Evaluation of the Environmental Damages Fund: final report

Final Report

Audit and Evaluation Branch October 2014

Report Clearance Steps

Planning phase completed - September 2013

Report sent for management response - April 2014

Management response received - April 2014

Report completed - April 2014

Report approved by Deputy Minister - October 2014

Acronyms used in the report

- ADM

-

Assistant Deputy Minister

- AEB

-

Audit and Evaluation Branch

- CESD

-

Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development

- CWS

-

Canadian Wildlife Service

- DFO

-

Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- EC

-

Environment Canada

- DG

-

Director General

- EDF

-

Environmental Damages Fund

- EEA

-

Environmental Enforcement Act

-

ESB

-

Environmental Stewardship Branch

- EVAMPA

-

Environmental Violations Administrative Monetary Penalties Act

- FTE

-

Full Time Equivalent

- Gs&Cs

-

Grants and Contributions

- MIS

-

Management Information System

- MOU

-

Memorandum of Understanding

- NCR

-

National Capital Region

- NSERC

-

Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada

- O&M

-

Operations and maintenance

- PAA

-

Program Alignment Architecture

- PCA

-

Parks Canada Agency

- PPSC

-

Public Prosecution Service of Canada

- PWGSC

-

Public Works and Government Services Canada

- R&D

-

Research and development

- RDG

-

Regional Director General

- S&T

-

Science and technology

- TB

-

Treasury Board

- TC

- Transport Canada

Acknowledgments

The Evaluation Project Team would like to thank those individuals who contributed to this project, particularly members of the Evaluation Committee, as well as all interviewees and survey respondents who provided insights and comments crucial to this evaluation.

The Evaluation Project Team was led by Michael Callahan, under the direction of the Environment Canada Evaluation Director, William Blois, and included Lindsay Comeau.

The evaluation was conducted by Goss Gilroy Inc., and the final report was prepared by Goss Gilroy Inc. and the Evaluation Division Project Team, Audit and Evaluation Branch.

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Background

This report presents the results of the evaluation of the Environmental Damages Fund (EDF) conducted by Environment Canada’s (EC) Audit and Evaluation Branch in 2013-14. The purpose of this evaluation was to assess the relevance and performance of the EDF.

This evaluation is part of EC’s 2012 Risk-Based Audit and Evaluation Plan, which was approved by the Deputy Minister. The evaluation was conducted in order to meet the coverage requirements of the Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation, which require that an evaluation of all direct program spending be conducted at least once every five years.

The EDF is a specified purpose account created by the Government of Canada in 1995 and administered by EC. The EDF provides a mechanism for directing funds received as a result of fines, court orders and voluntary payments related to environmental infractions to priority projects that will benefit Canada’s natural environment. Since 1998, the EDF has allocated or committed over $4.8 million and has funded 201 projects across Canada.

While the EDF is administered and delivered by EC, the Department works closely with other government departments, namely Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Transport Canada and Parks Canada Agency, which have statutes that contain sentencing provisions enabling judges to direct funds to the EDF.

EC provides oversight and accountability of monies directed to the EDF. The program solicits project proposals from eligible groups for projects that restore the natural environment or prevent harm to wildlife in the geographic region (local area, region or province) where the original incident occurred. To be eligible for funding, projects must address one or more of the following EDF categories: Restoration (highest funding priority); Environmental Quality Improvement; Research and Development; and Education and Awareness.

The two ultimate outcomes of the EDF program are:

- Environmental quality in affected or similar areas comparable to pre-incident conditions; and

- Prevention of future incidents of environmental damage or harm to wildlife.

The evaluation covers the timeframe from 2008-2009 to mid-2013-2014. The evaluation involved a review of documents, a structured review of project final reports, analysis of program administrative data, key informant interviews and a survey of stakeholders.

Findings and Conclusions

Relevance

According to evaluation evidence, there is a legislative need for the EDF program to manage financial penalties awarded under four federal departments’ statutes. The EDF funds restoration and environmental quality improvement projects that address an environmental need usually in the geographic area where the damage occurred. Documentation and interviews indicate that the role and function of the EDF program are unique.

The evaluation found that the program is aligned with federal priorities for sustainable ecosystems and environmental protection. In 2010, the priority of the program was demonstrated through the passage of the Environmental Enforcement Act, which included an amendment to several statutes for mandatory provision of fines and administrative monetary penalties to the EDF. While the program places a priority on respecting all court conditions of awards directed to the EDF, the flexible regional delivery of the program also permits departmental and regional priorities to be considered in funding decisions through the use of Regional Management Plans.

The EDF program is consistent with federal roles and responsibilities given the federal legislative basis of the program. The role of EC as lead department for the program on behalf of other federal departments is consistent with EC’s federal environmental coordination mandate as outlined in the Department of the Environment Act.

Achievement of Intended Outcomes

The evidence suggests that the program is making progress toward achieving its direct outcomes, though the way some intended outcomes have been articulated in the program logic model does not align well with the objectives and delivery of the program. While promotion of the EDF to the enforcement and legal communities has been uneven across regions, recommendations to judges for its use appear to be widespread. Almost all enforcement officials and Crown prosecutors who were consulted indicated that they would recommend the use of the EDF as a sentencing option to their colleagues. There is evidence that the number of awards directed to the EDF (though not their total value) has increased over the last five years, with a notable increase in the Prairie and Northern region. Nevertheless, there is interest in more frequent communications to the enforcement and legal communities to increase their understanding of the program and its impacts, and the transparency of the use of the funds.

Interest in EDF calls for proposals is strong among potential funding recipients, and program officials provide support to ensure quality proposals are received. Scientific and technical reviews of proposals and oversight ensure that projects are implemented in accordance with funding agreements. According to funding recipients, EDF funds were essential for the implementation of their project.

Projects funded by the EDF are contributing to intended environmental outcomes in the areas of restoration and environmental quality improvement. Project data from the EDF Management Information Systems (MIS) indicate that half of EDF-funded projects are under these two funding categories and completed projects with goals related to environmental outcomes (hectares restored or improved) have exceeded targets by about 15 to 20 per cent.

There is also evidence that the EDF program successfully funds projects under the education and awareness component that engage participants to enhance their awareness and understanding. The number of participants involved in these EDF projects again exceeds original targets (by 27 per cent), and the MIS data also suggest that behaviour change is taking place.

There is insufficient evaluation evidence on the achievement of the intended outcome related to increased knowledge due to the recent change to the funding mechanism for research and development (R&D) projects from regional to national delivery of this component. The new national process has yielded funding of only two projects since it was implemented and the amount of EDF fines assessed as appropriate for R&D has not met the original target. Performance information in the MIS is limited for R&D projects prior to the change in the funding mechanism.

Although the intended long-term program outcomes are less directly measurable, interviewees perceive that the program is contributing to improvements in environmental quality at the local level and prevention of future incidents. There are no unintended negative outcomes of the program and positive unintended outcomes include partnership development at the community level and economic impacts of projects.

Efficiency and Economy

The overall model of the EDF program as a Government of Canada program delivered by EC is widely held to be sound, with many advantages (e.g., the ability to combine small fines across acts administered by different federal departments to fund larger restoration projects, the expertise of EC staff in these types of projects). However, multiple changes to the program during the period under study have created some challenges in the efficient management of the program. Key changes include a shift from regional to national level funding of R&D component projects, consolidation of five EC regions into three, and location of the national coordination unit within the Environmental Stewardship Branch. The program is currently in a period of transition in governance as responsibility for national coordination and the R&D component has recently been transferred to the Atlantic and Quebec Region.

The full impact of the changes in the program is not yet known; however, there is evidence that the changes have yielded mixed results to date and the implementation of the 2009 EDF Management Framework has been impeded. There are divided views, for example, on the national delivery of the R&D funding component. Proponents of the model feel the 2013 MOU with the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) will lead to more impactful larger-scale investments in research, leveraging NSERC expertise for peer review and oversight. Others are concerned about the new approach which has led to an administratively burdensome process for assessment of funds, the fact that few funds have been assessed for and few projects funded under the R&D component, and the potential movement of EDF funds outside the local region to pool them for larger national projects (which could undermine the credibility of the program for the enforcement and legal communities if this is not seen as fully respecting court restrictions and addressing priorities in legislation). Other delivery challenges include: duplication in reporting due to the fact the responsibility for the EDF was shared by two Assistant Deputy Ministers during the study period, some lack of clarity in roles and responsibilities between the national coordinating unit and regions, inconsistent regional practices for engaging partner departments, lack of a clear protocol for the transfer of court-awarded funds to the EDF, and the MIS system and performance measures that do not fully meet the reporting requirements and decision-making needs at the program level.

Evidence on the efficiency of the program is mixed. At the project level, leveraging of EDF funding is strong, in spite of the absence of any requirement to secure additional sources of funds. According to administrative data, on average, EDF provided 29 per cent of all project-level funding, compared to 71 per cent that came from other sources. The majority of funded projects are also sustainable in at least some respect. Funding recipients are generally satisfied with the delivery of the EDF program. More than eight in ten agree that the funding process was timely and efficient and that the service provided by EDF staff met their needs. Funding recipients are generally less satisfied, however, with reporting requirements that they perceive to be onerous in comparison to the small amounts of funding provided by the program for some agreements. The administrative ratio of the program over the evaluation time frame is approximately 0.36, which is higher than the ratios for some EC grants and contributions (Gs&Cs) programs recently evaluated (ranging from 0.15 to 0.25). This higher ratio can be partially explained, however, by the greater administrative investment of the EDF program in managing both the incoming awards and the outgoing funds to EDF project recipients. As noted above, there are also some program management challenges detracting from the program’s efficiency.

Recommendations

The following recommendations are directed to the Regional Director General (RDG), Atlantic and Quebec Region, as the senior departmental official responsible for the management of the EDF.

- Recommendation 1: Clarify roles and responsibilities related to national coordination and program management to ensure that challenges in governance and management are being addressed.

- Recommendation 2: Clarify protocols, roles and responsibilities for the transfer and tracking of court-ordered awards for purposes of program management.

- Recommendation 3: Improve program promotion and communications to enhance awareness and understanding of the EDF.

- Recommendation 4: Clarify and communicate the national funding mechanism and use of the NSERC MOU for the R&D component to ensure that it maintains the confidence of the enforcement and legal communities in the program and permits R&D projects to move forward.

- Recommendation 5: Refine the program logic model and performance indicators to reflect the objectives and delivery of the program.

Management Response

The responsible RDG agrees with all five recommendations and has developed a management response that appropriately addresses each of the recommendations. The full management response can be found in Section 6 of the report.

1.0 Introduction

This report presents the results of the Evaluation of the Environmental Damages Fund (EDF) which was conducted by Goss Gilroy Inc. under contract to Environment Canada’s (EC) Audit and Evaluation Branch (AEB) in 2013-2014. The evaluation covers the timeframe from 2008-2009 to mid-2013-2014.

The document is organized as follows: Section 2.0 provides background information on the EDF. Section 3.0 presents the evaluation design, including the purpose and scope of the evaluation, as well as the approach and methods used to conduct the evaluation. Section 4.0 and 5.0 lay out, respectively, the evaluation’s findings and conclusions. The recommendations and management response are presented in Section 6.0.

2.0 Background

2.1 Program Overview

Purpose and Goal of the EDF Program

The EDF is a Government of Canada (GoC) program established in 1995 by a Treasury Board decision pursuant to the Financial Administration Act to oversee and manage the disbursement of funds received as compensation for environmental damages. The program’s goal is to achieve restoration of the natural environment and wildlife conservation in a cost-effective way and in accordance with conditions specified by the courts. While the EDF is administered and delivered by EC, the Department works closely with Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), Transport Canada (TC) and Parks Canada Agency (PCA), which have statutes directing funds to the EDF or that contain sentencing provisions enabling judges to direct funds to the EDF.

Environmental Legislative Framework of the EDF

Currently, six EC and three PCA statutes include a mandatory provision to direct all fines to the EDF. Another nine federal statutes contain sentencing mechanisms that may be used by judges to direct monies to the EDF. Finally, the Environmental Violations Administrative Monetary Penalties Act (EVAMPA) establishes, for 11 acts, a system of administrative monetary penalties (AMPs) that will direct all funds to the EDF. Additional details related to the environmental legislative framework of the EDF are provided in Section 4.1.3 of this report.

2.2 Program Delivery

Program Promotion

To encourage the directing of court awards and negotiated settlements to the EDF (in the absence of legislation that automatically directs them to the EDF), the program is promoted as a creative sentencing tool to the legal and the enforcement communities. Enforcement officers formulate recommendations to prosecutors regarding appropriate legal mechanisms to be used when an offence has occurred. Prosecutors are involved in plea-negotiations and make sentencing recommendations to the judge, who then makes the final ruling.

Project Delivery

EDF funds are receivedFootnote 1 by regional offices from a number of sources such as tickets (fines) issued by enforcement officers, provincial and federal civil or court awards, negotiated settlements and voluntary payments. Prior to allocating EDF funds, regional EC staff gather relevant background documents on funds received to identify any specific requirements attached to the funds. Regional offices complete an “Assessment of Funds Received” form for each individual monetary contribution to the EDF. This internal document serves as a record linking the original incident and court restrictions to recommendations for the best targeted use of the EDF contribution. EDF project categories are: Restoration; Environmental Quality Improvement; Research and Development; and Education and Awareness.Footnote 2 Best use of the funds and the category of projects to be solicited may also be informed by Regional EDF Management Plans. These plans, developed in consultation with departmental and external experts, identify program and departmental priorities as well as priority ecosystem “hot spots” relevant to each region.

Once funds are received and assessed, EC actively seeks applications from eligible organizations by posting a call for proposals on the program website and/or directly contacting potential recipients. Eligible organizations include non-profit organizations, Aboriginal organizations, universities and other academic institutions, as well as provincial, territorial and municipal governments. Projects must be cost-effective, technically feasible, scientifically sound and directly address any court or use restrictions.Footnote 3

A principle of the EDF program is that compensation directed to the EDF is used for restoration of the natural environment, including environmental quality improvement, and wildlife conservation, with priority given to projects that restore the environment in the geographic region where the original incident occurred and in accordance with conditions specified by the courts. While priority is given to restoration and environmental improvement projects, if such projects are not possible or not the best use of funds (e.g., fine for failing to submit or provide reports as required by regulations, use of tetrachloroethylene in dry cleaning), then both research and development projects and education and awareness projects related to restoration are considered.Footnote 4Project proponents are encouraged to build partnerships with other stakeholders. The maximum contribution to any single recipient and the total contribution related to any one award cannot exceed $6 million.Footnote 5

Once the proposal eligibility for funding is confirmed by EC staff, a technical review team, composed of experts from EC and other government departments, evaluates the applications for scientific and technical merit. Proposals that pass the initial screening process are reviewed by an advisory committee, which then makes funding recommendations to the Regional Director General (RDG) or delegated equivalent responsible for final approval.Footnote 6

Since 1998, the program has allocated or committed over $4.8 million in EDF funding to 201 approved projects across the five regions. Funding for new EDF projects was suspended between January and August of 2011 as part of an EC effort to develop a new national research and development (R&D) funding component that addresses priority research gaps to support and inform restoration practices. This program redesign initiative culminated in 2013 with EC signing a three-year pilot Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) aimed at integrating EDF R&D with the NSERC Strategic Project Grants Program. This new funding mechanism is intended to be a means for better achieving R&D objectives. In advance of the MOU, the first national R&D project to be funded by the EDF was approved in 2012. An initial target was set to direct 40 per cent of EDF funds to the national R&D component.

2.3 Governance Structure

In response to recommendations stemming from a 2009 evaluation of the EDFFootnote 7 , and in order to increase program effectiveness and respond to an anticipated increase in EDF awards, the Department developed an EDF Management Framework (2009) intended to address the following:

- Streamline administrative processes to ensure consistency across all regions;

- Make the program more accessible to potential funding recipients;

- Improve the measurement of program results to better demonstrate EDF Program success in achieving departmental and program objectives;

- Develop a promotional strategy that targets judges and prosecutors, officials in government departments (federal, provincial and territorial) and potential funding recipients; and

- Obtain additional resources for the administration of the EDF Program.

The EDF is managed and administered by EC. Each EC region (Atlantic and Quebec, Ontario, and West and North) is responsible for delivery of EDF restoration, environmental quality improvement and education and awareness projects. This means that the regions are responsible for regional program planning and management including management plans, project selection and approval process, information and communications management, project monitoring and evaluation, and EDF regional financial tracking. RDGs approve regional management plans (see discussion of program delivery in Section 2.2), projects and funding agreements.Footnote 8

Until recently, a national program manager within the Environmental Stewardship Branch (ESB) provided a program coordination role. With the change of program responsibility in January 2014 to the RDG of the Atlantic and Quebec Region, the national program coordination role and responsibility for the new nationally-delivered R&D component has shifted to this region.

A national DG Committee (with representatives from EC and other federal government departments) has recently been established to provide overall guidance on the implementation and administration of the EDF. Membership in this committee includes EC (ESBFootnote 9 , Science and Technology Branch, Enforcement Branch, RDGs), DFO, PCA and TC. The terms of reference for this committee state that the purpose of the EDF DG Committee is to provide oversight and direction for the administration of the EDF program.

2.4 Resources

As of 2012, the EDF had received over $6.5 million in funds from 197 awards.Footnote 10Per the Treasury Board Policy on Specified Purpose Accounts, monies directed to a specified purpose account may cover administrative costs when they are specifically authorized by the enabling authority. In the case of the EDF, enabling authorities include: the courts, whereby a judge may specify that money from an award may be used for administrative purposes; and any legislation that makes provisions to allow money from an award to be used to administer the EDF.Footnote 11There are draft program guidelines in place for the potential use of a portion of awards for administrative purposes. The EDF has, traditionally, been administered using minimal existing departmental resources. As indicated in Table 2.1, total departmental funding (Vote 1) allocated for EDF administration for EC over the five-year period of 2008-2009 to 2012-2013 is approximately $988,000.Footnote 12

A more detailed discussion of program resources can be found in Section 4.2.2 under the discussion of demonstration of efficiency (evaluation question 10).

| 2008-2009 | 2009-2010 | 2010-2011 | 2011-2012 | 2012-2013 | 2013-2014 Budget | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTEs | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 4.5 |

| Salaries | 43,928 | 35,779 | 96,399 | 289,299 | 250,862 | 335,949 |

| O&M | 37,708 | 74,037 | 63,631 | 43,794 | 52,765 | 69,000 |

| Totals | 81,636 | 109,816 | 160,030 | 333,093 | 303,627 | 404,949 |

- FTE information for 2008-2009 to 2012-2013 extracted from EC’s Salary Management System.

- Salaries and O&M for 2008-2009 to 2012-2013 from EC's financial system, as provided by Finance Branch. As EDF work is co-located with that of other EC funding programs, program management is concerned that actual salary usage for 2008-2009 to 2012-2013 may be more than reported in EC’s financial system. For example, during this timeframe staff may have incorrectly coded some of the EDF-related work they did under the EcoAction Community Funding Program. EDF program management plans to take measures to improve the accuracy of financial coding.

- 2013-14 Budget data from Environment Canada, New Program Model and Resources Dedicated to EcoAction and the Environmental Damages Fund (EDF), Draft April 2012 revised April 2013.

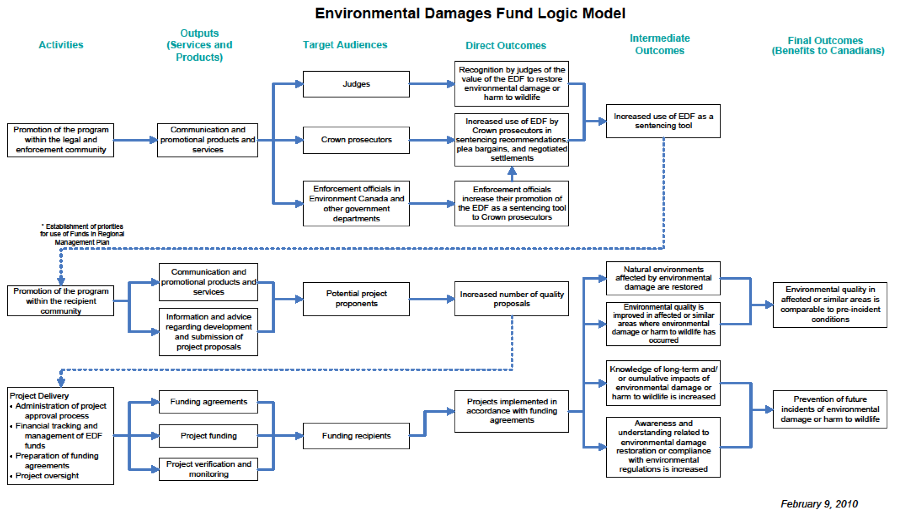

2.5 Program Logic Model

The logic model used for the purpose of the evaluation can be found in Annex 1. The final outcomes to which the EDF is ultimately intended to contribute are:

- Environmental quality in affected or similar areas comparable to pre-incident conditions;

- Prevention of future incidents of environmental damage or harm to wildlife.

3.0 Evaluation Design

3.1 Purpose and Scope

The purpose of this evaluation is to assess the relevance and performance (including effectiveness, efficiency and economy) of the EDF. The evaluation covers the time frame from 2008-2009 to mid-2013-14.

The evaluation of the EDF is part of EC’s 2012 Risk-Based Evaluation Plan, approved by the Deputy Minister, and is intended to support evidence-based decision making in policy, expenditure management and program improvements. The evaluation was conducted in order to meet the coverage requirements of the Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation, which require that all direct program spending be evaluated at least once every five years.

3.2 Evaluation Approach and Methodology

The methodological approach and level of effort for this evaluation were calibrated, taking into consideration the statutory basis of the program, senior management feedback, and AEB assessment of risk. Findings of previous evaluations of the program have been positive, thus lowering the overall risk associated with the program. However, the implementation of the EDF Management Framework in 2009 and recent changes to the administration of the program were key considerations for evaluation scoping. Custom questions were included in data collection instruments to address the evolution of the EDF, including questions related to design, delivery and governance. With these considerations, the following data collection methodologies were employed and the evidence from these methods was triangulated to develop findings and conclusions.Footnote 13

Document Review

Key documents were gathered and reviewed using a document review template. Documents included: descriptive program information (e.g., EDF Management Framework, regional management plans, funding agreement Terms and Conditions, program guidelines), departmental and Government of Canada publications related to policy and priorities, and performance and evaluation reporting documents (the EDF Evaluation Plan, 2009 Evaluation of the EDF).

Management Information System (MIS) Data Analysis

An extract of EDF administrative data from the MIS database that included all relevant project data for the study timeframe was obtained for analysis. During the period under study, 100 projects were funded, including 72 completed projects and 28 ongoing projects. The database contains information on past and current projects, including information from application forms and project performance reports. Among other fields, the database includes descriptive information on program activity, financials (awards and project funding), and data on both targets and actual performance related to key environmental and capacity-building indicators. These data were used primarily for an assessment of the program’s achievement of outcomes.

Review of Project Final Reports

A review of a sample of project final reports was completed to examine project activities, outputs, outcomes and lessons learned in more depth. This method involved reviewing a sample of 33 completed EDF project final reports. Projects were selected to broadly represent overall program activity on a number of criteria: EDF funding category; project size (i.e., dollar value); fiscal year; funding recipient type; and region. Findings from the file review addressed the issue of performance.

Key Informant Interviews

Key informant interviews were conducted either in person or by telephone with a total of 23 respondents. All relevant stakeholder perspectives were considered in the key informant interview analysis. Other lines of evidence (i.e., survey of stakeholders) also gathered the perspectives of individuals not directly accountable for the program, providing a balanced blend of views on program performance. The following provides a breakdown of the interviewees:

- EC senior management (n=2);

- EDF program management and project officers (n=9);

- EC enforcement regional directors (n=3);

- Federal partners (e.g., DFO and PCA officials who participate in technical reviews and recommendations for funding, representatives from the Public Prosecution Service of Canada (PPSC)) (n=5); and

- EDF funding recipients (n=4).

A customized, open-ended guide was developed for each interviewee category. Interviewees received a copy of the interview guide in advance of the interview. The findings from the key informant interviews addressed all evaluation questions, but were particularly important for the performance issue.

Online Survey of Stakeholders

An online survey was conducted of EDF stakeholders, including 1) recipients of EDF funding; 2) enforcement officers, managers and regional directors; and 3) Crown prosecutors. The approach to conducting each of these surveys is described below.

- Funding recipients. This survey was sent to the project contacts for all projects receiving funding during the period under study (n=93).Footnote 14 Respondents received an email survey invitation with a link to the online survey. During the survey period, a telephone reminder and reminder emails were sent to those who had not yet completed the survey.

- Enforcement personnel. EC Enforcement Branch provided a listing of 253 enforcement officers, managers and regional directorsFootnote 15. Similar to the survey of funding recipients, all individuals received an email invitation with a link to the survey, and a telephone reminder and two email reminders were sent to non-respondents during the survey period.

- Crown prosecutors. For Crown prosecutors, 11 regional PPSC team leaders for regulatory prosecutions or Chief Federal Prosecutors were asked to distribute an open link to the survey to relevant staff in their teams/offices, including Crown prosecutors who have had or potentially could have had some exposure to the EDF in their work.

Data collection for the survey took place between February 3 and March 3, 2014. In total, 40 survey questionnaires were completed by funding recipients for a response rate of 43 per cent and 82 surveys were completed by enforcement personnel for a response rate of 32 per cent. Completed surveys were received from 11 Crown prosecutors. However, as the total number of Crown prosecutors that received a forwarded link is unknown, a response rate cannot be calculated. The detailed findings for key survey questions are presented in Annex 2.

3.3 Limitations

Challenges experienced during the conduct of the evaluation, as well as the related limitations and strategies used to mitigate their impact, are outlined below.

1. Evolving environment

The EDF operational program environment has been affected by many changes during the period under study, including consolidation of regional operations from five regions to three, introduction of a new national mechanism to disburse research and development funds, legislative amendments pertaining to use of the EDF under several pieces of legislation and, during the conduct of the evaluation, a shift in the responsibility centre for the program from the Strategic Priorities Division, ESB, to the Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS), ESB, and finally to the Regional Director General’s Office (RDGO) in the Atlantic and Quebec Region. The lack of stability in the program during the period under study affected the analysis and assessment of several of the outcome indicators. This impact has been noted throughout the report where relevant.

2. Quality of performance data

While the EDF program has a performance measurement strategy linked to the outputs and outcomes in the logic model, regular reporting (e.g., an annual EDF performance report) is not yet occurring. As well, the performance data available in the MIS were limited. As the number of completed EDF projects is small and highly variable, and not all completed projects had performance information, there were few observations available for each of the many performance indicators. Only those performance indicators that had data for nine projects or more (selected as a threshold based on the distribution of the observations) were included in the analysis of performance data.

4.0 Findings

This section presents the findings of this evaluation by evaluation issue (relevance and performance) and by the related evaluation questions. For each evaluation question, a rating is provided based on a judgment of the evaluation findings. The rating statements and their significance are outlined below in Table 4.1. A summary of ratings for all evaluation questions is presented in Annex 3: Summary of Findings.

| Statement | Definition |

|---|---|

| Acceptable | The program has demonstrated that it has met the expectations with respect to the issue area. |

| Opportunity for improvement | The program has demonstrated that it has made progress to meet the expectations with respect to the issue area, but continued improvement can still be made. |

| Attention required | The program has not demonstrated that it has made progress to meet the expectations with respect to the issue area and attention is needed on a priority basis. |

| Not applicable | There is no expectation that the program would have addressed the evaluation issue. |

| Unable to assess | Insufficient evidence is available to support a rating. |

4.1 Relevance

4.1.1 Continued Need for Program

| Evaluation Issue: Relevance | Rating |

|---|---|

| 1. Is there a continued need for the EDF program? | Acceptable |

There is a demonstrated need for the EDF program to manage financial awards which are directed to the program under multiple federal statutes. There is evidence that investments in restoration projects of the type funded by the EDF continue to be required to ensure healthy ecosystems and conserve wildlife. The EDF program addresses this need and is unique at the federal level.

- The EDF manages funds from fines awarded under environmental legislation from four responsible federal departments. There is a mandatory provision to direct all fines to the EDF in eleven of these statutes. The EDF provides a mechanism so fines need not be dealt with by each department on a case-by-case basis.

- Documentary evidence on the condition of the environment links the quality of the environment with the health of individuals, as well as long-term economic growth and competitiveness.Footnote 16 The Fall 2013 report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development (CESD) concluded that “[…] Canada continues to lose ground in key areas […] including […] deteriorating biodiversity conditions in all of the main types of ecosystems in Canada […] [and] 518 species are at risk of disappearing.”

- Program documents and key informants confirm that the EDF is a unique mechanism for the management of federal court awards and financial penalties and, therefore, does not duplicate other programs. It should be noted that a few key informants identified some regional programs that are similar to the EDF in directing environment damage awards to environmental projects; however, these alternative mechanisms operate at the provincial level or target select environmental issues.Footnote 17

4.1.2 Alignment with Federal Government Priorities

| Evaluation Issue: Relevance | Rating |

|---|---|

| 2. Is the EDF program aligned with federal government priorities? | Acceptable |

The EDF program is consistent with federal and departmental priorities related to environmental protection and sustainable ecosystems. Recent legislative amendments have raised the profile of the EDF by including a mandatory provision to direct fines and administrative monetary penalties to the EDF, which support federal priorities to protect Canada’s water and land. While the program places a priority on respecting all court restrictions on the awards in the disbursement of funds to projects, the flexible nature of the program and regional delivery also permit departmental and regional priorities to be considered in funding decisions.

- In the 2009 federal Speech from the Throne, the government promised to address deficits in the enforcement regime for environmental legislation and regulation by “bolster[ing] the protection of our water and land through tougher environmental enforcement that will make polluters accountable.” Priority of the EDF was highlighted in 2010 with the coming into force in December 2010 of Bill C-16, the Environmental Enforcement Act (EEA), which amended six EC and three PCA statutes to include a mandatory provision to direct all fines to the EDF and to increase minimum and maximum fines for individuals and corporations.Footnote 18

- The EEA also enacted the Environmental Violations Administrative Monetary Penalties Act (EVAMPA) which establishes, for 11 acts, a system of administrative monetary penalties (AMPs) that will direct all funds to the EDF.

- At the departmental level, within EC’s Program Alignment Architecture (PAA), EDF activities support the Departmental Strategic Outcome, “Canada’s natural environment is conserved and restored for present and future generations.”Footnote 19

- Departmental and regional priorities have been articulated in Regional EDF Management Plans. These priorities inform the disbursement of funds that are not subject to court restrictions or for which a suitable recipient has not been identified, while respecting the program priority to fund projects that address the region and type of infraction that resulted in the EDF award.

- Key informants agree that the EDF is consistent with federal priorities and roles and responsibilities due to the legislative base of the program.

4.1.3 Consistency with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

| Evaluation Issue: Relevance | Rating |

|---|---|

| 3. Is the EDF program consistent with federal/departmental roles and responsibilities? | Acceptable |

The EDF program is consistent with federal/departmental roles and responsibilities given the statutory basis of the program and EC’s mandate articulated in the Department of the Environment Act.

- The evaluation evidence confirms that the EDF is relevant to federal government and departmental roles and responsibilities given the statutory basis of the program. A total of 9 statutes have a mandatory provision to direct fines to the EDFFootnote 20,Footnote 21 and are also included within the EVAMPA AMPs that will direct all funds to the EDF. The Canada Water Act and the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act are also included in the EVAMPA legislation.

- In addition to statutes amended under the EEA, there are a number of federal acts that also contain provisions that can be used to direct court awards, fines and negotiated settlements to the EDF.Footnote 22

- Bill C-45 (2012) amended the Fisheries Act by adding a provision so that all fines received with respect to an offence under section 40 are to be automatically directed to the EDF. Footnote 23This Act came into force in November 2013.

- EC’s administrative role for the EDF is consistent with the Department of the Environment Act which confirms the Department’s responsibility for “the coordination of the policies and programs of the Government of Canada respecting the preservation and enhancement of the quality of the natural environment.”

4.2 Performance

4.2.1 Achievement of Intended Outcomes

| Evaluation Issue: Performance | Rating |

|---|---|

| 4. To what extent have intended direct outcomes been achieved as a result of the EDF program? | Acceptable |

There is evidence that the EDF program is addressing intended direct outcomes, including the promotion and use of EDF as a creative sentencing option by the enforcement and legal communities. Interest in EDF calls for proposals is strong among potential funding recipients and program officials provide support to ensure quality proposals are received. Scientific and technical reviews of proposals and oversight ensure projects are implemented in accordance with funding agreements.

Increased promotion of the EDF by enforcement officials as a sentencing tool to Crown prosecutors - Acceptable

- All key informants from the enforcement and legal communities agree that enforcement officials promote the EDF to Crown prosecutors. The EDF is included as part of the basic training for EC enforcement officers as a creative sentencing option. The EEA amendment to several federal statutes is perceived by some to have further raised the profile of the EDF among enforcement officials, Crown prosecutors and judges. Almost all enforcement officials and Crown prosecutors surveyed indicated that they would recommend the use of the EDF as a sentencing option to colleagues in the enforcement and legal communities.

Increased use of the EDF by Crown prosecutors in sentencing recommendations, plea bargains and negotiated settlements - Acceptable

- There is a consensus among key informants from the enforcement and legal communities that Crown prosecutors are widely and actively using the EDF as a creative sentencing option. Crown prosecutors who responded to the survey indicated that their use of the EDF has increased or stayed the same in the last five years.

Recognition by judges of the value of the EDF for environmental restoration and wildlife conservation - Unable to assess

- No direct information was gathered from judges for this evaluation given challenges in contacting this group, though several key informants noted that judges rely heavily on the recommendations from the Crown prosecutors in sentencing, including recommendations for the use of the EDF.

Increased number of quality project proposals submitted - Acceptable

- During the period under study, the MIS indicates that 277 EDF project proposals were received. The final decision on the proposals recorded in the MIS shows that about 40 per cent of proposals received are funded.Footnote 24 Projects are prioritized based on a scientific and technical review. According to program officials, projects are most often not approved due to limitations in the amount of EDF funds available rather than poor proposal quality.

- Most internal program key informants hold the view that the quality of proposals received for EDF are of high and even “excellent” quality that has been improving over time. According to key informants, this is achieved by providing ample lead time for the proponent to prepare a proposal and being proactive in supporting potential recipients during the submission period. It should be noted that a few program key informants emphasized that calls for proposals for the EDF are not amenable to soliciting a large number of proposals as they are often very focused, reflecting restrictions specified by the court. Indeed, several respondents indicated that increasing the number of proposals is not an appropriate indicator of program success; rather, quality is what is important.

Projects implemented in accordance with funding agreements - Acceptable

- Key informants involved in project delivery agree that EDF projects have been implemented in accordance with funding agreements and with court restrictions. The flexibility of the program in designing calls for proposals, negotiated funding agreements with proponents and oversight (e.g., through site visits, reporting against workplans, final reports) were named as important elements in ensuring compliance. Almost all funding recipients surveyed indicated that their project objectives had been completed as planned to a good extent.

| Evaluation Issue: Performance | Rating |

|---|---|

| 5. To what extent have intended intermediate outcomes been achieved as a result of the EDF program? | Acceptable |

Program data suggest an increased use of the EDF as a sentencing tool. There is evidence that the program is funding projects in the priority areas of restoration, environmental quality improvement and education and awareness. Performance targets for these projects are being exceeded. It is not possible to assess the program’s contribution to increased knowledge at this time as only limited performance information was available and a new national funding component for R&D projects has only recently been implemented.

Increased use of EDF as a sentencing tool - Acceptable

- A clear trend in the use of the EDF as a sentencing tool is difficult to discern as the number of awards is quite small and fluctuates year over year during the study period (see Table 4.2). However, considering the current period of study compared to the previous five-year period (2003 to 2007), the use of the EDF appears to have increased overall: from 65 awards during the previous period to 95 awards during the current five-year study period. The total value of the awards has remained equivalent between the two study periods, from $2.87 million in the previous five-year period to $2.88 million in the five-year period covered by the current evaluation of the program.

Table 4.2: Number and Value of Court Awards by Region (2008-2012)

| Region | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | Total | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlantic | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 14 | 15% |

| Quebec | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5% |

| Ontario | 6 | 7 | 8 | 11 | 4 | 36 | 38% |

| PNR | 2 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 33 | 35% |

| PYR | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 7% |

| Total | 15 | 17 | 20 | 25 | 18 | 95 | 100% |

| Region | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | Total | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlantic | 78 | 5 | 50 | 90 | 153 | 376 | 13% |

| Quebec | 0 | 0 | 5 | 9 | 42 | 56 | 2% |

| Ontario | 62 | 126 | 68 | 121 | 75 | 452 | 16% |

| PNR | 28 | 79 | 669 | 500 | 499 | 1,775 | 62% |

| PYR | 34 | 14 | 57 | 117 | 0 | 222 | 8% |

| Total | 202 | 224 | 849 | 837 | 769 | 2,881 | 100% |

- Source: EDF Management Information System.

- A notable increase in program activity is in the Prairie and Northern region, which accounts for 62 per cent of the value of awards. A review of the 33 EDF awards in this region and the views of a few key informants indicate that this increase in activity can be partially attributed to the high monetary value of a small number of awards associated with the development of the oil sands in northern Alberta and also to the effectiveness of the PPSC in Alberta which has a dedicated unit for the prosecution of environmental offences within its regulatory and economic crime unit.

- For the period from 2008-09 to 2012-13, the legislative source of EDF awards (expressed as a percentage of the number of EDF awards) was as follows:

- Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999(43%)

- Fisheries Act (32%)

- Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994(9%)

- Wild Animal and Plant Protection and Regulation of International and Interprovincial Trade Act (8%)

- Other legislation (8%)Footnote 25

- It is acknowledged that an increased use of the EDF as a sentencing tool may be more difficult for the program to influence in the future as the current legislation already has a mandatory provision to direct fines to the EDF.

Restoration of natural environments affected by environmental damage and improved environmental quality in areas where environmental damage or harm to wildlife occurred - Acceptable

- Program funding guidelines establish a priority for EDF-funded projects to address restored or improved environmental quality. During the period under study, 29 projects were funded under the restoration category for a total of $807,000, representing about 30 per cent of the funding allocated. With respect to improved environmental quality, 26 projects were funded under this category for a total of $547,000, representing 21 per cent of the funding allocated.

- Performance data from the MIS provide a detailed view of the environmental impacts achieved by EDF projects. The following table presents the established project targets/goals and actuals for projects completed during the study time frame with respect to restoration/environmental quality indicators.Footnote 26 Actuals for completed projects exceeded targets by just under 20 per cent for both of the environmental performance indicators for the restoration of natural environments affected by environmental damage.

| Performance Indicator | Number of Projects | % of Target Achieved | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Results of Completed Projects - Goal | Results of Completed Projects - Actual | |||

| Number of hectares where restoration activities have been implemented | 16 | 814 | 970 | 119% |

| Number of hectares of natural environment created or enhanced | 17 | 2,050 | 2,404 | 117% |

- Key informants and most surveyed funding recipients agree that EDF-funded projects are contributing to restoration and environmental quality improvement (see Table 4 in Annex 2 for detailed survey findings). Key informants in the regions pointed out that the majority of projects funded address one of these two objectives and projects are carried out in accordance with the funding agreements in the regions where the damage occurred. All project funding recipients that were interviewed agree that program funding has been essential for success. EDF funding has helped to leverage additional in-kind support, create a strong community of volunteers, and has allowed restoration projects to commence.

- Several key informants noted that this outcome phrasing is somewhat misleading in that restoration and environmental quality projects often do not address the incident where environmental damage or harm to wildlife occurred as the clean-up of these areas is addressed by the individual or company responsible for the damage.

Increased knowledge of long-term and/or cumulative impacts of environmental damage or harm to wildlife - Unable to assess

- It is not possible at this time to assess progress toward achievement of the intended outcome related to increased knowledge. As mentioned previously (Section 2.2), the EDF R&D funding category has undergone a fundamental shift during the period of study from regional funding of R&D projects to a centralized R&D funding mechanism delivered nationally. Funding for new EDF projects was suspended between January and August of 2011 as the new R&D funding mechanism was established. Prior to this change, 14 projects were funded under the research category for $494,000 or 19 per cent of funds allocated; however, only a small number of these projects reported performance information.

- Since the change in the funding mechanism only one project has been funded under the new R&D category (for $320,000), and another is in the process of being funded. In the last two years of the program, the process for the assessment of funds at the regional level has not identified any EDF awards as being appropriate for the R&D category (i.e., no awards have been identified that could be directed to the national component as this was precluded by court restrictions and the priority for funding restoration in the geographic area where the damage occurred).

Increased awareness and understanding related to environmental restoration and/or compliance with environmental regulations - Acceptable

- In total, 25 EDF projects were funded under the education and awareness funding category during the period under study with total funding of $423,000, representing about 16 per cent of the funds allocated. Note that restoration and environmental quality improvement projects often include an education component as a secondary priority, and so the level of activity in this category is actually greater than the 16 per cent indicated above.

- With respect to participation-related performance indicators, the MIS system records that the participation levels expected across 23 projects were exceeded by 27 per cent (Table 4.4). In terms of stimulating behaviour change among participants, nine projects aimed to modify target audience behaviours and the target was exceeded by 15 per cent, albeit with caveats associated with self-reported data of this kind.Footnote 27

| Performance Indicator | Number of Projects | % of Target Achieved | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Results of Completed Projects - Goal | Results of Completed Projects - Actual | |||

| Participants attending project activities | 23 | 7,946 | 10,098 | 127% |

| Target audience that confirmed modification in behaviour as result of project activities | 9 | 2,084 | 2,403 | 115% |

- Key informants generally agree that the program is contributing to the achievement of outcomes in the area of awareness and understanding through projects that are funded under the education and awareness category. While there are some limitations associated with the second performance indicator in the table above (i.e., it is a measure of self-reported behaviour change as opposed to a direct measure of awareness), it does provide some evidence of increased awareness and understanding. The project final reports and interviews with project funding recipients provide examples of the engagement of participants (e.g., students and community members) to raise awareness about sources and impacts of pollution.

| Evaluation Issue: Performance | Rating |

|---|---|

| 6. To what extent have intended final outcomes been achieved as a result of the EDF program? | Acceptable |

Although an assessment of these outcomes is less directly measurable and therefore relies to a much larger extent on subjective feedback, EDF-funded projects are generally thought to be leading to improvements in environmental quality and prevention of future incidents. However, these impacts are of a very local nature given the small size of EDF projects.

- The final intended outcomes for the EDF are high level and of a longer-term nature. The impact of the program on these outcomes must be understood in the context of the typically small size and local nature of EDF-funded projects and challenges in measuring changes in these longer-term outcomes that can be attributed to the EDF program (as opposed to external factors).

Environmental quality in affected or similar areas is comparable to pre-incident conditions - Acceptable

- Almost all key informants agree that the restoration and environmental quality improvement projects are having a positive impact in addressing environmental damage and wildlife conservation. Examples from the project final reports and interviews with funding recipients include: removal of toxic and noxious substances, shoreline stabilization, the return of indigenous species, improved spawning grounds, and increased greenery. Several key informants noted, however, that EDF projects are of a very limited scale and, therefore, impacts are modest.

- Some key informants questioned the wording of this intended outcome, however, because projects often do not address “pre-incident conditions” as referenced in the outcome. For instance, some infractions are of an administrative nature (e.g., non-compliance with reporting requirements) and therefore not linked to damages to a particular area or to an incident. For other awards that are linked to a specific incidence of damage, the specific incident may not be amenable to restoration through an EDF project for a variety of reasons (e.g., the damage was ameliorated naturally, the individual or company responsible for the damage has completed the clean-up of the area).

Prevention of future incidents of environmental damage or harm to wildlife - Acceptable

- Almost all interviewees are of the opinion that prevention of future incidents is being achieved through projects funded under the education and awareness category of the program. Increased understanding and behaviour change achieved through these projects are expected to reduce future behaviours that could cause environmental damage or harm to wildlife. A small number of funding recipients noted as well that the use of volunteers for restoration and environmental quality improvement projects raises awareness among these participants. Finally, a few respondents argued that the program contributes to prevention by reinforcing the ‘polluter pays’ principle.

| Evaluation Issue: Performance | Rating |

|---|---|

| 7. Have there been any unintended outcomes of the EDF Program, positive or negative? | Not applicable |

Progress toward achievement of intended outcomes is being achieved without unintended negative outcomes. Reported positive unintended outcomes relate to increased partnerships and the economic impacts of projects and restored natural environments.

Overall, the majority of unintended outcomes of the EDF program reported by key informants or in the project final reports were positive. A few key informants and the review of project final reports noted that, although partnerships and leveraged funding are not a condition of program funding, almost all projects are very successful in establishing partnerships, which leads to sustainability (discussed in more detail in Section 4.2.2). Other examples of unintended outcomes mentioned by key informants are employment and the economic impacts of EDF projects, including the employment of summer students and the impact of a restored natural environment for economic activities (e.g., tourism).

- At the project level, the review of project final reports found unintended outcomes related to improvements to other aspects of the environment not targeted by the project (e.g., a project related to air quality led to improvements in water quality after the intervention); and new discoveries related to environmental research such as the discovery of a new species of plant or fish.

4.2.2 Efficiency and Economy

| Evaluation Issue: Performance | Rating |

|---|---|

| 8. Are effective governance and accountability structures in place to guide and coordinate EDF priorities and activities? | Attention required |

Governance of the program has undergone a series of changes during the study period and during the conduct of the evaluation. Challenges around program management and governance relate to the national mechanism for funding R&D projects, dual location of program responsibility, and some lack of clarity in roles and responsibilities between the national coordinating unit and regions. Engaging partner departments at the regional level is inconsistent and, at the national level, the relationships are underdeveloped with partners who wish to participate more fully but find the tools and guidance (e.g., clear procedures for directing fines, etc. to the EDF) lacking for them to do so. Other program management issues include: 1) the requirement for tracking of financial awards which is a necessary, but burdensome and largely unrecognized activity now undertaken by the regions; and 2) the MIS system and performance measures that do not fully meet the reporting requirements and decision-making needs at the program level.

Governance and Management

Context. Between late 2009 and early 2014, a national coordination unit within the ESB was in operation, based in the National Capital Region (NCR). The coordination unit was responsible for national EDF management, promotion, national consistency of program implementation and delivery, maintaining the MIS, and overseeing the performance of national program delivery. Since 2012, the NCR national coordinating unit was also responsible for project selection and approval, funding agreements and project monitoringFootnote 28and evaluation of the new national R&D component. The regions were (and remain) responsible for disbursement of EDF funds. In early 2014, as the evaluation was underway, there was a change in the EDF management structure; the ESB is no longer involved with the management of the program and national coordination of the EDF and responsibility for the national R&D funding component were transferred to the office of the RDG - Atlantic and Quebec Region.

- Internal program key informants expressed mixed views about the EDF governance and management, often noting that the numerous changes to the program since 2009 have created program management challenges. Common issues that were raised in the key informant interviews include:

- Challenging new national mechanism for the delivery of the R&D funding category. There are challenges with the national mechanism for the R&D funding category, which pools EDF funds for R&D nationally to be disbursed through an MOU with NSERC, and it generated a number of comments among internal and some external key informants. Among those who expressed concerns about the new approach, issues include:

- The credibility of the program could potentially be undermined in the regions if EDF funds flowing out of the province to a national mechanism are not seen as justified (e.g., respecting court restrictions, addressing environmental priorities in legislation).

- An administratively burdensome “assessment of funds” process is required for all awards that are received, regardless of amount, to determine the appropriate funding category. The process has placed regional and NCR colleagues in the difficult position of assessing funds against their respective funding priorities.

- There is a lack of research projects funded under the new mechanism. To date, only two projects have been funded using the NSERC MOU. A few key informants questioned the degree to which the EDF funding of NSERC projects is having an incremental impact (i.e., the EDF monies are used to fund projects that would have gone ahead anyway). The mechanism has limited the ability of regions to fund R&D projects and for non-NSERC-funded researchers to access EDF funds.Footnote 29

- Challenging new national mechanism for the delivery of the R&D funding category. There are challenges with the national mechanism for the R&D funding category, which pools EDF funds for R&D nationally to be disbursed through an MOU with NSERC, and it generated a number of comments among internal and some external key informants. Among those who expressed concerns about the new approach, issues include:

Among the minority of respondents who have been involved in and favour the new national mechanism, they feel the national process holds promise to fund leading edge research with greater impact and with a stronger tie to federal priorities and research gaps related to restoration by funding larger-scale projects approved by a national research authority (NSERC).

- Problematic dual location of program responsibility. With the location of the national coordination unit and R&D component within ESB, a dual track reporting and accountability structure was created to two Assistant Deputy Ministers (ADMs) -- the ADM, ESB (responsible for the former Strategic Priorities Division and CWS) and the ADM, Strategic Policy (responsible for the RDG Offices). Several internal key informants found this structure overly complex leading to duplication of effort, inefficient and multiple approval processes, and confusion in program accountability. As noted above, however, as of early 2014 ESB is no longer involved with program management, and national coordination of the EDF and the national R&D funding mechanism are the responsibility of the office of the RDG - Atlantic and Quebec Region.

- Lack of clarity in roles and responsibilities. Roles and responsibilities between the national coordinating unit and regions are not sufficiently clear in the view of some regional key informants who also feel the distribution of roles and responsibilities between the national coordinating unit and regions should be re-examined in some key areas (e.g., communications, financial tracking and assessment of awards).

Engagement and Collaboration with Partner Departments

- Key informants reported that EDF interdepartmental engagement and collaboration with EDF partner departments (i.e., those departments with primary responsibility for the administration of legislation containing provisions that can be used to direct court awards, fines and negotiated settlements to the EDF) occur:

- At the national-level, through the newly formed DG committee comprised of EC representatives and partner departments; and

- At the regional level; however, engagement of partner departments is variable.

- Long-established programming in the Atlantic provinces features an established interdepartmental committee (which includes CWS, DFO and TC) involved in the posting of the call for proposals, technical review and decision/recommendation based on their expertise. Engagement with partner departments is not consistent across the regions, however, as some regions engage departments on an ad hoc and informal basis and others not at all. Challenges to more fully engaging partner departments are a lack of resources for outreach work and resource constraints within partner departments that limit their capacity to participate. For their part, the small number of regional partners that were interviewed expressed satisfaction with their engagement by the program; they described the process as very transparent and open, and no improvements were recommended.

Protocols/Roles and Responsibilities for Financial Transfers to EDF

- The evaluation evidence indicates a lack of protocols to ensure the effective and timely transfer of EDF awards made by the courts to the program and a lack of clarity in the roles and responsibilities among those involved (provincial courts, enforcement, Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC) and EC). This was noted as a challenge by program staff who must identify and track the source of awards, as well as by enforcement officers surveyed who frequently identified the process to deposit fines with the EDF as needing improvement.

- In the view of program staff, the lack of clear procedures in this area leads to some challenges in the identification and tracking of EDF awards, including:

- Lack of resourcing/acknowledgement of this area of activity in the management framework; and

- Lack of clarity in responsibilities for identification and tracking of awards (currently done by the regions, but some say this activity requires more guidance/assistance from the national coordinating unit).

- Similarly, feedback from program partners suggests that the protocols to assist them in participating in the program are lacking (e.g., guidance on the procedures for directing fines, voluntary awards or other payments to the EDF).

- The NCR national coordinating unit recently participated in an AMPs working group to build relationships at the national level between the program, regulatory/enforcement personnel and finance to determine how best to manage and track AMPs directed to the EDF, though it is too soon to assess the impact of this initiative.

Performance Measurement and Reporting

- An EDF Performance Measurement Framework was approved in 2010 that includes 18 performance indicators relating to the outputs and intended outcomes of the program. Overall, the majority of program key informants believe that there are some significant issues with the usefulness of the performance data collected. The limitations include:

- an outdated management information system with limited aggregation and reporting capabilities that is unable to provide the level of information required to make decisions about the program; and

- some performance indicators that are not appropriate for the program context (e.g., some indicators require customization, such as alignment of projects with legislation/court restrictions, and others could be abandoned, such as those related to the percentage of habitat restored).

- At the level of project reporting, the file review demonstrated that projects submit final reports detailing the results of their activities according to the key program intended outcomes. In the key informant interviews, the majority of funding recipients indicated that the reporting requirements are appropriate. Funding recipients surveyed are less satisfied with the ease of use and level of detail required in the reporting forms (see Table 1 in Annex 3) and they made several comments urging the program to streamline reporting and ensure reporting requirements are commensurate with the value of the agreement (which can be quite small). During the period under study the program revised aspects of the reporting forms that are within their control, however it was too early for the present evaluation to assess the impacts of these efforts.

| Evaluation Issue: Performance | Rating |

|---|---|

| 9. To what extent has progress been achieved in the implementation of the 2009 EDF Management Framework? | Opportunity for improvement |

There has been some progress in implementation of the 2009 EDF Management Framework, though this has been impeded by changes to the management of the program and broader departmental changes. A deficiency in program administrative resources, identified in the 2009 framework, has been addressed as the EDF program had more administrative resources during the evaluation time frame than in previous years. On the other hand, enhancing national consistency in some program processes and increasing promotion of the program to key constituencies remain outstanding items for the implementation of this framework.

- In 2009, EC adopted the EDF Management FrameworkFootnote 30 which specified a number of measures intended to enhance national consistency, promote the program to funding recipients and the enforcement and legal communities, address a deficiency in administrative resources, and improve the measurement of program resultsFootnote 31. In general, internal program key informants reported that the 2009 Management Framework has been implemented to only some degree owing in large part to a period of significant change following the approval of the Framework (e.g., redesign of the R&D component, moratorium on program activity from January to August 2011) and challenges in the broader program operating context (e.g., Budget 2012 reductions affecting EC regional staff). The degree to which key components of the management framework have been implemented are discussed below.

- Streamlining processes to ensure national consistency. The national coordinating unit has the mandate to foster national consistency. Given the nature of the funding of the EDF program (i.e., the amount, timing and nature of awards are unpredictable), most key informants agree that some flexibility in the program is highly desirable (e.g., calls for proposals timed to coincide with the flow of monies from awards). However, some key informants feel that national consistency of the program could be enhanced. That is, while the regions share some common core tools (e.g., eligibility criteria, application form), other processes, such as how funding recipients are engaged, as well as outreach to and involvement of other departments, vary significantly from region to region. An EDF Managers Team, composed of NCR and regional managers, meets monthly via teleconference to address program management issues and foster consistency of program delivery.

- Improving accessibility for potential funding recipients. The EDF is reasonably accessible for potential funding recipients, due for example to the program’s promotional efforts (discussed below). The profile of current recipients indicates that the vast majority of funding recipients are environmental or other non-governmental organizations (75 per cent). There are very few universities, provincial/municipal or Aboriginal organizations that are leading projects, though this was not raised as problematic for the program. Seven in ten funding recipients had heard of the EDF through outreach by EC/EDF staff or the website and six in ten agree that it was easy to find information about the EDF calls for proposals (see Table 1 in Annex 3).

- Developing a promotional strategy to engage stakeholders. Efforts to enhance promotion of the EDF to stakeholders included the development of regional fact sheets for each region for distribution to enforcement personnel and groups eligible for EDF funding, and improvements to the EDF website, including the addition of success stories and a section aimed at informing the legal community. Interview findings indicate that promotional activity at the regional level is variable, with some regions reportedly engaging stakeholders very effectively and other program key informants feeling this is an area in need of improvement. The changes to the program have reportedly delayed the development of communications tools. Enforcement personnel and Crown prosecutors surveyed have typically become aware of the EDF through their respective enforcement/legal communities, but there is only modest agreement that information about the EDF is easy to find and that EC does a good job of engaging the enforcement and legal communities to raise the profile of the EDF and communicate its benefits (see Tables 3 and 6 in Annex 3). Comments from enforcement officials and Crown prosecutors surveyed indicate a strong desire for more information and transparency about the program.

- Obtaining administrative funds. Although a challenge for the program historically had been obtaining sufficient administrative resources for the program, which had resulted in limited implementation of the program, Footnote 32this has been addressed because the program received more resources. As noted earlier in Section 2.4, expenditures on EDF program administration from 2008-2009 to 2012-2013 totalled approximately $988,000. In addition, the program has developed draft guidelines for the potential use of a portion of award monies for administrative purposes (where the legislation allows this). Despite the fact that both the EEA (2009) and EVAMPA include provisions to allow funds directed to the EDF to be used by the Department for administration, this provision has never been used, and several internal and external key informants (enforcement, Crown prosecutors) feel that to do so would undermine the integrity of the program with the legal community.

| Evaluation Issue: Performance | Rating |

|---|---|

| 10. Is the EDF Program undertaking activities and delivering products in the most efficient manner? | Opportunity for improvement |

Results related to program efficiency are mixed. At the project level, leveraging of EDF funding is strong and the majority of funded projects are also sustainable in at least some respect. The administrative ratio of the program is higher than that for some EC Gs&Cs programs recently evaluated, though this can be partially explained by the additional work of the program in assessing and tracking financial awards. Key informants, however, noted several aspects of the program that detract from efficiency, including internal processes related to assessment of funds even for small-value awards, and inefficient approval and reporting processes (related to the former dual responsibility centres for the program). Moreover, as discussed earlier under evaluation question 8, roles and responsibilities for the transfer and tracking of EDF financial awards are currently unclear which leads to inefficiencies. The efficiency of the national R&D component was praised by some and questioned by others.

Leveraging