Report on Written Submissions

On this page

- Executive summary

- Acknowledgement

- Introduction

- Consultation process

- Key findings

- Conclusion

- Appendix A: Invited parties

- Appendix B: Acronyms, abbreviations and glossary

- Appendix C: Panellists’ biographies

Executive summary

In recent years, there has been a growing awareness in the federal public service that substantial changes are needed to foster a diverse and inclusive workplace where every employee feels valued and empowered, and is protected from harassment, discrimination and violence.

In response to this reality, in Budget 2023, the Government of Canada committed $6.9 million over two years to design and develop a restorative engagement program for the federal public service. This program is intended to take concrete measures to combat root causes of harassment, discrimination and violence in the workplace.

About this report

This report summarizes the opinions expressed in online written submissions about the restorative engagement program’s desired outcomes; its structure, design and governance; as well as potential barriers to its success.

Submissions were provided by 76 parties including:

- members of networks representing employees from equity-seeking groups

- subject-matter experts

- bargaining agents

- departments and agencies

The report was written by an external panel of experts in collaboration with the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS).

Summary of key findings

Desired outcomes

Respondents hope the program will:

- Reduce the likelihood of future harms.

- Help participants heal.

- Resolve specific instances of harm.

Structure and design

Respondents said the program must be:

- safe

- empowering

- responsive

- effective

However, respondents had different ideas about what form the program should take:

- Some respondents prefer a distinct program.

- Some prefer a framework that would encompass all other conflict, harassment and discrimination programming.

- Others want a lens that would be applied across government.

Based on the responses, whatever form the program takes, it must be flexible enough to meet different community and contextual needs, but still have a centralized structure.

Respondents also highlighted the need to involve people from equity-seeking groups in all aspects of program design and delivery.

Governance

Most respondents believe that a single, centrally governed program would be the most effective. They cautioned, however, that the leading organization must be trustworthy and have sufficient authority to enforce systemic changes. Balancing trustworthiness and authority may require creating a new external or arms-length organization.

Barriers and mitigation strategies

Respondents identified three main barriers to program success and suggested strategies for addressing them.

| Barriers | Mitigation strategy |

|---|---|

| 1. People might decide not to participate because they don’t trust that the program will provide a safe space or that it will make a difference. |

|

| 2. Even if the program is perfectly designed, implementation may be inconsistent. |

|

| 3. Success hinges on adequate funding. |

|

Considerations for future consultation

TBS will use the information gathered from the written submissions and the panel’s recommendations to define the program structure and to plan broader consultation with public servants.

Future consultations will prioritize refining program design and will focus on components such as learning, well-being, trauma-informed practices, and cultural responsiveness.

Key considerations will include:

- preventing the re-traumatization of people affected by workplace harassment, discrimination and violence

- providing a safe space for open dialogue where there is no fear of reprisal

- incorporating best practices for cultural sensitivity and accessibility

- allowing sufficient time for feedback from the parties involved

- providing relevant materials in advance for transparency

- giving people opportunities to contribute ideas for systemic changes

- enabling senior leadership to identify challenges and support needs

- ensuring ongoing collaboration with the Interdepartmental Advisory Working Group and other key parties to meet the diverse needs across the federal public service

Acknowledgement

TBS would like to thank the panel of experts and everyone who participated in the consultation process. They provided valuable insights into and practical suggestions for designing a restorative engagement program for the federal public service. Their contributions were vital to the initial stage of this initiative. TBS looks forward to further collaboration on this important and necessary work.

Introduction

In September 2022, the government reconfirmed its commitment to creating a diverse and inclusive public service and issued a statement on action taken to further address harassment, discrimination, and other barriers in the federal workplace. In support of this commitment, the government also announced its plan to design a restorative engagement program to provide employees who have been affected by workplace harassment, discrimination and violence with an opportunity to share their lived experiences in a safe and confidential space and to contribute to organizational culture change in the federal public service.

To make sure the program meets the needs of all public servants, TBS and the panel of experts consulted with key parties to hear their perspectives on what an effective restorative engagement program for the federal public service could look like. This report summarizes their contributions.

What is restorative engagement?

Restorative engagement is a way to address harm and foster positive change in individuals, groups, institutions and systems. It places individuals at the centre of this process and focuses on understanding the connections, root causes, circumstances and impacts related to harm. The goal is to identify ways to address harm, promote healing and ensure a better future.

Restorative engagement aims for transformative change by:

- addressing the underlying factors that contribute to harm

- promoting deep healing and growth

- shifting cultural norms that perpetuate harm

It emphasizes proactive processes designed to nurture relationships, pre-empt conflicts, and prevent harmful behaviours.

Rationale for establishing a restorative engagement program

In the 2022 Public Service Employee Survey, 11% of respondents from equity-seeking groups said they had experienced harassment within the last 12 months and 8% said they had experienced discrimination. These figures were higher among employees from certain equity-seeking groups, highlighting the pressing need for systemic change, particularly in management culture and practices.

In this context, a restorative approach that is guided by the principle of “Do no more harm” can foster healing and growth in individuals, groups, institutions and systems.

Scope

The restorative engagement program currently being designed is intended for everyone in the core public administration and all separate agencies, including public servants employed in the Department of National Defence (DND) and in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). The program does not cover military members of the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF), officers of the RCMP or employees of Crown corporations.

The program is for individuals who have experienced harm, witnesses and those who may have been involved directly or indirectly. This inclusive approach ensures a comprehensive representation of perspectives and experiences in the program.

Consultation process

Insights from different parties were gathered through online written submissions. Submissions were accepted from October 30, 2023, to December 8, 2023. The information gathered will guide the design of the restorative engagement program and help define its structure.

Panel of experts

As part of the initial phase of the consultation process, the government convened a panel of experts to get input from key parties and propose recommendations for designing a restorative engagement program for the public service.

The panel was composed of four recognized experts in the following fields:

- facilitation and mediation

- workplace ethics

- restorative practices

- trauma-informed approaches

- mental health

The panellists were selected for their expertise and lived experiences with diverse equity-seeking groups including racialized people, Indigenous people, persons with disabilities, 2SLGBTQI+ individuals, and women.

The biographies provided by the panellists are in Appendix C.

The panel analyzed the written submissions and made recommendations on program design. The panel also validated consultation plans and reported on key findings from multiple information sources. Their expertise, both professional and gained through lived experiences, will ensure diversity, inclusivity and strategic insight-led approaches when building a restorative engagement program that is meaningful and relevant to the federal public service.

Interdepartmental Advisory Working Group

The Interdepartmental Advisory Working Group is made up of subject-matter experts from different federal departments and agencies who specialize in:

- diversity and inclusion

- prevention of harassment and discrimination

- conflict resolution

- labour relations

- legislation

- programs and policies

- disability management

- restorative practices

Members provided valuable insight into the vision, guiding principles, common priorities, and objectives for the development of the program. In addition, each member participated in one of six virtual discussions facilitated by the panel of experts, covering the same questions as those in the written submission questionnaire. Their contributions helped identify key considerations for the panel throughout the initial consultation and design phase.

Respondents

Representatives from the following four groups were invited to complete a written submission using an online questionnaire.

| Respondent groups | Number invited | Number of respondents | Response rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Networks and organizations representing federal public servants from equity-seeking groups | 51 | 25 | 49% |

| Bargaining agents | 18 | 4 | 22% |

| Networks and organizations with subject-matter experts | 14 | 9 | 64% |

| Federal public service departments and agencies | 92 | 38 | 41% |

| Total | 175 | 76 | 43% |

The online questionnaire asked primarily open-ended questions about priorities for the program’s desired outcomes, structure and design, governance, and potential barriers to success. Seventy-six forms were submitted, representing 43% of the organizations invited to participate.

The online questionnaire was available for six weeks, and accommodations were provided on request.

Written submissions were analyzed in parallel by the panel of experts, by an external research and analysis firm (One World Inc.) and by TBS.

Limitations

The following limitations should be kept in mind when reading this report:

- Scope: Written submission questions were limited to what the restorative engagement program will need to look like. More consultations will be needed to further develop the program and its components.

- Generalizability: This report summarizes the perspectives of those who provided written submissions or participated in virtual discussions with the Interdepartmental Advisory Working Group. Networks and organizations that did not respond may have different opinions.

- Representation: Each participating network or organization was asked to consult with their membership about their submission. However, the method and depth of these consultations varied. This report assumes that each written submission is representative of the group that submitted it.

Key findings

The following sections summarize the insights of a wide spectrum of parties and shed light on the workplace challenges encountered by individuals outside the dominant culture. These challenges, which stem from harassment, discrimination, and violence at both the interpersonal and the group level, create barriers, including barriers to career advancement. Microaggressions, exclusion and systemic biases compound these barriers, illustrating the multifaceted nature of the issues at hand.

Consultations from roundtable discussions with subject-matter experts, coupled with the written submissions from numerous other parties, have provided invaluable perspectives on these issues and how to tackle them. Despite existing initiatives in equity, diversity, and inclusion, respondents mentioned the urgent need to:

- acknowledge the seriousness of the harmful effects of systemic discrimination

- accept appropriate responsibility

- address the contributing factors of harm

The resounding call for transformative cultural change amplifies the importance of the restorative engagement program in addressing the challenges in existing systems.

Desired outcomes

We asked:

- If the program was effective, what would change for participants?

- How important is it for the program to include the following objectives for participants?

- Reduce the risk of someone else having the same experience

- Share ideas about what needs to change in the institution

- Help those who have been harmed to heal and get closure

- Acknowledge how the department or agency contributed to harm

- Resolve the specific instance of harm

- Share how participants were affected by the harm

- Share how the department or agency should have responded

- Issue official apologies to those who have been harmed

- Report harm to authorities

- Lead to consequences for those who have done harm

- If the program was effective, how would federal departments and agencies be different?

- How can the program meaningfully contribute to culture change in the federal public service?

We heard:

- Reduce the likelihood of future harm

- Change organizational culture and enforce systemic change

- Help participants heal by acknowledging their experiences

- Resolve specific incidents (with caveats)

Reduce future harms

The most common objective respondents said they would like the program to achieve is to reduce future harms for others. By providing a forum to hear from those who have experienced harm, the government as an employer can learn what changes are needed.

99% of respondents want the restorative engagement program to reduce the risk of others having a similar experience.

Written submissions revealed that reducing future harms was often linked to the following:

- changing organizational culture

- implementing systemic changes to government policy or processes

a) Culture change

The idea that a restorative engagement program could initiate organizational culture change was threaded through responses in different ways. Some respondents see culture change as an objective on its own. Others see it as a way to reduce future harm and help participants heal. Some respondents believe that the process of creating and implementing such program would change the work culture. Others see culture change as a deliberate response to lessons learned from the program once it is implemented.

In general, people want a restorative engagement program to help create to a safer, more equitable workplace where employees from equity-seeking groups can bring their authentic selves and achieve their full potential at work. This organizational culture was also described as an environment where individuals would feel:

- included and welcomed, free from microaggressions

- valued, supported and respected

- assessed based on their skills, knowledge and performance

- supported to resolve conflicts through healthy interactions and conversations, without fear of reprisal

Some respondents commented that an improved culture will include managers who have both the training and the influence to lead in a way that is fair and empathetic.

b) Systemic change

Like culture change, the idea of a restorative engagement program influencing systemic change was articulated in multiple ways. Some see it as an objective on its own, while others see it as one tool to reduce future incidents of harm.

Respondents commented that, through lessons learned during the restorative process, the government as an employer could:

- develop and implement preventive measures

- apply existing rules and policies more equitably or consistently

- streamline existing conflict resolution services (make them more consistent and coherent).

- remove bureaucracy or break down silos that can cause harm

Help participants heal

Most respondents also want the program to help participants heal from or gain closure on their negative experiences. Many respondents commented that, by validating participants’ feelings and acknowledging their experiences, the program could facilitate healing. Many respondents shared that having senior leadership acknowledge the harm is critical to this healing process. The program could also reduce the stigma and shame associated with having experienced workplace harm (for example, by helping participants process that the experience was not their fault). Many respondents commented that the program should empower participants and reduce revictimization.

Some respondents pointed out that healing is not only important for participants, but that it is also beneficial for the government as an employer. An employee who has been supported to heal is likely to be more engaged, motivated and productive overall.

Resolve specific instances of harm

Most respondents want a restorative engagement program that helps resolve specific instances of harm, but punishment as resolution does not align with the traditional restorative approach. Restorative programs focus on promoting understanding and healing, and on transforming the environment, rather than on imposing punishment or personal remedies.

Many respondents also spoke of the program as an opportunity to resolve specific issues or incidents of harm. They mentioned that the program will need to provide timely, user-friendly, confidential and trauma-informed service. Some noted that a restorative engagement program would be preferable to a formal complaint process and to existing informal conflict management systems. Others see the program as being complementary to existing systems. A few respondents also believe that the program should be distinct from existing programs and support services in a way that creates a safe environment for employees to come forward with a complaint and that has concrete and transparent disciplinary measures for those who have perpetrated the harm.

Monitoring and reporting

In addition to identifying desired program outcomes, some respondents also pointed out the need for proper oversight. Some respondents shared potential indicators that outcomes are being achieved, including higher rates of employee well-being and higher rates of recruitment and retention of employees from equity-seeking groups, specifically in executive and other positions of high pay and high responsibility.

Structure and design

We asked:

- What would an ideal restorative engagement program look like in the federal public service?

- How important is it for this program to include the following program elements?

- Reporting on systemic issues identified

- Reporting on lessons learned

- Educational component

- Restorative circles and dialogue

- Mental health services

- Connecting participants to other services

- Discussion between participants and employer

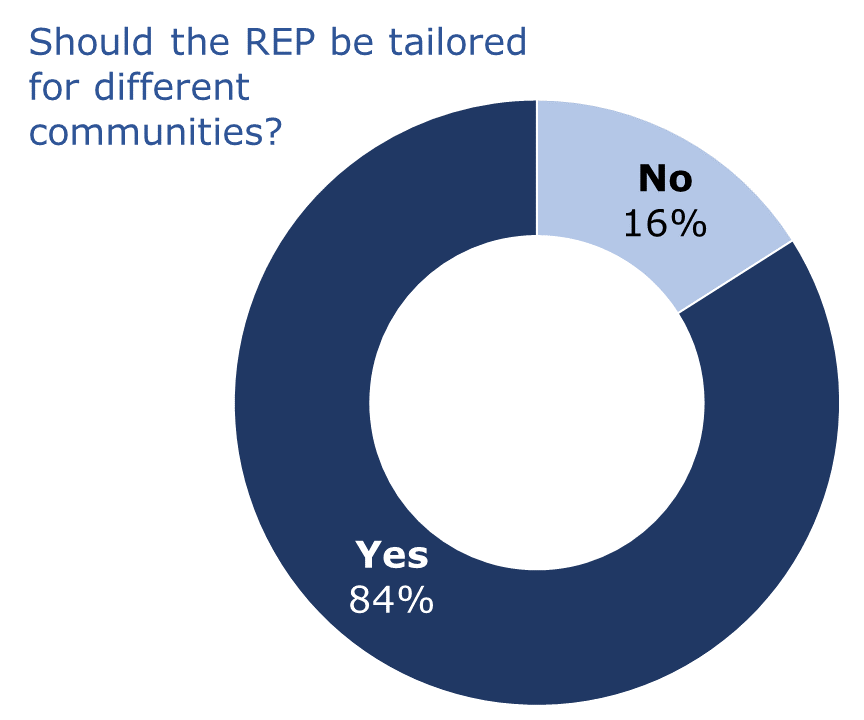

- Should the program be tailored for different communities?

- How should the program coexist with the current services and resolution mechanisms?

- What other roles would you include in the program process?

We heard:

- Establish a restorative engagement program that is safe, empowering, responsive and effective

- Possible models include a restorative engagement program, a restorative engagement framework or a restorative engagement lens

- Allow enough flexibility to meet varying community and contextual needs, while still maintaining a single initiative

- Include a wide range of program activities and elements

- Involve affected employees, decision-makers, practitioners and partners.

- Involve individuals from equity-seeking groups in all aspects of program design and implementation.

Foundational guidelines

The written submissions indicated that the program must adhere to four guidelines. The program must be:

- safe

- empowering

- responsive

- effective

The list below provides more detail on each guideline.

1. Safe

- Do no more harm

- Provide supports for physical and emotional safety

- Use trauma-informed practices

- Cultivate trust through clarity, consistency, and defined boundaries.

- Prioritize collective well-being

- Uphold confidentiality and fairness

2. Empowering

- “Nothing about us without us”

- Incorporate anti-racism principles

- Build in shared responsibility with employees from all equity-seeking groups

- Explicitly acknowledge harm and recognize its impact

- Make it easy for employees to access services and to choose which services are right for them

3. Responsive

- Be flexible and adapt to participants’ evolving needs

- Consider the lived experience of all equity-seeking groups

- Integrate best practices from other initiatives

4. Effective

- Aim for systemic impact by addressing underlying issues

- Offer immediate, concrete solutions

- Strive for realistic outcomes and manage participant expectations

- Act in a timely manner

- Build in accountability for change through monitoring and reporting

Restorative engagement models

Respondents suggested different models to incorporate restorative engagement into existing programs.

Because no direct questions were asked about these models and because respondents often spoke about aspects of more than one model without providing details, it is not possible to comment on which model most respondents prefer.

The three models are as follows.

1. Restorative engagement program

Restorative engagement as a program could function in a similar way to the restorative engagement program that the CAF and DND are running as part of the settlement in the sexual misconduct class action suit. Participants who have been affected would share their personal experiences. Employer representatives would learn from these experiences and act on the lessons learned.

In this model, the restorative engagement is independent from other programming and initiatives. Participants could access this program instead of or in addition to other resolution mechanisms or support services.Footnote 1 The program would be unique in that it focuses on restoring the workplace itself. Respondents also pointed out the importance of clearly explaining how a restorative engagement program differ from other services.

2. Restorative engagement framework

Restorative engagement as a framework would function as a coordinating process. Employees who have experienced harm would start with the restorative engagement program, then be directed to other programs or services appropriate for their needs. Respondents who suggested this model used terminology such as “one-stop shop,” “centre of excellence or expertise,” and “breaking down siloes.”

Under a restorative engagement framework, existing services could be streamlined for a better employee experience. An organization that has oversight over a wide range of related services would be set up and would make sure they are integrated and that they have appropriate scopes.

3. Restorative engagement lens

In this model, restorative engagement would be a lens that would be applied to all government initiatives that address related issues (for example, initiatives related to conflict management, harassment and violence resolution, discrimination, and equity and diversity) and to processes such as performance management, staffing and talent management. Respondents who advocate taking this approach spoke about integrating restorative practices into existing mechanisms, rather than creating something new.

This model would involve creating guidelines and tools that could be used in multiple contexts, much like the gender-based analysis plus (GBA plus) lens the government currently uses horizontally to reduce barriers to participation and to mitigate potential negative impacts of programs.

Regardless of which model they preferred, most respondents said that restorative engagement should:

- allow cohesion with complementary programs and initiatives and break down siloes (while respecting the individuals’ privacy)

- avoid duplicating existing programs and initiatives (which will require clearly defining the restorative engagement program and its scope)

- be integrated into departmental and agency culture and into existing programs, services and initiatives

Tailoring

Most respondents want some sort of tailoring and flexibility, so that the program can meet the needs of different participants, groups or communities. Usually, this meant respondents called for variations for different equity-seeking groups, for different organizational contexts, or for both.

At the same time, respondents cautioned that creating multiple, separate programs could introduce the risk of inconsistent quality. To balance these concerns, some called for a single program that is flexible enough to adapt to different needs and contexts.

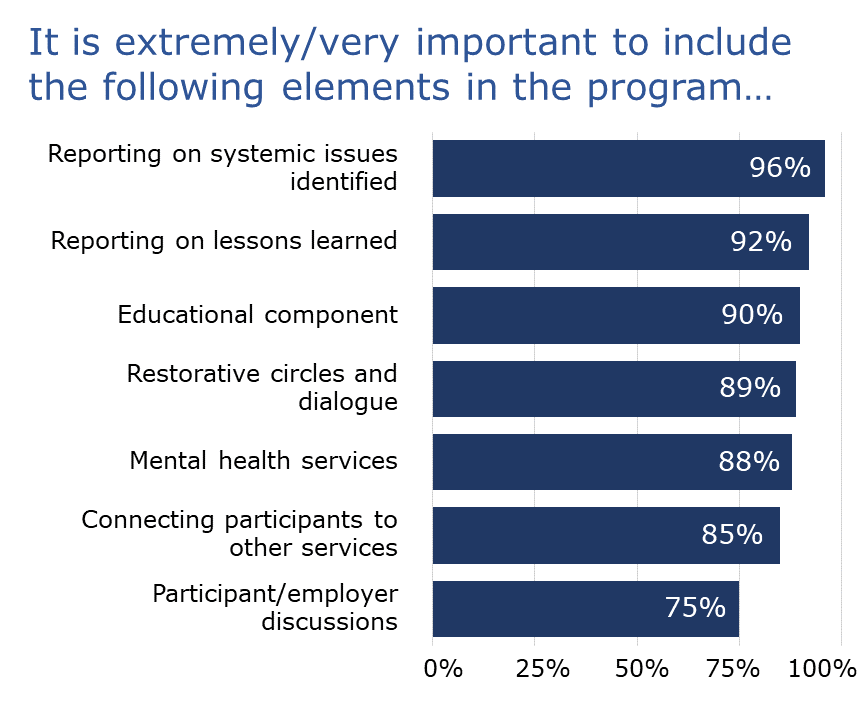

Program elements

Respondents also identified key functions or activities to include in a restorative engagement program. They include the following:

- Engaging with and listening to participants: the program should provide a safe and confidential forum where employees can share their lived experiences and where senior leadership can learn from them.

- Raising awareness of:

- 1) the successes and impact of the program

- 2) other anti-racism, diversity and equity initiatives

- 3) the lived experiences of people in equity-seeking groups.

- Building capacity and fostering a learning culture: the program should include education and training in restorative approaches, accompanied by guidelines and tools.

- Ensuring continuous knowledge transfer by identifying and sharing best practices and lessons learned about how to minimize harassment, discrimination, and violence in the workplace.

- Adopting best change management practices so that the program is well understood, supported, used appropriately and evolving.

Most respondents rated the above key functions or activities to be extremely or very important for a restorative engagement program.

Figure 2 - Text version

It is extremely/very important to include the following elements in the program…

Reporting on systemic issues identified 96%

Reporting on lessons learned 92%

Educational component 90%

Restorative circles and dialogue 89%

Mental health services 88%

Connecting participants to other services 85%

Participant/employer discussions 75%

Roles

Respondents suggested five main roles in the restorative engagement program:

1. Affected people: These are people who have experienced, witnessed harm or perpetrated harm. Their responsibilities would include coming forward with their experiences and sharing the facts of the harm.

2. Decision-makers: Ideally at the deputy head or assistant deputy minister level, decision-makers, would be present at restorative sessions to listen, understand the harm experienced and recognize the relationship between the specific instance of harm and systemic biases and discrimination. Decision-makers would be responsible for acting on what they have learned to foster workplace restoration.

3. Practitioners: These are professionals who can facilitate the process, create a safe space for affected people and support them on their healing journey. Practitioners could include:

- facilitators and mediators

- mental health professionals and psychosocial supports

- coaches, mentors, career counsellors

- subject-matter experts or advisors

- trainers and educators

- cultural advisors

Practitioners should have expertise in restorative approaches, conflict resolution or trauma informed practices, as well as experience with the issues relating to different equity-seeking groups (for example, anti-Black racism, Indigenous reconciliation, accessibility standards). Some respondents suggested using external consultants to fulfill these roles.

4. Mobilizers: Policy and data analysts responsible for gathering lessons learned from the restorative engagement program and putting it to use across government.

5. Evaluators: Analysts responsible for gathering feedback on the program, assessing its effectiveness and contributing to its continuous improvement.

Respondents often noted the importance of involving bargaining agents and Indigenous Elders early in the process when necessary.

Respondents also stressed the need to include equity-seeking groups in both the development and delivery of the program, honouring the “Nothing about us without us” principle. Benefits of doing so include:

- better understanding of the needs and contexts of the people the program is intended to help

- increasing trust in the program and the likelihood that potential participants will feel safe

- showing the value of a diversity and inclusion model and about the government’s commitment to this model.

Governance

We asked:

- Who should be responsible for the restorative engagement program?

- What type of authority, if any, should the program have to recommend changes to departments and agencies?

We heard:

- Centralize the program under one governing organization.

- Base the program in an organization that can be trusted.

- Give the governing body authority to enforce changes.

Centralized governance

Most of the networks and organizations consulted believe a single, centrally governed, independent restorative engagement program would be the most effective. They want the program to have binding authority and to be able to hold to account people who harm others, and leaders of departments and agencies.

Benefits of a central program and authority include the following:

- Standardization and uniformity: Program standards, guidelines, principles and procedures will be consistent across all agencies and departments. Some respondents expressed concern that, if each department or agency governs its own program, the quality will vary.

- Sharing of expertise and resources will align resources to participants’ needs and cultural context.

- Resources will be more accessible because they won’t depend on the goodwill of managers and upper management and because information will be standardized.

- Evidence-based management: Centralized governance will make it easier to collect, analyze and use data to understand and address systemic issues and to continually improve the program itself.

- Cost-efficiency from reducing duplication and streamlining processes.

Based in an independent organization

Most respondents pointed out the need for the restorative engagement program to be governed or managed by an organization that can be trusted to act independently and impartially. Most said that equity-seeking groups have lost trust in existing government organizations and that a new, external or arms-length organization must be created.

Potential benefits of a new, external or arms-length organization include the following:

- having only one organization with dedicated resources and specialized expertise

- avoiding real and perceived conflict of interest by being an independent organization

- enabling trust, transparency and accountability

- increasing flexibility to innovate and adapting more quickly to emergent needs

- reducing fear of retaliation (in other words, confidence that participation will not negatively impact the careers or work lives of participants)

If day-to-day program management and delivery is decentralized, some respondents called for it to be made part of existing human resources functions (for example, informal conflict management systems or ombud offices). However, most said these existing structures could not be trusted and that the restorative engagement program must exist outside of them to be effective.

Give the governing body authority

Almost all respondents feel that the restorative engagement program should have the authority to recommend systemic changes, including improvements to human resources policy and practice.

Opinions differed among respondent groups about whether the program should have binding authority to enforce these recommendations:

- Equity-seeking groups suggest binding authority

- Bargaining agents suggest binding authority

- Subject-matter experts have differing opinions

- Departments and agencies suggest authority to recommend

Respondents who want the program to have authority to enforce recommendations believe this is necessary to make sure that there is concrete action. They commented that without enforcement capabilities, the impact of the program could be diluted because it would be subject to bureaucratic blockages, systemic barriers or lack of accountability. Some also believe that legislative changes may be necessary to provide the program with sufficient authority.

Department and agency representatives are primarily concerned about ensuring that the program authority appropriately balances leveraging the expertise and respecting the autonomy of deputy heads. They believe non-binding recommendations would support implementing any lessons learned from the restorative engagement program in a manner that considers the unique context of each department or agency.

In conclusion, there is a clear consensus that the restorative engagement program should be centralized, independent and have binding authority.

Barriers and mitigation strategies

We asked:

- What barriers might prevent a restorative engagement program from being effective for the members of your organization or network?

- What are your recommendations to overcome these barriers?

We heard:

- To address the ongoing lack of trust:

- 1) design the program slowly

- 2) commit to tangible impact

- 3) house the program in a trustworthy organization

- To avoid poor or inconsistent implementation:

- 1) establish central guidelines and standards

- 2) clearly communicate objectives and processes

- 3) educate senior leaders

- 4) foster communication

- 5) engage equity-seeking groups and affected parties

- Invest sufficient, dedicated resources.

Build trust

Some respondents are concerned that a restorative engagement program might not be effective in the current environment, in which many people who have experienced workplace harassment or discrimination do not trust the organization (specifically, leaders and people working in human resources). They expressed concern that individuals would decline to participate because:

- they don’t believe the program is a safe space to be vulnerable

- they don’t believe the program will make a difference

Suggested strategies to mitigate these concerns often mirrored findings in other sections of this report. They include the following:

- Design the program slowly, co-developing it with those who have experienced workplace harassment, discrimination or violence. A few suggested pilot programs with continuous improvement before broader implementation, so that changes could be made rapidly as organizations learn what works and what doesn’t.

- Commit to making tangible impact, demonstrating a high-level commitment to remedial action and implementing the cultural and systemic changes recommended by the restorative engagement program. Many respondents believe this requires granting the program sufficient authority to compel action and to hold departments accountable for follow-through on recommendations.

- House the program in a trustworthy organization, which may require creating a new arms-length organization or governing body that is perceived to be neutral and transparent.

Implement faithfully

Respondents commented that integrating restorative practices in the government context is complex. Even with the best structure and design, a program is only as good as its implementation. Some respondents also commented that the program landscape is already complex and that people who have experienced harm often don’t know where to go or what to do. They also expressed frustration that existing programming (for example, informal conflict management systems, ombud services, mental health services) may not be delivered as promised and may be ineffective. Respondents cautioned that an effective restorative engagement program must have integrity to avoid being similarly ineffective.

To support effective program implementation, respondents suggested the following:

- Establishing, at a minimum, centralized guidelines and standard processes so that the REP is consistent, at the same time, allowing sufficient flexibility to adapt the process to different organizational structures.

- Clearly communicating the program’s objectives and process and investing in change management so that all employees understand how and when they should access the program.

- Educating senior leaders about restorative practices.

- Fostering communication and collaboration between the restorative engagement program and other mechanisms that may have areas of overlap (for example, informal conflict management systems, equity, diversity and inclusion initiatives).

Few respondents suggested mitigation strategies that specifically targeted the barriers posed by insufficient resources, likely because they seemed too obvious. Interdepartmental Advisory Working Group members suggested that the challenges posed by insufficient resources may be resolved through a dedicated and protected, long-term funding stream.

Resource appropriately

Respondents cautioned that successful operation of the program hinges on adequate funding to:

- hire appropriate staff and train them on issues such as racial discrimination and harassment, and on how to foster a safe work environment, on trauma-informed care, and on restorative practices.

- provide participants with essential resources, such as mental health support, restorative approaches and accommodations

- provide participants with supports to compensate for career development missed due to discrimination (for example, coaching, mentoring, leadership programs, and so on).

A few expressed concern that programming related to reducing harassment, discrimination and violence is routinely under-resourced.

Lived experiences

We asked:

- What aspects of your members’ diverse experiences should we consider when developing an REP for the federal public service?

We heard:

- Engage persons with lived experience in all phases of the program development.

- Be aware of power dynamics, recognize that skepticism might affect whether a restorative engagement program will have an impact and understand the intersections between harm and identities.

Respondents proposed different considerations for all aspects of the program design. They also consistently stressed that people with lived experience from equity-seeking groups must be involved in all phases of program development and implementation.

Power dynamics

Harmful behaviours are rooted in culture and originate primarily from upper management. These harms are often amplified by the administrative procedures in programs and processes that are intended to address them. For example, a conflict resolution mechanism that doesn’t disclose outcomes (to protect confidentiality), might inhibit healing. Employees might also be afraid to share their experiences because they expect reprisal. Determinate employees (employees hired for a fixed period) are particularly vulnerable because they lack job security.

Skepticism

Individuals who have experienced systemic barriers and harms in the workplace may be skeptical that the environment will ever change. Some believe there is a genuine lack of commitment to addressing systemic issues. Others see the government as an unwieldly organization that changes too slowly. Regardless, respondents fear the program will become “just another paper exercise”.

Intersection between harm and identity

Harassment and violence are often tied to discrimination and bias; they cannot be addressed in isolation. Respondents believe that the restorative engagement program should respond to discrimination and harassment experienced by 2SLGBTQI+ individuals and by religious minorities, in addition to that experienced by the four employment equity groups. They also highlighted that equity-seeing groups are not homogenous and that intersectionality need to be considered when developing this program. A few respondents also stressed that Black employees have a distinct experience from other racialized people.

Conclusion

-

In this section

Developing and implementing a restorative engagement program is an opportunity for transformative change in the federal public service. The program is not just about policies or another set of initiatives; it is a commitment to a cultural shift by modelling diversity, inclusion and accessibility in our work environment.

The first consultation round with federal networks and organizations representing employees from diverse equity-seeking groups, subject-matter experts, bargaining agents, as well as departments and separate agencies, was meaningful and informative.

Based on what was heard, the following key themes are evident:

- The federal public service needs a restorative engagement program to reduce incidents of workplace harassment, discrimination and violence and to help those who have experienced harm to heal.

- A restorative engagement program should have a clear mandate and principles. Decisions will need to be made about the overarching restorative engagement model and how it works with programs that are already in place.

- A restorative engagement program should be centralized and trustworthy, and the organization that is responsible for it should have the authority to make binding recommendations. This may require the creation of a new external or arms-length organization.

- A restorative engagement program should be flexible enough to accommodate different needs, lived experiences and environments. It should also evolve as organizations learn what works and what doesn’t.

- All equity-seeking groups must be consulted, included and integrated at each level of the development and delivery of the program.

- The program should not be just another option; it should drive a cultural shift in how individuals relate to one another in the workplace.

The information collected during this consultation will guide the development and design of a restorative engagement program for the public service.

Considerations for future consultation

As we build on findings and lessons learned from this initial consultation phase, any future consultation will focus on refining program design elements and making sure they align with principles of learning, well-being, trauma-informed practices and cultural responsiveness. It will also be centred on individuals and will make sure:

- those affected by workplace harassment and discrimination in the federal public service are not re-traumatized during the engagement process

- employees and leadership at all levels have a safe space to share insights, lived experiences and suggestions on the program elements without fear of reprisal

- cultural sensitivity, trauma-informed practices and accessibility best practices are considered

- interested parties have sufficient time to provide meaningful feedback

- relevant materials are provided in advance to facilitate informed engagement and to encourage transparency during the engagement process

- people can share knowledge and contribute ideas and insights for tangible systemic changes in the federal public service

- senior leaders can identify challenges they are facing and how a restorative engagement program can support them and their organizations

- the Interdepartmental Advisory Working Group and key partners continue to collaborate to meet the needs of the diverse communities and realities across the federal public service

Appendix A: Invited parties

This list includes all parties invited to participate in the consultation process. Not all organizations or networks listed provided written submissions.

Departments and agencies

- Administrative Tribunals Support Services Canada

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

- Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency

- Canada Border Services Agency

- Canada Revenue Agency

- Canada School of Public Service

- Canadian Accessibility Standards Development Organization

- Canadian Dairy Commission

- Canadian Energy Regulator

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency

- Canadian Grain Commission

- Canadian Heritage

- Canadian Human Rights Commission

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat

- Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency

- Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission

- Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission

- Canadian Security Intelligence Service

- Canadian Space Agency

- Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board

- Canadian Transportation Agency

- Citizenship and Immigration Canada

- Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the RCMP

- Communications Security Establishment

- Copyright Board

- Correctional Service of Canada

- Courts Administration Service

- Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

- Department of National Defence

- Department of Public Works and Government Services

- Department of Western Economic Diversification

- Economic Development Agency of Canada for the Regions of Quebec

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- Environment Canada

- Federal Economic Development Agency for Northern Ontario

- Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario

- Finance Canada

- Financial Consumer Agency of Canada

- Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development

- Health Canada

- Immigration and Refugee Board

- Impact Assessment Agency of Canada

- Indigenous Services Canada

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada

- International Joint Commission (Canadian Section)

- Invest in Canada Hub

- Justice Canada

- Law Commission of Canada

- Library and Archives of Canada

- Military Grievances External Review Committee

- Military Police Complaints Commission

- National Capital Commission

- National Farm Products Council

- National Film Board of Canada

- National Research Council of Canada

- National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Secretariat

- Natural Resources Canada

- Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council

- Office of Infrastructure of Canada

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada

- Office of the Chief Electoral Officer

- Office of the Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs

- Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying

- Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages

- Office of the Correctional Investigator of Canada

- Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions

- Office of the Governor General’s Secretary

- Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner

- Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions

- Offices of the Information and Privacy Commissioners of Canada

- Pacific Economic Development Agency of Canada

- Parks Canada Agency

- Parole Board of Canada

- Patented Medicine Prices Review Board

- Polar Knowledge Canada

- Privy Council Office

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness

- Public Service Commission

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police External Review Committee

- Shared Services Canada

- Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council

- Staff of the Supreme Court

- Statistics Canada

- Transport Canada

- Treasury Board

- Veterans Affairs Canada

- Women and Gender Equality Canada

Employee networks and organizations

- 2SLGBTQI+ Secretariat

- Anti-Racism Ambassadors Network (ARAN)

- Anti-Racism Networking Hub (ARNH)

- Anti-Racism Secretariat

- Association of Professional Executives of the Public Service of Canada (APEX)

- Black Class Action Secretariat

- Black Executives Network (BEN)

- Canada Centre for Occupational Health and Safety (CCOHS)

- Champions and Chairs Circle for Indigenous Peoples (CCCIP)

- Committee for Advancement of Native Employment (CANE)

- Community of Federal Visible Minorities (CFVM)

- Correctional Service Canada Office of the Ombuds for Workplace Well-being

- DND Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM)

- Employment Equity Champions and Chairs Committees (EECCC)

- ESDC Black Employee Network (BEN)

- ESDC Black Engagement and Advancement Team (BEAT)

- ESDC Employee Pride Network (EPN)

- ESDC Employees with Disabilities Network (EwDN)

- ESDC Indigenous Coordination and Engagement Division (ICE)

- ESDC Indigenous Employees’ Circle (IEC)

- ESDC Visible Minorities Network (VMN)

- FBEC Women’s Caucus

- Federal Black Employee Caucus (FBEC)

- Federal Informal Conflict Management System Network

- Federal Public Service Indigenous Training and Development Community of Practice (ITDCOP)

- Federal Youth Network (FYN)

- Filipino Public Servants Network (FPSN)

- Global Affairs Canada Inclusion Diversity Equity Accessibility and Anti-Racism

- Government of Canada Women in Non-Traditional Sectors

- Human Resources Council (HRC)

- Indigenous Centre of Expertise

- Indigenous Federal Employees Network (IFEN)

- Interdepartmental Black Employees Network (I-BEN)

- Interdepartmental Network of Accessibility and Disability Chairs (INADC)

- Interdepartmental Network on Diversity and Employment Equity (IDNDEE)

- Jewish Public Servants Network (JPSN)

- Joint Employment Equity Committee (JEEC)

- Knowledge Circle for Indigenous Inclusion (KCII)

- Latin American Heritage Group

- Muslim Federal Employees Network (MFEN)

- National Association of Federal Retirees (NAFR)

- National Managers’ Community (NMC) Secretariat

- Natural Resources Canada Visible Minority Advisory Council

- Network for Neurodivergent Public Servants (Infinity)

- Network of Asian Federal Employees (NAFE)

- Office of Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner

- Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer

- Persons with Disabilities Champions and Chairs Committee (PwDCCC)

- Positive Space Initiative (PSI)

- Public Service Pride Network (PSPN)

- Racialized Women Belonging (RWB) Group

- Sikh Public Servants’ Network

- TBS Departmental 2SLGBTQI+ Network

- TBS Departmental Accessibility Network

- TBS Departmental Black Employees Network

- TBS Departmental Employee Network on Inclusion

- TBS Departmental Indigenous Employee Network

- TBS Departmental Women's Network

- TBS Inclusion, Diversity, Equity and Accessibility (IDEA) Secretariat

- TBS Renaissance Network

- Veterans Affairs Canada Accessibility Network

- Veterans Affairs Canada National Diversity and Inclusion Advisory Committee

- Veterans Affairs Canada Positive Space 2SLGBTQI+ Network

- Visible Minorities Champions and Chairs Committee (VMCCC)

- Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM)

Bargaining agents

- Association of Canadian Financial Officers (ACFO)

- Association of Justice Council (AJC)

- Canadian Association of Professional Employees (CAPE)

- Canadian Federal Pilots Association (CFPA)

- Canadian Merchant Canadian Military Colleges Faculty Association (CMCFA)

- Canadian Merchant Service Guild (CMSG)

- Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE)

- Federal Government Dockyard Chargehands Association (FGDCA)

- Federal Government Dockyard Trades and Labour Council-East (FGDCATLC-E)

- Federal Government Dockyard Trades and Labour Council-West (FGDTLC-W)

- International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW)

- National Police Federation (NPF)

- Professional Association of Foreign Serve Officers (PAFSO)

- Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada (PIPSC)

- Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC)

- Research Council Employees Association (RCEA)

- UNIFOR: Local 2182 and Canadian Air Traffic Control Association (CATCA)

- Union of Canada Correctional officers (UCCO)

Appendix B: Acronyms, abbreviations and glossary

-

In this section

Acronyms and abbreviations

- 2SLGBTQI+:

- two-spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex (which considers sex characteristics beyond sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression), plus (which is inclusive of people who identify as part of sexual and gender diverse communities, who use additional terminologies)

- CAF:

- Canadian Armed Forces

- DND:

- Department of National Defence

- GBA+:

- gender-based analysis plus

- RCMP:

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- TBS:

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

Glossary

- Discrimination

- The unjust or prejudicial treatment of a person or group of people based on a prohibited ground under the Canadian Human Rights Act that deprives them of or limits their access to opportunities and advantages that are available to other members of society.

- Employment equity

-

Employment equity is to achieve the establishment of working conditions that are free from barriers, so that no person shall be denied employment opportunities or benefits for reasons unrelated to ability. It requires special measures to accommodate differences for the four designated groups in Canada where there is evidence of underrepresentation. The Employment Equity Act identifies the designated groups as:

- women

- Indigenous peoples

- persons with disabilities

- members of visible minorities

- Equity-seeking group

- A group of persons who are disadvantaged on the basis of one or more prohibited grounds of discrimination within the meaning of the Canadian Human Rights Act.

- Harassment and violence

- Harassment and violence are defined in the Canada Labour Code as any action, conduct, or comment, including of a sexual nature, that can reasonably be expected to cause offence, humiliation or other physical or psychological injury or illness to an employee, including a prescribed action, conduct or comment.

- Participant

- Individual who has been affected by workplace harm and chooses to participate in the restorative engagement program once it is established.

- Respondents

- Contributing parties who provided a written submission using an online questionnaire during the consultation process.

- Systemic discrimination

- Patterns of behaviour, policies or practices that are part of the structure of an organization and that create or perpetuate disadvantage for persons on a prohibited ground of discrimination in the Canadian Human Rights Act.

Appendix C: Panellists’ biographies

The following biographies were provided by the panellists.

Dr. Jude Mary Cénat is an associate professor at the University of Ottawa, where he holds the position of Director of the Interdisciplinary Centre for Black Health and of the Vulnerability, Trauma, Resilience and Culture Research Laboratory (V-TRaC Lab). He also holds the University Research Chair on Black Health. Additionally, Dr. Cénat leads major projects focusing on the mental health of Black communities in Canada, with a focus on reducing racial disparities in health and social services and build collective resilience.

Linda Crockett is an expert and advocate on workplace psychological harassment in Canada. She graduated with an advanced clinical master’s degree in social work with a specialization in addressing the psychological, physical, and emotional effects of workplace bullying. She founded the Canadian Institute of Workplace Bullying Resources, which offers trauma-informed services to all professions, industries and communities focusing on prevention, intervention, and recovery. Linda also recently founded a not-for-profit resource, the Canadian Institute of Workplace Harassment and Violence to assist injured workers seeking financial support and legal information.

Gayle Desmeules is an experienced Indigenous mediator, facilitator, and trainer with 30 years of experience in dispute resolution and engagement processes that prioritize respect, safety and real conversations. She graduated with a Master of Arts in Leadership and Training from Royal Roads University and is a Q. Med (Qualified Mediator) and affiliated with the alternative dispute resolution institute of Alberta and of Canada. Gayle is also the founder and chief executive officer of True Dialogue Inc., which offers customized training, mediation and consulting services in restorative resolutions. As a Métis person and a child of a residential school survivor, Gayle has a deep understanding of the impact of colonization and actively advances the process of reconciliation to promote community wellness.

Robert Neron is bilingual and of Aboriginal (Métis) descent. He is a senior arbitrator and a workplace investigator with over 26 years of legal expertise. He specializes in employment law, human rights law, Aboriginal law and administrative law. He is a member of the Law Society of Ontario and has a track record of arbitrating workplace grievances and complaints in various sectors, as well as conducting workplace investigations. Robert was also an adjudicator for the independent assessment process of the Indian Residential Schools Adjudication Secretariat.

© His Majesty the King in Right of Canada, represented by the President of the Treasury Board, 2024,

ISBN: 978-0-660-71383-0