The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2018: Preventing Problematic Substance Use in Youth

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 3.9 MB / KB, 61 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Published: 2018-10-23

A Message from Canada's Chief Public Health Officer

I am pleased to present my annual report, which is a snapshot of the health of Canadians and a spotlight on the prevention of problematic substance use among youth.

This year I am introducing a new dashboard of health indicators to provide an overall picture of the health status of Canadians. In reviewing the dashboard, it is evident that Canada continues to be a healthy nation. We are generally living long lives and rank among the top or middle third for most indicators when compared to other high income countries.

I do remain concerned, however, about the influence of persistent health inequalities and the impact of social and economic factors as barriers to living well and to the elimination of key infectious diseases.

Major chronic diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular diseases, neurological disorders, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes continue to be the leading causes of all deaths in Canada. It is important that as we age, we live in good health. Many chronic diseases can be prevented or delayed by approaches that get to the root causes of risks such as tobacco smoking, physical inactivity, unhealthy eating, and harmful use of alcohol. At the same time, mental health impacts every aspect of our lives, including relationships, education, work, and community involvement. Although the majority of Canadians report positive mental health, a third of us will be affected by a mental illness during our lifetime.

There are also worrying trends in relation to some infectious diseases. We are seeing a rise in sexually transmitted infections, while antimicrobial resistance (AMR) remains a global threat to our ability to cure infections. Lastly, as I highlighted in my previous report, tuberculosis is having a serious and ongoing impact on some First Nations and Inuit communities. Many cases of infectious diseases can be prevented or eliminated by reducing risks of exposure and ensuring access to screening and treatment – provided that partners also tackle underlying social factors by improving living conditions and confronting stigma.

To address key public health issues, I set out my vision and areas of focus for achieving optimal health for all Canadians earlier this year. I will champion the reduction of health disparities in key populations in collaboration with many partners and sectors. I will focus efforts in the areas of tuberculosis, AMR, built environments, sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections, children and youth, and the prevention of problematic substance use.

This brings me to this year's focus on preventing problematic substance use. The growing number of opioid-related overdoses and the over 8000 deaths since 2016 are tragic and unacceptable. The national life expectancy of Canadians may actually be decreasing for the first time in decades, because of the opioid overdose crisis. At the same time, because of its social acceptance, we have lost sight of the fact that continued high rates of problematic alcohol consumption are leading to a wide-range of harms. In fact, 25% of youth in grades 7 to 12 use alcohol excessively. I am also aware that the change in legal status of cannabis means we need to make sure that youth understand that legal does not mean safe.

We have to think about how to reverse these trends for future generations. That is why this report centres on youth and explores the reasons for harmful substance use, as well as effective approaches to prevent problematic use.

There is a complex interplay of factors that may lead youth to use substances. We know that the marketing, advertising, and availability of a substance can increase substance use in youth. We also know that youth are more likely to use substances as a coping mechanism when they have experienced abuse and other forms of trauma. But we also know that there are protective factors that can help build youth resilience, such as stable environments and positive family and caregiver relationships.

The interconnected nature of these factors means there is a critical need to collaborate across many sectors to develop comprehensive prevention solutions. The next generation of interventions can connect sectors such as housing, social services, education, public health and primary health care, at multiple levels to implement coordinated policies, public and professional education and programs. We can also work together with the media and private sector to promote new social norms around lower risk use of substances.

Our efforts need to value the experiences and voices of youth and those who use substances. The media, health care, and social service organizations can help to eliminate stigma and discrimination by adopting equitable and compassionate policies, practices and language.

There will never be just one answer to this ever-shifting issue of problematic substance use. This is a key moment in Canada to examine how we address substance use across all areas of potential action: prevention, harm reduction, treatment and recovery. My aim with this report is to draw attention to the central role of prevention. As important initiatives like the Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy advance, this report can help to inform these collective efforts to prevent substance use from becoming problematic.

I hope my report will stimulate discussion and lead to renewed action to achieve this goal.

Contents

- About this Report

- Chapter 1: Describing the Health of Canadians

- Chapter 2: Understanding Youth and Problematic Substance Use

- Chapter 3: Interventions for Preventing Problematic Substance Use in Youth

- Chapter 4: The Way Forward – The Path to Preventing Problematic Substance Use in Youth

- References

- Appendix 1: Glossary

- Appendix 2: CPHO Health Status Dashboard

- Appendix 3: Guidelines for Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking and Lower-Risk Cannabis Use

- Acknowledgements

About this Report

This year's report from the Chief Public Health Officer of Canada first provides a snapshot on the health status of Canadians, then shines a light on problematic substance use among youth with a focus on primary prevention. This means tackling risk factors, strengthening protective factors, delaying initiation to the use of substances, and preventing their harmful use.

The report includes the following sections:

Chapter 1: Describing the Health of Canadians provides a snapshot of the overall health of Canadians by discussing select health indicators, such as life expectancy and positive mental health. This section concludes by examining substance use and harm patterns of alcohol, cannabis and opioid use in the general population.

Chapter 2: Understanding Youth and Problematic Substance Use examines the issues around youth and substance use in Canada. It first describes the nature of youth substance use and the potential associated harms. It then explores why youth are drawn to using substances and describes the drivers that put youth at risk or that can protect them from harm.

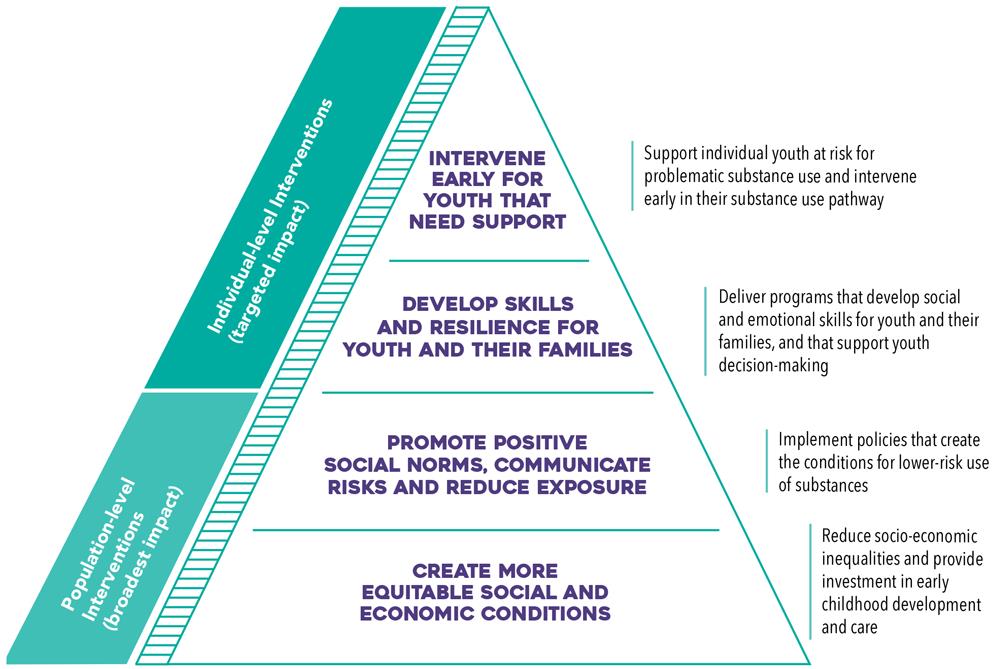

Chapter 3: Interventions for Preventing Problematic Substance Use in Youth speaks to the need for all relevant health, education and social sectors to coordinate a range of individual, community and society-wide interventions in order to prevent problematic substance use in youth. This chapter also examines population and individual level evidence-based practices and policies that can address the drivers of problematic substance use.

Chapter 4: The Way Forward – The Path to Preventing Problematic Substance Use in Youth calls upon all relevant sectors to implement an integrated suite of interventions that enhances protective factors and reduces risk factors such as stigma and trauma.

Chapter 1: Describing the Health of Canadians

Introduction

The highlights below provide a snapshot of the overall health of Canadians, by drawing on several indicators from the new Chief Public Health Officer's Health Status Dashboard (see Appendix 2).

What is a health indicator?

Health indicators are quantifiable measures that researchers and decision makers use as ways to understand the health of a population.Reference 1

In Brief:

- Overall, Canadians enjoy good health and live long lives. Current inequalities prevent certain populations from achieving their full health potential, such as those Canadians living with low income and those with low education.

- Positive mental health is just as important as good physical health. It has a protective effect that can help to prevent disease and reduce risks such as problematic substance use.

- The opioid overdose crisis in Canada is alarming. It may be shortening our national life expectancy, for the first time in decades.

- Problematic alcohol use accounts for the greatest health and social costs, based on the accumulative harms of hospitalizations, death and lost productivity. More people are hospitalized from alcohol use than from heart attacks.

What are health inequalities?

While Canadians enjoy good health overall, there are barriers preventing some from reaching their full health potential. These barriers, often called inequalities, are influenced by a complex web of individual, socio-economic, environmental, and political factors that include our income, jobs and working conditions, education, housing, the neighbourhoods we live in and the experiences that shape our early childhood. These factors, collectively known as the social determinants of health, shape our lives and influence the odds of achieving and maintaining good health over our lifetime. First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples in Canada experience additional unique social determinants of health, including the historical impacts of colonization, the legacy of residential schools, land, language and culture.

Life Expectancy

Defined as the number of years the average person can expect to live (usually from birth), life expectancy is considered one of the most general indicators for the overall health of a country.

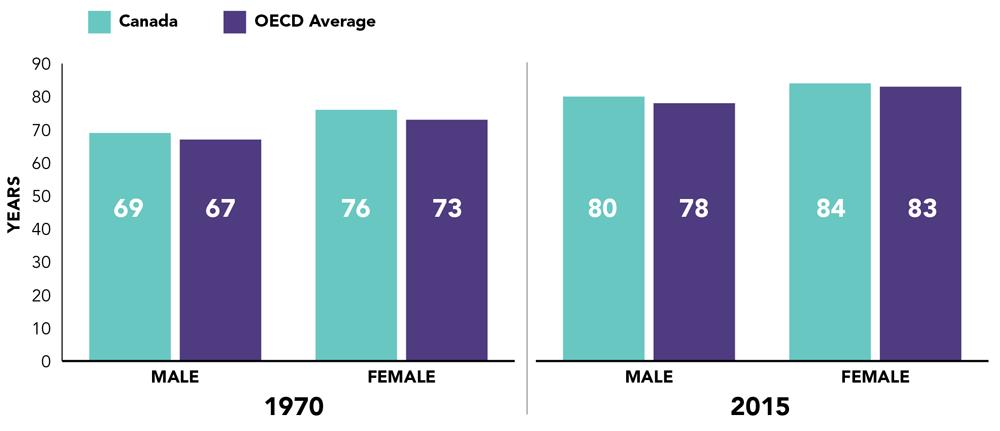

On the whole, life expectancy has been steadily increasing in Canada over many years and it is comparable to other high income countries (see Figure 1).Reference 22 Reference 23 Reference 24 Alarmingly, this is expected to change. For the first time in recent decades, life expectancy in British Columbia is decreasing, due to harms associated with opioid overdoses.Reference 9 While data are not available at the national level, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) is analyzing the impact of the opioid overdose crisis on overall life expectancy.

Figure 1: Canada's Life expectancy compared to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development'sFigure 1 Footnote * average, 1970 and 2015 (or nearest data year)Reference 23

- Figure 1 Footnote *

-

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is a group of countries who develop and discuss economic and social policy.

Source: Health at a Glance 2017

Text Description

| Year | Sex | Canada | OECD Average |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | Male | 69 | 67 |

| 1970 | Female | 76 | 73 |

| 2015 | Male | 80 | 78 |

| 2015 | Female | 84 | 83 |

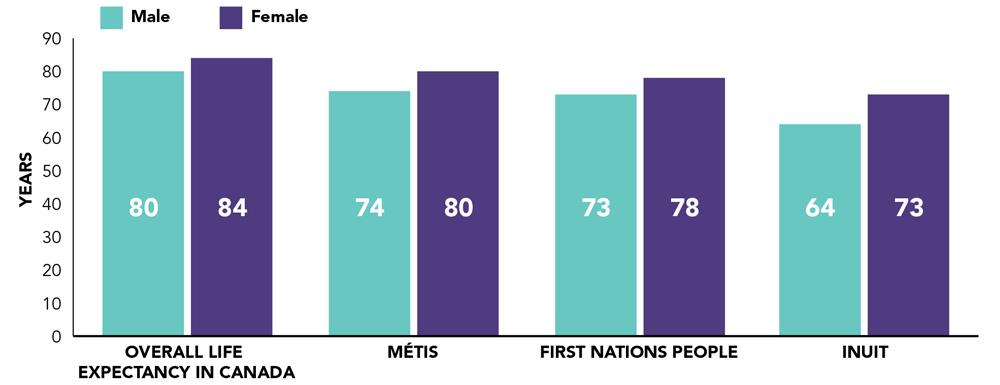

Life expectancy is not equal among all segments of Canadian society. Certain populations such as First Nations, Métis, Inuit, Canadians living with low income and those with low education experience a shorter life expectancy than the national average.Reference 25 As shown in Figure 2, there are gaps in life expectancy for First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples compared to overall life expectancy. Inuit have the largest gap, up to 16 years shorter than the overall Canadian life expectancy (64 years for males and 73 years for females).Reference 22 Reference 26 The unique cultural and historical context of Indigenous Peoples contributes to this trend. The lasting legacy of colonization and intergenerational trauma have led to systemic health inequities between Indigenous peoples and non-Indigenous populations.

Figure 2: Overall and Indigenous Peoples life expectancyFigure 2 Footnote * in Canada, 2017Reference 22 Reference 26

- Figure 2 Footnote *

-

The life expectancies for Métis, First Nations people, and Inuit are projections for 2017. Overall life expectancy figures are based on data from 2013-2015.

Sources: Life expectancy and other elements of the life table, Indigenous statistics at a glance

Text Description

| Identity | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Overall life expectancy in Canada | 80 | 84 |

| Métis | 74 | 80 |

| First Nations people | 73 | 78 |

| Inuit | 64 | 73 |

Life expectancy is about 3 years lower for those in the poorest neighbourhoods, compared to the Canadian average.Reference 25 Furthermore, it is almost 2 years higher for those in the most educated neighbourhoods, compared to the average life expectancy.Reference 25

The good news is that the inequality gap in Canada appears to be smaller than that of most other high income countries. For instance, Canada has a smaller gap in life expectancy between the highest and lowest educated groups when compared to most Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries.Reference 23 This smaller gap in no way justifies inaction. Through dedicated multi-sector actions, the public health community can support more Canadians to be healthier with improved social and economic conditions.

Disease Burden

In 2016, there was a total of 273,000 deaths in Canada. Chronic diseases accounted for 89% of these deaths; 6% were attributed to injuries (specifically self-harm, falls and road injuries); and over 5% were due to infectious, maternal, neonatal and nutritional diseases.Reference 27 As Canada's population continues to live longer, chronic diseases have become more common. The onset of chronic disease, and associated impacts, can be delayed by avoiding specific risk factors.

Chronic Diseases

In 2016, about 244,000 (89%) out of the 273,000 deaths in Canada were due to chronic diseases.Reference 27 Those accounting for the most deaths were cancers (31%), cardiovascular diseases (30%), neurological disorders (10%), chronic respiratory diseases (6%), and diabetes (3%).Reference 27

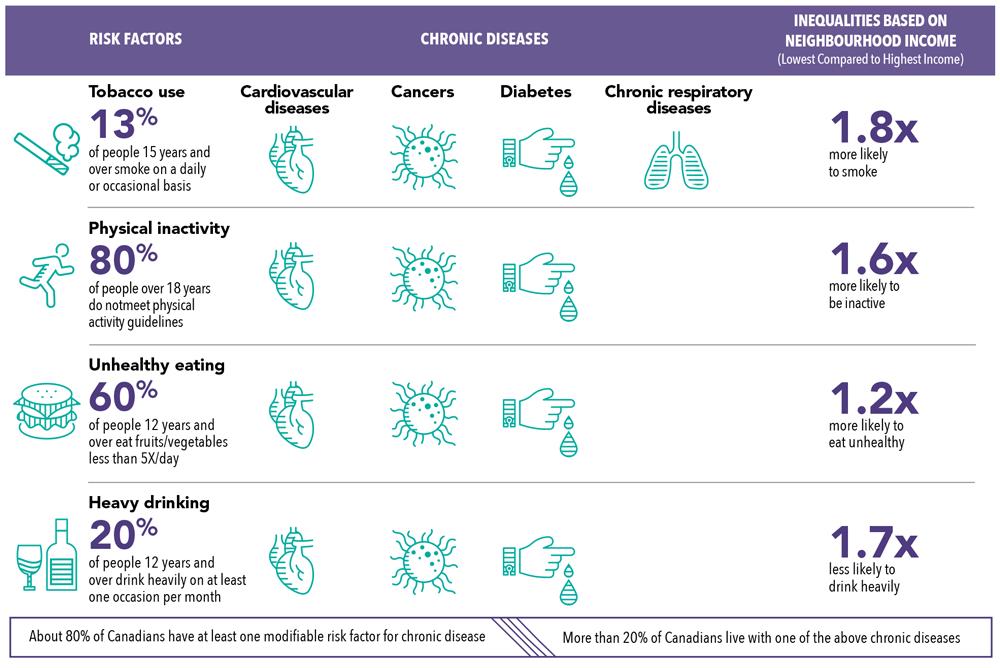

Although many Canadians are broadly considered to be healthy, many are living with a preventable chronic disease or risk factor. Indeed, more than 20% of Canadians over the age of 20 are experiencing a chronic disease such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic respiratory disease, or diabetes.Reference 24 The risk of developing many chronic diseases increases with age. About 80% of Canadian adults are living with at least one modifiable risk factor for chronic diseases, including tobacco use, physical inactivity, unhealthy eating, and heavy drinking (see Figure 3).Reference 24

Figure 3: Top 4 Chronic Diseases and Risk FactorsReference 24 Reference 25 Reference 28 Reference 29

Text Description

About 80% of Canadians have at least one modifiable risk factor for chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases, cancers, diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases. More than 20% of Canadians live with one of these chronic diseases.

The risk factors include tobacco use (13% of people 15 years and over smoke on a daily or occasional basis), physical inactivity (80% of people over 18 years do not meet physical activity guidelines), unhealthy eating (60% of people 12 years and over eat fruits/vegetables less than 5 times per day), and heavy drinking (20% of people 12 years and over drink heavily on at least one occasion per month).

There are inequalities based on neighbourhood income. Individuals from the lowest compared to highest neighbourhood income are 1.8 times more likely to smoke, 1.6 times more likely to be inactive, 1.2 times more likely to eat unhealthy, and 1.7 times less likely to drink heavily.

About 80% of Canadians have at least one modifiable risk factor for chronic disease. More than 20% of Canadians live with one of the above chronic diseases.

Delaying the onset of chronic disease and preventing risk factors are not only individual choices. These diseases are strongly influenced by factors in social, economic and physical environments. For example:

- Those living in walkable and safe neighbourhoods are more likely to be physically active. Almost 20% of Canadians report a crime rate that discourages them from walking at night in their neighbourhoods.Reference 30 Reference 31

- Access to healthy and affordable food is essential for healthy eating. This poses a particular challenge for people living in northern Canadian regions where food products are more expensive and, in some cases, traditional food is less available.Reference 32 Reference 33 Reference 34 Reference 35 Over 2 million Canadians cannot access, or afford, enough safe and nutritious food throughout the year for a healthy life.Reference 36

- Almost 30% of adults from the lowest income neighbourhoods report smoking, compared to about 15% of those from the highest income neighbourhoods.Reference 25 The annual lung cancer incidence rate is higher for those living in the lowest income neighbourhoods versus the highest income neighbourhoods (90 per 100,000 and 54 per 100,000, respectively).Reference 25

An opportunity to reduce health inequities

Applying a social-determinants-of-health lens is particularly powerful for understanding the disproportionate health burden shared by Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Throughout history, First Nations, Métis and Inuit have had to overcome such catastrophic life events as colonialism, racism, the loss of traditional and political institutions, and attempts at cultural assimilation. Problematic substance use, suicide and family violence are examples of lasting intergenerational impacts of residential school placement and resulting trauma that have influenced the health of Indigenous Peoples across the country.

For progress to be made, all partners in health must collectively recognize, support, and foster the strength and resilience of First Nations, Métis and Inuit Peoples in Canada. Long-term commitment to implementing the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission will contribute to improving health outcomes, and help individuals, families and communities to reach their full potential.

The Truth and Reconciliation Report provides a way forward to addressing the longstanding racism and discrimination perpetrated against Indigenous Peoples of Canada. The report contains 94 calls to action, which include recommendations on health, language and culture, justice, youth programming, and professional training and development.Reference 13 Reference 17

Infectious and Other Diseases

In 2016, some 13,000 (5%) out of the 273,000 deaths in Canada were due to infectious, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases – a relatively small burden compared to that of chronic diseases.Reference 27 Three percent of all deaths were caused by lower respiratory infections, such as pneumonia and influenza (between them, the leading cause of death for infectious diseases).Reference 27 Pneumonia and influenza are major contributors to deaths and hospitalizations in senior populations, especially in those over the age of 80 years.Reference 37 Reference 38 Influenza vaccinations in the elderly may lower the risk of this infection.Reference 39 Reference 40 Reference 41

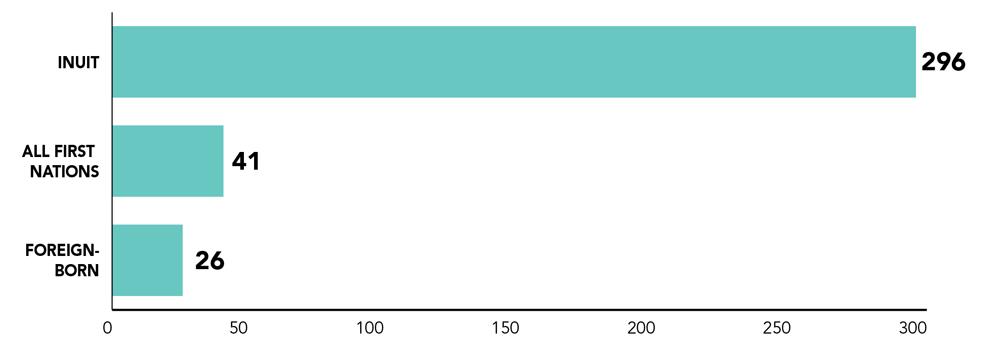

About 0.2% of all deaths are the result of tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS.Reference 27 In 2016, there were over 1,700 people diagnosed with active tuberculosis disease and over 2,300 people diagnosed with HIV.Reference 2 While not a particularly large burden for the entire country, certain populations are affected disproportionately by infectious diseases. For example, the rate of active tuberculosis cases among Inuit is close to 300 times higher than the rate in the Canadian-born non-Indigenous population (see Figure 4).Reference 42 Reference 43

Figure 4: Rate ratio of active tuberculosis disease relative to the Canadian-born non-Indigenous population rate of 0.6 per 100,000, 2016Reference 42 Reference 43

Source: Tuberculosis in Canada, 2016

Text Description

| Population Group | Rate Ratio |

|---|---|

| Foreign-born | 26 |

| All First Nations | 41 |

| Inuit | 296 |

Historically, infectious diseases were far more common across all populations in Canada before large vaccination efforts, improvements in sanitation and built environments, and advancements in screening and in treatments such as antimicrobials.Reference 44 Reference 45 Despite this progress over the past century, complacency is not an option.Reference 46 The trends of antimicrobial resistant (AMR) infections, incomplete vaccination coverage, and emerging infectious diseases related to climate change, all underscore the need to remain vigilant.

Though rates of most AMR infections are stable or declining, the rates are increasing for some, such as Neisseria gonorrhea.Reference 47 Common healthcare-associated infections like methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Clostridium difficile can be reduced with the appropriate use of antimicrobials and sterilization practices.Reference 47 The challenge with the majority of AMR infections is that they require more complex treatments.Reference 47

Overall, coverage rates for many common vaccinations in infants and children are below national goals; this may give rise in the future to outbreaks of vaccine preventable diseases, such as measles, invasive pneumococcal disease or pertussis.Reference 48 Reference 49

The number of people with Lyme disease has been steadily increasing over the past decades.Reference 50 Many factors are at play, notably the influence of climate change in expanding the natural habitat of ticks that may carry the disease.Reference 50

Many cases of infectious diseases can be prevented by reducing risks of exposure and ensuring access to screening and treatment – provided that partners in health also tackle underlying social factors by improving living conditions, and confronting stigma.Reference 43 Reference 51 For example, tuberculosis is often described as a social disease with a medical aspect.Reference 43 Unlike chronic diseases, infectious diseases like HIV or TB can be eliminated through prevention and control. It was a combination of collaborative public health efforts, such as vaccination coverage, active surveillance strategies, public awareness and, to a varying level of effectiveness, quarantine interventions, that led to the eradication of polio in Canada two decades ago.Reference 52

The rise of sexually transmitted blood-borne infections (STBBIs)

Some STBBIs have been increasing in Canada over the past two decades, most notably chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis.Reference 2 Many actions can be taken in order to prevent infectious diseases, including greater sexual health education, promotion of safe sexual practices, increased uptake of vaccinations, and the regular use of sterile drug equipment.Reference 12

Mental Health and Substance Use

In addition to good physical health, positive mental health is an essential component contributing to the overall health and well-being of Canadians.Reference 53 Reference 54

Positive mental health is “the capacity of each and all of us to feel, think and act in ways that enhance our ability to enjoy life and deal with the challenges we face”.Reference 55 The majority of Canadians report having positive mental health. About 70% describe their mental health as “very good” or “excellent”.Reference 29 Mental well-being has a protective effect that can help reduce risk factors and prevent diseases. Reference 30 High levels of social support and low stress, for example, have been found to decrease the risk of premature death and poor health.Reference 56 Reference 57 Reference 58

Other definitions of positive mental health

The First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework explains that mental wellness is supported by culture, language, Elders, families, and creation and is necessary for healthy individual, community, and family life.Reference 3

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami defines mental wellness as the physical, emotional, mental and spiritual wellness, as well as strong cultural identity.Reference 11

The Métis Life Promotion Framework promotes a holistic approach for achieving a balance among various factors of wellness.Reference 16

Over 30% of Canadians will be affected by a mental illness during their lifetime.Reference 59 Commonly reported mental illnesses include mood and anxiety disorders and substance use disorders.Reference 59 Reference 60 About 20% of Canadians report a substance use disorder in their lifetime.Reference 59 Alcohol is the cause of most frequently reported substance use disorders.Reference 59

Substance Use and Potential Harms

Currently, substance use issues are capturing the attention of public health experts, decision-makers, communities and families across Canada. The current opioid overdose crisis and the new reality of cannabis legalization are underpinning a drive to re-examine the range of substance use behaviours and their implications for public health.Reference 61 Given the acute extent of the opioid crisis, some stakeholders, including people with lived and living experiences, have asked that the decriminalizing of additional psychoactive substances in Canada be considered (decriminalization refers to the removal of criminal penalties for the possession of substances for personal use). In addition, Canadians are unfortunately not paying enough attention to the harms of alcohol.

Opioid-related deaths are reducing the life expectancy of British Columbians

Recent data from BC show that life expectancy dropped by 0.12 year from 2014 to 2016 due to deaths involving substances, with over 90% of these related to opioids. Reference 9 This dip in life expectancy was more pronounced in men and in poorer neighbourhoods.Reference 9

Most Canadians use psychoactive substances in moderation without experiencing serious consequences. Problematic use occurs when these substances are consumed in a manner, situation, amount, or frequency that causes physical or mental harm to the person using them or to those around them. This definition can incorporate behaviours beyond a substance use disorder, such as taking substances while pregnant, interfering in major social or personal duties, and/or using substances while engaging in activities that increase the risk, such as driving.Reference 62 This section summarizes the use, harms, and costs associated with alcohol, cannabis, and opioids.

What is stigma?

Stigma refers to the negative attitudes (prejudice), beliefs (stereotypes) or behaviours (discrimination) that devalue another person.Reference 4 Reference 10 There are many levels of stigma and discrimination, ranging from the personal to the societal. Negative judgements based on one's sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, or disability status, can interplay to create multiple layers of stigma. This can lead to additional social and health challenges for some.

At the personal level, stigma can be internalized, which may reduce a person's confidence and hope for the future.Reference 4 Reference 10 It can make people believe they are less worthy of respect, which can, in turn, impact their relationships, ability to get a job, find housing, and may make them less likely to seek help.Reference 10 Communities can also stigmatize people by poorly treating those perceived as different.Reference 18 From a societal perspective, institutional stigma can restrict a person's opportunities, such as access to training and employment, through restrictive policies, guidelines, or workplace culture.Reference 19

Those who live with mental health challenges or use substances often experience stigmatization. Reference 18 Reference 20 Reference 21 Also, those who experience discrimination may go on to adopt harmful use of substances as a coping strategy.Reference 18

Alcohol

Alcohol is a legal, socially acceptable, mind-altering substance that enjoys enormous popularity. However, its problematic use can lead to significant health and social harms.Reference 63 In 2016, the use of alcohol was the leading cause of premature death and disability worldwide, among people aged 15-49 years. Twelve percent of deaths for men in this age group was attributed to alcohol use.Reference 64 Although Canada’s Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines for short and long-term risks (see Appendix 3) were introduced in 2011, about 12% and 15% of Canadians exceed these guidelines for short and long-term risks, respectively.Reference 28

Use

Alcohol is the most commonly used psychoactive substance in Canada. Almost 80% of Canadians 15 years and older report drinking alcohol during the past year (see Table 1a).Reference 28 One indicator of problematic alcohol use is heavy drinking (men having 5 or more drinks or women having 4 or more drinks on one occasion at least once a month in the past year), which has been reported by about 20% of Canadians 12 years and over.Reference 29 Rates of heavy drinking have steadily increased from 14% in 1996 to 20% in 2013, and have remained stable since.Reference 29 Reference 65

Certain populations drink more heavily than others. For example, the proportion of males aged 12 years and over who are heavy drinkers is higher than that of females in the same age group (24% versus 15%, respectively).Reference 29 Furthermore, about 30% of bisexual and almost 25% of lesbian women report heavy drinking compared to nearly 15% of heterosexual women.Reference 25 Heavy drinking is reported by about 30% of First Nations living off-reserve, Métis, and Inuit adults, compared to about 20% for non-Indigenous adults.Reference 25 According to the national First Nations Regional Health Survey, about 35% of First Nations adults (18 years and over) on-reserve report heavy drinking.Reference 66

Harms

In 2015, over 3,000 Canadians died of conditions attributed to alcohol.Reference 67 The alcohol-attributed death rate for women increased by 26% from 2001 to 2017, compared with a roughly 5% increase over the same period for men.Reference 67 In 2016/2017, about 80,000 hospitalizations in Canada were due to conditions entirely caused by alcohol.Reference 67 This is higher than the number of hospitalizations for acute myocardial infarctions (heart attacks).Reference 67 Alcohol is the most common substance used by Canadians who visited publicly-funded substance use treatment centres.Reference 68

In 2017, there were over 65,000 incidents of alcohol-impaired driving.Reference 69 While close to 40% of deaths from motor vehicle crashes are alcohol-relatedReference 70, the rate of alcohol-impaired driving incidents has declined by 26% over the last 10 years.Reference 69

In addition to the direct harms of poisoning, diseases and injuries, problematic use of alcohol is strongly associated with family conflict, intimate partner violence, child abuse and neglect, and violent crimes, including sexual assaultReference 71.

Lastly, drinking alcohol during pregnancy can also lead to serious harms to both mother and fetus. It is estimated that about 10% of women in general population of Canada consume alcohol during pregnancyReference 71. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) is one of the most disabling potential outcomes of prenatal alcohol exposure. A recent study provided the first population-based estimate of the prevalence of FASD among elementary school children in Canada, which ranges between 2% and 3%Reference 220. Some special sub-populations may be at an increased risk for FASD, compared to the general population, such as children in care, correctional, special education, specialized clinical, and Indigenous populationsReference 221.

The alcohol harm paradox

Canadians with the lowest incomes report less heavy drinking but are more than twice as likely to be hospitalized for conditions attributed to alcohol, compared to Canadians with the highest incomes.Reference 8 Possible reasons for this may be higher stress levels, limited social supports, fewer resources to cope, poorer diet, and higher levels of physical inactivity among low versus high income Canadians.Reference 15

Cannabis

The Government of Canada introduced the Cannabis Act in October 2018 to legalize, strictly regulate, and restrict access to cannabis for non-medical purposes to better protect the health and safety of Canadians, in particular Canadian youth, and to remove profits from criminals and organized crime. This new policy for Canada takes a public health approach by aiming to reduce health risks from cannabis, and in particular, harms to vulnerable populations such as youth under the age of 18 years. The Act also has several additional public safety objectives which are beyond the scope of this report. Restrictions set out in the Cannabis Act for the legal production, distribution, retail sale and possession of cannabis aim to better protect youth by restricting their access to cannabis while making available a quality-controlled supply to adults. Also the legal framework provides public education and awareness of health risks to ensure Canadians have the information they need to make informed decisions about cannabis use. The Lower-Risk Cannabis Use Guidelines for Canada provide evidence-based recommendations to enable people to reduce associated health risks (see Appendix 3).

Use

Among Canadians, cannabis is the most commonly used substance after alcohol, with 12% of individuals 15 years and older reporting using it in the past year (see Table 1b).Reference 28 Reference 73 This rate has more than doubled since 1985, when it was about 6%.Reference 28 Reference 74 Use is more common among males (15%) compared to females (10%).Reference 28 Three percent of Canadians report daily or almost daily cannabis use in the past 3 months (defined as problematic).Reference 28

Although national level data by socioeconomic status are limited, some studies indicate that cannabis use is higher among urban versus rural Canadians.Reference 75 Use is also more common among certain Indigenous populations. According to the First Nations Regional Health Survey, 30% of First Nations on-reserve adults (18 years and over) used cannabis in the past year and 12% used it daily or almost daily.Reference 66

| Alcohol | Percent | Population size |

|---|---|---|

| Past year use | 77% | 22.7 M |

| Heavy drinking (12 years +)Reference 29 | 20% | 6.0 M |

| Cannabis | Percent | Population size |

|---|---|---|

| Past year use | 12% | 3.6 M |

| Daily or almost daily use (past 3 months) | 3% | 840,000 |

Harms

Although there is more to learn about long-term effects, the public health burden of cannabis use is currently less than that of alcohol and other substances like tobacco and opioids. The main contributors to cannabis-related health burden in Canada are motor vehicle crashes and substance use disorders.Reference 76 Close to 10% of adults who have ever used cannabis will develop a substance use disorder. This statistic increases for those who started using cannabis at an early age, and those who use cannabis frequently.Reference 77 Reference 78There is an increased risk of developing some types of testicular cancers for cannabis users. This risk increases for those who use cannabis frequently and for those who use it for more than 10 years.Reference 79 Although relatively uncommon, excessive and early initiation of cannabis use can increase the risk of developing schizophrenia and other types of psychoses, particularly if there is a family history involved.Reference 77 Additionally, for those who use cannabis frequently, there is a higher risk of developing a mood and anxiety disorder, as well as attempting suicide.Reference 80

In Canada, there are presently no explicit measures of cannabis use and harms during pregnancy and breastfeeding, although surveys exploring this association are underway. According to a recent systematic review on prenatal exposure to cannabis, pregnant women who use cannabis are more likely to have anemia during pregnancy and infants are more likely to be placed in the neonatal intensive care unit.Reference 81 Evidence also shows that inattention and impulsivity at 10 years of age are linked to prenatal exposure. Other poor outcomes include deficits in problem-solving skills, errors of omission and academic underachievement (particularly in reading and spelling), showing that prenatal cannabis exposure affects the ability to maintain attention.Reference 82 Reference 83

Opioids

Canada is experiencing a growing epidemic of opioid-related deaths and harms. Nearly 4,000 Canadians lost their lives to opioid overdoses in 2017 alone.Reference 84 This is equivalent to 11 Canadians dying each day. Nationally, the majority of these deaths to date have occurred among men, and individuals between the ages of 20 and 59; however, national data can sometimes mask local or regional trends.Reference 84 The opioid crisis is rapidly evolving across Canada. While historically the greatest burden of opioid deaths has been observed in Western Canada, particularly in BC and Alberta (AB), other parts of the country are also experiencing recent increases (see Figure 5).Reference 84 Reference 85

The causes of this crisis are complex and include the interplay of the excessive availability of prescription opioids and increased availability of non-prescription (illegal) opioids. First, increased prescribing of opioids is one of the drivers of opioid overdose deaths.Reference 85 Between 1980 and 2015, opioid consumption increased by a factor of 40 in Canada, from 21 to 853 morphine equivalents per person in the population.Reference 86 In 2016, over 20 million prescriptions for opioids were dispensed in Canada – the equivalent to nearly one prescription for every adult over the age of 18 years. This makes Canada the second-largest consumer of prescription opioids in the world, after the United States.Reference 85 Trends also show an increase in the prescription of more potent opioids in recent years. While the proportion of weaker opioid prescriptions (e.g., codeine) decreased between 2012 and 2016, the proportion of stronger opioid prescriptions (e.g., oxycodone, hydromorphone, and morphine) increased from 52% to 57% over the same period.Reference 87 Although relatively modest on the surface, this shift is concerning given the increased risk of harmful outcomes associated with strong opioids.Reference 87

Secondly, sharp rises in opioid-related deaths in the last few years, in parts of Canada, are believed to be mainly driven by the availability of illegal fentanyl, as rates in the legal medical dispensing of fentanyl have remained relatively stable across the country.Reference 85 Reference 87 Reference 88 Fentanyl-related overdose deaths were first reported in BC and AB in 2011.Reference 85 Since then, there has been a sharp increase in both the number and percent of fentanyl-related deaths detected in the West, with more recent rises in jurisdictions like Ontario. Reference 84 Reference 88 In 2012, 4% and 11% of opioid overdose deaths in BC and AB were fentanyl-related; by 2017, this figure climbed to 84% and 79%, respectively.Reference 84 Reference 88 Close to 70% of opioid-related deaths in Ontario (2017) involved fentanyl, compared to 24% in 2012.Reference 84 Reference 88 Additionally, highly toxic synthetic opioids are becoming more pervasive. Carfentanil – 100 times more toxic than fentanyl – has now been detected in overdose deaths in several provinces.Reference 85 More research is needed to understand the sources of illegal fentanyl products in different parts of Canada as these sources are not well understood.

Another factor likely influencing the current epidemic is the lack of awareness among Canadians of the risks associated with both illegal and prescription opioids. A 2017 survey on opioid awareness revealed that about 70% of Canadians were “very aware” that substances obtained illegally or on the street have the potential to contain fentanyl. However, almost 15% were “not at all aware” of the that risk.Reference 89 In addition, only 28% of Canadians said that they would recognize the signs of an overdose, while only about 10% said they would know how to both obtain and administer naloxone, a medication that blocks or reverses the effects of an opioid overdose.Reference 89

Figure 5: Number and rate (per 100,000 population) of apparent opioids-related deaths by province or territory, Canada, 2017Reference 84

Source: Apparent opioid-related deaths in Canada (June 2018)

Text Description

| Province or territory | Number of deaths in 2017 | Rate per 100,000 population |

|---|---|---|

| British ColumbiaFigure 5 Footnote a | 1470 | 30.5 |

| Alberta | 759 | 17.7 |

| SaskatchewanFigure 5 Footnote b | 46 | 4.0 |

| Manitoba | 122 | 9.1 |

| Ontario | 1263 | 8.9 |

| QuebecFigure 5 Footnote c | 181 | 2.2 |

| New Brunswick | 37 | 4.9 |

| Nova Scotia | 65 | 6.8 |

| Prince Edward IslandFigure 5 Footnote b | 3 | 2.0 |

| Newfoundland and LabradorFigure 5 Footnote b | 33 | 6.2 |

| YukonFigure 5 Footnote b | 7 | 18.2 |

| Northwest Territories | 1 | 2.2 |

| Nunavut | Suppressed | Suppressed |

|

||

Use

Data on the impacts of opioids on affected populations are emerging. For example, there are limited data on non-medical use of opioids and limited data as to which populations are most affected, including information on socioeconomic and common risk factors. A national study on opioid- and drug-related overdose deaths, led by the PHAC, is expected to contribute to our understanding of the drivers, causes, and determinants of the epidemic of opioid overdose deaths across Canada, and pinpoint where we need to focus additional research.Reference 6

In 2015, 0.3% of Canadians self-reported using prescribed opioid pain relievers for reasons other than for the prescribed therapeutic purposes.Reference 28 A more recent online survey from Health Canada in 2017 found that nearly 33% of Canadians who reported using opioids in the past year did not always have a prescription.Reference 85

Harms

A common thread across the country is that combined use of multiple substances has been involved in a majority of opioid overdose deaths. National data show that more than 70% of these deaths also involved one or more types of non-opioid substances such as alcohol, benzodiazepines, cocaine or methamphetamines.Reference 84 Confirmed deaths in AB (2017) indicated that 80% of fentanyl overdose deaths involved other substances as well.Reference 84

The opioid overdose crisis has touched all parts of the country and all sectors of society; nevertheless, available data highlight a disproportionate burden on certain populations. Emerging evidence from several provinces indicates that individuals living in poverty, First Nations people, and those who experience unstable housing are disproportionally affected by opioid overdose deaths.Reference 9 Reference 90 Reference 91 Reference 92 Data from Ontario indicate that emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and deaths due to opioid overdoses increase with decreasing neighbourhood income.Reference 91 Data from BC show that First Nations people are 5 times more likely to experience an opioid overdose event and 3 times more likely to die from an overdose than non-First Nations people.Reference 90 While overdoses and overdose-related deaths occur more frequently among men in the general population, First Nations men and women in BC experience similar rates of opioid overdose events.Reference 90

Individuals who experience unstable housing are also at increased risk of opioid-related harms. In BC, data collected in emergency room visits found that approximately 30% of those presenting for a known or suspected illegal substance overdose also reported unstable housing.Reference 93

More research and surveillance is needed to better understand the populations most impacted by the opioid crisis and its drivers.

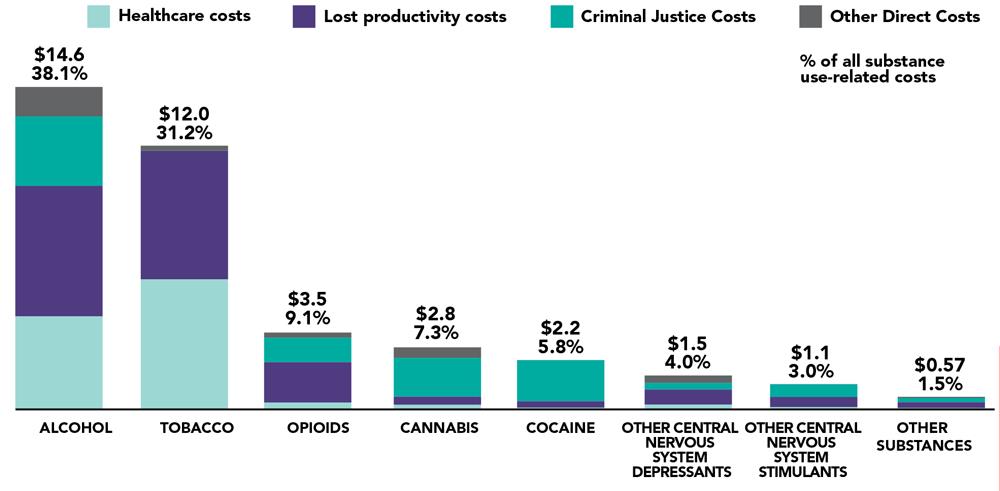

The Costs of Substance Use in Canada

Compared to other substances, alcohol use was responsible for the highest overall costs in Canada in 2014, at $14.6 billion for healthcare, lost productivity, criminal justice costs and other factors (see Figure 6). This was followed by costs related to tobacco use, estimated to be $12.0 billion a year.Reference 94 Opioid use incurred the third highest costs at $3.5 billion dollars.Reference 94 As harms associated with opioid use have increased dramatically since 2015, the associated costs are also expected to rise substantially. Finally, cannabis use incurred the fourth highest costs at $2.8 billion, with over half associated with the criminal justice system. The cost segment related to criminal justice is expected to decrease following the full implementation of cannabis legalization policy.Reference 94

Figure 6: Overall costs (in billions) by substance and cost type, 2014Reference 94

Source: Costs of Substance Use in Canada

Text Description

| Substance | Healthcare costs | Lost productivity costs | Criminal justice costs | Other direct costs | Total | % of all substance use-related costs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | 4.2 | 5.9 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 14.6 | 38.1% |

| Tobacco | 5.9 | 5.8 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 12.0 | 31.2% |

| Opioids | 0.3 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 3.5 | 9.1% |

| Cannabis | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 2.8 | 7.3% |

| Cocaine | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 5.8% |

| Other Central Nervous System Depressants | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 4.0% |

| Other Central Nervous System Stimulants | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 3.0% |

| Other Substances | 0.07 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.57 | 1.5% |

Given the burden of tobacco use on society, it is evident that tobacco control efforts should be continued.Reference 94 Reference 95 While the rest of this report does not include an in-depth focus on tobacco, it refers to tobacco use and intervention efforts as examples of ways to successfully address a complex public health issue.

Chapter 2: Understanding Youth and Problematic Substance Use

Introduction

Adolescence and young adulthood are key life stages when lifelong behaviours often become established. Ongoing physical and social changes occur as the young brain grows, puberty ensues and future adult roles are developed. At the same time, young people are coping with new social relationships and an emerging independence that may present opportunities for risk taking.Reference 96 This evolution takes place within family, community and broader peer, social, and cultural contexts that can support or challenge positive youth development. During this time, many youth experiment with substance use, but some go on to do so in ways that are harmful to themselves and others. Understanding the circumstances that can lead youth to use substances in a problematic way is a crucial step in selecting supportive and effective prevention interventions.

Youth are not a single homogenous group and can vary according to gender, race, sexual identity, ability, cultural background, economic reality and personal identity. Current health and social services may not always meet the needs of those across the spectrum of diverse backgrounds.Reference 5

In Brief:

- Close to 25% of youth in grades 7 to 12 engage in high risk drinking behaviour.

- Opioid-related hospitalizations have been rapidly increasing in the past 5 years among young adults aged 15-24 years.

- The majority of youth who use substances indicate that they do so to feel good and to be sociable.

- A much smaller group say that substances can relieve stress and help them cope with negative situations. This group is more likely to experience negative health and social consequences.

- There is no single cause of problematic substance use among youth. It involves a complex interplay of factors such as the marketing of psychoactive substances, their availability, family and peer relationships, experiences of abuse and trauma, and social factors such as stable housing and family income that can lead one towards – or protect one from – the problematic use of substances.

Youth Substance Use and Potential Harms

The earlier in life that one starts using substances and the more heavy or frequent their use, the higher the risk for problematic substance use and harms later in life.Reference 97 Focusing efforts early on can therefore help to reduce potential risky behaviours and long-term negative health effects.Reference 98

Alcohol

Use

Underage drinking is common in Canada. More than 40% of students in grades 7 to 12 reported consuming an alcoholic beverage in the past 12 months (see Table 2).Reference 99 On average, students tried drinking alcohol for the first time at 13 years of age.Reference 99 Almost 25% of students exhibited high risk drinking behaviour (5 or more drinks on a single occasion). Reference 99 Data available on heavy drinking among adolescents show that national rates increase with income. At the same time, certain sub-populations report varying rates of heavy drinking – for example, Indigenous youth living off-reserve report more frequent heavy drinking than non-Indigenous youth.Reference 25 Thirty-three percent of Métis youth (12-19 years) report heavy drinking in the past month in BCReference 100, while 10% of First Nations youth (12-17 years) living on-reserve report heavy drinking.Reference 66

| Alcohol | Percent or years | Population size |

|---|---|---|

| Past year use | 44% | 859,000 |

| High risk drinking behaviour (i.e. 5 or more drinks on a single occasion) in the past year | 24% | 487,000 |

| Average age of initiation | 13 years | N/A |

Harms

Excessive and risky drinking can impact youth in many ways. Some direct harms associated with alcohol over-consumption include injury, memory loss, sexual coercion and assaults, suicide and other forms of self-harm, alcohol toxicity and motor vehicle crashes. Long-term harms include substance use disorders, learning and memory issues, problems with school performance, increased risk of school dropout, and increased risk for certain chronic diseases. Reference 71 Reference 101 Reference 102 Reference 103 Among youth 10-19 years, girls experience much higher rates of alcohol-related hospitalization than boys, although the reasons for this are not well understood.Reference 8 Given social norms in Canadian society, there appears to be a general lack of perception, among youth, of harms due to alcohol.

Cannabis

Use

Almost 20% of students in grades 7 to 12 reported using cannabis in the past year (2016/2017) (see Table 3).Reference 99 On average, students first used cannabis at 14 years of age.Reference 99 The large majority of the students (80%) who used cannabis reported smoking itReference 99, which can cause respiratory harms.Reference 77 Other methods for consuming cannabis include edibles, vaping, and dabbing – vaporizing concentrated cannabis by placing it on an extremely hot metal object and inhaling the vapours produced.Reference 99 Some youth are more likely to use cannabis than others. For example, according to the First Nations Regional Health Survey, almost 30% of First Nations on-reserve youth (12-17 years) used cannabis in the past year and some 66% of Inuit youth (15-19 years) from a study in Nunavik reported using cannabis in the past year.Reference 66 Reference 104 Furthermore, about 40% of Métis youth (12-19 years) report having tried cannabis in the past year.Reference 100

| Cannabis | Percent or years | Population size |

|---|---|---|

| Past year use | 17% | 340,000 |

| Average age of initiation | 14 years | N/A |

| Smoke cannabis (among students who had reported ever using cannabis) | 80% | 340,000 |

| Perceive that smoking cannabis on a regular basis puts people at “great risk” of harm | 54% | 1.1M |

Canadian youth are more likely to use cannabis than adults. While rates of past year cannabis use among adolescents (about 20% of 15-19 years) and young adults (about 30% of 20-24 years) have remained unchanged between 2013 and 2015, they are still higher than the 10% rate in adults over the age of 25 years.Reference 28 Sustained weekly or more frequent cannabis use in teenagers can increase the risk for substance use disorder or mental health problems later in life.Reference 105 In 2015, about 5.1 % of youth 15-24 years reported using cannabis daily or almost daily in the past 3 months, 4.6 % used it weekly and 3.5% used it monthly.Reference 106

Harms and Risk Perception

The younger a person starts using cannabis, the greater the likelihood of them developing health problems.Reference 77 Reference 97 Initiating cannabis use at a young age – primarily before the age of 16 – and frequent use of cannabis can increase the risk for substance use disorder and psychosis. Reference 77 Reference 97 While more research is needed in this area, daily cannabis use over many years that begins in adolescence has been associated with impairments of memory, attention, and learning.Reference 107 Reference 108

In the context of legalization, the perception of risks associated with cannabis is important to monitor over time, especially among youth. When students in grades 7 to 12 were asked if they thought smoking cannabis once in a while could be harmful, about 20% responded that this could put people at “great risk” of harming themselves, and about the same percentage said that it posed “no risk”.Reference 99 When the same group was asked if they thought that smoking cannabis regularly could be harmful, only just over 50% responded that this could put people at “great risk”, while close to 10% said it posed “no risk” of harms.Reference 99

Opioids

Use

Three percent of students in grades 7 to 12 report using prescribed opioids (this includes opioids prescribed to the survey respondent or taken from a family member or friend) for non-medical reasons (e.g., to get high) in the past year (2016/2017), including 1% and 0.5% who reported using oxycodone and fentanyl to get high, respectively (see Table 4).Reference 99 Some youth are particularly vulnerable to problematic opioid use. In one recent study of young adults (16–25 years) who had used opioids in the last 3 months, LGBT youth were nearly twice as likely to use opioids intensively (i.e., longest duration and most consistent harmful use of opioids).Reference 109

| Prescription Opioids | Percent | Population Size |

|---|---|---|

| Use of pain relievers to get high in the past year | 3% | 61,000 |

| Use of oxycodone to get high in the past year | 1% | 24,000 |

| Use of fentanyl to get high in the past year | 0.5% | 10,000 |

Harms

Between 2010-2015 in Ontario, the most substantial increase in opioid-related deaths occurred among those aged 15-24 years.Reference 110 About 10% of all deaths among young adults aged 15-24 years in Ontario were opioid-related, a rate that has nearly doubled in the last 5 years. Reference 110 While these mortality trends may be unique to Ontario, pan-Canadian hospitalization data mirror these findings, showing that the age group of 15-24 years experienced the fastest-growing rates of hospitalizations related to opioid overdoses between 2007-2008 and 2015-2016.Reference 111 During the same period, over 50% of opioid overdoses among youth that led to hospitalization were intentional, or overdoses that occurred as a result of self-inflicted harm. Reference 112 The reasons for this are not well understood – in order to inform prevention efforts, public health officials need better evidence on the reasons why youth use opioids, as well as on the source of the opioids they obtain.

Reasons Why Youth Use Substances

Youth report a range of reasons to explain why they use substances. The most common reasons in relation to cannabis and alcohol are “having fun” and “being social”.Reference 113 Reference 114 A smaller group report using substances to deal with stress or emotional pain. This group is at greater risk of problematic substance use.Reference 115

Because it is fun and social

Youth most often report that “having fun” and celebrating are the main reasons for drinking alcohol.Reference 113 Reference 114 Students said that they drank alcohol mainly because they enjoy the taste and it is a part of being sociable with their friends.Reference 116 These reasons are similar for why youth report using cannabis, which is “to experiment” and “to be social”. For cannabis specifically, youth also report using it “to be more creative and original”.Reference 117

To deal with stress or emotional pain

A smaller number of young people use alcohol and cannabis to cope with stress. Students who reported poor mental health were more likely to also report using substances as a coping strategy or because they felt down or sad.Reference 115 Youth report using cannabis to cope because they feel depressed, want to reduce stress and anxiety, or want to escape reality or a negative situation.Reference 117 Reference 118 Another study showed that youth who used alcohol as a coping strategy were more likely to report difficulties from their alcohol use, such as fights, arguments with their friends or family members, or having problems with school.Reference 114 Similarly, youth who use cannabis as a coping strategy are also more likely to report problems such memory loss, lower productivity and difficulty sleeping.Reference 119 Lastly, some youth also use cannabis for relief of physical pain.Reference 115 Reference 118

Finally, although reasons for opioid use among youth are not yet fully understood, some have reported using these “to get high” or to self-medicate.Reference 99 Public health officials need more comprehensive surveillance data on the reasons why youth use opioids in order to better inform prevention efforts.Youth Risk and Protective Factors

A range of interacting risk and protective factors in a young person’s life either place them at greater risk of problematic substance use, or protect them from this risk. Reference 5 Reference 120 These factors are neither independent of each other nor are they simply a reflection of an individual’s personal characteristics. Instead, they are dynamic and span across the social contexts in which youth grow up. Reference 5 Reference 120

Figure 7 shows examples of risk and protective factors for problematic substance use in youth. The individual is nested within the influences of society at large as well as within their own family and community context. These factors are shaped through the life course, from the prenatal environment to adulthood. Some risk factors may be more powerful than others at certain stages of development, such as peer pressure during the teenage years. Equally, some protective factors, such as a strong parent-child bond, can have a greater impact on reducing risks during the early years and build resilience. This, in turn, can influence many health and socioeconomic outcomes in childhood and later life.Reference 120 An important goal of prevention is to shift the balance in favour of protective factors over risk factors (see Table 5).

Figure 7: Examples of risk and protective factors associated with problematic substance use in youth

Text Description

This figure depicts a model of various levels of risk and protective factors at the individual, interpersonal, community, and societal/structural levels.

- The individual level includes such factors as resilience, mental health status, and genetics.

- The interpersonal level includes such factors as early childhood development, physical and sexual abuse and other types of violence, and family member with problematic substance use.

- The community level includes such factors as school connectedness and environment, social and community connectedness, availability of and access to health and social services, and availability of and access to substances.

- The societal/structural level includes such factors as marketing practices and social norms, colonization and intergenerational trauma, stigma and discrimination, and income and housing policies.

At the broader societal level in Canada, inequalities related to the determinants of health – in particular, poverty and access to safe and affordable housing – are linked to increased risk of problematic substance use among youth.

At the same time, certain youth populations also face their own unique determinants. The historical and ongoing effects of colonization for First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities reflect intergenerational trauma in the lives of many Indigenous youth and the consequences these legacies have on the eradication of culture, traditional values, and the loss of traditional family stability.Reference 13 These risk factors for Indigenous communities are countered by such protective factors as cultural continuity, which has been associated with reduced suicide rates among First Nations youth in BC.Reference 121 Reference 122 Research shows that connection to land, cultural ceremonies, and healing traditions can reduce the risk of problematic substance use among Indigenous youth by linking them to the knowledge and skills that help them attain meaningful connections around family, spirituality, and identity.Reference 123

Risk and protective factors for harmful use of substances are not distributed equally among all youth. Other specific groups who are at higher risk than their peers include homeless or street-involved youth; youth in custody; youth living with co-occurring mental health problems; youth with a history of trauma; as well as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender and questioning youth.Reference 5 Common risk factors among these populations include a history of trauma; exposure to sexual and physical abuse or other types of violence; experiences of stigma and discrimination (including racism, heterosexism, and transphobia); and resulting mental health issues.Reference 5

Some risk factors speak to individual and interpersonal differences – for example, youth who have a family history of substance use and/or a mental illness are also at greater risk of using substances in a harmful manner.

There is growing evidence that protective factors in the lives of even the most vulnerable young person can buffer risk and boost resilience. Connectedness to school, positive relationships with caring adults inside and outside the family, supportive peers, as well as school and community safety, can all enhance an individual’s ability to cope with everyday responsibilities and reduce the likelihood of difficulties that lead to problematic substance use.Reference 120

| Risk and Protective Factors | Association with Problematic Substance Use |

|---|---|

Marketing practices and social norms |

Research shows that exposure to alcohol and tobacco marketing increases the probability of using these substances.Reference 124 Reference 125 Marketing can shape social norms by portraying substances in a positive light and targeting concepts such as social approval, autonomy, self-image and adventure seeking. Reference 124 Popular media also perpetuate the use of both legal and illegal substances.Reference 126 Reference 127 A 2010 scientific review identified that increased non-advertisement media exposure (i.e., television, music and film) was significantly associated with smoking initiation, use of illegal substances and alcohol consumption among children and adolescents.Reference 128 |

Colonization and intergenerational trauma |

The historical and ongoing effects of colonization and the residential school system in Canada continue to impact First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities, across several generations. The latest First Nations Regional Health Survey found higher rates of problematic substance use (i.e., heavy drinking) among First Nations youth who had at least one parent who attended a residential school, when compared to non-First Nations youth.Reference 90 |

Stigma and discrimination |

Experiencing stigma or discrimination based on race/ethnicity, Indigenous identity, mental health status, disability, and/or LGBTQ2 status can heighten the risk of harmful use of substances for certain groups of youth. Reference 5 Reference 129 The resulting intersecting layers of stigma and discrimination can, in turn, perpetuate a cycle of problematic substance use. Reference 129 In addition to public stigma that perpetuates negative language and stereotypes that may lead to social exclusion, restricted opportunities, and diminished self-efficacy among people who use substances, institutional stigma can lead to significant barriers in accessing health care, housing, and employment.Reference 4 Reference 19 As people who use substances internalize public and institutional stigma, they may experience loss of confidence, as well as feelings of embarrassment and shame, discouraging them from seeking help for their disorder.Reference 18 |

Income and housing policies |

Poverty among families with children is associated with substance use later in life, although the pathway may not always be direct. For example, children from low-income families are more likely to go to school hungry. This, in turn, affects their ability to learn and to perform in school – which is associated with increased harmful use of substances.Reference 130 Reference 131 Children from low-income families are also less likely to experience such long-term protective factors as daily reading, parental time, involvement in school based activities, and time and/or money for recreational activities. Reference 130 Reference 131 Reference 132 Reference 133 Reference 134 Living in low-income and disadvantaged neighbourhoods is also linked to higher levels of exposure to illegal substances, substance use and poisonings.Reference 135 Reference 136 Access to safe, stable housing is another important predictor, as those lacking it will often turn to substances as a coping strategy.Reference 137 Youth facing housing insecurity are at a greater risk of engaging in harmful use of substances.Reference 131 Indeed, homeless or street-involved youth experience elevated health and social challenges, and homelessness is a strong determinant of substance use initiation among youth (even after adjustment for various socio-demographic factors).Reference 138 Certain populations also experience higher rates of housing need than others. First Nations people living off reserve, Métis, and Inuit experience housing below standards – homes considered unsuitable, inadequate or unaffordable – at a greater rate than the non-Indigenous population. In Canada, in 2011, about 50% of First Nations people living off reserve and Inuit, and 40% of Métis lived in housing below standards.Reference 25 |

| Risk and Protective Factors | Association with Problematic Substance Use |

|---|---|

School connectedness and environment |

School connectedness refers to the extent to which students perceive that they are accepted, respected, included, and supported by others in the educational environment.Reference 139 Reference 140 Reference 141 These connections protect youth from many health risks, including early initiation of smoking and alcohol use. Reference 139 Reference 140 This is closely related to the concept of positive school environment, which has a demonstrated protective effect against problematic substance use and is associated with lower rates of alcohol and cannabis use among adolescents.Reference 142 Over 60% of Canadian students in grades 6 to 10 reported feeling a sense of belonging at school.Reference 143 |

Social and community connectedness |

The caring and respect engendered by positive social relationships, and the resulting sense of satisfaction and well-being, serve as a buffer against many health issues. The more that youth engage with their communities, the less likely they are to participate in risky behaviours with their peers. Instead, they have greater opportunities to develop independence, confidence and good decision-making, while broadening their social networks to include more peers who model and encourage positive behaviours.Reference 144 Structured community activities can also expose youth to positive mentors and serve as a source of emotional support.Reference 144 Community involvement also increases youths’ sense of competence as they succeed in non-academic pursuits, which may positively influence subsequent attitudes, goals, and other means of contributing to society. Reference 144 Neighbourhood disorganization is associated with problematic substance use.Reference 145 Risk factors associated with disorganized neighbourhoods (e.g., increased crime, limited access to safe outdoor areas, vandalism, and publicly visible substance use) may create an environment that limits protective factors (e.g., access to safe recreational and social spaces, and school- or community-based organizations that offer the opportunity to build caring relationships with adults outside the home). Reference 146 In 2013/2014, about 60% of grades 6 to 10 students reported that they can trust people where they live.Reference 143 Ninety percent of 15–17 year olds reported that their neighbourhood is a place where neighbours help each other.Reference 143 Moreover, about 6% of 15–17 year olds reported that social disorder in their neighbourhood is “a very big problem” or “a fairly big problem”.Reference 143 |

Availability of and access to health and social services |

Youth living with poor mental health are more likely to engage in harmful use of substances than those who are not – early intervention following the first episode of a serious mental illness can lead to positive health outcomes later in life.Reference 146 Fewer than 25% of Canadian children with a mental health disorder receive specialized treatment services.Reference 147 Mental health and other health care practitioners can play a key role in identifying youth who may need support and those who already experience substance use issues by screening, providing brief interventions and, if needed, referring them to substance use treatment programs and ongoing monitoring and follow-up.Reference 146 Several screening tools are available to practitioners.Reference 148 |

Availability of and access to substances |

Substance use increases among youth who have high availability and easy access to them. Substances can become more available through the community (e.g., density of retail locations and low cost), family (e.g., readily found in the home and/or a low level of parental monitoring), peers, and the health care system (e.g., physician prescribing practices). Close to 70% of Canadian students in grades 7 to 12 report that it is fairly easy or very easy to access alcohol, followed by cannabis (39%) and prescription pain relievers (25%).Reference 99 |

| Risk and Protective Factors | Association with Problematic Substance Use |

|---|---|

Early childhood development |

Negative experiences in a child’s life can lead to future poor health (e.g., obesity, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes), poorer educational attainment, economic dependency, and greater risk of problematic substance use and depression.Reference 149 Reference 150 The Early Development Instrument measures school readiness – a demonstrated predictor for substance use later on in life. In Canada, more than 25% of childrenReference 151 are vulnerable in at least one of the 5 areas of development prior to entering grade 1: physical health and well-being, social competence, language and thinking skills, communication skills and general knowledge, and understanding and managing emotions. |

Physical and sexual abuse and other types of violence |

The connection between physical abuse, sexual abuse, and other types of violence with substance use later on in life has been well-established.Reference 152 Reference 153 Abuse can disrupt early development by impeding a child’s ability to cope and by contributing to cognitive impairment. Over time, harmful use of substances may result as a coping mechanism.Reference 153 A nationally representative Canadian survey from 2012 found that those who self-reported physical abuse, sexual abuse, or exposure to intimate partner violence before the age of 16 years were about 3.5 times more likely to report problematic substance use compared to those who did not (even after adjustment for various socio-demographic variables, such as age, sex, education, and income).Reference 152 The severity of child abuse also plays a role in substance use risk. Canadians who have been exposed to all 3 forms of violence (referenced above) are almost 11 times more likely to report a substance use disorder than those not exposed to any abuse. Reference 152 A third of Canadians over the age of 15 (33%) report experiencing at least one of these 3 types of child abuse before the age of 15 years.Reference 154 |

Family member with problematic substance use |

Substance use in the family increases the likelihood that youth have direct exposure and access to substances. Harmful use disrupts routines and social support, contributing to stressful family environments. Reference 155 Reference 156 Negative parental or sibling modeling of behaviors and attitudes regarding substance use is a risk factor for youth.Reference 156 For instance, maternal smoking, alcohol use, and illegal substance use have been linked to cannabis and other substance use disorders in young adults.Reference 157 Moreover, children who experience both maltreatment and dysfunction in a family setting have the highest risk for mental health issues in adulthood.Reference 153 In 2012, nearly 30% of Canadian students (15–17 years) reported having a family member who had problems with their emotions, mental health or use of substances and over 25% said that they were affected “a lot” or “some” by this situation.Reference 143 |

| Risk and Protective Factors | Association with Problematic Substance Use |

|---|---|

Resilience |

Resilience is commonly recognized as a protective factor against problematic substance use among youth. While lacking a universal definition, it is often described as the ability to transform stressful events and/or adversity into opportunities for learning. Reference 158 Reference 159 Resilience includes a dynamic interplay of individual resources (e.g., problem solving skills, confidence, coping skills), relational resources (e.g., relationships with primary caregivers, parents, mentors, teachers) and contextual resources (e.g., community and culture) that help young people cope with challenging situations. Reference 159 Reference 160 There are various ways to measure resilience and no single national indicator is currently used. However, national level data from 2012 (based on proxy measures) show that only 45% of 12-17 year olds reported a high level of perceived control over life changes, while over 40% reported having the skills necessary to cope with everyday responsibilities.Reference 143 |

Mental health status |

Elements of positive mental health, such as living in a stable and nurturing home, attachment to family and school, and living in a safe, supportive neighbourhood have long been shown to protect against problematic substance use among youth.Reference 161 On the other hand, poor mental health and mental illness are well-established risk factors for influencing the harmful use of substances.Reference 77 Youth living with mental illness may use substances as a way to manage or cope.Reference 5 Reference 162 Moreover, youth who use substances frequently and/or at an early age are at greater risk of developing substance use disorders. The co-occurrence of problematic substance use and mental illness and disorders (particularly anxiety and depression) can generate a cycle of poor outcomes, including a high relapse rate if the disorders are not treated at the same time as the mental illness. Reference 161 |

Genetics |

Interactions between genes and the environment may in part explain protective factors (e.g., parental attachment) or risk factors (e.g., childhood trauma, unstable housing, or poverty) that influence substance use early in life.Reference 163 Reference 164 Reference 165 Reference 166 No single gene predisposes one to substance use. Rather a multitude of genes interact with each other and their environments, making individuals more or less susceptible to substance use disorders.Reference 163 Reference 164 Evidence indicates that such disorders can run in families.Reference 157 Reference 167 Their potential to be inherited varies among substances. More addictive ones (such as opiates) are more likely to be passed down through families.Reference 163 |

Chapter 3: Interventions for Preventing Problematic Substance Use in Youth

Introduction

Preventing or reducing problematic substance use among youth in Canada can only be achieved through a range of coordinated actions that serve to promote wellness, reduce risks and harms, strengthen protective factors, and improve access to quality mental health and support services. Any measures implemented must be culturally safe for all youth and not stigmatize those who use substances. This section outlines the principles and components of a comprehensive and equitable approach to prevention. Intervening early to counteract the risk factors of problematic use offers the best chance of having a positive influence on a young person's development and reducing long-term harms to them and to society as a whole.Reference 5

In Brief:

- Actions guided by core principles – trauma-informed, equitable and safe for diverse populations, and youth and community driven – will ensure that policies and programs recognize the diverse needs of youth.

- A range of actions to promote wellness, reduce risks and harms, and improve access to quality mental health and support services are required.

- A comprehensive approach includes policies and programs that:

- Create equitable social and economic conditions