Modernizing preventive health care guideline development in Canada: A way forward

Download in PDF format

(13.31 MB, 104 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: 2025-06-13

Foreword by the Chair

Preventive health care is a cornerstone of a strong and equitable health care system — one that not only treats illness, but actively works to prevent it. Throughout my career in public health, research, and evidence-based policymaking, I have seen firsthand how preventive measures can improve health outcomes, reduce disparities, and strengthen health care systems. Enhancing our preventive health care framework is one of the most impactful ways we can enhance the well-being of all Canadians.

The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC) has long been a trusted voice in evidence-based guideline development and is internationally recognized for its work. As the health care landscape continues to evolve, so too must the structures and processes that guide it. The External Expert Review Panel, composed of thirteen experts from diverse fields, approached this work with a shared commitment to ensuring that the Task Force remains a leader in preventive health care — responsive to the needs of primary health care professionals and the public, as well as the provincial and territorial screening program managers, quality councils, and other key interest holders who support professionals and the public in the delivery of primary care and clinical preventive services.

Throughout this process, we listened to family physicians, medical specialists, other health care professionals and members of the public. In addition, we gathered perspectives from academic institutions, health professional associations, non-governmental organizations, provincial and territorial health authorities, and others. Their insights painted a clear picture: while the Task Force is widely respected for its scientific rigour, there is a pressing need to modernize its approach to be more inclusive, transparent, and responsive to the diverse realities of health care delivery across Canada. In particular, many emphasized the importance of ensuring that guidance is contextualizable — adaptable to different provincial and territorial systems, provider roles, and population needs — so that evidence-based recommendations can be meaningfully implemented where they matter most. In order to achieve everything that is expected of it, it needs to be adequately resourced and supported. Preventive health care is not static, and neither should be the structures that support it.

This report presents findings and recommendations that will not only bolster the Task Force's credibility but also enhance its ability to serve the evolving needs of primary care professionals and people living across Canada. By broadening the evidence base, embedding contextual flexibility into its methods, adopting more systematic, equity-centred engagement, and by strengthening governance, we can ensure that preventive health care guidelines remain both scientifically rigorous and practically relevant.

The recommendations in this report are not only about modernizing the approach but about ensuring that preventive health care remains responsive to evolving scientific evidence, inclusive of diverse perspectives, adaptable to real-world delivery settings and to local public health priorities.

At a time when misinformation and disinformation challenge public trust in health care, the role of independent, evidence-based bodies such as the Task Force has never been more vital. As this report was being prepared, the work of the Task Force was temporarily paused. It is essential that it be enabled and supported continuing its critical contributions to preventive health care in Canada.

I want to thank my fellow Panel members for bringing their knowledge, expertise and diversity of views to our meetings where openness and respect were not only evident but also felt. Their collaboration and dedication have been essential to fulfilling our mandate. I am also grateful to the many national and international experts and interest holders who contributed their time and expertise to this review, as well as the organizations that provided valuable insights and perspectives. They all helped to shape the recommendations outlined in this report.

This report is not the end of the conversation — it is the beginning of an important transformation. In the final section of this report, we make broader observations about the need for reform of the pan-Canadian approach to guideline development. I urge policymakers, health care leaders, and the public to embrace these ideas and work together in a coordinated approach to build a stronger, context-sensitive, and responsive approach to preventive health services and guideline development in Canada.

Vivek Goel, C.M., O.Ont.

Chair, External Expert Review Panel

March 2025

On this page

- Chapter 1: Introduction and context

- Chapter 2: Key findings

- 2.1 Redefining the mandate and strategic focus

- 2.2 Advancing evidence, methods, and guideline relevance

- 2.3 Embedding equity: Towards inclusive guideline development

- 2.4 Strengthening governance for inclusive and contextualizable guidance

- 2.5 Securing the foundations for sustainability and independence

- Chapter 3: Broader considerations

- Conclusion: A way forward

- Glossary

- Appendices

- Appendix 1: External expert review-terms of reference

- Appendix 2: External expert review members

- Appendix 3: Technical advisors

- Appendix 4: Persons who submitted a written presentation

- Appendix 5: Persons, interest holder organizations, government entities and academic institutions who provided input

- Appendix 6: Summary of interest holder submissions

- Appendix 7: Comparison with international guideline development organizations

- Appendix 8: Proposed organizational chart for the task force

- Figures

- References

- Footnotes

Acknowledgments

We extend our deepest gratitude to all those who contributed to this review and played a crucial role in shaping this report. First and foremost, we acknowledge the invaluable guidance and expertise provided by the dedicated secretariat within the Public Health Agency of Canada. Under the distinguished leadership of Dr. Howard Njoo, Deputy Chief Public Health Officer, and Director General Marie-Hélène Lévesque, the team provided steadfast support throughout the review process. In particular, we express our sincere appreciation to Mariellen Chisholm, Kim Davis, Sylvie Desjardins, Ashley Gilbert, Vivianne Z. Lamoureux, and Marisha Tardif for their unwavering commitment and exceptional efforts.

We are also profoundly grateful for the counsel and contributions of our technical advisors, whose diverse expertise in public health, policy, research, and public engagement helped refine our analysis and enhanced the rigour of our findings. Their insightful feedback, rigorous review, and meaningful engagement in key discussions significantly strengthened the coherence and credibility of this report.

Furthermore, we extend our appreciation to the key presenters who generously shared their knowledge and perspectives on national and international best practices on topics surrounding guideline development. Their insights provided valuable context, deepened our understanding of emerging challenges, and helped shape our recommendations.

We were equally fortunate to engage with a diverse range of individuals and interest holder groups from across the country, whose thoughtful input greatly contributed to our work.

While these contributions have been instrumental in shaping this report, we assume full responsibility for its content, including any remaining limitations or errors. The interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations presented herein reflect our independent assessment and judgment.

List of acronyms

- AI

- Artificial Intelligence

- CIHR

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- COI

- Conflict of Interest

- CTFPHC

- Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (Task Force)

- EAB

- External Advisory Body

- EER

- External Expert Review

- ERSC

- Evidence Review and Synthesis Centre

- GRADE

- Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- HHS

- Health and Human Services (federal department in the United States)

- KT

- Knowledge Translation

- NACI

- National Advisory Committee on Immunization

- NHMRC

- National Health and Medical Research Council

- NICE

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- PT

- Provinces and Territories

- RCT

- Randomized Controlled Trial

- SME

- Subject Matter Expert

- SPOR

- Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research

- TF-PAN

- Task Force Public Advisors Network

- UK

- United Kingdom

- USPSTF

- United States Preventive Services Task Force

- US

- United States

- WG

- Working Group

Executive summary

In May 2024, the Minister of Health directed the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) to initiate an external review of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC — hereafter referred to as the Task Force). The review assessed the Task Force's governance, mandate, and processes.

Composed of a Panel of thirteen independent experts, the External Expert Review (EER — hereafter referred to as the Panel) was asked to provide actionable recommendations to enhance the Task Force's capacity to support Canada's health care system, using primary health care as the vehicle to improving population health outcomes.

The Panel conducted focused assessments, engaged with a wide range of interest holders, and reviewed international comparators and expert analyses to identify strategic opportunities for modernizing the Task Force. As Canada's preventive health landscape continues to evolve, the Task Force must adapt to better serve the needs of patients, families, and caregivers — as well as those of diverse primary care health professionals, and the provincial programs and quality councils that support them.

This evolution is critical to ensuring that Task Force guidance remains rigorous, inclusive, contextualizable, and responsive to real-world practice.

