Full report: A Vision to Transform Canada's Public Health System

Chief Public Health Officer's Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2021

Download in PDF format

(1.54 MB, 129 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Date Published: 2021-12-13

Cat.: HP2-10E-PDF

ISBN: 1924-7087

Pub.: 210338

Table of contents

- Message from the Chief Public Health Officer of Canada

- About this report

- Section 1. COVID-19 in Canada and the world

- Section 2. Public health in Canada: Opportunities for transformation

- Section 3. A vision to transform public health in Canada

- The way forward

- Appendix A: Methodology

- Acknowledgements

- References

- Endnotes

Message from the Chief Public Health Officer of Canada

The COVID-19 pandemic represents the biggest public health crisis that our country has confronted in a century. There is no doubt that this has tested our public health systems. And while there have been challenges, there have also been remarkable achievements, such as Indigenous ownership of the pandemic response in their communities and the rollout of the largest mass vaccination program in Canadian history. I am incredibly proud of the over 28 million Canadians 12 years of age and older who have been fully vaccinated so far. With the recent approval of Canada’s first COVID-19 pediatric vaccine formulation for children 5 to 11 years old, we will continue to see our vaccine coverage rates increase across the country.

There is no doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic will continue to be a key public health priority in Canada for the foreseeable future. At the time of publishing this report, Canada is in the midst of a fourth wave fuelled by the highly transmissible Delta variant and a new variant of concern, Omicron, has recently been identified by the World Health Organization. It is still too early to know how this new variant will impact our pandemic response in Canada but its emergence reminds us that we need to remain vigilant and adapt our response as needed moving forward. At the same time, there are other pressing public health issues that also require urgent action. These include the worsening opioid overdose crisis, increasing mental health challenges, the health impacts of climate change, and the ongoing threat of antimicrobial resistance.

While our public health system has extended itself to meet the increased demands of COVID-19, it is stretched dangerously thin. The pandemic has highlighted the strengths of our system but it has also exposed long-standing cracks in the foundation. The public health system lacks the necessary resources and tools to carry out its critical work, and is the subject of “boom and bust” funding cycles that leave us ill-prepared in the face of new threats.

Moving forward, we must ensure that our public health system is better equipped to protect all people living in Canada and help them to achieve optimal health.

Simply put, we must act now to ensure that our post-pandemic future is different than our pre-pandemic past.

In my 2020 annual report, I examined the broader consequences of the pandemic, and how persisting health and social inequities have resulted in disproportional impacts of COVID-19 on some populations. The report highlighted the need for a strengthened public health system that is centred on health equity and working towards good health and wellness for all.

My 2021 annual report builds on these findings. It draws from the diverse input of public health leaders, researchers, community experts, intersectoral collaborators, and First Nations, Inuit, and Métis leaders. Working from the foundational building blocks of public health systems in Canada, my report outlines strategic opportunities and key actions for achieving a transformed public health system that best protects us all against current and emerging public health challenges.

While the pandemic is not yet over, we are at a pivotal moment where we can come together to reflect on what we have learned and, collectively, define a new way forward. Joining forces across communities and sectors, we can build the public health system that we all need and expect, in pursuit of the healthy and thriving society that we all want. It is in working together that we can make sure that we get it right.

About this report

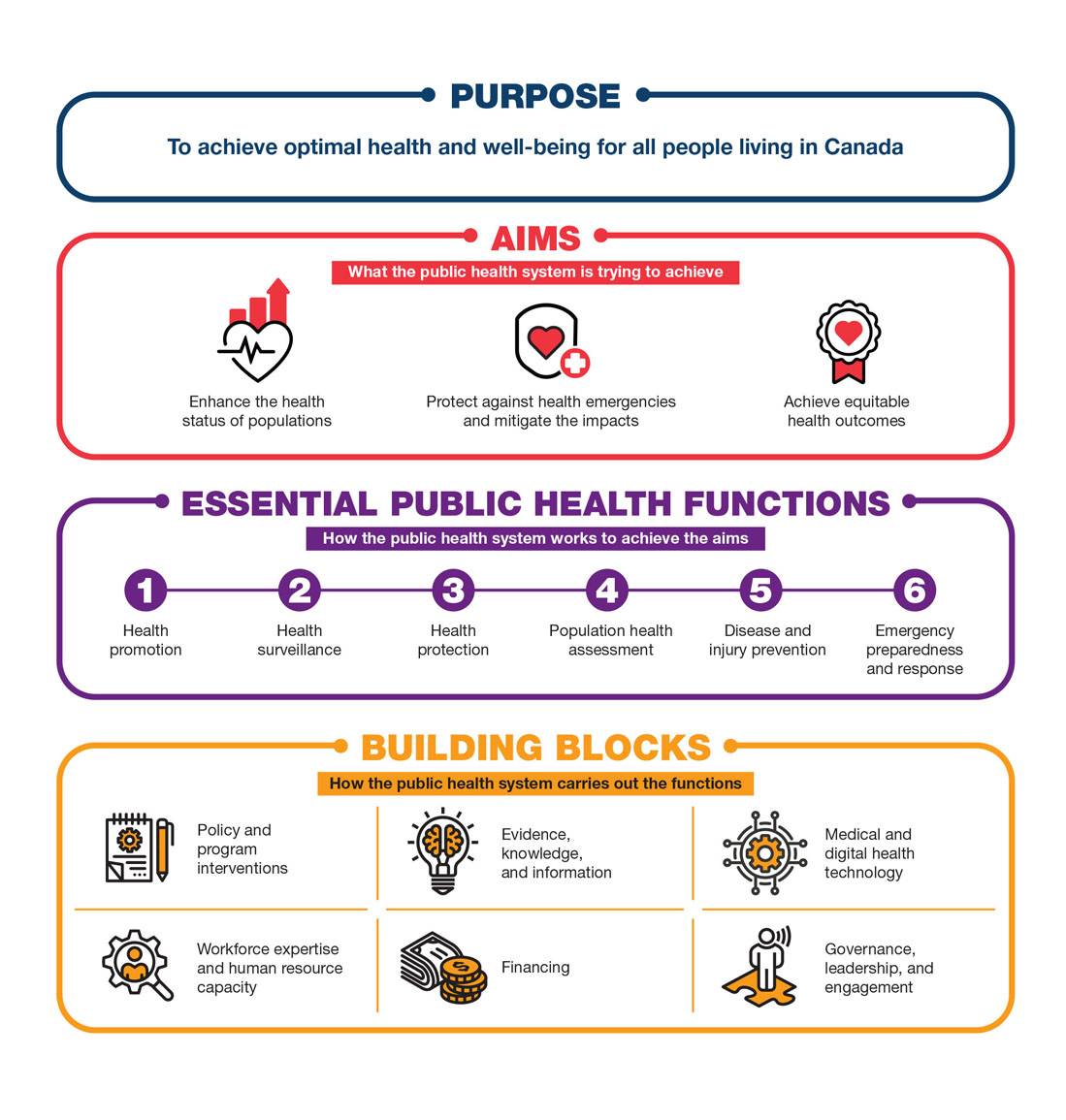

This year’s annual report of the Chief Public Health Officer of Canada (CPHO) examines the current state of public health in Canada. It describes the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and provides a forward-looking vision to transform Canada’s public health system, in order for it to excel and be better prepared for the next public health crisis.

Like SARS and H1N1 in the past, COVID-19 was a stress-test of our health, social, and economic systems. It underscored the critical importance of the public health system in protecting us from the potentially crippling effects of emerging viruses. This includes the vital role the system plays in helping to mitigate excessive pressure on healthcare resources.

As we continue to face evolving and worsening threats to human health, such as climate change, antimicrobial resistance, or the burden of non-communicable diseases, we need to ensure that our public health systems are better equipped to capably address these complex challenges.

This report builds on last year’s CPHO annual report From Risk to Resilience: An Equity Approach to COVID-19 which documented the unequal impacts of COVID-19 on the health of Canadians. It highlighted the need for stronger public health systems to keep people well and healthy, while contributing to a flourishing society.

This year’s report, A Vision to Transform Public Health in Canada, is divided into the following main sections:

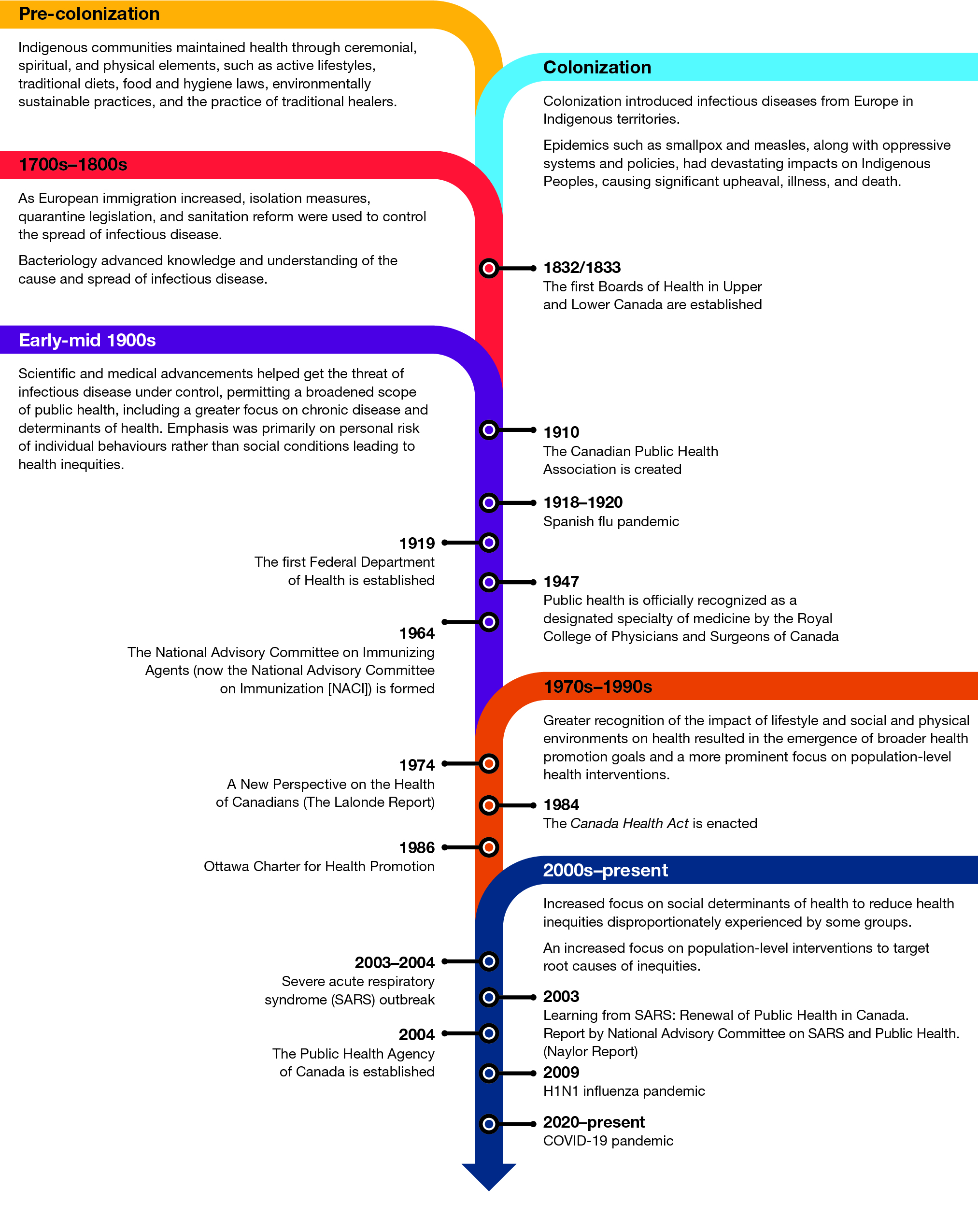

Section one sets the context with an overview of the key epidemiological COVID-19 events in Canada between August 2020 and August 2021. By illustrating inequities, broader pandemic impacts, and lessons learned, this section provides compelling evidence on the need to strengthen the public health system in Canada.

