Evaluation of PHAC’s activities for the Federal Framework on Lyme Disease and Action Plan

Download in PDF format

(933 KB, 64 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Published: 2022-05-30

Related links

Table of contents

- Acronyms

- Executive summary

- Conclusions

- Recommendations

- Background and context

- Evaluation scope and approach

- Conclusions and recommendations

- Management response and action plan

- Appendix A: Status of implementation

- Appendix B: Pillars and deliverables

- Appendix C: Methodology

- Appendix D: Evaluation rubric

- References

Acronyms

- CaLSeN

- Canadian Lyme disease Sentinel Surveillance Network

- CASN

- Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing

- CEP

- Centre for Effective Practice

- CFEZID

- Centre for Foodborne, Environmental and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases

- CIDSC

- Communicable and Infectious Disease Steering Committee

- CIHR

- Canadian Institutes for Health Research

- CLyDRN

- Canadian Lyme Disease Research Network

- CPHO

- Chief Public Health Officer

- FPT

- Federal, Provincial, or Territorial Partners

- HC

- Health Canada

- IDCCF

- Infectious Diseases and Climate Change Fund

- IDSA

- Infectious Diseases Society of America

- ILADS

- International Lyme and Associated diseases Society

- INSPQ

- Institut national de santé publique du Québec

- LDES

- Lyme Disease Enhanced Surveillance

- NICE

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- NML

- National Microbiology Laboratory

- OAE

- Office of Audit and Evaluation

- PC

- Parks Canada

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- SOGC

- Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada

Executive summary

Background

Evaluation purpose and scope

The purpose of this evaluation was to assess the effectiveness of PHAC's activities in support of the Federal Framework on Lyme Disease and Action Plan, from May 2017 to March 2021. The evaluation focuses exclusively on the role and activities of the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), and not that of other organizations involved in the Framework. The findings will feed into parliamentary reporting requirements, as specified in section 6 of the Federal Framework on Lyme Disease Act.

Program description

PHAC published the Federal Framework on Lyme Disease and Action Plan in 2017. The Framework and Action Plan identified 10 public health actions to prevent and reduce the risk of Lyme disease, grouped under 3 pillars: surveillance, education and awareness, and guidelines and best practices.

As the Government of Canada's federal lead on public health, PHAC is responsible for tracking new human infections of Lyme disease nationally, increasing awareness among Canadians and front-line health professionals, monitoring geographic risk areas in Canada, and supporting consistent diagnostics and reporting nationally. PHAC's activities for the Federal Framework on Lyme Disease and Action Plan are delivered by the Centre for Foodborne, Environmental and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (CFEZID) and the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML).

Conclusions

Implementation

PHAC has made progress in implementing several items from the Federal Framework on Lyme Disease and Action Plan, building on activities in place before the Federal Framework was developed. In some areas, implementation has been slower due to lack of consensus about the appropriate role of the Agency, differing views on the best ways to consider and meet the needs of those with lived experience with Lyme disease, and lack of dedicated funding. The COVID-19 pandemic caused further disruption to PHAC's activities due to competing pressures and priorities.

Effectiveness

Many of PHAC's traditional partners in the scientific community and other federal, provincial, and territorial partners reported generally positive impacts of PHAC's activities across the 3 pillars, while identifying opportunities to expand and improve work in the future.

Conversely, patient advocates saw urgent and unmet needs in the areas of surveillance, diagnosis, and treatment for Lyme disease, particularly for individuals who do not fit the case definition. These are needs that they feel are not adequately addressed by the scope of the Framework itself.

Engagements and partnerships

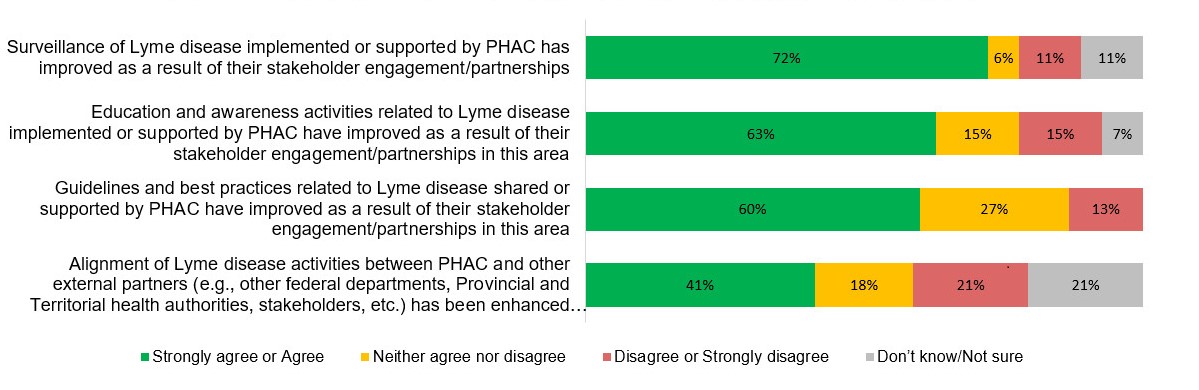

PHAC engagement included information sharing, dialogue with stakeholders, direct solicitation of feedback, and collaboration with external partners. PHAC has collaborated with a range of partners, including international governments, industry, non-governmental organizations, researchers, and other federal departments in the conduct of its Framework activities, resulting in revisions and enhancements to education and awareness products, and expanded reach via external partners. Those who report being engaged by, or partnering with PHAC feel that these activities have improved the quality of related pillar activities.

PHAC has participated in direct engagement with patient advocacy groups, including involvement in patient round tables and multidisciplinary stakeholder meetings covering a range of issues. However, the focus of most solicitation for input from these stakeholders has been largely related to education and awareness activities. Those who participated in engagement felt it positively affected PHAC's Framework activities. At the same time, there are still opportunities for improvement. PHAC has faced challenges effectively engaging with patient advocates and people with lived experience of Lyme disease.

Recommendations

Implementation of Federal Framework and Action Plan

Recommendation 1

- Focus on implementing the action items that are still in the early stages of implementation, or for which more needs to be done to achieve full implementation.

PHAC has made clear progress on implementing many of the action items described in the Federal Framework and Action Plan. However, there are number of areas where progress on action items has been limited (e.g., collecting surveillance on Canadians who do not meet the case definition for probable or confirmed Lyme disease, performing an analysis of costs associated with Lyme disease) or where further work is warranted (e.g., develop a national tick-borne diseases surveillance system). PHAC's abilities to complete some Framework activities have been (and may continue to be) delayed due to competing pressures and priorities resulting from the response to COVID-19. In this context, PHAC should focus on fully implementing outstanding action items as soon as possible.

Increasing effectiveness of Lyme disease activities moving forward

The Federal Framework and Action Plan states that work will continue only until 2022, however, PHAC's involvement in Lyme disease and other tick-borne illness activities will continue past this date. In light of this, we offer the following recommendations to increase the effectiveness for activities moving forward.

Recommendation 2

- Work to implement more timely and dynamic surveillance tools.

PHAC surveillance products help paint the national picture and demonstrate risk across jurisdictional borders; however, evidence suggests that products were not meeting stakeholders' information needs. Some stakeholders suggested that interactive and dynamic tools could help improve use of surveillance products, such as risk maps. Timely updates to risk maps, and enhancements to the visual depictions of risk areas to improve usability were also suggested.

Recommendation 3

- Enhance efforts to promote and disseminate awareness and education materials and guidance to existing and new knowledge users, including health professionals.

PHAC has distributed surveillance, guidance, and educational resources online, through social media, in journal publications, and through non-governmental organizations and industry partners, and through their Lyme and Other Tick-borne Diseases Email Subscription List. Despite this, there is a perception that some resources are hard to find and not reaching their target audiences. PHAC can address this challenge by continuing to enhance efforts to promote and disseminate awareness materials to an expanded audience, including to health professionals.

Recommendation 4

- Consider enhancements to engagement processes and partnerships with patient advocacy groups related to tick-borne disease activities, as these continue beyond the completion of the Federal Framework. This may include clearly communicating actions that result from the engagement, and setting clearly defined roles and expectations for all participants.

Regular ongoing opportunities for patient involvement in Framework activities, which was emphasized in the conference leading to the Framework, has been largely on a project-by-project basis thus far. This has not met patient advocate expectations. There is a continuing and longstanding lack of trust and strongly opposing viewpoints between patients and many working in the science community, the origins of which predates the Framework.

As PHAC continues to conduct patient engagement to address tick-borne disease activities following the completion of the Framework, PHAC should implement changes to their engagement process emphasizing a feedback mechanism whereby patient advocates can see how their input is used. Additionally, it may be beneficial to clearly define the roles each stakeholder group can expect to play in future Lyme and other tick-borne disease activities led by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Background and context

Lyme disease in Canada

Lyme disease is an infectious disease caused by the Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria. This bacterium can be spread to humans and animals through the bite of infected blacklegged ticks (or deer ticks) and western blacklegged ticks. Infection by the bacteria can lead to human illness. Lyme disease is one of several illnesses which can be spread by ticks, also called "tick-borne diseases."

Lyme disease usually results in a skin lesion called an erythema migrans rashFootnote i and non-specific symptoms including fatigue, fever, headache, and muscle and joint pains. If left untreated, it can disseminate through the bloodstream and affect other parts of the body. Patients with late infection may develop arthritis (inflammation in the joints and tissues around the joints), and, less commonly, neuropathy (nerve damage). While Lyme disease is rarely fatal, there have been recorded deaths as a result of Lyme carditis (also called "heart block").Reference 1Reference 2 Lyme disease may be missed or misdiagnosed, resulting in increased risk for serious illness. It is therefore important to identify, diagnose, and treat Lyme disease in its early phases.Reference 3

Some Lyme disease patients continue to have symptoms after completing treatment. According to Canadian infectious disease experts, the terms 'chronic Lyme disease' and 'post-Lyme disease syndrome' have been applied by some clinicians to patients with symptoms persisting longer than 6 months after treatment with the recommended agents. Persistent symptoms include fatigue, generalized musculoskeletal pain, and cognitive impairment without objective findings or microbiological evidence of active infection.Reference 4 Estimates from the John Hopkins Lyme Disease Research Centre state that anywhere from 10-20% of patients who received diagnosis and treatment during the "early" stage of Lyme disease develop ongoing symptoms.Reference 5

Box 1: Lyme Disease by the Numbers, 2009-2019

Photo of a black-legged tick sitting on a leaf.

- 10,152 human cases of Lyme disease have been reported in Canada since 2009.

- Between 2009 and 2019, the annual number of reported cases of Lyme disease in Canada increased 18 times from 144 to 2,636 cases.

- In Canada, 95% of reported human Lyme disease cases were from, Ontario, Quebec, and Nova Scotia.

Since PHAC began receiving data about the number of Lyme disease cases in 2009, the number of reported human cases has been growing (See Box 1). Climate change, along with a variety of other factors, has contributed to the increasing spread of ticks into more areas in Canada. As climates become more suitable for ticks and the season of tick activity expands, the likeliness of tick-borne diseases also increases.Reference 6 In addition to climate change, other environmental factors such as forestation, biodiversity, and the migration of host animals like deer, mice, and birds also affect the spread of ticks and, as a result, the frequency of tick-borne diseases.Reference 7 Lyme disease has now been reported in every Canadian province. Furthermore, other tick-borne diseases including Anaplasmosis, Babesiosis, Powassan virus, and Borrelia miyamotoi disease have started to emerge in Canada, and are likely to increase in the future.Reference 8

What is the federal framework on Lyme disease?

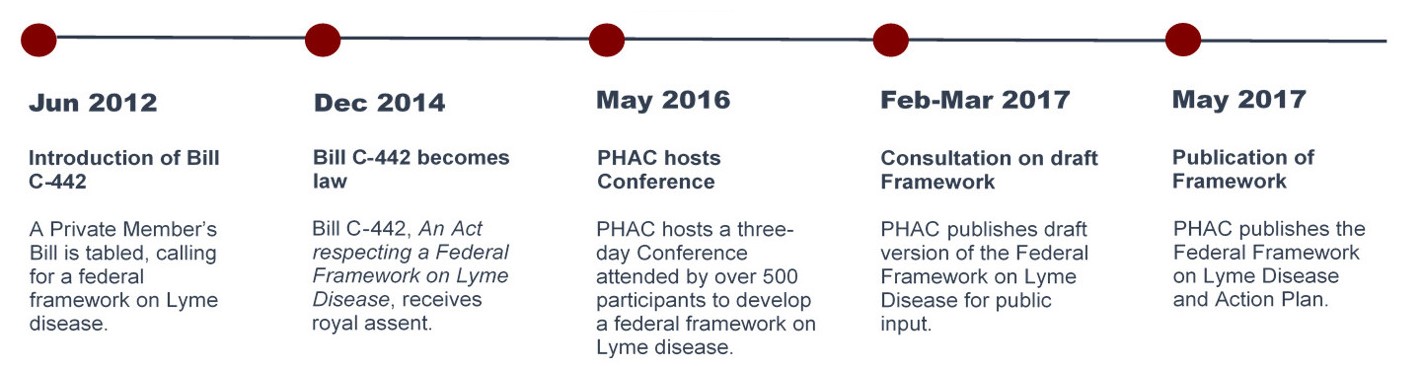

Figure 1 - Text description

This image provides a brief timeline of the development of the Federal Framework on Lyme Disease. The timeline contains the following dates and descriptions:

June 2012: Introduction of Bill C-442

A Private Member's Bill is tabled, calling for a federal framework on Lyme disease.

December 2014: Bill C-442 becomes law

Bill C-442, An Act respecting a Federal Framework on Lyme Disease, receives royal assent.

May 2016: PHAC hosts Conference

PHAC hosts a three-day Conference attended by over 500 participants to develop a federal framework on Lyme disease.

February to March 2017: Consultation on draft Framework

PHAC publishes draft version of the Federal Framework on Lyme Disease for public input.

May 2017: Publication of Framework

PHAC publishes the Federal Framework on Lyme Disease and Action Plan.

In 2014, the Federal Framework on Lyme Disease Act received royal assent. The Act required the Minister of Health to hold a national conference to develop a "comprehensive Federal Framework" to prevent and reduce Lyme disease-related health risks among Canadians.Reference 9Reference 10 In May 2016, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), on behalf of the Minister of Health, held a three-day conference to inform the development of the Federal Framework. Over 500 participants attended, including people with lived experience of Lyme disease, medical professionals, federal and provincial government representatives, academics and researchers, and others. PHAC published the Federal Framework on Lyme Disease and Action Plan in 2017 (See Figure 1). The Framework and Action Plan identified 10 public health actions to prevent and reduce the risk of Lyme disease, grouped under 3 pillars: surveillance; education and awareness; and guidelines and best practices.Reference 11

Implementation of the Framework and Action Plan began in May 2017 and, as per the Framework, was scheduled to continue until March 2022. The Framework identified the prevention and control of Lyme disease as a federal responsibility shared by multiple departments including PHAC, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Health Canada (HC), the Department of National Defense (DND) and Canadian Armed Forces (CAF), and Parks Canada (PC).Reference 12

The role of the Public Health Agency of Canada

The Public Health Agency of Canada has a mandate to promote health, prevent, and control chronic and infectious diseases, as well as prepare for and respond to public health emergencies. PHAC also serves as the central point for sharing Canada's expertise with the rest of the world, applies international research and development to Canada's public health programs, and strengthens intergovernmental collaboration on public health, including facilitating national approaches to public health policy and planning.Reference 13

As the Government of Canada's federal lead on public health for the Federal Framework on Lyme Disease, PHAC is responsible for tracking new human infections of Lyme disease nationally, increasing awareness among Canadians and front-line health professionals, monitoring geographic risk areas in Canada, and supporting consistent diagnostics and national reporting. Given the Agency's mandate, strong emphasis is placed on prevention of Lyme disease with the goal of minimizing risks posed by Lyme disease to Canadians.Reference 14

At PHAC, zoonotic illnesses (such as Lyme disease) are addressed by the Centre for Foodborne, Environmental and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (CFEZID), in collaboration with the National Microbiology Lab (NML).Reference 15 CFEZID serves as PHAC's program and policy lead on zoonotic and emerging infectious diseases. As such, CFEZID manages the implementation of Framework and Action Plan, as well as related activities like the Infectious Disease and Climate Change Program and Fund (IDCCF). Meanwhile, the NML works to prevent the spread of infectious diseases through research, lab-based surveillance, emergency preparedness and response, specialized disease detection and diagnosis, and national and global collaboration.Reference 16

To deliver on its responsibilities under the Framework, PHAC needs to collaborate with its federal, provincial, territorial, and various international and non-governmental partners. These external partners include groups representing persons with lived experience, health professional associations, academia, and Lyme disease researchers, among others.

There was no new funding package created to implement the Federal Framework on Lyme Disease. PHAC financed its Framework-related activities through a combination of existing funding sources. PHAC reallocated existing departmental funding towards communications activities on Lyme disease directed at the Canadian public, and used the IDCCF to leverage the existing networks of NGO's and target Lyme disease awareness for health professionals. In 2017, the Minister of Health also announced a new grant worth $4 million over 4 years to establish a national research network on Lyme disease. This grant is managed by CIHR.

Evaluation scope and approach

The purpose of this evaluation was to assess the effectiveness of PHAC's activities in support of the Federal Framework on Lyme Disease and Action Plan from May 2017 to March 2021. The evaluation focused exclusively on PHAC's role and activities, and not those of other organizations involved in the Framework. The findings will fulfill parliamentary reporting requirements, as specified in section 6 of the Federal Framework on Lyme Disease Act. This was the first evaluation of the Federal Framework on Lyme Disease, and was led by PHAC's Office of Audit and Evaluation (OAE).

To conduct the evaluation, OAE collected information from various sources, including key informant interviews with internal and external stakeholders, a stakeholder survey, and a review of internal and public documents. More details on the evaluation methodology, data collection methods, and limitations are included in Appendix C.

Evaluation questions

To identify successes and opportunities for improvements under each of the Framework pillars, and on PHAC's partnership and engagement activities, the evaluation answers the following 3 questions:

- What progress has been made in implementing the Action Plan for the Federal Framework on Lyme Disease?

- How effective have PHAC's activities under the Framework and Action Plan been at:

- Enhancing surveillance of Lyme disease in Canada;

- Improving education and awareness of Lyme disease among Canadians and health care professionals; and,

- Sharing guidance and best practices to enhance the capacity of stakeholders (i.e., health care professionals, veterinary professionals, public health professionals, and laboratories)?

- How have partnerships and engagement activities contributed to the effectiveness of PHAC's activities under the Framework?

Understanding the findings in this report

While the Federal Framework on Lyme Disease and Action Plan clearly define activities expected to be achieved in the period of 2017 to 2022, the Framework does not include ways to measure success. In order to assess success in a consistent manner, OAE developed an evaluation rubric that provides standardized descriptions to assess the extent to which progress was made, and identify remaining opportunities for improvement (Appendix D). Effectiveness was assessed on the basis of reach to target populations, use of products and tools, quality of products and tools, and impacts of these products and tools in terms of awareness and behaviour change. These characteristics of success are based on similar approaches used in previous evaluations of health programs with a knowledge translation component. Reference 17 The rubric was used to guide analysis, conclusions, and associated recommendations.

The evaluation report presents findings related to implementation and effectiveness, as summarized under each of the 3 pillars of the framework: surveillance; education; and guidelines and best practices. Each section provides a high-level summary of key takeaways related to a specific pillar, then assesses success of implementation (what has been done), and effectiveness (how well it was done) using the assessment criteria defined in the evaluation rubric. Finally, the contributions of engagements and partnerships are assessed in a separate section which addresses mechanisms for engagement, as well as successes and challenges associated with these mechanisms.

Surveillance

Key takeaways

PHAC has initiated some activities under the surveillance pillar, but has not yet fully completed the implementation of any of the commitments under the Action Plan. Surveillance tools are available and reaching individuals and groups interested in Lyme disease, but there is disagreement on the quality and impact of these tools. There are opportunities to improve the timeliness and accuracy of surveillance, as well as to update current surveillance tools to be more visually attractive and dynamic, and to include clear information on what actions Canadians should take in response to the risk information provided. Slower progress in some areas was attributed to issues around the criteria that define Lyme disease for the purpose of public health surveillance, as well as competing demands associated with COVID-19.

Implementation: What has been done?

Rubric Score: Progress Made, Further Work Warranted

Since 2017, PHAC has supported and directly implemented surveillance activities for Lyme and other tick-borne diseases, building on efforts that predate the Framework. Nonetheless, work still needs to be done to complete some of the commitments in the Action Plan accompanying the Federal Framework.

The Federal Framework commits to 4 actions related to ticks and tick-borne disease surveillance. These were:

- Integrate and disseminate innovative methods and best practices for human surveillance among an expanded group of partners;

- Collect human surveillance data in Canada for people who do not meet the case definition for probable or confirmed Lyme disease;

- Perform an analysis of the costs associated with Lyme disease; and

- Develop a national tick-borne surveillance system that includes Lyme disease and other possible co-infections.

Box 2: Examples of IDCCF-Funded Surveillance Projects

eTick.ca (Bishops University):

This citizen science-based project is a bilingual public platform for image-based identification and population monitoring of ticks in Canada.

Conseil de la Nation huronne-wendat:

This project supports the collection, identification and analysis of ticks in the Nionwentsïo territory, the ancestral territory of the Huron-Wendat Nation, to determine risk factors and at-risk members of the Huron-Wendat Nation, and raise awareness to prevent and minimize the risk of acquiring Lyme disease.

Mount Allison University:

This project aims to recruit and train volunteers to monitor ticks in their communities using a variety of approaches, in partnership with tick surveillance and education community organization partners in New Brunswick.

During the period covered by this evaluation, evidence from documents and internal key informant interviews demonstrate that PHAC has initiated actions related to developing innovative methods for surveillance and a national tick-borne diseases surveillance system. Using the Infectious Disease and Climate Change Fund (IDCCF), PHAC has supported several innovative surveillance projects across Canada (see Box 2), and has begun to disseminate surveillance findings via annual reports and infographics.Reference 18 While the focus of these projects is on tick surveillance rather than human surveillance, there is an emphasis on a "One Health" approach across these projects, which is a holistic approach that recognizes the connection between humans, animals, and the environment when addressing complex public health issues like vector-borne diseases.Reference 19

In addition to this work on tick surveillance, PHAC began exploring options for innovative human surveillance, such as a pilot surveillance project launched in Manitoba that used administrative health records to estimate all clinician-diagnosed Lyme disease cases, to better understand cases of Lyme disease that may not have been reported via the Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System.

PHAC has also initiated work to expand national Lyme disease surveillance to other tick-borne diseases. PHAC and its provincial partners collaborated with the Canadian Public Health Laboratory Network and other experts to begin expanding Lyme Disease Enhanced Surveillance (LDES)Footnote ii to include other vector-borne diseases, including work to develop case definitions for Babesiosis, Anaplasmosis, and Powassan virus diseases. Furthermore, the Canadian Lyme Disease Research Network (CLyDRN) launched the Canadian Lyme Disease Sentinel Surveillance Network (CaLSeN) in 2019. In its "pilot year", the Network carried out standardized active surveillance of ticks in the environment at 14 sentinel regions across Canada's 10 provinces. Sentinel regions were not established in Yukon, the Northwest Territories, Nunavut or the mainland portion of Newfoundland and Labrador because environmental conditions at these latitudes were not suitable for black legged ticks to establish at the time that sentinel locations were selected. Reference 20 Extensive progress has been made towards planning and preparing for implementation of a national tick-borne surveillance system, including launching a pilot year of sentinel surveillance through CaLSeN, however surveillance for other co-infections at the national level (i.e. through LDES) has not yet been fully implemented.