The vision guiding this review is to ensure that everyone in Canada regardless of geography, background, socioeconomic status, or identity — including those from equity-denied groups such as Indigenous and Black communities — has access to high-quality, equity-centred, context-sensitive, evidence-based, and coordinated guidance on preventive health services.

The Task Force plays a central role in delivering scientifically sound recommendations to support preventive health care in clinical settings across the country. To better align the Task Force with current system realities and ensure long-term effectiveness, this report presents twelve recommendations that provide a clear and coherent roadmap for modernization, strengthened governance, and stable operational support. It also includes three supplementary recommendations aimed at addressing broader system-wide challenges and advancing national coordination in preventive health guideline development.

A. Reframe the mandate to reflect today's health system

- Modernize the mandate and rename the Task Force (Recommendation 1): PHAC should establish a clear and updated mandate for the Task Force that reflects its evolving role in supporting the delivery of preventive health services. This mandate should focus on the development of guidance that is inclusive, up-to-date, equity-centred and contextualizable for frontline health professionals. As part of this realignment, PHAC should consider renaming the group as the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Services to better reflect its focus on the full spectrum of preventive interventions delivered in primary care settings.

- Clarify the Task Force's role in a crowded landscape (Recommendation 2): PHAC should establish a recurring, structured process to determine when the Task Force should lead the development of new preventive health guidelines, and when it would be more efficient to adopt or adapt existing high-quality recommendations from other sources. This process should be guided by a transparent prioritization framework and inform an annual workplan that sets the Task Force's strategic direction over a three-year horizon. By clarifying the Task Force's role within Canada's broader guideline ecosystem, this approach will reduce duplication, improve coordination, and address fragmentation across the system.

B. Strengthen methods and evidence use for relevance and rigour

- Evolve the Task Force methodological framework (Recommendation 3): PHAC should enable and support the Task Force to streamline its methodological framework, building on the evolving GRADE approach — particularly Core GRADE — to ensure rigorous and inclusive guideline development. This should be supplemented with additional evidence-to-decision frameworks suited to supporting recommendations for equity-denied populations and in areas where evidence is limited or emerging. PHAC should also support the refinement of methods and communication strategies for population-based interventions that are clinically applied in primary care (e.g., screening), ensuring clarity and relevance for diverse audiences.

- Implement a phased living guidelines model (Recommendation 4): PHAC should enable and support the Task Force to implement a phased approach to maintaining and updating high priority guidelines using living methods. This includes continuous evidence monitoring, the use of emerging technologies, and collaboration with international partners. PHAC should seize opportunities to share in evidence infrastructure to enable greater efficiency and lower redundancy. This approach will also allow provinces and territories to rely on shared evidence and focus their efforts on contextualizing guidance for their own service delivery models.

- Strengthen practice adoption through partnership and adaptation (Recommendation 5): PHAC should enable and support the Task Force in collaborating with provincial and territorial partners to support the system-level conditions necessary for the effective implementation of preventive health service guidelines. This includes structured engagement with prevention intervention delivery programs, quality councils, and other implementation and evaluation partners to co-develop practical tools and identify barriers and enablers across diverse care settings. Each guideline cycle should integrate knowledge translation resources — such as provider decision aids, implementation toolkits, and user-specific summaries — tailored to the needs of primary care teams and the systems that support them. PHAC should also support the development of mechanisms to assess feasibility, uptake, and impacts in coordination with jurisdictions.

C. Embed equity and public voice in guideline development

- Prioritize equity in topic selection (Recommendation 6): PHAC should support the Task Force in applying transparent, equity-focused criteria to topic selection, with a focus on equity-denied populations — including Black and Indigenous communities — and the priorities of provinces and territories. A topic sequencing approach should guide progress toward full preventive service coverage, while also addressing current uneven coverage of guideline topics — such as duplication in some areas (e.g., cancer) and lack of guidance in others (e.g., mental health). Topic framing should emphasize opportunities to improve outcomes across the health system, especially in areas that support health equity and align with the quadruple aim.Footnote 1

- Establish a model for equity-centred patient and public engagement (Recommendation 7): PHAC should enable and support the Task Force to adopt structured, consistent mechanisms for engaging patients, community groups — including Black, Indigenous and other communities historically underrepresented in health policy and clinical decision-making —, and the public throughout guideline development, ensuring that lived experience, patient preferences and community values are meaningfully reflected in final recommendations.

D. Enhance governance, membership, and expert input

- Build a competency-based and inclusive membership and nomination framework (Recommendation 8): PHAC should enable and support the Task Force to adopt an integrated framework for inclusive, competency-based membership and a transparent nomination process. This framework should define essential qualifications, expertise, and lived experience — ensuring representation from equity-denied communities and across primary care, public health, and Indigenous health systems. It should also establish a public nomination process, including clear eligibility criteria, targeted outreach, and an independent nominations committee with diverse representation. These measures will ensure the Task Force is equipped to develop guidance that is relevant, equitable, and contextualizable across Canada's diverse health systems.

- Formalize Subject Matter Expert (SME) engagement (Recommendation 9): PHAC should enable and support the Task Force to create structured roles for SMEs to contribute at key stages of guideline development working groups, without compromising the Task Force's independence in decision-making. This will support the integration of expertise from primary care practitioners alongside domain-specific expertise from specialists.

- Adopt a tiered Conflict of Interest (COI) Framework (Recommendation 10): PHAC should enable and support the Task Force to adopt a two-tier approach — distinguishing voting members on the Task Force from those participating in topic-specific working groups — to managing conflict of interest, enabling transparent and risk-proportionate participation of subject matter experts (SMEs).

E. Secure stable funding and operational infrastructure

- Establish long-term funding and secretariat support (Recommendation 11): To fulfill its mandate effectively, the Task Force requires stable, multi-year funding, including appropriate compensation for its members, when required. PHAC should support a dedicated or shared Secretariat to provide continuity, infrastructure, as well as methodological and operational support.

F. Transition to an accountable, independent governance model

- Reconstitute the Task Force as an External Advisory Body (Recommendation 12): PHAC should constitute the Task Force as an independent External Advisory Body, supported by transparent governance, formalized engagement with interest holders, and accountable decision-making processes.

Looking beyond the Task Force: System-wide coordination opportunities

Beyond the Task Force, the Panel identified broader systemic gaps that hinder Canada's ability to deliver guidelines for health professionals in a coordinated manner and equity-centred preventive health care at the clinical, community and population levels. These include the absence of a national body to assess evidence and provide recommendations on community-level interventions, limited coordination between research funders, data agencies, quality councils, and guideline development and implementation, and the lack of shared frameworks for engaging interest holders.

There is also an urgent need to ensure that guidelines are not only rigorous but also adaptable to the specific health system structures, population needs, and delivery contexts of each province and territory.

While beyond the formal mandate of the review, these challenges merit serious consideration. The Panel encourages federal leadership and collaboration with provinces and territories to explore structural solutions — such as a national coordination hub for evidence-based health guidelines, a dedicated Task Force on Community Preventive Services, and a network to enhance coordination with relevant agencies — to strengthen alignment and build a more inclusive, future-ready guideline and development preventive health system.

To this end, the Panel sets out three supplementary recommendations:

Supplementary recommendation A: Create a national coordination hub

The federal government, in collaboration with provincial and territorial partners, should explore the creation of a national coordination hub for guideline development — bringing together funders, health providers, researchers, and implementers to strengthen alignment, reduce duplication, and accelerate the translation of evidence into effective policy and practice. This hub should enable formal coordination across advisory and decision-making structures, including learning and improvement platforms, and support system-level integration. It should also help contextualize by enabling the adaptation of guidance to different provincial and territorial settings, supported by a shared infrastructure for producing localized summaries of key recommendations. This includes aligning funding mechanisms and operational enablers to embed a modernized, population-responsive approach to clinical practice guidelines development and implementation.

Supplementary recommendation B:

Launch a Task Force on Community Preventive Services: The federal government, in collaboration with provincial and territorial partners, is encouraged to explore the creation of a Task Force on Community Preventive Services, in collaboration with organizations such as the National Collaborating Centres for Public Health (NCCs), to provide independent, evidence-based guidance for public health and community-level interventions beyond clinical care.

Supplementary recommendation C:

Build a network for research, data, and evaluation alignment: The federal government is encouraged to establish a network to strengthen coordination with Canada's health research funders, data agencies, and quality councils. This network should also position Canada to engage with, and contribute to, an emerging global infrastructure for living evidence synthesis — enabling provinces and territories to access shared, high-quality evidence bases and focus their efforts on local adaptation, rather than duplicative evidence review and guidance development.

By acting on these insights, we can contribute to a more cohesive, coordinated, and forward-looking approach to preventive health — one that ensures all people in Canada have equitable access to up-to-date evidence-based guidance that promotes health and well-being across communities and generations.

Chapter 1: Introduction and context

1.1 External Expert Review Panel mandate

In May 2024, Canada's Minister of Health directed the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) to launch an independent review of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC — henceforth referred to as the Task Force). This review was tasked with examining the Task Force's governance, mandate, and processes, as well as providing actionable recommendations on modernizing its role and structure.

The goal was to ensure that its guidelines remain evidence-based, up-to-date, and relevant to primary care health professionals. This effort aims to align preventive health guidelines with the evolving needs of Canada's health care systems and to support equitable population health outcomes.

While concerns surrounding the Task Force's 2024 release of its draft breast cancer screening recommendations served as a catalyst for the review, the Panel was not tasked with reviewing or evaluating the specific events or decisions that led to their development.

1.2 Approach

PHAC appointed members to the External Expert Review (EER) in September 2024, establishing an independent Panel of thirteen experts to review the Task Force structure, governance, and scientific methods. The full terms of reference for the review are available in Appendix 1, while the biographies of Panel members can be reviewed in Appendix 2. Additionally, four Technical Advisors provided specialized insights into key areas such as medical research, public health, public engagement, and health equity. These experts played a critical role in ensuring that the review addressed both systemic challenges and patient-centred concerns. The biographies of Technical Advisors are included in Appendix 3.

The Review Panel began its work in October 2024, using a structured approach that considered previous assessments and evaluations of the Task Force, national and international best practices in guideline development and input from consultations. It concluded its mandate with the publication of this report.

The Panel consulted with national and international experts — including health care professionals, researchers, and patient representatives — to ensure the inclusion of a diverse range of perspectives. A full list of those consulted is available in Appendix 4.

The Panel also engaged directly with the current and former Task Force leadership and gathered public input through direct engagement and an open consultation process. This included written submissions and a series of roundtable discussions with individuals, health professional associations, non-governmental organizations and academic institutions. It also included engagement with guideline developers in Canada. A complete list of participants is presented in Appendix 5, and a summary of perspectives from the consultation is presented in the "What We Heard" report in Appendix 6.

To benchmark Canada's approach against international models and to identify best practices that could inform improvements to Canada's system, the Panel examined governance structures, interest holder engagement practices, and guideline development processes in the United Kingdom (UK), Australia, and the United States (US). An international comparative analysis is provided in Appendix 7.

To further contextualize its findings, the Panel conducted an extensive review of key documents on the Task Force's evolution, successes, and areas for improvement. The insights gathered through this process informed the Panel's recommendations to strengthen Canada's preventive health guideline development system.

Finally, the Panel has been intentional in its choice of wording throughout this report, recognizing that terminology plays a key role in shaping the vision for a modernized Task Force. Key terms — such as "equity-centred" — have been chosen to reflect a commitment to clarity, relevance, and precision. A detailed glossary is included at the end of the report to support consistent understanding.

1.3 Guiding principles for recommendations

To ensure that the review process was independent and transparent, the Panel adhered to three core principles intended to uphold public trust and strengthen the integrity of the review:

Independence: The review was carried out free of external influence, political pressure, or conflicts of interest, ensuring that findings and recommendations were based solely on evidence. The Panel appreciates the support provided by the Secretariat staff assigned by PHAC; an arm's length relationship was maintained throughout this process. The Panel held in-camera discussions as needed to support independent deliberations. The Panel assumes full responsibility for the content of this report.

Transparency and accountability: Openness and accountability were prioritized at every stage of the review. The Panel regularly discussed its mandate, methodology, and approach to consensus decision-making. To support transparency, summaries of each meeting were published, providing the public with information on the topics that were reviewed and discussed.

Inclusivity and equity: To build public confidence in the guideline development process, the Panel actively engaged a diverse range of interest holders, including health care professionals, researchers, patient representatives and the public, as well as methodologists. This approach ensured that multiple perspectives were considered throughout the review, strengthening the credibility and fairness of the process.

By upholding these principles, the Panel aimed to reinforce trust in the review process and to contribute meaningfully to the development of a more inclusive, responsive, and transparent preventive health care guideline system in Canada.

1.4 Report structure

This report is structured as follows to provide a comprehensive review of the Task Force, outlining key findings, recommendations, and a broader vision for the future.

Chapter 2 presents the key findings of the review. It examines the Task Force's scope, mandate, governance, and structure, while identifying strengths and areas for improvement. The Chapter also considers how the Task Force operates within the context of Canada's broader health system and identifies opportunities to enhance its impact and alignment with this evolving landscape.

Chapter 3 outlines broader considerations for the future. Building on insights gleaned during the Panel's consultation and deliberations, it proposes courses of action to modernize the wider ecosystem of guideline development in Canada. The chapter highlights concrete opportunities to expand the scope of guidelines to better address community and population health needs.

The Conclusion summarizes key insights and highlights the importance of adopting a more inclusive, transparent, and responsive approach to preventive health guideline development in Canada.

Chapter 2: Key findings

This chapter presents the key findings of the review for clinical preventive guideline development, highlighting both the strengths of the current approach, as well as areas for improvement. It synthesizes insights from interest holder consultations, expert analysis, and international comparisons, identifying opportunities for enhancing governance, inclusivity, transparency, and responsiveness. These findings underscore the need for modernization and serve as the groundwork for the Panel's recommendations.

2.1 Redefining the mandate and strategic focus

Since its establishment in 1976 as the Canadian Task Force on Periodic Health Examination, the Task Force has played a pivotal role in shaping Canada's approach to preventive health. Initially focused on routine check-ups, it evolved to support evidence-based targeted, preventive health services in primary care settings. It has earned international recognition for its contributions and has served as a model for similar bodies in other jurisdictions.

Throughout the 1980s, the Task Force pioneered guidelines on preventive screening for healthy individuals, emphasizing the importance of population-based approaches. This work helped to lay the foundation for what are now well-established screening programs for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer across provinces and territories.

Although it was disbanded in 2005 following a decision by the Conference of Deputy Ministers of Health, the Task Force was re-established in 2009 with support from the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Since that time, it has developed clinical practice guidelines for primary care practitioners, with a particular focus on family physicians.

The Task Force has long been a trusted source of evidence-based recommendations. It has fulfilled its mandate with a strong emphasis on evidence-based medicine. However, as the structure of primary care services delivery and the organization of preventive services have evolved, so too must the Task Force's mandate to ensure it remains, inclusive, transparent, and responsive to the full spectrum of primary care providers, provincial and territorial implementation mechanisms, and the diverse needs of populations.

Adapting to a changing primary care landscape

Canada's primary care landscape is evolving from a physician-centric model to more interdisciplinary team-based care, with nurse practitioners, pharmacists, and other primary care health professionals now playing an increasingly significant role in delivering preventive health services. Simultaneously, the landscape is shifting from a model where physicians and teams independently manage all preventive health services to one in which they, alongside their patients, increasingly rely on provincial programs and quality councils for support. Despite this shift, the Task Force's recommendations are still largely perceived as physician-oriented, limiting their accessibility and applicability across the broader primary care workforce and its support structures.

Beyond primary care, Task Force recommendations often influence population and public health programs, including provincial screening initiatives. While these guidelines are developed with clinical practice in mind, their impact extends far beyond individual primary care providers, shaping broader public health policies and service delivery at the population level. This underscores the importance of ensuring that guidelines are not only relevant to primary care health professionals, but also effectively align with public health programs and quality councils to maximize their reach and effectiveness.

The delivery of preventive health services continues to evolve, with provinces and territories expanding their cancer screening programs over the years and developing tailored guidelines to support them. To ensure coherence, guideline development needs to be coordinated with provincial and territorial programs and quality councils.

To enhance its impact, the modernized Task Force must explicitly integrate the perspectives of a broader range of primary care providers and ensure its guidelines are inclusive, relevant, contextualizable, and responsive to the operational realities of diverse health care settings — particularly those built around team-based care. Reframing its recommendations as "guidelines on preventive health services for primary care health professionals and teams" will reinforce their practical application across different clinical settings and team structures. While family physicians continue to play a central role in preventive health services, other leading interest holders such as public health, other primary care health professionals, and provincial and territorial screening program managers and quality councils, among others, would benefit from the knowledge translation tools and resources necessary to seamlessly implement evidence-based guidelines in policy and practice. Embedding contextual adaptability into the guideline development cycle will also help ensure that recommendations remain relevant and adaptable to different models of team-based care and evolving delivery contexts.

Furthermore, many people in Canada lack regular access to primary care, including to physicians and other health professionals. Guidelines must be flexible and adaptable to account for different patterns of access across jurisdictions — ensuring they remain meaningful even in non-traditional care settings. The implementation of preventive health services guidelines must consider how these populations may access preventive care through alternate health services, such as walk-in clinics or emergency departments, while also acknowledging that some individuals do not consistently engage with any health care services.

The Panel heard concerns that physicians with expertise in diagnosing and managing specific diseases were not consistently included in the Task Force's work. Some interest holders expressed that guidelines on specific diseases should be developed and led by specialists in that field. We recognize that greater engagement with subject matter experts (SMEs) is necessary to incorporate their scientific and clinical expertise. However, the expertise required for developing guidelines for preventive health services targeted at healthy individuals at the population level goes beyond subject matter expertise. Primary care and public health practitioners are uniquely trained to work with healthy individuals, communities and populations, and their expertise and leadership remains essential to the development of preventive service guidelines.

Similarly, the lived experience of patients with specific diseases is invaluable in the development of disease-specific guidelines and knowledge translation tools, particularly concerning treatment. The development of preventive health services guidelines for healthy individuals should also incorporate the perspectives of those without the disease, as well as individuals who may have experienced unexpected negative outcomes related to recommended preventive health services — such as false positives, overdiagnosis, overtreatment, and psychological distress.

Since the Task Force operates independently of provincial and territorial health care systems, its role is to inform — not implement — PT policy decisions. However, the absence of a structured liaison mechanism limits alignment across national, provincial and territorial levels. Establishing such a mechanism is essential to strengthen coordination and ensure greater policy coherence and practice-level impacts.

Navigating a fragmented preventive care landscape

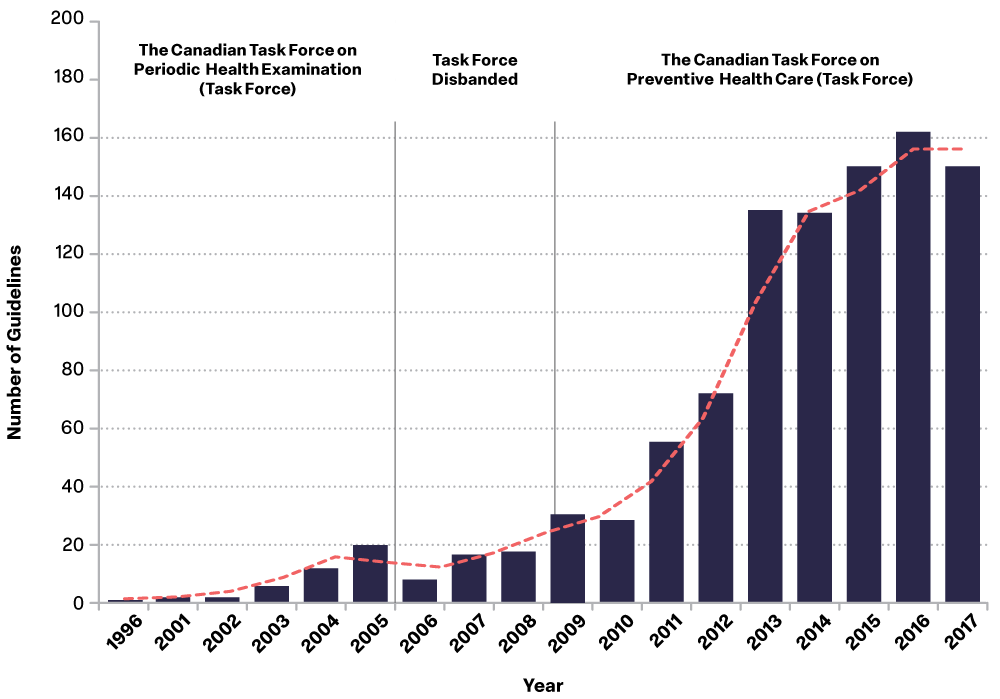

The landscape of guideline development in Canada is becoming increasingly complex and fragmented. Provincial and territorial health agencies, professional associations, specialist societies and the private sector each independently issue their own recommendations for preventive care and public health practice. Figure 1 shows the rapid growth in all guidelines being produced on an annual basis across organizations, with this likely being an underestimate of the total (SPOR Evidence Alliance, 2025).

Figure 1: Text description

Figure 1 shows the total number of national preventive health guidelines published in Canada each year from 1996 to 2017. It reflects contributions from various organizations, including the Task Force, and is divided into three phases based on changes in the Task Force's structure and activity over time.

Phase 1 (1996-2005):

During this period, the Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination was active and contributed to the development of national guidelines. Overall guideline production was relatively modest but gradually increased. In 1996, only 1 national guideline was published. This number rose to 12 by 2004 and reached 20 in 2005.

| Guidelines published in Canada | 1996 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 12 |

Phase 2 (2005-2008):

The Task Force was disbanded during these years. Despite this, some national guidelines continued to be developed by other organizations, though at a slower pace. Between 2005 and 2008, the total number of guidelines published each year ranged from 8 to 18.

| Guidelines published in Canada | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 20 | 8 | 17 | 18 |

Phase 3 (2009-2017):

In 2009, the Task Force was re-established and became a significant contributor to national guideline development. During this period, the number of guidelines published nationally rose sharply. From 31 guidelines in 2009, the total grew to a peak of 164 in 2016. In 2017, 152 guidelines were published, still far above the levels seen in earlier years.

| Guidelines published in Canada | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 31 | 29 | 56 | 73 | 137 | 136 | 152 | 164 | 152 |

This can lead to overlapping, inconsistently produced, and sometimes conflicting guidance, creating uncertainty for primary care providers, patients and the public. Additionally, guideline development can also inadvertently focus on specific health topics, driven by factors such as changing research priorities, advocacy, or available funding.

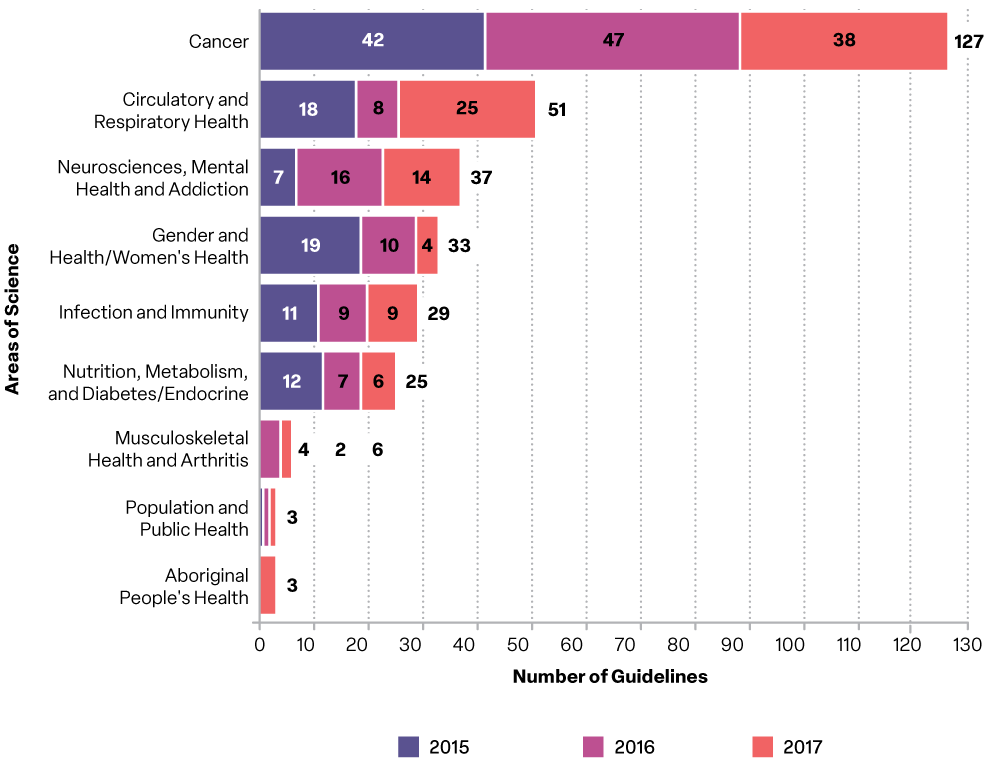

As highlighted in Figure 2, considerable effort is already directed toward cancer guidelines. As a result, gaps may emerge in key areas such as mental health screening and chronic disease prevention.

To address this problem of uneven coverage and fragmentation, an appropriate working group within a Federal-Provincial-Territorial mechanism should be developed to support pan-Canadian collaboration in preventive health service guideline development. This group should help clarify and coordinate the Task Force's role in leading, adopting, or adapting guidelines that fall within its mandate.

Establishing a structured mechanism for sharing and aligning recommendations with other guideline developers — including provincial and territorial programs — would help create a more consistent approach to preventive care, promoting alignment and reducing duplication. This engagement could also lay the groundwork for future efforts to draw on the emerging global infrastructure for living evidence syntheses and to adapt or adopt high-quality guidelines developed in other countries and globally.

The Task Force should focus its efforts on addressing gaps in preventive health services rather than developing recommendations when strong, evidence-based guidelines already exist at the provincial, territorial, or national level. A clear process for determining when the Task Force should lead, adopt, or adapt guidance will reduce duplication, support alignment, and maximize its contributions across the system.

In areas where well-established evidence-based processes within other services exist — such as in provincial cancer screening programs — the Task Force should reassess its involvement to focus on areas where its contributions add the most value, enhancing consistency and maximizing its impact. Ultimately, the goal should be to ensure that guidance is available for all preventive interventions across the life course.

Figure 2: Text description

Figure 2 displays the number of national preventive health guidelines published in Canada by scientific area for 2015, 2016, and 2017, with a total count for each area over the three-year period.

- Cancer had the highest number overall, with 127 guidelines published: 42 in 2015, 47 in 2016, and 38 in 2017.

- Circulatory and Respiratory Health followed with 51 guidelines, showing steady attention to this area.

- Neurosciences, Mental Health and Addiction had 37 guidelines, mostly in 2015 and 2016.

- Gender and Women's Health saw 33 guidelines, with a notable peak in 2015 (19 guidelines).

- Infection and Immunity had 29 guidelines, fairly evenly spread across the three years.

- Nutrition, Metabolism, and Diabetes/Endocrine had 25 guidelines, with a clear increase in 2017.

- Musculoskeletal Health and Arthritis accounted for 6 guidelines, mostly in the first two years.

- Population and Public Health had 3 guidelines, with one published each year.

- Aboriginal People's Health also had 3 guidelines, all published in 2016 and 2017.

This breakdown shows that while a range of topics are covered, the focus remains concentrated on cancer and chronic diseases, with notable gaps in other preventive areas.

Over the course of the Panel's consultation process, a number of interest holders highlighted the need for greater attention to upstream determinants of health and to guidance on primordial prevention.Footnote 2 The Panel believes that a modernized Task Force should maintain a focused mandate on preventive health services for primary care health professionals to ensure its recommendations are clear, targeted, and directly relevant to primary care practice.

As discussed in Chapter 3, the Panel suggests that PHAC explore options — such as increased coordination with the National Collaborating Centres for Public Health or a separate community-focused Task Force — to address the important gaps identified for guidance on primordial prevention.

Making guidelines work: The need for contextualizable preventive health guidance

Given these challenges and opportunities, the Panel believes that a modernized Task Force must adopt an approach to guidance that is not only evidence-based but also operationally relevant across Canada's diverse health systems.

To be effective across Canada's diverse health systems, preventive health guidelines must be designed as contextualizable — meaning they can be adapted to local realities, while preserving scientific integrity. This includes aligning with the organizational structures, resources, populations, and policy environments that vary across provinces and territories. Without this adaptability, even rigorously developed guidelines may remain underutilized, misunderstood, or poorly integrated into local practice.

Currently, Task Force recommendations are typically issued as universal guidance with limited support for local adaptation. This places the burden of contextualization on provinces, territories, and local health professionals, many of whom must reinterpret or redevelop guidance to ensure relevance within their systems. This leads to duplicated efforts, resource inefficiencies, and slower uptake, and can also increase the risk of misalignment with existing provincial and territorial programs or health priorities.

Embedding contextual adaptability into the Task Force's approach can resolve many of these issues. It allows for provincial and territorial health systems to tailor implementation based on their existing infrastructure, patient needs, and workforce capacity. It also supports primary care professionals — whether in large urban centres or rural areas — in applying guidelines in a way that fits their specific operational and community contexts.

Crucially, contextualizable guidance can help close equity gaps. It enables targeted adaptation to meet the needs of underserved or equity-denied populations, whose access to preventive care may be shaped by social determinants of health, geographic barriers, or systemic inequities. By encouraging alignment with local priorities and realities, contextualization supports a more inclusive and impactful approach to population health.

However, the Task Force currently lacks the capacity to routinely produce contextualized summaries or implementation supports. Embedding role clarity at the outset — whether the Task Force is producing new guidance or adapting existing sources — will make contextualization efforts more focused and efficient. In the short term, the most effective step may be to engage provinces and territories directly in the guideline development process, ensuring that their system-level realities and delivery models inform upstream decisions. This could take the form of structured collaboration with provincial screening programs, professional networks, and implementation bodies.

Looking ahead, the development of a national coordination hub — as proposed in Chapter 3 — offers an opportunity to build the infrastructure needed to support contextualization at scale. Such a hub could also support a recurring prioritization process, helping to define when the Task Force should develop guidance, versus when it should adopt or adapt existing materials. A hub could also facilitate information sharing and leveraging findings from open-source living evidence syntheses, as well as practical tools that provinces and territories can use to adapt guidelines efficiently. This approach would allow the Task Force to focus on scientific integrity while enabling local partners to translate recommendations into meaningful action and engagement with global partners to share work.

Ultimately, embedding contextualization within the Task Force's mandate will improve the clarity, usability, and reach of its guidance — ensuring that preventive health services are not only evidence-based, but also aligned with local delivery realities and equitably implemented across regions.

Recommendation 1: Modernize the mandate and rename the Task Force

PHAC should establish a clear and updated mandate for the Task Force that reflects its evolving role in supporting the delivery of preventive health services. This mandate should focus on the development of guidance that is inclusive, up-to-date, equity-centred and contextualizable for frontline health professionals. As part of this realignment, PHAC should consider renaming the group as the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Services to better reflect its focus on the full spectrum of preventive interventions delivered in primary care settings.

To support a modernized and future-ready Task Force, PHAC should revise its mandate to clearly define its role in addressing gaps in preventive health services through up-to-date, inclusive, and equity-centred guidance. This renewed mandate should go beyond consultation with key interest holders to include formalized alignments with provincial and territorial advisory and decision-making processes — including screening programs — and out to learning and improvement platforms (e.g., quality councils).

As part of the renewal, PHAC should consider renaming the Task Force to the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Services to reflect its full scope.

These updates should be formalized through revised terms of reference, a new mandate letter, and corresponding updates to governance, performance expectations, and funding agreements.

PHAC should also coordinate the development of an annual workplan, in which the Task Force outlines its upcoming priorities within a standard three-year planning horizon, adjusted yearly. This workplan should be shared with relevant provincial and territorial committees as well as other key interest holders to support priority setting, ranking, and the coordinated organization of work.

Recommendation 2: Clarify the Task Force's role in a crowded landscape

PHAC should establish a recurring, structured process to determine when the Task Force should lead the development of new preventive health guidelines, and when it would be more efficient to adopt or adapt existing high-quality recommendations from other sources. This process should be guided by a transparent prioritization framework and inform an annual workplan that sets the Task Force's strategic direction over a three-year horizon. By clarifying the Task Force's role within Canada's broader guideline ecosystem, this approach will reduce duplication, improve coordination, and address fragmentation across the system.

To ensure coordination and reduce duplication, PHAC should implement a structured recurring process to clarify the most appropriate role for the Task Force — whether to lead on emerging guideline topics, or to adopt or adapt existing high-quality recommendations. This process should be supported by a transparent methodological framework for topic prioritization that is co-developed with key interest holders (including provinces and territories) and which takes into account population needs, existing guidance from other national or provincial developers, and resource considerations. Once established, it should be applied consistently at the beginning of each planning cycle and integrated into the Task Force's reporting and accountability structures to support alignment, efficiency, and systemwide value.

Summary: Modernizing the Task Force mandate

Modernizing the Task Force's mandate is essential to ensuring its continued relevance and effectiveness in a rapidly evolving health system. Recommendations 1 and 2 call for a refocused mandate that clearly defines the Task Force's role in providing inclusive, evidence-based, and equity-centred and contextualizable guidance on preventive health services for all primary care health professionals. This includes renaming the Task Force to better reflect its expanded focus and responsibilities. To promote alignment and reduce duplication across Canada's guideline ecosystem, PHAC should also implement a structured recurring process to determine when the Task Force should develop new guidance, adopt existing high-quality guidance from other sources, or adapt existing recommendations. This process should be supported by a transparent methodological framework for activity prioritization, grounded in evidence gaps, population needs, and resource considerations. Embedding contextual adaptability as a design principle will also help ensure that recommendations can be meaningfully adapted across jurisdictions — supporting implementation and improving equity. Together, these actions will clarify the Task Force's strategic focus, reinforce its value across jurisdictions, and support a more coordinated, applicable and efficient approach to preventive care guidance.

2.2 Advancing evidence, methods, and guideline relevance

In today's rapidly evolving health systems, modernizing the Task Force's methodological approach is essential. Expectations for preventive health guidelines have increased: they must not only be based on the best available evidence, but also be relevant to diverse clinical settings, contextualizable within (and ideally supported by appropriate) health system arrangements, sensitive to health inequities, and reflective of diverse forms of lived experience. Improving the inclusiveness, applicability, and impact of recommendations requires updating how evidence is defined, appraised, and applied.

Streamlining and expanding methodological approaches

Developing high-quality preventive health services guidelines requires a methodological approach and an evidence review and recommendation development process that is not only scientifically rigorous but also structured to support contextualizable applications across the diversity of real-world health care.

The GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) methodology has long served as the cornerstone of the Task Force's approach. Its transparent and structured process has contributed significantly to the scientific credibility of its recommendations. However, in a context where preventive interventions are increasingly interdisciplinary, community-based, and equity-centred, over-reliance on GRADE can become limiting.

To address such challenges, the Task Force should streamline its methodological framework by building on the evolving GRADE approach — in particular, the development of core GRADE, which seeks to reconcile disparate guidance and provide a more coherent foundation (Iorio, 2024). Core GRADE offers a more flexible and current foundation for weighting diverse forms of evidence across various types of interventions. This should be supplemented with additional evidence-to-decision frameworks to support the development of guidelines in areas where evidence is limited or emerging — particularly for equity-denied populations.

While "Evidence to Decision" (EtD) tables are typically published, interest holders have raised concerns about the subjectivity in interpreting criteria, especially in the absence of a full evidence review. Ongoing concerns persist about how working groups weigh different criteria to determine thresholds for recommendations (e.g., in cancer screening).

To address these limitations, the Task Force should consider incorporating complementary frameworks that allow for the structured and transparent mapping of the rationale behind recommendations. These tools would not replace GRADE, but rather strengthen its application — particularly in cases where value judgments must be made explicit, where complexity and contextual factors influence implementation across jurisdictions, or where evidence is limited and equity considerations have historically been overlooked.

In parallel, methods and communications should be refined to clearly distinguish between primary care interventions targeting individuals and population-based interventions (like screening) that are clinically applied. This distinction is essential to ensure that recommendations are interpreted and applied appropriately across clinical communities and system-level settings.

A more inclusive and pluralistic approach — informed by transparent, equity-centred appraisal criteria and enhanced methodological clarity — would strengthen the scientific foundations of recommendations and help foster more equitable health outcomes nationwide.

Recommendation 3: Evolve the Task Force methodological framework

PHAC should enable and support the Task Force to streamline its methodological framework, building on the evolving GRADE approach — particularly Core GRADE — to ensure rigorous and inclusive guideline development. This should be supplemented with additional evidence-to-decision frameworks suited to supporting recommendations for equity-denied populations and in areas where evidence is limited or emerging.

PHAC should also support the refinement of methods and communication strategies for population-based interventions that are clinically applied in primary care (e.g., screening), ensuring clarity and relevance for diverse audiences.

We do note that GRADE is regularly updated and has evolved to allow for a broad range of methodological approaches to be integrated into guideline development. For example, core GRADE is the latest evolution, which takes disparate, sometimes contradictory guidance in GRADE papers and helps to create a coherent whole.

Preventive services involve offering interventions to individuals who are generally healthy. As a result, assessing the balance of potential benefits and harms is significantly more complex than in clinical contexts involving diagnosis and treatment. This complexity often requires consideration of a broader range of evidence such as observational studies, economic modelling, and qualitative research.

Transitioning to a living guidelines model

To keep pace with emerging evidence and evolving practice, the Task Force should gradually transition to a living guidelines model — one that responds to new research findings on a continuous basis.

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the importance of timely, evidence-based updates and highlighted the value of real-time synthesis and international collaboration in adapting to rapidly changing conditions and evidence.

Given the complexity of this transition, the Panel recommends a phased and flexible approach. This should begin with a limited number of high-priority topics and use a hybrid approach — adapting trusted international guidelines where appropriate, while developing Canadian-specific recommendations in areas requiring local context, enabling the Task Force to build capacity incrementally and gradually expand toward the full spectrum of preventive health services, while ensuring contextual relevance and operational efficiency.

International collaboration will be essential to this strategy. Emerging initiatives — such as the Evidence Synthesis Infrastructure Collaborative (working across health and many other sectors) and the Alliance for Living Evidence on Anxiety, Depression, and Psychosis (working in a specific part of the health sector) — demonstrate the potential of shared platforms to enable real-time synthesis, reduce costs, and expand access to high-quality evidence. By engaging with global efforts, the Task Force can contribute to and benefit from innovative efforts to improve the efficiency of preventive health guideline development.

PHAC should explore opportunities to scale up the application of promising digital tools (for example, Artificial Intelligence (AI) assisted evidence synthesis, or automated literature surveillance), which are currently in pilot stages within the Agency. These technologies can help streamline the process of updating guidelines, reduce workload, and improve timeliness. Pilot projects focused on select guidelines can serve as test cases to assess operational feasibility, user experience, and equity.

To ensure success, this transition must be supported by sustained investment, dedicated staffing, and robust infrastructure. It will also require attention to equity — ensuring that living updates remain inclusive, accessible, and adaptable across diverse health care settings and populations in Canada.

Recommendation 4: Implement a phased living guidelines model

PHAC should enable and support the Task Force to implement a phased approach to maintaining and updating high priority guidelines using living methods. This includes continuous evidence monitoring, the use of emerging technologies, and collaboration with international partners. PHAC should seize opportunities to share in evidence infrastructure to enable greater efficiency and lower redundancy. This approach will also allow provinces and territories to rely on shared evidence and focus their efforts on contextualizing guidance for their own service delivery models.

PHAC should support the Task Force in phasing in a living guideline model and continuous evidence monitoring — beginning with a gradual approach focused on high-priority topics — to ensure that guidelines remain current, relevant and responsive to changing context and emerging evidence. This should include identifying suitable guideline areas, establishing continuous evidence surveillance mechanisms, and applying continuous reassessment protocols. PHAC should also scale up established and emerging digital tools currently in pilot stages within the Agency and provide the operational infrastructure and staff required for sustainable implementation. Partnerships with international organizations and methodologists experienced in living guideline models can accelerate capacity building and ensure alignment with global best practices. This phased transition should ultimately enable the expansion of living guidelines across the full spectrum of preventive services, ensuring recommendations are up-to-date, as well as applicable to Canada's diverse health care systems.

Supporting the equitable uptake of preventive health guidelines

To ensure that preventive health services guidelines are not only evidence-based but also effectively implemented across Canada's diverse health care settings, the Task Force should strengthen its capacity to assess feasibility, uptake, and equity impacts. Currently, limited capacity exists within the Task Force to evaluate how its recommendations are applied in practice or to support adaptive implementation. Without such mechanisms, valuable insights are missed, and gaps in equitable service delivery may persist.

To address this, the Task Force should establish an implementation and impact support framework as part of its guideline development process. This framework should include structured engagement with relevant provincial and territorial bodies — such as screening programs and quality councils, where these exist, and preventive service delivery organizations — to identify practical enablers and barriers, align with local resources and support a system-wide implementation planning.

This shift does not require creating new structures but rather is based on strengthening alignment and partnership with existing implementation actors that are already well positioned to support implementation — such as screening programs and quality councils, and electronic health records initiatives. Each guideline cycle should include co-developed knowledge translation tools — such as provider decision aids, user-specific summaries, and implementation toolkits — tailored to primary care professionals and public health programs. As part of this effort, particular attention should be given to improving the clarity and accessibility of communications about risks and benefits associated with Task Force recommendations, ensuring that both providers and the public are equipped to make informed decisions.

PHAC should support this work by providing the necessary resources and technical expertise to co-develop these tools and ensure their broad dissemination. By embedding implementation planning and real world monitoring and light-touch evaluation into its core functions, the Task Force will improve the reach, relevance, and population-level impact of its preventive service guidance — particularly for underserved populations and in under-resourced settings.

Recommendation 5: Strengthen practice adoption through partnership and adaptation

PHAC should enable and support the Task Force in collaborating with provincial and territorial partners to support the system-level conditions necessary for the effective implementation of preventive health service guidelines. This includes structured engagement with prevention intervention delivery programs, quality councils, and other implementation and evaluation partners to co-develop practical tools and identify barriers and enablers across diverse care settings. Each guideline cycle should integrate knowledge translation resources — such as provider decision aids, implementation toolkits, and user-specific summaries — tailored to the needs of primary care teams and the systems that support them. PHAC should also support the development of mechanisms to assess feasibility, uptake, and impacts in coordination with jurisdictions.

Rather than focusing solely on individual clinician behaviour, this approach emphasizes working alongside health system actors to adapt and strengthen programs, policies, and operational infrastructure — ensuring that Task Force recommendations are not only evidence-based, but also deliverable in practice. By fostering ongoing collaboration with provincial and territorial implementation partners, the Task Force can narrow the gap between evidence and action to support a more consistent adoption of preventive health recommendations.

Summary: Modernizing evidence synthesis and review

To maintain the relevance, equity, and impact of its recommendations, the Task Force must modernize its methodological approach. This involves thoughtfully broadening the types of evidence considered, integrating complementary frameworks alongside GRADE, and enhancing transparency in decision-making processes. Embracing a living guidelines model will facilitate continuous updates based on emerging evidence, increasing responsiveness and relevance. PHAC can support this evolution through strategic investments in digital tools, international collaboration, and a phased implementation strategy. Strengthening engagement with provincial and territorial implementation partners will help ensure that Task Force recommendations are not only evidence-based but also deliverable in practice, fostering consistent adoption and narrowing the gap between evidence and action.

2.3 Embedding equity: Towards inclusive guideline development

Embedding equity at every stage of the guideline development process is critical to ensuring that preventive health recommendations are relevant, actionable, and inclusive for all people in Canada. While the Task Force has established a strong foundation in evidence-based guidance, equity considerations are not yet systematically embedded across all stages — from topic framing and evidence review to interest holder engagement and implementation planning. Without a deliberate and structured approach, guidelines risk unintentionally reinforcing existing disparities by overlooking the unique needs and lived experience of Indigenous, Black, rural, and other equity-denied communities.

Moreover, without clear equity-centred criteria to guide prioritization, health conditions that disproportionately affect equity-denied populations may continue to receive insufficient attention. Strengthening the integration of equity considerations stands to enhance the real-world relevance, credibility, and impact of Task Force recommendations, ultimately supporting more equitable health outcomes nationwide.

Enhancing transparency in topic selection

A transparent and equity-driven approach to topic selection is a key first step. To ensure that preventive service guidelines address the most pressing health needs — particularly those affecting populations facing systemic barriers to care — the Task Force must improve the clarity and consistency of its topic selection process.

Interest holders expressed concerns about the lack of transparency in how topics are prioritized and on the absence of clear, equity-sensitive criteria. Some expressed that it is not clear how or why specific topics are chosen, or how population needs, health equity, or system impacts are factored into these decisions.

Conditions such as chronic disease prevention or mental health screenings — both of which disproportionately impact marginalized groups — have not always received sufficient focus under the current approach (Georgiades, 2021; Price et al., 2013). This risks perpetuating the very disparities that preventive guidance is meant to address.

To build trust, ensure responsiveness, and promote accountability, the Task Force should implement a structured and transparent topic selection framework that explicitly incorporates equity considerations. The framework should explicitly include clear, public-facing criteria such as potential equity impact, disease burden, relevance to primary care practice, and the extent of current guidelines gaps. It should also be developed in collaboration with provincial and territorial partners and informed by the lived experience of diverse interest holders.

Embedding equity in topic selection is not only a matter of fairness — it is essential to ensuring that future guidelines are targeted, aligned with population needs, and capable of driving meaningful improvements in health equity and system performance.

Recommendation 6: Prioritize equity in topic selection

PHAC should support the Task Force in applying transparent, equity-focused criteria to topic selection, with a focus on equity-denied populations — including Black and Indigenous communities — and the priorities of provinces and territories. A topic sequencing approach should guide progress toward full preventive service coverage, while also addressing current uneven coverage of guideline topics — such as duplication in some areas (e.g., cancer) and lack of guidance in others (e.g., mental health). Topic framing should emphasize opportunities to improve outcomes across the health system, especially in areas that support health equity and align with the quadruple aim.Footnote 1

To strengthen equity in guideline development, PHAC should enable and support the Task Force to adopt a transparent and equity-centred approach to topic selection — one that explicitly prioritizes equity-denied populations and aligns with provincial and territorial program priorities. This framework should include published criteria for prioritization, including measures of health disparities — such as differences in the burden of disease, access to services, and in health outcomes resulting from those services.

PHAC should support the establishment of regular engagement mechanisms — such as advisory input from equity-denied communities, Indigenous partners, frontline primary care providers, as well as equity offices in provincial programs and quality councils — to identify emerging issues and validate topic relevance. In addition, PHAC should enable and support routine review cycles to reassess priorities in light of evolving population health trends and system feedback. These expectations should be formalized in the Task Force's mandate letter and supported by dedicated resources for coordination, engagement, and transparent reporting of selection decisions.

Integrating patient and public perspectives for more inclusive guidelines

Preventive service guidelines must reflect the lived experiences, patient preferences, community, and cultural contexts of the people they are intended to serve. At present, patient and public involvement in the Task Force guideline development process is limited. This gap represents missed opportunities to identify access barriers, feasibility in real-world settings, and incorporate diverse perspectives on risk, benefits, as well as acceptability and feasibility of care.

Systematic and equity-centred engagement with patients and communities — particularly those historically underrepresented in health policy and clinical decision-making — would strengthen the legitimacy, fairness, and uptake of recommendations. It would also improve the relevance of guidelines across diverse social, cultural, and geographic contexts.

International examples, such as the UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), demonstrate the value of meaningful engagement through mechanisms such as public advisory panels, targeted consultations including surveys, focus groups, and citizen juries. These approaches not only enhance transparency and trust, but also improve the practical applicability of recommendations.

The Task Force should adopt a similar model, embedding patient and public perspectives at all stages of its work — from topic selection and evidence interpretation to guideline formulation and implementation planning. In support of this goal, PHAC could also explore the development of a cross-guideline development body engagement infrastructure (e.g., a shared network of public and patient advisory panels) to support consistency, efficiency, and inclusivity across Canadian guidance bodies.

Recommendation 7: Establish a model for equity-centred patient and public engagement

PHAC should enable and support the Task Force to adopt structured, consistent mechanisms for engaging patients, community groups — including Black, Indigenous and other communities historically underrepresented in health policy and clinical decision-making — and the public throughout guideline development, ensuring that lived experience, patient preferences and community values are meaningfully reflected in final recommendations.

To embed lived experience and community perspectives into preventive guidance, PHAC should enable and support the Task Force to implement a formal, equity-centred patient and public engagement strategy. This should include the creation of standing advisory panels, structured opportunities for input at each stage of guideline development, and transparent reporting on how feedback was considered. Engagement processes should prioritize the inclusion of individuals from underserved and equity-denied communities. PHAC should also explore the development of shared infrastructure — such as a national roster or engagement support services — to improve consistency and efficiency across Canadian health guidance bodies. Dedicated resources should be allocated to capacity building to support meaningful, accessible, and sustained engagement.

In conclusion, embedding equity into the preventive service guideline development process is not a separate initiative — it must be a foundational principle that shapes how topics are selected and framed, evidence is assessed, communities are engaged, and recommendations are articulated. A more inclusive, transparent, up-to-date, and responsive approach will ensure that preventive service guidelines serve all Canadians fairly and effectively. With sustained policy support, investment in capacity, and commitment to innovation and collaboration, the Task Force can lead the way in setting a new standard for equity-centred guideline development in Canada.

Summary: Embedding equity: Towards inclusive guidelines

To ensure preventive guidelines are relevant, inclusive, and actionable for all people in Canada, equity must be embedded across every stage of the Task Force's work. Recommendations 6 and 7 provide a roadmap for operationalizing this commitment — from topic selection to equity-centred patient and public engagement. These reforms will strengthen the Task Force's ability to address health disparities and ensure that guidance reflects the lived experiences and priorities of equity-denied populations. Together, they reinforce the importance of developing preventive health service recommendations that are not only scientifically rigorous, but also equitable, practical, and aligned with the needs of those most often left behind.

2.4 Strengthening governance for inclusive and contextualizable guidance

A strong and transparent governance framework is essential to ensuring the long-term sustainability, credibility, and operational efficiency of the Task Force. It is also necessary to support the development of guidance that is both methodologically sound and adaptable to the diverse operational contexts across Canada. Targeted reforms can enhance its capacity to respond to evolving health care challenges while preserving public trust. This section outlines key changes to strengthen the Task Force, starting with broadening its membership to incorporate diverse expertise, to enrich guideline development with a wider range of perspectives. It also explores the balance between rigorous conflict of interest management and inclusivity, ensuring that diverse perspectives can be integrated without compromising impartiality. Securing stable and sufficient funding is highlighted as essential to sustaining Task Force operations and supporting resource-intensive activities such as greater engagement and evidence synthesis.

Collectively, these proposed enhancements lay the groundwork for a core recommendation — namely, for PHAC to re-establish the Task Force as an external advisory body, with a reconceptualized organizational structure. Drawing on the established framework of other external advisory bodies, such as the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI), these reforms aim to strengthen decision-making, improve transparency, and ensure that guideline development reflects both cutting-edge expertise and the lived experience of diverse populations across Canada.

Strengthening membership diversity through inclusive selection and transparent nomination

To ensure that preventive health service guidelines are relevant, trusted, and applicable across diverse Canadian contexts, The Task Force's membership must reflect a balance of expertise, lived experience, and system perspectives. This includes representation from different professions, jurisdictions, and communities — particularly those facing systemic barriers to equitable care.

Ensuring that Task Force members reflect a wide range of care delivery settings — including those from jurisdictions with unique program structures or access challenges — will also strengthen the Task Force's ability to develop contextualizable recommendations that can be meaningfully adapted by provinces, territories, and diverse provider groups.