Improving the maintenance of activities process under the Canada Labour Code - Discussion paper

From: Employment and Social Development Canada

On this page

Introduction

The Government of Canada respects the right to strike, as protected by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. However, all governments also have a responsibility to make sure that strikes and lockouts do not risk the health and safety of the public. To protect the public, Governments make rules requiring employers and unions to continue providing certain essential services during strikes and lockouts. These are called maintenance of activities requirements.

Part I (Industrial Relations) of the Canada Labour Code (Code) has rules that require federally regulated employers and unions to continue any activities necessary to protect the public from immediate and serious danger, even though there is a strike or lockout. The Code also lays out a process for how to decide which activities need to continue. Unfortunately, the Government has heard that this process is not working smoothly, and may need to be updated.

To make sure that the Code continues to protect the public in the most efficient way possible, the Government is consulting interested Canadians and stakeholders on ways to improve this process.

Who would this affect?

Part I of the Code is the federal law that sets the rules for unionization, collective bargaining and labour disputes in federally regulated sectors. More specifically, Part I applies to:

- the federally regulated private sector, which includes key industries such as:

- banking

- telecommunications and broadcasting

- air, rail, and maritime transportation

- most Crown corporations (for example, Canada Post)

- certain activities (for example, governance and administration) of First Nations band councils and Indigenous self-governments, and

- other industries (see Annex A for a full list)

- all private sector businesses and municipal governments in the Northwest Territories, Nunavut and Yukon

In total, about 22,000 employers and about 985,000 employees are covered by Part I of the Code. Any change to Part I of the Code would apply to these employers and employees.

Purpose

The purpose of this discussion paper is to gather Canadians’ views on how to improve the process for protecting the health and safety of the public when there is a strike or lockout in a federally regulated sector. The discussion paper:

- describes the current rules in the Code and issues that stakeholders have identified with these rules

- outlines key discussion questions for stakeholder feedback

- invites all interested stakeholders to write to the Labour Program to express their views on the discussion questions

- supports virtual discussions with select stakeholders in November and December 2022

All interested Canadians and groups can provide comments on the discussion questions, or any other general comments they wish to make. By submitting your written feedback to this discussion paper, you are signalling that you consent to the privacy notice included as Annex B.

Please send your responses no later than January 31, 2023 to: ESDC.NC.LABOUR.CONSULTATIONS-TRAVAIL.NC.EDSC@labour-travail.gc.ca.

Context

How does collective bargaining work under the Code?

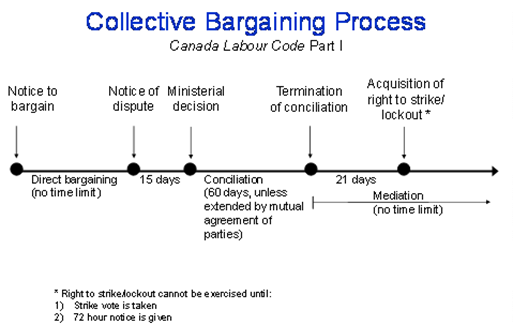

To understand the process for protecting the health and safety of the public, it is important to understand how collective bargaining works under Part I of the Code. Figure 1 outlines the key steps involved in the collective bargaining process, and introduces some key terms.

Figure 1 - Text version

An arrow from left to right shows the key steps in the collective bargaining process under Part I of the Canada Labour Code:

- Step 1: Notice to bargain

- Step 2: Notice of dispute

- Between Step 1 and Step 2: Direct bargaining (no time limit)

- Step 3: Ministerial decision

- Between Step 2 and Step 3: 15 days

- Step 4: Termination of conciliation

- Between Step 3 and Step 4: Conciliation (60 days, unless extended by mutual agreement of parties)

- After Step 4: Mediation (no time limit)

- Step 5: Acquisition of right to strike/lockout*

- Between Step 4 and Step 5: 21 days

- Note for Step 5:

- *Right to strike/lockout cannot be exercised until:

- Strike vote is taken

- 72 hour notice is given

Source: “Collective Bargaining - Labour Program,” Employment and Social Development Canada, 2019 (Collective Bargaining - Canada.ca).

In Figure 1, the term “ministerial decision” indicates the time period where the Minister can appoint a conciliation officer to help the parties. For more information on the collective bargaining process under the Code, please see: Collective Bargaining - Labour Program.

How does the Code protect the public?

Part I of the Code requires employers and unions to continue any activities that are necessary to prevent an immediate and serious danger to the health and safety of the public, whenever there is a strike or lockout. The key steps and timelines in this process are below.

Within 15 Days of Notice to Bargain: parties discuss

If an employer or a union believes that any activities need to continue, they must notify the other party within 15 days of starting to bargain. The parties discuss the notice and, if they agree, they can enter into a maintenance of activities agreement at any time. The agreement will state what activities they agree to continue, and how they will continue them. On the other hand, sometimes the employer and union will agree they do not need to maintain any activities during a work stoppage.

The employer or the union can file their agreement with the Canada Industrial Relations Board (CIRB). If they do, it has the same power as an order from the CIRB.

Within 15 Days of Notice of Dispute: application to the Canada Industrial Relations Board

If the parties cannot agree, the employer or the union can ask the CIRB to decide what activities they need to maintain. They have to submit this within 15 days of when the employer or the union filed notice of dispute. If they miss this deadline, they can no longer ask the CIRB to step in.

The parties are banned from beginning a strike or lockout until the CIRB makes a decision.

Anytime after Notice of Dispute: referral from the Minister of Labour

The Minister of Labour can also play a role. They can ask the CIRB to intervene to decide what activities need to continue during a strike or lockout, even if the parties have a maintenance of activities agreement. The Minister can do this at any point after the employer or union gives notice of dispute, even after a strike or lockout begins.

If the Minister goes to the CIRB before there is a strike or lockout, the parties are banned from beginning a strike or lockout until the CIRB makes a decision. If the Minister goes to the CIRB after a strike or lockout has started, it can continue while the CIRB investigates.

Role of the Canada Industrial Relations Board

When it receives an application from an employer or a union, or a referral from the Minister of Labour, the CIRB will investigate. If it decides that some activities need to continue, it can make an order listing those activities and providing any details on how they should continue if there is a strike or lockout.

Sometimes, an employer and union need to maintain so many activities that it can seriously limit their right to strike or lockout. When this happens, the CIRB can order that the parties resolve their disputes in another way, like binding arbitration.

How often are these provisions used?

All federally regulated employers and unions must make sure that a strike or lockout will not cause an immediate threat to the health and safety of the public. However, the requirements will affect different workplaces differently. This depends on the work they do and how much it affects the public. Some employers will provide critical services and continue most of their activities during a strike or lockout, while others might not need to continue any at all.

There is a data gap in this area. Under the Code, unions and employers are not required to submit their maintenance of activity agreements to any outside body. As a result, the Government cannot know what percentage of federally regulated workplaces have maintenance of activities agreements in place, or what those agreements contain.

Fortunately, the CIRB publishes data on the number of maintenance of activities questions it handles each year. This indicates how often there is a dispute about the maintenance of activities requirements. See Table 1.

| Fiscal year | 2021 to 2022 | 2020 to 2021 | 2019 to 2020 | 2018 to 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of Maintenance of Activity Matters | 3 | 6 | 18 | 31 |

Source: “Average Processing and Decision-Making Times (Days) by Type of Matter” Canada Industrial Relations Board, 2022 (Resources - Canada Industrial Relations Board (cirb-ccri.gc.ca).

These statistics show that the number of maintenance of activities questions handled by the CIRB changes significantly depending on the year. Note that the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to have caused the low number of matters in 2021 to 2022 and 2020 to 2021.

Issues

Stakeholders have criticised the current maintenance of activities process. These criticisms can be grouped into 3 main categories.

No verification of maintenance of activities agreements

The current maintenance of activities process makes employers and unions responsible for protecting the health and safety of the public during a strike or lockout. There is no requirement for the CIRB, or any other third party to review or validate the agreement. The Government has heard that:

- putting the onus on employers and unions to protect public safety may be problematic, since they are focused on getting a deal – protecting the public may not be treated as seriously

- the Government or another third party could make sure the public is protected, for instance by verifying maintenance of activity agreements

Provincial approach

In Quebec, the Tribunal administratif du travail must approve all essential services agreements or lists before any work stoppage can begin. However, only certain industries (for example, healthcare) are required to create these agreements or lists.

Time for decision by the Canada Industrial Relations Board

The Government has heard that it takes too long for the CIRB to process and decide maintenance of activities questions. Stakeholders say these delays interrupt collective bargaining, and can hurt the relationship between the parties.

CIRB performance statistics (see Table 2) and recent case studies support this. For example, during a recent high-profile labour dispute, it took nearly 600 days for the CIRB to reach a decision. However, the CIRB itself is not necessarily responsible for the long delays in reaching a decision. It is required to follow strict procedures to ensure fairness. Stakeholders have said that employers can exploit these processes to slow the process down and delay employees’ right to strike.

| Fiscal Year | Number of matters | Average processing time (days) | Average decision time (days) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 to 2022 | 3 | 78 | Not applicable |

| 2020 to 2021 | 6 | 212 | 17 |

| 2019 to 2020 | 18 | 126 | 1 |

| 2018 to 2019 | 31 | 201 | 2 |

Source: “Average Processing and Decision-Making Times (Days) by Type of Matter” Canada Industrial Relations Board, 2022 (Resources - Canada Industrial Relations Board (cirb-ccri.gc.ca).

Note: 2021 to 2022 data suggests that all maintenance of activities matters were resolved or abandoned before the CIRB issued a decision.

In response to these delays, stakeholders have called on the Government to find a way to expedite the CIRB’s process.

Provincial approach

In Alberta, a vice-chair of the Alberta Labour Relations Board is designated as the Essential Services Commissioner and given extensive powers to decide questions related to essential services in the province.

Involvement of the Minister of Labour

Stakeholders have also said that the current process relies too much on the Minister of Labour to step in and refer questions to the CIRB. As discussed above, the union and employer have 2 strict deadlines they have to respect. If they miss either of these deadlines, they cannot go to the CIRB to resolve a dispute.

On the other hand, the Minister of Labour has the power to refer a question to the CIRB at any time after notice of dispute has been given. As a result, sometimes stakeholders will try to convince the Minister to intervene and refer a dispute to the CIRB because the parties have missed their deadlines under the Code. This can give the appearance of bias and increase tensions at the bargaining table.

Discussion questions

General

- In your opinion, is the current maintenance of activities processworking? Why or why not?

- What sectors are most affected by the current maintenance of activities process?

- What are some ways that the Government could improve the current maintenance of activities process?

Issue 1 – third party verification

- Should the Government require employers and unions to submit their maintenance of activities agreement to the CIRB or another third party for review?

- If so, how should this review happen? Should there be a time limit?

- If not, why not?

- Should all employers and unions be required to have verified maintenance of activities agreements before they can start a strike or lockout? Why or why not?

- If not, are there certain industries where this should be required?

- How long should a verified maintenance of activities agreement be valid?

Issue 2 – processing times

- In your opinion, are long processing times for maintenance of activities questions a problem?

- How could the Government shorten the time it takes to get a decision on maintenance of activities questions?

- Should the Government create a new body dedicated to resolving maintenance of activities issues? For instance, the new body could be division of the CIRB with dedicated resources. It could focus on:

- Certifying maintenance of activities agreements

- Resolving disputes about which activities need to continue during a strike or lockout, as quickly as possible

- What impacts, positive or negative, do you think a new maintenance of activities body could have?

- How can the Government make sure that the new body can reach decisions quickly?

Issue 3 – Minister of Labour’s involvement

- Is the Minister of Labour’s role in the maintenance of activities an issue?

- What role should the Minister of Labour have in the maintenance of activities process?

Annex A – Federally regulated private sector

The federally regulated private sector includes:

- air transportation, including airlines, airports, aerodromes and aircraft operations

- banks, including authorized foreign banks

- grain elevators, feed and seed mills, feed warehouses and grain-seed cleaning plants

- First Nations band councils (including certain community services on reserve)

- most federal Crown corporations, for example Canada Post Corporation

- port services, marine shipping, ferries, tunnels, canals, bridges and pipelines (oil and gas) that cross international or provincial borders

- radio and television broadcasting

- railways that cross provincial or international borders and some short-line railways

- road transportation services, including trucks and buses, that cross provincial or international borders

- telecommunications, such as telephone, Internet, telegraph and cable systems

- uranium mining and processing and atomic energy

- any business that is vital, essential or integral to the operation of one of the above activities

Annex B – Privacy notice statement for submissions

The submission you provide as part of this consultation is collected under the authority of the Department of Employment and Social Development Act (DESDA). It may be used and disclosed by Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), including the Labour Program, for policy analysis, research and evaluation purposes. However, these additional uses and/or disclosures of your personal information will never result in an administrative decision being made about you.

Participation in this stakeholder engagement process is voluntary, and acceptance or refusal to participate will in no way affect any relationship with ESDC or the Government of Canada.

Your submission may be published – in whole or in part – on canada.ca, included in publicly available reports on the consultation, and/or compiled with other responses in an open-data submission on open.canada.ca. It may be shared throughout the Government of Canada, other levels of government, and non-governmental third parties.

Your personal information is administered in accordance with DESDA, the Privacy Act, and other applicable laws. If you are not satisfied with our response to your privacy, you have the right to the protection of, access to, and correction of your personal information, which is described in the Personal Information Bank ‘Outreach Activities’ [PSU 938]. Instructions for obtaining this information are outlined in the government publication titled, Information about Programs and Information Holdings. Information about Programs and Information Holdings may also be accessed online at any Service Canada Centre.

If you are not satisfied with our response to your privacy, you have the right to file a complaint with the Privacy Commissioner of Canada regarding ESDC’s handling of your personal information at: https://www.priv.gc.ca/en/report-a-concern.

If your submission includes unsolicited personal information for the purpose of attribution (for example, name, position), ESDC may choose to include this information in publicly available reports on the consultation and elsewhere.

I understand that by providing a submission to ESDC as part of this consultation process, I am consenting to its publication and dissemination.

Name (Please Print)

Organization (Please Print)

Signature

Date (dd/mm/yyyy)