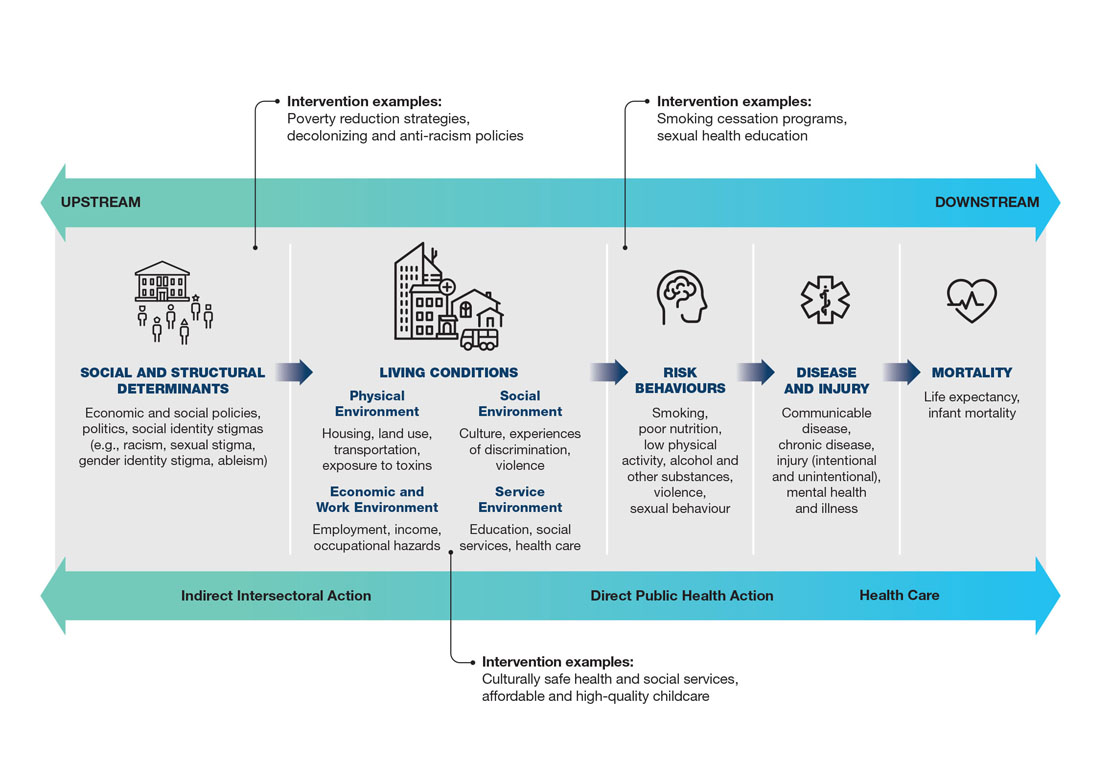

Section two describes the unique role and impact of public health systems on the health of populations. It presents the foundational building blocks of Canada’s system, and outlines the opportunities for system-level improvements.

Section three builds on these opportunities, to offer a vision of a world-class public health system. It then outlines the elements needed to achieve this vision and ensure that the conditions are in place for Canada to be ready for current and future public health challenges.

Note to the reader: This report was written with the knowledge that the COVID-19 pandemic and its impacts continue to evolve. Given the need to finalize the report well in advance of publication, it does not cover changes in epidemiology, emerging events, or implementation of additional public health measures beyond the end of August 2021. Further details on the methods and limitations are provided in Appendix A.

This report benefits from the leadership and expertise of many contributors. In particular 4 independent commissioned reports were prepared to inform its content, which will be available on the National Collaborating Centres for Public Health website:

- The experiences, visions, and voices of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples on the future of public health in Canada are reflected in a companion report entitled Visioning the Future: First Nations, Inuit, & Métis Population and Public Health, which was developed and led by Indigenous public health leaders, in collaboration with Indigenous scholars and national Indigenous organizations.

- The components, approaches, and overarching factors to support a pan-Canadian public health data system are summarized in a companion report entitled An Evidence-Informed Vision for a Public Health Data System in Canada, which was developed by Dr. David Buckeridge.

- Opportunities to strengthen, improve, or transform existing public health governance are discussed in a companion report entitled Governing for the Public’s Health: Governance Options for a Strengthened and Renewed Public Health System in Canada, which was led by Dr. Erica Di Ruggiero.

- Proposed key actions to better incorporate and support the capacity of communities beyond COVID-19 are presented in a companion report entitled Strengthening Community Connections: The Future of Public Health is at the Neighbourhood Scale, which was developed by Dr. Kate Mulligan.

Finally, also available is a “What We Heard” report, entitled A Renewed and Strengthened Public Health System in Canada that provides a summary of discussion groups and key informant interviews conducted to inform the development and drafting of this report.

We respectfully acknowledge that the land on which we developed this report is in traditional First Nation, Inuit, and Métis territory, and we acknowledge their diverse histories and cultures. We strive for respectful partnerships with Indigenous Peoples as we search for collective healing and true reconciliation. Specifically, this report was developed in Ottawa, on the traditional and unceded territory of the Algonquin Anishnaabe people; in Halifax, on the ancestral and unceded territory of the Mi’kmaq people; in Montreal, on the traditional and unceded territory of the Mohawk (Kanien’kehá:ka) Nation; and in Toronto, on the traditional territory of the Wendat, the Anishnaabeg, Haudenosaunee, Métis, and the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation.

Section 1. COVID-19 in Canada and the world

COVID-19 pandemic in Canada

Overview of COVID-19 epidemiology

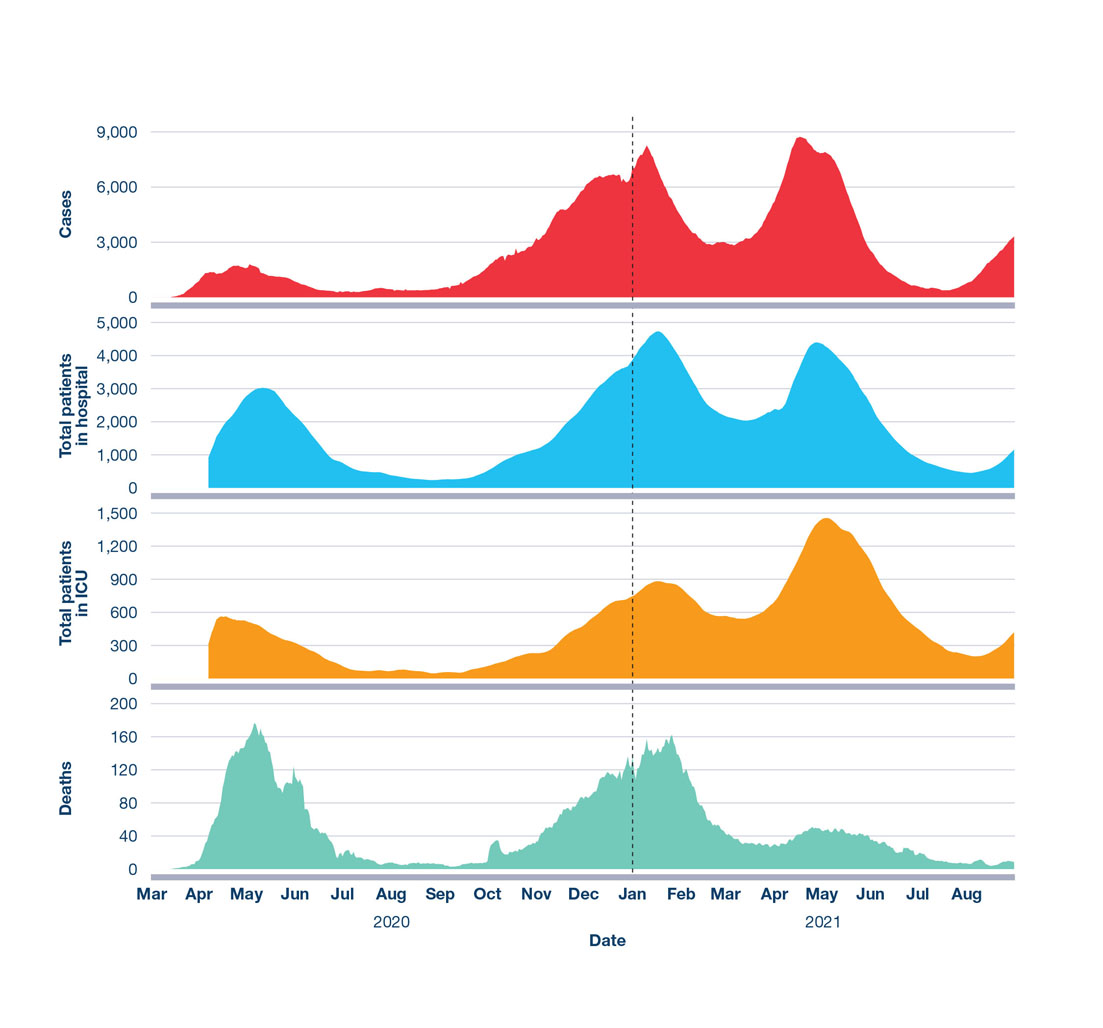

The COVID-19 pandemic remains one of the most significant public health crises in recent memory. As of August 31, 2021, there were about 1,500,000 reported COVID-19 cases and close to 27,000 COVID-19-related deaths in CanadaFootnote 1. COVID-19 was estimated to be the third leading cause of death in 2020, following only cancer and heart diseaseEndnote i Footnote 2. This marks the first time since the mid-20th century that an infectious disease has ranked among the top 3 causes of death in CanadaFootnote 3 Footnote 4. The 2020 CPHO Annual Report detailed the early epidemiology of the COVID-19 crisis until the end of the first wave in August 2020Footnote 5. Since that time, Canada has experienced additional waves, including one in the winter of 2020-21 and another in the spring of 2021Endnote ii. As of August 2021, at the time of writing this report, rising incidence signalled the beginning of a fourth waveFootnote 6. Figure 1 shows an overview of nationally reported COVID-19 cases and related outcomes, such as daily number of patients in hospital, daily number of intensive care unit (ICU) patients, and deaths in Canada for the period of March 2020 to August 2021Footnote 1.

Figure 1: Text description

The figure is an overview of Canada’s COVID-19 pandemic from March 2020 to August 2021. The vertical axes display 4 different indicators as 7-day moving averages of daily data by reported date in separate panels, from top to bottom: cases, total patients in hospital, total patients in ICU, and deaths. The horizontal axis displays elapsed time in months.

| Date (selected time points) | Cases | Deaths | Total patients in hospital | Total patients in ICU |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020-03-31 | 327.7 | 3.6 | Not available | Not available |

| 2020-04-30 | 1,427.1 | 88.9 | 1,939.0 | 514.0 |

| 2020-05-31 | 1,287.8 | 134.3 | 2,788.1 | 420.0 |

| 2020-06-30 | 491.0 | 55.0 | 1,398.3 | 219.7 |

| 2020-07-31 | 380.2 | 12.5 | 525.5 | 76.1 |

| 2020-08-31 | 398.7 | 6.5 | 287.1 | 65.7 |

| 2020-09-30 | 877.6 | 5.6 | 314.0 | 70.8 |

| 2020-10-31 | 2,329.1 | 24.9 | 890.5 | 177.9 |

| 2020-11-30 | 4,462.1 | 61.8 | 1,730.2 | 337.8 |

| 2020-12-31 | 6,456.4 | 107.9 | 3,234.5 | 637.0 |

| 2021-01-31 | 6,657.2 | 141.5 | 4,376.8 | 841.8 |

| 2021-02-28 | 3,295.6 | 78.6 | 2,836.8 | 655.1 |

| 2021-03-31 | 3,494.9 | 32.8 | 2,131.6 | 578.0 |

| 2021-04-30 | 7,628.2 | 39.8 | 3,423.8 | 1,072.6 |

| 2021-05-31 | 5,747.8 | 44.2 | 3,610.2 | 1,321.0 |

| 2021-06-30 | 1,321.7 | 26.5 | 1,577.6 | 706.3 |

| 2021-07-31 | 496.0 | 10.8 | 638.0 | 306.5 |

| 2021-08-31 | 1,966.8 | 7.7 | 671.3 | 265.0 |

Note that the vertical axes for each variable are differently scaled. All variables are 7-day moving averages of daily data by reported date. Complete hospitalization and ICU data are unavailable before April 2020Footnote 1.

The patterns of principal disease severity indicators changed over time. Compared to the first wave and despite significantly higher case counts, a smaller proportion of the total number of people with COVID-19 died, were hospitalized, or were admitted to ICU in the second and third waves (Table 1)Footnote 1. It is important to note that, once better testing and surveillance infrastructure became available after the first wave, the detection of mild and asymptomatic cases was more likelyFootnote 7. In addition to changes in testing, another factor that influenced this trend is better protection of those at higher risk of the most severe outcomes, such as residents of long-term care facilities, by enhanced public health interventions and targeted vaccination programs (further described below).

However, as a result of the prolonged high incidence and, therefore, the high number of ICU admissions (Figure 1), the third wave greatly challenged ICU capacity, especially in the most populous provincesFootnote 8. In some provinces, patients had to be transferred to other regions in response to overcrowded treatment settings, and many areas reduced or postponed elective medical procedures and surgeriesFootnote 8.

| COVID-19 indicators | Total number 1st wave (Jan 2020 – Aug 2020) |

Total number 2nd wave (Aug 2020 – Feb 2021) |

Total number 3rd wave (Feb 2021 – Aug 2021) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | 126,707 | 751,158 | 640,293 |

| Males | 57,107 (45%) | 369,989 (49%) | 327,180 (51%) |

| Females | 69,383 (55%) | 380,177 (51%) | 311,806 (49%) |

| Other | 14 (<1%) | 56 (<1%) | 82 (<1%) |

| Case median age (range) | 47 years (0 to 119) | 37 years (0 to 115) | 33 years (0 to 113) |

| Deaths | 9,363 (7%) | 13,573 (2%) | 4,463 (1%) |

| Males | 4,294 (46%) | 6,931 (51%) | 2,627 (59%) |

| Females | 5,054 (54%) | 6,625 (49%) | 1,822 (41%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Death median age (range) | 86 years (0 to 112) | 85 years (0 to 109) | 75 years (1 to 105) |

| Hospitalizations | 13,428 (11%) | 36,251 (5%) | 29,920 (5%) |

| Males | 6,865 (51%) | 19,296 (53%) | 16,401 (55%) |

| Females | 6,554 (49%) | 16,924 (47%) | 13,477 (45%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 2 (<1%) | 3 (<1%) |

| Hospitalizations median age (range) | 73 (0 to 106) | 71 (0 to 108) | 59 (0 to 107) |

| ICU admissions | 2,733 (2%) | 5,996 (1%) | 6,557 (1%) |

| Males | 1,740 (64%) | 3,798 (63%) | 4,024 (61%) |

| Females | 993 (36%) | 2,191 (37%) | 2,524 (38%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| ICU admissions median age (range) | 65 (0 to 99) | 66 (0 to 104) | 59 (0 to 99) |

| This data may be influenced by variation in testing approaches over time as well as between regions. In addition, some evidence suggested that COVID-19-related deaths were undercounted in the spring and fall of 2020Footnote 9. The denominator for the deaths, hospitalizations, and ICU admissions percentages is the total number of reported cases. For each disaggregation by gender/sex the denominator is the total number for each respective indicatorFootnote 1. | |||

Each wave of the pandemic in Canada has been marked by key characteristics (summarized in Table 2). This section describes some of the main epidemiological features of the pandemic, with a primary focus on the period between August 2020 and August 2021.

| Time period | Brief description of key characteristics |

|---|---|

1st wave (Jan 2020 – Aug 2020) |

|

2nd wave (Aug 2020 – Feb 2021) |

|

3rd wave (Feb 2021 – Aug 2021) |

|

4th wave (began Aug 2021) |

|

| For references and more detail on these topics, refer to the following content. The details of this section were finalized in August 2021; therefore, the included data do not represent a complete review of the fourth wave. | |

Second wave: August 2020 – February 2021

Easing of public health measures fuelled epidemic growth

By the summer of 2020 at the end of the first wave, nationally reported COVID-19 cases had declined to low levels (Figure 1)Footnote 1. Although there was variation among jurisdictions, many of the most restrictive public health measures implemented as part of Canada’s initial pandemic response, such as closures of businesses, workplaces and schools, stay-at-home orders, cancellation of public events, and restrictions on social gatherings, were relaxed. International border protocols, case detection and isolation, and contact tracing, as well as advice around individual personal preventive practices and population-based measures to reduce contacts, remained in placeFootnote 10.

Canadians’ increasing contact rates amplified the spread of the virus by the fall of 2020Footnote 11. At the time, mathematical modelling predicted that, if these rates of contact were maintained, the epidemic could quickly resurge with higher case countsFootnote 11. This was an early warning indicator for the large second wave that began at the end of August 2020, and peaked nationally in January 2021 (Figure 1)Footnote 1. While long-term care facilities continued to be the most frequent outbreak setting, social gatherings and workplace outbreaks greatly contributed to community spread in the second wave, especially as infection rates increased among younger, more socially active and mobile age groups with higher contact ratesFootnote 12.

In the winter of 2020-21, in response to surging numbers of cases and hospitalizations (Figure 1), many areas of the country reintroduced more restrictive public health measuresFootnote 10. With the resulting decline in cases to less than half of the daily number peak observed in January 2021, many regions eased restrictions by March 2021 before tightening them once again in April 2021Footnote 8. This was in line with modelling forecasts that accurately predicted another surge in cases that would become the third waveFootnote 13.

Public health measures were the primary tools available to limit spread

During most of the second wave, public health measures continued to be the primary means to manage the epidemic in Canada, since effective pharmaceutical interventions (e.g., vaccines) were not yet widely available. Implemented measures included a range of interventions to reduce community transmission of SARS-CoV-2 with the goal of “minimizing serious illness and overall deaths while minimizing societal disruption”Footnote 14. These encompassed both individual practices (e.g., masks, physical distancing, hand hygiene) and population-based measures (e.g., case management and contact tracing, school and business closures, stay-at-home orders)Footnote 15. It was difficult to mitigate the social, psychological, and economic consequences of public health measures, while also reducing transmission by limiting community-wide contact rates. In addition, some individuals had limited ability to follow recommendations as a result of their health, age, economic, or social circumstancesFootnote 15.

Public health authorities at federal, provincial/territorial, and local levels adapted public health measures as new scientific evidence and expert opinion from Canadian and international researchers became available. For instance, outbreak investigations and scientific studies revealed that SARS-CoV-2 can spread via respiratory droplets that vary in size, from large droplets that fall to the ground rapidly near the infected person, to smaller droplets, called aerosols, that linger in the air in some circumstancesFootnote 16. Short-range aerosol transmission was suggested to be particularly relevant for poorly ventilated indoor crowded spacesFootnote 16. As a result, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) updated guidance on the construction, fit, and proper wearing of face masks and on improving indoor ventilation during the second waveFootnote 17 Footnote 18 Footnote 19. National guidance on public health measures was based on pan-Canadian pandemic planning that jurisdictions adapted to their local epidemiological context, such as using curfews or designating more granular regional zones, to tailor approaches specific to the local areaFootnote 10 Footnote 14.

The pandemic response required rapid adoption and broad acceptance of public health measures, with consistent and sustained adherence for extended periods of time. Many Canadians reported high adherence to, and support of the use of, measures to limit the spread of the virusFootnote 20 Footnote 21 Footnote 22 Footnote 23. For example, a survey conducted by Impact Canada in March 2021 indicated that the vast majority of respondents were “always” or “almost always” complying with measures, such as mask wearing, hand washing, and physical distancingFootnote 24. Statistical modelling indicated that the strongest factors driving adherence to public health measures include anxiety related to family’s health, trust in government sources, and trust in medical expertsFootnote 25.

A variety of non-traditional data sources provided insight into overall adherence to public health measures that aimed to reduce movement and contact with others. For example, mobility data gathered from cellular networks showed that there was a significant decrease in the proportion of time Canadians spent at home after the first wave, which appears to align with the relaxation of public health measuresFootnote 10. While there were a variety of factors that influenced adherence to public health measures, it is important to note that some people had higher mobility and more contact with others regardless of the measures, due to factors such as essential work or high-density housing arrangements, respectivelyFootnote 26.Third wave: February 2021 – August 2021

Highly transmissible variants of concern contributed to rapid epidemic growth

Following a decline in average daily cases nationally from January through February 2021, infection rates rose sharply in March 2021 in most provinces and territories (Figure 1)Footnote 1. This was driven by increased contact rates following the easing of restrictions and the emergence and spread of more contagious virus variants of concernFootnote 13. As with all viruses, SARS-CoV-2 accumulates genetic mutations over time. Some of them may lead to virus variants that are considered to be variants of concern because they spread more easily, cause more severe illness, or decrease the effectiveness of available diagnostics, vaccines, therapeutics, or public health measuresFootnote 27. In early 2021, more contagious virus variants began to be detected in Canada, and as of August 2021, included the Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta variants. These variants of concern had spread to most provinces and territories and were responsible for about 80% of all cases in August 2021Footnote 28. While Alpha initially accounted for the majority of national COVID-19 cases at the beginning of the third wave, in early July 2021, Delta replaced Alpha as the most frequently reported variantFootnote 28.

Early evidence from Ontario suggested that, compared to the original strain of SARS-CoV-2, the Alpha variant was associated with a 62% increase in hospitalizations, a 114% increase in ICU admissions, and a 40% increase in deaths, among those infectedFootnote 29. Preliminary findings indicated that the Delta variant was more transmissible and also more virulent than the Alpha variantFootnote 30.

International border measures were deployed and adjusted over time as knowledge of SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern evolved. Throughout the pandemic, air and land traveller volumes remained at less than 90% of pre-pandemic levelsFootnote 31. To further reduce the risk of virus importation, especially variants of concern, Canada implemented enhanced testing and quarantine measures at international borders, in addition to those already in place, beginning in the winter of 2020-21. These included mandatory testing before departure and in-Canada for all non-exempt travellers, as well as a 3-day mandatory hotel stopover in a government-approved accommodation for non-exempt travellers arriving by air at the 4 main airports permitting international arrivalsFootnote 32.

In early 2021, Canada quickly increased surveillance and genomic sequencing efforts to detect known and emerging variants of concernFootnote 33. PHAC worked with partners at all levels of government as well as academic researchers to establish a pan-Canadian surveillance network that used new genetic assays to detect SARS-CoV-2 variants from wastewater samplesFootnote 34. This acted as part of a system of early warning indicators, in combination with predictions from mathematical models, which facilitated the adaptation of the COVID-19 response to evolving information. For example, in the Northwest Territories, a positive COVID-19 signal in wastewater led to the identification of an infected individual, prompting wider community testing. This rapid response allowed for the early detection of additional COVID-19 cases, which interrupted further spread and potentially prevented a larger outbreakFootnote 34.

COVID-19 vaccines as vital tools to control the virus

Towards the end of 2020, less than a year after the emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, researchers developed the first safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines – a feat unprecedented in scientific history. This marked a turning point in the response to the pandemic. These vaccines were the result of collaboration of academic and private sector researchers around the world and increased funding that, together, enabled them to build on scientific and technological advancements made over the past decadeFootnote 35. For information on how vaccines protect populations, see text box “Vaccines provide protection for everyone through enhanced community protection”.

On December 9, 2020, Canada authorized the first COVID-19 vaccine, which uses novel messenger RNA (mRNA) technology, for use in adults in CanadaFootnote 36. Subsequent vaccine authorizations included another mRNA-based vaccine as well as viral vector-based vaccines. At the time, most required 2 doses for the best possible protectionFootnote 37. Rapid authorization was supported by the ability of Health Canada to review new evidence as it became available, and the dedication of more scientific resources to the vaccine safety and efficacy review processFootnote 38 Footnote 39. Vaccine safety assessment and monitoring is an ongoing process throughout a vaccine’s life cycle (see text box “Creation of the Vaccine Injury Support Program”). As of August 31, 2021, over 53 million doses of safe and highly effective vaccine products had been administered in CanadaFootnote 40.

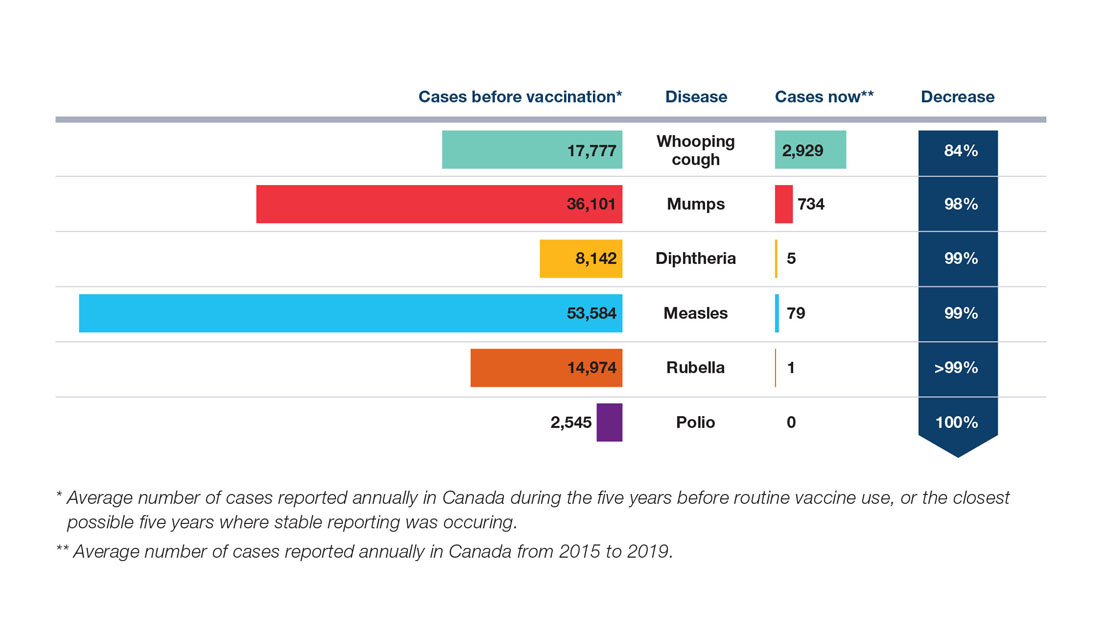

Vaccines provide protection for everyone through enhanced community protection

Vaccines are one of the most important preventive health interventions for many serious infectious diseases. They can provide both direct protection for vaccinated individuals as well as indirect protection for a community. The higher the proportion of people vaccinated, the less opportunity a pathogen has to circulate, thereby minimizing the risk of larger outbreaks. High community vaccination rates further protect those who cannot be vaccinated, or who are not as well protected by vaccination, and reduce the opportunities for the pathogen to mutateFootnote 41. This enhanced community-level protection is especially important for those at highest risk of severe health outcomes, including hospitalization and death. Mass vaccination is one of the most effective ways to protect the population against COVID-19Footnote 42.

The distribution and administration of COVID-19 vaccines was the largest and most complex vaccination program Canada has ever implemented. The federal government took on the responsibility of procuring vaccines, overseeing logistics, coordinating surveillance, and working very closely with provincial/territorial governments, as well as public health partners, to ensure a timely, fair, and well-coordinated rolloutFootnote 43.

Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) provided independent expert advice to support the provinces and territories in prioritizing an initially limited supply of COVID-19 vaccines. NACI takes into consideration the broader, real-world context and the best evidence available at the time when making recommendationsFootnote 44. NACI identified the key populations for prioritization in Stage 1 of their Guidance on the Prioritization of Initial Doses of COVID-19 Vaccine(s) to be residents and staff of congregate living settings that provide care for seniors, adults aged 70 years or older, healthcare workers, and adults living in Indigenous communitiesFootnote 45. These populations were generally considered at greatest risk of severe illness and in most urgent need of protection. Before offering vaccines to the general population as vaccine supply increased, NACI recommended that Stage 2 of the vaccine rollout include healthcare workers not part of Stage 1, residents and staff of all other congregate settings, and essential workersFootnote 45. In March 2021, based on emerging evidence of the degree of protection provided by one dose, NACI recommended that jurisdictions extend the interval for those vaccines requiring a second dose to maximize the number of people with some protection and reduce transmission in the context of limited initial vaccine supplyFootnote 46. Provincial and territorial governments, who were responsible for delivering and administering vaccines, largely adopted NACI’s recommendations.

Creation of the Vaccine Injury Support Program

All vaccines authorized for use in Canada meet the highest standards for safety and efficacyFootnote 47. As with any medication, vaccines may cause reactions and side effects. Severe adverse events are very rare, but they do occurFootnote 47. PHAC created the federal Vaccine Injury Support Program to offer fair and timely compensation to Canadians who have experienced a serious and permanent injury as a result of receiving any Health Canada-authorized vaccine administered in Canada on or after December 8, 2020Footnote 47 Footnote 48. This no-fault program builds on a program that Quebec has had in place for over 30 years and brings Canada in line with other Group of Seven (G7) countriesFootnote 47. Vaccine injury compensation can also support vaccine innovation and procurement by reducing legal risks for manufacturersFootnote 49.

Once initial vaccine supply limitations were overcome, vaccine delivery rapidly accelerated beginning in the spring of 2021. Beneficial vaccine impacts became readily apparent in prioritized populations, such as among long-term care facility residents and people who work in healthcare settings, who saw significant decreases in COVID-19 cases as vaccine coverage increasedFootnote 50. Early evidence showed that COVID-19 vaccines are highly protective, especially at preventing severe outcomes. Between July 18, 2021 and August 14, 2021, data from 11 provinces and territories revealed that the average rate of new COVID-19 cases was 12 times higher among unvaccinated people, and the rate of COVID-19 hospitalizations was 36 times higher among unvaccinated people than in fully vaccinated individualsFootnote 51. Strengthened public health measures in combination with increasing vaccination coverage brought COVID-19 activity to low levels in most areas of Canada by July 2021 (Figure 1)Footnote 52. This also allowed for Canada to begin a phased approach to easing border measures for fully vaccinated travellersFootnote 53.

Disproportionate impacts of the second and third waves of the pandemic

The second and third waves of the pandemic looked different from the first wave. Some areas and populations faced continued difficulties and/or new challenges. Evolving science and lessons learned led to jurisdictions adapting their public health response, which changed the dynamics of subsequent waves. This section will discuss some of the key observations made during later waves, including the continued disproportionate impact on Canadians who experienced poorer health, social, and economic circumstances prior to the pandemic due to pre-existing inequitiesFootnote 14.

COVID-19 spread differently across the country

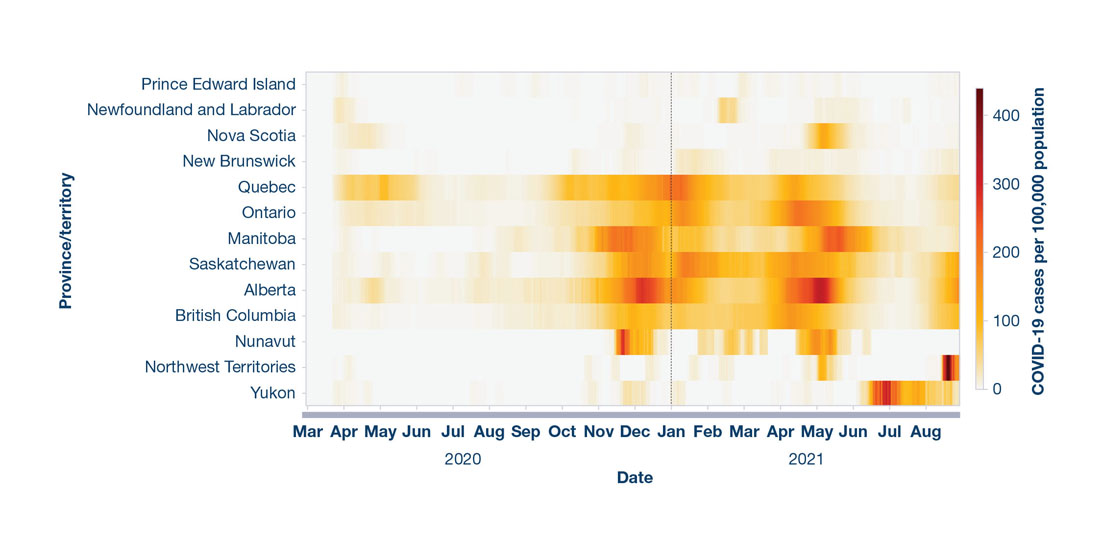

In contrast to the first wave, subsequent waves of the pandemic were felt all across the country. However, not all regions experienced distinct second and third waves at the same time or with the same intensity (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Text description

The figure is a heat map describing the rate of COVID-19 cases per 100,000 population for each province/territory over time from March 2020 to August 2021. The 2 vertical axes display the number of COVID-19 cases per 100,000 population and by province or territory, respectively. The horizontal axis displays elapsed time in months. A colour gradient using light (i.e., low) to dark (i.e., high) shading indicates rate changes over time.

| Date (selected time points) | NU | NT | YT | BC | AB | SK | MB | ON | QC | NB | PE | NS | NL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020-03-31 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 6.2 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 4.7 |

| 2020-04-30 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 4.0 | 5.3 | 21.7 | 4.6 | 3.5 | 21.6 | 61.0 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 18.9 | 6.4 |

| 2020-05-31 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 11.6 | 5.3 | 0.4 | 18.4 | 64.9 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 3.6 | 0.1 |

| 2020-06-30 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 5.3 | 2.6 | 0.5 | 12.1 | 15.1 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| 2020-07-31 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 2.8 | 12.8 | 8.8 | 1.3 | 6.7 | 9.8 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| 2020-08-31 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 8.5 | 15.1 | 7.2 | 11.6 | 4.7 | 8.6 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| 2020-09-30 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 15.1 | 21.9 | 5.2 | 12.8 | 12.7 | 26.6 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| 2020-10-31 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 3.8 | 22.0 | 45.8 | 20.1 | 48.6 | 35.2 | 81.7 | 4.0 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.8 |

| 2020-11-30 | 96.1 | 2.9 | 11.1 | 77.2 | 142.6 | 93.9 | 183.6 | 60.7 | 96.1 | 4.1 | 1.0 | 3.9 | 1.8 |

| 2020-12-31 | 59.3 | 4.5 | 9.6 | 86.1 | 229.7 | 138.7 | 139.0 | 96.1 | 148.9 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 4.8 | 2.5 |

| 2021-01-31 | 10.7 | 3.5 | 5.4 | 69.2 | 124.2 | 157.1 | 81.6 | 135.5 | 168.2 | 17.5 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 0.7 |

| 2021-02-28 | 44.2 | 6.1 | 1.2 | 61.3 | 54.1 | 108.0 | 45.4 | 59.3 | 77.7 | 7.3 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 27.0 |

| 2021-03-31 | 23.6 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 81.3 | 70.9 | 91.8 | 36.9 | 69.8 | 60.4 | 4.4 | 5.0 | 1.9 | 2.1 |

| 2021-04-30 | 46.0 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 134.5 | 205.3 | 146.5 | 69.4 | 173.1 | 104.7 | 8.9 | 3.1 | 11.9 | 2.1 |

| 2021-05-31 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 11.6 | 5.3 | 0.4 | 18.4 | 64.9 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 3.6 | 0.1 |

| 2021-06-30 | 6.2 | 0.4 | 110.0 | 18.1 | 28.8 | 48.1 | 99.2 | 25.1 | 14.3 | 4.3 | 0.7 | 8.0 | 4.2 |

| 2021-07-31 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 158.1 | 8.7 | 10.8 | 21.1 | 25.8 | 8.7 | 6.6 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 2.3 |

| 2021-08-31 | 0.0 | 134.7 | 57.9 | 64.3 | 81.8 | 71.7 | 17.3 | 21.0 | 28.2 | 10.9 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 1.4 |

| Provinces/Territories listed in table are abbreviated using the alpha code. | |||||||||||||

Daily data are shown by province and territory and by reported dateFootnote 54.

National incidence rates were driven by the provinces west of the Atlantic region, partly due to population size and densityFootnote 54. Since the first wave, the Atlantic provinces were largely able to sustain sufficient measures (e.g., interprovincial travel restrictions) to manage and limit case importations, interrupt spread, and maintain strong control of COVID-19 (Figure 2)Footnote 55 Footnote 56 Footnote 57. However, there were surges that provincial governments quickly interrupted with rapid implementation of stringent public health measures to prevent further spread. These measures were particularly important given limited health system capacity in some of these jurisdictions.

