Learn about hurricanes: post-tropical cyclones

When American National Hurricane Center (NHC) forecasters declare that a tropical cyclone has become “extratropical,” they mean that it has mostly transitioned or moved beyond a purely tropical stage to become something more like an extratropical cyclone. At this point, the NHC stops issuing messages about the storm, because the NHC is a specialized forecasting centre focused on cyclones that are almost purely tropical. Because the NHC is the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) authority for naming tropical cyclones in the Atlantic basin, other weather agencies cannot continue to refer by name to a storm that has been declared by NHC to be extratropical. In these cases, the remaining weather system is referred to as “the remnants” of the tropical cyclone, or an “ex-tropical cyclone.”

This rule has caused a number of perceptual problems in Canada because many people believe that “remnants” or an “ex” tropical cyclone means that the storm now poses less of a threat. In fact, these “remnant” weather systems can still bring severe or extreme weather, just not weather of a purely tropical nature. The reality is that most of Canada’s worst tropical cyclone disasters have come from these “remnant” systems that have become more extratropical than tropical. However, by inadvertently implying that a transitioning tropical cyclone was less threatening, this de-naming practice actually increased the vulnerability of the public.

In addition, declaring that a tropical cyclone has become “extratropical” has its own set of problems. First, an extratropical cyclone is a specific type of cyclone with a particular structure and geometry. In many cases, transitioning tropical cyclones have not become fully extratropical when they are declared to be so; they are a kind of hybrid. Studies have shown that tropical cyclones entering mid-latitudes seldom lose all of their tropical characteristics. They usually keep enough moisture and circulation higher up in the atmosphere to significantly energize the resulting (or even new) extratropical cyclone into something more intense than would have otherwise occurred. This was the case with Hurricane Hazel in 1954.

An attempt for clearer communication

In a straw poll done in the late 1990s, Canadians were asked the meaning of the following phrase: “A tropical storm is becoming extratropical.” The answers showed that there were serious public misunderstandings. One respondent said, “that must mean that the cyclone is getting worse … it’s becoming EXTRA tropical.” Another respondent asked, “does that mean that there will now be two of them … an EXTRA tropical cyclone?” The best response, although still inaccurate, was, “it means that the tropical cyclone is moving from the tropics into the extratropics.” None of the existing terms helped: “extratropical”, “remnant cyclone”, “ex-tropical cyclone.”

In 1998, during messages issued on Tropical Storm Bonnie, Canada began using the term “post-tropical” when the NHC declared Bonnie to be extratropical. With this convention, a potentially dangerous storm could be called post-tropical and its name could still be used. In essence, the term “post-tropical cyclone” simply means that the cyclone used to be tropical; no other meteorological assumptions are made, such as whether it is extratropical, non-tropical or even subtropical. Through continued use and public awareness efforts, this new naming practice has been accepted and has greatly helped communications with the public.

Since 2000, there have been a few post-tropical cyclones which have brought extreme record-setting weather to eastern Canada:

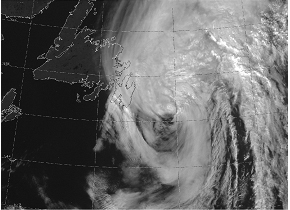

Gabrielle, 2001 (flooding rains to the Avalon Peninsula of Newfoundland).

Photo: NOAA

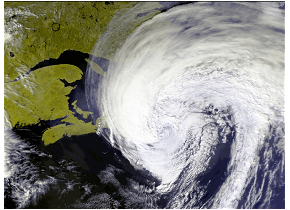

Florence, 2006 (hurricane-force winds to southern Newfoundland).

Photo: NASA

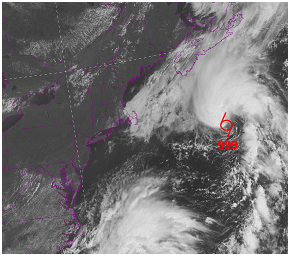

Chantal, 2007 (flooding rains to Newfoundland).

© Environment Canada , 2009

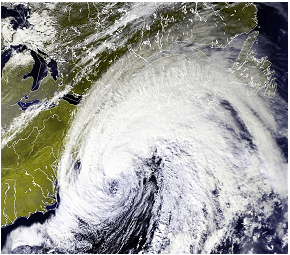

Noel, 2007 (extreme waves and coastal damage in Nova Scotia).

Photo: NASA