ARCHIVED – Evaluation of the Immigration to Official Language Minority Communities (OLMC) Initiative

Research and Evaluation Branch

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

July 2017

Technical Appendices are available upon request to Research-Recherche@cic.gc.ca.

Ci4-170/2017E-PDF

978-0-660-09308-6

Reference Number: E3-2015

Download:

Table of contents

- List of acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Evaluation of the Immigration to OLMC Initiative - Management Response Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Methodology

- 3. Key Findings: Relevance

- 4. Key Findings: Performance – Promotion and Recruitment of French-speaking Immigrants in FMCs

- 4.1 Immigration of French-Speaking Immigrants

- 4.2 Interprovincial Mobility among French-Speaking Immigrants

- 4.3 Targets for Francophone Immigration

- 4.4 Awareness of Employment-Related Stakeholders

- 4.5 Awareness of French-speaking Foreign Nationals and Importance of Employment

- 4.6 Dissemination of Information and Contribution to Decision-Making

- 4.7 Considering the Possibility of Living and Working Outside of Quebec

- 5. Key Findings: Performance – Settlement and Integration of French-Speaking Newcomers in FMCs

- 5.1 Using Canada’s Official Languages

- 5.2 Economic Integration

- 5.3 Social Integration

- 5.4 Overall Integration, Knowledge and Decision-Making

- 5.5 Use of IRCC-Funded Settlement Services by French-speaking Clients

- 5.6 Meeting the Settlement Needs of French-speaking Clients

- 5.7 Contribution of the Réseaux en immigration francophone

- 6. Key Findings: Performance – Coordination and Consultation with Key Stakeholders

- 7. Key Findings: Performance – Strategic Data Development, Research and Knowledge-Sharing

- 8. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A: List of Supporting Appendices in the Technical Appendices

List of tables and figures

- Table 1: Number and Relative Percentage of French-Speaking Immigrants Destined to Provinces or Territories outside of Quebec (2003 to 2016) – Overall and Economic Immigrants Only

- Table 2: Interprovincial Mobility among French-Speaking Principal Applicants (PAs) Admitted to Canada between 2003 and 2014 – Net Change (%) between Province/Territory of Intended Destination and Province/Territory of Residence in 2014

- Table 3: Application and Attendance Results for Destination Canada – 2012 to 2016

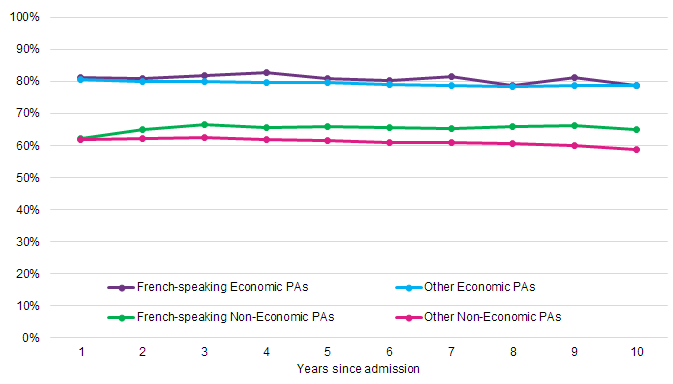

- Figure 1: Incidence of Employment for French-speaking Principal Applicants (2003 to 2014) Compared to Other Principal Applicants by Number of Years since Admission to Canada and Immigration Category (Economic versus Non-Economic)

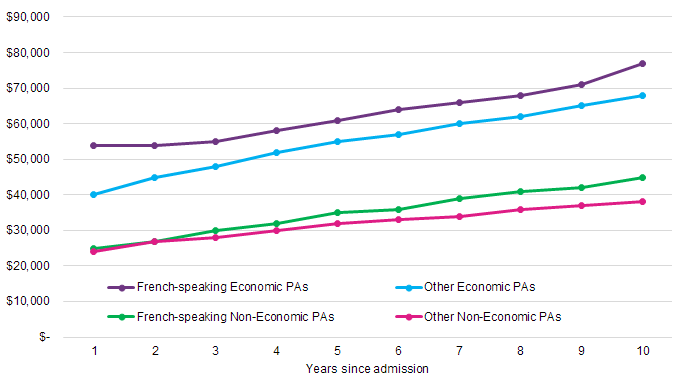

- Figure 2: Average Employment Earnings for French-speaking Principal Applicants (2003 to 2014) Compared to Other Principal Applicants by Number of Years since Admission to Canada and Immigration Category (Economic versus Non-Economic)

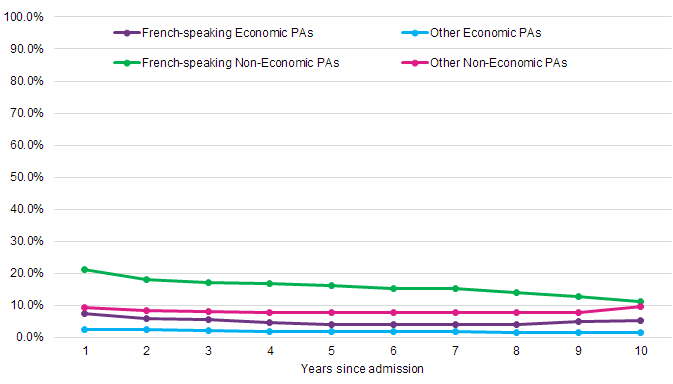

- Figure 3: Rate of Social Assistance Use for French-speaking Principal Applicants (2003 to 2014) Compared to Other Principal Applicants by Number of Years since Admission to Canada and Immigration Category (Economic versus Non-Economic)

- Table 4: Percentage of French-speaking Newcomers Surveyed Compared to All Newcomers Surveyed with at Least Some Knowledge of Life in Canada by Topic

- Table 5: Use of IRCC-Funded Settlement Services by French-speaking Clients Compared to Other Clients Admitted to Canada as Permanent Residents (2014 to 2015)

- Table 6: Resource Distribution and Funding Allocations for the OLMC Initiative under the Roadmap 2013-2018: Fiscal Years 2013-2014 to 2017-2018

- Table 7: Funding related to the OLMC Initiative under the Settlement Program: Fiscal Years 2013-2014 to 2016-2017

Acronyms

- APPR

- Annual Project Performance Report

- APRCP

- Annual Performance Report for Community Partnerships

- CA

- Contribution Agreement

- ELN

- Employer Liaison Network

- ESCQ

- English-Speaking Communities in Quebec

- FCFA

- Fédération des communautés francophones et acadienne

- FMC

- Francophone Minority Community

- GCMS

- Global Case Management System

- iCARE

- Immigration Contribution Agreement Reporting Environment

- GCS

- Grants and Contributions System

- GoC

- Government of Canada

- IMDB

- Longitudinal Immigration Database

- IRCC

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- IRPA

- Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

- LIP

- Local Immigration Partnership

- NHQ

- National Headquarters

- OGD

- Other Government Department

- OLA

- Official Languages Act

- OLMC

- Official Language Minority Community

- OLS

- Official Languages Secretariat

- PCH

- Department of Canadian Heritage

- PA

- Principal Applicant

- PR

- Permanent Resident

- RDÉE

- Réseaux de développement économique et d’employabilité

- RIF

- Réseaux en immigration francophone

- SA

- Social Assistance

- SCOS

- Settlement Client Outcomes Survey

- SPO

- Service Provider Organization

- TR

- Temporary Resident

Executive summary

Purpose of the Evaluation:

This report presents the findings of the evaluation of Immigration, Refugee and Citizenship Canada’s (IRCC) Immigration to Official Language Minority Communities Initiative (hereafter the OLMC Initiative). The evaluation examined relevance and performance, and was conducted in fulfillment of requirements under the Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation and section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act. Findings also contributed to the Department of Canadian Heritage’s (PCH) horizontal evaluation of the Roadmap for Canada’s Official Languages 2013-2018: Education, Immigration, Communities (hereafter the Roadmap 2013-2018).

Overview of the OLMC Initiative:

The OLMC Initiative derives its mandate to support and enhance the development and vitality of OLMCs from the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) and the Official Languages Act (OLA), and includes various activities within IRCC to foster the promotion, recruitment and integration of French-speaking immigrants to FMCs outside of Quebec, as well as to further knowledge development and sharing in relation to both FMCs and ESCQ. Allocated $29.4M in funding over five years (and $4.5M ongoing), the Initiative is a key commitment under the Immigration pillar of the Roadmap 2013-2018, and is broadly organized into four components:

- Promotion and recruitment activities in Canada and abroad, including Destination Canada;

- Settlement services to French-speaking clients;

- Coordination and consultation with key stakeholders; and

- Strategic data development, research, and knowledge sharing projects for immigration to both FMCs outside of Quebec and English Speaking Communities in Quebec (ESCQ).

Summary of Conclusions and Recommendations:

Management and Governance: Overall, the evaluation found that the OLMC Initiative involves numerous activities, embedded in IRCC’s immigration and settlement programming, which are not always well aligned and can be overlapping. Management, delivery and accountabilities for these activities are spread across different responsibility areas within the department, with no clear policy lead for the Initiative as a whole. While mechanisms to govern and coordinate the OLMC Initiative are in place, and have improved since the 2012 evaluation, the Initiative still lacks a unified strategy, with focused leadership and overall accountability.

Recommendation 1: IRCC should review and revise the governance and accountability framework supporting the OLMC Initiative. The review should consider roles and responsibilities within IRCC, as well as leadership, and identify a clear policy lead within the department with overall management responsibility and accountability for the Initiative as a whole.

Promotion and Recruitment of French-speaking Immigrants in FMCs: The OLMC Initiative has had some success in raising awareness among French-speaking foreign nationals about the opportunities to live and work in Canada, as well as among employers in Canada about the opportunities and mechanisms to recruit and hire French-speaking immigrants. However, in spite of these efforts, which have been ongoing since 2003, the relative weight of French-speaking immigrants settling in FMCs remains well below departmental targets. Evidence indicates that the current approach, which has relied mainly on promotional activities as well as options for temporary residence, may not be sufficient to achieve the established targets, and more efforts may be needed if current targets are to be realized.

Settlement and Integration of French-Speaking Newcomers in FMCs: French-speaking newcomers are generally integrating economically at rates that are comparable to other immigrants. They are using both of Canada’s official languages in their daily lives, and English language ability is associated with their economic and social integration. There is also an indication that French-speaking newcomers have knowledge about life in Canada and are participating in Canadian society. IRCC supports the integration of French-speaking newcomers in FMCs through its Settlement Program. The goal is for French-speaking newcomers to adopt a “Francophone integration pathway”, and IRCC is committed to supporting a “for and by Francophones” approach. However, this approach is not yet well-defined, and the role of non-Francophone organizations to support this work is unclear. Moreover, the lack of supports for temporary residents targeted by the OLMC Initiative, to help them form meaningful links to the Francophone community, is also a challenge.

Partner and Stakeholder Engagement: Considerable effort has gone into engaging partners and stakeholders in Canada and abroad in the activities of the OLMC Initiative. However, the level of engagement of certain partners, such as provincial/territorial governments, who have responsibility for the infrastructure and services required to maintain the vitality of FMCs to attract and retain French-speaking immigrants, has been a challenge.

Recommendation 2: IRCC should develop and implement a unified and horizontal strategy for the OLMC Initiative which should:

- Review and revise activities in relation to Francophone immigration to more effectively support the achievement of established targets. Activities should include promotion, as well as tools and mechanisms to facilitate permanent residence and retention.

- Advance the “for and by Francophones” approach for the department.

- Develop an approach to support the temporary residents targeted by the Initiative in developing links with the FMCs.

- Better leverage governmental, non-governmental and employment-related partners in support of FMCs’ capacity for attraction, integration and retention of French-speaking newcomers.

Strategic Research, Data Development and Knowledge-Sharing: The OLMC Initiative has facilitated the development of knowledge and the creation of awareness of topics related to immigration to OLMCs, particularly within IRCC. However, ensuring the use of research results to inform policy development and addressing the knowledge needs and priorities of the diverse stakeholders has been a challenge. Progress has been made in terms of performance measurement since the 2012 evaluation. However, as the Initiative continues to evolve, the performance measurement strategy needs to be updated to effectively monitor the activities, outputs and expected outcomes of the Initiative.

Recommendation 3: IRCC should update the performance measurement strategy for the OLMC Initiative to be aligned with the horizontal strategy, as per Recommendation 2, and to address results monitoring and reporting challenges.

Evaluation of the Immigration to OLMC Initiative - Management Response Action Plan

Recommendation #1

IRCC should review and revise the governance and accountability framework supporting the OLMC Initiative. The review should address roles and responsibilities within IRCC, as well as leadership, and identify a clear policy lead within the department, with overall management responsibility and accountability for the Initiative as a whole.

Response #1

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

The Department acknowledges that having one central policy lead responsible for all francophone immigration issues would ensure a more systemic inclusion of a Francophone lens in immigration programs and policies as well as consistency in policy, engagement with stakeholders and accountability.

IRCC is reviewing its internal OLMC governance mechanisms.

The mandate of IRCC’s Official Languages Steering Committee is being reviewed and updated in order to:

- increase program accountability particularly with respect to IRCC obligations under Part VII of the OLA and under 3(1) b.1 of IRPA;

- foster awareness and commitment of senior management on emerging issues related to francophone immigration; and

- formally include the committee’s role and mandate with the Department’s governance structure.

Action #1.1

Identify a clear policy led accountable for the OLMC Initiative.

Accountability: ADM Strategic Program and Policy (SPP). Completion Date: June 2017.

Action #1.2

Develop an Accountability Framework that clearly identifies roles and responsibilities within the Department for the OLMC Initiative.

Accountability: ADM SPP. Completion Date: September 2017.

Action #1.3

Update the terms of reference for the Official Languages Steering Committee.

Accountability: Official Languages Secretariat (OLS). Support: ADM SPP, International Network (IN), Settlement Network (SN), Human Resources Branch (HRB). Completion Date: September 2017.

Recommendation #2

IRCC should develop and implement a unified and horizontal OLMC Initiative Strategy which should:

- Review and revise activities in relation to Francophone immigration to more effectively support the achievement of established targets. Activities should include promotion, as well as tools and mechanisms to facilitate permanent residence and retention.

- Advance the “for and by Francophones” approach for the department.

- Develop an approach to support the temporary residents targeted by the Initiative in developing links with the FMCs.

- Better leverage governmental, non-governmental and employment-related partners in support of FMCs' capacity for attraction, integration and retention of French-speaking newcomers.

Response #2

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

IRCC is committed to working on policies and strategies to increase the number of francophone immigrants successfully settling in official language minority communities and is closely collaborating with Canadian Heritage in the development of the Government of Canada’s Action Plan for Official Languages 2018-2023 (to take effect April 1, 2018). IRCC’s contribution to the Action Plan will form part of IRCC OLMC Strategy.

New initiatives will also take into consideration recent reforms (e.g. new measure/definition of French-speaking immigrant, introduction of Mobilité francophone, changes to Express Entry, increased promotional efforts), and will continuously be reassessed, to further inform innovation and improvements throughout the entire immigration continuum.

IRCC is making use of technology as an important means of reaching French-speaking immigrants in Canada and abroad. Examples of projects funded by IRCC include online language training (Cours de langue pour immigrants au Canada, CLIC en ligne) and online pre-arrival services.

The Department is discussing with the Provinces, territories, communities and other government departments issues regarding Francophone immigration and its role in maintaining and enhancing the vitality of Francophone minority communities.

IRCC is also working with provinces/territories, service providers, stakeholder organizations and other government departments to improve settlement services for French-speaking immigrants and refugees and their connection to Francophone Minority Communities.

Action #2.1

The Department will develop and implement an OLMC Strategy to address the recommendation.

Accountability: Settlement and Integration Policy Branch (SIP). Support: IB, IIR, IN, SPP, OLS, SN, R&E, Communications, Finance.

- Presentation of a proposed Strategy to the OL Steering Committee. Completion Date: December 2017.

- Implement the Strategy. Completion Date: April 1, 2018.

Action #2.2

Implement a new service (Arrimages francophone) to facilitate the creation of ties between Francophone immigrants and the local and regional Francophone community and report on results.

Accountability: SN. Support: SIP.

- 1st year Implementation. Completion Date: 2017-2018.

- 2nd year Stocktake. Completion Date: September 2018.

Action #2.3

Report on results of completed IRCC-funded projects.

Accountability: SIP. Support: SN.

- 1st year Implementation. Completion Date: 2017-2018.

- 2nd year Stocktake. Completion Date: September 2018.

Action #2.4

Review of projects and engagement with stakeholders; review results to inform future Calls for Proposals.

Accountability: SIP.

- Pre-arrival. Completion Date: March 31, 2018.

- For National CFP. Completion Date: March 31, 2020.

Action #2.5

Revise and update the terms of reference of the IRCC/FMC committee.

Accountability: OLS. Support: SN. Completion Date: December 2017.

Action #2.6

Work with provinces and territories, as well as Francophone Minority Communities, to organize a federal-provincial-territorial and community symposium to lay the foundation for new collaboration.

Accountability: SIP. Support: IIR, IB, SPP, IN, OLS, SN, R&E, Communications. Completion Date: March 31, 2018.

Recommendation #3

IRCC should update the performance measurement strategy for the OLMC Initiative to be aligned with the horizontal strategy, as per Recommendation 2, and to address results monitoring and reporting needs of the Department.

Response #3

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

In the context of the development of the Action Plan for Official Languages 2018-2023, a new Performance Information Profile will be developed to allow more robust monitoring and reporting. It will also include relevant departmental activities that extend beyond OL action plans commitments.

Action #3.1

Develop an annual “Accomplishments” report relating to the Department’s official languages.

Accountability: OLS. Completion Date: December 2017.

Action #3.2

Develop a new Performance Information Profile (PIP).

Accountability: OLS. Support: Research & Evaluation, SIP. Completion Date: April 2018.

Action #3.3

Complete a Stocktake report based on the PIP.

Accountability: OLS. Support: Research & Evaluation, SIP. Completion Date: September 2018.

1. Introduction

1.1 Purpose of the Evaluation

This report presents the findings of the evaluation of Immigration, Refugee and Citizenship Canada’s (IRCC) Immigration to Official Language Minority Communities Initiative (hereafter the OLMC Initiative). The evaluation examined relevance and performance, and was conducted in fulfillment of requirements under the Treasury Board Policy on EvaluationFootnote 1 and section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act.

Findings from the evaluation of the OLMC Initiative also contributed to the Department of Canadian Heritage’s (PCH) horizontal evaluation of the Roadmap for Canada’s Official Languages 2013-2018: Education, Immigration, Communities (hereafter the Roadmap 2013-2018), through which IRCC received funding for the OLMC Initiative, and will inform the work moving forward with the new Multi-year action plan for official languages.

1.2 Overview of the OLMC Initiative

1.2.1 Policy Context

The OLMC Initiative derives its mandate to support and enhance the development and vitality of Official Language Minority Communities (OLMCs) from the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) and the Official Languages Act (OLA).Footnote 2 It is also part of IRCC’s commitment as a federal partner in the Government of Canada’s (GoC) various strategies to foster the development and vitality of OLMCs. This commitment was first reflected in the Action Plan for Official Languages (2003), and subsequently renewed in the Roadmap for Canada’s Linguistic Duality 2008-2013: Acting for the Future (2008), and now the Roadmap 2013-2018 (2013).

The GoC is committed to supporting both Francophone Minority Communities (FMCs) outside of Quebec and English-Speaking Communities in Quebec (ESCQ). However, the federal government has a limited role in Quebec in the context of immigration due to the Canada-Québec Accord relating to Immigration and Temporary Admission of Aliens (hereafter the Canada-Québec Accord) which gives responsibility to the province of Quebec for the selection and integration of immigrants in this province.Footnote 3

Given this limited role, IRCC has focused its activities to support OLMCs throughout the years on Francophone immigration and integration in FMCs outside of Quebec, and has set out specific objectives and priorities for this work. These objectives and priorities were first articulated in IRCC’s Strategic Framework to Foster Immigration to Francophone Minority Communities (2003), and later in its Strategic Plan to Foster Immigration to Francophone Minority Communities (2006) (hereafter the Strategic Framework and the Strategic Plan).Footnote 4

1.2.2 Description of the OLMC Initiative and the Roadmap 2013-2018

IRCC’s OLMC Initiative is a key commitment under the Immigration pillar of the Roadmap 2013-2018.Footnote 5 Led by the Department of Canadian Heritage (PCH), the Roadmap 2013-2018 is a continuation of efforts from the preceding Roadmap 2008-2013, reflecting commitments that stem from Part VII of the OLA, and representing a renewed investment of $1.1 billion over five years. It includes 28 initiatives, implemented by 14 federal partners, grouped according to three broad priority areas for action (or pillars): education, immigration and community support. The strategic outcome for the Roadmap 2013-2018 is to create conditions in which Canadians can live and thrive in both official languages, and recognize the importance of English and French to Canada’s national identity, development and prosperity.

IRCC’s OLMC Initiative was allocated $29.4MFootnote 6 in funding over five years, as well as $4.5M in ongoing funding, under the Roadmap 2013-2018 to foster the promotion, recruitment and integration of French-speaking immigrants to FMCs outside of Quebec, as well as to further knowledge development and sharing in relation to both FMCs and ESCQ.Footnote 7 It is broadly organized into four components:

- Promotion and recruitment activities in Canada and abroad, including the Destination Canada Job Fair;

- Settlement services to French-speaking clients;

- Coordination and consultation with key stakeholders; and

- Strategic data development, research, and knowledge sharing projects for immigration to both FMCs outside of Quebec and ESCQ.

The OLMC Initiative also includes activities to support Francophone immigration to the Acadian communities in New Brunswick.Footnote 8Footnote 9

1.2.3 Management and Governance

The OLMC Initiative combines strategies for immigration and integration, and involves efforts in Canada and abroad. Management and governance rely on many players within IRCC and external to IRCC. Various branches within IRCC’s National Headquarters (NHQ)Footnote 10, as well as Regional Offices in Canada and Canadian Missions AbroadFootnote 11, are responsible for the management and delivery of activities under the OLMC Initiative.Footnote 12 In January 2014, IRCC also created an Official Languages Secretariat (OLS) which ensures the coordination and monitoring of the department’ official language responsibilities in relation to Part VII of the OLA.

Key partners and stakeholders involved in the OLMC Initiative include the Fédération des communautés francophones et acadienne (FCFA) and the Réseaux en immigration francophone (RIFs) representing FMCs, as well as other government departments, such as PCH and Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), provincial/territorial governments, and Service Provider Organizations (SPOs) providing IRCC-funded settlement services to French-speaking newcomers outside of Quebec. Employers in Canada and public employment agencies in countries abroad, as well as researchers, academics, and other non-government organizations, such as the Réseaux de développement économique et d’employabilité (RDÉEs), are also important.

The IRCC-FMC Committee, consisting of 15 members (seven from IRCC and seven from FMCs, as well as one provincial/territorial government representative), meets in person at least twice a year, and is co-chaired by IRCC’s Official Languages Champion and the FCFA (representing FMCs). In addition to this committee structure, the Department uses existing IRCC fora to advance francophone immigration outside of Quebec, such as the Official Languages Steering Committee and the National Settlement Council.Footnote 13 It also participates in the broader interdepartmental governance and accountability structure supporting the Roadmap 2013-2018. Three main committees make up this formal governance structure: the Committee of Assistant Deputy Ministers on Official Languages (CADMOL), the CADMOL Executive Sub-Committee (EX-CADMOL), and the Official Languages Directors General Forum.Footnote 14

1.2.4 Expected Outcomes of the OLMC Initiative

Immediate Outcomes

- Partners and stakeholders are engaged in promotion, recruitment and settlement and implement strategies to address newcomer needs in FMCs

- Employers are aware of opportunities (mechanisms and tools) to hire qualified French-speaking immigrants

- Prospective French-speaking immigrants are aware of opportunities (mechanisms and tools) to immigrate to FMCs

- French-speaking clients receive settlement services that address their settlement needs

- Increased awareness and understanding among policy makers and stakeholders on topics related to immigration to OLMCs

Intermediate Outcomes

- French-speaking clients use official languages to function and participate in Canadian society

- French-speaking clients in FMCs participate in local labour markets, broader communities and social networks

- French-speaking clients make informed decisions about life in Canada, enjoy rights and act on their responsibilities in Canadian society

- Increased number of French speaking economic immigrants settling in FMCs

The OLMC Initiative contributes to two of IRCC’s Strategic Outcomes (SO) under the Program Alignment Architecture (2016): SO: 1 – Migration of permanent and temporary residents that strengthens Canada’s economy and SO: 3 – Newcomers and citizens participate in fostering an integrated society.Footnote 15

1.3 Purpose of the Evaluation

The main characteristics of French-speaking immigrants admitted to Canada as permanent residents and settling in FMCs are summarized below and compared to the overall population of immigrants settling in these communities. For the purposes of this evaluation:

- French-speaking immigrants have been identified using the measure currently employed by the department to count “French-speaking” immigrants, which includes those with a mother tongue of French, and those whose only official language spoken is French when their mother tongue is a language other than French.Footnote 16

- All French-speaking immigrants residing outside of Quebec are considered to be living in a FMC. Province/territory of residence is inferred from admission data on province/territory of intended destination.

1.3.1 All French-Speaking Immigrants

Generally, French-speaking immigrants settling in FMCs between 2003 and 2016 were similar to the overall population of immigrants settling outside of Quebec in relation to gender and age distribution. However, a greater percentage of French-speaking immigrants became permanent residents under the refugee programs (25% compared to 11% for the overall immigrant population outside of Quebec).

While percentages varied, most French-speaking immigrants settling in FMCs during the 2003 to 2016 period were destined to the same provinces as the overall population of immigrants outside of Quebec: Ontario (61% compared to 54% of the overall population), Alberta (13% compared to 14% of the overall population), British Columbia (10% compared to 19% of the overall population), and Manitoba (6% for both groups). However, a greater percentage of French-speaking immigrants were destined to New Brunswick (5% compared to 1% for the overall population outside of Quebec).

Like the overall immigrant population outside of Quebec during this period, the greatest percentage of French-speaking immigrants settling in FMCs were destined to Toronto (31% compared to 42% for the overall population). However, second most frequent destination for French-speaking immigrants was Ottawa (21% compared to 3% for the overall population), whereas Vancouver was the second most frequent destination for the overall population outside of Quebec (16% compared to 8% for French-speaking immigrants).

In terms of country of citizenship, 21% of French-speaking immigrants settling in FMCs during the 2003 to 2016 period originated from France, 13% from the Democratic Republic of Congo, 9% from Haiti, 6% from the Federal Republic of Cameroon and 4% from Morocco. A little over half (53%) indicated a mother tongue of French, 9% indicated a mother tongue of Arabic and 7% indicated a mother tongue of Creole.

The source country and language profiles of French-speaking immigrants varied significantly from those of the overall population of immigrants settling outside of Quebec during this period. The most common countries of citizenship for the overall immigrant population outside of Quebec included: India (15%), the Philippines (14%), the People’s Republic of China (13%), Pakistan (5%) and the United States of America (4%). In terms of mother tongue, the most common languages were: Tagalog (12%), English (11%), Mandarin (10%), Punjabi (7%) and Arabic (6%).

1.3.2 French-Speaking Adult Immigrants (18 years of age and older)

About three-quarters of immigrants (both French-speaking and the overall immigrant population) settling outside of Quebec between 2003 and 2016 were adults (18 years of age or older) at the time of admission (74% and 76% respectively). Compared to the overall population outside of Quebec, a greater percentage of these French-speaking adult immigrants were single at the time of admission to Canada (34% compared to 25% for the overall population). In terms of education and skill level, while a smaller percentage of these French-speaking adult immigrants settling outside of Quebec during this period had a university-level education compared to the overall population (37% compared to 45%), a similar proportion were high skilled at the National Occupational Code (NOC) 0, A or B levels (27% of French-speaking immigrants compared to 28% for the overall population).Footnote 17

2. Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Approach

The evaluation scope and approach were determined during a planning phase, in consultation with IRCC branches involved in the design, management and delivery of the OLMC Initiative. The terms of reference for the evaluation were approved by IRCC’s Departmental Evaluation Committee in November 2015, and data collection was undertaken primarily by the IRCC Evaluation Division between November 2015 and November 2016, with some support from an external consultant for the interviews.

The evaluation assessed the relevance and performance of the OLMC Initiative for the period of 2012 to 2016, and was guided by the program logic model, and an evaluation framework, outlining the evaluation questions, performance indicators and planned methods for the study.Footnote 18 The evaluation questions are presented below.

Evaluation Questions

Relevance

- To what extent does the OLMC initiative continue to address a demonstrable need, as well as align with IRCC and GoC priorities and federal roles and responsibilities?

Performance - Immediate Outcomes

- To what extent has the OLMC Initiative increased knowledge and awareness among takeholders and policy-makers of topics related to immigration to OLMCs?

- To what extent has the OLMC Initiative engaged partners and stakeholders and/or expanded existing networks to foster immigration and integration in FMCs?

- Are employment stakeholders in FMCs informed about opportunities to hire French-speaking immigrants?

- Are French-speaking foreign nationals informed about opportunities to immigrate to FMCs?

- To what extent do French-speaking settlement clients in FMCs receive settlement services in French that meet their settlement needs?

Performance - Intermediate Outcomes

- To what extent are French-speaking economic immigrants settling in FMCs?

- Are French-speaking settlement clients in FMCs using Canada’s official languages to function and participate in Canadian society?

- Are French-speaking settlement clients in FMCs participating in local labour markets and social/community activities?

- Do French-speaking settlement clients in FMCs have sufficient knowledge to make informed decisions about their life in Canada?

- To what extent are the Réseaux en immigration francophone (RIFs) contributing to the attraction, integration and retention of French-speaking immigrants in FMCs?

Performance - Design and Delivery

- To what extent are the management and governance of the OLMC initiative effective?

- To what extent are performance measurement, monitoring and reporting for the OLMC initiative effective?

Performance - Resource Utilization

- To what extent have OLMC Initiative resources been efficiently utilized to support the production of outputs and achievement of expected outcomes?

2.2 Evaluation Scope

The scope of the evaluation of the OLMC Initiative encompassed IRCC’s activities and intended results for the OLMC Initiative under the Roadmap 2013-2018, concentrating on French-speaking immigrants in FMCs outside of Quebec. Results related to English-speaking immigrants in ESCQ were only considered in relation to research and knowledge sharing activities, given the limited role of the federal government with respect to selection and integration of immigrants in Quebec.

The reporting period for the evaluation primarily covered the timeframe of 2012 to 2016, assessing progress made towards the achievement of expected outcomes since the 2012 evaluation,Footnote 19 with some consideration of results since 2003 to better assess trends over time.Footnote 20 Key areas of focus included promotion and recruitment activities and results for Francophone immigration to FMCs, as well as settlement activities and integration outcomes for French-speaking immigrants settling in FMCs.Footnote 21

2.3 Data Collection Methods

Multiple lines of evidence were used to gather qualitative and quantitative data from a wide range of perspectives, including IRCC program representatives, external stakeholders, and French-speaking foreign nationals and newcomers to Canada.Footnote 22 Briefly, they included:

- Document review and key informant interviews;

- Surveys:

- Online survey of French-speaking newcomers;

- Settlement Client Outcomes Survey (SCOS) (results for French-speaking newcomers); and

- Online survey on Francophone immigration with French-speaking foreign nationals;

- Analysis of data from:

- Global Case Management System (GCMS) on admissions to Canada;

- Longitudinal Immigration Database (IMDB) on economic indicators and mobility;

- Immigration Contribution Agreement Reporting Environment (iCARE) on the use of IRCC-funded settlement services; and

- IRCC’s financial system and the Grants and Contributions System (GCS).

- Case studies on:

- Destination Canada and other activities to promote francophone immigration; and

- The Réseaux en immigration francophone (RIF).

2.4 Limitations and Considerations

The main limitation of the study was the incomplete information to precisely identify the population of French-speaking immigrants residing outside of Quebec. As previously noted, the measure used to estimate the number of “French-speaking” immigrants does not fully capture this population. As a mitigation strategy, additional information, obtained through iCARE and the surveys, was used in various lines of evidence (e.g. the survey of French-speaking newcomers) to more reliably identify French-speaking immigrants included in these analyses. The different lines of evidence were complementary and reduced information gaps, as well as enabled the triangulation of findings. The mitigation strategies, along with the triangulation of findings, were considered to be sufficient to ensure that the findings are reliable and can be used with confidence.Footnote 23

3. Key Findings: Relevance

Finding: The OLMC Initiative supports IRCC’s legislative obligations, is consistent with federal roles and responsibilities, and is well aligned with departmental and Government of Canada objectives and priorities for immigration. While it responds to a continued need to support the vitality of FMCs, it is less active with respect to ESCQ given the department’s limited role in relation to immigration and integration of newcomers in Quebec.

3.1 Federal Roles and Responsibilities

The OLMC Initiative supports the Government of Canada’s statutory obligations, articulated in both the OLA and IRPA, to support and enhance the vitality of OLMCs.

- Part VII of the OLA delineates the federal responsibility for “enhancing the vitality of the English and French linguistic minority communities in Canada and supporting and assisting their development; and fostering the full recognition and use of both English and French in Canadian society”. It further emphasizes that “every federal institution has the duty to ensure that positive measures are taken for the implementation of the[se] commitments…while respecting the jurisdiction and powers of the provinces”.Footnote 24

- This commitment is also recognized in IRPA in its objective “to support and assist the development of minority official languages communities in Canada”.Footnote 25

While immigration is a joint federal/provincial responsibility,Footnote 26 the federal government has a limited role with respect to immigration and integration in Quebec due to the Canada-Québec Accord, which states that “Québec has sole responsibility for the selection of immigrants destined to that province”Footnote 27, and that “Canada undertakes to withdraw from the services…for the reception and the linguistic and cultural integration of permanent residents in Québec”, as well as “from specialized economic integration services…to permanent residents in Québec”.Footnote 28

Thus, while IRCC has an obligation to support OLMCs, both FMCs and ESCQ, this commitment is addressed differently in Quebec compared to the rest of Canada given the limited federal role. IRCC plays a supporting role in relation to ESCQ, focusing on knowledge development and sharing, whereas it plays a leading role in relation to the rest of Canada, focusing on the promotion of Francophone immigration to FMCs and the provision of settlement services to French-speaking immigrants in these communities to assist with their integration.

3.2 IRCC and GoC Objectives and Priorities

The OLMC Initiative supports departmental obligations with respect to the OLA and IRPA (as described above), as well as its objectives for Francophone immigration, which are aligned with FMC and provincial/territorial government priorities. Since 2003, the department has had as one of its objectives to ensure that 4.4% of immigrants settling outside Quebec were French-speaking, aiming to do this by 2023. This target was established by the CIC-FMC Steering Committee, in collaboration with FMC stakeholders, and first articulated in its Strategic Framework.Footnote 29 In 2013, the GoC also publicly committed to increasing the annual proportion of economic Francophone immigration outside of Quebec to 4% by 2018.Footnote 30

In addition, the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Ministers for immigration have made Francophone immigration one of their prioritiesFootnote 31, and some provincial governments have set their own targets (e.g. Ontario (5%), New Brunswick (33%), and Manitoba (7%)).Footnote 32 In July 2016, in recognition of the Francophonie as a “fundamental element of the Canadian federation”, Provincial-Territorial Premiers called on the federal government to increase the level of francophone immigration outside of Quebec to 5%.Footnote 33 Furthermore, in March 2017, federal, provincial and territorial ministers responsible for immigration and the Canadian Francophonie met and “agreed to work together to enhance promotion efforts aimed at French-speaking immigrants and to foster their recruitment, selection and integration”.Footnote 34

The OLMC Initiative is also aligned with Canada’s objectives and priorities for immigration. As previously noted, the Initiative is a key commitment under the Immigration pillar of the Roadmap 2013-2018. The Roadmap 2013-2018 recognized that attracting immigrants and fostering their integration into Canadian society is important to Canada’s long-term prosperity and growth, and considered speaking one or more of Canada’s official languages as a crucial step in the social, cultural and economic integration of newcomersFootnote 35. The Roadmap 2013-2018 was renewed under Canada’s Economic Action Plan 2013Footnote 36, which focused on economic immigration and attracting talented newcomers with the skills and experience required by Canada’s economy.Footnote 37 The Initiative continues to be aligned with the objectives for immigration outlined in Budget 2017, which focus on supporting immigration programs that help to attract top talent to Canada, as well as its humanitarian interests related to refugee protection.Footnote 38

3.3 Continued Need

Efforts to promote Francophone immigration and facilitate the integration of French-speaking newcomers in FMCs have been ongoing since 2003. At that time, the Strategic Framework recognized immigration as “an important factor in the growth of Canada’s population”.Footnote 39 It was noted that FMCs had not benefited as much from immigration as the Anglophone population, and that they had received limited benefits from Francophone immigration, as many French-speaking immigrants were settling in Quebec. Moreover, it was observed that immigrants, like most Canadians, were attracted to the major cities for economic and social reasons. As a result, the Strategic Framework set a target of 4.4% for Francophone immigration to FMCs, and contended that “[m]easures should be developed to help the Francophone and Acadian communities profit more from immigration to mitigate their demographic decline”.Footnote 40

Years later, there is still a need to foster the demographic and economic growth, as well as the vitality, of FMCs, and immigration is viewed as a means to do this.Footnote 41 The targets set for Francophone immigration, as well as Francophone economic immigration, to FMCs are still ongoing and have not been met.Footnote 42 In June 2015, the Standing Committee on Official Languages reported that demographic growth in FMCs is crucial to community vitality “in order to build a growing economy and maintain certain rights, such as access to government services in both official languages.” It also observed that FMCs are facing similar challenges as other communities related to rural out-migration and low birth rates, and that they need immigrants to address labour needs and to contribute to their vitality.Footnote 43 Focusing on the 4% target for Francophone economic immigration to FMCs, the Standing Committee on Official Languages concluded that it was important for the federal government and all of its agencies to take positive measures to achieve this target.Footnote 44

4. Key Findings: Performance – Promotion and Recruitment of French-speaking Immigrants in FMCs

4.1 Immigration of French-Speaking Immigrants

Finding: While the numbers of French-speaking immigrants settling in FMCs increased in many of the years since 2003, their relative weight within the overall immigrant and economic immigrant populations outside of Quebec has remained below IRCC’s targets.

While estimates are conservative,Footnote 45 a total of 42,831 French-speaking permanent residents were destined to FMCs outside of QuebecFootnote 46 between 2003 and 2016. Forty-four percent were admitted to Canada under the economic classes, representing 1.13% of economic immigration outside of Quebec during this period. In comparison, the relative proportion of French-speaking immigrants within the overall immigrant population averaged 1.47% (see Table 1).

Table 1: Number and Relative Percentage of French-Speaking Immigrants Destined to Provinces or Territories outside of Quebec (2003 to 2016) – Overall and Economic Immigrants Only

| Year of Admission | All French-Speaking Immigrants (Target 4.4%) |

French-Speaking Economic Immigrants (Target 4%)Table 1 note * |

|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 1,830 (1.01%) | 848 (0.86%) |

| 2004 | 2,301 (1.20%) | 1,067 (0.99%) |

| 2005 | 2,658 (1.21%) | 1,208 (0.93%) |

| 2006 | 2,683 (1.30%) | 1,134 (1.01%) |

| 2007 | 2,905 (1.52%) | 1,346 (1.30%) |

| 2008 | 3,107 (1.54%) | 1,596 (1.33%) |

| 2009 | 3,217 (1.59%) | 1,678 (1.41%) |

| 2010 | 3,483 (1.54%) | 1,668 (1.12%) |

| 2011 | 3,547 (1.80%) | 1,374 (1.14%) |

| 2012 | 3,676 (1.81%) | 1,606 (1.33%) |

| Year of Admission | All French-Speaking Immigrants (Target 4.4%) |

French-Speaking Economic Immigrants (Target 4%)Table 1 note * |

|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 3,358 (1.62%) | 1,433 (1.26%) |

| 2014 | 2,764 (1.32%) | 1,280 (0.97%) |

| 2015 | 2,907 (1.30%) | 1,108 (0.79%) |

| 2016 | 4,395 (1.81%) | 1,689 (1.36%) |

| All French-Speaking Immigrants (Target 4.4%) |

French-Speaking Economic Immigrants (Target 4%)Table 1 note * |

|

|---|---|---|

| Grand Total | 42,831 (1.47%) | 19,035 (1.13%) |

Source: RDM, Permanent Residents, December 31, 2016

The demographic weight of French-speaking immigrants in the overall immigrant population outside of Quebec increased between 2003 and 2012 and then decreased until 2016, at which time it returned to the 2012 level. During the timeframe for the 4% target, the demographic weight of French-speaking economic immigrants within the economic immigrant population outside of Quebec decreased between 2013 and 2015, but experienced a considerable increase in 2016.

4.2 Interprovincial Mobility among French-Speaking Immigrants

Finding: While some French-speaking Principal Applicants left FMCs to settle in Quebec, FMCs gained more French-speaking Principal Applicants from Quebec out-migration than they lost between 2003 and 2014.

Overall, 84% of French-speaking immigrants admitted to Canada between 2003 and 2016 were destined to Quebec, while the rest were destined to FMCs.Footnote 47 The evaluation examined patterns of interprovincial mobility among French-speaking immigrants using IMDB data to better understand the extent to which FMCs retain French-speaking immigrants and benefit from secondary migration within Canada, contributing to the size of their communities.

Table 2: Interprovincial Mobility among French-Speaking Principal Applicants (PAs) Admitted to Canada between 2003 and 2014 – Net Change (%) between Province/Territory of Intended Destination and Province/Territory of Residence in 2014

| Province | Net change (%) |

|---|---|

| Atlantic (excl. New Brunswick) | -3.1% |

| New Brunswick | -18.3% |

| Quebec | -4.4% |

| Ontario | 14.7% |

| Manitoba | -15.2% |

| Saskatchewan | 48.9% |

| Alberta | 95.0% |

| British Columbia | 21.6% |

| Territories | 64.9% |

Source: IMDB 2014

When looking at the 2003 to 2014 admissionsFootnote 48, Quebec experienced a decrease in its number of French-speaking PAs of about 4% due to interprovincial mobility. For provinces/regions associated with FMCs, only New Brunswick and the remaining Atlantic region, as well as Manitoba lost French-speaking PAs as a result of interprovincial mobility (see Table 2).

Overall, more French-speaking PAs left Quebec to settle in provinces/regions associated with FMCs than the reverse, producing a net gain of 4 225, and increasing the overall share of the French-speaking immigrant population in FMCs to about 18%.

4.3 Targets for Francophone Immigration

Finding: There is an indication that IRCC’s targets for Francophone immigration outside of Quebec will be very challenging to achieve in light of the department’s strategies which focus mainly on promotion and options for temporary residence. While recent efforts under Express Entry aim to facilitate the permanent residence of French-speaking candidates seeking to settle in FMCs, it is too early to assess the impacts of this mechanism.

Evaluation findings suggest that the targets set for Francophone immigration, though still ongoing, are ambitious and will be difficult to achieve, and that more significant efforts on the part of the department are needed if progress is to be made towards achieving these targets.

4.3.1 Consideration of IRCC’s Targets

The 2003 target of 4.4% for Francophone immigration was based on the Census estimate of the overall proportion (i.e. demographic weight) of Francophones in the Canadian population outside of Quebec in 2001. The objective, set out in the Strategic Framework, was for FMCs to attract and retain at least 4.4% of French-speaking immigrants in the immigrant population outside of Quebec in order to benefit from immigration and maintain their long-term demographic weight. This was understood to mean that FMCs would have to gradually receive more French-speaking newcomers in the coming years.Footnote 49

At the time of the Strategic Framework, it was estimated that 3.1% of immigrants to Canada outside Quebec were French-speaking.Footnote 50 However, this estimate included individuals reporting the ability to speak both English and French, regardless of which official language they most commonly used, and as a result, likely overestimated the demographic weight of French-speaking immigrants.Footnote 51 Originally, “it was expected that the target would be reached by 2008”, but “following certain challenges, including questions about the actual definition of a “French-speaking immigrant” and about data collection, [the] target was pushed back over the years to 2023.”Footnote 52 In spite of these difficulties in achieving the overall 4.4% target, a 4% target was set for Francophone economic immigration in 2013 to be achieved by 2018.

Statistics Canada (2017) projections based on “first official language spoken” (FOLS)Footnote 53 suggest that while many regions in Canada (except the Atlantic) could see the numbers of their French-speaking populations increase or stabilize by 2036, their demographic weight could decrease. This decrease is attributed mainly to the fact that the relative share of immigrants with a mother tongue other than English or French who adopt English as the home language or who, of the two official languages, only know English, should continue to grow at a faster rate than the share of those who transition to French. Statistics Canada further estimates that for immigration to maintain the demographic weight of the French-speaking population outside of Quebec at the 2016 level (estimated at 3.7%)Footnote 54, about 275,000 French-speaking immigrants would need to settle in Canada outside of Quebec between 2017 and 2036 (estimated at 5.1% of immigration outside of Quebec).Footnote 55 This roughly represents 13,750 French-speaking immigrants per year for the next 20 years settling in FMCs, which is well above current trends.Footnote 56

4.3.2 Promotional Efforts and Immigration Strategies

Findings from the interviews and documentFootnote 57 review identified a need for more efforts to increase Francophone immigration to FMCs. Of note, it was highlighted in the interviews that the current approach is not well supported by the appropriate tools to have the necessary impact.

To date, IRCC’s efforts to facilitate francophone immigration to FMCs have relied primarily on promotion and recruitment activities, as well as mechanisms to facilitate temporary residence through the work permit programs. In terms of promotion and recruitment, IRCC has undertaken a variety of activities, many of which have focused on European pools of French-speaking candidates in countries, such as France and Belgium. However, efforts targeting Africa and other regions abroad have been growing over the years.Footnote 58Footnote 59

In terms of mechanisms to facilitate temporary residence, the Francophone Significant Benefit (FSB) programFootnote 60 was created in June 2012 with the expectation that Canadian work experience acquired by applicants through this program could eventually help them to qualify for the permanent residence programs.Footnote 61 It provided a Labour Market Opinion (LMO) exemption for employers hiring temporary foreign workers in skilled positions (National Occupation Classification Levels 0, A and B) outside of Quebec. While not explicitly designed as a pathway to permanent residence, the FSB program provided a mechanism to better position French-speaking temporary residents to make this transition. However, it was cancelled in September 2014 due to concerns about the displacement of French-speaking Canadians in FMCs by temporary foreign workers.Footnote 62 In June 2016, a new Mobilité Francophone program was launched, comparable to the preceding FSB program, under the International Mobility Program (IMP).Footnote 63 IRCC administrative data show that there were 1,778 entries under the FSB program between 2012 and 2016.Footnote 64 As of March 31, 2017, a total of 675 individuals with a prior FSB work permit had transitioned to permanent residence (90% through the economic immigration programs),Footnote 65 and there were 405 entries under the new Mobilité Francophone program.Footnote 66

There are limits, however, to what can be achieved through promotional activities and mechanisms for temporary residence. Eventually, there needs to be a way to facilitate the permanent residence of French-speaking candidates interested in immigrating to FMCs. The 2012 evaluation recognized both the importance and the limitations of IRCC’s promotional efforts under the Initiative, and noted that “If more Francophone newcomers can be convinced to settle in FMCs, they must be allowed to immigrate to Canada permanently.”Footnote 67

IRCC does not have a specific program to facilitate the permanent residence of French-speaking individuals in FMCs. IRCC administrative data (2003 to 2016) show that, while promotional activities focus on the economic immigration programs, French-speaking immigrants have taken advantage of a range of programs over the years to become permanent residents of Canada. In fact, during the 2003 to 2016 period, 52% obtained their permanent residence under the sponsored family and refugee programs, compared to 44% who did so under the economic immigration programs. Moreover, the Provincial Nominee Program (PNP)Footnote 68, which has as one of its objectives to support the development of OLMCs, brought in only 9%, and the Canadian Experience Class (CEC) program,Footnote 69 which facilitates the transition to permanent residence for individuals with qualified Canadian work experience, only brought in 4% of French-speaking immigrants during this timeframe.

Although not a program, the Express Entry system offers a means to support Francophone immigration objectives under the OLMC Initiative. Introduced in January 2015, Express Entry manages applications for the Federal Skilled Workers program, the Federal Skilled Trade program, the CEC and a portion of the PNP. Candidates are assigned points based on their competencies and qualifications, and then ranked against each other. Top-ranking candidates are invited to apply. Express Entry candidates who speak both of Canada’s official languages can receive points for their proficiency in their second official language, thus increasing the chances of being invited to apply for bilingual French-speaking candidates.

In November 2016, IRCC introduced changes to the Express Entry system, including a Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA) exemption for candidates already in Canada as temporary workers under Mobilité Francophone to permit them to receive job offer points in Express Entry. In addition, the department announced further changes to be introduced in June 2017 to award additional points to candidates who have strong French language skills. IRCC is also developing a new functionality to send targeted messages to French-speaking candidates in the Express Entry pool to inform them about opportunities to settle in FMCs. This new functionality is anticipated for the Fall 2017.

Although too early to assess the impacts of Express Entry and its recent changes in support of Francophone immigration, early results indicate that 2.9% of the 33,406 immigrants admitted through this system in 2016 were French-speaking.Footnote 70

4.4 Awareness of Employment-Related Stakeholders

Finding: The OLMC Initiative has contributed to raising awareness among employment-related stakeholders about the opportunities and mechanisms available to hire French-speaking immigrants. However, the priority for employers is hiring the best qualified candidates, while knowledge of French is not paramount.

IRCC has undertaken various activities to promote awareness of opportunities and mechanisms to recruit and hire French-speaking immigrants to employment stakeholders, such as liaison trips to meet with employers in Canada conducted by the Paris, Rabat, Tunis and Dakar missions, initiatives undertaken by the RIFs and activities in relation to Express Entry led by IRCC’s Employer Liaison Network (ELN).Footnote 71

While difficulties in tracking outcomes were noted in the interviews, it was mentioned that some progress is being made in terms of employer awareness, with more employers starting to see immigration as a viable option to fulfill their operational needs. Some RIFs pointed to improved employer awareness, but there was also a recognition that employer engagement is a challenge.

Findings from the interviews and document reviewFootnote 72 highlighted that specific incentives or mechanisms, such as LMIA work permit exemptions, Express Entry, or credential recognition, can help facilitate the hiring of French-speaking immigrants by employers. However, the primary interest of employers is to find qualified candidates with the skills they need to meet their operational requirements. The 2014-2015 Consultations on Francophone immigration noted that employers primarily want a competent employee who integrates quickly and do not necessarily see the added value of bilingualismFootnote 73, and that most employment outside of Quebec, particularly in the West, requires an advanced level of English.Footnote 74

4.5 Awareness of French-speaking Foreign Nationals and Importance of Employment

Finding: The OLMC Initiative has contributed to raising awareness among French-speaking foreign nationals about opportunities to live and work in Canada outside of Quebec. Employment is a key factor in this decision-making, and Destination Canada provides a forum for potential candidates to pursue opportunities with Canadian employers.

IRCC has undertaken various activities to promote awareness of opportunities to live and work in FMCs in Canada to French-speaking foreign nationals. Paris is the lead mission abroad with respect to the promotion of Francophone immigration. Other missions, particularly Rabat, Dakar, Tunis and Mexico, work in coordination, and with the support of Paris, to conduct promotional activities as well.Footnote 75

In order to better understand the contribution of IRCC’s promotional activities to the awareness of French-speaking candidates about the possibilities to live and work in Canada outside of Quebec, the evaluation examined some of the activities conducted by the Paris mission, the largest purveyor of these activities, focusing on its information sessions and the Destination Canada job fair.

Information sessions are provided in-person and by webconference, and include information on FMCs and immigration tools. In 2015, the Paris mission conducted 58 in-person information sessions, which attracted a total of 3,884 registered participants,Footnote 76 as well as 37 information sessions by webconference, which attracted a total of 6,183 registered participants.Footnote 77 Destination Canada is IRCC’s flagship promotional event; it provides information, as well as access to various job postings and opportunities to meet with Canadian employers and provincial/territorial government and FMC representatives. The Destination Canada event has been ongoing since 2003, and the level of interest generated by this event in recent years (2012 to 2016) is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3: Application and Attendance Results for Destination Canada – 2012 to 2016

| Years | Number of candidates who applied to participate | Number of candidates who completed a registration with a CV | Number of candidates invited to participate in Destination Canada | Number of candidates who attended the Destination Canada event |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 20,931 | 8,179 | 4,657 | 3,272 |

| 2013 | 19,295 | 7,603 | 3,765 | 2,658 |

| 2014 | 12,109 | 5,635 | 3,920 | 2,905 |

| 2015 | 9,720 | 4,132 | 3,174 | Cancelled |

| 2016 | 12,760 | 6,418 | 4,704 | 3,588 |

Source: Paris mission

A Survey on Francophone Immigration was conducted, as part of the evaluation, to examine the experiences of French-speaking foreign nationals in relation to their participation in promotional activities led by the Paris mission (Destination Canada as well as in-person and webconference information sessions).Footnote 78 A total of 2,568 candidates participated in the survey, including 2,224 participants in IRCC promotional activities and 344 non-participants.

When the factors affecting candidates’ plans and decision-making for living and working in Canada were explored in this survey, findings showed that employment is an important factor, with 91% of candidates surveyed reporting more/better professional opportunities as important or very important. Similarly, the importance of employment to the attraction and retention of French-speaking immigrants was noted in the interviews and document review.Footnote 79

Opportunities related to employment are provided by IRCC through its Destination Canada job fair; however, survey findings indicated areas for improvement. Many Destination Canada participants surveyed were dissatisfied with the range of job offers posted (24% somewhat dissatisfied and 19% dissatisfied), as well as with opportunities to network and make contacts at the event with employers (23% somewhat dissatisfied and 20% dissatisfied). Some suggestions for improvement proposed by participants surveyed called for more employers to be present and a larger variety of employment sectors be represented at Destination Canada.

4.6 Dissemination of Information and Contribution to Decision-Making

Finding: The information disseminated to French-speaking candidates through IRCC promotional activities is generally perceived to be useful and helpful to participants in their decision-making to live and work in Canada. There is also an indication that participation in a combination of promotional activities can maximize the benefits of this information for participants.

4.6.1 Usefulness of Information and Opportunities for Questions

The effectiveness of disseminating information through IRCC’s promotional activities (Destination Canada as well as in-person and webconference information sessions) was also examined using the Survey on Francophone Immigration.

Most participants surveyed were at least somewhat satisfiedFootnote 80 with the usefulness of the information provided and opportunities to ask and receive answers to questions during these activities. Survey findings also suggested that Destination Canada and webconference platforms can make it more difficult for participants to ask questions to better address their specific information needs, as well as highlighted the potential benefits of participating in more than one type of activity for disseminating information to French-speaking candidates.

Information sessions (in-person and/or by webconference):

- 69% of participants were satisfied, and 24% somewhat satisfied, with the usefulness of the information provided.

- 52% were satisfied, and 32% somewhat satisfied, with opportunities to ask and receive answers to questions.

- When the satisfaction levels with opportunities for questions were compared for those who had participated in an in-person session, a webconference session or both:

- 59% indicated being satisfied and 27% somewhat satisfied when they had participated in an in-person session, and 52% indicated being satisfied and 33% somewhat satisfied when they had participated in both types of sessions; whereas

- 39% indicated being satisfied and 38% somewhat satisfied when they had participated in a webconference session.

Destination Canada:

- 57% of participants were satisfied, and 31% somewhat satisfied, with the usefulness of the information provided.

- 46% were satisfied, and 37% somewhat satisfied, with opportunities to ask and receive answers to questions.

- When satisfaction levels with the usefulness of information provided were compared for those who had participated in Destination Canada and another activityFootnote 81 to those who had participated in Destination Canada only:

- 61% indicated being satisfied and 30% somewhat satisfied when they had participated in Destination Canada and another type of promotional activity; whereas

- 52% indicated being satisfied and 32% somewhat satisfied when they had participated in Destination Canada only.

4.6.2 Contribution to Decision-Making

When the contribution to decision-making was examined through the Survey on Francophone immigration, many of those surveyed indicated that their participation in IRCC’s promotional activities had helped them at least somewhatFootnote 82 in their decision-making to live and work in Canada. In addition, survey findings suggested that there are potential benefits of participating in more than one type of activity for decision-making among French-speaking candidates.

Information sessions (in-person and/or by webconference):

- 84% of participants surveyed indicated that their participation in these sessions had helped them at least somewhat with their decision-making.Footnote 83

- When perceptions of the helpfulness of the information sessions were compared for those who had participated in an in-person session, a webconference session or both:

- 75% indicated that the information session had helped them quite a bit or a great deal with their decision-making when they had participated in both types of sessions; whereas

- 67% and 65% indicated that the information session had helped them quite a bit or a great deal with their decision-making when they had participated in an in-person or webconference session respectively.

- When perceptions of the helpfulness of the information sessions were compared for those who had participated in an in-person session, a webconference session or both:

Destination Canada:

- 70% of participants surveyed indicated that their participation in the job fair had helped them at least somewhat.Footnote 84

- When perceptions of the helpfulness of Destination Canada were compared for those who had participated in Destination Canada and another activity to those who had participated in Destination Canada only:

- 59% indicated that Destination Canada had helped them quite a bit or a great deal with their decision-making when they had participated in the job fair as well as another type of promotional activity; whereas

- 43% indicated that Destination Canada had helped them quite a bit or a great deal with their decision-making when they had participated in the job fair only.

- When perceptions of the helpfulness of Destination Canada were compared for those who had participated in Destination Canada and another activity to those who had participated in Destination Canada only:

4.7 Considering the Possibility of Living and Working Outside of Quebec

Finding: While Quebec remains an attractive destination for many French-speaking immigrants, some participants in IRCC promotional activities are exploring opportunities to live and work in regions outside of Quebec.

Quebec was the destination of choice for 84% of French-speaking immigrants during the 2003 to 2016 timeframe. It was noted in the interviews that Quebec is a considerable competitor with the rest of Canada in terms of promotion of francophone immigration. With this in mind, the evaluation explored the extent to which French-speaking foreign nationals participating in IRCC’s promotional activities had chosen, or were planning, to live and work in FMCs (in addition to or other than Quebec).Footnote 85

The experiences and plans of participants in relation to “going to Canada" were examined using the Survey on Francophone Immigration. Survey findings showed that:

- 23% of participants in IRCC promotional activities were living in Canada at the time of the survey, and 30% had been to Canada since 2013.

- Of those currently living in CanadaFootnote 86, 36% were living in provinces/territories other than Quebec.

- Of those who had been to Canada since 2013Footnote 87, 60% had gone to provinces/territories in addition to or other than Quebec.

- 43% of participants were not living in Canada at the time of the survey, and had not been to Canada since 2013, but were planning to go to Canada in the future.Footnote 88

- Of these, 75% indicated other provinces/territories of interest in addition to or other than Quebec.

When the plans of candidates surveyed in relation to “going to Canada” were examined relative to the different types of promotional activities in which they had participatedFootnote 89, survey findings showed that:

- 88% of participants in Destination Canada and another activity and 84% of participants in Destination Canada only were interested in going to provinces/territories in addition to or other than Quebec; whereas

- 75% of participants in other activities only and 73% of non-participants were interested in doing so.

Although a causal relationship cannot be shownFootnote 90, evidence suggests that participating in Destination Canada, in combination with other promotional activities, can contribute to increasing awareness of the opportunities in FMCs and to considering the possibilities in Canada outside of Quebec.

When the reasons for choosing Quebec were compared to the reasons for choosing other parts of Canada (in addition to or other than Quebec), survey findings showed that the top two reasons for choosing Quebec were the presence of Francophones and French services and employment opportunities, while the top two reasons for choosing other parts of Canada were the presence of natural environments and employment opportunities.Footnote 91

5. Key Findings: Performance – Settlement and Integration of French-Speaking Newcomers in FMCs

5.1 Using Canada’s Official Languages

Finding: French-speaking newcomers residing in FMCs are using both of Canada’s official languages in many settings. While they value the ability to use French and to have access to services and resources in French, they also use English to function and participate in Canadian society outside of Quebec.

The use of Canada’s official languages, as well as the importance of French, were examined for French-speaking newcomers settling in FMCs using a Survey of French-speaking Newcomers, conducted as part of the evaluation. A total of 603 survey respondents completed the survey.Footnote 92 Key findings are highlighted below.

5.1.1 Using Canada’s Official Languages in Various Contexts

French-speaking newcomers surveyed reported using English and French in a variety of settings. For example, 83% of those surveyed indicated using English most of the time when going to stores/restaurants and using public transportation, while 40% indicated using French most of the time when talking to their friends. The use of English was frequently reported in the context of work (58% reported using English most of the time and 24% English and French equally often), while the use of French was most commonly reported in the context of family (44% reported using French most often with their spouseFootnote 93 and 46% French most often with their child/childrenFootnote 94).Footnote 95

These findings are consistent with research using the National Household Survey (2011), which has found that English largely dominates as the language of work in all provinces outside Quebec, with 98% of the population reporting using it in 2011.Footnote 96 They are also aligned with findings from the analysis of results for French-speaking newcomers responding to the Settlement Client Outcomes SurveyFootnote 97, which found that a greater percentage of French-speaking respondents reported using English more often than French outside of the home.

Generally, survey findings showed that English was used most often in public domains, while French was used more notably in private domains, or equally often with English. Not using French was often attributed to the people involved not speaking French or the activity not being available in French.

5.1.2 Importance of French to French-Speaking Newcomers

In spite of frequently using English in their activities, being able to use French and having access to services and resources in French was importantFootnote 98 to the French-speaking newcomers surveyed. Many reported that it was important to be able to use French in their daily life, to connect with French-speaking people in the Francophone community, and to have access to services, resources and education in French. This was consistent with document review findings which noted the commitment of members of OLMCs to their language and to receiving services in that language.Footnote 99Footnote 100

In addition, most French-speaking newcomers surveyed indicated that it was important for their children (or future children) to speak French as well as English, and a number of those surveyed indicated that some of their children had done their school studies in French in a minority French language school in Canada.Footnote 101

When asked about the presence of French in their municipality, many French-speaking newcomers surveyed indicated no presence or a weak presenceFootnote 102 of French in a number of the services and resources in their municipalities, notably in local businesses, stores and restaurants (25% no presence and 59% weak presence), in publications (18% no presence and 62% weak presence) and in health care services (19% no presence and 57% weak presence). Conversely, when asked about the presence of English in their municipality, 88% (on average) of those surveyed indicated a strong presenceFootnote 103 of English in all services and resources.

With this in mind, survey findings highlighted a desire among the French-speaking newcomers surveyed for the presence of French to be augmented in their municipalities, with 86% indicating that the presence of French should increase. There was also an indication of support for the development of the Francophone community, with 81% reporting that it was important for individuals and organizations to work for the development of the Francophone community in their municipality.

In sum, these findings suggest that French-speaking newcomers want to use French, but must use English, as they are in a minority context, where English largely dominates the public domain.

5.2 Economic Integration

Finding: French-speaking immigrants are participating in the labour market at rates comparable to other immigrants in FMCs outside of Quebec. Social assistance use is higher among French-speaking immigrants compared to other immigrants, particularly among the non-economic classes; however, the difference decreases over time.

5.2.1 Incidence of Employment

The IMDB analysis showed that the incidence of employment for French-speaking immigrants (principal applicants, spouses and dependants) admitted to Canada between 2003 and 2014 was fairly stable and similar to other immigrants one to ten years after admission, averaging 68% (compared to 66% for other immigrants). The incidence of employment was found to vary by gender, with men having a higher incidence, on average, compared to women for both French-speaking and other immigrants. The incidence of employment was also higher for French-speaking immigrants with a knowledge of both English and French at admission (compared to those with a knowledge of French only).

When the incidence of employment was compared for economic and non-economic principal applicants (PAs) during this period, it was higher for economic PAs, averaging 81% for French-speaking economic PAs and 79% for other economic PAs, compared to 65% for French-speaking non-economic PAs and 61% for other non-economic PAs (see Figure 1).