Archived Evaluation of the Innovation Strategy 2014-15 to 2018-19

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 1.76 MB, 49 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Published: February 2020

Prepared by

the Office of Audit and Evaluation

Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada

February 2020

Table of contents

- Executive summary

- Management Response and Action Plan

- 1.0 Evaluation Scope

- 2.0 Program Profile

- 3.0 Ongoing Importance of Supporting Health Promotion in Priority Areas

- 4.0 Evidence of Program Success

- 5.0 Elements of an Innovative Program

- 6.0 Program Efficiency

- 7.0 Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix 1 – Evaluation Scope and Approach

- Appendix 2 – Data Collection and Analysis Methods

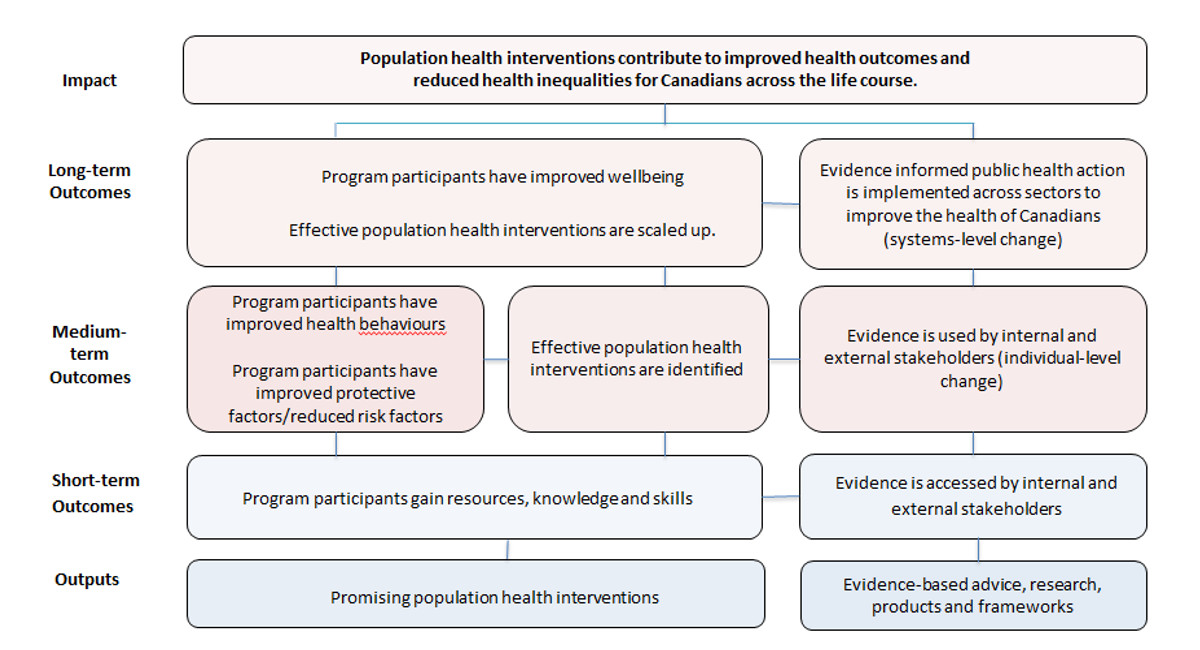

- Appendix 3 – Logic Model

- Appendix 4 – Innovation Strategy Phase Two Projects that Received Phase Three Funding

- Appendix 5 – Innovation Strategy Phase Two Projects (No Phase Three Funding)

- Appendix 6 – Intervention Scale-Up Assessment Criteria

List of Figures and Tables

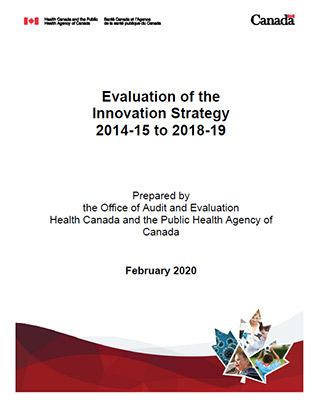

- Figure 1: Innovation Strategy Funding Phases

- Table 1: Comparison of Phase 2 Project Scale-up Readiness Assessments and Phase 3 Funding

- Table 2: Planned Spending and Expenditures 2014-15 to 2018-19

- Table 3: Evaluation Issues and Questions

- Table 4: Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

- Figure 2: Innovation Strategy Logic Model

- Table 5 - Innovation Strategy: Equipping Canadians – Mental Health throughout Life

- Table 6 - Innovation Strategy: Achieving Healthier Weights in Canada's Communities

- Table 7 - Innovation Strategy: Equipping Canadians – Mental Health throughout Life

- Table 8 - Innovation Strategy: Achieving Healthier Weights in Canada's Communities

List of Acronyms

- CCHS

- Canadian Community Health Survey

- F/P/T

- Federal, provincial, and territorial

- O&M

- Operations and Maintenance

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- P/Ts

- Provinces and Territories

Executive Summary

In 2009-10, the Centre for Health Promotion within the Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch at the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) launched the Innovation Strategy. The program has a current allocation of approximately $6 million annually, and was designed to test, deliver, and evaluate population health interventions to determine how they bring about change, the context in which they worked best, and for which populations. Through intersectoral project partnerships, knowledge exchange activities, and scaling up of successful interventions, the program aimed to ensure that effective and sustainable interventions would benefit as many individuals as possible within the population of interest.

The program funds projects in two streams (mental health promotion and healthy weights) with the goal of reducing health inequities and addressing complex priority public health issues and their underlying factors.

What we found

In examining PHAC’s activities over the last five years, it is clear that the program is making significant progress in supporting the development, adaptation, implementation, and evaluation of promising population health interventions.

Intervention research generates knowledge of effective public health approaches. Projects in both streams improved the factors that help protect the health of participants while reducing risk behaviours. There was evidence that participants’ health behaviours improved as well. Furthermore, knowledge regarding successful interventions was shared and used by a range of stakeholders.

Partnerships were an integral component of the Innovation Strategy and important to the success of the projects in terms of delivery, implementation, scale-up, and sustainability. Data collected during the evaluation showed that at least half of the project partnerships that were developed have been sustained for three years or more.

Most key informants noted that the Innovation Strategy was unique in its approach to funding interventions, with features that distinguished it from other PHAC funding programs at the time, such as the length of funding that helped create systems-level changes versus individual change, the focus on evidence generation, evaluation, and scaling up of promising interventions, as well as using a phased approach to funding and building flexibility into the projects and the program that allowed for course corrections along the way. The success of this model resulted in other programs within the Centre for Health Promotion adopting similar elements into their own programs.

Additional efficiencies were found at the project and program levels. Current project performance data showed that the vast majority of projects in both streams had leveraged additional resources (e.g., financial, in-kind). The next iteration of the Innovation Strategy, called the Mental Health Promotion Innovation Fund, will focus only on the theme of mental health, in alignment with the Centre’s broader mental health focus. It is anticipated that this will contribute evidence for future policy development in mental health promotion.

What we learned

The evaluation has identified one recommendation, as the program has already taken steps to mitigate most of the minor challenges that were identified. Along with the recommendation, key aspects that have the potential to enhance the management of public health intervention projects have also been highlighted below for other PHAC programs to consider.

Key Aspects

- Having strong, vested partners was key to the delivery, implementation, scaling up, and sustainability of projects in both streams. These partnerships led to a two-way exchange of knowledge that was valuable in terms of improving practices.

- Incorporating evaluation expertise in each funded project ensured that interventions were tested to better understand the impacts of their activities, adding to the evidence base on effective approaches. The program provided support to project recipients to enhance their understanding of what is meant by “scale-up”. Therefore, projects were able to take the necessary steps to expand their interventions and enhance sustainability.

