Engineered nanoparticles: Health and safety considerations

Upcoming changes to regulations under Part II of the Canada Labour Code

Introducing amendments to regulations under Part II of the Canada Labour Code

On this page

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Definitions

- 3.0 Routes of entry and health effects

- 4.0 Existing Occupational Exposure Limits (OLEs)

- 5.0 Potential for employee exposure in federally regulated workplaces

- 6.0 Methods of exposure evaluation

- 7.0 Control measures

- 8.0 Summary and futures directions

- 9.0 Appendices

Alternate formats

-

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

This Guideline is intended to help health and safety professionals, employers, and employees to evaluate exposures to engineered nanoparticles in workplaces governed by federal jurisdiction and to apply control measures. This document highlights nanomaterials as an emerging occupational hazard by reviewing adverse health effects of exposure and discussing potential for exposure within federally regulated workplaces. This Guideline advises on hazardous chemical substance assessment and management strategies pertaining to nanoparticles. The purpose of this Guideline is to support the Labour Program’s mandate of fostering safe and healthy workplace environments. A simplified companion document to this Guideline for health and safety committees in Canadian federally-regulated workplaces has also been prepared and is presented in Appendix A.

1.0 Introduction

Recent developments in nanotechnology have led to the increased use and production of engineered nanoparticles, particulate matter less than one billionth of a meter in size (10 to -9meter), expressed in the unit of a nanometer (see Definitions). Due to the unique properties of nanomaterials, they have been manipulated for use in a variety of novel applications. Industries that actively use and produce nanoparticles include manufacturing, cosmetics, energy, transportation, research, and medicine. However, the rate at which nanomaterials are being produced far exceeds the rate at which occupational exposure limits are being developed.Footnote 1 Although little human data is available on the potential health effects of nanoparticle exposure, existing literature has drawn a causal relationship between nanoparticle exposure and adverse health effects. Therefore, it is important to evaluate employee exposures and to anticipate future problems in industries that use nanomaterials. The purpose of this guidance document is primarily to help health and safety professionals to evaluate occupational exposures to engineered nanoparticles, including potential health effects, relevant regulations, exposure assessments, and control measures. This guideline can assist qualified individuals who have been mandated by employers to investigate the risk of exposure to nanomaterials. This document highlights current challenges faced by industrial hygienists in the evaluation of nanoparticles, and proposes future directions going forward.

Nanoparticles are simple yet complex hazardous chemical substances. They are simple because they are smaller versions of existing particles, and decades of industrial hygiene research have been devoted to the measurement and analysis of small particulate matter. They are complex because they have dimensions in the nano-scale. In the nanometer range, particles exhibit different chemical and physical properties than their macro counterparts.Footnote 2 For example; nanoparticles have low solubility and very high surface to volume ratios (specific surface area). Nanoparticles also tend to exhibit unique electromagnetic behaviours. These and other characteristics of nanoparticles cause them to interact differently with living systems, often adversely. However, it is also these differences that improve their technological applications. Products containing nanoparticles, or nano-enabled products, have enhanced functionality. The first nanoparticles produced were metals and metal oxides; common examples include titanium oxide, lead oxide, zinc, and silver. The new generation of nanomaterials include carbon nanotubes, fullerenes, and quantum dots.Footnote 3 Carbon nanotubes consist of one or more rolled up sheets of graphene, an allotrope of carbon arranged in hexagons. Fullerenes are spherical, cage-like arrangements of carbon atoms. Quantum dots are spheres of semiconductor material among the smallest size range of nanomaterials (usually 1 to 10 nanometers in any dimension). Overall, engineered nanoparticles have seemingly countless applications.

Although nanoparticles are praised as the next “miracle product” in technological advancement, health and safety considerations must be made. In general, nanoparticles bound within a liquid or solid medium are inert. However, aerosolization of nanoparticles through mechanical agitation (for example grinding) or other means causes them to become inhalation hazards. Unbound nanoparticles can then gain entry into the body via inhalation, skin absorption, or ingestion. In occupational settings, inhalation is by far the most significant route of exposure. Nanoparticles are capable of penetrating into the deep, alveolar region of the lung where gas exchange occurs. Dermal or eye absorption is a concern for unprotected or compromised barriers, through which nanoparticles can penetrate. Ingestion is of minor concern, assuming good personal hygiene practices. Through these pathways, nanoparticles can gain entry into the body. Existing literature suggests that free nanoparticles can have negative health impacts, for example by inducing inflammatory pathways. The small size of nanoparticles allows them to invade immunological defenses that other contaminants may not. In fact, some evidence shows that nanoparticles are able to cross the blood-brain barrier.Footnote 4 It becomes increasingly apparent that the hazard profile of nanoparticles must be seriously evaluated.

Currently, there is a lack of regulations specific to engineered nanoparticles. Efforts made to address this problem have largely been led by European and American authorities, such as the European Commission and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. In general, occupational exposure limits for nanoparticles do not exist. In rare instances, guidance values have been developed to address the immediate need. For instance, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has established a recommended exposure limit for ultrafine titanium dioxide, as well as for carbon nanotubes and nanofibres.Footnote 5,Footnote 6 These guideline values are measured in units of mass per volume, such as mg/m3. However, sources suggest that mass concentrations are less relevant than number concentrations for nanoparticle exposure (this point is discussed in Section 6.0).Footnote 1

Another challenge in the evaluation of nanoparticles is measurement. Traditional equipment used to sample ultrafine particles may not be useful for nanoparticles. Briefly, mechanisms of filtration that work for larger particles (for example, impaction) are less effective for matter in the nanometer range, which are more suitably sampled with other techniques (for example, electrostatic attraction). Innovative thinking must be applied in order to develop appropriate sampling methodologies for engineered nanomaterials. Once these methods are validated, quantification could then be performed with known accuracy and precision. The next step is to reduce employee exposures to levels that are as low as reasonably achievable. Various control measures can be applied to achieve as low as reasonably achievable status. In accordance to best practices of industrial hygiene, controls should be applied in a hierarchical fashion, beginning with elimination/substitution and ending with personal protective equipment. Section 7.0 discusses general control measures and explores control banding as a risk management tool in detail.

In summary, engineered nanoparticles are an emerging occupational hazard. It is necessary to understand that nanotechnology is a rapidly evolving field, thus the information presented in this document reflects the present state of knowledge. Health and safety professionals, employers, and employees are advised to stay current on knowledge regarding nanoparticles to secure optimal health outcomes. Given that future production rates are expected to increase, it is important to take a precautionary approach in dealing with engineered nanoparticles. In instances where insufficient or inconclusive data on a new agent exists, the evaluation of risk cannot be made with adequate certainty. Thus, a cautious approach should be adopted in dealing with the contaminant of interest – this is the fundamental idea behind the precautionary principle. Engineered nanomaterials have inarguably enhanced real-world applications. However, the utmost care must be taken to evaluate engineered nanoparticles in the workplace and to anticipate future industrial hygiene challenges with respect to this hazardous chemical substance.

A simplified companion document to Engineered Nanoparticles: Health and Safety Considerations to provide health and safety committees in Canadian federally-regulated workplaces with a brief overview of occupational exposure to engineered nanoparticles has also been prepared and is presented in Appendix A.

2.0 Definitions

This section outlines relevant terminology as they apply to this guidance document. For other definitions or abbreviations, reference must be made to the Canada Occupational Chemical Agent Compliance Sampling Guideline.Footnote 7

Aerodynamic equivalent diameter: the diameter of a hypothetical sphere of unit density having the same terminal settling velocity as the particle in question.

Aspect ratio: the ratio between an object’s length and width.

Carbon nanotubes: cylindrical sheet(s) of graphene, an allotrope of carbon arranged in hexagons; can be single-walled or multi-walled.

Nanofibre: an engineered particle with one or more dimensions measuring between 1 and 100nm, having an aspect ratio of 3:1 or greater.

- Nanotube: hollow nanofibre

- Nanowire: flexible nanofibre, often electrically conductive

- Nanorod : rigid nanofibre

Nanomaterial (Canadian Standards Association): material with any external dimension in the nanoscale or having internal structure or surface structure in the nanoscale.

