Evaluation of Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care

Download in PDF format

(754 KB, 39 pages)

Organization: Health Canada or Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: December 2022

Final report

December 2022

Prepared by the Office of Audit and Evaluation

Public Health Agency of Canada

Table of contents

- List of acronyms

- Executive summary

- Purpose of the evaluation

- Evaluation scope and approach

- Context

- Key findings: Expertise

- Key findings: Methodology

- Key findings: Governance

- Key findings: Task Force funding

- Key findings: Effectiveness – Knowledge translation, timeliness, and usefulness

- Conclusions

- Management Response and Action Plan

- Appendix 1 - Data collection and analysis methods

- Appendix 2 - Comparison with similar organizations in the UK and US

- Appendix 3 - Task Force guideline development process – Methodology

- Appendix 4 - Knowledge translation

- Endnotes

List of acronyms

- CFPC

- College of Family Physicians of Canada

- CPHO

- Chief Public Health Officer

- CPL

- Clinical Prevention Leaders

- ERSC

- Evidence Review and Synthesis Centre

- G&Cs

- Grants and Contributions

- GHGD

- Global Health and Guidelines Division

- GRADE

- Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development & Evaluation

- HCV

- Hepatitis C Virus

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- PTs

- Provinces and Territories

- TF-PAN

- Task Force Public Advisors Network

- UK

- United Kingdom

- US

- United States

Executive summary

Context

The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (the Task Force) was re-established by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) in 2009 to develop clinical practice guidelines that support primary care providers in delivering preventive health care.

The Task Force creates national preventive health care guidelines based on systematic reviews of scientific evidence and with input from a range of experts and key stakeholders, including patients and members of the public. The Task Force is supported by the Evidence Review and Synthesis Centres (ERSC) in Edmonton and Ottawa, which conduct the systematic reviews of the evidence. The Task Force also works with the Knowledge Translation program at St. Michael's Hospital in Toronto to support its dissemination activities. In addition to these groups, the Task Force is supported by the Global Health and Guidelines Division (GHGD) at PHAC, which provides scientific and technical support to the Task Force.

This evaluation covered Task Force activities from April 2017 to July 2022 and used a number of lines of evidence to assess the Task Force's expertise, methodology, governance, and funding mechanisms as well as the effectiveness of its knowledge translation activities.

What we found

Since its re-inception, the Task Force consistently used a balanced mix of clinical and methodological expertise to its guideline development process by engaging with a wide variety of internal and external partners and stakeholders. However, some gaps remain in terms of Indigenous populations, rural and remote physicians, and nurse practitioners, and a number of vacancies on the Task Force. In addition to expertise, the ERSCs use the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) method in its evidence reviews which is considered the international standard in this area.

According to its mandate vis-à-vis the Task Force, PHAC maintained a balance between oversight and the Task Force's independence. At the same time, the Task Force maintained its independence from outside organizations largely through its use of a strong conflict of interest policy.

Governance processes and roles and responsibilities were generally well established to help support guideline development. However, there was some confusion around PHAC's role versus that of the ERSCs, particularly with regard to scoping and carrying out evidence reviews.

There was evidence that the large number of knowledge translation activities helped raise awareness of the guidelines, and knowledge translation tools and resources. There was also some evidence of use and impact of the guidelines on professional health practice. However, the guideline development process was seen to be slow and, for the last three years, the Task Force was not able to meet its commitment of producing three guidelines per year. One of the main challenges was that the Task Force was unable to expand its dissemination activities and recruit certain types of primary care professionals due to its current funding challenges.

Recommendations

A number of lines of evidence were reviewed as part of the evaluation, including files and documents, performance data and data from interviews with internal and external key informants. As a result, three recommendations emerged.

Recommendation 1: Explore ways to improve the timeliness of the guideline development process.

The Task Force has committed to producing three guidelines per year; however, it has not met this target since 2018. Several factors have affected the Task Force's ability to produce its guidelines, including the sudden death of the incoming Chair, turnover at GHGD, increased workloads, and Task Force members' and GHGD staff's involvement in the COVID-19 pandemic response. Other factors affecting the timeliness of guidelines included an inability of some Task Force members to volunteer due to a lack of remuneration, too many internal reviews, too many meetings, and the length of time it took to draft scoping questions. PHAC, in consultation with the Task Force, should continue to explore ways to improve the timeliness of the guideline development process to ensure it meets its goal of producing three guidelines a year.

Recommendation 2: Given challenges, explore potential changes to address funding issues and adapt the Task Force funding model appropriately:

- Examine potential compensation for Task Force members, which may help to diversify its current composition.

- Examine ways to prioritize or optimize activities within available funding.

The lack of compensation for members affects the Task Force's ability to recruit new members. Without such compensation, some health care professionals such as rural and remote physicians are unable to participate. The lack of compensation has also limited the amount of time that members can devote to Task Force activities, affecting overall timeliness.

PHAC is the sole funder of Task Force activities and most interviewees felt it should remain so, as it helps to avoid the possibility that outside organizations could compromise the independence of the Task Force. At the same time, funding amounts have remained largely unchanged while salaries and planned activities have increased because of efforts to increase awareness and use of the guidelines as well as involve the public as part of the guideline development process. This has resulted in Task Force partners (ERSCs and the Knowledge Translation program) needing to reduce certain activities and cut the number of employees they can retain.

Recommendation 3: Clarify PHAC's role versus that of the ERSCs with respect to scoping and conducting systematic reviews.

While roles and responsibilities were clearly outlined in Task Force documents such as the Methods Manual; there continued to be some confusion around PHAC's role versus that of the ERSCs. PHAC works closely with the ERSCs, providing scientific and technical support; however, there is a lack of clarity around PHAC's role in scoping and conducting systematic reviews. For some, this role was clear, but others felt PHAC was too involved in the reviews that were seen as an ERSC responsibility.

Purpose of the evaluation

The purpose of the evaluation was to assess the structure and funding of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (the Task Force), as well as the effectiveness of its activities.

The Global Health and Guidelines Division (GHGD), which is part of the Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch at the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) requested this evaluation to ensure the Task Force was operating as effectively as possible, and to determine if there were potential improvements to be made. This is the first PHAC evaluation of the Task Force.

Evaluation scope and approach

The scope of this evaluation covered Task Force activities from April 2017 to July 2022. Multiple lines of evidence were used. to address questions focusing on the following:

- To what extent is the structure of the Task Force set up to ensure that:

- • The appropriate level of external expertise is consulted; and

- • The independence of the Task Force is maintained?

- Does the current funding mechanism remain appropriate and sustainable?

- • Are other structures and funding approaches better suited to meet PHAC's objectives?

- Is PHAC's current role and involvement in supporting the Task Force appropriate?

- • Should PHAC adjust or expand its role? If so, how?

- • How does PHAC balance oversight with independence?

- How effective have the Task Force's guidance and knowledge translation activities been?

- • Are key target audiences aware of and using the Task Force's guidelines?

- • What more could be done to increase reach and use, especially among the Canadian public?

- • Are guidelines timely and useful?

See Appendix 1 for further details.

Context

The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care is an independent panel of primary care and prevention experts established and funded by PHAC. Its mandate is to develop evidence-based clinical practice guidelines to support primary care providers in the delivery of preventive health care.Footnote 1 The Task Force creates national preventive health care guidelines, based on the latest evidence and with input from a range of experts and key stakeholders including patients and members of the public.Footnote 2

Task Force members are volunteers, and over time, its membership has consisted of family physicians, mental health experts, pediatricians, other physician specialists, prevention experts, methodologists, and other primary care providers. A review of similar systems in the United Kingdom (UK) and United States (US) showed that the UK National Screening Committee has 12 members and the US Preventive Services Task Force has 16 members, all of whom are volunteers. See Appendix 2 for a summary of a comparison of the three organizations on a select number of criteria.

PHAC's GHGD provides scientific and technical support to the Task Force and acts as a liaison between the Task Force and provincial and territorial organizations, such as the Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health and the Public Health Network Council.

Through PHAC funding, the Task Force is supported by the Evidence Review and Synthesis Centres (ERSCs) in Edmonton and Ottawa, and the Knowledge Translation program at St. Michael's Hospital. The ERSCs undertake systematic reviews for the Task Force that form the basis for Task Force guideline recommendations. The Knowledge Translation program produces a variety of tools and conducts various dissemination activities to increase awareness and encourage the use of published guidelines.

Key findings: Expertise

The Task Force consults a wide variety of stakeholders with different kinds of expertise throughout the guideline development process. These partners and stakeholders bring a balanced mix of clinical and methodological expertise to the process. However, certain specialties and groups are currently underrepresented in the Task Force membership.

A wide variety of experts are consulted in the development of clinical practice guidelines.

The Task Force develops its guidelines with the support of several partners and stakeholders including, the ERSCs in Edmonton and Ottawa and the GHGD at PHAC, as well as using input from internal, external and clinical stakeholders, patients and the public.

Processes for engaging with partners and stakeholders are outlined in the Task Force Methods Manual.Footnote 3 Based on key informant interviews and a review of meeting minutes, the Task Force appeared to follow the guideline development process steps outlined in the Methods Manual. The evaluation found that the Task Force followed these processes throughout the guideline development process, from topic selection, scoping, and protocol development, to drafting recommendations and guidelines, external peer reviews and knowledge translation and dissemination. See Appendix 3 for details on the guideline development process.

An appropriate mix of expertise contributes to Task Force guideline development.

The Terms of Reference for the Task Force contain an extensive list of the expertise and experience required to join the Task Force, including expertise in disease prevention and health promotion, and experience with systematic reviews and guideline production. Most internal and external interviewees felt there was a good cross-section of expertise on the Task Force, as they described Task Force members as part of a well-balanced group of dedicated professionals with a range of expertise among clinicians and methodologists. Based on a review of membership biographies, Task Force members had a combination of clinical and methodological backgrounds. Some key informants noted that Task Force membership did not need to include expertise in every field, since content experts are engaged by the Task Force throughout the guideline development process.

Moreover, most internal and external interviewees reported that the ERSCs possessed expertise to support the development of guidelines; for example, experience in library science, conducting systematic reviews and specific statistical analyses. Most interviewees noted that the ERSCs are well respected in their fields. In 2019, Dr. David Moher, who leads the University of Ottawa ERSC, was inducted into the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences for his contributions to health research.Footnote 4,Footnote 5 He was also recognized in 2014 by being placed on an international list of top researchers for his ongoing research to improve systematic reviews.Footnote 6

With respect to the Knowledge Translation team at St. Michael's Hospital, most interviewees reported that this team consists of leading experts who are renowned nationally and internationally for their experience in sharing and brokering knowledge. In 2021, Dr. Sharon Straus, the Director of the Knowledge Translation program, was appointed to the Order of Canada, partly because of her work ensuring research is disseminated.Footnote 7 The Knowledge Translation team is also known for communicating with target audiences and preparing reports.

In addition to the expertise of the Task Force and its partners (i.e., ERSCs and the Knowledge Translation team), some interviewees commented on the expertise of the GHGD, content experts, and the public. For the most part, interviewees felt that the science team at GHGD was made up of hardworking and supportive staff. They noted that using a variety of content experts on guidelines committees was a good approach. Patient engagement began in fall 2020 and involved fifteen to twenty patients, caregivers, and members of the public. Interviewees felt that including patients and the public was critical to increasing uptake of guideline recommendations.

There is a good variety of expertise consulted in developing guidelines; however, there are some notable gaps.

As discussed in the previous section, while most interviewees felt there was a good mix of clinical and primary care experience on the Task Force, several of them identified the following important gaps:

- Indigenous representation – There have been attempts to recruit Indigenous representatives, but a gap remains.

- Nurse practitioners – In some provinces and territories, nurse practitioners play a large role in primary care; however, they are underrepresented on the Task Force.

- Rural and remote health care professionals – Given that Task Force members are volunteers who may need to give up some time from their practices to participate in the Task Force, recruiting rural and remote practitioners remains a challenge.

- Lack of physicians – Some interviewees felt there were too many academics on the Task Force; however, it may be easier for academics to join the Task Force because their universities cover their time and salary, and this would not be the case for most physicians.

- Number of vacancies in Task Force membership – As of July 2022, the Task Force had ten members instead of its usual fifteen. Due to the sudden death of the incoming Task Force Chair, as well as other members' involvement in the COVID-19 response, there were a few vacancies on the Task Force. However, three new members recently joined the Task Force.

- Patient and public engagement – While patient and public engagement through the Task Force Public Advisors Network (TF-PAN) was seen as a positive development, there has not been much engagement with this group since it was developed.

- Turnover at GHGD, the Knowledge Translation program at St. Michael's and the ERSCs – Several interviewees noted that there has been a bit of turnover at the ERSCs and Knowledge Translation program, which was not seen as unexpected given their involvement in the COVID-19 pandemic; however, a significant amount of turnover at the GHGD was seen as a challenge that resulted in delays in some processes.

Task Force members are aware of these gaps and the need to enhance diversity within its membership. As a result, a recruitment strategy is being established to foster diversity within Task Force membership, based on geographic location, rural and urban residence, gender, ethno-cultural background, marginalized communities (e.g., homeless, disabled), specialty area, and language.

The Task Force began developing the recruitment strategy in December 2021, and it aims to increase outreach and develop a pool of potential members through enhanced outreach; targeted messaging to identified groups on required skills, expectations, and time commitments; enhanced visibility of recruitment initiatives at conferences; and increased promotion via publications and fellowship programs.

In addition to outlining membership needs within the Task Force, the recruitment strategy identifies the following challenges:

- lack of remuneration for Task Force members; and

- additional workload associated with volunteering for the Task Force.

Similarly, most interviewees noted that the lack of remuneration for Task Force members was a significant challenge in recruiting and retaining members, especially those from specific medical occupations, such as nurse practitioners and rural and remote physicians.

Key findings: Methodology

GRADE is considered the gold standard of research methodologies and most interviewees felt that the Task Force should continue using it while exploring ways to refine it.

GRADE is the gold standard.

The ERSCs follow the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) method for conducting their reviews.Footnote 8 GRADE was developed in Canada to provide a transparent and rigorous approach to assessing evidence and is seen by most internal and external interviewees as the 'gold standard' in research methodology, thereby lending credibility to Task Force guidelines. GRADE is used to assess the quality of evidence for systematic reviews and clinical guidelines.Footnote 9 Furthermore, in order to be published, some journals require tools such as GRADE be used to assess the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for guidelines.

GRADE is not only used in Canada. According to the international GRADE Working Group, GRADE is used by over 110 organizations in 19 countries, including by notable organizations such as the American Academy of Family Physicians, the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, England and Wales' National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and the World Health Organization. Of note, the US Preventive Services Task Force uses a method similar to GRADE for its evidence reviews while the UK National Screening Committee does not appear to use GRADE.

While most considered GRADE as the gold standard, some interviewees cautioned that reviewers' appraisal of work can be subjective. They also noted that the recommendations can be somewhat confusing and, as such, require an explanation to be better understood. A few interviewees reported that there were other research methods available; however, they did not provide an improvement on GRADE.

Most internal and external interviewees believed the Task Force should continue to use the GRADE methodology as it is the international standard in this area.

Equity issues are considered in the development of guidelines.

The Task Force considers and develops recommendations for specific populations; for example, the inclusion of high-risk groups is considered during topic refinement, with input sought from national organizations. Decisions to include or exclude other high-risk groups are documented in Records of Decisions before the high-risk groups are included in the protocol. The following subgroups are routinely considered for examination: Indigenous people, remote or rural dwellers, women, children and adolescents, elderly people, immigrant populations, and ethnic subgroups in Canada, among others.

The decision whether or not to include subgroups depends on the quality of information and the feasibility of including information. Data is often only available for one or two critical outcomes, which may affect the feasibility of including subgroups. The Task Force attempts to assess whether its guidance has equity implications for specific subgroups, with an aim to identify any subgroups for which there is literature to support differential burden, effectiveness, harms, or implementation issues that result in including recommendations for specific subgroups in the final guidelines. The Task Force has also struck an equity working group with the goal of more effectively and consistently addressing such equity issues in their guidelines.

The evaluation found that between 2017 and 2022, the Task Force produced ten guidelines. Of those, five were directed at male and female adults, one was directed at male and female older adults, one was directed at older male adults, one was directed at female adults, one was directed at male and female children, and one was directed at female adults, as well as older female adults.