For the remaining action items, work completed was in the early stages of implementation. Some internal key informants indicated that, in 2020, PHAC was in talks with research partners at the Canadian Lyme Disease Research Network (CLyDRN) to collaborate on a cost analysis; however, the scope of the project was not defined at the time of this evaluation. According to documents from 2017-18, PHAC had begun planning for human surveillance of Lyme disease for those who did not meet the national case definition. Case definitions provide a uniform set of criteria to define a disease for public health surveillance, allowing officials to classify and consistently count the number of cases across Canada.Reference 21 The Framework commits to collecting human surveillance data in Canada for people who do not meet the case definition for probable or confirmed Lyme disease, but who experience various symptoms consistent with Lyme disease or similar ailments. However, it does not specify the parameters that should be used for this surveillance. In the absence of a standardized case definition, PHAC faced challenges finding consensus on the appropriate approach to measure these cases. Initially, PHAC explored several options, including conducting surveillance through a voluntary Lyme disease patient registry; however, this project did not proceed, based on an internal management decision, due in part to lack of agreement on the best manner to collect and manage this information, as well as concerns regarding data security and privacy. Instead, PHAC launched calls for proposals seeking an external contractor to look into the potential of using participatory action research to collect information about Canadians diagnosed with Lyme disease using "alternative means" or laboratory testing outside Canada.Reference 22 At the time of this report, the process to retain a contractor had been launched.

Furthermore, many internal and external key informants noted that the demand for resources to support the COVID-19 pandemic response, coupled with restrictions from public health measures, have had significant impacts on activities in the surveillance pillar, both at PHAC and among external partners. For example, some researchers participating in key informant interviews reported that they were not able to enter the field to conduct tick surveillance. Additionally, internal documents indicate that the National Microbiology Lab prioritized COVID-19-related testing, surveillance, research, and partnerships due to increased demand and limited capacity resulting from the pandemic. Staff working with CFEZID and NML were redeployed to support the COVID-19 response. Finally, competing priorities among provincial partners working in surveillance also resulted in delayed progress towards implementing changes to inter-jurisdictional initiatives, such as the work underway to expand enhanced surveillance of Lyme disease.

Effectiveness: How well was it done?

Rubric Score: Progress Made, Further Work Warranted

Overall, the evaluation found that interested persons are accessing PHAC surveillance information and generally find it valuable, but raised issues with accuracy and timeliness.

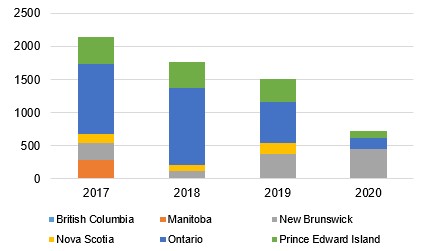

Reach

Evidence suggests that surveillance tools are available and have been reaching interested groups and individuals in Canada. While not representative of the general public, two-thirds (67%) of survey respondents were aware of at least one surveillance product. The most commonly cited products were risk maps and other risk information on Canada.ca and eTick. One of the primary methods PHAC uses to disseminate its surveillance information is via the PHAC website. Between March 2017 and January 2021, surveillance web content on Canada.ca was viewed over 50,000 times (nearly 12,000 times in French). Surveillance information is also distributed via publication in academic and peer-reviewed journals. Furthermore, evidence from documents and key informants indicates that innovative citizen-science surveillance projects, like eTick, connect the Canadian public directly with scientific experts in order to better access information about surveillance and monitoring of tick-borne diseases. Provincial public health partners also accessed laboratory support; documents show that the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) performed testing for 5 pathogens on 6,138 ticks collected via active tick surveillance from 7 provinces between 2017 and 2020 (Figure 2). According to contacts working with the National Microbiology Laboratory, the number of ticks tested has declined over the past few years due to a number of factors, including fluctuations in the number of ticks submitted for testing, changes in some jurisdictions which have stopped offering tick testing or imposed a fee, and reduced submissions due to COVID-19.

Figure 2 - Text description

This figure contains a stacked bar chart of the number of ticks collected by active surveillance between 2017 and 2020. Each stacked bar represents a year, with different coloured segments representing the number of ticks tested in each of the following provinces: British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island.

The number of ticks collected each year in total and by province are as follows:

2017

• British Columbia: 0

• Manitoba: 291

• New Brunswick: 254

• Nova Scotia: 133

• Ontario: 1051

• Prince Edward Island: 0

• Quebec: 418

• Total: 2147

2018

• British Columbia: 0

• Manitoba: 0

• New Brunswick: 118

• Nova Scotia: 85

• Ontario: 1172

• Prince Edward Island: 0

• Quebec: 389

• Total: 1764

2019

• British Columbia: 17

• Manitoba: 0

• New Brunswick: 363

• Nova Scotia: 169

• Ontario: 615

• Prince Edward Island: 2

• Quebec: 350

• Total: 1499

2020

• British Columbia: 0

• Manitoba: 0

• New Brunswick: 446

• Nova Scotia: 0

• Ontario: 171

• Prince Edward Island: 0

• Quebec: 111

• Total: 728

Quality

People accessing PHAC surveillance information and tools generally described them as valuable. Some key informants, particularly PHAC scientists and those working with the provinces and other federal departments, described surveillance as robust and benefiting from multiple data sources. Those who described surveillance positively noted the beneficial work underway to expand surveillance to more vector-borne diseases, and reported satisfaction with the direct support they receive from the NML. Survey evidence shows that a little more than 6 in 10 respondents agree that surveillance information was presented in an appropriate format (62%), and a smaller majority found them useful (57%), relevant (57%), and clear (52%). Similar to key informant interviews, survey respondents who identified as federal, provincial, territorial, or municipal partners, and those who identified as health professionals, were more likely to agree to positive statements about the quality of PHAC's surveillance activities.

Despite generally positive comments about PHAC's surveillance, internal and external key informants pointed out that PHAC has difficulty in communicating surveillance trends in a timely manner. However, it was noted that this is a challenge for other notifiable diseases too, since PHAC relies on provinces and territories to first collect, validate, and then share their regional data. For example, the most recent annual surveillance report for Lyme disease was published in 2021 and reflects 2018 data, while risk maps currently available on Canada.ca are based on data from 2016, collected before the implementation of the Framework.Reference 23Reference 24 For comparison, the most recent Lyme disease surveillance and risk products shared by the US CDC are based on 2019 data.Footnote iii Similarly, survey results showed that less than 40% of respondents agreed that PHAC's Lyme disease surveillance was timely.

Some survey respondents and key informants also highlighted concerns about the accuracy of Lyme disease surveillance. While there is disagreement about the magnitude of the problem, there is general agreement that current approaches to surveillance underestimate the incidence and prevalence of Lyme disease.Reference 25Reference 26 Underreporting was a significant concern for surveillance quality among patient advocates, as well as some researchers and subject matter experts. Less than half (46%) of survey respondents found surveillance information to be accurate. When asked about potential solutions to address underreporting, a few key informants referred to the approach taken by the US CDC for measuring Lyme disease. The American case definition for Lyme disease includes suspected, probable, and confirmed cases of Lyme disease, whereas Canada's case definition includes only confirmed and probable cases.Reference 27Reference 28 "Suspected" cases in the USA include any case of an erythema migrans (EM) rash, regardless of known tick exposure or laboratory evidence, or any case with evidence of infection and no clinical information available.Reference 29 Furthermore, by using commercial insurance records, the CDC was able to generate an estimate that approximately 476,000 Americans are diagnosed and treated for Lyme disease each year, while the American Nationally Notifiable Disease Surveillance System captures only 35,000 cases.Reference 30 The US CDC notes that this number is likely an overestimate, as it likely includes patients who received treatment but were not confirmed to be infected. While this data should be interpreted with caution, these counts highlight marked differences between those receiving treatment for Lyme disease and those being counted in reportable disease surveillance systems. PHAC intends to adopt a similar practice to detect potential cases currently missed by reportable disease surveillance by expanding an administrative health records pilot study in Manitoba to other provinces. Nonetheless, the challenge of underreporting and limitations in the case definition currently persists.

Use and impact

Some target audiences are using PHAC's surveillance products, but they have indicated opportunities to improve their usefulness by implementing more visually attractive and dynamic tools. Evidence from interviews and survey respondents suggest that those who were aware of products have used them, most commonly for general reference purposes or to share information with others. Provincial and other federal partner key informants reported using surveillance products to better understand risks outside their own jurisdictions. Nearly all survey respondents (96%) who were aware of products had used them in some way. However, less than half (41%) felt that the surveillance products met their information needs. While this may be explained in part by the timeliness and accuracy issues identified above, several key informants also described opportunities to improve surveillance products in order to enhance use, including ensuring information is presented in a way that can help guide behaviour, and creating more visually attractive, interactive, and real-time tools (e.g., real time mapping with eTick.ca).

Some external key informants raised concerns regarding unintended use of risk maps and tick surveillance products. While these products provide important epidemiological data that can inform action, some of key informants felt that some health professionals may be inappropriately using surveillance tools as diagnostic aids. For example, 1 researcher noted that some health professionals were waiting on the results of tick testing (rather than serological testing or clinical assessment) before proceeding to diagnosis or providing treatment for patients who had a tick bite.Footnote iv Similarly, some patient advocates noted that some health care providers would not test a patient for Lyme disease if they did not live in an area highlighted on PHAC's risk map. It is notable that PHAC's web page on the national case definition for Lyme disease currently states that "because tick populations are spreading, it is possible to be bitten outside of these areas."Reference 31 It also states that this case definition and related information are for "surveillance and epidemiologic purposes only, and they do not represent clinical case definitions."Reference 32 Nonetheless, it may be beneficial to promote further awareness that tools and resources such as the case definition and risk maps are shared for the purpose of public health surveillance at the population health level, rather than to inform diagnosis or treatment at the individual level.

Overall, external key informants provided limited feedback on the impact of PHAC's surveillance activities, noting moderate improvements to the state of surveillance, a better understanding of overall risk, and improved relationships between different stakeholders as a result of collaboration on surveillance projects. In addition, internal key informants indicated that PHAC's surveillance activities had helped to identify risk areas in order to better target PHAC's own awareness products. Survey results, however, pointed to a more mixed view on the impacts of surveillance activities: only about a third (34%) of respondents agreed that surveillance had improved identification of Lyme disease, or had improved overall since 2017, and over 2 in 5 respondents (43%) disagreed that PHAC's ability to respond to Lyme disease had improved through surveillance. As in other areas of the Framework, there were strongly opposing views, with people with lived experience of Lyme disease and researchers holding more negative views about impact compared to health professionals.

Education and awareness

Key takeaways

PHAC has implemented both action items under the Education and Awareness pillar of the Framework and Action Plan. PHAC launched its own awareness campaigns and collaborated with local and pan-Canadian partners to reach both public and health professional audiences. However, there remain opportunities to improve the relevance and targeting of materials to groups at high risk of getting Lyme disease. Key informants suggest there may be opportunities to improve the reach of education and awareness products to the Canadian public and health professionals. Due to limited information available to assess the use and impact of PHAC's materials and activities, it is difficult to describe to what extent these products have improved knowledge, ability, or behaviour concerning Lyme disease among health professionals or Canadians.

Implementation: What has been done?

Rubric Score: Key Deliverables Achieved

Since May 2017, PHAC has developed and distributed, either directly or through its partners, a range of education and awareness materials on Lyme disease. These materials were meant for front-line health professionals, and the Canadian public, including for groups at higher risk of getting Lyme disease such as children and Indigenous communities.

The Federal Framework and accompanying Action Plan commits to 2 action items under the Education and Awareness Pillar. These were:

- Support partners to develop early detection and early diagnosis education materials, with a focus on high-risk groups, to assist front-line health professionals and public health authorities in the prevention and diagnosis of Lyme disease; and

- Develop a national tick and Lyme disease education and awareness campaign, in collaboration with partners, that addresses:

- Tick bite prevention and early intervention; and

- Recognition of Lyme disease symptoms so that patients can seek help and front-line professionals can perform early diagnosis and treatment.

PHAC used the IDCCF to fund projects by external organizations to develop educational tools and resources targeting health professionals. Some projects are already completed, with awareness products published and promoted (see Table 1). For example, in early 2020, the Centre for Effective Practice (CEP) posted the Early Lyme Disease Management in Primary Care Tool on the organization's website. The CEP tool contains information to help primary care providers diagnose and treat early (localized) Lyme disease, and is accompanied by a resource sheet for patients.

| Key project output | Funding recipient | Brief project description |

|---|---|---|

Early Lyme Disease Management in Primary Care Tool and Information for Patients |

Centre for Effective Practice (CEP) |

Developed 2 national resources that address the needs of primary care providers and patients, and of the overall system, related to Lyme disease. |

Guidelines on Vector-Borne Disease for Nursing Education |

Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing (CASN) |

Developed a comprehensive set of national, evidence-informed, and consensus-based guidelines and e-resources for new nurses. The resources are intended to build knowledge and capacity to address the public health impacts of vector-borne infectious diseases emerging or expanding in Canada due to climate change. |

Lyme-Aid: Helping Pregnant Women and their Health Care Providers Prevent Lyme Disease and other Tick-Borne Diseases During Pregnancy |

Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) |

Following a review of current evidence on the effects of Lyme and other tick-borne disease on pregnancy, and a baseline survey of health care providers' knowledge and capacity to prevent and treat Lyme disease, the SOGC developed and disseminated resources for women and their health care providers to help prevent exposure. |

Through the IDCCF, PHAC also funded the development of materials targeting groups who may be at higher risk of acquiring or suffering from Lyme disease. These kinds of projects included the suite of resources for health care providers of pregnant patients from the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC). SOGC reviewed the available research around Lyme disease and pregnancy, and published guidance for health professionals on caring for pregnant patients who may have Lyme disease.Reference 33 This guidance, published as the Committee Opinion on the Management of Tick Bites and Lyme Disease during Pregnancy, was accompanied by a virtual workshop, educational resources for health care providers, and an online course on Lyme disease and pregnancy. Other IDCCF projects targeting health professionals are ongoing. These include the Canadian Public Health Association's National Forum for knowledge exchange, capacity building, and collaboration to address infectious diseases and climate change; the University of Guelph project assessing One Health competencies among current and future health professionals; and the New Brunswick Department of Health's project to build health care sector capacity through development of tick diagnostic laboratory services, surveillance, and monitoring activities, as well as communication strategies.Reference 34 In addition to PHAC's support of the work of external partners, PHAC also shares information on Lyme disease for health professionals on Canada.ca/Lymedisease.Reference 35

PHAC has also developed several education and awareness products targeting the Canadian public. Each year during the period covered by evaluation, PHAC ran seasonal awareness campaigns from April to October, aligned with tick season. PHAC has also posted information on their website that is available year round. In addition to running its own awareness campaign, PHAC partnered with non-governmental organizations, other federal departments, and industry to distribute educational materials. For example, PHAC partnered with the retail chain Marks to distribute wallet cards and information on permethrin treated clothing, with Parks Canada to provide an interpreter toolkit for guides, and with Ingenium museums to run a touring children's exhibit on ticks.

To complement these active awareness efforts, PHAC shared educational resources for Canadians on its web pages, by mail, and via an email subscription service launched in 2020. Notably, PHAC customized some awareness materials for certain groups based on their risk of acquiring Lyme disease. For example, social campaigns targeted parents of children under 14 years of age, and outdoor enthusiasts. PHAC also worked with Indigenous Services Canada to adapt its online education resources for Indigenous audiences. Furthermore, PHAC partnered with external organizations via the IDCCF to fund awareness campaigns. For example, PHAC partnered with the Canadian Public Health Association to develop and disseminate a teacher's toolkit on tick-borne diseases, and launch a national student poster contest for grade 6 students.Reference 36

Key informants noted that several planned in-person awareness activities were postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, notably the travelling children's tick exhibit. A few internal key informants suggested that the lack of dedicated funding for the Framework limited how broadly these awareness activities and resources could be shared. Nonetheless, PHAC continued to conduct its seasonal awareness campaign on Lyme disease throughout the COVID pandemic, and this was the only federal advertising campaign in 2020-21 after the start of the pandemic. Overall, PHAC has developed and shared educational materials for both the Canadian public and for health professionals, as described in the Action Plan.

