Report 2: Recommendations on the federal government's drug policy as articulated in a draft Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy (CDSS)

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 1.5 MB, 41 pages)

Organization: Health Canada

Published: 2021-06-06

Table of contents

- Message from the Co-Chairs

- Truth and Reconciliation in Canada's Drugs and Substances Strategy

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Task Force members

- Approach and methodology

- Key messages

- Articulation of the problem

- The way forward

- Appendix A - Task Force member bios

- Appendix B - Recommendations from the first report

- Appendix C - Glossary of terms

Message from the Co-Chairs

We are pleased to submit this second report from the Health Canada Expert Task Force on Substance Use which gives recommendations on the Federal Government's substance use policy as articulated in the draft Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy.

We are honoured to have been given the responsibility of Co-Chairing this Task Force and we are conscious of the historical opportunity this represents to contribute to the discussion on how to improve the way controlled substances are managed and regulated in Canada.

We see this as a pivotal time for policies that aim to decrease harms from substance use. Our Expert Task Force met virtually during COVID-19 and with seemingly weekly reminders of how historical and current systemic racism, social inequalities, and policy decisions are fuelling substance use harms.

The Expert Task Force was given specific questions to answer about the CDSS and has answered them in the report but felt a need to go further and signal clearly that bold action is needed to address the urgent problem of rising overdoses and other harms from substances in Canada.

It is time for a paradigm shift in policy. The reception of the cannabis legalization and more recent public opinion surveys suggest that there is an appetite for Canada to move to twin increased investment in a comprehensive network of services and supports for those who use substances with newer strategies such as regulation of controlled substances, the decriminalization of simple possession and drug use, and the expansion of safer supply. The evidence supports these policy alternatives as ways to decrease substance use harms according to groups such as the Global Commission on Drug Policy as well as the presentations and written submissions the Expert Task Force received from Canadian community groups, organizations representing people with lived and living experience, clinicians, and academics.

We are thankful to all those who shared their knowledge and wisdom. They have helped the Expert Task Force develop its thinking and build recommendations based on the best evidence.

It has been a privilege to work with the diverse group of experts who made up the Task Force. Each member brought a unique perspective to our collective effort, and all have contributed to a rich dialogue that has resulted in the recommendations we present to you today.

Finally, our thanks go to the Secretariat and to the report-writer who have so skillfully supported us through this work.

Sincerely,

Co-Chairs of Health Canada's Expert Task Force on Substance Use

Carol Hopkins

Dr. Kwame McKenzie

Mike Serr

Truth and Reconciliation in Canada's Drugs and Substances Strategy

The children emerge in 2021 to tell the truth, will the truth be heard this time?

During the mandate of the Expert Task Force, 215 Indigenous children were discovered in an unmarked grave at the largest residential school in Canada, located at Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc, Kamloops, British Columbia. A reminder to Canada of the intergenerational trauma carried by the many families who survived the residential school system is a root cause of problematic substance use. From a spirit centred Indigenous worldview, it is said the Great Spirit and our Mother the Earth ensured the children would be found at this time. A reminder that while the world begins to emerge from the pandemic, we cannot ignore the truth and must act to ensure Drug Policy includes attention to trauma.

For First Nations:

- Who have a history of trauma, the odds of using opioids in a harmful way are 2.9 times greater than those who do not have a history of trauma.

- Who are experiencing grief and loss, the odds of using opioids in a harmful way are 2.8 times greater than those who did not experience grief or loss.

Canada’s colonial policies and systems cause harm to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people, families, and communities by disconnecting them from the strengths held within their nationhood, language, land, and culture. For far too long, policies and resource allocations to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people have been constrained by deficit-based decision-making, inadequate funding formulas, and an epistemic racism that seeks to erase the value of Indigenous and sacred knowledge.

This systemic racism has perpetuated the legacy of intergenerational trauma and entrenched a public mindset that Indigenous people are incapable of managing themselves and their own programs and communities. Furthermore, because of this denial of equitable resourcing and of mechanisms to address jurisdictional chasms and erase the perceived "option" for responding to the needs of Indigenous people, these communities have been left without relevant resources to answer the acuity of need related to drugs and alcohol.

The UN Sustainable Development Goals, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, and the Truth and Reconciliation Calls to Action all express the importance of the social determinants of health, promote the right to mental health and well-being, with equity and access to quality health care as the means to extend life expectancy for Indigenous peoples of Canada.

- First Nations who have positive role models or mentors in their life, are 2.9 times less likely to use opioids in a harmful way than for those who do not have these meaningful relationships in their life.

- First Nations who believe that their cultural identity matters are 2.3 times less likely to use opioids in harmful way than for those who do not hold this belief.

Reconciliation for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people, families and communities in Canada requires equitable resource capacity to ensure access to distinctions-based services that are culture- and land-based; a trauma informed continuum of care; harm reduction services; and evidence informed by people who use drugs and alcohol. Reconciliation also requires availability and access to the right services for Indigenous people within the criminal justice system, Indigenous women and gender diverse individuals, Indigenous people living with HIV, economically disadvantaged Indigenous individuals, Indigenous youth and elderly, Indigenous people with disabilities such as FASD, and Indigenous people who are disproportionately impacted by environmental emergencies which detach them from safety. Indigenous people are disproportionately represented in each of these circumstances because of inter-generational trauma, transmitted through social factors and possibly epigenetic changesNote de bas de page 1, that has at its source harmful policies without adequate resources to respond. Harmful policies are not limited to drug policies, they encompass the full spectrum of colonialist policies, most notably the Indian residential school system whose harms continue to reverberate through First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities to this day.

Immediate, comprehensive policy change is needed to redress the historical and ongoing harms to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people, families, and communities. This change must be supported with resources commensurate with the needs. Every day lost is another day of potentially irreparable harms. Progress on this comprehensive policy change will require meaningful measurements of change, and must ensure high-quality, culturally relevant, disaggregated and distinctions-based data is available and accessible to Indigenous communities.

Executive summary

This report presents the conclusions and recommendations from the second part of the mandate of the Health Canada Expert Task Force on Substance Use. The Task Force met, heard presentations, reviewed documents, and deliberated on recommendations on the Federal Government's Drug Policy as articulated in a draft Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy (CDSS) from May 5th to June 9th, 2021.

The Task Force considered six specific questions relating to how the draft CDSS articulates the problem of substance-use harms in Canada; its overall goals, principles and objectives; its four pillars of prevention, treatment, harm reduction, and enforcement, and the evidence base; its priority areas; how to better support populations most at-risk; and any other issues or areas that should be included. The Task Force used the questions to structure its discussions, then selected a broader, more strategic approach to presenting its recommendations.

The Task Force wishes to emphasize five key messages related to Canada's substance strategy:

- Canadian policy on substances must change significantly to address and remove structural stigma, centre on the health of people who use substances, and align with current evidence.