Nanomaterial (Health Canada): any manufactured substance or product and any component material, ingredient, device, or structure if:

- it is at or within the nanoscale in at least one external dimension, or has internal or surface structure at the nanoscale

- it is smaller or larger than the nanoscale in all dimensions and exhibits one or more nanoscale properties/phenomena

Nanometer (nm): one billionth of a meter in size (1nanometer = 10-9meter).

Nanoparticle: an engineered particle with one or more dimensions measuring between 1 and 100 nanometers, having an aspect ratio of less than 3:1.

Nanoparticle (natural): a particle that is not manufactured, for example, volcanic ash emissions, forest fire particles, nano-sized liquid droplets (ocean, rain, etc.).

Nanoparticle (incidental): a “background” particle that is not meant to be produced, a by-product of industrial processes, for example, diesel or other vehicle exhaust emissions, welding fumes.

Nanopowder: a collection or aggregate of nanoparticles.

Nanoscale: size range from 1 nanometer to 100 nanometers.

Nanotechnology: the use and manipulation of nanomaterials for use in research and other practical applications.

Ultrafine particle: a particle having an aerodynamic equivalent diameter of 100 nanometers or less.

3.0 Routes of entry and health effects

Nanoparticles become hazardous to human health when there exists an exposure pathway, which includes a source (for example, nanoparticle storage), a recipient (for example, employee), and at least one route of entry by which the agent can become internalized. The 4 possible routes of entry for hazardous chemical substances are inhalation, ingestion, injection, and dermal absorption (including eyes).Footnote 8,Footnote 9 Of these pathways, inhalation is the most common route of exposure for engineered nanoparticles, and indeed of most workplace hazards. A secondary route of entry is dermal absorption, whereby nanoparticles penetrate through unprotected skin and eyes. Accidental ingestion can also occur if the hands become contaminated with the chemical substance, usually caused by poor personal hygiene. Lastly, accidental injection of nanoparticles can occur if sharp objects are common in the workplace handling this contaminant. For more detailed information, the Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety guide on “How Workplace Chemicals Enter the Body”Footnote 10 should be consulted.

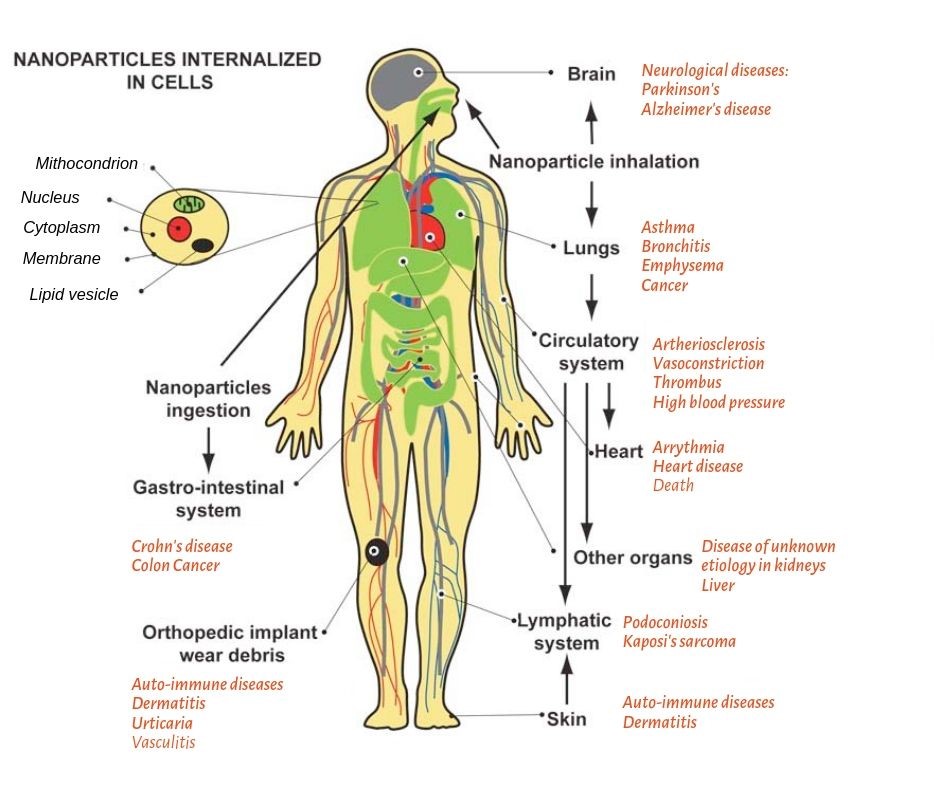

Once nanoparticles enter the body, they disseminate systemically via the cardiovascular system. Nanoparticle exposure is associated with a host of adverse pulmonary, immunological, cardiovascular, neurological, and carcinogenic effects. Furthermore, nanoparticles are assumed to have the same toxic properties as their macro forms (for example, carcinogenicity, sensitizing ability).Footnote 11 Figure 1 illustrates diseases associated with exposure to engineered nanoparticles, but this list is not exhaustive.Footnote 12 For example, nanoparticles can dissolve in the moist outer membrane of the eyes called the cornea and cause local inflammation (keratitis). In the consideration of exposure-related health effects, the following factors must be evaluated: properties and toxicology of the nanomaterial, employee exposure concentrations, exposure duration and frequency, and effectiveness of control measures.Footnote 13 This section focuses on inhalation and skin/eye absorption as predominant routes of entry for nanoparticles. Furthermore, this section reviews toxicological data related to nanoparticle exposure and presents important clinical findings regarding adverse health effects.

Figure 1 – Text version

Nanoparticles internalized in human cells include mitochondrion, nucleus, cytoplasm, membrane and lipid vesicle. They can enter the body via three major routes of entry: inhalation, ingestion and skin absorption. Once nanoparticles are inhaled through the nose and mouth, they disseminate via the cardiovascular system. The following organs may be affected when person is exposed to nanoparticles: brain - leading to neurological diseases, such as Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s disease; lungs – leading to asthma, bronchitis, emphysema, or cancer; circulatory system – leading to arteriosclerosis, vasoconstriction, thrombus, or high blood pressure. Once nanoparticles reach circulatory system, they can also be distributed to heart - causing arrhythmia, heart disease, or death; other organs - causing disease of unknown etiology in kidneys or liver; and lymphatic system - causing podoconiosis, or Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Once inside the mouth (nanoparticles ingestion), nanoparticles pass down to gastro-intestinal system which may lead to Crohn’s disease, or colon cancer.

Nanoparticles can also enter the body through skin, which may lead to auto-immune diseases or dermatitis. Exposure via skin may also affect the lymphatic system leading to such diseases as podoconiosis or Kaposi’s sarcoma.

It must be noted that orthopedic implant wear debris may also be affected leading to auto-immune diseases, dermatitis, urticarial or vasculitis.

For more information, consult the Exposure pathways and major diseases associated with nanoparticle exposure as evidenced by epidemiological and clinical studies can be found in the publication by Buzea et al., 2007Footnote 12: Nanoparticles internalized in cells.

3.1 Inhalation exposure to engineered nanoparticles

Of the possible routes of entry, inhalation is the most significant pathway by which an employee is exposed to nanoparticles. In a typical 8 hour shift, the lungs exchange between 2,800 litres to 10,000 litres of air.Footnote 10 The extent of inhalation exposure is governed by nanoparticle concentrations in the workplace and the respiratory characteristics of the employee(s). For example, an employee performing heavy labour would take in greater volumes of air at greater frequency than would a sedentary employee, and therefore be exposed to greater concentrations of nanoparticles. Furthermore, heavy labour causes an individual to engage in mouth breathing, which affects the deposition pattern of inhaled particles in the respiratory tract. The deposition pattern of a contaminant affects health outcomes. Distribution of nanoparticles in the respiratory system is principally bimodal, with greatest deposition in the nasopharyngeal (nose and pharynx) and alveolar (gas exchange) regions. In the nasopharyngeal region, mechanisms such as impaction trap nanoparticles. In the deeper regions of the lung, nanoparticles collect onto alveolar surfaces mostly via diffusion. Mechanisms of filtration are significant for sampling considerations, to be discussed in Section 6.3.

Defense mechanisms of the human respiratory system are specific to different regions of the lung: saliva in the nasopharyngeal region, mucociliary escalator in the tracheobronchiolar (trachea and bronchioles) region, and macrophages in the alveolar region.Footnote 1 The mucociliary escalator consists of cilia and mucous lining the bronchioles. Cilia are small hair-like cells that sweep contaminants upwards, leading to retrograde clearance of contaminants through the trachea. Saliva and bronchiolar mucous are swallowed and subsequently excreted through the digestive system. The gas exchange region, which consists of millions of alveoli, is not lined with cilia. Instead, specialized immune cells called alveolar macrophages engulf contaminants and migrate towards the bottom of the mucociliary escalator. Overall, these mechanisms seek to destroy or control agents that may be harmful to the body.

When full entrapment is not possible, such as in the case of very long nanofibres, serious health problems may arise. Factors that influence the toxicity of nanofibres include composition, length, diameter, shape, and persistence. In experiments involving rat and mice models, studies have shown that single- and multi-walled carbon nanotubes induce pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis.Footnote 14,Footnote 15 Although studies involving respiratory exposure to engineered nanomaterials have largely been conducted in animal models, several researchers agree that results from these studies can be extrapolated to humans. In fact, literature in this field has likened the health effect of nanofibres to those of asbestos.Footnote 16 A pilot study in 2008 showed that length plays a dominant role in mediating nanofibre toxicity, where longer carbon nanotubes are more potent than their shorter counterparts. This may be attributed to the fact that macrophages have difficulty in engulfing long particles. Nanofibers compromise the macrophage cell membrane, causing it to lyse (burst). As a result, cell contents are released into the surrounding environment. Much of this is lysate which is comprised of signaling molecules that can activate the inflammatory response, such as cytokines (proteins that direct cell movement) and fibrinogen (a glycoprotein that mediates clotting). A non-specific inflammatory cascade ensues. Neutrophils and macrophages are recruited to the site of lysis in an attempt to contain the foreign agent, in this case the nanomaterial. However, excessive macrophage activation leads to the production of reactive-oxygen species that can cause tissue injury. A prolonged state of immunological imbalance progressively worsens health, such that over time, lung fibrosis (scarring) reduces gas exchange efficiency and overall pulmonary function.

Human epidemiological evidence has echoed similar effects. Employees exposed to ultrafine particles, such as welding fumes, have suboptimal spirometry (lung function test) parameter, such as full expiratory volume in 1 second. Studies on European carbon black manufacturing have demonstrated that exposed employees experience adverse respiratory symptoms (for example, coughing) and higher incidence of lung diseases.Footnote 17

Researchers noted elevated rates of the following illnesses among nanoparticle-exposed individuals:

- pulmonary fibrosis

- pulmonary edema

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- lung cancer

Clinical studies have demonstrated adverse effects of exposure at a cellular level. For instance, researchers have shown that exposure to carbon nanoparticles causes blood leukocyte retention in the lungs.Footnote 18 The findings of this study are significant because they suggest that nanoparticle exposure via inhalation can induce cardiovascular effects. The exact mechanism remains unknown, although evidence suggests that chronic inflammation induces vasoconstriction and high blood pressure.

The difficulty in conducting epidemiological studies is that ambient concentrations of ultrafine particles (for example, diesel exhaust) can rarely be distinguished from workplace concentrations of engineered nanoparticles. Therefore, health effects arising from nanoparticles cannot be solely attributed to occupational exposures with absolute certainty. With the exception of titanium dioxide and carbon black, no epidemiological studies have been conducted to assess the health effects of nanoparticle exposure.Footnote 19,Footnote 20 The next step should be to expand research in this field, with particular focus on employee exposures.

3.2 Dermal and eye exposure to engineered nanoparticles

Skin absorption is another significant route of entry in addition to inhalation. Skin is the first line of defense in the innate immune system and consists of three layers: epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous. Literature shows that due to their small size, engineered nanoparticles can readily penetrate through skin and mucosal barriers.Footnote 21 However, size is not the only determinant for skin penetration. For instance, a study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles (engineered for sunscreen manufacturing) found that particulates suspended in an oil-based solution penetrate deeper and faster into the skin than those immersed in an aqueous solution.Footnote 22 In general, lipophilic compounds have enhanced uptake through the skin than hydrophilic compounds. The extent of nanoparticle penetration seems to be restricted to the stratum corneum, the keratinized outermost layer of the epidermis. However, deeper penetration is possible due to the rich supply of nerve endings, blood vessels, and lymphatic vessels present in the skin. Compromised skin barriers, including abrasions and lesions, cause further concern for skin uptake of nanoparticles. Hair follicles also facilitate shunting of surface nanoparticles into the subcutaneous layers of the skin, which presents concern for hairier parts of the body such as the forearms.Footnote 23

The surface of the eyes, albeit small relative to the surface of the skin, presents a unique route of entry for nanoparticles. In a rabbit experiment, researchers demonstrated that titanium dioxide nanoparticles applied to the ocular surface induced damage.Footnote 24 There was a notable decrease in the number of mucous-secreting goblet cells in the conjunctiva, which weakens the eyes’ immune defense and allows for increased uptake of hazardous chemical substances through the ocular surface. Some concern has also been brought up with regards to neuronal exposure via ocular entry. Engineered nanoparticles have been shown to gain access to the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) via retrograde translocation along neurons.Footnote 25 Overall, efforts are still underway in characterizing the skin and eyes as routes of entry for nanoparticles. The health effects of such exposures are not well known, although they have been associated with dermatitis, sensitization, and irritation.

4.0 Existing occupational exposure limits

To protect the health of employees in the workplace, occupational exposure limits to various hazardous chemical substances have been developed by industrial hygienists in conjunction with policy-makers. The purpose of occupational exposure limits is to provide regulatory limits of exposure for airborne contaminants. According to Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations Section 10.19(1), employees shall be kept free from exposure to a concentration of an airborne chemical agent in excess of values adopted by the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists.Footnote 26 In other words, legal thresholds of exposure to hazardous chemical substances in Canadian federally regulated workplaces are equivalent to the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists Threshold limit values with a few exceptions, which have occupational exposure limits of their own. Threshold limit values are health-based values that represent concentrations at which nearly all employees may be repeatedly exposed over a working lifetime without adverse health effects. The development of Threshold limit values is a long and complex process. Briefly, the derivation of occupational exposure limits/Threshold limit values calls for an extensive review of literature focusing on studies involving dose-response relationships, the identification of no/low observed adverse effect levels, the target organs or systems of each chemical agent, and the application of uncertainty factors.Footnote 27

There are 3 types of exposure limits:

- Threshold limit value-time weighted averages: occupational exposure limit for a full 8-hour shift

- Threshold limit value-short term exposure limit: occupational exposure limit for a 15-min period in an 8-hour shift

- Threshold limit value-ceiling limit: peak occupational exposure limit at any given time over an 8-hour shift

A single hazardous substance may have more than one type of Threshold limit lalue, but Threshold limit values have not been developed for all chemical contaminants. Engineered nanoparticles are one such example. Globally, there is a lack of occupational exposure limits specific to nanoparticles despite the need to control employee exposures to this hazardous substance.Footnote 28 Heterogeneity in the composition of nanomaterials, unique chemical/physical properties of nanomaterials, and limited toxicological data all present challenges for occupational exposure limit development. Without occupational exposure limits, measured exposure concentrations can only be compared to guideline values. Recommended exposure limits and nano reference values are 2 such examples. The United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has established recommended exposure limits for nanoscale titanium dioxide (300 microgram/meter3) and carbon nanotubes/nanofibres (1 microgram/meter3), which represent concentrations at which employees may be exposed over the working lifetime assuming good workplace control practices.Footnote 5,Footnote 6 Dutch nano reference values are guideline 8 hr-time weighted averages that have been developed with the precautionary principle in mind (see Appendix B for nano reference values by nanomaterial class).Footnote 29 Although recommended exposure limits and nano reference values have not been adopted by law in their respective countries, these values are important tools for industrial hygienists in making risk management decisions.

Currently, one project is expected to influence Canadian occupational standards with respect to nanoparticle exposure. In 2012, the Chair of the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists Threshold limit value Committee declared that efforts are underway in the development of Threshold limit values for ultrafine zinc oxide and titanium dioxide particles.Footnote 30 These metal oxides are used in a variety of industries, such as paint and sunscreen manufacturing. If Threshold limit values for zinc oxide and titanium dioxide become published by the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists, these values will serve as occupational exposure limits in federally regulated workplaces in Canada.

Overall, there is a serious lack of regulations specific to engineered nanoparticles worldwide. However, the Canadian federal government is expected to adopt a new nanoparticle subsection under Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations in the near future (see Appendix B for details). This proposed policy reflects the need to address nanoparticles as an emerging occupational hazard. The next step for health and safety authorities should be to review existing guideline values and to decide whether they should be written into law. Such considerations are underway for Dutch nano reference values. To inform the occupational exposure limit development process, further research must be conducted on the toxicological effects of various engineered nanoparticles.

5.0 Potential for employee exposure in federally regulated workplaces

In Canada, the Labour Program is the occupational health and safety authority for federally regulated workplaces under Part II of the Canada Labour Code. Workplaces under federal jurisdiction employ nearly 1 million Canadians (about 10% of the national workforce) in industries such as federal public service, interprovincial trucking, railways, airlines, banking, telecommunications, grain elevators, and flour mills.Footnote 31 Nanotechnology is being applied to many such industries, so it is important to assess and control employee exposures. Through a literature review, the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work determined that significant employee exposure to nanoparticles occurred in the following industries: health care, energy, transportation, and chemical manufacturing.Footnote 32 This section examines the potential for employee exposure in federally regulated workplaces, using the transportation sector as a case study.

As engineered nanoparticles progress through their life cycle, they become less of an occupational hazard and more of an environmental hazard.Footnote 1 Therefore, there is greater risk for employee exposure in workplaces that actively produce and/or use nanoparticles than those downstream. The potential for nanoparticle exposure largely depends on the type of workplace: are nanoparticles being manufactured, used, and/or disposed of in this facility? In a workplace where nanomaterials or nano-enabled products are present, employee exposure could theoretically occur anywhere within the facility. However, researchers have found that certain processes generated significant airborne concentrations of nanoparticles.Footnote 33 All of these processes are found as part of various activities in federally-regulated workplaces, including:

- production

- transferring and packaging

- filtration or thermal treatment

- spraying or vacuum cleaning

- mixing

- cutting or grinding nano-enabled products

Nanoparticles are produced by grinding bulk material down into the nanoscale (top-down approach) or condensing nanoparticles onto a nucleus (bottom-up approach). Containment of nanoparticles is difficult in 2 approaches, but particularly with top-down production because it involves grinding and milling. In contrast, the use of closed reactors in bottom-up manufacturing means there are fewer opportunities for exposure to take place, although it does happen when the vessels are opened. Regardless of the manufacturing approach, it is important to implement appropriate control measures. Wet cutting, the use of fluids to flush out debris during cutting, is 1 such example. In a study on the processing of nano-enabled composite materials, researchers found that wet cutting reduced airborne carbon nanotube concentrations down to background levels.Footnote 34 Since free nanopowder presents a greater inhalation hazard than those bound within a liquid or solid medium, wet milling may be an effective control measure for reducing respiratory exposure amongst employees. Section 7.0 discusses other control measures in detail.

Nanotechnology is becoming increasingly popular in the Canadian automotive and aerospace industries. The automotive sector is exploring how engineered nanoparticles can be used in the development of stronger, lighter, and more corrosion-resistant materials. For example, carbon nanotubes can be used to reinforce vehicle bodies. Since carbon nanotubes have 100 times the strength yet a fraction of the weight of steel, the incorporation of carbon nanotube in automotive parts can be expected to reduce fuel consumption.Footnote 35 A detailed case study on the risks from exposure to multi-walled carbon nanotubes in the United States and Canada can be found in the document entitled “Risk Assessment/Risk Management of Nanomaterials: Case Study of Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes” by the Regulatory Cooperation Council Initiative – Task Group 3.Footnote 36 Other examples of nano-enabled materials in the transportation sector include fuel-cells, sensors/detectors, coatings, and catalysts.Footnote 37 Despite the usefulness of nanotechnology, the potential for exposure remains a threat to employees’ health. In a manufacturing setting, employees can be exposed to nanoparticles during unpackaging, grinding, and spraying processes.Footnote 38 Employees can also be exposed at mixing tanks where nanopowders are combined with other substances to create composite materials. These processes can potentially introduce nanoparticles into the air, which causes concern for exposure via the inhalation and skin/eye deposition routes. Bound nanoparticles cause less of a health concern, but any abrasive process (for example, sanding, prolonged wear) can re-aerosolize these particles.

Overall, little is known about nanoparticle exposures in Canadian federal sectors. Given that nanotechnology has become increasingly popular with manufacturers, efforts should be made to assess the nature of employee exposures in federally regulated workplaces. The obligation rests upon employers to conduct hazard investigations for the protection of employees’ health. For more information on North American and international regulations relevant to nanomaterial management, reference should be made to the Canada-United States Regulatory Cooperation Council’s Nanotechnology Initiative Final Report – in particular Tables 1, 2, and 14.Footnote 36 The next two sections discuss how employee exposures to nanoparticles are assessed and controlled.

6.0 Methods of exposure evaluation

Under Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations Section 10.4 (see Appendix B), employers must hire qualified health and safety professionals to conduct hazard investigations. This involves consulting with an industrial hygienist, who develops a sampling strategy, performs an on-site survey, and prepares a report with results and recommendations. The purpose of industrial hygiene surveys is to qualitatively and quantitatively assess the exposure scenario. The evaluation of employee exposures requires significant technical expertise. No single instrument can suitably sample every hazardous chemical substance, so one of the most important decisions that industrial hygienists make is the selection of sampling instrumentation. Traditional sampling strategies for very small particles may not be appropriate for nanoparticles; this section discusses this point in detail and explores challenges associated with nanoparticle sampling. Furthermore, this section explains how hazard investigations are conducted for inhalation and dermal exposures to hazardous chemical agents.

6.1 Risk assessment and risk management

When a hazardous chemical substance has at least one exposure pathway to gain entry into the body, there is risk to employees’ health (risk = hazard x exposure).Footnote 39 The degree of risk can be determined through a comprehensive risk assessment according to Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations subsection 10.4(2). For more information, reference may be made to the Institut de recherché Robert-Sauvé en santé et en sécurité du travail Best practices guide to synthetic nanoparticle risk management and/or the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists Occupational risk management of nanoparticles.

Risk assessment consists of the following 4 elements:

1. Hazard identification/recognition

Determines the scope of workplace hazard(s) to be studied, including their presence, location, composition, and chemical/physical properties.

2. Hazard assessment/investigation

Evaluates potential health effects that may occur as a result of exposure to the workplace hazard(s) by reviewing toxicology literature and referring to safety data sheets (see Appendix C – reference made to a safety data sheet for titanium dioxide as an example). Hazard investigations can be done by following the Labour Program’s Hazardous Substances Management Guide.

3. Exposure assessment

Assesses the type, magnitude, and frequency/duration of exposures, including exposure pathway(s) and the employees who are affected.

4. Risk characterization

Culminates knowledge obtained from the 3 previous elements and interprets the nature of risks associated with exposure (for example likelihood of illness and level of severity).

The industrial hygienist performs all of the above steps in order to obtain information about the exposure scenario in a workplace. This data is useful for making decisions regarding risk management, the implementation of control measures to reduce employee exposures (see Section 7.0). For more information on how to assess and control for exposure to nanoparticles, reference may be made to the Institut de recherché Robert-Sauvé en santé et en sécurité du travail Nanoparticle measurement, control, and characterization document. The qualified person must use factors described in Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations 10.4(2) to conduct a risk assessment, or utilize a method that is widely accepted by the industrial hygiene community. The next subsection discusses how airborne chemical hazards can be assessed, with a focus on the technical workings of sampling equipment.

6.2 Challenges in the sampling methodology for nanoparticles

Nanoparticles present complications for sampling.Footnote 40 Given the heterogeneity and unique chemical/physical properties of nanomaterials, there is no scientific consensus on what to sample, how to sample, and how to interpret sampling results. 3 challenges must be addressed in the evaluation of nanoparticles as an occupational hazard:

1) Which parameter(s) should be sampled

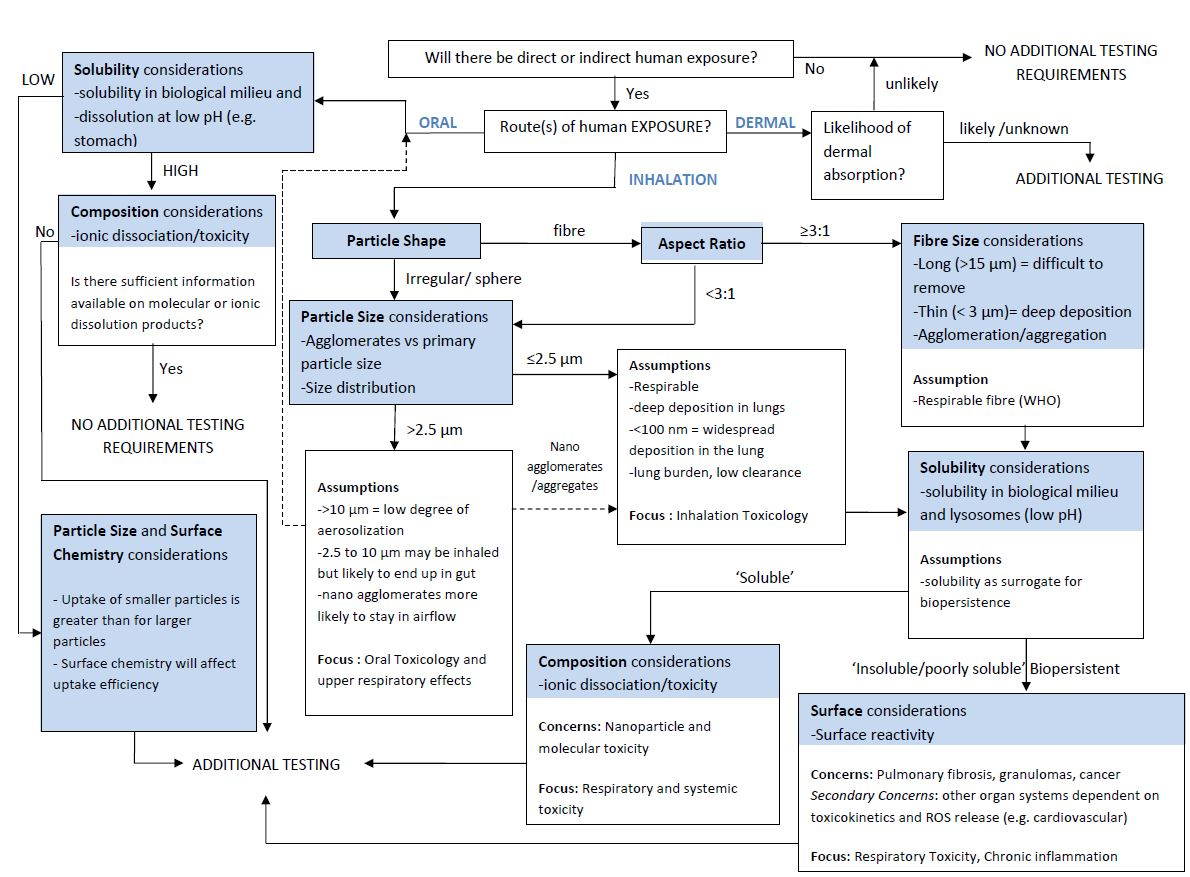

Many metrics can be used for characterizing nanoparticles: mass concentration, surface area, number concentration, surface chemistry, and size/shape of the particle. Traditionally, airborne concentrations of hazardous chemical substances have been used to quantify employee exposures. For agents in a solid or liquid droplet form, concentrations are almost always measured in units of mass per volume of air (such as miligram/metre3). Generally speaking, this is a simple and effective way to measure aerosols because most substances have appreciable mass. In contrast, nanoparticles have such low mass that gravimetric analysis is not an appropriate method of sampling. Recommended exposure limits for nanoparticles are very low (for example National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health advises an 8-hour time-weighted average of 1microgram/metre3 for carbon nanotubes), and existing analytical methods are rarely sensitive enough to detect such low concentrations.Footnote 1 With the exception of nanoparticle agglomerates (groupings of many particles), mass concentrations are non-ideal units for nanoparticle sampling. Experts have surface area and number concentration as alternative parameters. Surface area appears to be a suitable metric because the high surface area to volume ratio of nanoparticles mediates their biological toxicity. However, instruments capable of detecting surface area have a detection upper limit of 1,000 nanometre in particle diameter.Footnote 1 Since the surface area of a particle is a function of its square diameter, micro-sized particles will dominate the measurement as opposed to the nanoparticles. Number concentration is a third metric for quantifying nanoparticles, measured in units of particles per volume air. Number concentration is generally preferred over mass concentrations for nanoparticle measurements. The laws of physics affect the sampling efficiency for all of these metrics. Thus, a combination of parameters is typically used to obtain information about the quantity of nanoparticles in a workplace. In 2015, the Canada-United States Regulatory Cooperation Council developed an algorithm for determining metrics of concern for different types of nanomaterials that may be useful for health and safety professionals (see Appendix B, Figure B1).

2) What are some practical limitations for sampling

There are several limitations for sampling nanoparticles, some of which affect industrial hygiene surveys in general. Firstly, sampling equipment is sometimes bulky and incapable of data-logging concentrations over time. The instruments require regular calibration and maintenance, which can be costly. Secondly, there are few accredited labs that can analyze nanoparticle samples due to lack of technology, expertise, or both. Lastly, work processes involving nanoparticles may be infrequent (for example, occurring 2 to 3 times per week for only hours at a time). This presents a problem for obtaining an exposure measurement that is representative of typical exposures, thus making it difficult to compare such numbers to guideline values. Lastly, the majority of sampling equipment and methods is simply not sensitive enough to detect very low concentrations of chemical agents. Nanoparticles have only emerged as an occupational hazard recently, so it will take time to make current instruments suitable for nano-specific sampling.

3) How should background levels and incidental nanoparticles be accounted for

It is difficult to distinguish between background levels of nanoparticles (natural and incidental) (see Definitions) from nanoparticles that are deliberately manufactured. One option is to sample in the workplace when nanoparticle-manufacturing processes have shut down. Another option is to sample outdoor concentrations of nanoparticles, but both approaches are problematic in their own ways. The default method for determining background levels is to sample in a “clean” area in the same facility that nanoparticles are manufactured in. For example, the industrial hygienist could perform air sampling in the administrative office.

6.3 Inhalation exposure assessment

Prior to conducting the on-site exposure assessment, the industrial hygienist must develop a sampling strategy. Decisions must be made with respect to the contaminant(s) that will be sampled, sampling location(s), and sampling duration. These factors affect the selection of equipment and analytical methods. The Canadian Occupational Chemical Agent Compliance Sampling Guideline outlines procedures that should be followed in workplace hazard investigations.Footnote 7 After the sampling has been conducted, employee exposures to a hazardous chemical substance are compared to corresponding occupational exposure limits (American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists Threshold limit values). This is how inhalation exposure assessments are done for most airborne hazards.

A wide selection of instruments exists for the purpose of sampling airborne chemical agents. They are capable of sampling different states of matter and distinguishing between particles of different size. In industrial hygiene, very small particles are routinely collected with size-selective sampling devices. Such devices distinguish between fractions of particles based on their aerodynamic equivalent diameter. This is a useful characteristic because smaller particles penetrate different regions of the human pulmonary tract than large particles. The 3 size fractions that can be sampled by existing equipment are the following:

- inhalable fraction deposits anywhere in the respiratory tract

- thoracic fraction deposits in the nose, throat, bronchus, and bronchioles

- respirable fraction deposits in the alveoli

To date, no sampling or analytical methods have been developed for nanoparticles specifically. Thus, methods developed for other hazardous chemical agents have been used as surrogates in nanoparticle hazard assessments. Listed below are some methods that have been developed and used by National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health for nanoparticle sampling:

| Method | Substance or purpose | Samplers |

|---|---|---|

| 0600 | Titanium dioxide (respirable) | Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) filter Cyclone |

| 5040 | Carbon nanotubes and nanofibres (elemental carbon) | Quartz-fibre filter Cyclone Thermal optical analyzer |

| 7402 | Visualizing sample | Mixed cellulose ester filter Size-selective sampling device Transmission electron microscope |

| 7300 | Identifying elements | Mixed cellulose ester filter Size-selective sampling device Inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectroscope |

A list of instruments currently being used to monitor nanoparticle exposures can be found in Table C.1 of the Canadian Standard Association Z12885. Efforts are underway in the development of sampling devices for nanomaterials. In the United States, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health is developing a personal nanoparticle sampler that could be used to determine employee exposures; a personal nanoparticle sampler consists of a respirable cyclone plus an impactor fitted onto a close-faced filter cassette.Footnote 41 National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health is also looking into the use of direct-reading instruments and wipe sampling in initial industrial hygiene surveys. In Europe, an initiative called NANODEVICE is developing practical (affordable and portable) equipment for assessing nanoparticle concentrations in the workplace. Until these devices are validated and released, the above methods will continue to be used by industrial hygienists in performing inhalation exposure assessments for nanomaterials. For information on the progress of sampling guideline development, reference must be made to the Canada-United States Regulatory Cooperation Council’s Nanotechnology Initiative Final Report – in particular Section 4.2.Footnote 36

6.4 Dermal exposure assessment

Dermal exposure assessments are not as well developed as those for inhalation, but the skin can be a significant route of exposure. In fact, the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists developed a skin notation to mark agents with Threshold limit values for which skin is an important route of entry. Skin exposure to hazardous chemical substances can occur in 3 waysFootnote 42:

- contact: skin touches an object or surface contaminated with the substance

- deposition: airborne forms of the substance settle onto the skin

- immersion: skin is submerged in or splashed with the substance or its mixture

There is no scientific consensus on the best way to conduct skin exposure assessments. A non-quantitative method is to use fluorescent visualization. Tracer compounds can be added to the substance of interest to visualize its presence on contaminated surfaces. Special lamps can also be used to see airborne particles and to evaluate the effectiveness of local exhaust ventilation. A quantitative method is to remove substances on the skin with wash solutions or wipes, and subsequently analyzing the samples. One new method is to use surrogate skin, such as a cotton pad applied to the forearms, to estimate exposure. A more invasive method is to use small skin biopsies to analyze nanoparticle burden. A mice study showed that elemental analysis of skin snips correlate with the total administered dose of gold nanoparticles.Footnote 43 Therefore, the skin is an important organ for nanoparticle accumulation and skin biopsies may be useful in quantitative exposure assessments. The American Industrial Hygiene Association has developed The Industrial Hygiene SkinPerm, software, a practical tool for estimating dermal exposures to hazardous chemical substances. There is a similar toolkit that is part of the RISKOFDERM project.

7.0 Control measures

Hazardous substances, including engineered nanoparticles, are governed under Part X of Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations. Part X dictates how hazards should be stored/handled/used, along with how hazard investigations are to be conducted. Importantly, Section 19.5(1) Preventive Measures outlines how control measures must be implemented in order to reduce employee exposures to hazardous substances. Reference to the Labour Program’s Hazardous Substances Management Guide may be helpful for conducting workplaces investigations related to hazardous substances. Investigations must be performed in the presence of the work place health and safety committee (see Section 135.7e of the Canada Labour Code). After a risk assessment is performed, control measures may need to be implemented for the reduction of employee exposures to hazardous substances. Overexposure scenarios certainly necessitate the application of controls, but it is equally important to reduce concentrations which are within the legal limits to be most protective of employees’ health. The selection and implementation of controls require expertise from the health and safety professional, along with input from employers and employees for suitability.

Controls must be applied in a hierarchical fashion. In order of importance, control measures used to reduce employee exposures include:

- elimination of a hazardous chemical substance from the workplace

- substitution of the substance with another substance that is less toxic to health

- isolation of the substance in closed chambers or rooms

- engineering controls such as ventilation or design/process modification

- administrative controls such as shift rotation or access restriction

- personal protective equipment such as respiratory or skin protection

These control measures have corresponding sections under Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations Part X Hazardous Substances (see Appendix B for details). As exposure concentrations approach the occupational exposures limits or guideline values, more vigorous control methods are needed. Personal protective equipment in general should be viewed as a last resort in protecting employee from occupational hazards. However, in certain situations where, for example, it is not feasible to apply engineering controls to prevent employee exposures, it becomes necessary that respiratory protection be used. Legislation requires employers to comply with the Canadian Standard Association Standard Z94.4 Selection, Use, and Care of Respirators in administering respiratory protection programs. An overview on personal protective equipment use for nanomaterials can be found in the American Industrial Hygiene Association publication titled “Personal Protective Equipment for Engineered Nanoparticles”Footnote 44 This resource may be useful to employees who would like to learn more about how they can reduce nanoparticle exposures in the workplace. The next subsection discusses the technique of control banding as they apply to engineered nanomaterials.

7.1 Control banding

Control banding is a useful risk management tool for reducing employee exposures to hazardous chemical substances.Footnote 45 Substances of a similar hazard level (for example, carcinogens, irritants) are grouped into “bands”, and a particular set of control measures (for example, local exhaust ventilation, good work practices) are assigned to each band. The purpose of control banding is to provide a simple, easy-to-use framework for employers to manage occupational hazards. Control banding is a particularly suitable technique for small organizations that may not have access to occupational health and safety expertise. The pharmaceutical industry pioneered control banding in order to ensure that employees could safely work with chemicals of uncertain or unknown toxicity. The same remains true today: control banding is typically used for substances with limited toxicological data and substances without occupational exposure limits, including nanoparticles.

The first step of control banding is to assign the substance of interest to a particular band. Substances within the same hazard band should be similar in 1 or more of the following ways:

- chemical and physical properties

- biological toxicity

- types of processes where the substance is used

- route of entry

- exposure duration and frequency

- concentrations of the substance in the workplace

For every band, there is a list of control measures that have been developed to be suitable for the particular hazard level. For example, general ventilation and personal protective equipment may be recommended for a band of hazardous substance known to be skin irritants. Very toxic substances that are present in large amounts in the workplace are managed with much more stringent controls than substances with low toxicity and concentrations. There are several advantages to using the control banding technique. Firstly, control banding is a practical tool that non-experts can easily understand and apply. Secondly, substances with no occupational exposure limits can be assigned to a particular hazard band and managed according to the specified control measures for that band. One limitation of control banding is that it may not be sufficient in controlling hazards in workplaces where exposure levels are highly variable (defined as a geometric standard deviation of greater than 2.0).Footnote 7

Usually control banding by level of hazard includes:

- non-toxic substances

- moderately toxic substances

- substances causing death or severe health effects

- special cases (for example cancer) for situations of the highest risk.

Control banding is not intended to replace stricter control measures already being practiced in a workplace. Rather, it is meant to advise the implementation of control measures in a practical sense. The United Kingdom Health and Safety Executive developed one of the most popular control banding models used by professionals and employers: the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Essentials. More information regarding control banding is expected to be published by the Labour Program in 2017.

8.0 Summary and future directions

In summary, engineered nanoparticles are an emerging occupational hazard. The speed of nanotechnology development, coupled with mounting evidence regarding adverse human health effects, necessitate the use of the precautionary principle in dealing with nanomaterials. Exposure to nanoparticles has been known to be toxic to cardiovascular, neurological, and pulmonary systems. Since employees are the first to be exposed to engineered nanoparticles, efforts to address this hazardous chemical substance in the workplace should be made a priority. Future directions in dealing with engineered nanoparticles are as follows:

- Occupational exposure limits should be developed for different types of nanomaterials based on the current state of knowledge. The American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists is currently developing Threshold limit values for nanoparticles of zinc oxide and titanium dioxide. By setting legal thresholds of acceptable exposure, employers can be held accountable for implementing control measures for reducing employees’ exposure to nanomaterials.

- Sampling instruments should be modified or created to suitably sample various parameters of nanoparticles. Since physical characteristics (for example, surface area) mediate toxicity more so than composition, sampling equipment should be able to sample the appropriate metrics. The ideal sampling device would be able to measure number concentrations, mass concentrations, and surface area in a size-selective manner. The instrument should also be portable and capable of data logging over a period of time. Given that inhalation is a primary route of exposure, development in this area should be focused on obtaining airborne measurements.

- Sampling and analytical methods specific to different types of nanomaterials should be developed. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health methods that have not been specifically developed for nanoparticles are being used as surrogate methods in industrial hygiene surveys. The development of suitable methods would serve to standardize how risk assessments are conducted by health and safety professions.

- The control banding approach should be adopted by regulatory bodies and employers. Control banding is a simple technique for reducing employee exposures to substances with little toxicological data and no occupational exposure limits, including engineered nanoparticles. Small- to medium- sized organizations may consider using control banding as a practical tool for reducing employee exposures in the absence of technical expertise.

- More research on the health effects of nanomaterial exposure should be conducted to create a fuller toxicological profile. Initial studies have shown that nanoparticles cause acute illnesses. The widespread incorporation of nanomaterials in manufactured products draws attention to the need of investigating long-term health effects as well. Furthermore, research on the effectiveness of personal protective equipment in protecting the respiratory and skin health of employees with regards to nanoparticle exposure should be conducted.

In conclusion, engineered nanoparticles are an important occupational hazard. There is potential for employee exposure in many types of workplaces, including those under federal jurisdiction (for example, transportation). No Canadian regulations specific to the evaluation and control of nanoparticle exposures currently exist, however one policy that makes reference to the Canadian Standard Association’s Standard Z-12885 is expected to be adopted in the Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations Part II in the near future. In the meantime, employers are obligated to ensure a healthy and safe workplace for employees with regards to all hazardous chemical substances. Proper training and application of the hierarchy of controls may be useful in reducing employee exposures to novel substances such as engineered nanomaterials. The Canada-United States Regulatory Cooperation Council’s Nanotechnology Initiative published a report that contains useful regulatory on engineered nanomaterials that may be of interest to health and safety professionals. Overall, more research must be conducted to develop tools that will enable technical professionals to assess the extent of nanoparticle exposures in Canada.

9.0 Appendices

9.1 Appendix A – Introduction to engineered nanoparticles for workplace health and safety committees

Background

The purpose of this document is to provide health and safety committees in Canadian federally-regulated workplaces with a brief overview of occupational exposure to engineered nanoparticles. It is a simplified companion document to Engineered Nanoparticles: Health and Safety Considerations, a 34-page guideline developed by Employment and Social Development Canada – Labour Program. This abbreviated document provides information on health effects, routes of exposure, control measures, and legislative requirements related to engineered nanoparticles. For more information, consultation should be made to the full guideline.

What are nanoparticles?

Recent developments in nanotechnology have led to the increased use and production of engineered nanoparticles. Simply put, nanoparticles are tiny materials approximately one billionth of a meter in size (10-9meter). For a sense of scale, an average human hair is 70,000 nanometers in thickness whereas nanoparticles measure between 1 and 100 nanometers. Nanoparticles are most commonly made of carbon and metals or metal oxides. They take on different shapes, including particles, sheets, tubes, and spheres. Nanoparticles have unique chemical and physical properties that distinguish them from their larger counterparts. For example, the high surface area to volume ratio of nanoparticles increases their biological reactivity, possibly making them more toxic. Nanoparticles are commonly found in certain federally-regulated industries, such as automotive and aerospace. They are found in coatings, sensors/detectors, catalysts, fuel cells, and more. Despite the applications of nanotechnology, the potential for human exposure remains a threat to employees’ health.

What are the health and safety considerations for nanoparticles?

Since there are many different types of nanoparticles, the health and safety concerns for each type must be considered on a case-by-case basis. However, research has shown that nanoparticle exposure can cause a host of adverse effects in multiple bodily systems. For example, nanoparticles have been shown to cause bronchitis, dermatitis, and hypertension. Nanoparticles are also assumed to have the same toxicological properties as their macro forms, including carcinogenicity for instance. Literature related to the health effects of nanoparticle exposure is burgeoning. It is expected that many more papers on this subject than currently exist will be published in the coming years. In the consideration of exposure-related health effects, the following factors should be evaluated: composition and properties of the nanoparticle, route of entry; extent of exposure (for example, duration, frequency, concentration – if the sampling and analytical methods are available, otherwise the control banding model may be an option); and effectiveness of control measures.

How do employees become exposed to nanoparticles?

Exposure takes place via four routes of entry, listed in order of most to least common:

- inhalation: breathing in air contaminated with nanoparticles

- dermal and eye absorption: nanoparticles penetrate through unprotected skin and eyes

- ingestion: unwittingly consuming food that has come into contact with nanoparticles

- injection: accidentally being pierced by sharp object(s) contaminated with nanoparticles

Researchers have found that certain work processes generate significant airborne concentrations of nanoparticles. These include: packaging, filtration, spraying and vacuum cleaning, and grinding.

How can exposure to nanoparticles be controlled?

To reduce employee exposures to nanoparticles, the following control measures can be applied:

- elimination of a hazardous chemical substance from the workplace

- substitution of the substance with another substance that is less toxic to health

- isolation of the substance in closed chambers or rooms

- engineering controls such as ventilation or design/process modification

- administrative controls such as shift rotation or access restriction

- personal protective equipment such as respiratory, eye, or skin protection

What are the legislative requirements related to nanoparticles?

Stipulations under the Canada Labour Code and Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations govern occupational exposure to hazardous chemical substances in federally-regulated workplaces. Specifically, Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations Part X dictates how hazardous chemical substances must be stored, handled, and used, along with how hazard investigations are to be conducted. Table A1 of the Engineered Nanoparticles: Health and Safety Considerations guideline contains a chart summarizing sections in Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations that are directly relevant to this subject. Importantly, laws under the Canada Labour Code, Part II, stipulate that it is the employer’s responsibility to appoint qualified persons to evaluate occupational exposure to hazardous chemical substances for the protection of employees’ health (including nanoparticles).

Summary

In conclusion, engineered nanoparticles are an emerging occupational hazard. Given that the rate at which nanomaterials are being produced far exceeds the rate at which occupational exposure limits are being developed, it is important to take a precautionary approach in dealing with nanoparticles in the workplace. The Canadian Standard Association published a comprehensive standard on the recommended practices relating to nanotechnologies (Canadian Standard Association Z-12885 Nanotechnologies), which may be a resource of interest for health and safety committees. The Engineered Nanoparticles: Health and Safety Considerations guideline by the Labour Program is consistent with the Canadian Standard Association’s Standard.

9.2 Appendix B

Sections of the Canada Labour Code and Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations made under the Canada Labour Code as relevant to nanoparticle risk assessment and management

Preventive measures – Canada Labour Code 122.2

Relevant statements: Preventive measures should consist first of the elimination of hazards, then the reduction of hazards and finally, the provision of personal protective equipment, devices or materials, all with the goal of ensuring the health and safety of employees.

Preventive measures – Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations 19.5(1)

Relevant statements: The employer shall, in order to address identified and assessed hazards, including ergonomics-related hazards, take preventive measures to address the assessed hazard in the following order of priority:

- (a) the elimination of the hazard, including by way of engineering controls which may involve mechanical aids, equipment design or redesign that take into account the physical attributes of the employee

- (b) the reduction of the hazard, including isolating it

- (c) the provision of personal protective equipment, clothing, devices or materials

- (d) administrative procedures such as the management of hazard exposures and recovery periods and the management of work patterns and methods

Substitution of substances – Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations 10.16

Relevant statements:

- (1) No person shall use a hazardous substance in a work place where it is reasonably practicable to substitute a substance for it that is not a hazardous substance

- (2) If the requirements of subsection 10.16(1) cannot be met, where a hazardous substance is to be used for any purpose in a work place and an equivalent substance that is less hazardous is available to be used for that purpose, the equivalent substance shall be substituted for the hazardous substance where reasonably practicable

Ventilation – Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations 10.17

Relevant statements:

(1) Every ventilation system installed on or after January 1, 1997 to control the concentration of an airborne hazardous substance shall be so designed, constructed, installed, operated and maintained that

- (a) the concentration of the airborne hazardous substance does not exceed the values and levels prescribed in subsections 10.19(1) and 10.20(1) and (2); and

- (b) it meets the standards set out in:

- (i) Part 6 of the National Building Code,

- (ii) the publication of the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists entitled Industrial Ventilation: A manual of Recommended Practice for Design, 26th edition, dated 2007, and Industrial Ventilation: A Manual of Recommended Practice for Operation and Maintenance, dated 2007, as amended from time to time

- (iii) American National Standards Institute’s Standard Z9.2-2006 entitled Fundamentals Governing the Design and Operation of Local Exhaust Systems, dated 2006, as amended from time to time

Control of hazards – Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations 10.19

Relevant statements:

(1) An employee shall be kept free from exposure to a concentration of (a) an airborne chemical agent in excess of the value for that chemical agent adopted by the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists, in its publication entitled Threshold limit values and Biological Exposure Indices, as amended from time to time

(3) Where there is a likelihood that the concentration of an airborne chemical agent may exceed the value referred to in subsection (1), air samples shall be taken and the concentration of the chemical agent shall be determined

- (b) in accordance with the standards set out by the United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health in the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Manual of Analytical Methods, third edition, volumes 1 and 2, as amended from time to time;

- (c) in accordance with a method that collects and analyses a representative sample of the chemical agent with accuracy and with detection levels at least equal to those which would be obtained if the standards referred to in paragraph (b) were used; or

- (d) where no specific standards for the chemical agent are set out in the publications referred to in paragraph (b) and no method is available under paragraph (c), in accordance with a scientifically proven method used to collect and analyse a representative sample of the chemical agent.

Notwithstanding subsection 10.19(1), the employer shall ensure that the employees’ exposure to those substances listed in American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists as known or suspected carcinogens, be kept as low as reasonably practicable.

Hazard investigation – Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations 10.4

Relevant statements

(1) If there is a likelihood that the health or safety of an employee in a work place is or may be endangered by exposure to a hazardous substance, the employer shall, without delay,

- (a) appoint a qualified person to carry out an investigation in that regard

- (b) for the purposes of providing for the participation of the work place committee or the health and safety representative in the investigation, notify either of the proposed investigation and of the name of the qualified person appointed to carry out that investigation

(2) In an investigation referred to in subsection (1), the following criteria shall be taken into consideration:

- (a) the chemical, biological and physical properties of the hazardous substance

- (b) the routes of exposure to the hazardous substance

- (c) the acute and chronic effects on health of exposure to the hazardous substance

- (d) the quantity of the hazardous substance to be handled

- (e) the manner in which the hazardous substance is stored, used, handled and disposed of

- (f) the control methods used to eliminate or reduce exposure of employees to the hazardous substance

- (g) the concentration or level of the hazardous substance to which an employee is likely to be exposed

- (h) whether the concentration of an airborne chemical agent or the level of ionizing or non-ionizing radiation is likely to exceed 50 per cent of the values referred to in subsection 10.19(1) or the levels referred to in subsections 10.26(3) and (4)

- (i) whether the level referred to in paragraph (g) is likely to exceed or be less than that prescribed in Part VI.

Hazard investigation – Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations 10.6

Relevant statements: A report referred to in section 10.5 shall be kept by the employer for a period of thirty years after the date on which the qualified person signed the report.

Nanoparticles – (to be determined)

Relevant statements:

Engineered nanomaterials – nanomaterial designed for a specific purpose or function

Incidental nanomaterials – nanomaterial generated as an unintentional by-product of a process

Where engineered nanomaterials are present in the workplace, the employer shall ensure a qualified person:

- establishes and maintains a process to identify and remove hazards, and mitigate risks associated with the handling, use and exposure to nanomaterials on an ongoing basis in accordance with Canadian Standard Association’s Standard Z-12885;

- sets objectives and targets to develop preventative and protective measures in accordance with Canadian Standard Association's Standard Z-12885.

Where a process produces an incidental nanomaterial as a by-product, the employer will conduct an investigation and implement controls as described under 10.4 through 10.6 of these regulations.

While the proposed requirements are not yet contained in the regulations, it is strongly recommended that work place parties follow these guidelines. Changes in policy reflect the need for clarification in wording [10.16(2)], the need for updates to conform to the latest industry standards [10.17(2b-ii)], the need to motivate employers to do their best in controlling chemical exposures [10.19], and the need to address the absence of regulations specifically pertaining to nanoparticle exposures [to be determined].

| Class | Description | Density | Nano reference values (8-hour time-weighted average) | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rogid, biopersistent nanofibers for which effects similar to those of asbestos are not excluded | Not available | 0.01 fibre centimetre-3 | single-walled carbon nanotube or multi-walled carbon nanotube or metal oxide fibres for which asbestos-like effects are not excluded |

| 2 | Biopersistent granular nanomaterials in the range of 1-100 nanometers | >6000 kilogram meter-3 | 20000 particles centimeter-3 | Silver, gold, cerium (IV) dioxide, cobalt (II) oxide, iron, iron oxides, lanthanum, lead, antimony pentoxide, tin dioxide |

| 3 | Biopersistent granular and fibre form nanomaterials in the range of 1-100 nanometers | <6000 kilogram meter-3 | 40000 particles centimeter-3 | Aluminum oxide, silicon dioxide, titanium nitride, titanium dioxide, zinc oxide, nanoclay carbon black, fullerene, dendrimers, polystyrene nanofibers with excluded asbestos-like affects |

| 4 | Non-biopersistent granular nanomaterials in the range of 1-100 nanometers | Not available | Applicable occupational exposure limit | Examples: fats, sodium chloride |

Figure B1 – Text version

Concerning human exposure for novel nanoparticles, the algorithm has been developed to determine whether in order to evaluate exposure, any additional testing is required.

If there is no exposure to nanoparticles, there are no additional testing requirements.

However, if there is a likelihood that human exposure to nanoparticles occurs or may occur, it may become necessary to meet some additional testing requirements in order to further assess exposure and recommend proper control measures to prevent employee exposure to nanoparticles.

Nanoparticles can enter the body via three major routes of entry: inhalation, ingestion (oral) and skin absorption (dermal). If the oral route of human exposure is determined, the solubility of nanoparticles (in biological milieu and dissolution at low pH) must be considered. If the solubility is considered low, the particle size and surface chemistry such as: 1) uptake of smaller particles is greater than for larger particles, and 2) the surface chemistry will affect uptake efficiency, additional testing is required. If high solubility is determined, it is necessary to find out whether there is sufficient information available on molecular or ionic dissociation/toxicity. If the information is not available, additional testing is required, if the information is sufficient – there are no additional testing requirements.

If the inhalation route of entry is determined, it is necessary to consider the particle shape. If the particle shape is a fibre, the aspect ratio must be determined. For the aspect ratio equal to or greater than 3:1, the fibre size and solubility must be considered, and if it is soluble and respiratory and systemic toxicity is determined, additional testing is required. Also, if the solubility is considered poor or it is insoluble (biopersistent), the main concerns evolve around pulmonary fibrosis, granulomas and cancer, and therefore, additional testing is required.

If the aspect ratio is less than 3:1, a particle size needs to be determined. For the particles greater than 2.5µm (microns), the oral route of human exposure must be followed to determine whether additional testing is required. For the particles equal to or less than 2.5µm (microns), the inhalation route must be followed and the solubility, as well as the surface considerations must be taken into account to determine additional testing requirements.

Finally, if the dermal route of nanoparticle entry is considered and it is likely or unknown of dermal absorption, additional testing is required. If the dermal absorption is unlikely – there are no additional testing requirements.

9.3 Appendix C

Figure C1 – Safety data sheet for titanium dioxide

Tronox safety data sheet for titanium dioxide, all grades

2835; Version no.: 01; Revision date: 22 December 2009; Print date: 22 December 2009