Effectiveness: How well did it work?

Rubric Score: Progress Made, Further Work Warranted

The evaluation found that members of the public and health professionals have accessed Lyme disease education and awareness materials produced or supported by PHAC. However, due to primarily relying on interested parties seeking out information via the Web, it is not clear whether these products have reached an expanded audience, nor the extent to which they have helped these audiences better understand Lyme disease or improve their ability to prevent or detect it. Opportunities for improvement include finding strategies to ensure that education and awareness resources are reaching a broader set of knowledge users, including health professionals, and improving the relevance and resulting use of educational materials among groups at higher risk of getting Lyme disease.

Reach

Through its own awareness campaign and its collaborations with partner organizations, PHAC was able to deliver educational materials on Lyme disease to many members of the public and to health professionals. These include the following groups that PHAC highlighted as their key target audiences: residents in Lyme disease risk areas, Indigenous communities, and school-aged children and their caregivers. During the 2020-21 digital advertising campaign to promote awareness materials, PHAC's Lyme disease web pages for the public received over 89,000 visits, while its health professionals' pages received 73,000 visits. The previous fiscal year, 2019-20, Canada.ca/Lymedisease was one of the most visited pages on the Canada.ca website. Additionally, PHAC launched a Lyme and other tick-borne diseases email subscription list in 2020 as a way to send regular updates about PHAC's Lyme disease activities to interested stakeholders. The subscription list now has over 600 subscribers, of whom approximately half are health professionals.

Furthermore, PHAC supported regional and community-level organizations to implement their own education and awareness projects targeting key groups through the IDCCF. One such project was the 2019 park ambassador training program ran by the Institut national de santé publique du Québec (INSPQ). INSPQ trained 18 park ambassadors who held 28 awareness events on Lyme disease that directly reached over 1,860 provincial park visitors.

The IDCCF also funded professional associations and provincial public health bodies to develop and disseminate education materials to health professionals. While disruptions due to the pandemic meant that many promotional activities were delayed or cancelled, some projects were able to pivot to virtual ways of sharing their materials with their target audiences. IDCCF funding recipients like the Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing (CASN) and the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (SOGC) produced electronic resources, such as online courses and webinars that were accessed by over 1,800 viewers and over 36,000 viewers respectively, and may have been viewed by thousands more through advertisements and social media posts. However, performance data did not specify whether those who accessed these resources were front-line health professionals. Furthermore, PHAC promoted IDCCF-funded education and awareness products, including the CEP tool and eTick (among other topics) via the Zoonoses and Adaptation in a Changing World webinar series, targeting the scientific community working in climate change adaptation and One Health.

Despite these achievements, there appears to be room to improve the reach of PHAC's education and awareness products. According to OAE's stakeholder survey, only 22% of survey respondents felt that educational resources for Canadians were reaching their target audience. Nearly a quarter (24%) of survey respondents were unaware of any of PHAC's education products. Furthermore, key informants from interviews with patient advocacy groups felt the burden of promoting these resources often fell on them. Several external key informants also questioned why PHAC's website did not include any information about the CEP clinical toolkit created using funding from the IDCCF. Feedback from open text survey responses and key informant interviews across multiple categories suggests that there are opportunities to increase and enhance dissemination of the education and awareness resources that already exist, particularly those targeting health professionals.

Quality

Feedback from key informant interviews and survey respondents suggests mixed opinions on the quality of PHAC's education resources for the Canadian public. Key informants representing other federal departments, provincial governments, or a professional association, generally spoke about how the public-oriented resources they were aware of were of good quality, with appropriate and evidence-based information. While approximately half of survey respondents agreed that products directed at Canadians are relevant (57%), accurate (54%), and useful (52%), less than half agreed they are timely (39%) or adequately address high risk groups (28%). Patient advocates and people with lived experience of Lyme and tick-borne diseases were less likely to hold positive views on the quality and usefulness of education and awareness materials for Canadians, relative to other respondent categories, in both survey responses and key informant interviews.

Meanwhile, information from a few different sources suggests that people hold generally positive views on the quality and relevance of education materials for health professionals. Results from surveys and focus groups conducted during the testing phases of CASN and SOGC's IDCCF resources indicate that potential users felt these resources were relevant and useful in addressing Lyme disease prevention. Additionally, most external key informants and the small number of health professionals who completed the stakeholder survey expressed positive views towards some of the education materials produced for health professionals. In particular, several external key Informants from various respondent categories described the CEP tool kit as being a high-quality educational source for health professionals on acute Lyme disease and that the quality of the tool was in part the result of productive collaboration with patients. However, patient advocates raised concerns that the information in education materials destined for health professionals was insufficient overall. The materials reflect what they see to be the limited scope of the Framework, which is focused on prevention and early detection of Lyme disease, and do not address education for health professionals on management of later stages of the disease. Furthermore, some key informants working with patient advocacy groups disagreed with the information on Lyme disease that PHAC has shared on Canada.ca, such as the science around the possibility of congenital (parent-to-child) transmission during pregnancy, and the time period for which a tick must be attached to a person in order to pass the bacteria that causes Lyme disease.

To improve the quality of PHAC's education and awareness products, some external key informants emphasized that resources could be updated more frequently to reflect the latest scientific research and to point to the newest tools or resources that reflect the changing landscape. Additionally, a few key informants, both internal and external, pointed out that the messaging in awareness campaign materials was often broad and lacked a clear target audience. These key informants suggested that there is an opportunity to better complement existing provincial, territorial, and regional awareness resources by further tailoring information in federal products to target those living in endemic regions or participating in activities that involve increased risk of exposure to ticks, such as individuals in outdoor occupations, as has already been done with education products targeting Indigenous communities and individuals.

Use and impact

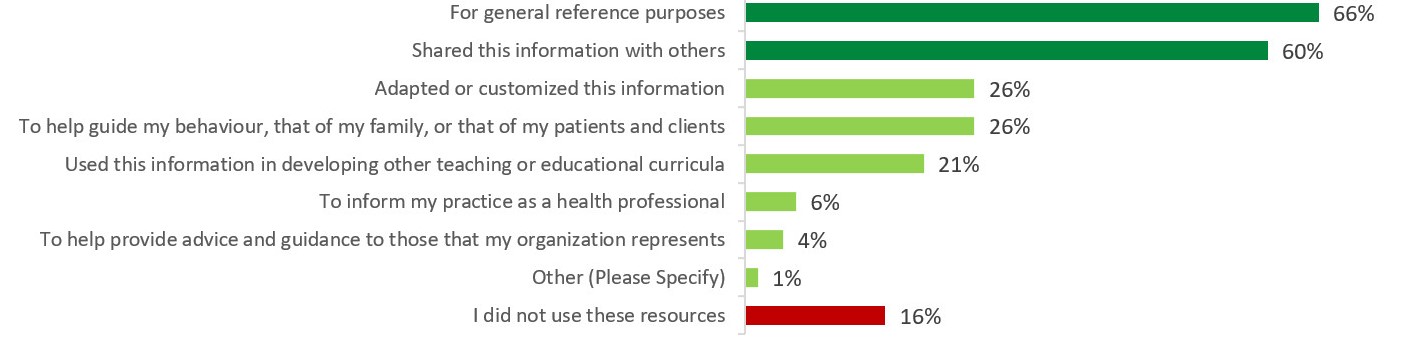

Figure 3 - Text description

This figure contains a horizontal bar chart illustrating the uses for Lyme disease education products for the Canadian public, and the percentage of survey respondents that indicated each type of use.

The bars representing "For general reference purposes" and "Shared this information with others" are coloured in dark green to show these were the most common uses of education products by survey respondents. The last bar, "I did not use these resources" was coloured in red to highlight the percentage of survey respondents who did not use education products at all.

The percentages for each of the types of uses of education products are as follows:

• For general reference purposes: 66%

• Shared this information with others: 60%

• Adapted or customized this information: 26%

• To help guide my behaviour, that of my family, or that of my patients and clients: 26%

• Used this information in developing other teaching or educational curricula: 21%

• To inform my practice as a health professional: 6%

• To help provide advice and guidance to those that my organization represents: 4%

• Other (Please Specify): 1%

• I did not use these resources: 16%

Information from document reviews, key informant interviews, and the stakeholder survey show that Canadians and health professionals are using education and awareness products created directly by, or with support from PHAC. When it came to products intended for the Canadian public, it appears that individuals are mostly using them for reference rather than to influence their personal behaviour or work practices. For instance, stakeholder survey results show that, among respondents who were aware of education and awareness products targeting the Canadian public, the most commonly reported use of the information was for general reference purposes (66%), or to share with others (60%). Meanwhile, about a quarter of respondents who were aware of the products (26%) reported that they adapted the information for their own needs, and the same proportion of respondents (26%) said they used the products to guide their own behaviour, that of their family, or that of their patients and clients (see Figure 3).

Most key informants working for provincial or regional jurisdictions expressed that they were less likely to use PHAC's products to guide their own behaviour, or that of their clients and those they represent, stating that they preferred educational resources that were already available from their provincial or local authorities, were more specific to their region, and better met local information needs.

Box 3: Impact of the CEP Lyme disease Clinical Toolkit

Funded by the IDCCF, the Centre for Effective Practice produced an Early Lyme Disease Management in Primary Care Tool for Canadian primary care providers, as well an accompanying patient information handout. Both resources are available on the CEP website in English and French.

As of October 2020, the CEP provider tool was downloaded 3,272 times, while the patient handout was downloaded 1,490 times. CEP conducted a survey in October 2020 and found the toolkit had a positive impact for both primary care providers and patients.

Among primary care providers who responded to the survey, more than 9 in 10 (93%) agreed or strongly agreed that the provider tool is a valuable resource for primary care providers. Meanwhile, 6 in 10 (62%) used the provider tool in their practice.

Finally, large majorities (78% to 89%) indicated positive impact of the tool on their knowledge and behaviour. These impacts were improved knowledge of Lyme disease and improved confidence in diagnosing, treating and advising patients on Lyme disease.

With respect to products intended for health professionals, their use was difficult to assess as there was minimal data available, due in part to delays in recipient-led evaluation activities caused by the pandemic. Aside from a survey of CEP's clinical toolkit (see Box 3), data on the effectiveness of IDCCF-funded educational tools are not yet available. Additionally, only a small number of health professionals and representatives of health professional organizations responded to the stakeholder survey. Among survey respondents from these 2 groups, only half were aware of any resources for health professionals developed or supported by PHAC, although among respondents who were aware, all indicated having used the resources in at least one way.

There were mixed views regarding the impacts of education and awareness materials on Canadians and on health professionals. Just over half of survey respondents who were aware of resources for Canadians (51%) agreed that viewing the resources led to improved awareness of ways to prevent tick bites. Approximately one-third or less agreed that the resources led to increased awareness of symptoms (35%), of treatment (30%), or of groups at higher risk of acquiring Lyme disease (26%). Slightly more people agreed than disagreed that these products led to increased awareness of health risks associated with Lyme disease (42% vs. 35%).

People with lived experience of Lyme disease and groups representing them were more likely than other survey respondents to disagree that education and awareness products targeting the Canadian public had positive impacts. In interviews, these key informants suggested that PHAC's materials have made little impact because the majority of the Canadian public and health professionals are still unaware of them, and the information presented is not detailed enough to be relevant and useful. Some pointed out the opportunity to elevate partnerships with groups representing people with lived experience and with health professional bodies to disseminate and customize resources.

Finally, although internal and external key informants have pointed out that impacts are not being measured for many education and awareness activities, there is evidence of such efforts being made in the near future. For example, a PHAC-led baseline survey on Lyme disease and other climate change-related infectious diseases took place in 2021.Footnote v The online survey examined Canadians' knowledge, attitudes, barriers, and motivations that influence their tick-bite prevention behaviours. Additionally, the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association (CVMA) received IDCCF funding in late 2020 to conduct a baseline survey to assess awareness of tick-borne diseases in veterinarians, pet owners, anglers, and hunters. After this survey is launched, the data that will be collected from this survey may be used to inform future awareness campaigns for these target audiences. As such, to better understand the usefulness and effectiveness of its education and awareness activities, PHAC should ensure more consistent measurement of performance and impact.

Guidelines and best practices

Key takeaways

PHAC has made clear progress on some deliverables under this pillar, such as establishing a national Lyme disease research network and supporting laboratory diagnosis, but has made limited progress in areas where there is greater scientific uncertainty and where responsibilities are shared across multiple jurisdictions. Stakeholders disagree about the effectiveness of PHAC's activities for this pillar: traditional public health partners were generally positive about the work PHAC has undertaken, whereas patient advocates were less positive, particularly related to issues surrounding persistent symptoms of Lyme disease post-treatment, described by some as "chronic Lyme disease."

Implementation: What has been done

Rubric Score: Progress Made, Further Work Warranted

The Federal Framework states that "guidelines and best practices that are evidence-based and effectively targeted to reach specific groups will be critical to address Lyme disease" and highlighted the importance of focusing on prevention, diagnostics, treatment, and research. The accompanying Action Plan sets out 4 commitments to accomplish the goal of developing guidelines and best practices in these areas. These were the following:

- Establish a Lyme disease research network;

- Work with international public health partners to share best practices and disseminate domestically;

- Continue to support front-line health professionals and provincial laboratories in the laboratory diagnosis of Lyme disease; and

- Consult with provincial and territorial health care regulatory authorities on innovative, evidence-based approaches to address the needs of patients.

PHAC has made some progress on implementing activities under this pillar, though significant work remains to meet Action Plan commitments. The most notable accomplishment under this pillar was the creation of a national Lyme disease research network. The Federal Framework states that a research network should be established that builds on existing research and research networks, and will engage with clinical experts, researchers, and patient groups.Reference 37 In 2018, PHAC worked with CIHR to award a $4 million grant to establish the Canadian Lyme Disease Research Network (CLyDRN). The research network includes experts from almost 20 universities across Canada and the US, hospitals, provincial and federal public health agencies, veterinary colleges, and health care practitioners. PHAC has also made progress working with international public health partners by establishing regular Webex meetings with public health representatives from Canada, Australia, France, USA, UK, Germany, Belgium, and Scotland held in 2019 and 2020. Meetings were planned bi-annually, but were paused due to competing work related to COVID-19. A report and overview of international approaches to Lyme disease prevention is in development by Webex participants, but has not yet been circulated. PHAC has also posted international guidelines for treatment from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), the UK-based National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), and the International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society (ILADS) on its web page for health professionals.

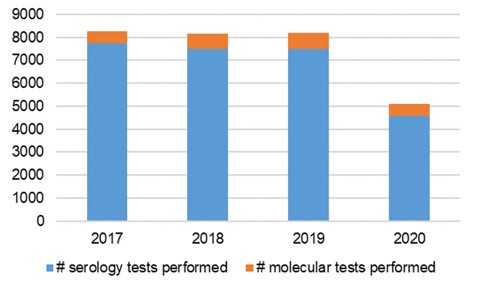

Figure 4 - Text description

This figure shows a stacked bar chart of the number of laboratory tests that were conducted for tick-borne pathogens in human specimens by the National Microbiology Laboratory from 2017 to 2020. Each stacked bar represents a year, separated into 2 colours by whether the test performed was a serology test (blue bar) or a molecular test (orange bar). The number of tests performed are as follows:

2017

• # serology tests performed: 7730

• # molecular tests performed: 540

• Total # tests performed: 8270

2018

• # serology tests performed: 7503

• # molecular tests performed: 647

• Total # tests performed: 8150

2019

• # serology tests performed: 7511

• # molecular tests performed: 684

• Total # tests performed: 8195

2020

• # serology tests performed: 4590

• # molecular tests performed: 515

• Total # tests performed: 5105

Finally, with respect to laboratory diagnostics, the NML performed between 4,000 and 8,000 serological diagnostic tests and between 500 and 700 molecular detection tests on human specimens to detect tick-borne pathogens each year between 2017 and 2020 (Figure 4). The Framework document states that "The Canadian Public Health Laboratory Network, which provides national leadership through a proactive network of public health laboratories, monitors developments in laboratory diagnostics closely and publishes laboratory diagnostic guidelines that are consistent with those in the United States and Europe. New methods are evaluated, and any that prove to outperform current methods will be incorporated into updated guidelines for laboratories and front-line health professionals." PHAC scientists have continued to publish peer-reviewed articles examining the application of novel laboratory diagnostics; however, the current guidance cited in the case definition is from 2006-07.Reference 38Reference 39 The case definition was reviewed in 2018 without changes. In comparison, the US CDC most recently updated their case definition for Lyme disease in 2017.Reference 40

PHAC has faced some challenges implementing activities under this pillar, particularly with respect to the focus on treatment and research. For example, while a research network itself was established, evidence from documents and interviews suggests the network has not succeeded in building meaningful partnership with patient groups due to a significant and longstanding level of disagreement and distrust that pre-dates the Framework. Based on this finding, progress towards the commitment to engage patient groups as part of establishing the research network is considered to be preliminary. Furthermore, the Federal Framework states that "Further research in this area is required into the causes of […] persistent symptoms and chronic illness, and the methods of treatment. All partners, including provincial and territorial health care regulatory authorities, will be consulted on innovative, evidence-based approaches to address the needs of patients."Reference 41 While PHAC did provide educational resources for health professionals on managing Lyme disease (as described under the education pillar), it did not advance work to engage with provincial-territorial health care regulatory authorities to address the needs of patients. Internal key informants noted that PHAC did not see a role for itself in the area of treatment. Instead, PHAC took a broader interpretation, determining that efforts were more suitably focused on education and outreach to health professionals. This is a point of contention for key informants representing patient advocacy groups, who have near- unanimously expressed an urgent unmet need in this area, with no single jurisdiction claiming leadership to advance progress.

Effectiveness: How well has it worked?

Rubric Score: Little Progress, Priority for Attention

As with other areas of the Framework, there are opposing views on the quality of work regarding guidelines and best practices between the scientific community and other traditional public health partners, and those working directly with people with lived experience of Lyme disease. Patient advocates in particular felt there were issues with the dissemination and quality of the products and resources supported by PHAC, particularly from CLyDRN. While provincial and territorial public health laboratory partners were appreciative of support from NML, these stakeholders did not feel that other work in this pillar had affected their work in a significant way at the time of the evaluation.

Reach

Given the variety of activities included under this pillar, describing the extent to which target audiences were participating in, or reached by efforts to share guidelines and best practices also varies. Network-based efforts, such as CLyDRN and international Webex meetings were described by some key informants as improving the connection between communities of experts. Documents indicated that CLyDRN has over 80 researchers as members from institutions across Canada representing a variety of fields, while Webex sessions connected public health experts from 8 countries. As with other deliverables, the primary method PHAC has used to distribute resources under this deliverable is by posting on Canada.ca, where, for example, information on treatment was viewed over 63,000 times (22,000 times in French) between March 2017 and January 2020. While results are not generalizable, about two-thirds of survey respondents were aware of at least one guideline or best practice resource supported or shared by PHAC. The most commonly referenced resources were CLyDRN, treatment guidelines for localized (early) Lyme disease on Canada.ca, international treatment guidelines shared on Canada.ca, and scientific publications from PHAC.

Despite this, several key informants working with patient advocacy groups reported concerns that important information about treatment options was not reaching patients or health professionals. They noted that their organizations are often the first point-of-contact for individuals who have been bitten by a tick and are experiencing symptoms. These key informants felt that PHAC could take a more active role in ensuring that guidelines and best practice resources reach Canadians and health professionals, rather than waiting for Canadians to search for information on PHAC's website.

Quality

Perception of the quality of PHAC's efforts related to guidance and best practices varied widely between PHAC's traditional public health partners and those representing people with lived experience of Lyme disease. This divergence is perhaps most notable in relation to CLyDRN. Several internal key informants, including PHAC's research partners and partners from provincial-territorial public health units, spoke highly of the research currently underway through CLyDRN. However, survey responses and key informant interviews from representatives of patient advocacy organizations, persons with lived experience, and some researchers and subject matter experts indicated significant distrust of the quality of work from the research network, in part due to challenges with patient engagement.Footnote vi

Survey responses reflect this strongly opposing view as well: less than half of respondents agreed that resources produced under this pillar were relevant, accurate, timely, or useful. When disaggregated, people with lived experience (75%) and groups representing them (42%) were most likely to disagree with positive statements on the quality of deliverables under this pillar. Conversely, health professionals and groups representing them (62%), as well as provincial, territorial, or municipal representatives (63%), were more like to agree to positive statements about quality. Some key informants across all groups noted a need to ensure that guidance and best practices shared by PHAC are consistent and reflective of the most recent scientific information. Suggestions to achieve this included assessing the strength of evidence informing those guidelines, and their limitations.

Patient advocates, as well as some researchers and subject matter experts raised concerns that, in general, the quality of some work completed under the guidelines and best practices pillar was limited due to the fact that the scope of these resources did not address persistent symptoms post-treatment. For example, while the CEP tool was generally viewed positively across all stakeholder groups for management of acute Lyme disease, there is still no agreed-upon Canadian guidance for management of persistent symptoms or chronic illness.

Use and impact

Given the early stage of implementation for most activities under this pillar, limited information was available to assess use and impact. In general, provincial partners noted that they benefitted from close relationships with PHAC and support from the NML for laboratory services. In particular, one partner reported that PHAC has supported development of local capacity within their region, enabling them to conduct diagnostics locally and reducing the delay in reporting. About half of key informants provided examples of the perceived impacts of activities under this pillar, including enhancements to capacity, collaboration, and information sharing among a network of vector-borne disease experts that predates the Framework.

Despite this, several external key informants across multiple stakeholder categories noted that they had not yet seen impacts from PHAC's activities under this pillar. This view was also reflected in survey responses, where less than one-quarter agreed that resources under this pillar had enhanced information sharing (23%), diagnostic capabilities (18%), or had improved understanding of the groups that are at high risk for Lyme disease (17%). Disagreement was driven by respondents who identified as people with lived experience, groups representing them, and researchers working in the area of Lyme disease. Provincial, territorial, and municipal partners were moderately more positive, with just over 4 in 10 agreeing to positive statements about the impacts of guidelines and best practices. The lack of research and guidance on evidence-based treatment of persistent Lyme disease symptoms was raised as a priority issue, particularly among key informants from patient advocacy groups, and reflected in open text survey responses. The Federal Framework states that "further research […] is required into the causes of these persistent symptoms and chronic illness, and the methods of treatment."Reference 42 While this is not the only goal of the third pillar, the Framework text established an expectation among external stakeholders that chronic illness would be addressed. While CLyDRN has initiated some work in this area, including active research studies, such as a Chronic Lyme Disease Survey Study launched in December 2020,Reference 43 feedback from key informants, including patient advocates and a few researchers and subject matter experts, suggests that the evidence gap remains. This ongoing gap in the area of management of persistent symptoms of Lyme disease may explain the perception of limited impacts among some stakeholder groups.

Engagements and partnerships

Key takeaways

PHAC has enacted a spectrum of engagement and partnership activities, ranging from information sharing to direct partnerships for the development and delivery of programs. Those who participated in engagement activities felt they positively affected PHAC's Framework activities. At the same time, there are still opportunities for improvement. PHAC has faced challenges effectively engaging with patient advocates and people with lived experience of Lyme disease.