- Bold actions are urgently needed, including decriminalization, the development of a single public health framework which regulates all substances, and the expansion of safer supply.

- We need made-for-Canada solutions that are tailored to the specific historical, cultural, social, political, and geographic contexts of Canada's diverse population groups.

- National leadership is essential to ensure that there are standards for the array of supports and services that people in Canada who use substances should be able to access.

- Canada must make new and significant investments so that the impacts of substance use can be adequately addressed.

The Task Force's recommendations in response to the specific questions it was asked about the CDSS are divided into two sections: recommendations on how to articulate the problem of substance-use harms in Canada, and recommendations on the way forward.

The Task Force recommendations on how to articulate the problem are as follows:

Policy-related harms

- Provide more context on policy-related harms, the impacts of social determinants of health, and historical harms and their persistent, intergenerational effects.

- Describe the impact of inadequate regulation of pharmaceuticals, tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and illegal substances on Canada's substance issue, and acknowledge that alcohol currently causes more harms than the substances covered by the CDSA.

Substance-related harms

- Broaden the definition of substance-related harms.

- Acknowledge and describe the disproportionate and distinct harms experienced by the Black population of Canada.

Substance use and people who use substances

- Consider and describe the full spectrum of substance use to provide a more complete and nuanced understanding of the situation.

- Recognize the many profiles of people who use substances and avoid language that reinforces stigma.

Underfunding and lack of services

- Acknowledge and describe the lack of resources and services for people who use substances or who have a substance use disorder.

The Task Force recommendations on the way forward are the following:

Legal regulation

- Include as a core priority of the CDSS to immediately develop and implement a single public health framework with specific regulations for all psychoactive substances, including currently illegal drugs as well as alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis. This framework should aim to minimize the scale of the illegal market, bring stability and predictability to regulated markets for substances, and provide access to safer substances for those at risk of injury or death from toxic illegal substances.

Safer supply

- Include as an urgent priority of the CDSS developing, implementing, and evaluating a comprehensive emergency response strategy to scale up access to safer alternatives to the toxic illegal drug market in partnership with people with lived and living experience and the organizations that represent them.

Funding

- Provide sufficient and ongoing funding for the strategy.

Reducing stigma

- Include an objective related to reducing stigma.

- Define the role of enforcement as a means to clearly support the aims of the public health framework and legal regulation by focussing on criminal organizations and the illegal toxic drug supply.

Equity

- Make equity a core principle and equity, anti-racism and anti-colonialism a priority area in the new CDSS.

National leadership

- Include as an objective the implementation of national standards for providing supports to people who use substances, including harm reduction services, and describing the role of Provinces and Territories in our system and how Health Canada will work to ensure supports meet national standards across the country.

- Include an objective related to assessing, acknowledging, reducing, and addressing policy-related harms.

An integrated approach

- Remove the notion of "pillars" from the strategy and replace it with a more holistic and integrated approach that better represents the interconnectedness of the different areas for action.

- Frame the overall aim of the strategy as a health promotion approach to substance use and minimizing harms.

- Articulate harm reduction as an effective, evidence-based, non-judgemental public health approach for individuals who use substances, integrated into a full continuum of health and social services including housing.

- Include a full continuum of harm reduction, treatment and recovery care and services.

- Include labour-market measures as part of an integrated approach to support certain populations.

- Align and integrate Canada's international policy with its domestic policy on substances.

Introduction

This is the second of two reports prepared by the Health Canada Expert Task Force on Substance Use, established to provide Health Canada with independent, expert advice and recommendations on:

- potential alternatives to criminal penalties for the simple possession of controlled substances, with the goals of reducing the impacts of criminal sanctions on people who use drugs, while maintaining support for community and public safety; and

- the federal government's drug policy, as articulated in a draft Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy (CDSS), with the objectives of further strengthening the government's approach to substance use.

The Task Force convened for the first time on March 10, 2021 and submitted its first report to the Associate Assistant Deputy Minister, Controlled Substances and Cannabis Branch of Health Canada on May 6, 2021. Key findings and recommendations highlighted in the first report of the Task Force should particularly be kept in mind when reading this second report. Specifically, the Task Force found that criminalization of simple possession causes harms to Canadians and needs to end. The Task Force was mindful of five core issues when making recommendations: stigma; disproportionate harms to populations experiencing structural inequity; harms from the illegal drug market; the financial burden on the health and criminal justice systems; and unaddressed underlying conditions.

The Task Force also considered Canada's obligations under international treaties, lessons learned in other jurisdictions, the important issue of safety, supports for community, recent developments under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA), and the broader Canadian legal framework.

The Task Force made four recommendations related to decriminalization and regulation, and four related recommendations (See Appendix C). In addition to recommending an end to criminal penalties and coercive measures for simple possession and consumption of substances, the Task Force recommended that all substances - including substances currently under the CDSA, tobacco, cannabis, and alcohol - be integrated under a single public health framework of legally regulated substances. This recommendation has profound implications for a new CDSS, which will be examined further in this report.

This second report presents the recommendations and advice of the Task Force to strengthen the government's approach to substance use. Although it can be read independently, it builds on the first report and should be interpreted within the context of that first report.

Task Force members

Membership list and bios available in Appendix A.

Approach and methodology

Overview

The Task Force was provided with a draft Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy (CDSS) document for its review and feedback. The version of the CDSS that was reviewed by the Task Force was dated August 2020.

The Task Force was asked to respond to six specific questions about the CDSS:

- Do we have the right articulation of the problem regarding substance-use harms in Canada?

- Does the CDSS have the right overall goals, principles and objectives?

- Are there any gaps across the four pillars of the strategy (prevention, treatment, harm reduction, and enforcement) and the evidence base?

- Do we have the right priority areas moving forward?

- How can we better support populations most at-risk of substance use harms through the CDSS?

- Are there any other issues or areas we should include in the CDSS?

The Task Force structured many of its discussions based on these questions but agreed in the end to present a broader set of recommendations that are not all specifically tied to the questions or to the draft CDSS provided by Health Canada.

The work took place over a series of six meetings, on May 5, 12, 19 and 26 and June 2 and 9, 2021. Meetings lasted between two (2) and five (5) hours and were held using an online web conferencing tool. The Task Force Secretariat prepared records of proceedings of each of the meetings for the use of Task Force members.

Various documents and briefs were shared with Task Force members and reviewed before meetings. Task Force members also collaborated and exchanged asynchronously between meetings using email and the Government of Canada's GCcollab platform.