Other regions that had relatively low COVID-19 rates in the first wave saw an increase in disease activity after the summer of 2020. For example, while the territories had no to very few cases initially, by late 2020, some communities experienced a rapid rise in cases, with community transmission following importation of the virus (Figure 2)Footnote 54. This necessitated fast implementation of stringent public health measures locally and territorially to prevent further spread. The territories, whose communities were prioritized in the initial vaccination rollout, achieved high vaccine uptake and, as of July 20, 2021, 84% of adults aged 18 years or older had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine and 76% were fully vaccinatedFootnote 40. The territories’ early success in expanding vaccine coverage was supported by prioritized allocation of vaccines that were somewhat easier to transport and store as well as robust community-level outreach and leadershipFootnote 58 Footnote 59 Footnote 60.

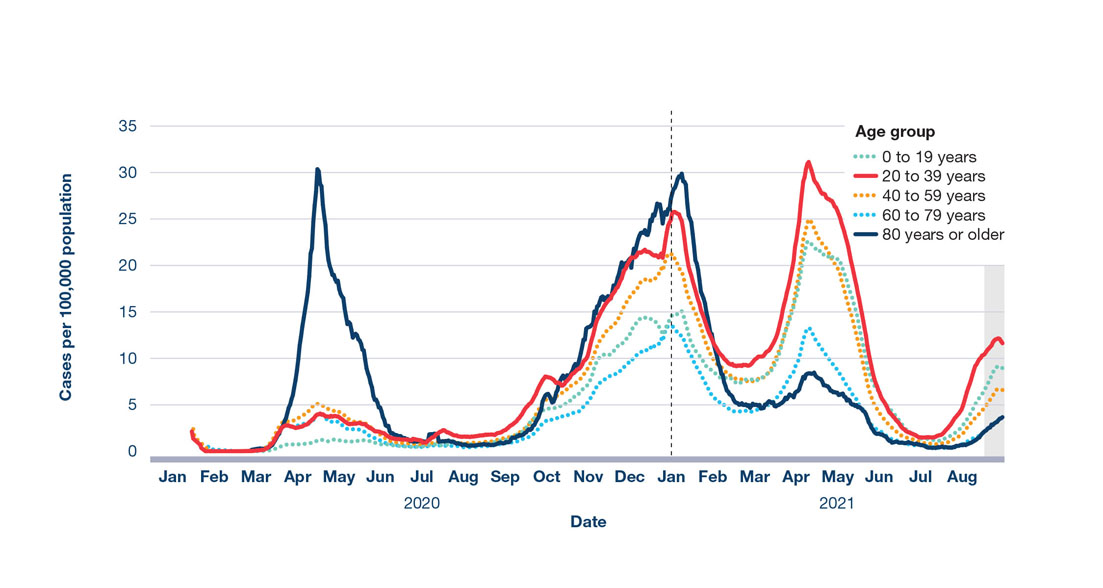

Shift towards spread in younger Canadians

As older Canadians became better protected through public health measures, adaptation of the COVID-19 response in long-term care facilities, and ultimately, high vaccination rates, the median age of COVID-19 cases dropped (Table 1)Footnote 1. Until the end of the second wave, Canadians aged 80 years or older had the highest national incidence rate. However, starting in early 2021, incidence rates in this age group decreased sharply. At the time of report writing in August 2021, Canadians aged 80 years or older had maintained the lowest incidence rates out of all age groups since March 2021 (Figure 3), largely as a result of high vaccine coverageFootnote 1. As of August 28, 2021, 93% of adults aged 80 years or older were fully vaccinated against COVID-19Footnote 40.

Figure 3: Text description

The figure is a line graph displaying the number of COVID-19 cases by date of illness onset and age group in Canada from January 2020 to September 2021. The vertical axis displays the number of cases (7-day moving average) per 100,000 population. The horizontal axis displays the date of illness onset in months. The age groups are represented by different coloured trend lines: green (0 to 19 years), red (20 to 39 years), orange (40 to 59 years), light blue (60 to 79 years), and dark blue (80 years or older). The 20 to 39 years and 80 years or older age groups are displayed as solid lines, respectively, to better indicate their trend change over time, versus dashed lines for all other groups.

| Date (selected time points) |

0 to 19 years | 20 to 39 years | 40 to 59 years | 60 to 79 years | 80 years or older |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020-01-31 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| 2020-02-29 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| 2020-03-31 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 2.2 |

| 2020-04-30 | 1.0 | 3.4 | 4.5 | 3.3 | 20.3 |

| 2020-05-31 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 11.4 |

| 2020-06-30 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.9 |

| 2020-07-31 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 1.2 |

| 2020-08-31 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| 2020-09-30 | 2.8 | 4.8 | 2.9 | 1.6 | 2.5 |

| 2020-10-31 | 5.6 | 8.2 | 6.8 | 4.0 | 8.4 |

| 2020-11-30 | 10.6 | 16.1 | 13.0 | 7.8 | 17.1 |

| 2020-12-31 | 13.8 | 21.6 | 18.7 | 11.3 | 24.2 |

| 2021-01-31 | 11.6 | 19.0 | 15.6 | 9.9 | 22.3 |

| 2021-02-28 | 7.8 | 9.7 | 8.3 | 4.7 | 6.6 |

| 2021-03-31 | 10.4 | 13.1 | 10.3 | 5.8 | 2.2 |

| 2021-04-30 | 20.9 | 27.7 | 22.0 | 11.1 | 7.4 |

| 2021-05-31 | 13.7 | 17.3 | 12.3 | 5.5 | 4.6 |

| 2021-06-30 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| 2021-07-31 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 2021-08-31 | 6.2 | 9.5 | 4.5 | 2.0 | 1.9 |

All variables are 7-day moving averages of daily data by date of illness onset. Shaded area indicates data uncertainty due to reporting lagFootnote 1.

Age is one of the most significant risk factors for developing severe COVID-19Footnote 61 Footnote 62. Despite the decrease in overall case burden, as of the end of August 2021, Canadians aged 80 years or older continued to have the highest rate of COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 population. However, this rate fell significantly after the second waveFootnote 1. Of the 15,300 people who died of COVID-19 in 2020, 89% had at least one other health condition listed on their death certificate. Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease were the most common conditions, followed by hypertensive disease, diabetes, and ischemic heart diseaseFootnote 63.

Emerging evidence also showed an increased rate of pre-term births and stillbirths among pregnant people with COVID-19Footnote 64. Compared to their non-pregnant counterparts, pregnant people testing positive for COVID-19 were 4 times more likely to be hospitalized and 11 times more likely to be admitted to the ICUFootnote 64.

One of the key differences between the first wave of the pandemic and subsequent waves was a shift to more widespread detection of community transmission in younger adults. Individuals aged 20 to 39 years, who generally have higher contact rates and thereby an increased risk of virus exposure, have had the highest incidence rate since February 2021 (Figure 3)Footnote 1. Although severe illness is less common in younger individuals, in the spring of 2021, the number of COVID-19 hospitalizations in individuals aged 40 to 59 years increasedFootnote 57. This was likely due to a combination of the shift in the age distribution of cases as a result of better protection of older age groups, the increased severity of some variants of concern, and the easing of public health measures.

Differential impact of COVID-19 across the sexes and genders

Since the summer of 2020, women and men accounted for an equal proportion of COVID-19 cases (Table 1)Footnote 1. This is in contrast to the first wave when women made up 55% of all cases, possibly due to their overrepresentation among healthcare workers and residents of long-term care facilities, and therefore an increased probability of being exposed to, and tested for, the virusFootnote 5. This could also explain the larger percentage of deaths in women during the first wave. During the second and third waves, these groups may have been better protected by improved access to personal protective equipment and vaccinesFootnote 65.

However, men comprised a larger percentage of hospitalized cases and ICU admissions throughout the pandemic as well as a larger percentage of deaths after the first wave (Table 1)Footnote 1. Researchers propose that fundamental biological differences mainly tied to immunology are a likely driver of the increased risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19 in males. Behavioural differences, such as men being more likely to smoke and less likely to seek health care, could also be possible influencing factorsFootnote 66 Footnote 67 Footnote 68 Footnote 69.

Variation in impacts across different outbreak settings

Long-term care facilities

Long-term care facilities remained a high-risk setting in many provinces and territoriesFootnote 8. However, the proportion of total COVID-19-related deaths associated with these facilities dropped from 79% during the first wave to 50% during the second and third wavesFootnote 1. Beginning in January 2021, the number and size of outbreaks in these settings steadily declined, largely due to the impact of vaccinationsFootnote 8.

Healthcare settings

In April 2020, 25% of all COVID-19 cases were in people who work in healthcare settingsFootnote 1. Due to improved infection control measures, vaccine prioritization, as well as wider community case detection outside healthcare settings, this proportion dropped to 3% by March 2021Footnote 1. People who work in healthcare settings represent a wide range of individuals including healthcare professionals and support workers, who experience varying risks of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in the workplace. For example, based on data from Ontario, Manitoba, and British Columbia, personal support workers had a 1.8 times greater risk compared to nurses and a 3.3 times greater risk compared to physicians of contracting COVID-19Footnote 70.

Congregate living and working conditions

Federal prisons reported a substantial increase in COVID-19 cases during the winter of 2020-21. While 13 out of 43 institutions experienced outbreaks during the second wave, 70% of the total 880 cases occurred at the country’s 2 largest penitentiaries, one in Manitoba and one in SaskatchewanFootnote 71. Indigenous Peoples were disproportionately impacted as a result of overrepresentation in the prison system in CanadaFootnote 71. Vaccinations were accelerated for people incarcerated in federal institutions and, as of August 8, 2021, 78% of this population had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccineFootnote 72.

Regional medical officers of health reported that workplace outbreaks became one of the most common drivers of transmission in some provinces and territories during the second and third wavesFootnote 73 Footnote 74 Footnote 75. Many jurisdictions experienced outbreaks at large employment sites where workers faced challenges in maintaining physical distancing. Many of these outbreaks required additional efforts to contain. For example, the Canadian Red Cross provided contact tracing in response to a COVID-19 variant of concern outbreak at a fly-in mine in Nunavut for employees who had left the work location and returned to homes across the countryFootnote 76. As in the first wave, several public health authorities reported large outbreaks at meat-processing plants during subsequent waves, some of which required temporary facility closuresFootnote 77 Footnote 78. This led several jurisdictions to prioritize vaccinations for food-manufacturing workersFootnote 79 Footnote 80.

Tracking workplace outbreaks at a provincial/territorial and national level was limited, but is necessary for the adoption of policy measures targeting specific industries and settings to limit future spreadFootnote 81. Some local authorities launched initiatives during the pandemic to collect this type of data. For example, Toronto Public Health began publicly posting the names of workplaces in active outbreaks that employ 20 people or more, and Ottawa Public Health required employers to report if 2 or more people in their workplace tested positive for COVID-19Footnote 82 Footnote 83.

COVID-19 burden disproportionately impacted certain communities

During the first wave, neighbourhoods in Canada in the highest ethno-cultural composition quintile had an age-standardized COVID-19 mortality rate 2 times higher than those in the lowest quintileFootnote 69 Footnote 84 Footnote 85. Similarly, Canadians living in areas in the lowest income quintile had twice the age-standardized COVID-19 mortality rate compared to Canadians living in areas in the highest quintileFootnote 69 Footnote 84. In both analyses, men had much higher mortality rates compared to womenFootnote 69 Footnote 84.

While these populations had differential exposure to SARS-CoV-2 due to factors such as essential work and living conditions, the reasons for the differences in mortality rates include long-standing socioeconomic differences in the distribution of underlying risk factors and access to health careFootnote 5 Footnote 86. While similar national data for the second and third waves were not available at the time of report writing, racialized communities and low-income groups in general were likely to continue experiencing higher rates of COVID-19 and severe outcomes in subsequent waves. This is a result of the fundamental inequities that predate the pandemic and continued disproportionate risk of SARS-CoV-2 exposure.

Seroprevalence data collected from blood donors in May 2021 indicated that racialized donors were more than twice as likely to have antibodies acquired through past COVID-19 infectionFootnote 87. Additionally, Toronto Public Health reported that, between May 20, 2020 and May 31, 2021, 73% of all individuals testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 identified with a racialized group, which usually make up 52% of the Toronto population. Similarly, 45% of reported cases were in individuals living in lower-income households, which represent 30% of the population of TorontoFootnote 88.