- The phased approach of the Innovation Strategy built in flexibility from the outset to allow the program to identify and learn from what is working and what is not at the end of each phase. This then allowed the program to make course corrections, as needed, to ensure the overall success of the program.

- It takes time to design, implement, adjust, and evaluate population health interventions. The length of funding (up to nine years) was seen as especially essential for this type of program, since projects are trying to create long-lasting system-level changes that can only be achieved through years of committed investment.

Recommendation

Recommendation 1: Considering the success of PHAC's activities to date, promote the Innovation Strategy, including the development, adaptation, implementation, and results of promising population health interventions.

The program has had a significant impact on the development, adaptation, implementation, and evaluation of promising population health interventions. The program has included a Knowledge Hub in the new Mental Health Promotion Innovation Fund. The Hub supports knowledge translation and the promotion of health intervention findings between projects and external partners and stakeholders, and supports intervention research for each project’s outcomes. The Innovation Strategy should also consider communicating the positive impacts it has achieved, by sharing the results and elements of public health intervention management more broadly, both within PHAC and the broader Health Portfolio, as well as with provinces, territories, and other partners and stakeholders. This would also include a focus on the program’s unique approaches to funding interventions, such as the length of funding that helped create systems-level changes versus individual changes, the focus on evidence generation, evaluation and scaling up of promising interventions, a phased approach to funding, and building flexibility into the projects and programs, allowing for course corrections along the way.

Management Response and Action Plan

| Recommendation as stated in the evaluation report | Response | Action Plan | Deliverables | Expected Completion Date | Accountability | Resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendation as stated in the evaluation report | Identify whether program management agrees, agrees with conditions, or disagrees with the recommendation, and why | Identify what action(s) program management will take to address the recommendation | Identify key deliverables |

Identify timeline for implementation of each deliverable | Identify Senior Management and Executive (DG and ADM level) accountable for the implementation of each deliverable | Describe the human and/or financial resources required to complete recommendation, including the source of resources (additional vs. existing budget) |

| Considering the success of PHAC's activities to date, promote the Innovation Strategy, including the development, adaptation, implementation, and results of promising population health interventions. | Management agrees with the recommendation. | Develop a knowledge mobilization plan for the dissemination of key knowledge products that promote the Innovation Strategy program model. | Knowledge mobilization plan that identifies key audiences; outlines processes to identify, develop, and disseminate knowledge products; and provides clear timelines. | June 30, 2020 | Vice-President, Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch |

Use resources from within the Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch |

| Carry out the activities outlined in the knowledge mobilization plan. | Key knowledge products are produced and disseminated as per the knowledge mobilization plan and are anticipated to continue beyond 2021. | December 30, 2021 and ongoing | Director General, Centre for Health Promotion, Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch |

1.0 Evaluation Scope

The purpose of the evaluation was to assess the activities of the Public Health Agency of Canada’s (PHAC) Innovation Strategy for the period of April 2014 to March 2019. This program was last evaluated in 2015.

More detailed information about the evaluation design and methodology can be found in Appendix 1.

2.0 Program Profile

It has become increasingly recognized that complex public health issues require a population health approach that addresses multiple determinants of health, including social, economic, and environmental factors across multiple sectors, to create change at the population level. The Innovation Strategy is a national contribution program that was launched in 2009-10 to test and deliver evidence-based population health interventions.Footnote 1

To realize the overall goal of contributing to improved health outcomes and reduced health inequalities for Canadians, the program supports the development of promising population health interventions. Participants in projects enhance their knowledge and skills, which will help them deal more effectively with stressful events and result in improved health behaviours and overall wellbeing. At the same time, the program intends to develop evidence-based research and advice for public health practitioners who can use this information to inform their own policies and practices to improve the health of Canadians. The logic model for the program can be found in Appendix 3.

The Innovation Strategy has used a population health intervention research approach. Intervention research generates knowledge on multiple components of an intervention including the design, development, and delivery. It also accounts for the context (social, organizational, and political settings) in which the intervention is delivered, which influences the effectiveness of an intervention and the ability to scale it up (i.e., maximizing reach and sustainability). This approach aims to measure the impact of a public health policy or program in a deliberate and systematic way in order to assess the effectiveness of approaches to complex public health issues. This knowledge can help the equal distribution of positive health outcomes across a given population.

The Innovation Strategy has had an annual average of approximately $6.2 million to fund projects that generated knowledge and evidence to improve health and health equity at the population level.Footnote 2 The Centre for Health Promotion within the Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch is responsible for the Innovation Strategy at PHAC.

A phased approach

The Innovation Strategy has provided multi-year funding, focusing on northern and remote communities, children and youth, and those with low incomes. Based on project success and resource capacity, among other criteria, projects have progressed through the following phases (actual timelines for each of the three phases is presented in Figure 1 below):

- Phase 1: initial design, development, testing, and delivery of interventions (approximately 12 months);

- Phase 2: full implementation, adaptation, and evaluation of comprehensive population health interventions across multiple populations, communities, and settings (up to 4 years); and

- Phase 3: scale-up, expansion of the reach and impact of interventions to benefit additional communities and populations across Canada (over 3 years).Footnote 3

Source: internal documents

Figure 1 - Text description

Projects were funded by the Innovation Strategy under two streams called Equipping Canadians – Mental Health Throughout Life, and Achieving Healthier Weights in Canada's Communities. Funding is provided through three progressive phases:

- Phase 1, the initial design phase of approximately 12 months, occurred for mental health promotion projects over 2009-10 and for healthy weights projects during 2011.

- Phase 2, the implementation phase of up to 48 months, for mental health promotion projects lasted from 2011 to 2015 and for healthy weights projects from mid-2012 to mid-2016.

- Phase 3, the scale-up phase over 36 months, for mental health promotion projects started in 2015 and ended in March 2018; and for healthy weights projects started in 2017 and ends in March 2020.

Several key characteristics make the Innovation Strategy unique, including:

- investing in large-scale projects to allow enough time (up to 8 years) for development, implementation, knowledge development and exchange, as well as evaluation of the initiative;

- leading interventions and projects through community-based organizations that have partners with the expertise (including universities and researchers) to rigorously evaluate programs and produce high-quality evidence;

- adapting continuously to changing contexts;

- obtaining a deeper understanding of how interventions can evolve to better serve the diverse communities in which they operate; and

- joining multiple partners from a variety of sectors within and outside the health sector to support projects that influence policies affecting the broader determinants of health.

By the end of Phase 3, when Innovation Strategy funding ends, it is anticipated that projects will be well positioned to be sustained through other means, including other funding sources or by being embedded in an existing system, such as the educational system or provincial government programming.

Using this phased approach, the program has supported evidence-based population health interventions to reduce health inequalities in two priority areas: (1) mental health promotion and (2) healthy weights.Footnote a These priority areas reflect complex public health problems (obesity and mental illness) and were identified through internal and external consultation processes, existing evidence, and alignment with Agency and Branch priorities.

Mental health promotion

Funded mental health promotion projects focused on at least one of the following areas:

- family-level interventions, such as parenting skills and early childhood development;

- school-based interventions that teach social and emotional skills; and

- community-based interventions focused on supporting culturally safe and appropriate mental health promotion for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities.

A total of 15 mental health promotion projects were funded in Phase 1, with nine projects progressing to Phase 2, and four to Phase 3.

Healthy weights

Funded healthy weights projects focused on at least one of the following areas:

- food security: addressing access and availability of food, and related skills;

- school and family-based initiatives: support for early childhood and youth;

- northern community-based initiatives; and

- supportive social and physical environments.

A total of 37 healthy weights projects were funded in Phase 1, with 11 projects progressing to Phase 2, and seven to Phase 3.

Moving forward, the Innovation Strategy will focus on mental health only, and therefore has been renamed the Mental Health Promotion Innovation Fund. Internal key informants noted that this focus on mental health will create a stronger alignment between the Centre’s mental health policy work and the work of mental health interventions. Funded projects began in November 2019.

The second area, healthy weights, is being addressed by another PHAC national contribution program: the Multisectoral Partnerships to Promote Healthy Living and Prevent Chronic Disease Program. It aims to test and scale up the most promising primary prevention interventions that address common modifiable risk factors for chronic disease (physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour, unhealthy eating, and tobacco use).

3.0 Ongoing Importance of Supporting Health Promotion in Priority Areas

There is a continued need to address priority public health issues such as mental health and healthy weights, as the prevalence of mental illness and obesity remains high, and they continue to disproportionately affect vulnerable populations.

Health promotion is the process of enabling people to improve their health and increase their control over it.Footnote 4 Health promotion interventions aim to create supportive environments that help people develop skills, knowledge, and resilience to maintain and improve their physical and mental health.

Mental health

Positive mental health is the “capacity of each and all of us to feel, think, and act in ways that enhance our ability to enjoy life and deal with the challenges we face. It is a positive sense of emotional and spiritual wellbeing that respects the importance of culture, equity, social justice, interconnections, and personal dignity”.Footnote 5 Mental health is more than the absence of mental illness, meaning that a person can have a mental illness but still be capable of thriving and meeting life’s challenges (e.g., attending college, maintaining employment). A person can also be free of a diagnosed mental illness, but still experience mental distress (e.g., struggling to cope with a difficult life situation). Mental health promotion refers to the actions taken to strengthen mental health.Footnote 6Positive mental health is one strategy to prevent mental illness.

While mental health and substance use disorders remain widely under-reported, the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) reports that, in a given year, 6.7 million Canadians, or one in five people, experience mental illness. By age 40, that number increases to one in two.Footnote 7The prevalence of mental illness in Canada has also increased. In 2015, 7.9% of Canadians aged 12 and older, roughly 2.4 million people, reported that they had been diagnosed with a mood disorder by a health professional.Footnote 8,Footnote b This proportion increased slightly in 2016 (8.4%), and again in 2017 (8.6%).Footnote 9

Vulnerable populations

There are certain segments of the population that are more likely to experience poorer mental health:

- A higher percentage of females (10.7%) reported having a mood disorder compared to males (6.4%).Footnote 10

- These types of disorders are more common among Canadians aged 18-34.Footnote 11

- Indigenous people in Canada experience poorer mental health compared to non-Indigenous people.Footnote 12

- Canadians in the lowest income group are three to four times more likely than those in the highest income group to report poor-to-fair mental health.Footnote 13

- Studies in various Canadian cities indicate that between 23% and 67% of homeless people report having a mental illness.Footnote 14

- While socioeconomic factors play a key role in mental health and wellbeing for the population at large, they are particularly important for marginalized populations. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) individuals experience stigma and discrimination across their life spans, and are targets of sexual and physical assault, harassment, and hate crimes, which can affect their mental health.Footnote 15

Furthermore, people living with mental illness are at a higher risk of experiencing a wide range of chronic physical conditions, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, elevated levels of stress hormones and adrenaline, and respiratory conditions, among others.Footnote 16 Since mental and physical health are fundamentally linked,Footnote 17 people with mental illness and addictions are also more likely to die prematurely than the general population. Mental illness can reduce a person’s life expectancy by 10 to 20 years .Footnote 18

A recent report from the Canadian Mental Health AssociationFootnote 19 documented several factors that are expected to influence the ongoing burden of mental health in Canada:

- a rapid growth in the aging population (e.g., higher risk of mental illness in the context of developing a chronic disease);

- an increasing immigrant population (e.g., economic and social barriers, difficulty accessing culturally-appropriate mental health services); and

- a growing incidence of substance abuse disorders (e.g., the opioid crisis).Footnote 20 ,Footnote 21

Healthy weights

Promoting healthy weights and treating obesity are considered complicated issues that involve personal factors, as well as the social, cultural, physical, and economic environments of Canadians. It is clear, however, that obesity is a public health issue in Canada. Results from the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) have demonstrated that, since 2003, the proportion of Canadians who are obese has increased 17.5%.Footnote 22 In fact, the proportion of Canadians over the age of 18 who are overweight or obese has been steadily increasing since the 1970s. In 1978-79, 49% of adults were overweight or obese, which increased to 59% in 2004. As of 2017, this proportion has reached 64%.Footnote 23

Like the burden of mental health, the prevalence of obesity in Canadian adults is projected to continue to increase over the next two decades.Footnote 24 Research shows that obesity increases a person’s risk for a wide variety of diseases and conditions including hypertension and high blood pressure, coronary heart disease, Type 2 diabetes, stroke, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea and other breathing problems, some cancers (e.g., breast, colon, endometrial), as well as mental health problems such as low self-esteem and depression.Footnote 25

Vulnerable populations

Healthy weights among Canadian children and youth is an even greater concern, as obesity rates among this group have nearly tripled in the last 30 years.Footnote 26 Not only are weight issues in childhood likely to persist into adulthood, but also children and youth who are obese are at higher risk of developing a range of health problems including asthma, Type 2 diabetes, and heart disease.Footnote 27

Some other segments of the population are also at risk:

- Results from the 2012 CCHS found that, between the ages of 18 and 54, significantly more men than women were obese.Footnote 28 This difference has persisted over time with figures from the 2018 CCHS showing that the proportion of adult males who were obese was 28% as compared to 25.6% of females.Footnote 29

- Two studies of socioeconomic-related inequalities affecting obesity risk among Canadian adults found that obesity is more prevalent among economically disadvantaged women.Footnote 30,Footnote 31 Similarly, the rates of obesity were found to be greater for those with lower educational attainment, an effect that was also more pronounced for women than for men.Footnote 32

- A recent study found that Indigenous First Nations (26%), Inuit (26%) and Métis (22%) adults had higher obesity rates than non-Indigenous (16%) adults.Footnote 33

- Food insecurity, or a lack of physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food, is associated with a wide variety of health problems, including adult obesity.Footnote 34 Research has shown that people who are food insecure have diets with less variety, consume lower amounts of fruits and vegetables, and are more likely to have micronutrient deficiencies and suffer from malnutrition.

Aligning this program with PHAC’s mandate and priorities

Addressing mental health promotion, healthy weights, and health inequities continue to be long-standing federal priorities. The updated 2017 Minister of Health Mandate Letter noted that, when Canadians are in good physical and mental health, they can contribute more fully, while living healthier and happier lives. In August 2017, F/P/T Health Ministers (except Quebec’s) committed to work together to promote mental wellness and improve access to evidence-supported mental health services. The Government of Canada supports the health and wellbeing of all Canadians.Footnote 35 Within PHAC, positive mental health and healthy weights remain key priorities, as do reducing health inequities and generating evidence to inform action.

The program is aligned with PHAC’s public health role related to health promotion, knowledge sharing, and reducing inequities to improve health outcomes. PHAC’s role is well understood by stakeholders and is seen as complementary to that of others in these areas, even though this is an area of shared jurisdiction. When the Innovation Strategy was initially designed, consultations were held with F/P/T departments, as well as external stakeholders, to avoid duplication of activities or with existing initiatives.

Most key informants noted that PHAC’s role is complementary to the role of others within PHAC, the Health Portfolio, and other federal government departments. For example, PHAC can fund public health interventions, while the Canadian Institutes of Health Research can fund research supporting public health. Furthermore, the program addresses mental health and healthy weights through a health promotion lens, which differentiates it from the provincial and territorial government role of primary care.

4.0 Evidence of Program Success

The Innovation Strategy funded both mental health promotion and healthy weights projects, which targeted populations in need, including individuals, families, and communities, with a particular emphasis on vulnerable populations, including First Nations communities, children and youth, newcomers, and low-income populations. These projects were also directed towards population health practitioners, researchers, and policy makers. The goal was to support effective community-based interventions, as well as provide support to health professionals to enhance policy and practice.

With respect to meeting the needs of vulnerable populations, the mental health projects funded for Phase 3 centered on children, youth, and families, with efforts concentrated on bolstering protective factors, which are those conditions or attributes in individuals, families, and communities that help people deal more effectively with stressful events, such as resilience, family attachment, and youth engagement. For example, the Listening to One Another Grow Strong project centers on providing culturally-relevant suicide prevention and mental health promotion programs to Indigenous youth, who have the highest suicide rates among youth in Canada (see text box in section 4.2).

Similarly, Phase 3 healthy weights projects targeted food security as an issue area of relevance to vulnerable populations. Examples of projects include support for physical activity and healthy eating among youth, support for cooking workshops, and traditional and Indigenous food learning opportunities (see text box in section 4.2). For example, the Our Food Our Health Our Culture: Achieving Healthier Weights Through Healthy and Traditional Foods project in Manitoba and Saskatchewan benefited youth by providing them with the tools to adopt healthy traditional food skills, and participating organizations and agencies also saw the adoption of healthier eating habits among those taking part in initiatives. A descriptive list of Phase 2 and 3 projects can be found in Appendix 4 and Appendix 5.

4.1 Improved Health Behaviours and Wellbeing

Performance measurement data and project examples show that the majority of funded projects have already helped to improve health behaviours and wellbeing among participants.

Protective factors

Protective factors are the improved conditions or attributes in individuals, families, and communities that help people deal more effectively with stressful events.Footnote 36 These conditions or attributes help mitigate risks to a person’s mental and physical health, and can include family attachment, community connection, resiliency, physical activity, and healthy changes to diet.

By the end of Phase 2 in 2014-15, all mental health projects reported that there were changes in various protective factors among project participants. This trend continued for the projects funded in Phase 3 of the program, according to the most recent data collected. To a lesser extent, a similar trend existed for the healthy weights projects. By the end of Phase 2, 55% of healthy weights projects reported changes in these factors among participants, while the most recent data showed that 57% of healthy weights projects participants reported changes.

Some specific examples of changes in these factors include:

Mental health promotion

- Scaling Up Social and Emotional Learning Programs in Atlantic Canada: Teachers, administration, and school board representatives reported that many students were displaying enhanced emotional awareness (i.e., the ability to recognize and make sense of not just your own emotions, but also those of othersFootnote 37 ) following participation in the program.

- Listening to One Another to Grow Strong project: Although no baseline was available, participants discussed the impact of the program on various areas. For example, they felt that interest in their cultural heritage was greater following participation in the program. Furthermore, familial ethnic socialization (e.g., “my family teaches me about my Indigenous background”) and understanding ethnic identity (e.g., “I understand how I feel about being Indigenous”) improved following participation in the program.

- All the female and most of the male youth participating in The Fourth R project reported that they had increased their knowledge on healthy and unhealthy ways of dealing with stress. A two-year longitudinal study of the project’s Healthy Relationships Plus Program found that youth showed a decrease in depression at the end of the program, and youth with moderate to high anxiety showed significant improvement.

Healthy weights

- Our Food: From Pickles to Policy Change: 100% of participants in Cumberland County and 90% of participants in Cape Breton reported an increase in their access to healthy food through Cost-Share Local Food Boxes.

- Healthy Weights for Children: Over half (58.8%) of caregivers reported that Healthy Together was effective in helping participants feel connected to their community.

- Our Food Our Health Our Culture: Achieving Healthier Weights Through Healthy and Traditional Foods: Among participants in the Land-based Program (Summer Youth Program), an average of 91% of youth reported they had made a new friend at the session.

- Expanding the Impact and Reach of the Community Food Centre Model: 88% of participants reported that their Community Food Centre had provided them with an important source of healthy food.

Overall, in Year 1 of Phase 3 (2017-18), 71% of the healthy weights projects reported increased knowledge or skills among participants, compared to 81% of healthy weights projects across all of Phase 2. As for mental health projects, 50% of projects reported increased knowledge or skills in Year 2 of Phase 3 (2016-17).

Improved health behaviours

In 2015-16, a quarter (25%) of mental health projects reported positive changes in participant behaviour, whereas in 2017-18, this increased to three quarters (75%) of mental health projects. While funding is still ongoing, 71% of healthy weights projects reported positive changes in behaviour in 2017-18 (the latest data available).

Examples of changes in behaviour include:

Mental health promotion

- Scaling Up Social and Emotional Learning Programs in Atlantic Canada: Teachers, administration, and school board representatives reported that many students were displaying improved behaviours and use of effective emotional language following participation in the program. Facilitators reported that students were better able to manage interpersonal conflicts independently, self-regulate their behaviours, and consistently engage in pro-social behaviours following participation in the program. Furthermore, the Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies’ ‘turtle technique’Footnote c was viewed as beneficial, and some parents reported that their children were using it at home and teaching their siblings and family members how to calm down in difficult situations.

Healthy weights

- Expanding the Impact and Reach of the Community Food Centre Model project: 90% of participants in the Community Kitchens program were using the knowledge and skills gained in the project back at home.

- Our Food: From Pickles to Policy Change project: Before receiving Cost-share Local Food Boxes, 50% of participants reported eating fruits and vegetables once a day. Following the program, 83% of participants reported eating fruits and vegetables at least once a day.

- Our Food Newfoundland: Scaling up Nikigijavut Nunatsiavutinni (Our Food in Nunatsiavut): 69% of participants in the Hopedale Community Freezer Expansion Program indicated they had made healthy changes to their lifestyle since participating in the program.

Improved wellbeing

Improved wellbeing among project participants was reported for 25% of mental health projects in 2015-16 and for 75% of projects in 2017-18. The most recent data available (2017-18) shows that 28% of healthy weights projects reported improved wellbeing for participants.

Examples of improved wellbeing include:

Mental health promotion

- Listening to One Another to Grow Strong project: 58% of adults reported higher levels of emotional, psychological, and social wellbeing (according to the Mental Health Continuum) following participation in the program.

- The Fourth R project: A two-year self-reported longitudinal study of the University of Western Ontario’s Healthy Relationships Plus Program found that youth who had been highly depressed at the start of the program showed significantly decreased levels of depression by the end of the program. In addition, a group of youth experiencing moderate to high anxiety symptoms showed significant improvement.Footnote d

Healthy weights

- Healthy Weights for Children: Caregivers perceived improvements in their own quality of life following the Healthy Together Program: 70.7% reported they felt healthier, 54.7% reported they were happier, 46.7% reported they were less stressed, and 18.7% reported they had lost weight.

- Expanding the Impact and Reach of the Community Food Centre Model: Participants perceived improvements in wellbeing, as 56% noted an improvement in their physical wellbeing, and 56% felt their mental health had improved since attending programs at the Community Food Centres, while 83% of Indigenous participants perceived improvements in physical and mental health due to participating in programs at the Centres. Compared to the entire survey sample, a slightly higher percentage of program participants born outside of Canada perceived improvements in their physical health.

Although it is too early for documented evidence on reduced health inequities, internal key informants and funding recipients noted that projects from both streams had contributed to improved health outcomes and reduced inequities. However, a few internal PHAC key informants observed that the assessment of inequities was difficult for projects at the design and implementation stages because they have so many root causes. PHAC has developed guiding questions to help projects with this component, and this is anticipated to alleviate the challenges associated with the assessment of inequities.

4.2 Advancing Population Health Policies and Practices

As noted earlier, the program also intended to develop evidence-based research and advice for public health practitioners who could use this information to inform their own policies and practices to improve the health of Canadians. The development of knowledge products (presentations, position papers, research summaries, manuals, training kits, workshops, community and research events, communiqués, newsletters, brochures, pamphlets, posters, websites, reports on lessons learned, and articles in peer-reviewed journals) was a key element in this process. Once produced, it was expected that health practitioners, researchers, and other policy makers within and outside of the health sector would access and use these products to advance their respective population health policies and practices.

Projects in both streams developed and shared knowledge products, which were accessed and used by a range of stakeholders.

Project Spotlight: Listening to One Another to Grow Strong

Listening to One Another to Grow Strong is a community- and school-based project that promotes mental health and contributes to the prevention of suicide-related behaviours.

Participants in the project take part in workshops that build lessons around the following mental health promotion themes: socioemotional skills, anger management, child-parent communication, and handling peer pressure. Cultural appropriateness is a key objective and the curriculum has been adapted for First Nations to include their context, history, and languages.

The project’s Cultural Adaptation First Steps Model has been used by St. John Ambulance to facilitate the cultural adaptation of their new St. John Ambulance Connect Program to better reach and meet the unique needs and resources of Indigenous youth and their communities.

The 2016-17 Departmental Performance Report noted that surveys conducted by projects to measure knowledge use found that 45% of stakeholders indicated that they had used knowledge generated by projects. In addition, the program was able to identify 450 examples from 20 projects with completed Phase 2 funding that demonstrated how the knowledge produced was able to influence policies and practices at various levels of evidence-informed practice, as described below.

Looking first at examples of mental health projects, the Towards Flourishing project resulted in discussions with decision makers, with a focus on how the strategies identified in the project could be applied in additional sectors, such as the workplace. The Handle with Care project was cited as a project of note in the Yukon Territorial Wellness Initiative. The Ontario Human Rights Commission produced a report that was used by the Qikiqtani Inuit Association to inform child and family health strategies and programming in the region. The Fourth R project, which taught relationship skills to youth, influenced the design of Safe Schools legislation in the Northwest Territories.

Examples for Healthy Weights projects include the “Making Food Matter” research report that was shared with Nova Scotia’s Department of Health and Department of Agriculture. In addition, some or all of a Core Foods Policy (a policy delineating which healthy necessities are prioritized by food banks) was adopted by a food bank in Perth, Ontario and the organization communicated their needs to other local community-based organizations, companies, and grocers. The food bank saw healthy food donations rise by 25% from 2012 to 2013.

Funding recipients also offered examples of how knowledge was primarily shared and used to influence practice. Examples from mental health projects included organizations adapting their practices to be more culturally safe, and the creation of other programs using similar approaches. In one instance, a community-led mental health promotion project developed brochures, banners, fact sheets, infographics, journal articles, and a digital story. They adapted course curricula to ensure that cultural safety and culturally appropriate practices and principles would be available to other First Nation communities through the project network.

Healthy weights projects resulted in changes to physical activity and nutrition practices in child care centres, as well as improved community public safety practices. For example, the Healthy Weights for Children project reported in 2017-18 that 83% of caregivers contacted stated that they had learned about healthy foods to provide their families.

Project Spotlight: Expanding the Impact and Reach of the Community Food Centre Model

Expanding the Impact and Reach of the Community Food Centre Model supports community food centres in several cities across Canada. The centres provide healthy food, skill-building opportunities, and peer support in a welcoming and dignified environment.

The Canadian Food Centre Canada’s Good Food Organization program is helping community food security organizations change their programmatic or organizational policies. An annual assessment of the program demonstrated the following examples of internal policy change in member organizations:

- 49% of the Good Food Organizations created or deepened a healthy food policy that guides purchases and menu choices;

- 93% broadened their food programming to serve multiple objectives in the area of food access, food skills, and community engagement; and

- 73% increased material supports to enable low-income and marginalized people to participate in their programs.

Knowledge products used by other organizations included manuals, training kits, presentations, position papers, and websites. Some types of healthy weights knowledge products developed during Phase 2 were used by other organizations and stakeholders and include a “Community Food Mapping Toolkit” and a webinar for Aboriginal Food Security in Northern Canada. Another example, the Ecology Action Centre’s “Community Conversation Guide: Food Charter,” was used to facilitate conversations with communities and organizations about the draft ‘Food Charter’ for Halifax. It served as a guide to support discussions in practice forums and communities and was used to gather feedback, input, and actions people would like to see to improve food security in their communities. This resulted in changes to the draft ‘Food Charter’ (e.g., additions on Indigenous food sovereignty, fish, food labour). Finally, Our Food Newfoundland produced a report that informed the Food Secure Canada organization’s national food policy engagement plans.

These streams noted that it was more difficult to demonstrate how knowledge was used to influence policy, as opposed to practice, since organizations might not have had the “know-how” to use knowledge this way. To help funding recipients, PHAC hired a consultant to develop a Guide to Policy-Influence Evaluation: Selected Resources and Case Studies. Funding recipients could use this online tool to help plan and evaluate their policy-influence work, offering them a number of practical resources from groups that had already used them.Footnote 38

PHAC also engages in a number of activities to share project-based knowledge, broader lessons learned, and best practices, such as public reporting and stakeholder meetings.

Most internal, external, and funding recipient key informants noted that the Government of Canada played an important role in sharing information across levels of government, and had built partnerships with provinces and territories and external stakeholders to advance issues by sharing evidence of what is and is not working in various jurisdictions across the country.

The program shared lessons learned and best practices both internally and with external stakeholders. Internally, Innovation Strategy program staff made presentations and delivered workshops on project results, performance measurement, and evaluation methods used for projects. At the end of Phase 2, the program developed a lessons-learned report on mental health projects. This report incorporated lessons learned from all Phase 2 projects, including those that did not receive Phase 3 funding, and highlighted examples of what did or did not work, such as enhancing appropriate research and evaluation methods within Indigenous communities. Furthermore, projects that focused on interventions were more successful than those that focused on policy change. This lessons-learned report was shared within PHAC and used to develop other knowledge products (e.g., journal articles, conference presentations). There are also plans to develop a similar report for Phase 2 healthy weights projects.

The program also shared information with external stakeholders through presentations, annual reports, and meetings with funding recipients. For example, a one-day think tank was held with CIHR, Health Canada, and other experts on scale-up. Further, PHAC held face-to-face meetings with project recipients to exchange information and build relationships.

Other ways in which the program shared knowledge included one-page project summaries and case studies, presentations on successful approaches, and tools such as the Innovation Strategy Economic Assessment Background Document. This was done to further the lessons captured by the program, in hopes that they can be replicated by other programs, both within and outside of PHAC. This knowledge sharing was helpful in a number of ways, including assisting the Multi-sectoral Partnerships Program, another health promotion program within PHAC, to develop its Social Return on Investment tool. It also helped the Dementia Community Investment Fund incorporate information shared by the Innovation Strategy regarding language use with Indigenous populations, as well as helping to develop the wellness model used with Indigenous programs. Moreover, funding recipient and internal partner key informants noted the value of the program’s efforts to share knowledge, which helped to establish linkages with other Agency programs. Two internal key informants mentioned that any challenges of sharing program results internally stemmed from having two funding streams with different timelines. Moving forward with one funding stream should help focus efforts in this area.

Some internal key informants noted that the program had difficulties monitoring knowledge dissemination without a platform on which to share results. However, the Innovation Strategy recognized this gap and shared these lessons with the Supporting the Health of Survivors of Family Violence Program, who included a Knowledge Hub project in their funding. Based on this success, the Innovation Strategy has also included a Knowledge Hub in its new Mental Health Promotion Innovation Fund. The Knowledge Hub will be established at the University of Waterloo and help maximize the impact of the program by facilitating collaboration and knowledge sharing across funded projects, disseminating findings emerging from funded interventions, and bolstering the uptake of evidence into policy and practice.

Funded projects also showed extensive reach through the development of knowledge products and the delivery of knowledge exchange activities. By the end of Phase 2, 3,278 knowledge products and activitiesFootnote e had been developed by mental health promotion and healthy weights projects.Footnote f Among the populations reached were individuals facing specific risk conditions and factors, health care practitioners, professionals, and other service providers, policymakers, and members of the general public.

Mental health promotion

- By the end of Phase 2 (2014-15): 3,389,195 individuals had been reached

- During Phase 3 (2017-18): 55,168 additional individuals had been reached

Healthy weights

- By the end of Phase 2 (2016-17): 555,976 individuals had been reached

- During Phase 3 (2017-18): 74,975 additional individuals had been reached.

4.3 Partnerships

Partnerships were an integral component of the Innovation Strategy model and viewed as a contributor to success at multiple project stages. All projects from the mental health and healthy weights streams are engaged in multi-sectoral partnerships and recent data indicates that about half of project partnerships have been sustained for three years or more.

Partnerships were key to the success of Innovation Strategy projects in terms of delivery, implementation, scaling up, and sustainability. Partnerships have been specifically defined by the program and cover four different areas. Collaboration entails working together as one cohesive system with frequent communication, mutual trust, and consensus on all decisions. Cooperation entails sharing information between involved organizations, having roles that are “somewhat defined”, formal communication methods, and decision making that occurs independently among organizations. Coordination involves sharing information and resources, having defined roles, as well as frequent communications and some shared decision making. Finally, networking entails less frequent communication and independent decision making.

All projects in both streams reported being engaged in multi-sectoral collaborations with local Indigenous governments, provincial government departments, municipalities, academic institutions, and resource centres, where appropriate. It was recognized that partnerships would change and evolve over the lifecycle of projects, according to the priorities of each funding phase. For example, Phase 1 partnerships might focus on community engagement and relationship building, as well as seeking partners to assist with project implementation. Phase 2 partnerships would attempt to broaden “opportunities for impact and reach”. Finally, Phase 3 partnerships would expand on reach and impact by focusing on how to implement system-wide interventions.

Project Spotlight

Mental Health Promotion

Towards Flourishing formed partnerships with a wide variety of stakeholders, including provincial ministries of Health, regional health authorities, the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, and the First Nations Advisory Group, among others. Partners brought a wide range of experience, knowledge, and skills to the project, with the goal of expanding the Families First Home Visiting Program by promoting the mental wellbeing of parents and their families.

Healthy Weights

Active Neighbourhoods Canada/Réseau Quartiers verts: 60 stakeholders in health, transportation, planning, environment, social services, and research were engaged to assess community needs and create social and physical environments that lend themselves to active transportation in support of better health outcomes.

By the end of Phase 2 (2014-15), a total of 1,459 new and existing partnerships were reported: 506 for mental health and 953 for healthy weights. The most recent evidence showed that at least half of project partnerships were sustained for three years or more: 72% for mental health and 50% for healthy weights. During Phase 2, mental health projects had a total of 506 partnerships, of which 60% were with the public sector and 38% with the not-for-profit sector in the areas of education and health. Healthy weights projects had a total of 332 partnerships, with a relatively even split of public sector (46%) and not-for-profit sector (47%) partnerships. The remaining 7% were with private sector.

As of Phase 3, mental health projects reported 113 new and existing relationships were reported, with 53% reported as sustained for three or more years. The majority (73%) of partnerships were with the public sector, 20% with the not-for-profit sector, 1% with the private sector, and 6% with “other organizations”. Sixty-seven percent of partnerships were described as cooperative, 16% as collaborative, and 14% as involving coordination.

A similar pattern was exhibited for Phase 3 healthy weights partnerships, where 279 new and existing partnerships were reported, of which 50% were sustained for three of more years. Forty-three percent of partnerships were with the public sector, 46% with the not-for-profit sector, 5% with the private sector, and the remainder with “other” partners (6%). Most projects described their partnerships as involving either coordination (34%) or cooperation (38%).

The most recent data show that the majority of partnerships are with not-for-profit sector (35% of mental health and 46% of healthy weights) and the public sector (33% of mental health and 43% of healthy weights).

Internal and external key informants suggested that partnerships support knowledge dissemination and the long-term sustainability of projects. Partnerships help contribute to the sustainability of projects, and leveraging partnership funding can help sustain projects once federal funding has ended. The Project Spotlight text box above presents a few examples of the positive impacts strong partnerships can have on project success and long-term sustainability. That said, one external respondent noted that long-term funding was important, as the development of partnerships takes time and that such relationships are an integral part of supporting integration of interventions into existing systems, and are necessary for projects that work on multiple issues, such as addressing food security while also offering classes on healthy cooking.

While all projects established partnerships, project data pointed to some challenges. For example, staff turnover hindered continuity, and changing provincial priorities affected regional scale-up. These challenges were mitigated somewhat by working in collaboration with partners, such as local Indigenous organizations, and engaging local partners to help projects better understand the local political context.

4.4 Scale-Up and Sustainability

The Innovation Strategy fostered interventions that were both scalable and sustainable. This was accomplished through intentional design, such as focusing on the role of partnerships, as well the development of supporting tools, such as the Scale-Up Readiness Assessment.

At each phase of funding, projects were required to submit a new Application for Funding. A review of each application was conducted by a panel of experts with knowledge of all aspects of population health intervention research and health promotion interventions. At each phase, there were different questions included in the application that were relevant to that particular stage of funding, and projects were selected based on ranking and available funding.

Phase 3 of the Innovation Strategy focused on supporting the scale-up of promising interventions to increase their reach and benefit more people. It also promoted sustainable policy and program development so that, by the end of Phase 3, interventions to date were integrated within a system and were sustainable.

The program’s Scale-Up Readiness Tool contains the criteria that were used to assess whether a project was ready for scale-up: intervention readiness and evaluation, organizational capacity, system readiness, partnership development, community engagement, cost-effectiveness, and knowledge development and exchange (see Appendix 5 for additional details). At the end of Phase 2, the program used the Tool to carry out an assessment of each project proposal. The results of this assessment and subsequent Phase 3 funding are shown in Table 1 below.

The capacity to work at multiple sites across the country is an important consideration for sustainability. By the end of Phase 3, all of the mental health promotion projects had sites in more than three P/Ts. By 2017-18, just under a third (29%) of healthy weights projects had sites in more than three P/Ts, with interventions delivered in 197 communities.Footnote g

| Scale-up Readiness Assessment Levels | Number of Phase 2 Projects (20) | Number of Projects which received Phase 3 Funding (11) | Number of Projects which didn’t received Phase 3 Funding (9) | Number of Projects which didn’t received Phase 3 Funding but were sustainable or partly sustainable after Phase 2 (4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health |

Healthy Weights | Mental Health |

Healthy Weights | Mental Health |

Healthy Weights | Mental Health |

Healthy Weights | |

| High (4) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Ready (9) | 4 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Not Ready (7) | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Totals | 9 | 11 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

There is evidence that projects have been able to take measures to sustain their activities once Innovation Strategy funding had ended. Exit interviews conducted with funding recipients that did not receive Phase 3 funding (n=9) highlighted that four of these projects had secured funding external to PHAC and were able to continue to provide their services and programming. Just under half (43%) of the projects were integrated either fully or partially into existing systems, and all the projects have continued to disseminate information and products that were developed as part of the funding they had received from the Innovation Strategy.

Some projects did not apply for further funding because they had already achieved results that were sustainable. For example, the Towards Flourishing project and the Health Promoting Schools program did not apply for Phase 3 funding, in part because they had already secured ongoing provincial funding. The Towards Flourishing project had been sustained since 2015, when Manitoba announced funding to support its integration into an existing province-wide program.

5.0 Elements of an Innovative Program

The program has been innovative in its overall approach at both the program and project levels.

Internal, external, and funding recipient key informants noted that the Innovation Strategy was unique in its approach to funding interventions, doing something quite different from any other PHAC funding available at the time. The success of this model resulted in other programs within the Centre for Health Promotion adopting similar elements into their own programs.

Key informants highlighted a number of program features that set the Innovation Strategy apart from the others, including:

- The length of funding (up to nine years) is atypically long for federal programs. The benefits of long-term funding noted in internal documents were sustained growth, deeper impact, and an opportunity for interventions to become sustainable.

- The phased approach to project funding, where only promising projects are funded for subsequent phases, was viewed by key informants as innovative (see section 1.0 for further details). This phased, or gated, approach can drive change at each phase, while preventing stagnation and encouraging innovation and evidence generation.

- The Innovation Strategy required activities to be implemented in multiple sectors, jurisdictions, and settings, thus fostering an expanded reach.

- Emphasis on research and evaluation throughout the project helped assess the effectiveness of interventions and allowed for course correction, which in turn helped inform project design and enhanced learning.

- Focusing on establishing partnerships and encouraging collaboration with funding recipients helped the program build relationships and share knowledge more broadly.

- Building in scale-up and sustainability into the design of a project helped ensure that evidence was available for decision making, and that partners were engaged and could continue to fund the intervention, meaning that projects were more likely to succeed.

- Furthermore, a few key informants noted that creating changes at the system level, such as implementing a new curriculum on healthy relationships across a school board, or a mental health promotion strategy for an entire health region, leads to more sustainable results than focusing on short-term projects that aim to change the behaviours of individuals.

The Innovation Strategy model has inspired other programs, such as the Supporting the Health of Survivors of Family Violence Program and the Dementia Community Investment Fund, to adopt elements into their own program design, including the requirement for partnerships between researchers and communities.

6.0 Program Efficiency

The projects funded by the Innovation Strategy have leveraged financial and in-kind resources. In addition, the program has made internal adjustments, such as streamlining reporting to improve efficiency.

Innovation Strategy projects were required to leverage funds from other sources. Evidence indicates that there was significant leveraging at the project level, contributing to the overall efficiency of PHAC’s investment. In addition, a number of initiatives have been introduced to improve efficiency going forward.

Projects in both streams have leveraged additional resources, including financial contributions and in-kind support, such as donations, loaned staff, and volunteers:

- Mental health promotion: by the end of Phase 3 (2017-18), 100% of projects had leveraged both financial and in-kind resources. For every grant and contribution dollar invested by the program, projects leveraged $1.28 in additional resources. All four Phase 3 projects received financial support of approximately $3.7 million from other sources. Furthermore, all four Phase 3 projects received in-kind support worth $567,994. These projects also mobilized an estimated 61,576 loaned staff hours, and three of the four mobilized 4,668 volunteer hours.

- Healthy weights: in 2017-18, 100% of projects leveraged both financial and in-kind resources. For every grants and contributions dollar invested by the program, projects leveraged $1.57 in additional resources. Six of the seven projects received financial support of approximately $3 million from other sources. All seven projects received in-kind support for a total of $1 million, six of the seven mobilized an estimated 13,642 loaned staff hours, and six of the seven mobilized 21,067 volunteer hours.

For both healthy weights and mental health projects, additional support was leveraged from a variety of sources, including other federal departments and agencies, federal and municipal governments, and regional health authorities. There were also significant volunteer and loaned staff hours that contributed to both healthy weights and mental health projects.

The program itself has made improvements in efficiency. According to internal interviewees, a number of initiatives have contributed to improved efficiency of program delivery:

- Going forward, the Innovation Strategy will focus on one thematic area (mental health) to make better use of staff resources, increase the cohesiveness of innovations tested across funded projects and improve alignment with the Centre’s mental health focus.

- Program staff mentioned that performance measurement tools have been refined based on project feedback, thereby streamlining reporting. A few funding recipient key informants noted that reporting tools and requirements have improved over time and that reporting has become less onerous.

- The program has improved project assessment tools to better select projects and determine their potential for scale-up.

Some internal respondents reported inefficiency in some interactions between the program and the Centre for Grants and Contributions. Several funding recipients found that some federal financial rules associated with contribution agreements limited their ability to adapt to changing circumstances (e.g., the inability to carry over funds to next fiscal year). A few recipients also noted that turnover of managers in the program affected timeliness and continuity in their project management. The Agency is currently working to address these issues.

6.1 Program Spending

Over the five-years covered by the evaluation, the program spent almost 100% of its budget, despite individual variances in spending for each year.

Table 2 presents planned and actual program expenditures for the period between 2014-15 and 2018-19. During the evaluation period, the program lapsed approximately $2.6 million, largely attributable to fiscal year 2014-15, when there was a slight delay in the transition from Phase 2 to Phase 3 project funding. The program also lapsed approximately $800,000 in 2018-19, due to the timing between the end of Phase 3 projects and the start of a new cohort of projects under the Mental Health Promotion Innovation Fund. During this transition, projects were given a time extension but no additional funding, which was not accounted for in the planned spending, resulting in some underspending. Since then, the planned annual allocation for the program was reduced from $11.4 million to just over $6 million, mainly due to the internal reallocation of funds to a new investment to address family violence.

| Year | Planned Spending ($) | Expenditures ($) | Variance ($) | % planned budget spent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G&Cs | O&M | Salary | TOTAL | G&Cs | O&M | Salary | TOTAL | |||

| 2014-15 | $10,336,583 | $325,000 | $714,000 | $11,375,583 | $8,704,641 | $135,223 | $696,085 | $9,535,949 | $1,839,634 | 84% |

| 2015-16 | $6,247,000 | $162,500 | $617,773 | $7,027,273 | $6,136,721 | $210,664 | $624,796 | $6,972,181 | $55,093 | 99% |

| 2016-17 | $4,947,000 | $125,000 | $600,000 | $5,672,000 | $5,152,878 | $131,056 | $805,777 | $6,089,711 | -$417,711 | 107% |

| 2017-18 | $4,947,000 | $125,000 | $665,507 | $5,737,507 | $5,098,193 | $84,876 | $1,057,762 | $6,240,831 | -$503,324 | 109% |

| 2018-19 | $4,947,000 | $135,649 | $1,161,132 | $6,243,781 | $4,353,632 | $49,757 | $1,032,259 | $5,435,648 | $808,132 | 87% |

| * Financial data provided by the Office of the Chief Financial Officer. | ||||||||||

Economic assessments are the systematic evaluation of the costs and benefits of an initiative or program to determine its value and relative economic efficiency. These types of assessments were undertaken in 2016-17 to examine the cost-effectiveness of six Innovation Strategy projects: four from the healthy weights stream and two from the mental health stream. There are a number of limitations to the conduct of economic assessments for population health interventions and there was a variance in the quality of the assessments conducted, wherein five full economic assessments were completed, while one presented intervention costs only. However, the findings showed all projects “to be worthwhile investments that provide good value-for-money in preventing obesity and promoting mental health”. While not generalizable beyond the specific project contexts, these ratios ranged as follows: for every dollar spent in direct costs, a net benefit between $3 and $14 was seen for the two mental health promotion interventions, and for every dollar spent in direct costs, a net benefit between $2 and $6 was seen for the four healthy weights interventions.

6.2 Collection and Use of Performance Measurement Data

The Innovation Strategy has an effective performance measurement strategy in place and it uses the information it generates to support decision making. There are a few challenges in understanding the varied impacts on different population groups; however, the program actively searches for ways to improve its own performance measurement.

Performance data is collected regularly and a review of indicator reports generally found that indicators were reported on consistently and were well substantiated through robust program and project data. Some indicators were either reported on annually or during different phases of the project.

The Innovation Strategy undertook efforts to ensure that performance measurement strategies, including tools, were appropriate for capturing adequate performance data. Baselines and targets were captured through the performance measurement strategy, and rolled up in the Performance Information Profile. The program actively looked for ways to improve performance measurement, such as streamlining questions or measuring the use of knowledge products. The program has also streamlined its data collection, in response to feedback, to focus on only collecting information it will actually use, and reduce the reporting burden on project recipients to the greatest extent possible.

Key informants noted that it was sometimes challenging for projects to capture the reach of their interventions, due to factors such as privacy considerations, clients accessing multiple programs, language barriers, staff turnover, and transient populations. Mitigation measures used to manage these challenges included revising data collection techniques, translating resources, verbal client surveys, and the creation of tools targeting individuals with lower literacy rates.

PHAC staff also noted it was challenging to roll up diverse projects into an overall performance story for the program. Additionally, the program has had more success in getting projects to incorporate health inequity considerations at design stages, but is trying to improve how projects report on these same results. While projects were required to undertake an analysis of the differences between population groups, understanding the impacts and differences across the groups has been more challenging.

7.0 Conclusions and Recommendations

In examining PHAC’s activities over the last five years, it is clear that the program is making significant progress in supporting the development, adaptation, implementation, and evaluation of promising population health interventions.

Intervention research generates knowledge of effective public health approaches. Projects in both streams improved the factors that help protect the health of participants while reducing risk behaviours, and there is evidence that participants’ health behaviours improved as well. Furthermore, knowledge about successful interventions was shared and used by a range of stakeholders.

Partnerships were an integral component of the Innovation Strategy and important to the success of the projects in terms of delivery, implementation, scale-up, and sustainability. Data collected during the evaluation showed that at least half of the project partnerships have been sustained for three years or more.

Most key informants noted that the Innovation Strategy was unique in its approach to funding interventions, doing things quite differently from any other PHAC funding intervention at the time, such as the length of funding that helped create systems-level changes versus individual changes, a focus on evidence generation, evaluation and scaling up of promising interventions, a phased approach to funding, and building flexibility into the projects and programs, allowing for course corrections along the way. The success of this model resulted in other programs within the Centre for Health Promotion adopting similar elements into their own programs.

Further efficiencies were seen at the project and program levels. Current project performance data showed that the vast majority of projects in both streams leveraged additional resources (e.g., financial, in-kind). The next iteration of the Innovation Strategy, called the Mental Health Promotion Innovation Fund, will cover the sole thematic area of mental health, creating a stronger base for evidence-based policy development in mental health promotion, and alignment with the Centre’s broader mental health focus.

What we learned

The evaluation has identified one recommendation, as the program has already taken steps to mitigate most of the minor challenges that were identified. Along with the recommendation, key aspects that have the potential to enhance the management of public health intervention projects have also been highlighted below for other PHAC programs to consider.

Key Aspects

- Having strong, vested partners was key to the delivery, implementation, scaling up, and sustainability of projects in both streams. These partnerships led to a two-way exchange of knowledge that was valuable in terms of improving practices.

- Incorporating evaluation expertise into each funded project ensured that interventions were tested to better understand the impacts of their activities, adding to the evidence base on effective approaches. The program provided support to project recipients to enhance their understanding of what is meant by “scale-up”. Therefore, projects were able to take the necessary steps to expand their interventions and enhance sustainability.

- The phased approach of the Innovation Strategy built in flexibility from the outset to allow the program to identify and learn from what is working and what is not at the end of each phase. This then allowed the program to make necessary course corrections to ensure the overall success of the program.

- It takes time to design, implement, adjust, and evaluate population health interventions. The length of funding (up to nine years) was seen as especially essential for this type of program, since projects are trying to create long-lasting system-level changes that can only be achieved through years of committed investment.

Recommendation

Recommendation 1: Considering the success of PHAC's activities to date, promote the Innovation Strategy, including the development, adaptation, implementation, and results of promising population health interventions.

The program has had a significant impact on the development, adaptation, implementation, and evaluation of promising population health interventions. The program has included a Knowledge Hub in the new Mental Health Promotion Innovation Fund. The Hub supports knowledge translation and the promotion of health intervention findings between projects and external partners and stakeholders, and supports intervention research for each project’s outcomes. The Innovation Strategy should also consider communicating the positive impacts it has achieved, by sharing the results and elements of public health intervention management more broadly, both within PHAC and the broader Health Portfolio, as well as with provinces, territories, and other partners and stakeholders. This would also include a focus on the program’s unique approaches to funding interventions, such as the length of funding that helped create systems-level changes versus individual changes, the focus on evidence generation, evaluation and scaling up of promising interventions, a phased approach to funding, and building flexibility into the projects and programs, allowing for course corrections along the way.

Appendix 1 – Evaluation Scope and Approach

The evaluation was scheduled in the Departmental Evaluation Plan for the Public Health Agency of Canada and Health Canada, 2018-19 to 2022-23, and in accordance with the requirements outlined in the Financial Administration Act.

The evaluation covered Innovation Strategy activities from April 1, 2014 to March 31, 2019 from Phases 2 and 3 of the two priority streams: Equipping Canadians – Mental Health throughout Life (mental health promotion) and Achieving Healthier Weights (healthy weights). It did not assess the Phase 1 activities of the Strategy, as the previous evaluation covered them. The questions examined by the evaluation are shown in the table below.

| Core Issues | Evaluation Questions |

|---|---|

| Relevance | |

| Issue #1: Need, priorities and role |

|

| Performance (effectiveness, economy and efficiency) | |

| Issue #2: Effectiveness/Impact |

|

| Issue #3: Demonstration of Economy and Efficiency |

|

Data for the evaluation was collected using various methods, such as a literature review, a document and file review, key informant interviews, and a financial data review. More specific details on data collection and analysis methods are described in Appendix 2. Data was analyzed by triangulating information gathered from the different methods listed above, with the intention of increasing the reliability and credibility of evaluation findings and conclusions.

Over the course of the evaluation, Innovation Strategy-funded projects for mental health covered the end of Phase 2 and all of Phase 3. Phase 2 includes fiscal year 2014-15 and Phase 3 includes fiscal years 2015-16 to 2017-18. Funded healthy weights projects covered about half of Phase 2 and Phase 3. Phase 2 includes fiscal years 2014-15 to 2016-17, and Phase 3 includes fiscal years 2017-18 to 2018-19.

Appendix 2 – Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Evaluators collected and analyzed data from multiple sources. Data collection started in February 2019 and ended in June 2019. Data was analyzed by triangulating information gathered from the different methods listed below. The use of multiple lines of evidence and triangulation were intended to increase the reliability and credibility of the evaluation findings and conclusions.

Literature review: