervention as well as the costs associated with tax distortion; and benefits associated with participants’ higher earnings profile in the form of additional tax revenues and lower spending on income support programs

- Society: combination of individual and the government perspectives

The cost-benefit analysis is based on quantifiable costs and benefits. Starting with the benefits side, the analysis includes both earnings and fringe benefitsFootnote 8. It also includes the income tax paid, the EI and SA use, the EI Premium and the Canada Pension Plan (CPP)/Québec Pension Plan (QPP) contribution. With the exception of the fringe benefits, all theses benefitsFootnote 9 are estimated using the propensity score matching combined with difference in differences methods.

On the cost side, this analysis takes into account the direct costs of the interventions, along with the marginal social cost of public funds (MSCPF; see for example. Browning, 1987). More specifically, this means that the direct resource costs should be multiplied by a factor greater than one, in order to capture the distortions arising from financing the program by raising tax revenue. Following the advice received from expert peer reviewers, the MSCPF represents 20% of the program cost and subsequent impacts on sales taxes, income taxes as well as on EI and social assistance outlays.

An important aspect of the cost-benefit analysis is to determine who bears a particular cost or benefit. What can be a benefit from one perspective could be a cost from another perspective. For example, a decrease in EI use is viewed as reduction in income for the participants but as a benefit for the government. The costs and benefits assigned to each perspective are identified in the table below.

| Costs and benefits | Factors Included | Individual perspective | Government perspective | Society perspective | Estimation Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | Program cost | 0 | - | - | Cost estimates based on program expenditure data |

| Cost | Foregone earnings | - | 0 | - | In-program incremental impacts on earnings |

| Cost | Marginal Social Cost of Public Funds | 0 | - | - | 20% of program costs minus sales taxes minus income taxes minus EI minus SA |

| Benefit | Employment earnings | + | 0 | + | Incremental impacts |

| Benefit | Fringe benefits | + | 0 | + | Estimates are measured by 15.09 % of employment earnings |

| Benefit | Federal and provincial income taxes | - | + | 0 | Estimates based on earnings and federal and provincial income tax rate |

| Benefit | Federal and provincial sale taxes | - | + | 0 | Incremental impacts on earnings multiplied by the propensity to consume (97%), the proportion of household spending on taxable goods and service (52%) and by the total average federal and provincial sales tax rate (11%) |

| Benefit | Employment Insurance | -/+ | +/- | 0 | Incremental impacts |

| Benefit | Social Assistance | -/+ | +/- | 0 | Incremental impacts |

| Benefit | Canada Pension Plan and Quebec Pension Plan contributions | -/+ | +/- | 0 | Incremental impacts |

| Benefit | EI premiums | -/+ | +/- | 0 | Incremental impacts |

The society perspective combines both individual and government perspectives. For a given factor, a net gain to society occurs only when a gain to one group was not at the expense of another group. For example, increases in earnings represent a benefit for participants but neither a benefit nor a cost to the government. Thus, the net result is a gain for society. A cost to society occurs when a factor is a cost from one perspective and not a gain from the other perspective. For example, program costs represent a cost to the government, but not to participants; thus, they are considered a cost to society. Factors that constitute a net gain from one perspective but a net loss from the other perspective, equal to 0 from the society perspective. For example, a reduction in EI benefits may represent a cost to participants and a benefit to the government and neither cost nor benefit for the society.

The benefits and costs are calculated over a 10 year period after participation in the program (for a total of up to 12 years including the time spent in the program) and are subject to an annual discount rate of 5%.

The cost-benefit analysis accounted for all quantifiable costs and benefits directly attributable to the program that could be estimated using the available data. For instance, positive outcomes extend beyond higher earnings, including improved health outcomes. These additional benefits are not included in the cost-benefit analysis and are likely to lower government expenditures in the health care, thus increasing the social rate of return (for example Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2015; Saunders et al. 2017). Therefore, expanding the cost benefit framework to include potential savings resulting from improved health outcomes (for example, reduced health system expenditures) could yield additional positive impacts for both individuals and the government beyond what is directly measured.

The findings suggest that the AHRDA, the strategy's predecessor, yielded a positive social return on investment over 12 years (2 years in-program and 10 years post-participation) from the societal perspective (both government and participants). In particular, interventions' benefits outweigh their costs in less than 9 years and less than 5 years for participants with stronger attachment to the labour market.

Caution should be exercised in comparing cost-benefit analysis results across different EI claimant categories. In particular, for each EI claimant category, a unique comparison group was built to reflect the set of observable characteristics of their respective participants at the time. In addition, results reflect the mix of interventions received and examined under each EI claimant category.

6.1 Active EI Claimants

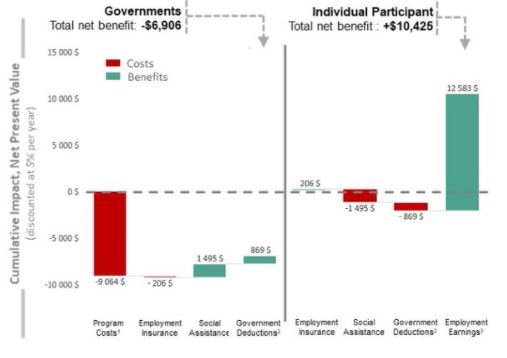

As shown in the Figure 1, Appendix D, from the societal perspective, the benefits for active claimants of participating in the program exceeded the costs by $3,519 over 12 years (2 years in program and 10 years post participation). It took 4.5 years for the benefits to recover the costs. Evidence finds that the social rate of return is 45%, indicating that for every dollar spent in the program for an active claimant participant, society received a return of $0.45.

Active claimant participants experienced an average net financial gain of $10,425 in 10 years after the end of participation. The majority of this gain came from increased employment earnings ($12,583), and EI benefit use ($206). However, from the government perspective, the benefits collected from delivering the program to active claimants were $6,906 than the cost.

6.2 Former EI claimants

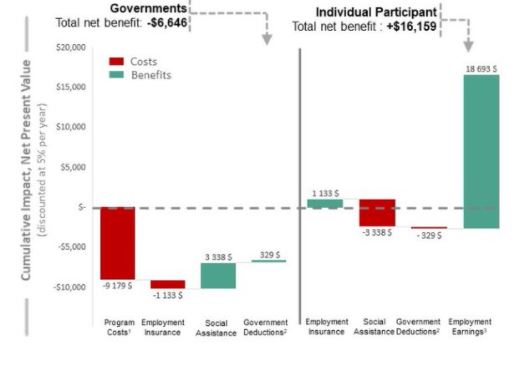

As shown in the Figure 2, Appendix D, from society’s perspective, for former EI claimant, the benefits from participating in the program exceeded the costs by $9,513, yielding a social rate of return of 119% over 12 years. It took 4.8 years for the benefits to recover the program costs.

Within 10 years after the end of participation, the benefits experienced by individuals exceeded the cost of participation by $16,159. However, from the government perspective, the benefits collected from delivering the program to former claimants were $6,646 lower than the costs.

6.3 Non-EI claimants

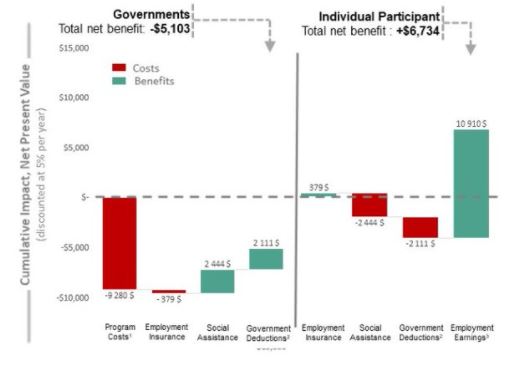

As shown in the Figure 3, Appendix D, for non-EI claimant participants in the program, the net social benefits are $1,631, yielding a social return on investment of 20% over 12 years. The interventions break even in 8.8 years after participation.

Non-EI claimant participants experienced an average net financial gain of $6,734 in 10 years after the end of participation. On the other hand, the total net cost from the government’s perspective is $5,103.

7. Conclusion

This study estimated the medium-term impacts for participants in both the strategy and the fund who started an intervention during January 2011 to December 2012. It presents also the cost-benefit analysis associated with the strategy. It uses non-parametric propensity score matching on a rich longitudinal administrative dataset, which contains comprehensive information on socio-demographic and labour market history on all participants and their matched non-participants.

The results suggest that both the strategy and the fund are effective at improving labour market attachment of participating Indigenous peoples. Skills Development is the most effective intervention for improving participants’ labour market attachment, regardless of their EI claimant status. Employment Assistance Services and Targeted Wage Subsidy initiatives also showed positive results, particularly for participants with relatively stronger pre-program labour market attachment.

The results from the cost-benefit analysis suggest that the AHRDA, the ASETS’ predecessor, yielded a positive social return on investment over the 12- period. In particular, from a societal perspective, benefits of interventions outweigh their associated costs in less than 9 years; and, in less than 5 years for participants with stronger attachment to the labour market.

8. References

Ashenfelter, O., & Card, D. (1985). Using the longitudinal structure of earnings to estimate the effect of training programs. Review of Economics and Statistics, 67(4), 648-660.

Bjerk, D. (2004). Youth criminal participation and household economic status. Department of Economics Working Paper. Hamilton, ON: McMaster University.

Butler-Jones, D. (2008). The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada, 2008. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada.

Caliendo, M., & Kopeinig, S. (2008). Some Practical Guidance for the Implementation of Propensity Score Matching. Journal of Economic Surveys, 22(1), 31-72.

Calmfors, L., & Lang, H. (1993). Macroeconomic effects of active labour market programmes- the basic theory. Stockholm, Sweden: Institute for International Economic Studies

Dahlberg, M., &Forslund, A. (2005). Direct displacement effects of labour market programs. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 107, 475-94.

DiNardo, J., and J. Tobias (2001): “Nonparametric Density and Regression Estimation,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(4), 11–28.

Duncan, G. (2005). Income and child well-being. Geary Lecture at the Economic and Social Research Institute. Dublin, Ireland.

Grün, C., Hauser, W., & Rhein, T. (2010). Is any job better than no job? Life satisfaction and reemployment. Journal of Labor Research, 31(3), 285-306.

Heckman, J. J., & Smith, J.A. (1999).The Pre-Programme Earnings Dip and the Determinants of Participation in a Social Program. Implications for Simple Programme Evaluation Strategies. The Economic Journal, 109(457), 313-348.

Höfler, M. (2005). Causal inference based on counterfactuals. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 5: 28.

Jackson, P. R., &Warr, P. B. (1984). Unemployment and psychological ill-health: The moderating role of duration and age. Psychological Medicine, 14(3), 605-614.

Lechner, M. (2010). The Estimation of Causal Effects by Difference-in-Difference Methods. Foundations and Trends in Econometrics, 4(3), 165-224.

Leung, A. (2004). The Cost of Pain and Suffering from Crime in Canada. Research and Statistics Division, Department of Justice Canada.

McKee-Ryan, F., Song, Z., Wanberg, C. R., &Kinicki, A. J. (2005). Psychological and physical well-being during unemployment: a meta-analytic study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 53.

Mendolia, S. (2014). The impact of husbands’ job loss on partners’ mental health. Review of Economics of the Household. 12(2): 277-94.

Ministère et de la Solidarité Sociale Québec (2006). Étude sur le rendement de l’investissement relié à la participation aux mesures actives offertes aux individus par Emploi-Québec. Rapport d’évaluation.

Nilsson A. and Agell J. (2003) “Crime, unemployment and labor market programs in turbulent times,” Institute for Labour Market Policy Evaluation, Working Paper 2003:14

Oreopolos, P., Page, M., & Stevens, A. (2005). The intergenerational effect of worker displacement. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, no. 1587.

Pagan, A., and A. Ullah (1999): Nonparametric Econometrics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Price, R. (1992). Psychological impact of job loss on individuals and families. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1(1): 9-10.

Rosenbaum, P., & Rubin, D. (1985): Constructing a Control Group Using Multivariate Matched Sampling Methods that Incorporate the Propensity Score," The American Statistician, 39, 33-38.

Saunders M, Barr B, McHale P, Hamelmann C. Key policies for addressing the social determinants of health and health inequities. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2017 (Health Evidence Network (HEN) synthesis report 52).

Silverman, B. (1986): Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis. Chapman & Hall, London.

Social Research and Demonstration Corporation (2002). Making Work Pay Final Report on the Self-Sufficiency Project for Long-Term Welfare Recipients.

Statistic Canada (2017) Aboriginal people and the labour market.

Appendix A: Matching quality

| APE Type | Participants- Before | Participants - After | Comparison cases - Before | Comparison cases - After | Pseudo R² - Before | Pseudo R² - After | Mean Bias - Before | Mean Bias - After | Out of Common Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | 3,637 | 3,632 | 43,961 | 43,961 | 0.200 | 0.0 | 6.8 | 0.6 | 5 |

| TWS | 350 | 335 | 43,668 | 43,668 | 0.385 | 0.120 | 11.0 | 4.3 | 16 |

| EAS-Only | 2,657 | 2,651 | 43,650 | 43,650 | 0.172 | 0.005 | 5.2 | 0.6 | 6 |

| SDE | 319 | 319 | 46,635 | 46,635 | 0.275 | 0.088 | 8.4 | 3.3 | 0 |

| SPF | 635 | 629 | 44,743 | 44,743 | 0.467 | 0.103 | 11.2 | 5.3 | 6 |

| APE Type | Participants- Before | Participants - After | Comparison cases - Before | Comparison cases - After | Pseudo R² - Before | Pseudo R² - After | Mean Bias - Before | Mean Bias - After | Out of Common Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | 6,623 | 6,601 | 22,059 | 22,059 | 0.108 | 0.002 | 3.8 | 0.4 | 22 |

| TWS | 1,105 | 1,014 | 21,990 | 21,990 | 0.424 | 0.049 | 11.8 | 2.2 | 91 |

| JCP | 802 | 785 | 22,343 | 22,343 | 0.484 | 0.066 | 14.4 | 3.0 | 17 |

| SDE | 1,087 | 1,083 | 22,059 | 22,059 | 0.191 | 0.019 | 5.8 | 1.4 | 4 |

| SPF | 474 | 468 | 22,156 | 22,156 | 0.401 | 0.043 | 12.2 | 2.9 | 6 |

| APE Type | Participants- Before | Participants - After | Comparison cases - Before | Comparison cases - After | Pseudo R² - Before | Pseudo R² - After | Mean Bias - Before | Mean Bias - After | Out of Common Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | 20,865 | 20,710 | 59,020 | 59,020 | 0.301 | 0.007 | 8.7 | 1.3 | 155 |

| TWS | 1,471 | 1,435 | 58,664 | 58,664 | 0.376 | 0.02 | 11.6 | 2.1 | 36 |

| JCP | 2,195 | 2,093 | 58,895 | 58,895 | 0.610 | 0.182 | 17.4 | 5.5 | 92 |

| SDE | 4,662 | 4,476 | 58,730 | 58,730 | 0.373 | 0.036 | 10.1 | 2.7 | 43 |

| WSE | 5,481 | 5,258 | 59,252 | 59,252 | 0.677 | 0.058 | 16.7 | 1.6 | 223 |

| SPF | 1,586 | 1,585 | 33,911 | 33,911 | 0.653 | 0.047 | 10.6 | 3.6 | 1 |

Appendix B: Detailed socio-demographic characteristics results

| Socio-Demographic Characteristic | SD | TWS | SE | JCP | EAS-Only | SDA | SDE | WSE | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | 3,637 | 350 | 68 | 287 | 2,657 | 485 | 331 | 54 | 7,869 |

| Gender: Male | 59% | 63% | 44% | 69% | 59% | 90% | 63% | 43% | 61% |

| Gender: Female | 41% | 37% | 56% | 31% | 41% | 10% | 37% | 57% | 39% |

| Age: Less than 30 years | 38% | 28% | 18% | 33% | 27% | 61% | 27% | 72% | 35% |

| Age: 31 to 54 years | 56% | 66% | 65% | 60% | 62% | 38% | 63% | 28% | 57% |

| Age: Over 55 years | 6% | 6% | 18% | 7% | 11% | 1% | 10% | 0% | 8% |

| Area of Residence: Urban | 47% | 34% | 62% | 29% | 51% | 62% | 31% | 46% | 47% |

| Area of Residence: Rural | 53% | 66% | 38% | 71% | 49% | 38% | 69% | 54% | 53% |

| Education: No Formal Education | 3% | 15% | 7% | 4% | 2% | 0% | 2% | 9% | 3% |

| Education: Grade 1 to 12 | 50% | 41% | 38% | 57% | 50% | 0% | 62% | 33% | 47% |

| Education: Industrial Training | 14% | 9% | 15% | 6 % | 12% | 0% | 10% | 15% | 12% |

| Education: Some Post-Secondary | 28% | 29% | 25% | 30% | 30% | 0% | 22% | 37% | 27% |

| Education: Bachelor’s Degree | 2% | 3% | 4% | 1% | 2% | 0% | 1% | 2% | 2% |

| Education: Master’s Degree | 0% | 0% | 3% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Education: Doctorate Degree | 0% | 0% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Education: Missing | 3% | 15% | 7% | 4% | 2% | 0% | 2% | 9% | 3% |

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics | SD | TWS | SE | JCP | EAS-Only | SDA | SDE | WSE | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | 6,623 | 1,105 | 127 | 802 | 5,485 | 519 | 1,087 | 264 | 16,012 |

| Gender: Male | 52% | 59% | 44% | 62% | 58% | 82% | 54% | 37% | 56% |

| Gender: Female | 48% | 41% | 56% | 38% | 42% | 18% | 46% | 63% | 44% |

| Age: Less than 30 years | 38% | 30% | 16% | 31% | 31% | 49% | 32% | 63% | 35% |

| Age: 31 to 54 years | 56% | 60% | 74% | 62% | 62% | 50% | 60% | 36% | 58% |

| Age: Over 55 years | 6% | 9% | 10% | 7% | 7% | 1% | 8% | 1% | 7% |

| Area of Residence: Urban | 50% | 32% | 55% | 28% | 58% | 62% | 30% | 48% | 49% |

| Area of Residence: Rural | 50% | 68% | 45% | 72% | 42% | 38% | 70% | 52% | 51% |

| Education: No Self-Reported Formal Education | 2% | 14% | 1% | 9% | 2% | 0% | 2% | 4% | 3% |

| Education: Grade 1 to 12 | 55% | 49% | 32% | 56% | 54% | 0% | 65% | 34% | 53% |

| Education: Industrial Training | 13% | 10% | 18% | 7% | 12% | 0% | 9% | 28% | 12% |

| Education: Some Post-Secondary School | 26% | 24% | 41% | 25% | 27% | 0% | 20% | 30% | 25% |

| Education: Bachelor’s Degree | 2% | 2% | 3% | 1% | 2% | 0% | 2% | 2% | 2% |

| Education: Master’s Degree | 0% | 0% | 3% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Education: Doctorate Degree | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics | SD | TWS | SE | JCP | EAS-Only | SDA | SDE | WSE | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | 20,865 | 1,471 | 254 | 2,195 | 15,591 | 1,225 | 4,662 | 5,481 | 51,744 |

| Gender: Male | 50% | 55% | 52% | 56% | 55% | 77% | 52% | 48% | 52% |

| Gender: Female | 50% | 45% | 48% | 44% | 45% | 23% | 47% | 51% | 47% |

| Age: Less than 30 years | 65% | 59% | 30% | 68% | 59% | 70% | 57% | 94% | 65% |

| Age: 31 to 54 years | 31% | 35% | 53% | 27% | 36% | 28% | 37% | 2% | 30% |

| Age: Over 55 years | 4% | 6% | 17% | 5% | 5% | 2% | 6% | 4% | 4% |

| Area of Residence: Urban | 51% | 37% | 64% | 19% | 61% | 68% | 28% | 23% | 48% |

| Area of Residence: Rural | 49% | 63% | 36% | 81% | 39% | 32% | 72% | 77% | 52% |

| Education: No Self-Reported Formal Education | 2% | 7% | 4% | 3% | 2% | 0% | 2% | 3% | 2% |

| Education: Grade 1 to 12 | 63% | 49% | 45% | 72% | 65% | 0% | 75% | 74% | 64% |

| Education: Industrial Training | 9% | 11% | 17% | 4% | 8% | 0% | 4% | 8% | 8% |

| Education: Some Post-Secondary School | 22% | 28% | 27% | 20% | 22% | 0% | 17% | 14% | 20% |

| Education: Bachelor’s Degree | 2% | 3% | 4% | 1% | 1% | 0% | 1% | 1% | 1% |

| Education: Master’s Degree | 0% | 0% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Education: Doctorate Degree | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

Appendix C: Incremental impacts results

Incremental Impacts for Active claimant Participants (n= 6,839)

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -1,984*** | 1,503*** | 3,379*** | 3,631*** | 4,014*** | 10,922*** | 10,031*** |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | -1.1*** | 2.2*** | 2.8*** | 3.1*** | 5.9*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 219*** | -413*** | -31 | 104 | 177*** | 250 | 56 |

| SA benefits ($) | -18 | -22 | -6*** | -82*** | -32 | -182*** | -222*** |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | 4.2*** | -2.3*** | -0.7 | -0.7 | -0.4 | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | 253 | -36 | 1,295*** | 1,053*** | 1,654*** | 4,002*** | 4,219*** |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | 1.4*** | 2.1*** | 2.2*** | 2.0*** | 3.8*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 87 | 163*** | 55 | 66 | 64 | 186 | 436*** |

| SA benefits ($) | -422*** | -385*** | -293*** | -236*** | -300*** | -829*** | -1,636*** |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -2.7*** | -1.8*** | -2.3*** | -1.1* | -2.8*** | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -233 | -246 | 590*** | 511* | 1,299*** | 2,400*** | 1,921** |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | -2.6*** | -0.2 | 2.1*** | 1.6*** | 2.5*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 3 | -17 | -45 | 18 | 59* | 33 | 19 |

| SA benefits ($) | -61 | -103* | -130** | -97 | -166*** | -393** | -557** |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -1.7*** | -1.4** | -1.5*** | -1.0 | -1.8*** | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -2,450*** | 1,350*** | 4,346*** | 5,151*** | 5,435*** | 14,931*** | 13,832*** |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | -1.8*** | 2.8*** | 4.3*** | 4.3*** | 6.0*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 312*** | -372*** | -69 | 140 | 290*** | 360 | 301 |

| SA benefits ($) | -25 | -92*** | -144*** | -164*** | -55*** | -363*** | -481*** |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | 3.7 | -3.1*** | -2.8*** | -1.6*** | -1.2* | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -571*** | -443 | 1,488*** | 1,649*** | 2,334*** | 5,472*** | 4,458*** |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | -1.5*** | 1.3** | 2.2*** | 2.8*** | 4.1*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | -24 | -111* | -41 | -32 | 91 | 18 | -117 |

| SA benefits ($) | -377*** | -367*** | -298 | -220 | -281 | -799 | -1,542 |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -2.0*** | -3.6*** | -3.3*** | -2.3*** | -2.5*** | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -760*** | 74 | 1,758*** | 1,994*** | 2,517*** | 6,269*** | 5,583*** |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | -5.5*** | -0.8 | 1.6* | 1.3* | 2.5*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 6 | -59** | -36 | 52 | 153*** | 170** | 116 |

| SA benefits ($) | -2 | -111 | -134* | -89 | -125 | -348 | -461 |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -0.9 | -2.2*** | -2.1*** | -1.7 | -1.3 | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -601 | 2,546*** | 2,099* | 1,685 | 2,776*** | 6,560** | 8,504** |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | 4.4** | 10.8*** | 4.3*** | 4.2 | 10.6*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 28 | 298 | 883*** | 94 | 216 | 1,193 | 1,518 |

| SA benefits ($) | -213*** | -517*** | -321** | -305* | -553*** | -1,178*** | -1,909*** |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -6.1*** | -3.6 | 4.2* | -1.2 | -4.5* | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | 1,102* | 1,018 | 1,152 | 915 | 2,335** | 4,402* | 6,522* |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | 11.2*** | 7.5*** | 5.3*** | 3.6* | 8.3*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 523*** | 1,087*** | 253*** | 313 | 122 | 687 | 2,298*** |

| SA benefits ($) | -435*** | -401*** | -368*** | -472*** | -457*** | -1,297*** | -2,133*** |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -2.4 | 2.6 | -0.7 | 0.6 | -3.5* | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | 2,756*** | 2,075*** | 316 | 267 | 625 | 1,209 | 6,040*** |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | 14.42*** | 8.61*** | 4.8*** | 1.5 | 3.5** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | -2 | 649*** | 549*** | 264*** | 308*** | 1,121*** | 1,767*** |

| SA benefits ($) | -387*** | -328*** | -289** | -245* | -262* | -796*** | -1,511*** |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -6.1*** | -0.2 | 1.7 | -0.4 | -1.2 | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | 519 | -851 | -790 | -1,298 | 75 | -2,013 | -2,344 |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | 9.0*** | 4.5** | 1.0 | 0.2 | 5.0** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 244 | 525*** | 256 | 618*** | 51 | 925* | 1,694*** |

| SA benefits ($) | -379*** | -368** | -198 | -186 | -113 | -496 | -1,243* |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -1.6 | 3.9* | 1.1 | 3.2 | -0.1 | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | 1,576 | 347 | -1,519 | -2,243 | -171 | -3,933 | -2,010 |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | 13.5** | 10.0 | 4.3 | 2.8 | 5.5 | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 49 | 537 | 219 | -214 | 11 | 16 | 602 |

| SA benefits ($) | -751** | -245 | 3 | -144 | -238 | -380 | -1,375 |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -10.1* | 6.7 | 6.2 | 2.2 | -4.1 | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -1,872*** | 1,546*** | 1,935*** | 1,757*** | 2,104*** | 7,342*** | 5,471*** |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | 0.5 | 3.1*** | 2.9*** | 3.8*** | 4.7*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 169 | -487*** | -48 | -90 | 38 | -587* | -418 |

| SA benefits ($) | -33 | 6 | -51 | -97* | -97 | -239 | -273 |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | 2.9*** | -3.4*** | -0.7 | -1.9*** | -1.8*** | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -1,858** | 687 | 939 | 44 | -234 | 749 | -422 |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 0.4 | 0.3 | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | -6 | -443 | -338 | 516 | 328 | 506 | 57 |

| SA benefits ($) | 71 | 214 | 118 | 134 | 273 | 526 | 810 |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | 3.4* | 1.1 | 2.5 | 6.8*** | 5.7*** | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | 2,842*** | 2,998*** | 2,174*** | 1,668*** | 1,485* | 5,326*** | 11,166*** |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | 4.4*** | 2.8* | 2.3 | 1.0 | 1.4 | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | -67 | 58 | 126 | 45 | -172 | -1 | -10 |

| SA benefits ($) | -643*** | -383*** | -94 | -153 | -256*** | -503*** | -1,529 |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -6.8*** | -2.5* | 0.2 | -0.5 | -3.6*** | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | 2,219*** | 1,342*** | 840 | -544 | 165 | 461 | 4,022** |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | -0.4 | -1.5 | 1.3 | -0.6 | -0.9 | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | -80 | 28 | 8 | 14 | -74 | -52 | -105 |

| SA benefits ($) | -152 | -76 | -55 | 62 | -49 | -43 | -271 |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -3.9** | -0.3 | 0.8 | 1.1 | -0.2 | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -355 | -1,538*** | -830 | -842 | 1,042* | -2,168 | -2,523 |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | 11.6*** | 4.0* | 9.4*** | 10.3*** | 15.4*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 5 | -88 | -171*** | -115 | -158* | -532*** | -527*** |

| SA benefits ($) | -180 | -170 | -176 | -134 | -203 | -683 | -863 |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -3.6** | -3.1* | -1.8 | -1.1 | -1.5 | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -4,326*** | -917 | 490 | 1,282 | 3,225*** | 4,996* | -247 |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | -5.1*** | -3.0 | 0.2 | -0.9 | 1.6 | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 958** | -881** | -810** | 144 | 741* | 75 | 153 |

| SA benefits ($) | 132* | 122 | -24 | -54 | -143 | -221 | 34 |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | 10.0*** | -3.3 | -1.4 | 1.2 | 0.0 | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -1,865*** | -729 | 1,560* | 1,640* | 2,806*** | 6,005*** | 3,411 |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | -2.5 | 2.5 | 4.2*** | 5.7*** | 5.9*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 321 | -96 | -92 | 274 | -22 | 160 | 384 |

| SA benefits ($) | 2 | -94 | -185 | -65 | -230 | -480 | -573 |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | 5.2*** | -2.7 | -1.8 | 2.1 | -1.5 | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -1,603*** | -164 | 253 | 493 | 497 | 1,243 | -523 |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | -1.9 | 3.0 | 1.6 | -0.9 | 2.7 | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | -58 | -237** | 85 | -212 | 238 | 110 | -186 |

| SA benefits ($) | 150 | -12 | -187 | -20 | 1 | -206 | -68 |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -0.2 | -1.8 | -1.6 | -0.3 | -0.4 | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -1,925*** | 793** | 2,943*** | 2,859*** | 3,950*** | 10,064*** | 8,999*** |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | -3.2*** | 3.4*** | 5.1*** | 5.3*** | 7.3*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 185* | -213** | 82 | 279*** | 172* | 534** | 506 |

| SA benefits ($) | -46 | -80 | -183*** | -138** | -138** | -460*** | -587*** |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | 5.4*** | -3.1*** | -2.5*** | -2*** | -1 | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | 1,228*** | 374 | 2,229*** | 2,242*** | 2,364*** | 6,835*** | 8,437*** |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | 1.7* | 2.5*** | 3*** | 2.6*** | 3.7*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 63 | 211** | 37 | 180* | 160 | 377* | 651** |

| SA benefits ($) | -625*** | -527*** | -362*** | -333*** | -399*** | -1,095*** | -2,247*** |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -4.7*** | -2** | -2.7*** | -1.7* | -3.1*** | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -364** | -164 | 865*** | 1,087*** | 1,743*** | 3,696*** | 3,168*** |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | -1.9* | -0.2 | 2.2** | 2.3** | 3*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | -54* | -61 | -77 | -168* | 11 | -234 | -348 |

| SA benefits ($) | -89 | -138* | -220*** | -140* | -277*** | -636*** | -863*** |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -3.3*** | -2.9** | -2.5* | -1.8 | -2.8** | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -1,959*** | 2,122*** | 3,945*** | 4,416*** | 4,520*** | 12,595*** | 12,167*** |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | 0 | 1.3** | 1.7*** | 1.6** | 5.5*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 235** | -406*** | -84 | 40 | 251** | 207 | 35 |

| SA benefits ($) | -01 | -20 | -35 | -80** | 24 | -90 | -112 |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | 3*** | -2.2*** | -0.8 | -0.8 | -0.3 | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -376 | -86 | 373 | 429 | 1,378*** | 2,180 | 1,717 |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | 0.5 | 1.5* | 0.2 | 1 | 3.1*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 190 | 206* | 153 | 107 | 104 | 364 | 760* |

| SA benefits ($) | -268*** | -337*** | -249*** | -177*** | -246*** | -673*** | -1,277*** |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -0.8 | -1.9** | -1.7** | -0.6 | -2.1** | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -640*** | -538** | 336 | 249 | 1,027*** | 1,611* | 434 |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | -3.3*** | -0.3 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.9* | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | -15 | 41 | -44 | 30 | -44 | -58 | -33 |

| SA benefits ($) | -79* | -80 | -94* | -117** | -159*** | -371** | -530** |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -1.1 | -0.8 | -0.5 | -1 | -1.3 | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -908*** | 1,745*** | 3,085*** | 3,744*** | 4,318*** | 11,235*** | 11,683*** |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | 0.2 | 1.3** | 1.7*** | 1.2 | 6*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | -22 | -368*** | -87 | -42 | 157 | 28 | -362 |

| SA benefits ($) | -29 | -52* | -103*** | -76** | -21 | -199** | -280** |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | 1.8*** | -0.6 | 0 | -0.6 | -0.9 | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -101 | -913* | -137 | -517 | 301 | -352 | -1,366 |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | -0.3 | -0.1 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 3.3*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 363** | 304** | 238 | 40 | -21 | 256 | 924* |

| SA benefits ($) | -228*** | -231*** | -122* | -105 | -218*** | -445** | -903*** |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -0.8 | 0.2 | -0.1 | -0.7 | -2.8** | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | 69 | -89 | 855** | 653 | 1,512*** | 3,021** | 3,000* |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | -2.3** | 0.3 | 3.8*** | 1.9 | 3.8*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | -65 | 56 | 21 | 65 | 102 | 188 | 178 |

| SA benefits ($) | -74 | -84 | -127* | -121* | -218*** | -465** | -623** |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -0.8 | -0.3 | -1 | -0.6 | -2.2* | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -3,118*** | 1,121*** | 3,680*** | 3,476*** | 3,963*** | 10,935*** | 8,662*** |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | -3.2*** | 2.6*** | 3.6*** | 3.9*** | 4.8*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 422*** | -499*** | -91 | 162* | 192** | 263 | 186 |

| SA benefits ($) | -08 | 01 | -35 | -89* | -41 | -164 | -171 |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | 6.3*** | -3.1*** | -1.6*** | -0.4 | -0.2 | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -34 | 51 | 1,734*** | 1,919*** | 2,552*** | 6,206*** | 6,223*** |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | -2.5*** | 1 | 1.9** | 0.9 | 2.8*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 55 | 00 | -59 | 68 | -104 | -96 | -41 |

| SA benefits ($) | -473*** | -468*** | -364*** | -304*** | -339*** | -1,006*** | -1,947*** |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -1.5* | -2.2*** | -2.7*** | -1 | -2.8*** | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

| Indicators | 1st Year | 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th year | 5th year | Total post-program | Total post-program |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment earnings ($) | -90 | 358* | 1,435*** | 1,783*** | 2,327*** | 5,546*** | 5,814*** |

| Incidence of employment (percentage point) | -3.4*** | 0.5 | 2.5*** | 2.6*** | 2.9*** | N/A | N/A |

| EI benefits ($) | 01 | -69 | -159*** | -131* | 48 | -241 | -309* |

| SA benefits ($) | -53 | -101* | -135** | -98 | -181*** | -414** | -568** |

| Dependence on income support (percentage point) | -3.2*** | -3.3*** | -2.6*** | -1.6* | -1.6 | N/A | N/A |

Significance level: ***1%; **5%; *10%

Appendix D: Cost benefit results

The Aboriginal Human Resources and Development Agreements, predecessors of similar agreements under the strategy, yielded a positive return on investment over the 10-year post-program period for individuals and society as a whole.

Over 12 years, the total net social benefit (government + individual) per participant is estimated at $3,519 or a social rate of return of 45%.

Figure 1: Cumulative impact for active claimant

- Source: Administrative Data Technical Report - Labour Market Data Platform cohort of Aboriginal Human Resources Development Agreements participants from January 1, 2003 to December 31, 2005.

- 1 Program costs include the program expenditure and the loss incurred by society when raising additional revenues, such as taxes to fund government spending.

- 2 Government Deductions include EI premium, CPP/QPP contributions and income tax, which reflects current exemptions that apply to status Indians.

- 3 Employment Earnings include fringe benefits (for example employer paid health insurance, pension contributions) and earnings lost during time spent in the program.

Figure 1 – Text description

| Component analysis | Government |

|---|---|

| Program Costs | -$9,064 |

| Employment Insurance | -$206 |

| Social Assistance | $1,495 |

| Government Deductions | $869 |

| Net present value | -$6,906 |

| Component analysis | Participant |

|---|---|

| Employment Insurance | $206 |

| Social Assistance | -$1,495 |

| Government Deductions | -$869 |

| Employment Earnings | $12,583 |

| Net present value | $10,425 |

Over 12 years, the total net social benefit (government + individual) per participant is estimated at $9,513 or a social rate of return of 119%.

Figure 2: Cumulative impact for former claimant

- Source: Administrative Data Technical Report - Labour Market Data Platform cohort of Aboriginal Human Resources Development Agreements participants from January 1, 2003 to December 31, 2005.

- 1 Program costs include the program expenditure and the loss incurred by society when raising additional revenues, such as taxes to fund government spending.

- 2 Government Deductions include EI premium, CPP/QPP contributions and income tax, which reflects current exemptions that apply to status Indians.

- 3 Employment Earnings include fringe benefits (for example employer paid health insurance, pension contributions) and earnings lost during time spent in the program.

Figure 2 – Text description

| Component analysis | Government |

|---|---|

| Program Costs | -$9,179 |

| Employment Insurance | -$1,133 |

| Social Assistance | $3,338 |

| Government Deductions | $329 |

| Net present value | -$6,646 |

| Component analysis | Participant |

|---|---|

| Employment Insurance | $1,133 |

| Social Assistance | -$3,338 |

| Government Deductions | -$329 |

| Employment Earnings | $18,693 |

| Net present value | $16,159 |

Over 12 years, the total net social benefit (government + individual) per participant is estimated at $9,513 or a social rate of return of 20%.

Figure 3: Cumulative impact for non-EI claimant

- Source: Administrative Data Technical Report - Labour Market Data Platform cohort of Aboriginal Human Resources Development Agreements participants from January 1, 2003 to December 31, 2005.

- 1 Program costs include the program expenditure and the loss incurred by society when raising additional revenues, such as taxes to fund government spending.