Recognizing that a possible inequitable allocation of vaccines threatened to exacerbate social and health inequities already intensified by the pandemic, in February 2021, NACI updated their initial guidance on the prioritization for COVID-19 vaccinations in Canada to include adults in racialized communities disproportionately affected by COVID-19Footnote 89. As with other national guidance, jurisdictions adapted these recommendations based on their own local context.

For instance, after analysis revealed unequal vaccine coverage across Ontario, likely as a result of complex institutional and social factors, the province diverted 50% of its vaccine supply to hotspots with the highest incidence of infection for 2 weeks in May 2021Footnote 90. These neighbourhoods often had higher concentrations of racialized and low-income populations as well as the highest proportion of essential workers.

Place-based targeting of vaccines (e.g., geographic hotspots) also needed to be accompanied by initiatives directly aimed at confronting social inequitiesFootnote 91. For example, the Health Association of African Canadians, the Association of Black Social Workers, and African Nova Scotian Affairs, along with community leaders, hosted vaccine clinics for members of African Nova Scotian communitiesFootnote 92. Additionally, many urban centres, including Montreal and Vancouver, prioritized vaccines for people experiencing homelessness in January 2021 and used targeted strategies to increase vaccine uptake in this populationFootnote 93 Footnote 94.

COVID-19 and Indigenous communities

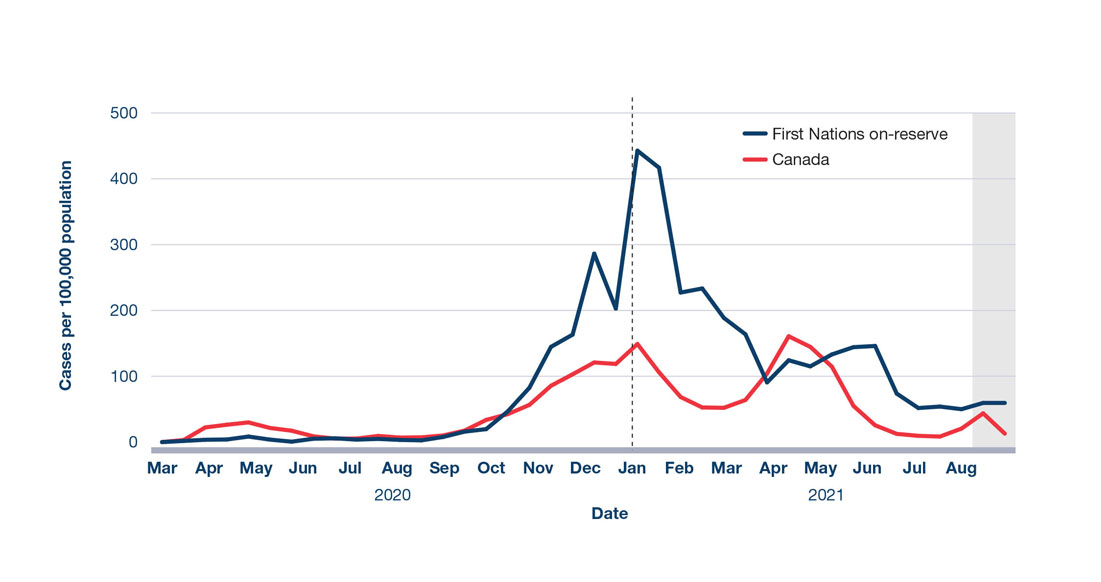

During the first months of the pandemic, First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities swiftly took control of the response and worked collaboratively to successfully limit the spread of COVID-19Footnote 5. As in many areas of Canada, case numbers rose rapidly in many Indigenous communities during the second waveFootnote 95.

Given the intersection of social and economic challenges, and the lasting and ongoing impacts of intergenerational trauma and systemic oppression, Indigenous communities in general were at high risk for rapid spread of COVID-19 and potentially more severe outcomes compared to the general Canadian population. Difficulties included inadequate and crowded housing, geographic isolation, and reduced access to health and critical care servicesFootnote 5.

At the peak of the second wave in January 2021, the rate of new COVID-19 cases in First Nations living on-reserve was triple the rate in the general Canadian population (Figure 4)Footnote 95. Statistics on First Nations individuals who do not live on-reserve were unavailable nationally. However, regional evidence suggested that the COVID-19 burden may have been higher for those individuals residing off-reserve compared to those living on-reserve. For example, as of August 14, 2021, individuals that live off-reserve represented 56% of First Nations COVID-19 cases in British ColumbiaFootnote 96.

After successfully preventing any case importations during the first wave, Nunavut, whose population is 85% Inuit, reported its first COVID-19 case in November 2020 (Figure 2)Footnote 54 Footnote 97. The territory swiftly interrupted further outbreaks and prevented resurgences through targeted public health measures, including proactive wastewater surveillance testing and territorial travel restrictionsFootnote 98 Footnote 99 Footnote 100. As of August 31, 2021, Nunavut’s last reported case of COVID-19 occurred in June 2021, and the territory had administered at least one vaccine dose to 80% of the eligible populationFootnote 54 Footnote 60.

First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities were prioritized for vaccines and demonstrated strong leadership in administering vaccination programs. Community groups, Indigenous governments, and leaders reacted quickly to set up clinics and provide culturally adapted educational materialsFootnote 101 Footnote 102 Footnote 103. Initiatives to safely and effectively deliver vaccines were implemented, such as Operation Remote Immunity, led by Ontario’s Ornge air ambulance service in partnership with Nishnawbe Aski Nation that provided vaccinations to 31 remote First Nations communities in the provinceFootnote 104.

Given prior experiences of stigmatization and racism, First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples in Canada expressed a desire for knowledge and understanding of vaccine risks and benefits to come from trusted sources and for interventions to be specifically tailored to community needs and cultural practicesFootnote 105 Footnote 106. One such example was the partnership between the Indigenous Primary Health Care Council and the National Reconciliation Program at Save the Children for leading an Indigenous youth vaccine advocacy program. Young people developed social media strategies to share their reasons for getting vaccinated under the hashtags #IndigenousYouth4Vaccine and #SmudgeCOVIDFootnote 107. As of August 10, 2021, over 86% of individuals aged 12 years or older in First Nations, Inuit, and territorial communities had received at least one vaccine doseFootnote 95 Footnote 108.

Figure 4: Text description

The figure is a line graph displaying the rate of reported COVID-19 cases in First Nations Peoples living on-reserve compared to the general Canadian population from March 2020 to August 2021. The blue line displays the number of cases in First Nations Peoples on-reserve and the red line displays the number of cases for all of Canada. The vertical axis show cases per 100,000 population. The horizontal axis displays date of illness onset in months.

| Date (selected time points) |

First Nations on-reserve | Canada |

|---|---|---|

| 2020-03-31 | 1.8 | 8.5 |

| 2020-04-30 | 6.2 | 28.1 |

| 2020-05-31 | 2.2 | 19.4 |

| 2020-06-30 | 5.4 | 7.1 |

| 2020-07-31 | 4.3 | 7.4 |

| 2020-08-31 | 4.6 | 8.1 |

| 2020-09-30 | 17.8 | 25.6 |

| 2020-10-31 | 64.6 | 49.5 |

| 2020-11-30 | 154.0 | 94.3 |

| 2020-12-31 | 244.6 | 119.9 |

| 2021-01-31 | 362.2 | 107.8 |

| 2021-02-28 | 211.1 | 52.3 |

| 2021-03-31 | 127.2 | 84.1 |

| 2021-04-30 | 119.7 | 152.7 |

| 2021-05-31 | 138.7 | 84.8 |

| 2021-06-30 | 109.8 | 19.0 |

| 2021-07-31 | 52.9 | 9.0 |

| 2021-08-31 | 56.3 | 25.7 |

All variables are weekly data by date of illness onset. Shaded area indicates data uncertainty due to reporting lagFootnote 95.

Expected impact of vaccination on the fourth wave

At the time of report writing in August 2021, rising incidence signalled the beginning of a fourth wave (Figure 1). Driven primarily by the more contagious Delta variant, long-range modelling in July 2021 predicted that daily cases in the fall of 2021 could exceed previous wave peaks as many jurisdictions planned to move into the final phases of their reopening plansFootnote 30 Footnote 109.

As of August 28, 2021, 83% of the eligible population in Canada had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine and 76% were fully vaccinatedFootnote 40. Given ramp-up in vaccination coverage at the population level, the epidemiology and associated public health response for this wave was expected to be significantly different than in the past. Public health experts anticipated that transmission would be concentrated in areas with lower vaccine coverage and among children not yet eligible for vaccination as schools reopened for in-person learningFootnote 109.

Achieving high vaccination coverage across eligible populations was predicted to significantly reduce the severity profile of disease going forward. However, updated modelling in August 2021 showed that there was still the potential for healthcare capacity to be overwhelmed if less than 80% of the eligible population remained not fully vaccinated, especially among Canadians aged 18 to 39 years, and if additional easing of public health measures further increased contact rates. This was partly due to the elevated risk of hospitalization and ICU admission associated with the Delta variant, particularly in unvaccinated individualsFootnote 51.

In the summer of 2021, many jurisdictions focused on increasing vaccine uptake using more targeted campaigns (see text box “Supporting vaccine confidence in Canada”). Several regions also required proof of vaccination for certain groups or for participation in certain activitiesFootnote 109. For example, in August 2021, Quebec became the first province to announce that individuals would need to be adequately vaccinated (or granted an exemption for medical reasons) to access some non-essential servicesFootnote 110. Alberta Health Services also announced plans to require all employees and contracted healthcare providers to be fully vaccinatedFootnote 111.

Supporting vaccine confidence in Canada

National survey results from September to December 2020 found that 77% of Canadians aged 12 years or older reported being “somewhat” or “very willing” to receive the COVID-19 vaccineFootnote 112. By February 2021, after the administration of vaccines was underway, this percentage rose to 82%Footnote 113. Reported reasons for vaccine hesitancy are multifaceted, including concerns about vaccine safety and effectiveness, the accessibility of vaccination services, and mistrust of the vaccine approval processFootnote 105 Footnote 114 Footnote 115 Footnote 116. Overcoming vaccine hesitancy is critical to the ongoing management of COVID-19, since achieving high vaccine coverage is necessary to limit future outbreaks. In recognition of this, many communities and businesses, as well as all levels of government, considered opportunities to support vaccine uptake. One example of an initiative to encourage vaccine uptake and vaccine confidence is the Vaccine Community Innovation Challenge. Through this initiative, the Government of Canada selected up to 140 creative projects that will develop and execute information campaigns to empower community leaders to increase people’s confidence in COVID-19 vaccines and reinforce public health measures targeted at populations that were more greatly impacted by the pandemicFootnote 117. This challenge is one of several programs, including others that were part of the Immunization Partnership Fund, that supported increasing vaccine confidence and addressing mis- and disinformation by engaging trusted community voicesFootnote 117.

Given high vaccine coverage, jurisdictions planned to focus the public health response more on localized surges in cases and monitoring severity indicators rather than applying broad restrictive public health measures. Ensuring sufficient public health system capacity was especially important as other pressing health priorities and a return to a more typical influenza/respiratory virus season would put added pressure on an already exhausted public health workforceFootnote 118. Personal protective measures such as staying home when sick, hand hygiene, and respiratory etiquette continued to be important even after jurisdictions lifted restrictive public health measures. However, it was imperative to remain responsive to signals of increased SARS-CoV-2 activity, maintain vigilance and preparedness for existing and emerging variants of concern, and monitor vaccine effectiveness, both across the country and internationally.

Canada’s COVID-19 situation in the global context

As of August 31, 2021, globally, there were over 215 million reported COVID-19 cases and close to 4.5 million COVID-19-related deathsFootnote 119. Similar to Canada, many other benchmark countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) experienced outbreaks and resurgences after the summer of 2020, including those that were initially successful in preventing or limiting a first waveFootnote 119. Each country’s individual epidemiological trajectory is influenced by a multitude of factors, and thus their respective data must be interpreted with caution.

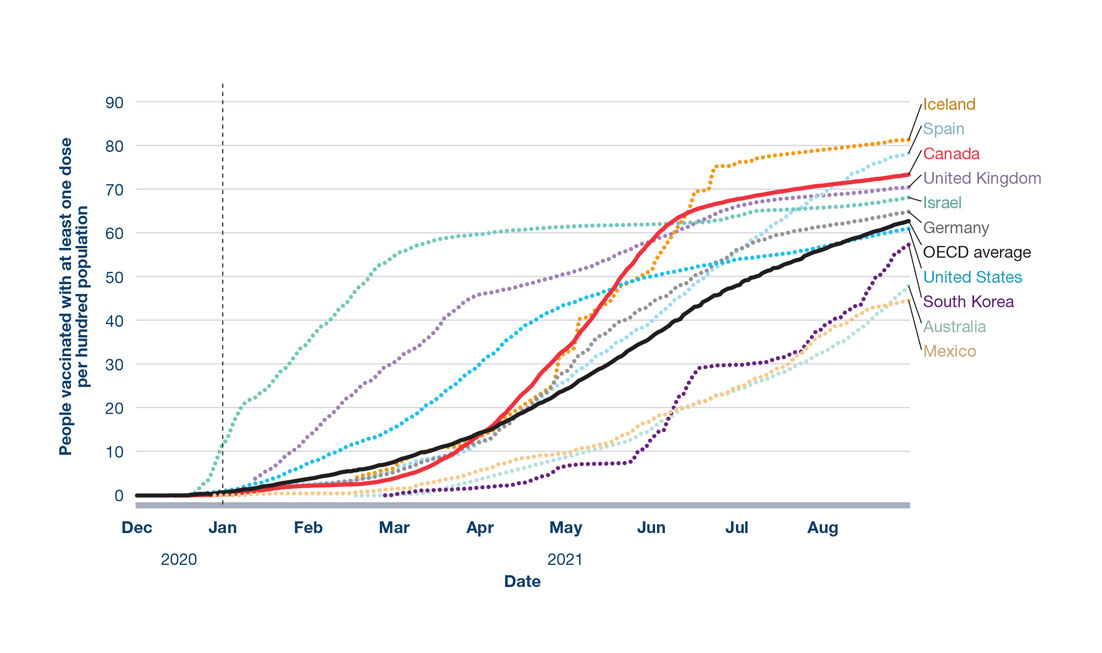

In 2021, many OECD countries transitioned to focusing their public health response on achieving high vaccination coverage. Compared to countries such as the USA, UK, and Israel, mass vaccination in Canada began somewhat later (Figure 5)Footnote 119. However, as a result of accelerated supply, expansion of provincial/territorial vaccination campaigns, and an extended dose interval strategy, as of August 31, 2021, Canada had administered at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine to 73% of the total populationFootnote 40. These combined efforts contributed to Canada’s ranking of #7 for highest first-dose coverage among OECD countries at the timeFootnote 119.

Canada looked to the experiences of other countries as they faced resurgences driven by more contagious variants. For example, Israel, Iceland, and the UK all experienced rapid increases in cases in the summer of 2021 caused by the Delta variant, even with relatively high vaccination coverage (Figure 5). However, as of August 2021, the number of COVID-19-related hospitalizations or deaths in all 3 countries was far less than those reported during previous wavesFootnote 119. The experiences of these countries, as well as emerging evidence that vaccine-acquired immunity may wane over time, emphasized the need for continued caution as vaccine coverage increasedFootnote 120. Easing of public health measures must be controlled, gradual, and responsive to the local epidemiological context, even once infection rates are brought to low levels.

As of August 31, 2021, only 40% of the world’s population and 2% of people in low-income countries had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccineFootnote 119 Footnote 121. Globally, the lack of supply and access to COVID-19 vaccines means that many places will remain in the acute stage of the pandemic for the foreseeable future. Canada remains committed to working with partners to reach equitable global vaccination targets, for example through the donation of vaccines and funds to the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) initiativeFootnote 122. The support that Canada provides internationally benefits Canadians as well because the future course of COVID-19 in Canada is dependent on working with all countries to end the pandemic.

Figure 5: Text description

The figure is a line graph displaying the cumulative number of people who have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine in Canada and selected countries from December 2020 until August 2021. The vertical axis displays the number of people vaccinated with at least one dose per hundred. The horizontal axis displays the elapsed time in months. The countries are represented by different coloured trend lines: Iceland (orange), Spain (light blue), United Kingdom (light purple), Israel (green), Germany (grey), South Korea (dark purple), United States (bright blue), Australia (light green), and Mexico (light orange). Canada and the OECD average are depicted as red and black solid lines, respectively, for ease of comparison versus dashed lines for all other countries.

| Date (selected time points) |

People vaccinated with at least one dose per hundred population |

|---|---|

| Australia | |

| 2021-02-28 | 0.1 |

| 2021-03-31 | 2.6 |

| 2021-04-30 | 7.7 |

| 2021-05-31 | 14.5 |

| 2021-06-30 | 23.8 |

| 2021-07-31 | 32.5 |

| 2021-08-31 | 47.3 |

| Canada | |

| 2020-12-31 | 0.3 |

| 2021-01-31 | 2.2 |

| 2021-02-28 | 3.6 |

| 2021-03-31 | 13.2 |

| 2021-04-30 | 32.4 |

| 2021-05-31 | 57.2 |

| 2021-06-30 | 67.6 |

| 2021-07-31 | 70.9 |

| 2021-08-31 | 73.4 |

| Germany | |

| 2020-12-31 | 0.3 |

| 2021-01-31 | 2.3 |

| 2021-02-28 | 4.9 |

| 2021-03-31 | 11.9 |

| 2021-04-30 | 27.7 |

| 2021-05-31 | 43.0 |

| 2021-06-30 | 55.3 |

| 2021-07-31 | 61.5 |

| 2021-08-31 | 64.8 |

| Iceland | |

| 2020-12-31 | 1.4 |

| 2021-01-31 | 3.1 |

| 2021-02-28 | 5.7 |

| 2021-03-31 | 14.4 |

| 2021-04-30 | 31.9 |

| 2021-05-31 | 49.9 |

| 2021-06-30 | 75.5 |

| 2021-07-31 | 78.4 |

| 2021-08-31 | 81.4 |

| Israel | |

| 2020-12-31 | 11.3 |

| 2021-01-31 | 35.3 |

| 2021-02-28 | 53.7 |

| 2021-03-31 | 59.7 |

| 2021-04-30 | 61.5 |

| 2021-05-31 | 62.1 |

| 2021-06-30 | 63.7 |

| 2021-07-31 | 65.9 |

| 2021-08-31 | 68.1 |

| Mexico | |

| 2020-12-31 | 0.0 |

| 2021-01-31 | 0.5 |

| 2021-02-28 | 1.5 |

| 2021-03-31 | 5.3 |

| 2021-04-30 | 9.6 |

| 2021-05-31 | 16.7 |

| 2021-06-30 | 24.2 |

| 2021-07-31 | 36.4 |

| 2021-08-31 | 44.5 |

| South Korea | |

| 2021-02-28 | 0.0 |

| 2021-03-31 | 1.7 |

| 2021-04-30 | 6.6 |

| 2021-05-31 | 11.3 |

| 2021-06-30 | 29.9 |

| 2021-07-31 | 37.9 |

| 2021-08-31 | 57.1 |

| Spain | |

| 2021-01-31 | 2.7 |

| 2021-02-28 | 5.5 |

| 2021-03-31 | 11.4 |

| 2021-04-30 | 25.2 |

| 2021-05-31 | 38.9 |

| 2021-06-30 | 54.8 |

| 2021-07-31 | 68.1 |

| 2021-08-31 | 78.2 |

| United Kingdom | |

| 2020-12-31 | 1.5 |

| 2021-01-31 | 13.6 |

| 2021-02-28 | 29.7 |

| 2021-03-31 | 45.7 |

| 2021-04-30 | 50.4 |

| 2021-05-31 | 57.9 |

| 2021-06-30 | 65.8 |

| 2021-07-31 | 68.6 |

| 2021-08-31 | 70.5 |

| United States | |

| 2020-12-31 | 0.8 |

| 2021-01-31 | 7.5 |

| 2021-02-28 | 14.8 |

| 2021-03-31 | 29.0 |

| 2021-04-30 | 43.1 |

| 2021-05-31 | 49.9 |

| 2021-06-30 | 53.7 |

| 2021-07-31 | 56.8 |

| 2021-08-31 | 61.0 |

| OECD average | |

| 2020-12-31 | 0.7 |

| 2021-01-31 | 3.8 |

| 2021-02-28 | 7.3 |

| 2021-03-31 | 13.9 |

| 2021-04-30 | 23.6 |

| 2021-05-31 | 35.5 |

| 2021-06-30 | 47.5 |

| 2021-07-31 | 56.0 |

| 2021-08-31 | 62.6 |

Reporting across countries may be based on different standards and frequencies. Therefore, these data should be interpreted with caution. Vaccination coverage may include non-residentsFootnote 119.

Broader health and social consequences of COVID-19 in Canada

While the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on health can be detected in many indicators of population health in Canada, as seen in the first wave, the consequences of the pandemic are not confined to the health domain.

As with the direct COVID-19 health impacts discussed in the previous section, the broader health and social impacts of the pandemic are disproportionally experienced among some key populations in Canada. Differential impacts are often connected to pre-existing health and economic inequities as well as access to resources and supports. As a result, the pandemic further worsened many of the structural and systemic factors that contribute to the inequitable distribution of power and resourcesFootnote 5 Footnote 14. This section will highlight a selection of examples that illustrate the complex and interconnected broader economic, social, and health impacts of COVID-19 and some of the governmental, community, and private sector initiatives to address them.

Overall life expectancy likely declined during the pandemic

An examination of life expectancy can provide a broad view of the most serious health impacts of the pandemic in Canada at the population level. Life expectancy is the number of years that an individual at a given age would be expected to live, given observed mortality rates. During 2020, there was an estimated reduction in life expectancy at birth of nearly 5 months for both sexes nationally, attributed to COVID-19 deaths aloneFootnote 123. Life expectancy in Canada has generally been increasing by about 2.5 months per year for the past 4 decadesFootnote 124. Increases in life expectancy at birth began to stall at the onset of the opioid crisis in 2016Footnote 124 Footnote 125. Even though life expectancy for 2020 was not yet calculated at the time of report writing, it is clear that COVID-19 will have a significant impactFootnote 123 Footnote 126.

While most excess deaths can be directly attributed to COVID-19, the pandemic also had indirect consequences on mortality. This can be seen most clearly for younger populations. Although 1,600 COVID-19-related deaths were reported in Canadians younger than 65 years of age between March 2020 and May 2021, there were 7,150 more deaths than expected in this age group over the same time periodFootnote 127. The worsening opioid overdose crisis is the likely cause of a significant portion of this excess mortalityFootnote 128.

Anticipated health issues on the horizon

COVID-19 has put enormous pressure on the Canadian healthcare system, and the negative long-term impact is likely to be profound.

During the pandemic, the use of some health services noticeably decreased. This may be driven both by fewer people seeking care as well as a decrease in the number and types of services availableFootnote 129. Within the first 10 months of the pandemic, the number of emergency room visits and hospitalizations decreased across the country. Advice to stay home may have resulted in fewer unintentional injuries and less transmission of other communicable diseasesFootnote 129 Footnote 130. Additionally, service providers in Canada that deliver sexually transmitted and blood-borne infection (STBBI) prevention, testing, and treatment reported a 66% decrease in demand for their servicesFootnote 131. This could be a result of people experiencing difficulty accessing services due to reduced hours or closures as a consequence of public health measures.

Given the pandemic’s burden on the healthcare system and the impact of public health measures, some services had reduced availability. Many jurisdictions postponed elective and other surgeries to ensure that enough resources were available for COVID-19 patientsFootnote 129. For example, in Ontario, the Financial Accountability Office estimated that, by the end of September 2021, it would take over 3 years to clear the surgery and diagnostic backlog that had accumulated during the pandemicFootnote 132. Researchers also project a future surge of cancer cases once diagnostic screening and surgeries resume after COVID-19-related interruptionsFootnote 133. However, contrary to adults, childhood cancer incidence rates and early outcomes appear to have remained stable throughout the pandemicFootnote 134. The pandemic also diverted public health resources from other programs, thereby limiting their capacity to work on other public health prioritiesFootnote 7. See text boxes “Post-COVID-19 condition” and “Public health measures impacted the spread and management of other communicable diseases” for more examples of the impact of the pandemic on health.

Post-COVID-19 condition

Post-COVID-19 condition (also known as long COVID) is defined as symptoms that persist or recur after acute COVID-19 illness, either in the short term (4 to 12 weeks after diagnosis) or long term (more than 12 weeks after diagnosis)Footnote 135. Preliminary findings from a systematic review indicated that 56% of people who tested positive for COVID-19 reported persistence or presence of one or more symptoms in the long termFootnote 135. While there are over 100 reported outcomes (i.e., symptoms, sequelae, and difficulties conducting usual activities), the most common symptoms include fatigue, general pain or discomfort, sleep disturbances, shortness of breath, and anxiety or depressionFootnote 135. Challenges are expected moving forward for the management of these patients, who may face long-term disability, putting additional pressure on the healthcare system. Canada has multiple specialized clinics that were created to manage post-COVID-19 conditionFootnote 136.

In partnership with Statistics Canada, academic institutions, and provinces and territories, PHAC is assessing a number of data sources that could be used to track cases of post-COVID-19 condition and related symptoms. The Government of Canada continues to monitor national and international evidence and support systematic reviews investigating the spectrum of complications associated with this conditionFootnote 137. Additionally, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research have funded prospective studies that will increase our understanding of the risk factors and long-term outcomes of COVID-19Footnote 138.

Rapid transition to virtual care

In order to minimize the risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2, many healthcare providers quickly shifted to offering virtual care appointments. Across 5 provinces for which data were available, in February 2020 48% of physicians had provided at least one virtual care service. This increased to 83% by September 2020Footnote 139. Older adults, who are at the highest risk of adverse COVID-19 outcomes, were the main users of virtual care, and researchers expected them to benefit the most from avoiding in-person visits when appropriateFootnote 140. However, using virtual care was challenging for individuals lacking digital literacy or reliable access to the Internet or telephoneFootnote 141. Further studies are needed to determine which health issues and circumstances are the most appropriate for the use of virtual care, and to ensure it does not exacerbate inequitable access to healthcare servicesFootnote 142.

Public health measures impacted the spread and management of other communicable diseases

The adoption of public health measures intended to manage the transmission of COVID-19 may have also curbed the spread of other infectious diseases. Despite increased testing, the number of laboratory-confirmed influenza cases reported between September 2020 and August 2021 was less than 0.2% of the number of cases reported during the same time period in 2018-19. Similarly, no influenza deaths were recorded in 2020-21 in the 8 reporting provinces/territories, compared to 223 influenza deaths recorded in 2018-19Footnote 143 Footnote 144.

Rates of other infectious diseases may also have been lower than previous years, although for some this could be due to decreases in testing as a result of broader COVID-19 consequences, rather than decreases in disease incidence. In 2020, both Alberta and Ontario reported a decline in incidence rates for chlamydia, HIV, and hepatitis CFootnote 145 Footnote 146. However, not all infectious diseases experienced a downward trend. For example, the rate of infectious syphilis increased by 8% in AlbertaFootnote 145. This continues a concerning pre-pandemic trend, especially impacting younger Canadians and under-served populationsFootnote 147. Additionally, emerging evidence showed that antimicrobial use in the community dropped significantly. From March to October 2020, the average national rate of antibiotic dispensing decreased by 27% compared to the pre-COVID-19 period. This may be related to a decrease in overall physician visits during the pandemicFootnote 148.

Canadians experienced worsening mental health during the pandemic

For many Canadians, the pandemic experience was coupled with the stress of job loss, isolation from loved ones, restrictions on community and recreational activities, and/or the need to balance work and caregiving responsibilities. There are indications that the breadth and depth of these challenges negatively impacted feelings and perceptions of mental health and well-being of many Canadians, especially among women, younger Canadians, and frontline workers.

Data collected in March and April 2021 as part of the Canadian Community Health Survey revealed that 42% of Canadians reported that their perceived mental health was “somewhat worse” or “much worse” compared to before the pandemicFootnote 149. Perceived worsening mental health was more frequently reported by females (44%) than males (39%), and it was also most commonly reported among Canadians aged 18 to 34 years (45%), 35 to 49 years (48%), and 50 to 64 years (40%) compared to seniors aged 65 years or older (33%)Footnote 149.

About 70% of healthcare workers who participated in a Statistics Canada crowdsourced survey during November to December 2020 reported perceptions of worsening mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Those who had contact with people with confirmed or suspected cases of COVID-19 reported higher rates of feelings of worsening mental health (77%) compared to those who did not report having direct contact with other people (62%)Footnote 150. While a direct pre-pandemic comparison was not available, according to the Survey on COVID-19 and Mental Health (SCMH), among Canadian adults, frontline workers were 2 times more likely to screen positive for post-traumatic stress disorder and 1.5 times more likely to screen positive for generalized anxiety disorder and/or major depressive disorder than those who were not frontline workersFootnote 151 Footnote 152.

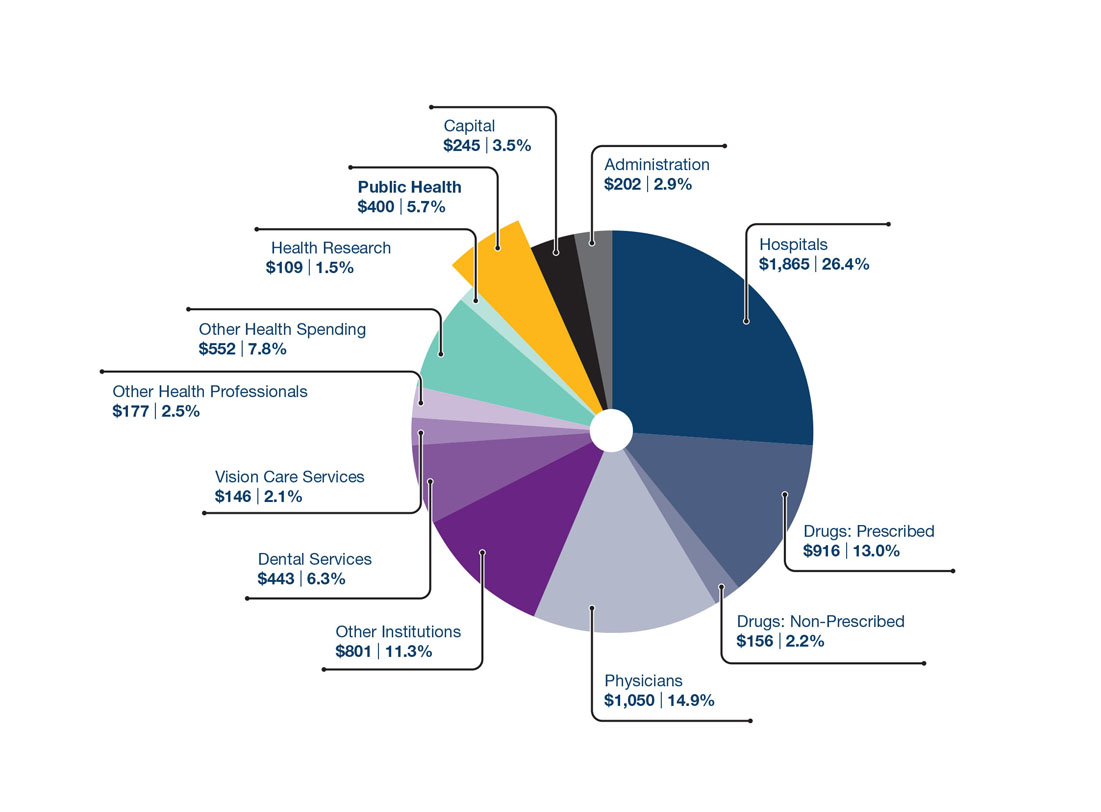

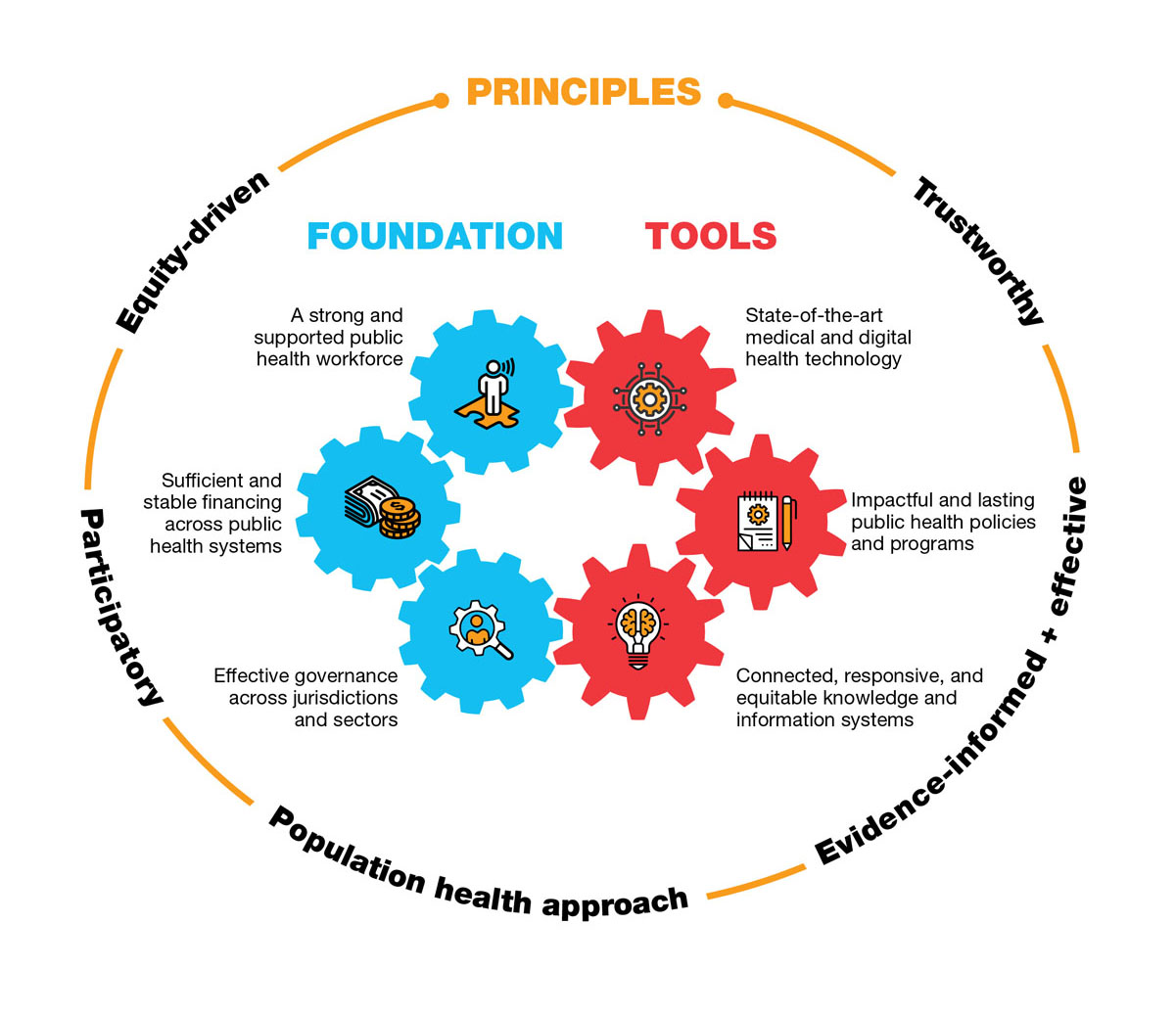

Although individuals aged 12 to 17 years were one of the age groups least likely to report feelings of worsening mental health in January and February 2021, the proportion reporting perceptions of poorer mental health doubled since September 2020Footnote 149. While there was limited national evidence at the time of report writing, a study conducted in the Greater Toronto Area from April to June 2020 suggested that deterioration of mental health during the pandemic occurred at a higher rate in children/adolescents with pre-existing psychiatric diagnosesFootnote 153. Kids Help Phone, an e-mental health service offering free confidential support to young Canadians, reported that the number of calls, texts, and clicks on their online resources more than doubled in 2020 compared to 2019Footnote 154. In response, the Government of Canada provided $7.5 million in additional funding for the crisis line to provide young people with mental health support during the pandemicFootnote 155.