Annual Report 2019

ISSN: 1495-0561

Cat. no.: H78E-PDF

PDF version (2.3 MB)

Table of Contents

- Statistical Highlights 2019

- Letter to the Minister

- Chairperson's Message

- About the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board: Acting in the Interest of Canadians

- Regulating Prices of Patented Medicines: Continued Vigilance Necessary

- Key Pharmaceutical Trends: More Expensive Medicines Continue to Influence Sales

- The National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System: Supporting Health Care Decision Making in Canada

- Analysis of Research and Development Expenditures: R&D Investment Falling Short of Target

- Appendix 1: Glossary

- Appendix 2: Patented Medicines First Reported to the PMPRB in 2019

- Appendix 3: Pharmaceutical Trends - Sales

- Appendix 4: Research and Development

Statistical Highlights 2019

Regulatory Mandate

- 1,364 patented medicines for human use were reported to the PMPRB, including 81 new medicines.

- 12 Voluntary Compliance Undertakings were accepted as of December 31, 2019.

- $3.5 million in excess revenues were offset by way of payments to the Government of Canada, in addition to price reductions.

Reporting Mandate

Sales Trends:

- Sales of patented medicines in Canada reached $17.2 billion in 2019, a moderate increase of 3.5% from the previous year.

- Patented medicines accounted for approximately 60% of the sales of all medicines in Canada.

Price Trends:

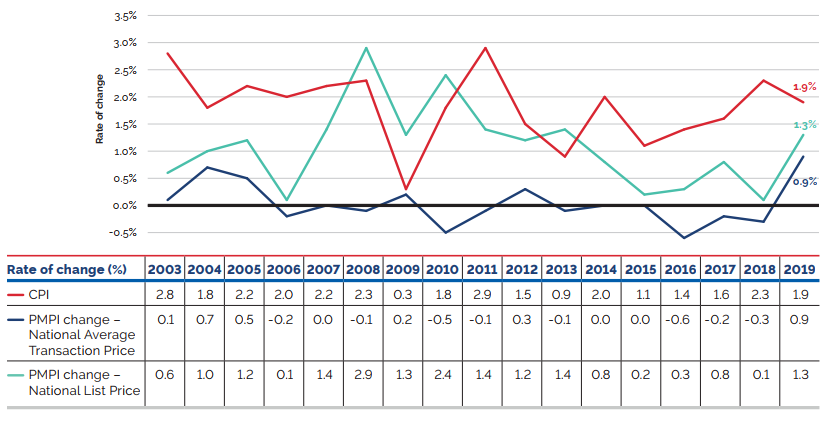

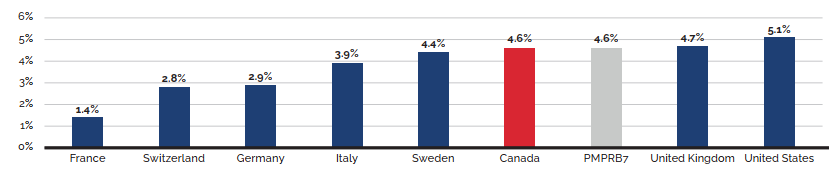

- Prices of existing patented medicines were stable, while the Consumer Price Index rose by 1.9%.

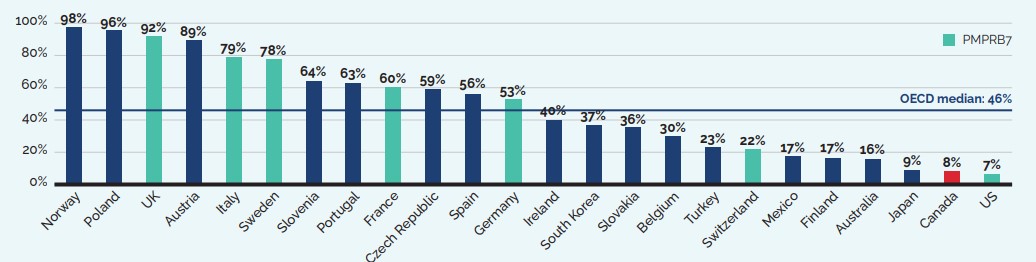

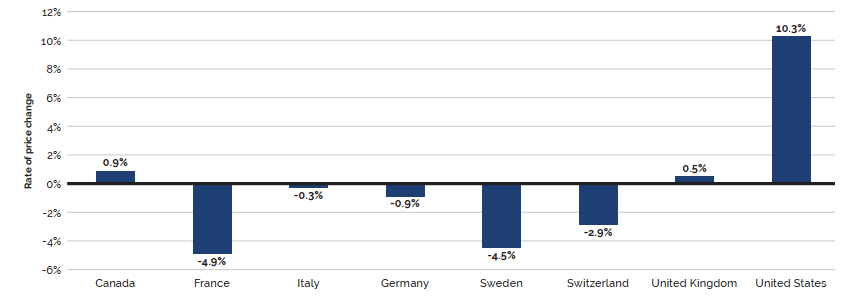

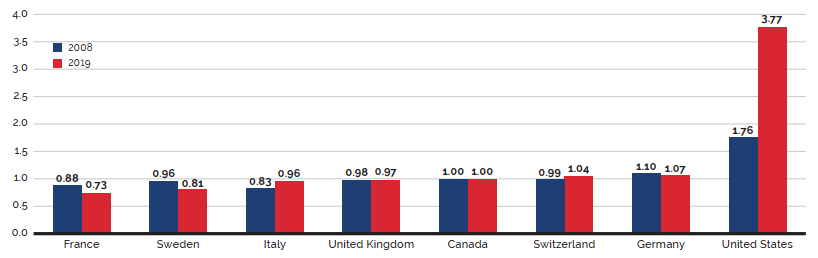

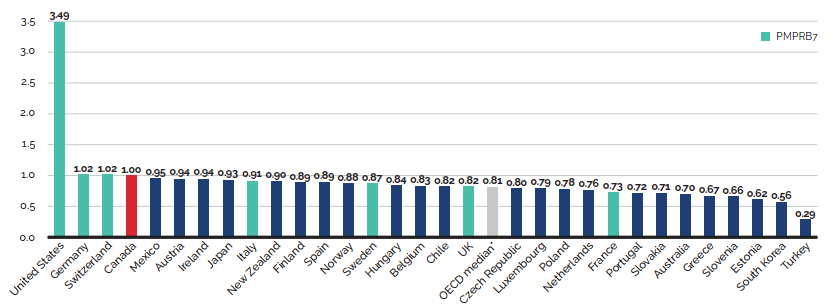

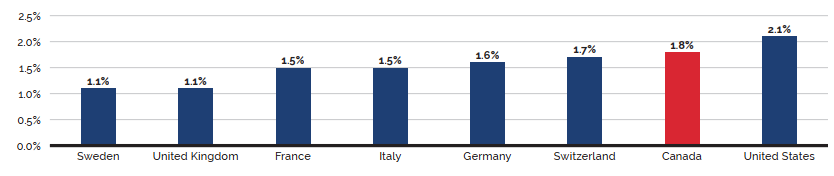

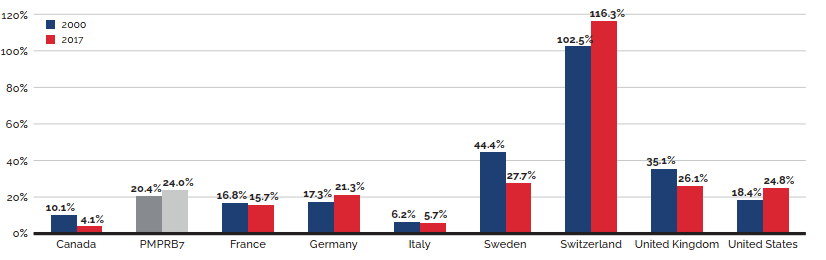

- Canadian prices were fourth highest among the seven PMPRB comparator countries, lower than prices in Switzerland, Germany, and the US.

- Canadian list prices were fourth highest among 31 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, lower only than prices in Switzerland, Germany and the US.

Research and Development:

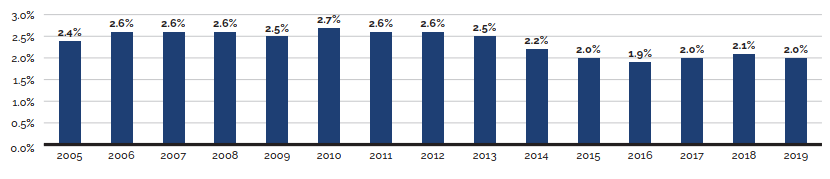

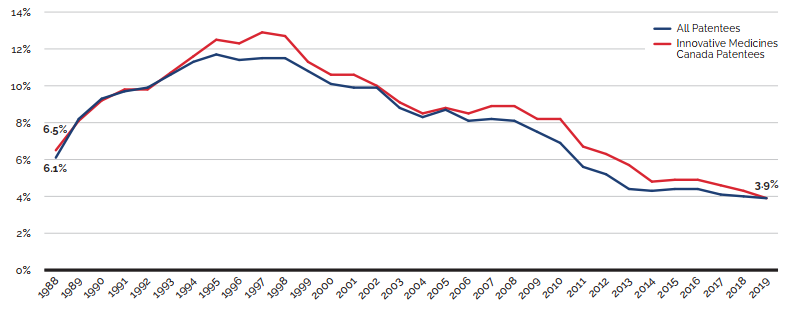

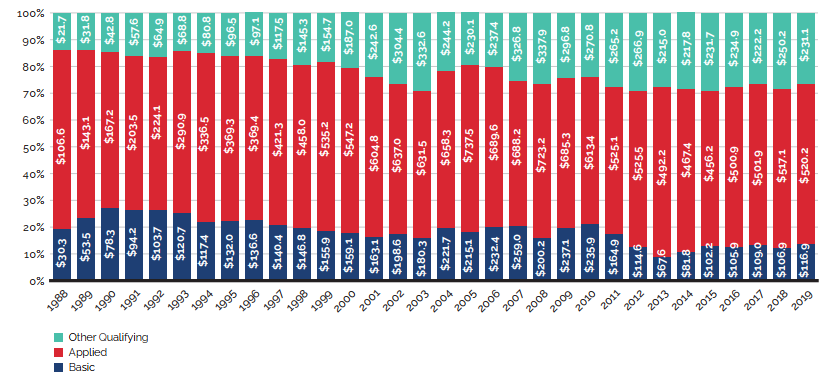

R&D-to-sales ratios decreased in 2019:

- 3.9% for all patentees, a slight decrease from 4.0% in 2018.

- 3.9% for Innovative Medicines Canada members, a decrease from 4.3% in 2018.

R&D expenditures:

- $893.2 million in total R&D expenditures reported by patentees, an increase of 0.1% over 2018.

- $652.6 million in R&D expenditures reported by Innovative Medicines Canada members, a decrease of 9.7% over 2018.

Letter to the Minister

January 15, 2021

The Honourable Patty Hajdu, P.C., M.P.

Minister of Health

House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 0A6

Dear Minister:

I have the pleasure to present to you, in accordance with sections 89 and 100 of the Patent Act, the Annual Report of the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board for the year ended

December 31, 2019.

Yours very truly,

Dr. Mitchell Levine

Chairperson

Chairperson’s Message

The Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) is an independent quasi-judicial body established by Parliament in 1987 under the Patent Act (the Act). The PMPRB’s mandate is to protect and inform Canadians by ensuring that the prices of patented medicines sold in Canada are not excessive and by reporting on pharmaceutical trends.

This past year was a busy and important one for the PMPRB. The organization focused on completing the final steps in a multiyear effort to strengthen and modernize our regulatory framework. To that end, in November 2019, we published a draft set of new pricing Guidelines, followed by the most intensive and far reaching public consultation in our more than three decades long history. In June 2020, following the Government’s announcement of its decision to postpone the coming into force of the amended Patented Medicines Regulations (Regulations) by six months, to January 1, 2021, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the PMPRB published a second draft set of new Guidelines that reflected our understanding of the feedback we received on the first draft. This was followed by another round of consultations which ended on August 4, 2020.

In terms of pharmaceutical trends, the most striking takeaway from this year’s Annual Report is the unprecedented 0.6% decrease in total spending on patented medicines. This can be explained by the fact that some key top-selling medicines stopped reporting to the PMPRB in 2018, including Remicade the highest selling prescription medicine in Canada. In 2018, medicines that previously reported to the PMPRB accounted for estimated sales of $3.3 billion, or 11.6% of all sales. This is a marked increase over the previous year and considerably more than a decade ago when medicines that formerly reported to the PMPRB accounted for $0.7 billion in sales, or 3.2% of all sales. Historically patented medicines have experienced a substantial erosion in market share upon loss of patent protection, however, recently that same effect has not been observed in a number of very high cost, biologic medicines that have come off patent. Given the significance of this phenomenon, the PMPRB has added new content to its Annual Report to track the impact of this trend as the market for these medicines matures.

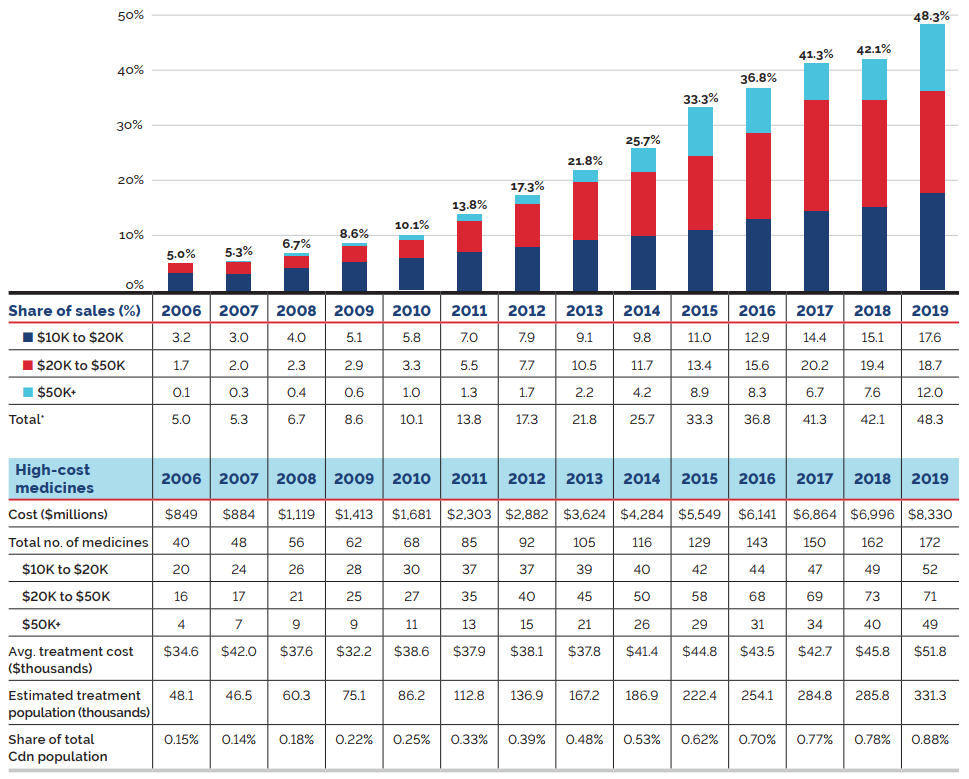

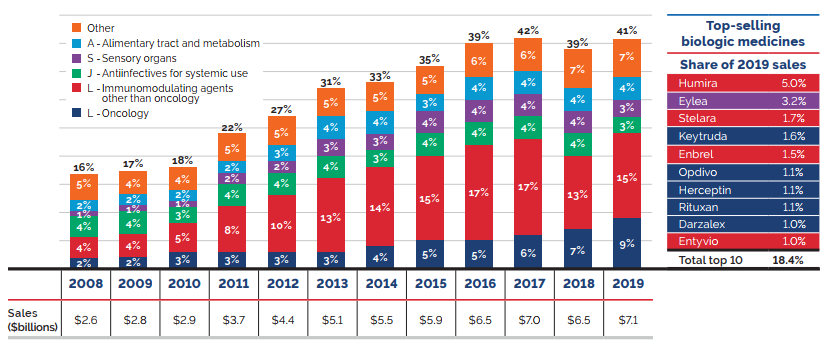

Our efforts to complete the regulatory modernization process took place in parallel to our usual and customary work under our reporting mandate of identifying and analyzing key pharmaceutical trends in Canada. In 2019-20, the PMPRB published seven analytical reports, three chartbooks and eight presentation posters under its National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System (NPDUIS) banner. The chief takeaway from all that work is the notable rise in the sales of higher-cost medicines Canada has experienced in recent years. Over the last five years, sales of patented medicines grew by an average of 4.5% per year, reaching $17.2 billion in 2019. The increasing use of higher-cost medicines remains the primary cost driver for Canadian public and private drug plans. Indeed, high-cost, biologic, oncology and targeted treatments now account for approximately half of all sales in patented medicines in Canada. This is a dramatic increase from the 10% of less than a decade ago. To put this trend in context, in 2009, only one of the top ten selling patented medicines in Canada had a treatment cost over $1000/year. In 2019, seven of the top ten selling patented medicines had annual treatment costs that exceeded $10,000/year.

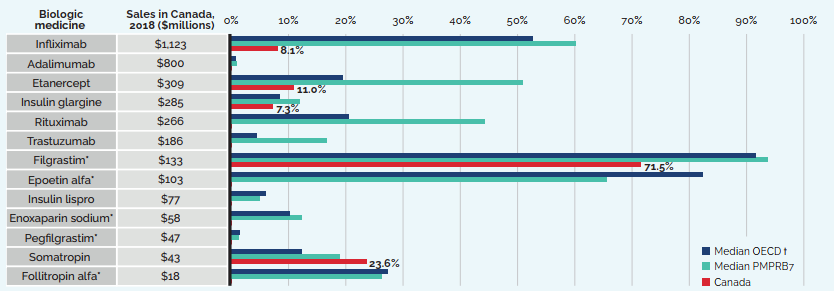

Canadian list prices of patented medicines are the fourth highest in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), still well behind the US but just marginally lower than Germany and Switzerland. Conversely, the R&D to sales ratio of pharmaceutical patentees in Canada continues its decades-long decline and now stands at 3.9%, its lowest level since the PMPRB first began reporting on pharmaceutical trends in the 1980s.

Once the PMPRB’s new Guidelines are finalized and the amended regulations come into force in January 2021, we look forward to working with all of our stakeholders on a comprehensive Guidelines Monitoring and Evaluation Plan (GMEP) that will enable us to assess the impact of the new regime and fine tune it in real time so that the PMPRB can continue to protect Canadians from excessive prices while avoiding any unintended consequences to other aspects of our health care system.

The PMPRB has been in reform mode for the better part of five years. Once the final Guidelines are published and the amended Regulations come into force, we look forward to a new and exciting chapter of applying our consumer protection powers responsibly and with the best interests of all Canadians at heart.

Dr. Mitchell Levine

Chairperson

About the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board: Acting in the Interest of Canadians

The Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) is an independent, quasi-judicial body established by Parliament in 1987 under the Patent Act (Act).

The PMPRB is a quasi-judicial administrative agency with a dual regulatory and reporting mandate. Through its regulatory mandate, it ensures that the prices of patented medicines sold in Canada are not excessive. The PMPRB also reports on trends in pharmaceutical sales and pricing for all medicines and on research and development (R&D) spending by patentees. In addition, at the request of the Minister of Health pursuant to Section 90 of the Act, the PMPRB conducts critical analyses of price, utilization, and cost trends for patented and non-patented prescription medicines under the National Drug Utilization Information System (NPDUIS) initiative. Its reporting mandate provides pharmaceutical payers and policy makers with information to make rational, evidence-based reimbursement and pricing decisions.

The PMPRB is part of the Health Portfolio, which includes Health Canada, the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency. The Health Portfolio supports the Minister of Health in maintaining and improving the health of Canadians.

Our Mission:

The PMPRB is a respected public agency that makes a unique and valued contribution to sustainable spending on pharmaceuticals in Canada by:

- Providing stakeholders with price, cost, and utilization information to help them make timely and knowledgeable pricing, purchasing, and reimbursement decisions; and

- Acting as an effective check on the prices of patented medicines through the responsible and efficient use of its consumer protection powers.

Protecting Consumers in a Complex Marketplace

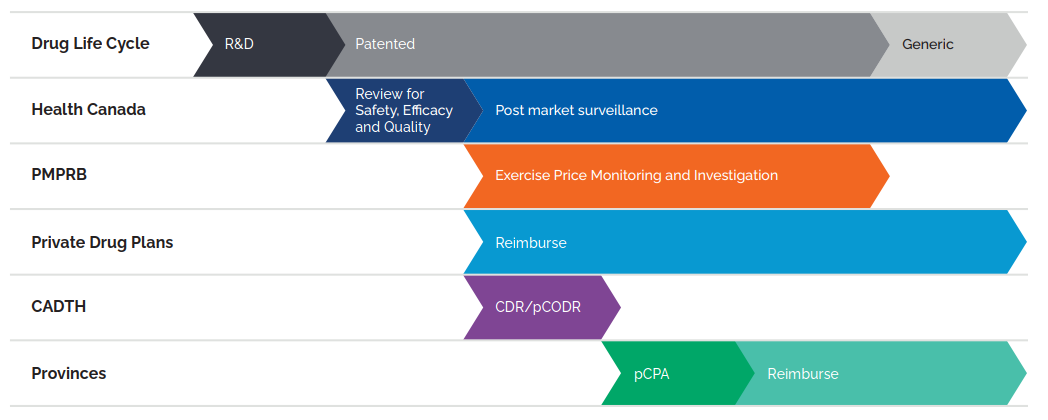

Figure description

This flowchart illustrates the role of Canadian regulators during the life cycle of a medicine through research and development, the patent period, and post-patent generic period. Health Canada reviews medicines for safety, efficacy, and quality at the start of the patent period and provides subsequent post-market surveillance. The PMPRB exercises price monitoring and investigation during the patent period, after Health Canada’s review. Private drug plans reimburse during and after the patent period, following Health Canada’s review. CADTH conducts the Common Drug Review and pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review processes after Health Canada’s review. For provinces and territories, the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance negotiations begin after CADTH reviews, and reimbursement is after these negotiations.

(CADTH) Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; (CDR) Common Drug Review; (pCODR) pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review; and (pCPA) pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance

Data source: PMPRB

Although part of the Health Portfolio, because of its quasi-judicial responsibilities, the PMPRB carries out its mandate at arm’s length from the Minister of Health, who is responsible for the sections of the Act pertaining to the PMPRB. The PMPRB also operates independently of other healthcare related bodies such as:

- Health Canada, which approves medicines for marketing in Canada based on their safety, efficacy and quality;

- federal, provincial and territorial (F/P/T) public drug plans, working collectively as the pCPA, which approve the listing of medicines on their respective formularies for reimbursement purposes; and

- the Common Drug Review and pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review, administered by the CADTH, which recommends which new medicines should qualify for reimbursement by the pCPA.

The PMPRB is composed of public servants (Staff) who are responsible for carrying out the organization’s day-to-day work, and Board Members, Governor-in-Council appointees who serve as hearing panel members in the event of a dispute between Staff and a patentee over the price of a patented medicine.

Jurisdiction

Regulatory

The PMPRB regulates the maximum ceiling price at which patentees (companies) may sell their products to wholesalers, hospitals, pharmacies and other large distributors. This price is sometimes also known as the “factory gate” (ex-factory) price. The PMPRB does not regulate the prices of non-patented medicines.

The PMPRB’s jurisdiction is not limited to medicines for which the patent is for the active ingredient or for the specific formulation(s) or uses the patentee sells the medicine for in Canada. Rather, its jurisdiction also covers medicines for which a patent “pertains” including patents for manufacturing processes, delivery systems or dosage forms, indications/use and any formulations.

The Act requires patentees (which include any parties who benefit from patents regardless of whether they are owners or licensees under those patents and regardless of whether they operate in the “brand” or “generic” sector of the market) to inform the PMPRB of their intention to sell a new patented medicine. Upon the sale of a new patented medicine, patentees are required to file price and sales information at introduction and, thereafter, until all patents pertaining have expired. Patentees are not required to obtain approval of the price to be able to market their medicines. However, the Act requires the PMPRB to ensure that the prices of patented medicines sold in Canada are not excessive.

Our Vision:

A sustainable pharmaceutical system where payers have the information they need to make smart reimbursement choices and Canadians can afford the patented medicines they need to live healthy and productive lives.

Staff reviews the prices that patentees charge for each individual strength and form of a patented medicine. If the price of a patented medicine appears to be potentially excessive, Staff will first try to reach a voluntary resolution by the patentee. If this fails, the Chairperson can decide that the matter should go to a hearing. At the hearing, a panel composed of Board members acts as a neutral arbiter between Staff and the patentee. If a panel finds that the price of a patented medicine is excessive, it can order the price be reduced to a non-excessive level. It can also order a patentee to make a monetary payment to the Government of Canada to offset the excess revenues earned and, in cases where the panel determines there has been a policy of excessive pricing, it can double the amount of the monetary payment.

Reporting

1,364 Patented medicines were reported to the PMPRB in 2019.

As required by the Act, the PMPRB reports annually to Parliament through the Minister of Health on its price review activities, the prices of patented medicines and price trends of all prescription medicines, and on the R&D expenditures reported by pharmaceutical patentees.

In addition, pursuant to an agreement by the F/P/T Ministers of Health in 2001, and at the request of the Minister of Health pursuant to section 90 of the Act, the PMPRB conducts critical analyses of price, utilization and cost trends for patented and non-patented prescription medicines under the National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System (NPDUIS). The PMPRB publishes the results of NPDUIS analyses in the form of research papers, posters, presentations and briefs. This program provides F/P/T governments and other interested stakeholders with a centralized, objective and credible source of information on pharmaceutical trends.

Among other initiatives under its reporting mandate, the PMPRB also hosts various forums, such as webinars, research forums and information sessions, with academics and policy experts to discuss and disseminate research on emerging areas for study on pharmaceutical trends in Canada and internationally.

Communications and Outreach

The PMPRB takes a proactive and plain-language approach to its external communication activities. This includes targeted social media campaigns and more conventional (e.g., email and telephone) engagement with domestic, international and specialized news media. The PMPRB is actively pursuing additional opportunities to leverage new and emerging media to communicate with Canadians and its stakeholders.

The PMPRB recognizes the importance of openness and transparency as we continue to work on modernizing the way we carry out our mandate. We communicate regularly, through various channels, about our progress, including projected timelines, and key milestones. Engagement with stakeholders will remain a central part of our multi-faceted communications approach. Reporting on our progress helps ensure we remain focused on delivering results.

Governance

The Board consists of not more than five members who serve on a part-time basis. Board members, including a Chairperson and a Vice-Chairperson, are appointed by the Governor-in-Council. The Chairperson, designated under the Act as the Chief Executive Officer of the PMPRB, has the authority and responsibility to supervise and direct its work. By law, the Vice-Chairperson exercises all the powers and functions of the Chairperson when the Chairperson is absent or incapacitated, or when the office of the Chairperson is vacant.

The members of the Board, including the Chairperson, are collectively responsible for implementing the applicable provisions of the Act. Together, they establish the guidelines, rules, by-laws and other policies of the PMPRB provided for by the Act (section 96) and consult, as necessary, with stakeholders including provincial and territorial Ministers of Health, representatives of consumer groups, the pharmaceutical industry and others.

Members of the Board

Chairperson

Mitchell Levine,

BSc, MSc, MD, FRCPC, FISPE, FACP

Dr. Mitchell Levine was appointed Chairperson of the Board on February 13, 2018.

Dr. Levine is a professor in both the Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence and Impact and in the Department of Medicine, Division of Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. He is also an Assistant Dean in the Faculty of Health Sciences and a faculty member of the Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis at McMaster.

Dr. Levine received his medical degree from the University of Calgary in 1979, followed by postgraduate medical training in Internal Medicine (FRCPC) and in Clinical Pharmacology at the University of Toronto (1981–1987). He received an MSc degree in Clinical Epidemiology from McMaster University in 1988.

Prior to his appointment to the Board, Dr. Levine was a member of the PMPRB’s Human Drug Advisory Panel. He currently acts on an ad hoc basis as a clinical pharmacology consultant to the Ontario Ministry of Health and Ministry of Long-Term Care. In addition, he is a Deputy Editor of the ACP Journal Club: Evidence-Based Medicine.

This is Dr. Levine’s second term as a Board member. He was initially appointed as its Vice-Chairperson in 2011.

Vice-Chairperson

Mélanie Bourassa Forcier

LLB., LL.L, MSc, LL.M., DCL

Mélanie Bourassa Forcier was appointed Vice-Chairperson of the Board on June 19, 2019.

Ms. Bourassa Forcier is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Law at the Université de Sherbrooke. She directs the Law and Health Policy, and Law and Life Sciences programs. She has expertise in the regulation, marketing and reimbursement of new medical technologies.

Professor Bourassa Forcier has published numerous books and articles on the subject of pharmaceutical regulation and health law. She holds a Ph.D. in Pharmaceutical Patent Law from McGill University, an MSc in International Health Policy from the London School of Economics and Political Science, and an LL.L. from the University of Ottawa.

Members

Carolyn Kobernick,

B.C.L., LL.B.

Carolyn Kobernick was appointed Member of the Board on June 13, 2014.

Ms. Kobernick is a lawyer and former public servant. Prior to her retirement in 2013, Ms. Kobernick was Assistant Deputy Minister of Public Law for the Department of Justice. As principal counsel to the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada, Ms. Kobernick was instrumental in the development and delivery of policy for the Public Law sector. In addition to identifying key strategic, legal and operational matters, she tackled cross-cutting national issues as the liaison between the Department of Justice and other government organizations.

Ms. Kobernick joined the Department of Justice in 1980, where she practiced litigation and tax law at the Toronto Regional office. In 1991, she was appointed Senior General Counsel, Deputy Head, Business and Regulatory Law Portfolio, after working for over a decade in the legal services unit of the Correctional Service of Canada. In her role as Senior General Counsel, Ms. Kobernick was involved in complex federal policy and operational issues, including the Alaska Pipeline and Mackenzie Valley Pipeline files and the Sponsorship file.

During her career with the public service, Ms. Kobernick actively participated in many high- profile initiatives. She was Chair of the National Legal Advisory Committee and Departmental Champion for Aboriginal People and Gender Equity. She also served as the Senior Department of Justice official at the Domestic Affairs Cabinet Committee, and was appointed Senior Legal Advisor to the Government of Canada for the 2004 Gomery Inquiry.

Ms. Kobernick holds a B.C.L. and LL.B. from McGill University and is a member of the bar of Ontario. In 2012 she obtained a Certificate in Adjudication for Administrative Agencies, Boards and Tribunals from the Osgoode Hall Law School and the Society of Ontario Adjudicators and Regulators.

Dr. Ingrid Sketris,

BSc (Pharm), PharmD, MPA(HSA), Clinical Toxicology Residency

Dr. Ingrid Sketris was appointed Member of the Board on June 29, 2018.

Dr. Sketris is a licensed pharmacist and a professor at the College of Pharmacy, Dalhousie University, with cross appointments to Medicine and Health Administration.

Dr. Sketris received her Doctor of Pharmacy in 1979 from the University of Minnesota, followed by her residency in Clinical Toxicology at the University of Tennessee Centre for the Health Sciences. She also received a Master of Public Administration/Health Services Administration from Dalhousie University.

She is a leader in pharmacy, and has served as President of the Association of Faculties of Pharmacy of Canada and as a board member of the Canadian Council for Accreditation of Pharmacy Programs.

Dr. Sketris is a Fellow of the Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists, the American College of Clinical Pharmacy and the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences. She was previously elected to the US National Academies of Practice.

Matthew Herder,

B.Sc. (hons), LL.B., LL.M., J.S.M.

Matthew Herder was appointed Member of the Board on June 29, 2018.

Mr. Herder is the Director of the Health Law Institute at Dalhousie University as well as an Associate Professor in the Department of Pharmacology in the Faculty of Medicine, with a cross-appointment to the Schulich School of Law.

Mr. Herder’s research focuses on biomedical innovation policy, with a particular emphasis on intellectual property rights and the regulation of biopharmaceutical interventions. His work is often interdisciplinary and policy-oriented, and he has received grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Royal Society of Canada, in addition to appearing as an expert witness before several Parliamentary committees on pharmaceutical regulation and policy.

Prior to arriving at Dalhousie, Mr. Herder was the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation Legal Research Fellow at New York University’s School of Law. He was a Law Clerk at the Federal Court of Canada and was admitted to the Law Society of Upper Canada. Mr. Herder holds a Master of the Science of Law degree from Stanford Law School as well as two law degrees from Dalhousie University.

Organizational Structure and Staff

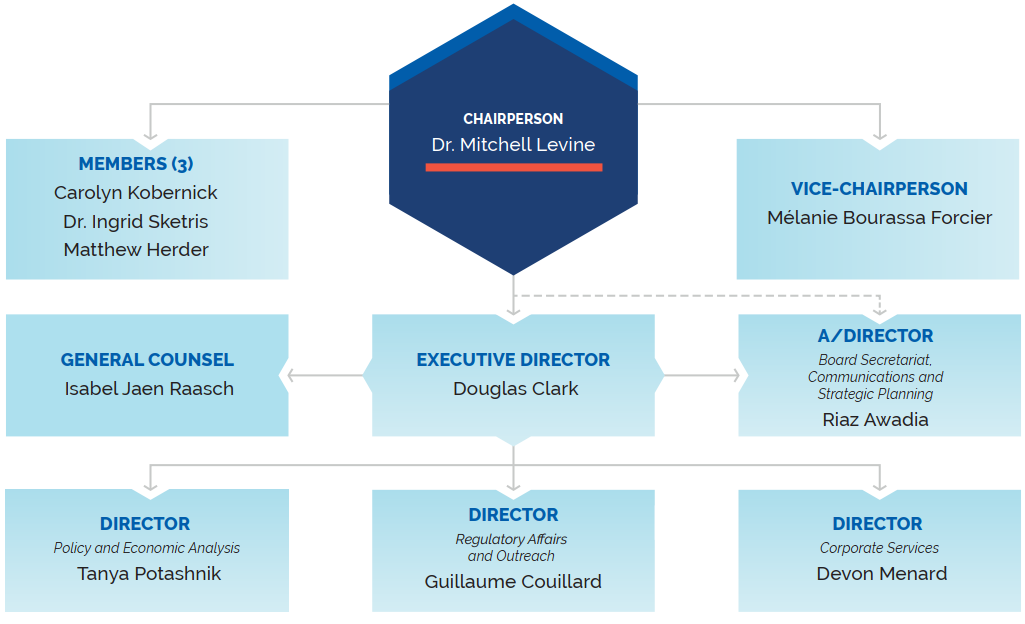

PMPRB Organizational Chart

Figure description

This organizational chart illustrates the high-level reporting structure within the PMPRB and lists the current Board and Senior Staff members. Board: Chairperson— Dr. Mitchell Levine; Vice-Chairperson— Mélanie Bourassa Forcier; Members— Carolyn Kobernick, Ingrid Sketris, Matthew Herder. Senior Staff: Executive Director— Douglas Clark; General Counsel— Isabel Jaen Raasch; A/Director Board Secretariat, Communications and Strategic Planning— Riaz Awadia; Director Policy and Economic Analysis— Tanya Potashnik; Director Regulatory Affairs and Outreach— Guillaume Couillard; Director Corporate Services— Devon Menard.

Executive Director

The Executive Director is responsible for advising the Board and for the leadership and management of Staff.

Regulatory Affairs and Outreach

The Regulatory Affairs and Outreach Branch reviews the prices of patented medicines sold in Canada to ensure they are not excessive; ensures that patentees are fulfilling their filing obligations; encourages patentees to comply voluntarily with the PMPRB’s Guidelines; implements related compliance policies; and investigates complaints into the prices of patented medicines.

Policy and Economic Analysis

The Policy and Economic Analysis Branch develops policy and strategic advice; leads stakeholder consultations, and makes recommendations on possible amendments to the PMPRB’s Guidelines; conducts research and analysis on the prices of medicines, pharmaceutical market developments, and R&D trends; and publishes studies aimed at providing F/P/T governments and other interested stakeholders with centralized, objective, and credible information in support of evidence based policy.

Corporate Services

The Corporate Services Branch provides advice and services in relation to human resources management; facilities; procurement; health, safety and security; information technology; and information management. It is also responsible for financial planning and reporting, accounting operations, audit and evaluation, and liaising with federal central agencies on these topics.

Board Secretariat, Communications and Strategic Planning

The Board Secretariat, Communications and Strategic Planning Branch develops and manages the PMPRB’s communications, media relations, and public enquiries; manages the Board’s meeting and hearing processes, including the official record of proceedings; and coordinates activities pursuant to the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act. It is also responsible for strategic planning and reporting.

General Counsel

The General Counsel advises the PMPRB on legal matters and leads the legal team representing Staff in proceedings before the Board.

Budget

In 2019-20, the PMPRB had a budget of $16.6 million and an approved staff level of 82 full-time equivalent employees.

Table 1. Budget and Staffing

| 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Budget* | $14,871,872 |

$16,612,511 |

$17,804,400 |

| Salaries and employee benefits | $8,373,171 |

$9,636,550 |

$10,054,721 |

| Operating | $3,079,220 |

$2,699,395 |

$2,491,893 |

| Special Purpose Allotment** | $3,419,481 |

$4,276,566 |

$5,257,786 |

| Full Time Employees (FTEs) | 72 |

82 |

87 |

* Budget amounts are based on the Main Estimates

** The Special Purpose Allotment is reserved strictly for external costs of public hearings (legal counsel, expert witnesses, etc.). Unspent funds are returned to the Consolidated Revenue Fund.

Regulating Prices of Patented Medicines: Continued Vigilance Necessary

Medical advancements have introduced many innovative new medicines to the Canadian marketplace to improve existing treatments and to treat conditions that previously had no pharmaceutical therapy. However, many of these new medicines come at a very high cost. Since 1987, pharmaceutical costs in Canada have grown at an average annual rate of 7.2%Footnote 1, outpacing all other health care costs and growing at well over 3 times the pace of inflation.

At 15.7% of total health care spending, pharmaceuticals now rank ahead of spending on physicians.Footnote 2 About 1 in 5 Canadians reports having no prescription medicine coverage and many more are under-insured or face high deductibles or co-pays. Almost 1 in 10 Canadians have had to forego filling a prescription medicine in the past year for reasons related to cost.Footnote 3

The PMPRB protects the interests of Canadian consumers by ensuring that the prices of patented medicines sold in Canada are not excessive. It does this by reviewing the prices that patentees charge for each individual patented medicine and by ensuring that patentees reduce their prices and pay back excess revenues where appropriate.

Reporting Requirements

By law, patentees must file information about the sale of their medicines in Canada. The Act, along with the Patented Medicines Regulations(Regulations) set out the information required and Staff reviews pricing information on an ongoing basis until all relevant patents have expired.

There are several factors used for determining whether the price of a medicine is excessive, as outlined in section 85 of the Act.

The Compendium of Policies, Guidelines and Procedures (Guidelines) details price tests and triage mechanisms used by Staff when it reviews and investigates the prices of patented medicines. The Guidelines are not binding and were developed in consultation with stakeholders, including the provincial and territorial Ministers of Health, consumer groups, and the pharmaceutical industry. When an investigation suggests that the price of a patented medicine may be excessive, the patentee is offered the opportunity to voluntarily lower its price and/or refund its excess revenues through a Voluntary Compliance Undertaking (VCU). If the patentee chooses not to submit a VCU, the Chairperson hold a hearing on the matter if he feels it is in the public interest. After hearing all the evidence, if the Board finds that a price is in fact excessive, it can issue an order requiring a patentee to reduce that price and/or refund excess revenues. Copies of the Act, the Regulations and the Guidelines are available on the PMPRB’s website.

Failure to Report

The PMPRB relies on patentees’ full and timely disclosure of any and all patented medicines being sold in Canada to which a patent pertains. In 2019, 10 medicines were reported to the PMPRB for the first time despite being patented and sold prior to 2019. (See Table 2, Failure to Report the Sale of Patented Medicines)

Failure to File Price and Sales Data (Form 2)

Failure to file refers to the complete or partial failure of a patentee to file the information required by the Act and the Regulations to the PMPRB. There were no Board Orders issued for failure to file in 2019

Table 2. Failure to Report the Sale of Patented Medicines

| Patentee | Brand name | Medicinal ingredient | Year medicine reported to the PMPRB as under PMPRB’s jurisdiction | Year medicine reported to the PMPRB with subsequent patent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Knight Therapeutics Inc. |

Nerlynx |

neratinib |

2017 |

- |

Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation |

Radicut |

edaravone |

2018 |

- |

Bausch Health, Canada Inc |

Prolensa |

bromfenac |

2015 |

- |

Chiesi USA Inc. |

Cardene IV (4 DINs) |

nicardipine hydrocholride |

2012 |

- |

Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc |

Ilmya |

tildrakizumab |

2018 |

- |

Ipsen Biopharmaceuticals Canada Inc. |

Increlex |

mecasermin |

2016 |

- |

Novo Nordisk Canada Inc. |

Xultophy |

insulin degludec/liraglutide |

2018 |

- |

Shire Pharma Canada Inc. |

Obizur |

antihemophilic factor (recombinant), porcine Sequence |

2017 |

- |

Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc. |

Odomzo |

sonidegib |

2012 |

- |

Indivior Canada Ltd |

Suboxone (3 DINs) |

buprenorphine/naloxone |

2019 |

- |

Data source: PMPRB

Scientific Review

Human Drug Advisory Panel

A scientific evaluation is done on all new patented medicines as part of the price review process. The PMPRB established the Human Drug Advisory Panel (HDAP) to provide advice to Staff. The HDAP conducts an evaluation when a patentee claims the new medicine provides a therapeutic improvement. The HDAP members review and evaluate the appropriate scientific information available, including any submission by a patentee about the proposed level of therapeutic improvement, the selection of comparator medicines, and comparable dosage regimens.

The HDAP evaluates the therapeutic benefit of new patented medicines according to the following definitions:

- Breakthrough: A medicine that is the first one sold in Canada to effectively treat a particular illness or effectively address a particular indication.

- Substantial Improvement: A medicine that, relative to other medicines sold in Canada provides substantial improvement in therapeutic effects.

- Moderate Improvement: A medicine that, relative to other medicines sold in Canada provides moderate improvement in therapeutic effects.

- Slight or No Improvement: A medicine that, relative to other medicines sold in Canada, provides slight or no improvement in therapeutic effects.

* Assessment as of March 31, 2020

Data source: PMPRB

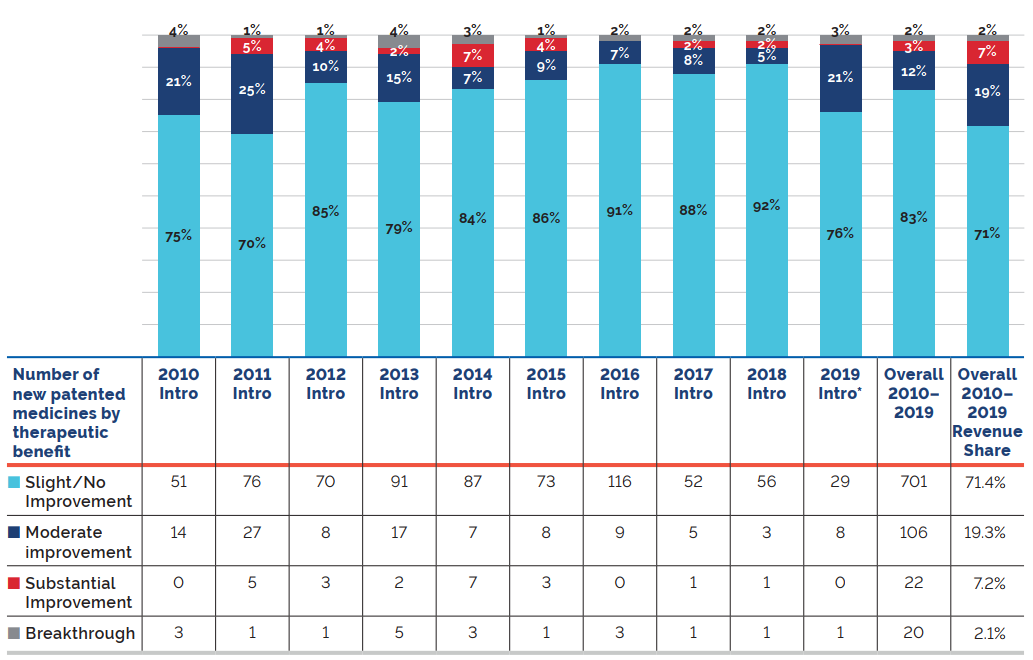

Figure description

This bar graph depicts the breakdown in percentages of new patented medicines by therapeutic benefit over existing medicines in the year of introduction for the period 2010 to 2019.

|

Slight/No improvement |

Moderate improvement |

Substantial improvement |

Breakthrough |

Intro 2010 |

75% |

21% |

0% |

4% |

Intro 2011 |

70% |

25% |

5% |

1% |

Intro 2012 |

85% |

10% |

4% |

1% |

Intro 2013 |

79% |

15% |

2% |

4% |

Intro 2014 |

84% |

7% |

7% |

3% |

Intro 2015 |

86% |

9% |

4% |

1% |

Intro 2016 |

91% |

7% |

0% |

2% |

Intro 2017 |

88% |

8% |

2% |

2% |

Intro 2018 |

92% |

5% |

2% |

2% |

Intro 2019 |

71% |

19% |

7% |

2% |

The therapeutic benefit of all new patented medicines introduced from 2010 to 2019 is depicted by the Overall 2010-2019 bar. From 2010-2019; 83% new patented medicines were slight or no improvement, 12% were moderate improvement, 3% were substantial improvement, and 2% were breakthrough. The Overall 2010-2019 Revenue Share depicts the percentage of sales related to each level of therapeutic benefit: 71% of sales were medicines of little or no improvement, 19% were medicines of moderate improvement, 7% were medicines of substantial improvement, and 2% were breakthroughs.

Figure 1 illustrates the breakdown of new patented medicines in the year of introduction by therapeutic benefit for 2010 to 2019. The largest percentage of patented medicines (83.0%) introduced since 2010 were categorized as “Slight or No Improvement” in therapeutic benefit over existing therapies.Footnote 4

The “Overall 2010-2019” bar represents the therapeutic benefit breakdown for all new patented medicines introduced from 2010 to 2019. The “Overall 2010-2019 Revenue Share” bar illustrates the revenue share by therapeutic benefit for all new patented medicines introduced from 2010 to 2019.

Our motto

Protect, Empower, Adapt.

Price Review

The PMPRB reviews the average price of each strength of each individual dosage form of each patented medicine. In most cases, this unit is consistent with the Drug Identification Number(s) (DIN), (DINs) assigned by Health Canada at the time the medicine is approved for sale in Canada.

New Patented Medicines Reported to the PMPRB in 2019

For the purpose of this report, a new patented medicine in 2019 is defined as any patented medicine or new dosage form or strength of a patented medicine first sold in Canada, or previously sold but first patented, between December 1, 2018, and November 30, 2019.

There were 81 new patented medicines for human use reported as sold in 2019. Some are one or more strengths of a new active substance and others are new presentations of existing medicines. Of these 81 new patented medicines, 2 (2.5%) were being sold in Canada prior to the issuance of the Canadian patent that brought them under the PMPRB’s jurisdiction. Table 3 shows the year of first sale for these medicines.

Table 3. Number of New Patented Medicines for Human Use in 2019 by Year First Sold

| Year First Sold | Number of Medicines |

|---|---|

| 2017 | 1 |

| 2018 | 1 |

| 2019 | 79 |

| Total | 81 |

Data source: PMPRB

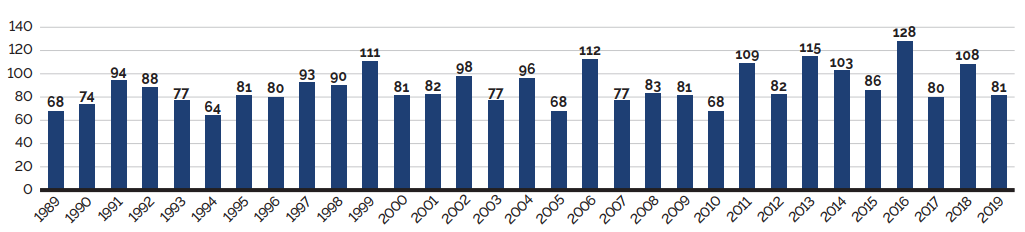

The list of New Patented Medicines Reported to PMPRB is available on the PMPRB’s website under “Regulating Prices”. This list includes information on the status of the review (i.e., whether the medicine is under review, within the Guidelines, under investigation, or subject to a VCU or Notice of Hearing). Figure 2 illustrates the number of new patented medicines for human use reported to the PMPRB from 1989 to 2019.

Data source: PMPRB

Figure description

This bar graph depicts the number of new patented medicines for human use reported to the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board by year. In 1989, 68 patented medicines for human use were reported to the PMPRB.

In 1990: 74; 1991: 94; 1992: 88; 1993: 77; 1994: 64; 1995: 81; 1996: 80; 1997: 93; 1998: 90; 1999: 111; 2000: 81; 2001: 82; 2002: 98; 2003: 77; 2004: 96; 2005: 68; 2006: 112; 2007: 77; 2008: 83; 2009: 81; 2010: 68; 2011: 109; 2012: 82; 2013: 115; 2014: 103; 2015: 86; 2016: 128; 2017: 80; 2018: 108; 2019: 81.

Of the 81 new patented medicines, the prices of 38 had been reviewed as of March 31, 2020:

- 29 were found to be within the thresholds set out in the Guidelines;

- 3 were at a level that appeared to exceed the thresholds set out in the Guidelines by an amount that did not trigger the investigation criteria; and

- 6 were at levels that appeared to exceed the thresholds set out in the Guidelines and resulted in investigations being commenced.

For a complete list of the 81 new patented medicines and their price review status, see Appendix 2.

Price Review of Existing Patented Medicines for Human Use in 2019

For the purpose of this report, existing patented medicines include all patented medicines first sold and reported to the PMPRB prior to December 1, 2018.

At the time of this report, there were 1,283 existing patented medicines:

- 919 were priced within the thresholds set out in the Guidelines;

- 202 had prices that appeared to exceed the thresholds set out in the Guidelines by an amount that did not trigger the investigation criteria;

- 122 were the subject of investigations;

- 17 were under review;

- 20 were the subject of a Voluntary Compliance Undertaking;

- 2 are the subject of a hearing; and

- 1 is subject to a price reduction and excess revenue payment order (currently partially stayed).

Table 4 provides a summary of the status of the price review of the new and existing patented medicines for human use in 2019.

Table 4. Patented Medicines for Human Use Sold in 2019—Status of Price Review as of March 31, 2020

| New medicines introduced in 2019 | Existing medicines | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 81 | 1,283 | 1,364 |

| Within Guidelines Thresholds | 29 | 919 | 948 |

| Under Review | 43 | 17 | 60 |

| Does Not Trigger Investigation | 3 | 202 | 205 |

| Under Investigation | 6 | 122 | 128 |

| Subject to Voluntary Compliance Undertaking | 0 | 19 | 191 |

| Price Hearing | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Subject to Price Reduction Order (Stayed) | 0 | 1 | 1 |

1The terms and conditions of previous years VCUs that have carried over into 2018 are not captured in this count.

Data source: PMPRB

Update From the 2018 Annual Report

- Reviews of all the medicines for human use that were reported as Under Review in the 2018 Annual Report have been completed.

- 105 of the 128 investigations reported in the 2018 Annual Report resulted in one of the following:

- the closure of the investigation where it was concluded the price was within the thresholds set out in the Guidelines;

- a VCU by the patentee to reduce the price and offset excess revenues through a payment and/or a reduction in the price of another patented medicine (see Voluntary Compliance Undertakings); or

- a public hearing to determine whether the price was excessive, including any remedial Order determined by the Board (see Hearings).

Patented Over-the-Counter Medicines and Patented Medicines For Veterinary Use

Staff only reviews the prices of patented over-the-counter medicines, patented generic medicines and patented veterinary medicines when a complaint of excessive pricing has been received. No such complaints were received in 2019.

Voluntary Compliance Undertakings and Hearings

Voluntary Compliance Undertakings

A VCU is a written undertaking by a patentee to adjust its price to conform to the Board’s Guidelines. The Guidelines set out procedures for patentees to submit a VCU when, following an investigation by Staff, the price of a patented medicine sold in Canada appears to have exceeded the thresholds set out in the Guidelines. A VCU represents a promise by a patentee geared towards a satisfactory resolution of an investigation initiated by Staff under the Guidelines. A VCU takes into account the specific facts and underlying context of a particular case. VCUs are not intended to have precedential value.

In 2019, twelve VCUs were approved by the Chairperson. In addition to price reductions for certain medicines, excess revenues totaling $3,492,454.93 were offset by way of payments to the Government of Canada.

As of May 31, 2020, the Chairperson approved the closure of an investigation after the receipt of an additional VCU totalling $75.8 thousand bringing the total payments to the Government of Canada for 2019 up to May 31, 2020 to $3.6 million.

Table 5. Voluntary Compliance Undertakings in 2019 up to May 31, 2020

| Patented medicine brand name | Therapeutic use | Patentee | Date of approval | Offset of excessive revenues | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price reduction | Payment to the government | ||||

VCUs in 2019 |

|||||

Triptorelin (sold under trade name Trelstar) |

Palliative treatment of hormone dependent advanced carcinoma of the prostate gland (stage D2) |

Paladin Labs Inc. |

January |

✓ |

$157,159.70 |

Belimumab (sold under trade name Benlysta) |

An adjunct to standard therapy for reducing disease activity in adult patients with active, autoantibody-positive, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) |

GlaxoSmithKline Inc. |

March |

✓ |

|

Dupilumab (sold under trade name Dupixent) |

Treatment of adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable. |

Sanofi-aventis Canada Inc. |

April |

✓ |

$1,654,520.73 |

Alirocumab (sold under trade name Praluent) |

An adjunct to diet and maximally tolerated statin therapy for the treatment of adults with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH) or clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD), who require additional lowering of low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). |

Sanofi-aventis Canada Inc. |

April |

|

$426,955.62 |

Darunavir/cobicistat/emtricitabine |

An antiretroviral agent indicated as a complete regimen for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in adults and adolescents (aged 12 years and older with a body weight at least 40 kilograms) and with no known mutations associated with resistance to the individual components of Symtuza. |

Janssen Inc. |

April |

✓ |

$4,590.73 |

Ciproflaxacin/ |

For the treatment of infections caused by most strains of gram-positive and gram-negative microorganisms in the specific conditions including in part acute otitis media with otorrhea and acute otitis externa. |

Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada Inc. |

June |

✓ |

$141,159.41 |

Moxifloxacin hydrochloride (sold under trade name Vigamox) |

For the treatment of patients one year of age and older with bacterial conjunctivitis caused by susceptible aerobic gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial strains. |

Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada Inc. |

June |

✓ |

|

Olopatadine hydrochloride (sold under trade name Pataday) |

For the treatment of ocular itching associated with seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. |

Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada Inc. |

June |

✓ |

$72,691.53 |

Crizotinib (sold under trade name Xalkori) |

A monotherapy for use in patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive locally advanced (not amenable to curative therapy) or metastic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) |

Pfizer Canada ULC |

June |

✓ |

$54,955.56 |

Sertraline hydrochloride (sold under trade name Zoloft) |

For the symptomatic relief of depressive illness, for symptomatic relief of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, and for the symptomatic relief of obsessive-complusive disorder (OCD) |

Upjohn Canada ULC |

June |

✓ |

$754,647.71 |

Desmopressin acetate (sold under trade name Nocdurna) |

An antidiuretic for the treatment of nocturia in adults with four or less nocturnal voids |

Ferring Inc. |

July |

✓ |

$94,977.75 |

Trifluridine/ |

An antineoplastic agent indicated for the treatment of adult patients with metastic colorectal cancer who have been previously treated with, or are not candidates for, available therapies including flurorpyrimidine-, oxaliplatin- and irnotecan-based chemotherapies, anti-VEGF biological agents, and if RAS wild-type, anti-EGFR agents |

Taiho Pharma Canada Inc. |

October |

✓ |

|

Pegademase bovine (sold under trade name Adagen) |

Enzyme replacement therapy for adenosine deaminase (ADA) deficiency in patients with sever combined immunodeficiency disease (SCID) who are not suitable candidates for or who have failed bone marrow transplanation |

Leadiant Biosciences, Inc. |

October |

|

$130,796.19 |

Total as of December 31, 2019 |

$3,492,454.93 |

||||

VCUs in 2020 as of May 31, 2020 |

|||||

Ixekizumab (sold under trade name Taltz) |

For the treatment of adult patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy, and for the treatment of adult patients with active psoriasis who have responded inadequately to, or are intolerant to one or more disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. |

Eli Lilly Canada Inc. |

January |

|

$75,844.49 |

Total as of May 31, 2020 |

$3,568,299.42 |

||||

Hearings

The PMPRB holds hearings into two types of matters:

- excessive pricing; and

- failure to file–jurisdiction.

Excessive Pricing

In the event that the price of a patented medicine appears to be excessive, the Chairperson can commence a public hearing. If the Hearing Panel finds the price is excessive, it can issue an order to reduce the price of the patented medicine in question (or of another patented medicine of the patentee) and/or to offset revenues received as a result of the excessive price. Judicial review of Board decisions can be sought in the Federal Court of Canada.

In January 2019, the PMPRB announced it would hold a public hearing in the matter of the price of the patented medicine cysteamine bitartrate sold under the trade name Procysbi by Horizon Therapeutics Canada. The purpose of this hearing is to determine whether the medicine has been or is being sold in any market in Canada at a price that, in the Board’s opinion, is or was excessive: and, if so, what order, if any, should be made to remedy the excessive pricing. The matter is ongoing.

Failure to File–Jurisdiction

When Staff believes a patentee has failed or refused to provide the PMPRB the pricing and sales information required by law, Staff will recommend that the Chairperson call a public hearing to determine whether the patentee has, in fact, breached the reporting requirements of the Act and Regulations. If the Hearing Panel finds, as the result of a public hearing, that the patentee has failed to report the required information, the Hearing Panel can order the patentee to file the required pricing and sales information.

There were no failure to file hearings as of March 31, 2020.

On May 7, 2020, the Board issued its decision on re-determination on its decision dated December 19, 2016 whereby the Board originally found that Canadian Patent No. 2,478,237 pertains to the patented medicine eculizumab sold under the trade name Differin and ordered Galderma to file the required information for the period between January 1, 2010 and March 14, 2016. The Board’s decision on redetermination again ordered Galderma to file the required information for the period between January 1, 2010 and March 14, 2016. On August 11, 2020, Galderma Canada Inc. filed an application for judicial review of the Board’s May 7, 2020 decision on redetermination (T-906-20).

Summary

Excess revenues totaling $3,568,299.42 were offset by payments to the Government of Canada through VCUs and Board Orders in 2019 and up to May 31, 2020.

Since 1993, 154 VCUs have been approved and 30 public hearings related to allegations of failure to file and/or excessive pricing have been initiated. These measures resulted in price reductions and the offset of excess revenues by additional price reductions and/or payments to the Government of Canada. Over $210 million has been collected through VCUs, settlements and Board Orders through payments to the Government of Canada and/or to customers such as hospitals and clinics.

Matters Before the Federal Court, Federal Court of Appeal and Supreme Court of Canada or Other Courts

On October 20, 2017, Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc. filed an application for judicial review of the Board’s decision dated September 20, 2017 in respect of its finding that the patented medicine eculizumab sold under the trade name Soliris was being sold at an excessive price in Canada and ordering Alexion to lower its price (currently stayed) and make an excess revenue payment of $4,245,329.60. The Board’s decision was found to be reasonable by the Federal Court via a decision dated May 23, 2019. Alexion has appealed the Federal Court’s decision in the Federal Court of Appeal. This matter is currently pending.

On January 18, 2017, Galderma Canada Inc. filed an application for judicial review of the Board’s decision dated December 19, 2016. In that decision the Board found that Canadian Patent No. 2,478,237 pertains to the patented medicine adapalene sold under the trade name Differin and ordered Galderma to file the required information for the period between January 1, 2010 and March 14, 2016. The Federal Court granted Galderma’s judicial review application on November 9, 2017 and quashed the Board’s decision. On November 21, 2017, the Attorney General appealed the Federal Court’s grant of the judicial review application. On June 28, 2019, the Federal Court of Appeal granted the appeal and issued its decision sending the matter back to the Board for redetermination. The Board’s decision on redetermination issued on May 7, 2020, again ordered Galderma to file the required information for the period between January 1, 2010 and March 14, 2016. On August 11, 2020, Galderma Canada Inc. filed an application for judicial review of the Board’s May 7, 2020 decision on redetermination (T-906-20). This matter is currently pending.

There are no PMPRB related matters before the Supreme Court of Canada.

Two challenges related to PMPRB legislation were commenced in 2019:

I.M.C. et al. v. Canada (Attorney General), T-1465-19: Innovative Medicines Canada and sixteen individual pharmaceutical companies brought an application in Federal Court to judicially review s. 4 (new factors), s. 6 and Schedule (new basket of countries) and ss. 3(4) (new net price calculation) of the 2019 Amendments to the Patented Medicines Regulations (coming into force in January, 2020) on the basis that they were ultra vires the regulation-making power contained in the Patent Act. The Federal Court issued its decision on June 29, 2020 and held that the amendments in s 4, s. 6 and the Schedule are intra vires the Patent Act, but that the amendment in ss. 3(4) is not. On September 10, 2020, I.M.C. and the individual pharmaceutical companies filed a Notice of Appeal with respect to the Federal Court decision. This matter is currently pending.

Merck et al. v Canada (Attorney General), No. 500-17-109270-192: six individual pharmaceutical companies brought an application for judicial review in Quebec Superior Court challenging the constitutionality of ss. 79-103 of the Patent Act. This matter is set to be heard by the Quebec Superior Court the week of September 28, 2020.

Table 6. Status of Board Proceedings in 2019 up to May 31, 2020

| Medicine | Indication/use | Patentee | Issuance of notice of hearing | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eculizumab (sold under trade name Soliris) | Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome |

Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc. | January 20, 2015 | Board Order: September 27, 2017 |

| Cysteamine bitartrate (sold under trade name Procysbi) |

Nephropathic cystinosis | Horizon Thearpeutics Canada | January 14, 2019 | Ongoing |

| Medicine | Indication/use | Patentee | Issuance of Notice of Hearing | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adapalene (sold under trade names Differin and Differin XP) |

Acne | Galderma Canada Inc. | (redetermination) | Board Order: May 7, 2020. Galderma to file the required information for the requested period. * Application for Judicial Review and prior litigation: see below. |

| Medicine | Indication/use | Patentee | Issuance of Notice of Hearing | Date of notice of hearing/status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Eculizumab (sold under trade name Soliris) |

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria |

Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc. |

Allegations of excessive pricing |

Application for Judicial Review. Court File T-1596-17 (Re. Board Panel’s decision of September 20, 2017): Decision issued May 23, 2019. Notice of Appeal (Federal Court of Appeal) filed on June 21, 2019. Court File A-237-19, Matter pending |

Adapalene (sold under trade names Differin and |

Acne |

Galderma Canada Inc. |

Failure to file (jurisdiction) |

Application for Judicial Review. Court File T-83-17 (Re. Board Panel’s decision of December 19, 2016): Decision issued November 9, 2017 quashing in part Board Panel’s decision. Notice of Appeal (Federal Court of Appeal) filed on November 21, 2017. Court File A-385-17. Decision issued on June 28, 2019. Matter sent for redetermination by the Board. Redetermination decision issued on May 7, 2020. Application for Judicial Review. Court File T-906-20 (Re. Board Panel’s Decision of May 7, 2020) filed on August 11, 2020. Matter pending. |

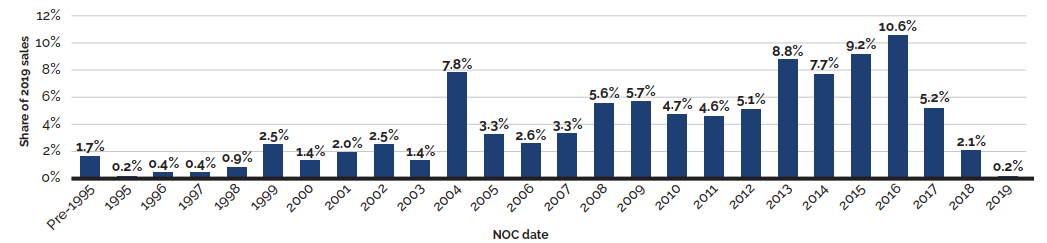

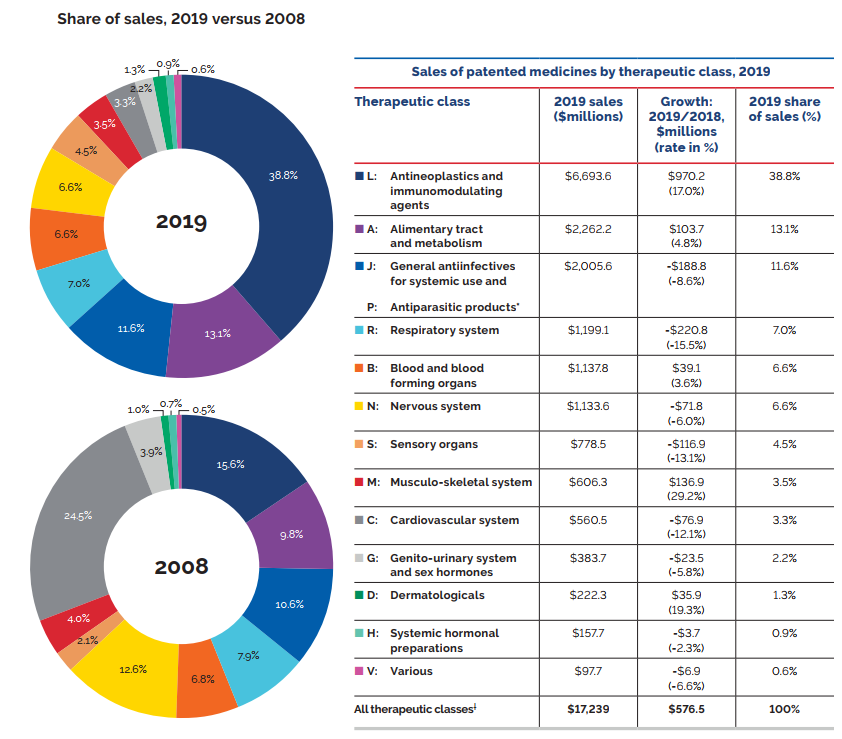

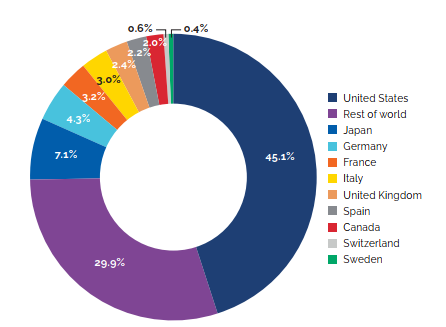

Key pharmaceutical trends: more expensive medicines continue to influence sales

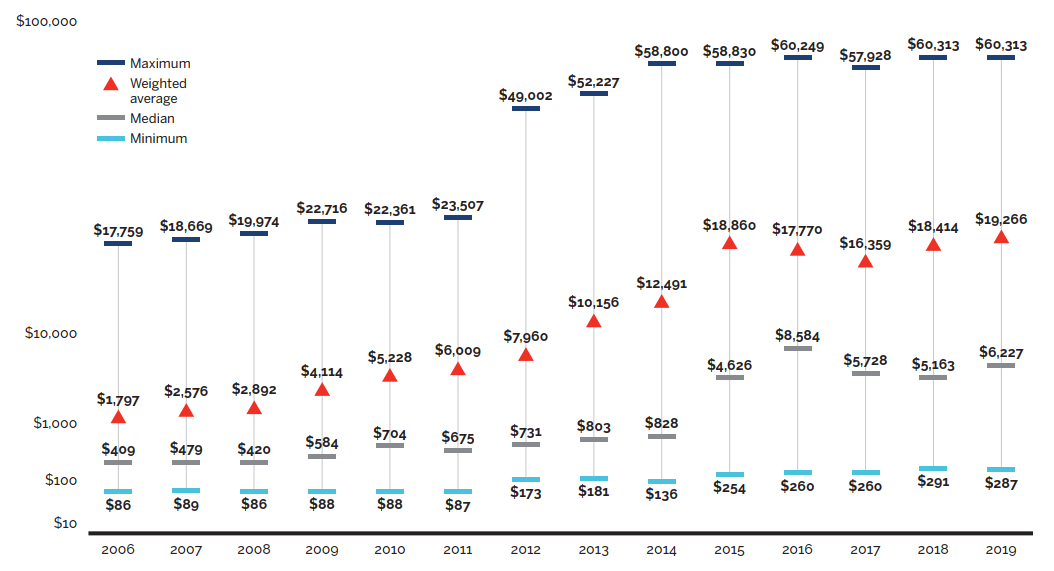

Overall spending on pharmaceuticals is influenced by many factors, including price, utilization, the entry of newer, more expensive medicines, and the loss of market exclusivity of older patented medicines. In 2019, there was a notable rise in the sales of higher-cost medicines, resulting in an overall increase in total spending of 3.5%. Canadian list prices of patented medicines remained among the highest in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), ranking fourth, well behind the US and just marginally lower than Germany and Switzerland.

The PMPRB is responsible for reporting on trends in pharmaceutical sales and pricing for all medicines and for reporting research and development spending by patentees.

Under the Regulations, patentees are required to submit detailed information on their sales of patented medicines, including quantities sold, gross and net prices, and net revenues. The PMPRB uses this information to analyze trends in the sales, prices,Footnote 5 and use of patented medicines.Footnote 6 This section provides key trends, including analyses of Canadian national, public, and private payer markets for all medicines. Note that any reference to sales in this section should be interpreted as sales revenues unless otherwise noted.

$17.2 billion sales in patented medicines in 2019

Sales of patented medicines have grown by an average of 4.5% per year over the last five years.

Disclaimers

- Although select statistics reported in the KEY PHARMACEUTICAL TRENDS section are based in part on data obtained under license from the IQVIA MIDAS® database and the IQVIA Private Pay Direct Drug Plan database, the statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions expressed in this Annual Report are exclusively those of the PMPRB and are not attributable to IQVIA.

- To provide a broader perspective on pharmaceutical trends in Canada, summaries of the results of NPDUIS analyses have been included as additional “Brief Insights” throughout the Pharmaceutical Trends section of the Annual Report. A variety of public and licensed data sources are used for NPDUIS analytical studies. Many of these sources do not differentiate between patented and non-patented generic medicines; in these instances, the general term “generic” is used to include both. NPDUIS is a research initiative that operates independently of the regulatory activities of the PMPRB.

Trends in Sales of Patented Medicines

Canadians spend much more on patented medicines today than they did a decade ago. Over the last five years, sales of these medicines grew by an average of 4.5% per year, reaching $17.2 billion in 2019. This section looks at the most important factors driving the change in sales revenues from 2018 to 2019 and compares them to trends from previous years.

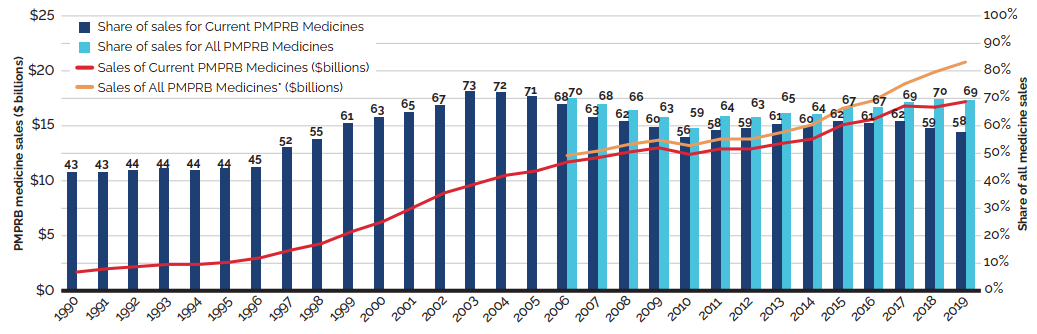

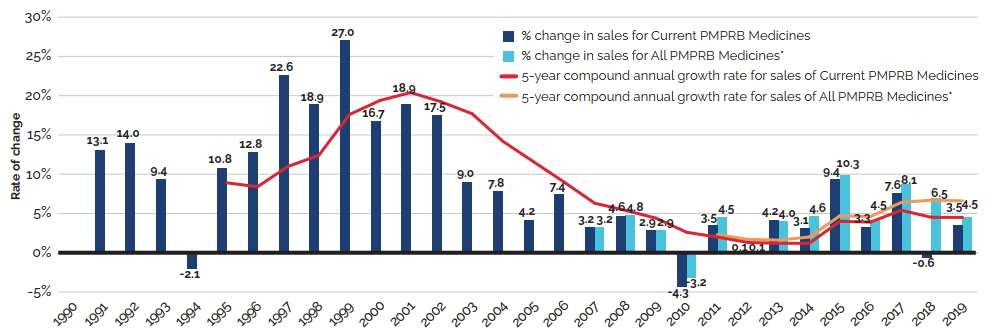

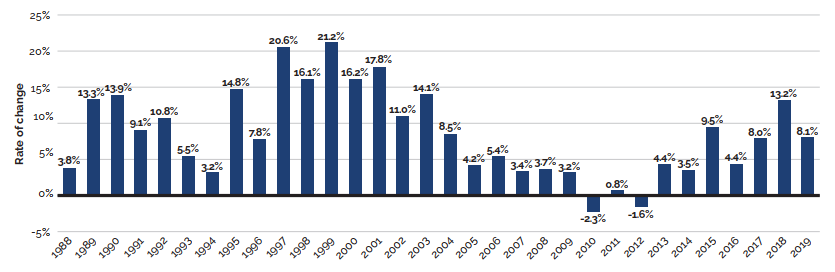

Trends in Sales Revenues

Between 2018 and 2019, there was a moderate 3.5% increase in the sales of patented medicines. Figure 3 reports on trends in the sales of patented medicines from 1990 to 2019. While there has been a 10-fold increase in annual sales since 1990, the year-over-year rate of change within that period has varied. This trend is highlighted by the five-year compound annual growth rate given in Figure 3(b).

Figure 3(a) gives the sales of patented medicines as a share of overall medicine sales. This share, which reached a peak of 72.7% in 2003, declined from 2004 to 2010. Since then, patented medicines have accounted for approximately 60% of the sales of all medicines in Canada.

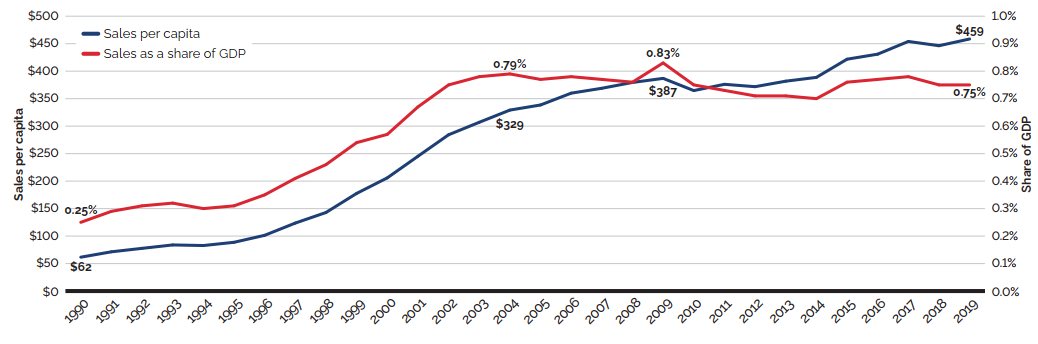

The trends in sales per capita and sales as a percentage of the gross domestic product (GDP) show the increasing importance of patented medicines in the Canadian economy. Overall, per capita sales of patented medicines rose from $61.60 in 1990 to $458.60 in 2019, while sales as a percentage of GDP rose from 0.25% in 1990 to 0.75% in 2019 [Figure 3(c)].

To highlight the continuing impact of patented medicines, Figures 3(a) and 3(b) also provide results for “All PMPRB Medicines”. This broader category includes all medicines, current and historic, that ever reported sales to the PMPRB (since its creation).

Sales for All PMPRB Medicines rose by 4.5% in 2019. Medicines that previously reported to the PMPRB accounted for estimated sales of $3.6 billion, or 12.1% of all sales. This is considerably more than a decade ago when medicines that formerly reported to the PMPRB accounted for $0.7 billion in sales, or 3.2% of all sales.

A complete table of the data presented in Figure 3 for patented medicines currently reporting to the PMPRB is included in Appendix 3.

Figure 3. Trends in Patented Medicine Sales, 1990 to 2019

* Includes sales of currently patented medicines and medicines that once reported to the PMPRB but are no longer reporting a patent.

Data source: PMPRB; MIDAS® database, 1990–2019, IQVIA (all rights reserved)

Figure description

Figure 3 (a) – Patented medicine share of all medicine sales: Current PMPRB Medicines and All PMPRB Medicines

This line and bar graphic depicts the annual sales of patented medicines currently reporting to the PMPRB and patented medicines that once reported to the PMPRB but are no longer reporting a patent and the patented medicine share of sales for current PMPRB medicines and sales for all PMPRB medicines, for the period from 1990 to 2019. In 1990, the sales of current PMPRB patented medicines was $1.7 billion and the current PMPRB patented medicine share of all medicine sales was 43.2%.

In 1991: $2.0 billion, 43.2%; 1992: $2.2 billion, 43.8%; 1993: $2.4 billion, 44.4%;

1994: $2.4 billion, 43.9%; 1995: $2.6 billion, 44.4%; 1996: $3.0 billion, 45.0%; 1997: $3.7 billion, 52.3%; 1998: $4.3 billion, 55.1%; 1999: $5.4 billion, 61.0%; 2000: $6.3 billion, 63.0%; 2001: $7.6 billion, 65.0%; 2002: $8.9 billion, 67.4%; 2003: $9.7 billion, 72.7%; 2004: $10.5 billion, 72.2%;

2005: $10.9 billion, 70.6%;

In 2006: the sales of current PMPRB medicines was $11.7 billion, current PMPRB medicines share of all medicine sales was 67.8%, the sales of all PMPRB medicines was $12.3 billion and the share of sales for all PMPRB medicines was 69.9%;

2007: $12.1 billion, 63.2%, $12.7 billion, 67.9%;

2008: $12.6 billion, 61.7%, $13.3 billion, 65.5%;

2009: $13.0 billion, 59.6%, $13.7 billion, 63.1%;

2010: $12.4 billion, 55.8%, $13.2 billion, 59.2%;

2011: $12.9 billion, 58.3%, $13.8 billion, 63.6%;

2012: $12.9 billion, 59.2%, $13.8 billion 63.0%;

2013: $13.4 billion, 60.7% $14.4 billion, 64.6%;

2014: $13.8 billion, 59.9%, $15.1 billion, 64.3%;

2015: $15.1 billion, 61.6%, $16.6 billion, 66.9%;

2016: $15.6 billion, 60.8%, $17.3 billion, 66.8%;

2017: $16.8 billion, 61.5%, $18.8 billion, 68.6%;

2018: $16.7 billion, 59.0%, $19.9 billion, 69.8%;

2019: $17.2 billion, 57.5%, $20.8 billion, 69.3%.

Note: As data is updated each year, historical results may not exactly match those reported in previous editions.

* Includes sales of currently patented medicines and medicines that once reported to the PMPRB but are no longer reporting a patent.

Data source: PMPRB; MIDAS® database, 1990–2019, IQVIA (all rights reserved)

Figure description

Figure 3 (b) – Rate of change in patented medicine sales: Current PMPRB Medicines and All PMPRB Medicines

This line and bar graphic depicts the annual rate of change in patented medicine sales and the

5-year compound annual growth rate from 1990 to 2019 for Current PMPRB Medicines and All PMPRB Medicines. Current PMPRB Medicines includes sales of patented medicines currently reporting to the PMPRB. All PMPRB Medicines includes sales for currently patented medicines as well as patented medicines that once reported to the PMPRB but are no longer reporting a patent. In 1991, the rate of change in sales for Current PMPRB medicines was 13.1%. In 1992: 14.0%; 1993: 9.4%; 1994: -2.1%.

In 1995, the rate of change in sales for Current PMPB medicines was 10.8% and the 5-year compound annual growth rate for sales of Current PMPRB medicines was 8.9%.

1996: 12.8%, 8.4%;

1997: 22.6%, 11.0%;

1998: 18.9%, 12.4%;

1999: 27.0%, 17.6%;

2000: 16.7%, 19.4%;

2001: 18.9%, 20.4%;

2002: 17.5%, 19.2%;

2003: 9.0%, 17.7%;

2004: 7.8%, 14.2%;

2005: 4.2%, 11.6%;

2006: 7.4%, 9.0%;

In 2007: the rate of change in sales for Current PMPRB medicines was 3.2%, the 5-year compound annual growth rate for sales of Current PMPRB medicines was 6.3% and the rate of change in sales for All PMPRB medicines was 3.2%.

2008: 4.6%, 5.4%, 4.8%;

2009: 2.9%, 4.4%, 2.9%;

2010: -4.3%, 2.6%, -3.2%;

In 2011, the rate of change in sales for Current PMPRB medicines was 3.5%, the 5-year compound annual growth rate for sales of Current PMPRB medicines was 2.0%, the rate of change in sales for All PMPRB medicines was 4.5%, and the 5-year compound annual growth rate for sales of All PMPRB medicines was 2.3%;

2012: 0.1%, 1.3%, 0.1%, 1.7%;

2013: 4.2%, 1.2%,4.0%, 1.6%;

2014: 3.1%, 1.2%, 4.6%, 2.0%;

2015: 9.4%, 4.0%, 9.9%, 4.7%;

2016: 3.3%, 3.9%, 4.2%, 4.6%;

2017: 7.6%, 5.4%, 8.7%, 6.4%;

2018: -0.6%, 4.5%, 6.9%, 6.7%;

2019: 3.5%, 4.5%, 4.5%, 6.6%

Data source: PMPRB; Statistics Canada; OECD

Figure description

Figure 3 (c) – Patented medicine sales per capita and as a share of GDP: Current PMPRB Medicines

This line graphic depicts Current PMPRB medicine sales per capita and as a share of GDP from 1990 to 2019. In 1990, Current PMPRB medicine sales per capita was $61.60 and as a share of GDP 0.25%. In 1991: $71.40, 0.29%; 1992: $77.70, 0.31%; 1993: $83.90, 0.32%; 1994: $82.80, 0.30%; 1995: $88.70, 0.31%; 1996: $101.40, 0.35%; 1997: $123.70, 0.41%; 1998: $142.90, 0.46%; 1999: $177.60, 0.54%;

2000: $205.90, 0.57%; 2001: $245.20, 0.67%; 2002: $284.30, 0.75%; 2003: $307.00, 0.78%;

2004: $329.20, 0.79%; 2005: $338.50, 0.77%; 2006: $360.00, 0.78%; 2007: $368.90, 0.77%;

2008: $379.50, 0.76%; 2009: $386.90, 0.83%; 2010: $364.70, 0.75%; 2011: $376.10, 0.73%;

2012: $371.80, 0.71%; 2013: $381.80, 0.71%; 2014: $388.70, 0.70%; 2015: $421.80, 0.76%;

2016: $430.94, 0.77%; 2017: $454.09, 0.78%; 2018: $446.30, 0.75%; 2019: $458.60, 0.75%.

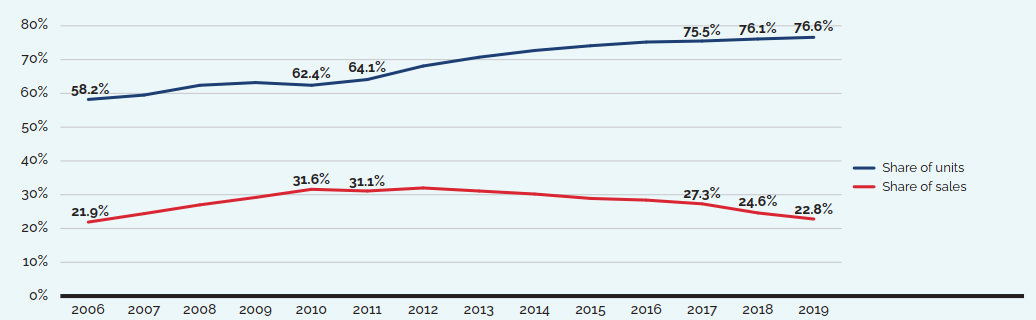

Brief Insights: Trends in the Sales of Generic Medicines

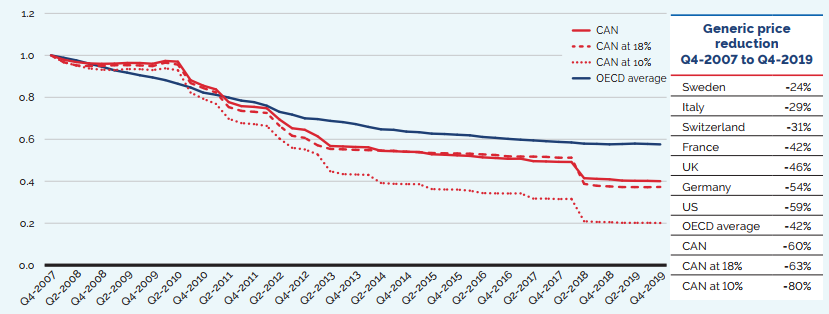

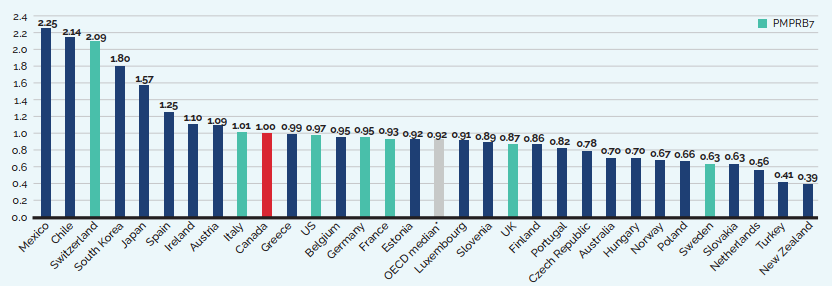

While the sales of patented medicines increased by 3.5% in 2019, retail sales of generic medicines dropped by almost 4%. Generic sales have had low or negative rates of change since 2010, due in large part to the introduction of price-setting policies initiated by individual provincial governments and through the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA).

In 2018, the introduction of a five-year joint agreement between the pCPA and the Canadian Generic Pharmaceutical Association (CGPA) reduced the prices of 67 generic medicines to 10% or 18% of their brand reference price, driving expenditures down to virtually the same level as in 2010, even while retail generic use continued to increase.

Note: The results reflect prescription sales in the national retail market based on manufacturer ex-factory list prices.

Data source: MIDAS® database, 2006–2019, IQVIA (all rights reserved)

[NPDUIS Report: Generics360, 2018 – graph updated for 2019]

Figure description

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Share of units |

58.2% |

59.5% |

62.4% |

63.2% |

62.4% |

64.1% |

68.1% |

70.7% |

72.7% |

74.1% |

75.2% |

75.5% |

76.1% |

76.6% |

Share of sales |

21.9% |

24.4% |

27.0% |

29.2% |

31.6% |

31.1% |

32.0% |

31.1% |

30.2% |

28.9% |

28.4% |

27.3% |

24.6% |

22.8% |

Drivers of the Growth in Sales Revenues

The growth in the sales revenue of patented medicines is influenced by changes in several key factors:

- Volume effect: changes in the quantity or amount of patented medicines sold.

This effect focuses on established medicines that were on the market for the entire period analyzed. Increases in the population, changes in demographic composition (e.g., shifts in the age distribution), increases in the incidence of disease, and changes in prescribing practices are among the factors that may contribute to this effect. - Mix effect: shifts in use between lower- and higher-cost patented medicines.

This effect applies to both new medicines and those that were already on the market. The switch to new higher-priced medicines, the use of new medicines that treat conditions for which no effective treatment previously existed, and changes in physician prescribing practices are among the factors that may contribute to this change. - Exiting effect: previously patented medicines that have stopped reporting sales revenue to the PMPRB or are no longer sold in Canada.

- Loss-of-exclusivity effect: medicines that have lost market exclusivity and are open to some level of generic competition but are still patented.

- Price effect: changes in the prices of existing patented medicines.

This effect applies to both increases and decreases in the prices of patented medicines over the time period analyzed.

Some factors, such as the mix effect, will generally put an upward pressure on sales, while others, such as the loss-of-exclusivity effect, have the opposite effect.

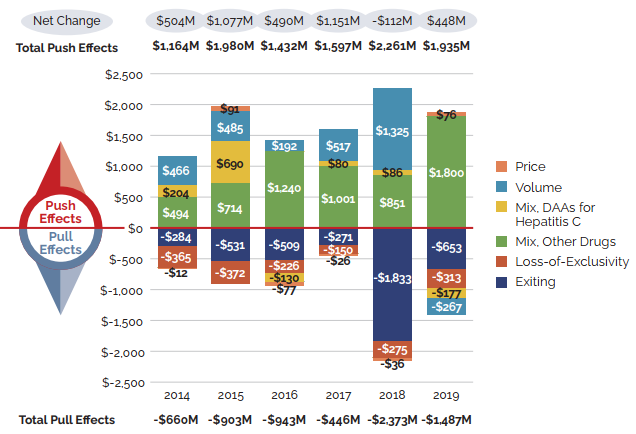

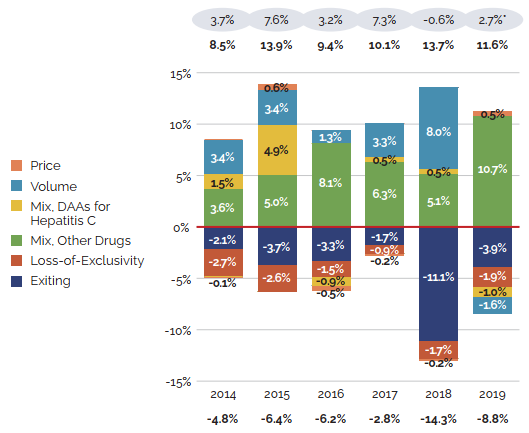

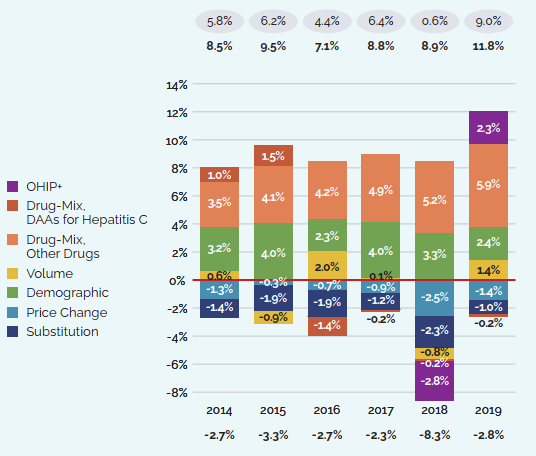

Figure 5 focuses on the major factors that drove the year-by-year growth in patented medicine salesFootnote 7 between 2014 and 2019 (a) in absolute dollar amounts, and (b) as proportions of the overall annual change in sales. In addition to the standard sales drivers, the emergence of a new “blockbuster” medicine may have a significant influence on sales and will be monitored as a separate effect. For example, direct-acting antiviral (DAA) treatments for hepatitis C are presented separately to show their continuing impact on expenditures.

Figure 5. Key Drivers of Change in the Sales of Patented Medicines, 2014 to 2019

Note: When multiple factors change simultaneously, they create a residual or cross effect, which is not reported separately in this analysis, but is accounted for in the total cost change.

Values may not add to the net change due to rounding and the cross effect.

* As this model uses various measures to isolate the factors contributing to growth, the net change reported here may differ slightly from the change in sales for the patented medicines market reported in Figure 3(b).

Data source: PMPRB

Figure description

These two bar graphs describe the factors that impacted the annual rates of change in the sales of patented medicines from 2014 to 2019. The first graph gives the rate of change in absolute dollar amounts and the second gives the corresponding percent rate of growth for each contributing factor along with the total push up (positive) and pull down (negative) effects. Direct-acting antiviral (DAA) medicines for hepatitis C are presented separately from the rest of the drug-mix effect because of their high impact.

(a) Absolute change in millions of dollars

| Exiting | Loss-of-Exclusivity | Mix, Other Drugs | Mix, DAAs for hepatitis C | Volume | Price | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2014 |

-$284 |

-$365 |

$494 |

$204 |

$466 |

-$12 |

2015 |

-$531 |

-$372 |

$714 |

$690 |

$485 |

$91 |

2016 |

-$509 |

-$226 |

$1,240 |

-$130 |

$192 |

-$77 |

2017 |

-$271 |

-$150 |

$1,001 |

$80 |

$517 |

-$26 |

2018 |

-$1,833 |

-$275 |

$851 |

$ 86 |

$1,325 |

-$36 |

2019 |

-$653 |

-$313 |

$1,800 |

-$177 |

-$267 |

$76 |

| Absolute change (millions of dollars) | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Total Push Effects |

$1,164 |

$1,980 |

$1,432 |

$1,597 |

$2,261 |

$1,935 |

Total Pull Effects |

-$660 |

-$903 |

-$943 |

-$446 |

-$2,373 |

-$1,487 |

Net Change |

$504 |

$1,077 |

$490 |

$1,151 |

-$112 |

$448 |

Note: When multiple factors change simultaneously, they create a residual or cross effect, which is not reported separately in this analysis, but is accounted for in the total cost change.

Values may not add to the net change due to rounding and the cross effect.

* As this model uses various measures to isolate the factors contributing to growth, the net change reported here may differ slightly from the change in sales for the patented medicines market reported in Figure 3(b).

Data source: PMPRB

Figure description

(b) Relative change in percent

| Exiting | Loss-of-Exclusivity | Mix, Other Drugs | Mix, DAAs for hepatitis C | Volume | Price | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2014 |

-2.1% |

-2.7% |

3.6% |

1.5% |

3.4% |

-0.1% |

2015 |

-3.7% |

-2.6% |

5.0% |

4.9% |

3.4% |

0.6% |

2016 |

-3.3% |

-1.5% |

8.1% |

-0.9% |

1.3% |

-0.5% |

2017 |

-1.7% |

-0.9% |

6.3% |

0.5% |

3.3% |

-0.2% |

2018 |

-11.1% |

-1.7% |

5.1% |

0.5% |

8.0% |

-0.2% |

2019 |

-3.9% |

-1.9% |

10.7% |

-1.0% |

-1.6% |

0.5% |

| Relative change (in percent) | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Total Pull Effects |

-4.8% |

-6.4% |

-6.2% |

-2.8% |

-14.3% |

-8.8% |

Total Push Effects |

8.5% |

13.9% |

9.4% |

10.1% |

13.7% |

11.6% |

Net Change |

3.7% |

7.6% |

3.2% |

7.3% |

-0.6% |

2.7% |

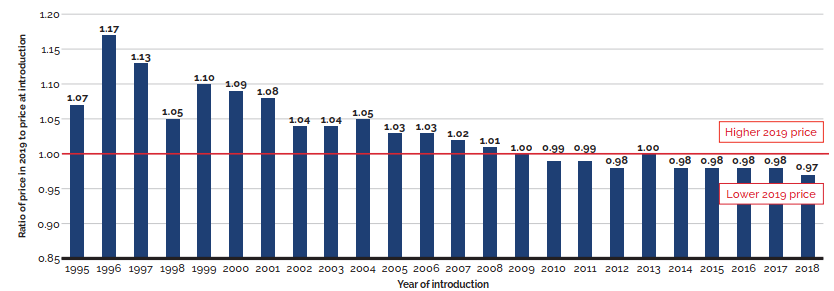

Changes in the prices of patented medicines have played a very minor role in the growth in patented medicine sales over the last several years, suggesting that, on average, the prices of existing patented medicines are fairly stable. However, this does not reflect the overall increases in treatment costs due to the entry of newer, higher-priced patented medicines, the impact of which is captured by the mix effect.

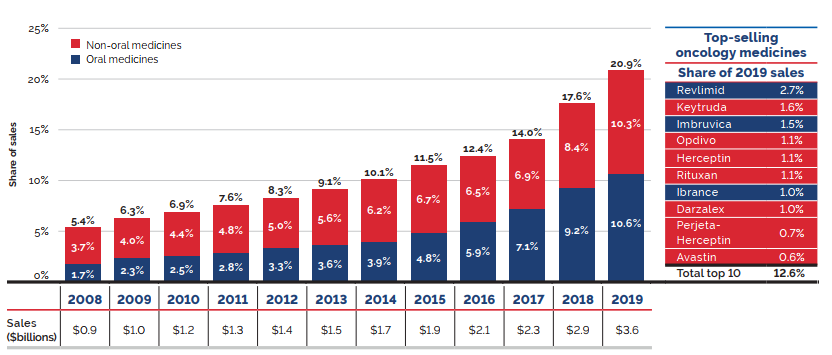

The shift to new higher-cost patented medicines has been a major driver of sales growth in recent years. In 2019, the use of higher-cost patented medicines put an upward pressure on expenditures $1.8 billion (10.7%). While growth was observed in many therapeutic areas, the increase in sales of antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents far surpassed that of any other class, and oncology medicines accounted for one fifth of the patented medicine sales in 2019. These results are discussed in further detail in the upcoming sections.

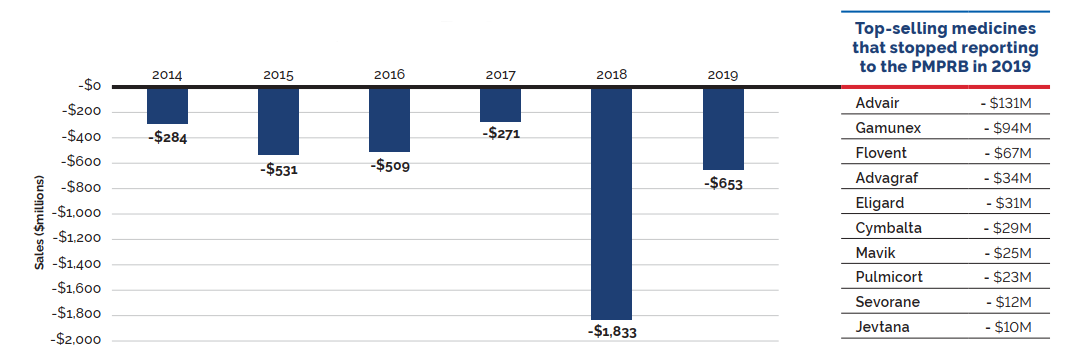

Counterbalancing this upward sales pressure, there was a moderate market segment shift as some high-selling medicines no longer reported their sales to the PMPRB. The exiting effect accounted for a moderate loss of over $650 million (-3.9%) in sales in 2019, returning to a level more in line with historic trends. Figure 6 illustrates the change in the impact of the exiting effect since 2014 and identifies the 10 top-selling medicines that stopped reporting to the PMPRB in 2019.

The volume effect also had a slight pull down effect on sales in 2019, reflecting a very small decrease in the total market quantity after a year of significant expansion.

Figure 6. Loss in Patented Medicine Sales from the Exiting Effect, 2014 to 2019

Data source: PMPRB

Figure description

This bar graph describes the change in patented medicine sales caused by patented medicines no longer reporting patents from 2014 to 2019. An accompanying table gives the change in sales for the top-selling medicines that stopped reporting patents in 2019.

| Year | Change in sales (millions of dollars) |

|---|---|

2014 |

-$284 |

2015 |

-$531 |

2016 |

-$509 |

2017 |

-$271 |

2018 |

-$1,833 |

2019 |

-$653 |

| Top-selling medicines that stopped reporting to the PMPRB in 2019 | Change in sales (millions of dollars) |

|---|---|

Advair |

- $131 |

Gamunex |

- $94 |

Flovent |

- $67 |

Advagraf |

- $34 |

Eligard |

- $31 |

Cymbalta |

- $29 |

Mavik |

- $25 |

Pulmicort |

- $23 |

Sevorane |

- $12 |

Jevtana |

-$10 |

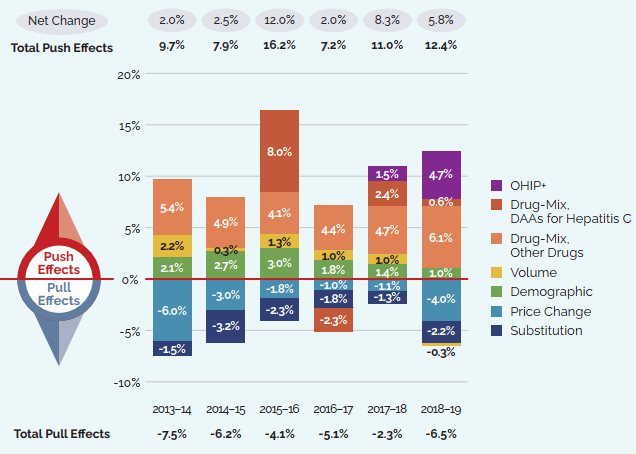

Brief Insights: Cost Drivers of Public and Private Drug Plans

The increasing use of higher-cost medicines is the primary cost driver for Canadian public and private drug plans. Over the past several years, higher-cost medicines (other than DAAs for hepatitis C) have exerted a consistent upward pressure on expenditures, accounting for a significant 6.1% contribution toward drug costs in public plans in 2018-19 and 5.9% towards private plan costs in 2019.

The savings from a new generic pricing policy introduced in 2018 had a significant impact on both public (fiscal year 2018-19) and private (2018) drug plan costs, reversing recent trends and offsetting the upward push from the use of higher-cost medicines in each of the respective years. However, policies such as this are not expected to have a sustained impact on cost growth over multiple years, and 2019 results for private plans indicate a return to historic levels.

Although the potential for additional generic savings is limited, given the strong market for biologics in Canada, biosimilars offer an opportunity for future cost savings. Recent policy changes announced by several public drug plans aimed at promoting switching to available biosimilars, as well as initiatives introduced by some private payers, are expected to result in significant cost reductions, helping to offset the pressure from higher-cost medicines in the upcoming years.

Plan design changes can also contribute significantly to growth, as was the case with the introduction of OHIP+ in Ontario in January 2018, which initially provided pharmaceutical benefits for all Ontario residents 24 and under. Since then, additional eligibility criteria have been placed on the program, the effects of which are shown in the private plan results in 2019.

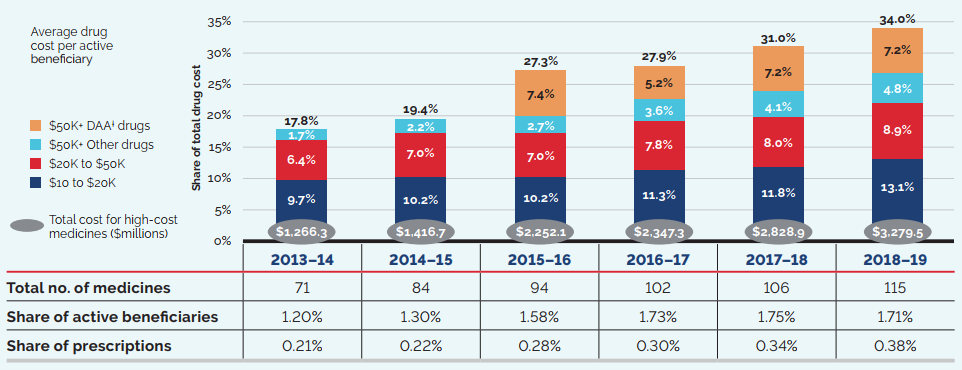

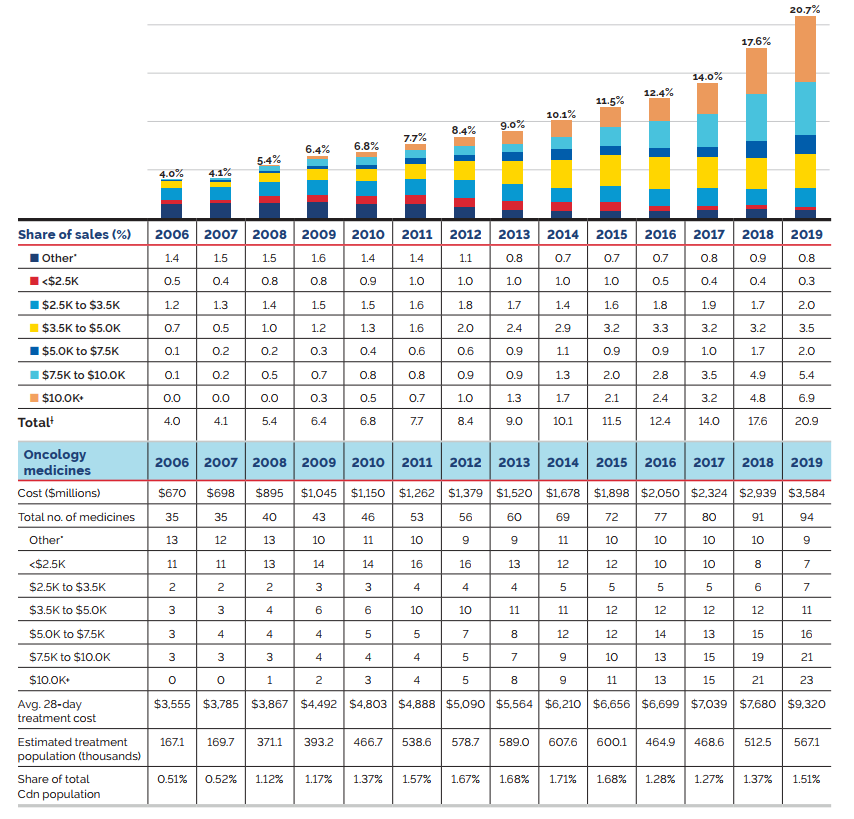

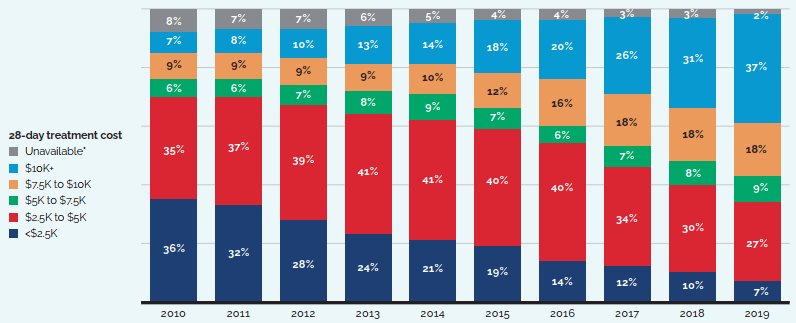

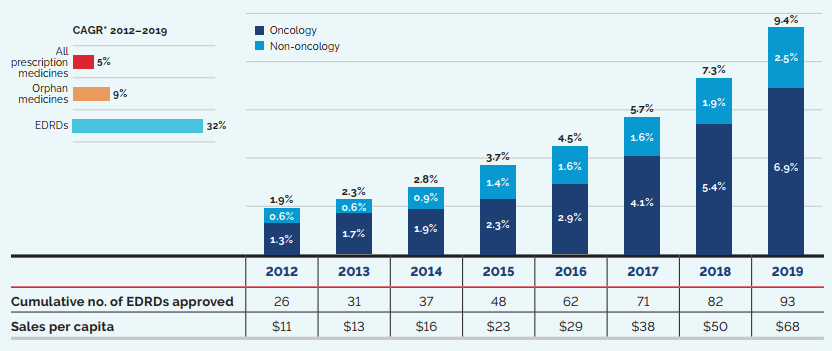

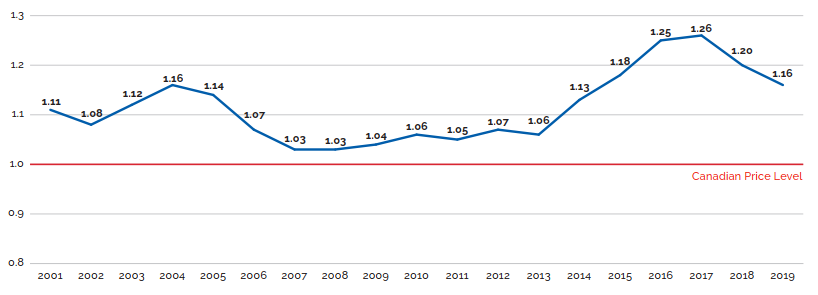

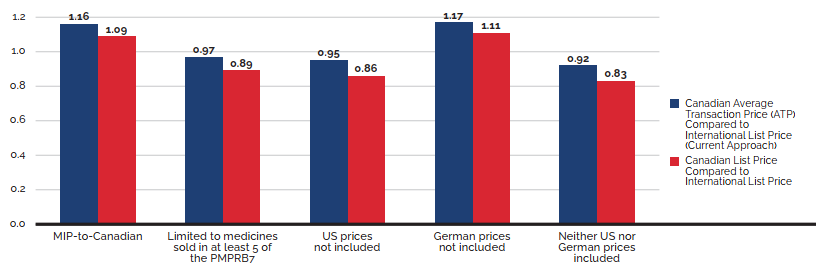

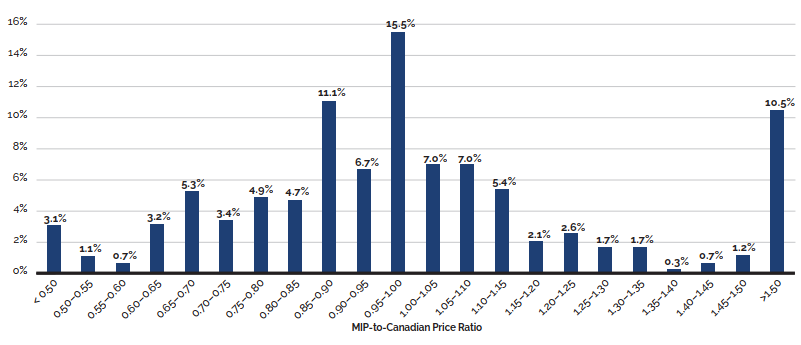

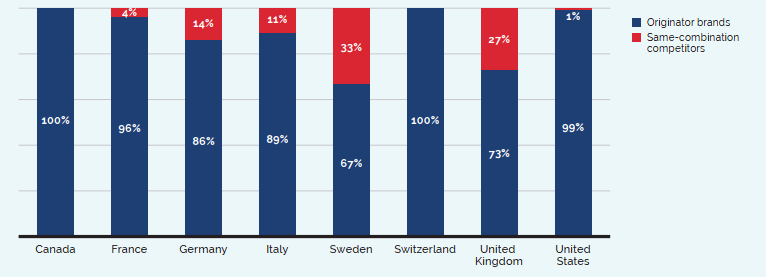

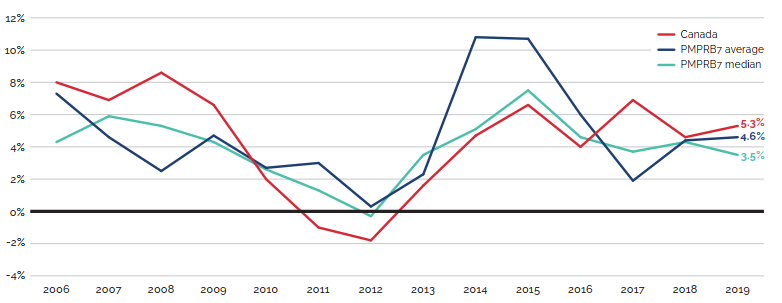

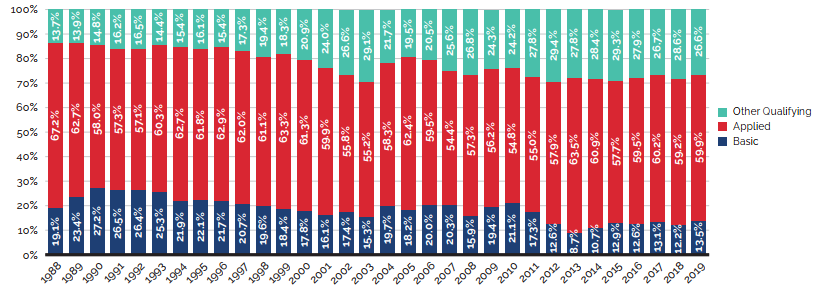

(a) NPDUIS public drug plans,* 2013-14 to 2018-19