Canadian Protected Areas Status Report 2012 to 2015: chapter 2

Chapter 2: Protected Area Planning and Establishment

- Conservation and protected area targets

- Protected areas legislation

- Conservation and protected area strategies

- Network Planning

- Intergovernmental collaboration on network and transboundary planning

- Objectives for protected areas planning

- Protecting representative areas

- Conservation of biological diversity

- Conservation of large, intact or unfragmented areas

- Efforts to maintain ecological integrity

- Preserving habitat connectivity

- Efforts to conserve ecosystem services

- Protecting freshwater

- Protected area planning with respect to climate change

- Availability of information and resources to support protected area design

- Challenges to protected area planning and establishment

- Protecting private lands

Canada has a long history of planning and establishing Protected Areas. Canada established its first park in 1876 at Mont Royal in Montreal, Quebec. Nine years later, in 1885, Banff National Park was established in Canada's Rocky Mountains. These early recreation parks were soon complemented by the establishment of Canada's first conservation reserve: in 1887 a portion of land and water at Last Mountain Lake, in what is now Saskatchewan, was set aside as a refuge for "wild fowl". Then, in 1893, Algonquin, in Ontario, was established as Canada's first provincial park. Over time, legislative and regulatory amendments have resulted in the majority of these important places being brought under the umbrella of "protected areas" - clearly defined areas managed in order to achieve the long term conservation of nature through legal or other effective means. Recreation, education, and ecotourism are important activities in many protected areas.

Conservation and protected area targets

In February 2015, Canada adopted a suite of objectives for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. The 2020 Biodiversity Goals and Targets for Canada were developed collaboratively by federal, provincial and territorial governments. They build on the Canadian Biodiversity Strategy and the Biodiversity Outcomes Framework and highlight Canada's biodiversity-related priorities for the coming yearsFootnote1. The goals and targets are for Canada as a whole and progress will be reported at the national level. The contribution of each jurisdiction may vary, but all governments and sectors of society can make a significant contribution to overall progress. Many provinces and territories have their own biodiversity strategies and initiatives that support the national level goals and targets.

The goals and targets focus on a range of issues, including, among others, the following:

- Conservation of terrestrial and marine areas

- Protection and recovery of species at risk

- Conservation and restoration of wetlands

- Improving aquatic ecosystem health

- Managing invasive alien species

- Protecting the customary use of biological resources by Canada's Indigenous Peoples

- Promoting the sustainable use of biological resources by commercial sectors that depend on biodiversity

- Enhancing scientific understanding of biodiversity and measures of ecosystem services

- Enabling traditional knowledge to inform decision-making

- Mainstreaming biodiversity into municipal planning and school curricula

- Encouraging public awareness of, and participation in, biodiversity conservation

Canada's national goals and targets support the global Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 which was adopted by Canada and other Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity in 2010. Both the national targets for Canada and the global Aichi Targets, which form the basis of the Strategic Plan, include commitments related to area-based conservation, including protected areas.

Canada's national Target 1 is:

By 2020, at least 17 percent of terrestrial areas and inland water, and 10 percent of coastal and marine areas, are conserved through networks of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures.

The Convention on Biological Diversity global Aichi Target 11 is:

By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water, and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes.

The qualitative elements in Aichi Target 11 (including emphasis on areas of importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, effective and equitable management, ecological representation, connectivity and integration into wider landscapes and seascapes) are counted among the many objectives of protected areas organisations in Canada. These qualitative elements are also recognized in the implementation guidance for Canada's Target 1 and they form the basis for the structure of this Report.

Within Canada a number of provinces and territories have their own area-based conservation targets. In addition to the national targets, two provinces set new objectives in the period from 2012-2015. These complement existing targets that were adopted in previous periods (Table 4).

| Province | Targets | Date of adoption | Target date |

|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 12% of terrestrial area | 1993 | 2000 |

| Manitoba | 12% of natural regions | 1993 | No date |

| Nova Scotia | 12% of terrestrial area | 2007 | 2015 |

| Nova Scotia | Additional 1% beyond 12% (i.e. 13%) of terrestrial area | 2015 | No date |

| Ontario | 50% of Far North terrestrial areas and inland waters | 2010 | No date |

| Prince Edward Island | 7% | 1991 | No date |

| Quebec | 12% of terrestrial area | 2011 | 2015 |

| Quebec | 10% of marine area | 2015 | 2020 |

| Quebec | 20% of the Plan Nord area | 2015 | 2020 |

| Quebec | 50% of the Plan Nord area | 2015 | 2035 |

| Saskatchewan | 12% in each of 11 ecoregions | 1997 | 2000 |

| Canada | 17% of terrestrial areas and inland waters | 2015 | 2020 |

| Canada | 5% of coastal and marine areas | 2015 | 2017 |

| Canada | 10% of coastal and marine areas | 2015 | 2020 |

Several provinces and territories and the federal government made specific commitments during the 2012-2015 period that will contribute to achieving provincial and territorial and/or national targets (Tables 5 and 6).

- Alberta committed to establishing or expanding 18 protected areas covering an area of 13 271 km2

- British Columbia has committed to four conservancies under the Atlin-Taku Land Use Plan and is exploring opportunities to increase protection in the South Okanagan. The province also expects that some areas may be established through agreements with First Nations communities and it continues to acquire smaller areas of private land with high conservation value for protection. British Columbia also collaborated with 17 First Nations under the Marine Plan Partnership for the North Pacific Coast on developing marine use plans for the North Pacific Coast. The plans identify Protection Management Zones that cover 16 278 km2and will help to conserve and/or protect the range of values that marine environments provide with a primary emphasis on maintaining marine biodiversity, ecological representation, and special natural features. The appropriate policy and legal instruments for achieving their objectives will be determined during plan implementation, and could include, for example, the establishment of protected areas.

- Manitoba released Places to Keep: Manitoba's Protected Areas Strategy, a public consultation document to solicit the public's input into the Manitoba government's proposed goal of protecting an additional six percent of the province, raising the current area protected to 17% by 2020.

- Northwest Territories began consultations on a plan to complete eight existing candidate protected areas. The total area to be protected will be determined through ongoing discussions on the boundaries of these areas.

- In 2013, Nova Scotia released “Our Parks and Protected Areas - A Plan for Nova Scotia”. In December 2015, Nova Scotia Ministers of Natural Resources and Environment were jointly mandated to achieve an additional one percent (above the 12 percent goal in the Environmental Goals and Sustainable Prosperity Act), primarily through the addition of other parcels with no negative recreational or economic effects.

- To mark the second launch of the Plan Nord, Quebec announced the protection of a significant portion of the Kovik River watershed (4 651km2) in 2015. In the same year, Quebec announced additions to several existing protected areas in the Broadback River region as a result of the Baril-Moses forest dispute resolution agreement which added 5 436 km2 to the existing 3 698km2 of protected areas for a total of 9 134km2. Under its marine strategy, Quebec has committed to protecting 10% of the estuary of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by 2020. A number of marine protected areas projects are also being discussed by the Bilateral Group on Marine Protected Areas including sites in Gaspésie, Banc des Américains, Îles-de-la-Madeleine and the St. Lawrence River Estuary. Other project study areas are being determined.

- Saskatchewan has identified candidate protected areas through the Nisbet Integrated Forest Land Use Plan and is working to establish a new provincial park in the Porcupine Hills area of Saskatchewan. This would consolidate five small Recreation Sites and surrounding Crown land into one area 300 km2 in size.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada is working toward the establishment of five new marine protected areas: Hecate Strait/Queen Charlotte Sound Glass Sponge Reefs, Anguniaqvia niqiqyuam, St. Anns Bank, Laurentian Channel and Banc des Américains (in collaboration with Quebec). Collectively, these areas are anticipated to cover approximately 21 754 km2.

- Parks Canada is working toward the establishment of two new national marine conservation areas: Lancaster Sound which would protect an area of over 44,000 km2, in collaboration with Nunavut and Inuit, and Southern Strait of Georgia in collaboration with British Columbia, which could protect up to 1 400 km2. Parks Canada and Quebec are also working on a marine protected area project around the Îles-de-la-Madeleine, with an extent that has yet to be determined.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada is working toward the establishment of Edéhzhíe National Wildlife Area in Northwest Territories, which would protect an area of 14 250 km2, and Scott Islands marine National Wildlife Area in British Columbia, which would protect an area of 11 546 km2.

Current terrestrial protected areas establishment projects that are anticipated to be completed by 2020 could result in the percentage of Canada's terrestrial area recognized as protected rising from 10.6% to 11.8%.

| Jurisdiction | Name of Proposed Area | Area (km2) | Percent of Canada's Terrestrial Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Edéhzhíe National Wildlife Area | 14 250 | 0.14% |

| Parks Canada | Rouge National Urban Park | 79 | <0.01% |

| Parks Canada/Northwest Territories | Thaidene Nene | 34 000 | 0.34% |

| Alberta | (multiple) | 13 271 | 0.13% |

| British Columbia | Atlin - Little Trapper Conservancy | 56 | <0.01% |

| British Columbia | Atlin - Kennicott Conservancy | 6 | <0.01% |

| British Columbia | Atlin - Nakina-Inklin Conservancy | 1 007 | 0.01% |

| British Columbia | Atlin - Sheslay River | 136 | <0.01% |

| British Columbia | Ancient Forest/Chun T’oh Whudujut Park and Protected Area | 119 | <0.01% |

| British Columbia | Okanagan Mountain Park | 3 | <0.01% |

| British Columbia | Prudhomme Lake Park | 1 | <0.01% |

| British Columbia | Sheemahant Conservancy | 1 | <0.01% |

| British Columbia | Okanagan Falls Park | 1 | <0.01% |

| British Columbia | Tweedsmuir Park | 1 | <0.01% |

| New Brunswick | Green River South Protected Natural Area | 9 | <0.01% |

| Nova Scotia | (multiple) | 400 | <0.01% |

| Northwest Territories | Dinàgà Wek'èhodì | 790 | 0.01% |

| Northwest Territories | Ts'ude niline Tu'eyeta | 15 000 | 0.15% |

| Northwest Territories | Ejié Túé Ndáde | 2 177 | 0.02% |

| Northwest Territories | Łue Túé Sųlái | 180 | <0.01% |

| Northwest Territories | Ka'a'gee Tu | 9 600 | 0.10% |

| Northwest Territories | Sambaa K'e | 10 600 | 0.11% |

| Nunavut | Agguttinni Territorial Park | 17 126 | 0.17% |

| Nunavut | Nuvuk Territorial Park | 9 | <0.01% |

| Nunavut | Napurtulik Territorial Park | 896 | 0.01% |

| Nunavut | Sanikiluaq Territorial Park | 6 | <0.01% |

| Saskatchewan | (multiple) | 300 | <0.01% |

| Saskatchewan | Land use planning designations | 315 | <0.01% |

| Yukon | Dàadzàii Vàn | 1 525 | 0.02% |

| Yukon | Whitefish Wetlands | 468 | <0.01% |

| - | Total | 122 332 | 1.2% |

| - | - | Percent of Canada's terrestrial area that will likely be protected by 2020 | 11.8% |

Current marine protected areas establishment projects that are anticipated to be completed by 2020 could result in the percentage of Canada’s conserved coastal and marine areas rising from the current 0.9% to 2.3%. To meet the Government of Canada's commitment to protect 5% of marine and coastal areas by 2017 and 10% by 2020, efforts are underway to identify additional candidate areas for protection.

| Jurisdiction | Name of Proposed Area | Area (km2) | Percent of Canada's Marine Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enivronment and Climate Change Canada | Scott Islands marine National Wildlife Area | 11 546 | 0.21% |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | Hecate Strait/ Queen Charlotte Sound Glass Sponge Reefs | 2 410 | 0.04% |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | Anguniaqvia niqiqyuam | 2 361 | 0.04% |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | St. Anns Bank | 4 364 | 0.08% |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | Laurentian Channel | 11 619 | 0.20% |

| Collaboration between Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Quebec | Banc des Américains | 1 000 | 0.02% |

| Parks Canada | Lancaster Sound | 44 300 | 0.77% |

| British Columbia | Halkett Bay Marine Park | 1 | 0.00% |

| - | Total | 78 309 | 1.4% |

| - | - | Percent of Canada's marine area that will likely be conserved by 2020 | 2.3% |

Protected areas legislation

Every jurisdiction in Canada (the federal government, provinces and territories) has legislative tools that enable the creation of protected areas. These are diverse and include national parks, provincial parks, wildlife areas, conservation areas, heritage rangelands, private nature reserves, Indigenous protected areas, sanctuaries, and marine parks to name but a few. At present count, there are 53 separate Acts that are used, or could be used to establish terrestrial and marine protected areas in Canada (Table 7). Dual-designation is sometimes used to achieve conservation goals in cases where one Act is not sufficient to protect all the values at a site.

In Canada, the federal, provincial, and territorial governments establish protected areas using legislative authority created for this purpose. These jurisdictions have developed a broad suite of legislative and regulatory tools to aid in the establishment and management of protected areas. Nunavut is currently in the process of updating this legislation. The federal government, British Columbia, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia and Quebec have specific legislation for the establishment of marine protected areas or legislation that enables protection of the marine environment through the establishment of terrestrial protected areas that extend into coastal waters.

| Jurisdiction | Types of Protected Areas | Number of Acts |

|---|---|---|

| Federal | 6 | 6 |

| Alberta | 8 | 3 |

| British Columbia | 6 | 5 |

| Manitoba | 6 | 7 |

| New Brunswick | 2 | 2 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 5 | 4 |

| Northwest Territories | 3 | 2 |

| Nova Scotia | 4 | 5 |

| Nunavut | 1 | 2 |

| Ontario | 4 | 3 |

| Prince Edward Island | 3 | 3 |

| Quebec | 14 | 5 |

| Saskatchewan | 10 | 5 |

| Yukon | 5 | 3 |

| Total | 77 | 53 |

Conservation and protected area strategies

Strategies for protected areas jurisdictions are useful for setting programmatic direction. They are used to set the context for network planning thus enabling planners and the public to see the bigger picture and enable a better understanding of the proposed vision, goals, and objectives.

- Eleven out of 13 provinces and territories (85%) had a systematic strategy or framework in place for the development and implementation of a network of terrestrial protected areas (Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Northwest Territories, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Quebec and Saskatchewan).

- Manitoba, Ontario and Northwest Territories are currently updating their strategies, and Nunavut has a framework in development.

- Six out of 11 provinces or territories (55%) with a strategy or framework in place indicate that their network strategy or framework has been substantially implemented, while the remainder indicate partial implementation (Figure 8).

- To ensure a coordinated effort to marine protected area establishment and management within the Government of Canada, planning by all three federal protected areas jurisdictions is guided by the Federal Marine Protected Areas Strategy. In addition, the National Framework for Canada's Network of Marine Protected Areas provides overarching direction for Canada's national network of marine protected areas.

AB: Alberta, BC: British-Columbia, MB: Manitoba, NB: New-Brunswick, NL: Newfoundland and Labrador, NT: Northwest Territories, NS: Nova Scotia, NU: Nunavut, ON: Ontario, PE: Prince Edward Island, QC: Quebec, SK: Saskatchewan, YT: Yukon, ECCC: Environment and Climate change Canada, PCA: Parks Canada Agency, DFO: Department of Fisheries and Oceans

j Some results for 2006 and 2011 have been updated based on more accurate information.

| Years | AB | BC | MB | NB | NL | NT | NS | NU | ON | PE | QCk | SK | YT | ECCC | PCA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | S | S | S | S | P | P | P | Ø | S | P | Revised | S | Ø | P | S |

| 2011 | P | S | S | S | P | P | P | Ø | S | P | S | S | Ø | P | S |

| 2006 | P | S | P | P | P | P | P | Ø | P | P | P | P | Ø | Ø | P |

k New, more ambitious objectives were adopted in Quebec's strategy, which was updated during the 2012-2015 period.

| Years | BC | MB | NB | NL | PE | QC | ECCC | DFO | PCA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | P | S | X | X | X | P | Ø | P | P |

| 2011 | P | S | X | X | X | P | Ø | P | P |

| 2006 | X | X | X | X | X | P | X | X | X |

| Types | Values |

|---|---|

| F | Fully implemented |

| S | Substantially implemented |

| P | Partially implemented |

| Ø | No strategy in place |

| X | No data available |

| Revised | Rating is based on a new or revised strategy |

Long description for Figure 8

The figure shows the implementation status of protected areas strategies for each organization in 2006, 2011 and 2015. This is shown separately for terrestrial and marine protected areas. The possible statuses of implementation are: has not yet begun, partially implemented, substantially implemented or fully implemented. There is no data for the implementation status of marine protected areas in 2006.

Network Planning

In addition to site-specific protected area establishment processes and protected area strategies that relate to establishing systems of those sites, some jurisdictions undertake network planning.

Individual protected areas can be more effective at conserving biodiversity over the long-term when they are designed and managed as part of a larger network. Out of the 15 organisations, 10 (67%) have a strategy or system plan in place for the development of their network of terrestrial protected area that is based on an established ecological framework (Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Newfoundland and Labrador, Northwest Territories, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Quebec, Saskatchewan and Environment and Climate Change Canada). Each of these reported that their strategy is based on an established ecological framework.

In the marine environment at the national level, the National Framework for Canada's Network of Marine Protected Areas provides overall strategic direction for marine protected area network development throughout Canada's oceans and Great Lakes. The Framework and its implementation are coordinated by Fisheries and Oceans Canada with involvement from Environment and Climate Change Canada and Parks Canada, and provincial and territorial partners. The National Framework for Canada's Network of Marine Protected Areas includes the following goals:

- To provide long-term protection of marine biodiversity, ecosystem function and special natural features;

- To support the conservation and management of Canada's living marine resources and their habitats, and the socio-economic values and ecosystem services they provide;

- To enhance public awareness and appreciation of Canada's marine environments and rich maritime history and culture.

In addition to national marine protected area network development efforts, some organisations have their own specific network development processes. Strategies or planning frameworks were also in place for three out of nine organisations reporting on marine protected areas (Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Quebec, and British Columbia).

The difference between network planning and system planning

The terms "network planning" and "system planning" are used sometimes interchangeably through the Report. A system is essentially a collection of individual sites managed separately but presented as a whole for reporting or planning purposes. A network is a collection of sites that operate collectively and synergistically and were established and are managed to fulfil ecological aims more collectively and comprehensively than individual sites could alone. A National Framework for Canada's Network of Marine Protected Areas provides strategic direction for the creation of a marine protected areas network. No comparable strategic framework exists for terrestrial protected areas at the national level. Within each jurisdiction there exist planning frameworks for the establishment of sites. These often lead to the creation of a system of protected areas. Parks Canada has a system plan to guide the establishment of National Parks, for example.

Intergovernmental collaboration on network and transboundary planning

Most collaboration between governments on protected areas occurred between the federal government and individual provincial or territorial governments, as well as with Indigenous governments particularly in the establishment of new protected areas (Chapter 4 describes in further detail collaboration between federal, provincial, territorial and Indigenous governments on protected areas). A smaller number of collaborations occur between adjacent provinces and/or territories and between the federal government and the United States in establishing or managing interprovincial or international transboundary protected areas (Table 8).

- The majority of organisations (12 out of 15) reporting on terrestrial protected areas indicated that they were actively collaborating or partnering with other governments on network planning in some way including:

- Collaboration between the federal government, Government of Northwest Territories, various First Nations governments, non-governmental environmental organisations and industry, on the Northwest Territories Protected Areas Strategy, a community-based process to establish a network of protected areas across the Northwest Territories. The strategy will be collaboratively adapted as a result of the new administration realities arising from the devolution of land and resources in 2014.

- Network planning for conservation areas in southwest Saskatchewan through the South of the Divide Conservation Action Plan which was being undertaken in collaboration with federal and provincial government departments, non-governmental organisations, local communities, industry and other stakeholders.

- Collaboration between provincial authorities and Parks Canada on various transboundary conservation initiatives including, for example, the Beaver Hills Initiative, which was recently designated as a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Biosphere Reserve.

- Manitoba was consulting with Parks Canada on establishing a protected area that would increase habitat connectivity with Wapusk National Park, providing additional protection for polar bear denning areas and habitat for other species. Manitoba was also working with Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation on land use planning for their Resource Management Area which may result in protected areas that will contribute to Manitoba's protected areas network.

- Nova Scotia was consulting with Parks Canada and with Environment and Climate Change Canada on Nova Scotia's 2013 Parks and Protected Areas Plan, influencing the selection of areas next to National Parks or hosting seabird colonies. Nova Scotia reported that it was discussing potential protection of certain surplus federal coastal and island properties with Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Environment and Climate Change Canada. Nova Scotia also reported that it was also working with Environment and Climate Change Canada on the development of habitat conservation strategies.

- Ontario was consulting with the Canadian Parks Council on climate change adaptation strategies, ecosystem valuation approaches for protected areas, and consistent reporting on visitation and expenditures.

- Prince Edward Island was consulting with the Nature Conservancy of Canada and Environment and Climate Change Canada on the Maritime Provinces Habitat Conservation Strategy.

- Yukon was consulting with First Nation governments to establish individual protected areas.

- Eight out of 15 organisations reporting on terrestrial protected areas (53%) indicated that they were partnering or collaborating, or continuing ongoing collaborations, with adjacent provincial or territorial governments on interprovincial or interterritorial protected areas, or with the United States government or the government of individual states on international transboundary protected areas. Collaboration reported between provinces and territories included:

- Nunavut and Northwest Territories collaborated on the Thelon Wildlife Sanctuary

- British Columbia with Alberta on Kakwa-Willmore Interprovincial Park. The park includes Kakwa Wildland Provincial Park and Willmore Wilderness Park in Alberta side and Kakwa Provincial Park in British Columbia.

- Alberta with Saskatchewan on Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park.

- During the reporting period, Manitoba and Ontario collaborated with five First Nations--Bloodvein, Little Grand Rapids, Pauingassi, Pikangikum and Poplar River--on the Pimachiowin Aki World Heritage Site project, which has led to the establishment of new protected areas

- Six out of nine organisations reporting on marine protected areas (67%) were actively collaborating or partnering with other governments on network planning, including:

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada collaborated with federal, provincial and territorial organisations working on marine conservation under the auspices of the National Framework for Canada's Network of Marine Protected Areas, which provides the overarching direction for bioregional networks of marine protected areas in Canada's oceans and Great Lakes.

- Prince Edward Island collaborated with Fisheries and Oceans Canada for the Basin Head Marine Protected Area.

- British Columbia collaborated with 17 First Nations under the Marine Plan Partnership for the North Pacific Coast on developing marine use plans for the North Pacific Coast.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada is consulting with British Columbia on the proposal to establish Scott Islands marine National Wildlife Area.

- Parks Canada is collaborating with Nunavut and the Qikiqtani Inuit Association on the establishment of the proposed Lancaster Sound National Marine Conservation Area.

- Marine protected areas proposals in Quebec have been discussed since 2007 through the Bilateral Group on Marine Protected Areas. This group, which is coordinated by Quebec's Ministère du Développement durable, de l'Environnement et de la Lutte contre les changements climatiques and Fisheries and Oceans Canada, brings together the ministère de l'Énergie et des Ressources naturelles, le ministère de l'Agriculture, des Pêcheries et de l'Alimentation, le ministère des Forêts de la Faune et des Parcs, Environment and Climate Change Canada, and Parks Canada.

- Two organisations reporting on marine protected areas (British Columbia and Fisheries and Oceans Canada) were partnering or collaborating with other governments on transboundary conservation initiatives.

| Biome | Project / Network | Partners | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terrestrial/Freshwater | Crown Managers Partnership | British Columbia, Alberta, Montana, Idaho, Parks Canada | This American-Canadian partnership aims to improve the management of the Crown of the Continent ecosystem by addressing issues across this landscape in a collaborative manner and including with First Nations. |

| Terrestrial/Freshwater | Washington Wildlife Habitat Connectivity Working Group | British Columbia with Washington State | A collaboration to model the movements of wildlife from Washington State into British Columbia. |

| Terrestrial/Freshwater | Kluane/Glacier Bay/Tatshenshini-Alsek complex | British Columbia, Parks Canada and the US Forest Service | A World Heritage Site and complex made of four large protected areas on both sides of the Canadian and American border. This complex is being managed in collaboration with First Nations. |

| Terrestrial/Freshwater | E. C. Manning/Cascade complex | British Columbia and Washington State | The southern boundary of E. C. Manning Park borders the North Cascades National Park in the United States while the Skagit Valley Provincial Park is adjacent to the western boundary of E. C. Manning. Together these protected areas form a large block of habitat which may help to sustain the North Cascades grizzly bear population, which is present on both sides of the US-Canadian border. |

| Marine | The North American Marine Protected Areas Network through the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (various projects) | Federal jurisdictions (Parks Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada), US and Mexico federal governments (British Columbia is a collaborator on some projects) | Race Rocks Ecological Reserve (in collaboration with British Columbia) |

| Marine | North Pacific Landscape Conservation Cooperative | British Columbia, US Federal Government, Canadian Federal Government, First Nations as well as academic institutions and non-governmental organisations. | This collaborative partnership fosters information sharing and coordination for conservation and sustainable resources management along the North Pacific Landscape from California to Alaska. A priority theme for the group is climate change and its effects including changes in sea levels and storms on marine shorelines, the nearshore and estuaries. |

| Marine | Framework for a Pan-Arctic Network of Marine Protected Areas | Various federal jurisdictions (including Fisheries and Oceans Canada), collaborate to fulfill the role of Canada as a member state of the Arctic Council. | The Framework for a Pan-Arctic Network of Marine Protected Areas was drafted by an MPA Network Expert Group reporting to the Arctic Council's Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment Working Group (PAME). The Expert Group was co-led by Canada, Norway, and the United States; all Member States of the Arctic Council were active participants. The framework was published in April 2015 and sets out a common vision for international cooperation in MPA network development and management, based on best practices and previous Arctic Council initiatives. The Arctic Council is now undertaking to implement the Framework by developing an inventory of Pan Arctic MPAs and addressing the issue of trans-boundary connectivity. |

Objectives for protected areas planning

Protected areas planning objectives flow from the mandate and vision for a protected areas system. They are a statement of purpose that describe future expected outcomes or states and provide programmatic direction. The range of objectives for protected areas planning in Canada reflects the diversity of landscapes and habitat found across the country, the pressures on ecosystems, and the conservation opportunities that exist. The bullet points below summarize the objectives for protected areas planning. More detail is provided in the sections that follow.

- Protecting representative samples of their ecological areas was considered to be a primary objective for 12 of the 15 organisations reporting on terrestrial protected areas (80%). This was also considered to be a primary objective for five of nine organisations (55%) reporting on marine protected areas. Fisheries and Oceans Canada does not have site-specific objectives that relate directly to protecting representative areas, but representativity is a consideration in the context of marine protected area network development, which they lead and coordinate on behalf of the Government of Canada.

- Conservation of biological diversity was identified as a primary objective for terrestrial protected areas by 10 out of 15 organisations (67%) and either a primary or secondary objective for seven out of nine marine protected area organisations (78%).

- Nearly half (47%) of organisations reporting on terrestrial protected areas (seven out of 15) identified focusing on large, intact or unfragmented areas as a primary objective. For organisations reporting on marine areas four out of nine (44%) identified focusing on large, intact or unfragmented areas as a primary or secondary conservation objective, while five noted that it was not mentioned as an objective.

- Habitat connectivity was generally identified as a secondary objective for terrestrial protected areas by most organisations. However, habitat connectivity was a primary or secondary objective for the marine protected areas of two out of nine reporting organisations. As with considerations related to representativity, Fisheries and Oceans Canada does not have site-specific connectivity objectives, but connectivity is a consideration in national marine protected area network development where supporting scientific data is available.

- Ecosystem services were identified as a primary objective for terrestrial protected areas in Manitoba and a secondary objective in Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and by Parks Canada. Ecosystem services were noted as primary or secondary objectives by two organisations reporting on marine protected areas and were either merely mentioned or not included at all by the remainder (seven out of nine).

- British Columbia identified climate change adaptation as a primary objective for both terrestrial and marine protected areas. For other organisations reporting on terrestrial protected areas, three reported that adaptation to climate change was mentioned and six reported that it was not included at all. For organisations reporting on marine protected areas the remainder (eight out of nine) indicated that climate change adaptation was either merely mentioned or not included as an objective.

- Manitoba reported climate change mitigation as a secondary objective for terrestrial protected areas. For all other organisations reporting on terrestrial protected areas (14 out of 15), as well as for the nine organisations reporting on marine protected areas (including Manitoba), climate change mitigation was either merely mentioned or not included as an objective.

- Six out of 15 organisations reporting on terrestrial protected areas identified ecological integrity as a primary objective (40%) while two out of nine (22%) organisations reporting on marine protected areas identified ecological integrity either as a primary objective or as a secondary objective.

- Additional objectives were reported by some organisations: Environment and Climate Change Canada noted that during the 2012-2015 reporting period, connecting Canadians to nature was identified as a primary objective for ten of its National Wildlife Areas located near urban areas. Parks Canada reported that its dual mandate includes fostering opportunities for Canadians to experience and develop a sense of personal connection to, and pride for their natural heritage places through compelling visitor experiences. Northwest Territories and Saskatchewan emphasized the conservation of cultural heritage as a priority in their protected areas planning. And finally, Alberta noted that while the objectives noted here may not be explicitly referenced, they are all intended components of broader goals related to planning, establishment, design and management of protected areas in the province.

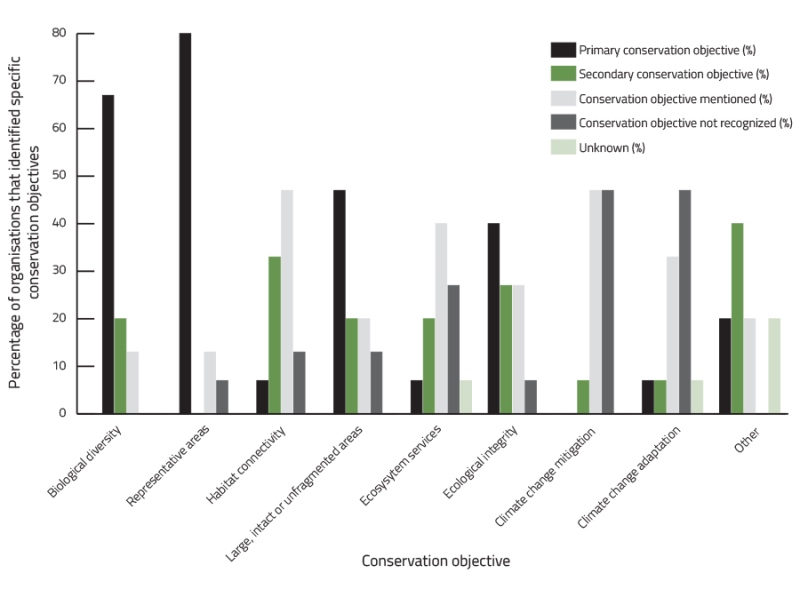

Long description for Figure 9

The bar graph shows the percentage of protected area organizations in Canada that identified specific conservation objectives as being either primary, secondary or mentioned. The conservation objectives shown are biological diversity (etc); representative areas; habitat connectivity; large, intact or unfragmented areas; ecosystem sevices; ecological integrity; climate change mitigation and climate change adaptation.

Data for Figure 9

| Conservation objective | Primary conservation objective (%) | Secondary conservation objective (%) | Conservation objective mentioned (%) | Conservation objective not recognized (%) | Unknown (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological diversity | 67 | 20 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Representative areas | 80 | 0 | 13 | 7 | 0 |

| Habitat connectivity | 7 | 33 | 47 | 13 | 0 |

| Large, intact or unfragmented areas | 47 | 20 | 20 | 13 | 0 |

| Ecosystem services | 7 | 20 | 40 | 27 | 7 |

| Ecological integrity | 40 | 27 | 27 | 7 | 0 |

| Climate change mitigation | 0 | 7 | 47 | 47 | 0 |

| Climate change adaptation | 7 | 7 | 33 | 47 | 7 |

| Other | 20 | 40 | 20 | 0 | 20 |

Identifying candidate protected areas-the role of Key Biodiversity Areas

Candidate areas for protection may include important habitat for a lifestage of one or more migratory bird populations, species at risk, or other wildlife species, may include nationally or globally significant ecosystems or natural features, they may be culturally important ecosystems or they may focus on protecting ecological processes that generate ecosystem services.

The identification of Key Biodiversity Areas has been emerging as an approach to the selection of candidate areas for protection. The International Union for Conservation of Nature defines Key Biodiversity Areas as sites contributing significantly to the global persistence of biodiversity; identified using globally standardized criteria and thresholds, and having delineated boundaries. They may or may not receive formal protection, but should ideally be managed in ways that ensure persistence of the biodiversity (at genetic, species, and/or ecosystem levels).

Key Biodiversity Areas in Canada could include, as a starting point, habitat necessary for the recovery of species at risk (referred to as critical habitat in Canada) and areas where migratory birds are found in significant aggregations. Critical habitat is described in the recovery plans for species that are listed under the Species at Risk Act in Canada. Areas that are important to migratory birds - places where migratory birds concentrate for all of, or a portion of the year - are identified through regular monitoring and field investigation by federal, provincial and territorial biologists and private citizens with an interest in conservation and migratory birds. The Canadian Important Bird Areas (IBA) program has been one approach used in Canada to identify areas of importance to migratory birds.

Protecting representative areas

During the 2012-2015 period, protected area organisations continued to focus on protecting representative samples of their ecological areas.

- Twelve out of the 15 organisations reporting on terrestrial protected areas (80%) identified representative areas as a primary conservation objective within their protected area legislation, policies, plans or strategies. This is an increase from the 65% of protected areas organisations that recognized protecting representative areas as a primary objective at the end of 2011.

- Nine out of 15 organisations (60%) indicated that objectives, indicators or targets for representativeness had been identified for most or all of their terrestrial protected areas while three out of nine organisations (33%) reporting on marine areas indicated objectives, indicators or targets for representativeness had been identified.

- 10 out of 15 organisations reporting on terrestrial protected areas (67%) and six out of nine organisations reporting on marine protected areas (67%) indicated that scientific information to support protecting representative areas was either substantially or fully available. In addition, for terrestrial protected areas , four organisations (27%) indicated that such information was only partially available, while for marine protected areas, this was the case for three organisations (33%).

- Just 24% of protected areas organisations indicated that they undertake routine assessment and regular reporting on progress in achieving their conservation objectives related to representative areas. This includes four out of 15 organisations reporting on terrestrial protected areas (27%) and two out of nine organisations reporting on marine protected areas (22%).

Conservation of biological diversity

Biological diversity includes genetic diversity within species, the number and extent of viable populations, hot spots for biodiversity, species at risk, community structure, ecosystem diversity, and ecosystem resilience to name a few factors.

The conservation of biological diversity continues to be a recognized objective for many protected area organisations and within their mandate, goals, or objectives of legislation, policies, plans, or strategies:

- With respect to terrestrial protected areas,

- Thirteen organisations reporting on terrestrial protected areas (87%) recognize biological diversity as being of primary (67%) or secondary (20%) importance.

- However, only three (20%) have mostly or fully identified objectives, indicators, or targets with respect to the conservation of biological diversity, while eight (53%) have partially identified these objectives, indicators or targets.

- In the marine environment,

- The importance of biodiversity conservation is similar to that reported in terrestrial protected areas with six of nine organisations reporting on marine protected areas (67%) recognizing conservation of biodiversity as being of primary importance and one organisation recognizing conservation of biodiversity as being of secondary importance.

- However, in contrast to terrestrial reporting, in the marine environment, four organisations out of nine (44%) have fully identified objectives, indicators or targets for the conservation of biological diversity.

Scientific information appears to be generally available to assist protected area organisations in establishing protected areas networks to achieve the conservation of biological diversity.

- For terrestrial protected area, six of 15 (40%) organisations report that this information is fully or substantially available and the remaining nine (60%) report that it is partially available. In particular, Saskatchewan uses data on species at risk and biodiversity to help design its Representative Areas Network.

- Similarly for the marine environment, four of nine organisations (44%) report that this information is substantially available; three other organisations report that it is partially available. Only two organisations report that scientific information related to biological diversity is not available to help design protected areas networks or systems in the marine environment.

Monitoring to evaluate progress in achieving the conservation of biological diversity is somewhat limited:

- For terrestrial protected areas, no organisations reported having a full monitoring program in place . Twelve organisations reported either sporadic monitoring or monitoring programs in some of their protected areas while three organisations reported little or no monitoring for biological diversity.

- The situation is somewhat better in the marine environment with three (33%) organisations reporting that monitoring is being undertaken at all or most protected areas. However, three (33%) organisations reported that sporadic or no monitoring is being undertaken.

Some organisations have assessed the extent to which their protected areas network effectively addresses the objective of biodiversity conservation.

- For terrestrial and freshwater protected areas networks, nine out of 15 (60%) of organisations have substantially or partially completed a gap analysis with respect to biological diversity while six out of 15 (40%) report that a gap analysis has not been conducted.

- Alberta in particular regularly considers species at risk and rare or unique landforms when assessing the effectiveness of its protected areas network.

- Newfoundland and Labrador used the results of its gap analysis to identify sites with high biodiversity or significant natural features.

- For the marine environment, four out of nine (44%) organisations have fully, substantially or partially undertaken gap analysis, while 56% of organisations reported that a gap analysis has not been conducted.

Even with the great importance placed on the conservation of biological diversity, when the gaps in the availability of scientific information and monitoring capacity are taken into account, it is perhaps not surprising that just three of 15 organisations reporting on terrestrial protected areas (20%) indicate that their protected areas network or system has been substantially completed with respect to biological diversity conservation. A further 10 out of 15 organisations (67%) report partial completion of their systems in consideration of this objective. This is similar for the marine environment where six out of nine (67%) organisations report partial completion of their networks in consideration of the biological diversity conservation objective.

Conservation of large, intact or unfragmented areas

The primary goal when designing networks or systems of protected areas is the long-term maintenance of biodiversity. The ongoing debate in conservation biology is whether or not this goal is best achieved through the creation of a single large protected area or several small connected areas. The answer is likely a combination of both but is contingent on the local context, including consideration of factors such as the size of the protected areas, land use practices in the surrounding landscape, the 'permeability' of the landscape to wildlife (rates of immigration and emigration from the various habitat patches), and the concomitant rates of local species extinction. While the optimal size of a protected area remains a subject of some debate and depends on local context, species-area research across protected areas globally shows size to be the greatest predictor of success at retaining species.

Most protected areas organisations recognize the need for large, unfragmented protected areas in their mandate, goals, and objectives of protected areas legislation, policies, or strategies; however the level of importance of this objective varies.

- For terrestrial protected areas,

- Eleven of 15 (73%) organisations recognize the conservation of large, intact or unfragmented areas as a primary (47%) or secondary (27%) objective.

- Ten of 15 (67%) organisations had mostly or partially established explicit objectives, indicators and targets for large, intact, or unfragmented habitats.

- Eight of 15 (53%) partially or substantially conducted gap analyses with respect to this objective.

- In the marine environment,

- Four out of nine (44%) organisations cite the conservation of large, intact or unfragmented areas as being a primary (33%) or secondary (11%) objective in the marine environment

- Further, in the marine environment, five organisations (56%) make no reference at all to large or unfragmented areas as a conservation objective.

- In contrast to terrestrial reporting, objectives, indicators and targets for large, intact, or unfragmented habitats have been mostly or partially established by only 22% of organisations.

- Gap analyses have been partially or substantially conducted by three out of nine organisations (30%).

All organisations reporting on terrestrial protected areas (100%) and most organisations reporting on marine protected areas (80%) indicated having scientific information available to help design their protected areas networks/systems to achieve conservation objectives related to large, intact, or unfragmented habitats.

Efforts to maintain ecological integrity

Ecosystems are considered to have integrity when their native components and processes are intact. The 2000-2005 Canadian Protected Areas Status Report noted that the majority of jurisdictions have "recognized the importance of managing their terrestrial protected areas for ecological integrity." In the 2006-2011 Report it was noted that "Canadian organisations are adopting ecological integrity as a foundation for protected areas management."

- By the end of 2015, with respect to terrestrial protected areas:

- Fourteen of 15 organisations (93%) recognized ecological integrity as a conservation objective in the mandate, goals, or objectives of terrestrial protected areas legislation, policies, plans or strategies. For six organisations (40%) ecological integrity was a primary objective; three organisations (20%) cited it as a secondary objective and the remaining four (27%) mentioned it as an objective. Only one out of 15 (7%) organisations reported that this conservation objective was "not at all" recognized.

- Objectives, indicators, or targets have been identified for ecological integrity for 10 out of 15 organisations (67%).

- Scientific information on ecological integrity appears to be sparse with 11 out of 15 organisations (73%) noting that scientific information on ecological integrity is either only partially available (60%) or the status of this information is unknown (13%).

- For marine protected areas :

- Seven out of nine organisations (78%) reported that ecological integrity was recognized as a conservation objective in the mandate, goals or objectives of the marine protected areas legislation, policies or strategies. Out of these, it was a primary objective for two organisations.

- Four out of nine (44%) organisations have identified objectives, indicators, or targets for ecological integrity.

- Most reported that scientific information on ecological integrity was limited. Five out of nine reported that information is partially available; two reported that it was not at all available, and one reported that the status of this information is unknown.

Preserving habitat connectivity

Habitat connectivity is essential for the long-term conservation of biodiversity. Local extinction rates are higher when "islands" of habitat are isolated and not connected to one another.

- For terrestrial protected areas:

- Thirteen out of 15 organisations (87%) mentioned or listed habitat connectivity as being of secondary importance in their mandate, goals, or objectives.

- Nonetheless, seven out of 15 organisations (47%) reported that objectives, indicators or targets have been partially identified with respect to connectivity.

- Most organisations reported that scientific information is available to help design protected areas networks that can achieve connectivity: 10 out of 15 (67%) report that information is partially available and 3 out of 15 (20%) report that this information is fully or substantially available.

- Manitoba in particular reported evaluating habitat connectivity where landscape-level protected areas planning processes are occurring.

- Ten out of 15 organisations (67%) indicated that little or no monitoring, or only sporadic monitoring (27%), was being actively undertaken to evaluate progress in achieving habitat connectivity objectives.

- Only Parks Canada indicated that some protected areas have an ongoing monitoring program related to habitat connectivity.

- Seven out of 15 organisations (47%) reported that they have partially or substantially undertaken gap analysis.

- Parks Canada was also the only organisation that reported having substantially undertaken a gap analysis to assess the extent to which terrestrial and freshwater protected areas networks address habitat connectivity

- Further, these gap analyses have been used to plan and complete terrestrial protected areas networks by most organisations (86%) that undertook the assessments.

- Similarly, in the marine environment:

- Just one organisation reported that connectivity is of primary importance in the mandate, goals, or objectives of their marine protected areas legislation, policies, plans, or strategies. Four organisations indicated it was either a secondary consideration, or mentioned.

- Out of five that recognized habitat connectivity, four organisations (British Columbia, Manitoba, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Parks Canada) have identified objectives, indicators, or targets with respect to habitat connectivity.

- Six out of nine organisations (67%) reported that scientific information is available to some degree to help design marine protected areas networks/systems with respect to habitat connectivity. This included the five organisations that recognize habitat connectivity (British Columbia, Manitoba, Quebec, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Parks Canada).

Saskatchewan notes that protecting large, intact, or unfragmented habitats is a key consideration when proposing the establishment of 'wilderness' and 'natural environment' parks. In this context, watershed protection has become an important consideration.

Efforts to conserve ecosystem services

Ecosystems are composed of biophysical structures and processes. These structures and processes have many functions that result in 'ecosystem services' which sustain life, providing a breadth of benefits that are of significance to individuals, groups, and society overall. Ecosystem services can be categorized and include the following (United Nations Millennium Ecosystem Assessment):

- Provisioning: water, food, fuel, fibres, medicines, and genetic resources.

- Regulating: pollination, air and water purification, and natural regulation of climate, disease, water, pests, and soil erosion.

- Supporting: soil formation, nutrient cycling, and primary production.

- Cultural: spiritual, religious, recreation, ecotourism, aesthetic, inspiration, education, sense of place and cultural heritage.

One of the many benefits of protected areas is that they help maintain the ecological processes that generate ecosystem services, however, planning and managing protected areas to conserve ecosystem services is less common. Previous versions of this report have not evaluated the extent to which ecosystem services are considered within jurisdictions responsible for protected areas.

For terrestrial protected areas:

- One organisation described ecosystem services as being of primary importance within the mandate, goals, or objectives of their protected areas legislation, policies, plans or strategies.

- Four organisationsFootnote2 (27%) cited it as being of secondary importance

- Seven out of 15 organisations (47%) mentioned ecosystem services as a conservation objective within the mandate, goals, or objectives of their protected areas legislation, policies, plans or strategies.

This recognition is nearly identical in the marine environment.

The development of objectives, indicators, or targets for ecosystem services appears to be a more difficult task.

- The majority of organisations reporting on terrestrial protected areas (13 out of 15 or 87%) have not identified any objectives, indicators or targets while only two (13%) have them partially identified.

- Just over half of organisations reporting on marine protected areas (five out of nine or 56%) did nothave any objectives, indicators or targets with respect to ecosystem services while three have them partially identified. Only one organisation (British Columbia) had fully identified objectives, indicators or targets.

It is likely not surprising, considering the numbers above, that most organisations reporting on terrestrial protected areas (93%), and many organisations reporting on marine protected areas (44%) are not evaluating progress in achieving objectives related to ecosystem services. Neither has a gap analysis been conducted in respect of ecosystem services: 13 out of 15 organisations reporting on terrestrial protected areas (87%), and seven out of nine organisations reporting on marine protected areas (78%) have not conducted any gap analyses. A lack of scientific information related to ecosystem services does not seem to be the reason why objectives, indicators, or targets have not been established: 11 out of 15 organisations (73%) report that this information is at least partially available for terrestrial protected areas and six out of nine organisations (67%) report similar findings for marine protected areas.

Protecting freshwater

The area of freshwater (lakes, rivers, streams) in Canada is estimated to be 891 000 km2 which is 9.8% of the total terrestrial area of Canada (Natural Resources Canada, 2005). This represents 20% of the world's total freshwater and 7% of the world's renewable freshwater (i.e. water that is not 'fossil water' retained in lakes, underground aquifers, and glaciers).

A number of provinces and territories protected large and significant areas of freshwater, such as rivers, lakes and wetlands, during the 2012-2015 period through the establishment or expansion of protected areas.

- In 2012, an addition to Atlin/Téix'gi Aan Tlein Park and 10 new conservancies were established in British Columbia through the Atlin Taku Land Use Plan. These areas include the main stem of the Taku River and a significant proportion of its major tributaries, the Nakina, Inklin, and Sheslay, in the northwest of the province.

- In Nova Scotia, the French River Wilderness Area, in the Cape Breton Highlands, was significantly expanded to incorporate and buffer several pristine, un-dammed, and difficult-to-access lakes. The Stillwater Wilderness Area, in eastern Cape Breton, was established and encompasses much of the drinking water watershed for the town of Louisburg. Silver River Wilderness Area was established to protect swaths of land on either side of a major branch of the Tusket River, a river system of national significance because of its unique concentration of endangered plants of the Atlantic Coastal Plain. Medway Lakes Wilderness Area was established to, in part, protect both aquatic ecosystems and wilderness recreation opportunities in a region of the province famous for its backcountry canoeing and guiding heritage.

- In 2013 Saskatchewan established two significant additions: Pink Lake Representative Area Ecological Reserve in the Churchill River Upland Ecoregion, and Great Blue Heron Provincial Park in the Mid-Boreal Upland Ecoregion, each of which are approximately 15% freshwater by total area.

- In 2013 the government of Quebec created the parc national Tursujuq in Nunavik which covers an area of 26 107 km2 making it the largest mainland park in eastern North America. The original boundaries include the second largest natural lake in Quebec. At the request of the Inuit and Cree Indigenous Peoples, the final boundaries also include almost the entirety of the Nastapoka watershed which results in the protection of a globally unique population of freshwater seals.

In addition, a number of significant commitments to protect freshwater were made during this period.

- Alberta has taken steps to establish Richardson Wildland Provincial Park in the Peace-Athabasca Delta, a wetland of global significance recognized under the Ramsar Convention. Once established, 94% of the entire Peace-Athabasca Delta will have protected area designation.

- Significant headwaters in southern Alberta and the Crown of the Continent were committed to be protected under the South Saskatchewan Regional Plan in 2014.

- An additional 416 km2 of wetlands, lakes and 101 linear km of rivers, accounting for much of the extensive freshwater that exists in the Canadian Shield-Kazan Upland sub-region in Alberta, will be protected within protected areas commitments made in the Lower Athabasca Regional Plan in 2012.

- Quebec's commitment to designate 20% of the Plan Nord region in protected areas by 2020, with an additional 30% eventually, will make a significant contribution to the protection of freshwater in the northern regions of Quebec including watersheds as well as rivers and wetlands.

Protected area planning with respect to climate change

Six provinces, territories and federal agencies have assessed the implications of climate change for terrestrial protected area planning (Alberta, Northwest Territories, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Environment and Climate Change Canada and Parks Canada) and one is in the process of doing so (British Columbia). Climate change adaptation was identified as a secondary objective in Manitoba and was either merely mentioned or not included at all in the remainder of jurisdictions. British Columbia recently revised its conservation policy to ensure park planning and management incorporates adaptation to climate change.

Availability of information and resources to support protected area design

Protected area organisations rely on various sources of information and resources to support protected area design. In some instances, some types of information have been more accessible such as remote-sensing data, now readily available and used by a majority of organisations. However, there are still important information gaps including,

For terrestrial protected areas:

- For at least 73% of organisations (11 or more out of 15), information was rated as being available to readily available for geographic information system mapping and analysis as well as for identifying or evaluating candidate areas.

- About 50% of organisations (seven out of 15) reported that spatially explicit wildlife data and information for developing models for protected area design was available.

- At the other end of the scale, a majority of organisations reported that no information or very little was available when it came to inventory and monitoring data (10 out of 15), stress assessment and indicators (11 out of 15) and traditional ecological knowledge (nine out of 15).

- Organisations were proportionally divided when it came to having access to information for identifying areas of cultural importance to Indigenous communities as well as for database design and development. About a third of organisations reported having little, or limited information.

For marine protected areas:

- Just under half of organisations reported that spatially explicit wildlife data was available. Information for geographic information system mapping and analysis and identifying or evaluating candidate areas ranged from available to readily available for at least 44% of organisations with Manitoba and Quebec appearing to have easier access to such information overall.

- For most organisations (67%), information was lacking regarding inventory and monitoring data as well as stress assessment and indicators, while appearing to be limited overall for database design and development.

- Information on traditional ecological knowledge and for identifying areas of cultural importance to Indigenous communities was rated as not being available or being limited for just over 50% of organisations. Parks Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Quebec reported having available information.

Challenges to protected area planning and establishment

Nearly all organisations reporting on protected areas in both biomes (15 out of 15 for terrestrial and eight out of nine for marine) indicated facing numerous and similar challenges to the establishment of protected areas in Canada (Table 9).

For organisations reporting on terrestrial protected areas:

- All mentioned conflicting or competing interests in use of available lands as an important barrier.

- Nine further identified the difficulty of finding suitable lands and eight identified not having the human resources needed to work on the development of protected areas networks was highlighted as main barriers.

- Additional challenges highlighted included difficulties meeting mutual interests especially when considering Indigenous communities and governments, land use planning processes and the establishment of protected areas, as well as the capacity of First Nations communities to navigate through these.

Similarly, for marine protected areas:

- For the eight organisations that identified challenges, competing interests in the use of marine areas was an important challenge reported.

- Six out of these eight organisations also mentioned not having sufficient information on natural resources inventories, and four highlighted not having enough staff to support the work for network planning as important barriers.

- Additional challenges reported include lengthy regulatory processes for establishing marine protected areas.

| Biome | Primary planning or establishment challenges / barriers | Percentage of organisations facing challenges according to each type of barrier (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Terrestrial | Conflicting/competing interest in use of available lands | 100 |

| Terrestrial | Availability of suitable lands | 64 |

| Terrestrial | Lack of staff resources for network planning | 57 |

| Terrestrial | Lack of conservation priority | 50 |

| Terrestrial | Lack of financial resources for land acquisition | 43 |

| Marine | Conflicting/competing interest in use of available marine areas | 100 |

| Marine | Lack of adequate natural resources inventories | 75 |

| Marine | Lack of staff resources for network planning | 50 |

| Marine | Availability of suitable areas | 25 |

| Marine | Lack of conservation priority | 25 |

| Marine | Lack of financial resources for land acquisition | 25 |

| Marine | Legal/policy impediments to acquisition | 25 |

| Marine | Lack of appropriate tools to regulate environment inside protected area | 25 |

Protecting private lands

Private and non-profit organisations like land trusts play an important role in securing and managing high conservation value lands that serve to complement the establishment of protected areas, particularly in southern regions of Canada. These lands generally account for less than 1% of the total area protected in southern jurisdictions. However, these private protected areas are often located on lands with significant biodiversity values. A paper published in 2015 noted that "The accounting of privately protected areas, primarily through land trusts, in Canada is incomplete, but will account for less than 0.2 % of the land base. Canada is 89 % publically owned land, and land trusts are focused in the southern 11 % of Canada, most often in areas of high importance for biodiversity."Footnote3

As noted in the previous chapter, private conservation lands are currently reported by some provinces and territories. Provincial and territorial governments are working with non-governmental groups and with Environment and Climate Change Canada to improve the recognition of privately held conservation lands as an integral component of protected areas networks. Environment and Climate Change Canada announced in 2014 that it would complete an inventory of privately held conservation lands to support this goal.

Jurisdictions have created a number of financial and other incentive programs to encourage the conservation of private lands. There are more than 160 organisations that are currently eligible to acquire lands for the purpose of conservation and many of these are private land trusts. Some of these programs and their recent conservation successes are summarized below.Footnote4

Conservation of private areas is either fully or partially recognized in the terrestrial protected areas strategies of 11 of 15 organisations (73%). Conservation of private lands is enabled through fiscal and tax incentives and through legislation in most provinces that enable the creation of private conservation reserves, or the creation of conservation easements, covenants or servitudes.

- Alberta has made a strategic commitment to establish a Parks Conservation Foundation, which would enable private citizens and corporations to donate land of high conservation value or money to support the purchase of conservation lands. Public-private partnerships are also enabling the conservation of important habitats. Approximately 41 km2 of public-land grazing lease that was stewarded by the privately held OH Ranch was designated as a Heritage Rangeland. This area is managed in conjunction with the adjacent private land which is conserved under conservation easement.

- BC Parks partners with a large number of government and non-government organisations on land acquisition. BC Parks and the Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations administer a large number of properties that are owned by non-governmental organisations or individuals and leased to the ministries to manage for 99 years. Some properties owned by the Province have similarly been leased to a local government or non-governmental organisations for management purposes. Examples of recent partnerships to acquire new private lands areas for protection are the acquisition of lands for addition to Small Inlet and Octopus Islands marine parks in funding partnership between British Columbia, the Quadra Island Conservancy and the Marine Parks Forever Society; the acquisition of lands on Denman Island using carbon credits and development density transfers; and a partnership with Regional District of Okanagan Similkameen on an addition to Okanagan Falls Park.

- Other provinces such as Ontario, Nova Scotia and Manitoba have directly supported private land conservation initiatives through direct or matching funding, or through the establishment of land acquisition trust funds. Quebec and New Brunswick have legal mechanisms to formally recognize private protected areas as designated within their protected areas system.

- Within the framework of the Partenaires pour la nature program, which ran from 2008 to 2013, the last year of the program financed 18 natural environment protection projects. In total, almost $975,000 in financial assistance was provided to six conservation organisations and seven private citizens with the goals of assuring the protection of 4.8 km2 of natural environments in southern Quebec. These acquisitions contributed to larger regional conservation projects by consolidating protection in the region, building on previous private stewardship programs.

Further incentive measures are in place to assist land trust organisations or others in the securement of private lands of ecological significance in 11 out of 13 provincial and territorial jurisdictions (85%).

- The Ecological Gifts Program, for example, administered by Environment and Climate Change Canada in cooperation with dozens of partners, including other federal departments, provincial and municipal governments, and environmental non-government organizations, offers significant tax benefits to landowners who donate land or a partial interest in land to a qualified recipient, who ensure that the land's biodiversity and environmental heritage are conserved in perpetuity. Between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2015 approximately 311 km2 of land were secured through the Ecological Gifts Program.

- The Natural Areas Conservation Program helps non-profit, non-government organisations secure ecologically sensitive lands to ensure the protection of diverse ecosystems, wildlife, and habitat. Funding is provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada and the project is administered by the Nature Conservancy of Canada who partners with conservation organisations such as Ducks Unlimited Canada and other qualified organisations. Organisations provide matching funds at a 2:1 ratio for each federal dollar received to acquire ecologically sensitive lands through donation, purchase or conservation agreements with private landowners. Priority is given to lands that protect habitat for species at risk and migratory birds and create or enhance connections or corridors between protected areas. In addition, lands may be secured that have national or provincial significance based on ecological criteria, or reduce significant land-use stressors adjacent to protected areas. Between 2012 and 2015 approximately 600 km2 of land were secured through the Natural Areas Conservation Program.

- The North American Waterfowl Management Plan is an international partnership to conserve waterfowl populations and wetlands through on-the-ground actions based on strong biological foundations. Started in 1986, program partners have worked to conserve and restore wetlands, associated uplands and other key habitats for waterfowl across Canada, the United States and Mexico. The results of these efforts are notable, with over 1 350 km2 protected in Canada between April 1, 2012 and March 31, 2015 through medium term (10-99 years) and permanent habitat retention activities (lease, acquisition, conservation easements, etc.).

- The National Wetland Conservation Fund is a five-year program that originated in 2014-2015 and is administered by Environment and Climate Change Canada. The program supports on-the-ground activities to restore and enhance wetlands in Canada, including wetlands on privately owned lands. Some of the activities funded by the Fund result in the creation of new privately-held protected areas. The objectives of the fund are to:

- Restore degraded or lost wetlands on working and settled landscapes to achieve a net gain in wetland habitat area. Between October 1, 2014 and March 31, 2015 approximately 74 km2 of wetland habitat was secured with the support of the National Wetland Conservation Fund;

- Enhance the ecological functions of existing degraded wetlands;

- Scientifically assess and monitor wetland functions and ecological goods and services in order to further the above objectives to restore and/or enhance wetlands; and

- Encourage the stewardship of Canada's wetlands by industry and the stewardship and enjoyment of wetlands by the Canadian public.

- The Habitat Stewardship Program is a Government of Canada funding program administered by Environment and Climate Change Canada that supports projects that conserve and protect species at risk and their habitats and help to preserve biodiversity as a whole. These funds promote the participation of local communities, non-government organisations, and other organisations to help with the recovery of species at risk and preventing other species from becoming a conservation concern. Between April 1, 2012 and March 31, 2015, the program contributed to the protection of 189 km2 of private land through legally-binding means such as acquisition or conservation easements.