Presentations and submissions

The following organizations and individuals presented to the Task Force in this second part of its mandate:

May 5, 2021

- Health Canada

- Thunderbird Partnership Foundation

May 19, 2021

- Dr. Jeffrey Turnbull, Ottawa Inner City Health

- BC Yukon Association of Drug War Survivors Women's Committee

May 26, 2021

- Community Addictions Peer Support Association (CAPSA)

- Black Health Alliance

June 2, 2021

- Dr. Elaine Hyshka

Key messages

Building on the Task Force recommendations in its first report, the Task Force would like to emphasize the following key points about Canada's substance-related policies and strategy:

- Canadian policy on substances must change significantly to address and remove structural stigma, centre on the health of people who use substances, and align with current evidence. People who use substances are not the problem. Social, historical, and political systemic forces (including colonisation, social inequity, and racism) and inadequate policies (such as criminalization of simple possession, an extremely toxic unregulated illegal drug market, and inadequate regulation of alcohol) are the fundamental drivers behind toxicity deaths and many other substance use harms. New solutions, beginning with legal regulation, should focus on the social determinants of health, public health, and the human rights of people who use substances. The development and implementation of these solutions must involve people with lived and living experience and the organizations that represent them, given that they are the ones that will be most affected.

- Bold actions are urgently needed. The war on drugs has led to what ends up looking like a war on people who use drugs. People are dying every day, and the situation in Canada, already particularly deadlyNote de bas de page 2, is getting worse, not betterNote de bas de page 3. Canada has the fastest growing rate of overdose mortality in the world. This is despite the fact that Canada also has a broad set of overdose prevention interventions that are legally available, including naloxone distribution, drug checking services, and supervised consumption sites. While these may account for the fact that Canada's overall rate of overdose mortality is slightly lower than the United States (which has the highest rate in the world), the modest successes that these interventions have achieved to date are dwarfed by the fact that Canada's overdose epidemic is worsening at an alarming rateNote de bas de page 4. Canada's current drug policies are failing to keep people alive and must be immediately transformed through decriminalization, the development of a single public health framework which regulates all substances, and the expansion of safer supply.

- We need made-for-Canada solutions that are tailored to our specific historical, social, political, and geographic contexts. Although we can learn from other jurisdictions, Canada must develop its own solutions, ones that recognize the sovereign rights of Indigenous peoples and support their governments in providing appropriate prevention, harm reduction, treatment, and recovery approaches; that ensure equitable protections and outcomes for other groups disproportionately impacted by substance use harms, including but not limited to women, Black populations, and racialized populations; and that take into consideration our country's size and the distribution of our population between North and South, urban and rural.

- National leadership is essential. The government of Canada must take the lead to reach across political and jurisdictional boundaries and develop a consensus on national standards for the continuum of equitable, people-centred services and resources needed to ensure that all people in Canada who use substances have access to comprehensive and appropriate protections and supports.

- Canada must make new and significant investments to address this issue. These should be a distinct funding stream separate from mental health, to reinforce the importance and urgency of this issue.

More specific recommendations are included in the following sections related to how the problem should be articulated in the strategy, and where in a new Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy (CDSS) should focus moving forward.

Articulation of the problem

Although the articulation of the problem in the draft CDSS appropriately frames the issue as broad and systemic, the Task Force found some important gaps and challenges that must be addressed. The CDSS needs to balance clear, concise statements to facilitate understanding with recognizing the complexity of the issue and the importance of an integrated approach.

The Task Force was particularly concerned about the strategy's silence on policy-related harms, and the manner in which the draft CDSS discusses substance related harms, substance use, and people who use substances.

Policy-related harms

Recommendation: Provide more context on policy-related harms, the impacts of social determinants of health, and historical harms and their persistent, intergenerational effects.

Policy-related harms, and specifically the harms resulting from criminalization of simple possession, need to be acknowledged as a significant part of the problem. International expert groups have shown that the prohibition of certain drugs has led to increased criminal activity and a very robust and unregulated highly toxic drug market. Prohibition has also promoted stigma and discrimination and undermined the human rights of people who use substances. The policy of prohibition has been identified as a major source of harm to people who use drugs.Note de bas de page 5

The articulation of the problem should also more clearly acknowledge and describe the historical, intergenerational, and persistent harms resulting from historical and ongoing structural racism in Canada.

Recommendation: Describe the impact of inadequate regulation of pharmaceuticals, tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and illegal substances on Canada's substance issue, and acknowledge that alcohol currently causes more harms than the substances covered by the CDSANote de bas de page 6.

In addition to the harms caused by the highly toxic illegal drug market, significant harm has been caused by the over-prescription or aggressive marketing of currently legal substances as healthy and beneficial. Access to pharmaceutical alternatives for the toxic drug supply is part of safer access, but more access does not necessarily equate with fewer harms overall, as evidenced, for example, by Canada's experience with alcoholNote de bas de page 7.

Substance related harms

Recommendation: Broaden the definition of substance-related harms.

The full scope of substance-related harms must be understood to create a solid foundation for the strategy. These harms go well beyond substance-related disorders as defined by the American Psychiatry Association (APA) DSM 5. Substance-related harms encompass a much wider range of harms than individual health consequences directly linked to substances. They include, for example, stigma, disproportionate harms to populations experiencing structural inequity, violence related to the illegal drug market, a high financial burden on the health and criminal justice system, and unaddressed underlying conditions.Note de bas de page 8

Recommendation: Acknowledge and describe the disproportionate and distinct harms experienced by Black people and Black communities.

The draft CDSS makes no mention of Black populations in Canada even though Black people have a higher rate of drug-related persecution than other populations, despite not using drugs more than these other populations. The term anti-Black racism was coined in Canada to capture the systemic nature of the disproportionate exposure to, and impacts of, negative social determinants of health on Black people in Canada. The colonial history of our country, the transatlantic slave trade, and racial discrimination in institutions, public services, policy, and laws explain why Black people in Canada are less likely to be in the boardroom, are more likely to live in poverty, are less likely to perform well at school, have higher rates of unemployment, receive lower rates of pay for comparable skills, are more likely to live in precarious housing, and have higher rates of contact with the criminal justice system. While the Black population in general have increased risks of substance use harms, different social inequities may intersect and increase risks of specific harms for groups within the Black populations. For instance, criminalization of drug use leads to Black women being disproportionately policed in child welfare as well as globally being the fastest growing incarcerated populationNote de bas de page 9, and Black 2SLGBTQQI people face high rates of trauma, stigma, and policing.

