The state of virtual care in Canada as of wave three of the COVID-19 pandemic: An early diagnostic and policy recommendations

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 3,411 Kb, 88 pages)

- Organization: Health Canada

- Date published: June 29, 2021

- Will Falk BSc., MPPM

- June 29, 2021

Health Canada is the federal department responsible for helping the people of Canada maintain and improve their health. Health Canada is committed to improving the lives of all of Canada's people and to making this country's population among the healthiest in the world as measured by longevity, lifestyle and effective use of the public health care system.

Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Section 1: What happened? Four different perspectives

- Section 2: Provincial/territorial, private sector, and international review

- Section 3: Virtual care policy for Canadians: Six pillars framework

- Section 4: Recommendations, implementation issues and governance

- Table 1: Summary of recommendations

- Acronyms

- Glossary

- Acknowledgements

- Endnotes

- References

Foreword

Jo Voisin and Sandra Cascadden Co-Chairs

FPT Virtual Care Table By e-mail

June 29th, 2021

Dear Jo and Sandra, Attached please find my report to the Federal Provincial Territorial Virtual Care Table: The State of Virtual Care in Canada as of Wave Three of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Congratulations on the excellent discussion amongst the more than 80 participants at the FPT virtual care summit last week. I was so pleased to see them taking on the tough issues for Canadians

This report is an early diagnostique with policy recommendations. It is written at a time in our history when many changes to the health system are still in progress. As such, I ask that you accept it as a work in progress and I appreciated having the ideas improved upon by the FPT Virtual Care Table and others at the summit as well as by individual policy makers who take and improve the recommendations in their jurisdictions.

The report is longer than I had planned. This is in part because of the four different perspectives that emerged as clinicians and administrators struggle with the huge move to virtual care during the pandemic. I have tried to centre the report around the broad agreement that while change was forced upon us by the pandemic it was, in many cases, long overdue.

The Policy recommendations under the six pillars fall into several broad categories that I summarize as follows:

- Care is Care. Virtual care is no longer an adjunct therapy; it is a core part of our publicly- funded health delivery system.

- Key health information components—diagnostic test results, prescriptions, consults, and referrals— should always be created in a usable digital format. When requested by or on behalf of a patient, hospital and physician records, should be provided on demand in a usable digital format as of April 1, 2023.

- Payment policies should not favour one modality of care over another, except when warranted for clinical reasons. Physical, video, phone, and messaging modalities (and other future modalities) should be available to providers and patients at their choice.

- Governments must switch their mindset from paying for particular technologies to paying for desired outcomes and services (allowing providers and patients to make technology choices within a standards framework).

- Licensure needs to be modernized. A national licensure framework agreement should be the goal. Several immediate changes must be made to ensure continuity of care and availability of the best culturally appropriate care.

- A new approach to clinical change management and medical education is needed to ensure that we keep the best of what we have learned and gather new data to further improve practice standards.

- Equity of access must be a priority. The phone has been a critical modality of care during the current crisis and should not be blocked. Digital literacy is clearly higher for the telephone. Technology infrastructure in many parts of the country continue to demand improvement to improve equitable access. This needs to be supported by expanded IT support and digital literacy

- User experience needs to be a priority for system development and adoption. This is true for both patients and clinicians. Good technology solutions have higher usage levels, good net promoter scores, and well-reported and widely comparable experience and outcome measures.

There is one more recommendation which came directly from reviewers and their comments over the past several weeks who noted how important the culture change of the past fifteen months has been. I will add this as Recommendation Zero.

Recommendation 0: Keep the culture change of the past fifteen months for as long as we can.

The "we can get it done" attitude that arose around the use of virtual care in the pandemic has been remarkable. Problems that had blocked progress for years evaporated. The public and private sectors collaborated and found new solutions. Stuff got done. There's a quote attributed to Harvard management guru Peter Drucker that I love: "Culture eats strategy for breakfast." The essence is that all the planning in the world doesn't make up for a "can-do" culture.

I recognize that some reversion to established behaviour patterns will happen. Both organized medicine and government are inherently conservative and slow to change. We should continue to ask questions and challenge the pre-2020 status quo. Let's keep the needs of patients and providers central to our technology choices and keep the best part of our new culture. Such a modern culture focused on user experience can be part of a revitalized commitment to Canada's public health care system.

My thanks to the two of you, to the over 100 people who gave their time for interviewees, to the members of the Expert Working Group and others who provided comments on earlier drafts, and to the team at Health Canada for their support during this project. During the course of this work, I have been supported by staff and clinicians at the Centre for Digital Health Evaluation; the project team of Michael Cheung, Leah Kelley, Karen Palmer, and Denise Zarn have made working on this project a lot of fun and they have each contributed majorly to its success. The errors and omissions are mine.

Sincerely,

Will Falk

East Garafraxa, ON

Figure 1 - Text Description

Six policy pillars, resting on three policy foundations.

- Six policy pillars

- Patient and Community Centered Approaches

- Equity in Access

- Provider Remuneration/ Incentive Structures

- Appropriateness, Safety, and Quality of care

- Provider Change Management

- Licensure

- Policy Foundations

- Privacy and Security

- Data Standards and Integration

- Technology (Procurement, Standards, and Operation)

Introduction

This “diagnostique” offers a summary of the state of virtual care in Canada as of May 2021. It relies on more than 100 key informant interviews, grey literature from the past 12 months, and the few relevant peer-reviewed scientific publications. We rely on the best available information at this time to summarize the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on virtual care across the country. Organized in four sections, we assess policy options within the Six Pillar Framework, and make recommendations to the provinces, territories, and federal government.

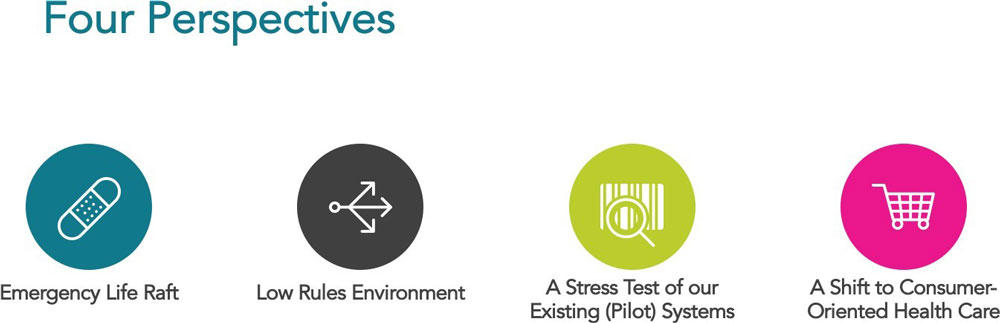

Section 1. What happened?: Four different perspectives presents four competing narratives on what happened with virtual care since February of 2020. Competing, because interviews demonstrated to us that our collective interpretation of what has taken place is still being debated. Clinicians, patients, and policy makers are struggling with the huge changes and forced modernization of our health care systems.

Section 2. Provincial/territorial, private sector, and international reviews recapitulates some of the key findings from our preliminary report (March 1, 2021) with a brief re-evaluation of jurisdictional and private sector responses to the changed environment. The full preliminary report slide deck (with updates) is available in the Appendices.

Section 3. Six policy pillars: options and recommendations discusses the six policy pillars and makes policy recommendations for each pillar. These recommendations range from higher level principles to practical, foundational items needed to advance implementation of virtual care.

Section 4. Recommendations, implementation issues and governance reiterates the recommendations and addresses several governance issues to attempt to set the framework for an agreed national implementation plan.

Section 1. What happened?: Four different perspectives

Figure 2 - Text Description

Four competing perspectives on what happened to virtual care in 2020:

- Emergency Life Raft

- Low Rules Environment

- A Stress Test of our Existing (Pilot) Systems

- A Shift to Consumer-Oriented Health Care

In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic upended Canada’s health care systems. The direct impact of the pandemic has been widely analyzed and will continue to evolve. This diagnostique covers the abrupt switch to virtual care that arose due to the high costs of physical contact (CoPC) between health care providers and patients. CoPC weights the benefits of care against the “cost of contact” from any physical interaction with the health care system.Footnote 1 The shift was dramatic and sharp. In just one month, virtual care went from 2-3% of ambulatory care visits to more than two-thirds.

This major shift in clinical practice can be viewed in several ways, with different observations and conclusions drawn depending on one’s viewpoint. This section describes four competing perspectives that emerged from over 80 key informant interviews—with patients, clinicians, system administrators, and policy makers—conducted between February and April of 2021. Each of these narratives has some truth to it and the intent of this section is to present them in a productive and engaging way that describes what has happened in the past 14 months to our health care system.

Perspective one: Emergency life raft

Many observers started Wave 1 with the perspective that virtual care was a temporary expedient. They viewed virtual care as an emergency measure necessary due to high CoPC. They presumed virtual care would stop as it had during earlier pandemics. Indeed, some provinces reinstituted the same billing codes used during earlier epidemics almost 20 years prior. These codes cover video, phone, and even some secure messaging. Virtual care usage was very high during Wave 1. Usage during the first quarter of 2020/21 across all ambulatory visits in Ontario was 77%.Footnote 2 In many provinces, we also saw a huge expansion of primary care call lines (e.g., 811, telehealth) and the rise of virtual Emergency Departments. The private sector also stepped in and offered expanded, and in some cases free, services (e.g., Dialogue).

But was this all temporary? Through the summer of 2020 we saw virtual care levels start dropping in Canada and elsewhere. The assumption was that levels would continue to decline back down to something more “normal”, as in closer to pre-pandemic. Even in the summer/pre Wave 2 fall, when virtual use plateaued around 40% at many centres (according to interviews and Infoway dataFootnote 3), this was still far above pre-pandemic levels despite more in-person care options. When Wave 2 hit, the rate of virtual care climbed back up. Anecdotally, it appears that sometime in late 2020, primary and specialty practices started making more permanent changes to their practice patterns.

For some visits, phone calls absolutely make sense for both the patient and the provider: they save the patient money and time, and the provider can see more patients in a day. All that was needed by the system was to enable this through appropriate reimbursement. IT and logistical systems failed, sometimes spectacularly (more on this later). New, better IT systems were introduced by several major vendors. Several provinces opened up codes to allow use of commercial video products such as Zoom and Teams. Volumes started growing and normalizing on the existing services that worked well. Wave 3 has hit at the time of this writing and it is becoming clear that more and more practices are now making adjustments to permanently include virtual care in their workflow.

Early academic reports are showing that many people like virtual care. Even when they have the choice of in-person care, some appear to prefer virtual.Footnote 4,Footnote 5 Providers are mixed as to exactly how to monitor and assure quality of care and appropriateness,Footnote 6,Footnote 7 but seem to mostly embrace virtual care. 81% of eVisits through Kaiser Permanente Northern California required no follow up care.Footnote 8 This speaks to the frequency of virtual care as a one-and-done modality, though it may also reflect self-selection by those who choose these modalities. We anticipate much more evaluation of these questions. Governments have also been watching the polling data provided by InfowayFootnote 5 and others. While some officials still may be looking at how to “roll back the fee codes”, this is becoming increasingly unlikely to be supported by Canadians.

Candidly, I was in this rollback camp a year ago. I said last summer to a Queen’s University MBA panel that I expected virtual care to stabilize somewhere around 20-40%. Like many others, I no longer believe this. Virtual care is no longer an adjunct therapy; it is now a core part of health care delivery.

Recommendation 1 Care is care. Virtual care should remain a publicly-funded service that can be used by clinicians when they, in consultation with their patients, judge it appropriate.

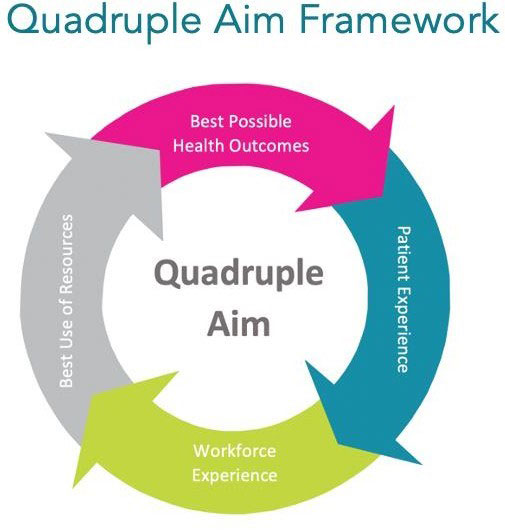

Recommendation 2: All care modalities need to be continually evaluated against the Quadruple Aim to ensure they are enhancing patient experience, improving population health, reducing cost, and improving the work life of health care providers (Bodenheimer and Sinsky, 2014) .Footnote 9

Perspective two: Low rules environment

This perspective views virtual care during COVID-19 as a great experiment in changing the rules. Rules that had existed, mis-applied standards, arbitrary payment, and historical practices were all subject to a fresh re-examination. A zero-based analysis interrogates every function within an organization for its needs and costs. We should now include high CoPC in such an analysis as an important variable for both providers and patients. For example, key informants spoke about privacy and security “practices” that were not supported by legislation or regulation. Rather, they had arisen through years of overly conservative interpretation, misidentification of whose rights are being protected, and even misunderstanding of laws and regulations. They also pointed to the risk averse approach of many health system actors to virtual care, resulting in a default to physical care services even when virtual care was known to be a good (sometimes better) option that promotes one or more aspects of the Quadruple Aim.

Figure 3 - Text Description

Quadruple Aim is an internationally recognized framework for an effective health system consisting of four parts:

- Best Possible Health Outcomes

- Patient Experience

- Workforce Experience

- Best Use of Resources

* Image from Women’s College Hospital: https://www.womenscollegehospital.ca/about-wch/accountability/performance-report-card/.

There is more than a hint from the people who hold this viewpoint that many of the rules were either: a) completely unnecessary; b) used by software vendors to protect market positions and to lock in their client base; c) used by service providers to protect outmoded and inefficient guild- based production models; d) used by government officials managing costs in a “penny-wise pound-foolish” fashion; and/or e) used by government agencies to further their own survival (i.e., budget allocation) in a model of regulation-controlled competition. There is some truth in these explanations. In some cases, that truth has been made painfully apparent during the pandemic.

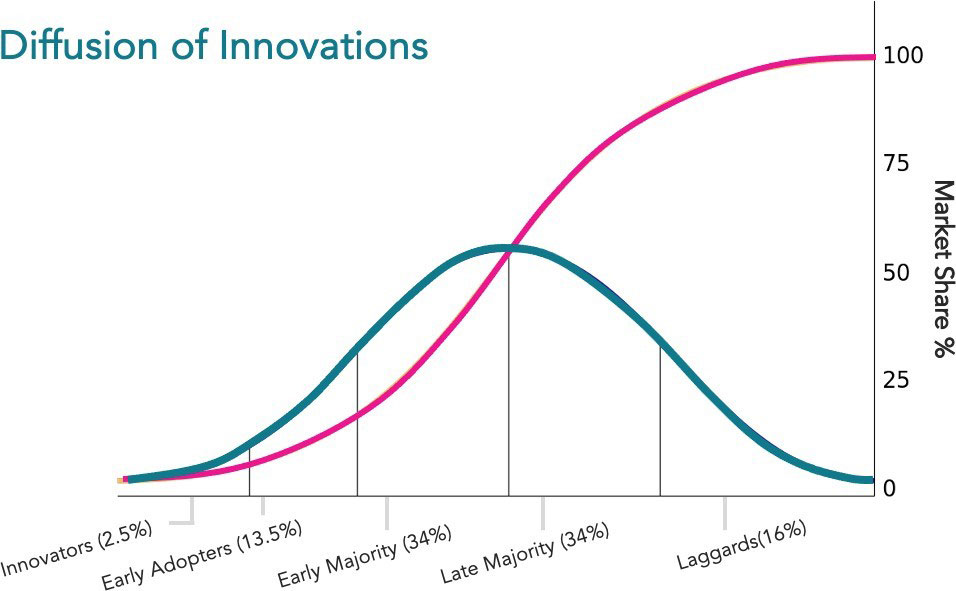

Experimentation with new modalities of care was forced in a manner that Christensen et al. refer to as “disruptive innovation”.Footnote 10 A new “measure of performance” was introduced into our health care system which resulted in a switch to a new “basis for competition”. Specifically, the risk of physical presence made it necessary to change how we deliver clinical care. This happened in the past year with the higher CoPC in many specialties and for most primary care.Footnote 1 As the pandemic progressed, more and more producers “retooled” to better serve their patients. This process was greatly hastened in some (but not all) specialties by very dramatic declines in providers’ incomes. Those who experimented with practical solutions that involved virtual care did better for the health of their patients and the health of their practices.

As we “return to normal” the question from a low-rules perspective is how much do we add back the old rules and the old reimbursement system?

Recommendation 3: A practical review of privacy and security interpretations and administrative rules should be undertaken in the context of the learnings from the past year. This should be a fresh evaluation specifically designed to reduce overly risk averse and impractical interpretations.

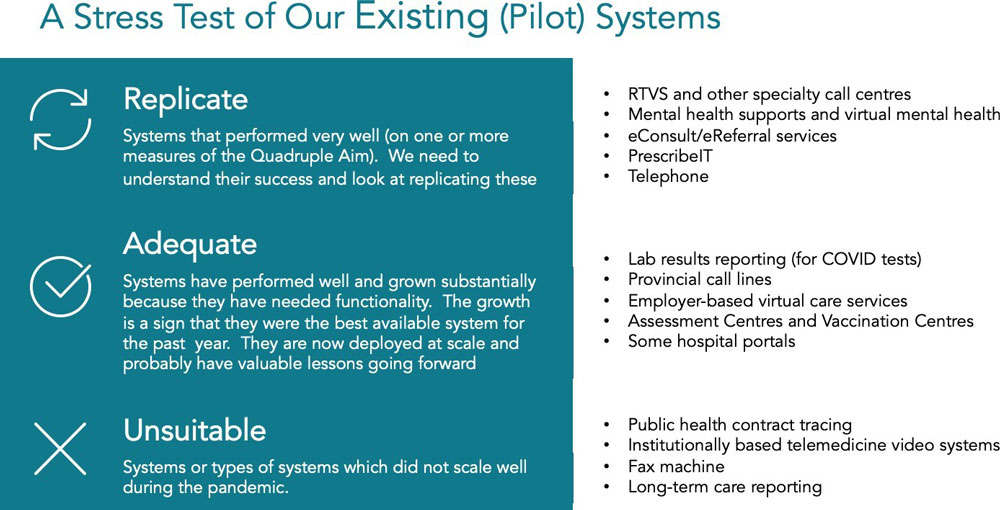

Perspective three: A stress test of our existing (pilot) systems

This perspective is a bit more critical of past decisions. It takes the perspective that for twenty years, and with the best of intentions, we have built telemedicine as an adjunct system. Several core beliefs informed our system architecture for virtual care and digital health systems. These included: a) a technical architecture borrowed from the banking industry in the 2000s; b) centralization of specifications and networks; c) virtual care being defined as video; d) reliance on the fax machine as a reserve technology; and e) the need to prove technology through pilots before deploying at scale rather than allowing choice among several systems. We have spent billions building digital technology to enable virtual health care systems. We usually did it through a central planning bureaucracy at the regional and provincial level.

The pandemic acted as a huge stress test of all the IT systems we had built. Some have performed well and have thus grown substantially to meet demand. They are now deployed at scale and probably offer valuable lessons going forward. There were many systems that did not scale well during the pandemic. Sometimes, they were set up inside of buildings at fixed locations which became less accessible and less safe due to CoPC during lockdowns (e.g., classic telemedicine). In other cases, they were just old or outdated technology, like fax machines or legacy software systems. The fax machine suffered from both, experiencing catastrophic failure for all or part of the pandemic. For example, our key informants estimate that 15% of faxes were failing on one major platform during a month in the middle of the pandemic. Some provinces had to resort to calling long-term care (LTC) homes for infection and death reports because the information systems seized up and were too slow to be useful.

It should surprise no one that some systems failed. Many of our information systems were the original systems funded over a decade ago by the PTs with help from Infoway. Often, they have only seen modest usage levels and have struggled to get appropriate upgrades to the technology. Upgrading systems is always difficult and requires a disciplined and organized approach. This has been complicated in the case of virtual care because of the huge advances in available technology while usage remained below 3%. When we jumped to virtual care representing the majority of visits, many of our IT systems failed to scale.

The intention here is not to embarrass agencies or vendors but each PT should assess how their own critical systems functioned over the past year.

Figure 4 - Text Description

Assess existing systems after the COVID stress test. IT systems fall into three categories - those that should be replicated, those that are adequate, and those that are unsuitable.

- Replicate: Systems that performed very well (on one or more measures of the Quadruple Aim). We need to understand their success and look at replicating these.

- RTVS and other specialty call centres

- Mental health supports and virtual mental health

- eConsult/eReferral services

- PrescribeIT

- Telephone

- Adequate: Systems have performed well and grown substantially because they have needed functionality. The growth is a sign that they were the best available system for the past year. They are now deployed at scale and probably have valuable lessons going forward.

- Lab results reporting (for COVID tests)

- Provincial call lines

- Employer-based virtual care services

- Assessment Centres and Vaccination Centres

- Some hospital portals

- Unsuitable: Systems or types of systems which did not scale well during the pandemic.

- Public health contract tracing

- Institutionally based telemedicine video systems

- Fax machine

- Long-term care reporting

In many cases these reviews have already been started and in some cases are near completion (e.g., Ontario and Nova Scotia). A distillation of learnings for each jurisdiction might include a letter grade for each major system based on existing publicly available measures.

This “stock taking” of IT system performance also presents an opportunity to create a baseline for Patient Reported Experience Measures (PREMS) and other usability and usage statistics for virtual care for the future. Infoway has already begun this process. Usage and usability need to be widely and transparently reported as virtual care becomes a routine part of services.

Our crisis response was appropriate. We freed clinicians to choose the best available tools and actively encouraged the use of more modern technology. They flocked to non-industry tools and to newly available private offerings. There was no structured change management. Centralized specification and slow purchasing were not possible. Decisions were fast-tracked and common sense was used as we abandoned some unscalable systems and started using others. Some physicians returned to their role as active buyers of technology and moved quickly to pick better systems for their practices. Many found this experience liberating and commented with some version of: “We have made more progress in the last ten months than the prior ten years”.

We need to hold on to this practical can-do attitude as we move forward. Too often, our large procurement processes have taken the clinician and patient out of the decision-making process and have not produced timely decisions. Those who hold this perspective believe that the pandemic forced usability, and patient/clinician experience into purchase and usage decisions.

In this regard the biggest surprise was the dominance of the humble telephone. Government-built video care systems (i.e., telemedicine) in many provinces did not perform well. Telemedicine systems were located in a few fixed clinics and hospitals, so providers and patients were required to travel to buildings equipped with the technology for consultations. High CoPC made these buildings hard to reach and the user experience (UX) was not as good. Many key informants pointed out that the telephone provided strong basic access for Canadians. This experience was reflected in the NHS, Australia, and many other nations.

“The default model, which involved, on average, $100 out-of-pocket costs to patients to attend physically, the CoPC, and office logistics on the clinician side never really made the most sense for some tasks. And frankly, video was also too cumbersome and didn’t make sense for those tasks which is why people weren’t using it despite a reimbursement model. This, to me, is proof positive that the barriers to some aspects of virtual came down to ONE thing…and one thing only…appropriate reimbursement for the phone.”

- Specialist Physician

Recommendation 4: Each PT should urgently conduct an objective inventory of IT systems and their pandemic performance. Develop replacements where appropriate. Each PT will have a development plan across existing and planned information systems.

Recommendation 5: There should be transparent reporting on usage levels and on user experience (UX) for all existing virtual care systems (probably for all digital systems). Patient and provider feedback should be readily available and transparent to all users.

Recommendation 6: PREMS for UX should incorporate non-health software measures (e.g., Net Promoter Score, Apps Store ratings) that are standard across all industries to allow comparability and to avoid the creation of health care-only services that are substandard.

Recommendation 7: Keep the telephone as a permissible modality under the virtual billing codes. The value of video over phone has been overinflated. Phone was foundational for equity and access.

Perspective four: A shift to consumer-oriented health care

Some observers see the pandemic as having unleashed consumer forces in health care. More modern virtual care technology has been a big winner in the pandemic. Those who view themselves as health care “consumers” or “clients” have demanded it. They switched, en masse, to good tech where it is available in the publicly-funded system and to privately-funded technology where it wasn’t.

Capital markets looked at the failure of government-sponsored virtual care technology and stepped up with billions of dollars of capital investments (Figure 5). Maple, Dialogue, Well, Babylon, Teladoc, PointClickCare, AlayaCare, ThinkReseach, and MindBeacon have now joined Loblaw and TELUS as major providers of virtual care services. We also have non-health care entrants at the table from multinationals like Zoom, Microsoft, and Amazon.

Figure 5 - Text Description

Virtual care companies’ market capitalization is approximately $10B, and is claimed by large, established companies and smaller growth companies. Some large companies include Well, Telus, PCC, Dialogue, Weston, and AlayaCare. Other companies include Maple, Teladoc Health, PointClickCare, Telus Health, Dialogue, MindBeacon, Orion Health, Well Health Technologies Corp, Babylon by Telus Health, and ThinkResearch.

Our governments moved very nimbly when they recognized this new reality, creating fee codes to let physicians bill provincial health insurance plans for virtual care while using these platforms. Their shared clients can now access better tech through public payment methods in many provinces. Existing, unusable, technology was abandoned quickly in the face of COVID- 19 and many jurisdictions (not all) allowed new entrants. Several governments just bought Zoom or Teams licenses for every clinician, to support them in caring for their own patients.

These new players are not the small start-ups that for the last two decades policy makers have been funding and encouraging to step up and innovate. In a very short period, our young digital health industry has matured to full blown adulthood. To use a folksy analogy, policy makers are both surprised and pleased with the child they have nurtured suddenly moving from being a teenager to having become a mature industry in a matter of months. As any parent of a 20-year- old knows, the process going forward will continue to have some tension!

Digital health in Canada is now a fully mature industry. This year alone we have seen eight companies go public on the TSX, VSE and even US exchanges. The largest of the Canadian players have market capitalizations that are larger than all but four of the provinces’ total budget spends. The total capitalization of the digital health market in Canada is now somewhere between $15 and $20 billion; this is approximately twice as much as all the money Infoway and the PTs have invested since 2001.

In some ways, this is a huge policy success. We should be justifiably proud of the mature industry that we have actively nurtured through smart policies and investments. Canadian governments, in a non-partisan way, decided to invest in health technology and today we have a huge native industry that is ready to take on the world. These are, in the politician’s words, “good clean knowledge economy jobs”. This market dynamic will, however, need to be managed and regulated going forward. The days of publicly subsidizing new system builds are largely over. The role of government has changed to one of managing competition among the myriad of virtual care platforms and providers. This becomes especially challenging given that the technology for many of these organizations is part and parcel with care delivery. The consequences of this new care model have yet to be fully understood.

There are more extreme versions of this perspective among the interviewees who would argue that policy makers need to get out of the way altogether and let the market decide. Or only step in when market failure is clear. We do not agree with this. Going forward, public policy needs to set the rules for competition in this immature market. Already evident are “rent-seeking behaviours” (excess charges for interfaces) and “walled gardens” that work well on their own but prevent access to information to those outside the walls. Appropriate market regulation can continue to not only support growth in this new industry but also ensure a strong public health care system that is true to the values of our country. At the same time, governments and health systems must honestly acknowledge that the technologies they built in-house were often inferior and unworkable.

Recommendation 8: Governments need to move from capability creation and subsidization to the management of a mature and competitive digital health industry. This recommendation is expanded in Section 4. Implementation Planning.

Figure 2: Four competing perspective on what happened to virtual care in 2020

Each of these four perspectives has some very good arguments to support it. Clinicians and policy makers across Canada are grappling with how to make sense of a very fast-paced year. New data have forced a re-evaluation of our worldview that is profound and deep. The one common element is echoed in the first recommendation: virtual care is no longer an adjunct therapy or an add-on to our workflow. Care is care: whether virtual or physical.

Note that although there is a section dedicated to equity and access, we must be clear that equity is a cross-cutting consideration integrated into every aspect of this report. Equity is central to health care policy in Canada. It is essential that every decision in virtual care policy be made in light of equity considerations. There must be ongoing monitoring to identify any unintended negative consequences on equity that may occur as a result of policy decisions for virtual care.

Recommendation 9: Develop feedback and monitoring processes to ensure policy decisions for virtual care promote equity and to identify any unintended inequitable consequences of virtual care development across Canada.

Section 2: Provincial/territorial, private sector, and international reviews

Interim reports were prepared as part of this diagnostique and presented to the FPT Expert Working Group and to PTs for validation and comment in March and April of 2021. These three interim analyses are summarized in the sections below.

Provincial/territorial reviews

COVID-19 forced rapid virtual care policy changes across provinces and territories. These changes came first and foremost in the form of billing codes. Prior to COVID-19, only British Columbia (BC) and Ontario (ON) allowed providers to bill for real-time video visits outside of designated telehealth sites. In the crisis of last year, governments responded nimbly and with a great deal of common sense.

During the course of interviews it became clear that real and exciting virtual care innovation is happening across the PTs. We have summarized some of that innovation in this section. We have also incorporated much of this innovation into the recommendations articulated throughout this report. We recognize that some PTs will be well ahead on some recommendations. To understand progress on each recommendation across the PTs, we have asked them to identify (before the June 2021 summit) which recommendations are underway in their PT, using Table 2 in Section 4.

Between March 13–March 27, 2020, all provinces and territories added temporary virtual care billing codes or temporary permissions to use in-person billing codes for virtual care.Footnote i There was a great deal of variety in the approaches taken. BC and ON expanded their codes (which already allowed for video visits) to allow for phone visits (voice only).Footnote ii Saskatchewan (SK) tied the video visit billing codes to use of a specific platform (Pexip) but is reviewing whether to make this permanent. Importantly, provinces typically did not differentiate the fee code between a video visit and a phone visit. All provinces, except Prince Edward Island (PEI), excluded asynchronous messaging (e.g., email, text) from the permissible modalities under which the virtual codes could be billed. ON allowed for some providers to bill for secure messaging, but only those who were part of the Ontario Telemedicine Network (OTN) Enhanced Access to Primary Care pilot program implemented in 2017.

Some provinces restricted their fee codes so that those who provided virtual-only walk-in clinics, rather than virtual walk-in visits as part of a “Bricks and Clicks” offering (i.e., both virtual and physical services), could not bill the system. Provinces with billing codes that could be used by providers working with these corporate platforms saw rapid proliferation in the number of companies offering these services (Figure 6 below). SK and New Brunswick (NB) introduced special billing codes for virtual walk-in visits, but at a lower rate than with patients’ regular providers (SK: $24.5 vs $35 and NB: $29 vs $47.50).

Figure 6 - Text Description

A depiction of Virtual Care Companies Whose Physicians Bill the Public System across Canada:

- British Columbia: CloudMD, Maple, Tia Health, Babylon by Telus Health, Viva Care, Walk in Virtual Clinics, Access Virtual

- Alberta: Maple, Babylon by Telus Health, Tia Health

- Saskatchewan: Babylon by Telus Health, Lumeca

- Manitoba: MobileMD, Tia Health, Sabe Wellness

- Ontario: Maple, Tia Health, CloudMD, Babylon by Telus Health, Tulip Health, Pulse On Call, Appletree Medical Group, Get Well Clinic, MyDoctor Now, The Doctor’s Office

None yet identified:

- Newfound and Labrador (Virtual appointments with NPs through 811)

- Nova Scotia

- Nunavut

- Quebec

- NWT

- Yukon

Many provinces saw increased demand and reliance on nurse helplines (e.g., Telehealth, 811 and 211 services) and mental health call lines. Anecdotal reports cite increases in call volumes between 600-700% in some provinces. Several provinces report hiring additional staff to increase capacity. In Nova Scotia (NS) and PEI, 811 became a central resource for coordinating COVID-19 testing and answering questions.

Some provinces purchased communication technologies through various non-industry-specific companies to improve access to existing services, while others purchased bundled virtual care platforms. For example, BC, NB, NS, Northwest Territories (NWT), and PEI all provided Zoom licenses to physicians. Nunavut (NT) and Manitoba (MB) used Microsoft Teams. Alberta entered into an agreement with TELUS to compensate physicians through an alternative relationship plan when they provide virtual services via the Babylon app. PEI and Alberta procured Maple to provide virtual care to their beneficiaries. This decision about whether to purchase à la carte communication technologies that can be used by existing clinicians versus a fully integrated platform is a tricky one – with benefits and disadvantages on both sides. With enough resources, it does not necessarily have to be one or the other. These two solutions can co-exist.

We have seen some creative uses of the virtual care platform in several provinces, where it has been used to augment monitoring of patients. Some creative steps were taken in billing. For example, MB included billing codes for virtual management of chronic disease patients. BC and SK invested in the TELUS Health Home Monitoring platform, which uses technology to remotely monitor patients’ health and then shares the information electronically with their health care teams. In SK, this service allows for home monitoring of certain post-surgical patients and recovering COVID patients. In BC, this was used to monitor COVID patients.

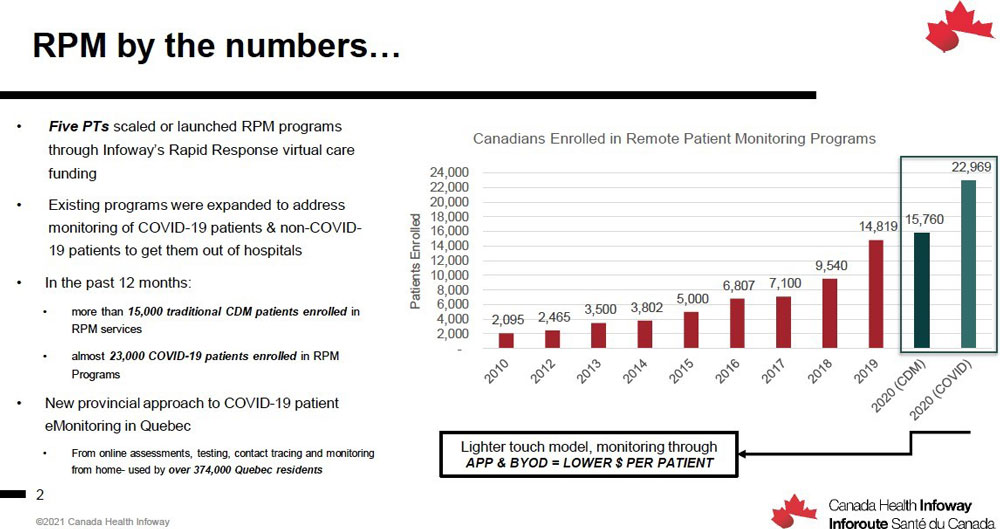

These innovations did not come in the early months from a desire to be innovative, but rather in response to the “Emergency Life Raft” approach to the pandemic. As the pandemic progressed, health care systems developed innovative approaches, at first to avoid admitting COVID patients when possible to limit use of hospital resources. As the pandemic continued, there was increasing concern that chronic disease patients were falling through the cracks. However, in- person care was still restricted, leading to expansion of these programs into non-COVID monitoring. This provided an opportunity to build on these emergency systems and make them permanent fixtures of a patient-centred health system (see section 3.2.4 on remote patient monitoring).

An area of particular focus for all provinces has been virtual mental health services. This was partly driven by expanded demand for support, reported widely by interviews. Many provincial governments directly invested in expansion of virtual mental health support services. These ranged from online forums (e.g., in AB, Togetherall), to self-directed CBT (e.g., in MB, AbilitiCBT), to resource centres (e.g., in NB, Newfoundland and Labrador (NL), and PEI, Bridge the gApp), to therapist-guided mental health services (e.g., in ON, MindBeacon). These investments have been mirrored by employer-based private supplemental insurance or as part of Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs), and through individually-purchased insurance plans.

BC and ON have worked on providing faster access virtually to certain specialty care. BC implemented the Real-Time Virtual Support (RTVS) program for residents and health care providers in rural, remote, and Indigenous communities. This program provides rural and remote primary care providers with 24/7 Zoom access to consultations with specialists in maternity, pediatric, emergency, and intensive care. The program is expanding to include rapid (not immediate) access to other specialists, such as dermatologists and rheumatologists. In ON, several hospitals have opened up Virtual Emergency Departments (EDs), allowing patients to call into virtual EDs and schedule time to talk with a provider, typically the same or next day. This was developed to address the concern that patients were not accessing the physical ED due to the high CoPC environment. Some of these programs existed prior to the pandemic and expanded greatly as need met opportunity.

There has been particularly impressive innovation in some Indigenous communities in virtual care. This is in part because they were already using virtual services and had relevant experience so could scale. Similarly, the territories and northern regions of some of the provinces were able to build on existing systems.

As described above, there have been dozens of innovations and many successes during the pandemic but ensuring equity in access has been a constant challenge across many communities. Virtual care allows some groups to gain access, but others are subject to poor IT infrastructure and other systemic disadvantages.

Review of private sector solutions for virtual care

The pandemic was a coming-of-age event for the digital health industry in general, and for virtual care in particular. There are currently over 40 private-sector digital solutions for virtual care in use in Canada, covering both physical and mental health, and expanding into labs and pharmacies. The combined market capitalization of the Canadian digital and virtual care industry is estimated to be approximately $15-20 billion. The industry has grown rapidly as these companies mature and innovate. In some respects this is a major policy success by the federal and provincial governments who invested in expanding this sector.

Of note, TELUS Health, the Weston Group, and WELL Health have made significant investments in virtual care through acquisitions and investment in virtual care technology solutions. TELUS Health acquired InputHealth Akira, EQ Care, and the Canadian operation of Babylon Health, adding them to its suite of digital health products. The Weston Group acquired QHR Technologies, the parent company of virtual care provider Medeo, and purchased a minority share of Maple. WELL Health made significant acquisitions, including Tia Health, Insig, and Adracare, with the goal of building a virtual ecosystem on its existing Virtual Clinic + platform. WELL is now also the largest integrator of services for Oscar EMRs; in essence creating a third major EMR vendor in Canada.

As growth in demand for virtual care services increased, revenues for these companies also increased significantly. In 2020, ten digital health companies were listed as publicly-traded companies. In December 2020, both MindBeacon (a virtual mental health provider) and Think Research (a company that developed a virtual care solution listed as an Ontario Telemedicine Network Vendor of Record) became publicly-traded. Dialogue Technologies, a virtual care provider used by large insurance companies such as Canada Life Assurance Company and Sun Life Financial, followed by going public in March 2021. This month, CloudDx listed on the Vancouver exchange, and Maple, a direct-to-consumer virtual care solution popular in ON, BC, NB, and PEI, announced in March 2021 that they are preparing to go public.

Figure 7 - Text Description

Virtual Care Acquisitions, Investments, & IPOs. Since late 2019, there has been significant activity within the Canadian virtual care industry as a few large, well- capitalized firms dominated the market, making moves to acquire and invest in many virtual care solutions

Pre 2020:

- Telus Health: Adracare, Akira, RH, Babylon*

- George Weston Limited: Medeo

2020:

- WELL Health: MedBASE, Indivica, DoctorCare, Insig, Tia Health, Li Ka Shing Investment

- Telus Health: eCare

- George Weston Limited, Maple*

- IPOs: Mind Beacon, Think Research

2021:

- Telus Health: Babylon

- IPOs: Dialogue, Cloud DX, Maple **

* Minority Share/ Partnership

** Expected

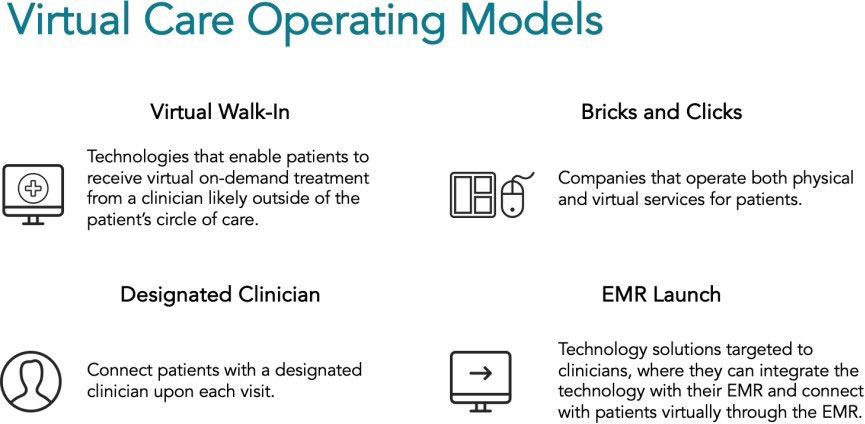

The models under which each of these platforms operate also varies across the virtual care landscape. In Figure 8, we have identified four main operating models for virtual care technology solutions: virtual walk-in, bricks and clicks, Electronic Medical Record (EMR) launch, and technology connecting patients to a designated clinician.

Figure 8 - Text Description

Privately-owned virtual care companies are adopting varied operating models. Four main operating models for virtual care technology solutions are identified: virtual walk-in, bricks and clicks, Electronic Medical Record (EMR) launch, and technology connecting patients to a designated clinician

- Virtual Walk-In: technologies that enable patients to receive virtual on-demand treatment from a clinician likely outside of the patient’s circle of care.

- Bricks and Clicks: companies that operate both physical and virtual services for patients.

- Designated Clinician: connect patients with a designated clinician upon each visit.

- EMR Launch: Technology solutions targeted to clinicians, where they can integrate the technology with their EMR and connect with patients virtually through the EMR.

Among the virtual care solutions currently available, there are few with pure unbundled technology that can be purchased and used as a separate piece of virtual care software. This may represent a gap in the current offering of virtual care solutions. It may also be that EMR launch solutions will dominate going forward, especially when offered in software as a service model. Virtual walk-in services have historically proven difficult to add into our public health care system and are subject to significant public protest by physicians and others. This is particularly interesting given that 811, telehealth, and nurse call lines are not subject to the same opposition. Designated clinician is currently mainly happening in mental health.

There has also been a dramatic shift in payers during the pandemic. As provinces relaxed reimbursement rules and created options for providers to bill provincial insurance plans, many platforms began to offer virtual care services funded by provincial and territorial health plans. Where there were coverage gaps, some patients chose to pay out-of-pocket to access (currently) uninsured solutions. In some provinces, provincial health systems purchased access to these bundled virtual care services from private companies, such as Babylon and Maple.

Employers stepped in during the pandemic and greatly expanded their coverage of virtual care providers through employee benefit plans. Several of these offerings were even provided for free during mid-2020 by virtual care providers seeking to expand market share. These offerings have now matured and have pricing models that are attractive enough for more employers to include them in employee benefits plans. Dialogue is one of the principal companies in this space and recently went public at a market capitalization of over a billion dollars -- making it the first virtual health “unicorn” in Canada. It almost certainly won’t be the last and WELL might dispute that it is the first.

Supplemental insurance companies also represented a major payer group. Dialogue partnered with major insurance providers including SSQ, IA Financial Group, Canada Life Assurance Company, and Sun Life Financial. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit Canada, Sun Life released its Lumino Health Virtual Care platform using the Dialogue Technologies solution, charging $3.49 per member per month. Other virtual care providers such as Akira, EQ Care, and Teladoc also partnered with major insurance providers in Canada. Millions of Canadians are now covered by such employer-based plans.

Some summary observations of this coming-of-age event:

- The Physician EMR market is dominated by three very large players: TELUS, George Weston Group, and WELL.

- Each of these players controls a sizable portion of the physician desktop business and has added virtual care to their EMRs.

- Each has acquired physician practices and is building “Bricks and Clicks” services as well as providing desktops (EMRs) to many other clinicians.

- Employer-based virtual care is available to many Canadians. Estimates for single products are over five million covered employees and their families.

- Mental health platforms are much more widely available because of the pandemic through both provincial reimbursement and employer coverage.

- Stand-alone virtual walk-in is increasingly being brought into the public sector. The private pay, direct-to-consumer market is a niche market in uncovered services, such as secure messaging and Nurse Practitioner video calls. It has grown temporarily.

- Many large practices are looking to build or partner to create their own bricks and clicks delivery systems. Some of these will come forward as “virtual first” offerings.

- Another half a dozen substantial but smaller players are trying to come into this market. These companies have market capitalizations between $100M and $1B. Several of these are now publicly-traded.

- Canada’s two leading vendors for older adult care are global champions. PointClickCare (PCC) in the long-term care and retirement home market and AlayaCare in the home care market have both redefined their sectors.

International experience

International experience with virtual care is broadly confirmatory of the Canadian experience during the pandemic:

- All countries for which we have data or reports from consultancies saw the same large and rapid expansion of virtual care due to high CoPC.

- This expansion varies by specialty. Mental health, endocrinology and several others have moved quickly to virtual while other specialties have struggled or gone back and forth.

- Incorporating virtual and physical care into one workflow is a key challenge everywhere, driven in part by reimbursement and regulation.

- Phone is the dominant modality. In the NHS England phone usage for virtual is even higher than in Canada. US payers have pushed for video and there is more video in the US as a result.

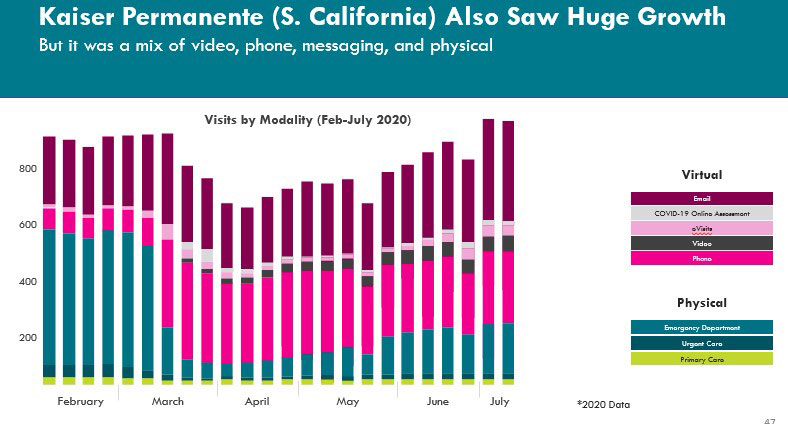

- Where secure messaging is allowed and compensated it is used for about one quarter of total volumes. Some of the best data on this are from Kaiser Permanente Northern California, shown below in Pillar 3.

- Equity, access, and infrastructure are tensions in virtual care globally, just as they are in in-person health care.

The next few years will see major reviews on how different health care systems have adapted during the pandemic and there will be important lessons in each of the six policy pillars.

Section 3: Virtual care policy for Canadians: Six pillars framework

This section is organized using the Six Pillars Framework developed by the Federal-Provincial- Territorial (FPT) Virtual Care Table in its deliberations during 2020/21. We have found this framework to be useful in organizing options and recommendations:

Figure 1- Six policy pillars, in which the recommendations in this diagnostique are grounded

One of the advantages of this framework is that it allows us to stay at the policy level when considering virtual care and not to get dragged into the details of the three policy foundations that underpin the pillars, namely:

- Privacy and Security

- Data Standards and Integration

- Technology

We offer some policy recommendations on these foundational elements but stay out of detailed arguments about data standards and specific technology choices. For example, we use the phrase “usable digital format” to describe data standards rather than getting into the details of FIHR, Blue Button, and other approaches. We stay away from any specific legislative or regulatory recommendations on privacy and security. We note, however, that many interviewees pointed out that existing rules has been conservatively interpreted prior to the pandemic. This changed with high CoPC. There will be a lot of work on these foundations by others in the coming years. We address some of the related policy issues in the framework of the Six Pillars but attempt to stay out of the details.

Pillar 1: Patient and community-centered approaches

Many patients love virtual care. As one provider said,

“Patients don’t want to come into the office. They are very resistant to that if it isn’t clinically necessary.”

- Rural Family Physician

Virtual care provides an opportunity to design a health system that is actually patient-centred. Our current system focuses itself on the needs of the provider, forcing patients to hop from building to building, bringing their records with them in the form of CDs, printed documents, or not at all. It is disconnected, inconvenient, time-consuming, and costly to patients. Virtual care has the potential to bring care to the patient, to improve care transitions, and to make engagement with the health system safer and more convenient for patients.

Designing virtual care for patients

Being patient-centred means that we put our clients at the centre of our system design discussions. One way to do this is to create archetypes or personas that represent the patients we serve and their needs. We have created six such personas. To ground this policy discussion, we invite you to consider each of them and their specific virtual care needs. Our experience, and a theme in our interviews, is that one size solutions fit no one. We must consider specific needs as we test new models and think about how to develop policy that better serves all Canadians.

- Aarya – medically complex older adult

- Aarya is an 84-year-old woman of South Asian descent who lives independently in a downtown retirement home on a fixed income. She has nine regular medications and seven specialists. English is her second language, and she relies on her daughter who supports much of her medical care.

- Casey – student attending university out-of-province

- Casey is an Albertan in first year university at Western University. They maintain their Alberta health coverage and driver’s license while completing their studies out-of-province. Casey has a sexual health problem that can be solved through antibiotic treatment but has had a previous negative reaction to an antibiotic. Casey accesses care either through an in-person or virtual walk-in clinic.

- Stevie – stressed adult with limited time to seek care

- Stevie is a 43-year old in downtown Montreal who has worked long days their entire career. They are 30 pounds overweight, diagnosed with high blood pressure, diabetes, and anxiety. The thought of leaving their busy job to see their doctor adds even more stress. Last week, Stevie’s partner recommended that they seek therapy for anxiety.

- Robin – rural farmer with poor IT connectivity

- Robin, a 54-year-old farmer, lives 300 kilometres north of Toronto in a rural region with poor technological infrastructure and lower than average per-capita income. On the farm, internet access is unreliable, and Robin goes hours at a time without internet. Rogers is the only available phone provider, so they are on a pre-paid voice-only phone plan with Rogers for which data is prohibitively expensive.

- Norman - Cree (Eeyou Istchee) hunter living in remote First Nation community

- Norman is a member of the Cree Nation on James Bay. He is a hunter who lives off the land for part of the year and receives some income support to do so. In the past Norman has been diligent about attending his follow-up appointments with the medical clinic that helps him manage his diabetes and high blood pressure when he is in town. But often these appointments conflict with his seasonal activities on the land. Sometimes he's out of reach by the time a call is made to schedule a follow-up, and as a result his medical care is interrupted for months at a time. Other times, he sacrifices precious time at his camp to make the day- long trek back to town for an appointment.

- Chris – youth with Crohn’s disease

- Chris is a healthy, active, kid living outside of a major city. Diagnosed with IBD about seven years ago. They and their parents have lived with the IBD schedule for years after stabilizing on a biologic treatment. Every six weeks Chris receives an infusion, originally at the downtown children’s centre and now locally. Every 3-4 months he goes for blood work and meetings with the nurse and doctor. One of his parents takes five hours off work for every visit and drives them downtown, an hour each way and $20 for parking. Chris’ dad says, “I do it because I am salaried and can do my work while taking care of my child. For my wife the income loss would be hard.”

There is no “average” patient with “typical” virtual care needs. These patient examples are distributed throughout the report (in Boxes 1-6) with added details about how their care changed during the pandemic. We need to “segment” these markets and develop a “consumer” approach for each of the different personas. We might see some overlap between their needs but we would never assume that there is one record or one service that would cover six such different people with such varying needs.

Let’s review the “virtual care” needs for each of these six persona in summary:

- Aarya: Circle of care support product which includes all providers and gives control of access rights to daughter and primary care provider; remote monitoring technology.

- Casey: Online pharmacy portal, access to lab results online, and virtual visits in-province for on-demand care or (preferably) out-of-province for access to health records.

- Stevie: e-referrals, e-Prescribing, and virtual visits via phone, video, or asynchronous modalities with family physician, as well as virtual mental health therapy from an app- supported service.

- Robin: Secure messaging and phone are the only modalities that will currently work for Robin, who would benefit from other virtual care tools including video visits and online access to their record. Local infrastructure at a pharmacy or library or next gen satellite technology will change this.

- Norman: Ability to access care while maintaining his culture and lifestyle. A mix of modalities that recognize infrastructure limits and seasonal barriers

- Chris: They and their family are an example of a specialty where both consumers and providers win from the shift to virtual care. Chris’ family gets the same high quality care and gains more than one hundred hours of time back and reduces costs. The health system gains capacity and does a better job of communicating and medical education.

Different people have very different virtual care needs. To be patient-centred means, in part, to consider the individual needs of the patient/consumer/client. In Canada, our notions of fairness in the public provision of health care services means that equal access is not always equitable.

Being fair and patient-centred means that at different times in our lives, we need different levels of service. More pithily: one size fits no one.

Means, medians, modes and modalities

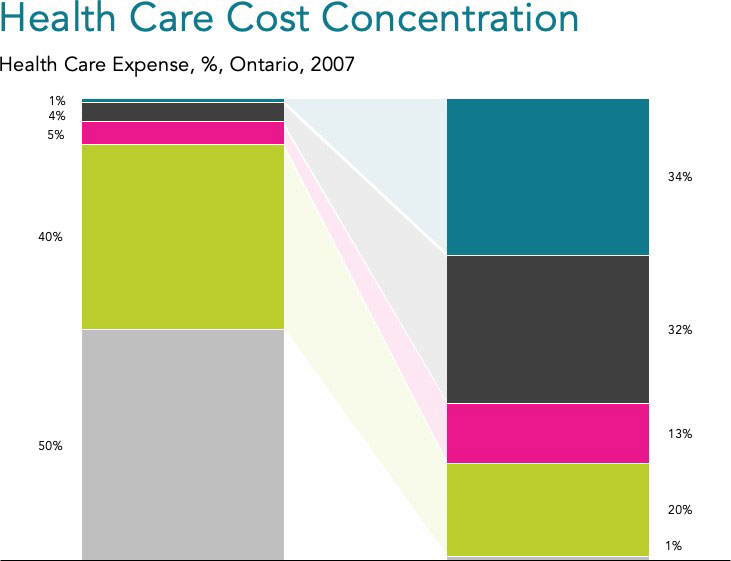

In their work on health care spending, Wodchis et al. demonstrated that “one size fits no one”.Footnote 11 In 2009-2011, the top 1% of Ontario’s users consumed 33% of public health care resources, spending at least $44,906 per person. Just 5% of the population accounted for 65% of all costs, with a starting threshold of $7,960 per person. Yet, 50% of the population had median annual costs of just $333 or less, accounting for only 2% of all allocated expenditures.Footnote 12 We cannot treat the person who costs the system $5000 in the same way as we treat the person who costs the system $50. The personas above make clear that these same patterns are likely to hold true in virtual care. The need for a full “circle of care” product, with distributed access to formal and informal caregivers, is likely a major concern for only a small portion of the population. Others will value continuity of recordkeeping to monitor an occasional flare up of a longstanding condition. The question of which modality is the most patient-centred has no clear answer. Some clients prefer secure messaging, but for others that is unworkable or undesirable. Some prefer video to phone in a high CoPC environment because they want the visual cues for communication and diagnosis, but for others the phone is satisfactory. And sometimes people need, or want, in-person care. And always will.

Figure 9 - Text Description

A graph showing that the concentration of healthcare spending is unevenly weighted a small portion of the population in Ontario from 2007. The top 1% of Ontario’s users used 34% of health care costs in Ontario. 4% of the top users used 32%, and the top 5% used 13% of the health care costs. 40% of the top users used 20%. The bottom 50% of the population used 1% of the health care expenses.

Determining which specific modalities are appropriate for which specific types of patient, consumer, or condition will be challenging. The clinical modality decision in April 2021 may be wrong in the near future. Technology is changing in some surprising ways. During interviews we stumbled upon a subset of physicians (in several provinces) who now use communications applications that allow them to switch between phone and video and secure messaging (e.g., WhatsApp and FaceTime). Last month, Zoom announced a telephone service, so we can reasonably predict that phone and video are not going to be separate modalities for much longer. This will solve some problems but will make reimbursement even trickier.

Determining which specific modalities are appropriate for which specific types of patient, consumer, or condition will be challenging. The clinical modality decision in April 2021 may be wrong in the near future. Technology is changing in some surprising ways. During interviews we stumbled upon a subset of physicians (in several provinces) who now use communications applications that allow them to switch between phone and video and secure messaging (e.g., WhatsApp and FaceTime). Last month, Zoom announced a telephone service, so we can reasonably predict that phone and video are not going to be separate modalities for much longer. This will solve some problems but will make reimbursement even trickier.

Rural Robin

Robin, a 54-year-old-farmer, lives 300 kilometres north of Toronto in a rural region with poor technological infrastructure and lower than average per-capita income. On the farm, internet access is unreliable, and Robin goes hours at a time without internet. Rogers is the only available phone provider, so they are on a pre-paid voice-only phone plan with Rogers for which date is prohibitively expensive.

Last month, Robin suffered a serious wound as they were operating heavy machinery. They asked their daughter to drive them to the closest hospital, two-hours away. After a physician treated Robin’s wound, they recommended that Robin monitor the wound with their GP and provided an online link to view the electronic records. However, when Robin tried accessing the record at the farm, bandwith was insufficient. Robin’s physician was another 45-minute drive away and referred Robin to a dermatologist in Toronto. The GP recommended that next time Robin set up a video visit, which was impossible due to the unreliable internet access.

There are many benefits of virtual care for Robin, cut with existing infrastructure and cost constraints. They are unable to access virtual care.

Future-proofing our virtual care decisions becomes even more difficult if we look out five years. Let’s consider three examples using our personas. In April, Microsoft spent $20Bn on Nuance speech technology. Imagine Aarya’s world if she could use speech recognition in Hindi. What would Robin’s care experience be if Elon Musk’s Low Earth Orbiting Satellites (LEOS) were in place and Robin could switch seamlessly from voice to video and back during the same visit? For Casey and all their college roommates, what they really want is to be using virtual reality for discussions with their family physician whom they have known since they were two.

Future-proofing patient-centred modalities is going to be tricky and we need to accept that the future is going to keep changing. We need to empower clinicians and patients to make these decisions and not set an overly high bar for the adoption of new approaches. A foundation for this is a universal data right for all patients.

Recommendation 10: Different patients will require different modalities and mixes of services for our system to be patient-centred and to support continuity of care. We need to be humble and flexible in our systems’ rules, regulations, and policies to allow innovation to continue apace.

Recommendation 11: Every person has the right to receive their health care data in a usable digital format by April 1, 2023. This should include a simple-to-administer ability to delegate control to a family member and to share information among a circle of care.

Improving both public health and patient-centred care through robust health information systems

Canada’s current health data infrastructure is still weak, threatening our communicable disease surveillance and response systems. The experience of the past year has confirmed that it is a matter of public safety that we do a better job on disease surveillance and infection control monitoring in our public health systems. A more robust data infrastructure will also improve our ability to provide excellent and well-organized virtual care to Canadians. We describe these five related recommendations next.

1. Lab Requisitions and Results

We must know who is at risk of COVID-19 infection and who is immune. Patients’ results have been digitally available for decades in Canada, but through imperfect mechanisms and often not accessible to the patient. Consumers now expect their test results to be available online for at least one important test: COVID-19. All tests should now be made digital.

Recommendation 12: All requisitions/results for standard lab tests should be sent/received in a usable digital format by April 1, 2023. No payment should be made for requisitions or results sent/received by paper.

2. E-Prescriptions

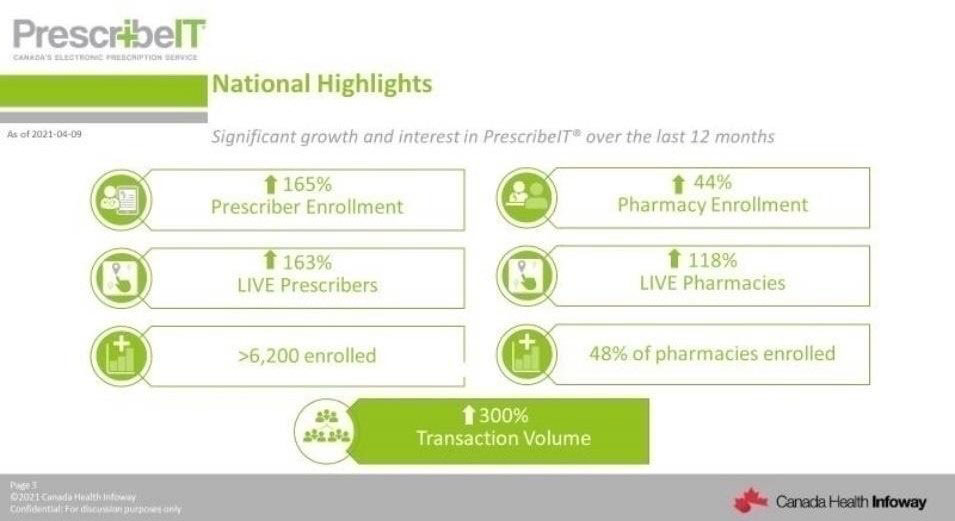

During the pandemic, PrescribeIT saw phenomenal growth, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10 - Text Description

Infoway’s PrescribeIT enables prescribers to electronically transmit a prescription directly from an electronic medical record to the pharmacy management system of a patient’s pharmacy of choice. PrescribeIT has seen significant growth and interest over the last 12 months. National highlights include:

- 165% increase in prescriber enrollment

- 163% in LIVE prescribers

- Over 62,000 enrolled

- 300% increase in transaction volume

- 44% increase in pharmacy enrollment

- 118% increase in LIVE pharmacies

- 48% of pharmacies enrolled

- 300% increase in Transaction Volume

There are a few competing commercial services to help keep this service competitive. This base of service allows us to make the following recommendation.

Recommendation 13: All prescriptions should be sent/received digitally by April 1, 2023. Because of the crisis in opioid usage in Canada, all opioid prescriptions should be sent/received digitally by April 1, 2022.

The added recommendation on opioid prescribing is long overdue and given the available services could occur immediately.

3. Home Care, Retirement Home and Long-Term Care records

Home Care: Canada now has a serious national champion in AlayaCare that allows caregivers to collect patient-reported outcome and experience measures – PROMS and PREMS. This software is built primarily as a logistics and scheduling platform and has a light health record that is focused on activities of daily living. This is of great interest to someone like Aarya’s daughter as she seeks to keep track of her parent’s health status. It is of occasional interest to others in her circle of care. AlayaCare has an automated PROM that assesses overall health status as well as several PREMs and reported experience measures for care providers, including personal support workers or health care aides.

Long-term care (LTC) is paradoxical in Canada from a digital perspective: we are both very sophisticated and woefully lacking in good virtual care and digital infrastructure in our LTC homes. Canada has the number one long-term care software system on the planet based in Mississauga. PointClickCare (PCC) employs 1300 people in North America and is worth about $5 Bn US. PCC is a huge Canadian success story and a national asset. Yet, there has been little discussion about using PCC as a reporting tool to assess quality of LTC homes and to track pandemic progress and vaccination. By current estimates, PCC already has more than 70% of the LTC market. They should be invited, among others, to co-design a standard reporting infrastructure. Note: this will require an aggressive translation program as PCC does not currently have an available French language version.

Recommendation 14: Pan-Canadian health care organizations should work with the two major Canadian eldercare software companies to redesign institutional and home care reporting systems.

4. Hospital sector

The large US IT vendors are struggling to provide similar functionality in ambulatory care under the weight of their monolithic inpatient IT systems. These systems are bound to US Medicare’s “Meaningful Use” standards. This drives their product development because they are the specific features of an electronic medical record (EMR) that providers must use to qualify for incentive payments. Some jurisdictions and/or their regions are doing well with their vendors to provide these services. Others are struggling. Frankly, the user experience for both patients and physicians is not uniform and often not good. Addressing this deficit will continue to be a problem for the next generation. But the US has introduced reporting standards that we, too, should insist upon in Canada for virtual care to be successful.

Recommendation 15: All hospitals should provide a discharge or encounter summary upon request in a usable, machine readable and searchable, digital format as of April 1, 2023. An appropriate small fee should be paid by government on behalf of requesting consumers.

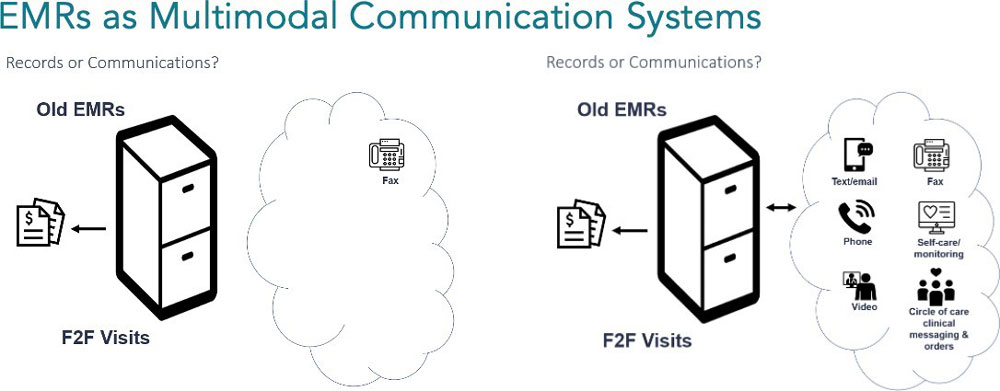

5. Physician EMRs

Primary care is an excellent place to collate patients’ records and to provide a communications hub for patients about their health care. They have increasingly evolved from being databases and billing systems to multimodal communications systems. Figure 11 shows a visualization of this change:

Figure 11 - Text Description

A graphic depicting how EMRs are evolving from databases and billing systems (e.g. fax machines) to multimodal communication systems (e.g. text/emails, phone, video, fax, self-care/monitoring, and circle of care clinical messaging & others).

Input Health (now owned by TELUS Health) and other innovative software developers have changed the game. Rather than building billing systems first, they started with communications and collection of validated information from patients. This patient-first, virtual care-first approach is being widely replicated in employer-based and on-demand virtual care. Some public health care systems are now also collecting automated data, as are the Ontario Virtual Care Clinic (OVCC) and 811/telehealth lines.

The next generation of primary care EMRs will start with the patient, build a history, and validate a set of symptoms. They will enable a virtual-first visit pattern. This will often start with some “Do-it-yourself” (DIY) assessment online and the sharing of resources by secure messaging. Virtual-first care will often proceed then with a simple phone call (or secure message if that is appropriately remunerated) that can be supplemented by pictures or switched to video during the same connection. Currently, there is a separation between phone and video, but we expect this to disappear in the next few years. Multimodal calls are already occurring regularly during the pandemic by some capitated primary care physicians. The barrier between portal, phone, messaging, and video is transitional only. Omnichannel systems will be the norm shortly. They already are for employer-based care systems that have exploded during the pandemic.

Before the pandemic we spoke about “building virtual into the workflow”. Today, virtual is the primary workflow for many practices and the need is to build a patient-centred multimodal experience. The EMR will not be the only system of innovation for patients.

Interviewed clinicians pointed to the need for better systems for patients in Wodchis’ et al.’s top ten percent of health system users. Some call this a “circle of care” product, others say “patient relationship management”, and some even hope that their own EMR may someday evolve into such a system. This information service may well be different for people whose health status indicates that they will be in a high user group for a number of years, so there are likely several types of products/ services needed depending on diagnosis and prognosis. A portal for pregnant patients is different than a circle of care product for an elderly cancer patient, and both are different again from platforms to support patients struggling with mental health and addictions. All need to be linked back to the system of record which will be usually held at the hospital or doctor’s office. Stevie and Aarya need information systems that are quite different even though they may both link back to the same base information stores in hospitals and physicians’ offices.

Occasional patients—most of us who rarely seek care— need a comprehensive data store to go back to as a “source of truth” (e.g., College Casey) but their active needs are usually more for communications technology or for a disease specific intervention (e.g., Stevie’s CBT platform, well-baby support).

Recommendation 16: All Primary Care EMRs should provide a summary upon request in a usable, machine readable and searchable, digital format as of April 1, 2023. An appropriate small fee will be paid by government on behalf of requesting consumers.

Some will say that these five recommendations are difficult or expensive. That view is penny wise and pound foolish. What is difficult and expensive is trying to manage health care during a pandemic without a strong digital backbone. We are ready to push full conversion of these and other foundational services and should do so immediately. There may be some remediation support needed to help transition gracefully and to ease genuinely sub-scale situations.

Recommendation 17: A temporary paper record remediation service should be made available to service providers (at their expense) to allow them to meet patient information requests during FY 2022 to 2026 to ease transition to a fully digital world.

The question of portals for patients

If we were starting with a blank sheet of paper, we would probably use the PCP’s EMR as the basis for all patient information needs and queries. But we are not doing so. Current consumer access to information in Canada has relied on 20th century portal technology first developed in other countries. At last count, there were more than 90 portals in Ontario alone. Many hospitals have implemented these patient portals with mixed success during the pandemic. Separate personal records also exist in many of the health care segments listed above, including lab systems and pharmacies. LTC and home care provide patient summaries to family members. We have provincial immunization systems with portal like “yellow cards” that will be more important after the last year.

Broader enrollment and use of such personal health record services should be encouraged to create an information rich system. These payments will also serve to reward players who have already started addressing this need and to encourage others to do so. The “push” recommendations above will create costs; our policy in this area should create a “pull”. A small payment of about 25 cents per active user each month ($3 per year) should be paid to each provider who has an active consumer portal. Active management of these systems will be needed in coming years. Major systems exist in pharmacy, labs, and hospitals. They exist and should be more common in primary care. Having such systems in place is a key part of bringing virtual care into the workflow of all system providers.

Ambulatory Aarya

Aarya is an 84-year-old South Asian woman who lives independently in a downtown retirement home on a fixed income. She has nine regular medications and seven specialists. English is her second language, and she relies on her daughter who supports much of her medical care.

- Cardiologist calls to review blood pressure (which is taken by the LPN)

- Endocrinologist calls and emails with daughter to discuss routine bloodwork

- Regular macular degeneration appointments have been suspended and sight is deteriorating

- Daily dermatology treatments have continued at the home by a PPE clad RPN

Virtual visits for Aarya cannot be done over video because of her poor eyesight. Secure messaging (email) is with her daughter, and breaks privacy rules. Written communication in English relies heavily on the daughter’s support. Three-way calls with the provider and the daughter on the line have been essential for ensuring information is received by both Aarya and her daughter. E-labs and e-prescriptions would help Aarya’s daughter keep track of all relevant medical updates. The daughter needs a circle of care record.

Recommendation 18: A small monthly fee (25 cents) should be paid each month to providers as an information fee for providing a personal health record service (aka portal) that is being actively used by consumers. This fee should have a sunset period of five years as it becomes a normal part of the workflow of the health service providers (declining by 5 cents per month each year).

Recommendation 19: All government supported PHR services and portals must publicly report monthly active users, Net Promoter Score and such other PREMS as may be directed by the Pan-Canadian Health Organizations in order to receive payment.

There would be no need for a central government portal if there existed a working standards architecture and an Application Programming Interface (API) system that allows applications to talk to each other. APIs are ubiquitous in our everyday lives. Each time we pay for something with PayPal in an eCommerce store, we are using an API. When we use travel booking sites, it’s an API that aggregates thousands of flights and destinations to showcase the cheapest option.