Key findings: Governance

Governance processes were well established and roles and responsibilities were clearly outlined in Task Force documents; however, some confusion remains around PHAC's role versus that of the ERSCs. There were no concerns about the Task Force's independence from outside organizations, due in large part to its use of a strong conflict of interest policy.

A clear process exists for determining Task Force membership.

Task Force membership is determined through a joint selection committee composed of Task Force leadership, two additional Task Force members, PHAC's Chief Public Health Officer (CPHO), and the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC)'s Executive Director of Professional Development and Practice Support. The selection committee makes recommendations for appointments to the Task Force, who then votes on the recommendations. Once the CPHO and CFPC representative receive confirmation from the Task Force, they appoint new members based on these recommendations. Task Force members are appointed for a four-year term that can be renewed once.

Governance processes were in place to support the development of guidelines.

The Task Force is typically comprised of fifteen primary care and prevention experts, including the Chair, Vice-Chair and Task Force members. Governance processes are clearly outlined in the Methods Manual, which identifies the roles of the Chair, Vice-Chair and Task Force members, as well as defining the governance structure of the Task Force.

The Task Force conducts its activities through an independent consensus-based decision-making process, meaning it requires agreement by a majority of at least two-thirds (66%) of its members. PHAC staff and non-Task Force members do not have voting rights.

According to its Terms of Reference, the Task Force meets in person approximately three times a year and conducts business between these meetings through teleconferences and working group meetings. During the pandemic, this changed to one via videoconference and two in person meetings per year. Members are required to attend meetings and alternates are not permitted.

A review of Task Force in-person and virtual meeting minutesFootnote 10 showed that between 2017 and 2022, seventeen meetings were held with on average forty-eight persons attending each meeting. These included the following: Task Force Chairs, Task Force Vice-Chair, Task Force members, Task Force Office, PHAC's GHGD, ERSCs, Knowledge Translation program staff, Task Force communications representatives, staff from the Chair's hospital, alumni, guests, interns and fellows. On average, 93% of invitees attended Task Force meetings. Of those attendees, about 35% of participants are from the Task Force.

The overall purpose of these meetings was to share updates on the progress of various guidelines, recruitment criteria for new members, guidelines topic selection, response timelines, communications procedures, GHGD updates (e.g., Methods Manual) and updates on knowledge translation activities (e.g., annual evaluations). In addition to sharing information, nearly half of the agenda items for discussion centered on the following main areas: feedback on topic selection, scope and key questions for synthesis reviews, and guideline recommendations.

Task Force documents clearly outline roles and responsibilities.

As previously mentioned, the Task Force Methods Manual maps out the steps in the guideline development process, with clear roles and responsibilities identified for the different stages.

The Methods Manual also clearly identifies roles and responsibilities for those involved in the guideline development process. The Task Force is responsible for prioritizing and selecting topics, developing research questions, informing evidence review methodologies and providing primary care input. It is also responsible for developing, publishing and disseminating guideline recommendations. The Task Force works with the Knowledge Translation program who helps to disseminate the guidelines. In addition, the Knowledge Translation team conducts annual evaluations of Task Force activities. PHAC's GHGD provides scientific and technical support to the Task Force, as well as administrative support (e.g., contribution agreement support and monitoring). Moreover, PHAC provides scientific support to the Task Force by assigning a scientific research manager for each topic to coordinate and provide scientific and methodological support during the development of systematic reviews and recommendations, and to lead working group discussions. PHAC works closely with the ERSCs who conduct the systematic reviews. PHAC's science team also writes the first draft of the guidelines document.

While PHAC's role was seen as appropriate, it could be clearer.

Most external interviewees felt PHAC's role was appropriate, stating that it played a good coordination role in supporting ERSCs and the Task Force throughout the guideline development process, but there was also some lack of clarity around PHAC's role in scoping and conducting evidence reviews. While a few interviewees thought PHAC's role was clear, a few others did not feel it was as clear as it could be. Some questioned PHAC's involvement in systematic reviews, thinking that they were doing too much in this area. There is a perception that PHAC has conducted some of the systematic reviews instead of the ERSCs.

As previously mentioned, one of the main challenges was staff turnover at PHAC, which resulted in changes to leadership and some process delays. For example, a few external interviewees felt that PHAC was taking too long to update the Methods Manual, saying that the work had been going on for a few years.

In terms of expanding its role, many external interviewees thought PHAC could play a bigger role in making connections with provinces and territories (PTs), since it already has established relationships. It was felt that engaging with PTs would help increase awareness and uptake of guidelines. While several interviewees felt PHAC could play a bigger role in raising awareness, there were mixed views on whether PHAC should expand its role in guidelines dissemination. A few interviewees said that PHAC could help actively disseminate the guidelines to increase awareness and use; however, many suggested that PHAC should not increase its dissemination efforts, as this could affect the perception of the Task Force's independence.

The Task Force was seen as an independent arm's length body.

The Task Force aims to be an independent guideline development body. Most internal and external interviewees reported that the independence of the Task Force and those involved in the guideline development process is a core value that is upheld by a strong conflict of interest policy. Most interviewees saw the use of this policy as a best practice.

The conflict of interest policy applies to all current and prospective members of the Task Force, as well as groups and individuals that provide external support to the Task Force.Footnote 11,Footnote 12 Members complete a Declaration of Affiliations and Interests Form to declare any conflicts of interest in writing. Task Force members must sign this form before each in-person meeting, and it is updated regularly and posted on the Task Force website. Upon joining a new project, each participant must also sign a Confidentiality Agreement, stating they will not use confidential information for any purpose other than those indicated by PHAC or the Task Force. Furthermore, each participant is responsible for informing PHAC of any changes that have occurred since a person's initial disclosure.

The Task Force was seen to be free from industry ties and only the Task Force has voting rights. Content experts, PHAC representatives, and those with a potential conflict are excluded from voting. This was confirmed by interviewees who reiterated that these groups are not permitted to vote. Another sign of adherence to potential conflicts of interest was highlighted by one interviewee who reported that a Task Force member excused themselves from the room anytime a specific guideline was discussed because they had a relative who was the fifth investigator on a small study linked to the guideline topic.

Moreover, several external interviewees noted that PHAC does not "meddle in" or try to influence Task Force activities. As previously mentioned, Task Force members are appointed by the CPHO and most external interviewees did not perceive any issues with the CPHO's approval of Task Force members, noting that the CPHO has never questioned the selection committee's recommendations.

In addition to its conflict of interest policy and Confidentiality Agreements, a few external interviewees felt the Task Force's independence is further strengthened by the transparency of its processes (e.g., posting meeting minutes online).

Key findings: Task Force funding

Most external interviewees felt that PHAC should remain the Task Force's sole funder to avoid the possibility that outside organizations could compromise its independence. The main challenges were that a lack of compensation for Task Force members was a barrier to participation for some health care professionals and overall funding did not keep pace with increases in activities and salaries.

Task Force activities are supported by PHAC through a contribution agreement.

PHAC is the sole funder of the Task Force. It supports the Task Force through a contribution agreement used to support enhanced dissemination of Task Force guidelines, public communications, evaluations, ERSCs, as well as to provide administrative support. The recipient of the current contribution agreement is the affiliated institution of the Task Force's Interim Co-Chair, the Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux du Centre-Ouest-de-l'Île-de-Montréal. The Task Force receives approximately $2 million a year. In comparison, the UK National Screening Committee received approximately £3.6 million in 2019-20 and the US Preventive Services Task Force has an annual budget of $11.5 million US dollars.

PHAC's GHGD works closely with PHAC's Centre for Gs&Cs and the Task Force Office to administer the funding agreement and support the Task Force. PHAC is responsible for the approval of expenses and annual reports; for example, the science team within the GHGD reviews and approves deliverables before payments can be released.

Most external interviewees felt that PHAC should continue to fund the Task Force and that there are no other possible funders for this work. Any other funders (e.g., industry) could have potential conflicts of interest and, given the Task Force's current independence, PHAC funding keeps it free of conflict and is the only pan-Canadian body in this area.

Task Force funding challenges

While a couple of interviewees felt that the introduction of an advanced payment model was helpful, as it allowed the transfer of unused funds to the next fiscal year, most internal and external interviewees highlighted some challenges with Task Force funding that affects its ability to attract Task Force members and complete certain activities.

In particular, Task Force activities have changed since it was re-established in 2009Footnote 13 (e.g., the addition of TF-PAN and other efforts to engage with patients and the Canadian public); however, funding amounts have not increased to accommodate this expansion in activities. Activities have expanded to help achieve Task Force outcomes and respond to recommendations in the annual Task Force evaluations. As such, the Knowledge Translation team can only plan TF-PAN engagements for one guideline at a time, which can cause a backlog for their development. Similarly, the Knowledge Translation program does not have the capacity to carry out other engagement efforts, which can affect dissemination and uptake.

Despite increases in salaries for the ERSCs and the Knowledge Translation program (approximately 10% according to one of the ERSCs), overall funding amounts have remained relatively unchanged between 2012 and 2021. This has resulted in fewer staff to work on Task Force activities making it more challenging to complete all planned or desired activities.

The Task Force has received occasional top-ups in funding; for example, $840,000 in PHAC Banking Day funding in 2019-20, but these have not been consistent, nor are they guaranteed going forward.

The lack of compensation for Task Force members affected its ability to attract certain practitioners; for example, rural and remote physicians. As previously mentioned, given that participation in the Task Force is voluntary and requires a large time commitment, some members are not in a position to give up time from their practices to participate. As such, a few internal and external interviewees suggested that PHAC should explore options to provide Task Force Chairs and members some form of compensation for their work. It is interesting to note that while Task Force members are not compensated, TF-PAN members are paid for their time to help encourage participation from the general public.

This lack of compensation has also limited the time Task Force members can devote to Task Force activities, which affects overall timeliness. With external advisory bodies at PHAC, compensation is determined on a case-by-case basis, and may be provided under exceptional circumstances such as a need for specific expertise.Footnote 14

In addition to the challenge with compensation, some internal and external interviewees noted that, given that the interim Chair of the Task Force is based in Quebec, there is an additional need to obtain Quebec government approval (M-30),Footnote 15 which results in delays in receiving funding.

Key findings: Effectiveness – Knowledge translation, timeliness, and usefulness

The Task Force and its partners carry out a variety of knowledge translation activities to help raise awareness and increase the use and impact of the guidelines and associated knowledge translation tools and resources.

The Knowledge Translation program carries out various knowledge translation activities.

The Knowledge Translation Working Group (KT WG) develops and maintains relationships with external peer reviewers and stakeholders (e.g., primary care practitioners, the public, general and disease-specific organizations, policy makers), and identifies opportunities for engagement throughout all stages of the guideline development and dissemination process.

The Knowledge Translation program developed strategies and partnerships aimed at enhancing knowledge exchange, uptake, and dissemination of Task Force guidance to stakeholders through the development of decision tools, publications, presentations (30 between 2017 and 2020), podcast plays (21,187 between 2017 and 2020), media interviews (68 between 2017 and 2020), and website visits (1,620,886 between 2017 and 2020). Between 2017 and 2020, the Breast Cancer Screening Guideline was the most visited guideline on the Task Force website.

The Task Force also conducted activities to disseminate its guidelines and knowledge translation tools, such as usability testing, exhibiting and distributing hard copies of knowledge translation tools at conferences, delivering presentations, releasing e-learning modules, maintaining and updating the Task Force website, updating the quarterly newsletters and Task Force Twitter account with new guideline publications, and making all Task Force materials available through mobile applications (QxMD Calculate and Read). The Knowledge Translation team conducts annual evaluations of the Task Force's knowledge translation activities. While there were no specific awareness targets established, the 2021 annual evaluation report highlights primary care practitioners' awareness of the following knowledge translation resources:

- Task Force website (81%);

- Task Force newsletter (53%);

- Task Force College of Family Physicians article series 'Prevention in Practice' (45%); and

- QxMD Calculate Mobile application (36%).

Of note, only 7% of primary care practitioners were aware of the Task Force's Twitter account.

The Clinical Prevention Leader (CPL) network was established in 2017 to promote the dissemination and uptake of Task Force guidelines and to address barriers in guideline implementation. The 2020 Knowledge Translation team's annual evaluation of Task Force activities showed that the CPL network pilot was successful in achieving the primary objectives of building capacity among primary care practitioners in evidence-based medicine and knowledge translation, as well as supporting the dissemination of Task Force guidelines and tools in primary care practices. More specifically, the CPL reported higher ratings of knowledge and awareness of guideline development processes, Task Force guidelines, tools and knowledge translation at completion of the pilot. They also reported, among others, enhanced capacity to discuss Task Force guidelines with colleagues and patients, to apply the recommendations in their own practice, and to identify and address barriers to implementation after the completion of the pilot.

Partners and stakeholders are aware of products and use them in their practice

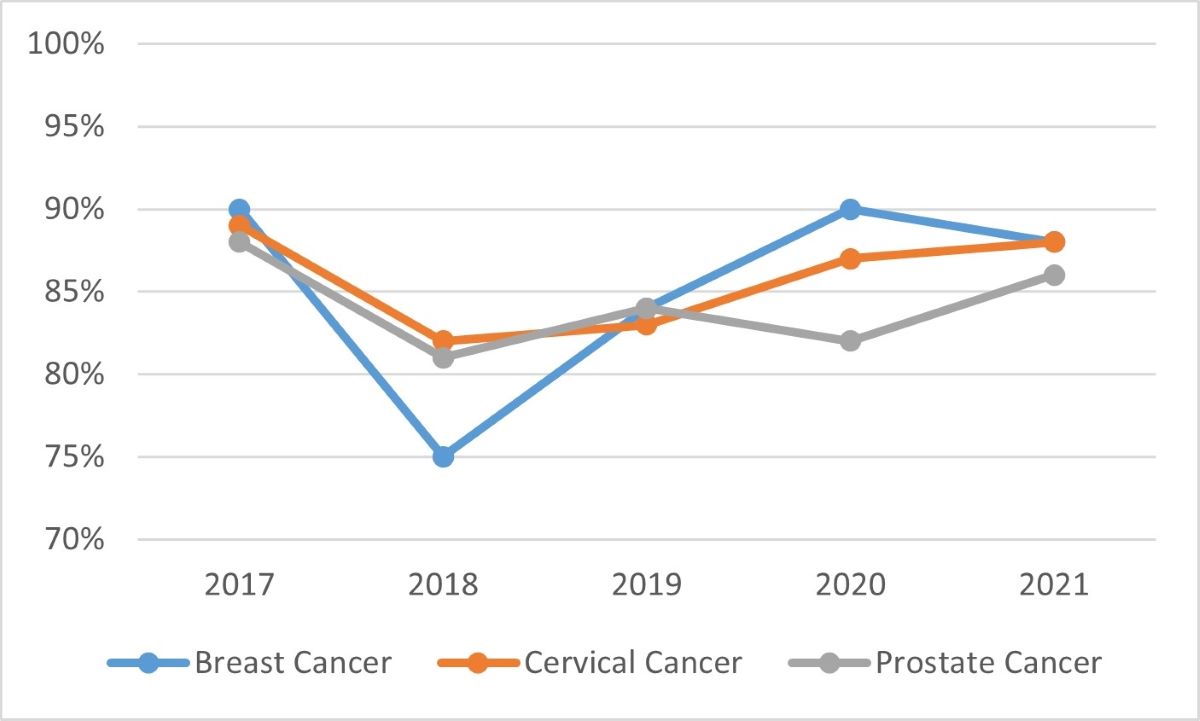

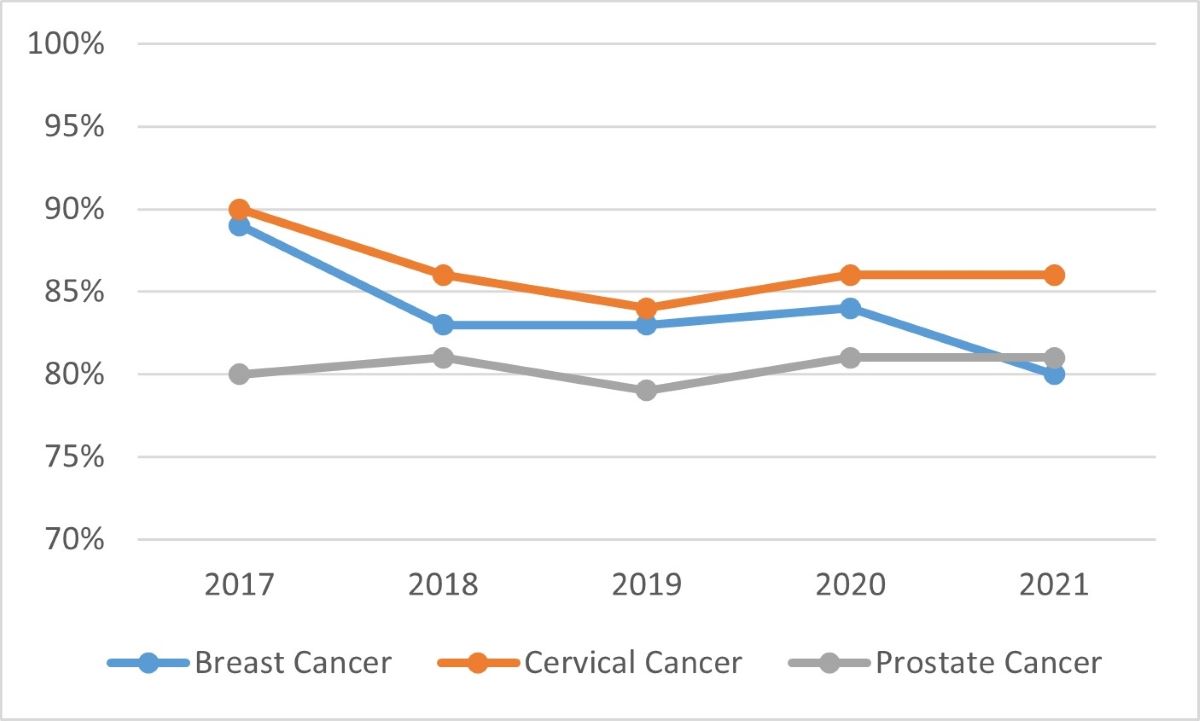

The annual evaluations conducted by the Knowledge Translation team measured awareness, satisfaction and impact of Task Force guidelines. See Appendix 4 for further details. From 2017 to 2021, three cancer screening guidelines were tracked, and as can be seen by the following two graphs, awareness and satisfaction were consistently high.

Source: Task Force annual evaluations

Graph 1 - Text description

Graph 1 is a line graph showing the awareness of three Task Force guidelines from 2017 to 2021. The three guidelines include: breast cancer, cervical cancer, and prostate cancer. Breast cancer is represented by a blue line, cervical cancer is represented by an orange line, and prostate cancer is represented by a grey line. The results in the graph are as follows:

Awareness of the breast cancer guideline was at 90% in 2017, 75% in 2018, 84% in 2019, 90% in 2020, and 88% in 2021.

Awareness of the cervical cancer guideline was at 89% in 2017, 82% in 2018, 83% in 2019, 87% in 2020, and 88% in 2021.

Awareness of the prostate cancer guideline was at 88% in 2017, 81% in 2018, 84% in 2019, 82% in 2020, and 86% in 2021.

Source: Task Force annual evaluations

Graph 2 - Text description

Graph 2 is a line graph showing the satisfaction of three Task Force guidelines from 2017 to 2021. The three guidelines include: breast cancer, cervical cancer, and prostate cancer. Breast cancer is represented by a blue line, cervical cancer is represented by an orange line, and prostate cancer is represented by a grey line. The results in the graph are as follows:

Satisfaction with the breast cancer guideline was at 89% in 2017, 83% in 2018, 83% in 2019, 84% in 2020, and 80% in 2021.

Satisfaction with the cervical cancer guideline was at 90% in 2017, 86% in 2018, 84% in 2019, 86% in 2020, and 86% in 2021.

Satisfaction with the prostate cancer guideline was at 80% in 2017, 81% in 2018, 79% in 2019, 81% in 2020, and 81% in 2021.

From 2017 to 2021, the majority of primary care practitioners surveyed either followed the Task Force guidelines or changed their practices to align with them. The range of respondents whose practice was already consistent with the Task Force guideline was as follows: breast cancer (44%-57%), cervical cancer (25%-47%), and prostate cancer (36%-51%) screening guidelines. As the table below outlines, notable proportions of respondents changed their practice to specifically align with various Task Force cancer guidelines following their release.

| Guideline | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | 47% | 49% | 32% | 29% | 41% |

| Cervical Cancer | 61% | 58% | 42% | 34% | 45% |

| Prostate Cancer | 47% | 53% | 36% | 38% | 42% |

| Source: Task Force annual evaluations | |||||

The annual evaluations also reported on the percentage of primary care practitioners who primarily use Task Force guidelines over other guidelines, or no guidelines. The range of practitioners using the cancer screening guidelines was as follows: breast cancer (33%-49%), cervical cancer (22%-34%), and prostate cancer (55%-66%).

Between 2017 and 2021, one to two years of data was available for the following published guidelines:

- Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm;

- Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Pregnancy;

- Hepatitis C;

- Impaired Vision;

- Prevention and Treatment of Tobacco Smoking in Children and Youth; and

- Thyroid Dysfunction.

There were significant variations in awareness and practice change levels among primary care practitioners:

- awareness ranged from 16% for the Prevention and Treatment of Tobacco Smoking in Children and Youth guideline to 63% for the Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening guideline;

- satisfaction ranged from 80% for the Prevention and Treatment of Tobacco Smoking in Children and Youth guideline to 87% for the Thyroid Dysfunction guideline;

- primary care practitioners whose practice was already aligned with these guidelines ranged from 23% for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening to 62% for Thyroid Dysfunction;

- primary care practitioners who intended to change their practice to align with the guidelines ranged from 22% for the Impaired Vision guideline to 53% for HCV Screening; and use of Task Force guidelines over other guidelines ranged from 16% for the Impaired Vision guideline to 51% for the Thyroid Dysfunction guideline.

The annual evaluations reported factors affecting primary care practitioners' use of the guidelines, including the following:

- public and practitioner awareness,

- patient preferences,

- perceptions of practicality and feasibility,

- accessibility of guidelines and tools, and

- lack of resources and local context, especially in northern and remote communities.

Anecdotal evidence of use and suggested improvements to enhance the usefulness of guidelines

Some external interviewees reported anecdotal stories of doctors using Task Force guidelines. There was also anecdotal evidence from a few internal and external interviewees that there has been good uptake of the cancer screening guidelines across PTs. A couple of external interviewees also noted that physicians have found the one-page summaries of guidelines useful for shared decision making.

According to a search of PT websites, the majority have links to at least one Task Force guideline. Task Force guidelines are also referenced on other association and organization websites (e.g., Canadian Partnership Against Cancer, Choosing Wisely Canada, College of Family Physicians of Canada).

Several interviewees noted that the main factor affecting the usefulness of the guidelines was their limited dissemination and this could be improved by increasing dissemination efforts, such as:

- Early engagement with professional associations (e.g., College of Family Physicians of Canada, nurse practitioners, physicians' assistants, medical schools and associations) and PTs could help increase awareness and use. Some external interviewees felt PHAC was best positioned to make these linkages with the PTs given existing federal, provincial and territorial relationships.

- Dissemination using social media may help reach some segments of the public, but may not be as useful for older Canadians who may not be as familiar with social media.

- A few internal and external interviewees suggested the guidelines could be incorporated into electronic health records as a means of increasing their reach and use. At the same time, they acknowledged that this would require a significant investment that is not currently available.

Suggested improvements to increase reach and use of guidelines

Recommendations from the annual evaluations to improve reach and use among primary care practitioners included the following:

- Patient engagement: Some participants indicated they would be more likely to trust guidelines that have taken patients' preferences into account. As a result, the Task Force created the TF-PAN to include the views of patients and the public.

- French presence: Task Force annual evaluations have repeatedly recommended increasing French presence on the Task Force. In response to these recommendations, the Task Force has added a French research coordinator to help increase its French presence.

- Provincial and territorial partnerships: Task Force annual evaluation participants reported that guidelines endorsed or supported by other organizations improved trustworthiness of the guidelines and encouraged adoption. To this end, an external interviewee noted that the Task Force has plans to prioritize provincial and territorial partnerships.

- Knowledge translation tools dissemination (e.g., email alerts and reminders, newsletters): About half of the annual evaluation survey respondents and interviewees suggested that there should be more consistent reminders through email updates or newsletters. These should not only be for new guidelines, but also for guideline reminders, as primary care practitioners may miss emails, given their busy schedules. An external interviewee reported that there are plans to increase dissemination, as well as the establishment of the CPL, whose purpose is to promote the uptake of Task Force guidelines and to address barriers to guideline implementation through educational outreach and knowledge translation activities. However, due to stagnant funding, there have been delays to phase 2 of the CPL pilot.

- App development: Some annual evaluation survey respondents and interviewees suggested that the Task Force develop a user-friendly app for easier access to guidelines. Primary care practitioners noted that the Task Force could learn from past challenges with a previous app to develop one with push notifications, alerting them of new guidelines that they could then implement into their practice. At the time of this evaluation, there was no evidence the Task Force had developed this new app.

- Website optimization: Annual evaluation survey respondents and interviewees identified that navigating the Task Force website can be challenging and that improvements could be made to improve usability for providers; for example, fewer clicks and PDF downloads. It appears the Task Force has improved the website; for example, by adding PDF downloads.

- Webinars and learning sessions: The Task Force holds webinars before guidelines are released; however, a few annual evaluation survey and interview participants suggested the Task Force explore the idea of hosting interactive webinars and learning sessions for practitioners following guideline releases. At the time of this evaluation, there was no evidence the Task Force had implemented interactive webinars and learning sessions.

The Task Force has made efforts to engage the Canadian public.

In 2020, the Task Force began developing a new patient engagement initiative to ascertain patient values and preferences in guideline development. The TF-PAN is an initiative to encourage early and meaningful public engagement, with the Task Force seeking their input throughout the development and dissemination of Task Force guidelines.

TF-PAN members are provided background information on Task Force activities and the types of methods and processes used to develop preventive health care guidelines, which is meant to ensure informed participation in guideline development. TF-PAN members form a stakeholder consultation group to provide input on various phases of guideline development, as determined by the guideline Working Group chairs, and based on need and guideline context.

The core TF-PAN group consists of about 20 members of the public who are trained in Task Force and preventive care theory. There is also an expanded network of over 75 members of the public who are not trained, but can still participate in ad hoc projects.

As previously mentioned, the TF-PAN was seen as a positive approach, and some interviewees noted that engaging patients and the public lends credibility to guideline recommendations. This group brings lived experience to the process and can help with wording that is more easily understood by the public. However, TF-PAN interviewees noted that the network has not yet been engaged in a significant way nor have they heard from the Task Force in quite some time.

The Task Force was not always able to meet its commitment of three guidelines per year.

The Task Force committed to producing three guidelines a year. While three were produced in both 2017 and 2018, only one guideline was produced per year in 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022 (to date). Several internal and external interviewees provided explanations for the decrease in guideline production, including:

- Task Force members were extremely busy with other priorities during the COVID-19 pandemic – they were required to participate in increased clinical activities;

- The sudden death of the Chair-elect sent the Task Force into crisis management mode;

- Turnover at the GHGD and some staff being redirected to work on pandemic activities led to delays in some processes; and

- A year-long pause on activities imposed by PHAC because workload exceeded capacity for all involved in producing guidelines.

A review of guidelines/recommendations published annually in the UK and US showed that over a four-year period, the UK published on average 16.75 recommendations, while over a six-year period, the US published on average 12 recommendations. However, the majority of US recommendations were updates and not full reviews. While, it is not clear how many of the UK recommendations came from updates or full reviews.

Several factors contributed to the length of time it took to produce guidelines.

The guideline development process was generally viewed as slow. While some internal and external interviewees noted the processes took too long, a few of them still felt that the guidelines were available when needed.

Internal and external interviewees noted that the following factors affected the timeliness of guidelines:

- Lack of remuneration for Task Force members affected members' ability to volunteer, since the Task Force requires a large time commitment from its members and some members are not in a position to give up as much time from their practices to participate;

- Task Force members were extremely busy with other priorities during the COVID-19 pandemic;

- Too many internal reviews;

- Too many meetings; and

- Length of time it took to draft scoping questions.

Interviewees suggested improvements in timelines could be achieved through:

- Expanded monitoring of timelines by PHAC; and

- Exploring options to adjust the model (e.g., use of rapid reviews and living syntheses). Other interviewees noted that these approaches are not without their own set of challenges; for example, rapid reviews can lead to shortcuts in scientific merit, an experienced team is required to ensure important literature is not missed, and living reviews take an enormous level of effort and may not be feasible for the Task Force.

The Task Force is aware of the need to improve the timeliness of its activities, which is why it has engaged an external expert to undertake a review of its processes and timelines.

Conclusions

Overall, there is evidence that Task Force guidelines were developed with the help of a wide variety of internal and external partners and stakeholders, who bring a balanced mix of clinical and methodological expertise to the process. Even so, there are some gaps in the development process, namely a lack of representation for Indigenous people, rural and remote physicians, and nurse practitioners.

In addition to expertise, the ERSCs use the GRADE method in their evidence reviews, which is considered the international standard in this area.

Governance processes and roles and responsibilities were generally well established to help support guideline development. However, there was some confusion around PHAC's role versus that of the ERSCs particularly in regards to scoping and carrying out evidence reviews. The Task Force has maintained its independence from outside organizations largely through its use of a strong conflict of interest policy.

There was evidence that the large amount of knowledge translation activities helped raise awareness of the guidelines and knowledge translation tools and resources. There was also some evidence of use and impact on practice. However, the guideline process was seen to be slow, and for the last three years the Task Force was not able to meet its commitment of producing three guidelines a year. Increased dissemination could help enhance the use and impact of the guidelines.

Funding challenges have affected the Task Force's ability to expand its dissemination activities and recruit certain types of primary care professionals.

Recommendations

The evaluation reviewed a number of lines of evidence, including file and document reviews, performance data reviews and interviews with internal and external interviewees. As a result, three recommendations emerged.

Recommendation 1: Explore ways to improve the timeliness of the guideline development process.

The Task Force committed to producing three guidelines per year; however, it has not met this target since 2018. Several factors have affected the Task Force's ability to produce its guidelines, including the sudden death of the incoming Chair, turnover at GHGD, increased workloads, and Task Force members' and GHGD staff's involvement in the COVID-19 pandemic response. All of this led to delays in guideline development. Other factors affecting the timeliness of guidelines included an inability of some Task Force members to volunteer due to a lack of remuneration too many internal reviews, too many meetings, and the length of time it took to draft scoping questions. PHAC in consultation with the Task Force should continue to explore ways to improve the timeliness of the guideline development process to ensure it meets its goal of producing three guidelines a year.

Recommendation 2: Given challenges, explore potential changes to address funding issues and adapt the Task Force funding model appropriately:

- Examine potential compensation for Task Force members, which may help to diversify the current composition of the Task Force.

- Examine ways to prioritize or optimize activities within available funding.

The lack of compensation for members affects the Task Force's ability to recruit new members. Without such compensation, some health care professionals such as rural and remote physicians are unable to participate. The lack of compensation has also limited the amount of time members can devote to Task Force activities, affecting overall timeliness.

PHAC is the sole funder of Task Force activities and most interviewees felt it should remain so as it helps to avoid the possibility that outside organizations could compromise the independence of the Task Force. At the same time, funding amounts have remained largely unchanged while salaries and planned activities have increased because of efforts to increase awareness and use as well as involve the public as part of the guideline development process. This has resulted in Task Force partners (ERSCs and the Knowledge Translation program) needing to reduce certain activities and cut the number of employees they can retain.

Recommendation 3: Clarify PHAC's role versus that of the ERSCs with respect to scoping and conducting systematic reviews.

While roles and responsibilities were clearly outlined in Task Force documents such as the Methods Manual; there continued to be some confusion around PHAC's role versus that of the ERSCs. PHAC works closely with the ERSCs, providing scientific and technical support; however, there is a lack of clarity around PHAC's role in scoping and conducting systematic reviews. For some this role was clear, but others felt PHAC was too involved in the reviews that were seen as an ERSC responsibility.

Management Response and Action Plan

Evaluation of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care - 2017-18 to 2021-22

Recommendation 1

Explore ways to improve timeliness of the guideline development process.

Management response

Management agrees.

- Timely guideline development is of utmost importance in order to remain responsive to evolving evidence and to ensure guidance is useful. At the same time, it is important not to sacrifice methodological rigor. We are aware that other guideline organizations are also exploring methods for reducing guideline workload, for example, using technological and methodological advancements.

- We are also aware that the Task Force is currently planning an internal review of their processes with support from an external expert in guideline development.

- The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) has also begun reviewing guideline processes for which they are responsible (e.g., guideline scoping) and piloting new approaches (e.g., advance scoping of upcoming topics when feasible).

Action Plan

| Deliverables | Expected Completion Date | Accountability | Resources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Identify and propose options to the Task Force to address guideline development tasks at high risk for delay. |

Report comparing scoping timelines (from guideline initiation to final scoping document) using traditional approach versus piloted approach using student support to carry out advanced scoping research for upcoming topics. Report will also include analysis of advantages/disadvantages of this approach, lessons learned, and recommendations for next steps. |

November 2023 |

Executive Director, CCDPHE |

Existing resources |

Report of expected versus observed timelines for key guidelines steps tracked in Microsoft Project, with retrospective examination of common factors leading to longer than anticipated timelines, with options for addressing identified factors. |

March 2024 |

Executive Director, CCDPHE |

Existing resources |

Recommendation 2

Given challenges, explore potential changes to address funding issues and adapt the Task Force funding model appropriately:

- Examine potential compensation for Task Force members, which may help to diversify its current composition.

- Examine ways to prioritize or optimize activities within available funding.

Management response

Management agrees.

- Since the creation of the Task Force ten years ago, science, methods and knowledge translation have evolved and are more complex.

- Expectations for knowledge mobilization and public participation have increased, which requires resources.

- The time required for participation on the Task Force, without compensation, is a barrier to recruitment for those who do not have academic positions.

| Deliverables | Expected Completion Date | Accountability | Resources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Investigate the types of compensation models available. Examine funding required for all activities and compare with other guideline organizations such as the US Preventive Services Task Force. |

Report of potential compensation options with a recommendation for a preferred option. |

May 2023 |

Executive Director, CCDPHE |

Existing |

Report on original activities funded vs current activities to identify funding gap with a recommendation to Senior Management about possible new funding sources or reallocation or reprioritizations of activities. |

November 2023 |

Executive Director, CCDPHE / VP, HPCDP |

Existing |

Action Plan

Recommendation 3

Clarify PHAC's role versus that of the ERSCs with respect to scoping and conducting systematic reviews.

Management response

Management agrees.

- Clarity of roles for ERSC and PHAC staff in supporting the Task Force is important given similarity of certain tasks (e.g., scoping searches versus systematic review searches).

- Both PHAC and ERSCs have experienced recent staff turnover highlighting the importance of having clearly documented roles and responsibilities across the guideline development process.

Action Plan

| Deliverables | Expected Completion Date | Accountability | Resources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Review and update guideline methods documents, and project management tools in collaboration with ERSCs, to ensure they clearly outline responsibilities. |

Publication of updated Task Force methods manual, clearly outlining areas of responsibility for PHAC and the ERSCs, with key chapters reviewed by ERSC staff. |

March 2023 |

Executive Director, CCDPHE |

Existing |

MS Project management platform updated with key guideline steps laid out, with responsible party indicated for each step. |

November 2023 |

Executive Director, CCDPHE |

Existing |

|

Meet with ERSC staff to review the updated methods manual and hold an open discussion with respect to clarity of roles/responsibilities, with a goal of identifying and clarifying ambiguities, and co-developing solutions. |

Records of decision from one initial meeting and at least one subsequent follow-up meeting, to be distributed to GHGD staff, ERSC staff, and Task Force leadership. This will include suggested role clarifications, changes to processes, and any recommendations for updates of the relevant Methods Manual chapter(s). |

April 2023 (initial meeting) December 2023 |

Executive Director, CCDPHE |

Existing |

Appendix 1 - Data collection and analysis methods

Evaluators collected and analyzed data from multiple sources. Data collection started in May 2022 and ended in July 2022. Data were analyzed by triangulating information gathered from the different methods listed below. The use of multiple lines of evidence and triangulation were intended to increase the reliability and credibility of the evaluation findings and conclusions.

Performance Data Review

The evaluation reviewed a series of annual evaluation reports conducted by the Knowledge Translation team to inform findings related to effectiveness.

Key Informant Interviews

Key informant interviews were conducted to gather in-depth information related to governance, funding, methodology, expertise, and effectiveness. Interviews were conducted based on a predetermined interview guide. In total, 23 interviews were conducted with 29 respondents. Respondents included:

- Internal: program staff (n=five interviews with six staff, including one written response)

- Task Force members (n=three interviews with five members)

- Primary health care professionals (n=four interviews)

- Evidence Review and Synthesis Centres (n=three interviews with five representatives)

- Knowledge Translation team (n= two interviews with three representatives).

- Other experts (n=four)

- Patients and members of the Canadian public (n=two)

Emerging themes from interviews were identified and quantified using NVIVO qualitative analysis software.

File and Document Review

Program file and document reviews included documents available on the Task Force website. Approximately 85 files and documents were reviewed.

Even though data collected by these various methods was analyzed by triangulation, the evaluation faced constraints that affected the validity and reliability of evaluation findings and conclusions. The table below outlines the limitations encountered during the implementation of the selected methods for this evaluation and mitigation strategies put in place to ensure that the evaluation findings are sufficiently robust.

| Limitation | Impact | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

Use of secondary performance data (annual evaluations) |

Relying on evaluations conducted by others made it more challenging since we were not involved in the development of those evaluation questions and areas of examination. |

Triangulation with other lines of evidence were used to augment available data. |

Key informant interviews are retrospective in nature, providing only a recent perspective on past events. |

This can affect the validity of assessments of activities or results that may have changed over time. |

Triangulation with other lines of evidence substantiated or provided further information on data captured in interviews. Document review also provided corporate knowledge. |

The evaluation considered the SGBA+ lens in its assessment of Task Force activities, including a discussion of equity issues in the development of guidelines. Although official languages were not specifically examined, they were not found to be an issue for the program's activities. Furthermore, an examination of the Sustainable Development Goals was not applicable for this evaluation.

In conducting the evaluation, a single window was identified from the Global Health and Guidelines Division, with whom the Office of Audit and Evaluation worked closely throughout the evaluation. The scope for this evaluation was shared secretarially with the Performance Measurement and Evaluation Committee (PMEC) in June 2022. The preliminary findings were presented at PMEC on September 28, 2022, and the final report will be presented at PMEC in December 2022.

Appendix 2 - Comparison with similar organizations in the UK and USFootnote 16, Footnote 17, Footnote 18, Footnote 19

| Key Criteria | The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care | US Preventive Services Task Force | UK National Screening Committee |

|---|---|---|---|

Compensation |

Voluntary panel |

Volunteer panel Footnote 20 |

Voluntary panel |

Number of members |

15 (10 members at time of evaluation) |

16 Footnote 21 |

18 (on average between 2017 and 2021) |

Number of guidelines produced annually |

1.7 |

12 Footnote 22 |

16.75 Footnote 23, Footnote 24, Footnote 25, Footnote 26 |

Process |

GRADE |

Does not use GRADEFootnote 27 |

Does not appear to use GRADE Footnote 28 |

Budget |

$2 million per year |

$11.5 million per year |

£3.6 million per year |

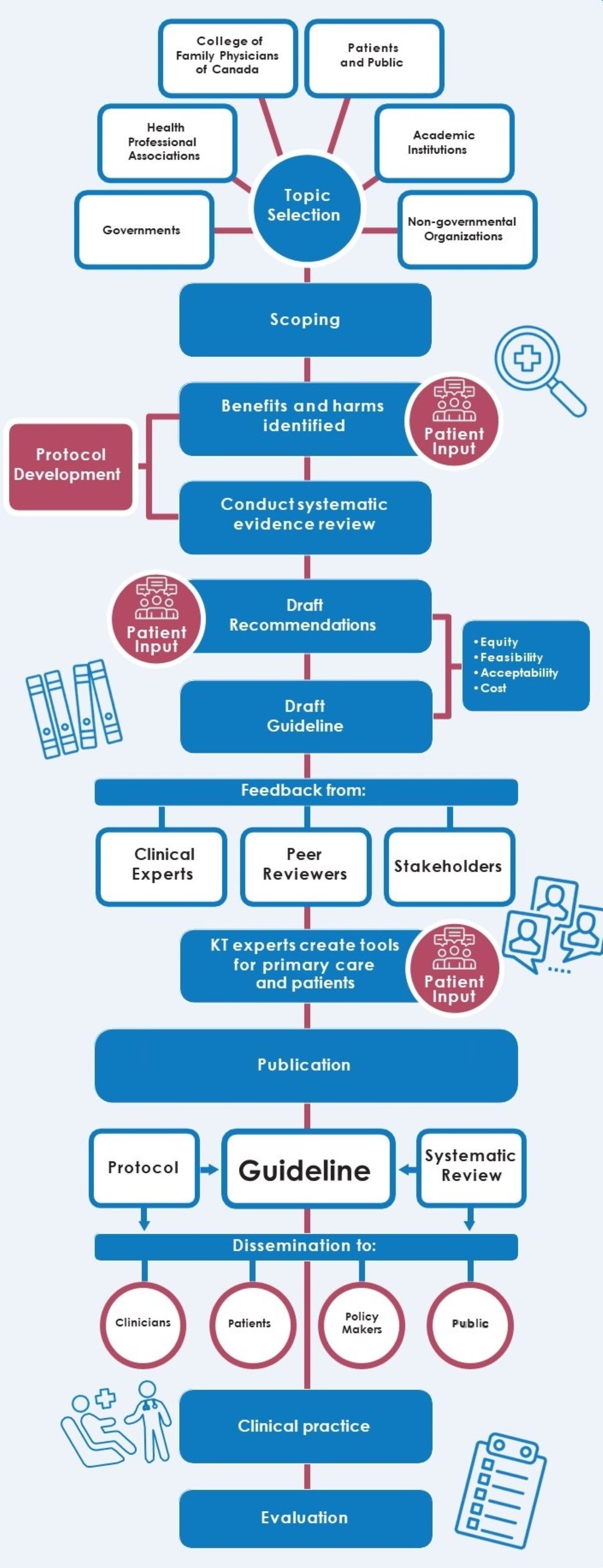

Appendix 3 - Task Force guideline development process – Methodology

Source: Canadian Task Force of Preventative Health Care

Appendix 3 - Text description

This process flow chart illustrates the Task Force guideline development process. Each step of the process is written in a blue block and the steps following are placed directly underneath. The steps are connected by red and blue lines.

The guideline development process begins with topic selection. Topic selection is written inside a blue circle and is centered in the middle of the flow chart. There are six lines around the circle pointing to six different white blocks. Each block represents the different partners the task force receives input from when selecting a topic. The blocks are labeled as follows: Governments; Health Professional Associations; College of Family Physicians of Canada; Patients and Public; Academic Institutions; and Non-governmental Organizations.

After the working group selects a topic, the next step of the guideline development process is the scoping phase.

The following step of the guideline development process is identifying any benefits and harms. The task force working group receive input from patients, and with this input, they develop a review protocol. The icon for this step is an outline of three people with text boxes over their heads.

The next step is conducting a systematic evidence review. Findings from the review will also help develop the task force review protocol. Protocol development is written in a red block and connects the benefits and harms block with the systematic evidence review block.

The following step of the guideline development process is to draft recommendations. The task force working group drafts recommendations with input from patients. The icon for this step is an outline of three people with text boxes over their heads.

The next step is to draft the guideline. When drafting the recommendations and the guideline, the task force working group must consider equity, feasibility, acceptability, and cost.

The following step of the guideline development process is to receive feedback from clinical experts, peer reviewers, and stakeholders. The icon for this step is an outline of three text boxes with an outline of a person within each box.

After the task force working group receives feedback from partners and makes the necessary changes to the guideline, they proceed to the next step. Knowledge translation experts create tools for primary care practitioners, and they do this with the input of patients. The icon for this step is an outline of three people with text boxes over their heads.

The following step of the guideline development process is the publication of the guideline. The Evidence Review and Synthesis Centre independently conducts a systematic review of the available evidence based on the final approved protocol.

The next step of the guideline development process is to disseminate the guideline to key partners including: clinicians, patients, policy makers, and the public. Each of these key partners are written inside a white circle.

After the guideline is disseminated, the recommendations of the guideline are implemented in clinical practice. The icon for this step is an outline of a patient who is sitting in a chair and their healthcare provider, who is wearing a stethoscope, is greeting them. There is a hospital cross placed above them.

The final step in the guideline development process is an evaluation. This evaluation is conducted by the Knowledge Translation Program at St. Michael’s Hospital. The purpose of the evaluation is to assess the impact and uptake of the Task Force’s clinical practice guidelines, knowledge translation tools, and knowledge translation resources. The icon for this step is a paper attached to a clipboard. The paper has check boxes on the left-hand side and writing on the right-hand side.

Appendix 4 - Knowledge translation

| Guideline | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Breast Cancer |

90% |

75% |

84% |

90% |

88% |

Cervical Cancer |

89% |

82% |

83% |

87% |

88% |

Prostate Cancer |

88% |

81% |

84% |

82% |

86% |

Prevention and Treatment of Tobacco Smoking in Children and Youth |

16% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

HCV Screening |

38% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening |

63% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Asymptomatic Bacteriuria |

N/A |

33% |

48% |

N/A |

N/A |

Impaired Vision |

N/A |

17% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Thyroid Dysfunction |

N/A |

N/A |

62% |

44% |

N/A |

Esophageal Adenocarcinoma |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

27% |

N/A |

Chlamydia and Gonorrhea |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

53% |

Awareness: the percentage of respondents aware of Task Force guideline |

|||||

| Guideline | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Breast Cancer |

33% |

49% |

38% |

44% |

42% |

Cervical Cancer |

22% |

29% |

23% |

32% |

34% |

Prostate Cancer |

55% |

59% |

59% |

66% |

66% |

Prevention and Treatment of Tobacco Smoking in Children and Youth |

22% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

HCV Screening |

44% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening |

49% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Asymptomatic Bacteriuria |

N/A |

31% |

38% |

N/A |

N/A |

Impaired Vision |

N/A |

16% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Thyroid Dysfunction |

N/A |

N/A |

51% |

48% |

N/A |

Esophageal Adenocarcinoma |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

37% |

N/A |

Chlamydia and Gonorrhea |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

37% |

Use: the percentage of respondents who primarily use Task Force guidelines over other guidelines or no guidelines |

|||||

| Guideline | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Breast Cancer |

89% |

83% |

83% |

84% |

80% |

Cervical Cancer |

90% |

86% |

84% |

86% |

86% |

Prostate Cancer |

80% |

81% |

79% |

81% |

81% |

Prevention and Treatment of Tobacco Smoking in Children and Youth |

80% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

HCV Screening |

83% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening |

86% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Asymptomatic Bacteriuria |

N/A |

83% |

83% |

N/A |

N/A |

Impaired Vision |

N/A |

83% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Thyroid Dysfunction |

N/A |

N/A |

86% |

87% |

N/A |

Esophageal Adenocarcinoma |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

86% |

N/A |

Chlamydia & Gonorrhea |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

84% |

Satisfaction: the percentage of respondents satisfied with the guideline |

|||||

| Guideline | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Breast Cancer |

45% |

44% |

51% |

57% |

53% |

Cervical Cancer |

27% |

25% |

37% |

47% |

40% |

Prostate Cancer |

36% |

41% |

37% |

51% |

47% |

Prevention and Treatment of Tobacco Smoking in Children and Youth |

33% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

HCV Screening |

30% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening |

23% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Asymptomatic Bacteriuria |

N/A |

49% |

42% |

N/A |

N/A |

Impaired Vision |

N/A |

46% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Thyroid Dysfunction |

N/A |

N/A |

62% |

N/A |

N/A |

Esophageal Adenocarcinoma |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

51% |

N/A |

Chlamydia and Gonorrhea |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

35% |

Consistency with current practice: the percentage of respondents whose practice was already consistent with the Task Force guideline |

|||||

| Guideline | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Breast Cancer |

47% |

49% |

32% |

29% |

41% |

Cervical Cancer |

61% |

58% |

42% |

34% |

45% |

Prostate Cancer |

47% |

53% |

36% |

38% |

42% |