Substance use and people who use substances

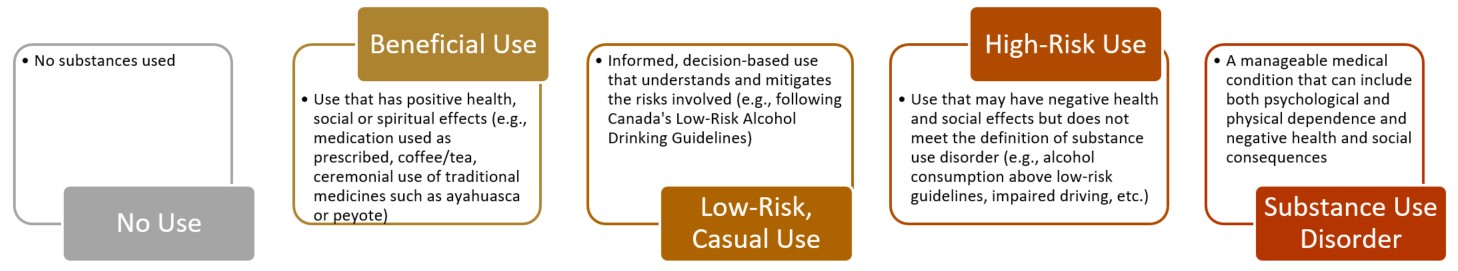

Recommendation: Consider and describe the full spectrum of substance use to provide a more complete and nuanced understanding of the situation.

In the draft CDSS, the language describing substance use as problematic sometimes seems to centre on use being chronic or habitual, which is not an accurate portrayal of problematic substance use. The document presents an oversimplified picture of the range of substance use situations by differentiating solely between low-risk and high-risk use.

The Task Force recommends that the CDSS include and be based on a more nuanced understanding of the full spectrum of substance use, as depicted in the following graphic adapted from A Public Health Approach to Drug Control in CanadaNote de bas de page 10. It should also account for the reality that people can move from one type of use to another, that they do not do this in a sequential way, and that the threshold for considering different types of use low or high risk may vary for different substances.

Figure 1 - Text description

Chart displays a spectrum of substance use, from no use to substance use disorder. Beginning with no substances used, the chart moves to “beneficial use”, a use that has positive health, social or spiritual effects. Following beneficial use is “low-risk, casual use,” defined as informed, decision-based use that understands and mitigates the risks involved. Next is “high-risk use,” which is use that may have negative health and social effects but does not meet the definition of a substance use disorder. Finally, “substance use disorder” is explained as a manageable medical condition that can include both psychological and physical dependence and negative health and social consequences.

Recommendation: Recognize the many profiles of people who use substances and avoid language that reinforces stigma.

"People who use substances" is a broad category that encompasses a wide range of situations and experiences. A key to success is to include in the scope of the strategy all people who use substances - in other words, most of the Canadian populationNote de bas de page 11.

Among people who use substances, there is a relatively small subset with substance use disorders and high acuity needs, a larger number of people who are at risk and seeking formal care, an even larger population that is at risk but not seeking formal care, and finally a healthy population with no risk factors and no need for care. A comprehensive strategy must recognize all these sub-populations in order to adequately address their different situations and needs.

In addition, it is important to note that stigma is fed by languageNote de bas de page 12, and by the idea that an individual's drug use, in and of itself, is causing harm to others. When discussing substance-related harms, the strategy should use explicit language that focuses on the harms themselves and does not stigmatise people who use substances. Likewise, when describing problematic substance use, it is important to keep the focus on problems related to use, not on individuals who use, or how they use.

Underfunding and lack of services

Recommendation: Acknowledge and describe the lack of resources and services for people who use substances or who have a substance use disorder.

Services for people who use substances are typically categorized under "mental health and addiction services" and these services are chronically underfundedNote de bas de page 13Note de bas de page 14. With the system struggling to meet the more acute needs, access to services for people with substance use disorder is inadequate, and services for people at risk but not diagnosed with a disorder are almost non-existent. People who want to talk to an expert about their substance use have nowhere to turn, and there is a lack of accessible information and guidelines on substance use.

The way forward

The draft CDSS reviewed by the Task Force included goals, principles, objectives, pillars, and priority areas. While the document contains many useful ideas and strategies, the Task Force considers that it will require significant change because the draft assumes that the status quo, prohibiting certain substances by making them illegal under the CDSA, will continue.

Given the scale, scope, and urgency of the problem, the Task Force wishes to highlight two core priorities, legal regulation and a scaled up safer supply emergency response, in addition to a number of other goals, priorities, and principles that should be included in a comprehensive federal strategy for a public health approach to psychoactive substances in Canada.

Legal regulation

Recommendation: Include as a core priority of the CDSS to immediately develop and implement a single public health framework with specific regulations for all psychoactive substances, including currently illegal drugs as well as alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis. This framework should aim to minimize the scale of the illegal market, bring stability and predictability to regulated markets for substances, and provide access to safer substances for those at risk of injury or death from toxic illegal substances.

Given the evidence of increasing toxicity within the illegal drug market, particularly since 2015, and the tens of thousands of Canadians from all walks of life who have lost their lives as a resultNote de bas de page 15, there is clear urgency for this work. The work should be undertaken in close collaboration with people with lived and living experience and the organizations that represent them, civil society organizations, and other key stakeholders.

Effective regulation must strike the right balance between the extremes of prohibition and complete deregulation, which are both associated with increased social and health harmsNote de bas de page 16.

This regulatory framework shouldNote de bas de page 17Note de bas de page 18Note de bas de page 19:

- Engage those most impacted by current approaches that criminalize people who use drugs.

- Focus on protecting and promoting public health by stabilizing drug markets and clearly establishing regulations for access.

- Emphasize using effective policy levers to limit harmful patterns of use and avoid inducing demand.

- Encourage shifting use to lower potency products.

- Enhance public health surveillance and intervention options.

- Limit commercial interests and prioritize non-profit models of delivery.

- Apply best practices and rigorous evidence to develop specific and effective regulations for each class of substances-including alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, pharmaceutical drugs, and the range of currently illegal drugs-within a public health framework.

In developing and implementing this new framework, the Government of Canada should consider how to redirect and reallocate resources currently dedicated to the criminal prosecution related to drug possession. It should also use its influence with other countries to increase pressure for the evolution of international agreements to facilitate regulation.

Safer supply

Recommendation: Include as an urgent priority of the CDSS developing, implementing, and evaluating a comprehensive emergency response strategy to scale up access to safer alternatives to the toxic illegal drug market in partnership with people with lived and living experience and the organizations that represent them.

An expert committee should be convened within three months of this report to lead the design of a national safer supply program, with the goal to increase access to safer supply for up to one (1) million Canadians at risk of death from drug toxicity. This expert committee could:

- Develop new pathways for outreach, screening, and drug distribution, and work to implement them. Services including all pathways to support optimum health must be visible and readily available for those seeking these additional supports.

- Develop strategies to use existing health infrastructure as sites for safe supply distribution including pharmacies, public health clinics, harm reduction services, and other appropriate service locations.

- Develop a plan for deploying an expanded health response with resources commensurate with those allocated to responding to other emergencies such as COVID-19.

- Identify legal changes that need to take place to enable acceleration of safer supply dispensing to Canadians.

- Determine the most effective regulatory and legal changes necessary to quickly respond to the toxic poisoning crisis including Section 56 exemptions and new regulations where needed.

- Initiate a process to engage people with lived and living expertise in using criminalized substances and harm reduction to substantively collaborate on all aspects of the emergency safer supply strategy.Note de bas de page 20Note de bas de page 21Note de bas de page 22Note de bas de page 23

Funding

Recommendation: Provide sufficient and ongoing funding for the strategy.

Funding should be equivalent to the scope of the issues, should be allocated to various sectors commensurate with evidence of impact, and it should be recurring so that supports continue even when governments change. Current policies are currently costing Canada huge amounts. In 2017, the estimate of healthcare costs in Canada related to the use of opioids and other depressants and cocaine and other stimulants was one billion dollarsNote de bas de page 24, and the cost of policing and legal proceedings related to drug possession exceeded six billion dollarsNote de bas de page 25. Although a significant initial investment will be required to reshape the system and address the drug toxicity crisis, costs can be expected to decrease over time as the impact of new, more effective policies is felt.

Reducing stigma

Recommendation: Include an objective related to reducing stigma.

In its first report, the Task Force identified stigma as a core issue that multiplies harms and increases the risk of negative outcomes. Reducing stigma takes time and sustained effort because it requires changing underlying beliefs that have been built and reinforced over many years. Implementing laws that make it unlawful to discriminate against people who use substances can accelerate the process by providing incentives for behaviour change. Changing public messaging and use of language are also important, and public education more generally can also play a role. Efforts to reduce stigma should draw on work on stigma reduction for other health conditions, for example HIV/AIDS, and on anti-oppression work such as that of Anne BishopNote de bas de page 26.

Recommendation: Define the role of enforcement as a means to clearly support the aims of the public health framework and legal regulation by focussing on criminal organizations and the illegal toxic drug supply.

Enforcement can be an effective tool in supporting equitable, evidence-based regulations and policies, however it has historically been associated with the policing and criminal prosecution of low-level offences, leading to significant harms for people who use substances. With the implementation of a legal regulation framework for all substances, the focus of enforcement will naturally shift to inspecting legal institutions to ensure that regulations are enforced, and to reducing the importation, manufacture, and trafficking of currently illegal substances and their precursors.

Equity

Recommendation: Make equity a core principle and equity, anti-racism and anti-colonialism a priority area in the new CDSS.

Given the disproportionate harms to specific populations, and particularly Indigenous, Black, and racialized people, there is significant, urgent work to be done to improve equity of access to quality supports and services.

Several approaches could help facilitate increased equity:

- Undertake a racial equity impact assessment of substance use policies and develop a mitigation strategy to decrease any unintended inequitable impacts. Require that all services funded by the Federal government have undertaken a health equity audit and needs assessment and act on the outcomes to ensure that supports better serve communities.

- Require that all services funded by the Federal government collect appropriate data that so they can demonstrate to their funder that they are meeting the needs of their population.

- Require that Federal policies and federally funded services be developed in partnership with Black communities, with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis leadership, and include the voices of people with lived and living experience of substance use.

- Invest in programs created and run by communities to prevent substance-related harms. Empower communities to develop and manage programs that work for them, with the understanding that communities are not monolithic, experience multiple intersecting axes of oppression, and require leadership and programs that integrate and utilize intersectional approaches.

- Increase funding for prevention and harm reduction for traditionally underserved populations.

- Require the collection, analysis and dissemination of racially disaggregated data on substance use at the population level as collected by existing government surveys (e.g. Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CTADS)/ Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CSTADS).

- Require the collection, analysis and dissemination of racially disaggregated data on criminal justice contact resulting from drug offences.

- Implement an equitable and inclusive research and evaluation program that specifically recruits, involves, and builds capacity in marginalized populations to build, gather and use evidence. This program should aim to improve access to socio-demographic data and improve our understanding of the needs and approaches that promote equitable services and supports and improved health outcomes for marginalized populations.

- Support an accreditation standard for services which includes a requirement that services have the capacity to offer equitable access and outcomes of services for the population - this could include training in Anti-Black racism and protocols and processes within organizations that promote authentic community engagement and community governance.

- Make protection of the rights and freedoms of all people who use substances a central goal or principle.

Increasing equity will help keep communities safe, by keeping community members who use substances healthy and safe, and by giving communities a voice in defining what safety means for them.

National leadership

Recommendation: Include as an objective the implementation of national standards for providing supports to people who use substances, including harm reduction services, and describing the role of Provinces and Territories in our system and how Health Canada will work to ensure supports meet national standards across the country.

Provincial and Territorial governments are responsible for addressing the needs of their populations, and of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people in particular, but the current system does not provide sufficient accountability. Strong national leadership and support is needed to ensure that all parties meet their obligations, and that all people who live in Canada benefit from equitable access to supports and services and health outcomes.

National standards should acknowledge the strengths in First Nations, Inuit and Métis culture and language that are protective and facilitate wellness, and should include cultural and land-based practices.

Standards will require implementing and reporting on key metrics to support accountability in the system. The implementation of national standards should also include plans and resources for the education and training of health care professionals.

This federal leadership role would best be accomplished by establishing a separate, properly funded Branch with a sole focus on substance use health (see glossary), separate from mental health, that has within its mandate all substances, including tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and the substances currently under the CDSA. Such an organization would be responsible for knowledge mobilization and evidence-based action, collecting and coordinating national data, translating and sharing it, and creating policy recommendations based on this evidence.

Recommendation: Include an objective related to assessing, acknowledging, reducing, and addressing policy-related harms.

There is a vast body of research on policy related harms, and the federal government should take a leadership role in acknowledging and addressing them. Potential wording for such an objective could be "The significant harms that stem from current policy frameworks are assessed and acknowledged, and measures to minimize and redress those harms have been implemented in collaboration with people with lived and living experience and other key stakeholders."

This work should not stop at correcting past harms, it is also important to put measures in place to detect and rapidly correct any unintended harmful consequences of new policies.

An integrated approach

Recommendation: Remove the notion of "pillars" from the strategy and replace it with a more holistic and integrated approach that better represents the interconnectedness of the different areas for action.

The framing of the draft strategy as pillars - prevention, treatment and recovery, harm reduction, and enforcement - with a supporting evidence base, suggests discrete components that can work independently, and the "pillars" themselves are more closely tied to a criminal justice approach than a population health approach. The substance use health model adopted by CAPSANote de bas de page 27 and the First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum FrameworkNote de bas de page 28 are examples of circular presentations shared with the Task Force that reflect and reinforce how all the dimensions of a strategy must work together for success. Other approaches the Task Force discussed could be to present the main thrusts of the strategy as intersecting circles as in a Venn diagram, or to borrow the population health approach framework of primary, secondary, and tertiary preventionNote de bas de page 29. This latter approach could enable a stronger focus on the social determinants of health and facilitate better integration of prevention, harm reduction, and treatment and recovery into a continuum of supports and services.

Recommendation: Frame the overall aim of the strategy as a health promotion approach to substance use and minimizing harms.

There is increasing evidence that taking a problem-centred approach is less effective than focusing attention and energy on a positive goal. This has already been recognized in other domains like physical health and mental health, where health promotion is a central element of the overall strategy.

Public education will be required to minimize harms and achieve longer-term goals of substance use health. Public education should include educating the public about substances and their risks, and the toxic substances circulating in the illegal market.

Recommendation: Articulate harm reduction as an effective, evidence-based, non-judgemental public health approach for individuals who use substances, integrated into a full continuum of health and social services including housing.

Harm reduction supports both social justice for people criminalized for their substance use and an evidence based public health response to substance use in the community. Harm reduction must shift from exemptions to existing policy to an accepted and central intervention with a full continuum of supports and care.

Evidence shows that harm reduction does not increase or encourage substance use. Harm reduction strategies and services can lessen the negative consequences associated with substance use, including social, physical, emotional, or spiritual concerns. It has been shown that people who engage in harm reduction services are more likely to engage in ongoing treatment following access to these services. Some harm reduction initiatives have also been successful in reducing blood-borne diseases such as HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C and in decreasing death rates from drug overdoses.Note de bas de page 30

Because harm reduction requires that interventions and policies designed to serve people who use drugs reflect the specific needs of individuals and communities, there is no universal formula for implementing harm reduction. Successful implementation requires that we invest in community-created and community-run harm reduction programs and empower communities to develop and manage programs that work for them, knowing that communities are not monolithic, that they experience multiple intersecting axes of oppression, and that they need leadership and programs that incorporate and use an intersectional approach (e.g., 2SLGBTQQI, Black communities, Indigenous communities, sex workers).

Recommendation: Include a full continuum of harm reduction, treatment and recovery care and services.

Substance-use disorder is a condition with many manifestations that presents a high likelihood of reoccurrence, and for those who want support there will be a need for access to treatment and recovery programs that go from short-term, controlled used, to abstinence-based programs, to long term follow up and supports. Different treatment options should be available depending on the presence and severity of concurrent disorders. This treatment and recovery-oriented system of care should be widely available, covered for all, and provide quality services aligned with evidence. It should also draw on the wisdom of Indigenous people, who have created cultural and land-based programs that are successful in dealing with the root causes of substance use.

Recommendation: Include labour-market measures as part of an integrated approach to support certain populations.

Where employment intersects with substance use, stigma plays a big role in preventing people from seeking help for substance use disorders. This is particularly the case for health care workers, for people who work in the criminal justice system, and people who work in physically demanding occupations such as construction workers. The current system of addiction care is neither well understood nor well integrated. There are also cultural and labour market barriers to obtaining needed supports, for example a lack of paid sick days or protections like seniority.

Current care is not consistent with Canada's health principle of universality and equal access. Access to quality treatment and recovery programs is uneven, private industry programs are expensive, there is too much focus on residential programs, and there are long waiting lists for publicly funded programs. A full spectrum is needed, with standards across the spectrum, and related measures that facilitate access to appropriate supports.

Recommendation: Align and integrate Canada's international policy with its domestic policy on substances.

Canada could play a significant role in advancing evidence-informed harm reduction internationally and in supporting the implementation of more equitable and effective practices around the world. Advancing these issues on the international stage would also facilitate mutual support with other jurisdictions.

Appendix A: Task Force member bios

Carol Hopkins (Co-Chair), CEO of the Thunderbird Partnership Foundation (a division of the National Native Addictions Partnership Foundation)

Dr. Kwame McKenzie (Co-Chair), CEO of Wellesley Institute, Director of Health Equity at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Full Professor in Psychiatry at the University of Toronto and consultant with the World Health Organization

Mike Serr (Co-Chair), Chief Constable, Abbotsford Police Department; Chairperson of the Drug Advisory Committee, Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police (CACP), and Chair of the CACP's Special Purposes Committee on the Decriminalization of Illicit Drugs

Serge Brochu, PhD, Professor, École de criminologie at the Université de Montréal

Deirdre Freiheit, President and CEO, Shepherds of Good Hope (SGH) and Shepherds of Good Hope Foundation

Gord Garner, Executive Director, Community Addictions Peer Support Association

Charles Gauthier, President and CEO, Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association

Cheyenne Johnson, Executive Director, British Columbia Centre on Substance Use (BCCSU)

Harold R. Johnson, Elder, Advisor and Ambassador, Northern Alcohol Strategy Saskatchewan, Former Crown Prosecutor

Damon Johnston, Chair, Addictions Foundation of Manitoba, and President, Aboriginal Council of Winnipeg

El Jones, Spoken Word Poet, Educator, Journalist, and a Community activist living in African Nova Scotia

Mae Katt, Primary Health Care Nurse Practitioner, Thunder Bay and Temagami First Nation

Robert Kucheran, Chairman of the Executive Board, Canada's Building Trades Unions

Frankie Lambert, Communications Officer, AQPSUD (Association Québécoise pour la promotion de la santé des personnes utilisatrices de drogues / Québec Association for Drug User Health Promotion)

Anne Elizabeth Lapointe, Executive Director, Maison Jean Lapointe and Addiction Prevention Centre

Dr. Shaohua Lu, Addiction Forensic Psychiatrist, Clinical Associate Professor, University of British Columbia

Donald MacPherson, Director, Canadian Drug Policy Coalition

Akwasi Owusu-Bempah, PhD, Assistant professor, Department of Sociology, University of Toronto

Hawkfeather Peterson, President of BCYADWS (BC/Yukon Association of Drug War Survivors), Regional Peer Coordinator of the Northern Health Authority in BC

Dan Werb, PhD, Executive Director, Centre on Drug Policy Evaluation, MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael's Hospital, Assistant Professor, University of Toronto Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, and Assistant Professor, University of California San Diego Division of Infectious Diseases and Global Public Health

Appendix B: Recommendations from the first report

In its first report, dated May 6, 2021, the Expert Task Force on Substance Use made the following recommendations on alternatives to criminal penalties for simple possession of controlled substances and related issues.

Decriminalization and regulation

1. Elimination of all penalties and coercive measures

Recommendation: The Task Force unanimously recommends that Health Canada end criminal penalties related to simple possession and most also recommend that Health Canada end all coercive measures related to simple possession and consumption.

It is our expert opinion that penalties of any kind for the simple possession and use of substances are harmful to Canadians. Substance use should be managed as a health and social priority, with a focus on the social determinants of health, and not through criminal or civil sanctions.

As to coercive measures, the evidence on mandatory, coerced or forced treatment, including drug treatment courts, is mixed, and success rates are typically lowNote de bas de page 31Note de bas de page 32. Furthermore, decriminalization or regulation may be less effective and may amplify structural inequities if conditions and penalties are such that people who use drugs are at risk of being criminalized for non-compliance with civil penalties.

This does not preclude offering support or voluntary treatment as options in addition to or instead of penalties under other Acts.

Implementation and pathways for youth and school-age children and their families need to be further explored and developed to ensure the necessary supports are in place for this population.

2. Legislative change

Recommendation: Most Task Force members also recommend that the Government of Canada immediately begin a process of legislative change to bring the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA), the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act (TVPA), the Cannabis Act, and any other relevant federal legislation under a single public health legal framework with regulatory structures that are specific to different types of substances.

Regulation of drugs will have the greatest impact on ending the drug toxicity death crisis and minimizing the scale of the unregulated drug market. It will address key drivers of substance toxicity injury and death and facilitate a health promotion approach to substance use. Regulatory structures that are specific to different types of substances will be important to address varying levels of substance toxicity, as well as the unique health and social outcomes of each type of substance.

Bringing all substances together under a single Act will also provide an opportunity to harmonize the regulation of all substances with potential for harm, including alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis, and potentially mitigate harm more effectively through a more consistent and coherent approach.

3. Thresholds

Recommendation: The Task Force recommends that thresholds for simple possession be based on presumption of innocence, and that they be set high enough to account for the purchasing and consumption habits of all people who use drugs.

People who use drugs have different consumption needs and patterns. Some people with substance use disorders need to use more than others because of high tolerance. Some people on low, fixed incomes tend to purchase monthly or biweekly supply when they are paid, which also leaves them in possession of larger than "average" amounts. And individuals relying on the illegal drug market may also purchase larger amounts to minimize their exposure to potential violence. Threshold determinations are of critical importance and processes to consider threshold amounts should be co-led with people with lived and living experience of using drugs.

4. Expungement

Recommendation: As part of decriminalization, the Task Force recommends that criminal records from previous offenses related to simple possession be fully expunged. This should be complete deletion, automatic, and cost-free.

Criminal records expose people who use drugs to discrimination and makes it hard for them to be gainfully employed, which leads to further stigma and marginalization.

Related recommendations

The measures recommended above, while important, will not be sufficient. Further measures are needed to mitigate the harms experienced by people who use substances, and to avoid unintended consequences as policy changes are implemented.

5. Supports for people who use drugs or substances or who are in recovery

Recommendation: The Task Force recommends that Canada make significant investments in providing a full spectrum of supports for people who use drugs or substances or who are in recovery.

Supports could include supervised consumption sites, an array of treatment options, pharmaceutical grade alternatives to illegal street drugs, housing, drug checking services, and other social supports. Access to these supports should be equitable and universal.

There is an urgent need for a safe supply of pharmaceutical grade alternatives to reduce people's exposure to the toxicity of illegal street drugs.

The need for more supervised consumption services, including supervised injection, snorting, smoking, and accommodating assisted injection for those who are unable to inject themselves, is also urgent.

6. Evidence and monitoring

Recommendation: The Task Force recommends the implementation of a more comprehensive and responsive system to rapidly and effectively gather, use, and disseminate evidence about substance use, its effects, and the impacts of government policies on the health and wellbeing of Canadians.

Systems must be in place to monitor the impacts of policies and enable rapid responses to changing circumstances. This is critical to ensure that Canadian substance-related policies are grounded in the best available evidence while also being responsive, adaptive, and effective. The focus of evidence-gathering to date appears to be mostly on substance use harms rather than a health promotion approach to substance use. Correcting this bias is important to ensure that policies are as effective as possible in meeting the needs of Canadians.

More targeted research is needed with marginalized populations, including Indigenous people, Black people, racialized people, and newcomer communities. This will require capacity building in these populations for this work. More also needs to be done to disaggregate existing data on these populations and to publish disaggregated data consistently at the national level and across all provinces and territories.

The evidence collected should be used to strengthen public education, health promotion, prevention, treatment, and protection from contaminated substances.

7. Rights of Indigenous Peoples of Canada, First Nations, Métis, and Inuit

Recommendation: The Task Force strongly urges Health Canada to respect the sovereign rights of the Indigenous Peoples of Canada and support their governments in providing appropriate prevention and treatment approaches.

Whatever changes are implemented must not encroach on Indigenous rights, and First Nations, Métis, and Inuit should be able to self govern and apply their knowledge, culture, and traditional responses to substance use.

Furthermore, legislation and regulation must recognize the authority and sovereignty of First Nations, Métis and Inuit and support them in righting the disproportionate harms that have been inflicted on their people from current policies.

8. Further consultation

Recommendation: The Task Force recommends that Health Canada convene a new committee that centres people with lived and living experience of substance use to provide advice on the implementation of its recommendations.

People with lived or living experience of substance use have unique expertise on substance use and they will be directly impacted by any policy decisions about substance possession and use. Future consultations should ensure that their diverse voices are strongly and equitably represented, including those of specific groups such as Indigenous women, Black people, racialized people, those who are incarcerated, migrants and people without status.

Consultation should also be broadened to include a wider range of voices and perspectives generally, to maximize the potential for successful implementation of eventual decisions.

Appendix C: Glossary of terms

Addiction

A treatable chronic illness involving complex interactions among brain circuits, genetics, the environment, and an individual's life experiences (see substance use disorder).

Decriminalization

Removal of criminal penalties for an activity. De facto approaches are ones that do not require any changes to the laws or regulations. De jure approaches involve changing the laws or regulations.

Drug

For the purposes of this report, "drug" means an illegal or unauthorized psychoactive substance.

Drug toxicity

A poisonous quality of a drug that can cause functional, biochemical, or structural damage to the human body. Toxicity can be acute or chronic; toxicity can cause temporary or permanent physical, cognitive, or psychological injuries, up to and including death.

Equity

The absence of avoidable or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically, or geographically. (WHO)

Harm

A negative consequence to an individual, family, community, or society at large, including direct, indirect, and intergenerational or epigenetic physical and mental health, social, and economic and financial impacts.

Harm reduction

Harm reduction is a public health approach that uses practical strategies and approaches to reduce harms related to substance use. The range of harm reduction strategies includes safer use, managing use, abstinence, addressing the conditions of use in addition to the use itself, and meeting people who use substances "where they're at" not only in terms of substance use but also geographically (e.g., rural and remote communities), socially, culturally, and on their life journey.

People with lived and/or living experience of substance use

People who currently consume or have in the past consumed substances, or their family or community members collectively and directly impacted by the consumption of substances.

People who use drugs

People who consume illegal or unauthorized psychoactive substances.

Recovery

Recovery is a process of change through which people improve their health and wellness, live self-directed lives, and strive to reach their full potential. There are four major dimensions that support recovery:

- Health: overcoming or managing one's disease(s) or symptoms and making informed, healthy choices that support physical and emotional well-being.

- Home: having a stable and safe place to live.

- Purpose: conducting meaningful daily activities and having the independence, income, and resources to participate in society.

- Community: having relationships and social networks that provide support, friendship, love, and hope.

(Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration)

Regulation

Government oversight of production, manufacture, importation, distribution, product promotion, and sale.

Safer supply

A legal and regulated supply of drugs that are traditionally only accessible by medical prescription or through the illegal drug market.

Simple possession

This refers to possession as defined in section 4(3) of the Criminal Code of Canada and referenced by the CDSA:

- a person has anything in possession when he has it in his personal possession or knowingly

- has it in the actual possession or custody of another person, or

- has it in any place, whether or not that place belongs to or is occupied by him, for the use or benefit of himself or of another person; and

- where one of two or more persons, with the knowledge and consent of the rest, has anything in his custody or possession, it shall be deemed to be in the custody and possession of each and all of them.

Social determinants of health

Social and economic factors that influence people's health, such as social status, income, education, employment and working conditions, equitable and timely access to health services and care, the experience of discrimination or racism, etc. These factors are largely outside of an individual's control. For Indigenous populations, determinants of health also include processes of colonization, culture, language, and land.

Stigma

A negative social, political, and cultural attitude toward a group or individual with a distinguishing attribute or behaviour, founded on a deeply held set of false beliefs, and involving overt and covert judgement, oppression, and discrimination. Common causes of stigma are stereotypes, fear, colonizing norms, unequal power dynamics, lack of awareness, and misinformation. Policies and laws often entrench and exacerbate stigma (see structural racism).

Structural racism

A system of public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms that work in various, often reinforcing ways to advantage white people and perpetuate inequity toward people of colour.

Substance

Except when referring to the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA) and its provisions, substance in this report is defined more broadly as a psychoactive substance, i.e., "chemicals that cross the blood-brain barrier and affect mental functions such as sensations of pain and pleasure, perception, mood, motivation, cognition, and other psychological and behavioral functions" (CPHA), and includes controlled substances under the CDSA as well as other unauthorized substances, alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis.

Substance use disorder

A diagnosable, treatable health condition that is categorized from mild, to moderate to severe. Substance use disorders are diagnosed by assessing a complex pattern of symptoms including impaired control, social impairment, risky use, and pharmacological indicators.

Substance use health

An expression adopted by organizations of people with lived and living experience to focus attention on the unique, unmet health service and support needs of people who use substances, which should be considered and addressed in the same way as mental health or physical health needs.

Treatment

Services to identify and address substance use disorders through withdrawal management, pharmacological interventions and/or psychosocial interventions.

Unregulated drug market

The sale and purchase of substances that escapes oversight by the Canadian legal and regulatory system.

Footnotes

- Footnote 1

-

Catalyst, Passing down history: How our biology may play a role in the transmission of trauma.

- Footnote 2

-

WorldAtlas, Highest Overdose & Drug Related Death Rates In The World, 2021

- Footnote 3

-

Government of Canada, Opioid- and Stimulant-related Harms in Canada, March 2021

- Footnote 4

-

Government of Canada, Opioid- and Stimulant-related Harms in Canada, March 2021

- Footnote 5

-

Transform Drug Policy Foundation, The War on Drugs: Are we paying too high a price?

- Footnote 6

-

Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research and the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addictions, Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms 2015-2017, 2020

- Footnote 7

-

Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, Strategies to Reduce Alcohol-Related Harms and Costs in Canada: A Review of Federal Policies, 2019

- Footnote 8

-

Health Canada's Expert Task Force on Substance Use, Report #1, Recommendations on Alternatives to Criminal Penalties for Simple Possession of Controlled Substances, May 2021

- Footnote 9

-

Feminist Review, celling black bodies: black women in the global prison industrial complex, 2005

- Footnote 10

-

Health Officers Council of British Columbia, A Public Health Approach to Drug Control in Canada, 2005

- Footnote 11

-

Harm Reduction International, Regional Overview - North America, 2021

- Footnote 12

-

Community Addictions Peer Support Association, There Is an Urgent Need to Reduce Substance Use Stigma, 2019

- Footnote 13

-

Canadian Mental Health Association, Ending the Health Care Disparity in Canada, 2018

- Footnote 14

-

Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, NNADAP Funding Parity Report: Ontario Region Case Study - Executive Summary, National Native Addictions Partnership Foundation, Inc., 2018

- Footnote 15

-

Government of Canada, Opioid- and Stimulant-related Harms in Canada, March 2021

- Footnote 16

-

Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council's Working Group on Cannabis Legalization-Regulation, An Ounce of Prevention, 2018

- Footnote 17

-

Global Commission on Drug Policy, Regulation - The Responsible Control of Drugs, 2018

- Footnote 18

-

Canadian Public Health Association, A New Approach to Managing Psychoactive Substances in Canada, 2014

- Footnote 19

-

Health Officer's Council of British Columbia, Public Health Perspectives for Regulating Psychoactive Substances: What we can do about Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drugs, 2011

- Footnote 20

-

International Journal of Drug Policy, Consumer protection in drug policy: The human rights case for safe supply as an element of harm reduction, 2021

- Footnote 21

-

Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Addressing the Syndemic of HIV, Hepatitis C, Overdose, and COVID-19 Among People Who Use Drugs: The Potential Roles for Decriminalization and Safe Supply, 2020

- Footnote 22

-

Public Health in Practice, 'Safer opioid distribution' as an essential public health intervention for the opioid mortality crisis - considerations, options and models towards broad-based implementation, 2020

- Footnote 23

-

Canadian Medical Association Journal, A safer drug supply: a pragmatic and ethical response to the overdose crisis, 2020

- Footnote 24

-

Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research and the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addictions, Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms 2015-2017, 2020

- Footnote 25

-

Canadian HIV/Aids Legal Network, Decriminalizing drug possession for personal use in Canada: Recent developments, 2020

- Footnote 26

-

Anne Bishop, Becoming an Ally - Breaking the Cycle of Oppression in People, 2015

- Footnote 27

-

Community Addictions Peer Support Association (CAPSA), Presentation to the Task Force, May 2021

- Footnote 28

-

Government of Canada and Assembly of First Nations, First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework, 2015

- Footnote 29

-

Government of Canada, Implementing the Population Health Approach, 2013

- Footnote 30

-

British Columbia Ministry of Health, Harm Reduction - A British Columbia Community Guide, 2005

- Footnote 31

-

Justice Research and Policy Journal, Drug Treatment Courts: A Quantitative Review of Study and Treatment Quality, 2012

- Footnote 32

-

Department of Justice Canada, Drug Treatment Court Funding Program Evaluation, 2017

Page details

- Date modified: