Key Issues (continued 2)

Note

This information was current as of November 2015.

Table of Contents

- Chemicals Management Plan

- Meteorological Services

- The Federal Sustainable Development Strategy

- Enforcement

- Scientific Monitoring and Research

- Environmental Emergencies

Chemicals Management Plan

What is the issue?

Chemical substances are the building blocks of many commodities, as well as commercial and consumer goods. However, chemicals, pollution, and waste may exert a direct or indirect harmful effect on animals, plants, or humans, and may pose long-term risks to the environment. The Chemicals Management Plan (CMP) is a joint Environment Canada (EC) and Health Canada (HC) program that addresses the threats from chemical substances of concern.

The Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA 1999) enables EC and HC to protect the environment and human health from risks posed by chemical substances, including those new to Canada since 1987 (new substances), as well as the 23,000 legacy chemicals that were in use prior to 1987 (existing substances).

In order to import or manufacture a new substance in Canada, a company needs to notify the Government so the substance can be assessed. EC annually assesses approximately 500 notifications of new substances prior to their introduction into the Canadian marketplace, and issues approximately two dozen restrictions to ensure that they are used in a manner that minimizes risk to health and the environment.

In 2006, the Government completed a triage of 23,000 chemical substances that are already in commercial use and identified 4,300 existing substances for further attention by 2020. To date, approximately 2,700 existing substances have been reviewed by government scientists. Since then, 360 substances, included in 97 substances or groups of substances have been identified as harmful to health or the environment underCEPA 1999, and 61 risk management instruments have been finalized. Risk management action has been, or continues to be, developed for approximately 360 of the 2,700 individual substances.

The program interacts with numerous industry associations, including, but not limited to: the Chemical Industry Association of Canada; Canadian Vehicle Manufacturing Association; Canadian Fuels Association; Canadian Cosmetics, Toiletries, and Fragrance Association; Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters; and the Canadian Consumer Specialty Products Association. In addition, Environmental non-government organizations such as Pollution Probe, Environmental Defense, the Canadian Environmental Network, and the Canadian Environmental Law Association are heavily engaged in the process. Several Aboriginal groups are also involved, including the Assembly of First Nations, Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, and the Métis National Council, among others.

The first phase of the CMP allocated $107 million for EC and $193 million for HC over four years. That funding expired at the end of 2010-2011. Building upon success and lessons learned from CMP phase 1, CMP phase 2 was announced on October 3, 2011, with funding over five years of $147.5 million for EC and $359.2 million for HC. The CMP was renewed for a third phase in April 2015 and received $491.8 million in funding to continue to assess and manage the risks to human health and the environment from new and existing chemical substances.

Why is it important?

At the 2002 United Nations World Summit on Sustainable Development, Canada joined other developed countries in committing to achieve the “sound management of chemicals” by 2020. The CMP, launched in 2006, is Canada’s plan to attain this objective domestically.

The assessment and management of harmful chemicals has long been an important component of EC’s mandate. Substances such as lead, mercury, and polychlorinated biphenyls have been controlled through a variety of regulations and other risk management instruments for many years. Recently, assessment and management action has been taken on flame retardants, Bisphenol A, and perfluorinated compounds.

With the CMP, the Government continues to:

- take rapid action on new and existing chemicals;

- integrate chemical management activities across the government; and

- provide predictability for business and engender public trust through transparent work plans.

Environment Canada’s role

CEPA 1999 requires that the Ministers of the Environment and Health protect Canadians and the environment from risks posed by chemicals in Canada.

In addition to the activities outlined above to assess and manage chemical substances, work is in progress under the CMP to identify and address challenges emerging from the development and increasing use of biotechnologies and nanomaterials.

Along with regulations, EC utilizes a variety of other instruments to risk manage substances of concern, including Pollution Prevention Plans, Environmental Performance Agreements, and Codes of Practice.

EC is also responsible for regulating transboundary movements of hazardous wastes. Regulations under CEPA 1999 set conditions that must be met prior to their movement across national or provincial borders. EC issues over 4,000 permits per year to authorize more than 35,000 transboundary movements of hazardous wastes.

EC also plays a key role in international chemicals management. Often, international sources of harmful releases may be a major source of pollutants in Canada. For example, over 95% of mercury deposited in Canada is from international sources. The Department played a key role in negotiating the Minamata Convention, which is a legally binding international agreement to reduce mercury emissions.

Finally, by leading research and monitoring, as well as partnering with external research bodies, the Government is working to ensure that the wide range of chemicals management decisions made by all levels of government, Canadians, and industry, are informed by the best available science.

Meteorological Services

What is the issue?

Environment Canada is an important provider of weather and meteorological information. Every year, it issues an average of 1.5 million public forecasts, 15,000 severe weather warnings, 500,000 aviation forecasts, and 200,000 marine, ice and sea-state forecasts.

Why is it important?

Environment Canada provides Canadians with the information they need to make informed decisions to protect their health, safety, and economic well-being in the face of changing weather and environmental conditions. In Canada, weather-related events account for 80% of disasters, with significant consequences for the health and safety of citizens and Canada’s economic performance. There are increasingly frequent and severe weather events as a result of a changing climate, which are putting society at risk. This vulnerability is exacerbated as society becomes more dependent on weather-sensitive built infrastructure.

Canadians also need to understand the impacts of these events on their health, safety, and economic well-being. There is a growing expectation to receive information through modern communication channels, including wireless devices and social media. The department has been proactive in this regard, with the recent launch of real-time weather alerts via Twitter. This new system, serving over 830 communities across the country, is the first of its kind in the world.

Environment Canada’s role

Mandate

The Department of the Environment Act gives the Minister federal legislative authority for matters relating to meteorology, water, and boundary waters, which have not been designated to other departments. The Minister also has responsibilities related to the Canada Water Act, the International Boundary Waters Treaty Act, the International River Improvements Act, the Emergency Management Act, and the Weather Modification Information Act pertaining to meteorological services.

For over 140 years, the Meteorological Service of Canada (MSC) has been providing Canadians with information on weather, water, climate, ice, and air quality. Media outlets run weather reports on a daily basis, and that coverage increases in the face of severe events, such as hurricanes, tornados, and floods. The MSC possesses a unique capability and responsibility to warn Canadians about impending high-impact weather.

Further to this public good mission, the MSC supports other federal, provincial, and private institutions that rely on its infrastructure, science capacity, knowledge, and experience to deliver their services.

- The MSC provides government-wide services that other federal departments trust and depend on, particularly when it comes to exercising Canada’s sovereignty and protecting the safety and security of its citizens. Examples include:

- weather forecasts and information to the Department of National Defence operations in support of sovereignty at home and abroad;

- sea-ice forecasts to the Canadian Coast Guard in support of safe marine navigation in ice-filled waters;

- aviation weather services to NAV CANADA in support of safe air navigation operations (including provision of warnings to aviation operations when volcanic ash is released into the atmosphere);

- forecasts and alerts of poor air quality, alerts of the spread of nuclear radiation, and airborne disease vectors for Health Canada; and

- forecasts that support public safety responses to environmental emergencies (spread of chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear material).

- As the unique, national entity responsible for the management of meteorological and hydrological information, the MSC supports the mandates of provinces and territories in the areas of transportation, environment, health, energy, air quality, water resources, agriculture, and resource management. Weather and environmental services are also critical to decision making on disaster management and emergency response at the provincial, territorial, and municipal levels.

- The MSC has been instrumental in supporting weather-sensitive economic sectors—including transportation, energy, construction, agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and outdoor recreation and tourism—contributing to their productivity and competitiveness.

International dimensions

As Canada is a signatory to the conventions for the World Meteorological Organization and the International Maritime Organization, and various bilateral international agreements, EC has a mandate to share high quality weather, water, and climate information in real time, including for international Arctic waters under Canadian responsibility (north of Alaska and along part of the western coast of Greenland). In return, Canada gains access to global data and is able to leverage global investments in Earth system monitoring and science activities without which the MSC would not be able to forecast conditions beyond one to two days.

The MSC also represents Canada in the Group on Earth Observations, a voluntary intergovernmental partnership of governments and international organizations that seek to implement the Global Earth Observation System of Systems to allow free and open access to Earth observations in all countries. In addition, the MSC provides expert advice for domestic and international water boards, including International Joint Commission boards, and administers the International River Improvements Act, which provides for the licencing of activities that may alter the flow of rivers flowing from Canada to the United States.

The Federal Sustainable Development Strategy

What is the issue?

The Federal Sustainable Development Strategy (FSDS) articulates Canada’s federal sustainable development priorities for a period of three years, as required by the Federal Sustainable Development Act (the Act). The Minister of the Environment leads the development of the FSDS, and is also responsible for producing a departmental strategy that identifies Environment Canada (EC)’s contributions to the federal goals and targets. The first FSDS (2010-2013) was tabled on October 6, 2010, and the second Strategy was tabled in November 2013. To meet the timelines set out in the Act, the next FSDS (2016-2019) must be tabled by June 26, 2016, or if the House is not sitting, on any of the first 15 days on which the House is sitting after the Minister receives it.

Why is it important?

Between 1997 and 2006, the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development conducted 11 audits of the previous federal approach to sustainable development where the federal government was criticized for a lack of central leadership, insufficient tracking and coordination, and inadequate follow-up.

The FSDS was established to improve federal sustainable development planning and reporting and is a meaningful addition to results-based public management. The Strategy provides a comprehensive picture of what the Government is doing to address climate change and air quality, maintain water quality and availability, protect nature and Canadians, and to reduce the environmental impact of government operations. The FSDS updates federal environmental sustainability objectives and aligns them with current policies and priorities.

The 2016-2019 FSDS could be released, the first time, in an interactive online format that will enable Canadians to explore the Strategy and find what matters most to them. It will also provide a more complete whole-of-government picture of federal government environmental sustainability actions undertaken by more than 35 federal departments, agencies, and Crown corporations, and will continue to recognize and develop strong linkages between a clean and sustainable environment, human health, and economic prosperity.

Through integrating FSDS goals and targets into the strategic environmental assessment process, the Strategy also helps ensure that the Government’s environmental sustainability priorities are taken into account when pursuing social, economic, and environmental objectives.

The Strategy brings together and makes visible federal environmental sustainability goals, targets, and implementation strategies (specific actions to achieve the targets) that have been created through the normal course of government decision making. Improvements expected for the third cycle include more information on the health and economic dimensions of sustainable development, the addition of three new targets related to mining, connecting Canadians to nature, and protecting coastal ecosystems, as well as a more user-friendly electronic version of the Strategy that will make it easier for Canadians to find information that interests them. In addition, Theme IV of the FSDS, “Shrinking the Environmental Footprint – Beginning with Government,” has streamlined three targets to create a new target focused on sustainable workplace operations. The 2016-2019 FSDS is expected to include eight goals, 34 targets, and approximately 233 implementation strategies.

The Canadian Environmental Sustainability Indicators (CESI)

Launched in 2004, the indicators inform policy and decision making by providing credible scientific data in areas such as air quality and pollution, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, water availability and quality, and nature. The indicators are prepared by EC with the support of other federal departments, including Health Canada, Statistics Canada, Natural Resources Canada, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada, as well as relevant provincial and territorial counterparts.

CESI has been identified as the prime vehicle to measure progress towards the goals and targets of Themes I to III of the FSDS through both headline and target indicators. Consequently, the CESI program has been significantly expanded and now provides information to measure the progress towards the majority of the goals and targets of the FSDS. With each new cycle of the FSDS, the related indicators are updated and improved with the latest information available. See Annex 1 for more information.

FSDS Progress Reports

The Act requires that the Minister table in Parliament a report on the progress of the federal government in implementing the FSDS at least once every three years. The first progress report, published in 2011, focused on progress made in setting up the management framework for the FSDS. The second, published in February 2013, highlighted the progress of 27 departments and agencies towards the goals and targets set out in the 2010-2013 FSDS. It provided parliamentarians and Canadians with a whole‑of‑government picture of the contributions of the federal government to environmental sustainability. The 2015 Progress report builds on this foundation and presents the progress made under the 2013-2016 FSDS. This 2015 report is currently being finalized with a view to being ready for tabling in Parliament in early winter 2015-2016 to support the launch of the public consultations for the 2016-2019 FSDS.

Greening Government Operations

Led by Public Works and Government Services Canada, Theme IV of the FSDS contains goals and targets for Greening Government Operations (e.g., green buildings, GHG emissions, electronic waste, printing units, paper consumption, green meetings, and green procurement). The Government has been committed to reducing levels of GHG emissions from its federal operations to match the national target of 17% below 2005 by 2020. EC, as a department, reported a 2.9% reduction in GHG emissions relative to base year 2005 in its Departmental Sustainable Development Strategy 2013-2014. EC has committed to reduce to 18.8 kt CO2 equivalent by 2020-2021 (a 17% reduction from 2005 levels).

The FSDS and Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA)

The 2010-2013 FSDS included a commitment to strengthen the application of Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA), a tool that contributes to informed decisions in support of sustainable development by incorporating environmental considerations into the development of public policies and strategic decisions. This is reflected in the parallel release of revised Guidelines to implement the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan, and Program proposals (Guidelines) by the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency. The revised Guidelines strengthen language to improve integration of environmental considerations in federal decision-making and require departments and agencies to consider the potential effects of proposed policies, plans, and programs on the FSDS goals and targets.

Environment Canada’s role

Under the Act, the Minister of the Environment is responsible for developing the FSDS and establishing a Sustainable Development Office (SDO) to monitor progress on implementing the FSDS. The SDO, which is located within EC, reaches out across government and to international agencies and stakeholders to build awareness of the FSDS and its contribution to progress on sustainable development. It also provides overall leadership and coordination on matters related to the FSDS.

Federal-provincial-territorial dimensions

The FSDS has no direct implications for provinces and territories or for federal-provincial-territorial (FPT) relations. The Department does, however, work with provincial, territorial, and municipal governments in many areas of mutual interest. This has influenced the current FSDS and will continue to influence future strategies. Some FSDS implementation strategies reflect areas of significant federal‑provincial cooperation, such as the Great Lakes. During the 120-day public consultation on the FSDS 2016-2019, the Deputy Minister may be asked to send announcements to his FPT counterparts encouraging them to provide comments on the draft FSDS.

International dimensions

The FSDS is based on international best practices and responds to a long-standing international commitment to prepare a federal sustainable development strategy. The FSDS is used in a number of ways to reflect Canada’s domestic priorities in its international activities by contributing to Canada’s preparations for the United Nations Post-2015 Development Agenda, informing and strengthening Canada’s preparations for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s upcoming third Environmental Performance Review of Canada, and informing Canada’s position in trade negotiations with the European Union.

Short-term decisions and issues

Tabling the 2015 FSDS Progress Report and launching the public consultations for the 2016-2019 FSDS

The Act requires that a progress report be tabled in Parliament at least once every three years. Ideally this report should be tabled at the same time as the launch of the Consultation Draft of the FSDS in order to inform and support the 120-day public consultation period. During the consultation period, comments are expected from legislated stakeholders, including the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, the Sustainable Development Advisory Council (a multi-stakeholder ministerial body appointed by the Minister and required by the Act), and other stakeholders and members of the public. The 2016-2019 FSDS is currently in interdepartmental approvals, preparing for a potential release in the late fall 2015 or early winter 2016.

Annex 1 – Canadian Environmental Sustainability Indicators program

The Canadian Environmental Sustainability Indicators (CESI) program was developed to ensure environmental indicator information is communicated to Canadians in a transparent and straightforward manner. Through the establishment of a platform that develops and reports state of the environment indicators and data, CESI provides timely, comprehensive, unbiased and authoritative information on key environmental issues in a readily accessible and interactive web-based format.

Key features of the CESI platform include:

- national and sub-national level information

- interactive maps that allow drilling down to local level results

- information in an understandable format for Canadians;

- access to the detailed data, methodological approaches and source of information for researchers;

- rigorous methodology that standardizes the data and makes it comparable over time; and

- linkages to related socio-economic issues and information.

The indicators are prepared with the support of other federal departments, such as Health Canada, Statistics Canada, Natural Resources Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and relevant provincial and territorial counterparts. Through close collaboration with science and data experts across the federal government, CESI provides results and information on key issues including air and water quality, toxic substances, and exposure to substances of concern. Environment Canada regularly updates the CESI website as new data become available.

In short, CESI’s concise and accessible environmental indicators are delivered with direct public access to their underlying data sources and methods. CESI also publishes and maintains several interactive indicator maps, allowing visitors to explore data at the local level.

Currently, key indicators include:

Ambient Levels of Air Pollutants

Tracks important air pollutants with demonstrated health impacts, including fine particulate matter.

Long description

The line chart shows the average and peak (98th percentile) 24-hour concentrations of fine particulate matter in the air in Canada from 2000 to 2012. It also shows the 2015 Canadian Air Ambient Quality Standards, the 24-hour standard (28 micrograms per cubic metre) for peak and the annual standard (10 micrograms per cubic metre) for the average. In 2012, the annual average concentration of fine particulate matter in outdoor air in Canada was 6.3 micrograms per cubic metre, 7% lower than in 2011. The annual peak concentration of fine particulate matter in 2012 was 18.8 micrograms per cubic metre, or 14% lower than in 2011, one of the lowest levels reported since 2000. Between 2000 and 2012, both indicators were below the 2015 standards for all years, and no statistically significant increasing or decreasing trend was detected.

In 2012, the annual average concentration of fine particulate matter in outdoor air in Canada was 6.3 micrograms per cubic metre (µg/m3), 7% lower than in 2011. The annual peak (98th percentile) 24-hours concentration in 2012 was 18.8 µg/m3, one of the lowest levels reported since 2000. Some of the factors that may have contributed to the concentration changes between 2011 and 2012 include variations in weather conditions that influence PM2.5 formation, dispersion and regional transport; a reduction in emissions that contribute to particulate matter pollution in Canada; a decrease in transboundary pollution from the United States; and a decrease in the number of forest fires.

Freshwater Quality in Canadian Rivers

Provide an overall measure of the ability of select rivers across Canada to support aquatic life. It integrates multiple pressures from human activity upstream of water quality monitoring sites to present freshwater quality in the region where the majority of Canadians live.

Long description

The bar graph presents freshwater quality ratings in rivers selected to be representative of the regions of Canada where human activities are most concentrated for the 2010 to 2012 period. The bars show the number of sites where freshwater quality was rated poor (3), marginal (27), fair (64), good (69) and excellent (9).Ratings are based on data from 172 monitoring sites.

For the 2010 to 2012 period, freshwater quality in Canadian rivers where human activities are most concentrated was rated excellent or good at 45 percent of monitoring sites, fair at 37 percent of sites, marginal at 16 percent of sites, and poor at two percent of sites.

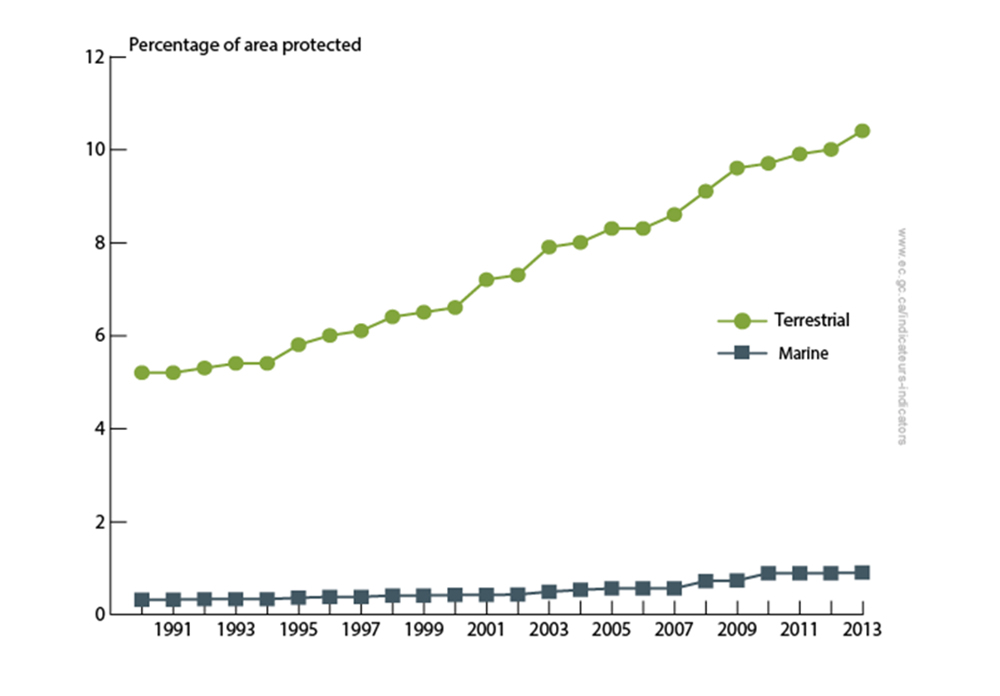

Canada’s Protected Areas

Tracks the percent of Canada’s terrestrial and marine territory that is protected in Canada.

Long description

The upper line of the graph shows the percentage of terrestrial area that has been recognized as protected in Canada between 1990 and 2013. The lower line of the graph shows the percentage of marine area protected between 1990 and 2013. As of 2013, 10.4% (1,036,645 square kilometres) of Canada’s terrestrial (land and freshwater) area, and about 0.9% (51,485 square kilometres) of its marine territory have been recognized as protected. In the last 20 years, the total area protected has nearly doubled, and in the last five years it has increased by 15%.

The number of areas and the total area protected in Canada continue to grow. As of the end of 2013, 10.4% (1,036,645 km2) of Canada’s terrestrial area (land and freshwater), and about 0.9% (51,485 km2) of its marine territory have been recognized as protected. In the past 20 years, the total area protected has nearly doubled, and in the last five years it has increased by 15%. In 2013, federal jurisdictions protected 525,398 km2 of territory, a 48% increase in the past 20 years.

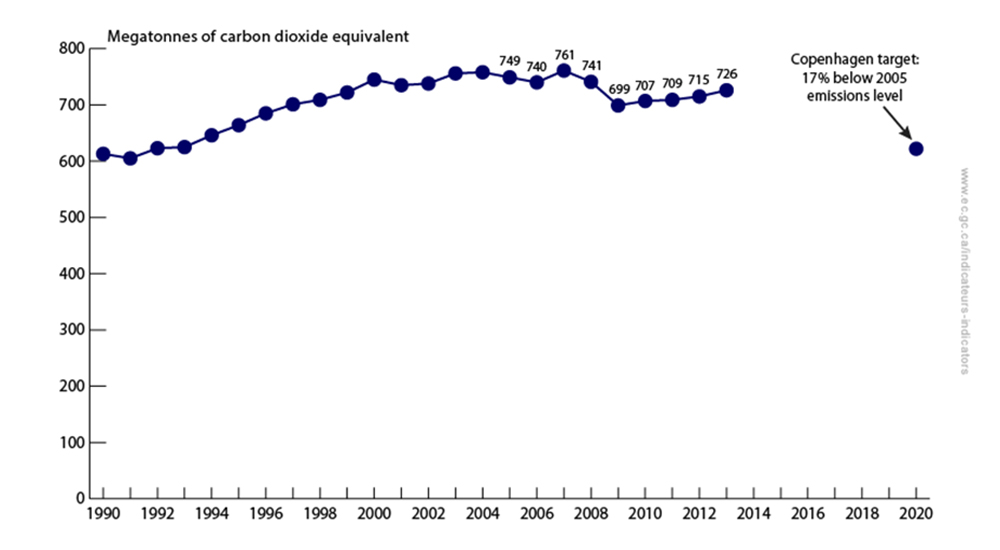

Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Tracks Canada’s GHG emissions, as per Canada’s National Inventory reports submitted to UNFCCC.

Long description

The line graph shows Canada's national greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 to 2013 with the 2020 Copenhagen target.

Canada's total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2013 were 726 megatonnes (Mt) of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2 eq), or 18% (113 Mt) above the 1990 emissions of 613 Mt. Steady increases in annual emissions characterized the first 15 years of this period, followed by fluctuating emission levels between 2005 and 2008, a steep decline in 2009, and a slight increase thereafter. Canada's emissions growth between 1990 and 2013 was driven primarily by increased emissions from the fossil fuel industries and transport. Emission reductions from 2005 to 2013 were driven primarily by reduced emissions from the public electricity and heat production category.

The indicators are available on Environment Canada's website.

Enforcement

What is the issue?

Environment Canada (EC) is responsible for the enforcement of all legislation and regulations respecting pollution and the protection of wildlife and habitat administered by the department. In fiscal year 2014-2015, the department conducted approximately 13,315 inspections and 566 investigations.

Why is it important?

Enforcement is an essential component of the regulatory-compliance continuum. The Enforcement program plays a crucial role in ensuring that regulatory instruments enacted by the Government are implemented fairly, consistently, and predictably.

Enforcement works closely with the drafters and administrators of instruments, compliance promotion staff, and personnel with scientific expertise, to support the implementation of compliance instruments administered by EC.

Environment Canada’s role

EC is responsible for the enforcement of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, the pollution prevention provisions of the Fisheries Act, the Canada Wildlife Act, the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994, the Species at Risk Act, the Wild Animal and Plant and Regulation of International and Interprovincial Trade Act, and the Antarctic Environmental Protection Act. The department conducts inspections and investigations that are supported by intelligence, and works in close collaboration with other government departments (such as Canada Border Services Agency, Department of Fisheries and Oceans), provincial governments, and numerous international partners (INTERPOL, the Commission for Environmental Cooperation, United States (U.S.) Environmental Protection Agency). EC also works closely with the Public Prosecution Service of Canada (or provincial attorneys general for minor cases), which is responsible for prosecuting alleged offenders.

EC’s 288 designated enforcement officers work in 34 regional offices across Canada. These officers have peace officer powers (including powers of arrest, detention, and seizure), go through extensive operational and safety training (wildlife officers carry sidearms), undertake investigations, and apply enforcement measures.

Federal-provincial-territorial / international dimensions

EC regularly collaborates with provincial and international enforcement agencies (e.g., U.S. EPA, INTERPOL, etc.) at both operational and strategic levels.

Short-term decisions and issues

Common Law dictates that decisions concerning the initiation of an investigation or the carrying out of an enforcement action are within the sole discretion of the enforcement officer and the enforcement chain of command. The enforcement function is independent from influence in carrying out inspections, investigations, or actions to deal with alleged violations. The Minister will occasionally be briefed on certain enforcement operations as they unfold.

Scientific Monitoring and Research

What is the issue?

Environment Canada (EC) is a science-based department. Its science provides critical information needed to support EC’s regulatory, policy, program, and service-delivery responsibilities. For example, EC has chemists and toxicologists working in the Chemicals Management Plan program to understand the environmental impacts of chemicals. Ecologists and hydrologists work on the Great Lakes Action Plan, and on other water issues. Scientists support weather forecasting and climate change modelling.

Why is it important?

As environmental issues continue to emerge, evolve, and increase in complexity, science is increasingly important.

Environment Canada’s role

The Department’s science spans a range of activities, such as short- and long-term monitoring and surveillance, research and development, modelling, risk assessment, reporting, and client-driven applications. EC conducts scientific monitoring and research in key environmental disciplines, including meteorology, atmospheric science, hydrology, biology, chemistry, toxicology, and ecology, to enable delivery of its mandate. Activities range from weather prediction, monitoring of water quality/quantity, contaminants, and air quality, to the management and conservation of species. EC’s science directly fulfills responsibilities under legislation such as the Department of the Environment Act, the Species at Risk Act, the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994, and the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, as well as supports the department’s regulatory authorities, such as those under the Fisheries Act. The Department’s environmental monitoring data is used extensively by other jurisdictions in Canada, in private sector organizations, and throughout the wider academic science community.

Monitoring and research priorities

EC’s monitoring and research activities are described in Environment Canada’s Science Strategy 2014-2019, and are focused on addressing priorities that help fulfill the Government of Canada’s environmental responsibilities, including:

- reducing the impacts of contaminants and other environmental stressors on the natural environment;

- providing early warnings about weather, climate, and other environmental conditions;

- undertaking climate change mitigation and adaptation; and

- supporting environmental conservation and protection.

Specific scientific activities under these priority areas include:

- undertaking air quality monitoring to understand how changes in air pollutant emissions, transport, transformation, and deposition are impacting the environment in Canada;

- monitoring weather and climate through a variety of monitoring networks, and developing and applying tools for high-resolution modeling, to improve weather and air quality forecasts and understanding of the climate system;

- conducting water quantity monitoring to protect the health and safety of Canadians by supporting flood forecasting and emergency management;

- providing scientific studies and 24/7 support for emergency response on spills, including fate and behaviour, spill modeling, countermeasures, and monitoring techniques;

- enhancing scientific information collection on species and habitats of national interest to support conservation and sustainable development; and

- collecting and analyzing consistent environmental monitoring data (air, water, land, and biodiversity) to understand the potential cumulative effects of resource development, including the oil sands industry.

Resources

EC spent $602 million on science and technology in 2013-2014. This represented 60% of the Department’s total spending and is consistent with previous years. Scientific and technical professionals represented over half of the Department’s workforce in 2013-2014. They include research scientists, physical scientists, engineers, biologists, chemists, meteorologists, technologists, and science managers, among others.

Moreover, the Department’s internal science capacity is also increased through extensive collaboration across Canada and internationally. For example, EC’S ability to provide weather forecasts is enhanced long- and short-term by collaboration with colleagues from the United States (U.S.) and through the World Meteorological Organization. Collaborating on research projects with other top institutions helps EC stay at the leading edge of scientific inquiry

EC conducts science and research activities at facilities across the country. These facilities range from hundreds of monitoring sites, field stations, mobile labs, and major science and technology facilities.

Province |

Major Science and Technology Facility |

|---|---|

British Columbia |

|

Alberta |

|

Saskatchewan |

|

Ontario |

|

Quebec |

|

New Brunswick |

|

Federal-provincial-territorial dimensions

As the federal government shares jurisdiction over environmental matters with the provinces and territories and other federal departments, EC works with these governments and departments to undertake scientific monitoring and research on environmental issues of national and regional importance. For example, EC collaborates with the provinces and territories in the delivery of the National Air Pollution Surveillance program, which involves monitoring and assessing the quality of ambient (outdoor) air in populated regions of Canada, and providing long-term data of a uniform standard across the country. The Joint Canada-Alberta Implementation Plan for Oil Sands Monitoring is another example of scientific monitoring and research activities that EC is undertaking with its provincial and territorial counterparts, leading to an improved understanding of the long-term cumulative effects of oil sands development.

EC also works closely with provincial and territorial partners to provide the science needed to support water management in Canada. Through the Freshwater Quality Monitoring and Surveillance Program, EC monitors and reports on the status and trends of fresh water quality and aquatic ecosystem health at provincial/territorial and international boundaries, within federal lands, and nationally significant bodies of water, using a cooperative and risk-based, adaptive management approach. This involves working with provincial and territorial governments, and stakeholders on initiatives such as the Great Lakes Action Plan, the St. Lawrence Action Plan, the Atlantic Ecosystem Initiative, and the Georgia Basin. EC also partners with provincial and territorial governments through a number of water-quality agreements. In addition, in partnership with the provinces and territories, EC operates the National Hydrometric Program, which provides critical hydrometric data, information, and knowledge that Canadian jurisdictions need to make informed water management decisions.

Scientists at EC also work closely with Aboriginal governments, organizations, and communities, considering perspectives reflecting Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge (ATK) along with scientific research. For example, ATK offers long-term perspectives on local ecologies, and improves understanding of multi-species interactions in those ecologies, especially at specific times of the year, and during cycles of the species when departmental scientists are not normally present.

International dimensions

EC’s science contributes to Canada’s ability to meet key international obligations and responsibilities. EC’s scientists are part of an international community producing science assessment and global monitoring in support of Canada’s commitments under international forums such as the Arctic Council, the World Meteorological Program, the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution, the Stockholm Convention, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

EC’s science is also important for supporting the collective management of inter-jurisdictional issues. EC supports Canada-U.S. water management by providing data and expertise to international water management boards, which are overseen by the International Joint Commission, and by collaborating closely, and sharing monitoring data with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the U.S. Geological Survey. EC also delivers water quality monitoring in support of the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, a commitment between Canada and the U.S. to restore and protect the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the waters of the Great Lakes.

Environmental Emergencies

What is the issue?

Environment Canada (EC) has responsibilities and resources in the event of Environmental Emergencies.

Why is it important?

Environmental emergencies caused by the unplanned, uncontrolled, or accidental release of hazardous substances can cause harm to the natural environment, human health, and the economy. There are an estimated 35,000 pollution incidents reported each year in Canada, of which approximately 1,000 to 1,500 require EC’s scientific advice.

Responses to environmental emergencies in Canada are a joint effort that can include industry, federal, provincial, and municipal governments, and non‑governmental organizations, depending on the location and scale of the event. The party responsible for the emergency is required to report and respond to spills, and they are also liable for costs and expenses related to clean-up and environmental damage.

Environment Canada’s role

EC’s Environmental Emergencies mandate is to minimize the impacts of environmental emergencies on Canadians and their environment through the provision of science-based expert advice and regulations.

The National Environmental Emergencies Centre (NEEC) is the departmental focal point for coordinating the provision of EC’s expert advice. NEEC operates 24/7, annually receiving and triaging approximately 36,000 pollution incident reports, as well as providing scientific advice on about 2,000 significant incidents.

EC participates in all aspects of the emergency management cycle to varying degrees:

- Prevention – EC implements the Environmental Emergency Regulations (E2 Regulations) and provides expert advice on projects subject to environmental assessment;

- Preparedness – EC participates in national and international contingency planning, preparedness training, and partnership building;

- Response – NEEC provides 24/7 spills notification and, upon request, consolidates scientific and technical advice from departmental experts to inform responsible party and lead response agencies, providing them with the information needed to respond effectively (EC is very rarely the lead response agency);

- Recovery – EC provides assessment and advice to the responsible party on the restoration of environmental damage caused by major spills of oils or chemicals; and

- Scientific Support and Research and Development – EC provides environmental emergencies-related research and development activities to support provincial, national, and international (United States–[U.S.]) efforts and to improve knowledge of the fate and effect of spilled hazardous substances, spill countermeasures, and clean-up technology.

When there is an environmental emergency or incident, NEEC’s primary role is to coordinate EC’s technical and scientific expert advice and provide assistance, upon request, to the lead agency overseeing the responsible party’s response actions. NEEC coordinates the provision of advice related to weather forecasts (Meteorological Service of Canada), location of wildlife and sensitive ecosystems (Canadian Wildlife Service), and expertise on spill countermeasures and remediation options (Science and Technology Branch).

During environmental emergency incidents, EC can convene and chair a “Science Table” of technical experts with the objective to develop consensus on protection and clean-up priorities and provide a forum for rapidly moving information to minimize damage to human life or health, or to the environment.

When requested by the lead agency, EC can travel to the site of a spill and coordinate the identification of environmental protection priorities, and provide advice on response measures, including clean-up objectives and methods.

Legislation

EC administers the E2 Regulations under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA, 1999). When certain criteria and thresholds are met, the regulations require industry to prepare emergency plans for the possibility of an uncontrolled, unplanned, or accidental spill of the hazardous substances they store or handle. EC assesses hazardous substances used for commercial purposes in Canada for acute human health and environmental impacts, and to establish whether these substances should be covered by the regulations.

CEPA, 1999 and the Fisheries Act have provisions requiring responsible parties to notify a release, or the likelihood thereof, in contravention of these Acts. When a release occurs, the party responsible must take appropriate remedial measures. If the party responsible fails to take appropriate actions, as required by these Acts, EC has the authority to direct the party to take remedial measures so that the environment is appropriately protected and adverse effects of an environmental emergency are mitigated.

World Class Tanker Safety System Regime

The department is collaborating with Transport Canada, Natural Resources Canada, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada on a phased approach towards a World Class Tanker Safety System regime. The departmental activities are aimed at enhancing:

- knowledge of the local environmental priorities;

- knowledge of the behaviour of the transported products when spilled into the local environments (e.g., wave action, sediment loads);

- timely scientific information that informs safe navigation, preparedness and response decision-making to protect the environment;

- operational science that informs emergency response decisions; and

- the mechanisms to authorize appropriate use of alternate response measures for ship-based spills (e.g., spill treating agents).

Federal-Provincial-Territorial /International Cooperation

EC works closely with provincial emergency response organizations. Notification agreements are in place to avoid duplication with provinces and territories.

EC’s response to environmental emergencies is nested in the overall Government of Canada approach to emergency management. The federal government is responsible for preparing for major emergencies where an integrated federal response would be required. Through the Federal Emergency Response Plan (FERP), Public Safety Canada organizes preparedness and response activities for the federal government and identifies risks related to critical infrastructure, property, environment, economy, and national security of Canada, its citizens, its allies, and the international community. The FERP is the Government of Canada’s all-hazards emergency response plan which aims to provide a coordinated and integrated federal response to major emergencies. The overall framework guides EC’s work in emergencies.

EC works in close collaboration with its American emergency response partners. For example, it continues to work directly with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency on the 2009 Joint Inland Contingency Plan and its regional annexes, which identifies how the two countries would work together and share resources should there be a significant spill within 15 miles (25 km) of the border.

The department also participates in international exercises, where appropriate. For example, the Canadian and U.S. Coast Guards 2013 Canadian/U.S. Atlantic Joint Response Team exercise on the New Brunswick/Maine border, and the 2014 Joint Response Team in the Great Lakes.